1. Introduction

Morton's neuroma is a painful condition affecting the common plantar digital nerves of the foot, often associated with tight footwear and repetitive microtrauma [

1]. It is characterized by perineural thickening that causes radiating pain towards the toes or metatarsal pain [

2,

3]. Conventional treatments include orthopedic insoles, corticosteroid injections, and changes in footwear. However, their effectiveness decreases depending on the size of the neuroma and the duration of symptoms [

4,

5]. When conservative options fail, surgical alternatives or minimally invasive procedures like radiofrequency are available.

Traditional surgical approaches have variable success rates and may involve complications, such as fibrosis of the tissues, stump neuroma, instability in the metatarsophalangeal joints, hypoesthesia or dysesthesia [

6,

7]. Techniques such as ultrasound-guided or endoscopic surgery have shown better results in terms of precision and recovery [

8,

9]. Nevertheless, continuous radiofrequency remains a highly effective alternative, with success rates ranging from 80% to 85%, offering an effective option with more favorable recovery for neuroma treatment [

10,

11]. The action´s mechanism of radiofrequency is based on the generation of heat through radio waves (electromagnetic induced current) emitted from a needle with an active tip of 0.5 or 1 cm. The controlled heat is produced by the agitation and friction of ions in the tissues near the needle. The result is the denaturation of nerve tissue proteins, causing coagulation and tissue destruction. This thermal ablation interrupts nerve stimuli, preventing the nerve from sending pain signals [

12,

13].

The failure rate of the radiofrequency technique varies between 15% and 20%. This failure rate could be due to incomplete nerve ablation, as complete denervation theoretically should result in no sensitivity in the innervated area [

14]. Currently, the protocol is applying times, 90 ºC and 90 seconds. We believe that nerve ablation might not be complete in this percentage of failed cases, where ablation is not applied throughout the neural and perineural extent. This failure rate could be influenced by the application area of the radiofrequency, being applied directly on the nerve fibrosis instead of on the healthy nerve in a more proximal area. Additionally, some variations of the current protocol might improve the results, such as applying the radiofrequency in different areas to increase the exposure area, as well as the number of applications. Maybe more applications increase the ablation area, thus improving the chances of success.

Although continuous radiofrequency aims for complete nerve ablation to alleviate symptoms, there is no histopathological evidence that all nerve tissue has been burned. This suggests that in 15-20% of failed cases, radiofrequency may not have been able to burn the entire nerve. This limits the understanding of its mechanism of action. Therefore, the objective of this study is to evaluate the ablative effect of continuous radiofrequency on Morton's neuroma and analyze whether its size affects its effectiveness.

