1. Introduction

In today's rapidly changing living conditions, there has been an increase in environmental, social, and individual risk factors that threaten individuals' psychological well-being and mental health [

1,

2]. This situation has led to a global rise in the prevalence of common mental disorders such as depression, stress, and anxiety, significantly impacting individuals’ quality of life [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Recent research has shown that individuals' lifestyle choices are closely associated with these psychological problems [

7,

8]. For example, unhealthy lifestyle habits in individuals with polycystic ovary syndrome have been found to be related to depressive symptoms [

9]. Similarly, high levels of physical activity among medical students have been reported to reduce the risk of depression [

10]. These various examples indicate that lifestyle components strongly interact with mental health not only in healthy individuals but also in diverse risk groups.

The fundamental components of a healthy lifestyle include regular physical activity [

11,

12,

13], balanced nutrition [

14,

15], adequate and quality sleep [

16], and effective stress management [

11,

17]. The integrated implementation of these elements has been shown to reduce levels of depression, anxiety, and stress while supporting individuals’ psychological well-being [

18,

19]. In particular, physical activity not only directly alleviates symptoms of depression and anxiety but also indirectly enhances stress coping skills and strengthens social support systems [

5,

20,

21,

22]. The combined application of balanced nutrition and physical activity has been reported to yield more effective outcomes than isolated interventions [

23]. Furthermore, quality sleep habits and mindfulness-based relaxation techniques also play a vital role in the maintenance of mental health [

19,

24]. However, the sustainability of these behaviors depends on individuals possessing the necessary knowledge, skills, and motivational infrastructure to support their lifestyle choices. At this point, the concept of physical literacy emerges as a significant variable.

Physical literacy is a multidimensional competence domain that encompasses the knowledge, skills, motivation, and confidence necessary to support lifelong participation in physical activity [

25,

26,

27,

28]. The literature indicates that individuals with high levels of physical literacy tend to experience lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress [

29,

30]. In this context, physical literacy is considered a mediating variable through which individuals can promote their mental health via physical activity [

29]. Studies conducted on university students have shown that levels of physical literacy and mindfulness partially mediate the effects of psychological distress on life satisfaction [

31,

32].

Nonetheless, empirical evidence explaining the potential mediating role of physical literacy in the relationship between a sustainable healthy lifestyle and depression, stress, and anxiety remains limited. Therefore, there is a need to comprehensively investigate the effects of physical literacy on mental health and to clarify the underlying mechanisms of this relationship. In this context, the first aim of the present study is to examine the effects of a sustainable healthy lifestyle on depression, stress, and anxiety, the second aim is to test the mediating role of physical literacy in this relationship.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A cross-sectional digital survey was developed using the Google Forms platform (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA) and was distributed to a broad sample of participants. The study is reported in accordance with the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) [

33] and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [

34]. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Research and Publication Ethics Committee of Social and Human Sciences at Inönü University (Approval number: 2025/16).

2.2. Participants

In the theoretical model of the study, a sustainable healthy lifestyle was positioned as the independent variable; anxiety, stress, and depression were defined as dependent variables; and physical literacy was considered a mediating variable. The minimum number of participants required for this study was calculated using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7; University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). Assuming an effect size of 0.02, an alpha level (α) of 0.05, a power (1-β) of 0.80, and five predictors, the analysis indicated that at least 647 participants were needed. Accordingly, a total of 652 participants who volunteered were included in the study. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant ethical guidelines. The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1.

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: participants had to be currently enrolled university students who voluntarily agreed to participate after being informed about the study’s purpose and procedures. Individuals were required to have access to the internet to complete the online survey administered via Google Forms and be capable of providing informed consent. Only those who completed all sections of the survey—ensured by mandatory response settings—were included in the analysis. The exclusion criteria involved any individuals who did not consent to participate, submitted incomplete responses, or attempted to participate more than once, as only single entries per participant were permitted. Additionally, individuals who were not part of the intended student population or whose academic affiliation could not be verified were excluded. While participants experiencing psychological distress were not explicitly excluded, the survey design included a debriefing with information about support services, acknowledging that the study was not intended to target individuals undergoing acute psychological crises.

