1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) represents a prevalent sleep-related breathing disorder (SDB), fundamentally characterized by recurrent episodes of upper airway collapse. This physiological disturbance leads to a discernible reduction in inspiratory airflow, manifesting either as a complete cessation (apnea) or a partial diminution (hypopnea). The estimated prevalence of OSA within the general population exhibits considerable variability, contingent upon a multitude of factors. These include the specific attributes of the studied cohort (e.g., BMI, ethnic), the methodologies employed for the assessment of SDB, the operational definitions of the disease state (e.g., the criteria for hypopnea), and the threshold of the Apnea/Hypopnea Index (AHI) utilized for OSA diagnosis.

A comprehensive investigation conducted by Benjafield and colleagues in 2019 [

1] projected that approximately one billion adults aged between 30 and 69 years globally may be afflicted by obstructive sleep apnea. Furthermore, their analysis indicated that the number of individuals experiencing moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea, a condition for which therapeutic intervention is generally indicated, approaches 425 million. Obstructive sleep apnea is a ubiquitous disorder that can manifest with or without overt clinical symptomatology. Irrespective of symptomatic presentation, individuals diagnosed with OSA exhibit an elevated susceptibility to a range of adverse clinical out- comes, especially neurocognitive and cardiovascular sequelae, underscoring its clinical importance.

Despite its considerable prevalence and impact, obstructive sleep apnea was formally recognized relatively recently, in 1965, by Gastaut et al. [

2]. Their seminal work provided the initial evidence demonstrating that the cessation of respiration during sleep was attributable to an obstruction of the upper airway. Subsequently, in 1976, Guilleminault and co-workers [

3] introduced the terms "sleep apnea syndrome" and "obstructive sleep apnea syndrome" (OSAS) to emphasize that airway obstruction during sleep was not solely confined to individuals with obesity. The first documented instances of OSA reversal through the application of positive airway pressure (PAP) were reported in 1981 [

4]. Since these initial observations, the scientific understanding of the underlying causes of OSA has progressively advanced, and various therapeutic modalities have begun to emerge.

1.1. Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Morbidity

Patients afflicted with OSA, particularly in its moderate or severe and untreated forms, face an increased risk of developing systemic hypertension, coronary artery disease, cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, and cerebrovascular events such as stroke [

5]. The recurrent episodes of upper airway obstruction during sleep are associated with intermittent hypoxemia, potential hypercapnia, alterations in intrathoracic pressure dynamics, and recurrent microarousals. The resultant hemodynamic, autonomic, and metabolic perturbations, coupled with systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, are implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases in the context of OSA [

6].

OSA is consistently linked to a significant augmentation of sympathetic nervous system activity during sleep. This heightened sympathetic tone contributes to the attenuation of the normal nocturnal decline in blood pressure and heart rate, ultimately predisposing individuals to systemic hypertension [

7]. The increased sympathetic activity appears to be mediated through a complex interplay of mechanisms, including chemoreflex stimulation triggered by hypoxemia and hypercapnia, baroreflex modulation, pulmonary afferent signaling, impaired venous return to the heart, alterations in cardiac output, and potentially the arousal response itself. Endothelial dysfunction, potentially stemming from intermittent hypoxemia, may also play a significant role in this process [

8].

OSA has been independently associated with an elevated risk of ischemic stroke, even after accounting for traditional vascular risk factors [

9,

10]. Several potential mechanisms may underlie this increased stroke risk in OSA patients. One plausible explanation involves the reduction in cerebral blood flow velocity resulting from the negative intrathoracic pressure typically generated during an obstructive apneic event. Alternatively, the cere- brovascular dilatory responses to hypoxia may be blunted in individuals with OSA due to the effects of intermittent hypoxia, oxidant-mediated endothelial dysfunction, increased sympathetic activity, and impaired cerebral vasomotor reactivity to carbon dioxide [

11].

These recurrent reductions in cerebral blood flow velocity can then precipitate ischemic changes, particularly in vulnerable border-zone areas and terminal arterial territories, espe- cially in patients with compromised hemodynamic reserve (e.g., those with intracranial arterial stenosis) [

12]. Furthermore, OSA may exacerbate pre-existing cerebrovascular abnormalities or other established risk factors for stroke [

9]. Supporting this notion, patients with OSA exhibit a higher prevalence of systemic hypertension, heart disease, impaired vascular endothelial function, accelerated atherogenesis, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, prothrombotic coagulation shifts, proinflammatory states, and increased platelet aggregation [

13].

Pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure are also recognized complications of OSA. Classically, OSA is associated with group 3 pulmonary hypertension, particularly in instances where OSA coexists with obesity hypoventilation syndrome or another condition causing daytime hypoxemia, such as chronic lung disease [

14,

15].

1.2. Neuropsychiatric Dysfunction

OSA can induce or exacerbate deficits in attention, memory, and overall cognitive function. These impairments can collectively lead to compromised executive function, consequently elevating the propensity for errors and accidents [

16,

17]. Notably, the incidence of motor vehicle accidents is two to three times higher among individuals with OSA compared to those without the disorder [

18]. Additional neuropsychiatric manifestations associated with OSA include increased mood lability and irritability, as well as a higher prevalence of depression, psychosis, and sexual dysfunction [

19,

20].

1.3. Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes

Individuals with OSA demonstrate an increased prevalence of insulin resistance, as well as type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications [

21]. While this association may be partially explained by shared risk factors such as obesity, numerous studies have reported an independent correlation between OSA severity, insulin resistance, and the development of type 2 diabetes [

22,

23,

24]. In patients with the metabolic syndrome, OSA has been independently linked to elevated glucose and triglyceride levels, as well as increased markers of inflammation, arterial stiffness, and atherosclerosis. These findings suggest that OSA may exacerbate the cardiometabolic risks attributed to obesity and the metabolic syndrome [

25].

1.4. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)

Patients with OSA, particularly those with severe OSA characterized by nocturnal hypoxemia and endothelial dysfunction, exhibit a two- to threefold increased prevalence of NAFLD. This association appears to be independent of shared risk factors such as obesity [

26].

