Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

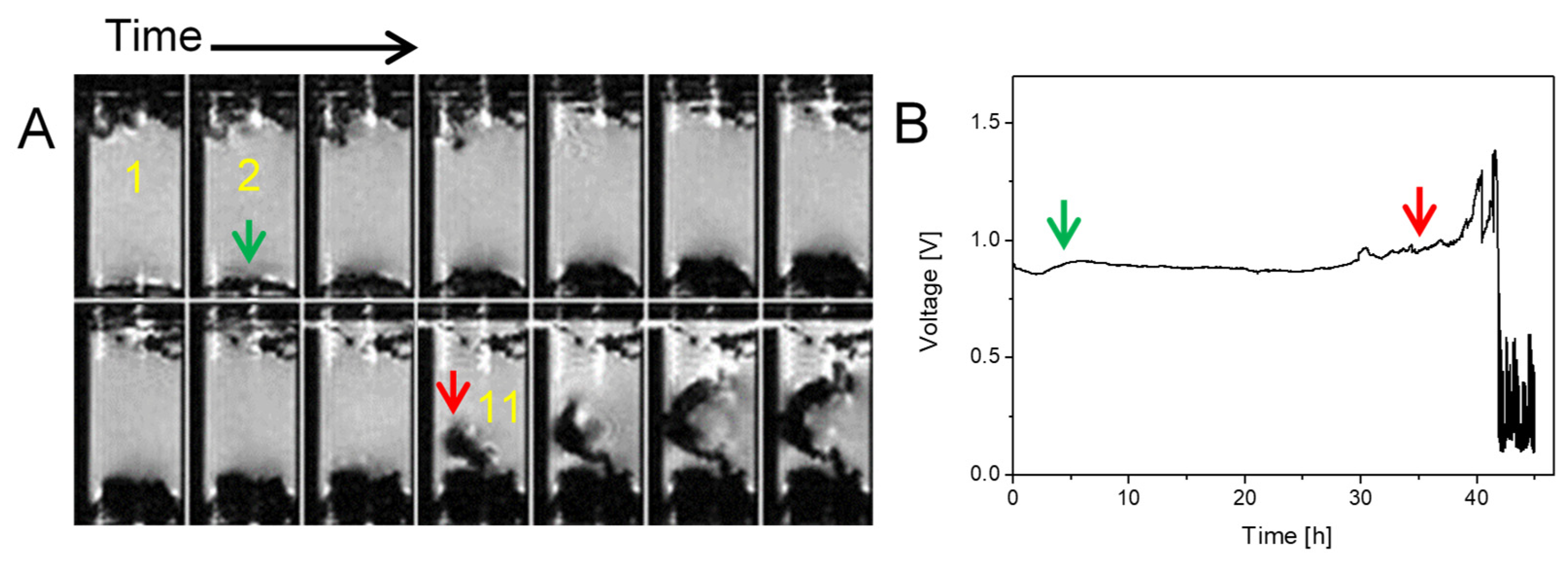

2.1. Sand’s Time

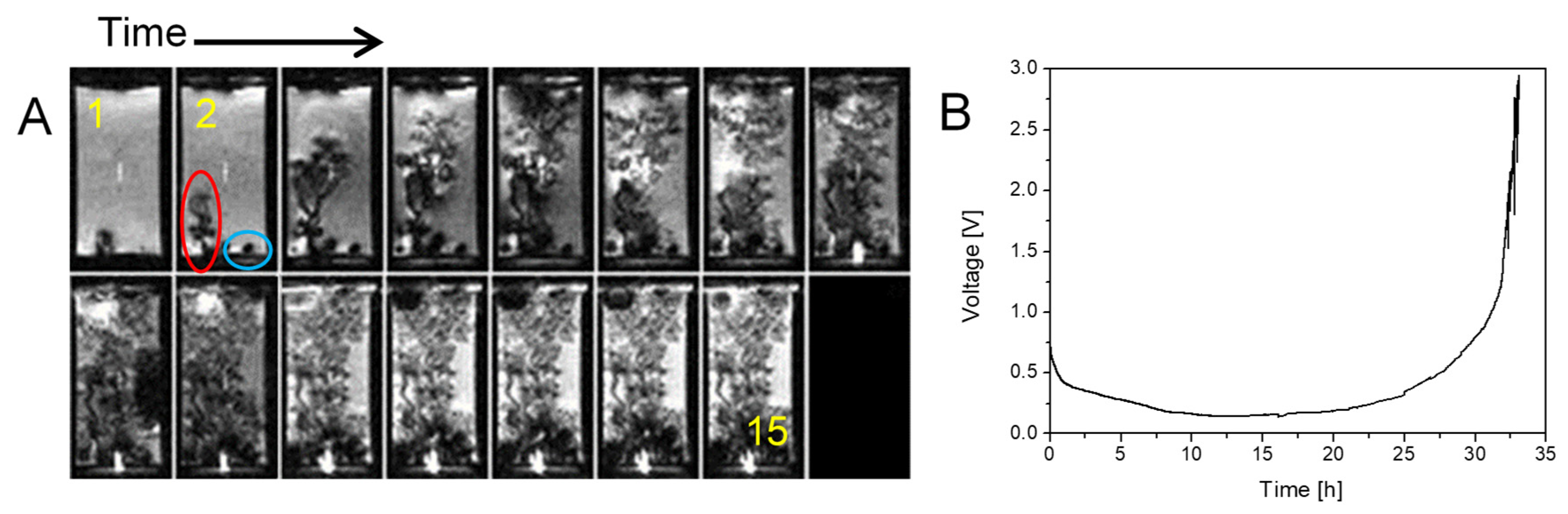

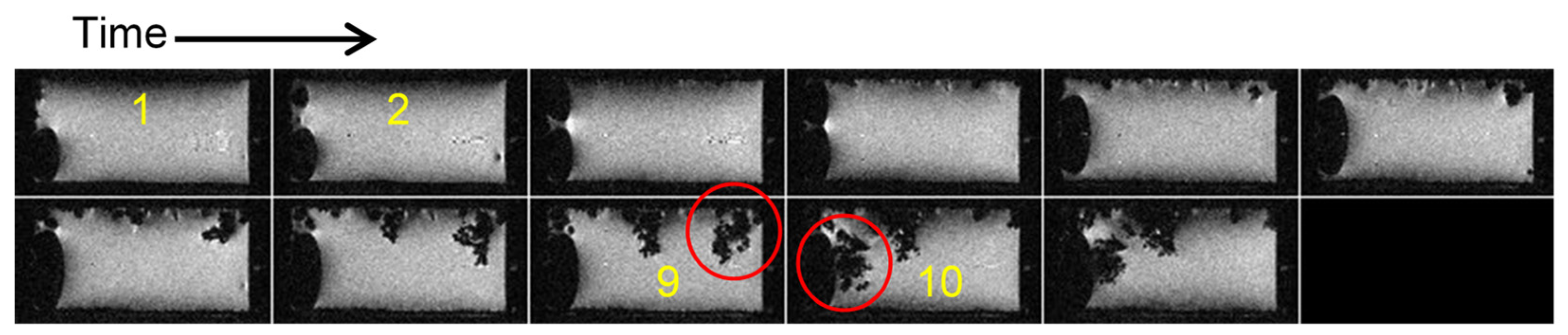

2.2. Transition from Mossy to Dendritic Structure

