Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Data Analysis

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Financial Disclosures

Abbreviations

| AEs | adverse events |

| H&Y | Hoenh & Yahr |

| DD | disease duration |

| LEDD | levodopa equivalent daily dose |

| NMS | non-motor symptoms |

| NMSS | Non-Motor Symptoms Scale |

| PD | Parkinson´s disease |

| PDQ-39SI | 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire Summary Index |

| QoL | quality of life |

References

- Willis AW, Roberts E, Beck JC, Fiske B, Ross W, Savica R, Van Den Eeden SK, Tanner CM, Marras C; Parkinson’s Foundation P4 Group. Incidence of Parkinson disease in North America. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2022;8:170.

- Armstrong MJ, Okun MS. Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Review. JAMA. 2020;323:548-60.

- Barone P, Antonini A, Colosimo C, et al.; PRIAMO study group. The PRIAMO study: A multicenter assessment of nonmotor symptoms and their impact on quality of life in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2009;24:1641-9.

- Martinez-Martin P, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Kurtis MM, Chaudhuri KR; NMSS Validation Group. The impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life of patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2011;26:399-406.

- Santos García D, de Deus Fonticoba T, Suárez Castro E, et al.; Coppadis Study Group. Non-motor symptoms burden, mood, and gait problems are the most significant factors contributing to a poor quality of life in non-demented Parkinson's disease patients: Results from the COPPADIS Study Cohort. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 019;66:151-57.

- Santos-García D, de la Fuente-Fernández R. Impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related and perceived quality of life in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Sci 2013;332:136-40.

- Bloem BR, Okun MS, Klein C. Parkinson's disease. Lancet 2021;397:2284-303.

- Fox SH, Katzenschlager R, Lim SY, et al.; Movement Disorder Society Evidence-Based Medicine Committee. International Parkinson and movement disorder society evidence-based medicine review: Update on treatments for the motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2018;33:1248-66.

- Simuni T, Okun MS. Adjunctive Therapies in Parkinson Disease-Have We Made Meaningful Progress? JAMA Neurol 2022;79:119-20.

- Stocchi F, Vacca L, Radicati FG. How to optimize the treatment of early stage Parkinson's disease. Transl Neurodegener 2015;4:4.

- Fabbri M, Rosa MM, Abreu D, Ferreira JJ. Clinical pharmacology review of safinamide for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag 2015;5:481-96.

- Abbruzzese G, Kulisevsky J, Bergmans B, et al.; SYNAPSES Study Investigators Group. A European Observational Study to Evaluate the Safety and the Effectiveness of Safinamide in Routine Clinical Practice: The SYNAPSES Trial. J Parkinsons Dis 2022;12:473.

- Borgohain R, Szasz J, Stanzione P, et al.; Study 016 Investigators. Randomized trial of safinamide add-on to levodopa in Parkinson's disease with motor fluctuations. Mov Disord 2014;29:229-37.

- Borgohain R, Szasz J, Stanzione P, et al.; Study 018 Investigators. Two-year, randomized, controlled study of safinamide as add-on to levodopa in mid to late Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2014;29:1273-80.

- Stocchi F, Torti M. Adjuvant therapies for Parkinson's disease: critical evaluation of safinamide. Drug Des Devel Ther 2016;10:609-18.

- Espinoza-Vinces C, Villino-Rodríguez R, Atorrasagasti-Villar A, Martí-Andrés G, Luquin MR. Impact of Safinamide on Patient-Reported Outcomes in Parkinson's Disease. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2023;14:285-95.

- Stocchi F, Antonini A, Berg D, et al. Safinamide in the treatment pathway of Parkinson's Disease: a European Delphi Consensus. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2022;8:17.

- Blair HA, Dhillon S. Safinamide: A Review in Parkinson's Disease. CNS Drugs 2017;31:169-76.

- Cattaneo C, Jost WH, Bonizzoni E. Long-Term Efficacy of Safinamide on Symptoms Severity and Quality of Life in Fluctuating Parkinson's Disease Patients. J Parkinsons Dis 2020;10:89-97.

- Bianchi MLE, Riboldazzi G, Mauri M, Versino M. Efficacy of safinamide on non-motor symptoms in a cohort of patients affected by idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Neurol Sci 2019;40:275-9.