2. Cases Reports

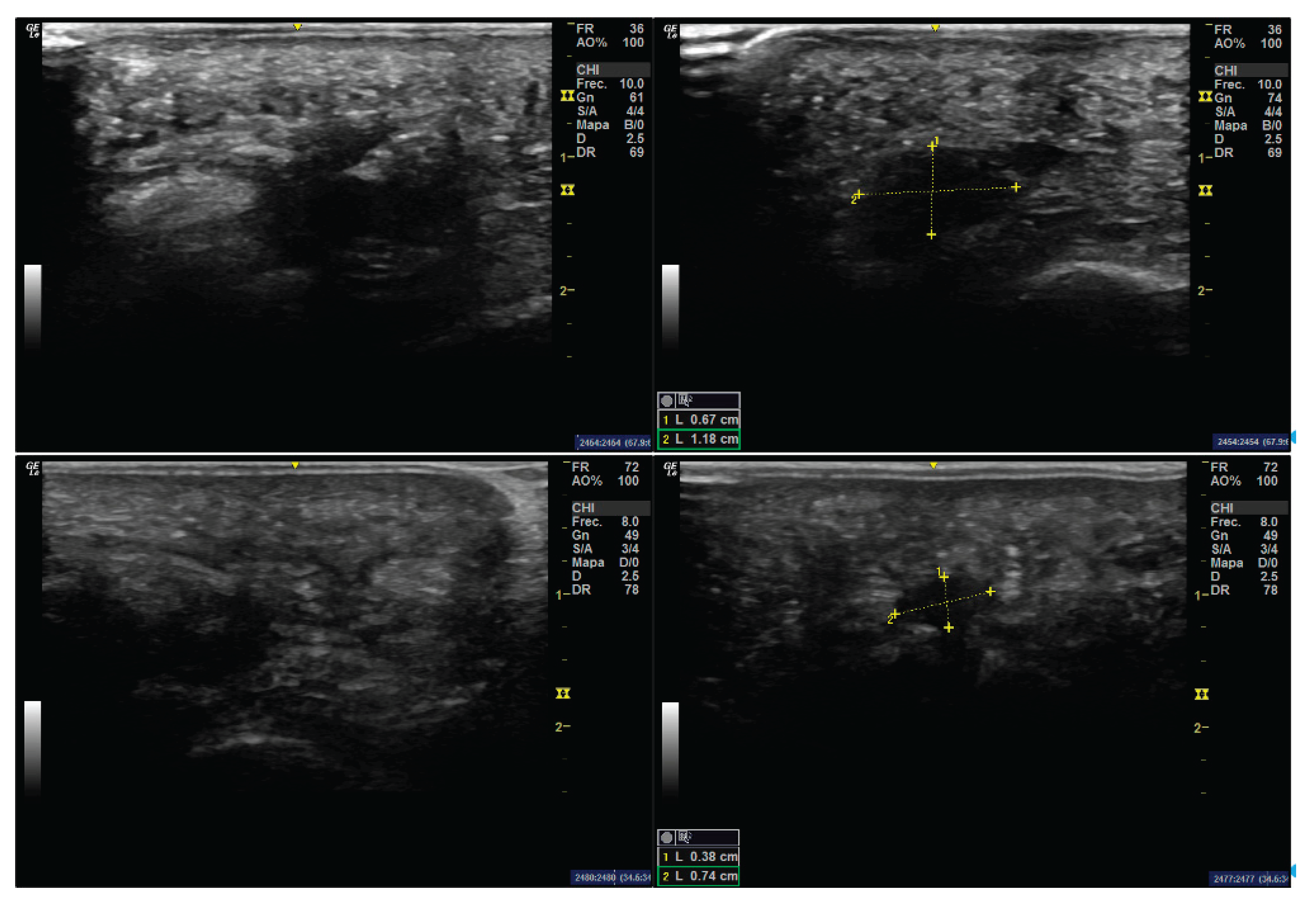

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Extremadura in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (ID 97//2022). The sample consisted of two patients who, due to their clinical characteristics, required neuroma excision. Both patients had undergone unsuccessful conservative treatment for at least two years prior to surgical intervention. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant for both the surgical procedure and their inclusion in the study. Preoperative ultrasonographic measurements of the neuroma were performed to document its size prior to excision. Imaging was conducted in both short- and long-axis views, focusing on the interdigital space between the third and fourth metatarsal heads of the right foot. A GE LOGIQ R7 ultrasound system equipped with a 12 MHz linear transducer was used for the assessments.

2.1. Case 1

A 44-year-old female patient at the time of surgery presented with bilateral Morton’s neuroma. The neuroma in the left foot was asymptomatic, while the right foot neuroma had been associated with recurrent pain over the previous five years. No relevant medical history or known drug allergies were reported. On short-axis ultrasound imaging, the neuroma appeared as a hypoechoic mass measuring 1.18 mm in width (

Figure 1), and was visualized during Mulder’s maneuver. Over the last five years, the pain had progressed from mild discomfort to a completely disabling condition during the final year, despite conservative management including orthotic interventions and corticosteroid infiltrations with betamethasone. Surgical excision of the neuroma was ultimately indicated.

2.2. Case 2

A 52-year-old female patient presented with a Morton’s neuroma in the right foot, associated with a three-year history of painful symptoms. Multiple attempts at conservative treatment—including footwear modifications and custom insoles—failed to provide symptom relief. Although the patient experienced slight improvement with orthotic insoles, the outcome was ultimately unsatisfactory. In this second case, the neuroma was located in the third intermetatarsal space and measured 0.74 mm in width on short-axis ultrasonography (

Figure 1). Mulder’s sign was also positive.

