1. Introduction

The cholinergic signalling system, which relies on acetylcholine (ACh), is widespread throughout the body. Cholinergic cells express the enzyme choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), which synthesizes ACh by transferring the acetyl-moiety of an acetyl-coenzyme A molecule (A-CoA) to a choline molecule. The canonical view is that ChAT is a cytosolic enzyme and that ACh biosynthesis occurs in the cytosol. However, recent studies challenge this view, showing that ChAT is released by certain cells into the extracellular fluids, where it maintains an extracellular ACh equilibrium in the presence of fully active ACh-degrading enzymes [

1,

2].

In addition to ChAT, the cholinergic system includes two primary receptor subtypes: nicotinic receptors (nAChRs), which are ligand-gated ion channels, and muscarinic receptors (mAChRs), which are metabotropic receptors [

3]. Two key transporter proteins also contribute to cholinergic function: the vesicular ACh transporter (VAChT), responsible for packaging ACh into vesicles, and the high-affinity choline transporter (hChT), which enables choline reuptake after ACh release and hydrolysis at synapses. Furthermore, two enzymes break down ACh to terminate its action by hydrolyzing it into choline and acetate [

3]. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is the primary enzyme responsible for ACh degradation, while butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) might act as a decoy, safeguarding AChE’s essential function from inhibitors that may enter the system through dietary sources [

4]. While expression of ChAT and synthesis of ACh as a signaling molecule defines the cells as cholinergic, the downstream postsynaptic neurons and glial cells that express one or more subtypes of AChRs are denoted as cholinoceptive cells. Notably, all cholinergic cells can also be considered cholinoceptive given that ACh has autocrine activity, for instance through autoreceptor types of AchRs [

3].

There are two main types of cholinergic cells: neuronal and non-neuronal subtypes. Several cholinergic neuronal systems exist. One is the central cholinergic system, originating from the basal forebrain [

5]. This system has four main nuclei (Ch1-Ch4) that project across the brain [

3]. This network plays an essential role in cognitive function, attention, and memory, and becomes affected in dementia disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), dementia with Lewy bodies, and Parkinson’s dementia [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. There are also cholinergic interneurons, as part of the nigrostriatal system, especially in regions like the putamen, that are compromised in Parkinson's disease and disorders like corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Another neuronal cholinergic system comprises the parasympathetic system, consisting of the 12 cranial nerves which connect directly to organs, muscles, and glands, controlling various bodily functions. These together with cholinergic neuromotor neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord are progressively lost in neuromotor disorders like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [

15,

16]. Another neuronal cholinergic system consists of the enteric cholinergic circuitries in the enteric nervous system (ENS), controlling motility (muscular) and secretory reflexes within the gastrointestinal tracts [

17]. It is suggested that ~64% of neurons in ENS are cholinergic. There is also evidence that cholinergic circuitries in ENS are affected in many neurodegenerative diseases [

18].

Non-neuronal cholinergic cells are a variety of ChAT-expressing cell types, including epithelial, mesothelial, endothelial, immune cells [

19]. Surprisingly, ChAT expression increases in lymphocytes and macrophages, especially under inflammatory conditions [

1]. This expression is thought to be part of a "cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway," where ACh acts as an immune-regulatory agent, modulating cytokine release and inflammation [

19]. In aging and some other diseases, a reduction in this pathway may contribute to excessive inflammatory responses. Accumulating reports also strongly point toward an upregulation of cholinergic machinery in various cancer forms, in particular small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and colon cancer [

20,

21,

22,

23]. In this context, ACh may act as an autocrine growth factor [

23,

24], and use of nicotinic ACh receptor antagonists as anticancer drugs has been proposed [

20,

25].

While the current view is that ChAT exists mainly as a soluble cytosolic enzyme, there are reports of intracellular membrane-bound forms of ChAT in synaptosomes and cholinergic nerve terminals across several animal species [

26,

27,

28]. As an integral membrane protein, ChAT may behave differently compared to when it is localized in the cytosol [

28]. A recent in vitro study indicates that human ChAT protein readily becomes embedded in micellar nanoparticles with a dramatic 10-fold increase in its catalytic rate [

29]. ChAT may also retain a nuclear localization signal, allowing its translocation to the nucleus, although the function of ChAT in the nucleus remains elusive [

30,

31].

In this study, we aimed to investigate the expression of ChAT and related cholinergic markers in four different tumor cell lines to characterize and establish a robust cholinergic model for screening and in vitro characterization of various types of ChAT ligands, such as its inhibitors and/or activators [

29,

32,

33]. In addition, we sought to determine whether ChAT is localized extracellularly as a membrane-bound enzyme, as reported in human spermatozoa [

2]. Furthermore, we examined the presence of both cellular cholinergic machinery and compared the surface versus intracellular localization of key components of the cholinergic system across the four different cell lines (a human neuroblastoma cell line, a human adenocarcinoma cell line and two human small cell lung carcinoma cell lines [

34]). The results provide novel insights into cholinergic signaling mechanisms involved in neurodegeneration and carcinoma pathology.

