Submitted:

26 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Ice Cream Production

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Chemical Composition and Physicochemical Properties

2.3.2. Analysis of Ice Crystals

2.3.3. Statistical Processing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition and Physicochemical Parameters

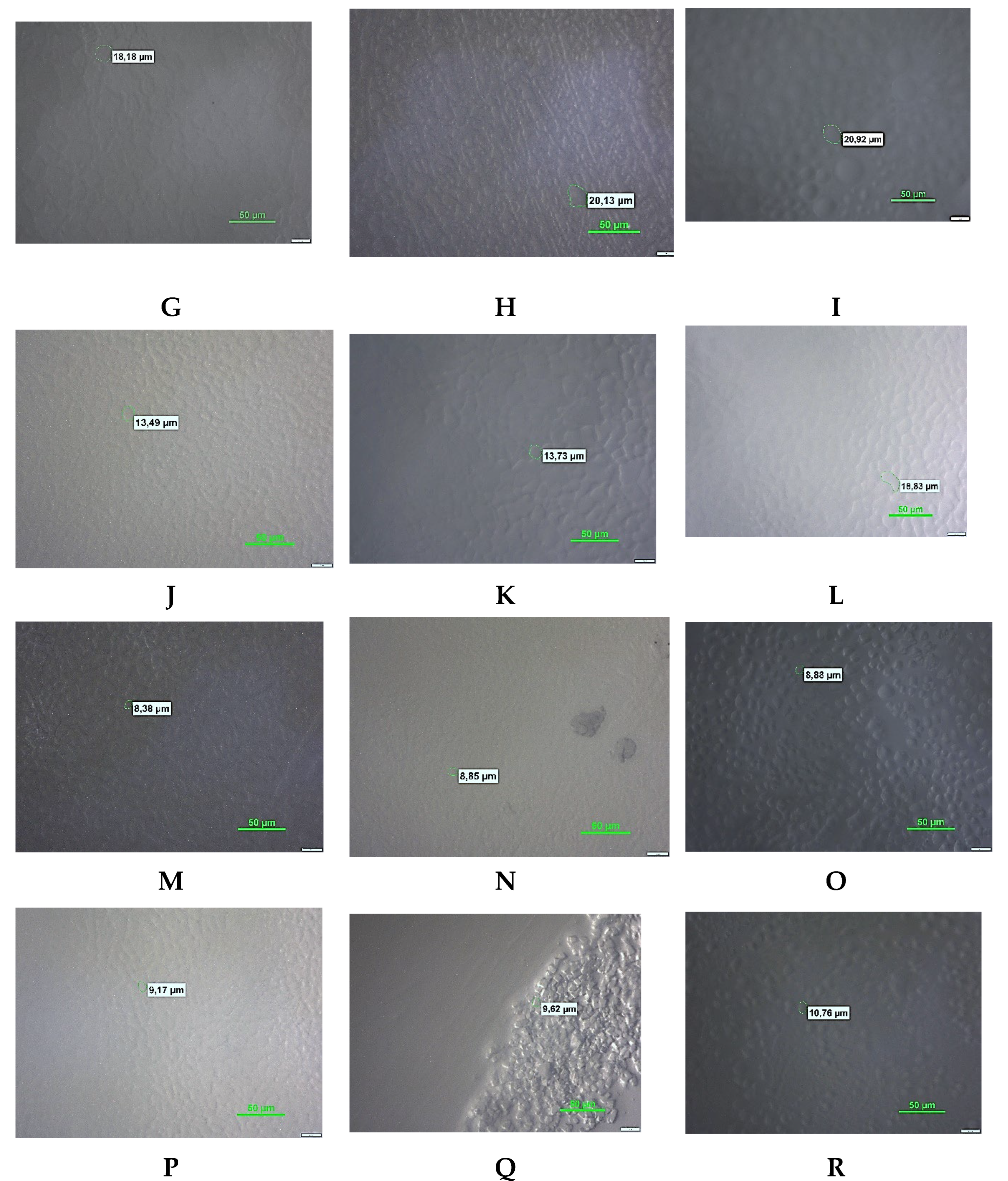

3.3. Microscopy Analysis

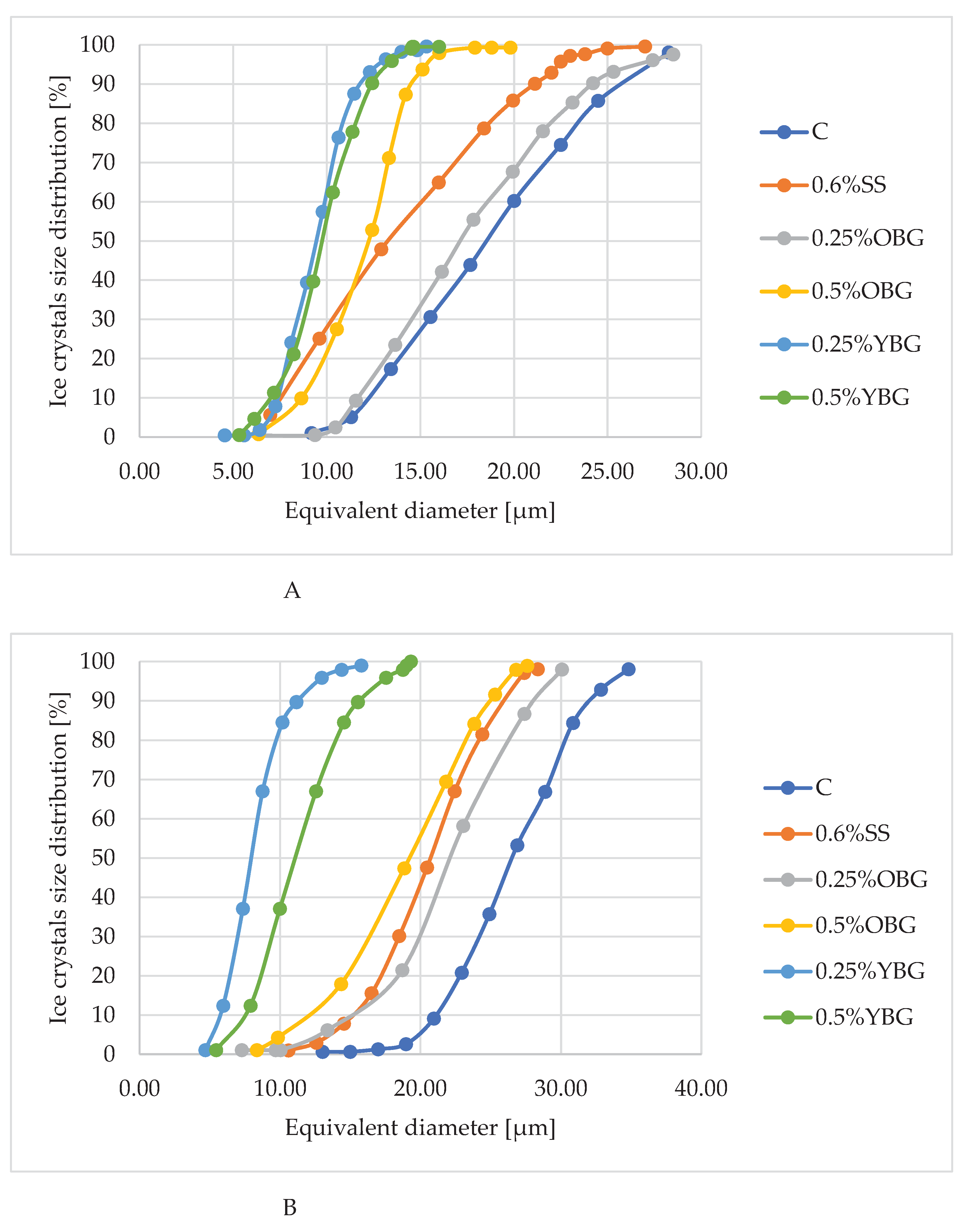