1.5. Miscellaneous

Emerging evidence suggests that individuals with OSA may have a higher risk of developing gout compared to those without OSA [

27]. Furthermore, a large retrospective study based on a French cohort indicated a potential association between cancer and nocturnal hypoxemia in patients undergoing investigation for OSA [

28]. Another study proposed a slight increase in the risk of unprovoked venous thromboembolism in OSA patients experiencing severe nocturnal hypoxemia [

29].

Individuals diagnosed with OSA, especially those with moderate to severe manifesta- tions of the condition who do not receive therapeutic intervention, demonstrate a markedly increased vulnerability to a spectrum of detrimental clinical sequelae. As highlighted by accumulating evidence, the heightened oxidative stress resulting from the characteristic intermittent hypoxia in OSA is increasingly recognized as a pivotal factor in the pathogenesis of the various comorbidities observed in this disorder. Consequently, the primary objective of this narrative review was to comprehensively investigate the intricate mechanisms of oxidative stress and elucidate their complex interplay in the development and progression of OSAS.

2. Materials and Methods

A comprehensive literature search was executed across several prominent electronic databases, namely PubMed, Cochrane Library, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, to identify pertinent studies for this narrative review.

For the databases PubMed/Medline, Cochrane Library, Scopus, and Web of Science, a targeted search strategy was employed utilizing Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and Boolean operators. The specific search syntax implemented was "(OSA OR OSAS) AND (free radical OR oxidative stress OR reactive oxygen species OR ROS)". To ensure the relevance and accessibility of the retrieved literature, the search was constrained to articles published in the English language for which full-text versions were available. The initial phase of article selection involved a thorough examination of titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant publications. Furthermore, the reference lists of identified articles of interest were scrutinized to uncover additional pertinent literature that may not have been captured by the primary database searches. Two independent researchers (identified as AM and SD) screened the titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles, with a particular emphasis on those published in journals ranked within the first quartile (Q1) of their respective subject categories. Any discrepancies arising during this initial screening process were resolved through collegial discussion and mutual agreement on the articles warranting full-text review.

For the Google Scholar database, a more streamlined search syntax, "OSA oxidative stress", was utilized. Similar to the other databases, the search was limited to articles available in English with full-text access. To optimize the efficiency of the initial screening process, the results were prioritized based on citation count, with studies exhibiting the highest citation scores being reviewed first. The same two researchers (AM and SD) independently evaluated the titles and abstracts of the articles retrieved from Google Scholar. Any disagreements encountered during this stage were resolved through collaborative discussion to determine which articles would proceed to full-text assessment.

Following the initial retrieval and screening phases, duplicate records were removed to ensure the uniqueness of the identified literature. Subsequently, the full-text versions of the remaining articles were independently assessed for eligibility by the two researchers. Once again, any disagreements regarding the inclusion or exclusion of specific articles were resolved through comprehensive discussion and the establishment of a consensus.

It is important to explicitly state that this narrative review is predicated upon the synthesis of previously conducted studies and does not encompass any original research involving animal subjects undertaken by the authors of this manuscript. It should be noted, however, that some of the studies cited herein include analyses or investigations involving human participants, which were conducted and completed prior to the commencement of the present work.

3. OSAS and Intermittent Hypoxia: The Main Driver of Oxidative Stress

OSAS is marked by repeated episodes during sleep where the upper airway becomes 169 partially or completely blocked. This mechanical obstruction disrupts normal breathing and 170 sets off a chain of physiological responses throughout the body (

Figure 1). These episodes 171 often involve reduced or halted airflow despite continued effort to breathe, leading to 172 repeated drops in oxygen levels (intermittent hypoxemia) and frequent sleep disruptions 173 (arousal) [

30,

31]. Over time, these disturbances can lead to a wide range of systemic health 174 issues.

During an apnea episode, the body attempts to inhale against a blocked airway, creating strong negative pressure inside the chest. These pressure swings can affect car- diovascular function by increasing the release of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), raising left ventricular transmural pressure, and impairing the heart’s ability to fill properly. This ultimately puts more strain on the heart by increasing both preload and afterload. At the same time, the repeated oxygen drops cause an imbalance between the heart’s oxygen needs and the amount actually delivered, which is further worsened by limited blood flow. In response to low oxygen, high carbon dioxide, and frequent arousals from sleep, the sympathetic nervous system becomes overactive-tightening blood vessels and increasing both heart rate and blood pressure.

One of the hallmark features of OSAS is the repeated pattern of intermittent hypoxemia, which drives the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to oxidative stress [

32].

This intermittent drop-and-rebound pattern in oxygen levels is strikingly similar to what happens in ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, where tissue damage is caused not just by a lack of oxygen but also by its sudden return. In OSAS, each breathing pause followed by reoxygenation mimics this cycle, promoting ROS production through similar mechanisms [

33,

34].

ROS are unstable molecules that can damage key cellular components like DNA, proteins, and lipids. This can lead to inflammation and broader tissue injury [

35]. Additionally, the low oxygen environment in OSAS triggers the release of proinflammatory substances, creating a chronic, low-level inflammatory state. This further disrupts metabolism and encourages platelet clumping, both of which raise the risk for cardiovascular problems [

36]. Together, oxidative stress and inflammation are now seen as central to the complex disease process of OSAS [

37]. Oxidative stress arises when the production of free radicals like ROS surpasses the body’s antioxidant defenses. Inflammation, in turn, is a biological response to these and other stressors-one that can itself be triggered by oxidative stress, creating a feedback loop that fuels ongoing damage.

Apnea events usually end when the sleeper briefly wakes up–either partially or fully–due to growing chemical and mechanical cues from the body, such as falling oxygen levels, rising CO2, and the increased effort to breathe. While these arousals are necessary to resume breathing, they also disrupt the normal sleep cycle, contributing to sleep fragmentation and adding to the overall burden of the disease.