- Santos García D, Labandeira Guerra C, Yáñez Baña R, et al. Safinamide Improves Non-Motor Symptoms Burden in Parkinson's Disease: An Open-Label Prospective Study. Brain Sci 2021;11:316.

- Santos García D, Yáñez Baña R, Labandeira Guerra C, et al. Pain Improvement in Parkinson's Disease Patients Treated with Safinamide: Results from the SAFINONMOTOR Study. J Pers Med 2021;11:798.

- Labandeira CM, Alonso Losada MG, Yáñez Baña R, et al. Effectiveness of Safinamide over Mood in Parkinson's Disease Patients: Secondary Analysis of the Open-label Study SAFINONMOTOR. Adv Ther 2021;38(10):5398-5411.

- Santos García D, Cabo López I, Labandeira Guerra C, et al. Safinamide improves sleep and daytime sleepiness in Parkinson's disease: results from the SAFINONMOTOR study. Neurol Sci 2022;43:2537-2544.

- Daniel SE, Lees AJ. Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank, London: overview and research. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1993;39:165-72.

- Dubois B, Burn D, Goetz C, et al. Diagnostic procedures for Parkinson's disease dementia: recommendations from the movement disorder society task force. Mov Disord 2007;22:2314-24.

- Chaudhuri KR, Martinez-Martin P, Brown RG, et al. The metric properties of a novel non-motor symptoms scale for Parkinson's disease: Results from an international pilot study. Mov Disord 2007;22(13):1901-11.

- Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Peto V, Greenhall R, Hyman N. The Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39): development and validation of a Parkinson's disease summary index score. Age Ageing 1997;26(5):353-7.

- Virameteekul S, Phokaewvarangkul O, Bhidayasiri R. Profiling the most elderly parkinson's disease patients: Does age or disease duration matter? PLoS One 2021;22;16:e0261302.

- Peretz C, Chillag-Talmor O, Linn S, et al. Parkinson's disease patients first treated at age 75 years or older: a comparative study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014;20:69-74.

- Dahodwala N, Pettit AR, Jahnke J, et al. Use of a medication-based algorithm to identify advanced Parkinson's disease in administrative claims data: Associations with claims-based indicators of disease severity. Clin Park Relat Disord 2020;3:100046.

- Schade S, Mollenhauer B, Trenkwalder C. Levodopa Equivalent Dose Conversion Factors: An Updated Proposal Including Opicapone and Safinamide. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2020;7:343-5.

- Sharaf J, Williams KD, Tariq M, Acharekar MV, Guerrero Saldivia SE, Unnikrishnan S, Chavarria YY, Akindele AO, Jalkh AP, Eastmond AK, Shetty C, Rizvi SMHA, Mohammed L. The Efficacy of Safinamide in the Management of Parkinson's Disease: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022;14:e29118.

- Plastino M, Gorgone G, Fava A, et al. Effects of safinamide on REM sleep behavior disorder in Parkinson disease: A randomized, longitudinal, cross-over pilot study. J Clin Neurosci 2021;91:306-12.

- Qureshi AR, Rana AQ, Malik SH, et al. Comprehensive Examination of Therapies for Pain in Parkinson's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2018;51:190-206.

- Nishikawa N, Hatano T, Nishioka K, et al.; J-SILVER study group. Safinamide as adjunctive therapy to levodopa monotherapy for patients with Parkinson's disease with wearing-off: The Japanese observational J-SILVER study. J Neurol Sci 2024;461:123051.

- Rinaldi D, Bianchini E, Sforza M, et al. The tolerability, safety and efficacy of safinamide in elderly Parkinson's disease patients: a retrospective study. Aging Clin Exp Res 2021;33:1689-92.

- Lo Monaco MR, Petracca M, Vetrano DL, et al. Safinamide as an adjunct therapy in older patients with Parkinson's disease: a retrospective study. Aging Clin Exp Res 2020;32:1369-73.

- Kulisevsky J, Esquivel A, Freire-Álvarez E, et al. SYNAPSES. A European observational study to evaluate the safety and the effectiveness of safinamide in routine clinical practice: post-hoc analysis of the Spanish study population. Rev Neurol 2023;77:1-12.

- Peña E, Borrué C, Mata M, et al. Impact of SAfinamide on Depressive Symptoms in Parkinson's Disease Patients (SADness-PD Study): A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Brain Sci. 2021;11:232.