2.3. Data Collection Tools

The order of the data collection tools used in the study was structured to minimize participants’ cognitive and emotional burden. First, a Demographic Information Form was administered to obtain basic demographic details such as age, gender, and physical activity status. Following this, the Healthy and Sustainable Lifestyle Scale was applied, which included more neutral questions regarding participants’ general lifestyle and behaviors. Third, the Perceived Physical Literacy Scale was used to assess participants’ perceptions of physical activity. Finally, the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21), containing more sensitive content related to psychological conditions, was administered. This sequence was designed to prevent emotional bias from affecting responses to other scales and to enhance data reliability. Additionally, after completing the DASS-21, participants were informed about available support services if needed.

2.4. Healthy and Sustainable Lifestyle Scale

To assess individuals' levels of sustainable healthy lifestyle, the Healthy and Sustainable Lifestyle Scale developed by Choi & Feinberg [

35] and adapted into Turkish by Gökkaya [

36] was used. This scale consists of 28 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). Confirmatory factor analysis showed a good model fit, and the Cronbach's alpha internal consistency coefficient was reported as high (α > .80) [

36]. For the current study sample, the confirmatory factor analysis yielded acceptable fit indices (χ² = 142.720, Df = 18, CFI = 0.985, TLI = 0.973, NFI = 0.979, IFI = 0.985, RMSEA = 0.064, SRMR = 0.027), and the Cronbach’s alpha for this study was calculated as 0.883.

2.5. Perceived Physical Literacy Scale

To evaluate the level of physical literacy, the Perceived Physical Literacy Scale developed by Sum et al. [

37] and adapted into Turkish by Yılmaz & Kabak [

38] was utilized. The scale includes 9 items and is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). Confirmatory factor analysis indicated good fit indices and high reliability [

38]. In this study, the confirmatory factor analysis results for the scale showed acceptable model fit (χ² = 87.536, Df = 22, CFI = 0.971, TLI = 0.952, NFI = 0.961, IFI = 0.971, RMSEA = 0.068, SRMR = 0.033), and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated as 0.849.

2.6. Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21)

To assess levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, the DASS-21 developed by Lovibond & Lovibond [

39] and adapted into Turkish by Sariçam [

40] was used. The scale consists of 21 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = Never to 3 = Almost Always, based on the participants’ experiences over the past week. The Turkish version demonstrated good model fit and high internal consistency with reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of α = 0.87 for depression, α = 0.85 for anxiety, and α = 0.81 for stress [

36]. For the present sample, confirmatory factor analysis showed acceptable fit indices (χ² = 453.596, Df = 97, CFI = 0.921, TLI = 0.902, NFI = 0.902, IFI = 0.921, RMSEA = 0.075, SRMR = 0.042), and the Cronbach’s alpha values were α = 0.813 for depression, α = 0.790 for anxiety, and α = 0.815 for stress.

2.7. Data Collection Process

The data collection process began in April 2025, following ethical approval from the Research and Publication Ethics Committee of Social and Human Sciences at Inönü University. Participants were informed about the purpose and scope of the study, and data were collected based on voluntary participation. The survey link was shared with university students via social media groups, emails, and student communities. Informed consent was obtained before participation, and participants were assured that their involvement was entirely voluntary and that the data would be used solely for scientific purposes. The survey took approximately six minutes to complete, and each participant was allowed to participate only once. After collecting demographic information, the scales were administered in the predetermined order. To prevent missing data, each question was marked as mandatory, ensuring full completion. All responses were collected anonymously, and the confidentiality of personal information was strictly maintained. The data were securely stored in digital environments and used solely for the purposes of this research.

2.8. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the JASP statistical software (version 0.18.3.0; University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands). The normality of the data distribution was assessed by examining skewness and kurtosis values within the ±2 range [

41,

42,

43]. The results indicated that the data were normally distributed (

Table 2). Consequently, Pearson correlation analysis was employed to examine the relationships among the variables. In the study, sustainable healthy lifestyle was treated as the independent variable, while anxiety, stress, and depression were the dependent variables. Physical literacy was considered a mediating variable in explaining this relationship. To test the statistical significance of the mediation effect, a bootstrapping method with 5000 samples was applied. The 95% confidence intervals obtained from this procedure were used to evaluate the significance of the indirect effects; the absence of zero within these intervals indicated statistically significant indirect effects.

3. Results

The findings obtained within the scope of the research are presented below through tables and figures. In this context, the relationships between a healthy and sustainable lifestyle, physical literacy, anxiety, stress, and depression are presented in

Table 2.