4. Molecular Mechanisms of Free Radical Generation in OSAS

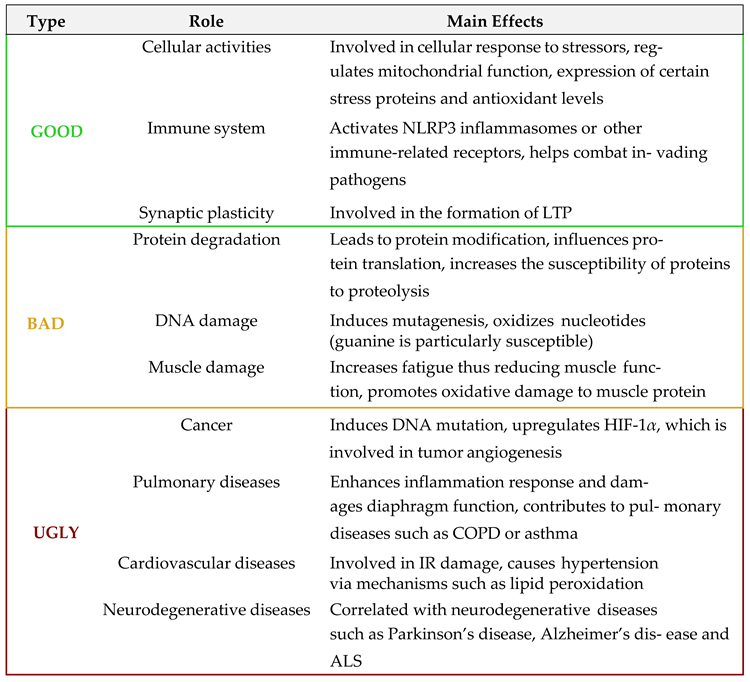

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are chemically reactive molecules derived from oxygen metabolism, routinely produced within biological systems. Although ROS are widely recognized for their potential to cause cellular damage–affecting lipids, proteins, nucleic 212 acids, and other macromolecules–often referred to as their "bad" or "ugly" effects, they also 213 serve crucial functions in the regulation of numerous physiological processes, representing 214 their "good" aspect [

33,

38,

39] (

Table 1). This dual nature of ROS, often likened to a double- 215 edged sword, underscores the importance of maintaining a finely tuned balance between 216 their production and elimination.

Superoxide anion (O

2 – ) is commonly the initial ROS formed during aerobic metabolism and can be further converted into hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) and, subsequently, into hy-droxyl radicals (OH – ), which are among the most reactive and cytotoxic ROS [

33]. Theseconversions are often facilitated by the presence of transition metals, particularly iron(Fe

2+) and copper (Cu+), via Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions. In immune cells such asneutrophils, hypochlorous acid (HOCl) is generated through the activity of myeloperoxidase, contributing to microbial killing. Moreover, the reaction of O

2 – with nitric oxide(NO)–produced by nitric oxide synthase (NOS)–yields peroxynitrite (ONOO – ), a potentoxidant capable of inducing significant biomolecular damage [

40].

While superoxide is generally the most abundant ROS, hydroxyl radicals are consid-ered the most reactive and destructive. Lipid membranes are particularly susceptible toROS-mediated damage, especially via hydroxyl radical-induced lipid peroxidation, whichcan initiate chain reactions that compromise membrane integrity [

41,

42]. DNA is also acritical target; ROS can induce base modifications, strand breaks, and sugar backbonecleavage. The formation of 8-hydroxyguanine (8-OH-G) is frequently used as a biomarkerof oxidative DNA damage [

43]. Similarly, proteins and small-molecule antioxidants suchas glutathione (GSH) are vulnerable to ROS, leading to impaired cellular redox buffering,mitochondrial dysfunction, and diminished contractile and neuronal function [

40].

Endogenously, mitochondria and NADPH oxidases (NOX) represent the principalsources of ROS. In mitochondria, ROS arise as by-products of electron leakage from the electron transport chain during oxidative phosphorylation. NOX enzymes, localized in variouscellular membranes including those of the sarcolemma, sarcoplasmic reticulum, and transverse tubules, also contribute significantly to ROS generation. Other intracellular sources include xanthine oxidase, uncoupled NOS, and organelles such as peroxisomes and the endoplasmic reticulum. Additionally, numerous immune and vascular cell types—including macrophages, endothelial cells, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes—are known to produce ROS, especially under stress conditions. Exogenous factors such as tobacco smoke, environmental toxins, ionizing radiation, and hypoxic environments further exacerbate ROS levels.

To preserve cellular integrity and function, cells possess an array of antioxidant defense systems that maintain redox homeostasis. These include enzymatic antioxidantssuch as superoxide dismutases (SODs), catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and hemeoxygenase-1, as well as non-enzymatic antioxidants like vitamin C, vitamin E, carotenoids,polyphenols, and glutathione. Collectively, these systems modulate oxidative stress andregulate redox-sensitive signaling pathways essential for processes like proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. ROS also influence the activity of several transcription factors,including hypoxia-inducible factor-1

α (HIF-1

α), nuclear factor

κB (NF-

κB), activator protein-1 (AP-1), and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), all of which play roles instress responses and inflammation [

44,

45].

Among antioxidant enzymes, SOD is especially critical for neutralizing superoxideby catalyzing its conversion into H

2O

2 and molecular oxygen. There are three majorisoforms of SOD: the cytosolic Cu/Zn-SOD (SOD1), mitochondrial Mn-SOD (SOD2), andextracellular SOD (SOD3). SOD2, in particular, plays a key role in protecting mitochondrialintegrity during periods of oxidative stress or ischemia-reperfusion injury [

46]. Hydrogenperoxide generated by SOD is further detoxified into water by catalase or GPx, preventingthe formation of more reactive species such as OH– .

Glutathione, a tripeptide composed of glutamate, cysteine, and glycine, representsthe most abundant intracellular non-enzymatic antioxidant. It plays diverse roles inredox homeostasis, including scavenging ROS, detoxifying hydrogen peroxide and lipidperoxides, and maintaining protein thiol groups in their reduced states. During theseprocesses, GSH is oxidized to glutathione disulfide (GSSG), which can be recycled backto GSH by glutathione reductase. Within the nucleus, GSH helps regulate DNA repairenzymes by maintaining their functional redox state. The cellular GSH/GSSG ratio iswidely accepted as an indicator of oxidative stress and redox status [

45].

