1. Introduction

Complex networks shape every aspect of human life, driving critical systems such as technological infrastructures, information systems, and biological processes [

5]. Their fundamental role makes it crucial to understand their vulnerability to targeted attacks. Disrupting these networks can have far-reaching effects, triggering phenomena such as epidemic outbreaks, infrastructure failures, financial crises, and misinformation propagation [

6,

7].

A targeted attack on a network—known as network dismantling—aims to disrupt its structural integrity and functional capacity by identifying and removing a minimal set of critical nodes that fragment it into isolated sub-components [

6]. Designing effective dismantling strategies is essential, as they provide insights for improving the robustness of these critical networks.

Efficient network dismantling is challenging because identifying the minimal set of nodes for optimal disruption is an NP-hard problem—no known algorithm can solve it efficiently for large networks [

6]. This difficulty arises not only from the prohibitively large solution space but also from the structural complexity of real-world networks, which exhibit heterogeneous, fat-tailed connectivity [

8,

9,

10,

11] and intricate organizations such as modular and community structures [

12,

13], hierarchies [

14,

15], higher-order structures [

16,

17], and a latent geometry [

1,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

Node Betweenness Centrality (NBC) is a network centrality measure [

24] that quantifies the importance of a node in terms of the fraction of the shortest paths that pass through it. NBC-based attack, where nodes are removed in order of their betweenness centrality, is considered one of, if not the best, method for network dismantling [

25,

26,

27,

28]. However, like many other dismantling techniques, it requires global knowledge of the entire network topology, and its high computational cost limits its scalability to large networks. These limitations are shared by many other state-of-the-art dismantling methods, which additionally rely on black-box machine learning models, and are rarely validated across large, diverse sets of real-world networks (see

Table 1,

Table A3, and

Table A2).

Latent geometry has been recognized as a key principle for understanding the structure and complexity of real-world networks [

18,

19,

20,

21,

23,

29,

30]. It explains essential features such as small-worldness, degree heterogeneity, clustering, and navigability [

18,

19,

21], and drives critical processes like efficient information flow [

20,

29,

30,

31].

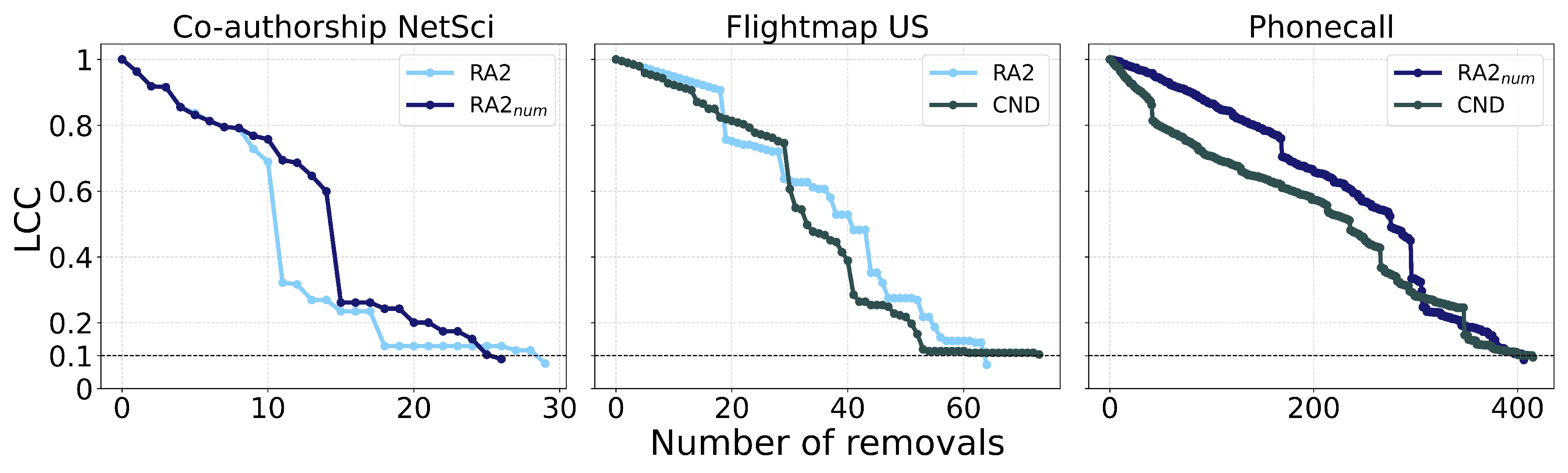

Recent work by Muscoloni et al. (2017) [

1] revealed that betweenness centrality is a global latent geometry estimator: it approximates node distances in an underlying geometric space. They also introduced Repulsion-Attraction network automata rule 2 (RA2), a local latent geometry estimator that uses only first-neighbor connectivity. RA2 performed comparably to NBC in tasks such as network embedding and community detection, despite relying solely on local information.

This raises the first question: can latent geometry—whether estimated globally or locally—guide effective network dismantling? If complex systems run on a latent manifold, estimating it may offer a more efficient way to disrupt connectivity.

The second question concerns efficiency: both NBC and RA2 have complexity, where N is the number of nodes and m the number of links in a network. However, RA2 is significantly faster in practice due to its use of local information and avoidance of the large running time associated with NBC’s computational overhead. This motivates exploring whether local latent geometry estimators can match the dismantling performance of global methods like NBC while offering a greater advantage in practical running time execution.