2.3. Surgical Technique

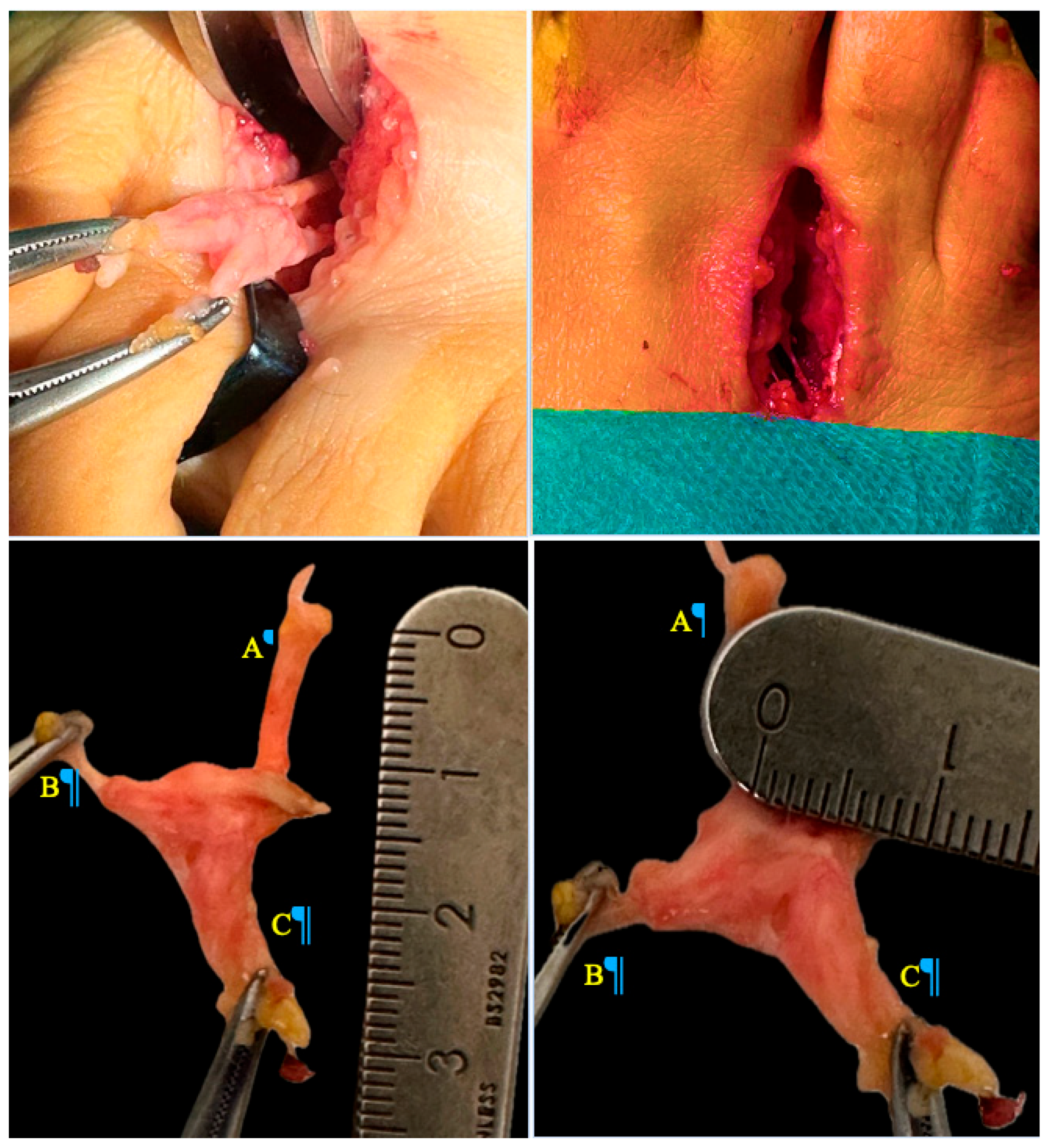

Surgical excision of the neuroma via a dorsal approach was performed. In both cases, a longitudinal dorsal approach was performed over the affected intermetatarsal space, approximately 3 cm in length, following skin tension lines to minimize scarring (

Figure 2). Layered dissection was carried out, carefully identifying and preserving surrounding neurovascular structures. The transverse intermetatarsal ligament was exposed and meticulously sectioned to access the neuroma. Once the hypertrophied common digital plantar nerve was identified, proximal dissection was performed until healthy nerve tissue was reached. The nerve was then transected using a scalpel, and the proximal stump was secured. Electrocautery was subsequently applied to minimize the risk of symptomatic stump neuroma formation.

Meticulous hemostasis was achieved, and layered wound closure was performed. The deep fascia and subcutaneous tissue were approximated using simple interrupted absorbable sutures (polyglactin 910, Vicryl 4-0). The skin was closed with an absorbable intradermal suture to optimize the aesthetic outcome and reduce the risk of wound dehiscence. Finally, a moderate compressive dressing was applied to ensure tissue stability and minimize postoperative inflammation.