According to the correlation results presented in

Table 2, a significant negative relationship was found between a healthy and sustainable lifestyle and anxiety (r = –0.479, p < 0.001). Similarly, a significant negative relationship was observed between a healthy and sustainable lifestyle and stress (r = –0.446, p < 0.001), and between a healthy and sustainable lifestyle and depression (r = –0.477, p < 0.001). Moreover, there was a significant positive relationship between a healthy and sustainable lifestyle and physical literacy (r = 0.497, p < 0.001). Physical literacy was found to be significantly negatively related to anxiety (r = –0.760, p < 0.001), stress (r = –0.703, p < 0.001), and depression (r = –0.689, p < 0.001). Additionally, significant positive correlations were observed between anxiety and stress (r = .666, p < .001), anxiety and depression (r = 0.712, p < 0.001), and stress and depression (r = 0.680, p < 0.001).

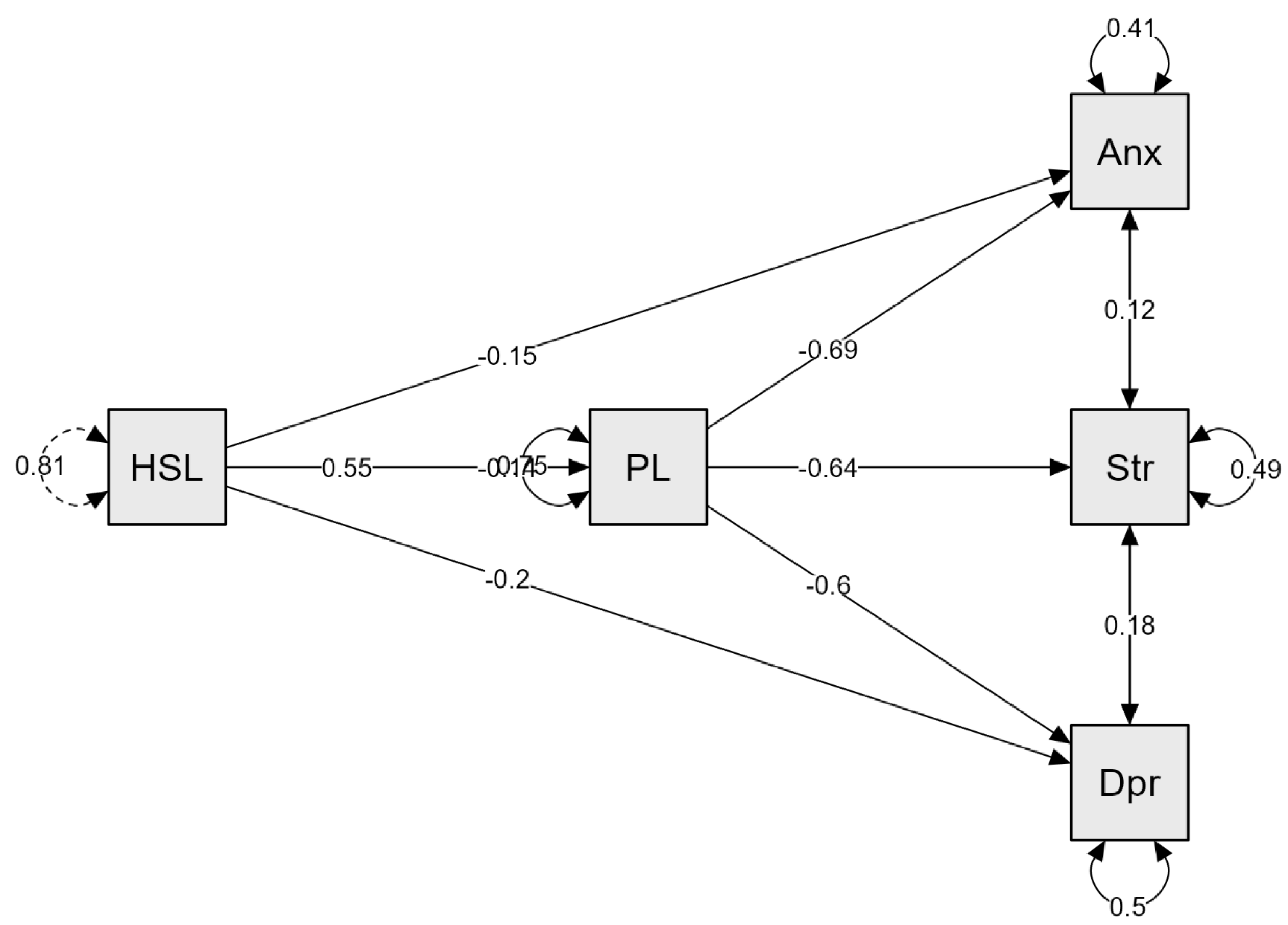

Table 3 presents the findings on the mediating role of physical literacy (PL) in the relationship between a healthy and sustainable lifestyle (HSL) and anxiety, stress, and depression. Regarding direct effects, the impact of PL on anxiety was found to be statistically significant (β = –0.694, z = –24.065, 95% CI [–0.750, –0.637]), as was the direct effect of HSL on anxiety (β = –0.149, z = –4.648, 95% CI [–0.212, –0.086]). Similarly, the direct effect of PL on stress was significant (β = –0.640, z = –20.193, 95% CI [–0.702, –0.577]), along with the direct effect of HSL on stress (β = –0.143, z = –4.063, 95% CI [–0.212, –0.074]). The effect of PL on depression was also statistically significant (β = –0.599, z = –18.751, 95% CI [–0.662, –0.537]), as was the effect of HSL on depression (β = –0.200, z = –5.627, 95% CI [–0.270, –0.130]). Furthermore, HSL was found to significantly predict PL (β = 0.553, z = 14.612, 95% CI [0.479, 0.627]). Regarding indirect effects, the mediating role of PL in the relationship between HSL and anxiety was found to be significant (β = –0.384, z = –12.490, 95% CI [–0.444, –0.324]). Similarly, the indirect effects of HSL on stress (β = –0.354, z = –11.838, 95% CI [–0.412, –0.295]) and depression (β = –0.331, z = –11.526, 95% CI [–0.388, –0.275]) through PL were also significant. These results confirm the mediating role of PL in the relationship between HSL and psychological symptoms (anxiety, stress, and depression). Regarding total effects, HSL significantly affected anxiety (β = –0.533, z = –13.919, 95% CI [–0.608, –0.458]), stress (β = –0.497, z = –12.736, 95% CI [–0.573, –0.420]), and depression (β = –0.532, z = –13.875, 95% CI [–0.607, –0.457]). The variance explained by HSL and PL in anxiety was 59%, in stress 51%, in depression 50%, and in PL by HSL 25%.