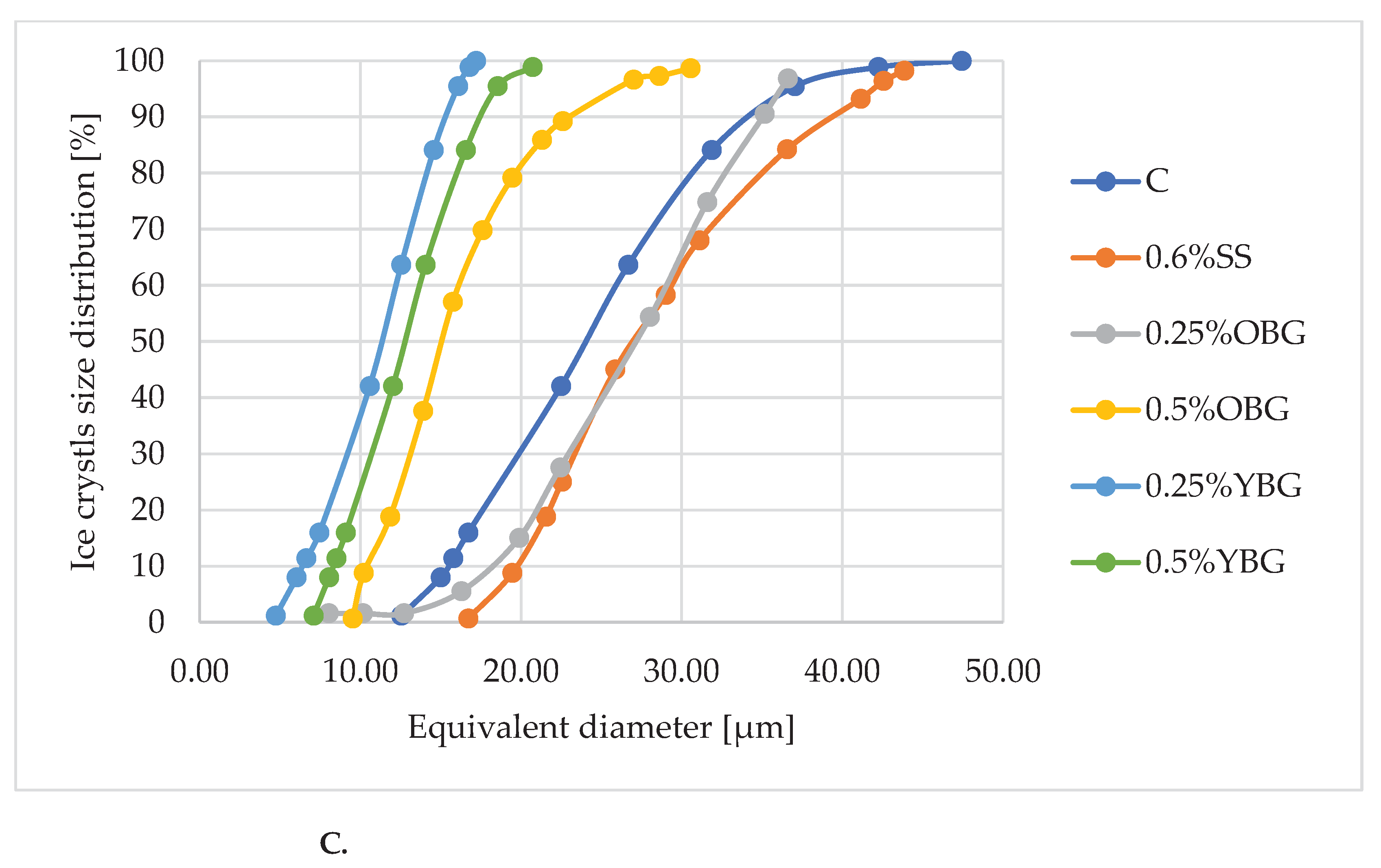

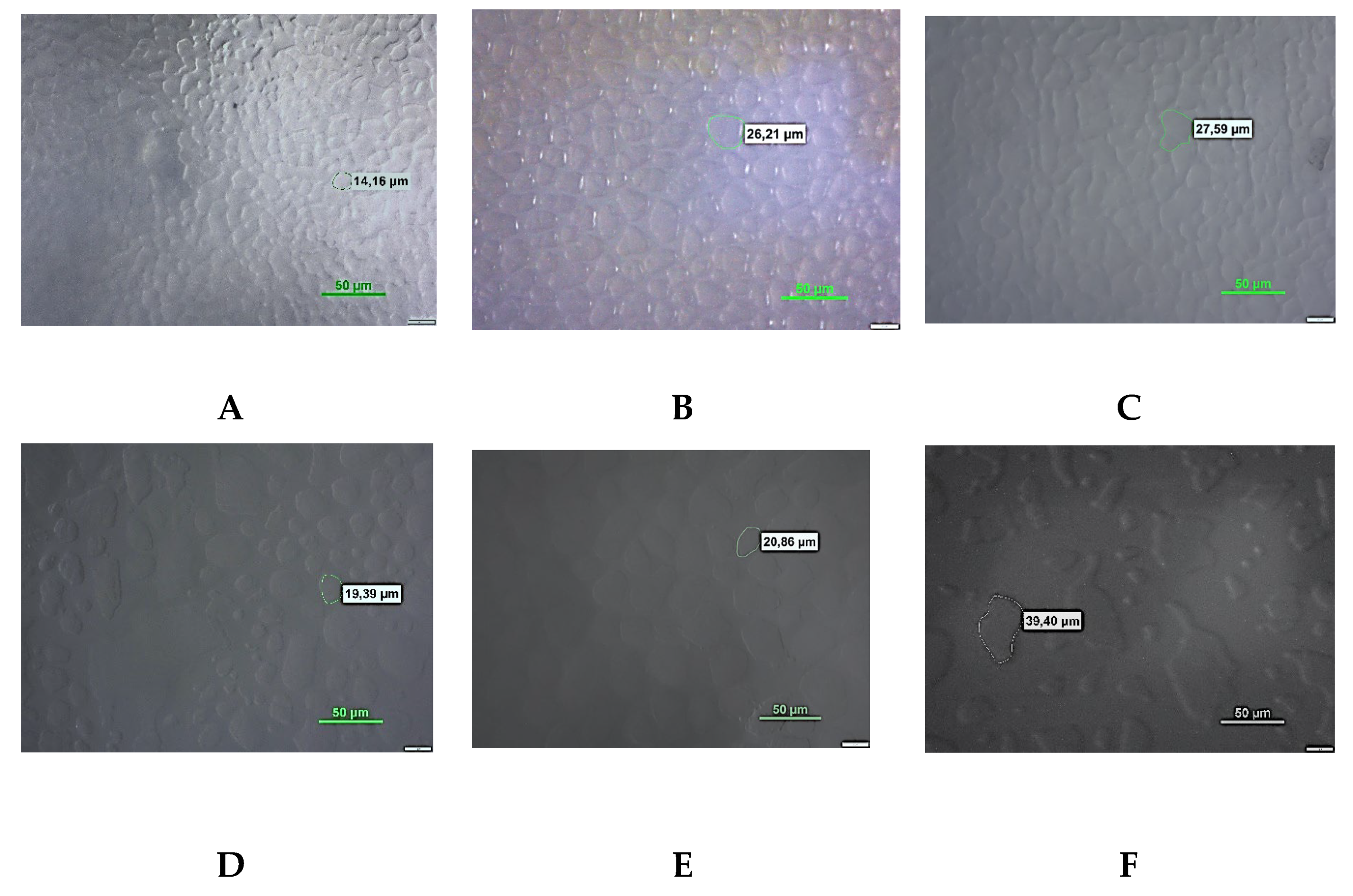

| Sample | Time of storage | Minimum diameter of ice crystals (μm) | Maximum diameter of ice crystals (μm) | Average value of ice crystal diameter (μm) |

| С | 24h | 9.18a±0.12 | 28.26a±0.70 | 18.50a±1.21 |

| 1W | 12.23b±0.03 | 35.37b±0.89 | 25.01b±1.06 | |

| 1M | 13.33c±0.14 | 37.39c±0.52 | 27.50c±0.78 | |

| 0,6%SS | 24h | 5.64a±0.22 | 30.32a±0.46 | 15.80a±0.67 |

