Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

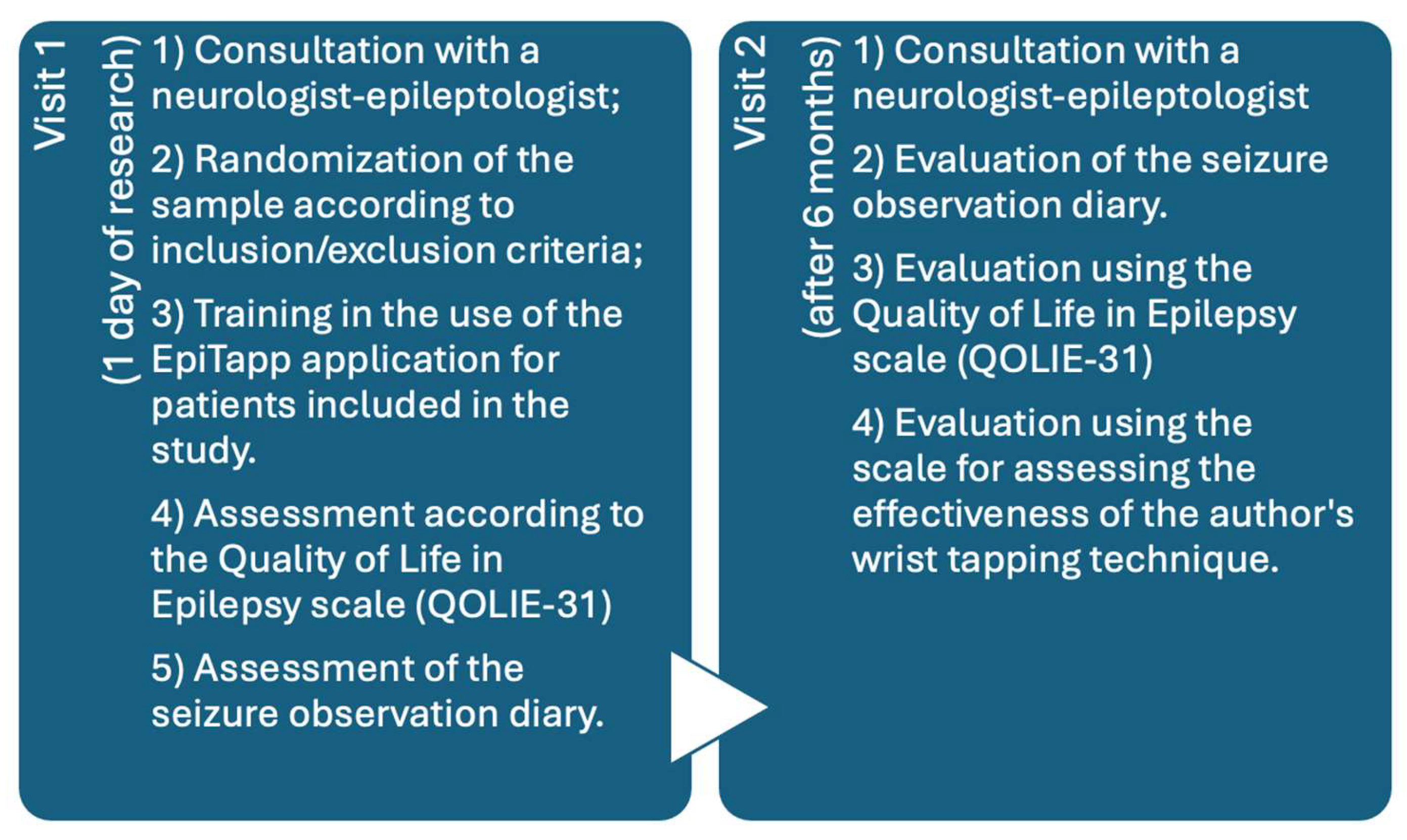

2. Materials and Methods

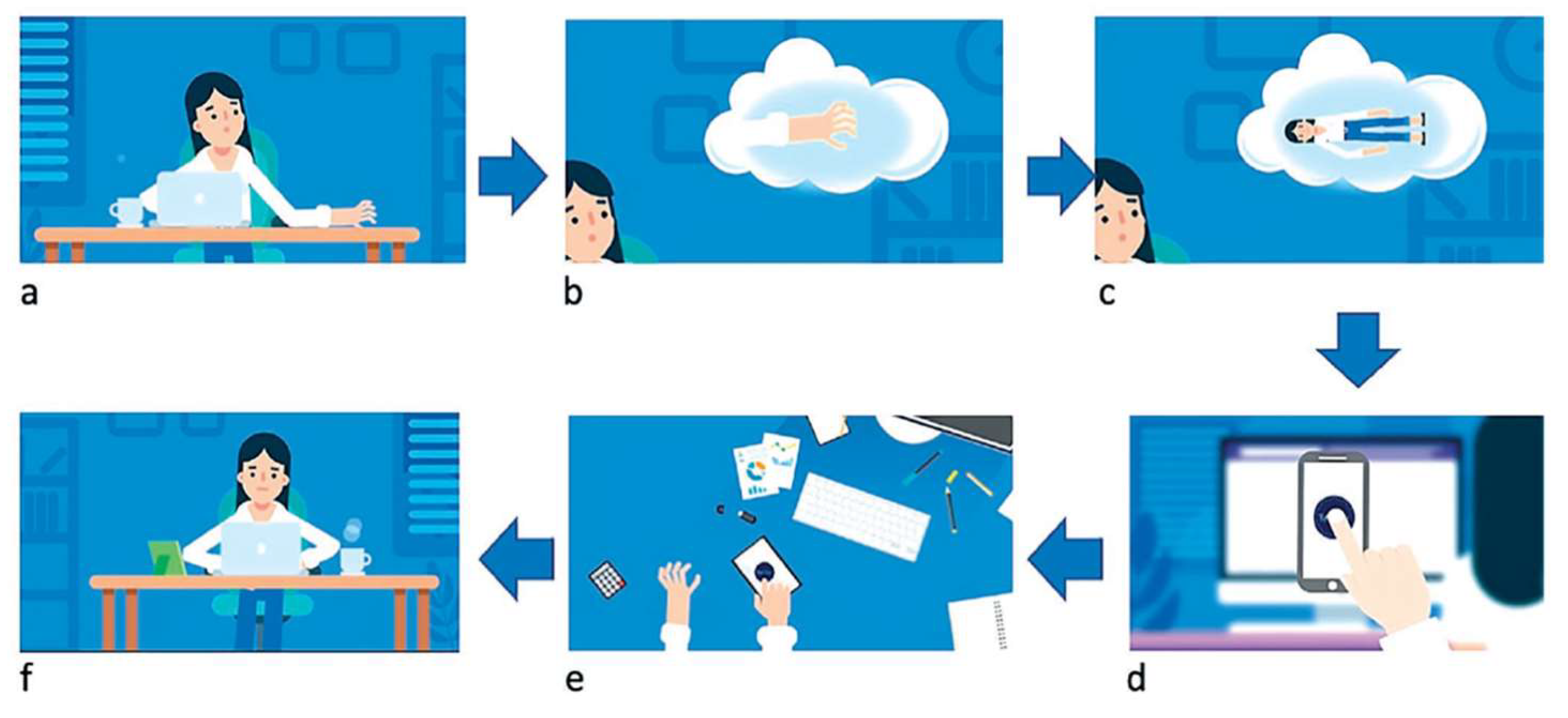

