1. Introduction

Organophosphates (OPs) are a class of chemical compounds that have comparable structural properties and have been extensively used as commercial insecticides [

1]. OPs inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE), an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of acetylcholine (ACh) to acetate and choline in synaptic gaps [

2,

3], which explains why excessive central nervous system stimulation leads to respiratory failure and death [

4].

Tetraethyl pyrophosphate (TEPP) is an OP pesticide used in agriculture, food, and drinks that is responsible for high rates of deliberate and incidental poisoning [

5]. Reports suggest that acute toxicity of TEPP in humans can induce systemic effects, such as nausea, weakness, dizziness, loss of vision, tightness of the chest, cramping, and vomiting [

6]. Pesticides risk the environment because spills can pollute soil, water, air, and organisms [

7]. Some of the chemical, physical, and biological procedures used to remove pesticides from aqueous solutions include adsorption, advanced oxidation, membrane filtering, phytoremediation, bioremediation, and the aeration tank approach [

8].

Natural adsorbents might be used to remove pesticides from aqueous solutions [

9]. Cork, a natural, renewable, and biodegradable product, has been suggested as a sustainable adsorbent for a variety of spills of hydrocarbons, oils, solvents and organic compounds [

10,

11]. The presence of lignin and suberin provide hydrophobicity, and the cellulose and hemicellulose high polarity, contributing to potential natural adsorbent [

12]. The application of cork derivates is particularly significant from the perspective of the environment since a renewable component is employed in long-lasting products, increasing CO

2 fixation [

13]. Cork has therefore been utilized as a green alternative because of its porous structure, as well as being a natural raw material with cheap cost, simple access, low density, and biodegradability features [

13,

14,

15].

The effectiveness of corks from

Quercus cerris and

Quercus suber trees in removing pesticides from water was also investigated [

11], using biochemical methods for determining residue pesticides diluted in water samples or studying the efficiency of pesticide removal using natural adsorbent compounds [

11,

12,

16,

17]. After investigating the TEPP effects on AChE activity in commercial enzymes from electric eel (

Electrophorus electricus) and released by neuronal PC12 cells in culture [

18], our group also explored the efficacy of removing TEPP from water using wine corks to create cork granules as a natural adsorbent [

18]. The cork granules were significant as natural adsorbent for TEPP in aquatic settings, with considerable removal efficiencies (95 ± 5% of TEPP diluted in water) [

18]. TEPP solution after adsorbent procedure decreased its inhibitory effects on AChE activity in vitro assays [

18], suggesting that cork granules can be utilized to clean pesticide-contaminated waterways. For the first time, here we report the toxicological effects in vivo of TEPP on the development, behavior, and morphology of embryos and juvenile zebrafish (

Danio rerio), as well as a possible decontamination of the water using cork granules as a natural absorbent in an in vivo model of study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Solutions

TEPP (Pestanal®; > 99.9% purity) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). This pesticide was chosen because it is commonly used in agriculture, and cleaning products, cosmetics, environmental protection, food and beverages, and personal care worldwide. Other chemicals used in the present study were of analytical reagent grade (purity higher than 95%) and purchased from Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corporation (San Diego, CA, USA), Gibco BRL (Gibco-BRL, Waltham, MA, USA) or Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Reconstituted Water Solution

The water was obtained from an artesian well and a public supply in Londrina Londrina (PR, Brazil), and it was dechlorinated twice through an activated carbon filter. The water parameters were measured daily before and after the experiments, including temperature (28 °C), conductivity (56 μS·cm

-1), dissolved oxygen (5.6 mg·L

-1) (Hanna Instruments, Barueri, SP, Brazil) and pH (6.8) (Akso, São Leopoldo, RS, Brazil). The density of fish in aquariums did not exceed 1.0 g·L

-1 of water [

19].

2.3. Zebrafish Collection and Maintenance

Adult wild-type zebrafish (

D. rerio) (n = 100) from the farm Andrade (Vierias, MG, Brazil) were supplied to the Bioassay of the Laboratory of Animal Ecophysiology (LEFA) and Laboratory of Environmental Diagnosis (LADA) of the Department of Physiological Sciences, Center of Biological Sciences, State University of Londrina (PR, Brazil). At a maximum density of 100 animals per bag, the fish were carried in plastic bags (50 × 80 x 0.18 cm) transporting 30 L of water from the fish farm tanks. The plastic bags had 2/3 of the quantity of water and 1/3 of the volume of air to allow for gas exchange during transport. For at least seven days, the fish were acclimatized in tanks of 80 L with dechlorinated water, a biological filter, constant aeration, and a temperature of 28⁰ C maintained by a photoperiod of 14 h - 10 h (light-dark). The water was renewed at a rate of 70% every 24 h, ensuring that ammonia levels (0.01 ± 0.01 ppm) (Labcon-Alcon colorimetric test, Camboriu, SC, Brazil) were consistent with the safety of animals. The fish were fed twice a day with commercial feed (Alcon Basic® MEP 200 Complex), which is designed for ornamental fish development. Adult food was stopped 24 h before the studies and once more throughout the acute tests. After spawning in suitable trays [

20], viable fertilized eggs were picked and exposed on 24-well plates in Petri dishes containing test solution, and the embryos were individually preserved in 2 mL of reconstituted water solution under the light/dark cycle [

21]. The Ethics Committee on the Use of Animals of the State University of Londrina (CEUA/UEL; PR, Brazil) reviewed and approved this work under protocol number CEUA (n° 041.2022).

