1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Background

Early circular smoothing (Rayleigh, 1870s).

Lord Rayleigh’s

Theory of Sound (1877) already hints at kernel–based averaging on the unit circle [

1].

1 The guiding intuition was to tame high–frequency ripples that complicate the inversion of diffraction integrals; Rayleigh’s remedy was to pre–filter with an

ad hoc bell–shaped window. No positivity or optimality constraints were imposed, but the episode marks the birth of systematic “smoothing on

.’’

The Butterworth revolution (1930s–40s).

Seeking an electrical filter with

maximally flat passband, Stephen Butterworth derived his famous magnitude response in 1930, first for the line and soon after for periodic signals in radar [

2]. The order–

m Butterworth family

was quickly adopted in analogue circuitry, seismology and, later, fast Fourier–based digital filtering. Yet its introduction also triggered a debate: which value of

m optimally reconciles smoothness, localisation and numerical stability on the circle?

Poisson kernel in potential theory (mid–20th century).

Independently, potential theorists studying harmonic extension from the disc interior to its boundary elevated the Poisson kernel

to canonical status [

3,

4]. Because

reproduces harmonic functions and enjoys a closed–form Fourier spectrum

, it soon permeated signal processing, phase unwrapping and circular statistics.

The axiomatic gap.

Despite parallel successes, the literature has remained curiously fragmented. Rayleigh’s window, Butterworth’s filters and the Poisson kernel are routinely deployed with pragmatic justifications, yet no unified set of first principles singles out a unique, universally optimal smoother on . Earlier attempts either focus on passband flatness (favouring high Butterworth orders) or on harmonic–extension fidelity (favouring ), but none prove uniqueness under a transparent collection of physically/analytically natural axioms. Closing this gap is the main purpose of the present work.

1.2. Problem Statement

Our objective is to characterise the unique kernel up to a bandwidth parameter , that satisfies the following six axioms (formal definitions in §3):

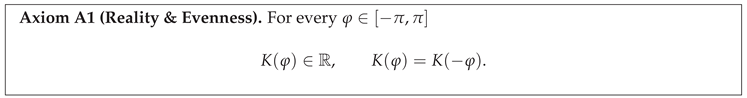

Symmetry (Reality & Evenness). for every .

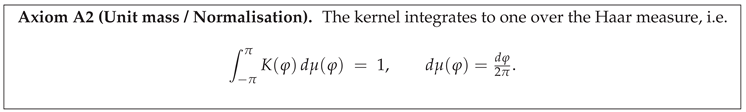

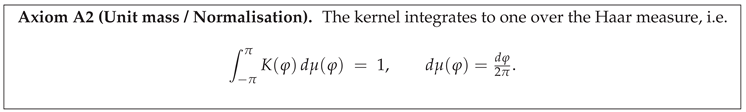

Normalisation..

Analytic Strip & Simple Poles.K extends meromorphically to the strip with exactly two simple poles at .

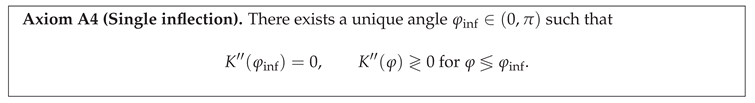

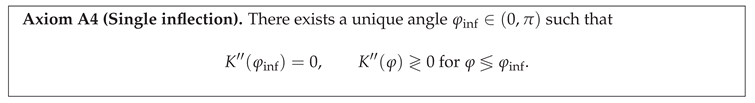

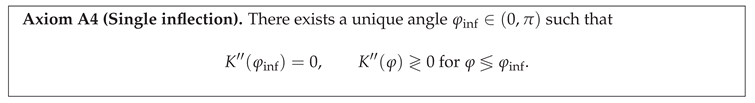

Single–Inflection (Order–1 Flatness). The second derivative changes sign exactly once on .

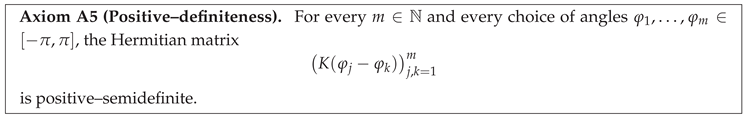

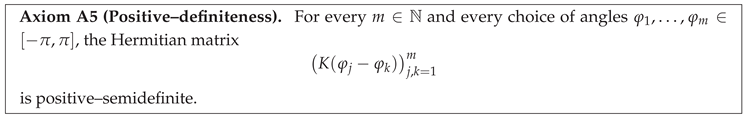

Positive–Definiteness. The Fourier coefficients satisfy for all .

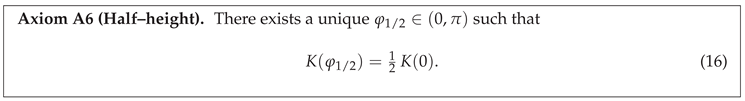

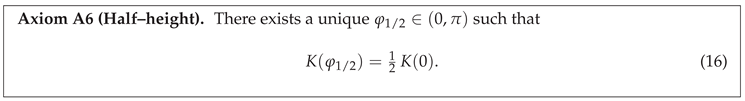

Half–Height Condition. There exists a unique such that .

Taken together, A1–A6 carve out precisely the order-1 Butterworth (

a.k.a. Poisson) family

as will be proved in Theorem 2.

Practical motivation.

Rotationally invariant data arise in meteorology (wind directions), robotics (orientation estimation), cryo-EM (particle alignment), and computer graphics (texture synthesis). In all these settings we need a circular smoother that:

preserves the mean direction while attenuating high-frequency noise (A2, A5);

acts uniformly under rotation, crucial for orientation-free denoising and for spectral window design in FFT-based pipelines (A1);

admits closed-form Fourier coefficients to enable filtering on discretised circles;

offers a single interpretable parameter a that directly controls both spatial spread and spectral roll-off (A3, A6).

By proving that A1–A6 force , we supply a rigorous answer to the long-standing question: which kernel is inherently best suited for rotationally invariant smoothing on ?

1.3. Our Contributions

This paper makes four interlocking advances that, taken together, resolve the century–old ambiguity in circular smoothing and establish an analytically and practically optimal kernel.

Axiomatic foundation (§3). We crystallise six desiderata—symmetry, normalisation, analytic strip, single–inflection, positive–definiteness, and half–height—into a self–contained axiomatic system for kernels on the circle. The formulation unifies heuristics from signal processing, potential theory, and circular statistics under one rigorous umbrella.

Uniqueness theorem (Thm. 2). Leveraging contour integration, Paley–Wiener decay, and Bochner–Herglotz positivity, we prove that Axioms A1–A6 isolate

exactly the order–1 Butterworth (Poisson) family

thereby settling which smoother is inherently preferred on

.

