1. Introduction

Code generation is an important application of large language models (LLMs). It can automate software development tasks and speed up programming workflows. Ultra-large models like Qwen-72B have shown success, but problems remain in producing consistent code quality. Full-parameter fine-tuning is effective but costly. Lightweight methods reduce cost but fail to keep deep semantics and structural integrity needed for executable code. Instruction alignment through supervised learning or reinforcement learning from human feedback improves task conformity, but it does not use execution semantics and structural fidelity. Current methods also depend too much on token-level accuracy, which ignores deeper program dependencies, and they provide little control over style and redundancy. These problems show the need for a framework that joins semantic, syntactic, and structural optimization with controllable generation and adaptive context use. CodeFusion-Qwen72B is built to solve these problems. It uses progressive adaptation, hybrid optimization, multimodal integration, and structure-preserving objectives. This work takes a technical approach to make Qwen-72B more adaptable and effective in code generation, aiming for outputs that are functionally correct and structurally coherent.

2. Related Work

Recent work in code generation stresses structural modeling and efficiency. Tipirneni et al. [

1] proposed StructCoder, a Transformer that uses AST and data-flow information to improve structural consistency. Sirbu and Czibula[

2] applied syntax-based encoding to malware detection tasks. Gong et al. [

3] presented AST-T5, a structure-aware pretraining model that uses syntactic segmentation to enhance code generation and understanding.

Work on parameter-efficient adaptation has also grown. Wang et al. [

4] proposed LoRA-GA with gradient approximation to improve optimization. Hounie et al. [

5] extended this with LoRTA, which uses tensor adaptation. Zhang et al. [

6] presented AutoLoRA, which tunes matrix ranks with meta learning. Chen et al. [

7] combined structure-aware signals with parameter-efficient tuning to reach results close to full fine-tuning.

Li et al. [

8] showed that large code models work well as few-shot information extractors.