2.4. Preparation of the Cork Granules

The cork samples were acquired as natural adsorbents from the same brand of wine cork (São Paulo, Brazil). The cork samples were cut into bar geometry with 1.0 cm of length and approximately 3.0 mm of diameter and then triturated to obtain a particle size of 1.0 mm. The stoppers were cleaned in the manner previously described [

22]. They were washed in ultrapure water and the water was renewed until there was no longer any yellow coloring in the water. To reduce the influence of particle adsorption with the analysis, the samples were filtered (Whatman 0.45 m) before analysis. They were then dried in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h before being stored in plastic containers.

2.5. Adsorption Experiments

Adsorption studies were conducted in an Erlenmeyer set containing different amounts of TEPP (0.02, 0.07 or 0.3 µmol·L−1) with or without cork granules at 5 % in a reconstituted water solution. To avoid photodegradation of the pesticide, the flasks were covered with aluminum foil and kept at room temperature (25 ± 2˚C) for a total of 24 h of contact time, with periodic agitation to establish equilibrium. In the same treatment condition mentioned above, control groups were included in our study that reflected only reconstituted water solution or only cork granules at 5 % without TEPP. For the embryo testing, we used the samples were filtered in the filter (PTFE/L 0.22 µm); for the juvenile the samples were not filtered to replicate the environment.

2.6. Experimental Design

For fish embryo toxicity (FET) assays, embryos were chosen at random and divided into seven groups (each group containing 20 embryos) and maintained in a 24-well plate (Nest Biotechnology, Rahway, USA). In each well, one embryo was kept at reconstituted water [

23] in a final volume of 2 mL. The groups were exposed to different treatment condition: untreated (negative control), treated with 3,4-dichloroaniline (DCA; 2 mg·L

-1; positive control), Cork, TEPP (0.02, 0.07 or 0.3 µmol·L

−1) or Cork + TEPP (0.02, 0.07 or 0.3 µmol·L

−1). The embryos were maintained to at 24-, 48-, 72- and 96-hours post-fertilization (hpf) from the fertilization at 26 ± 2 ºC under 14–10 h light-dark cycles. For the behavior experiments, the juvenile fish were (n = 9 per treatment) exposed to TEPP (0.02, 0.07, or 0.3 µmol·L

−1), Cork, Cork + TEPP (0.02, 0.07, or 0.3 µmol·L

−1) or untreated in 2.5 L tanks for 24 h. Feeding was interrupted 24 h before the beginning of the exhibition, and there was no renewal of the medium during the treatments. After that, the juveniles were subjected to light-dark behavioral tests and swimming resistance, and after that, they were sacrificed by immersion in benzocaine (0.1 g·L

-1) and biometrics parameters analyzed.