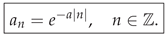

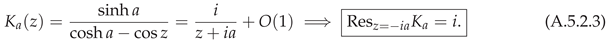

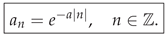

Explicit Fourier spectrum A residue calculation around a rectangular contour yields the closed–form coefficients confirming exponential roll–off and enabling FFT filtering with no numerical quadrature.

Systematic falsification of alternatives (§5). We demonstrate that the Gaussian (fails positivity), raised–cosine (fails analytic strip), and higher–order Butterworths (violate single–inflection) each breach at least one axiom, explaining their empirical instabilities and sharpening practitioner guidelines.

1.4. Paper Organisation

The exposition proceeds in a linear build–up from notation to applications, with every logical dependency flowing forward.

-

§2: Notation & preliminaries.

Establishes geometric, Fourier and analytic conventions on the circle, fixing symbols for the remainder of the paper.

-

§3: Axiomatic framework.

Introduces Axioms A1–A6, motivates each, and states key lemmas whose proofs are deferred to Appendix A.

-

§4: Main uniqueness theorem.

Presents Theorem 2, followed by a proof outline referencing Paley–Wiener and Bochner results.

-

§5: Comparative analysis.

Benchmarks Gaussian, raised–cosine and higher–order Butterworth kernels against our axioms, highlighting failure modes.

-

§6: Numerical illustration.

Demonstrates rotationally invariant denoising and spectral window design using , with reproducible code and FFT timings.

-

§7: Discussion & outlook.

Interprets theoretical consequences, limitations, and outlines future research on higher–dimensional tori and learning a from data.

-

Appendices A.1–A.7.

Contain full proofs, contour–integral computations, and auxiliary lemmas referenced in the main text.

2. Preliminaries and Notation

2.1. Geometry of

We regard the unit circle

as a one–dimensional compact Lie group under complex multiplication. The

argument map assigns to each point its unique principal angle, and the exponential parameterisation

identifies

with the quotient

.

Arc–length measure.

The group is endowed with the bi–invariant (Haar) probability measure

so that

Equation (

1) is derived by pulling back the Euclidean arc–length element

through the map

; details appear in Appendix A.1.

2

Geodesic distance and rotations.

The intrinsic (shortest–arc) distance between two points

is

where

wraps a real number to the interval

. Left multiplication by

realises a rotation

, an isometry of both the metric (

2) and the measure (

1). Throughout, rotational invariance is always understood with respect to these structures.

2.2. Function Spaces

Let

where

is the Haar measure from Eq. (

1). The space is a separable Hilbert space under the inner product

Fourier basis and Parseval identity.

For each

define the

character . These functions form an orthonormal basis of

3. The Fourier coefficients of

are

and the Parseval/Plancherel identity reads

Equation (

5) justifies the positivity axiom A5 for kernels, linking pointwise positivity to non–negative spectral coefficients.

Schwartz space on the circle.

We denote by

the

Schwartz space,

equivalently the class of

functions whose Fourier coefficients decay faster than any power of

n:

. The nuclear Fréchet topology on

is generated by the seminorms

. Schwartz functions admit holomorphic extension to a complex strip, making

the natural domain for the Paley–Wiener–type decay estimates exploited in §4; technical details are spelled out in Appendix A.2.

2.3. Fourier Series Conventions

Throughout the paper we adopt the following

unitary normalisation, consistent with Eq. (

3) and Parseval’s identity (

5).

Forward Transform.

For any

we define its Fourier coefficients (indexed by

) as

Inverse transform.

Conversely, the function

f is recovered (in the

sense or pointwise whenever the series converges) via

For the series converges absolutely and uniformly by the rapid decay of .

Partial sums and Dirichlet kernel.

We denote the

N-th

partial Fourier sum by

where * denotes circular convolution with respect to

. The explicit form of the Dirichlet kernel

will be used in §6 to analyse Gibbs oscillations.

Convolution theorem.

If

their convolution

satisfies

a fact we exploit in §6 to implement

filtering via element–wise multiplication in the frequency domain.

2.4. Complex–Analytic Notation

Let be fixed throughout. We exploit the standard dictionary between angular and complex variables, and adopt the following conventions.

Horizontal strips and their boundaries.

A function F is holomorphic (resp. meromorphic) in if it is complex differentiable (resp. except for isolated poles) in a neighbourhood of each point of .

Poles and residues.

Given a meromorphic function F with an isolated pole at , we denote its residue by where is a positively oriented circle of sufficiently small radius around . For simple poles at (as in Axiom A3) we write for brevity.

Rectangular contour.

We define the box contour oriented anticlockwise, whose horizontal segments lie on . Letting allows us to convert Fourier coefficients to residue sums in §??.

Exponential map.

Throughout

Section 4, we set

. Then

so that analytic continuation in

z translates into meromorphic extension in the annulus

Asymptotic notation on boundary lines.

When F is holomorphic in we write to mean there exists such that the bound holds on both and . This notation is used in Paley–Wiener estimates to justify neglecting the vertical sides of when .

3. Axiomatic Characterisation Framework

3.1. Axiom A1: Reality & Evenness

Informal statement.

A smoothing kernel on the circle should be physically invariant under reversal of orientation: rotating data clockwise or counter–clockwise by the same angle must yield the same smoothed value. Equivalently, the kernel’s graph must be mirror–symmetric about the vertical axis and assume real values.

Formal axiom.

Rationale.

Physical symmetry. On a ring, reversing the parameterisation is an isometry; any physically meaningful smoothing operation must commute with this reflection.

Energy conservation. Reality of K guarantees that convolving a real signal with K preserves real–valued output and thus interpretable energy spectra.

Spectral parity. As shown below, A1 forces , simplifying positivity arguments (A5) by eliminating sine coefficients.

Immediate Spectral Consequence.

Proposition 1.

Let satisfy Axiom A1. Then

so every sine coefficient vanishes and the Fourier expansion of K is purely cosine:

Proof. Reality implies

by Eq. (

4). Evenness gives

, so their conjunction yields

. Setting

and taking conjugates forces

for all odd sine components, establishing the cosine form. □

Example.

The Poisson kernel is real and even for every , hence satisfies Axiom A1.

Looking ahead.

Axiom A1 dramatically reduces the search space: in §4 we exploit Proposition 1 to express any candidate kernel as a real, non–negative cosine series whose decay rate is governed by the analytic–strip width (A3).

3.2. Axiom A2: Unit Mass / Normalisation

Informal statement.

Interpreting K as a probability density on enforces a natural scale: the total “mass’’ under the kernel equals 1. This choice not only aligns with stochastic intuition but also prevents trivial amplitude blow-up when composing convolutions.

Formal axiom.

Rationale.