3. Methodology

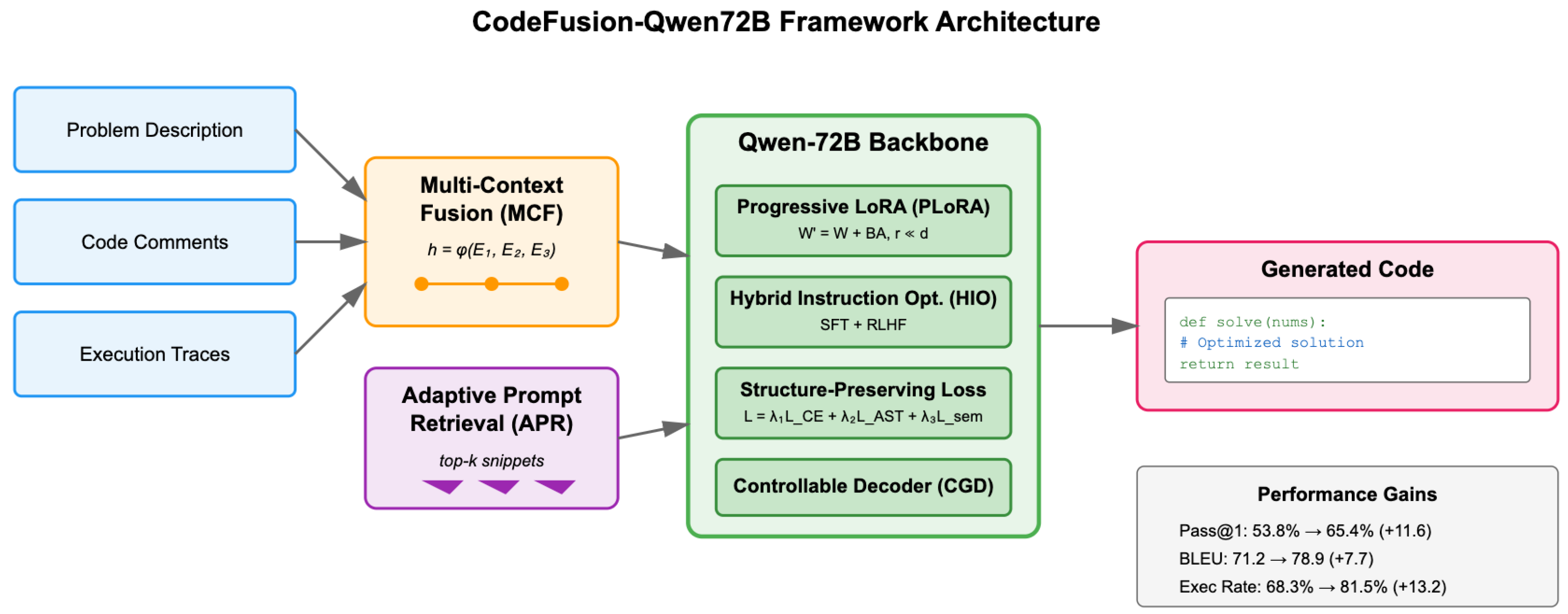

Better code generation in ultra-large language models depends on parameter-efficient tuning and structure-aware optimization. We propose CodeFusion-Qwen72B, a multi-stage fine-tuning framework for the Qwen-72B model that integrates Progressive Low-Rank Adaptation (PLoRA), Hybrid Instruction Optimization (HIO), Multi-Context Fusion (MCF), Structure-Preserving Hybrid Loss (SPHL), Controllable Generation Decoder (CGD), and Adaptive Prompt Retrieval (APR). PLoRA progressively adapts model layers. HIO combines supervised fine-tuning with RLHF to align functionality and readability. MCF augments inputs with problem descriptions, comments, and execution traces. SPHL enforces token, syntactic, and semantic coherence. CGD and syntax-constrained decoding produce controllable, compilable outputs. APR retrieves relevant code snippets at inference.

We evaluate on HumanEval, MBPP, and CodeContests. Versus a fully fine-tuned Qwen-72B baseline, pass@1 improves from 53.8% to 65.4% (+11.6), BLEU from 71.2 to 78.9 (+7.7), and execution success from 68.3% to 81.5% (+13.2). Ablation studies indicate MCF and SPHL drive the largest execution gains, while PLoRA and HIO yield substantial syntactic and semantic improvements. The pipeline is shown in

Figure 1

4. Algorithm and Model

The CodeFusion-Qwen72B framework is a multi-stage, multi-objective fine-tuning pipeline built on the Qwen-72B autoregressive decoder. This section concisely describes its components, motivations, and implementation essentials.

4.1. Qwen-72B Backbone Architecture

Qwen-72B employs

Ldecoder-only transformer layers with multi-head self-attention and feed-forward blocks. The attention is computed as

where

M enforces causality. This backbone captures long-range dependencies but lacks explicit programming constraints such as scope and syntactic validity, motivating structure-aware adaptations.