3. Discussion

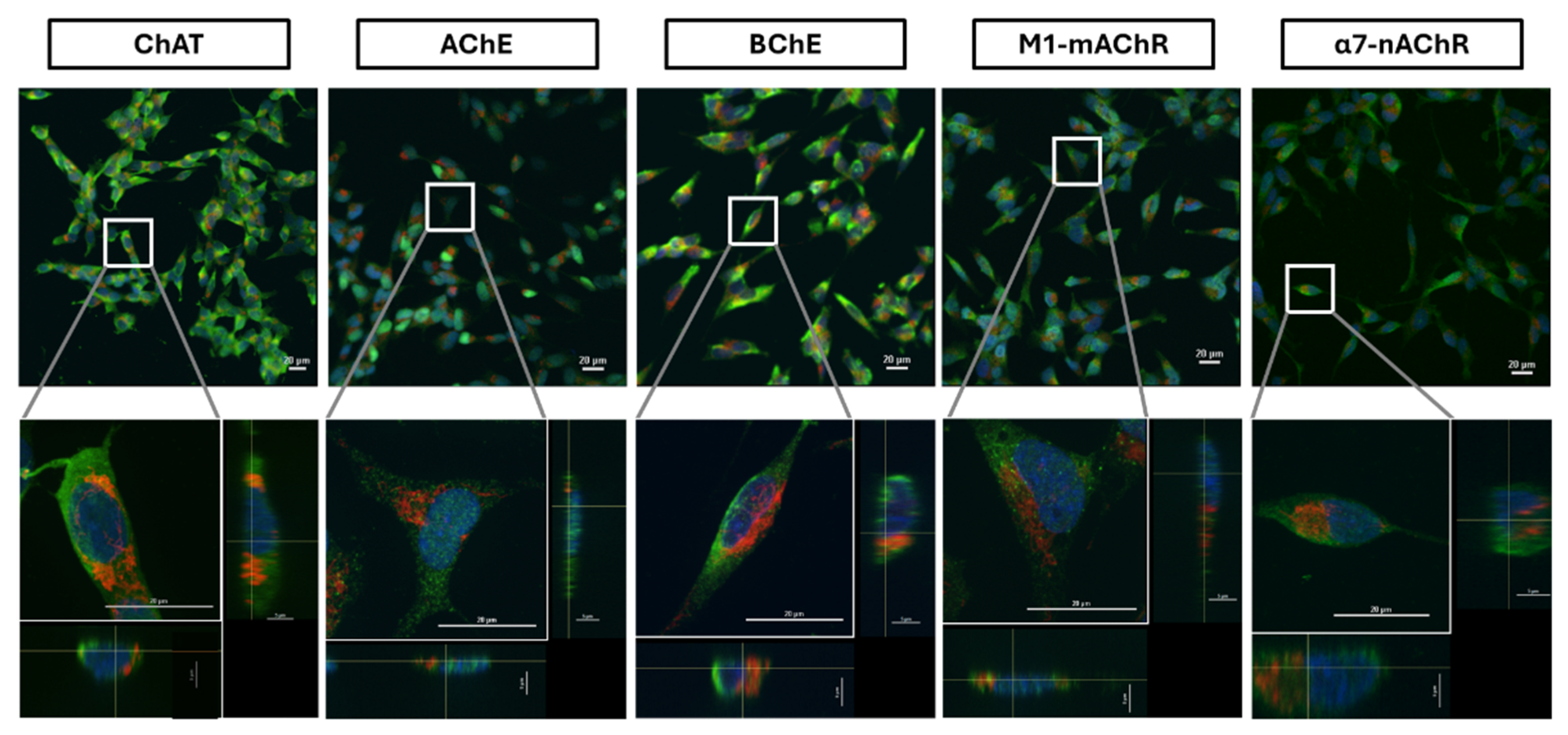

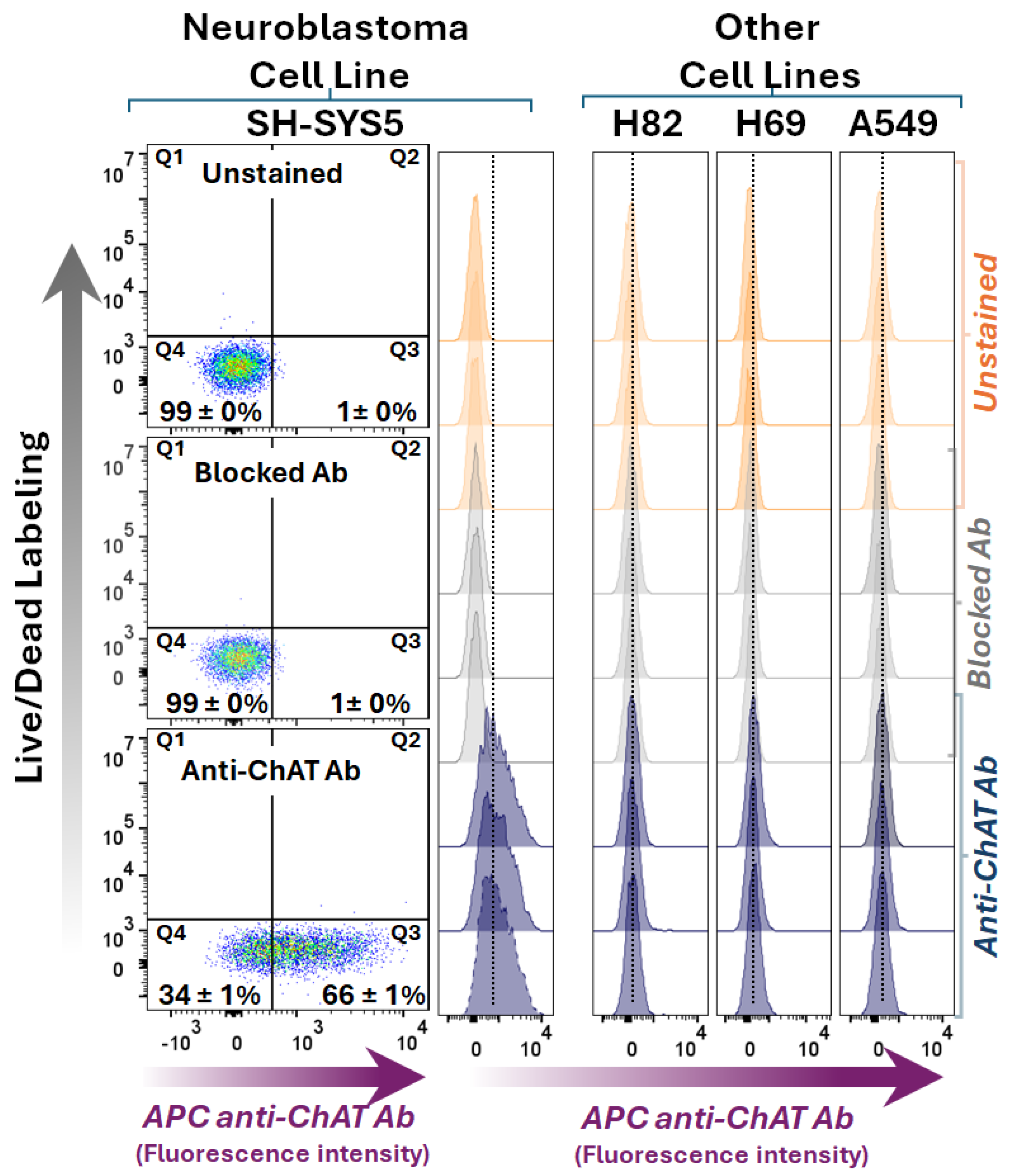

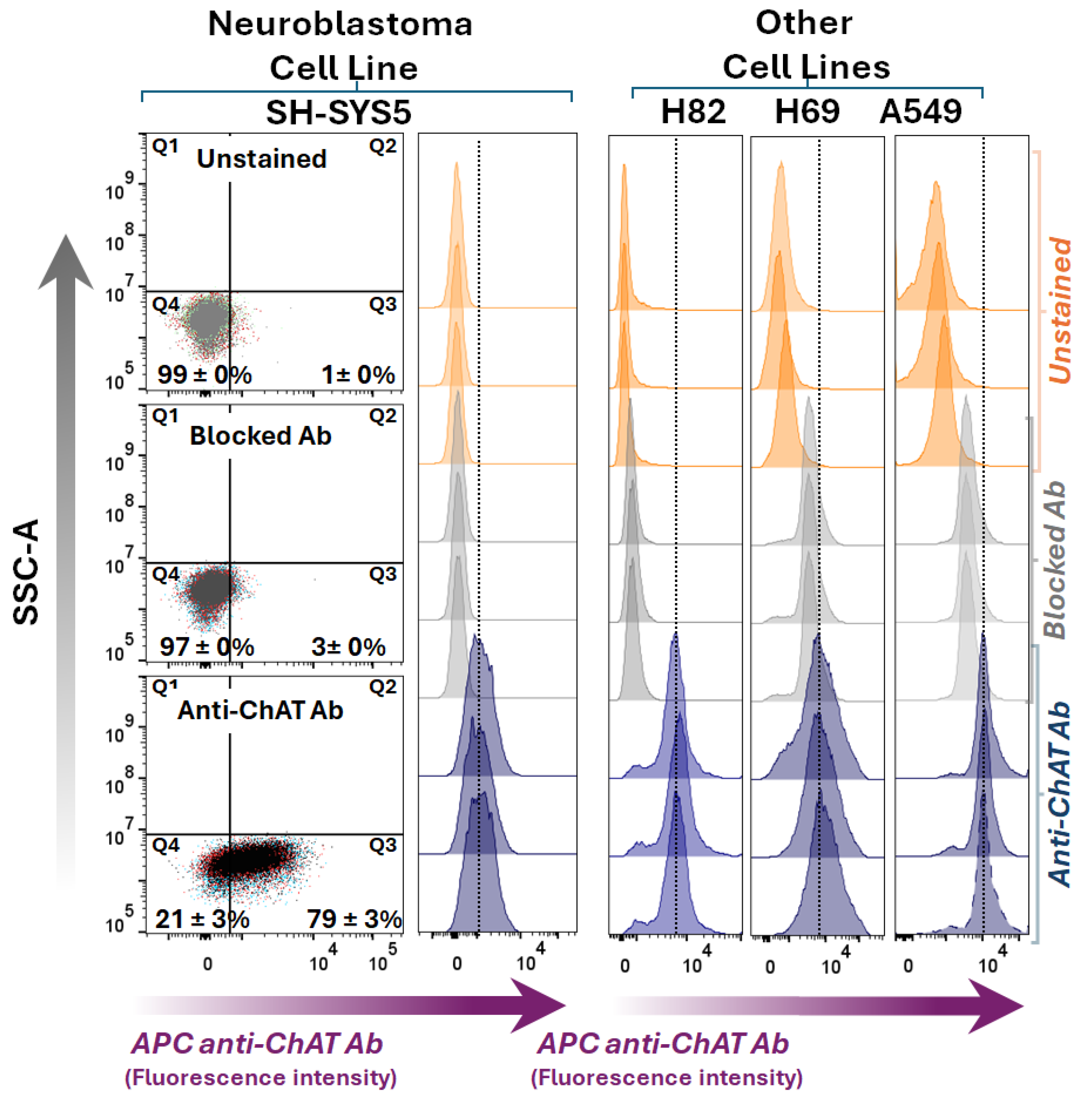

To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the first compelling evidence for the presence of an extracellularly membrane-bound isoform of ChAT in the neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line. Such extracellularly membrane-bound isoform of ChAT was completely absent in the three lung carcinoma cell lines. This was carefully confirmed with confocal microscopic analyses of the cell surface ChAT protein. Nonetheless, we have previously reported a similar extracellularly membrane-bound ChAT in human spermatozoa [

2].

There are reports indicative of the presence of intracellularly membrane-bound ChAT in the synaptic vesicles and synaptosomes in several animal species [

26,

27,

28]. Intriguingly, the synthesized ACh by the membrane-bound ChAT seems to be about forty percent more resistant to hydrolysis by AChE than ACh synthesized by the soluble form of ChAT [

26]. A recent study also showed that human ChAT has a great propensity to attach itself to membrane-like micelles, a phenomenon that results in boosting the activity of the enzyme by over 10-fold [

29]. Therefore, the distinct extracellular localization of ChAT in the neuroblastoma cell line might indicate a novel physiologically implemented cholinergic enhancing mechanism, involving in a fast in-situ synaptic recycling of ACh, granting ACh a prolonged mode of action in the synapses. This is in line with our previous hypothesis about the extracellularly membrane-bound ChAT in human spermatozoa, where in-situ ACh synthesis was proposed to allow ACh to be synthesized in close proximity to its receptor at the membrane, thereby acting timely as a chemotactic agent in sperm, facilitating or governing their motility [

2].

