1. Introduction

Ni

3Al-based intermetallic alloys demonstrate superior characteristics compared with conventional heat-resistant nickel-based superalloys, including significantly higher strength at elevated temperature, relatively lower density, and improved resistance to corrosive environments. An analysis of the properties of these materials and their commercialization potential has been extensively presented by Sikka et al. [

1,

2], Jozwik et al. [

3] and as well as Jarosz et al. [

4], Sahare et al. [

5], Sun and Yuan [

6] and Tiwari et al. [

7]. Their findings indicate that Ni

3Al intermetallics in bulk form are predominantly utilized in the fabrication of dies and press tool components, equipment for furnaces used in thermochemical treatment, and jet engine components. Considering the aforementioned unique physical and chemical properties of these materials, their potential applications in a form of strips or foils in various advanced components, including electromechanical systems (such as heat exchangers, reactors, actuators, and glucose sensors), solar cells, automotive and aircraft engine components, and thermocatalytic systems, have been proposed.

One possible approach to obtain Ni

3Al strips and foils with enhanced strength and ductility is a hot plastic processing. Notably, the literature contains limited information regarding the hot-working of Ni

3Al-based intermetallic alloys. Furthermore, the available studies are limited to only a few research examples related to the hot processing of bulk materials (i.e., samples with a dimension of at least 8 mm). The studies under consideration include isothermal compression tests (Wang et al.[

8], Wu et al. [

9], Zhong et al. [

10] and [

11], Prasad et al. [

12]); hot extrusion (Guo et al. [

13], Sheng et al. [

14]); compression tests with heated swages, and rotary working tests with localized heating evoked by friction (Schindler et al. [

15] and [

16]). The results mentioned in the papers indicate that appropriately selected parameters of the deformation process (temperature, strain rate and degree of deformation, state of the initial structure, and a presence of alloying elements) lead to microstructural changes in Ni

3Al-based alloys as a result of dynamic recrystallization (DRX) or post-dynamic recrystallization. As it has been observed by Bhatia [

17] and Ponge et al. [

18], the DRX of Ni

3Al-based alloys can result in the presence of the “necklace structure” characterized by fine recrystallized grains surrounding large primary grains of γ’ phase. Such a structure can play a pivotal role in achieving the desired combination of high creep and low-cycle fatigue resistance. Despite these advances, the impact of specific hot deformation parameters on the microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of Ni

3Al-based alloys remains insufficiently understood, particularly for the materials in the form of thin strips or foils.

The main objective of this study was to analyze the DRX-induced microstructural changes in Ni3Al-based intermetallic strips. Because of the significantly limited dimensions (thickness of approximately 1 mm), it should be assumed that the proposed hot plastic processing will occur under conditions of intensive heat exchange between the treated material strips and the working tools (rollers).

An additional aspect of this study is to explore the possibility of obtaining transient strengthening states of Ni3Al-based alloys with the level of mechanical properties controlled by the occurrence of the necklace structure obtained by hot rolling.

2. Experimental Procedure

The hot rolling process was performed on Ni

3Al-based intermetallic alloy strips with a chemical composition of Ni–22.1Al–0.26Zr–0.1B (at.%) with using rolling mill sexto. The material in the initial state (a strip of 150 x 30 x 1.12 mm) was obtained by consecutive cold rolling and heat treatment (with strictly selected conditions of deformation and recrystallization) to obtain a single-phase fine-grained structure (grain size of d~30 µm) of the γ’ phase. Details of Ni

3Al strips production process were reported previously by Jóźwik et al. [

19,

20,

21]. Such obtained material constituted the “initial” state for the hot rolling. The processing was carried out by pre-heating the Ni

3Al-based strips to 1000 °C, 1100 °C or 1280 °C. Various strain rate

values were applied: 3.9x10

−1 s

−1, 9.9x10

−1 s

−1, 1.5 s

−1 or 2.5 s

−1 (the last one was not used for T=1280 °C). For all hot-rolling conditions, the total strain value (i.e., expressed as a relative thickness reduction) was 0.3, and it was set in one pass. To eliminate the possibility of post-dynamic recrystallization in the material, after each hot rolling operation, the samples were immediately (in less than 1 second) cooled in a water bath. Then, an electric discharge machining was used to cut the obtained strips in a plane perpendicular to the rolling direction located in the middle of the length of the rolled material. Metallographic cuts were ground on SiC papers, and mechanically polished using diamond suspensions of 3 µm and SiO

2 suspension of 0.1 µm. Microstructural studies were performed by using Quanta 3D FEG scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with a electron backscattered diffraction detector (EBSD) at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV, beam current of 8 nA, and analysis step (depending on magnification) from 1 µm to 0.1 µm.

Based on the results of systematic EBSD mapping of crystallographic orientations, the grain structure of polycrystalline strips was reconstructed, reviling positions of high– and low–angle grain boundaries, simultaneously. In turn, the maps of the surface distribution of the poles of the mean crystallographic orientation of individual grains Inverse Pole Figure (IPF) maps were the basis for assessing the presence of privileged crystallographic orientation and possible micro-texture. The analysis of structural changes as a result of the performed hot rolling procedures was based on the measurements of the degree of local disorientation of the crystal lattice in the volume of individual grains, presented in the form of Grain Orientation Spread (GOS) parameter maps. In this study, the average GOS parameter, which shows the average value of disorientation of the particular investigated area, was used. The analysis of the quality of the Kikuchi lines, thereby determining the Image Quality (IQ) parameter, was also performed. The primary source of imperfections in the measurements of the GOS and IQ parameters is the dependence of the test results on factors related to both the measurement parameters used and the quality of preparation. Therefore, during the sample preparation and testing, special attention was paid to maintaining the repeatability of the applied experimental conditions [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

Finally, hardness measurements were performed in the rolling plane using the Rockwell method (HRB), with a 1/16 inch ball and a load of 100 kg, and the average value and standard deviation were determined based on at least ten measurements for each tested material variant.

Additionally, to estimate the temperature changes of the Ni

3Al strips during hot rolling, a model of non-stationary heat conduction in a hot-rolled metal plate was formulated using the Comsol/FEM (Finite Element Method) calculation package (more details are show elsewhere [

27]). This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3. Results and Discussion

The examined Ni

3Al-based intermetallic alloy in the initial stage (before the hot rolling) exhibited a single-phase, fine-grained γ’ secondary solid solution structure (

Figure 1). The results of EBSD analyses revealed the following features: (i) a dominant (approximately 95%) fraction of high angle grain boundaries (with a disorientation angle greater than 15° between neighbouring grains) (

Figure 1a), (ii) no visible crystallographic texture (

Figure 1b) and (iii) a very low value of the GOS parameter (internal Grain Orientation Spread ≤1°), which is specific for a fully recrystallized material (

Figure 1c).