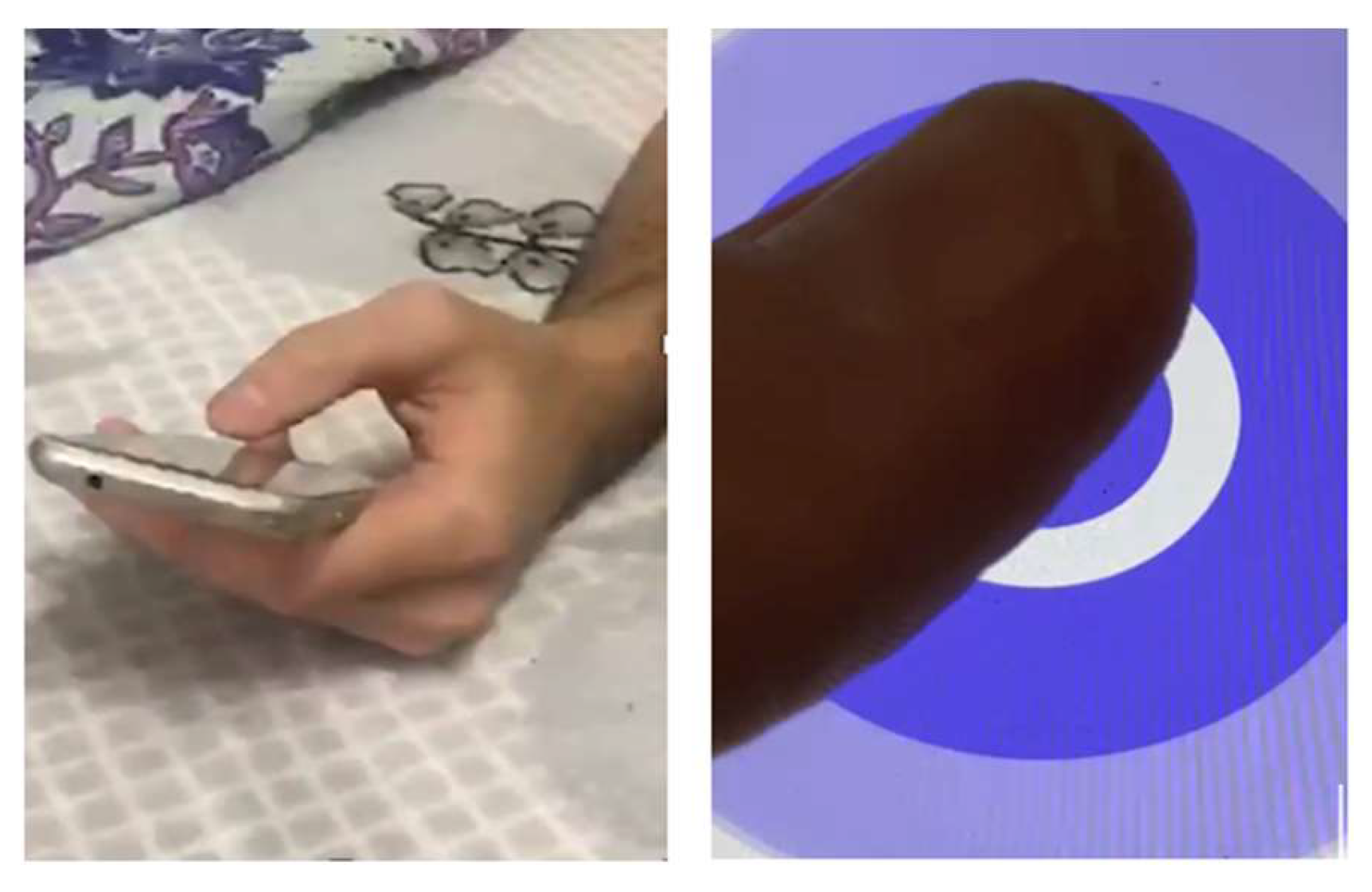

2.1. Description of the EpiTapp® Application Based on the Principle of Exogenous Rhythmic Stimulation.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Analysis of Seizure Diaries to Determine Monthly Frequency of Bilateral Tonic-Clonic Seizures in the Main and Control Groups.

