Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Outline

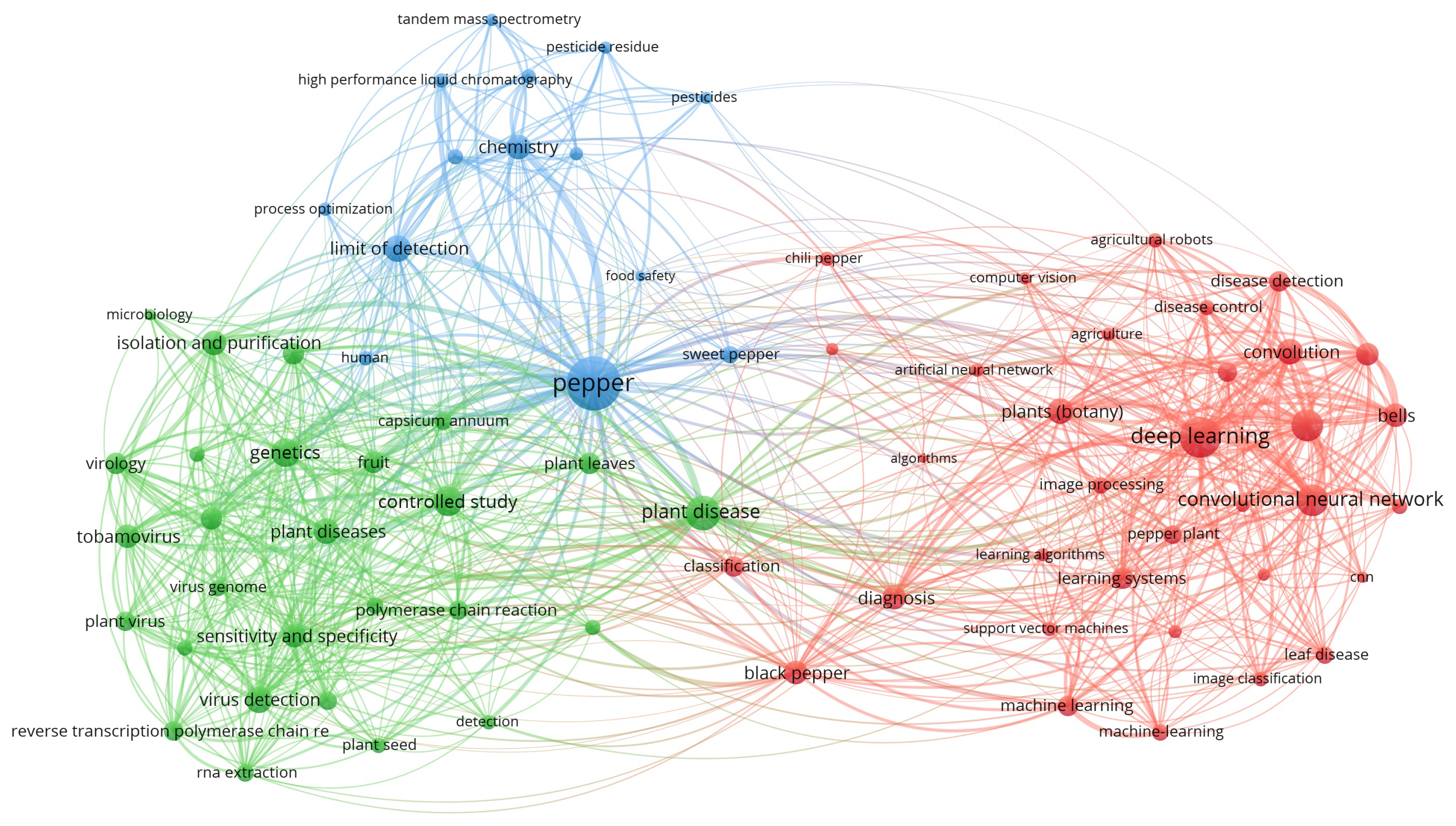

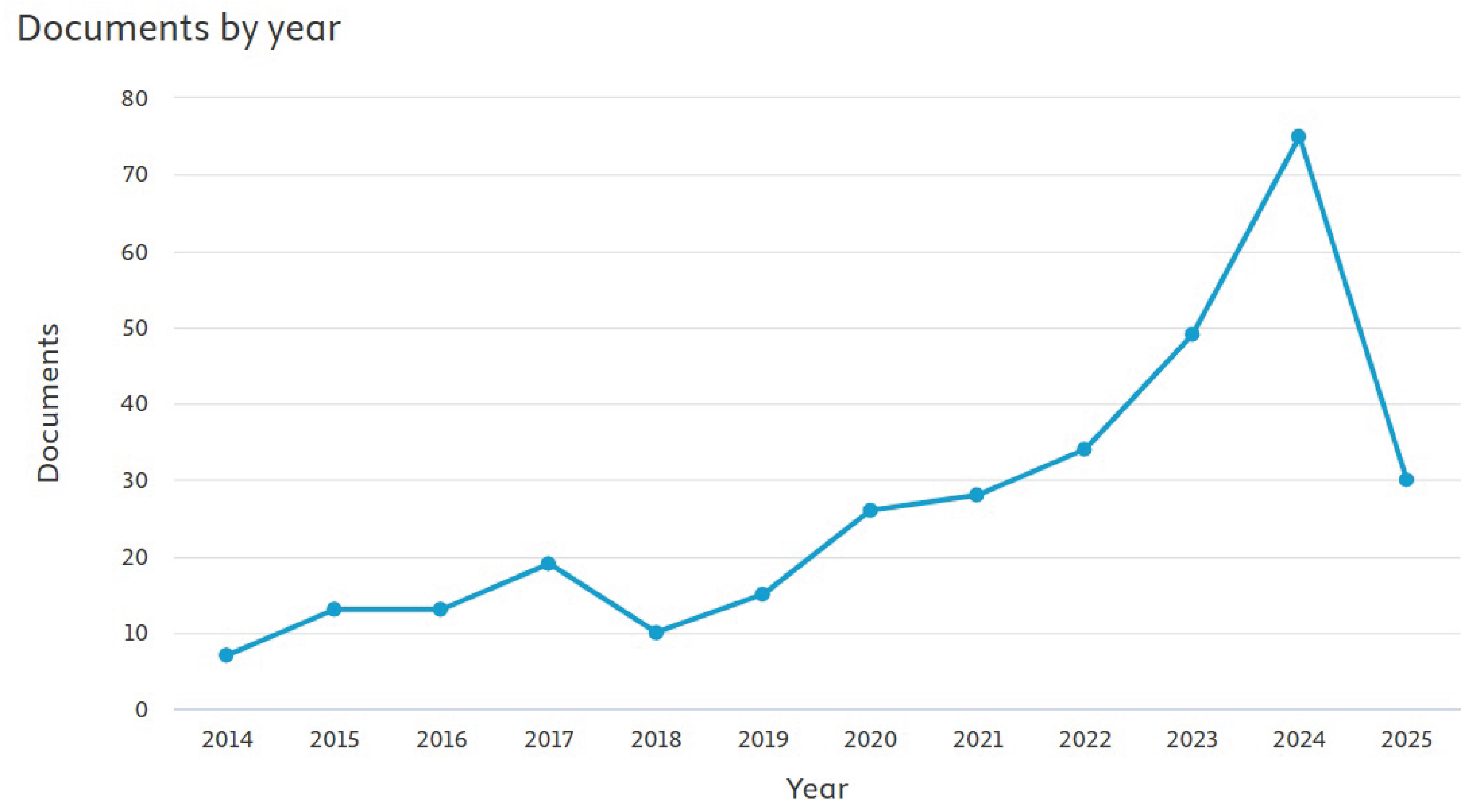

1.2. State-of-the-Art Review

- Machine learning (ML) is a subfield of IA which comprises different algorithms or models capable of "learning" patterns from data to make predictions [48].

- Deep learning (DL) is a subdivision of ML that implements deep neural networks (DNNs) with multiple layers. When the data set of the study is large, it is suggested to implement DNNs since they are efficient in processing large volumes of data, being especially employed in computer vision problems by using convolutional neural networks (CNNs). In tasks related to image segmentation, detection, and classification, deep learning is superior to traditional learning [48,49,50].

- Computer vision (CV) allows technologies to have the ability to process and analyze, and interpret visual data. The topics with the most research coming from this field are filtering, segmentation, image classification, detection, and tracking, among others [50].