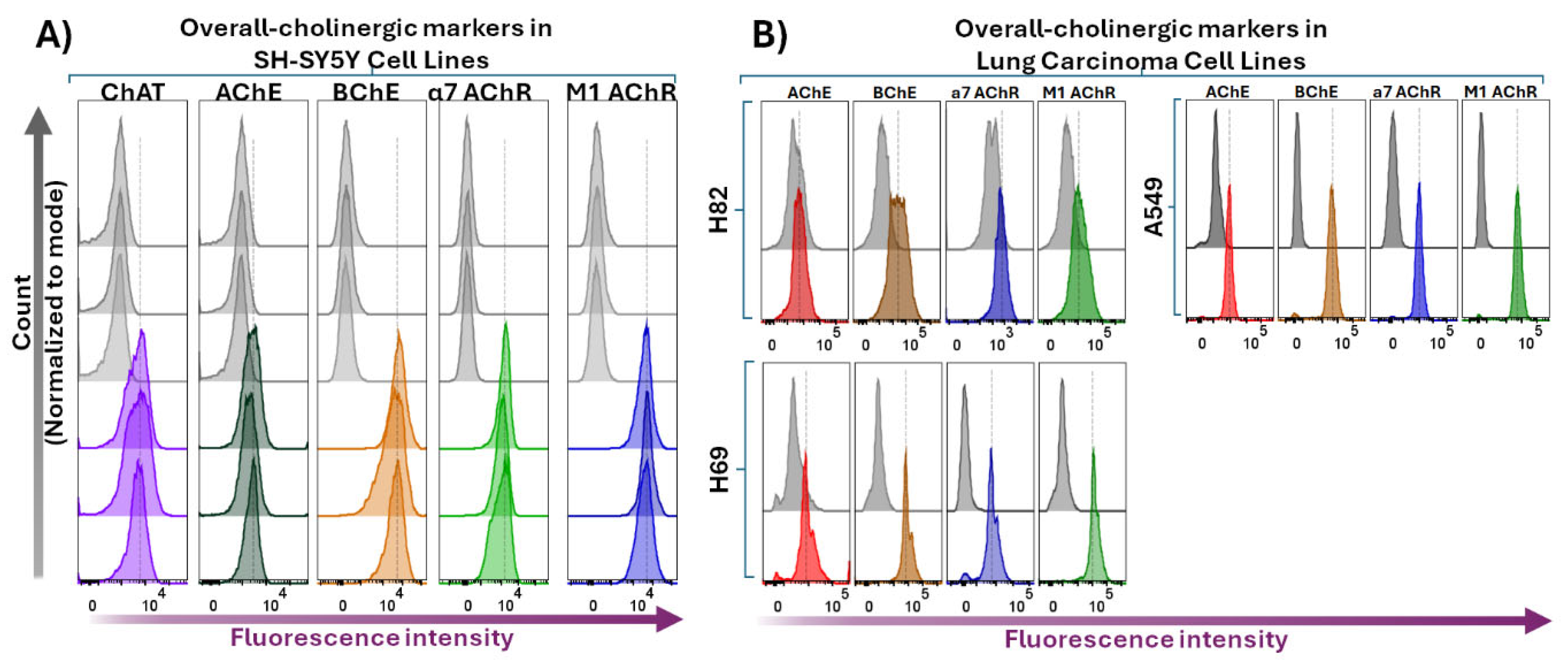

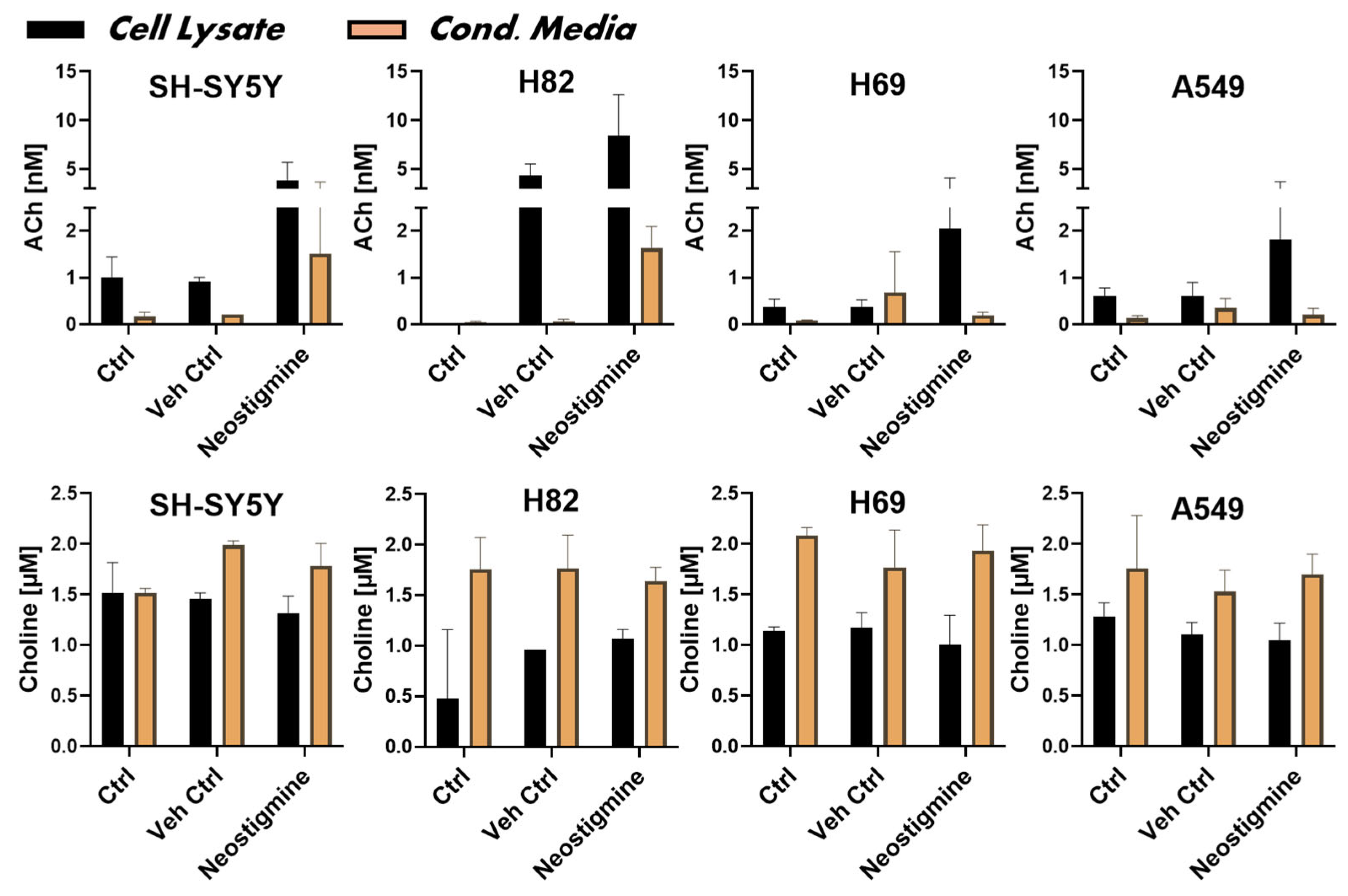

For comparison, we also looked at the expression of ChAT in two SCLC neuroendocrine cell lines i.e., H82 and H69 as well as a NSCLC lung adenocarcinoma cell line, i.e., A549. Although these cells seemed to lack expression of extracellularly membrane-bound ChAT, they clearly had intracellular ChAT staining that was comparable to what was observed in the neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line. Although we just used four cancer cell lines, our results indicate that the extracellular localization of ChAT is not a general phenomenon in cancer cells. To assess whether the expression of ChAT in all these cell lines could have any functional outcome, we measured the production and release levels of ACh. Although the synthesis and release levels seemed to be different in the different cell lines, the results were clear in that all four cell lines did synthesize and release ACh. These findings are in line with previous reports on ACh and choline in human colon cancer cell cultures [

22], as well as in SCLCs, where the H82 cell line exhibited like in our study the highest ACh level compared to the H69 cells [

20].