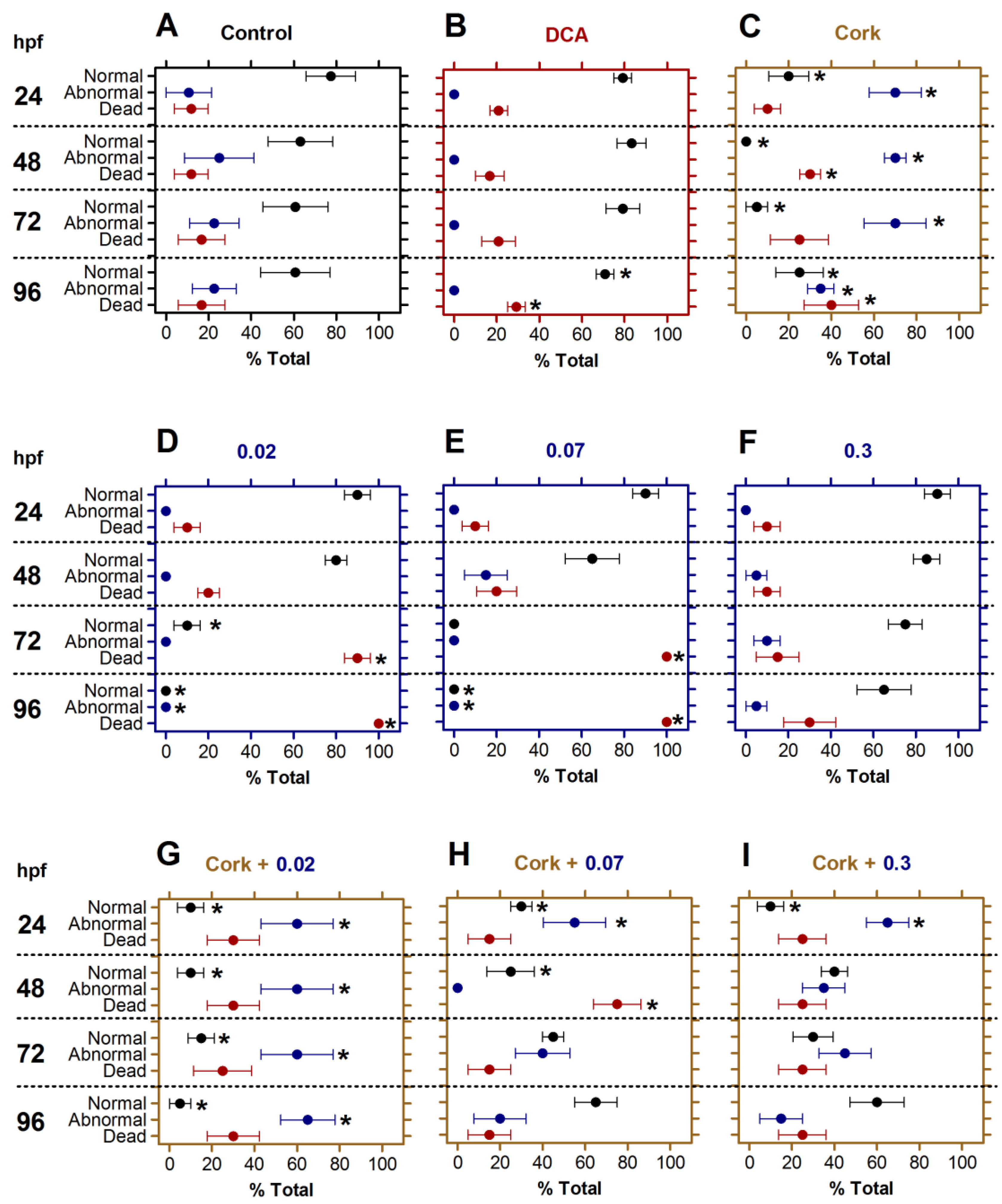

2.7. Fish Embryo Toxicity (FET) Assays

The evaluation of larval development was performed at regular time points (24, 48, 72 and 96 hpf) and the embryos were scored as normal, abnormal or dead; hached/unhatched; using a stereomicroscope (Model SMZ 2 LED, software Optika View Version 7.1.1.5, Optika®. Abnormalities were considered the coagulated embryo, absence of heartbeat, lack of detachment of the tail of the yolk sac and absence of somites. Sublethal parameters such as abnormal development of the head, body axis and yolk sac, edemas, and lack of pigmentation and blood flow [

21,

24]. Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM of viability percentage relative to the control.

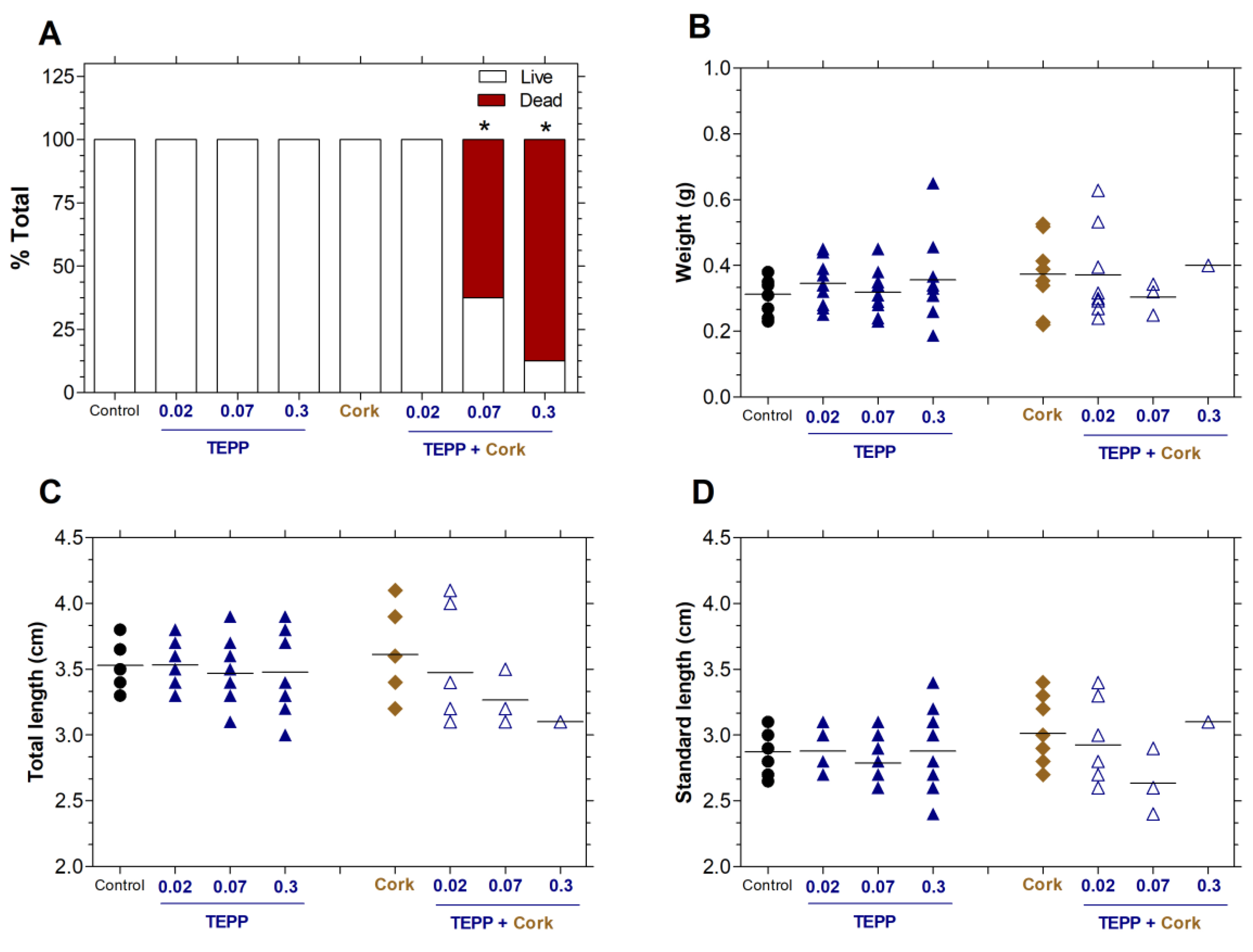

2.8. Biometric Parameters Analyses

Final weight of the fish, total length (from the anterior end of the head to the end of the caudal fin), standard length (from the anterior end of the head to the beginning of the caudal fin insertion), and survival rate (SURV) ([final number of live fish/initial number of fish] x 100) were all measured, according to previous procedure [

21]. After that, the dead fish were frozen and delivered to the State University of Londrina's (PR, Brazil) animal disposal system. Data obtained from final weight (g) total length (cm), and standard length (cm) were expressed as the mean ± SEM. The survival rate (SURV) was represented as a percentage of the total.

