Invariance of the Spacetime Interval Shown by Pythagoras

Several authors [

3,

4,

5,

6,

10] have noted the two pairs of orthogonal axes in a Symmetrical Spacetime Diagram (SSD) and the fact that the typical equation for invariance of the spacetime interval

(∆t)2 − (∆x)2 = (∆t′)2

− (∆x′)2

can be rewritten as (∆t)2 + (∆x′)2 = (∆t′)2 + (∆x)2

where the invariance of the spacetime interval is shown by Pythagoras.

In 1962, Brehme [

3] described his SSD.

“which needs neither the concept of imaginary numbers nor the use of scale changes….In order to use only Euclidian geometry, the equation

is written with the terms rearranged:

The equation implies that if (x, ct′) are made the rectangular coordinates of one coordinate system and (x′, ct) the rectangular coordinates of another system rotated with respect to the first: the usual orthogonal transformation from one to the other will be the Lorenz transformation.”

In 1968, Sears and Brehme [

4] referred to the interval L between two events in their SSD, the “Lorenz diagram”

“Because of the orthogonality of the (x

A, t

B) axes and the (x

B, t

A) axes, the lengths ∆x

A and c∆t

B form the arms of a right triangle with hypotenuse L, while ∆x

B and c∆t

A form another right triangle with the same hypotenuse. From the Pythagorean theorem, we know that

Since the A and B frames are arbitrary, the quantity c2∆t2 – ∆x2 is the same in all frames of reference, for a given pair of events, and is therefore an invariant quantity. The square of the invariant interval, ∆σ, is defined as ∆σ2 = c2∆t2 – ∆x2 ”

Thus, Brehme, in his later work, simply used the Pythagorean invariance as a route to the squared invariant interval expressed as a difference of squares.

In 1968, Shadowitz [

5] in showing how the Brehme diagram [

3,

4] is developed, wrote

“…we now have X2 + c2t2 = x2 + c2T2. X and cT are the coordinates, for one observer, of the event E; x and ct are the coordinates of the same event for another observer. Thus, here we have the important relation

X2 – c2T2 = x2 – c2t 2

…this equation...is central to everything in special relativity.”

Thus, Shadowitz also saw the Pythagorean invariance just as a route to the invariant interval expressed as a difference of squares.

In 1996, Sartori [

6] stated that:

“An ingenious alternative approach was discovered by Enrique Loedel. Loedel's construction is based on the realization that although (ct)2 + x2 is not invariant in relativity, the quantity (ct)2 – x2 is invariant. The relation

(ct)2 – x2 = (ct′)2 – (x′)2 (5.12)

which expresses that invariance, can be trivially rewritten as

(ct)2 + (x′)2 = (ct′)2 + x2 (5.13)

Equation (5.13) is formally analogous to the equation

x2 + y2 = (x′)2 + (y′)2

which expresses the invariance of the distance …. This analogy led Loedel to construct the diagram ….in which the x axis is perpendicular not to the ct axis but to the ct' axis; the x' and ct axes are likewise perpendicular.”

Examining Loedel’s 1948 article [

7] and the 1949 and 1955 books [

8,

9], while he refers to the orthogonal pairs of axes, no reference could be found to the equation

(ct)2 + (x′)2 = (ct′)2 + x2

Thus, Sartori [

6] saw the Pythagorean invariance (his 5.13) as the invariant interval expressed as a difference of squares (his 5.12) “

trivially rewritten”

In 2012, Benedetto at al. [

10] wrote:

“In our opinion …. the simplest way to introduce Loedel diagrams is through reducing Lorentz transformations, which relate two inertial reference frames, to a simple rotation of the axes through a real angle. The peculiarity of this rotation is the mix between the axes of the two systems: actually it is not a rotation of the (ct, x) frame with respect to the (ct′, x′) frame, but the rotation of (ct′, x) with respect to (ct, x′)”

Benedetto’s diagram showed the angle φ between the ct and ct′ axes. He continued:

“Lorenz transformations are…. ct′ = ct cos φ − x′ sin φ

x = ct sin φ + x′cos φ

The matrix represents, as is well known, a standard clockwise rotation

of the real angle φ. So the Lorentz transformations have been expressed in terms of a rotation of the system (ct′, x) of an angle φ with respect to (ct, x′) frame.”