| 1W | 10.60b±0.11 | 35.71b±0.35 | 20.50b±0.77 | |

| 1M | 16.72c±0.47 | 43.84c±0.60 | 32.15c±1.18 | |

| 0,25%OBG | 24h | 5.32a±0.12 | 28.31a±0.42 | 18.74a±0.04 |

| 1W | 7.27b±0.02 | 30.07b ±0.65 | 19.29b±0.50 | |

| 1M | 8.03c±0.05 | 36.60c±1.05 | 20.01b±0.72 | |

| 0,5%OBG | 24h | 6.35a±0.19 | 19.81a±0.28 | 11.38a±0.17 |

| 1W | 8.35b±0.16 | 27.59b±0.89 | 12.71b±0.16 | |

| 1M | 9.52c±0.12 | 30.55c±0.71 | 16.31c±0.15 | |

| 0,25%YBG | 24h | 4.54a±0.03 | 15.33a±0.41 | 8.49a±0.37 |

| 1W | 4.68b±0.02 | 16.51a±0.64 | 9.26b ± 0.12 | |

| 1M | 4.73b±0.04 | 17.19b±0.31 | 9.52b±0.16 | |

| 0,5%YBG | 24h | 5.32a±0.19 | 15.99a±0.50 | 10.24a ±0.02 |

| 1W | 5.45a±0.09 | 19.31b±0.98 | 10.52a±0.49 | |

| 1M | 7.08b±0.18 | 20.72c±0.52 | 11.08b±0.20 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Syed, Q. A.; Anwar, S.; Shukat, R.; Zahoor, T. Effects of different ingredients on texture of ice cream. J Nutr Health Food Eng. 2018, 8, 422–435. [CrossRef]