- Liguori C, Stefani A, Ruffini R, Mercuri NB, Pierantozzi M. Safinamide effect on sleep disturbances and daytime sleepiness in motor fluctuating Parkinson's disease patients: A validated questionnaires-controlled study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018;57:80-81.

- Geroin C, Di Vico IA, Squintani G, Segatti A, Bovi T, Tinazzi M. Effects of safinamide on pain in Parkinson's disease with motor fluctuations: an exploratory study. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2020;127:1143-52.

- Santos-García D, Laguna A, Hernández-Vara J, et al. On Behalf Of The Coppadis Study Group. Sex Differences in Motor and Non-Motor Symptoms among Spanish Patients with Parkinson's Disease. J Clin Med 2023;12:1329.

- Gómez-López A, Sánchez-Sánchez A, Natera-Villalba E, et al. SURINPARK: Safinamide for Urinary Symptoms in Parkinson's Disease. Brain Sci 2021;11:57.

- De Micco R, Satolli S, Siciliano M, et al. Effects of safinamide on non-motor, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms in fluctuating Parkinson's disease patients: a prospective longitudinal study. Neurol Sci 2022;43:357-64.

- Pellecchia MT, Picillo M, Russillo MC, et al. Efficacy of Safinamide and Gender Differences During Routine Clinical Practice. Front Neurol 2021;12:756304.

- Cattaneo C, Jost WH. Pain in Parkinson's Disease: Pathophysiology, Classification and Treatment. J Integr Neurosci 2023;22:132.

- Beiske AG, Loge JH, Rønningen A, Svensson E. Pain in Parkinson's disease: Prevalence and characteristics. Pain 2009;141:173-7.

- Cattaneo C, Kulisevsky J, Tubazio V, Castellani P. Long-term Efficacy of Safinamide on Parkinson's Disease Chronic Pain. Adv Ther 2018;35:515-522.

- Qureshi AR, Rana AQ, Malik SH, et al. Comprehensive Examination of Therapies for Pain in Parkinson's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuroepidemiology 2018;5:190-206.

- Stocchi F, Borgohain R, Onofrj M, et al.; Study 015 Investigators. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of safinamide as add-on therapy in early Parkinson's disease patients. Mov Disord 2012;27:106-12.

- Cattaneo C, Barone P, Bonizzoni E, Sardina M. Effects of Safinamide on Pain in Fluctuating Parkinson's Disease Patients: A Post-Hoc Analysis. J Parkinsons Dis 2017;7:95-101.

- Cattaneo C, Sardina M, Bonizzoni E. Safinamide as Add-On Therapy to Levodopa in Mid- to Late-Stage Parkinson's Disease Fluctuating Patients: Post hoc Analyses of Studies 016 and SETTLE. J Parkinsons Dis 2016;6:165-73.

- Tsuboi Y, Hattori N, Yamamoto A, Sasagawa Y, Nomoto M; ME2125-4 Study Group. Long-term safety and efficacy of safinamide as add-on therapy in levodopa-treated Japanese patients with Parkinson's disease with wearing-off: Results of an open-label study. J Neurol Sci 2020.;416:117012.

- Hayes, MT. Parkinson's Disease and Parkinsonism. Am J Med 2019;132:802-07.

- Martinez-Martin P, Falup Pecurariu C, Odin P, et al. Gender-related differences in the burden of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol. 2012 Aug;259(8):1639-47.

- Pellecchia MT, Picillo M, Russillo MC, Andreozzi V, Oliveros C, Cattaneo C. The effects of safinamide according to gender in Chinese parkinsonian patients. Sci Rep 2023;13:20632.