In summary, in 1962 Brehme [

3] identified the invariance by Pythagoras as a rotation of one orthogonal coordinate system with respect to another. In 1968, Sears and Brehme [

4] noted this, mainly as a route to expressing the invariant interval as a difference of squares. Shadowitz [

5] and Sartori [

6] had essentially the same approach. In 2012 Benedetto et al [

10] described the clockwise rotational matrix related to the orthogonal (ct′, x) axes. However, they did not describe how the (ct, x′) axes symmetrically rotate

anticlockwise resulting in the mirror-image rotation that has been described in the SRRM.

Interestingly, while the above authors have described the calculation of the invariant spacetime interval using Pythagoras with varying degrees of detail and interest, none of them have suggested that spacetime in special relativity could be fundamentally Euclidian.

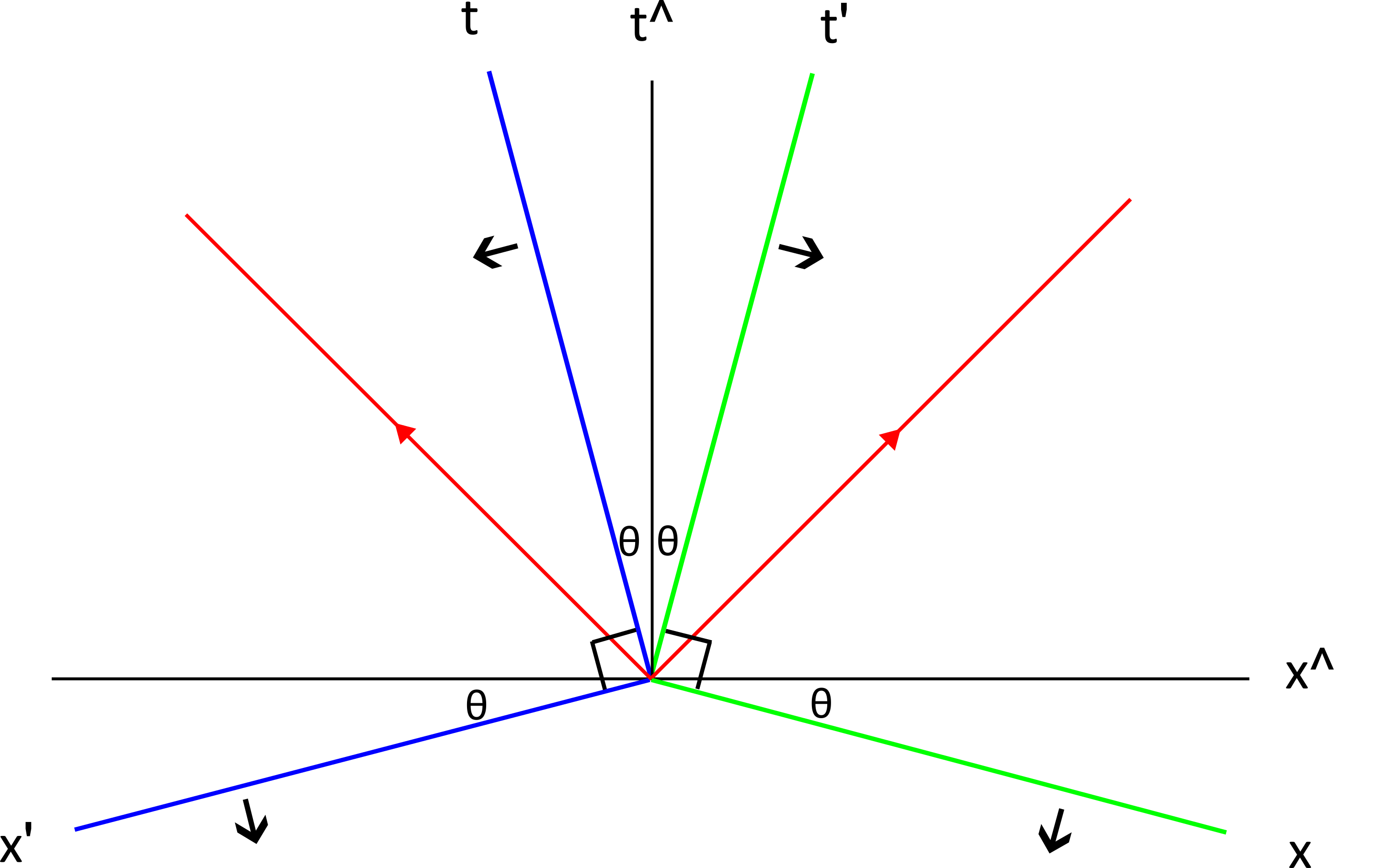