2.4. Application of Radiofrequency

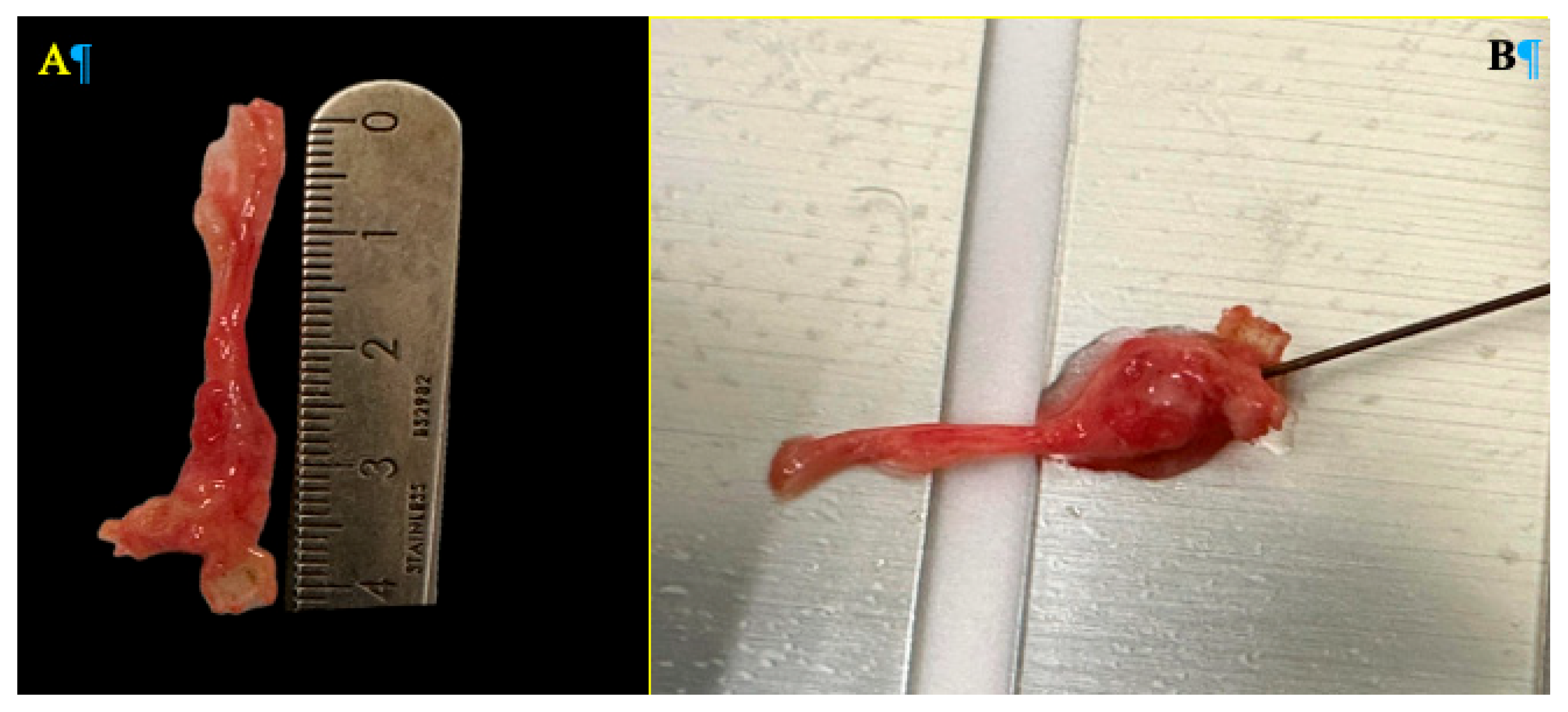

Following resection, ex vivo continuous radiofrequency ablation was applied to the excised neuroma. Using a monopolar needle with a 0.5 cm active tip, radiofrequency ablation was performed at a temperature of 90°C for 90 seconds, employing the TLG10 RF Generator (manufactured by Top, Japan, 2021). Upon completion of the procedure (

Figure 3), the specimens were submitted to the Department of Pathology for histological evaluation of the radiofrequency-induced thermal damage. Special attention was given to the depth of the thermal lesion and the extent of axonal degeneration. The objective of this analysis was to determine whether the neuroma size influenced the effectiveness of the radiofrequency treatment, considering the relationship between neuroma dimensions and the ablation diameter achieved by the needle.