In summary, while ROS are often viewed through the lens of cellular injury, they arealso indispensable signaling molecules under physiological conditions. Their effects arehighly context-dependent, varying across cell types, tissue environments, and the severityof oxidative stimuli. In conditions like OSAS, the interplay between ROS production andantioxidant defense is particularly intricate, with evidence suggesting that compensatoryupregulation of antioxidant pathways occurs alongside elevated oxidative stress. Thenet outcome hinges on the dynamic balance between pro-oxidant and antioxidant forces,ultimately influencing disease progression and therapeutic response.

5. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in OSAS

Oxidative stress and subsequent oxidant-induced damage are commonly induced bypathological conditions such as ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury and inflammation, bothof which disrupt the delicate equilibrium of the redox system. Intermittent hypoxia (IH), ahallmark of OSAS, activates various cellular components–including leukocytes, platelets,and endothelial cells–shifting them towards a proinflammatory state. This activationenhances the production of ROS, inflammatory cytokines, and adhesion molecules [

33].These interconnected molecular events culminate in endothelial damage, contributing tooxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction [

47].

Biomarkers indicative of oxidative stress and antioxidant imbalance have been de-tected primarily in the blood and other body fluids, such as urine and saliva.

Elevated levels of NF-

κB has been linked to OSAS due to intermittent hypoxia [

37]:NF-

κB represents a family of inducible transcription factors, which regulates a large arrayof genes involved in different processes of the immune and inflammatory responses, socytokines–such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-12, TNF-

α– and chemokines, involved in various inflamma-tory processes are consequently increased [

48]. Therefore, high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP),traditionally an acute-phase reactant and inflammatory marker, has also emerged as apotential oxidative stress biomarker. Elevated hsCRP levels have been positively correlatedwith OSAS severity parameters, such as the AHI, oxygen desaturation index (ODI), and thepercentage of total sleep time with oxygen saturation below 90% (TSpO

2 < 90%) [

36,

49,

50,

51]. Biological membranes are particularly vulnerable to damage from free radicals be- cause the unsaturated lipids within them are highly susceptible to oxidation. This process,known as lipid peroxidation, involves the reaction of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs)present in cellular membrane phospholipids with oxygen, leading to the formation of lipidhydroperoxides. Lipid peroxidation has been a subject of extensive study in OSAS, withplasma and serum markers being the most commonly analyzed indicators. Markers havealso been detected in exhaled breath condensates [

52,

53]. Among the primary end-productsof lipid peroxidation are compounds such as isoprostanes, isofurans, and malondialdehyde(MDA), each arising from distinct oxidative processes involving PUFAs. Isoprostanes andisofurans result from the non-enzymatic oxidation of arachidonic acid (AA) and docosahex-aenoic acid (DHA), respectively. Notably, F2-isoprostanes are prostaglandin-like moleculesthat emerge through free radical-induced peroxidation of AA within phospholipids, oc- 311 curring both in vivo and in vitro. Unlike classical prostaglandins, their formation does 312 not require cyclooxygenase activity. Initially integrated within membrane phospholipids, 313 these compounds are subsequently liberated into the circulation. Compared to other lipid 314 peroxidation products, F2-isoprostanes exhibit relatively greater stability and lower reac- 315 tivity [

54]and their levels in biological fluids has been correlated to oxidative stress under 316 different pathophysiologic conditions, including OSAS [

53,

55].

Malondialdehyde (MDA), a well-characterized low-molecular-weight aldehyde, is another significant lipid peroxidation by-product. Due to its high reactivity, MDA readily forms adducts with nucleic acids and proteins, contributing to cellular toxicity. The thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay is widely employed to quantify MDA levels,although it also detects other lipid peroxides. TBARS concentrations are commonly used asindicators of oxidative lipid damage and have shown a positive correlation with clinicalmeasures of OSAS severity, such as the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and the oxygendesaturation index (ODI) [

54,

56].

As plasma proteins are one the first target of free radicals, the detection of advancedoxidation protein products (AOPP) in biologic fluids can be an optimal strategy, as AOPPs,which represent oxidatively modified proteins, serve as indicators of both oxidative stressand inflammatory processes [

54,

57]. AOPPs are considered more stable than lipid oxidationmarkers [

58]. There is a significant correlation between circulating AOPP levels and markersof disease severity such as AHI, ODI, and TSpO

2 < 90%. Moreover, patients with moderateto severe OSAS displayed significantly higher AOPP concentrations compared to thosewith mild or no disease [

59,

60,

61].

Another oxidative stress biomarker, 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), reflectsoxidative damage to DNA. Increased urinary excretion of 8-OHdG has been observed inindividuals with severe OSAS, with positive associations reported between 8-OHdG levelsand AHI, ODI, and TSpO

2 < 90% [

62].

Superoxide dismutase (SOD), a crucial antioxidant enzyme that catalyzes the dismuta-tion of superoxide radicals, shows diminished activity in OSAS patients relative to healthycontrols, indicating compromised antioxidant defense [

63].

Similarly, the thioredoxin (Trx) system—comprising Trx, NADPH, and thioredoxinreductase (TrxR)—is involved in maintaining redox homeostasis and regulating geneexpression. Trx concentrations have been positively associated with OSAS severity, asreflected by increased AHI and decreased oxygen saturation levels [

64,

65].

Although numerous genetic polymorphisms have been implicated in OSAS patho-genesis, none have achieved validation as diagnostic or screening tools in clinical settings. Likewise, while microRNAs hold diagnostic potential, they have not yet been integrated into clinical practice due to the absence of robust validation studies [

37].

At present, the most robust biomarkers of oxidative stress in OSAS include hsCRP,thioredoxin, malondialdehyde, AOPPs, and 8-OHdG. Despite numerous efforts to identifyreliable markers for diagnosis and disease severity, the current body of evidence has notyielded consistent or clinically applicable results [

36,

37,

51,

66].