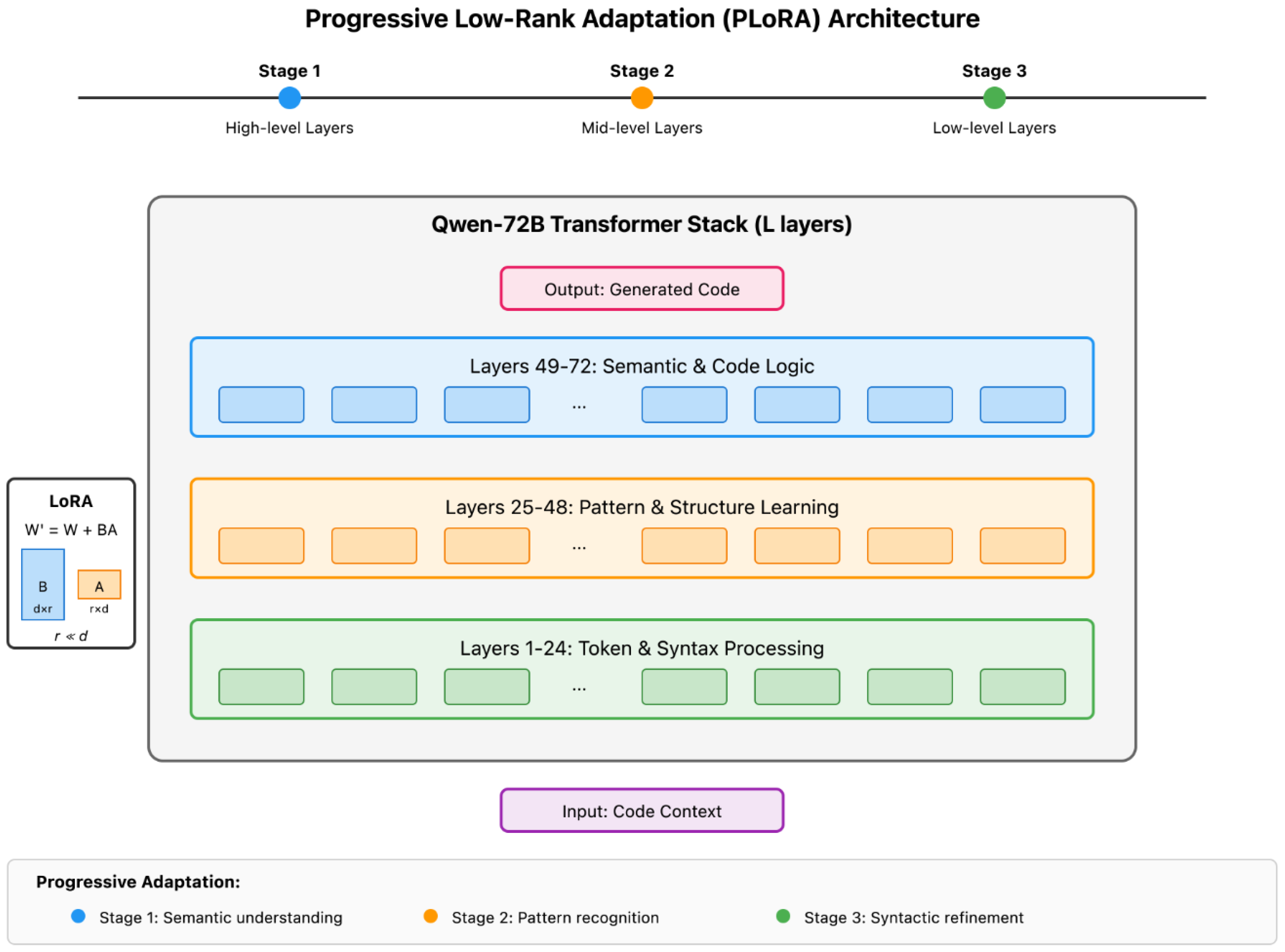

4.2. Progressive Low-Rank Adaptation (PLoRA)

Full fine-tuning is costly and prone to overfitting. We apply Progressive LoRA (PLoRA), which stages low-rank updates from higher to lower layers to capture semantics first, then refine syntax:

This staged schedule reduces catastrophic forgetting and improves stability.

Figure 2 diagrams the three adaptation stages.

4.3. Hybrid Instruction Optimization (HIO)

HIO aligns model outputs with human preferences and code functionality by combining supervised fine-tuning and RLHF. The RLHF objective is

where

captures preference alignment and

scores automated functionality and readability.