The GOS parameter (expressed in angular degrees) measures a scattering of the crystal lattice misorientation inside a individual grain. This parameter assumes that a plastic deformation in a metallic polycrystalline material is assisted by local changes of the crystal lattice orientation in the volume of each individual grains. This crystal lattice evolution is necessary to maintain the cohesion along grain boundaries of a material subjected to a plastic deformation. For thermally activated processes (i.e., recovery and recrystallization) this parameter enables a quantitative assessment of the extent of these processes, as presented by Schwartzer et al. [

28], Conde et al. [

29] and Esin et al. [

30]. In a polycrystalline structure, grains with a very low fraction of structural defects (typically after the recrystallization process, as in the case of the analysed alloy in the initial state) show negligible differentiation of local crystallographic orientations and the value of the GOS parameter is ≤1°. In turn, deformed grains with a high density of crystal defects show a high value of internal misorientation and, therefore, a high value (GOS>1°) of this parameter.

The IQ parameter expresses a strong relationship between the degree of crystal structure defects (e.g., as a result of plastic deformation) and the quality (blurring) of the backscattered electron diffraction lines. The electron beam interacting with the surface layer of the sample is dispersed on the crystal lattice’s defects, and the crystal planes’ curvatures are “bent” due to plastic deformation. Consequently, the diffraction lines obtained from the subareas with a high density of lattice defects are blurred and visible as dark. According to Ku [

22] and Alam et al. [

31], IQ values can be correlated with the dislocation density, thereby providing a means of quantifying the internal strain energy and residual stress within a material. This correlation can be particularly valuable for understanding the effects of thermal treatments and mechanical processing on material properties [

32].

Hot rolling of the Ni

3Al-based alloy to a strain value of 0.3 has a noticeable effect on both the microstructure (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) and hardness (

Figure 8) of the tested material, depending on the applied temperature and the strain rate. The results of EBSD analyses (compare Figure1 and

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) showed a limited extent of structural reconstruction. A comparative assessment of the GOS parameter for the material after the hot rolling showed a noticeable increase of its value compared to the starting material (the non-deformed one), with the presence of grains exhibiting a GOS >10° (compare Figure1c,

Figure 2a,c,e, and

Figure 3a,c,e).

The quantitative evaluation of the averaged GOS parameter values clearly shows the impact of the rolling parameters on the extent of the structural reconstruction (

Figure 4a). A much more significant influence of the deformation temperature was observed in the relation to strain rate. For the hot rolling process carried out at the high strain rate (

≥ 1.5 s

−1), a similar tendency was observed. An almost linear dependence of the average GOS value on temperature was obtained (

Figure 4a). The influence of a high strain rate on the course of DRX is also indicated by the analysis of the IQ parameter - for the value

≥ 1.5 s

−1 - increased almost linearly with the deformation temperature (

Figure 4b). The IQ parameter value did not show a significant dependence on temperature due to the hot rolling at a strain rate

of 3.9x10

−1 s

−1, and the observed changes were insignificant (approximately 3%).