1.3. Related Work

1.4. Main Contributions

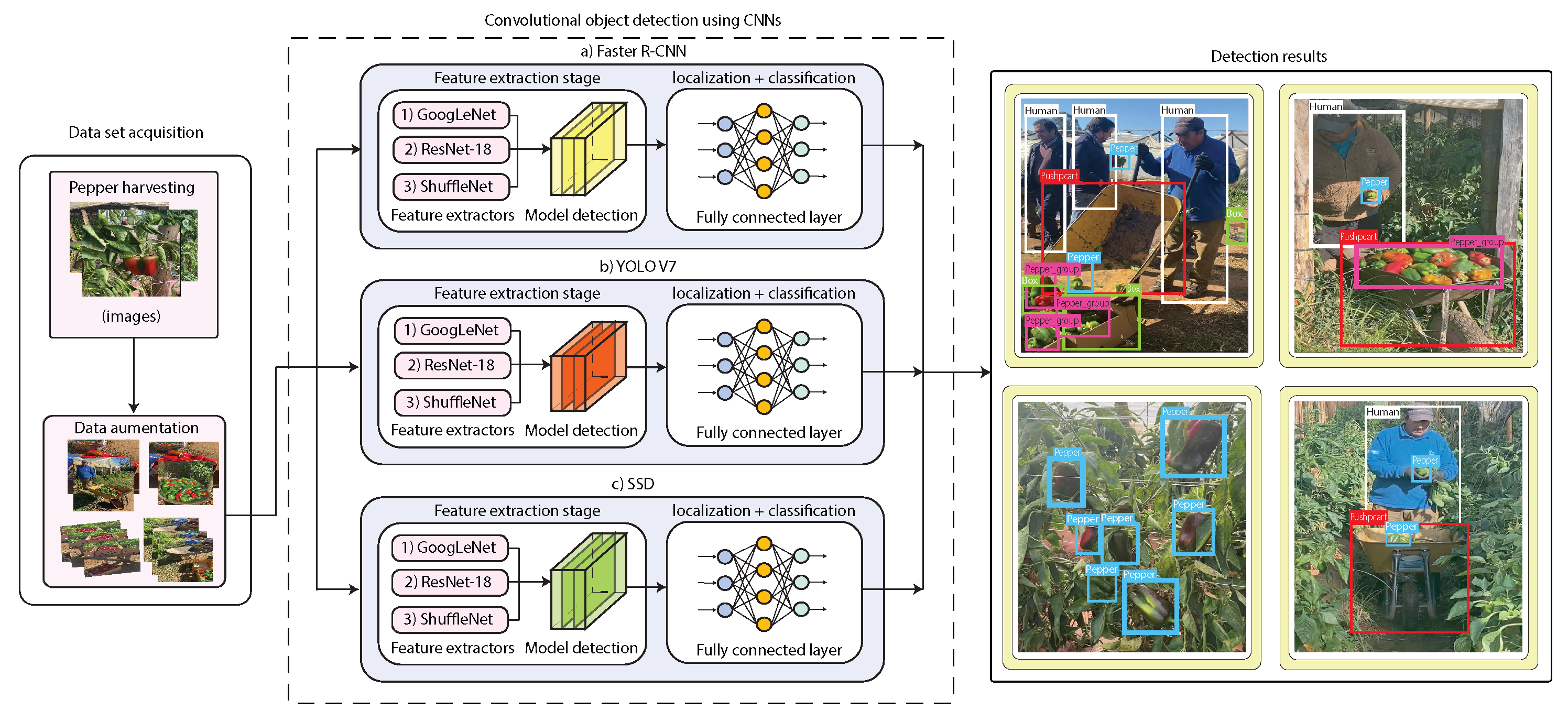

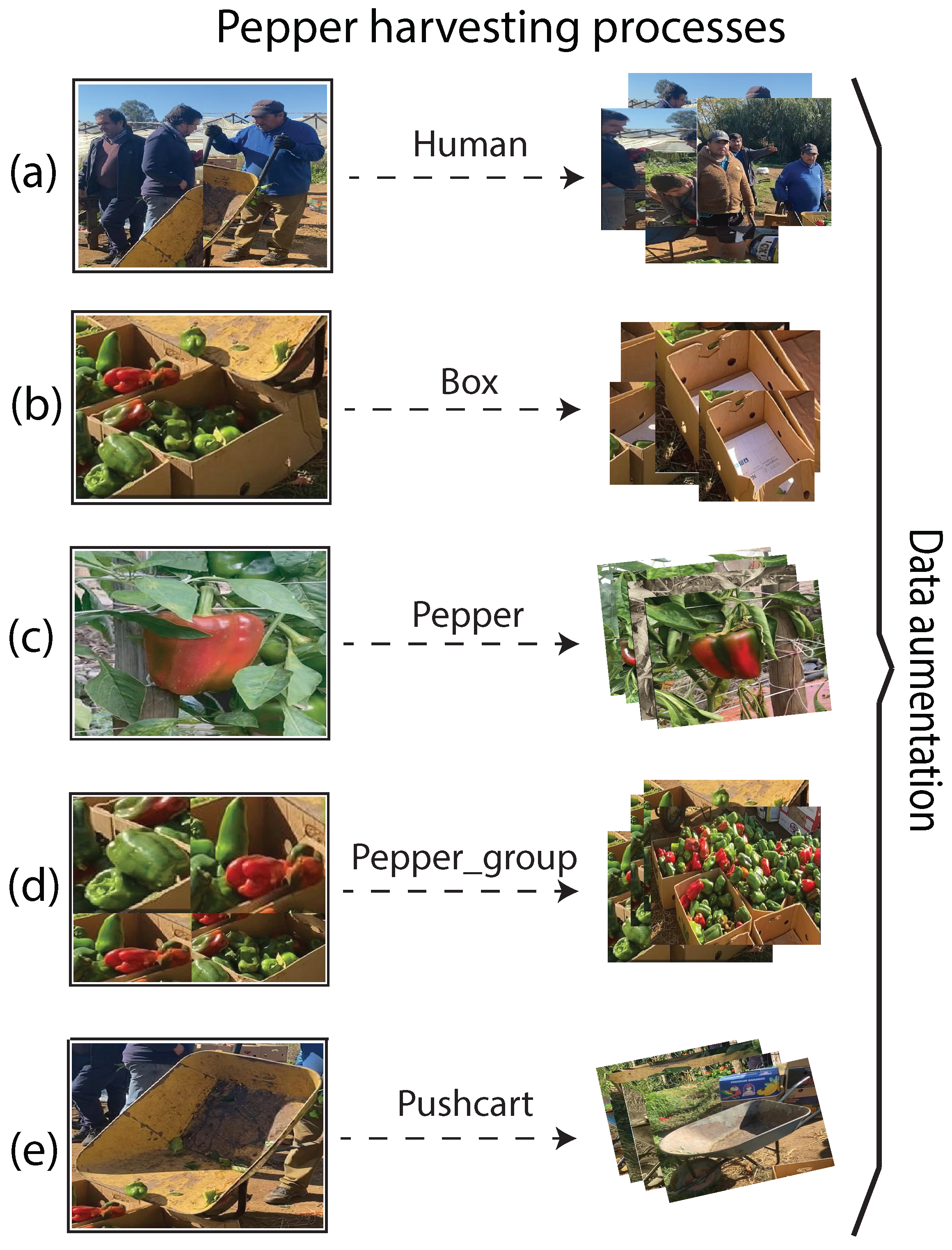

- We obtained an RGB image dataset during a pepper harvesting process in a Chilean farm based on a total of 210 RGB images. We manually labeled each image to identify objects of interest (human, box, pepper, pepper group, and pushcart). We also applied data augmentation techniques to increase our dataset distribution to 630 images.

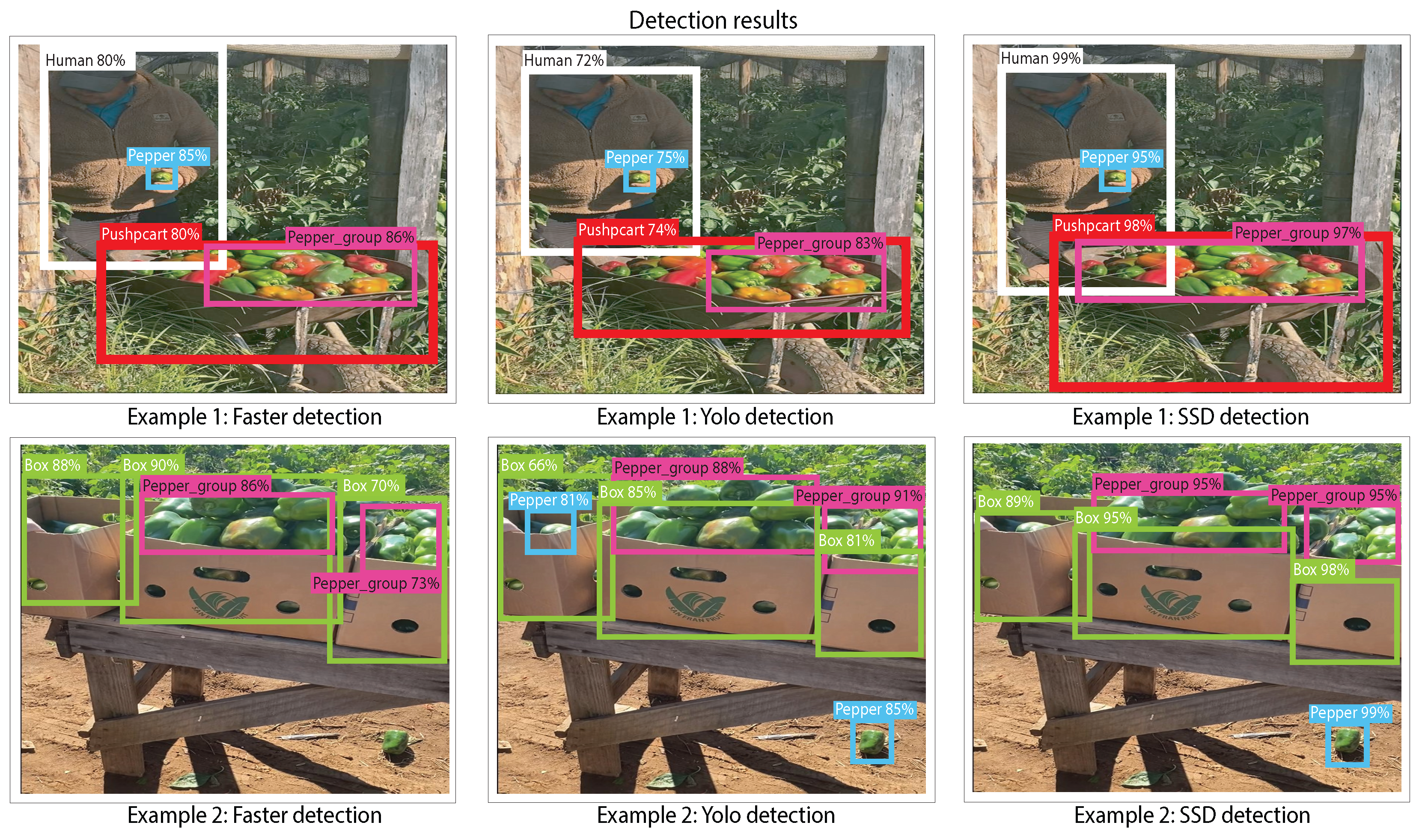

- We used three different object detection algorithms, which are You Only Look Once v7 (YOLOv7), Faster Region-Convolutional Neural Network (Faster R-CNN), and Single Shot Multi-Box Detector (SSD). For each object detection algorithm, we used three different feature extraction CNNs, which are GoogLeNet, ResNet-18, and ShuffleNet. We trained, validated, and tested each of the proposed object detection algorithms.