The structural equation model examining the mediating role of physical literacy in the relationship between HSL and anxiety, stress, and depression, is illustrated in

Figure 1. As shown in the model, the direct effect of HSL on PL is significant and positive (β = 0.55). In contrast, the direct effects of HSL on anxiety (β = –0.15), stress (β = –0.14), and depression (β = –0.20) are negative. Physical literacy has strong negative effects on anxiety (β = –0.69), stress (β = –0.64), and depression (β = –0.60). Additionally, the model indicates a strong mediating role of PL, suggesting that the impact of HSL on psychological symptoms is largely mediated through PL. The model also shows that stress has positive effects on both anxiety (β = 0.12) and depression (β = 0.18).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the relationship between a sustainable healthy lifestyle and symptoms of depression, stress, and anxiety, and to determine the mediating role of physical literacy within this relationship. The findings revealed that maintaining a healthy and sustainable lifestyle significantly contributes to psychological well-being. Specifically, significant and negative relationships were identified between a sustainable healthy lifestyle and the levels of depression, stress, and anxiety. Furthermore, as levels of physical literacy increased, these psychological symptoms decreased; physical literacy was found to play a significant and strong mediating role in these relationships. These findings suggest that healthy lifestyle behaviors provide not only physiological but also substantial psychological protective benefits.

According to the structural equation model, the effect of a healthy sustainable lifestyle on physical literacy was significant and positive. This indicates that lifestyle components such as regular physical activity, healthy eating, and adequate sleep contribute to enhancing individuals’ physical competence and awareness. Additionally, physical literacy was found to have significant negative effects on depression, stress, and anxiety. This underscores that physical literacy is not only a determinant of physical functionality but also a key variable in psychological well-being. The study also revealed that the effects of a healthy sustainable lifestyle on psychological symptoms are largely mediated through physical literacy. Thus, physical literacy may be considered a mechanism through which the psychological effects of healthy lifestyle behaviors are channeled and guided.