3. Results

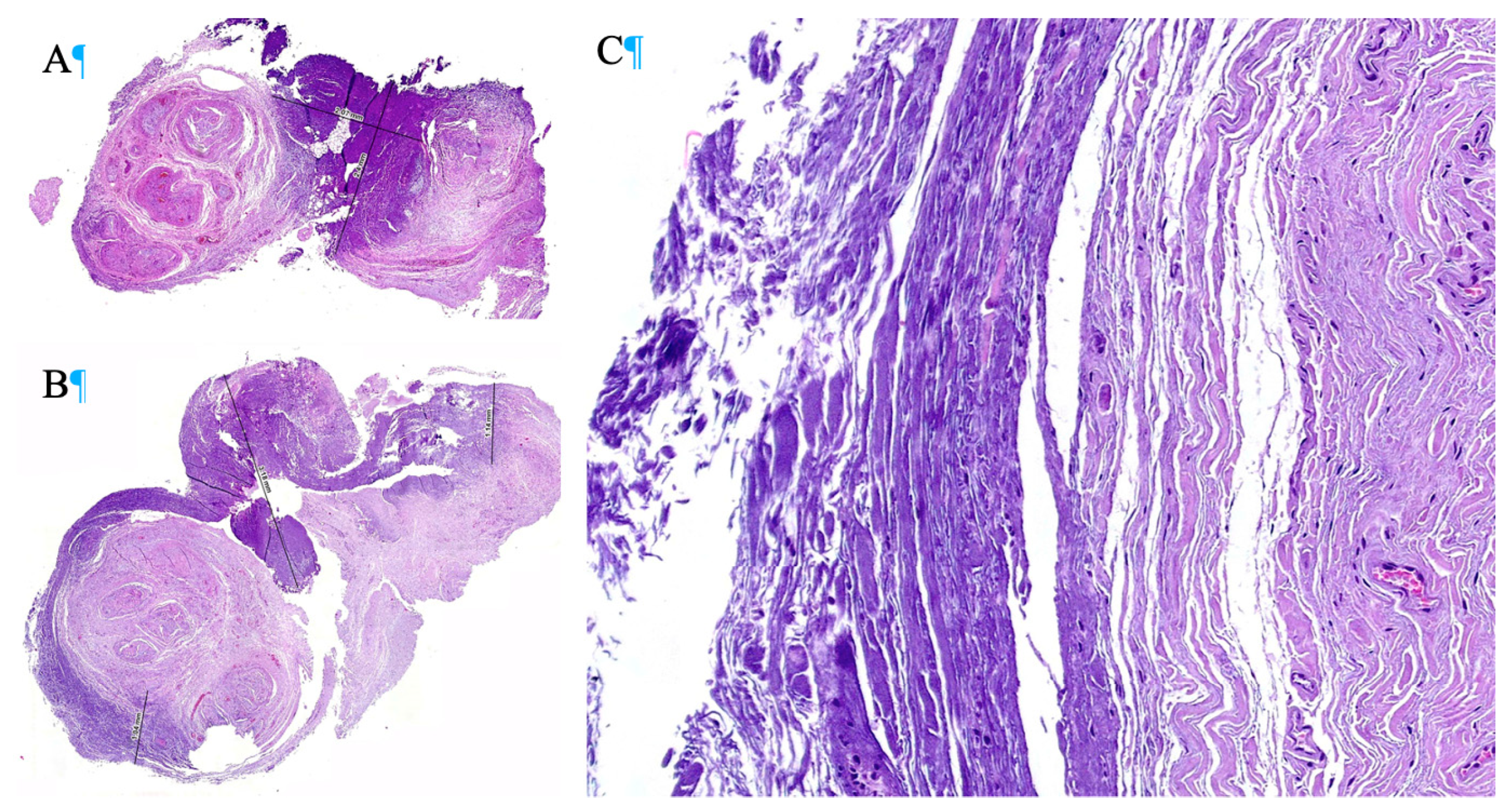

In the first case, the specimens obtained after ex vivo radiofrequency ablation exhibited homogeneous thermal necrosis, with a maximum depth of 2.4 mm. Hematoxylin-eosin staining revealed a characteristic pattern of coagulative necrosis, with extensive destruction of neural tissue in areas subjected to the greatest thermal exposure. In the corresponding histological image (

Figure 4), the darker regions represent areas where radiofrequency caused the most significant thermal damage, resulting in substantial ablation of nervous tissue. These areas demonstrated marked structural loss, collagen denaturation, and disruption of the organization of nerve fascicles.