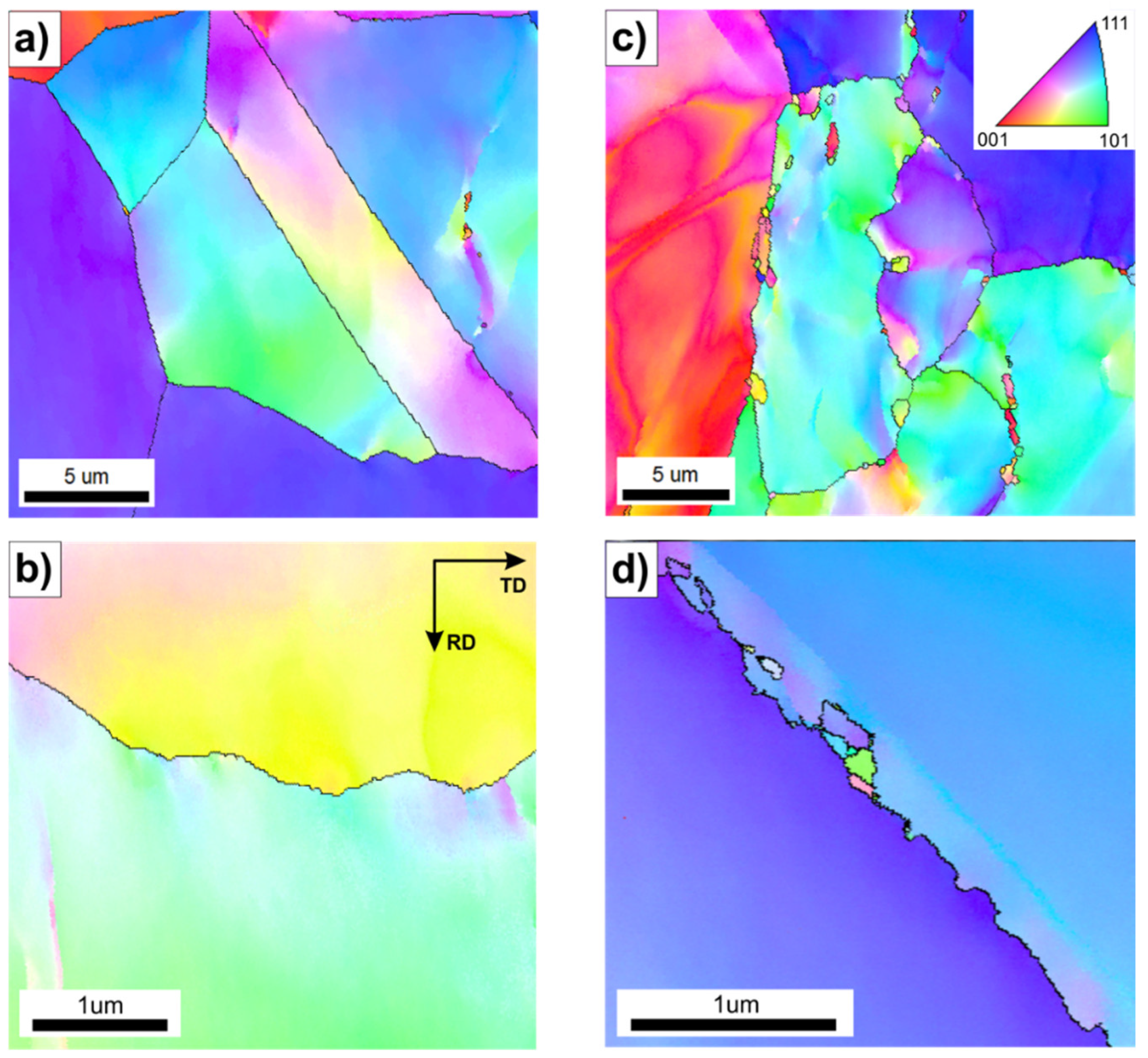

=3.9x10−1 s−1 at the initial temperature of: (a,b) 1000 °C, (c,d) 1100 °C, (e,f) 1280 °C.

=2.5 s−1 at the initial temperature of: (a,b) 1000 °C, (c,d) 1100 °C and at strain rate of =1.5 s−1 at temperature of 1280 °C – (e,f).

The results of more detailed EBSD analyses carried out by using higher magnifications revealed the locally occurring effects of thermally activated processes with intensity dependent on the values of the applied processing parameters (

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). The material deformed at T=1000 °C with a strain rate of 3.9x10

−1 s

−1 (

Figure 5a,b) did not show a presence of structural features that are typical for the DRX.

Increasing the strain rate at this temperature resulted in the growing fraction of very fine DRX grains (

Figure 5). A serration of primary grain boundaries was observed (

Figure 5c,d) in the sample hot-rolled at T=1000 °C and at a strain rate of 2.5 s

−1. Analogous observations were reported by Ponge et al. [

18], Sakai et al. [

33] and Koundinya et al. [

34], according to whom such structural features are specific for a deformation temperature lower than the critical temperature for initiating the dynamic recrystallization process. The serration of grain primary boundaries was also observed after the hot rolling at T=1100 °C and at a strain rate of 9.9x10

−1 s

−1.

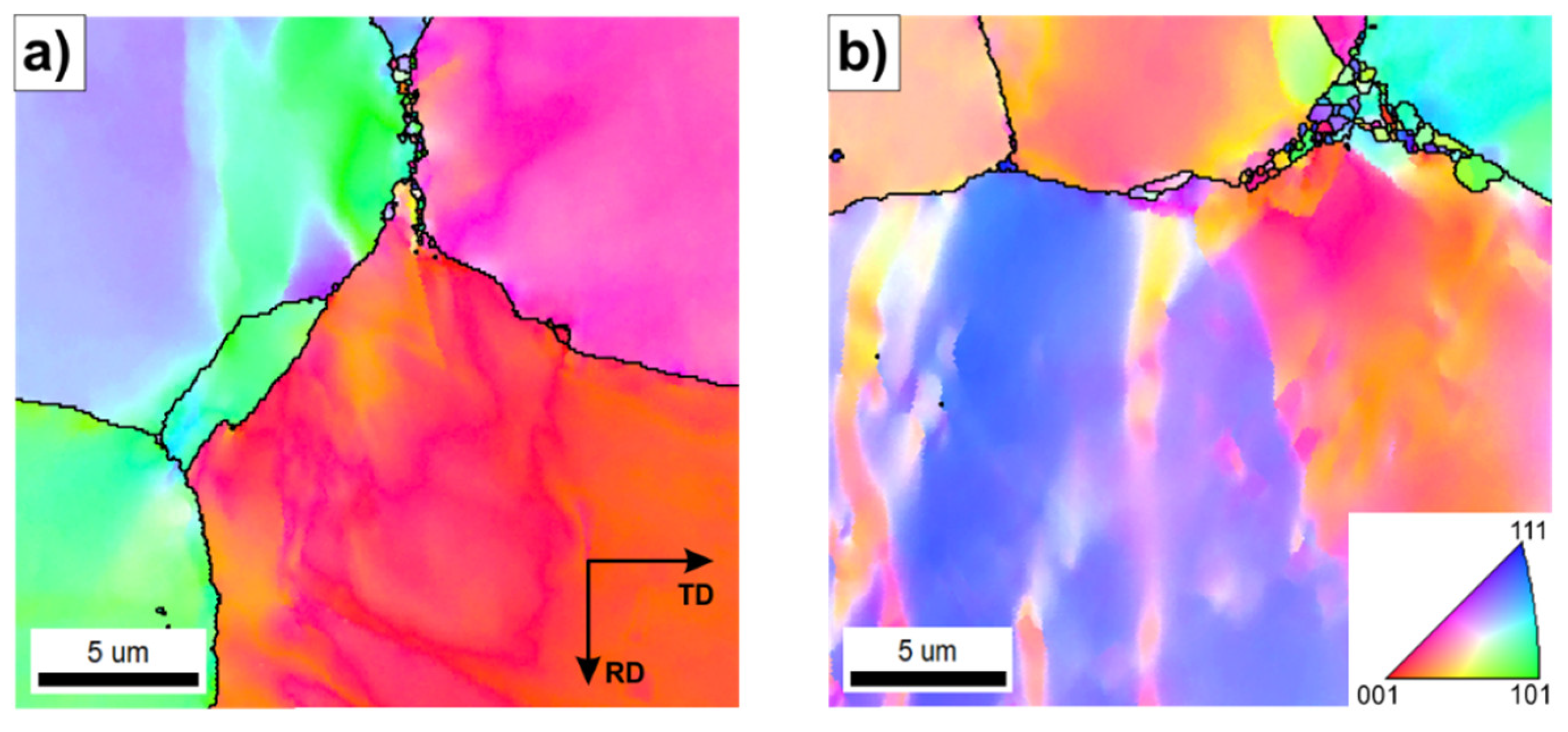

Therefore, an increase in the initial strip temperature (up to 1100 °C) promotes the formation of new grains by the DRX in sites with the highest stress concentration, i.e., the triple-junctions of grain boundaries (

Figure 6), as well as along the straight segments of primary grain boundaries. The share of grain boundary segments affected by the DRX increased with increasing the strain rate, which was also reflected in the observed decrease in the strain strengthening (

Figure 8).

of: (a, b) 3.9x10−1 s−1 and (c, d) 2,5 s−1.

of: (a) 3.9x10−1 s−1and (b) 2,5 s−1.