The findings are consistent with existing literature. Individuals with higher levels of physical literacy tend to exhibit better psychological health indicators. For instance, negative associations have been reported between physical literacy and internalization problems or overall psychological difficulties [

44]. Moreover, physical literacy has been shown to play a crucial role in reducing burnout through resilience [

45]. In children, higher levels of physical literacy have been associated with better quality of life [

46]. In line with these findings, the current study also confirms physical literacy as a mediating mechanism that supports psychological health.

The correlation results obtained in this study further support these conclusions. Moderate negative relationships were found between a sustainable healthy lifestyle and depression, stress, and anxiety, while the correlations between physical literacy and these psychological symptoms were even stronger. The literature provides substantial evidence that lifestyle factors such as physical activity and nutrition significantly affect mental health. Physical activity has been shown to exert both direct and indirect effects in reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression [

5]. A systematic review has highlighted the consistency of these effects across diverse demographic groups [

47]. Physical literacy is also recognized as a significant factor for mental health. Individuals with adequate physical literacy tend to engage in higher levels of physical activity and report fewer psychological symptoms [

29]. Furthermore, across various cultural contexts, individuals with higher healthy lifestyle scores have been found to experience lower levels of depression and anxiety [

9,

48]. These findings suggest that enhanced bodily awareness and movement competence contribute effectively to regulating emotions such as anxiety and internal restlessness.

On the other hand, the positive effects of stress on both anxiety and depression observed in the model indicate that stress is a core trigger of psychological disorders. This finding aligns with Lazarus and Folkman’s [

49] stress theory, which posits that when individuals lack adequate coping mechanisms, the risk of psychological maladjustment increases. In this study, increased levels of stress were accompanied by higher levels of anxiety and depression. These results support the preventive role of lifestyle behaviors and physical literacy in enhancing stress management skills.

The explained variances in the model are also noteworthy. Together, sustainable lifestyle and physical literacy accounted for 59% of the variance in anxiety, 51% in stress, and 50% in depression. These high levels of explained variance demonstrate that the model has strong explanatory power and that the findings are grounded in robust statistical evidence. Additionally, the fact that a sustainable lifestyle explained 25% of the variance in physical literacy highlights the significant role of lifestyle variables in the development of physical literacy.

Accordingly, the relationship between a sustainable lifestyle and psychological symptoms should not be viewed merely as a superficial correlation, but rather as an explanatory and potentially causal association. The growing body of literature suggests that healthy behaviors such as regular physical activity and balanced nutrition positively impact individuals' psychological resilience [

50,

51,

52]. Similarly, physical literacy has been shown to contribute to individuals' psychological well-being and reduce the severity of psychological symptoms [

24,

45,

53]. The variance ratios obtained in this context are both theoretically and practically significant and emphasize the importance of interventions based on physical literacy in the development of psychological health.

Based on the practical implications of this study, the following recommendations can be made: For educators, health professionals, and policymakers, it is not sufficient to simply encourage individuals to adopt physical activity habits. It is equally important to enhance individuals’ levels of physical literacy—ensuring that their relationships with their bodies are conscious, competent, and sustainable. In this regard, integrating physical literacy-based approaches into schools, sports clubs, and community-based health programs can be effective in promoting both physical and psychological health. Focusing on this dimension in intervention programs aimed at adolescents and young adults can offer a strategic contribution to supporting mental health.