6. Discussion

More than two decades ago, the involvement of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the pathophysiology of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) was largely hypothetical. Early theories proposed that recurrent hypoxia during sleep leads to elevated levels of free radicals, which in turn contribute to inflammation and the development of atherosclerosis [

67]. While considerable progress has since been made in understanding the biological implications of oxidative stress in OSAS, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy remains the only well-established intervention with proven antioxidant effects. By restoring normal nocturnal oxygen saturation, CPAP disrupts the molecular pathways leading to 361 oxidative damage, thereby modulating the expression of various pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic mediators [

53,

68,

69,

70,

71].

Given this context, the potential of pharmacological antioxidant therapies in OSAS should be approached cautiously. To date, only a limited number of studies have evaluated antioxidant agents as therapeutic options aimed at mitigating oxidative stress in OSAS patients, and their clinical efficacy remains uncertain.

An investigation conducted by Sadasivam et al. [

72] evaluated the effects of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) as an antioxidant therapy in individuals with OSAS. In this study, participants received oral NAC at a dosage of 600 mg three times daily over a 30-day period. NAC serves as a precursor for glutathione synthesis and has demonstrated superior antioxidant properties compared to other agents, not only by neutralizing reactive oxygen species such as superoxide radicals, but also by enhancing endogenous glutathione production—a key intracellular antioxidant. Additionally, NAC is frequently utilized in clinical settings to manage conditions marked by systemic inflammation. To assess oxidative stress and antioxidant response, the study measured lipid peroxidation levels, which showed a statistically significant reduction in the NAC-treated group compared to the control group (

p < 0.001). Concurrently, glutathione concentrations increased significantly in treated individuals but remained unchanged in controls (

p < 0.001). Beyond biochemical outcomes, improvements were also noted in sleep-related parameters, including sleep architecture, efficiency, respiratory function, and snoring. These findings suggest that a one-month course of NAC may be beneficial in OSAS patients.

Grebe et al. [

73] investigated, instead, the impact of intravenous vitamin C administration on endothelial function in patients with OSAS. Vitamin C was selected due to its well-documented antioxidant properties and its beneficial effects on endothelial function in conditions characterized by elevated oxidative stress, such as diabetes mellitus, hyper-cholesterolemia, hypertension, and heart failure. The underlying mechanism involves a reduction in circulating reactive oxygen species and the restoration of nitric oxide bioavailability, thereby contributing to vascular homeostasis. Endothelial function was assessed noninvasively through ultrasound measurement of brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD), a validated indicator of endothelial function. This technique involves evaluating the change in arterial diameter in response to increased shear stress following transient forearm ischemia. The study found a significant enhancement in brachial artery flow in OSAS patients following vitamin C administration, an effect not observed in the control group (

p < 0.01). Based on these findings, the authors concluded that vitamin C may improve vascular function in individuals with OSAS and could potentially serve as a supplementary antioxidant treatment in the management of the condition.

Allopurinol, widely prescribed for its urate-lowering effects in conditions such as gout, has also drawn attention for its antioxidant properties: in addition to inhibiting xanthine oxidase, allopurinol has been shown to reduce lipid peroxidation and scavenge free radicals. Although current evidence primarily stems from preclinical models, a study conducted in rats demonstrated a marked reduction in lipid peroxidation products following allopurinol treatment [

74]. These findings suggest a potential role for allopurinol in modulating oxidative stress, warranting further investigation in clinical settings involving human subjects.

Notably, we didn’t found any studies that specifically explore the potential relationship between OSA and acetylsalicylic acid (ASA). Beyond its established antiplatelet effects, ASA has been reported to possess notable antioxidant properties, including free radical scavenging activity [

75,

76]. ASA has been shown to protect low-density lipoproteins (LDL) from oxidative modification, safeguard vascular tissues from reactive oxygen species, and inhibit protein oxidation through acetylation of lysine residues or direct neutralization of hydroxyl radicals. Some of these antioxidant mechanisms are thought to involve the modulation of gene expression, such as the suppression of the transcription factor NF-

κB, which plays a pivotal role in inflammatory signaling pathways. Evidence from both in vitro and in vivo studies highlights the multifaceted antioxidant actions of ASA, suggesting that it may exert protective effects at various physiological levels [

77]. Given these findings, we believe ASA may represent a promising candidate for antioxidant therapy in OSA, particularly in patients showing the so-called "aspirin-resistant" phenotype [78]; however, clinical studies in human populations are required to confirm its efficacy and safety in this context.

7. Conclusions

Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome is not solely a disorder of sleep-related breathingbut also exerts profound systemic effects. The recurring episodes of oxidative stressand intermittent hypoxia associated with OSAS contribute to endothelial dysfunction,metabolic dysregulation, systemic inflammation, and an increased risk of cardiovascularcomplications.

Biomarkers indicative of oxidative stress have shown potential in evaluating disease severity and monitoring individual responses to therapy. However, none of these biomarkers have yet achieved universal acceptance for routine use in clinical settings. Regardingtreatment, CPAP remains the only widely approved intervention. In addition to its primaryrole in maintaining airway patency, CPAP has demonstrated the ability to reverse severalmolecular and physiological abnormalities associated with the condition.

Despite CPAP’s effectiveness, residual dysfunctions often persist even after noctur-nal oxygenation is normalized. In such cases, pharmacological interventions may play avaluable role. Among these, antioxidant therapies are still in the early stages of development, yet several compounds have shown promising results in preliminary studies and warrant further investigation. It is plausible that, in the future, antioxidants could serve asadjunctive therapies to enhance the management of OSAS.

