2. Materials and Methods

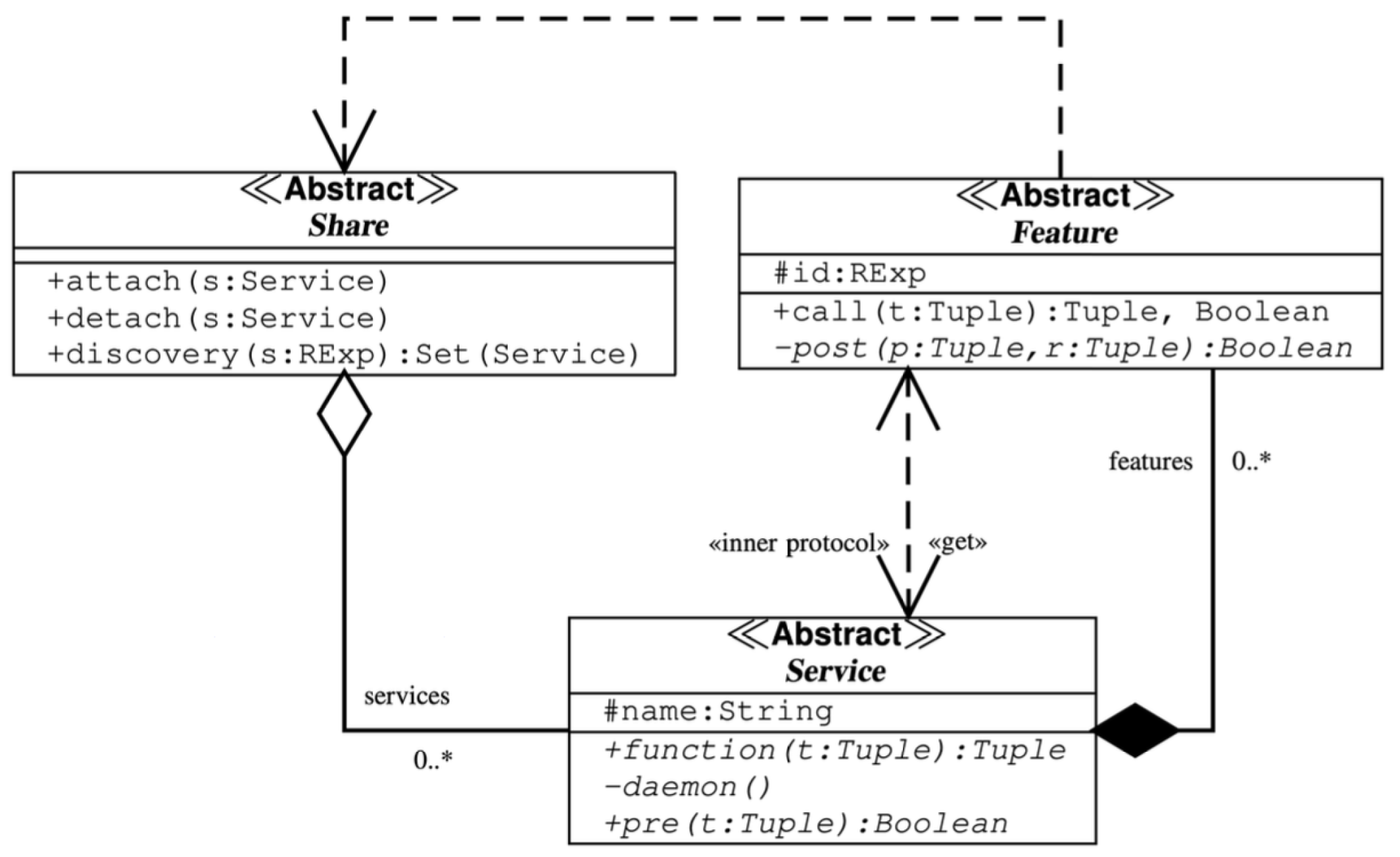

To better understand how SHARE operates and how it is simulated, it is essential to define both the structural and behavioral aspects of the design pattern. These aspects are effectively represented through class and sequence diagrams, which illustrate the interactions among components and the mechanisms enabling the system’s dynamic service composition.