In contrast, the lighter regions indicate areas where ablation was incomplete, preserving the structural integrity of some neural components. This suggests that although radiofrequency ablation induced homogeneous necrosis in the central portion of the neuroma, the effect decreased toward the periphery, allowing the survival of some peripheral nerve fascicles. In the second case, which also involved ex vivo radiofrequency ablation, a more extensive thermal necrosis was observed, reaching a depth of up to 3.18 mm. Despite the increased depth of tissue injury, the histological pattern maintained a homogeneous distribution of necrosis, with uniform involvement across the ablation zone. In the corresponding histological image (

Figure 4), the darker regions once again reflect areas exposed to higher temperatures and thus greater thermal damage. These areas demonstrated deeper and more extensive necrosis, with structural collapse of neural tissue and complete loss of cellular nuclei. Unlike the first case, a reduced amount of viable neural tissue was observed at the periphery, suggesting that in this patient, the ablation reached a larger proportion of the neuroma. Nevertheless, some lighter peripheral zones were still present, indicating that despite the greater extent of necrosis, complete ablation of the neuroma was not achieved.

4. Discussion

Continuous radiofrequency (RF) ablation for the treatment of Morton’s neuroma has demonstrated a relatively high success rate in pain reduction, with previous studies reporting pain relief rates between 80% and 85% [

10,

11]. However, the ability of RF to achieve complete neuroma ablation may be limited by the size of the lesion. Only one study to date has provided evidence that neuroma size could be a limiting factor in the effectiveness of various treatments [

15]. The maximum depth of necrosis generated by RF is approximately 3 mm [

13,

16], which may be insufficient to completely ablate larger neuromas. This could explain the suboptimal outcomes in 15–20% of cases, or why some studies have shown that multiple applications at different points are more effective [

17].

Additionally, the use of a needle with a 1 cm active tip, as opposed to the 0.5 cm tip used in this study, may improve results by increasing the ablation area. Another important factor is the location of the lesion. Techniques using fluoroscopic guidance have shown similar results to those using ultrasound guidance. However, fluoroscopy-guided RF is typically performed more proximally, which may result in damage to healthy nerve tissue. In contrast, ultrasound-guided RF allows for a more distal approach, targeting the neuroma itself while avoiding damage to unaffected nerve segments, potentially increasing the precision and safety of the procedure.

An improvement to the technique was already proposed in the study "Three RF applications are better than two", where applying RF at different positions resulted in better clinical outcomes. This supports the theory that the lesion area created by RF is limited to a diameter of approximately 3 mm. This concept is crucial, as performing RF at a single site or simply increasing the duration of the ablation does not expand the area of effect [

17]. However, increasing the temperature above 90°C in an attempt to enlarge the lesion could be counterproductive, as it may induce cell death in healthy tissue and exacerbate inflammation [

13].

Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring may be a key tool for optimizing RF treatment outcomes. This technique allows the clinician to adjust RF parameters in real time, such as the number and positioning of applications, thereby increasing the likelihood of achieving complete neural ablation. Although neurophysiological monitoring is typically used to preserve nerve function in surgery, its purpose in this context is the opposite: to ensure that the nerve has been entirely disrupted and no longer conducts impulses. Real-time assessment of neural response enables confirmation of complete signal interruption, minimizing the risk of nerve regeneration and recurrence of pain [

18]. Thus, intraoperative monitoring could enhance the efficacy of RF by ensuring a definitive treatment.

In summary, although continuous RF is effective in reducing pain associated with Morton’s neuroma, it does not guarantee complete ablation of the neural tissue. Technique modifications, such as using needles with longer active tips, targeting more proximal segments of the neuroma, and performing multiple ablations at different sites, may improve outcomes. Furthermore, intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring offers an additional layer of control during the procedure, enabling more precise and reliable ablation.

Future studies should investigate whether there is a specific neuroma size threshold beyond which RF treatment becomes less effective.