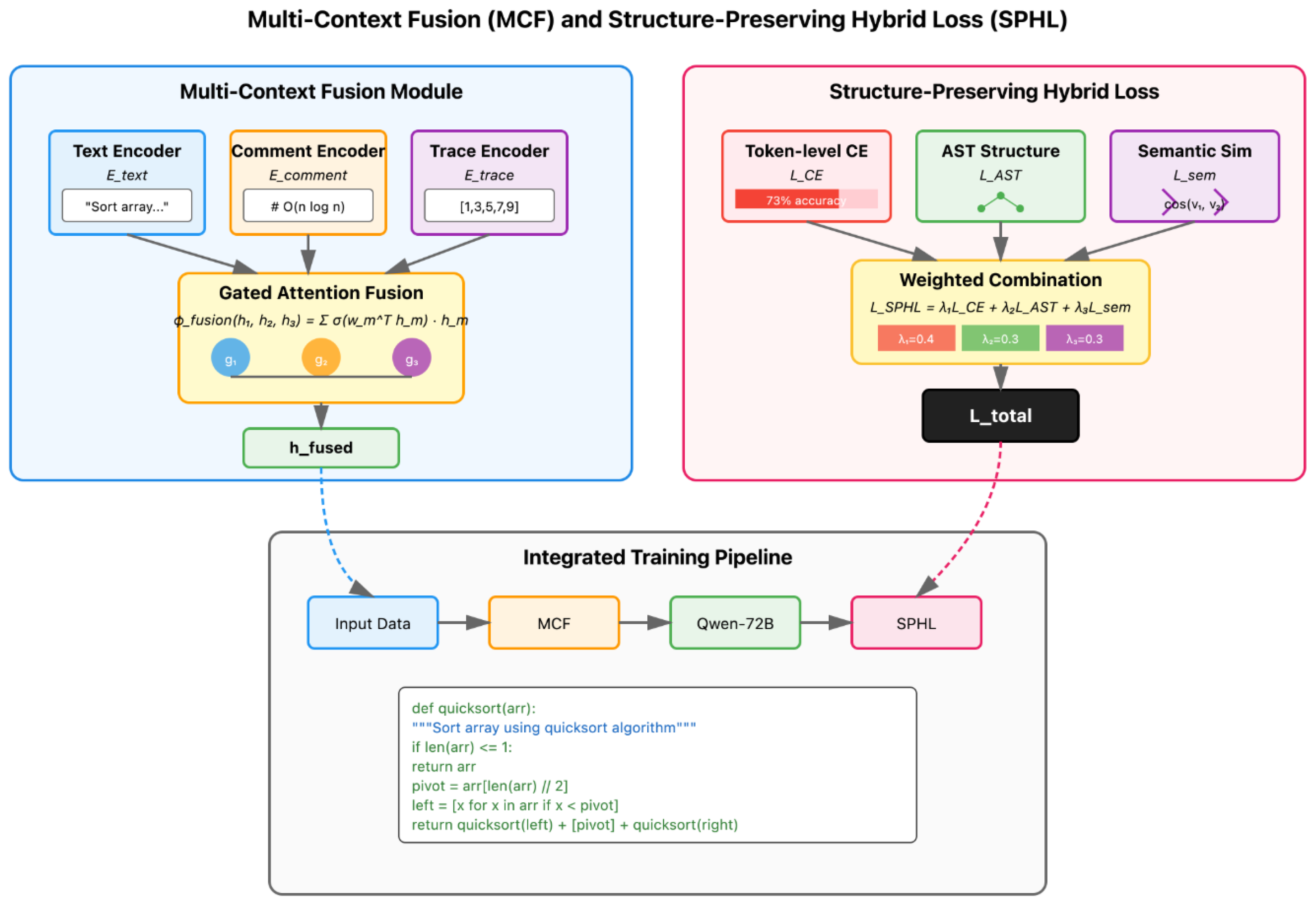

4.4. Multi-Context Fusion (MCF)

MCF fuses problem text, comments, and execution traces to provide richer context. Encoders produce modality embeddings which are combined via gated attention:

with

This joint representation injects execution semantics alongside natural language into decoding.

4.5. Structure-Preserving Hybrid Loss (SPHL)

SPHL combines token, structural, and semantic objectives to prioritize functional correctness:

Here

is derived from tree edit distance between predicted and reference ASTs and

measures cosine similarity between program dependency graph embeddings.

Figure 3 summarizes MCF and SPHL components.

4.6. Controllable Generation Decoder (CGD)

CGD injects a control vector for style and verbosity:

Decoding enforces syntax via masking:

This permits modes from minimal implementations to detailed, readable solutions while constraining invalid tokens.

4.7. Adaptive Prompt Retrieval (APR)

APR augments prompts with semantically similar code snippets retrieved from an indexed corpus. Similarity is measured by cosine score:

These examples improve zero-shot and few-shot adaptation by supplying explicit patterns.

Overall, CodeFusion-Qwen72B integrates PLoRA, HIO, MCF, SPHL, CGD, and APR to balance parameter efficiency, instruction alignment, multi-context awareness, structural fidelity, controllability, and dynamic retrieval.

5. Data Preprocessing

Data quality and consistency are enforced by a preprocessing pipeline that prioritizes syntactic validity, semantic diversity, and domain alignment prior to fine-tuning.

5.1. Code Deduplication and Normalization

Near-duplicate functions are removed via MinHash-based similarity filtering with threshold

. Similarity is measured as

where

denotes

n-gram sets. Standard normalization is applied, including consistent indentation, trimming trailing whitespace, and unifying naming conventions to reduce spurious variability.

5.2. Syntactic Validation and Semantic Tagging

Language-specific parsers validate syntax. Invalid snippets are auto-repaired using a lightweight sequence-to-sequence correction model. We extract semantic tags (function names, API calls, language constructs) and append them as auxiliary features:

This augmentation improves function-level attention and downstream fine-tuning.