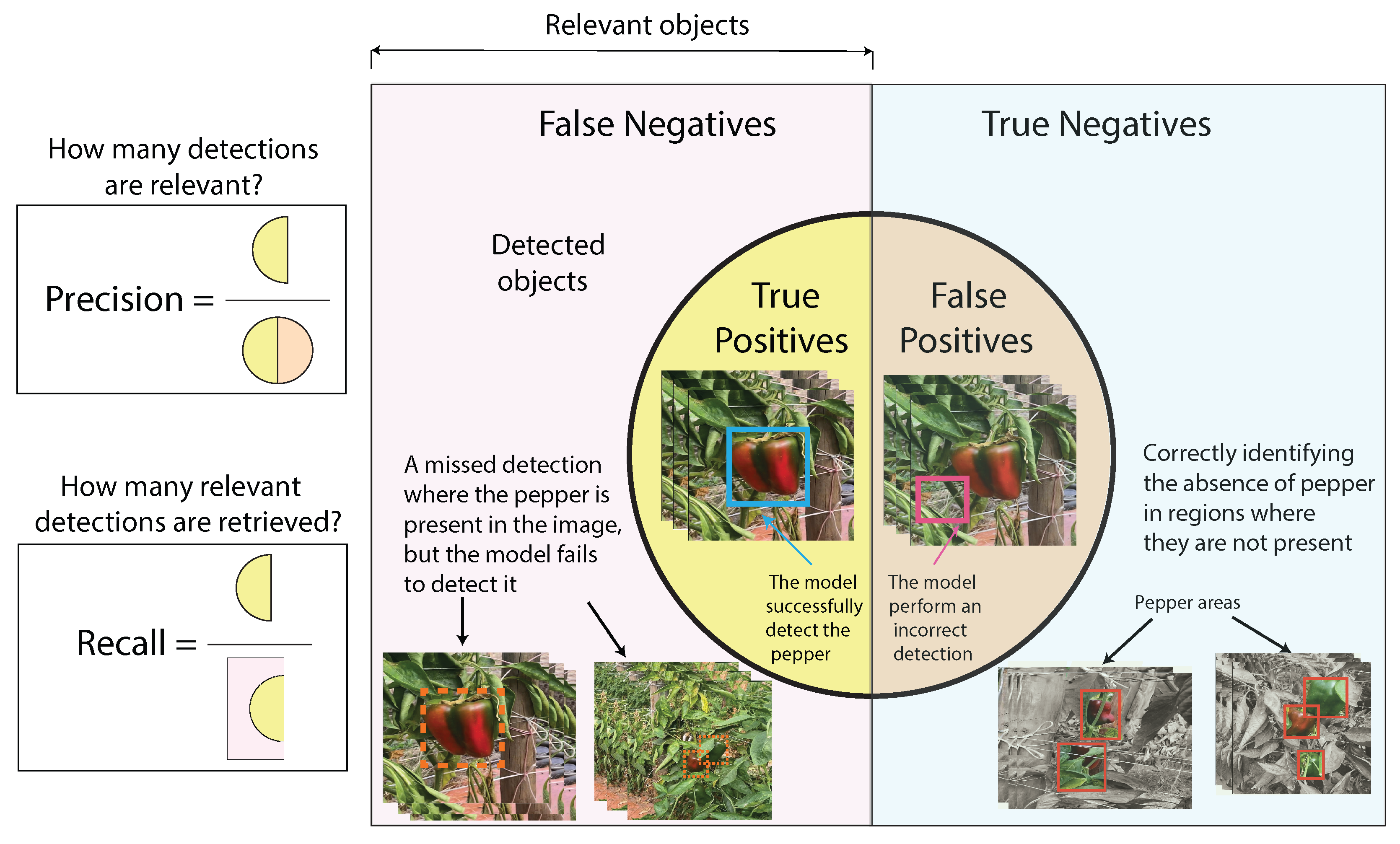

- We compared the performance of each model using precision-recall (PR) curves and mean average precision metrics (mAP). Additionally, we analyzed bias, variance, overfitting, and underfitting of each of the trained models.

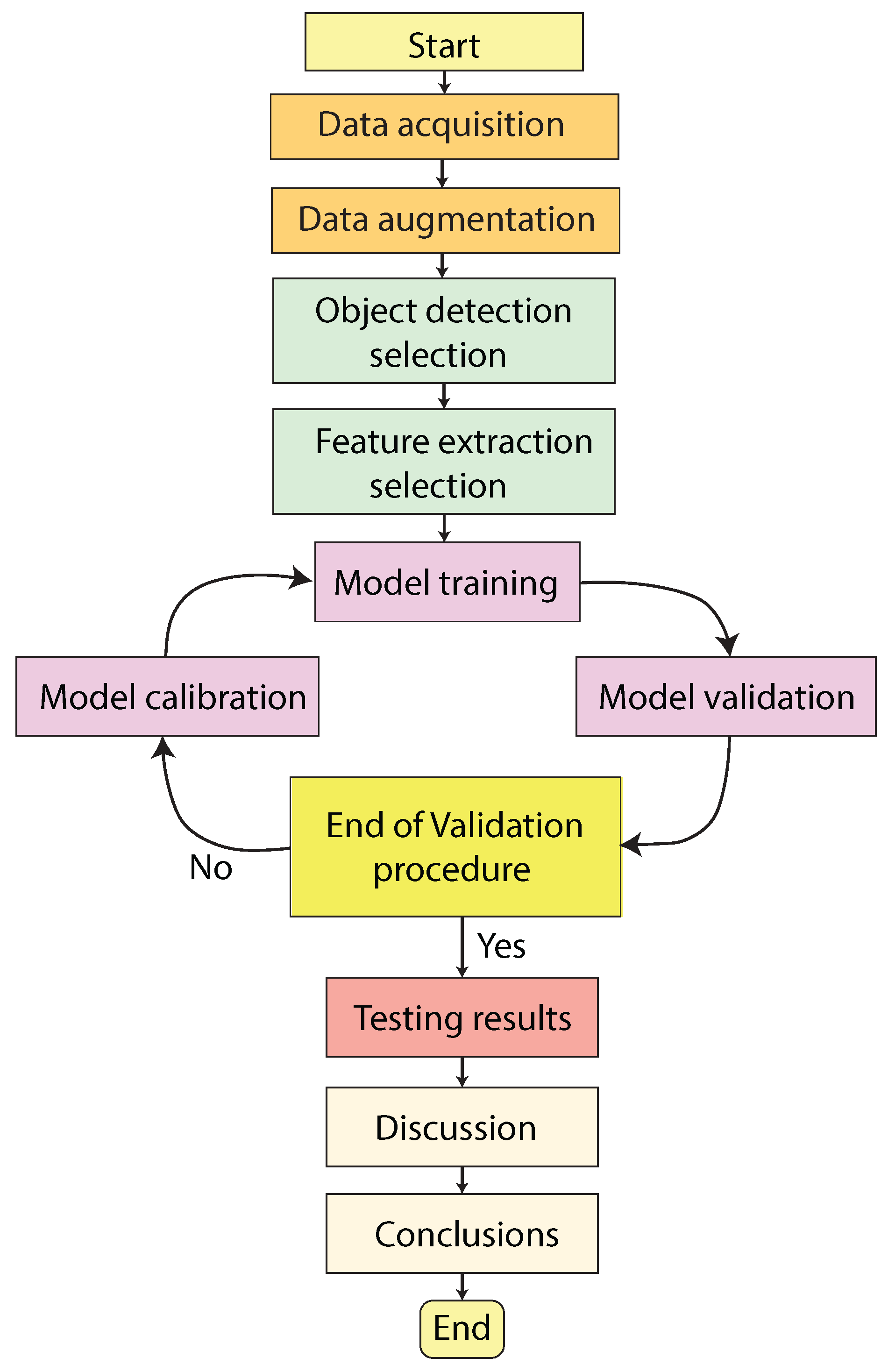

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition

| Dataset | Normal | Data Augmentation | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training | 168 | 336 | 504 |

| Validation | 21 | 42 | 63 |

| Test | 21 | 42 | 63 |

| Total | 210 | 420 | 630 |

2.2. Object Detection Algorithms

2.2.1. Object Detection Methods

Faster Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network (Faster R-CNN)

YOLOv7

Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD)