- Aliabbasi, N.; Emam-Djomeh, Z. Application of nanotechnology in dairy desserts and ice cream formulation with the emphasize on textural, rheological, antimicrobial, and sensory properties. eFood, 2024, 5, e170. [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, O.; Mykhalevych, A.; Polischuk, G.; Buniowska-Olejnik, M.; Bass, O.; Bandura, U. Technological functions of hydrolyzed whey concentrate in ice cream. Ukr. Food J. 2022, 11, 498–517. [CrossRef]

- Mykhalevych, A.; Buniowska-Olejnik, M.; Polishchuk, G.; Puchalski, C.; Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A.; Berthold-Pluta, A. The Influence of Whey Protein Isolate on the Quality Indicators of Acidophilic Ice Cream Based on Liquid Concentrates of Demineralized Whey. Foods 2024, 13, 170. [CrossRef]

- Markowska, J.; Tyfa, A.; Drabent, A.; Stępniak, A. The Physicochemical Properties and Melting Behavior of Ice Cream Fortified with Multimineral Preparation from Red Algae. Foods 2023, 12, 4481. [CrossRef]

- Sharqawy, M. H.; Goff, H. D. Effect of temperature variation on ice cream recrystallization during freezer defrost cycles. Journal of Food Engineering 2022, 335, 111188. [CrossRef]

- Lomolino, G., Zannoni, S., Zabara, A., Da Lio, M., & De Iseppi, A. Ice recrystallisation and melting in ice cream with different proteins levels and subjected to thermal fluctuation. International Dairy Journal 2020, 100, 104557. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, A.; Liu, L.; Kan, Z.; Wang, W. The relationship between water-holding capacities of soybean–whey mixed protein and ice crystal size for ice cream. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2021, 44, e13723. [CrossRef]

- Kot, A.; Jakubczyk, E.; Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A. The Effectiveness of Combination Stabilizers and Ultrasound Homogenization in Milk Ice Cream Production. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7561. [CrossRef]

- Yan, L., Yu, D., Liu, R., Jia, Y., Zhang, M., Wu, T., & Sui, W. Microstructure and meltdown properties of low-fat ice cream: Effects of microparticulated soy protein hydrolysate/xanthan gum (MSPH/XG) ratio and freezing time. Journal of Food Engineering 2021, 291, 110291. [CrossRef]

- Tvorogova, A. A.; Landikhovskaya, A. V.; Kazakova, N. V.; Zakirova, R. R.; Pivtsaeva, M. M. Scientific and practical aspects of trehalose contain in ice cream without sucrose. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 640, 052017. [CrossRef]

- Landikhovskaya, A. V.; Tvorogova, A. A.; Kazakova, N. V.; Gursky, I. A. The effect of trehalose on dispersion of ice crystals and consistency of low-fat ice cream. Food Processing: Techniques and Technology 2020, 50, 450–459. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wu, Y.; Song, Z.; Chen, X. A review of natural polysaccharides for food cryoprotection: Ice crystals inhibition and cryo-stabilization. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre 2022, 27, 100291. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Gao, Z., Huang, M., Fan, Q., Cui, L., Xie, P., Liu, L.; Guan, X.; Jin, J.; Jin, Q.; Wang, X. Static stability of partially crystalline emulsions stabilized by milk proteins: Effects of κ-carrageenan, λ-carrageenan, ι-carrageenan, and their blends. Food Hydrocolloids 2024, 147, 109387. [CrossRef]

- Míšková, Z.; Salek, R. N.; Křenková, B.; Kůrová, V.; Němečková, I.; Pachlová, V.; Buňka, F. The effect of κ-and ι-carrageenan concentrations on the viscoelastic and sensory properties of cream desserts during storage. LWT 2021, 145, 111539. [CrossRef]

- Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A.; Janczewska-Dupczyk, A.; Kot, A.; Łaba, S.; Samborska, K. The impact of ι-and κ-carrageenan addition on freezing process and ice crystals structure of strawberry sorbet frozen by various methods. Journal of food science 2020, 85, 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Mykhalevych, A.; Polishchuk, G.; Nassar, K.; Osmak, T.; Buniowska-Olejnik, M. β-Glucan as a Techno-Functional Ingredient in Dairy and Milk-Based Products—A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 6313. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N. Cereal β Glucan as a Functional Ingredient. In Innovations in Food Technology; Springer, Singapore, 2020; pp. 109–122. [CrossRef]