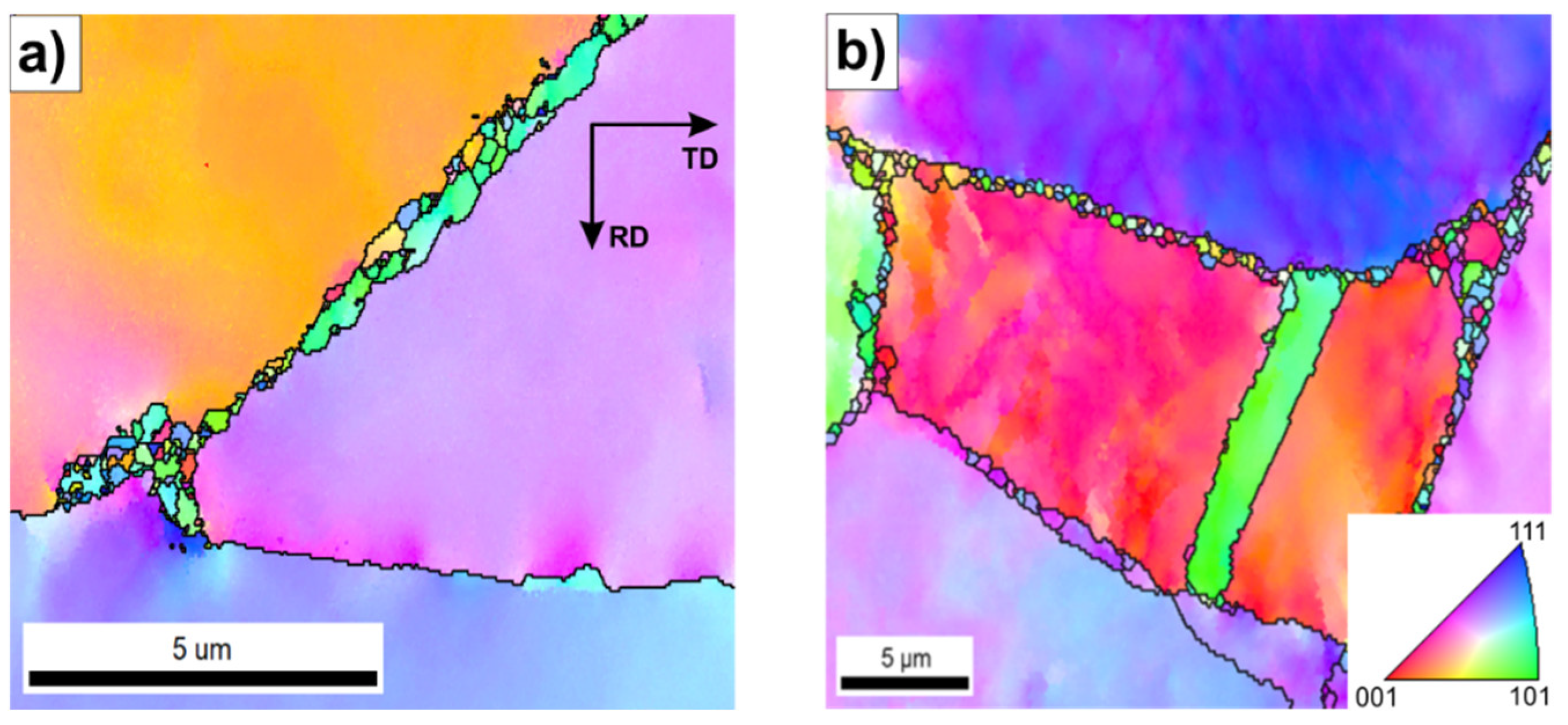

After the hot rolling at T=1280 °C, the material showed the largest share of DRXed grains both in the triple-junction grain boundaries and along the primary grain boundaries (

Figure 7b). As reported by Bhatia et al. [

17], the tendency to form necklace structures in the Ni

3Al-based alloys, is caused by the tendency of planar slip and difficulty of cell formation inside the grains. Karnthaler et al. [

35], Kruml et al. [

36], and Wang et al. [

37] have classified the Ni

3Al-based alloys as high stacking fault energy (SFE of approximately 240 mJ/m

2) materials. However, the results of studies by Jozwik et al. [

19,

21] and Polkowski et al. [

38] indicate that the behaviour of materials from this group under plastic deformation conditions and subsequent thermally activated processes is more similar to that of low SFE materials, as they are characterized by intensive strain hardening (resulting from hindered transverse slip of screw dislocations and a tendency to form flat stacking of dislocations on obstacles). Furthermore, as it has been shown by Schindler et al. [

15,

16] the low SFE of Ni

3Al-based alloys decreases a susceptibility to the DRX. Consequently, a higher strain concentration at grain boundaries is obtained leading to the DRX into the necklace structure. Such a microstructure rebuilding, which is very similar to the model presented by Ponge et al. [

18], was observed in the material after the hot-rolling at a strain rate

=1.5 s

−1 (

Figure 7b).

of: (a) 3.9x10−1 s−1 and (b) 1.5 s−1.