5. Conclusions

In both cases, ex vivo radiofrequency ablation resulted in homogeneous thermal necrosis, with differences in the depth of injury observed. This study supports the notion that continuous radiofrequency is an effective tool in the management of Morton’s neuroma, though it presents limitations, particularly in larger neuromas. The histological images clearly show that the darker areas correspond to regions exposed to higher temperatures and therefore exhibit greater thermal damage, while the lighter areas reflect residual neural tissue that was not completely ablated. Despite the overall homogeneous distribution of injury in both specimens, the presence of intact tissue at the neuroma margins indicates that radiofrequency ablation, although effective in the central portion, does not consistently reach the entirety of the neural structure. The results suggest that neuroma size and RF application technique play a crucial role in treatment effectiveness. Likewise, greater proximity of the needle to the nerve and multiple ablations at different points along the healthy nerve segment may yield more satisfactory outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G. C-N. and A. M-N., methodology, A. F-G. and S. M.; resources, F. G., M. F-P., F. M-D. and E. S-P.; writing—original draft preparation, G. C-N.; writing—review and editing, G. C-N, A. F-G. and A. M-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Extremadura (Protocols code 97//2022, date of approval April, 16th of 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mann RA, Reynolds JC. Interdigital neuroma--a critical clinical analysis. Foot Ankle. 1983;3(4):238-43. [CrossRef]

- Adams WR, 2nd. Morton's neuroma. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2010;27(4):535-45.

- Wu KK. Morton's interdigital neuroma: a clinical review of its etiology, treatment, and results. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1996;35(2):112-9; discussion 87-8. [CrossRef]

- Valisena S, Petri GJ, Ferrero A. Treatment of Morton's neuroma: A systematic review. Foot Ankle Surg. 2018;24(4):271-81. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Santiago F, Prados Olleta N, Tomas Munoz P, Guzman Alvarez L, Martinez Martinez A. Short term comparison between blind and ultrasound guided injection in morton neuroma. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(2):620-7.

- Womack JW, Richardson DR, Murphy GA, Richardson EG, Ishikawa SN. Long-term evaluation of interdigital neuroma treated by surgical excision. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29(6):574-7. [CrossRef]

- Kasparek M, Schneider W. Surgical treatment of Morton's neuroma: clinical results after open excision. Int Orthop. 2013;37(9):1857-61. [CrossRef]

- Nieves GC, Fernandez-Gibello A, Moroni S, Montes R, Marquez J, Ortiz MS, et al. Anatomic basis for a new ultrasound-guided, mini-invasive technique for release of the deep transverse metatarsal ligament. Clin Anat. 2021;34(5):678-84.

- Barrett SL. Endocsopic Decompression of Intermetatarsal Nerve (EDIN) for the Treatment of Morton’s Entrapment— Multicenter Retrospective Review. Open J Orthop 2012;2(2):19-24. [CrossRef]

- Chuter GS, Chua YP, Connell DA, Blackney MC. Ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation in the management of interdigital (Morton's) neuroma. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(1):107-11. [CrossRef]

- Moore JL, Rosen R, Cohen J, Rosen B. Radiofrequency thermoneurolysis for the treatment of Morton's neuroma. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;51(1):20-2.

- Urbano Cabello J. Revisión narrativa sobre el uso y aplicaciones de la radiofrecuencia para el tratamiento del dolor musculoesquelético. Rev Esp Podol. 2021.

- Cosman ER, Jr., Cosman ER, Sr. Electric and thermal field effects in tissue around radiofrequency electrodes. Pain Med. 2005;6(6):405-24. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Chen Y, Yao B, Song P, Xu R, Li R, et al. Neuropathologic damage induced by radiofrequency ablation at different temperatures. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2022;77:100033. [CrossRef]

- Masala S, Cuzzolino A, Morini M, Raguso M, Fiori R. Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Radiofrequency for the Treatment of Morton's Neuroma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41(1):137-44. [CrossRef]

- Cosman ER, Jr., Dolensky JR, Hoffman RA. Factors that affect radiofrequency heat lesion size. Pain Med. 2014;15(12):2020-36.

- Brooks D, Parr A, Bryceson W. Three Cycles of Radiofrequency Ablation Are More Efficacious Than Two in the Management of Morton's Neuroma. Foot Ankle Spec. 2018;11(2):107-11. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Perez M, Oller-Boix A, Perez-Lorensu PJ, de Bergua-Domingo J, Gonzalez-Casamayor S, Marquez-Marfil F, et al. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring in peripheral nerve surgery: Technical description and experience in a centre. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59(4):266-74. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).