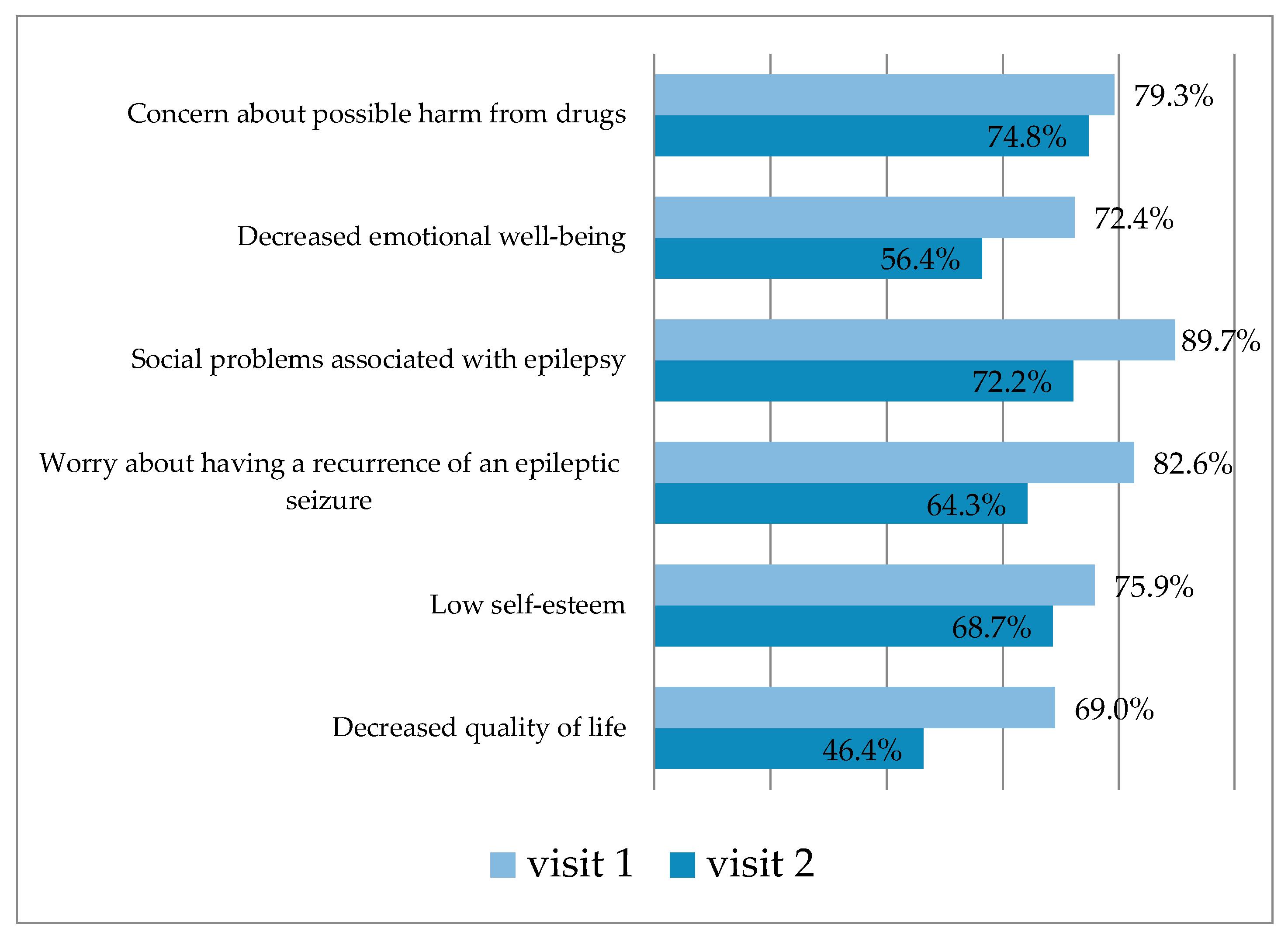

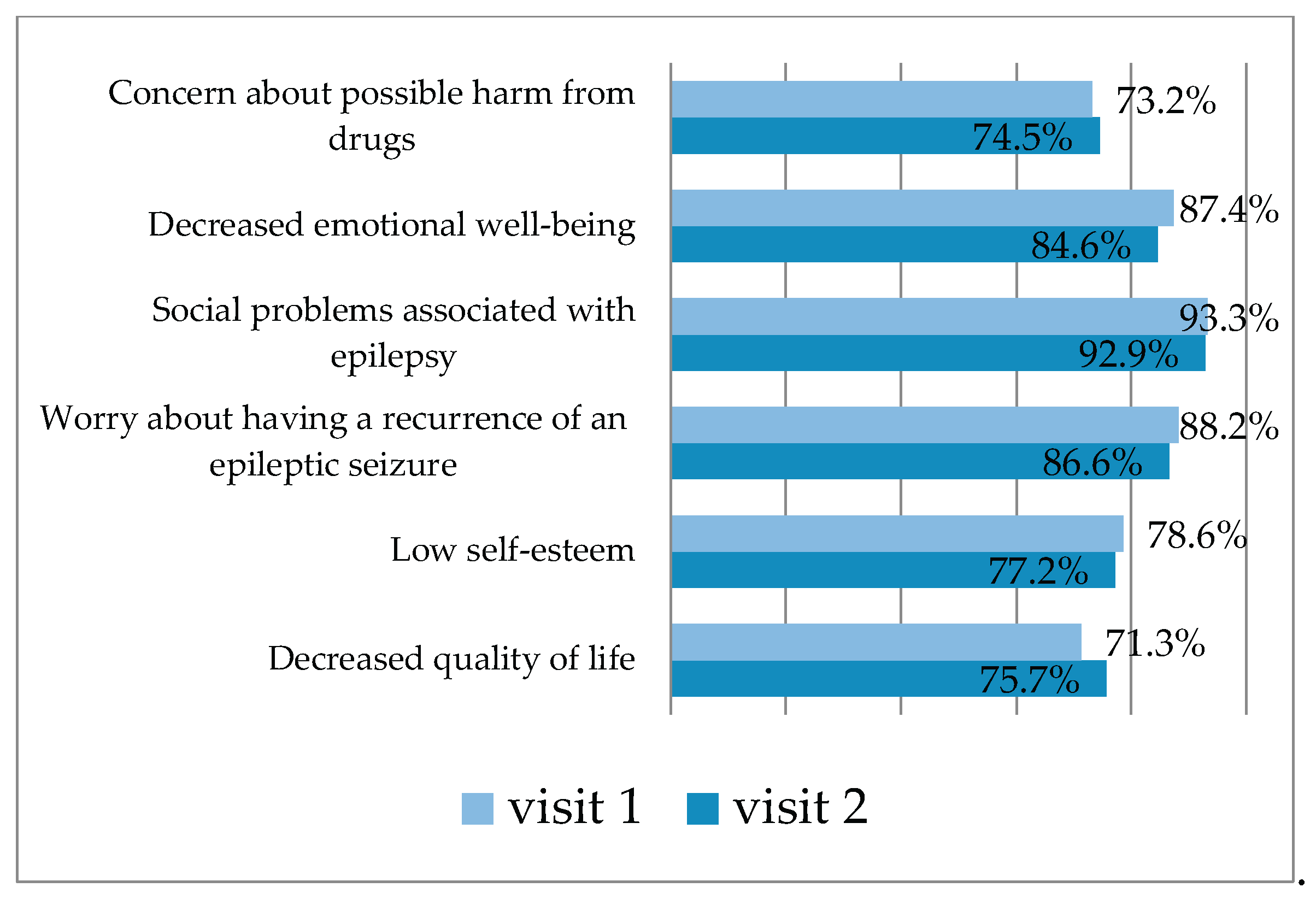

3.2. Quality of Life Outcomes in the Main and Control Groups over a 6-Month Observation Period

3.2.1. QOLIE-31 Questionnaire Results in the Main Group

3.2.2. QOLIE-31 Questionnaire Results in the Control Group

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SFE | Structural focal epilepsy |

| BTCS | Bilateral tonic-clonic seizures |

| QOLIE-31 | Quality of Life in Epilepsy- 31 |

| AEDs | Antiepileptic Drugs |

| HADS | The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| MMSE | The Mini-Mental State Examination |

| FAB | Fullerton Advanced Balance scale |

References

- Christensen, J.; Trabjerg, B.B.; Wagner, R.G.; Newton, C.R.; Kwon, C.S.; Aaberg, K.M.; …; Dreier, J.W. Prevalence of epilepsy: a population-based cohort study in Denmark with comparison to Global Burden of Disease (GBD) prevalence estimates. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2025, 96(5), 480–488.

- Massi, D.G.; Feudjio, R.; Eyoum, C.; Paternoster, L.; Magnerou, A.M.; Ferreira, N.T.; …; Mapoure, N.Y. Prevalence of depression in people with epilepsy: A hospital-based study in Cameroon. Epilepsy Behav. 2025, 165, 110326.