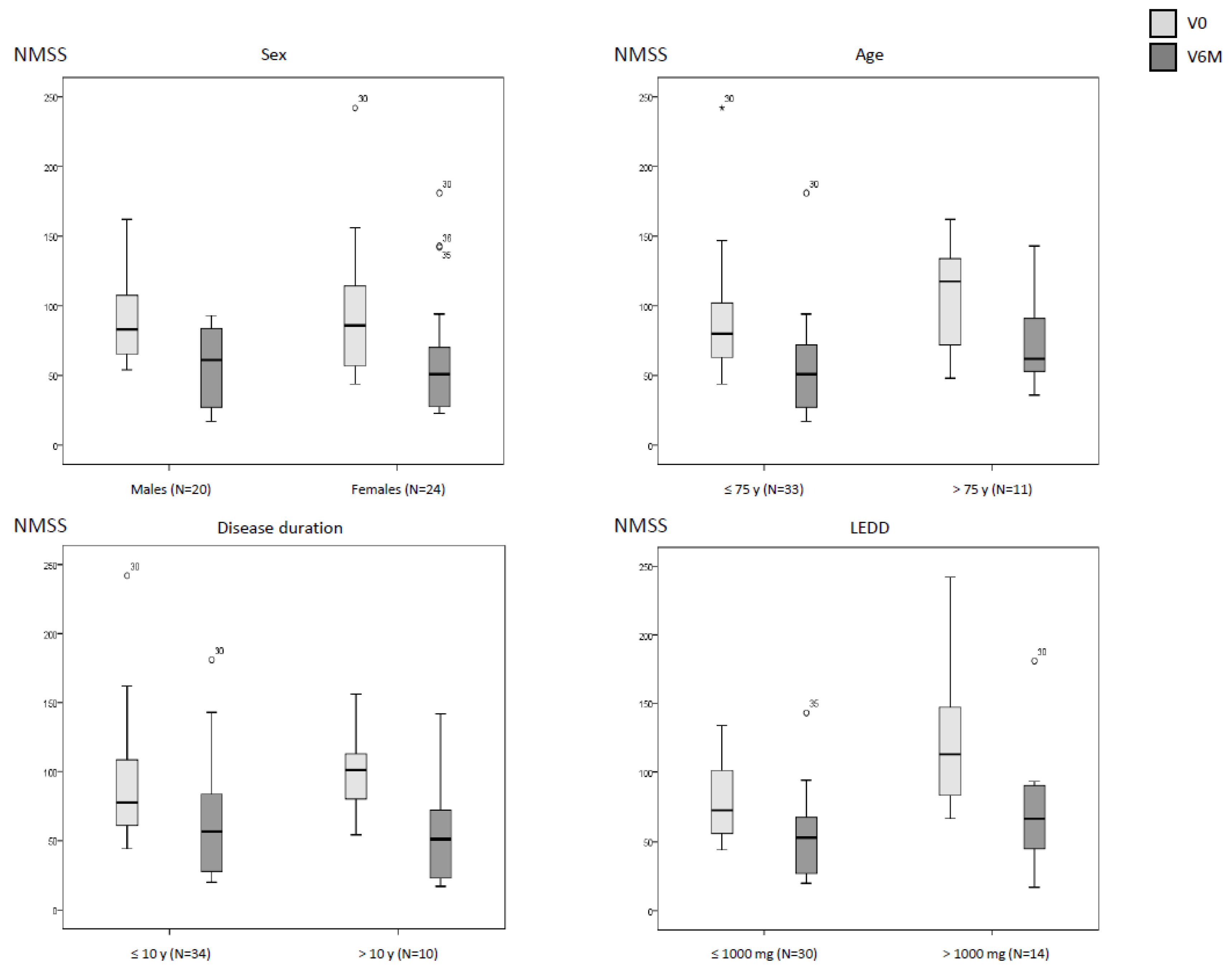

| At V0 | At V6M | Cohen´s d | pa | pb | pc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sex Males (N=20) Females (N=24) |