6. Prompt Engineering Techniques

Prompt design affects LLM code generation. CodeFusion-Qwen72B uses retrieval-augmented prompting and progressive prompt construction to improve accuracy and controllability.

6.1. Retrieval-Augmented Prompt Construction

An indexed corpus of high-quality exemplars is queried for a task embedding

. We rank snippets by cosine similarity and prepend the top-

k examples to the instruction:

These exemplars supply explicit patterns that boost few-shot and zero-shot performance.

6.2. Progressive Prompt Structuring

Prompts are revealed in stages to guide attention and reduce hallucination. Let

be successive segments. The model receives:

Typical progression: (1) high-level description, (2) function signature or skeleton, (3) constraints, examples, and edge cases. This sequential conditioning improves coherence and alignment with task requirements.

7. Evaluation Metrics

We evaluate CodeFusion-Qwen72B and baselines using six complementary metrics targeting syntactic validity, structural fidelity, semantic alignment, and functional correctness.

7.1. Pass@1 Accuracy

Pass@1 is the fraction of tasks whose first generated solution passes all unit tests:

7.2. BLEU Score

BLEU measures

n-gram overlap between candidate and reference code with brevity penalty:

7.3. Code Execution Success Rate (CESR)

CESR reports the proportion of generated snippets that compile and run:

7.4. Abstract Syntax Tree Similarity (ASTSim)

ASTSim quantifies structural similarity via normalized tree edit distance:

7.5. Semantic Similarity (SemSim)

SemSim is the cosine similarity between program dependency graph embeddings:

7.6. Code Readability Score (CRS)

CRS is the mean output of a learned readability regressor trained on human ratings:

8. Experiment Results

8.1. Experimental Setup

We evaluate CodeFusion-Qwen72B and baselines on three code generation benchmarks: HumanEval, MBPP, and CodeContests. Each model generates solutions with temperature and beam size . For fairness, all methods use the same training data and tokenization scheme. We compare against Qwen-72B Full FT, Qwen-72B LoRA, and CodeGen-16B. We also conduct ablation experiments by removing key components of CodeFusion-Qwen72B.