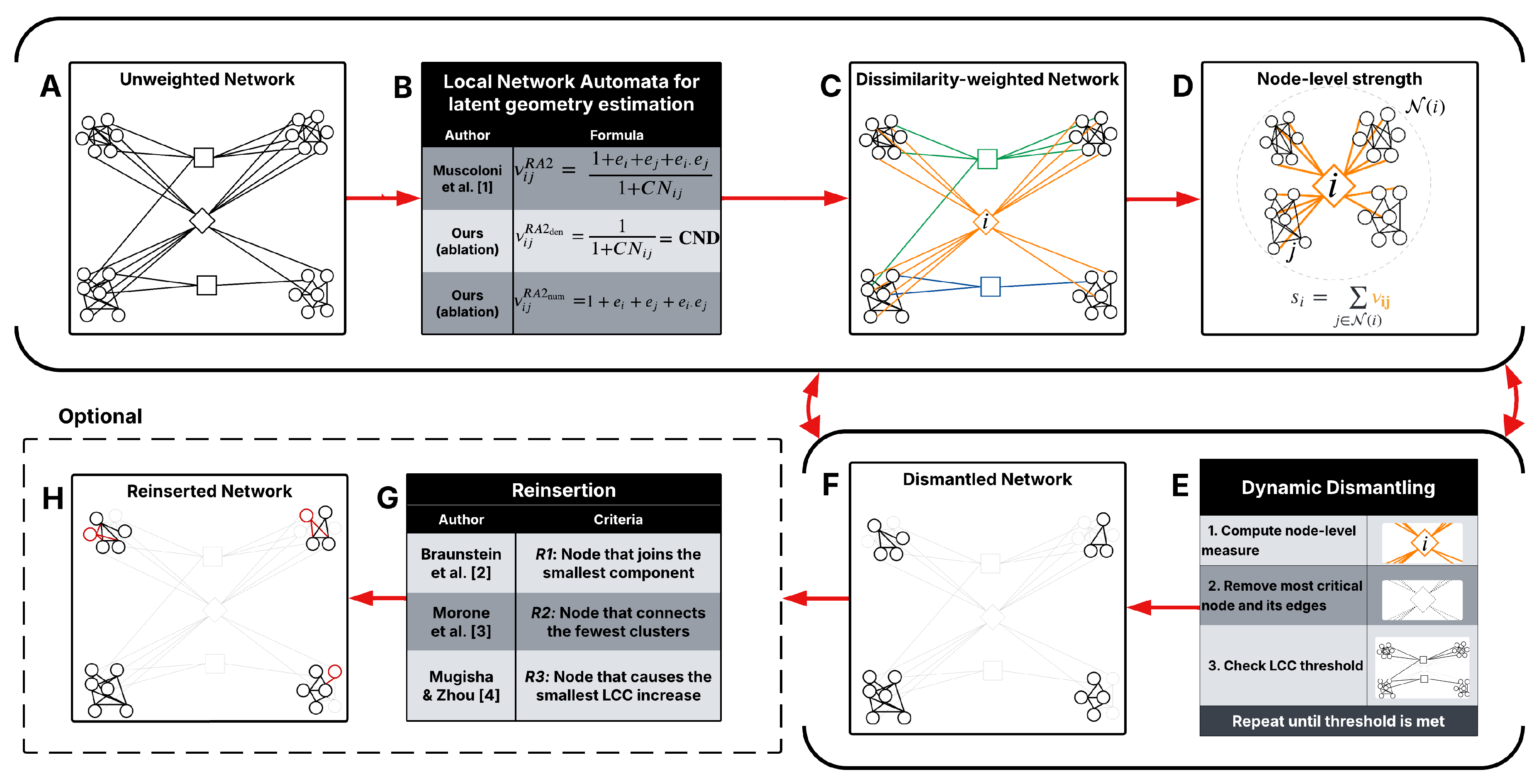

Motivated by these questions, we introduce the Latent Geometry-Driven Network Automata (LGD-NA) framework, which uses local topology estimators of latent geometry to drive the dismantling process. It achieves state-of-the-art dismantling performance on 1,475 real-world networks across 32 complex systems domains and its GPU implementation enables dismantling at large scales. Our contributions are as follows:

1. Latent Geometry-Driven (LGD) dismantling. Global LGD dismantling, such as NBC and local ones, such as RA2-based methods, estimate effective node distances on the manifold associated with the network in the latent space, capturing its geometry and exposing structural information critical for dismantling.