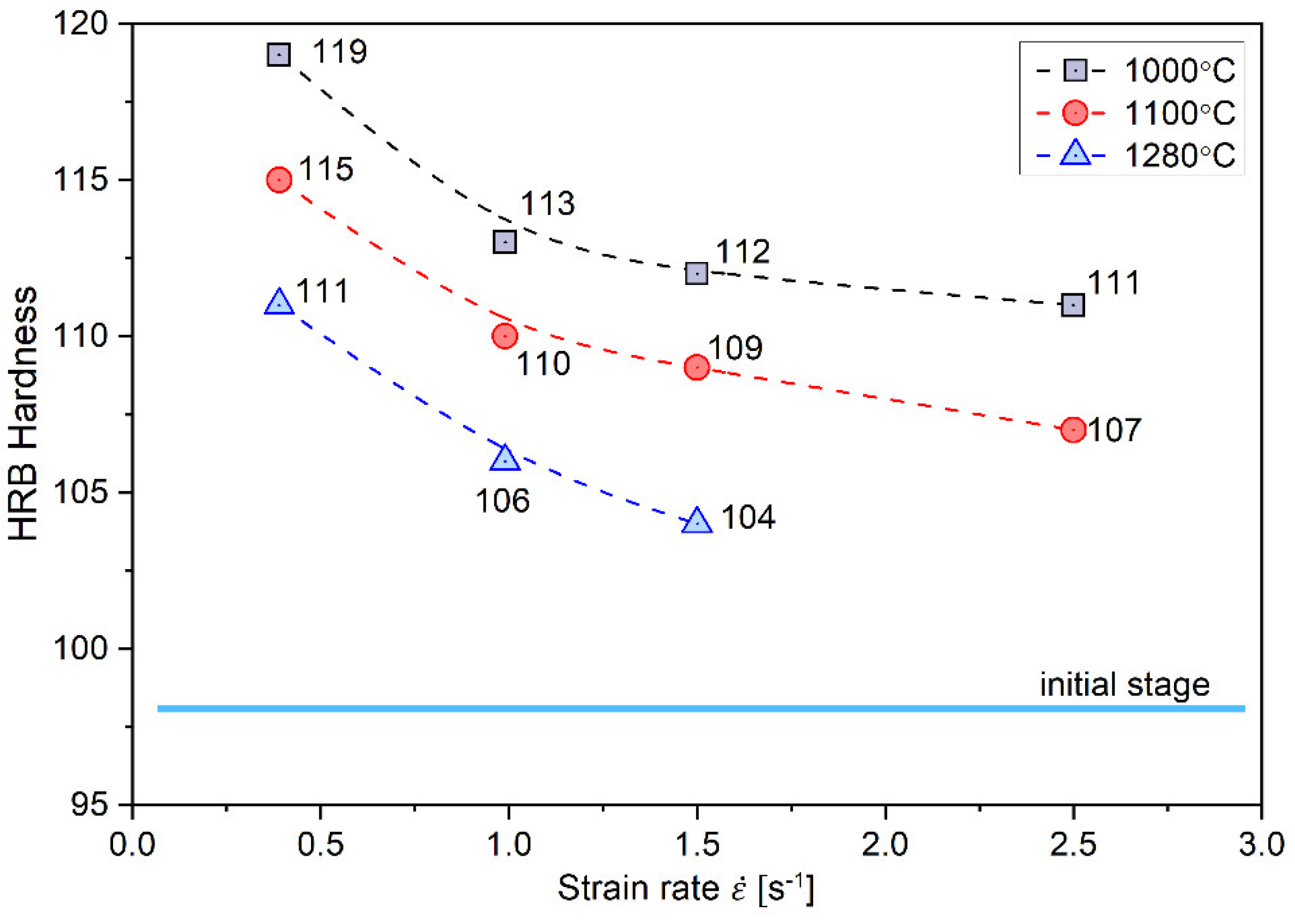

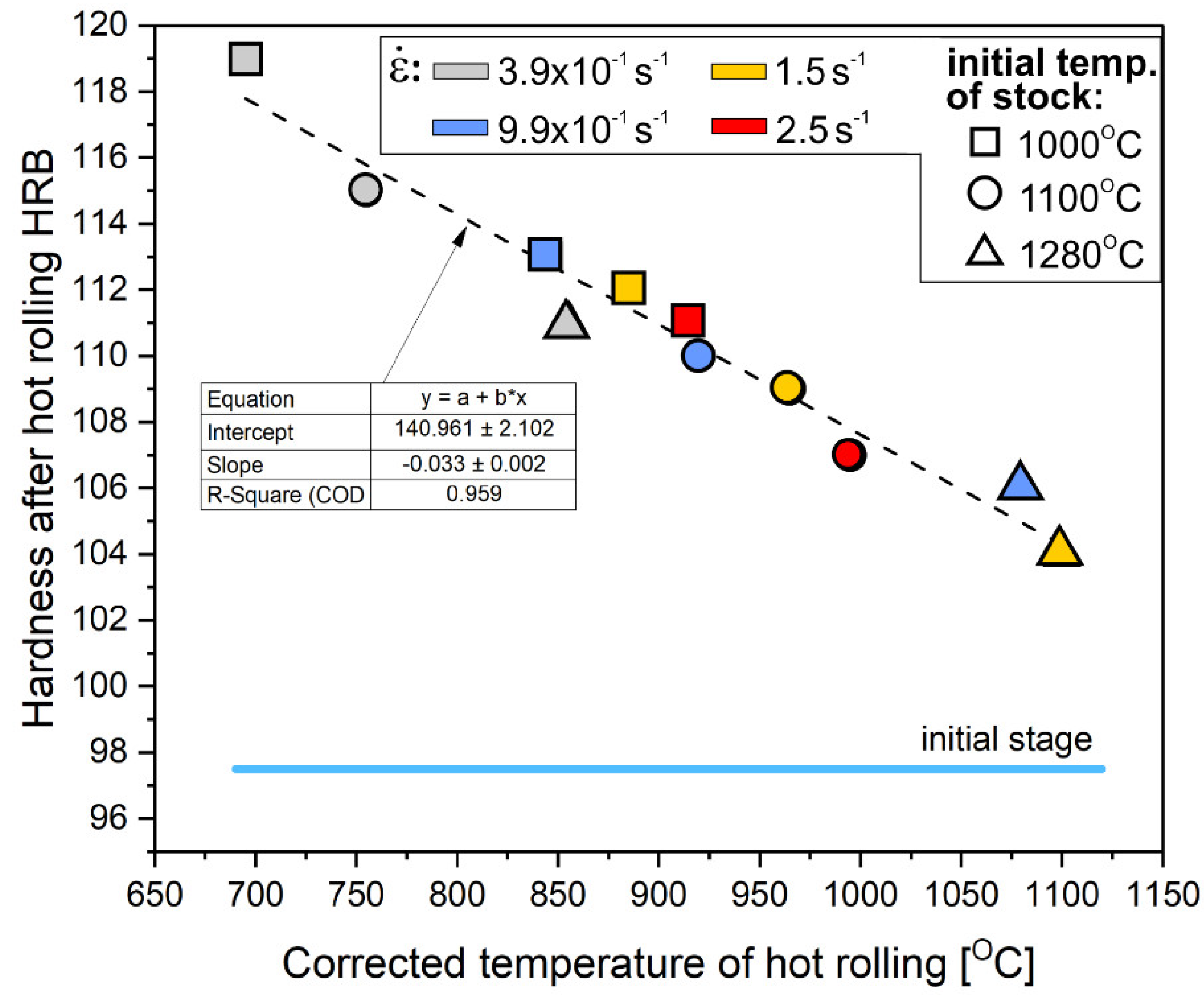

Regardless of the applied hot-rolling process parameters, the deformed material showed a significant increase in hardness as compared with the initial material, resulting from the increased stored deformation energy (

Figure 8). Regardless of the applied hot rolling temperature, the increase in the strain rate resulted in a decrease in the strain hardening of the material. It was mostly visible in the case of the process conducted at the highest strain rate (i.e., 2.5 s

−1). The obtained results correspond to the discussed changes in the EBSD examined microstructure (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). In other words, the microstructural evolution is dominated by a dynamic recovery process with the DRX limited to some micro-areas. As the dynamic recovery, creates low-energy dislocation systems (polygonal walls and subgrains), it effectively contributes to a reduction of the total energy stored.