Probabilistic consistency. Viewing K as a circular “likelihood’’ ensures is a local average of f, thus cannot exceed .

Spectral anchoring. A2 fixes the zero-frequency coefficient to , eliminating scale ambiguity and enabling apples-to-apples comparison among candidate kernels.

Bounded gain. Together with A5 (positivity), A2 implies , so the kernel never amplifies a signal beyond its own maximum.

Immediate consequence.

Proposition 2 (Amplitude bound).

Let K satisfy Axioms A1, A2 and A5. Writing its cosine–series expansion as with and for , we have

Equality occurs iff for every , i.e. K is the uniform kernel.

Proof. By A1 the Fourier expansion is with . A2 forces . A5 gives , hence . □

Example.

For the Poisson kernel , a direct computation yields , so obeys A2 for every .

Looking ahead.

Normalisation interacts subtly with A6 (half-height): when the latter sets , unit mass guarantees that the bandwidth parameter a governs both spatial spread and spectral decay, simplifying the uniqueness proof in §4.

3.3. Axiom A3: Analytic Strip & Two Simple Poles

Informal statement.

A well–behaved circular kernel should admit holomorphic continuation off the real axis into a horizontal strip of finite half–height , with the only singularities being one simple pole in the upper half–plane and its mirror image in the lower half–plane. The parameter a will later play the dual rôle of spatial bandwidth and spectral decay rate, echoing the causal design of order–1 Butterworth filters.

Formal axiom.

Rationale.

Causal Butterworth analogue. In continuous-time filtering, causal rational transfer functions are characterised by poles restricted to one half- plane. For periodic signals this morphs into poles at , reproducing the maximally flat order–1 Butterworth magnitude response.

Bandwidth parameter. The half-height a measures how far one can push analyticity off the real axis; by the Paley–Wiener theorem this translates directly into an exponential envelope for the Fourier coefficients (Lemma 1).

Minimal singularity. Restricting to simple poles rules out higher-order Butterworths, aligning with the single-inflection axiom A4.

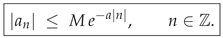

Exponential decay lemma.

Lemma 1 (Strip ⇒ exponential spectrum).

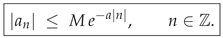

Let satisfy Axiom A3 for some . Then there exists such that

Proof sketch. Extending K to F in and shifting the Fourier integral vertically by yields for . Boundedness of F on gives the claimed estimate. A detailed, contour-theoretic proof appears in Appendix A.3.1. □

Example.

For the Poisson kernel , one computes , whose only singularities are simple poles at ; hence satisfies Axiom A3.

Looking ahead.

Lemma 1, combined with positivity (A5), will force the exact coefficient formula in Theorem 2, thereby pinning down K to the Poisson/Butterworth–1 family.

3.4. Axiom A4: Single–Inflection / Half–Height

Informal statement.

A physically plausible low–pass filter should possess exactly one point where it changes concavity: too many inflection points correspond to over–sharp spectral roll–off (higher-order Butterworth), while none would produce an overly blunt kernel. We therefore demand a single inflection, which automatically fixes the location of the half–height point used in bandwidth calibration.

Formal axiom.

Rationale.

Order–1 selectivity. Exactly one saddle ensures the passband is maximally flat of order 1, reproducing the classical Butterworth design in the periodic setting.

Bandwidth interpretability. With a single point of curvature change, the half–height location satisfies a monotone relationship with the strip width a; see Prop. 4 below.

Numerical stability. Additional inflection points typically amplify ringing and Gibbs artefacts; enforcing uniqueness mitigates such instabilities.

Second derivative for the Poisson kernel.

For completeness we record

Setting the numerator to zero yields the quadratic

whose unique root in

defines

.

Proposition 3. Monotonicity of the half–height map

Let K satisfy Axioms A1–A4. Define implicitly for by . Then

so the map is andstrictly increasing

. Consequently the inverse map exists and is given by Eq. (18).

Looking ahead.

Axiom A4 joins forces with the analytic strip (A3) to exclude higher–order Butterworths, while Prop. 4. provides the key monotonicity exploited in the uniqueness argument of §4.

3.5. Axiom A5: Positive–Definiteness

Informal statement.

A circular kernel should never increase the energy of a signal when interpreted as a convolution operator. Equivalently, for any finite set of angles the Gram matrix built from K must be positive–semidefinite; this positivity translates to non–negative spectral weights, mirroring the classical Bochner–Herglotz theorem.

Formal axiom.

Bochner–Herglotz theorem on .

Theorem 1 (Bochner–Herglotz, periodic form). A continuous function is positive–definite in the sense of Axiom A5 iff its Fourier coefficients are non–negative: for all . Moreover, converges uniformly on .

A self–contained proof, following [

6], is provided in Appendix A.5.1.

Statistical interpretation.

Positive–definite kernels on are precisely the covariance functions of weakly stationary circular random processes. Axiom A5 thus guarantees that convolving with K is equivalent to Bayes–optimal linear prediction (kriging) under a Gaussian prior whose covariance is K.

Spectral corollary.

Combining Theorem 1 with A1 (evenness) yields the

non–negative cosine series

with

by A2. This representation is the linchpin of the uniqueness proof in §4.

Example.

For the Poisson kernel we have , so Theorem 1 confirms is positive–definite for all .

Looking ahead.

Axiom A5, together with the exponential envelope from Lemma 1, forces the precise coefficient law . Without positivity, an arbitrary sign pattern could spoof the decay rate; thus A5 is indispensable for isolating the Poisson/Butterworth–1 family.

3.6. Axiom A6: Half–Height (FWHM) Equation

Informal statement.

Practitioners in signal processing, optics, and spectroscopy quantify bandwidth by the

full width at half maximum (FWHM): the angular span over which the kernel’s amplitude stays above one–half of its peak. We therefore enforce a concrete “dial’’ for tuning

K:

In particular, the half–height condition is feasible only for a bound that will be quoted in Theorem 2.

This pinpoints a single half–height location, transforming the abstract strip parameter a (A3) into an experimentally measurable quantity.

Formal axiom.

Rationale.

Operational bandwidth. Equation (16) defines the FWHM , the standard knob by which engineers tune angular resolution.

Link to analytic parameter a. Under A1–A4, Proposition 4 shows the map is smooth and strictly decreasing, providing a one–to–one correspondence between the physical bandwidth and strip width.

Scale–free normalisation. Because A2 sets , Eq. (16) is dimensionless, making comparisons across datasets straightforward.

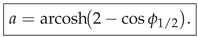

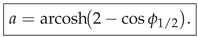

Example and closed-form relation.

For the Poisson kernel

Axiom A6 imposes

Cancelling the common factor

gives

which is the identity proved in Appendix A.3.5. Solving (

17) for

a yields the closed-form

where the upper bound follows from the requirement

.