In conclusion, further research is essential to identify novel biomarkers through ad-vanced diagnostic methodologies and to develop new pharmacological treatments. Theseinnovations could offer additional therapeutic benefits beyond those achieved by CPAPalone, ultimately improving patient outcomes in OSAS management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D. and A.M.; Methodology, A.M., A.P. and V.N.Q.; Software, A.M. and A.P.; Validation, P.C. and G.E.C.; Investigation, Z.L. and V.N.Q.; Resources, A.B., S.D. and Z.L.; Data curation, A.P. and S.D.; Writing original draft, A.M. and S.D.; Writing review editing, P.C. and A.B.; Supervision, S.D. and G.E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy and ethical considerations, I can provide the dataset supporting the reported results upon request. Interested parties can contact me directly via email to request access.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Benjafield, A.V.; Ayas, N.T.; Eastwood, P.R.; Heinzer, R.; Ip, M.S.M.; Morrell, M.J.; Nunez, C.M.; Patel, S.R.; Penzel, T.; Pépin, J.L.; et al. Estimation of the Global Prevalence and Burden of Obstructive Sleep Apnoea: A Literature-Based Analysis. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2019, 7, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastaut, H.; Tassinari, C.A.; Duron, B. Polygraphic Study of the Episodic Diurnal and Nocturnal (Hypnic and Respiratory) Manifestations of the Pickwick Syndrome. Brain Research 1966, 1, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilleminault, C.; Tilkian, A.; Dement, W.C. The Sleep Apnea Syndromes. Annual Review of Medicine 1976, 27, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, C.E.; Issa, F.G.; Berthon-Jones, M.; Eves, L. Reversal of Obstructive Sleep Apnoea by Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Applied through the Nares. Lancet (London, England) 1981, 1, 862–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, T.D.; Floras, J.S. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea and Its Cardiovascular Consequences. Lancet (London, England) 2009, 373, 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61622-0. . American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2023, 208, 802–813. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202209-1808OC.

- Carratù, P.; Di Ciaula, A.; Dragonieri, S.; Ranieri, T.; Ciccone, M.M.; Portincasa, P.; Resta, O. Relationships between Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome and cardiovascular risk in a naïve population of southern Italy. Int J Clin Pract 2021, 75, e14952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seif, F.; Patel, S.R.; Walia, H.; Rueschman, M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Gottlieb, D.J.; Lewis, E.F.; Patil, S.P.; Punjabi, N.M.; Babineau, D.C.; et al. Journal of Sleep Research 2013, 22, 443–451. [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, P.; Schirosi, G.; Clemente R.; Battista, L.; Serio, G.; Boniello, E.; Carratù, P.; Lacedonia, D.; Federico, F.; Resta, O. Severe obstructive sleep apnoea exacerbates the microvascular impairment in very mild hypertensives Eur J Clin Invest 2008 Oct;38(10):766-73. [CrossRef]