93.6 ± 32.4 93.6 ± 45.2 |

59.4 ± 27.7 60.4 ± 41.5 |

-1.8 -1.3 |

<0.0001 0.001 |

0.629 | 0.494 |

|

Age ≤ 75 y (N=33) > 75 y (N=11) |

88.6 ± 38.9 108.7 ± 38.6 |

54.2 ± 34 77.2 ± 35.6 |

-1.9 -1.0 |

<0.0001 0.040 |

0.069 | 0.050 |

|

Disease duration ≤ 10 y (N=34) > 10 y (N=10) |

90.7 ± 41.1 102 ± 35.1 |

61.6 ± 35.5 55.2 ± 38.7 |

-1.4 -1.9 |

<0.0001 0.015 |

0.353 | 0.268 |

|

LEDD ≤ 1000 mg (N=30) > 1000 mg (N=14) |

80.9 ± 28.1 121.3 ± 49 |

53.6 ± 28.2 68.2 ± 43.1 |

-1.4 -1.7 |

<0.0001 0.002 |

0.004 | 0.425 |

| Males (N=20) |

Females (N=24) |

≤ 75 y old (N=33) |

> 75 y old (N=11) |

≤ 10 y DD (N=34) |

> 10 y DD (N=10) |

≤ 1000mg LEDD (N=30) |

> 1000 mg LEDD (N=14) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

8.8 ± 12.1 8.8 ± 12.3 0.0 0.838 |

8.7 ± 11.4 5 ± 9.7 -0.4 0.244 |

7.5 ± 11.1 3.8 ± 7.5 -0.4 0.077 |

12.5 ± 12.9 15.5 ± 14.9 0.3 0.552 |

9.3 ± 11.1 7.3 ± 11.1 -0.2 0.298 |

6.7 ± 13.4 4.6 ± 10.5 -0.2 0.785 |

8.9 ± 11.3 7.1 ± 11.4 -0.2 0.385 |

8.3 ± 12.6 5.9 ± 10.2 -0.3 0.483 |

| Sleep / fatigue At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

34.9 ± 16 19.2 ± 15.2 -1.6 <0.0001 |

34 ± 23.7 26.5 ± 19.9 -0.4 0.253 |

35.3 ± 20.4 21.3 ± 16.4 -1.0 0.001 |

31.8 ± 21 28.6 ± 22.4 -0.2 0.755 |

34.9 ± 19.7 23.8 ± 19.4 -0.7 0.008 |

32.7 ± 23.6 21 ± 13.4 -0.6 0.126 |

31.3 ± 16.8 23.9 ± 19.5 -0.5 0.045 |

41.2 ± 25.9 21.6 ± 15.3 -1.0 0.023 |

| Mood / apathy At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

26.3 ± 11.5 11.5 ± 12.9 -1.5 0.001 |

36.3 ± 30 17 ± 23.8 -1.2 <0.0001 |

30.5 ± 27.8 12.7 ± 19.6 -1.4 <0.0001 |

35.3 ± 24.6 19.9 ± 19.6 -1.1 0.040 |

27.2 ± 26.5 14.2 ± 20.6 -1.2 <0.0001 |

47.3 ± 22.4 15.4 ± 16.9 -2.2 0.005 |

25 ± 22.7 11.3 ± 13.6 -1.2 <0.0001 |

46 ± 30.1 21.3 ± 28.1 -1.6 0.004 |

| Perceptual symptoms At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

3.9 ± 7.8 4.6 ± 7.9 0.1 0.866 |

3.4 ± 7.3 1.4 ± 2.7 -0.4 0.301 |

3.7 ± 6.5 2.8 ± 6.1 -0.1 0.336 |

3.2 ± 9.9 2.8 ± 5.4 -0.1 0.989 |

4.3 ± 8.3 2.9 ± 5.6 -0.2 0.432 |

1.4 ± 2.6 2.5 ± 6.9 0.19 0.891 |

2.7 ± 6.6 2.3 ± 4.9 -0.1 0.759 |

5.6 ± 8.8 3.9 ± 7.7 -0.2 0.475 |

| Attention / memory At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

20.6 ± 17.6 14 ± 17.1 -0.9 0.010 |

14 ± 17.4 12.7 ± 19.4 -0.1 0.482 |

16.4 ± 15.9 11.1 ± 12.3 -0.7 0.006 |

18.7 ± 22.7 19.9 ± 29.5 0.1 0.858 |

15.2 ± 17.4 11.5 ± 17.3 -0.6 0.020 |

23.1 ± 17.9 19.4 ± 20.6 -0.3 0.553 |

13.2 ± 15.4 9.6 ± 15.2 -0.5 0.032 |

25 ± 19.9 21.2 ± 21.9 -0.3 0.373 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