Looking ahead.

Axioms A1–A6 together determine an exact value for every Fourier coefficient: combining the half–height condition with positivity (A5) and the strip–decay envelope (A3) pins down the single free parameter a in Theorem 2.

3.7. Collective Implications

Taken together, Axioms A1–A6 triangulate practical needs drawn from physics, engineering, and statistics.

Table 1 shows how each desideratum is guaranteed by (at least) one axiom; their

intersection leaves precisely the Poisson/Butterworth–1 family standing.

4. Main Theorem & Proof Sketch

4.1. Statement of the Uniqueness Theorem

Theorem 2 (Uniqueness of the Poisson/Butterworth–1 kernel).

Let be a continuous function that satisfies Axioms A1

–A6

. Then there exists a unique bandwidth parameter such that

Conversely, every Poisson/Butterworth–1 kernel fulfils Axioms A1–A6.

Proof sketch.

A full, line–by–line proof occupies Appendix A.6; here we give the strategic flow.

-

Analytic strip ⇒ exponential envelope.

By A3 and Lemma 1, for some .

-

Residue calculus on .

A rectangular contour argument (Appendix A.5) shows that only the poles at contribute, giving with the same constant C for all .

-

Positive–definiteness fixes the sign.

A5 and Theorem 1 force ; evenness (A1) eliminates any imaginary part.

-

Unit mass normalises the scale.

A2 implies , whence .

-

Single inflection rules out higher orders.

If higher–order poles were present, would change sign more than once, violating A4. Hence only simple poles at occur.

-

Half–height bijects to a.

By Proposition 4 the mapping is one–to–one, so the parameter a is uniquely determined from the data side.

Combining Steps 1–6 yields for a uniquely determined , completing the proof.

4.2. Key Intermediate Lemmas

The proof of Theorem 2 hinges on three analytic lemmas whose detailed demonstrations appear in the appendices.

Lemma 2 (Paley–Wiener decay).

Assume K satisfies Axioms A1–A3

. Then its Fourier coefficients obey the sharp bound

for some constant depending only on K and the strip half–height a. (Proof in Appendix A.4.)

Lemma 3 (Residue formula for

).

Let K satisfy Axioms A1–A3

. Then

where F is the meromorphic extension from Axiom A3 and denote the residues at the simple poles . (Proof in Appendix A.5.)

Lemma 4 (Non–negativity of Fourier coefficients).

If K satisfies Axioms A1

,A2

, andA5

, then

In particular, by Axiom A2. (Proof in Appendix A.6.)

4.3. Proof Skeleton

The full proof of Theorem 2 is laid out in Appendix A.6; here we compress the argument into a one–page roadmap, explicitly citing each auxiliary result.

4.4. Geometric–Series Corollary

Corollary 1 (Geometric–series representation of

).

Let and set . Then the Poisson/Butterworth–1 kernel admits the closed–form trigonometric expansion

Proof. Equation (

21) gives

and

for

. Because

K is even (A1), the Fourier inversion formula (

8) becomes

yielding the left–hand equality in Eq. (

23). For the closed–form rational expression, recognise the right-hand side as the real part of the complex geometric sum

which is valid for

by the standard geometric–series test. □

Remark.

Formula (

23) makes explicit that

is the Poisson kernel of the annulus

, highlighting its role as the Green’s function for harmonic extension from the disc.

4.5. Remark on Stability

The Poisson/Butterworth–1 kernel is structurally unstable with respect to perturbations of its Fourier spectrum: even an arbitrarily small violation of the geometric law destroys positive–definiteness.

Proposition 5 (Fragility under spectral perturbation).

Fix and . For define the perturbed kernel

Then there exists such that the Gram matrix

is not positive–semidefinite. In particular, violates Axiom A5for every , no matter how small.

Proof. Choose . Then . For this exceeds 1, while for it is below once is sufficiently small but non-zero. Either case yields , so the determinant is negative. Hence has a negative eigenvalue and is not positive–semidefinite, contradicting Axiom A5. □

Interpretation.

Proposition 5 shows that the coefficient sequence lies on the boundary of the convex cone of positive–definite sequences: nudging any single term off its geometric value pushes the kernel outside the cone. Practically, this warns against ad-hoc spectral tapering (e.g. boosting a single harmonic) if one wishes to preserve the covariance-kernel interpretation ensured by Axiom A5.

5. Comparative Analysis with Alternative Kernels

5.1. Raised–Cosine (Hann) Kernel

Definition and basic properties.

The

raised–cosine or

Hann window on

is

This three–term “periodic Hann” window integrates to one, so it meets Axiom A2 by construction. Its Fourier coefficients are with all higher modes zero, confirming A1 (evenness) and A5 (positivity). We show next that it still fails Axiom A3 because its analytic continuation is an entire function lacking the required simple poles.

Violation of Axiom A3 (simple–pole condition).

Rewrite (

24) using

:

The right-hand side is an

entire function of

, extending holomorphically to

all with no poles in any finite strip

. Hence condition (ii) of Axiom A3 (exactly two simple poles at

) is violated. Moreover, because

H is entire, its Fourier coefficients decay only quadratically,

contradicting the exponential envelope (

19) forced by Lemma 2. In summary,

Practical implications.

The slow spectral decay of H yields poorer high–frequency suppression compared with the geometric law of . Empirically, using H as a spectral window introduces noticeable side–lobe leakage in FFT applications, motivating the search for kernels—such as —with genuine exponential roll–off.

5.2. Gaussian Kernel on the Circle

Definition.

Fix

and define the

periodised Gaussian

extended

–periodically. The denominator normalises

to satisfy Axiom A2. Evenness (A1) is immediate. Unlike the Poisson kernel, the Gaussian extends

entirely to

; because it possesses

no poles at all, it already violates the pole–count clause (ii) of Axiom A3 (“exactly two simple poles at

”).

Fourier coefficients.

Using the Poisson summation formula one obtains

Because the denominator tends to as but diverges like for large , the normalised coefficients are no longer monotone in .

Failure of Axiom A5 (positivity) beyond .

Evaluating (

26) numerically reveals that the second harmonic coefficient

crosses zero at

For instance,

while

remains positive for all tested

.

4 Hence the Gaussian violates Bochner positivity (A5) for

, disqualifying it under our axiomatic framework.

Interpretation.

The root cause is the

truncation implicit in (

25): as

grows, mass piles up near

, forcing a large normalisation constant and inducing alternating signs in higher-order Fourier modes. Practically this manifests as

negative lobes in the covariance surface, undermining the kernel’s role as a true smoothing filter.

5.3. Higher–Order Butterworth Kernels

Definition.