2.9. Light-Dark Preference Assay

The light-dark behavioral tests were carried out, according to the literature [

25,

26,

27]. In brief, the animal was placed in a center compartment (5 cm wide) inside a rectangle aquarium fixed with black or white (49 × 18 × 9 cm). After 5 min of acclimatization in the central compartment, the fish was released and filmed for 15 min by the camera installed above the aquarium, with the parameters of time spent in each environment and number of crossings in the midline, as well as the first choice of light or dark, being evaluated. The GeoVision® Gv800 was high-resolution picture capturing software with a resolution of 640 x 480 pixels. The time spent on each environment (s) and number of crossings in the midline were represented as mean ± SEM.

2.10. Swimming Resistance Test

The swimming performance of fish was assessed using an adapted experimental apparatus adapted containing a U-shaped acrylic tube system (30 mm in diameter) connected to a water pump, according to literature [

25,

28]. These experiments were performed after the light-dark behavioral tests sequence. The fish was inserted through a T-shaped opening to swim against the stream of water generated within the system. The flow rate was adjusted by a calibrated water valve to an initial flow rate of 3 L·min

-1 (16.5 cm·s

-1) for fish acclimation. After each minute, the flow rate was increased to 4, 5, 6, and finally 15 L·min

-1. If the fish did not resist the current, it was expelled from the tube into a plastic box attached, in which the exhausted fish could be rescued. After exhaustion, the total swimming time was computed to calculate a swimming endurance index (SEI) according to the following formula:

2.11. Statistical Analysis

All data are always presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Parameters from multiple groups were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey post-hoc test. Whenever data did not meet normality, we employed nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post hoc analysis. Comparisons between two dependent groups (light-dark test) were made using McNemar test. Statistical significance was defined as a value of p < 0.05. GraphPad Prism 6.0 was used to conduct the analysis (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

4. Discussion

Zebrafish (

Danio rerio) is widely recognized as a remarkably effective model for investigating many substances and environments that might cause toxicity [

30,

31]. This is due to its ecological significance, since pollutants tend to flow and accumulate in watercourses and basins, so affecting their chemical and physical properties [

31]. The use of zebrafish in pesticide toxicity studies to capture data on the types of pesticide used, classes of pesticides, and zebrafish life stages associated with toxicity endpoints and phenotypic observations has been widely reported in literature [

32]. In this work, we found that the TEPP, an organophosphorus insecticide extremely toxic used in agriculture and household [