- Aljewicz, M.; Florczuk, A.; Dabrowska, A. Influence of β-glucan structures and contents on the functional properties of low-fat ice cream during storage. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2020, 70, 233–240. [CrossRef]

- Buniowska-Olejnik, M.; Mykhalevych, A.; Polishchuk, G.; Sapiga, V.; Znamirowska-Piotrowska, A.; Kot, A.; Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A. Study of Water Freezing in Low-Fat Milky Ice Cream with Oat β-Glucan and Its Influence on Quality Indicators. Molecules 2023, 28, 2924. [CrossRef]

- Shibani, F.; Asadollahi, S.; Eshaghi, M. The effect of beta-glucan as a fat substitute on the sensory and physico-chemical properties of low-fat ice cream. Journal of Food Safety and Processing 2021, 1, 71–84.

- Şengül, M.; Ufuk, S. Therapeutic and functional properties of beta-glucan, and its effects on health. Eurasian Journal of Food Science and Technology 2022, 6, 29–41.

- Tomczyńska-Mleko, M.; Mykhalevych, A.; Sapiga, V.; Polishchuk, G.; Terpiłowski, K.; Mleko, S.; Sołowiej, B.G.; Pérez-Huertas, S. Influence of Plant-Based Structuring Ingredients on Physicochemical Properties of Whey Ice Creams. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2465. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Guo, R., Zhan, T., Kou, Y., Ma, X., Song, H., Zhou, W.; Song, L.; Zhang, H.; Xie, F.; Yuan, C.; Song, Z.; Wu, Y. Retarding ice recrystallization by tamarind seed polysaccharide: Investigation in ice cream mixes and insights from molecular dynamics simulation. Food Hydrocolloids 2024, 149, 109579. [CrossRef]

- Mykhalevych, A.; Moiseyeva, L.; Polishchuk, G.; Bandura, U. Determining patterns of lactose hydrolysis in liquid concentrates of demineralized whey. Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies, 2024, 6, 24–32. [CrossRef]

- Teles F. F.; Young C. K.; Stull J. W. A method for rapid determination of lactose. Journal of Dairy Science 1978, 61, 506–508. [CrossRef]

- Muse, M.R.; Hartel, R.W. Ice cream structural elements that affect melting rate and hardness. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A.; Łaba, S.; Jakubczyk, E. The effects of selected stabilizers addition on physical properties and changes in crystal structure of whey ice cream. LWT 2022, 154, 112841. [CrossRef]

- Romulo, A.; Meindrawan, B. Effect of Dairy and Non-Dairy Ingredients on the Physical Characteristic of Ice Cream. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 794, 012145. [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods.

- Rout, P.; Saha, S. Rheology of ice cream: From fundamentals to applications. Innovations in Agriculture 2023, 6, 01–01.

- Goff, H. D. Ice cream. In Lipid Technologies and Applications; Routledge: New York, USA, 2018; pp. 329–355.

- Góral, M.; Kozłowicz, K.; Pankiewicz, U.; Góral, D.; Kluza, F.; Wójtowicz, A. Impact of stabilizers on the freezing process, and physicochemical and organoleptic properties of coconut milk-based ice cream. LWT 2018, 92, 516–522. [CrossRef]

- Fuangpaiboon, N.; Kijroongrojana, K. Sensorial and physical properties of coconut-milk ice cream modified with fat replacers. Maejo International Journal of Science and Technology 2017, 11, 133.

- Guleria, P.; Kumari, S.; Dangi, N. β-glucan: health benefits and role in food industry-a review. Int. J. Enhanc. Res. Sci. Technol. Eng 2015, 4, 3–7.

- Suchecka, D.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J.; Żyła, E.; Harasym, J. P.; Oczkowski, M. Selected physiological activities and health promoting properties of cereal beta-glucans. A review. Journal of Animal and Feed Sciences 2017, 26, 183–191. [CrossRef]

- Sammalisto, S., Mäkelä-Salmi, N., Wang, Y., Coda, R., & Katina, K. (2024). Potential of microbial and cereal β-glucans as hydrocolloids in gluten-free oat baking. Lwt, 191, 115678.