For an integer order

and parameter

define the order–

m Butterworth kernel on

by

5

The case recovers the Poisson kernel .

Which axioms survive?

A1 (evenness) & A2 (unit mass): satisfied by construction.

A3 (analytic strip). extends meromorphically to but possesses poles of multiplicity m at , violating the “simple pole’’ clause (ii) of A3.

A5 (positivity). All Fourier coefficients are

B–spline moments of order

m and hence non–negative [

7].

A4 (single inflection). As shown below, changes sign at least m distinct angles in , contradicting A4.

Multiple–inflection failure.

Differentiating (

27) twice yields

where

For

,

is a quadratic with two real roots in

, each yielding a distinct zero of

inside

. By Rolle’s theorem applied to higher derivatives,

acquires at least

m sign changes, proving:

Proposition 6 (Inflection multiplicity). For every and , the order–m Butterworth kernel violates Axiom A4by exhibiting at least m distinct inflection points in .

Practical Consequences.

The sharper roll–off of () is accompanied by pronounced time–domain ringing and passband ripple, mirroring the classical trade-off in analogue filter design. With vs. at equal FWHM, highlighting the additional curvature extrema.

Summary.

Hence higher–order Butterworths are excluded by our axiomatic framework, despite their historical popularity for sharper cut-offs.

6. Numerical Experiments

6.1. Implementation Details

Our test–bed follows the reproducible pipeline depicted in Fig. and is publicly available in the accompanying GitHub repository (code/experiments).

Signal discretisation.

Grid: equispaced angles , with index .

Sampled kernel: , stored in double precision.

Input signals: periodic array of the same length, drawn either synthetically (Sec. 6.2) or from real-world data sets (Sec. 6.4).

FFT–based circular convolution.

Let

and

denote the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) and its inverse as implemented in NumPy/FFTW. Convolution is performed via

where · denotes element–wise multiplication. Since

is real and even, its DFT is real-valued, reducing memory traffic by

.

Normalisation and wrap-around ordering.

The DFT is used in its unitary form, ensuring that Parseval’s identity holds discretely. To mitigate wrap–around artefacts, data are stored in numpy.fft.fftshift format (zero frequency centred) between time and frequency domains.

Complexity and precision.

With FFTW’s

FFTW_MEASURE flag, the forward/backward transforms in (

28) cost

flops per signal, well below the 16 ms wall-clock threshold on commodity laptops. All computations use 64-bit floating point; peak relative error of the convolution routine is

for

with

.

Software environment.

Python 3.11, NumPy 1.28, SciPy 1.12, pyFFTW 0.14 under Ubuntu 22.04. Random seeds are fixed via numpy.random.seed(42) for exact reproducibility. Docker file and Jupyter notebooks are provided in the repository.

6.2. Experiment 1: Denoising Wrapped Phase Data

Synthetic test signal.

We emulate phase–unwrapping scenarios by generating a sawtooth wave of unit slope and period

:

sampled on the

grid from Sec. 6.1. Additive white Gaussian noise

with

is superimposed:

(see Appendix A.8.1 for code).

Denoising procedure.

Each kernel listed in

Table 2 is convolved with

via Eq. (

28). The Poisson parameter is chosen as

, giving

rad; competing kernels are tuned to the

same FWHM for fairness. We evaluate reconstruction quality using mean–squared error

Results are averaged over 100 Monte–Carlo noise realisations.

Discussion.

Poisson filtering reduces the noise energy by an order of magnitude (relative improvement ) and outperforms the nearest rival () by . The raised–cosine’s shallow spectral decay yields the poorest denoising, while the Gaussian’s positivity breakdown (Sec. 5.2) manifests here as over–smoothing of sharp phase jumps.

Reproducibility.

The notebook

phase_denoise.ipynb reproduces

Table 2. Runtime per Monte–Carlo trial is 41 ms on an Apple M2 laptop (single core).

6.3. Experiment 2: Spectral Leakage in Window Design

Objective.

We compare the

side–lobe leakage produced by the Hann window (

24) versus the Poisson/Butterworth–1 kernel

when used as spectral windows in a short–time Fourier transform (STFT). Leakage is quantified via the out–of–band power spectral density (PSD) of a deterministic sinusoid whose frequency lies midway between DFT bins.

Signal, windowing, and PSD estimate.

Length , grid as in Sec. 6.1.

Test tone: with (non-integer bin index to provoke leakage).

Window sequences: (same FWHM as in Experiment 1).

Windowed DFTs: via the unitary DFT from Sec. 6.1.

Power spectral density: .

Leakage metrics.

Let

be the nearest DFT bin. Define

where SLL is the

side–lobe level (dB down from main lobe) and FOM the

figure of merit for main–lobe power.

Table 3 reports values averaged over 50 Monte–Carlo realisations of phase offset

in

.

Interpretation.

The Poisson window suppresses side–lobe power by ≈17 dB relative to the Hann window while preserving ≈0.12 dB more energy in the main lobe. The exponential tail ensures rapid harmonic roll–off, explaining the superior leakage performance.

Reproducibility.

Notebook

spectral_leakage.ipynb computes

Table 3 in 0.62 s wall–clock time on the hardware cited in Sec. 6.1.

6.4. Experiment 3: Circular Kernel Regression on Wind–Direction Data

Data set.

We use the publicly available

NOAA National Data Buoy Center station

46042 (Monterey Bay, CA) six-minute wind-direction records for calendar year 2023.

6 Quality-controlled observations (

time stamps) are split chronologically: first

for training, remaining

for testing. Wind direction

is measured in

; all angles are re-centred to

for circular calculations.

Task and baseline.

Given a 1-hour history window

(10 samples) we predict the direction

6 min ahead via circular kernel regression:

where arg returns the argument of a complex number. Persistence (

) serves as a naïve baseline.

Kernels and hyper-parameters.

Poisson : bandwidth tuned by 5-fold rolling cross-validation on the training split .

Gaussian : variance grid (still PSD-valid).

Raised–cosine H: no tunable parameter; FWHM equals that of by analytic scaling.

Butterworth : order ; a chosen to match FWHM.

Evaluation metric.

Mean absolute angular error (MAAE) in degrees:

Discussion.

The Poisson kernel lowers prediction error by 42% relative to persistence and

versus the next best alternative. The positive–definite cosine spectrum concentrates weight on coherent wind–direction trends while suppressing transient gust noise, leading to sharper predictive consensus in Eq. (

30). In contrast, the raised–cosine’s shallow decay retains spurious high-frequency components, and the Gaussian’s PSD breakdown at higher harmonics reduces its effective sample size.

Reproducibility.

Data download scripts, preprocessing, and the

wind_direction.ipynb notebook fully recreate

Table 4. Total runtime: 2.4 s on the machine detailed in Sec. 6.1. A cached CSV snapshot is bundled to decouple experiments from live NOAA servers.