2.3. Simultaneous Presence of Small Dense and Thin Filamentous Dendrites

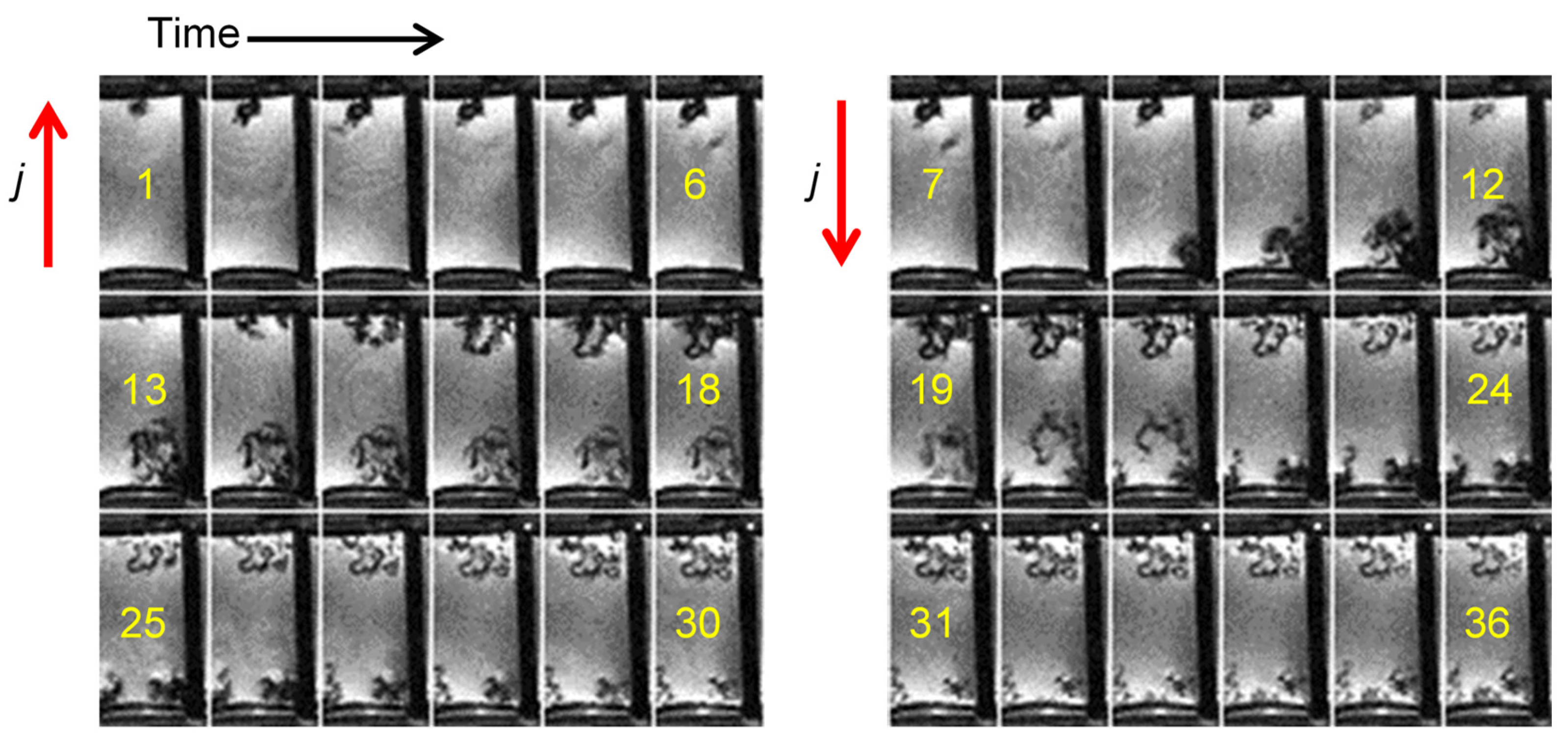

2.4. Current Cycling and the Formation and Breakdown of Whiskers

2.5. Dendrites with Arborescent Structure

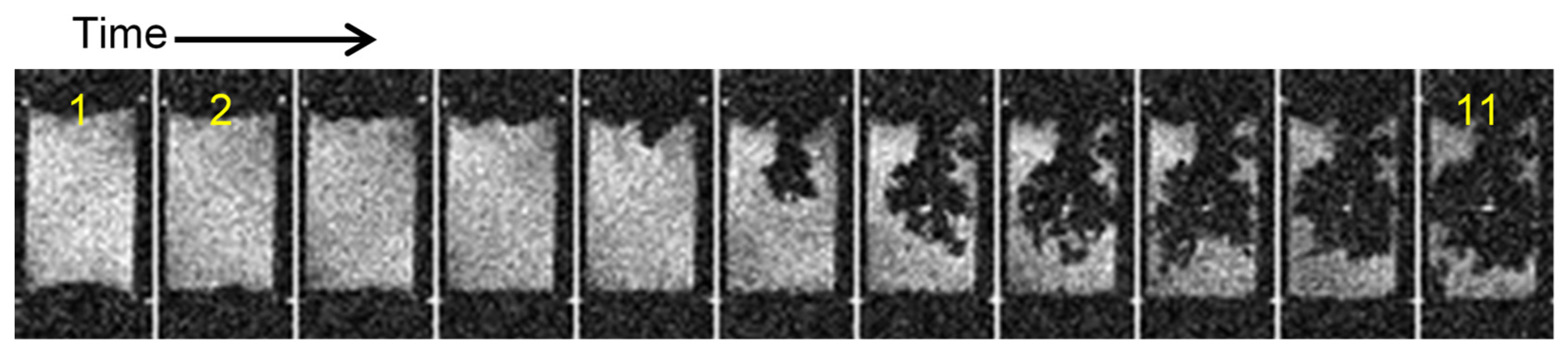