- Frank, J., Sundberg, B., Kamal-Eldin, A., Åman, P., & Vessby, B. (2004). Yeast-leavened oat breads with high or low molecular weight β-glucan do not differ in their effects on blood concentrations of lipids, insulin, or glucose in humans. The Journal of nutrition, 134(6), 1384-1388.

- Das, N.; Hooda, A. Chemistry and Different Aspects of Ice Cream. In The Chemistry of Milk and Milk Products; Apple Academic Press: New York, USA, 2023; pp. 65–86.

- Raikos, V.; Grant, S. B.; Hayes, H.; Ranawana, V. Use of β-glucan from spent brewer's yeast as a thickener in skimmed yogurt: Physicochemical, textural, and structural properties related to sensory perception. Journal of dairy science 2018, 101, 5821–5831. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Saeedabadian, A. Influences of lactose hydrolysis of milk and sugar reduction on some physical properties of ice cream. J Food Sci Technol 2015, 52, 367–374. [CrossRef]

- Skryplonek, K.; Gomes, D.; Viegas, J.; Pereira, C.; Henriques, M. Lactose-free frozen yogurt: Production and characteristics. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Technologia Alimentaria 2017, 16, 171–179. [CrossRef]

- Dutra Rosolen, M.; Gennari, A.; Volpato, G.; Volken de Souza, C. F. Lactose Hydrolysis in Milk and Dairy Whey Using Microbial β-Galactosidases. Enzyme Res. 2015, 2015, 806240. [CrossRef]

- Majore, K.; Ciprovica, I. Sensory Assessment of Bi-Enzymatic-Treated Glucose-Galactose Syrup. Fermentation 2023, 9, 136. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T. The hydration of glucose: the local configurations in sugar–water hydrogen bonds. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008,10, 96–105. [CrossRef]

- Khaliduzzaman; Siddiqui, A. A.; Islam, M. M.; Easdani, M.; Bhuiyan, M. H. R. Effect of Honey on Freezing Point and Acceptability of Ice Cream. Bangladesh Res. Pub. J. 2012, 7, 355–360.

- Karp, S.; Wyrwisz, J.; Kurek, M. A. Comparative analysis of the physical properties of o/w emulsions stabilised by cereal β-glucan and other stabilisers. International journal of biological macromolecules 2019, 132, 236–243. [CrossRef]

- Sapiga, V.; Polischuk, G.; Buniowska, M.; Shevchenko, I.; Osmak, T. Polyfunctional Properties of Oat β-Glucan in the Composition of Milk-Vegetable Ice Cream. Ukr. Food J. 2021, 10, 691–702. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Haleem, A.M.; Awad, R.A. Some quality attributes of low fat ice cream substituted with hulless barley flour and barley ß-glucan. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 6425–6434. [CrossRef]

- Mejri, W.; Bornaz, S.; Sahli, A. Formulation of non-fat yogurt with β-glucan from spen brewer’s yeast. J. Hyg. Eng. Des. 2014, 8, 163–173.

- Khorshidian, N.; Yousefi, M.; Shadnoush, M.; Mortazavian, A. M. An overview of β-glucan functionality in dairy products. Current Nutrition & Food Science 2018, 14, 280–292.

- Zhang, H., Xiong, Y., Bakry, A. M., Xiong, S., Yin, T., Zhang, B., Huang, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Q. Effect of yeast β-glucan on gel properties, spatial structure and sensory characteristics of silver carp surimi. Food Hydrocolloids 2019, 88, 256–264. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, K. P.; Rasco, B. A.; Juming, T.; Sablani, S. S. State/Phase Transitions, Ice Recrystallization, and Quality Changes in Frozen Foods Subjected to Temperature Fluctuations. Food Engineering Reviews 2020, 12, 421–451.

- 52. Demir, Ş.; Arslan, S. The effects of select stabilizers addition on physicochemical, textural, microstructural and sensory properties of ice cream. Food Measure 2023, 17, 1119–1131. [CrossRef]

- Bahramparvar, M.; Tehrani, M. M. Application and Functions of Stabilizers in Ice Cream. Food Reviews International 2011, 27, 389–407.

- Ndoye, F. T.; Alvarez, G. Characterization of ice recrystallization in ice cream during storage using the focused beam reflectance measurement. Journal of food engineering 2015, 148, 24–34. [CrossRef]

- Gamel, T. H.; Badali, K.; Tosh, S. M. Changes of β-glucan physicochemical characteristics in frozen and freeze dried oat bran bread and porridge. Journal of Cereal Science 2013, 58, 104–109.