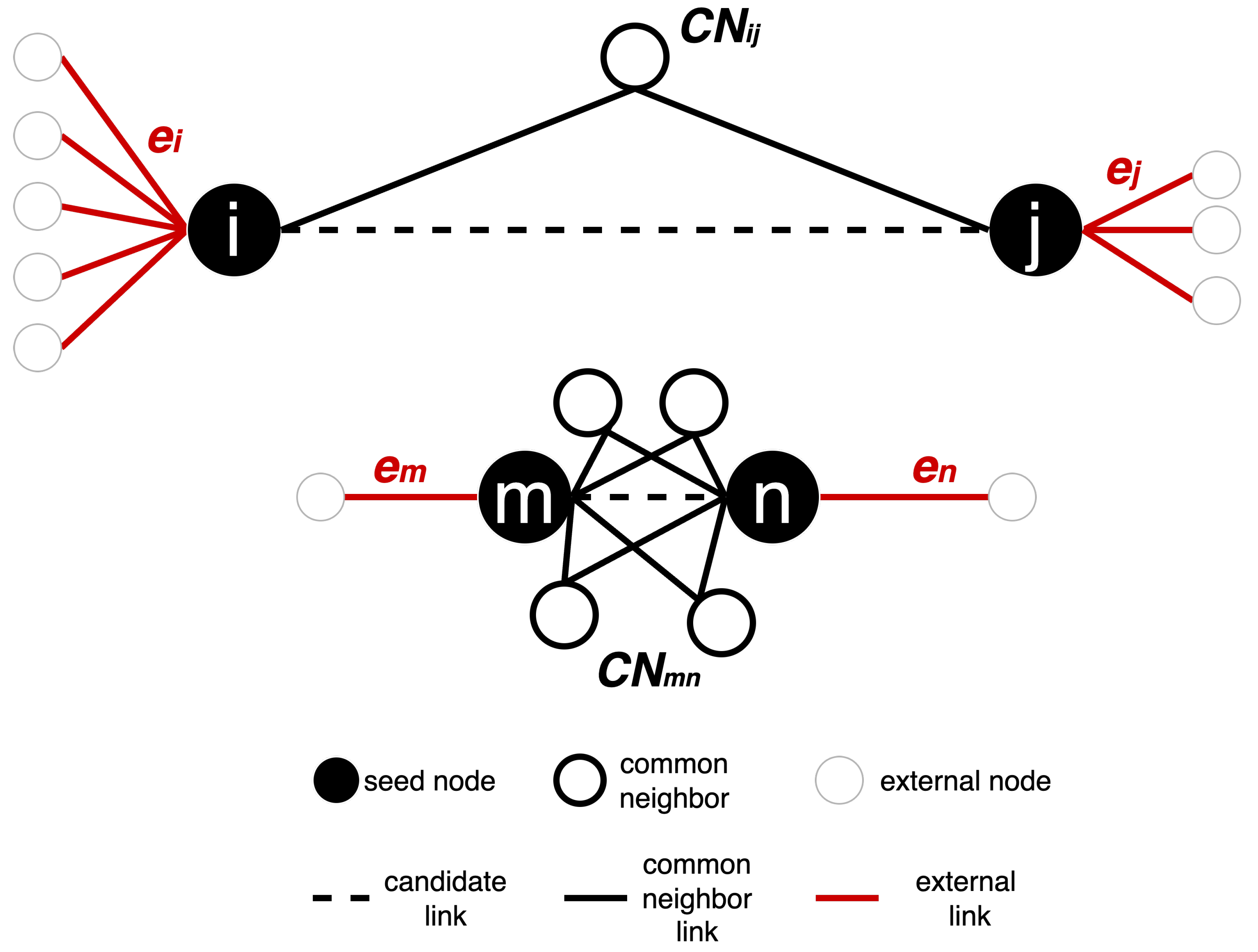

2. LGD Network Automata (LGD-NA). Network automata rules adopt local topology information to approximate the latent geometry distances of pairs of linked nodes in the network. The sum of the distances that a node has from its linked neighbors represents an estimation of how central a node is in the network topology. The higher this sum, the more a node dominates numerous and far-apart regions of the network, being a critical candidate for network dismantling. We show that LGD-NA consistently outperforms all other existing dismantling algorithms, including machine learning methods such as graph neural networks.

3. A simple common neighbors-based network automaton rule is highly effective. We discover that a variant of RA2, based solely on common neighbors, outperforms all other dismantling algorithms and achieves performance close to the state-of-the-art method, NBC. We refer to this variant as the common neighbor dissimilarity (CND): a minimalistic network automaton rule that acts as a local latent geometry estimator.

4. Comprehensive experimental validation. We build an ATLAS of 1,475 real-world networks across 32 complex systems domains, which is the largest and most diverse collection of real-world networks to date. We evaluate LGD-NA on this ATLAS, comparing with state-of-the-art methods, proving the effectiveness of LGD-NA in a wide variety of real-world settings

5. GPU-acceleration. We implement GPU acceleration for LGD-NA, enabling remarkable running time advantages in dismantling on networks significantly larger than those manageable by the state-of-the-art method, NBC.