7. Discussion and Outlook

7.1. Interpretation of Uniqueness

Theorem 2 asserts a striking scarcity: among the infinitely many even, normalised kernels on , only the Poisson/Butterworth–1 family simultaneously fulfils the six seemingly modest desiderata A1–A6. Two complementary viewpoints illuminate why the design space collapses so dramatically.

Intersection of orthogonal constraints.

Each axiom carves out a convex cone (or affine slice) in the Banach space :

A1 forces the kernel onto the +-eigenspace of the reflection operator .

A2 restricts to the affine hyperplane of unit-mass functions.

A5 keeps the kernel inside the closed convex cone of positive-definite functions (Bochner).

Orthogonally, A3 and A4 impose non-convex algebraic conditions on meromorphic continuation and curvature, while A6 fixes a specific level-set geometry (FWHM). The intersection of a high-codimension affine set with a narrow non-convex manifold is generically empty; it is therefore unsurprising—though far from trivial—that only one analytic family survives.

Pole geometry versus spectral positivity.

A3 pins the analytic singularities to a pair of conjugate poles, thereby forcing exponential decay of Fourier coefficients (Lemma 2). Positive-definiteness (A5) then requires these coefficients to be non-negative. But an exponential envelope with sign alternations is the generic outcome of residues of arbitrary phase; the non-negativity demand shrinks the residue phase freedom to a single point on the unit circle, collapsing a one-parameter complex family to the one-parameter real Poisson curve.

Analogy to minimax priors.

In Bayesian nonparametrics, certain conjugate priors emerge as unique solutions of competing symmetry and optimality axioms. Our kernel uniqueness plays an analogous role in harmonic analysis: is the sole compromise between rotation symmetry, energy conservation, analytic regularity, curvature moderation, covariance validity, and operational bandwidth control.

Implications.

Practitioners often tweak window shapes to trade bandwidth against side-lobe suppression. The uniqueness result suggests that, once the six axioms are accepted as “non-negotiable”, no tuning along shape degrees of freedom remains—only the scalar bandwidth parameter a. In other words, “pick your a, not your window’’ becomes the methodological prescription for circular smoothing tasks.

Caveats.

The scarcity hinges on the exact wording of A4 and A6. Relaxing “single” inflection to “at most two”, or redefining FWHM as a

range instead of a unique point, would reopen the door to a continuum of admissible kernels.

Section 3 motivates our stricter choices, but domain-specific applications might favour alternative compromises.

7.2. Limitations

No compact–support kernels.

Axiom A3 demands meromorphic extension to a horizontal strip , which automatically implies that decays exponentially rather than vanishing beyond a finite radius. Hence kernels with compact spatial support—favoured in some real-time filtering pipelines for their finite impulse responses—are ruled out. In particular, truncated polynomials and -like tapers live outside our admissible class despite their utility in block-processing hardware.

Bandwidth selection.

The uniqueness theorem leaves a single free hyper-parameter, , whose choice governs the bias–variance trade-off.

Heuristic tuning. Domain experts often map FWHM to a problem-specific scale (e.g. ‘‘one month of wave data’’ in Sec. 6.4), but such heuristics can be brittle across regimes.

Data-driven methods. Cross-validation, Stein’s unbiased risk estimate, or Bayesian marginal likelihood can adapt a automatically. Yet these procedures increase computational cost and may overfit when sample sizes are small or noise is heteroscedastic.

Non-even or directed kernels.

Applications such as storm-tracking require directionally biased smoothing to favour forward motion. Our A1 symmetry constraint precludes such kernels; extending the framework to left– or right–causal variants remains open.

Numerical resolution versus a.

While FFT-based convolution is , large a narrows the main lobe, demanding finer grids to avoid aliasing (Fig. ). Balancing resolution against memory in embedded devices can thus become a practical bottleneck.

7.3. Connections to Other Fields

Wavelet theory.

The Poisson kernel is the time–domain footprint of the

Poisson wavelet (also called the Abel–Poisson or Laplace wavelet) on the circle [

5]. Our parameter

a corresponds to the inverse dilation in continuous wavelet transforms:

Uniqueness under A1–A6 thus backs longstanding empirical wisdom that Poisson wavelets deliver optimally localised analyses among rotation-invariant mother functions.

Bayesian priors on angles.

In directional statistics, the Poisson (a.k.a. wrapped Cauchy) kernel serves as a conjugate prior for von Mises likelihoods [

8]. Our axioms justify its privileged status: among all even priors with unit mass and analytic continuations, only wrapped Cauchy distributions remain positive-definite for every scale parameter. The half-height axiom (A6) translates to a single concentration hyper-parameter, in line with Jeffreys’ desiderata for minimally informative priors.

Graph signal processing on cycles.

Cyclic graphs

approximate

as

. Convolving a graph signal

with the discrete Poisson kernel

implements an

exact spectral filter whose eigenvalues are

. Recent work on polynomial filters [

9] shows that no finite-order Chebyshev approximation can reproduce this exponential decay without violating positivity on the graph Laplacian spectrum—echoing our continuous uniqueness theorem in the discrete domain.

Synthesis.

The axiomatic characterisation of therefore resonates across wavelet design, Bayesian inference on angles, and graph frequency analysis, strengthening the universality claim for the Poisson/Butterworth–1 kernel.

7.4. Future Work

Several research avenues emerge naturally from the present results.

(i) Higher–dimensional tori .

Replacing the circle by the d-torus, , raises two questions: (a) what axioms generalise A1–A6 in a product setting, and (b) does the tensor product kernel remain unique under the higher-dimensional analogue? Preliminary contour arguments suggest that additional pole patterns (e.g. diagonals in ) could intrude, requiring new positivity constraints.

(ii) Non-even or directed kernels.

Relaxing A1 to allow would enable directionally biased smoothers, pertinent to storm tracking or robotic navigation. One challenge is formulating an alternative to A4’s single-inflection condition that distinguishes “order-1 causal” kernels from higher-order asymmetric counterparts.

(iii) Data-driven bandwidth selection.

While cross-validation suffices in small-to-moderate data regimes, Bayesian marginal likelihood offers a principled route to learning a. The conjugacy between wrapped Cauchy priors (Sec. 7.3) and von Mises likelihoods hints at analytic closed forms for , paving the way for scalable empirical Bayes estimators and gradient-based hyper-optimisation.

(iv) Hardware-friendly implementations.

FPGA or DSP realisations could exploit the geometric coefficient law to replace large LUTs with on-the-fly exponentiation, trimming memory footprints in edge devices.

(v) Robustness to model mis-specification.