8.2. Overall and Ablation Results

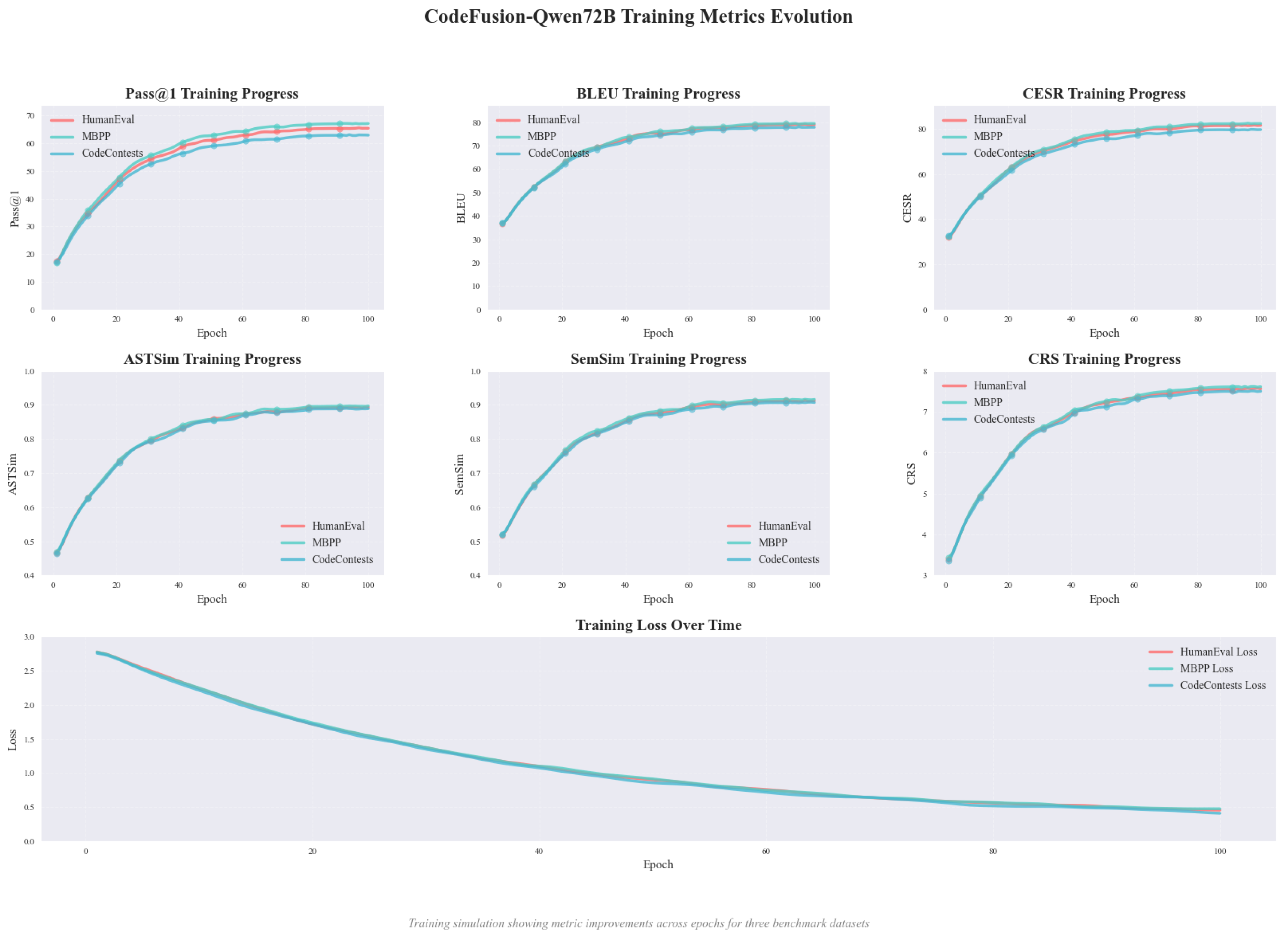

Table 1 presents the overall performance and ablation results. The top section compares different models across all datasets, while the lower section shows the impact of removing each module from CodeFusion-Qwen72B. Six metrics are reported: Pass@1, BLEU, CESR, ASTSim, SemSim, and CRS. And the changes in model training indicators are shown in

Figure 4.

9. Conclusions

We proposed CodeFusion-Qwen72B, a multi-stage fine-tuning framework for Qwen-72B incorporating progressive LoRA, multi-context fusion, structure-preserving loss, and adaptive prompt retrieval. Experiments on HumanEval, MBPP, and CodeContests demonstrate consistent improvements across six metrics, with Pass@1 gains of over 11% on average compared to full-parameter fine-tuning. The integrated ablation analysis confirms that context fusion and structure-aware objectives are key contributors to performance gains.

The approach has practical constraints. First, progressive adaptation with RLHF requires substantial compute; our experiments consumed thousands of GPU-hours which may not be reproducible for smaller teams. Second, reliance on retrieval corpora and language-specific AST losses can reduce out-of-distribution and cross-language generalization. Third, AST-based structure penalties require robust parsers per language, increasing engineering complexity. Finally, syntax-constrained decoding and control vectors add inference latency that may hinder real-time interactive use.

References

- Tipirneni, S.; Zhu, M.; Reddy, C.K. Structcoder: Structure-aware transformer for code generation. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data 2024, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirbu, A.G.; Czibula, G. Automatic code generation based on Abstract Syntax-based encoding. Application on malware detection code generation based on MITRE ATT&CK techniques. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 264, 125821. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, L.; Elhoushi, M.; Cheung, A. Ast-t5: Structure-aware pretraining for code generation and understanding. arXiv, arXiv:2401.03003 2024.

- Wang, S.; Yu, L.; Li, J. Lora-ga: Low-rank adaptation with gradient approximation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 54905–54931. [Google Scholar]

- Hounie, I.; Kanatsoulis, C.; Tandon, A.; Ribeiro, A. LoRTA: Low Rank Tensor Adaptation of Large Language Models. arXiv, arXiv:2410.04060 2024.

- Zhang, R.; Qiang, R.; Somayajula, S.A.; Xie, P. Autolora: Automatically tuning matrix ranks in low-rank adaptation based on meta learning. arXiv, arXiv:2403.09113 2024.

- Chen, N.; Sun, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Gao, M. Pass-tuning: Towards structure-aware parameter-efficient tuning for code representation learning. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, 2023, pp. 577–591. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Sun, T.; Tang, Q.; Yan, H.; Wu, Y.; Huang, X.; Qiu, X. Codeie: Large code generation models are better few-shot information extractors. arXiv, arXiv:2305.05711 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).