2.2.2. Feature Extraction Methods

GoogLeNet

ResNet-18

ShuffleNet

3. Evaluation Metrics

3.1. Precision and Recall

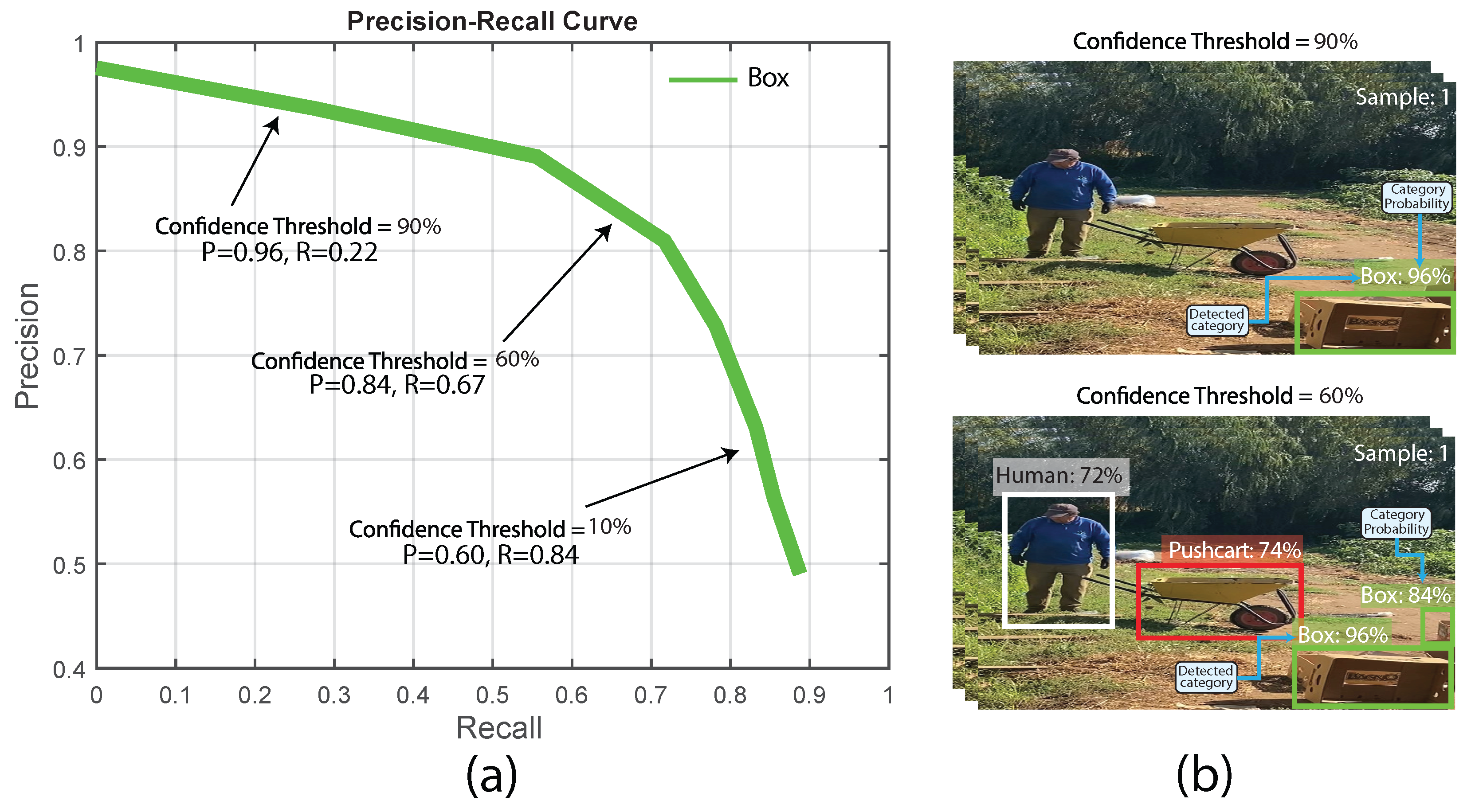

3.2. Precision-Recall Curve

3.3. Mean Average Precision (mAP)

3.4. Inference Times

4. Results

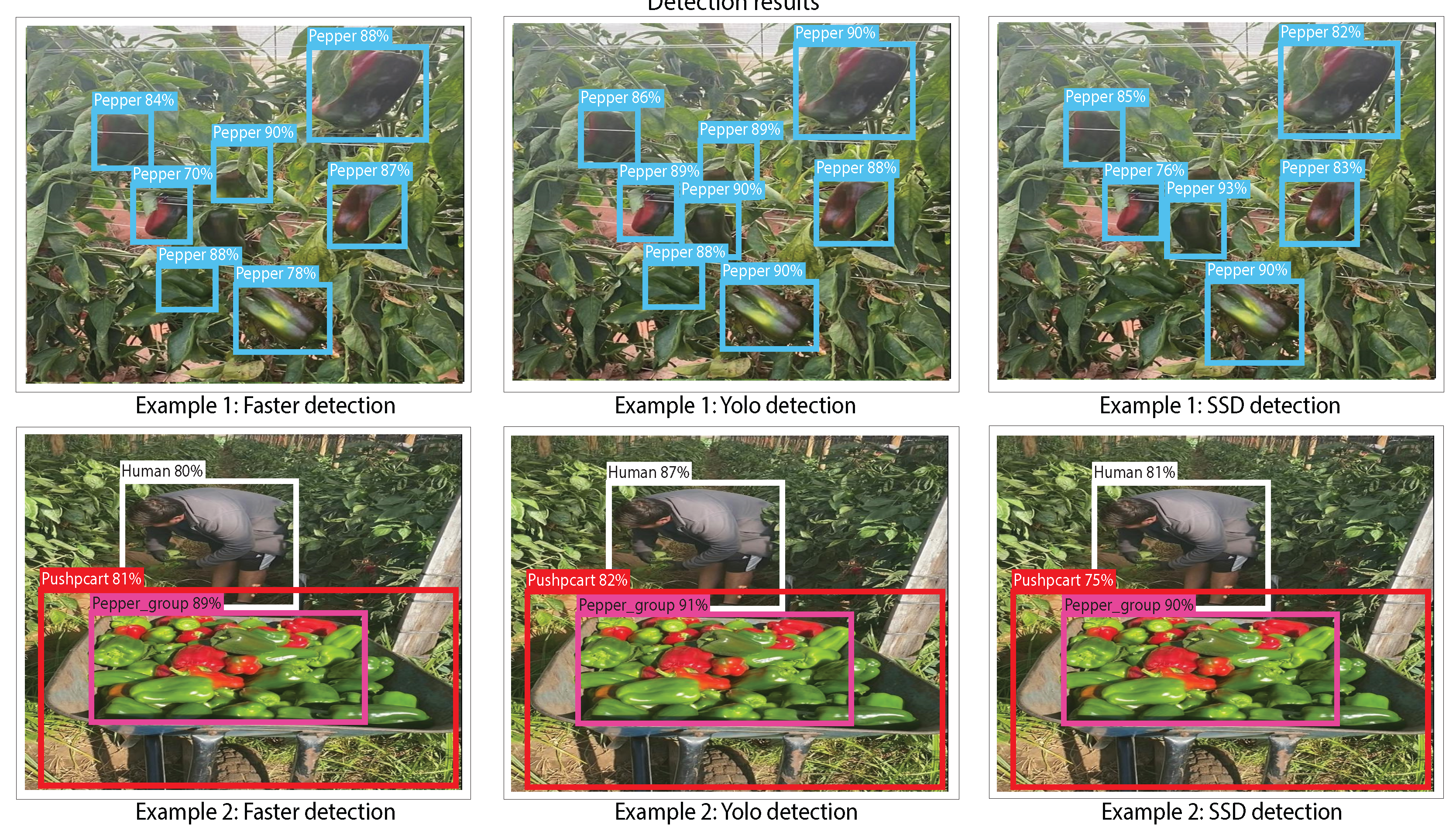

4.1. Faster R-CNN, YOLOv7,and SSD with GoogLeNet

- Table 3 summarizes that when employing GoogLeNet as a feature extractor, the Faster R-CNN, YOLOv7, and SSD models achieve very low accuracy results. For Faster R-CNN, Test 4 achieved the lowest results (training: 3%, validation: 2%, and test: 2%). Moreover, YOLOv7 exhibited low-performance results in test 2 (training: 2%, validation: 1% and tests: 1%). Finally, the SSD also displayed low-performance results in test 4 (training: 2%, validation: 2% and tests: 1%). These results reflect that the models trained under these configurations are experiencing underfitting issues. This means that the performance of the trained models does not fit with the proposed distribution of the pepper harvesting processes dataset, which also reflects a high bias.

- In test 16, the Faster R-CNN model achieves an accuracy of 88% in the training set, while the YOLOv7 and SDD models achieve values of 60% and 55%, respectively. This could be because the Faster R-CNN model is based on using an RPN (Region Proposal Network) stage, which, for this test, can be seamlessly adjusted to the distribution of the pepper harvesting processes dataset (low bias). In contrast, YOLOv7 and SSD employ a single-stage-based detection approach without utilizing an RPN stage, causing a misalignment with the distribution of the pepper harvesting processes dataset (underfitting). Compared to the Faster R-CNN results, the YOLOv7 and SDD models have low validation results, with 29% and 55%, respectively, and for testing, with 52% and 52%, respectively. The difference between the training accuracy values between the Faster R-CNN (88%), YOLOv7 (60%), and SSD (57%) models, suggests that for the hyper-parameter configuration used in test 16, the models with low results do not fully fit the dataset suggesting the presence of bias. Additionally, the slight decline in validation accuracy (YOLOv7: 29% and SSD: 55%) and tests for both models (YOLOv7: 52% and SSD: 52%) indicates a slight divergence, as the performance of the models exhibits a slight reduction in both validation and testing phases.