- Jiao, D.; Xu, L.; Gu, Z.; Yan, H.; Shen, D.; Gu, X. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of epilepsy: electromagnetic stimulation–mediated neuromodulation therapy and new technologies. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 20(4), 917–935. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, P.T.; Zeng, B.Y.; Hsu, C.W.; Liang, C.S.; Carvalho, A.F.; Brunoni, A.R.; …; Li, C.T. The non-invasive brain or nerve stimulation treatment did not increase seizure frequency in patients with epilepsy: A network meta-analysis. Epilepsy Behav. 2025, 164, 110290. [CrossRef]

- Narodova, E.A.; Shnayder, N.A.; Narodova, V.V.; Dmitrenko, D.V.; Artyukhov, I.P. The role of non-drug treatment methods in the management of epilepsy. Int. J. Biomedicine 2018, 8(1), 9–14. [CrossRef]

- Alipour, M.; Abdolmaleki, M.; Shabanpour, Y.; Zali, A.; Ashrafi, F.; Nohesara, S.; Hajipour-Verdom, B. Advances in magnetic field approaches for non-invasive targeting neuromodulation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1489940. [CrossRef]

- Karlov, V.A. The doctrine of the epileptic system. The merit of the domestic scientific school. Epilepsy Paroxysmal States 2017, 4(9), 76–85.

- Rahimi-Dehkordi, N.; Heidari-Soureshjani, S.; Rostamian, S. A systematic review of the anti-seizure and antiepileptic effects and mechanisms of piperine. CNS Agents Med. Chem. 2025, 25(2), 143–156. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Xie, J.; Li, Z.; He, X.; Wei, P.; Sander, J.W.; Zhao, G. The role of neuroinflammation and network anomalies in drug-resistant epilepsy. Neurosci. Bull. 2025, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Karlov, V.A. Evolution of L.R. Zenkov. L.R. Zenkov and epilepsy as a model for studying the functional organization of the central nervous system. Epilepsy Paroxysmal Cond. 2018, 10(3), 79–86.

- Baruah, T.; Hegde, S. Impact of Rhythmic Auditory Stimulation on Neurocognition: Proposed Mechanism of Action of Rhythmic Auditory Stimulation on Neurocognitive Abilities. Preprints 2025, 2025041965. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Jain, V.K. A review of the multidimensional impact of music: psychological, educational and therapeutic perspectives. A Pratibha Spandan’s Journal 2025, 13(1), 1–7.

- Mehta, R.K.; Zhu, Y.; Weston, E.B.; Marras, W.S. Development of a neural efficiency metric to assess human-exoskeleton adaptations. Front. Robot. AI 2025, 12, 1541963. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.G.; Li, C.W. The Neural Basis of Groove Sensations: Implications for Music-Based Interventions and Dance Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease., arXiv 2025:2503.02500.

- Halberg, F.; Chibisov, S.M.; Radysh, I.V. Time structures (chronomes) in us and around us. PFUR 2005, 186.

- Narodova, E.A.; Rudnev, V.A.; Shnayder, N.A.; Narodova, V.V.; Erahtin, E.E.; Dmitrenko, D.V.; Shilkina, O.S.; Moskaleva, P.V.; Gazenkampf, K.A. Parameters of the Wrist Tapping using a Modification of the Original Method (Method of exogenous rhythmic stimulation influence on an individual human rhythm). Int. J. Biomedicine 2018, 8(2), 155–158. [CrossRef]

- Narodova, E.A.; Shnayder, N.A.; Narodova, V.V.; Erahtin, E.E.; Shilkina, O.S.; Moskaleva, P.V. Influence of anxiety on wrist tapping parameters and individual perception of one minute in healthy adults and patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Russ. Open Med. J. 2018, 7(4), 415. [CrossRef]

- Narodova, E.A.; Shnayder, N.A.; Karnauhov, V.E.; Bogomolova, O.D.; Petrov, K.V.; Narodova, V.V. Effect of Wrist Tapping on Interhemispheric Coherence in Patients with Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy. Int. J. Biomedicine 2021, 11(1), 73–77. [CrossRef]

- Jamal, W.; Das, S.; Maharatna, K.; et al. Brain connectivity analysis from EEG signals using stable phase-synchronized states during face perception tasks. Physica A 2015, 434, 273–295. [CrossRef]

- Morozova, M.A.; Blagosklonova, N.K. Intrahemispheric EEG coherence depending on clinical manifestations of temporal epilepsy in children. Hum. Physiol. 2007, 33(4), 18–23. [CrossRef]

- Miroshnikov, A. B., Formenov, A. D. Effect of a fidget spinner on the "individual minute" during monotonous work on cardio-training equipment. Therapist 2019, 1, 33–36.