Despite the valuable insights provided by this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the use of a cross-sectional design restricts the ability to infer causality among the variables. While the structural equation model reveals meaningful associations, only longitudinal or experimental designs can confirm directional relationships over time. Second, the reliance on self-report instruments may have introduced biases such as social desirability and common method variance. Although validated scales were used, objective or behavioral measures (e.g., wearable fitness trackers or observational assessments of physical literacy) could provide more robust data in future research. Additionally, the sample was limited to university students, which may constrain the generalizability of the findings to broader populations, including older adults or individuals with different educational or socioeconomic backgrounds. The use of a digital survey distributed via convenience sampling may also limit representativeness, as individuals without internet access or lower digital literacy could have been excluded. Lastly, cultural and contextual factors unique to the Turkish setting in which the study was conducted may influence lifestyle behaviors and perceptions of mental health and physical literacy. Future studies should consider cross-cultural comparisons to examine the universality of these findings.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study has filled a significant gap in the field by revealing the holistic effects of a healthy sustainable lifestyle and physical literacy on psychological well-being. The findings demonstrate that it is not only the act of being physically active that contributes to mental health, but also the manner in which these activities are performed-consciously, competently, and meaningfully. Physical literacy has clearly emerged as a fundamental component that bridges healthy lifestyle behaviors and psychological symptoms. In this context, if the goal is to prevent psychological disorders and enhance mental resilience, physical literacy should be considered a central component in educational, healthcare, and community-based programs. Future research employing longitudinal and multidimensional designs will further enrich the theoretical and practical knowledge base in this area by offering deeper insights into these relationships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.A., I.I., Z.Ç. and C.I.A.; methodology, M.A., I.I., Z.Ç., C.I.A. and R.P.; software, R.P., A.M.V. and N.L.V.; validation, M.A., I.I., Z.Ç., R.P., A.M.V., N.L.V. and A.C.Ș.; formal analysis, I.I. and Z.Ç.; investigation, M.A., I.I., and Z.Ç.; resources: R.P., A.M.V. and A.C.Ș.; data curation, M.A., I.I., Z.Ç. and R.P.; writing— original draft preparation, M.A., I.I., Z.Ç. and C.I.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A., I.I., Z.Ç., R.P., A.M.V., N.L.V., C.I.A., and A.C.Ș.; visualization, I.I., Z.Ç., R.P. and A.C.Ș.; supervision, M.A., R.P., and C.I.A.; project administration, M.A., I.I. and C.I.A.; funding A.M.V., N.L.V., and A.C.Ș. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research and Publication Ethics Committee of Social and Human Sciences at Inönü University (Approval number: 2025/16).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. Filippo Maselli (Department of Human Neurosciences, Sapienza University of Rome) for his valuable contributions in reviewing our manuscript. His meticulous feedback and constructive suggestions have significantly enhanced the scientific quality of our work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cattan, M. Mental Health and Well Being in Later Life. McGraw-Hill Education (UK); 2009.

- Keyes CLM, editor. Mental Well-Being: International Contributions to the Study of Positive Mental Health, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2013 [cited 2025 Apr 7]. Available from, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Inoue T, Kimura T, Inagaki Y, Shirakawa O. Prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders and their associated factors in patients with bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 1695. 2020;16:1695–704. [CrossRef]

- Kartal D, Kiropoulos L. Effects of acculturative stress on PTSD, depressive, and anxiety symptoms among refugees resettled in Australia and Austria. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2016;7(1):28711. [CrossRef]

- Martinez VML, da Silva Martins M, Capra F, Schuch FB, Wearick-Silva LE, Feoli AMP. The impact of physical activity and lifestyle on mental health: A network analysis. J Phys Act Health. 2024;21(12):1330–40.

- Toczko M, Merrigan J, Boolani A, Guempel B, Milani I, Martin J. Influence of grit and healthy lifestyle behaviors on anxiety and depression in US adults at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional study. 2022;12(1):77–84. Health Promot Perspect. [CrossRef]

- Gyasi RM, Abass K, Adu-Gyamfi S. How do lifestyle choices affect the link between living alone and psychological distress in older age? Results from the AgeHeaPsyWel-HeaSeeB study. 2020;20(1):859. BMC Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsdottir G, Gisladottir TL, Stefansdottir RS, Rognvaldsdottir V, Johannsson E, Stefansson V, Gestsdottir S. Changes in health-related lifestyle choices of university students before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations between food choices, physical activity and health. PLoS One. 2023;18(6):e0286345. [CrossRef]

- Li L, Kang Z, Chen P, Niu B, Wang Y, Yang L. Association between mild depressive states in polycystic ovary syndrome and an unhealthy lifestyle. 2024;12. Front Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Dodin Y, Obeidat N, Dodein R, Seetan K, Alajjawe S, Awwad M, et al. Mental health and lifestyle-related behaviors in medical students in a Jordanian University, and variations by clerkship status. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):1283. [CrossRef]

- Kris-Etherton PM, Sapp PA, Riley TM, Davis KM, Hart T, Lawler O. The Dynamic Interplay of Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors for Cardiovascular Health. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2022;24(12):969-80.