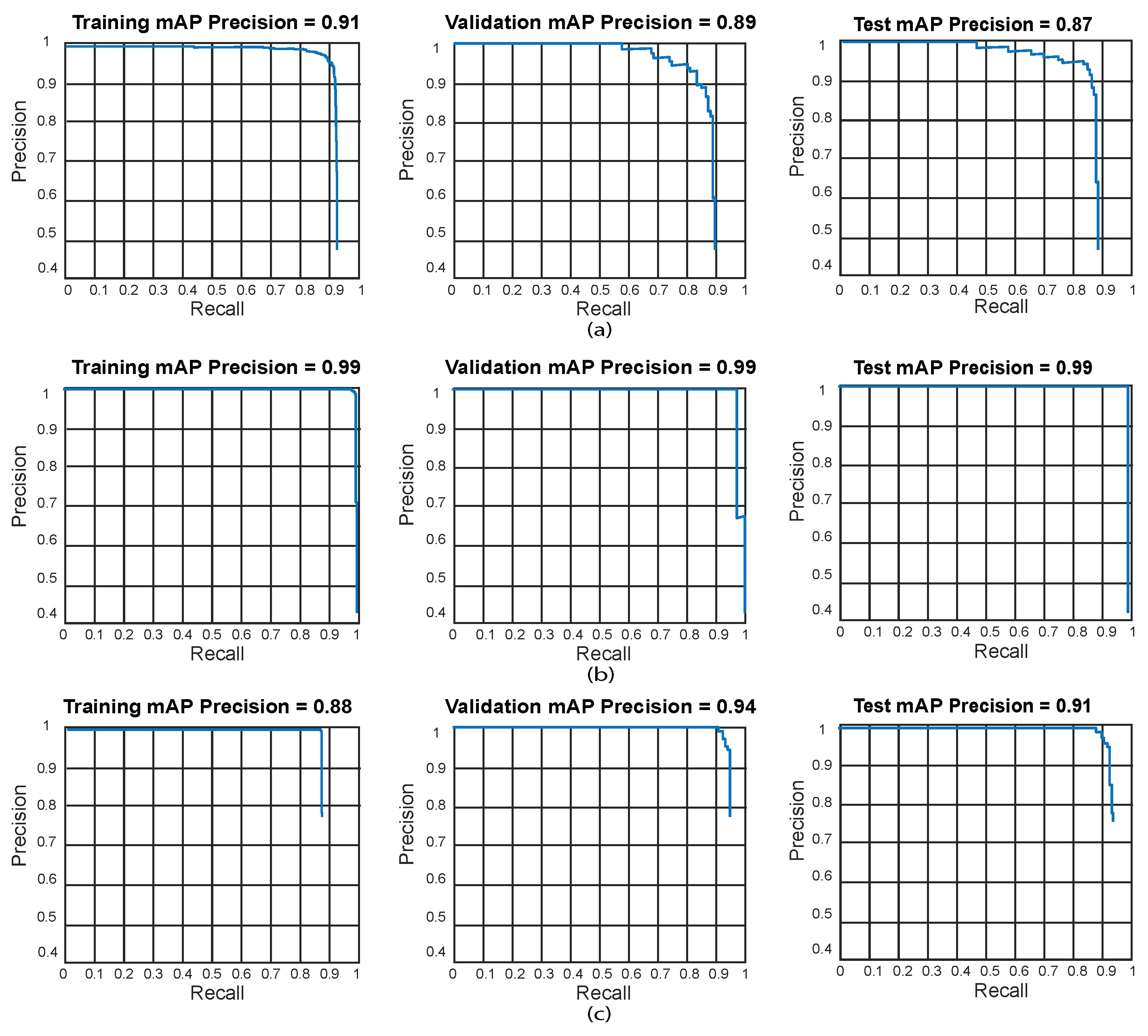

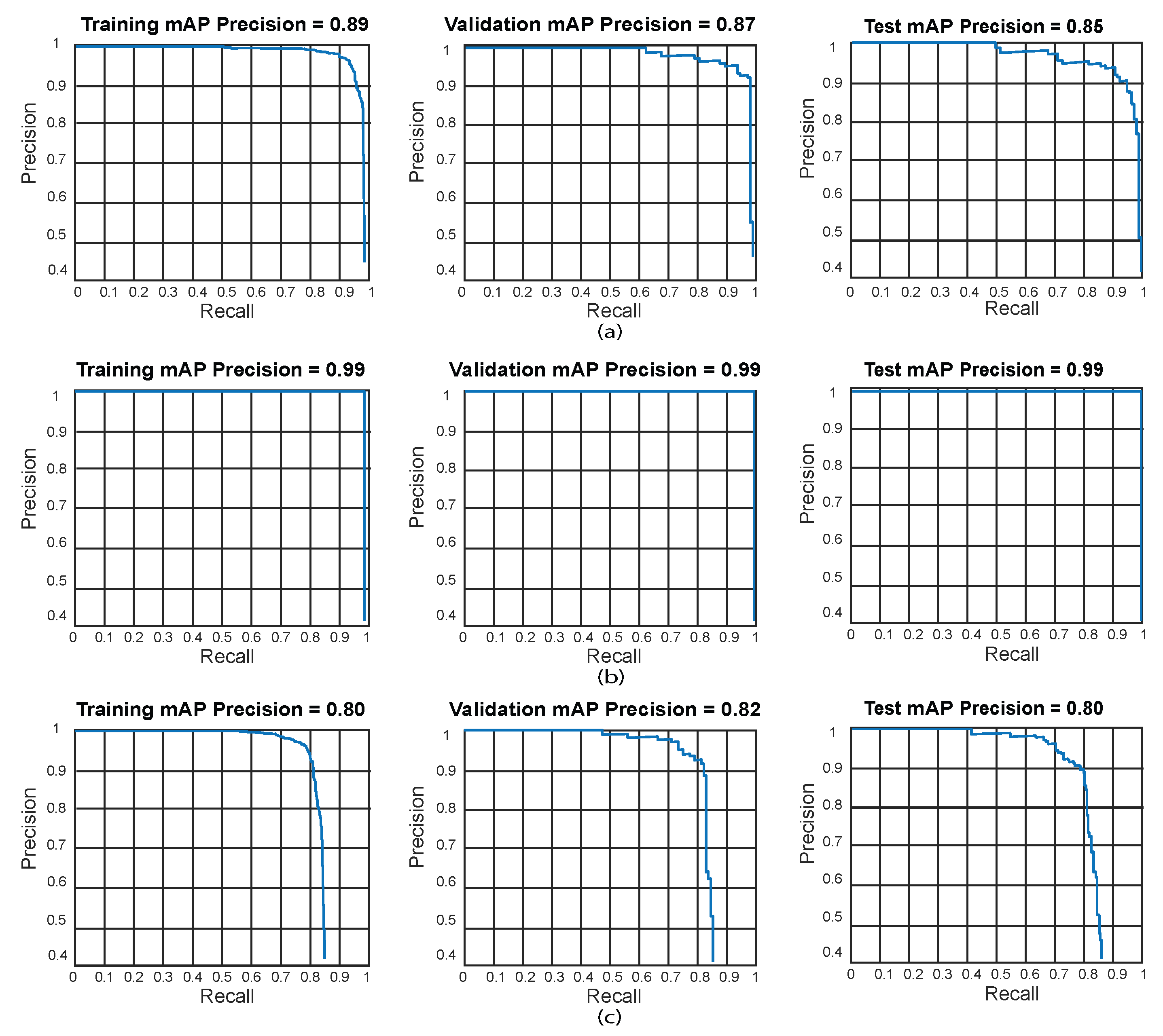

- The best results obtained when using the GoogLeNet as a feature extractor for the Faster R-CNN model were obtained in test 18 (training: 89.8%, validation: 87%, and tests: 85%). For YOLOv7 with GoogLeNet, the best result was obtained in test 10 (training: 99%, validation: 99.8%, and test: 99.6%). Ultimately, the SSD model using GoogLeNet achieved the best results in test 10 (training: 80%, validation: 82%, and tests: 80%). Based on the results presented in Table 3, the best model GoogLeNet as feature extraction in our dataset was for YOLOv7 using the hyper-parameter configuration of test 10. This model displays a minimal bias and variance, suggesting high generalization capabilities (low overfitting), since accuracy is hardly reduced in the training, validation, and testing phases.

4.2. Faster R-CNN, YOLOv7,and SSD with ResNet-18

- As displayed in Table 4, there are tests where using ResNet-18 as a feature extractor, the Faster R-CNN, YOLOv7, and SSD models achieves very low accuracy results. For Faster R-CNN, the test with the lowest results is test 3 (training: 3%, validation: 2% and test: 1%). YOLOv7 also presents low-accuracy results in test 5 (training: 2%, validation: 1% and test: 4%). Finally, the SSD also shows low results in test 8 (training: 1%, validation: 6% and tests: 4%). These results reflect that the models trained under these configurations face underfitting issues, meaning their performance does not align with the proposed distribution of the Pepper harvesting processes dataset. This suggests that training the models with the configurations employed in each test will result in a high presence of bias.

- According to Table 4, the Faster R-CNN object detection model delivers the lowest precision results. The lowest results for this model are in test 6 (training: 2%, validation: 2% and test: 1%), while the best results are in test 16 (training: 91%, validation: 89% and test: 87%). In comparison with the previous result, the test 16 from the Faster R-CNN model, managed to fit seamlessly into the Pepper harvesting processes dataset. Unlike the rest of the algorithms, the Faster R-CNN model may deliver results with a low level of accuracy due to its use of an RPN (Region Proposal Network) stage, which tends to suffer from an insufficient adjustment for our dataset distribution.

- The best results obtained when using the ResNet-18 network as a feature extractor depend strongly on the hyper-parameter configuration. The Faster R-CNN model obtained its best result in test 16 (training: 91%, validation: 89% and tests: 87%). For YOLOv7, the best result is in test 12 (training: 99%, validation: 99%, and test: 99%). For the SSD model, the best result was achieved in test 14 (training: 88%, validation: 94% and tests: 91%). Based on the results displayed in Table 4, the greatest model using ResNet-18 for this dataset is YOLOv7 with the hyper-parameter configuration of test 12. This model disclose low bias and variance, demonstrating high generalization capabilities (low overfitting), as its accuracy is barely reduced in the training, validation, and testing phases.