4. Experiments

4.1. Evaluation Procedure

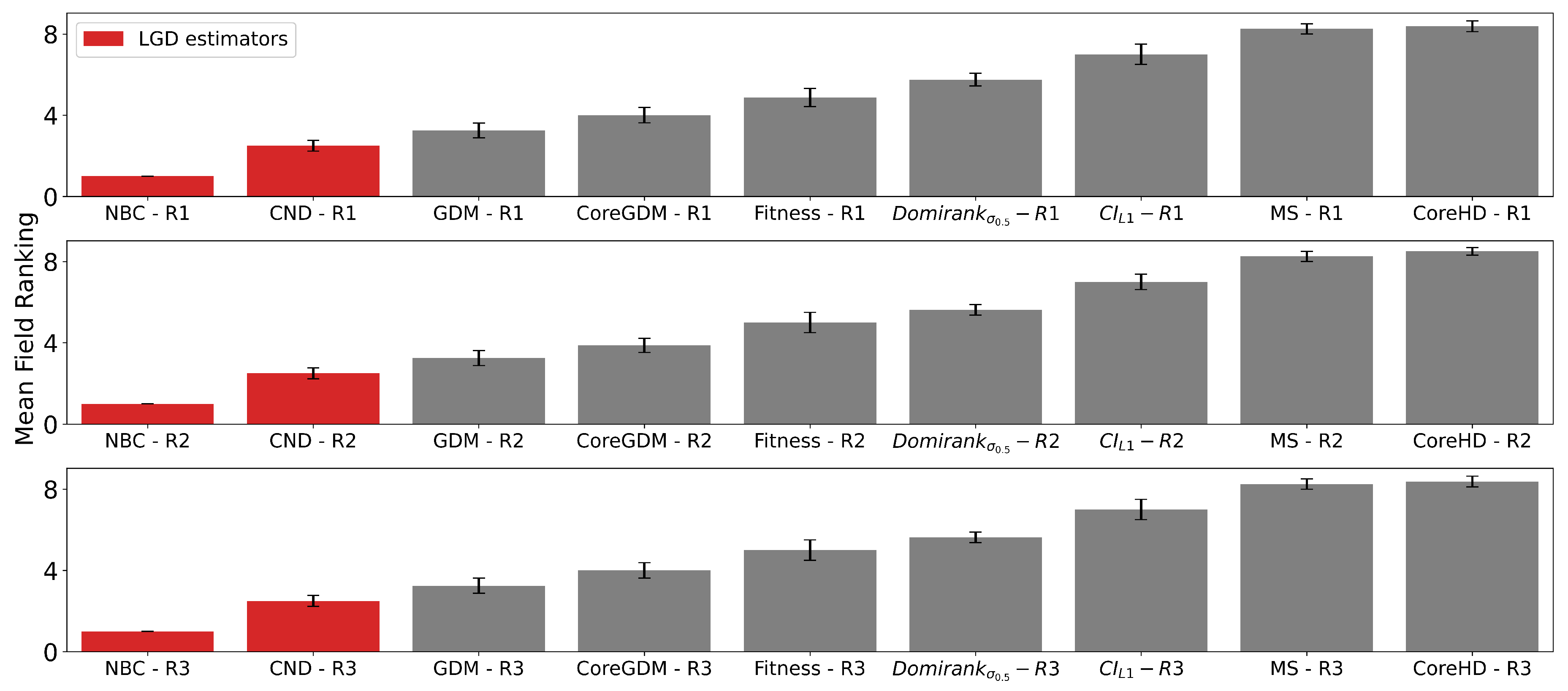

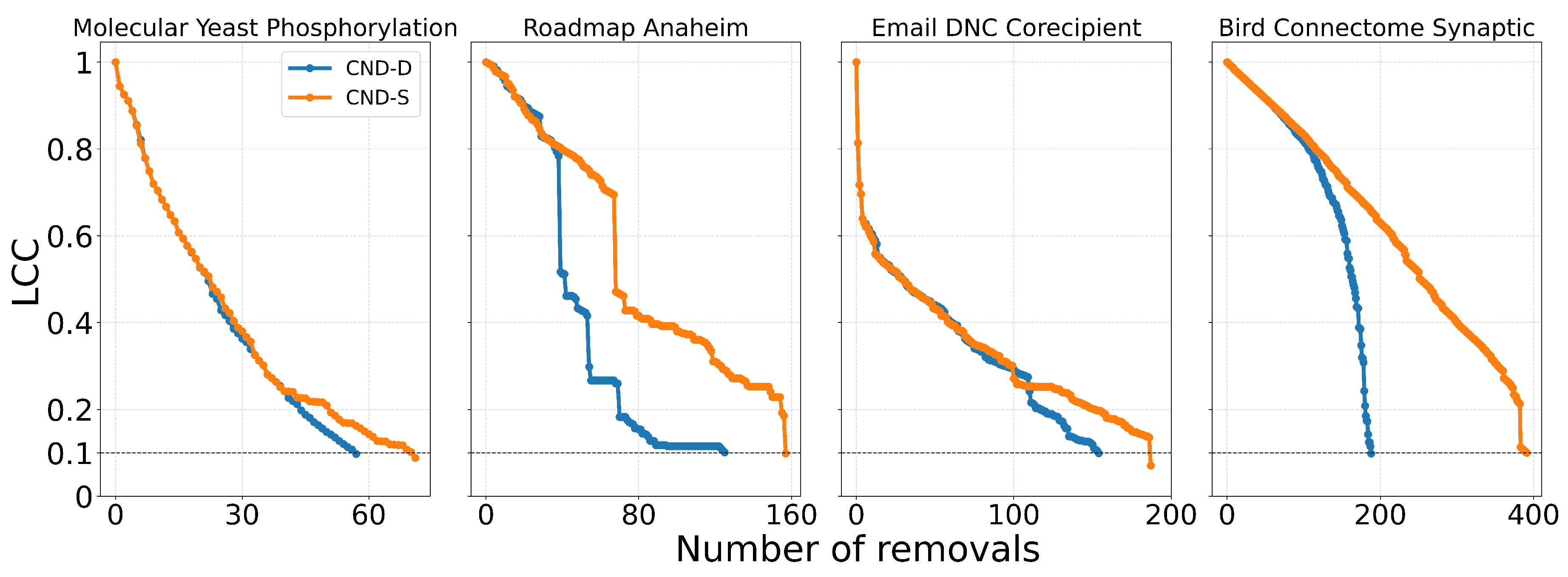

We evaluate all dismantling methods using a widely accepted procedure in the field of network dismantling [

6]. For each method, nodes are removed sequentially according to the order it defines. After each removal, we track the normalized size of the Largest Connected Component (LCC), defined as the ratio

, where

is the total number of nodes in the original network and

is the number of nodes in the largest component after

x removals. This process continues until the LCC falls below a predefined threshold. A commonly accepted threshold in dismantling studies is 10% of the original network size [

6]. To quantify dismantling effectiveness, we compute the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the LCC trajectory throughout the removal process, which records the normalized LCC size at each step. A lower AUC indicates a more efficient dismantling, as it reflects an earlier and sharper disruption of network connectivity. The AUC is computed using Simpson’s rule. See

Figure A2,

Figure A4,

Figure A7, and

Figure A8 for visual illustrations of the LCC curve.

4.2. Optional Reinsertion Step

After reaching the dismantling threshold, we optionally perform a reinsertion step to lower the dismantling cost by reintroducing nodes removed but were ultimately unnecessary. We test three reinsertion techniques introduced by previous dismantling studies: Braunstein et al. (2016) [

2] chooses the node ending up in the smallest component; Morone et al. (2016) [

3] selects the node connecting the fewest components; Mugisha and Zhou (2016) [

4] prioritizes nodes causing the smallest LCC increase. Reinsertion can significantly improve dismantling performance; recent work shows that simple heuristics with reinsertion can match or outperform complex algorithms that include reinsertion by default [

45]. As a result, we enforce two constraints to ensure the reinsertion step does not override the original dismantling method: (1) reinsertion cannot reinsert all nodes to recompute a new dismantling order, and (2) reinsertion must use the reverse dismantling order as a tiebreak. If a method includes reinsertion by default, we also evaluate its performance without reinsertion for a fair comparison. See

Table A4 for a full comparison of reinsertion methods.

4.3. ATLAS Dataset

Our fourth contribution is the breadth and diversity of real-world networks tested in our experiments, demonstrating the generality and robustness of LGD-NA across domains and scales.

We build an ATLAS of 1,475 real-world networks across 32 complex systems domains, which is the largest and most diverse collection of real-world networks to date used for testing in network dismantling studies. We first test all methods across networks of up to 5,000 nodes and 205,000 edges without reinsertion (), and 38,000 edges with reinsertion (). To assess the practical running time of the best performing methods, we evaluate NBC and RA2 on even larger networks of up to 23,000 nodes and 507,000 edges ().

Current state-of-the-art dismantling algorithms have been evaluated on no more than 57 real-world networks (see

Table 1), with most algorithms tested on fewer than a dozen. Our experiments cover 1,475 networks, representing a substantial expansion.

A key aspect of our ATLAS dataset is the diversity of network types (see

Table 2). We test across 32 different complex systems domains, ranging from protein-protein interaction (PPI) to power grids, international trade, terrorist activity, ecological food webs, internet systems, brain connectomes, and road maps. Since fields vary in both the number of networks and their characteristics, we evaluate dismantling methods using a mean field approach, ensuring that fields with more networks do not dominate the overall evaluation. Also, because dismantling performance varies in scale across fields, we compute a mean field ranking to make results comparable across domains. Specifically, we rank all methods within each field based on their average AUC, then compute the mean of these rankings across all fields.