The presently obtained results show that under the applied experimental conditions, a higher strain rate favours the microstructure evolution by both the DRX and dynamic recovery. This unusual relationship is probably due to the very low heat storage of the rolled Ni3Al strips, that is, the initial thickness was 1.12 mm (for comparison, the smallest dimension of Ni3Al samples analyzed in the literature is 8 mm), which, in combination with cold work rolls, resulted in greater heat losses, leading to a significant reduction in the actual material temperature during the deformation process. Consequently, a higher strain rate corresponded to relatively higher process temperature.

To estimate the possible temperature changes of the Ni3Al strips during the hot-rolling, as well as to verify the obtained research results, a non-stationary model of heat conduction in a hot-rolled metal plate, was formulated.

Regardless of the applied hot-rolling process parameters, the deformed material showed a significant increase in hardness as compared with the initial material, resulting from the increased stored deformation energy (

Figure 8). Regardless of the applied hot rolling temperature, the increase in the strain rate resulted in a decrease in the strain hardening of the material. It was mostly visible in the case of the process conducted at the highest strain rate (i.e., 2.5 s

−1). The obtained results correspond to the discussed changes in the EBSD examined microstructure (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). In other words, the microstructural evolution is dominated by a dynamic recovery process with the DRX limited to some micro-areas. As the dynamic recovery, creates low-energy dislocation systems (polygonal walls and subgrains), it effectively contributes to a reduction of the total energy stored.

and initial temperature of stock on Brinell hardness of Ni3Al-based strips (average values).

A non-Stationary Heat Conduction Model in a Strip

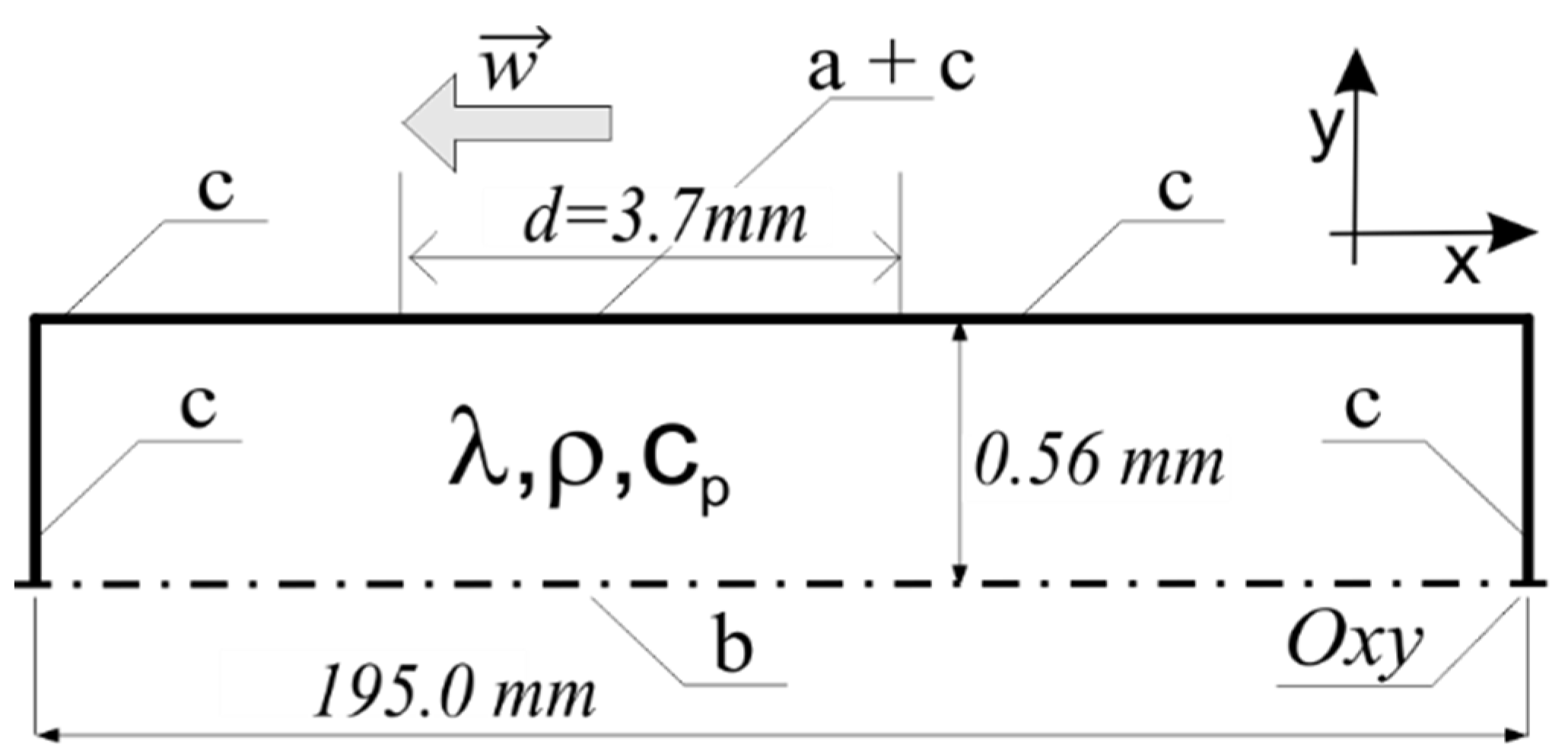

The primary purpose of the modelling was to qualitatively determine the temperature changes. For this purpose, the issue was simplified to a model of heat source moving across the surface of the component. Thus, a contact surface having a linear dimension d, was set as the source of heat and at the same time - the heat receiver (

Figure 9).