19.9 ± 17.6 11.9 ± 11.4 -1.0 0.019 |

17.4 ± 16.6 14.1 ± 14.7 -0.3 0.148 |

16.1 ± 15.8 10.5 ± 11.7 -0.6 0.027 |

25.8 ± 18.8 20.9 ± 14.9 -0.4 0.090 |

19.3 ± 17.5 14.6 ± 12.9 -0.5 0.042 |

15.6 ± 15.2 8.1 ± 13.3 -0.5 0.108 |

17.9 ± 16.1 11.8 ± 12 -0.7 0.014 |

19.6 ± 19.2 16.1 ± 15.5 -0.3 0.278 |

| Urinary symptoms At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

45 ± 29.3 37.2 ± 25.4 -0.4 0.251 |

42.7 ± 30.7 25.1 ± 21.6 -1.1 <0.0001 |

40.3 ± 26.3 29.9 ± 25.7 -0.6 0.034 |

54 ± 37.9 32.5 18.6 -1.2 0.021 |

44.8 ± 29.6 33.6 ± 25.2 -0.7 0.012 |

40 ± 31.8 20.6 ± 16.6 -0.8 0.086 |

37.5 ± 26.4 28.3 ± 20.9 -0.6 0.031 |

57.1 ± 33.1 35.5 ± 29.8 -1.1 0.039 |

| Sexual dysfunction At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

40.2 ± 36.4 32.1 ± 33.9 -0.3 0.672 |

19.4 ± 33.8 17.2 ± 32.9 -0.2 0.812 |

23.4 ± 31.8 20.4 ± 32.3 -0.1 0.823 |

45.4 ± 44.3 39.8 ± 34.4 -0.2 0.888 |

31.5 ± 37.7 27.6 ± 34.7 -0.1 0.875 |

20 ± 30.1 17.5 ± 29.8 -0.3 0.565 |

24 ± 31.1 18.6 ± 26.7 -0.2 0.639 |

39.3 ± 44.7 39.6 ± 42.5 0.0 0.799 |

| Miscellaneous At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

29.2 ± 21 16 ± 12.1 -1.2 0.002 |

34.5 ± 21.1 21.4 ± 15.3 -1.1 0.002 |

30.6 ± 21.1 19.5 ± 14.7 -1.1 <0.0001 |

36.3 ± 21 17.4 ± 12.3 -1.4 0.013 |

30.2 ± 18 18.7 ± 11.6 -1.0 <0.0001 |

38.3 ± 29.4 19.8 ± 21.1 -1.6 0.012 |