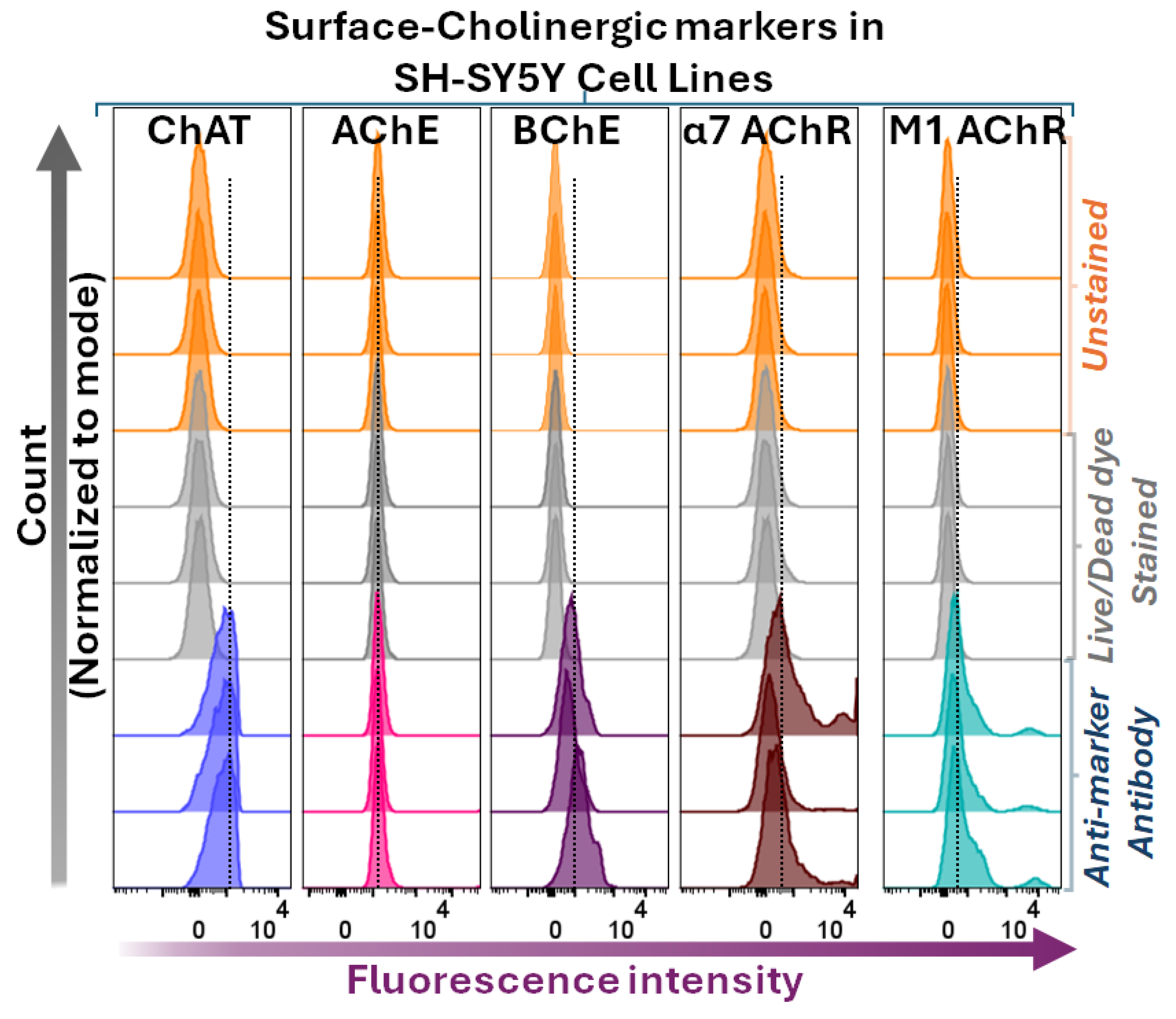

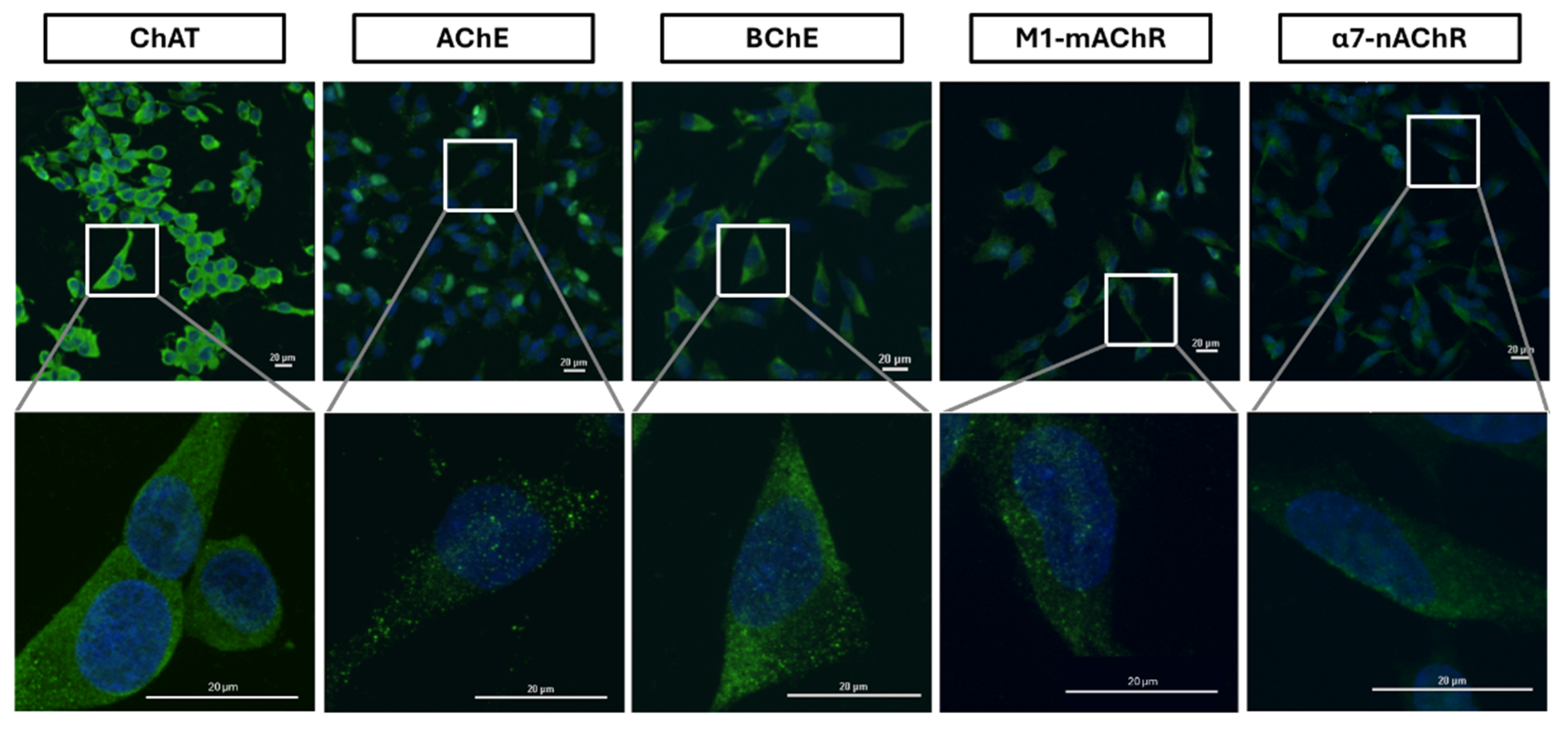

The cholinergic machinery also includes, among other components, various forms of nicotinic and muscarinic ACh receptors (nAChRs and mAChRs) as well as ACh-degrading enzymes (AChE and BChE). Many of these components has been shown in SCLCs [

20,

24,

37]. We therefore also looked at some of these components. In the neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line, we first analysed the presence of surface-localized AChE, BChE, M1-mAChR, and α7-nAChR through both flow cytometric analyses and confocal microscopy. Both M1-mAChR and α7-nAChR were detected extracellularly, which is expected given that these are known as plasma membrane-integrated receptors and been reported in various cancer cells [

23] as well as these cells [

24,

38]. The findings on extracellularly membrane-bound AChE and BChE were, however, surprising, since we found that BChE was the main surface cholinesterase rather than AChE in these cells. The putative view is that AChE is the main ACh hydrolyzing enzyme, present extracellularly as membrane-anchored multimeric molecular forms, for example, on the surface of blood cells, within the neuromuscular junctions, and in the synaptic clefts of the cholinergic interfaces in the brain [

39]. BChE, on the other hand, has putatively been considered a soluble form. Nonetheless, reports in the recent decade point towards the presence of some membrane-anchored AChE-BChE hybrid molecular forms [

40]. Although our findings seem to support this notion, the observation that AChE staining was negligible if not completely absent at the surface of the cells suggests that in the neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line, the membrane-anchored BChE was the dominant form.

Upon membrane permeabilization of the cells, flow cytometric analyses will reflect the overall interaction of the antibody with both the surface and the intracellular target protein expression. A comparison of the overall staining intensity of AChE versus BChE in our flow cytometric data on the neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line indicated that BChE was indeed the much more prevalent enzyme than AChE, supporting the notion that the cells had mainly membrane-anchored BChE. Furthermore, the confocal microscopy results also strongly support this as BChE had an even distribution over the whole cell surface, while AChE presented dotted localized distributions indicative of a discrete focal expression. Nonetheless, this conclusion should be interpreted with caution since two different antibodies against two distinct proteins was used, i.e., given that the antibodies might have different affinity for their target proteins.

Furthermore, we investigated the expression of these cholinergic signaling biomolecules in the lung cancer cell lines, namely the SCLCs H82 and H69 cells, as well as in the lung adenocarcinoma cell line, A549. The results were very similar to that of the neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line, with respect to the expression of not only ChAT and ACh synthesis and release but also the expression pattern of AChE, BChE, M1-mAChR, and α7-nAChR. Noteworthy, even in these three cell lines, the total staining intensity of AChE seemed to be much less than the observed intensity of BChE. Anyway, reports exist for hybrid BChE-AChE molecular forms in human glioma [

41].

Intriguingly, given that the examined cell lines are cancerous cell lines, this phenomenon could be a particular feature of cancer pathology. For instance, it is known that BChE has a scavenging property toward cytotoxic agents ingested naturally via e.g., food sources. Therefore, increasing BChE expression may offer tumour cells a protective line of defence against cytotoxic agents. Indeed, a report has indicated that an increase in BChE levels in the serum of patients with cancer of various tissue origins after treatment compared to their baseline or the healthy controls [

42]. This hypothesis suggest that a screening of the current cytotoxic agents against BChE is warranted to assess which agents is not metabolized by BChE, i.e. could be more effective to use under such conditions.