4.4. LGD-NA Performance and Comparison to Other Methods

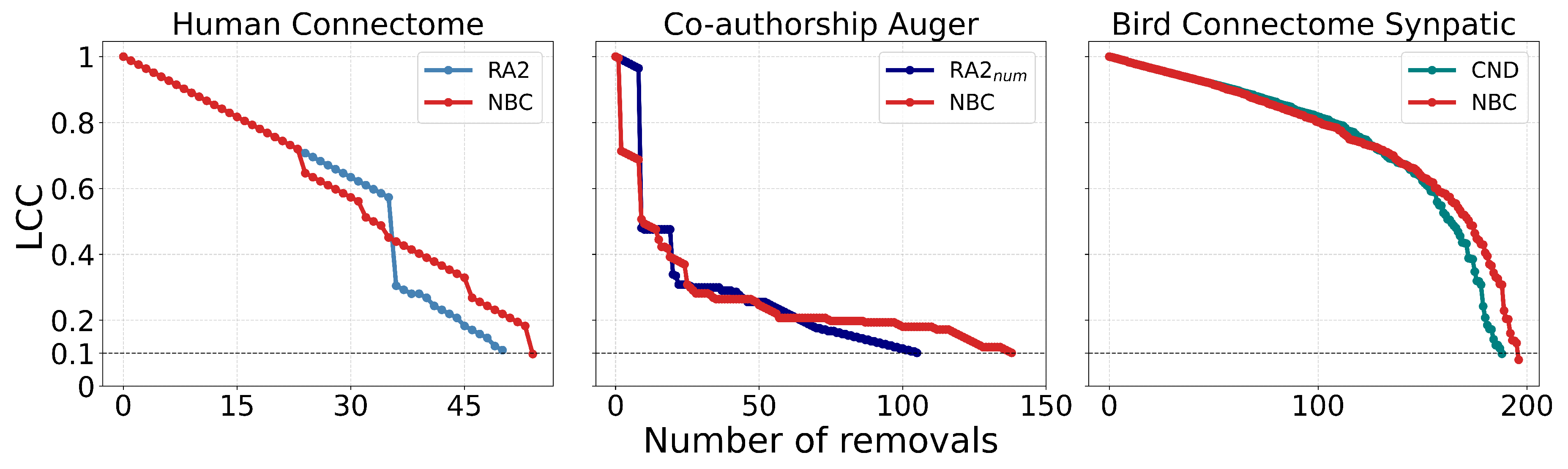

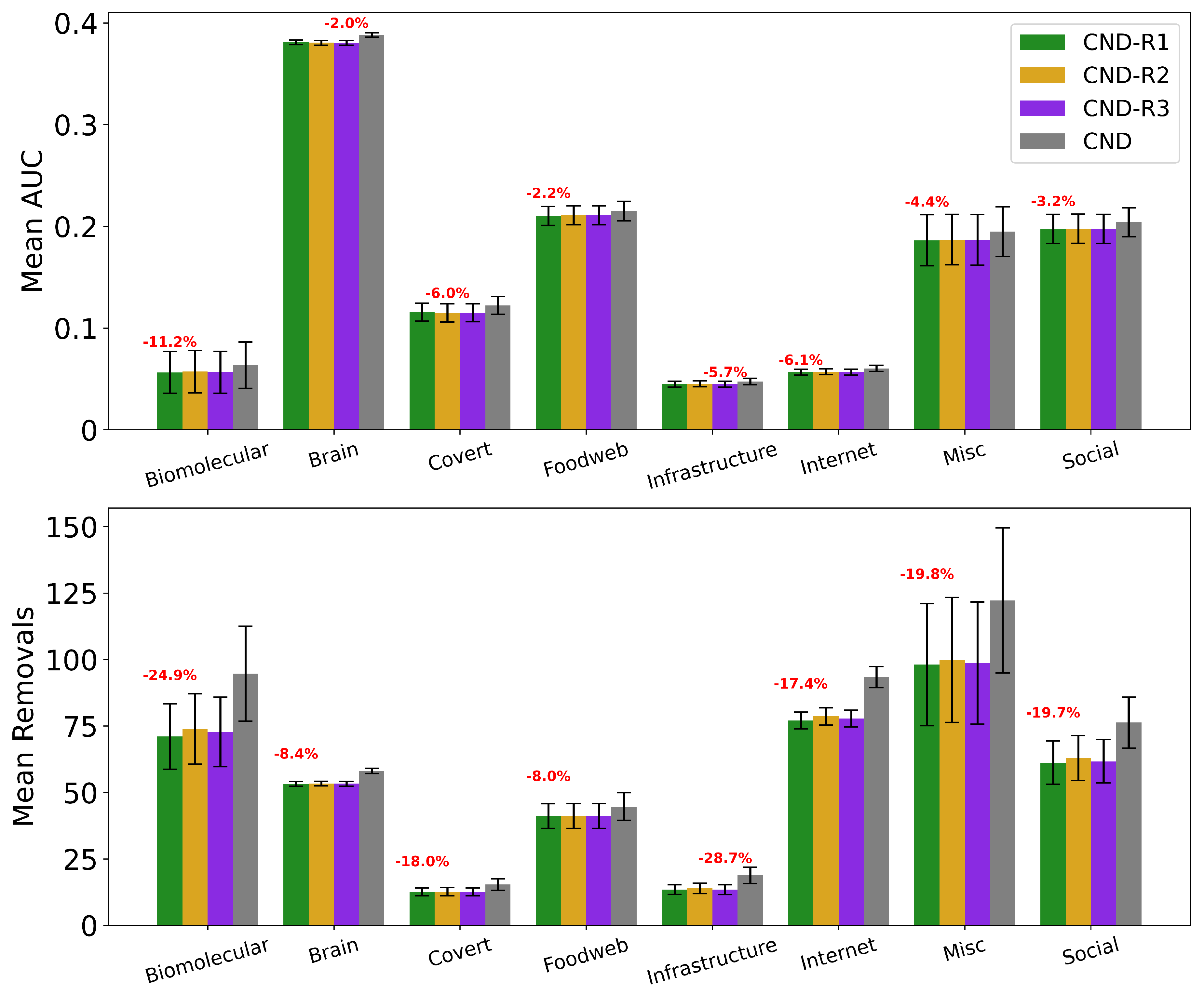

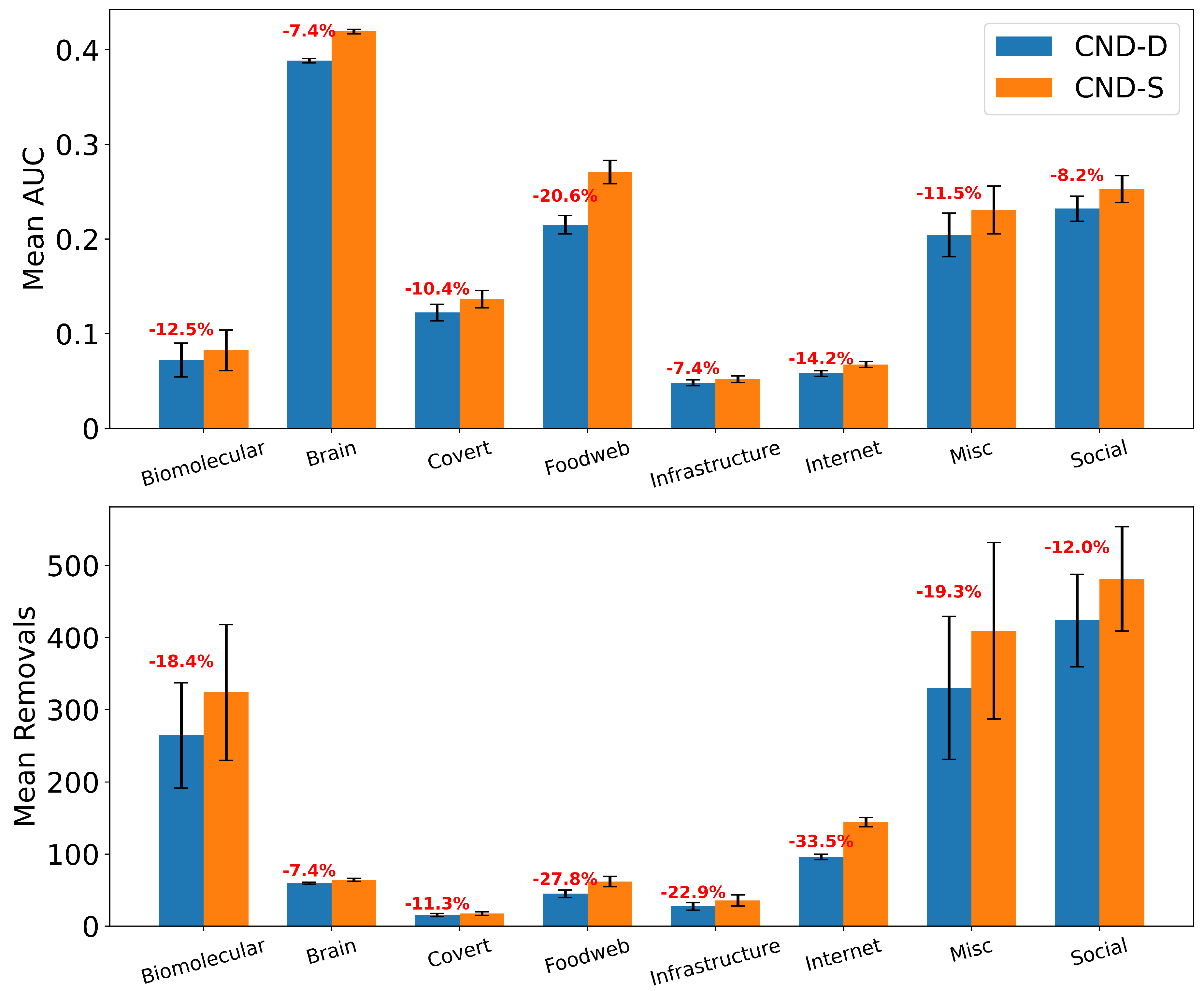