To determine the temperature changes and strain distribution, the presence of the following phenomena were analysed [

39]: (i) the heat conduction in the workpiece to be deformed (i.e., the Ni

3Al strip); (ii) convective and radiative heat losses from the workpiece surface to the environment; (iii) the heat conduction in the machining tool (roller); (iv) a contact heat transfer resistance between the workpiece and the tool; (v) a friction between the workpiece and the roller surface contributing to the surface heat source; (vi) an elastic deformation of the workpiece; (vii) a plastic deformation constituting volumetric heat sources, (viii) elastic relaxation of the material as it comes off the roller, and (ix) a change in the relative velocity of movement of the workpiece and the roller due to deformation. In the presented simplified model of a moving heat source, only the phenomena (i) – (iv) were directly taken into account. A phenomenon that is usually overlooked at this stage of simplification is the volumetric shrinkage caused by a thermal expansion.

The relatively large value of the ratio of the wafer width to its thickness provides a justification for adopting a simplified two-dimensional heat conduction model. A geometrical scheme of the model is illustrated in

Figure 9.

Thus, the issue was reduced to a two-dimensional model of a non-stationary heat transfer in a plate having dimension of 195 mm × 0.56 mm, subjected to surface moving heat source (surface a in

Figure 9) [

42]. A symmetry condition in the plane containing the Ox axis was assumed (surface b in

Figure 9), while convection and radiation losses were considered for other surfaces (surface c in

Figure 9). Due to the lack of data on the constitutive model, the volumetric heat sources accompanying plastic deformation, as well as the surface frictional heat source, were omitted. An evaluation of the literature data shows that despite the noticeable impact of these effects, they do not play a dominant role in shaping the temperature distribution at a relatively high initial temperature of the hot-machined workpiece (i.e., Ni

3Al strip).

The mathematical equations describing the considered model (in the Oxy coordinate system,

Figure 9), are as follows:

boundary condition for the adiabatization of the horizontal center symmetry surface of the plate (surface marked as “b” in

Figure 9):

boundary conditions of convective and radiative heat loss (surfaces marked “c” in

Figure 9, “n” is a normal direction to surfaces c):

the displacement contact zone is modelled by the additional contact loss (surface marked as “a+c” in

Figure 9) of the plate surface with the surface of the cylinder at ambient temperature, with the value of the thermal contact resistance r

cont:

The last boundary condition was applied in a superposition with equation (4). The equation describes a contact with the cylinder surface excluding radiation losses and convective losses. On the other hand, in the considered case, these losses account for only approximately 2% of the losses caused by a heat transfer through the contact zone. Because determination of the value of thermal contact resistance is subjected to a larger error, and because of the need for computational optimization of the numerical model, the arrangement of conditions (4) and (5) remained unchanged.

Numerical Model

The tools of the Comsol/M FEA (Finite Element Method) calculation package were used to build the numerical model. The temperature dependence of the material parameters of the analyzed alloy was considered (

Table 1) by extrapolating data from the studies by Panas et al. [

40] and Terpilowski [

41].

Table 2 presents values of parameters defining the boundary conditions developed based on the analysis of the criterion relations of the heat transfer issue and the data contained in the aforementioned monograph by Lenard et al. [

33]. Based on these data, the value of the equivalent heat transfer coefficient in the contact resistance zone was assumed to be 13 000 W×m

−2×K

−1, which corresponds to the value of r

cont given in

Table 2.