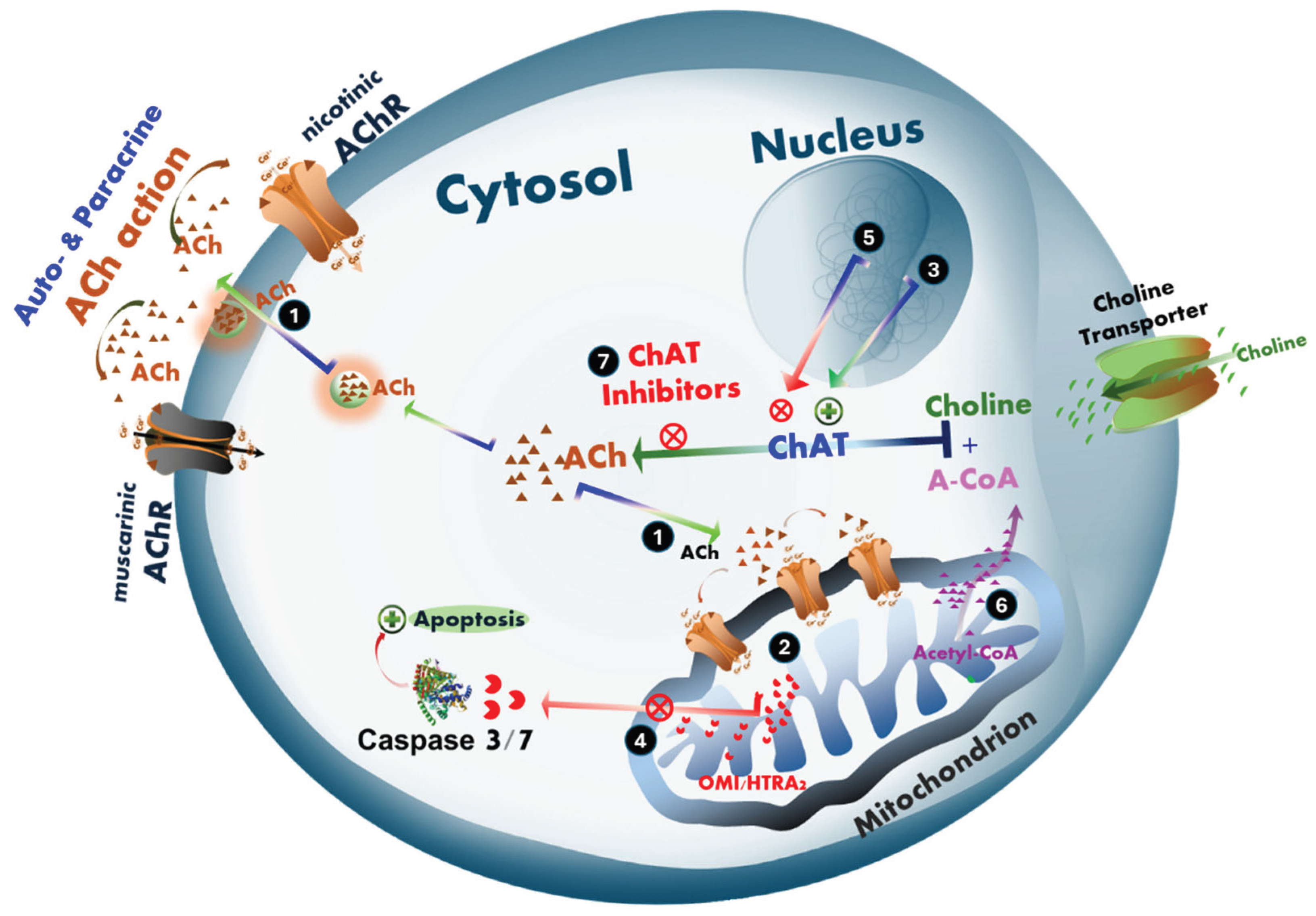

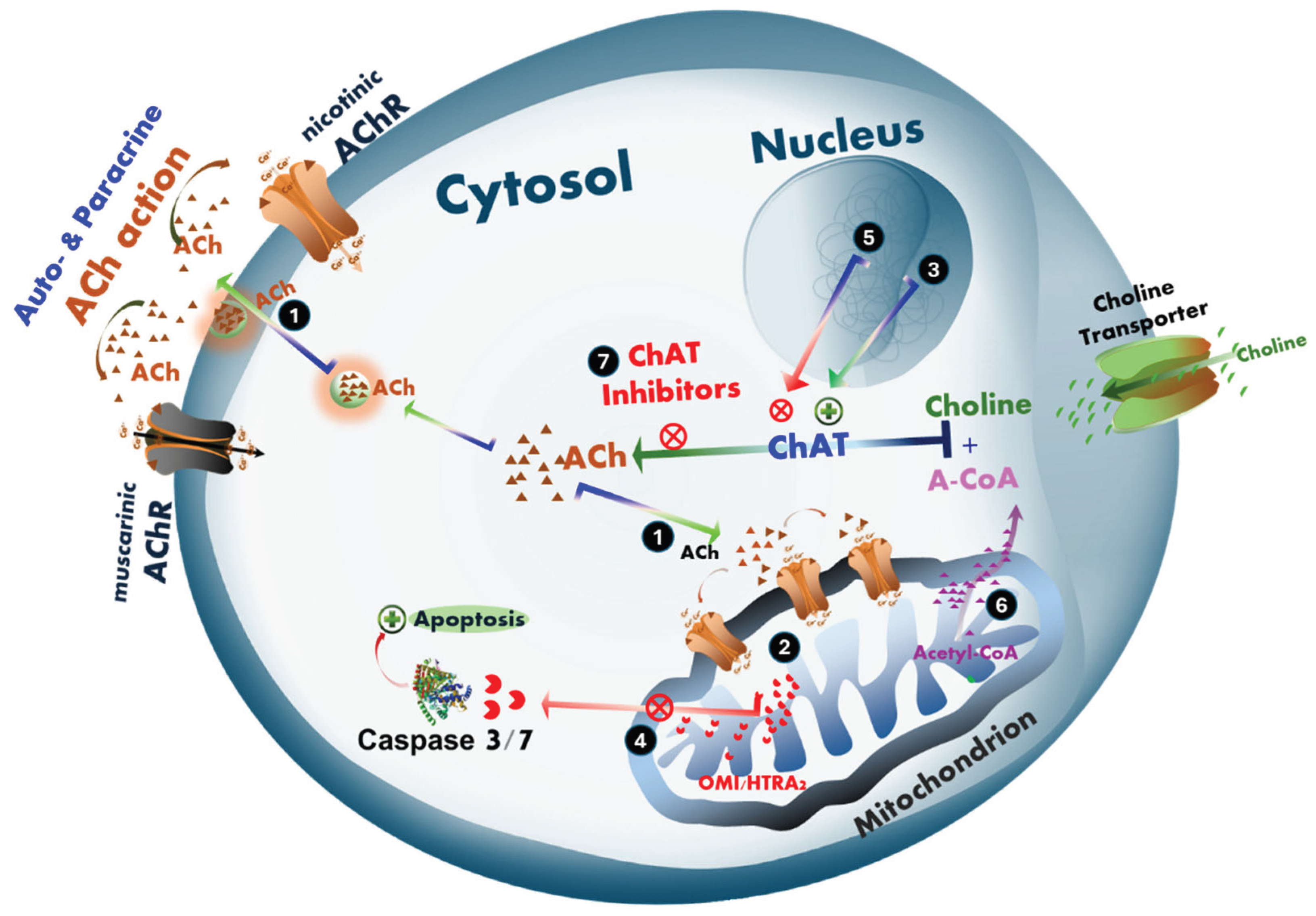

Figure 8.