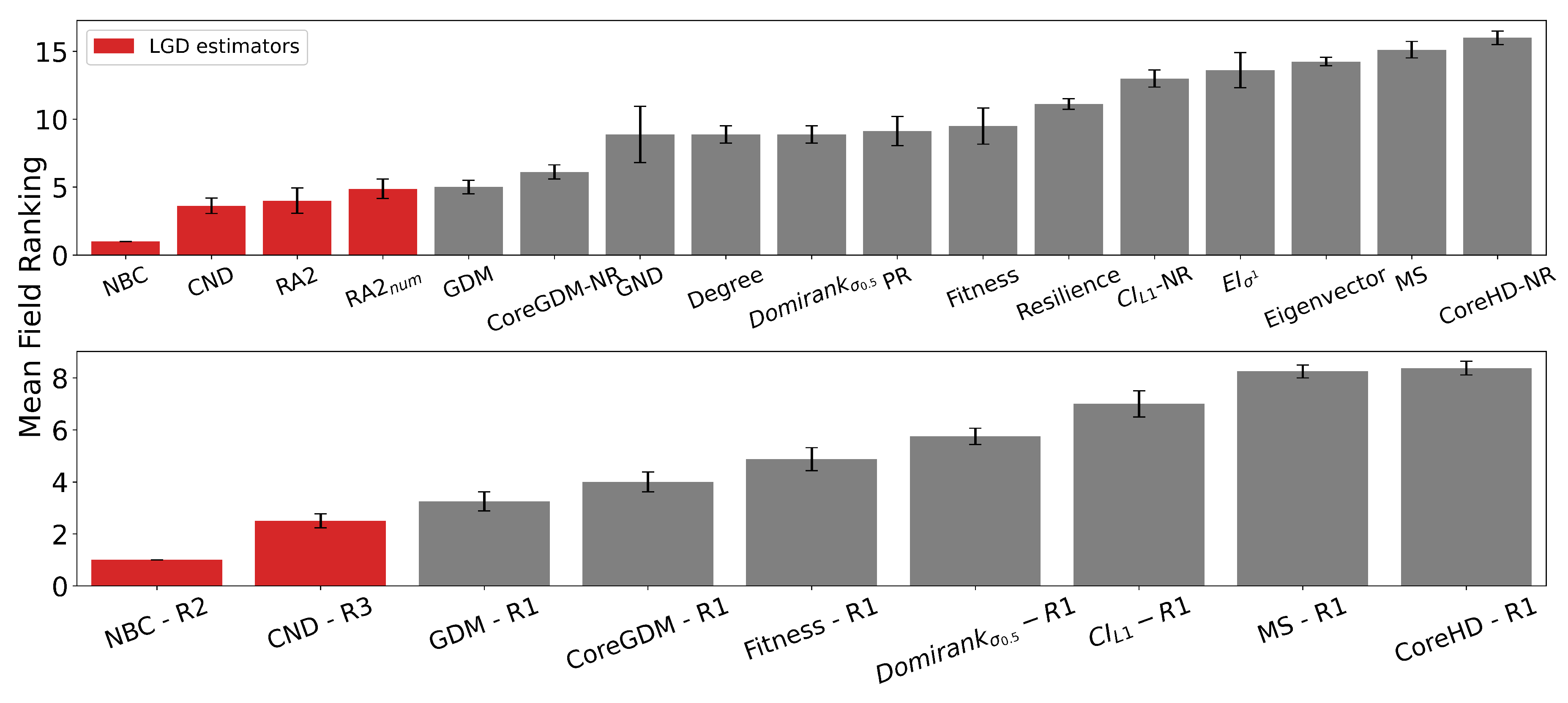

We compare our Latent Geometry-Driven Network Automata (LGD-NA) framework against the best-performing dismantling algorithms in the literature. Main results are shown in

Figure 2.