Class diagrams are used to represent the static structure of the system, including key classes, attributes, and relationships. Sequence diagrams, on the other hand, capture the dynamic behavior by modeling time-ordered interactions between components. Together, these meta models form the foundation for implementation, supporting an organized and scalable architecture.

In the figure above

Figure 1, the class diagram of the Share design pattern is shown. As can be seen, it consists of the following classes:

Service object can be stored inside the space implemented by the class Share. This class has three public methods: attach(s: Service), detach(s: Service), discovery(s: RExp):Set(Service).

The public method attach(s: Service) can be used to add a Service s to a Share object, while the method detach(s: Service) on the contrary allows to remove the Service s. The third method discovery(s: RExp):Set(Service) is able to search all Service objects with a regular expression s. A set Set(Service of all services that match the regular expression RExepare returned to the caller.

For instance, a Service

double temperature_alert(double temp, double threshold) can be defined to evaluate whether a given temperature value exceeds a predefined threshold and triggers an alert if necessary. This can be added by using the method

attach. The service is identified by the string "2.5.8.10" to identify the specific function. It is possible to search a service, in this case the service for the temperature alert using a regular expression

RExep = "2.5.8.10" when the

discovery service is used. Looking at

Figure 1 the

Service class define a service which has a

name and this is a unique identifier such as a Management Information Base (MIB) of the Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP) which can be used as an unique object identifier (OID) of the function performed by service [

20]. We used the MIB "2.5.8.10" for the

temperature_alert service example. A

pre predicate is defined by a

Service class. This method takes as input a

Tuple t and returns a boolean value. The tuple

t can include the list of parameters that are taken as input by the service. The predicate should return true when the tuple

t verifies the preconditions required to run the service

false otherwise. In our

double temperature_alert(double temp, double threshold), the precondition predicate ensures that both temperature and threshold are within the valid operational range of the sensor. For instance,

boolean pre([temperature, threshold]) verifies that they are positive and within the sensor’s limits. IoT devices (such as ESP32-based sensors) can dynamically attach or discover this service using Share, enabling seamless interoperability among different sensor nodes. A

Service class needs also to specify a

Tuple function(t Tuple) and a

daemon(). To interact with the

daemon, the

function is used as a connector and it is sent to the client requesting the service. More specifically,

function(t Tuple) acts as a client stub and converts the service parameters

t into a format which the corresponding

daemon() method can interpret. The

function method establishes a connection, transmits the data to the

daemon, and may optionally wait for a response. It is important to note that the serialization and deserialization handled by

function and

daemon are unnecessary when both the client and server use the same programming language and run on identical hardware. This setup enables highly efficient data transfer, particularly for handling complex structures or large data volumes. Additionally, when both components share the same language, it facilitates consistency checks and improves reliability, simplifying the use of verification tools. The class

Features is the most important block of the design pattern Share. To implement

Service class behavior, the

daemon can compose one or more

Features, and its regular expression

id : RExp describes the functionality that is implemented by the feature. This will be utilized to locate the required feature when a Share object is called. In practice, a service that has already been defined and added to a

Service repository is defined by a

Feature. The output of a

call may be either

Boolean or

Tuple. The output of the

call functionality is a

Tuple, and when the call execution ends successfully, the

Boolean value is

true; otherwise, it is

false. This may result from a service not found error, a connection issue, or other kinds of failures specified inside the

call implementation. A

post predicate is defined by a

Features class. This function returns a

Boolean value after receiving a

Tuple t as input. When the program evaluates the post-conditions after executing the

call, the predicate should return

true; otherwise, it should return

false. In our example

double temperature_alert(double temp, double threshold),

Feature could implement the validation check to make sure the temperature does not pass over the given threshold before triggering an alert. In this case, the

call takes the

Tuple [temperature, threshold] and returns a

Boolean value to indicate if the alert should be activated. This mechanism enables the system to integrate a new alerting service in a dynamic way based on predefined conditions. In this way, it ensures an efficient monitoring in IoT-based environments.