29.9 ± 19 18.9 ± 11.4 -1.0 0.001 |

36.8 ± 24.1 19.1 ± 19 -1.6 0.003 |

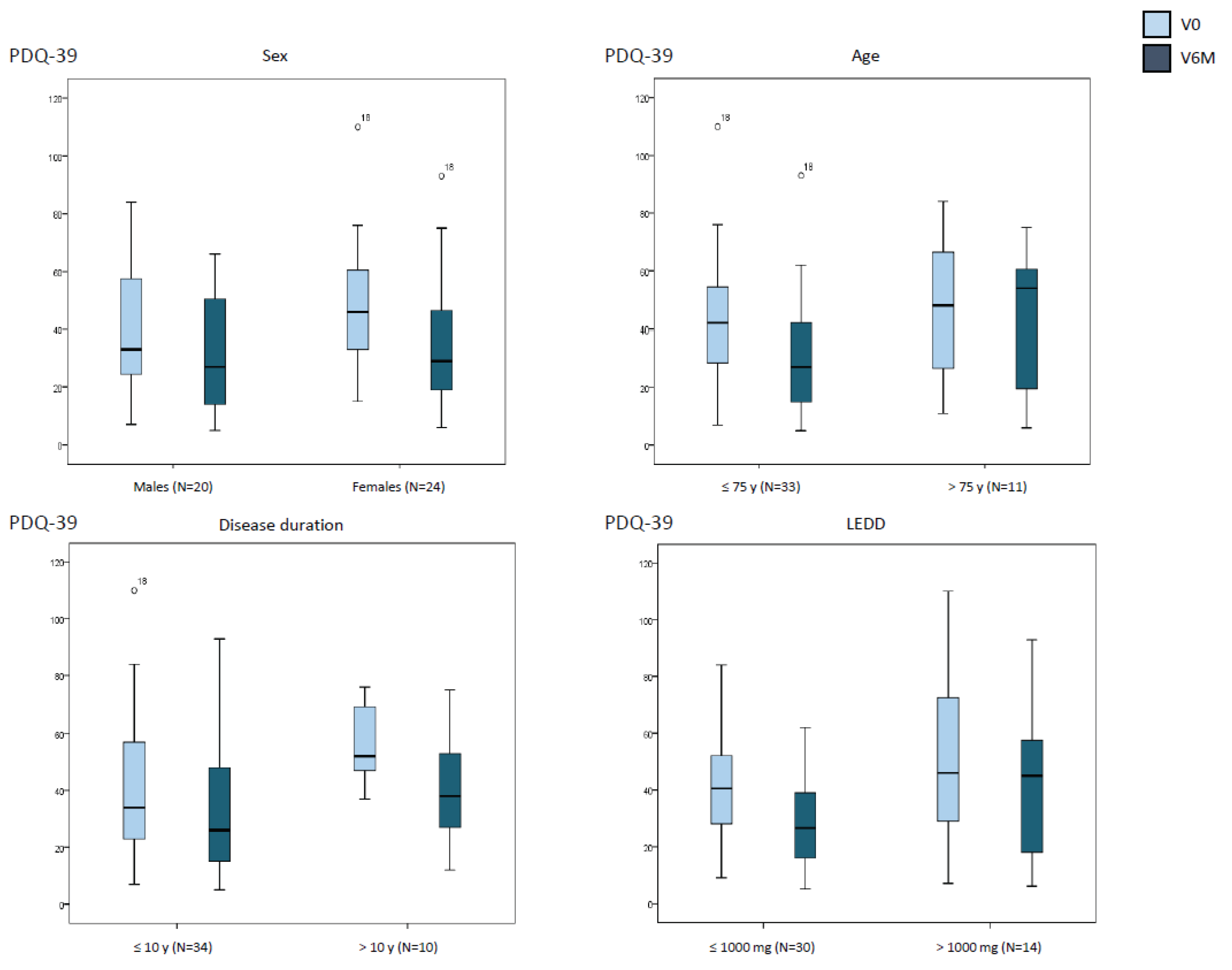

| At V0 | At V6M | Cohen´s d | pa | pb | Pc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sex Males (N=20) Females (N=24) |

39.1 ± 23.3 48.3 ± 22.1 |

32.4 ± 20.2 34.5 ± 22.7 |

-0.5 -1.4 |

0.080 <0.0001 |

0.202 | 0.741 |

|

Age ≤ 75 y (N=33) > 75 y (N=11) |

43.2 ± 22.2 46.7 ± 25.6 |

30.4 ± 19.8 42.4 ± 24 |

-1.4 -0.3 |

<0.0001 0.306 |

0.632 | 0.124 |

|

Disease duration ≤ 10 y (N=34) > 10 y (N=10) |

40.3 ± 23.5 57.9 ± 14.2 |

31.2 ± 21.5 42.1 ± 19.9 |

-0.8 -2.1 |

0.0020.011 |

0.009 | 0.105 |

|

LEDD ≤ 1000 mg (N=30) > 1000 mg (N=14) |

40.9.9 ± 18.5 50.6 ± 31.8 |

29.1 ± 17.1 41.9 ± 26.8 |

-1.1 -0.6 |

<0.0001 0.119 |

0.391 | 0.265 |

| Males (N=20) |

Females (N=24) |

≤ 75 y old (N=33) |

> 75 y old (N=11) |

≤ 10 y DD (N=34) |

> 10 y DD (N=10) |

≤ 1000mg LEDD (N=30) |

> 1000 mg LEDD (N=14) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

22.3 ± 30.3 23.5 ± 22.8 0.1 0.584 |

42.5 ± 27.6 33.8 ± 29.4 -0.6 0.017 |

31.4 ± 25.9 23.5 ± 22.7 -0.7 0.004 |

38.9 ± 28.2 45.9 ± 32.1 0.5 0.592 |

28.3 ± 25.7 25.9 ± 25.6 -0.2 0.184 |

50.3 ± 21.9 40 ± 29.5 -0.9 0.074 |

30.5 ± 20.7 24.3 ± 20.4 -0.5 0.021 |

39.3 ± 35.7 39.2 ± 35.9 0.0 0.574 |

| Activities of daily living At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