First, we find that all latent geometry network automata—NBC, RA2, and its variants—achieve top dismantling performance, both with and without reinsertion. These findings show that estimating the latent geometry of a network effectively reveals critical nodes for dismantling, confirming our first contribution.

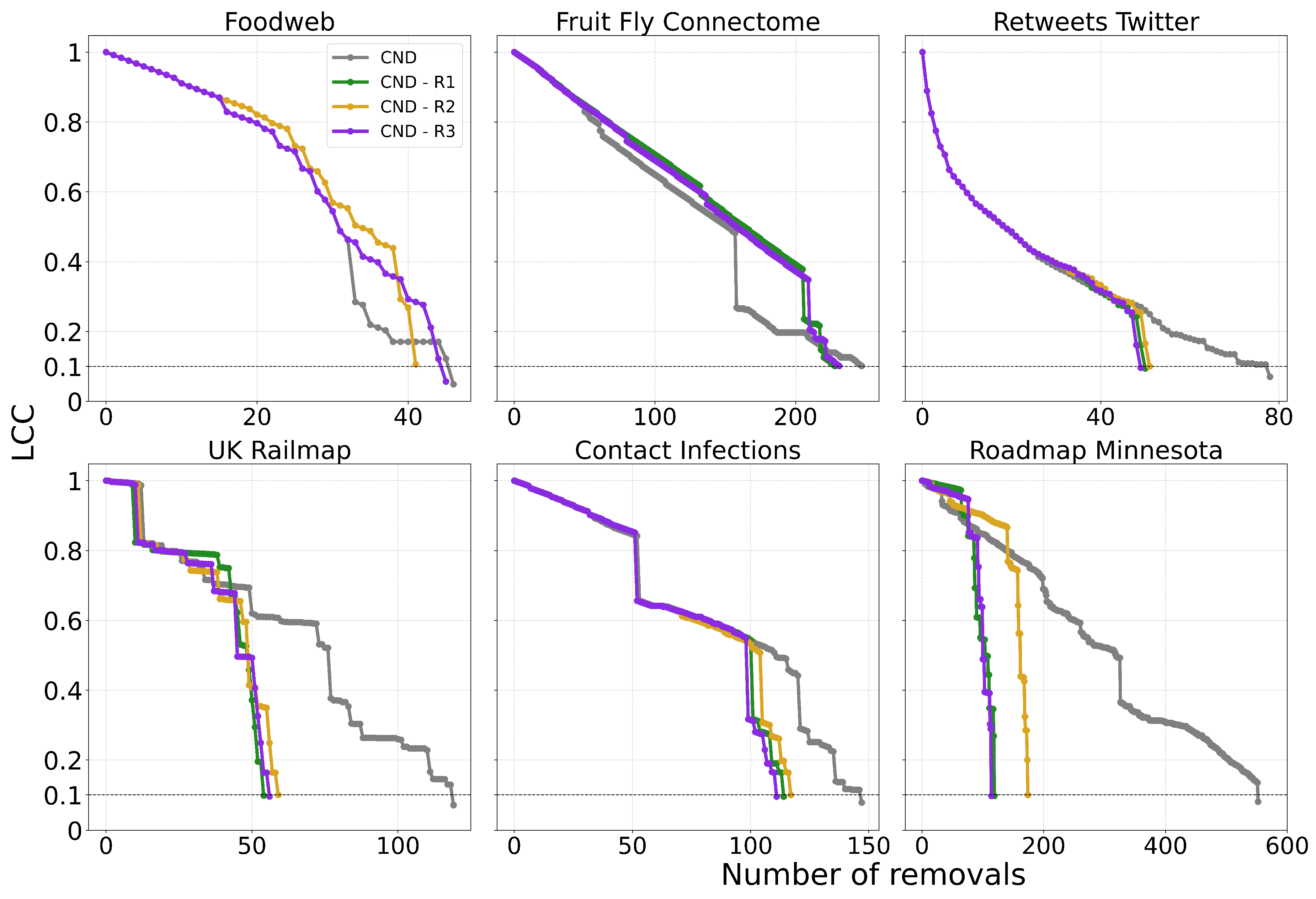

For each method, we evaluate three reinsertion strategies and report the best result. We show in

Figure A3 that using different reinsertion methods does not change the mean field ranking of the dismantling methods, and in

Figure A5 that the improvement in performance varies across fields and reinsertion methods (see

Figure A4 for an illustrative example). We also adopt a dynamic dismantling process for the network automata rules and all centrality measures, where we recompute the scores after each dismantling step, as it consistently outperforms the static variant (see

Figure A6 for an example of the improvements for CND and

Figure A7 for an illustrative example).

Second, we find that local network automata rules RA2, CND, and

—which adopt only the local network topology around a node—are highly effective. In particular, RA2 and its variants consistently outperform all other non-latent geometry-driven dismantling algorithms, including those relying on global topological measures or machine learning. This confirms our second contribution. See

Figure A2 for illustrative examples where the local network automata rules outperform NBC.

Third, we find that the simplest RA2 variant—based solely on inverse common neighbors, which we refer to as common neighbor dissimilarity (CND)—achieves the best performance among all local network automata rules. This is our third contribution and demonstrates that even minimal local topology-based information can effectively approximate latent geometry useful for effective dismantling.

LGD-NA outperforms all other methods, is robust to the inclusion or omission of reinsertion, and is validated across a large and diverse set of networks. These results strongly demonstrate the practical reliability of our latent geometry-driven dismantling framework, LGD-NA.