5,

6,

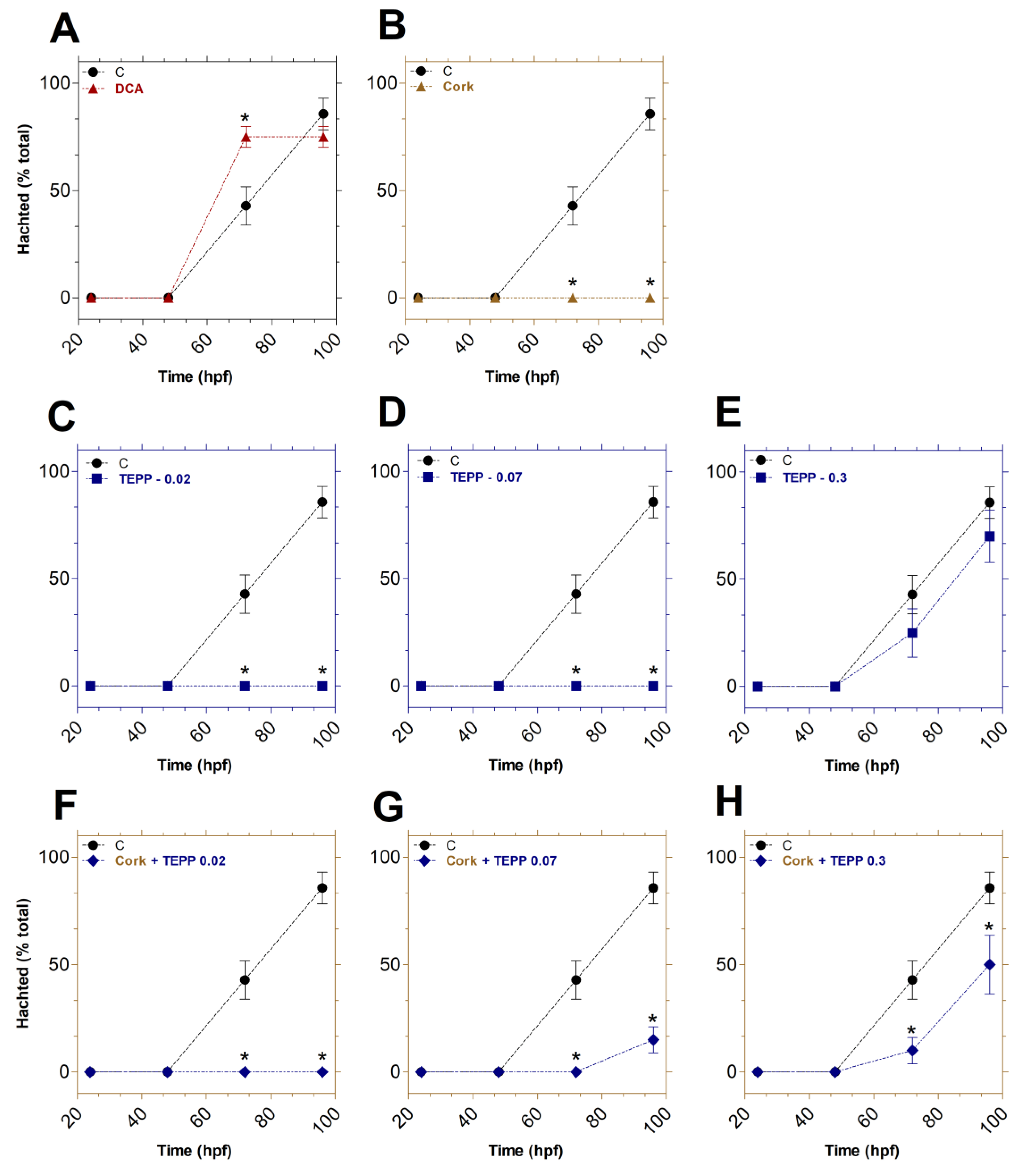

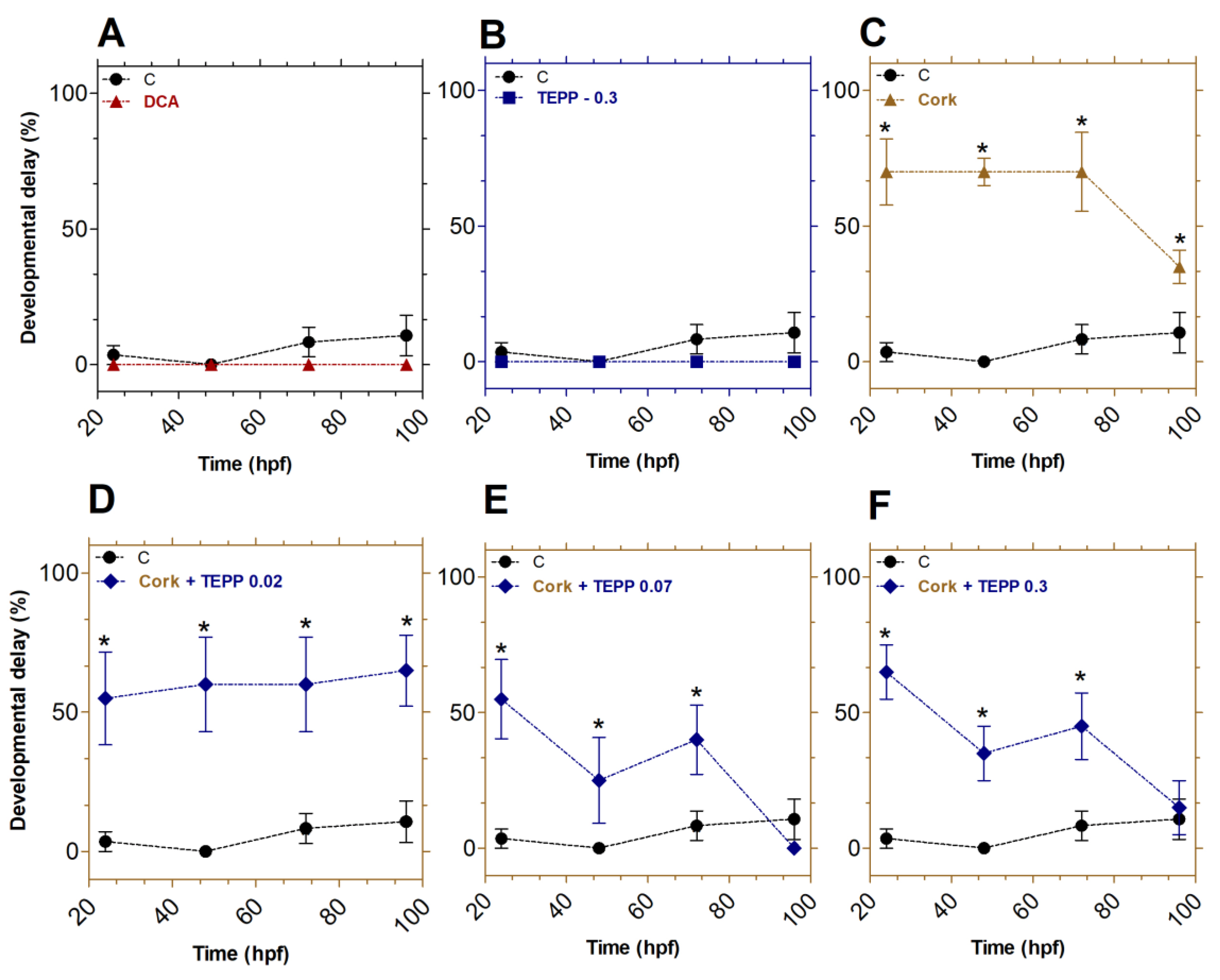

33], decreased the viability rate of embryos after 72 hpf of exposition in a concentration-dependent manner However, it did not affect the development velocity or morphology of the viable embryos. TEPP also altered the behavioral features of juvenile zebrafish, including their preference for light or dark environments and swimming endurance. Additionally, we also investigated the cork granules properties as a natural absorbent for the removal of TEPP diluted in zebrafish water and evaluated the TEPP-induced toxicological effects on the development and behavior of embryos and juvenile zebrafish. Surprisingly, the water derived from cork granules employed in adsorption procedures exhibited reduced viability, delayed the development of embryos and significant alterations in the behavioral parameters of juvenile zebrafish.