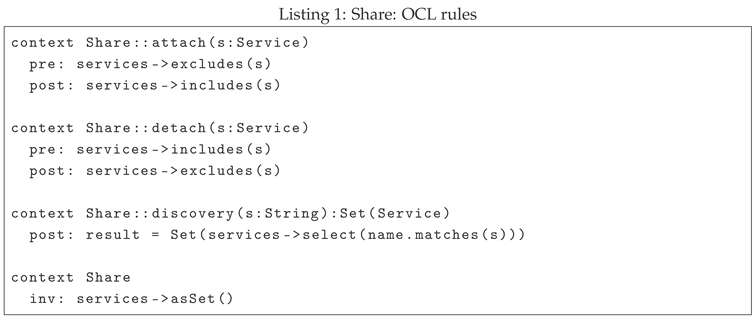

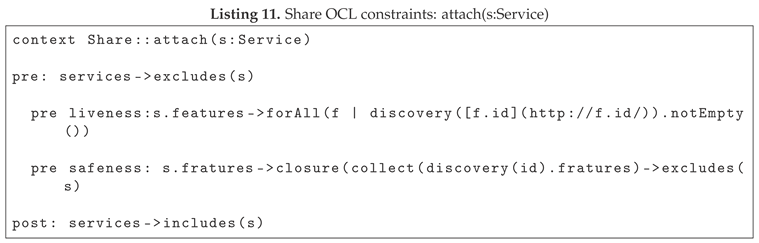

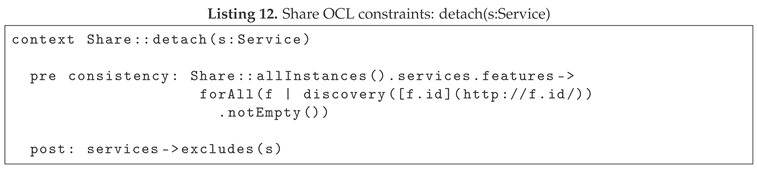

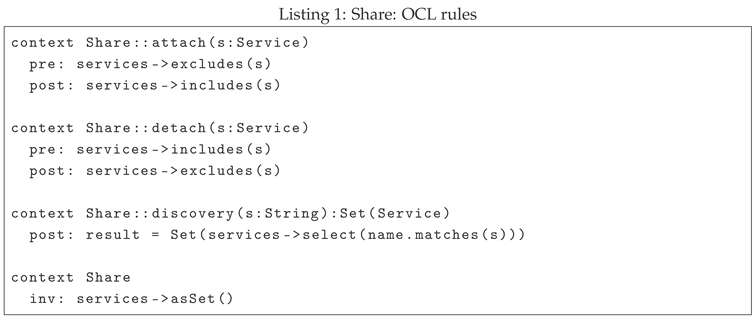

There are various Object Constraint Language (OCL) rules applied to the class diagram in

Figure 1, and they are presented in Listing 1. Analyzing context rules, there are three methods previously discussed:

attach,

detach,

discovery. The first context rule specifies the method to add the service

s into the

services association, while the second context rule specifies the method to remove the service

s from the

services association. The third context rule specifies the method that returns all services that match the regular expression

RExp s. At the end, the last rule specifies the absence of duplicated services.