- Hermann, D.M.; Bassetti, C.L. Role of Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Sleep-Wake Disturbances for Stroke and Stroke Recovery. Neurology 2016, 87, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudin, A.E.; Pun, M.; Yang, C.; Nicholl, D.D.M.; Steinback, C.D.; Slater, D.M.; Wynne-Edwards, K.E.; Hanly, P.J.; Ahmed, S.B.; Poulin, M.J. Cyclooxygenases 1 and 2 Differentially Regulate Blood Pressure and Cerebrovascular Responses to Acute and Chronic Intermittent Hypoxia: Implications for Sleep Apnea. Journal of the American Heart Association 2014, 3, e000875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, S.; Spengos, K.; Hennerici, M. Acceleration of Cerebral Blood Flow Velocity in a Patient with Sleep Apnea and Intracranial Arterial Stenosis. Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung 2002, 6, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, V.K.; White, D.P.; Amin, R.; Abraham, W.T.; Costa, F.; Culebras, A.; Daniels, S.; Floras, J.S.; Hunt, C.E.; Olson, L.J.; et al. Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: An American Heart Association/American College Of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council On Cardiovascular Nursing. In Collaboration with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Center on Sleep Disorders Research (National Institutes of Health). Circulation 2008, 118, 1080–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, K.; Roberts, K.; Manning, P.; Manley, C.; Hill, N.S. OSA and Pulmonary Hypertension: Time for a New Look. Chest 2015, 147, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.; Chaouat, A.; Schinkewitch, P.; Faller, M.; Casel, S.; Krieger, J.; Weitzenblum, E. The Obesity-Hypoventilation Syndrome Revisited: A Prospective Study of 34 Consecutive Cases. Chest 2001, 120, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, T.; Palta, M.; Dempsey, J.; Peppard, P.E.; Nieto, F.J.; Hla, K.M. Burden of Sleep Apnea: Rationale, Design, and Major Findings of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. WMJ: official publication of the State Medical Society of Wisconsin 2009, 108, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wallace, A.; Bucks, R.S. Memory and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Meta-Analysis. Sleep 2013, 36, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, C.F.P. Sleep Apnea, Alertness, and Motor Vehicle Crashes. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2007, 176, 954–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, A.G.; Perry, G.S.; Chapman, D.P.; Croft, J.B. Sleep Disordered Breathing and Depression among U.S. Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005-2008. Sleep 2012, 35, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaithe, M.; Bucks, R.S. Executive Dysfunction in OSA before and after Treatment: A Meta-Analysis. Sleep 2013, 36, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendzerska, T.; Gershon, A.S.; Hawker, G.; Tomlinson, G.; Leung, R.S. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Incident Diabetes. A Historical Cohort Study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2014, 190, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjabi, N.M.; Shahar, E.; Redline, S.; Gottlieb, D.J.; Givelber, R.; Resnick, H.E.; Sleep Heart Health Study Investigators. Sleep- 509 Disordered Breathing, Glucose Intolerance, and Insulin Resistance: The Sleep Heart Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology 510 2004, 160, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togeiro, S.M.; Carneiro, G.; Ribeiro Filho, F.F.; Zanella, M.T.; Santos-Silva, R.; Taddei, J.A.; Bittencourt, L.R.A.; Tufik, S. Con- sequences of Obstructive Sleep Apnea on Metabolic Profile: A Population-Based Survey. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 2013, 21, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, B.D.; Grote, L.; Ryan, S.; Pépin, J.L.; Bonsignore, M.R.; Tkacova, R.; Saaresranta, T.; Verbraecken, J.; Lévy, P.; Hedner, J.; et al. 515 Diabetes Mellitus Prevalence and Control in Sleep-Disordered Breathing: The European Sleep Apnea Cohort (ESADA) Study. 516 Chest 2014, 146, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drager, L.F.; Togeiro, S.M.; Polotsky, V.Y.; Lorenzi-Filho, G. Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Cardiometabolic Risk in Obesity and the Metabolic Syndrome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2013, 62, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minville, C.; Hilleret, M.N.; Tamisier, R.; Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Clement, K.; Trocme, C.; Borel, J.C.; Lévy, P.; Zarski, J.P.; Pépin, J.L. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Nocturnal Hypoxia, and Endothelial Function in Patients with Sleep Apnea. Chest 2014, 145, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagojevic-Bucknall, M.; Mallen, C.; Muller, S.; Hayward, R.; West, S.; Choi, H.; Roddy, E. The Risk of Gout Among Patients With Sleep Apnea: A Matched Cohort Study. Arthritis & Rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.) 2019, 71, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justeau, G.; Gervès-Pinquié, C.; Le Vaillant, M.; Trzepizur, W.; Meslier, N.; Goupil, F.; Pigeanne, T.; Launois, S.; Leclair-Visonneau, L.; Masson, P.; et al. Association Between Nocturnal Hypoxemia and Cancer Incidence in Patients Investigated for OSA: Data From a Large Multicenter French Cohort. Chest 2020, 158, 2610–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzepizur, W.; Gervès-Pinquié, C.; Heudes, B.; Blanchard, M.; Meslier, N.; Jouvenot, M.; Kerbat, S.; Mao, R.L.; Magois, E.; Racineux, J.L.; et al. Sleep Apnea and Incident Unprovoked Venous Thromboembolism: Data from the Pays de La Loire Sleep Cohort. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2023, 123, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, T.D.; Floras, J.S. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea and Its Cardiovascular Consequences. Lancet (London, England) 2009, 373, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasali, E.; Ip, M.S.M. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Metabolic Syndrome: Alterations in Glucose Metabolism and Inflammation. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 2008, 5, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alterki, A.; Abu-Farha, M.; Al Shawaf, E.; Al-Mulla, F.; Abubaker, J. Investigating the Relationship between Obstructive Sleep Apnoea, Inflammation and Cardio-Metabolic Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 6807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, L. Oxidative Stress in Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Intermittent Hypoxia – Revisited – The Bad Ugly and Good: Implications to the Heart and Brain. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2015, 20, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltzschig, H.K.; Eckle, T. Ischemia and Reperfusion–from Mechanism to Translation. Nature Medicine 2011, 17, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisele, H.J.; Markart, P.; Schulz, R. Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Oxidative Stress, and Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence from Human Studies. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2015, 2015, 608438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanek, A.; Broz˙yna-Tkaczyk, K.; Mys´lin´ski, W. Oxidative Stress Markers among Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2021, 2021, 9681595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meliante, P.G.; Zoccali, F.; Cascone, F.; Di Stefano, V.; Greco, A.; de Vincentiis, M.; Petrella, C.; Fiore, M.; Minni, A.; Barbato, C. Molecular Pathology, Oxidative Stress, and Biomarkers in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, L.; Zhou, T.; Pannell, B.K.; Ziegler, A.C.; Best, T.M. Biological and Physiological Role of Reactive Oxygen Species – the Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Acta Physiologica 2015, 214, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A.; Chandra, N. Free Radicals, Antioxidants and Functional Foods: Impact on Human Health. Pharmacognosy Reviews 2010, 4, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcerrada, P.; Peluffo, G.; Radi, R. Nitric Oxide-Derived Oxidants with a Focus on Peroxynitrite: Molecular Targets, Cellular Responses and Therapeutic Implications. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2011, 17, 3905–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M. Role of Free Radicals and Catalytic Metal Ions in Human Disease: An Overview. Methods in Enzymology 1990, 186, 1–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, R.; Keaney, J.F. Role of Oxidative Modifications in Atherosclerosis. Physiological Reviews 2004, 84, 1381–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proteggente, A.R.; England, T.G.; Rehman, A.; Rice-Evans, C.A.; Halliwell, B. Gender Differences in Steady-State Levels of Oxidative Damage to DNA in Healthy Individuals. Free Radical Research 2002, 36, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Chaturvedi, M.M.; Aggarwal, B.B. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Cancer: How Are They Linked? Free Radical Biology & Medicine 2010, 49, 1603–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free Radicals and Antioxidants in Normal Physiological Functions and Human Disease. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S.K.; Wong, G.H.W.; McCord, J.M. Leukemia Inhibitory Factor and Tumor Necrosis Factor Induce Manganese Superoxide Dismutase and Protect Rabbit Hearts from Reperfusion Injury. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 1995, 27, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, L. Oxidative Stress Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Frontiers in Bioscience-Elite 2012, 4, 1391–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-κB Signaling in Inflammation. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2017, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottone, S.; Mulè, G.; Nardi, E.; Vadalà, A.; Guarneri, M.; Briolotta, C.; Arsena, R.; Palermo, A.; Riccobene, R.; Cerasola, G. Relation of C-Reactive Protein to Oxidative Stress and to Endothelial Activation in Essential Hypertension. American Journal of Hypertension 2006, 19, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeun, J.Y.; Kaysen, G.A. C-Reactive Protein, Oxidative Stress, Homocysteine, and Troponin as Inflammatory and Metabolic Predictors of Atherosclerosis in ESRD. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension 2000, 9, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, W.E.; Holty, J.E.C.; Bogan, R.K.; Hwang, D.; Ferouz-Colborn, A.S.; Budhiraja, R.; Redline, S.; Mensah-Osman, E.; Osman, N.I.; Li, Q.; et al. Use of Blood Biomarkers to Screen for Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Nature and Science of Sleep 2018, 10, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceló, A.; Miralles, C.; Barbé, F.; Vila, M.; Pons, S.; Agustí, A.G. Abnormal Lipid Peroxidation in Patients with Sleep Apnoea. The European Respiratory Journal 2000, 16, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpagnano, G.E.; Kharitonov, S.A.; Resta, O.; Foschino-Barbaro, M.P.; Gramiccioni, E.; Barnes, P.J. 8-Isoprostane, a Marker of Oxidative Stress, Is Increased in Exhaled Breath Condensate of Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea After Night and Is Reduced by Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Therapy. Chest 2003, 124, 1386–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, S.; Laschi, E.; Buonocore, G. Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in the Fetus and in the Newborn. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2019, 142, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpagnano, G.E.; Kharitonov, S.A.; Resta, O.; Foschino-Barbaro, M.P.; Gramiccioni, E.; Barnes, P.J. Increased 8-Isoprostane and Interleukin-6 in Breath Condensate of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients. Chest 2002, 122, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopps, E.; Canino, B.; Calandrino, V.; Montana, M.; Lo Presti, R.; Caimi, G. Lipid Peroxidation and Protein Oxidation Are Related to the Severity of OSAS. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2014, 18, 3773–3778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Witko-Sarsat, V.; Friedlander, M.; Capeillère-Blandin, C.; Nguyen-Khoa, T.; Nguyen, A.T.; Zingraff, J.; Jungers, P.; Descamps- Latscha, B. Advanced Oxidation Protein Products as a Novel Marker of Oxidative Stress in Uremia. Kidney International 1996, 49, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massy, Z.A.; Nguyen-Khoa, T. Oxidative Stress and Chronic Renal Failure: Markers and Management. Journal of Nephrology 2002, 15, 336–341. [Google Scholar]