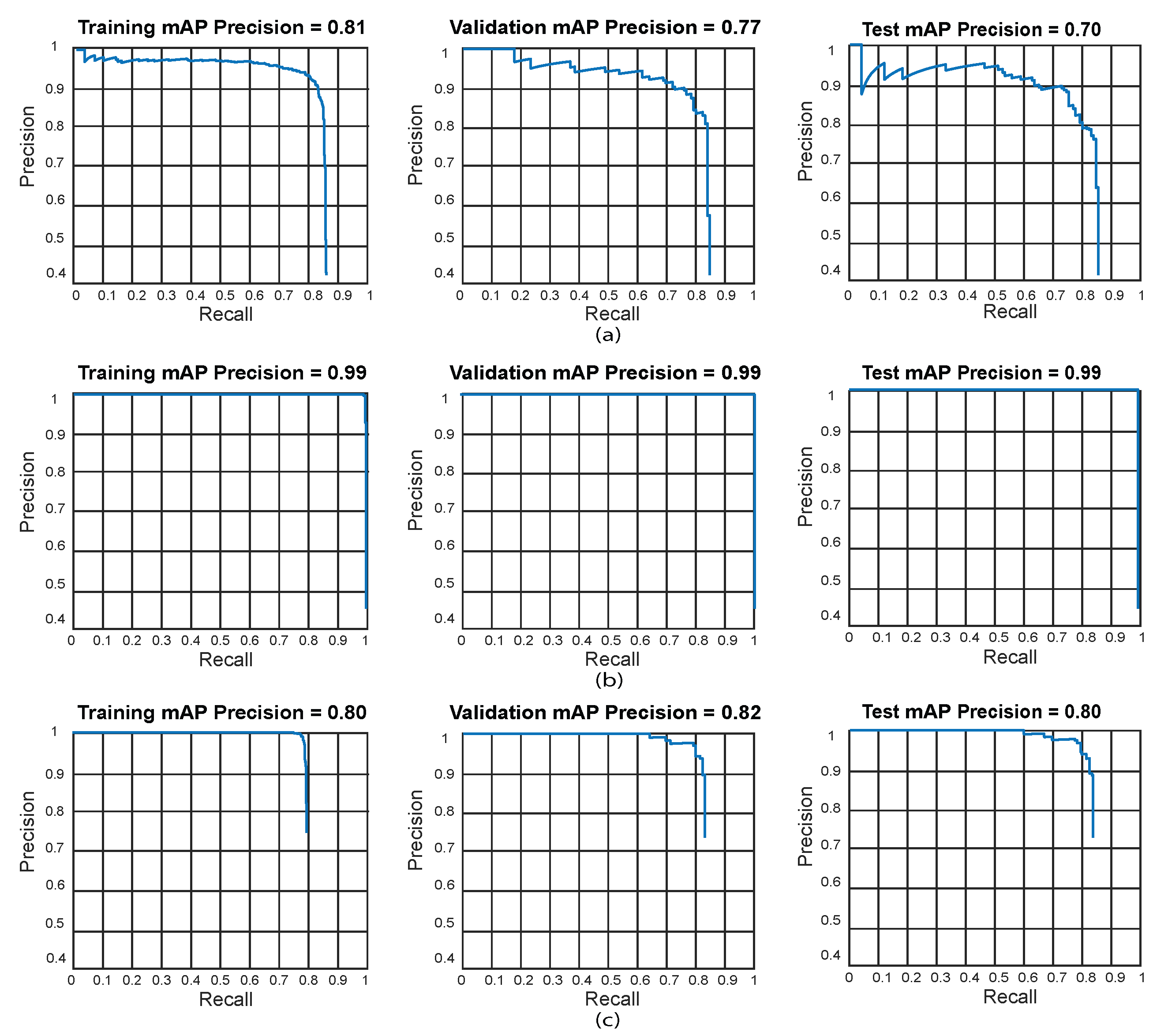

4.3. Faster R-CNN, YOLOv7, and SSD with ShuffleNet

- It can be observed in Table 5 that when using ShuffleNet as a feature extractor, there are tests where the Faster R-CNN, YOLOv7, and SSD models achieve very low accuracy results. In the Faster R-CNN case, the lowest results correspond to Test 5 (training: 2%, validation: 1% and test: 1%). YOLOv7 also presents low-accuracy results in test 17 (training: 3%, validation: 2% and tests: 3%). Also, the SSD model achieves low results in test 8 (training: 2%, validation: 3% and tests: 4%). These results reflect that the models trained under these configurations face underfitting issues, i.e., the performance of the trained models does not fit the proposed distribution of the Pepper harvesting processes dataset, reflecting high bias.

- According to the data from Table 5, the fastest R-CNN object detection with ShuffleNet as the feature extractor model is the one that offers low-accuracy results. The poorest results of Faster R-CNN come from test 6 (training: 2%, validation: 1% and test: 1%), while the best results correspond to test 16 (training: 81%, validation: 77% and test: 70%), which unlike the previous result, test 16 managed to fit well into the dataset of pepper harvesting processes. The faster R-CNN model might deliver results with a low level of accuracy due to its use of an RPN (Region Proposal Network) stage, which tends to suffer from insufficient adjustment for our distribution of datasets.

- The best detection results reached using the ShuffleNet network depends on the compatibility between the detection model and the hyper-parameter configuration. The Faster R-CNN model obtained its best result in test 16 (training: 81%, validation: 77% and tests: 70%). For YOLOv7, the best result is from test 18 (training: 99%, validation: 99%, and test: 99%). Additionally, for the SSD model, the best result was obtained in test 13 (training: 79%, validation: 82% and tests: 80%). Based on the results presented in Table 5, the best model for this dataset is YOLOv7 with the hyperparameter configuration of test 18. This model has a low-level bias and variance, demonstrating that the model has high generalization (low overfitting) as accuracy is barely reduced in the training, validation, and testing stages.

4.4. Comparison of Inference Times

4.5. Comparison Results with State-of-the-Art Works

4.6. Discussion

- During the implementation of object detection algorithms for pepper harvesting processes, it was observed that the YOLOv7 detection model is the architecture that stands out both in precision values and its inference times. By implementing the GoogLeNet, ResNet-18, and ShuffleNet feature extractors, the YOLOv7 model achieves an average performance of 99% during testing for all the feature extractors. This makes YOLOv7 a model capable of fulfilling the object of interest detection problem during pepper harvesting effectively. The object detection methods based on SSD also displayed high-performance results up to 91% during testing. However, they do not reach the accuracy values of YOLOv7. On the other hand, the Faster R-CNN model demonstrated to have underfitting issues for several tests that reached performances below 10%, and some punctual cases with moderate results from 39% up to 70% during testing.

- Despite the varying number of parameters across the CNNs utilized for feature extraction, no association was observed between the parameter count and the accuracy achieved by the trained models. Although ResNet-18 has more parameters than the GoogLeNet and ShuffleNet feature extractors, the results do not reflect an increase in accuracy when it is used. YOLOv7 was the model that delivered the best results in terms of accuracy scores, regardless of the feature extractor used (YOLOv7 with GoogLeNet reached up to 99.6%, YOLOv7 with ResNet-18 and ShuffleNet up to 99%). According to the results of the model, no correlation influences the accuracy of the results obtained in the model for our proposed pepper process dataset distribution. In the case of increasing the size of the dataset, this behavior might change. For future work, we will try to increase the dataset of our work to analyze this behavior and compare it with even more feature extraction methods.

- We have shown that CNN-based object detection methods may effectively identify objects of interest in pepper harvesting processes. In our work, we employed Faster R-CNN, YOLOv7, and SSD to detect human, box, pepper, pepper group, and pushcart categories. All specified object detection techniques were trained with GoogLeNet, ResNet-18, and ShuffleNet as feature extraction stages. YOLOv7 employing GoogLeNet achieved the highest performance over all the experiments, with 99% during training, 99.8% during validation, and 99.6% during testing. These findings signify a promising solution for pepper harvesting applications, including human-object action recognition, automated monitoring, and potential training tools for robotic perception applications. Furthermore, we have demonstrated a substantial enhancement relative to our findings in other studies, where typically a singular object detection method is employed across various applications, including chili pepper detection, plant disease identification, potato leaf detection, fruit detection, green pepper detection, among others.

- Considering the interference times obtained, the detector developed from YOLOv7 shows great potential for applications oriented to the detection of objects during Pepper harvesting processes in real-time, with response times ranging from 0.0175 to 0.0381 seconds when using different networks as feature extractors. This positions the model within the desired threshold of less than 0.25 seconds (in real-time), which is critical for a decision-making application in harvest-oriented environments. The SSD model also achieves fast inference times between 0.0330 and 0.0400 seconds. This makes it a viable option for scenarios that require online decision-making. On the other hand, the Faster R-CNN algorithm achieves inference times between 0.0714 and 0.0795 seconds, representing the slowest inference times of this work. Overall, the model that stands out is YOLOv7, making it the most efficient model for real-time object detection in applications oriented to object of interest detection during Pepper harvesting processes.

- We have demonstrated that it is possible to use CNN-based object detection techniques for pepper harvesting processes. However, the path to reaching a feasible monitoring system able to detect all the objects of interest in different farms is still long because our proposed system has several limitations. For example, the dataset comprised a dataset of 210 RGB images of pepper harvesting tasks from a Chilean farm, which might be insufficient for generalizing the findings to a different location. The efficacy of deep learning models based on CNNs might work better with more extensive datasets from different farms and countries. It is also important to mention that the human actions and movements during harvesting depend on each field worker’s style and individual techniques, which may vary based on their experience, physical capability, crop distribution, field characteristics, among others. The structure and specific attributes of the proposed dataset limit our understanding of the full potential. For this reason, our future works will include the study of data from more regions and countries. Moreover, demographic data from these locations may exhibit subtle variations relevant to this application. In addition, the computational complexity and reliance on CNNs necessitate the utilization of computers with graphics cards or even control cards with parallel processing capabilities, such as the Jetson, for this implementation in the field, for example, in robotics.

- For future work, extensive testing and deep hyper-parameter calibration will be performed to implement additional feature extractors to improve accuracy and confidence in our AI-based object of interest detection system for pepper harvesting processes. Moreover, other feature extraction methods can also be investigated, such as the use of Xception, MobileNet, VGGnet, and more.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- López-Barrios, J.D.; Escobedo Cabello, J.A.; Gómez-Espinosa, A.; Montoya-Cavero, L.E. Green sweet pepper fruit and peduncle detection using mask R-CNN in greenhouses. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT: Crops and livestock products – Chillies and peppers, green, 2018. Accessed online at http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/.

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, S.; Liu, P. Research on Key Algorithm for Sichuan Pepper Pruning Based on Improved Mask R-CNN. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sert, E.; Özen, M.; Ayalp, H. Leveraging Convolutional Neural Networks for Disease Detection in Vegetables: A Comprehensive Review. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 7842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstead, M.; Denman, S.; Fookes, C.; McCool, C. Fruit detection in the wild: The impact of varying conditions and cultivar. In Proceedings of the 2020 digital image computing: techniques and applications (DICTA). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–8.

- Sa, I.; Lehnert, C.; English, A.; McCool, C.; Dayoub, F.; Upcroft, B.; Perez, T. Peduncle detection of sweet pepper for autonomous crop harvesting—combined color and 3-D information. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2017, 2, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkioxari, G.; Girshick, R.; Dollár, P.; He, K. Detecting and recognizing human-object interactions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 8359–8367.

- Wan, L.; Zhu, W.; Dai, Y.; Zhou, G.; Chen, G.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, M.; He, M. Identification of Pepper Leaf Diseases Based on TPSAO-AMWNet. Plants 2024, 13, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakos, K.G.; Busato, P.; Moshou, D.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. Machine Learning in Agriculture: A Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, L.F.P.; Moreira, A.P.; Silva, M.F. Advances in Agriculture Robotics: A State-of-the-Art Review and Challenges Ahead. Robotics 2021, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Villota-Eraso, L.D.; Escobedo Cabello, J.A.; Gómez-Espinosa, A. Maturity Recognition and Fruit Counting for Sweet Peppers in Greenhouses Using Deep Learning Neural Networks. Agriculture 2024, 14, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sert, E. A deep learning based approach for the detection of diseases in pepper and potato leaves. Anadolu Tarım Bilimleri Dergisi 2021, 36, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Kurita, H.; Fukao, T.; Arihara, H.; Iwai, A. An automated fruit harvesting robot by using deep learning. Robomech Journal 2019, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, C. Real-time fruit recognition and grasping estimation for robotic apple harvesting. Sensors 2020, 20, 5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viveros Escamilla, L.D.; Gómez-Espinosa, A.; Escobedo Cabello, J.A.; Cantoral-Ceballos, J.A. Maturity recognition and fruit counting for sweet peppers in greenhouses using deep learning neural networks. Agriculture 2024, 14, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnert, C.; McCool, C.; Sa, I.; Perez, T. A sweet pepper harvesting robot for protected cropping environments. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.11920 2018. arXiv:1810.11920 2018.