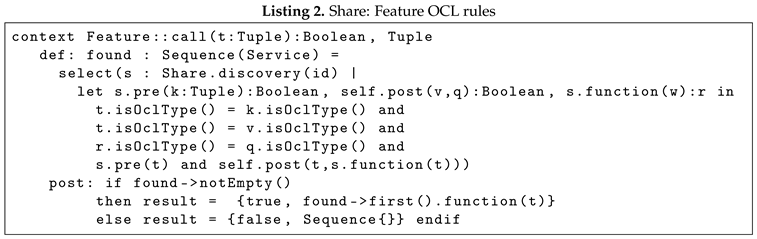

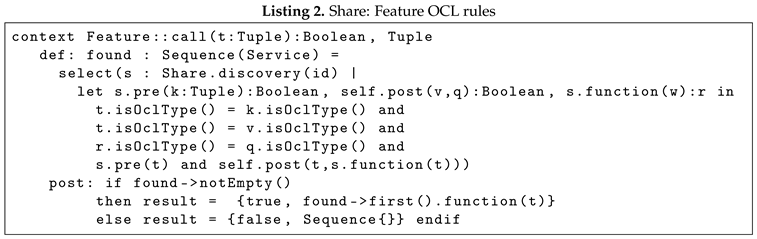

To ensure consistency between the operations required to call an operation, OCL rules in Listing 2 must be followed. The results of the call are specified by the sequence found and defined by applying to all the services found with the discovery operation pre, function, and post using the tuple of the function call. The correct relation between parameters and operation (pre, function, and post) is defined by the rules definition. Finally, the result of the call operation is the first result of the found sequence or the couple: boolean, tuple where the true value specifies the successful execution of the call invocation (i.e., a service has been found).

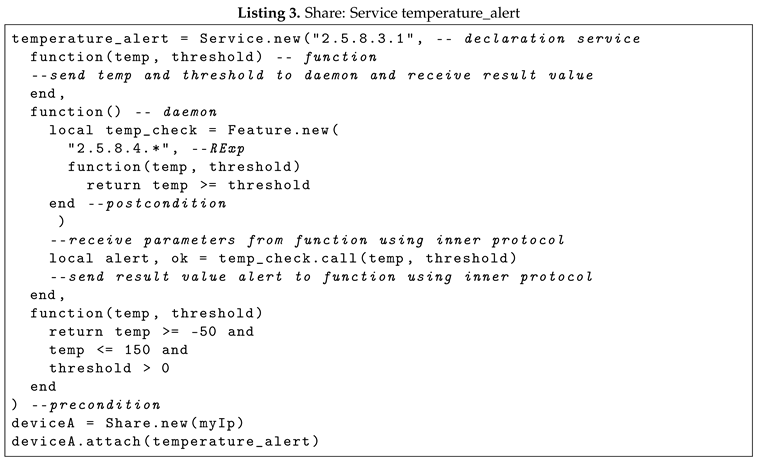

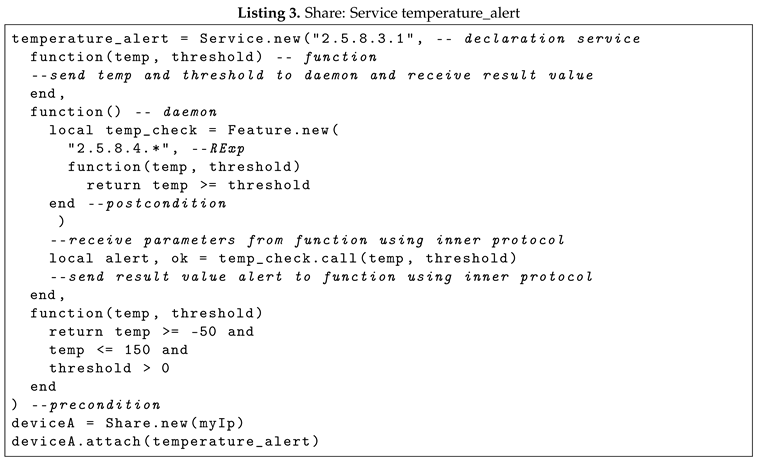

In Listing 3 and Listing 4, the implementation of a Share temperature_alert is represented with LUA language implementation. The Service in example called temperature_alert takes the following parameters:

the unique identifier of the Service (i.e. its MIB);

a LUA function, i.e the Service function implementation of the client stub;

-

a LUA function that implements the daemon which declares different parts:

a feature with RExp 2.5.8.4.*;

a post condition that specifies the comparison of the temperature and the threshold with precision;

the reception of the parameters and the call of the temp_check function.

the pre condition of the temperature_alert service, specifying that the temperature must be within the range of -50 to 150, inclusive.