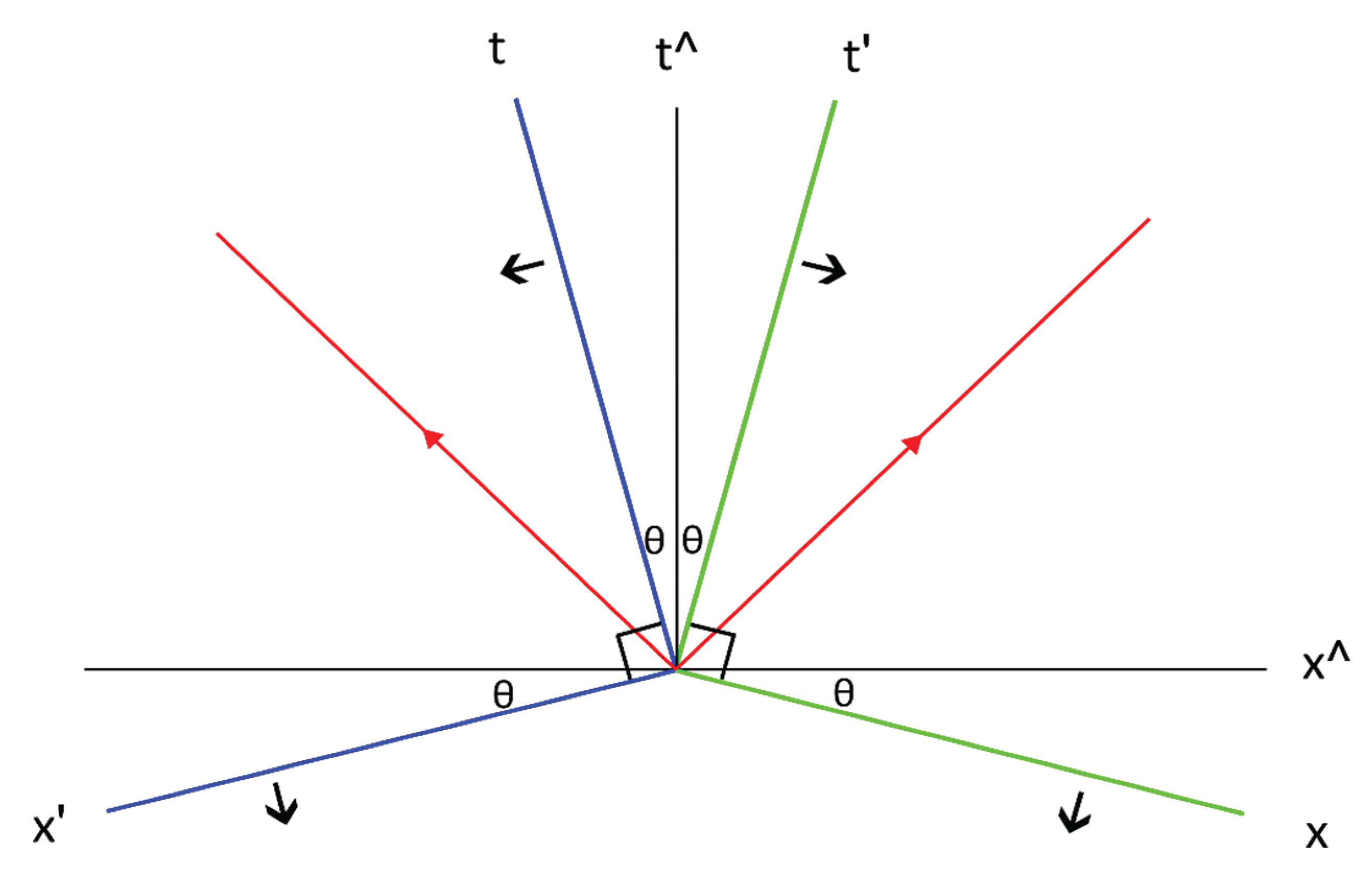

Development of the SRRM

In developing the SRRM the main aim is to be consistent with the Principle of Relativity and display, graphically, the symmetry of the relative motion.

Gruner [

11], in his symmetrical spacetime diagram, identified that there are pairs of orthogonal axes (x, t′) and (x′, t).

Brehme interpreted the two pairs of orthogonal axes in a symmetrical spacetime diagram as two coordinate systems and showed the invariance of the spacetime interval between those coordinate systems by Pythagoras.

The elegance of the algebra and geometry in what has now been called the SRRM leads to the conclusion that the SOCS (x, t′) and (x′, t) are fundamental in relative motion.

The SRRM is an accurate geometrical model of the algebra of special relativity. The geometry of the SRRM reveals the mirror image rotation of the SOCS that is consistent with the algebra.