24.6 ± 23.4 18.3 ± 18.1 -0.5 0.244 |

27.6 ± 22.1 17.4 ± 18.2 -0.8 0.019 |

25.3 ± 21.9 14.9 ± 15.6 -0.9 0.002 |

29.2 ± 24.9 26.5 ± 22.2 -0.2 0.964 |

22.4 ± 20.2 14.8 ± 15.4 -0.6 0.047 |

39.2 ± 25.9 27.9 ± 22.9 -0.8 0.114 |

23.1 ± 21.8 15.2 ± 15.3 -0.6 0.119 |

33 ± 23.2 23.2 ± 22.3 -0.8 0.073 |

| Emotional well-being At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

31.4 ± 23.4 22.1 ± 20.9 -0.8 0.040 |

48.4 ± 27 29.8 ± 24.4 -1.3 <0.0001 |

40.4 ± 26.9 24.6 ± 24.1 -1.1 <0.0001 |

42.4 ± 27.1 31.4 ± 19.6 -1.0 0.052 |

38.6 ± 26.6 26.6 ± 23.3 -0.9 0.002 |

48.3 ± 26.7 25.4 ± 23 -1.9 0.008 |

39.4 ± 24.2 23.1 ± 20.2 -1.1 <0.0001 |

44.2 ± 32.3 33.3 ± 27.7 -1.1 0.022 |

| Stigmatization At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

21.7 ± 25.4 11.9 ± 16.1 -0.6 0.070 |

9.1 ± 10.9 4.2 ± 8.9 -0.5 0.107 |

13.9 ± 18.8 6.8 ± 12 -0.5 0.057 |

17 ± 22.4 10.2 ± 16.3 -0.9 0.063 |

14.4 ± 18.9 6.4 ± 12.3 -0.6 0.011 |

15.6 ± 22.4 11.8 ± 15.4 -0.3 0.492 |

15.4 ± 18.7 9.6 ± 14.4 -0.6 0.024 |

12.9 ± 21.9 3.6 ± 8.7 -0.5 0.207 |

| Social support At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

7.5 ± 8.7 3.3 ± 11.3 -0.4 0.121 |

4.5 ± 10.7 3.8 ± 193.9 -0.1 0.752 |

5.2 ± 9.1 4.3 ± 14.4 -0.1 0.651 |

7.6 ± 12 1.5 ± 3.8 -0.7 0.131 |

4.5 ± 8.9 2.2 ± 8.8 -0.3 0.181 |

10 ± 12.3 8.3 ± 21.1 -0.2 0.750 |

5 ± 9.7 4.4 ± 14.9 -0.1 0.643 |

7.7 ± 10.5 1.8 ± 4.8 -0.7 0.111 |

| Cognition At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

27.9 ± 20.9 28.4 ± 25.3 0.0 0.909 |

22.1 ± 16.9 19.8 ± 19.5 -0.2 0.158 |

26.2 ± 19.7 24.4 ± 22 -0.1 0.165 |

20.4 ± 16.1 21.6 ± 24.9 0.1 0.893 |

25.4 ± 20.5 22.9 ± 21.6 -0.2 0.295 |

22.5 ± 12.6 26.2 ± 26.3 0.2 0.918 |

23.1 ± 15.1 19.4 ± 19 -0.3 0.193 |

28.4 ± 25.9 33 ± 27.1 0.3 0.929 |

| Communication At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

25.9 ± 27.1 18.2 ± 17.5 -0.3 0.278 |

7.6 ± 10.9 6.3 ± 9.9 -0.2 0.497 |

15.6 ± 22.4 12.4 ± 15 -0.2 0.399 |

15.9 ± 19.9 11.4 16.3 -0.3 0.344 |

15.9 ± 21.7 12.7 ± 15.8 -0.2 0.367 |

15 ± 25.4 10 ± 13.9 -0.5 0.380 |

14.7 ± 21.5 9.2 ± 11.8 -0.4 0.090 |

17.9 ± 22.3 18.4 ± 19.6 0.1 0.980 |

| Pain and discomfort At V0 At V6M Cohen´s d p value |

37.2 ± 26.6 27.9 ± 20.9 -0.6 0.070 |

48.3 ± 27.7 37.8 ± 18.2 -0.5 0.080 |

43.5 ± 27.2 34.8 ± 19.4 -0.5 0.076 |

43.2 ± 29.3 28.8 ± 21.5 -1.0 0.043 |

44.2 ± 26.9 33.3 ± 19.8 -0.6 0.019 |

40.8 ± 30.3 33.3 ± 21.1 -0.3 0.362 |

42.8 ± 22.8 32.5 ± 19.6 -0.7 0.016 |

44.8 ± 37 35.1 ± 21.2 -0.4 0.307 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).