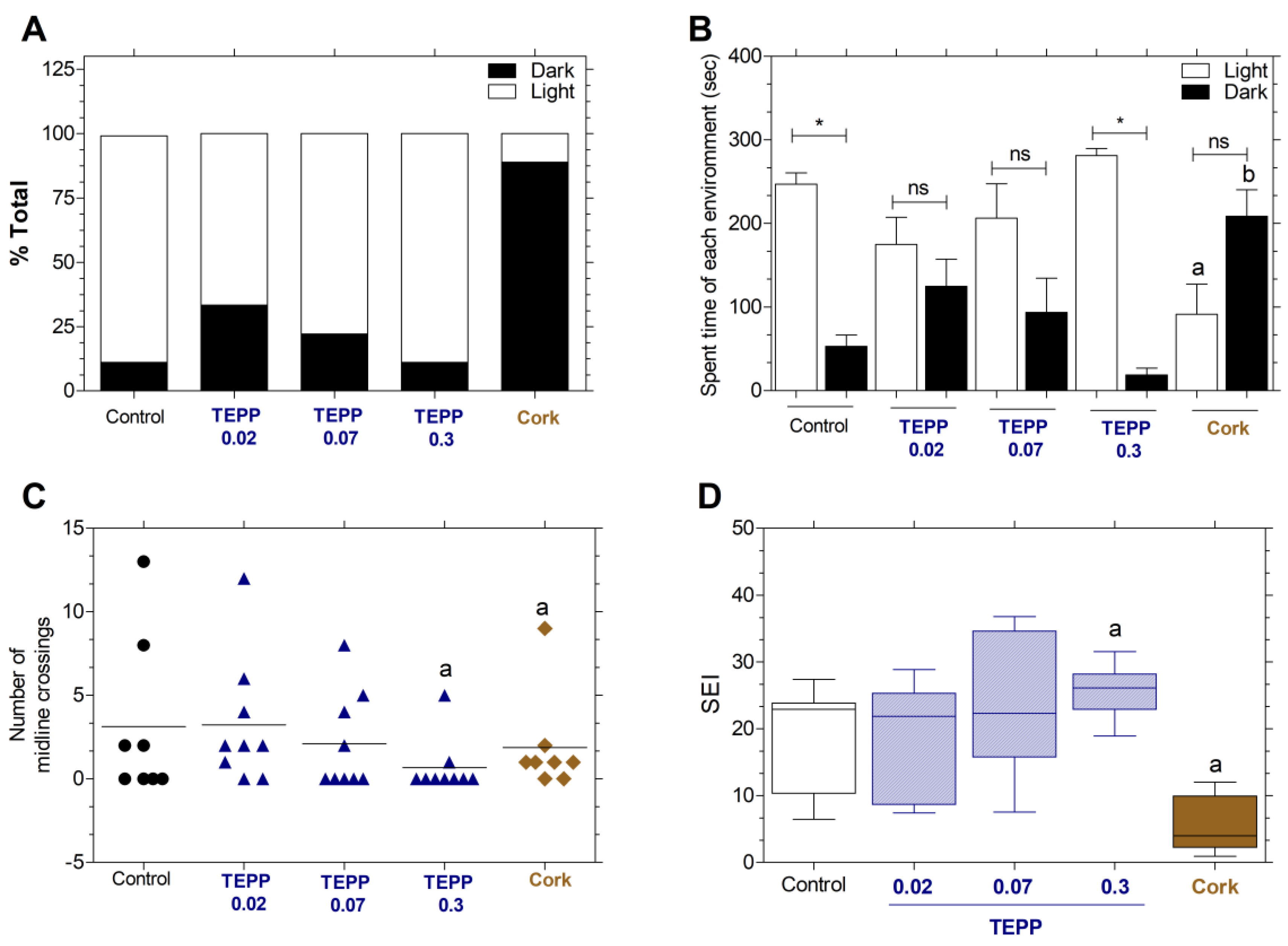

TEPP in concentration ≤ 0.07 µmol·L

-1 after 72 hpf to exposition increased the mortality rate of embryos, but interestingly no alterations were found at 0.3 µmol·L

−1. Likewise, juvenile zebrafish exposed to TEPP at lower concentrations increased preference and spent more time in the dark environment in contrast to the control group. TEPP at 0.02, 0.07, and 0.3 µmol·L

−1 spent 125.0 ± 32.3, 93.5 ± 40.9, and 18.6 ± 8.2 sec in the dark environment in contrast to the control, which showed 53.0 ± 13.5 sec. Our findings suggest that TEPP displayed a typical inverted U-shaped dose-response effect, a nonlinear relationship which has been frequently reported when studying the negative or positive actions of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments [

34]. The inverted U-shaped dose-response effect has also been employed to explain the cholinesterase inhibitors such as MF201, MF268, or MF268 that improve performance at low doses but are ineffective at higher ones [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. TEPP-induced toxicity is explained in part by excessive stimulation of the central nervous system due to irreversible inhibition of AChE activity [

4]. Given that AChE inhibition is widely accepted as the primary mechanism of action of TEPP, we have suggested that their changes in the development and behavior of zebrafish follow a dose-response curve that appears like an inverted U shape, similar to other cholinesterase inhibitors.