- Polic, M.; Tabak, J.; Orsag, M. Pepper to fall: a perception method for sweet pepper robotic harvesting. Intelligent Service Robotics 2022, 15, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, G.J.; Liu, M.X.; Chen, C.C. The smart image recognition mechanism for crop harvesting system in intelligent agriculture. IEEE Sensors Journal 2019, 20, 2766–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Xin, Q. Extracting building boundaries from high resolution optical images and LiDAR data by integrating the convolutional neural network and the active contour model. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Wu, Y.; Bo, Y.; Yan, H. Chili pepper object detection method based on improved YOLOv8n. Plants 2024, 13, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, A.; Machavaram, R. Greenhouse capsicum detection in thermal imaging: A comparative analysis of a single-shot and a novel zero-shot detector. Next Research 2024, 1, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.T.; Pintado, C.; de la Haba, M.J.; Torres, I.; García, M.; Pérez-Marín, D. In situ ripening stages monitoring of Lamuyo pepper using a new-generation near-infrared spectroscopy sensor. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2020, 100, 1931–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, L.; Khalid, M.; Hanheide, M.; Parsons, S. Probabilistic model-checking of collaborative robots: A human injury assessment in agricultural applications. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 222, 108987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconez, J.P.; Kantor, G.A.; Cheein, F.A.A. Human–robot interaction in agriculture: A survey and current challenges. Biosystems engineering 2019, 179, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arad, B.; Kurtser, P.; Barnea, E.; Harel, B.; Edan, Y.; Ben-Shahar, O. Controlled lighting and illumination-independent target detection for real-time cost-efficient applications. the case study of sweet pepper robotic harvesting. Sensors 2019, 19, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, X.; Li, H.; Song, Q.; Zeng, F.; Zheng, J.; Ding, Z.; Kang, G.; Cai, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xu, X.; et al. YOLOv7-GCA: A Lightweight and High-Performance Model for Pepper Disease Detection. Agronomy 2024, 14, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, J.; Kim, S. CRASA: Chili Pepper Disease Diagnosis via Image Reconstruction Using Background Removal and Generative Adversarial Serial Autoencoder. Sensors 2024, 24, 6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yu, J.; Kurihara, T.; Wu, C.; Niu, Z.; Zhan, S. Pixelwise complex-valued neural network based on 1D FFT of hyperspectral data to improve green pepper segmentation in agriculture. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Ji, S.; Xuan, G.; Ren, Y.; Feng, W.; Jia, H.; Wang, Q.; He, S. Detection and analysis of chili pepper root rot by hyperspectral imaging technology. Agronomy 2024, 14, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, S. YOLOv8-CBSE: An Enhanced Computer Vision Model for Detecting the Maturity of Chili Pepper in the Natural Environment. Agronomy 2025, 15, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Hu, W.; Lan, N.; Lei, X.; Xiang, Y. Green pepper fruits counting based on improved DeepSort and optimized Yolov5s. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15, 1417682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Schafleitner, R.; Barchenger, D.W.; Lin, Y.p.; Lee, J. Evaluation of heat stress response in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) seedlings under controlled environmental conditions using a high-throughput 3D multispectral phenotyping. Scientia Horticulturae 2025, 345, 114136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, L.; Hanheide, M.; Parsons, S. Implementation of a human-aware robot navigation module for cooperative soft-fruit harvesting operations. Journal of Field Robotics 2024, 41, 2184–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, L.; Wariyapperuma, P.; Arunachalam, H.; Vasconez, J.; Hanheide, M.; Sklar, E. Robot-assisted fruit harvesting: a real-world usability study. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 20th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), 2024, pp. 2517–2523.

- Sa, I.; Ge, Z.; Dayoub, F.; Upcroft, B.; Perez, T.; McCool, C. Deepfruits: A fruit detection system using deep neural networks. sensors 2016, 16, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Samsuzzaman.; Reza, M.N.; Lee, K.H.; Ahmed, S.; Cho, Y.J.; Noh, D.H.; Chung, S.O. Image Processing and Support Vector Machine (SVM) for Classifying Environmental Stress Symptoms of Pepper Seedlings Grown in a Plant Factory. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2043.

- Han, Y.; Ren, G.; Zhang, J.; Du, Y.; Bao, G.; Cheng, L.; Yan, H. DSW-YOLO-Based Green Pepper Detection Method Under Complex Environments. Agronomy 2025, 15, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallatif, R.F.; Murad, W.; Abu-Naser, S.S. Classification of Peppers Using Deep Learning 2025.

- Guerrero-Mendez, C.; Navarro-Solís, D.; Saucedo-Anaya, T.; Lopez-Betancur, D.; Silva-Acosta, L.; Robles-Guerrero, A.; Gómez-Jiménez, S. Evaluating CNN Models and Optimization Techniques for Quality Classification of Dried Chili Peppers (Capsicum annuum L.). International Journal of Combinatorial Optimization Problems & Informatics 2024, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconez, J.P.; Admoni, H.; Cheein, F.A. A methodology for semantic action recognition based on pose and human-object interaction in avocado harvesting processes. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 184, 106057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, P.; Li, S.; Zhou, J.; Lv, K.; Feng, H. Research on instance segmentation algorithm of greenhouse sweet pepper detection based on improved mask RCNN. Agronomy 2023, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Sun, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, H.; Jiang, J. Xiaomila green pepper target detection method under complex environment based on improved YOLOv5s. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, R.; Peng, J.; Peng, H.; Hu, W.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, P. YOLO-chili: An efficient lightweight network model for localization of pepper picking in complex environments. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Xiang, J.; Liu, T.; Gao, Z.; Liao, M. Sichuan pepper recognition in complex environments: A comparison study of traditional segmentation versus deep learning methods. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yang, L.; Zhang, D. Fruit detection for strawberry harvesting robot in non-structural environment based on Mask-RCNN. Computers and electronics in agriculture 2019, 163, 104846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Zhang, D. Real-time visual localization of the picking points for a ridge-planting strawberry harvesting robot. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 116556–116568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Karkee, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yaqoob, M.; Fu, L.; Wang, S. Multi-class object detection using faster R-CNN and estimation of shaking locations for automated shake-and-catch apple harvesting. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 173, 105384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Guo, W.; Yoshioka, Y.; Ninomiya, S. On plant detection of intact tomato fruits using image analysis and machine learning methods. Sensors 2014, 14, 12191–12206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divya, S.; Panda, S.; Hajra, S.; Jeyaraj, R.; Paul, A.; Park, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Oh, T.H. Smart data processing for energy harvesting systems using artificial intelligence. Nano Energy 2023, 106, 108084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanya, V.; Subeesh, A.; Kushwaha, N.; Vishwakarma, D.K.; Kumar, T.N.; Ritika, G.; Singh, A. Deep learning based computer vision approaches for smart agricultural applications. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture 2022, 6, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatchurrahman, D.; Castillejo, N.; Hilaili, M.; Russo, L.; Fathi-Najafabadi, A.; Rahman, A. A Novel Damage Inspection Method Using Fluorescence Imaging Combined with Machine Learning Algorithms Applied to Green Bell Pepper. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.; Zhang, S.; Sun, H.; Gao, T. Research on pepper external quality detection based on transfer learning integrated with convolutional neural network. Sensors 2021, 21, 5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, Y.; Zheng, J.; Ge, Y. Faster and accurate green pepper detection using NSGA-II-based pruned YOLOv5l in the field environment. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2023, 205, 107563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, T.; Jin, H.; Siddique, M.I.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, H.; Chua, L. DIANA: A deep learning-based paprika plant disease and pest phenotyping system with disease severity analysis. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 983625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hespeler, S.C.; Nemati, H.; Dehghan-Niri, E. Non-destructive thermal imaging for object detection via advanced deep learning for robotic inspection and harvesting of chili peppers. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture 2021, 5, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconez, J.P.; Delpiano, J.; Vougioukas, S.; Cheein, F.A. Comparison of convolutional neural networks in fruit detection and counting: A comprehensive evaluation. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 173, 105348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zhao, K.; Lovell, B.C. Faster ilod: Incremental learning for object detectors based on faster rcnn. Pattern recognition letters 2020, 140, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Goudos, S. Faster R-CNN for multi-class fruit detection using a robotic vision system. Computer Networks 2020, 168, 107036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023, pp.

- Hussain, M. Yolov1 to v8: Unveiling each variant–a comprehensive review of yolo. IEEE access 2024, 12, 42816–42833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwan, T.; Anirudh, G.; Tembhurne, J.V. Object detection using YOLO: Challenges, architectural successors, datasets and applications. multimedia Tools and Applications 2023, 82, 9243–9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Srivastava, S. Object detection system based on convolution neural networks using single shot multi-box detector. Procedia Computer Science 2020, 171, 2610–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14. Springer, 2016, pp. 21–37.

- Zhou, S.; Qiu, J. Enhanced SSD with interactive multi-scale attention features for object detection. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2021, 80, 11539–11556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, A.; Verma, G.K. Convolutional neural network: a review of models, methodologies and applications to object detection. Progress in Artificial Intelligence 2020, 9, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuesheng, F.; Jian, S.; Fuxiang, X.; Yang, B.; Xiang, Z.; Peng, G.; Zhengtao, W.; Shengqiao, X. Circular fruit and vegetable classification based on optimized GoogLeNet. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 113599–113611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Huseiny, M.S.; Sajit, A.S. Transfer learning with GoogLeNet for detection of lung cancer. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and computer science 2021, 22, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabanci, K.; Aslan, M.F.; Ropelewska, E.; Unlersen, M.F. A convolutional neural network-based comparative study for pepper seed classification: Analysis of selected deep features with support vector machine. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2022, 45, e13955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, M.O.; Zahid, A. Deep learning in controlled environment agriculture: A review of recent advancements, challenges and prospects. Sensors 2022, 22, 7965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Yeom, H.G.; Lee, J.H.; Shin, W.S.; Yun, J.P.; Jeong, S.H.; Kang, J.H.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, B.C. Deep learning-based prediction of paresthesia after third molar extraction: A preliminary study. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, W.; Pan, Y.; Xu, B.; Wang, J. A real-time apple targets detection method for picking robot based on ShufflenetV2-YOLOX. Agriculture 2022, 12, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; Sun, J. Shufflenet: An extremely efficient convolutional neural network for mobile devices. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 6848–6856.