- Sunda M, Gilic B, Sekulic D, Matic R, Drid P, Alexe DI, Cucui GG, Lupu GS. Out-of-School Sports Participation Is Positively Associated with Physical Literacy, but What about Physical Education? A Cross-Sectional Gender-Stratified Analysis during the COVID-19 Pandemic among High-School Adolescents. Children, 2022; 9(5):753. [CrossRef]

- Ljubojevic A, Jakovljevic V, Bijelic S, Sârbu I, Tohănean DI, Albină C, Alexe DI. The Effects of Zumba Fitness® on Respiratory Function and Body Composition Parameters: An Eight-Week Intervention in Healthy Inactive Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2023; 20(1):314. [CrossRef]

- Mate A, Reyes-Goya C, Santana-Garrido Á, Vázquez CM. Lifestyle, maternal nutrition and healthy pregnancy. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2020;19(2):132–40. [CrossRef]

- Ródenas-Munar M, Fitó M, Labayen I, Sevilla-Sánchez M, Pulgar S, Serra-Majem L, et al. Perceived quality of life is related to a healthy lifestyle and related outcomes in Spanish children and adolescents: The Physical Activity, Sedentarism, and Obesity in Spanish Study. Nutrients. 2023;15(24):5125. [CrossRef]

- Alruwaili NW, Alqahtani N, Alanazi MH, Alanazi BS, Aljrbua MS, Gatar OM. The effect of nutrition and physical activity on sleep quality among adults: A scoping review. 2023;7(1):8. Sleep Sci Pract. [CrossRef]

- Kris-Etherton PM, Lobelo F, Morris PB, Furie KL, Sacks FM, Lear SA, et al. Special considerations for healthy lifestyle promotion across the life span in clinical settings: A science advisory from the American Heart Association. 2021;144(24):e651–69. Circulation. [CrossRef]

- Lacerda DA de, Vale MEM do, Oliveira AVL de, Celeste HE, Cruz KRF, Miranda JLF, et al. The influence of physical activity on mental health: A systematic review. 2024;14(2):283–5. Rev Cient Sistematica. [CrossRef]

- Ramdani RF, Herlambang AD, Falhadi MM, Fadilah MZ, Turnip CEL, Mulyana A. Membangun kesejahteraan pikiran untuk kesehatan mental melalui gaya hidup sehat dan olahraga. Indo-MathEdu Intellect J. 2024;5(3):2928–36.

- Alexe DI, Abalsei BA, Mares G, Rata BC, Iconomescu TM, Mitrache G, Burgueño R. Psychometric Assessment of the Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale with Professional Romanian Athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1696. [CrossRef]

- Alexe DI, Cîrtiţă, BC, Tohănean, DI, Larion A, Alexe CI, Dragos P, Burgueño R. Interpersonal Behaviors Questionnaire in Sport: Psychometric Analysis With Romanian Professional Athletes. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 2022, 130(1), 315125221135669, 497-519. [CrossRef]

- Alexe CI, Alexe DI, Mareş G, Tohănean DI, Turcu I, Burgueño R. Validity and reliability evidence for the Behavioral Regulation in Sport Questionnaire with Romanian professional athletes. PeerJ, 1280; e3. [CrossRef]

- Amiri S, Mahmood N, Javaid SF, Khan MA. The effect of lifestyle interventions on anxiety, depression and stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Healthcare. 2263. [CrossRef]

- Wong VWH, Yiu EKL, Ng CH, Sarris J, Ho FYY. Unraveling the associations between unhealthy lifestyle behaviors and mental health in the general adult Chinese population: A cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. [CrossRef]

- Gilic B, Sekulic D, Munoz MM, Jaunig J, Carl J. Translation, cultural adaptation, and psychometric properties of the Perceived Physical Literacy Questionnaire (PPLQ) for adults in Southeastern Europe. J Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Majić B, Gilic B, Ajduk-Kurtović M, Brekalo M, Šajber D. Physical Literacy Levels in the Croatian Adult Population; Gender Differences and Associations with Participation in Organized Physical Activity. 2024;22(2):33-8. Sport Mont.

- Nurjanah N, Mubarokah K, Haikal H, Setiono O, Belladiena AN, Muthoharoh NA, et al. Is adolescent physical literacy linked to their mental health? Jurnal Promkes. /: Available from: https, 8669.