The TEPP-induced toxicity was studied

in vitro using the neuronal PC12 cell line, and it was demonstrated that TEPP reduced cell viability in concentrations higher than 10 µmol·L

−1 after 48 h of treatment [

18]. In addition, studies also reported the inhibitory effects of TEPP on commercial AChE [

4,

18] and brain AChE in different tropical fishes showed IC50 (concentration able to inhibit the enzyme in 50% of its activity) higher than 20 µmol·L

−1 [

39]

. Despite that, the toxicological effects of TEPP on the development of embryos and the behavior of juvenile zebrafish were reported at concentrations less than 0.07 µmol·L

−1, which is at least 25 times lower than the effects seen in vitro. This means that the zebrafish model used to study the effects of TEPP in vivo, with larvae at different stages of development and juveniles, was more useful than methods in vitro. Indeed, the zebrafish model has been regarded as an important biological platform for risk assessment and a sensible strategy for testing the toxicity of OP, pyrethroid, azole, and triazine classes of pesticides [

32].

The efficacy of cork granules as natural adsorbents for pesticide removal from water was examined by biochemical and neuronal cell culture approaches [

11,

18], however, no in vivo model studies has been reported yet. Cork is a porous substance composed of prismatic cells arranged in a honeycomb structure [

15]. The water forms clusters around hydrophilic sites on the surface of porous, and diffuses into the cell wall, leading to a swelling of the material [

40]. Physical-chemical interactions and the key binding sites between pesticide molecules and cork determine how the pesticides are retained and how well they can stick to the cork [

10,

41]. Here, we also had the motivation to investigate the efficiency of cork granules for the removal of TEPP from reconstituted water for zebrafish maintenance on the development of embryos and the behavior of juveniles. Unfortunately, the water derived from cork granules after the adsorption experiments induced toxicological effects on embryos and juvenile zebrafish. The use of cork water led to an elevated count of abnormal and dead larvae from 24 to 96 hpf, a decrease in the hatching rate, and a delay in the development of the larvae. In juvenile zebrafish, the cork water did not change viability, weight, total length, or the standard length of the zebrafish; however, it stimulated preference and spent more time in the dark environment, reducing the number of midline crossings and swimming endurance. Despite that, it is important to highlight that cork water did not change neuronal PC12 cell viability in our previous study [

18]. Our data suggest that the zebrafish experiment, performed at different stages of development, displayed increased vulnerability to poisonous substances when compared to in vitro studies. Additional investigation is required to have a comprehensive understanding of the impacts of toxic chemicals incorporated in water cork, which is generated using cork granules obtained from commercially available wine corks.

Cork granules adsorbed over 95% of TEPP diluted in water, decreasing TEPP's inhibitory effects on AChE activity in commercial enzyme from electric eel (

E. electricus) and neuronal PC12 cell culture medium [

18]. Unfortunately, the current investigation revealed that the use of cork granules as an adsorption substrate for removing TEPP diluted in zebrafish water was unsuccessful because toxicological effects were seen on embryos and juvenile zebrafish exposed to cork water. Despite that, Cork + TEPP in higher concentrations appear to alleviate the Cork-induced toxic effects, in particular the hatching rates after 72 hpf and delayed development at 96 hpf, in a concentration-dependent manner. On the other hand, Cork + TEPP in higher concentrations significantly increased the mortality rates of juvenile zebrafish. The underlying differences between embryos and juvenile zebrafish in their response to TEPP + Cork remain unclear and require additional investigation.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the TEPP pesticide changed the viability of the embryos and behavioral juvenile zebrafish in a concentration-dependent manner, assuming a typical inverted U-shaped dose-response curve. TEPP also altered the preference for light or dark environments and swimming endurance of juvenile zebrafish without changing their viability or biometric parameters. In addition, the use of wine cork granules tested as a natural adsorbent for TEPP in aquatic settings was not efficient due to increased abnormal and dead rates, a delay in the development of the larvae, or by stimulating behavioral stress in juvenile zebrafish. Furthermore, the application of wine cork granules as a natural adsorbent for TEPP in aquatic settings revealed to be ineffective due to elevated rates of abnormality and mortality, a delayed development of the larvae, or the induction of behavioral stress in juvenile zebrafish, in contrast to what was reported in in vitro studies.

Author Contributions

F.B.M.M.: conceptualization, writing—original draft, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization; L.V.R.d.S.: methodology, investigation; A.G.M.: supervision, validation, funding acquisition; E.F.V.: supervision, validation, funding acquisition; P.C.M.: supervision, validation, methodology, investigation; C.A.-S.: writing—original draft, supervision, validation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Figure 1.

Toxicity of TEPP and cork + TEPP on embryos viability. Embryos were untreated (A) or treated with DCA (B), Cork solution (C), TEPP [0.02 (D), 0.07 (E), or 0.3 (F) µmol·L−1], or Cork + TEPP [0.02 (G), 0.07 (H), or 0.3 (I) µmol·L−1]. The embryos viability rates were scored as normal, abnormal, or dead after 24, 48, 72, and 92 hpf of treatment. Values were expressed as mean ± SEM (% total) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc. Significant differences from the negative control group (untreated) are indicated by * p < 0.05 in relation to the negative control group. hpf: hours post-fertilization; DCA: 3,4-dichloroaniline (2 mg·L-1; positive control); TEPP: Tetraethyl pyrophosphate.

Figure 1.

Toxicity of TEPP and cork + TEPP on embryos viability. Embryos were untreated (A) or treated with DCA (B), Cork solution (C), TEPP [0.02 (D), 0.07 (E), or 0.3 (F) µmol·L−1], or Cork + TEPP [0.02 (G), 0.07 (H), or 0.3 (I) µmol·L−1]. The embryos viability rates were scored as normal, abnormal, or dead after 24, 48, 72, and 92 hpf of treatment. Values were expressed as mean ± SEM (% total) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc. Significant differences from the negative control group (untreated) are indicated by * p < 0.05 in relation to the negative control group. hpf: hours post-fertilization; DCA: 3,4-dichloroaniline (2 mg·L-1; positive control); TEPP: Tetraethyl pyrophosphate.