2.6. Dead Lithium

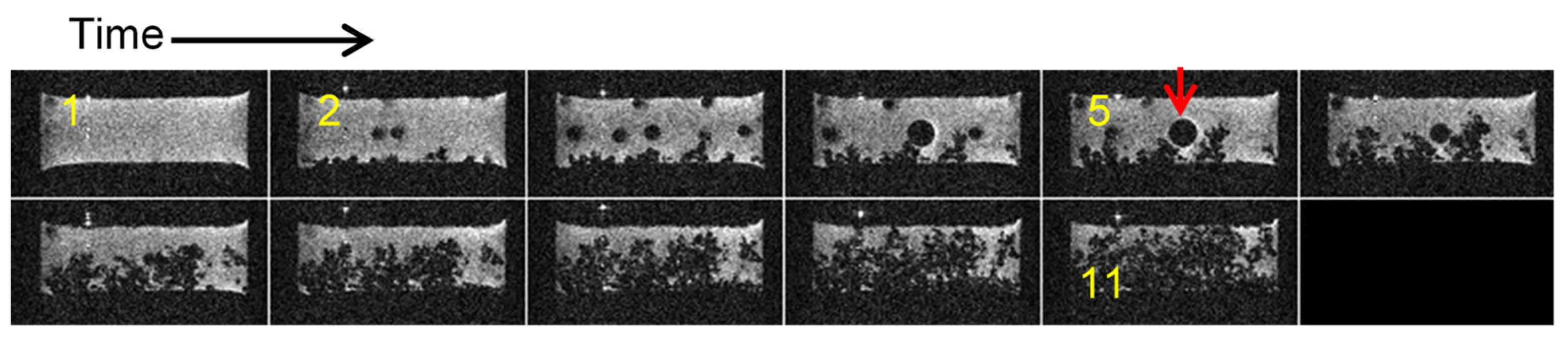

2.7. Gas Bubbles

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

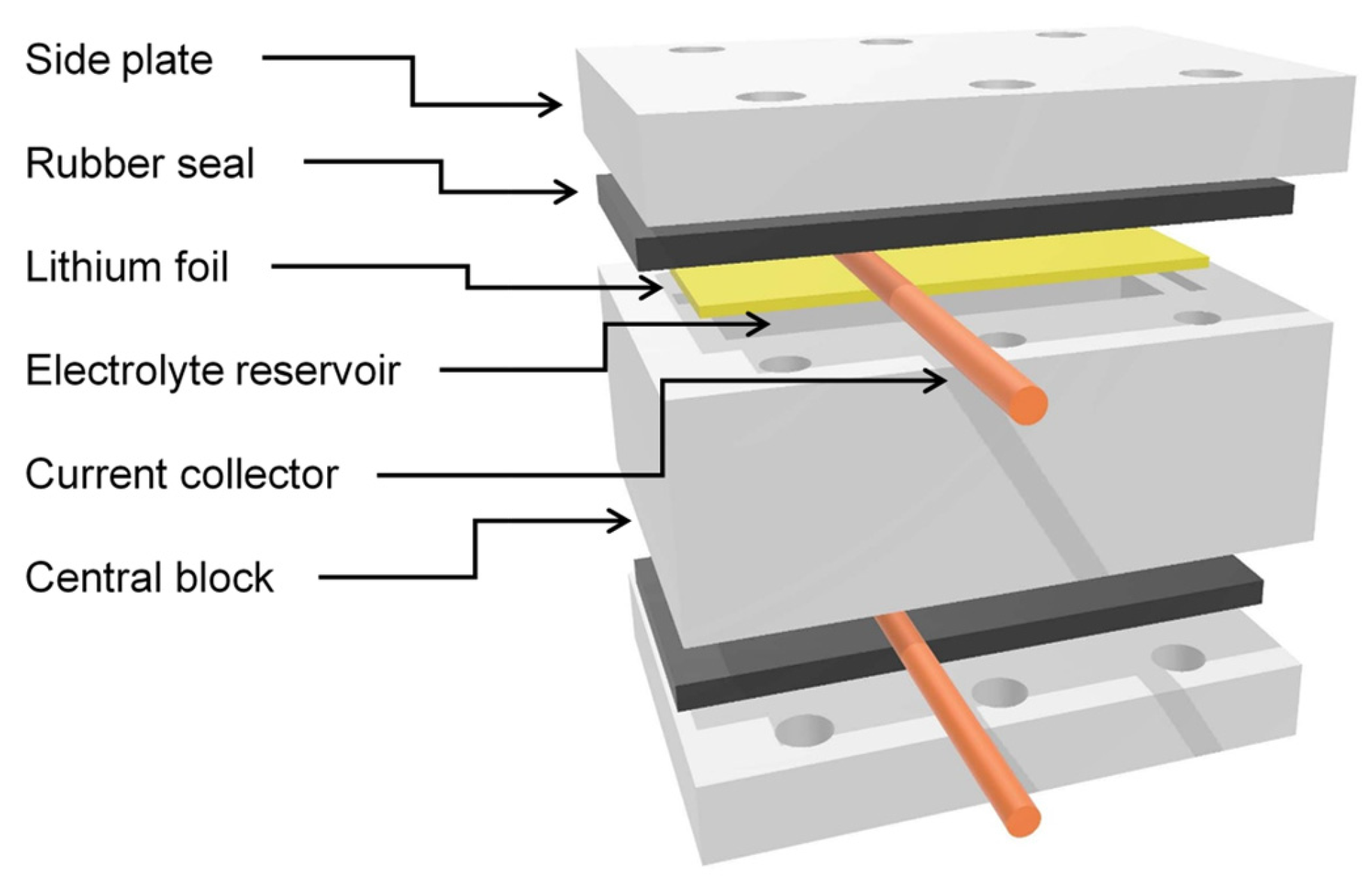

2.1. Lithium Symmetric Cell

2.2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNC | Computer numerical control |

| DMC | Dimethyl carbonate |

| EC | Ethylene carbonate |

| MR | Magnetic resonance |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MRM | Magnetic resonance microscopy |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| RARE | Rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement |

| SE | Spin echo |

| SEI | Solid electrolyte interphase |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| µCT | Computed tomography microscopy |