- Ames, N.; Storsley, J.; Tosh, S. Effects of processing on physicochemical properties and efficacy of β-glucan from oat and barley. Cereal Foods World 2015, 60, 4–8. [CrossRef]

- Ames, N.; Tosh, S. Validating the health benefits of barley foods: Effect of processing on physiological properties of beta-glucan in test foods. Proceedings of the 2011 AACCI Annual Meeting Abstracts, Cereal Foods World (Supplement Online), Palm Springs, CA, USA, 16–19 October 2011; A28.

- Lan-Pidhainy, X.; Brummer, Y.; Tosh, S.M.; Wolever, T.M.; Wood, P.J. Reducing beta-glucan solubility in oat bran muffins by freeze-thaw treatment attenuates its hypoglycemic effect. Cereal Chem. 2007, 84, 512–517. [CrossRef]

- Andrzej, K. M.; Małgorzata, M.; Sabina, K.; Horbańczuk, O. K.; Rodak, E. Application of rich in β-glucan flours and preparations in bread baked from frozen dough. Food Science and Technology International 2020, 26, 53-64. [CrossRef]

- Thammakiti, S.; Suphantharika, M.; Phaesuwan, T.; Verduyn, C. Preparation of spent brewer’s yeast β-glucans for potential applications in the food industry. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 39, 21–29. [CrossRef]

| Ingredients, % | Labeling of ice cream samples | |||||

| C | 0.6%SS | 0.25%OBG | 0.5%OBG | 0.25%YBG | 0.5%YBG | |

| Liquid hydrolyzed concentrate of demineralized whey | 75.0 | 75.0 | 75.0 | 75.0 | 75.0 | 75.0 |

| White sugar | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 |

| Whey protein isolate | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Stabilization system | – | 0.6 | – | – | – | – |

| β-glucan from oats | – | – | 0.25 | 0.5 | – | – |

| β-glucan from yeast | – | – | – | – | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Activated starter | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Vanillin | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Water | 9.9 | 9.3 | 9.65 | 9.4 | 9.65 | 9.4 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Sample | Solids, % | Protein, % | Fat, % | Сarbohydrates, % | Lactose, % | Monosaccharides, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 42.05a±0.91 | 6.05a±0.05 | 0.32a±0.01 | 33.08a±0.95 | 0.73a±0.05 | 32,35a±0.09 |

| 0.6%SS | 42.61a±1.02 | 6.01a±0.02 | 0.73e±0.02 | 33.05a±1.24 | 0.75a±0.02 | 32,30a±0.11 |

| 0.25%OBG | 42.28a±0.67 | 6.09a±0.06 | 0.37c±0.01 | 33.11a±1.00 | 0.72a±0.05 | 32,39a±0.05 |

| 0.5%OBG | 42.50a±0.95 | 6.03a±0.01 | 0.40d±0.02 | 33.12a±0.98 | 0.75a±0.03 | 32,37a±0.32 |

| 0.25%YBG | 42.33a±1.12 | 5.98a±0.05 | 0.35b±0.01 | 33.14a±1.05 | 0.78b±0.01 | 32,36a±0.10 |

| 0.5%YBG | 42.24a±1.04 | 6.01a±0.03 | 0.39d±0.01 | 33.09a±1.32 | 0.76a±0.06 | 32,33a±0.13 |

| Sample | Freezing point, °C | Overrun, % | Resistance to melting, min | ||

| 24h | 1T | 1M | |||

| C | –4.222b ± 0.14 | 69.08a±2.55 | 24.01ab±1.15 | 24.32a±0.64 | 24.58a±0.23 |

| 0.6%SS | –4.688b ± 0.03 | 75.25b±1.82 | 25.42b±0.57 | 26.12b±0.44 | 27.03b±0.80 |

| 0.25%OBG | –5.108c ± 0.25 | 81.52d±3.24 | 27.95c±0.46 | 28.53c±0.97 | 29.96c±1.09 |

| 0.5%OBG | –6.040d ± 0.18 | 83.12d±2.61 | 29.12d±0.84 | 29.87c±0.65 | 31.05d±1.37 |

| 0.25%YBG | –3.888a ± 0.07 | 77.39b±2.48 | 24.26a±0.53 | 24.58a±0.38 | 25.61a±0.94 |

| 0.5%YBG | –3.846a ± 0.02a | 76.74b±2.04 | 25.81ab±1.20 | 26.07b±0.31 | 26.50b±0.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).