- Ma, N.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.T.; Sun, J. Shufflenet v2: Practical guidelines for efficient cnn architecture design. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 116–131.

- Vasconez, J.P.; Salvo, J.; Auat, F. Toward semantic action recognition for avocado harvesting process based on single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Automation/XXIII Congress of the Chilean Association of Automatic Control (ICA-ACCA). IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–6.

| Hyper-parameter configuration | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Learning Rate | Max Epochs | Optimizer |

| Test 1 | 0.001 | 22 | adam |

| Test 2 | 0.001 | 22 | sgdm |

| Test 3 | 0.001 | 22 | rmsprop |

| Test 4 | 0.005 | 22 | adam |

| Test 5 | 0.005 | 22 | sgdm |

| Test 6 | 0.005 | 22 | rmsprop |

| Test 7 | 0.0001 | 22 | adam |

| Test 8 | 0.0001 | 22 | sgdm |

| Test 9 | 0.0001 | 22 | rmsprop |

| Test 10 | 0.001 | 22 | adam |

| Test 11 | 0.001 | 45 | sgdm |

| Test 12 | 0.001 | 45 | rmsprop |

| Test 13 | 0.005 | 45 | adam |

| Test 14 | 0.005 | 45 | sgdm |

| Test 15 | 0.005 | 45 | rmsprop |

| Test 16 | 0.0001 | 45 | adam |

| Test 17 | 0.0001 | 45 | sgdm |

| Test 18 | 0.0001 | 45 | rmsprop |

| Training | Validation | Testing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Faster R- CNN |

Yolo v7 |

SSD | Faster R- CNN |

Yolo v7 |

SSD | Faster R- CNN |

Yolo v7 |

SSD |

| Test 1 | 83.2% | 97.8% | 51% | 83% | 93% | 46% | 81% | 99% | 48% |

| Test 2 | 55% | 2% | 3% | 42% | 1% | 3% | 51% | 1% | 2% |

| Test 3 | 70% | 84% | 4% | 67% | 71% | 3% | 66% | 70% | 1% |

| Test 4 | 3% | 31% | 2% | 2% | 30% | 2% | 2% | 38% | 1% |

| Test 5 | 80% | 6.1% | 3% | 80% | 5% | 1% | 77% | 4% | 2% |

| Test 6 | 8% | 12% | 4% | 7% | 11% | 5% | 4% | 18% | 1% |

| Test 7 | 82% | 2% | 28% | 85% | 1% | 27% | 81% | 2% | 25% |

| Test 8 | 8% | 3% | 4% | 13% | 2% | 3% | 8% | 2% | 2% |

| Test 9 | 81% | 16% | 58% | 81% | 18% | 58% | 79% | 26% | 54% |

| Test 10 | 73% | 99% | 80% | 68% | 99.8% | 82% | 72% | 99.6% | 80% |

| Test 11 | 73% | 24.4% | 4% | 64% | 16% | 3% | 69.9% | 25% | 3% |

| Test 12 | 83% | 99% | 2% | 82% | 99.8% | 2% | 79% | 94.2% | 1% |

| Test 13 | 7% | 97% | 8% | 6% | 97% | 6% | 5% | 99.9% | 4% |

| Test 14 | 87% | 62% | 7% | 86% | 74% | 7% | 83% | 56% | 6% |

| Test 15 | 4% | 90% | 4% | 2% | 77% | 4% | 3% | 82% | 3% |

| Test 16 | 88% | 60% | 57% | 92% | 29% | 55% | 85% | 52% | 52% |

| Test 17 | 19% | 6% | 4% | 26% | 5% | 4% | 21% | 3% | 5% |

| Test 18 | 89.8% | 85.9% | 76% | 87% | 80.2% | 76% | 85% | 85.5% | 74% |

| Training | Validation | Testing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Faster R- CNN |

Yolo v7 |

SSD | Faster R- CNN |

Yolo v7 |

SSD | Faster R- CNN |

Yolo v7 |

SSD |

| Test 1 | 61.2% | 95% | 88% | 62% | 95% | 91% | 48% | 94% | 89% |

| Test 2 | 67% | 6% | 57% | 64% | 5% | 58% | 68% | 4% | 59% |

| Test 3 | 3% | 93% | 88% | 2% | 92% | 91% | 1% | 96% | 89% |

| Test 4 | 5% | 24% | 77% | 5% | 23% | 80% | 4% | 34% | 78% |

| Test 5 | 86% | 2% | 87.9% | 83% | 1% | 83% | 80% | 4% | 91% |

| Test 6 | 2% | 57% | 73% | 2% | 45% | 70% | 1% | 63% | 66% |

| Test 7 | 84% | 13% | 85% | 81% | 22% | 87.3% | 81% | 7% | 89% |

| Test 8 | 29% | 2% | 1% | 23% | 1% | 6% | 25% | 2% | 4% |

| Test 9 | 81% | 10% | 84% | 82% | 15% | 87% | 77% | 7% | 85% |

| Test 10 | 53% | 99% | 88% | 42% | 99% | 91% | 45% | 99% | 89% |

| Test 11 | 85% | 6% | 76.3% | 84% | 14% | 81% | 80% | 2% | 78% |

| Test 12 | 12% | 99% | 88% | 14% | 99% | 90% | 11% | 99% | 87% |

| Test 13 | 7% | 96% | 88% | 7% | 93% | 90% | 5% | 95% | 88% |

| Test 14 | 88.2% | 86% | 88% | 88% | 85% | 94% | 82% | 85% | 91% |

| Test 15 | 5% | 95% | 88.3% | 3% | 99% | 89% | 3% | 87% | 86% |

| Test 16 | 91% | 32% | 88% | 89% | 37% | 92% | 87% | 31% | 90% |

| Test 17 | 44% | 3% | 9% | 40% | 2% | 15% | 33.5% | 3% | 15% |

| Test 18 | 87% | 49% | 87% | 86% | 51% | 92% | 85% | 41% | 89% |

| Training | Validation | Testing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Faster R- CNN |

Yolo v7 |

SSD | Faster R- CNN |

Yolo v7 |

SSD | Faster R- CNN |

Yolo v7 |

SSD |

| Test 1 | 61% | 97% | 78.8% | 64% | 97.3% | 83% | 70% | 99% | 79% |

| Test 2 | 62% | 41% | 38% | 63% | 36% | 41% | 51% | 29% | 39.3% |

| Test 3 | 51% | 99% | 75% | 47% | 97% | 76% | 51% | 97% | 71% |

| Test 4 | 4% | 98% | 76% | 4% | 92% | 81% | 3% | 97% | 76% |

| Test 5 | 2% | 85% | 71% | 1% | 74% | 74% | 1% | 90% | 69% |

| Test 6 | 8% | 82% | 76% | 7% | 49% | 79% | 4% | 58% | 76% |

| Test 7 | 66.6% | 90% | 45% | 57% | 74% | 49% | 58% | 86% | 42% |

| Test 8 | 44% | 4% | 2% | 43.5% | 3% | 3% | 42% | 4% | 4% |

| Test 9 | 65% | 92% | 46% | 66% | 78% | 47% | 56% | 93.3% | 41% |

| Test 10 | 72% | 96% | 79% | 65% | 97% | 80% | 61% | 96% | 77% |

| Test 11 | 68% | 80% | 56% | 66% | 67.3% | 53% | 66% | 84% | 50% |

| Test 12 | 48% | 99% | 79% | 51% | 97% | 82% | 39% | 99% | 79% |

| Test 13 | 9.3% | 95% | 80% | 8% | 97% | 82% | 7% | 96.5% | 80% |

| Test 14 | 8% | 97% | 78% | 7% | 92.8% | 81% | 6% | 95.6% | 78% |

| Test 15 | 9% | 82% | 78% | 10% | 88% | 79% | 7% | 83% | 78% |

| Test 16 | 81% | 98.8% | 60% | 77% | 94% | 60.2% | 70% | 96% | 55% |

| Test 17 | 46% | 3% | 11% | 37% | 2% | 14% | 46% | 3% | 12.2% |

| Test 18 | 71% | 99% | 60% | 71% | 99% | 58% | 68% | 99% | 52% |

| Detection Model | Faster R-CNN | YOLOv7 | SSD |

|---|---|---|---|

| GoogLeNet (s) | 0.0714 | 0.0175 | 0.0330 |

| ResNet-18 (s) | 0.1477 | 0.0203 | 0.0258 |

| ShuffleNet (s) | 0.0795 | 0.0381 | 0.0400 |

| Paper | Objective or Task |

Data base |

Algorithm | Feature Extractor |

mAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hespeler et al [55] |

Chili peppers detection via thermal imaging |

112 images & 112 thermal images |

Yolov3 & Mask R-CNN |

Mask R-CNN |

97% |

| Ilyas et al[54] |

Deep learning for Pepper plant disease |

6000 images | DCNN | DCNN | 91.7% |

| Sert et al [12] |

Detect pepper and potato leaves |

544 images | Faster R-CNN |

GoogLeNet | 98% |

| Zhang et al [47] |

Multi-class object detection for harvesting |

675 images | Faster R-CNN |

Alexnet, VGG16 y VGG19 |

82% |

| Halstead et al [5] |

Fruit Detection in the Wild |

522 images | Faster R-CNN & Mask R-CNN |

Mask R-CNN |

90% |

| Nan et al [53] |

Green pepper detection for pruned |

1100 images | Yolov5I & NSGA II |

NSGA II |

81.4% |

| Sa et al [6] |

Peduncle Detection of Pepper for Harvesting |

72 images | Supervised learning |

Supervised learning |

71% |

| Arad et al [25] |

Lighting Target Detection for Sweet Pepper |

156 scenes & 468 images |

SSD & FNF |

Flash No Flash |

84.07% |

| Yu et al [46] |

Visual Localization of the Picking Points for Planting |

100 images | R-Yolo | MobileNet V1 |

84.35% |

| Sa et al [35] |

Fruit Detection with DL |

122 images | Faster R-CNN |

VGG 16 |

83.8% |

|

This Work |

Multi-class object detection for Pepper harvesting |

420 images | YOLOv7, Faster R-CNN & SSD |

GoogLeNet, ResNet-18 & ShuffleNet |

Yolo: 99% Faster : 87% SSD: 91% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).