References

- Tarascon, J.M.; Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 2001, 414, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foroozan, T.; Sharifi-Asl, S.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R. Mechanistic understanding of Li dendrites growth by imaging techniques. Journal of Power Sources 2020, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.H.; Shen, D.Y.; Zhu, J.; Duan, X.D. Erecting Stable Lithium Metal Batteries: Comprehensive Review and Future Prospects. Advanced Functional Materials 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittingham, M.S. Electrical Energy-Storage and Intercalation Chemistry. Science 1976, 192, 1126–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cheng, X.-B.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, R.; Wang, G.; Chen, L.-Q.; Liu, Q.-B.; Huang, J.-Q.; Zhang, Q. Recent advances in understanding dendrite growth on alkali metal anodes. EnergyChem 2019, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazalviel, J.N. Electrochemical Aspects of the Generation of Ramified Metallic Electrodeposits. Physical Review A 1990, 42, 7355–7367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.Z.; Wang, A.X.; Liu, S.; Li, G.J.; Liang, F.; Yang, Y.W.; Liu, X.J.; Luo, J.Y. Controlling Nucleation in Lithium Metal Anodes. Small 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushima, A.; So, K.P.; Su, C.; Bai, P.; Kuriyama, N.; Maebashi, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Bazant, M.Z.; Li, J. Liquid cell transmission electron microscopy observation of lithium metal growth and dissolution: Root growth, dead lithium and lithium flotsams. Nano Energy 2017, 32, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaki, J.; Tobishima, S.; Hayashi, K.; Saito, K.; Nemoto, Y.; Arakawa, M. A consideration of the morphology of electrochemically deposited lithium in an organic electrolyte. Journal of Power Sources 1998, 74, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, H.W.; Liang, L.Y.; Liu, Z.; Qi, Y.; Lu, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, L.Q. Modulation of dendritic patterns during electrodeposition: A nonlinear phase-field model. Journal of Power Sources 2015, 300, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurkiv, V.; Foroozan, T.; Ramasubramanian, A.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R.; Mashayek, F. Phase-field modeling of solid electrolyte interface (SEI) influence on Li dendritic behavior. Electrochimica Acta 2018, 265, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayers, M.Z.; Kaminski, J.W.; Miller, T.F. Suppression of Dendrite Formation via Pulse Charging in Rechargeable Lithium Metal Batteries. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2012, 116, 26214–26221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, W.T.; Cui, X.Q.; Rojo, T.; Zhang, Q. Towards High-Safe Lithium Metal Anodes: Suppressing Lithium Dendrites via Tuning Surface Energy. Advanced Science 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peklar, R.; Mikac, U.; Sersa, I. Simulation of Dendrite Growth with a Diffusion-Limited Aggregation Model Validated by MRI of a Lithium Symmetric Cell during Charging. Batteries-Basel 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissot, C.; Rosso, M.; Chazalviel, J.N.; Lascaud, S. Dendritic growth mechanisms in lithium/polymer cells. Journal of Power Sources 1999, 81, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachman, M.J.; Tu, Z.Y.; Choudhury, S.; Archer, L.A.; Kourkoutis, L.F. Cryo-STEM mapping of solid-liquid interfaces and dendrites in lithium-metal batteries. Nature 2018, 560, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Shen, X.; Zhang, Y.T.; Zhong, X.L.; Ju, H.T.; Huang, T.X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.D.; Huang, J.Q. Dead lithium formation in lithium metal batteries: A phase field model. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2022, 71, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissot, C.; Rosso, M.; Chazalviel, J.N.; Baudry, P.; Lascaud, S. In situ study of dendritic growth in lithium/PEO-salt/lithium cells. Electrochimica Acta 1998, 43, 1569–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissot, C.; Rosso, M.; Chazalviel, J.N.; Lascaud, S. Concentration measurements in lithium/polymer-electrolyte/lithium cells during cycling. Journal of Power Sources 2001, 94, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.X.; Xing, Y.J.; Pecht, M.G. In-situ Observations of Lithium Dendrite Growth. Ieee Access 2018, 6, 8387–8393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Li, J.; Brushett, F.R.; Bazant, M.Z. Transition of lithium growth mechanisms in liquid electrolytes. Energ Environ Sci 2016, 9, 3221–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.H.; Assegie, A.A.; Huang, C.J.; Lin, M.H.; Tripathi, A.M.; Wang, C.C.; Tang, M.T.; Song, Y.F.; Su, W.N.; Hwang, B.J. Visualization of Lithium Plating and Stripping via in Transmission X-ray Microscopy. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2017, 121, 7761–7766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peklar, R.; Mikac, U.; Sersa, I. The Effect of Battery Configuration on Dendritic Growth: A Magnetic Resonance Microscopy Study on Symmetric Lithium Cells. Batteries-Basel 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilott, A.J.; Mohammadi, M.; Chang, H.J.; Grey, C.P.; Jerschow, A. Real-time 3D imaging of microstructure growth in battery cells using indirect MRI. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016, 113, 10779–10784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Ilott, A.J.; Trease, N.M.; Mohammadi, M.; Jerschow, A.; Grey, C.P. Correlating Microstructural Lithium Metal Growth with Electrolyte Salt Depletion in Lithium Batteries Using Li MRI. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2015, 137, 15209–15216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosso, M.; Gobron, T.; Brissot, C.; Chazalviel, J.N.; Lascaud, S. Onset of dendritic growth in lithium/polymer cells. Journal of Power Sources 2001, 97-8, 804–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyssot, A.; Belhomme, C.; Bouchet, R.; Rosso, M.; Lascaud, S.; Armand, M. Inter-electrode in situ concentration cartography in lithium/polymer electrolyte/lithium cells. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 2005, 584, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.S.; Tang, W.; Jung, I.D.; Phua, K.C.; Adams, S.; Lee, S.W.; Zheng, G.W. Insights into morphological evolution and cycling behaviour of lithium metal anode under mechanical pressure. Nano Energy 2018, 50, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Ye, Y.S.; Chen, N.; Huang, Y.X.; Li, L.; Wu, F.; Chen, R.J. Development and Challenges of Functional Electrolytes for High-Performance Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Advanced Functional Materials 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, Y.L.; Ren, X.D.; Cao, R.G.; Cai, W.B.; Jiao, S.H. Advanced Liquid Electrolytes for Rechargeable Li Metal Batteries. Advanced Functional Materials 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Xue, X.L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.X.; Bresser, D.; Liu, X.; Chen, M.H.; Passerini, S. Achieving stable lithium metal anode via constructing lithiophilicity gradient and regulating Li3N-rich SEI. Nano Energy 2025, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Park, J.Y.; Huh, S.H.; Yu, S.H.; Kwak, J.H.; Park, J.; Lim, H.D.; Ahn, D.J.; Jin, H.J.; Lim, H.K.; et al. High-Power and Large-Area Anodes for Safe Lithium-Metal Batteries. Small 2024, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.C.; Liu, Y.Y.; Liang, Z.; Lee, H.W.; Sun, J.; Wang, H.T.; Yan, K.; Xie, J.; Cui, Y. Layered reduced graphene oxide with nanoscale interlayer gaps as a stable host for lithium metal anodes. Nature Nanotechnology 2016, 11, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.Y.; Lee, S.W.; Liang, Z.; Lee, H.W.; Yan, K.; Yao, H.B.; Wang, H.T.; Li, W.Y.; Chu, S.; Cui, Y. Interconnected hollow carbon nanospheres for stable lithium metal anodes. Nature Nanotechnology 2014, 9, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.X.; Odstrcil, R.; Liu, J.; Zhong, W.H. Protein-modified SEI formation and evolution in Li metal batteries. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2022, 73, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G.; Dieckhöfer, S.; Schuhmann, W.; Ventosa, E. Exceeding 6500 cycles for LiFePO/Li metal batteries through understanding pulsed charging protocols. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2018, 6, 4746–4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sersa, I.; Mikac, U. A study of MR signal reception from a model for a battery cell. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2018, 294, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, M.M. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Electrochemical Cells Containing Bulk Metal. Chemphyschem 2014, 15, 1731–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krachkovskiy, S.A.; Bazak, J.D.; Werhun, P.; Balcom, B.J.; Halalay, I.C.; Goward, G.R. Visualization of Steady-State Ionic Concentration Profiles Formed in Electrolytes during Li-Ion Battery Operation and Determination of Mass-Transport Properties by Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2016, 138, 7992–7999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klett, M.; Giesecke, M.; Nyman, A.; Hallberg, F.; Lindström, R.W.; Lindbergh, G.; Furó, I. Quantifying Mass Transport during Polarization in a Li Ion Battery Electrolyte by in Situ Li NMR Imaging. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2012, 134, 14654–14657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, S.; Trease, N.M.; Chang, H.J.; Du, L.S.; Grey, C.P.; Jerschow, A. Li MRI of Li batteries reveals location of microstructural lithium. Nature Materials 2012, 11, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecher, O.; Carretero-González, J.; Griffith, K.J.; Grey, C.P. Materials’ Methods: NMR in Battery Research. Chemistry of Materials 2017, 29, 213–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Trease, N.M.; Ilott, A.J.; Zeng, D.L.; Du, L.S.; Jerschow, A.; Grey, C.P. Investigating Li Microstructure Formation on Li Anodes for Lithium Batteries by in Situ Li/Li NMR and SEM. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2015, 119, 16443–16451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilott, A.J.; Chandrashekar, S.; Kloeckner, A.; Chang, H.J.; Trease, N.M.; Grey, C.P.; Greengard, L.; Jerschow, A. Visualizing skin effects in conductors with MRI: Li MRI experiments and calculations. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2014, 245, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sand, H.J.S. On the concentration at the electrodes in a solution, with special reference to the liberation of hydrogen by electrolysis of a mixture of copper sulphate and sulphuric acid. Philosophical Magazine 1901, 1, 45–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.M.; Doswell, C.L.; Pavlovskaya, G.E.; Chen, L.; Kishore, B.; Au, H.; Alptekin, H.; Kendrick, E.; Titirici, M.M.; Meersmann, T.; et al. Operando visualisation of battery chemistry in a sodium-ion battery by Na magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Commun 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkert, K.; Mandin, P. Fundamentals and future applications of electrochemical energy conversion in space. Npj Microgravity 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maraschky, A.; Akolkar, R. Mechanism Explaining the Onset Time of Dendritic Lithium Electrodeposition via Considerations of the Li Transport within the Solid Electrolyte Interphase. J Electrochem Soc 2018, 165, D696–D703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Dong, H.B.; Yang, R.X.; He, H.Z.; He, G.J.; Cegla, F. Suppression of dendrite formation via ultrasonic stimulation. Electrochem Commun 2024, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| j [mA/cm2] | tS [h] |

|---|---|

| 0.5 | 38.2 |

| 1 | 9.6 |

| 1.5 | 4.2 |

| 2.5 | 1.5 |

| Figure | Imaging sequence |

FOV [mm3] |

matrix | TE/iTE [ms] |

TR [ms] |

NEX | RARE factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D SE | 24×12×6 | 128×64×32 | 22 | 2000 | 1 | / | |

| 3D SE | 24×12×6 | 128×64×32 | 5 | 2000 | 2 | / | |

| 3D RARE | 24×12×6 | 128×64×32 | 5.7 | 2000 | 8 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).