- Feng, X.; Piper, R.J.; Prentice, F.; Clayden, J.D.; Baldeweg, T. Functional brain connectivity in children with focal epilepsy: a systematic review of functional MRI studies. Seizure 2024, 113, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Marcantoni, I.; Piccolantonio, G.; Ghoushi, M.; Valenti, M.; Reversi, L.; Mariotti, F.; et al. Interhemispheric functional connectivity: an fMRI study in callosotomized patients. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1363098. [CrossRef]

- Ukhtomsky, A.A. Dominanta; Piter: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2002; p. 448.

- Trimble, M.R.; Hesdorffer, D.; Hećimović, H.; Osborne, N. Personalised music as a treatment for epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2024, 156, 109829. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Gong, Y.; Xu, C.; Chen, Z. The bidirectional role of music effect in epilepsy: Friend or foe? Epilepsia Open 2024, 9(6), 2112–2127. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, C.; Guo, J. The effect of Mozart’s K. 448 on epilepsy: A systematic literature review and supplementary research on music mechanism. Epilepsy Behav. 2025, 163, 110108.

- Walker, M.C. State-of-the-art gene therapy in epilepsy. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2025, 38(2), 128–134. [CrossRef]

- Doțen, N. Psychological interventions in the care of people diagnosed with epilepsy. Studia Univ. Mold. Științ. Educ. 2024, 175(5), 212–218.

- Cai, D.C.; Chen, C.Y.; Lo, T.Y. Foot reflexology: recent research trends and prospects. Healthcare 2022, 11(1), 9. [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, M.M.; Istasy, T.A.; Valiante, M. Music in epilepsy: Predicting the effects of the unpredictable. Epilepsy Behav. 2021, 122, 108164. [CrossRef]

- Coppola, G.; Toro, A.; Operto, F.F.; et al. Mozart’s music in children with drug-refractory epileptic encephalopathies. Epilepsy Behav. 2015, 50, 18–22. [CrossRef]

- Marzbani, H.; Marateb, H.R.; Mansourian, M. Neurofeedback: a comprehensive review on system design, methodology and clinical applications. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 7(2), 143–158. [CrossRef]

- Sesso, G.; Sicca, F. Safe and sound: Meta-analyzing the Mozart effect on epilepsy. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 131(7), 1610–1620. [CrossRef]

- Van Bree, S.; Sohoglu, E.; Davis, M.H.; et al. Sustained neural rhythms reveal endogenous oscillations supporting speech perception. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19(2), e3001142. [CrossRef]

- Niebrzydowska, A.; Grabowski, J.; Niebrzydowska, A. Medication-induced psychotic disorder. A review of selected drugs side effects. Psychiatr. Danub. 2022, 34(1), 11–18. [CrossRef]

- Shnayder, N.A.; Narodova, E.A.; Narodova, V.V.; et al. The role of nondrug treatment methods in the management of epilepsy. In Epilepsy: Advances in Diagnosis and Therapy; Al-Zwaini, I.J., Majeed Albadri, B.A.H., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/books/epilepsy-advances-in-diagnosis-and-therapy/the-role-of-nondrug-treatment-methods-in-the-management-of-epileps (accessed on 27 May 2025).

| Group parameters | Me [P25; P75] |

| Age of patients, years | 33,5 [30,0; 40,0] |

| Duration of epilepsy, years | 7,5 [6,0; 9,0] |

| Average age of epilepsy onset, years | 35 [29,0; 40,0] |

| Number of BTCS*, per month | 3 [2; 4] |

| Group parameters | Me [P25; P75] |

| Age of patients, years | 39,5 [31,0; 49,0] |

| Duration of epilepsy, years | 6 [5,0; 8,5] |

| Average age of epilepsy onset, years | 31,5 [27,0; 40,0] |

| Number of BTCS*, per month | 4 [2; 6] |

| Type of epileptic seizures | Me [P25; Р75] | *р |

|---|---|---|

| BTCS (visit 1) | 2 [2; 3] | 0,000003 |

| BTCS (visit 2) | 0 [0; 1] |

| Type of epileptic seizures | Me [P25; Р75] | *р |

|---|---|---|

| BTCS (visit 1) | 3 [2; 6] | 0,62 |

| BTCS (visit 2) | 3 [1; 6] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).