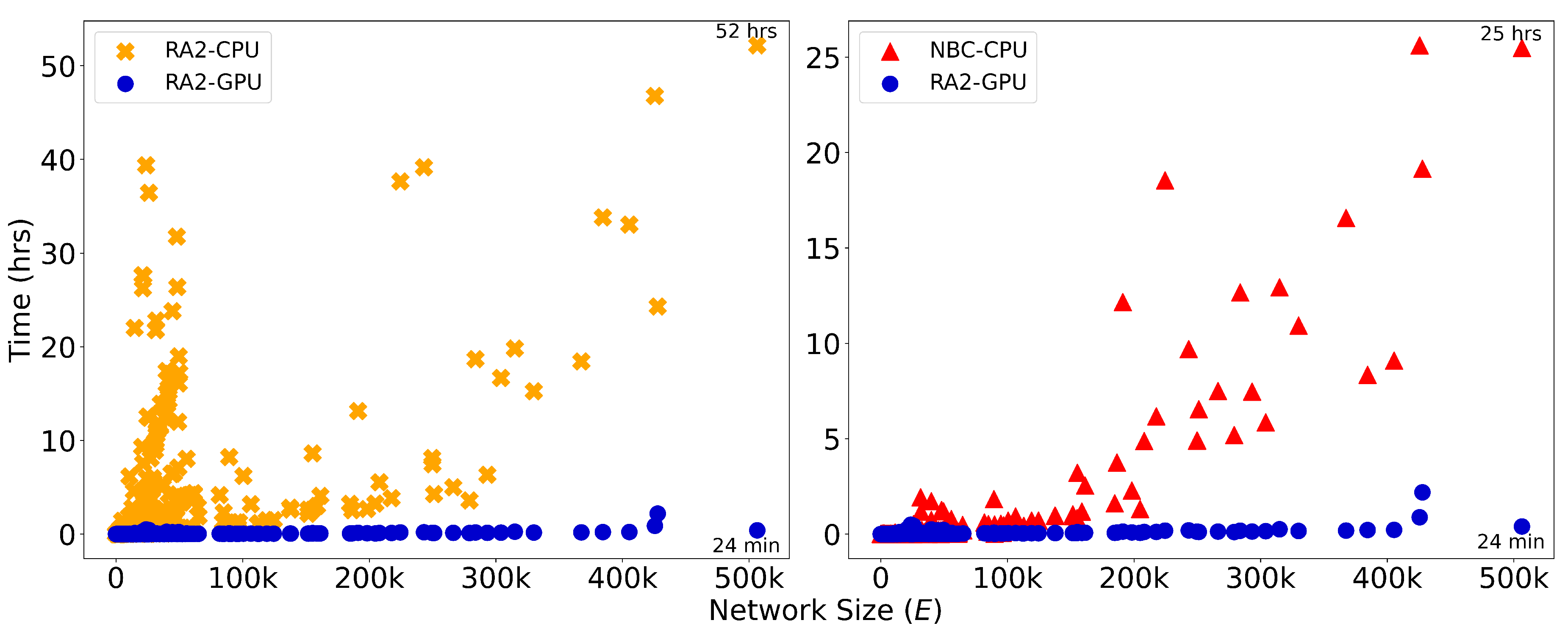

4.5. GPU Acceleration of LGD-NA for Large-Scale Dismantling

We implement GPU acceleration for all three LGD-NA variants by reformulating the required computations as matrix operations. On large networks, this enables a significant speedup in running time. Since the difference in running time between the three LGD-NA methods is not relevant, neither for CPU nor GPU, we report only the running time of RA2 in

Figure 3. For NBC, we report only CPU running time, as its GPU implementation did not yield any speedup. On the largest network, GPU-accelerated RA2 is 130 times faster than its CPU counterpart, highlighting the inefficiency of matrix multiplication on CPU. It is also over 63 times faster than NBC running on CPU, thanks to our GPU-optimized implementation. However, as noted earlier, NBC on CPU remains faster than RA2 on CPU, again due to the limitations of CPU-based matrix operations.

Overall, while NBC achieves better dismantling performance, its high computational cost makes it impractical for large-scale use. In contrast, thanks to our GPU-optimised implementation, our local latent geometry estimators based on network automata rules are the only viable option for efficient dismantling at scale.

Here, we look at the details of our matrix operations for the LGD-NA measures. First, the common neighbors matrix is computed as

where

is the adjacency matrix and ∘ denotes element-wise multiplication. Here,

counts the number of paths of length two—i.e., common neighbors—between all node pairs. The Hadamard product with

ensures that values are only retained for existing edges.

Next, we compute the number of external links a node has relative to each of its neighbors. Given the degree matrix

, the external degree matrix is:

Each entry of represents the external degree of node i with respect to node j: the number of neighbors of i that are neither connected to j nor directly connected to j itself. Non-edges are zeroed out.

These matrices allow efficient construction of RA2 and its variants using only matrix operations:

The time complexity is , with the common neighbor matrix being the dominant operation, for dense graphs, and for sparse graphs, N being the number of nodes and m the number of links. On CPU, matrix multiplication is typically memory-bound and limited by sequential operations. GPUs, however, are optimized for matrix operations, leveraging thousands of parallel threads. This results in a substantial speedup when implementing the GPU version. Note that in our experiments, the CPU-based RA2 implementation uses Python’s NumPy (implemented in C) while the GPU implementation uses Python’s CuPy (implemented in C++/CUDA).

We compare the GPU-accelerated local latent geometry estimator, RA2, with the global state-of-the-art method, Node Betweenness Centrality (NBC), which is also latent geometry-driven. While some studies report GPU implementations of NBC with improved performance [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51], these are often limited by hardware-specific optimizations, data-specific assumptions (e.g., small-world, social, or biological networks), and using heuristics that are tailored to specific settings rather than offering general solutions. Moreover, publicly available code is rare, making these approaches difficult to reproduce or integrate. Overall, NBC is not naturally suited for GPU implementation, as it does not rely on matrix multiplication, but is based on computing shortest path counts between all node pairs. In our experiments, the CPU-based NBC implementation from python’s

graph_tool (implemented in C++), based on Brandes’ algorithm [

52] with time complexity

for unweighted graphs, outperformed the GPU version from python’s

cuGraph (implemented for C++/CUDA). The former is therefore used as the baseline for NBC.