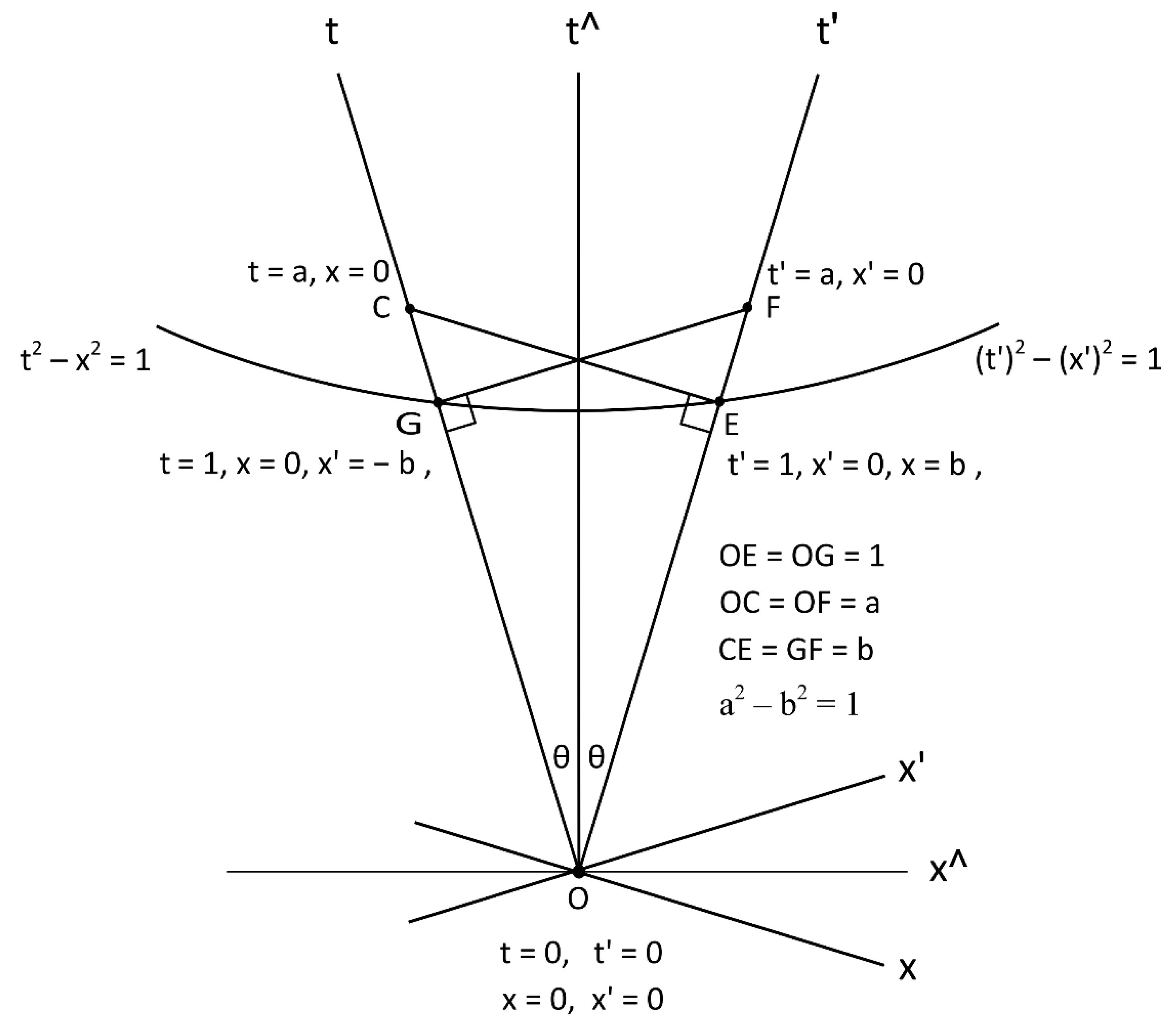

The equation t

2 – x

2 = 1 is fully explained by the right-angle triangles OCE and OGF of the SRRM in

Figure 1. No additional manipulation is needed to progress the mathematics.

Thus, in the SRRM, spacetime in special relativity is entirely explained by Euclidian geometry.

In view of this, in the transformation between the two SOCS (x, t′) and (x′, t), the fundamental equation of the invariant interval is (∆t)2 + (∆x′)2 = (∆t′)2 + (∆x)2.

The Definition of Velocity

The power of the simple and symmetrical transformation equations of the SRRM is shown as they describe the pair of SOCS that rotate as relative velocity increases.

It is surprising that Brehme, after identifying the pairs of orthogonal coordinate systems [

3], appeared to lose interest in them [

4]. It is more surprising that no-one subsequently except Benedetto et al. [

10] have shown any interest in the SOCS. Perhaps, they have seen no fundamental significance in a combination of (x, t′) or (x′, t).

It has been shown in this article how important symmetry is in the understanding of special relativity. It would be an unequal balance if the fundamental measure of relative motion between two inertial bodies were to use both distance and time from the coordinate system of only one of the inertial observers.

The Galilean transformation is:

x′ = x – (velocity) x (universal time)

or x = x′ + (velocity) x (universal time)

The related transformation equations of the SRRM are:

x′ = ax – bt

x = ax′ + bt′

Thus, the velocity term, b, in the SRRM can simply replace the Galilean velocity term when a=1, as it is at low velocities where the Galilean transformation applies.

In view of the significance of the combination of (x, t′) or (x′, t) in the SOCS, the consideration of symmetry and the similarity to the Galilean transformation, there is good evidence to conclude that the velocity terms in the SRRM,

b = x/t′

or – b = x′/t

are the fundamental measures of velocity.