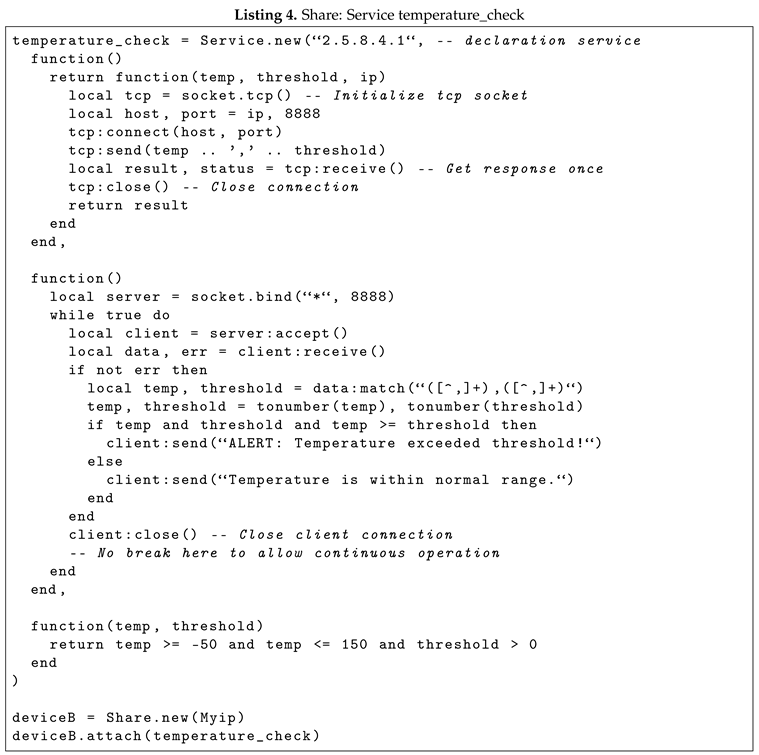

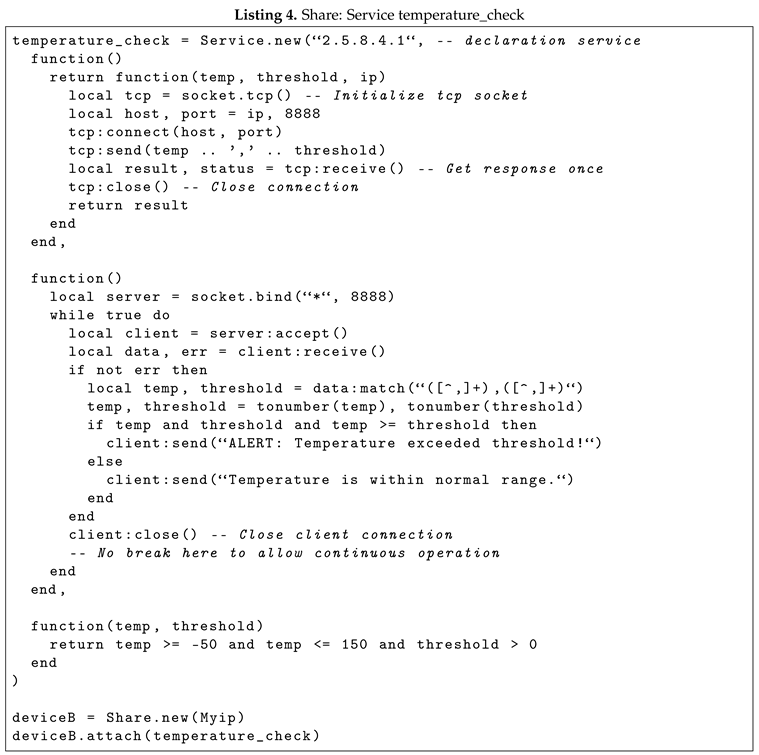

On the other hand, in the Listing 4 there is the temperature_check Service which takes as input the following parameters:

the unique identifier of the Service (i.e. its MIB);

a LUA function, i.e., the Service function implementation of the client stub, to enable a connection to the service;

a LUA function which implements the daemon. Here, it is possible to observe the validation of the comparison from temperature and threshold.

the pre condition of the temperature_check service, specifying that the temperature must be in the range -50 to 150 with edges included.