- Yag˘ mur, A.R.; Çetin, M.A.; Karakurt, S.E.; Turhan, T.; Dere, H.H. The Levels of Advanced Oxidation Protein Products in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Irish Journal of Medical Science 2020, 189, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, A.; da Rosa, J.C.F.; Ribeiro, J.S.; Silva, S.d.L.; Bündchen, C.; Dornelles, G.P.; Fontanella, V. Intraoral Appliance Treatment Modulates Inflammatory Markers and Oxidative Damage in Elderly with Sleep Apnea. Brazilian Oral Research 2024, 38, e084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skvarilová, M.; Bulava, A.; Stejskal, D.; Adamovská, S.; Bartek, J. Increased Level of Advanced Oxidation Products (AOPP) as a Marker of Oxidative Stress in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Biomedical Papers of the Medical Faculty of the University Palacky, Olomouc, Czechoslovakia 2005, 149, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, M.; Kimura, H. Oxidative Stress in Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Putative Pathways to the Cardiovascular Complications. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2008, 10, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pau, M.C.; Mangoni, A.A.; Zinellu, E.; Pintus, G.; Carru, C.; Fois, A.G.; Pirina, P.; Zinellu, A. Circulating Superoxide Dismutase Concentrations in Obstructive Sleep Apnoea (OSA): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Han, X.; Liu, R.; Fang, J. Targeting the Thioredoxin System for Cancer Therapy. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2017, 38, 794–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.Y.; Li, M.; Wan, H.Y. Levels of Thioredoxin Are Related to the Severity of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Based on Oxidative Stress Concept. Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung 2013, 17, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, A.B.; de Sousa Rodrigues, C.F. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress Markers in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome and Additional Antioxidant Therapy: A Review Article. Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung 2016, 20, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, L. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Syndrome–an Oxidative Stress Disorder. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2003, 7, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Ben, M.; Fabiani, M.; Loffredo, L.; Polimeni, L.; Carnevale, R.; Baratta, F.; Brunori, M.; Albanese, F.; Augelletti, T.; Violi, F.; et al. Oxidative Stress Mediated Arterial Dysfunction in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnoea and the Effect of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Treatment. BMC pulmonary medicine 2012, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzoghaibi, M.A.; Bahammam, A.S. The Effect of One Night of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Therapy on Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense in Hypertensive Patients with Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung 2012, 16, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanlı, H.; Özol, D.; Ugur, K.S.; Yıldırım, Z.; Armutçu, F.; Bozkurt, B.; Yigitoglu, R. Influence of CPAP Treatment on Airway and Systemic Inflammation in OSAS Patients. Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung 2014, 18, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.I.; Chin, K.; Nakamura, H.; Morita, S.; Sumi, K.; Oga, T.; Matsumoto, H.; Niimi, A.; Fukuhara, S.; Yodoi, J.; et al. Plasma Thioredoxin, a Novel Oxidative Stress Marker, in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea before and after Nasal Continuous Positive Airway Pressure. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2008, 10, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadasivam, K.; Patial, K.; Vijayan, V.K.; Ravi, K. Anti-Oxidant Treatment in Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Syndrome. The Indian Journal of Chest Diseases & Allied Sciences 2011, 53, 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Grebe, M.; Eisele, H.J.; Weissmann, N.; Schaefer, C.; Tillmanns, H.; Seeger, W.; Schulz, R. Antioxidant Vitamin C Improves Endothelial Function in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2006, 173, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.L.; Chen, L.; Scharf, S.M. Effects of Allopurinol on Cardiac Function and Oxidant Stress in Chronic Intermittent Hypoxia. Sleep and Breathing 2010, 14, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyadevara, S.; Bharill, P.; Dandapat, A.; Hu, C.; Khaidakov, M.; Mitra, S.; Shmookler Reis, R.J.; Mehta, J.L. Aspirin Inhibits Oxidant Stress, Reduces Age-Associated Functional Declines, and Extends Lifespan of Caenorhabditis Elegans. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2013, 18, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.M.; Tung, Y.T.; Wei, C.H.; Lee, P.Y.; Chen, W. Anti-Inflammatory and Reactive Oxygen Species Suppression through Aspirin Pretreatment to Treat Hyperoxia-Induced Acute Lung Injury in NF-κB-Luciferase Inducible Transgenic Mice. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 9, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savini, C.; Tenti, E.; Mikus, E.; Eligini, S.; Munno, M.; Gaspardo, A.; Gianazza, E.; Greco, A.; Ghilardi, S.; Aldini, G.; et al. Albumin Thiolation and Oxidative Stress Status in Patients with Aortic Valve Stenosis. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovbasyuk, Z.; Ramos-Cejudo, J.; Parekh, A.; Bubu, O.M.; Ayappa, I.A.; Varga, A.W.; Chen, M.H.; Johnson, A.D.; Gutierrez- Jimenez, E.; Rapoport, D.M.; et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Platelet Aggregation, and Cardiovascular Risk. Journal of the American Heart Association 2024, 13, e034079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).