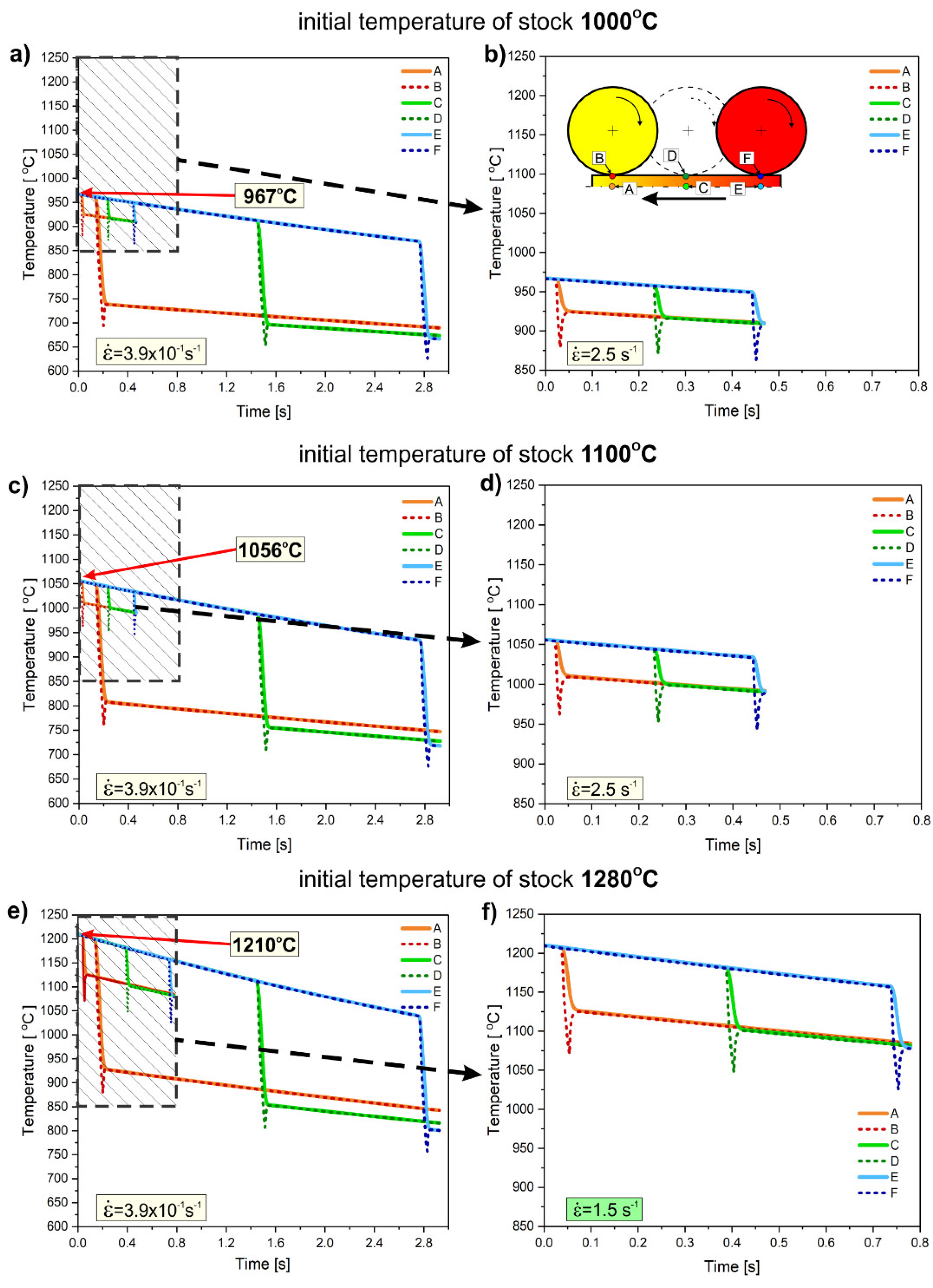

The analysis considered the realistic conditions of the rolling process, including the thermal exchange between the sample and its environment during the 1-second period from when the sample was removed from the furnace until it came into contact with the rollers. Consequently, the initial temperature of the stock was reduced i.e., from 1280 °C of the initial temperature of stock to 1210 °C; and adequately from 1100 °C for 1056 °C, and from 1000 °C to 967 °C. Regular rectangular finite elements were used for calculations. A division of eight elements was used in the vertical direction, and 780 elements were used in the horizontal direction. The horizontal division density was set as 1 mm. Numerical simulations of the heat conduction process were performed with a constant time step. For the highest strain rate (i.e., 2.5 s−1), the time step was 0.0015 s, and for the lowest (i.e., 3.9 x10−1 s−1) it was 0.0075 s.

To visualize the obtained calculation results control points were defined at the rolled band side surface and core (

Figure 10):

in the plane perpendicular to the rolling direction: core (points A, C, and E), contact surface of the rollers (points B, D, and F),

plane parallel to the rolling direction: the beginning (points A and B), center (points C and D), and the end of the sample (points E and F).

In terms of the 2D nature of the model, the points represent lines parallel to the roller axis. In the model, it was assumed that points A and B were located 10 mm from the start of the sample, points C and D were positioned at the center of the sample, and points E and F were placed 10 mm before the sample’s end.

The results of modelling showed a significant effect of the strain rate on the change in material temperature during rolling process. As it was expected, the most significant changes in each of the analysed case were observed at the surface of the sample directly in contact with the rollers (points: B, D, and F, respectively). After an initial decrease in the temperature of the band, a slight increase was observed because of the heat transmission from the core of the material and the heating of the rollers. Owing to its higher heat capacity, the core point (i.e., points A, C and E) turned out to be slightly more temperature stable, and the observed changes occurred with significantly lower intensity (

Figure 10).

The greatest cooling of the rolled band was observed for the highest initial temperature of stock, i.e., 1280 °C (reduced before contact with the rollers to 1210 °C as a consequence of heat exchange with the environment) and the lowest strain rate (i.e.,

= 3.9x10

−1 s

−1). Under these conditions, the temperature gradient was the most significant, and the contact time between the rollers and the workpiece material was the longest. Consequently, the temperature in the core of the material decreased by approximately 280 °C at the beginning and 410 °C at the end of the sample. Notably, despite the largest temperature change among the analyzed cases, its value remained above 800 °C throughout the deformation process. The increase in the strain rate for this processing temperature resulted in a significantly higher value of temperature during deformation (i.e., above 1070 °C for

= 1.5 s

−1) owing to the shorter contact time of the rollers with the material. The analyzed temperature changes correspond with the observed microstructural restoration by dynamic recrystallization, the contribution of which increases with increasing the strain rate (

Figure 7).

At the initial temperature of the stock to 1100 °C, which was reduced to 1056 °C by losses related to heat exchange with the environment, and strain rate

= 3.9x10

−1 s

−1, results in less cooling of the material by approximately 250 °C at the beginning and 340 °C at the end of rolling, respectively. However, it is worth noting that in this case, the temperature decreased to approximately 800 °C at the beginning and 720 °C at the end of the band. As shown by the studies of Prasad et al. [

12], Schindler et al. [

15,

16] and Jóźwik et al. [

19,

20] this value is not sufficient to initiate recrystallization processes. Consequently, for these rolling conditions (i.e., 1100 °C of the stock and

= 3.9x10

−1 s

−1), only a slight visible rebuilding effect in the microstructure by dynamic recrystallization is observed (

Figure 6) with a simultaneous reduction in the strengthening of materials under these conditions (

Figure 8). Increasing the strain rate

to 2.5 s

−1, with an initial stock temperature of 1100 °C, results in reduced heat transfer with the rollers and consequently a higher material temperature in the core during the deformation process, that is approximately 1010 °C at the beginning and 990 °C at the end of the band. As with deformation at highest initial temperature of stock (i.e., 1280 °C), dynamic recrystallization processes are most evident for the highest strain rate, which provides the shortest contact time between the rollers and the material (

Figure 4).

A further decrease in the temperature of the stock down to 1000 °C (reduced to 967 °C by losses related to heat exchange with the environment) and strain rate

= 3.9x10

−1 s

−1 results in temperature decrease to approximately 740 °C at the beginning and 670 °C at the end of the band. As it was previously mentioned, such value of temperature is definitely too low to initiate the dynamic recrystallization process. As a result, no visible effects of the microstructure evolution by dynamic recrystallization were observed under these rolling conditions (

Figure 5). Simultaneously, the level of strengthening was the highest among all analyzed process conditions (

Figure 8). Increasing the strain rate

to 2.5 s

−1, with a constant temperature of stock (i.e., 1000 °C), results in a higher material temperature in the core during the deformation process, that is, 925 °C at the beginning and 910 °C at the end of the band.

Similar to the deformation processes realized at 1280 °C and 1100 °C, the dynamic recrystallization process is mostly observed for the material processed at the highest strain rate

because of the lower undercooling and higher rolling temperature (

Figure 10).

Finally, considering the corrected temperature in the core of the material (obtained from the model,

Figure 10, point C), an almost linear effect on strengthening was observed (

Figure 11). It is a macroscopic determinant of the intensity of heat-activated processes of the structure restoration (recovery and recrystallization), which consequently fully corresponds to the analysis of EBSD results presented above (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).