In the Listing 3 and Listing 4, it is possible to observe that they use the attach() method and register the newly created service to a Share object.

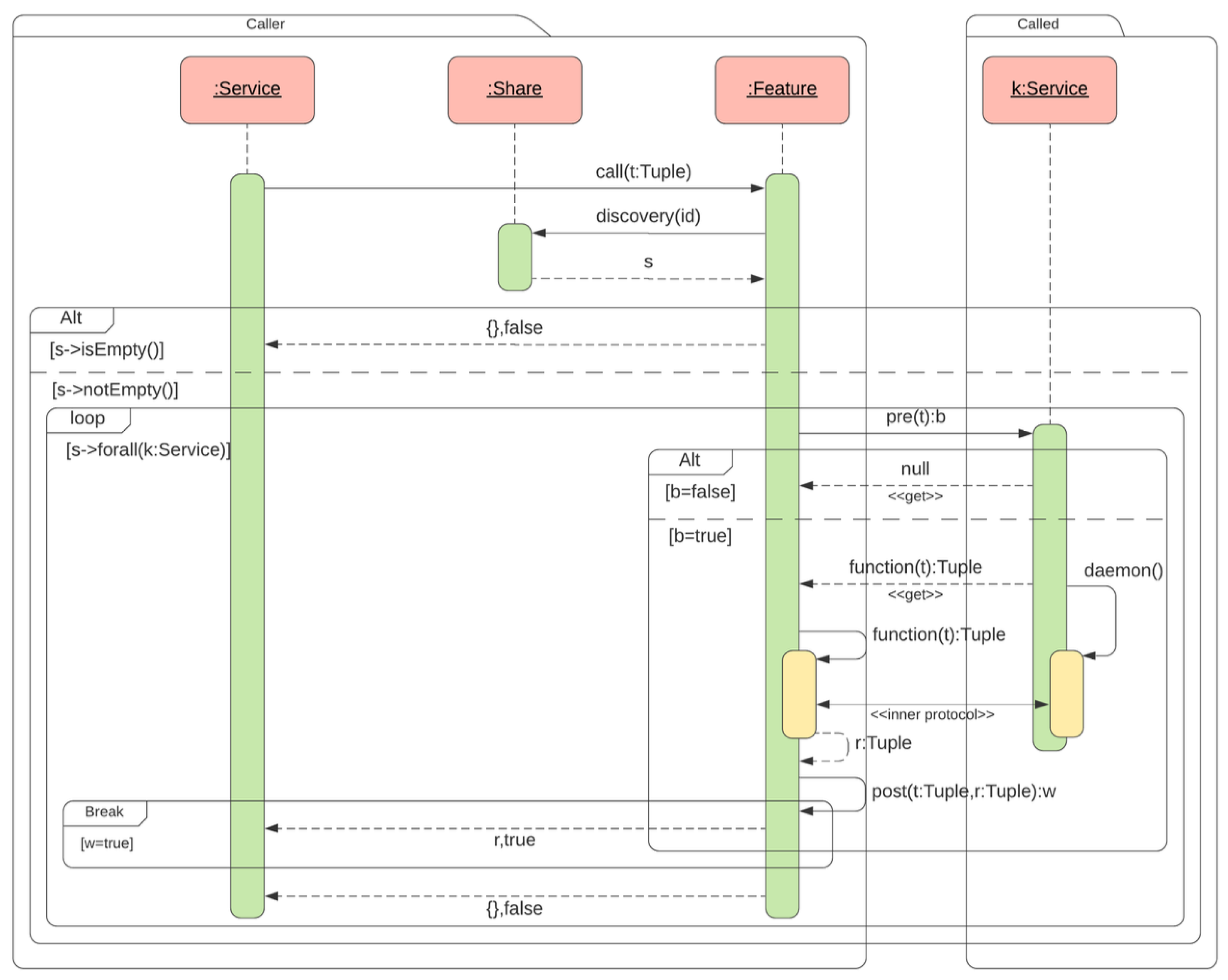

2.1. Sequence Diagram

It is imperative to acknowledge the pivotal function of sequence diagrams in modeling the interactions between disparate entities within a system. The utilization of these tools facilitates the representation of message exchange and the sequence of operations. This making them important tools for understanding and verifying the behavior of complex service-based architectures. In the context of this article, in the sequence diagram, it is possible to understand how Share dynamically invokes services according to predefined patterns. This ensures a seamless interaction between the distributed components.

In

Figure 2, the sequence diagram highlights the interactions between objects during a call to an

Service, in our case, the

temperature_alert service example. The process begins when the service

temperature_alert calls the method

call of the object

Feature. This object searches for a suitable service using an ID which corresponds to a certain pattern defined by

RExp (Regular Expression). This is done through the message

discover(id), which returns a set of

S objects

Service matching the identifier.

When no matching service is found,

S is empty and an error is returned. In contrast, when a service is found, the available one is evaluated sequentially in a loop, as is possible to observe inside the sequence diagram

Figure 2. Each service found has to follow a sequence of steps, first a

precondition check is performed (

pre(t): b to verify that the given input parameters satisfy the service requirements. Each time the

precondition of a service fails, the next one is checked until the

precondition is satisfied. The

daemon is invoked by the

feature object only if the service implementation is valid, and it uses a function stub for the call. In our case, analyzing the

temperature_check when the service is invoked, it evaluates the temperature and checks if it exceeds the threshold. Then, the service returns the result

r: Tuple and a status

w: boolean. The execution of the service is considered successful when the

w return true and the

Service call concludes. On the contrary, as mentioned above, the system continues to search for alternative services to meet all the conditions. This structured approach ensures flexibility, robustness, and allows