- Rajkovic Vuletic P, Gilic B, Zenic N, Pavlinovic V, Kesic MG, Idrizovic K, vd. Analyzing the Associations between Facets of Physical Literacy, Physical Fitness, and Physical Activity Levels: Gender- and Age-Specific Cross-Sectional Study in Preadolescent Children. Education Sciences. Nisan 2024.

- Christodoulides E, Tsivitanidou O, Sofokleous G, Grecic D, Sinclair JK, Dana A, et al. Does physical activity mediate the associations between physical literacy and mental health during the COVID-19 post-quarantine era among adolescents in Cyprus? 2023;3(3):823–34. Youth. [CrossRef]

- Esteves CS, Oliveira CR de, Argimon II de L. Social distancing: Prevalence of depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms among Brazilian students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 5899. [CrossRef]

- Dong X, Huang F, Shi X, Xu M, Yan Z, Türegün M. Mediation impact of physical literacy and activity between psychological distress and life satisfaction among college students during COVID-19 pandemic. SAGE Open. 2158. [CrossRef]

- Kan W, Huang F, Xu M, Shi X, Yan Z, Türegün M. Exploring the mediating roles of physical literacy and mindfulness on psychological distress and life satisfaction among college students. PeerJ. 1774. [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of web surveys: The checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES) 2004;6(3):e34. J Med Internet Res.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–7.

- Choi S, Feinberg RA. The LOHAS (lifestyle of health and sustainability) scale development and validation. Sustainability. 2021;13(4):1598. [CrossRef]

- Gökkaya, D. Sağlıklı ve sürdürülebilir yaşam tarzı ölçeği: Türkçe geçerlilik ve güvenirlik çalışması. İnsan ve Toplum Bilimleri Araştırmaları Dergisi. 2024;13(3):1173–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum RKW, Cheng CF, Wallhead T, Kuo CC, Wang FJ, Choi SM. Perceived physical literacy instrument for adolescents: A further validation of PPLI. 2018;16(1):26–31. J Exerc Sci Fit. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz A, Kabak S. Perceived Physical Literacy Scale for Adolescents (PPLSA): Validity and reliability study. 2021;9(1):159–71. Int J Educ Literacy Stud.

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. [CrossRef]

- Sariçam, H. The psychometric properties of Turkish version of Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) in health control and clinical samples. J Cogn Behav Psychother Res. [CrossRef]

- Kim, HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. [CrossRef]

- Mishra P, Pandey CM, Singh U, Gupta A, Sahu C, Keshri A. Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Ann Card Anaesth. [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. P: New York (NY), 2019.

- Tang Y, Algurén B, Pelletier C, Naylor PJ, Faulkner G. Physical Literacy for Communities (PL4C): Physical literacy, physical activity and associations with wellbeing. BMC Public Health. 1266. [CrossRef]

- Meng H, Tang X, Qiao J, Wang H. Unlocking resilience: How physical literacy impacts psychological well-being among quarantined researchers. Healthcare. 2972. [CrossRef]

- Caldwell HAT, Di Cristofaro NA, Cairney J, Bray SR, MacDonald MJ, Timmons BW. Physical literacy, physical activity, and health indicators in school-age children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 5367. [CrossRef]

- Ioan MR, Oravitan M. Systematic review of the impact of physical activity on depression and anxiety symptoms. J Phys Educ Hum Mov. [CrossRef]

- Saneei P, Esmaillzadeh A, Keshteli AH, Roohafza HR, Afshar H, Feizi A, et al. Combined healthy lifestyle is inversely associated with psychological disorders among adults. PLoS One. 0146. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. 1984.

- Elsner F, Strassner C. Individual resilience—Recent elaborations on the impact of diet, physical activity and sleep. Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Liu R, Menhas R, Saqib ZA. Does physical activity influence health behavior, mental health, and psychological resilience under the moderating role of quality of life? Front Psychol. [CrossRef]

- Ruf A, Ahrens KF, Gruber JR, Neumann RJ, Kollmann B, Kalisch R, et al. Move past adversity or bite through it? Diet quality, physical activity, and sedentary behavior in relation to resilience. Am Psychol. [CrossRef]

- Blain DO, Curran T, Standage M. Psychological and behavioral correlates of early adolescents’ physical literacy. 2020;40(1):157–65. J Teach Phys Educ.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Anx

Anx Anx

Anx Str

Str Str

Str Dep

Dep Dep

Dep PL

PL PL

PL

PL

PL

PL

PL

Anx

Anx Str

Str Dep

Dep