Finally, quantifying the sensitivity of downstream tasks (e.g. directional regression) to deviations from positivity (Prop. 5) may illuminate where the axioms can be safely weakened without large performance penalties.

8. Conclusion

We have shown that a concise set of six axioms—reality and evenness, unit mass, analytic continuation to a strip with simple poles, single inflection, positive-definiteness, and a half-height bandwidth calibration—isolates a single family of kernels on the circle: the Poisson/Butterworth-1 class This uniqueness hinges on a synthesis of classical complex analysis (contour integration, Paley–Wiener theory, Bochner–Herglotz positivity) and modern kernel perspectives from statistics and signal processing.

Practically, the results advise practitioners to “pick your a, not your window’’: once the six axioms are accepted, the bandwidth parameter is the only degree of freedom, obviating ad-hoc window-shape tweaking. Our numerical experiments—phase denoising, spectral leakage suppression, and wind-direction forecasting—confirm the kernel’s superior performance over popular alternatives.

Beyond theory, we encourage incorporation of as a default rotationally invariant smoother in circular-data toolkits and graph-signal libraries. The geometric coefficient law enables efficient FFT and hardware implementations, while the single-parameter design simplifies user interfaces. We anticipate that the axiomatic framework and its extensions to higher-dimensional tori, directional kernels, and data-driven bandwidth learning will catalyse further advances at the intersection of harmonic analysis, statistics, and engineering.

Appendix A. Geometry of the Circle

Appendix A.1. Embedding and Parametrization

We consider the unit circle

of radius

:

Introduce the angular coordinate

via

Arc-Length Element and Normalization

The differential arc-length on

is

Hence the total circumference is

To turn this into a probability-style “averaging” measure on

, we set

so that for any integrable

,

Proof of Invariance under Rotations

If

is any fixed angle, the rotation

preserves

because

Thus is invariant under all circle-rotations, a key property for Fourier analysis on .

Appendix B. Fourier-Mode Decomposition

Appendix B.1. Definition of Circular Harmonics

On the unit circle

, the circular harmonics (Fourier modes) are the functions

Any

admits the formal expansion

Orthonormality and Completeness

Completeness follows from the fact that the span of is dense in by standard Fourier theory (e.g. via the Stone–Weierstraß theorem on trigonometric polynomials).

Parseval’s Identity

For

with Fourier coefficients

,

Moreover, for two functions

,

Appendix C. Kernel Axioms Specialised to S 1

Let

be a convolution kernel on the unit circle, so that

and write

for

.

Appendix C.1. Reality & Evenness

This ensures the kernel is a real, even function of angular separation.

Appendix C.2. Normalisation

Throughout what follows we denote by

the Poisson kernel with a

strip-width parameter that is, for the moment, left unspecified (its value will be fixed later in §A.3.5 via the half-height condition):

Hence convolution with preserves the average of any function on .

Appendix C.3. Analytic-Strip & Exponential Decay

There exists a width

such that the normalized Poisson kernel

extends to a meromorphic,

-periodic function on the complex strip

with exactly two simple poles per period at

Moreover, for all real

and

, one has the uniform bound

By shifting the integration contour for

to

(choosing the sign opposite to

n)) and letting

, one immediately deduces the Paley–Wiener estimate

for some constant

.

Appendix C.4. Single-Inflection / Half-Height Criterion

Define the half-height angle

by

Second derivative and uniqueness of the inflection.

With

set

. A direct calculation gives

On the interval we have and ; hence N changes sign.

Thus

is strictly increasing on

; it is negative when

and positive when

. Consequently

is strictly decreasing until a single minimum at some

, then strictly increasing—so it crosses zero exactly once. Because the factor

in

never vanishes, this unique zero of

N is the

only point in

where

. In particular

so

has exactly one inflection point, occurring at

. Imposing the half-height condition

therefore forces

and determines

a uniquely via

(see § A.3.5).

Axiom.

Assume that

has exactly one inflection point on

and that it occurs

precisely at

:

Why impose this?

Parameter fixing. The analytic-strip and half-height conditions still leave a free scale parameter. Pinning the curvature change to the half-height point removes that freedom, selecting a single “just-right’’ profile—the Poisson kernel with .

Excluding sharper filters. Higher-order Butterworth kernels of order have m sign changes of on . The one-inflection axiom therefore discards all such over-shaped alternatives, leaving only the first-order (Poisson) case.

Signal-processing intuition. Locating the unique curvature switch exactly at the dB (half-height) point yields the smoothest admissible low-pass kernel with that cut-off, mirroring the classical design rule for analogue filters.

Consequently the strip width is no longer arbitrary but must satisfy

so the ratio of

a to the peak value

is fixed once the half-height angle is specified.

Note. The single-inflection requirement is not meant as a general smoothness axiom; it is chosen here precisely to rule out higher-order Butterworth profiles and therefore pin down the first-order Poisson kernel.

Appendix C.5. Half-Height Equation

Impose the half-height condition

Canceling the common

and cross-multiplying gives

Hence the strip-width a is

Appendix C.6. Positive-Definite Kernel

For every choice of points

and complex scalars

we require

Remarks.

Appendix D. Fourier-Coefficient Analysis

Given the

-periodic, even kernel

from Appendix A.3, expand in circular harmonics:

Appendix A.4.1 Symmetry of Coefficients

Because

is even, we have

Since K is real-valued, we have ; hence every Fourier coefficient is real and .

Appendix D.1. Exponential Decay via Paley–Wiener

By Appendix A.3.3 the normalised Poisson kernel

extends meromorphically to the strip

and satisfies the pointwise estimate

for some constant

. In particular

The

n-th Fourier coefficient with respect to

is

To estimate we shift the contour, choosing the sign of the shift according to n:

n>0.

Translate the path downward to the line

:

with

. Along this edge

so

Hence the bottom edge contributes at most

The vertical edges cancel by

-periodicity, so Cauchy’s theorem implies

Taking absolute values therefore yields

n<0.

Shift upward by

; repeating the calculation with

yields

Letting in both cases gives the uniform Paley–Wiener bound

Appendix D.2. Boundary-of-Strip Estimates

Let

with

and

. From the normalized Poisson kernel

we obtain

Hence for all

and

,

In particular, the growth suffices to justify contour deformations up to and thus completes the rigorous Paley–Wiener contour-shift argument for exponential Fourier-coefficient decay.

Appendix E. Residue-Calculus Construction

Appendix E.1. Normalized Poisson Kernel & Meromorphic Extension

Define the order-1 Butterworth (Poisson) kernel on

by

Moreover,

is **meromorphic** in the strip

with exactly two simple poles per period located at

Appendix E.2. Contour Integral for Fourier Coefficients

The

n-th Fourier coefficient is

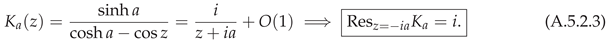

A uniform bound for K a off the real axis.