Hypothetical mechanisms of intracellular cholinergic signaling in the action of acetylcholine involved in promoting cell survival and proliferation in cancer in tumor cells or neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and ALS. (1) ACh promotes cell proliferation and/or survival. We hypothesize that ACh may act through an intracellular signaling mechanism involving the monitoring of mitochondrial bioenergetic function. (2) This mechanism includes regulation of mitochondria-driven apoptosis [

43], which may be differentially affected in the progression of cancer and neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and ALS. (3) In cancer, tumor cells upregulate the expression and activity of the ACh-biosynthesizing enzyme, ChAT, resulting in elevated intracellular ACh levels. (4) Tumor cells exploit this pathway as a protective mechanism against cellular damage caused by, for example, radiotherapy or chemotherapeutics, by suppressing mitochondria-driven apoptosis. This provides more time for DNA damage repair, and thereby increases the likelihood of cell survival, allowing metastatic spread and/or recolonization of the tumor site and potentially cancer relapse. (5) In contrast, in cholinergic neurodegenerative disorders such as AD and ALS, a gradual decline in ChAT expression is observed in neurons. This decline may result from aging, reduced stimulation and/or availability of neurotrophic factors such as NGF, BDNF, or both, and/or the inappropriate use of drugs with anticholinergic effects, including proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and various receptor antagonists. (6) Alternatively or additionally, metabolic and mitochondrial bioenergetic dysfunction may significantly reduce cellular levels of acetyl-Coenzyme A (A-CoA), a co-factor required in equimolar amounts for ACh synthesis by ChAT. A-CoA is primarily produced in mitochondria, where it is partly used in ATP production via the Krebs cycle and partly exported to the cytoplasm for biosynthetic processes including ACh production. Reduced A-CoA production and/or its cytoplasmic availability results in decreased intracellular ACh biosynthesis, compromising the cell’s defense against mitochondria-driven apoptosis. This renders cholinergic neurons more susceptible to degeneration and increasingly sensitive to further anticholinergic insults. (7) This dual-edged mechanistic hypothesis can be tested using selective ChAT inhibitors, such as PPIs [

33], and warrants further investigation. The ACh–mitochondria–apoptosis axis may represent a critical pathway both for understanding the selective cholinergic neurodegeneration in dementia and neuromotor disorders, and as a survival strategy exploited by cancer cells.

Figure 8.

Hypothetical mechanisms of intracellular cholinergic signaling in the action of acetylcholine involved in promoting cell survival and proliferation in cancer in tumor cells or neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and ALS. (1) ACh promotes cell proliferation and/or survival. We hypothesize that ACh may act through an intracellular signaling mechanism involving the monitoring of mitochondrial bioenergetic function. (2) This mechanism includes regulation of mitochondria-driven apoptosis [

43], which may be differentially affected in the progression of cancer and neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and ALS. (3) In cancer, tumor cells upregulate the expression and activity of the ACh-biosynthesizing enzyme, ChAT, resulting in elevated intracellular ACh levels. (4) Tumor cells exploit this pathway as a protective mechanism against cellular damage caused by, for example, radiotherapy or chemotherapeutics, by suppressing mitochondria-driven apoptosis. This provides more time for DNA damage repair, and thereby increases the likelihood of cell survival, allowing metastatic spread and/or recolonization of the tumor site and potentially cancer relapse. (5) In contrast, in cholinergic neurodegenerative disorders such as AD and ALS, a gradual decline in ChAT expression is observed in neurons. This decline may result from aging, reduced stimulation and/or availability of neurotrophic factors such as NGF, BDNF, or both, and/or the inappropriate use of drugs with anticholinergic effects, including proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and various receptor antagonists. (6) Alternatively or additionally, metabolic and mitochondrial bioenergetic dysfunction may significantly reduce cellular levels of acetyl-Coenzyme A (A-CoA), a co-factor required in equimolar amounts for ACh synthesis by ChAT. A-CoA is primarily produced in mitochondria, where it is partly used in ATP production via the Krebs cycle and partly exported to the cytoplasm for biosynthetic processes including ACh production. Reduced A-CoA production and/or its cytoplasmic availability results in decreased intracellular ACh biosynthesis, compromising the cell’s defense against mitochondria-driven apoptosis. This renders cholinergic neurons more susceptible to degeneration and increasingly sensitive to further anticholinergic insults. (7) This dual-edged mechanistic hypothesis can be tested using selective ChAT inhibitors, such as PPIs [

33], and warrants further investigation. The ACh–mitochondria–apoptosis axis may represent a critical pathway both for understanding the selective cholinergic neurodegeneration in dementia and neuromotor disorders, and as a survival strategy exploited by cancer cells.

Furthermore, the presence of the major components of cholinergic machinery, including its key enzyme, ChAT, raises the question of a crucial role of cholinergic signalling in cancer cell biology. Our findings are in full agreement with reports that cholinergic signalling is involved in promoting cell survival and proliferation in various cancer, including lung cancer [

23,

25,

35,

36,

44,

45]. Therefore, it seems imperative to boost the research on the role of cholinergic signalling in cancer biology since it may be involved in the development of tolerance against cellular insults by chemo- and/or radiotherapy, and inhibition of this pathway may increase the efficiency of these treatments.

We have hypothesized that ACh may also act as an intracellular signalling pathway involving monitoring mitochondrial bioenergetic function, and thereby regulation of mitochondria-driven apoptosis [

43], which could be differentially altered in the course of cancer and neurodegenerative diseases like AD and ALS. In our hypothesis, intracellular ACh is a key player in protecting the cells against mitochondria-driven apoptosis (

Figure 8). This might be a key, explaining how two apparently different disorders may have a common key pathological feature. In neurodegenerative disorders (like AD and ALS), a selective neurodegeneration occurs in the central cholinergic neurons and the spinal and peripheral cholinergic motor neurons, as well as the parasympathetic cranial nerves, which is manifested by a severe reduction in ChAT expression [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Thus, here the expected reduction in intracellular ACh biosynthesis by ChAT will lessen the cellular protection against mitochondria-driven apoptosis and thereby facilitate neuronal degeneration. In tumor cells, the opposite seems to be occurring, i.e., the cancer cells are apparently upregulating a pronounced cholinergic phenotype to protect themselves against apoptosis [

20,

24,

37]. Continuous intracellular ACh biosynthesis for maintaining such a protective mechanism is however a very high energy-demanding bioprocess since it requires equimolar amounts of acetyl-CoA (which otherwise is used to produce ATP). This fact therefore strongly indicates that the upregulated ACh signaling in the tumour cells may have been a worthwhile energy investment adopted by these cells, particularly if we also consider how much energy is required by cancer cells for their proliferation alone. Therefore, the acetylcholine-mitochondria-apoptosis axis is a crucial point of investigation for both a proper understanding of the selective cholinergic neurodegeneration occurring in dementia and neuromotor disorders, as well as a survival checkpoint adopted by tumor cells, including neuroblastoma and lung cancer.

In summary, this study provides compelling evidence for the presence of an extracellularly membrane-bound ChAT, exclusively in the neuroblastoma cells as compared to three lung cancer cell lines tested, although all the studied cell lines expressed ChAT intracellularly. All the examined cells also expressed several other components of the cholinergic machinery, reinforcing that the expression of ChAT had a biological purpose in line with ACh signaling. These findings also underscore the complexity of cholinergic signaling, particularly the roles of membrane-bound and intracellular cholinergic markers. Dysregulation of these components is linked to neurodegenerative diseases such as AD, Parkinson’s disease, and ALS. Membrane and intracellular cholinergic markers influence ACh homeostasis, receptor trafficking, apoptotic pathways, and neuroinflammation, making them critical targets for therapeutic interventions. Further studies are needed to elucidate the molecular pathways governing these markers and their potential as therapeutic targets in both neurodegenerative diseases and cancer. Understanding their interactions and regulatory mechanisms could pave the way for strategies to restore cholinergic system integrity and mitigate disease progression.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Antibodies