Figure 2.

The impact of TEPP and cork + TEPP on the hatching rates of zebrafish embryos. Embryos were treated with DCA (A), Cork water (B), TEPP [0.02 (C), 0.07 (D), or 0.3 (E) µmol·L−1], Cork + TEPP [0.02 (F), 0.07 (G), or 0.3 (H) µmol·L−1]. Values were expressed as mean ± SEM (% total) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc. Significant differences from the negative control group (untreated) are indicated by * p < 0.05 in relation to the negative control group. hpf: hours post-fertilization; DCA: 3,4-dichloroaniline (2 mg·L-1; positive control); TEPP: Tetraethyl pyrophosphate.

Figure 2.

The impact of TEPP and cork + TEPP on the hatching rates of zebrafish embryos. Embryos were treated with DCA (A), Cork water (B), TEPP [0.02 (C), 0.07 (D), or 0.3 (E) µmol·L−1], Cork + TEPP [0.02 (F), 0.07 (G), or 0.3 (H) µmol·L−1]. Values were expressed as mean ± SEM (% total) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc. Significant differences from the negative control group (untreated) are indicated by * p < 0.05 in relation to the negative control group. hpf: hours post-fertilization; DCA: 3,4-dichloroaniline (2 mg·L-1; positive control); TEPP: Tetraethyl pyrophosphate.

Figure 3.

TEPP and cork + TEPP effects on zebrafish development. Embryos were treated with DCA (A), TEPP at 0.3 µmol·L−1 (B), Cork solution (C), or Cork + TEPP [0.02 (D), 0.07 (E), or 0.3 (F) µmol·L−1]. Values were expressed as mean ± SEM (% total) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc. Significant differences from the negative control group (untreated) are indicated by * p < 0.05 in relation to the negative control group. hpf: hours post-fertilization; DCA: 3,4-dichloroaniline (2 mg·L-1; positive control); TEPP: Tetraethyl pyrophosphate.

Figure 3.

TEPP and cork + TEPP effects on zebrafish development. Embryos were treated with DCA (A), TEPP at 0.3 µmol·L−1 (B), Cork solution (C), or Cork + TEPP [0.02 (D), 0.07 (E), or 0.3 (F) µmol·L−1]. Values were expressed as mean ± SEM (% total) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc. Significant differences from the negative control group (untreated) are indicated by * p < 0.05 in relation to the negative control group. hpf: hours post-fertilization; DCA: 3,4-dichloroaniline (2 mg·L-1; positive control); TEPP: Tetraethyl pyrophosphate.

Figure 4.

TEPP and cork + TEPP exposition on zebrafish juveniles. (A) Survival rate of zebrafish after 24h of different exposures with TEPP (0.02, 0.07 or 0.3 µmol·L−1), Cork, and Cork + TEPP (0.02, 0.07 or 0.3 µmol·L−1, expressed as a percentage of the total. The live fish were sacrificed, and (B) weight, (C) total length, and (D) standard length were measured and expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 9-10 per group). One-way ANOVA was employed for the statistical evaluation, followed by Tukey post hoc. Significant differences from the negative control group (untreated) are indicated by * p < 0.05 in relation to the negative control group. TEPP: Tetraethyl pyrophosphate.

Figure 4.

TEPP and cork + TEPP exposition on zebrafish juveniles. (A) Survival rate of zebrafish after 24h of different exposures with TEPP (0.02, 0.07 or 0.3 µmol·L−1), Cork, and Cork + TEPP (0.02, 0.07 or 0.3 µmol·L−1, expressed as a percentage of the total. The live fish were sacrificed, and (B) weight, (C) total length, and (D) standard length were measured and expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 9-10 per group). One-way ANOVA was employed for the statistical evaluation, followed by Tukey post hoc. Significant differences from the negative control group (untreated) are indicated by * p < 0.05 in relation to the negative control group. TEPP: Tetraethyl pyrophosphate.

Figure 5.

Effects of TEPP and cork in the light-dark test and swimming endurance index. (A) First choice of light or dark. (B) Time spent in each environment. (C) Number of crossings in the midline. (D) Swimming endurance index (SEI). Juveniles Danio rerio (n = 9-10 per group) were submitted to an endurance test after 24 h of exposure to TEPP (0.02, 0.07 or 0.3 µmol·L−1) and Cork The spent in each environment was expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 9-10 per group) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey post hoc. (A-C) The letters represent differences in time spent on light environments in the treated groups vs light environment controls (a) and on dark environments in the treated groups vs dark environment controls (b); asterisks indicate a significant difference in the time spent between both environments; ns: no significant difference among treatments was observed. (D) p < 0.05 in relation to the control group (untreated) (a). TEPP: Tetraethyl pyrophosphate.

Figure 5.

Effects of TEPP and cork in the light-dark test and swimming endurance index. (A) First choice of light or dark. (B) Time spent in each environment. (C) Number of crossings in the midline. (D) Swimming endurance index (SEI). Juveniles Danio rerio (n = 9-10 per group) were submitted to an endurance test after 24 h of exposure to TEPP (0.02, 0.07 or 0.3 µmol·L−1) and Cork The spent in each environment was expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 9-10 per group) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey post hoc. (A-C) The letters represent differences in time spent on light environments in the treated groups vs light environment controls (a) and on dark environments in the treated groups vs dark environment controls (b); asterisks indicate a significant difference in the time spent between both environments; ns: no significant difference among treatments was observed. (D) p < 0.05 in relation to the control group (untreated) (a). TEPP: Tetraethyl pyrophosphate.