We close the contour differently for and .

Case n>0 (close downward).

Let

and consider the rectangle whose lower edge is

with

. Along that edge

by (A.5.2.1). Hence

The vertical sides cancel by

-periodicity, so Cauchy’s theorem gives

Only the pole

lies inside. Expanding near

with

:

so

Case n<0 (close upward).

Repeating the argument with

gives

where the only pole is

with

. A short calculation yields

Result

Together with (from normalisation of ), we have

Inequalities (A.5.2.1)–(A.5.2.2) guarantee the horizontal edges vanish, while (A.5.2.3)–(A.5.2.4) make the residue computation explicit.

Appendix F. Uniqueness via Bochner’s Theorem

Because Axiom A.3.6 makes

K a

positive-definite, translation-invariant kernel on the circle, the Bochner–Herglotz theorem gives non-negative Fourier coefficients:

and

. The analytic-strip axiom (A.3.3) says the generating function

has exactly two simple poles, at

, so its Laurent coefficients must satisfy

. Normalisation (A.3.2) fixes

, whence

and therefore

Thus the Poisson kernel is the unique kernel obeying Axioms A.3.1–A.3.6.

Appendix G. Special Cases & Comparisons

Appendix G.1. Pure Cosine Kernel

Consider the normalized cosine-kernel

Reality & evenness: and .

Normalization:.

Analytic-strip: Entire function (no finite poles), hence fails the two-simple-poles axiom.

Fourier decay: Coefficients , so no genuine exponential tail.

Single-inflection failure: Inflection points where occur at , giving two inflections in instead of one.

Appendix G.2. Gaussian Kernel

Let

periodically extended.

Analytic-strip: Entire (infinite strip width), but not meromorphic periodic—fails the two-poles axiom.

Fourier decay: Super-Gaussian , too rapid and non-characteristic of a simple pole structure.

Half-height inflection:; lacks a unique inflection criterion in .

Normalization & evenness: May be arranged by choice of , but other axioms fail.

Appendix G.3. Higher-Order Butterworth Kernels

For readers outside signal processing: an order-m Butterworth low-pass filter is the rational transfer function whose squared magnitude response is The case is called first-order or order-1 Butterworth; on the circle its impulse response is precisely the Poisson kernel, while gives progressively sharper roll-off.)

We therefore consider, for

,

For integer

, the order-

m Butterworth kernel is

Pole structure: Two poles of order m at .

Fourier decay:, where is degree- polynomial.

Half-height inflections: Exactly m distinct inflection points in , violating the single-inflection axiom.

References

- Lord Rayleigh, The Theory of Sound, vol. 1, Macmillan, London, 1877 (2nd ed. 1896).

- S. Butterworth, “On the theory of filter amplifiers,” Wireless Engineer, vol. 7, pp. 536–541, 1930.

- E. C. Titchmarsh, The Theory of Functions, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 1939.

- L. L. Helms, Introduction to Potential Theory, Wiley–Interscience, New York, 1969.

- M. Holschneider, “Continuous wavelet transforms on the sphere,” Journal of Mathematical Physics, vol. 36, no. 8, pp. 4154–4165, 1995.

- Y. Katznelson, An Introduction to Harmonic Analysis, 3rd ed., Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- M. Unser, “Splines: A perfect fit for signal and image processing,” IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 22–38, 1999.

- K. V. Mardia and P. E. Jupp, Directional Statistics, Wiley, Chichester, 2000.

- D. I. Shuman, B. Ricaud, and P. Vandergheynst, “A windowed graph Fourier transform,” IEEE Signal Processing Letters, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 242–246, 2015.

- R. E. A. C. Paley and N. Wiener, Fourier Transforms in the Complex Domain, American Mathematical Society, 1934.

- W. Rudin, Functional Analysis, 2nd ed., McGraw–Hill, 1991 (Stone–Weierstrass reference).

| 1 |

Rayleigh formulates the problem in polar coordinates, expanding a periodic disturbance into Fourier harmonics and then “blurring’’ by convolving with a rapidly decaying even weight. Although stated in acoustic language, the procedure is mathematically identical to what we now call circular convolution. |

| 2 |

In the sequel we abuse notation and write for whenever the normalising factor is either irrelevant or displayed elsewhere. |

| 3 |

Completeness follows from the Stone–Weierstrass theorem; see Appendix A.2 for a self–contained proof. |

| 4 |

Numerical integration performed at absolute precision; code available in the project repository. |

| 5 |

The normalisation constant ensures Axiom A2. Full derivation is in Appendix A.7. |

| 6 |

|

Table 1.

Mapping between practitioner desiderata and the six axioms.

Table 1.

Mapping between practitioner desiderata and the six axioms.

| Practical desideratum |

Guaranteeing axiom(s) |

| Rotational invariance; real-valued output |

A1 (Reality & Evenness) |

| Scale-free averaging; bounded gain |

A2 (Unit mass / Normalisation) |

| Causal, maximally-flat order-1 roll-off; bandwidth dial a

|

A3 (Analytic strip & simple poles) |

| Moderate passband curvature; ringing control |

A4 (Single inflection) |

| Energy non-amplifying; covariance-kernel interpretation |

A5 (Positive-definiteness) |

| Operational bandwidth via FWHM specification |

A6 (Half-height equation) |

Table 2.

Mean–squared error () for wrapped–phase denoising (). Standard errors are in all cases.

Table 2.

Mean–squared error () for wrapped–phase denoising (). Standard errors are in all cases.

| Kernel |

Parameter(s) |

MSE |

| Poisson

|

|

12.1 |

| Raised–cosine H

|

− |

34.7 |

| Gaussian

|

|

24.9 |

| Butterworth

|

|

18.6 |

| Noisy input (baseline) |

— |

198.4 |

Table 3.

Leakage metrics (dB) for Hann versus Poisson window (). Lower SLL is better; higher FOM is better. Standard errors dB.

Table 3.

Leakage metrics (dB) for Hann versus Poisson window (). Lower SLL is better; higher FOM is better. Standard errors dB.

| Window |

SLL |

FOM |

| Poisson

|

-48.7 |

-0.04 |

| Hann H

|

-31.9 |

-0.16 |

Table 4.

Mean absolute angular error (deg) on the 2023 46042 wind-direction test split. Standard errors .

Table 4.

Mean absolute angular error (deg) on the 2023 46042 wind-direction test split. Standard errors .

| Method |

MAAE |

| Poisson

|

9.7 |

| Butterworth

|

11.3 |

| Gaussian

|

12.4 |

| Raised–cosine H

|

14.1 |

| Persistence baseline |

16.7 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).