The following reagents and antibodies were used in the study. Cell culture reagents including RPMI-1640, foetal bovine serum (FBS), trypsin, penicillin, and streptomycin, as well as the fixation and permeabilization buffers (cat # 00-8333-56), were all obtained from Thermofisher Scientific. Cell culture containers (T25 and T75 flasks), cell culture plates, and 15 mL falcon tubes were purchased from Corning for growing and maintaining cell lines. Primary antibodies used were APC (allophycocyanin)-conjugated anti-ChAT antibody (cat # AB224001 from Abcam), unconjugated monoclonal mouse anti-ChAT antibody from (MAB-3447 from R&D System), unconjugated monoclonal mouse anti-ChAT antibody (MAB-31383 from Invitrogen), FITC-conjugated anti-AChE antibody (A-11, Sc-373901-FITC from Santa Cruz), PE-conjugated anti-BChE antibody (D-5, Sc-377403-PE from Santa Cruz), AF647-conjugated anti-α7-AChR antibody (319, Sc-58607-AF647 from Santa Cruz), and PE-conjugated anti-M1-AChR antibody (G-9, Sc-365966-PE from Santa Cruz) for flow cytometric assessment of the expression of cholinergic molecules. For surface staining flow cytometric analyses, the cells were also simultaneously incubated for 20 min with a 1:1500 diluted working solution of the LIVE/DEAD™ Cell Stain dye (cat # L23101, Invitrogen), to ascertain the integrity of the cell membrane, as described before [

2]. For intracellular staining the cells were treated with a permeabilization buffer (Cat # 88-8824-00, eBioscience™ Intracellular Fixation & Permeabilization Buffer Set, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer instruction. Secondary antibodies used were FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody and AF648-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (21244-AF648) from Invitrogen, used in conjunction with the unlabeled primary antibodies. The recombinant human ChAT protein (5.1 mg/mL) was produced and purified by the Protein Science Facility at Karolinska Institutet, as described before [

32].

4.2. Cell Lines

In this work, two human small cell lung carcinoma cell lines NCI-H69 (HTB-119 ™, American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)) and NCI-H82 (HTB-175 ™, ATCC)), one lung adenocarcinoma A549 (CRL-185), and one neuroblastoma cell line (SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC, CRL-2266) were used. All cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Invitrogen), 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Gibco, Invitrogen), and grown in a humidified cell culture incubator in 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. The adherent cells (A549 and SH-SY5Y) were detached by trypsination in 0.25% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA when the cells reached 80–90% confluency.

4.3. Assessment of Cholinergic Markers by Flow Cytometry

For the A549 and SH-SY5Y cells, staining was assessed on confluent cell cultures detaching the cells with trypsination followed by washing in PBS and counting. The small cell human lung cell lines (SCLC) H69 and H82 were maintained as suspension cultures and were centrifuged down for the staining experiment. Approximately 1 × 106 cells were used for the staining of each specific protein. The cell staining was performed as follows; the fixation and permeabilization buffers were prepared and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (cat # 00-8333-56, Thermofisher). Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution (30 µl per flow cytometry tube) for 10 minutes at room temperature (RT). The cells were then washed with 300 µl of PBS containing 0.5% BSA (PBS-0.5%BSA) and centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 15 minutes at 4 °C. Next, cells were permeabilized using permeabilization buffer and incubated with primary antibody at indicated concentrations at 4 °C for 30 minutes. Following this, cells were washed with PBS-0.5%BSA, resuspended in 300 µl of PBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, CytoFLEX S). To confirm the specificity of the ChAT antibody staining, cells were incubated with a 20X concentration of recombinant ChAT protein (~102 μg/mL final concentration) along with the ChAT primary antibody (1/1250 final dilution factor) in the permeabilization solution. These cells were then incubated for 30 minutes at 4 °C, and the staining was performed as above. For the surface staining, the permeabilization step was omitted. A similar staining procedure was applied for the other cholinergic markers, including AChE, BChE, α7-AChR, and M1-AChR with the concentration or dilution of each antibody (1/50 final dilution, all from Santa Cruz). The material details are given in the “Reagents and antibodies” section. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

4.4. Assessment of ACh Levels by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

The cells were collected after being in culture for 24-48 hours, and the cell culture medium was transferred into Eppendorf tubes. After washing in PBS, the cells were counted and homogenized using a steel bead with a 25 s ON / 5 s OFF cycle (2 cycles) generating a cell lysate. The cell lysate was then centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 °C, and the supernatant was transferred to a new Eppendorf tube. Next, 100 µl of pre-chilled acetonitrile (stored at -20 °C) was added to the supernatant, which was vortexed until the solution became cloudy. The sample was centrifuged at 17,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4 °C. Finally, for the LC-MS/MS determination of ACh and choline concentrations in the samples, 50 µl of each sample was transferred to injection vials, followed by the addition of 10 µl of tuning solution (1 µg/ml solution of Acetylcholine-d9 Chloride) to each vial. As a control, an equivalent amount of complete medium (RPMI + FBS) and RPMI alone (without FBS) without any cells were also collected in separate Eppendorf tubes.

4.5. Immunofluorescence Staining of SH-SY5Y Cells for ChAT and Related Cholinergic Markers

When cells reached approximately confluency, they were trypsinized for 5 minutes, and 50,000–70,000 cells/35 mm culture dish were seeded onto a 20 mm glass well (P35G-1.5-20-C, MatTek Corporation) for a 24-hour incubation. Surface and/or intracellular marker staining was carried out using the two-step optimized method described by Vernay and Cosson [

46]. Briefly, cells were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde solution for 10 minutes at 37 °C, followed by the addition of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 45 minutes to block nonspecific binding, omitting permeabilization. To assess the whole-cell staining of the proteins (i.e., both the surface and intracellular proteins), the cells were subjected to a second fixation and were permeabilized with 0.05% Triton-X for 10 minutes before applying primary and secondary antibodies, as described by Vernay and Cosson [

46]. Primary antibodies were applied on ice against mouse monoclonal anti-ChAT (1:70, MAB3447, R&D Systems), rabbit polyclonal anti-ChAT (1:300, PAB14536, Abnova); rabbit polyclonal anti-ChAT (1:70, AB143, Millipore), mouse monoclonal anti-AChE (1:50 or 4 µg/ml, A-11 sc-373901, Santa Cruz), mouse monoclonal anti-BChE (1:50, D-5 sc-377403, Santa Cruz), rat monoclonal anti-α7-nAChR (1:50, sc-58607, Santa Cruz), and mouse monoclonal anti-M1-mAChR (1:50, G-9 sc-365966, Santa Cruz). For visualization, fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies were used: anti-mouse IgG (1:375, goat anti-mouse IgG, FITC, Invitrogen), anti-rabbit IgG (1:300, goat anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 647, Invitrogen), and anti-rat IgG (1:300, goat anti-rat IgG, Alexa Fluor 647, Invitrogen). Nuclei were counterstained with NucBlue DAPI reagent (R37606, Invitrogen). Multipoint spinning disk confocal images or super-resolution (DeepSIM) 3D Z-stack images were captured by Nikon Ti2 inverted microscope using 405, 477, 545 and 637 nm lasers. To ensure optimal data comparability, microscope settings were kept constant throughout all experiments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, TDS, HB, RL and KV; methodology, TDS, BT, ST and LD; formal analysis, TDS, BT and ST; resources, TDS and HB; data curation, TDS, BT, ST and LD; writing—original draft preparation, TDS and BT; writing—review and editing, TDS, HB, BT, ST, LD, RL and KV; visualization, TDS, BT and ST; supervision, TDS and BH; project administration, TDS; funding acquisition, TDS and HB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.