Share to dynamically adapt to different service implementations while maintaining a consistent execution flow.

2.2. Simulator Implementation

The utilization of simulators within the domain of the Internet of Things (IoT) is imperative for the evaluation and validation of novel models and architectures, obviating the necessity for immediate access to physical hardware. Simulators allow analyzing the behavior of systems in controlled scenarios, reducing costs and development time. Moreover, they are essential to assess the reliability and scalability of new solutions, especially in environments characterized by stringent constraints on memory, computing power, and energy.

A dedicated simulator was developed to validate the effectiveness of Share and test its applicability in resource-constrained IoT contexts. The aim is to verify how the design pattern manages the dynamic composition of services and ensures integration between heterogeneous devices. The simulator, implemented in LUA, enables the execution and monitoring of interactions between devices, simulating realistic environments. In addition, it exploits the Object Constraint Language (OCL) specification to ensure that composition constraints are respected, thus increasing the reliability of the system. The development of the simulator is facilitated by the utilization of the Lua programming language. [

19].

The choice of this programming language falls on several characteristics that make it perfect for implementation on embedded systems with limited resources. It is an efficient programming language with a very low weight (about 220KB). This characteristic makes it ideal for the systems we are dealing with. It is a multi-paradigm language capable of handling procedural, functional, and object-oriented programming, and this characteristic allows it to adapt to any context and development requirement. It is a very portable language because it is able to run on UNIX, Windows, IOS, Android, and, above all, on microcontrollers. The source code of the mentioned platforms is similar because Lua follows the ISO (ANSI) C standard, and thanks to this feature, there is no need to adapt the code to new environments, only the need for an ISO C compiler. It would be important to emphasize that when validating a simulation on a real system with the Share code written in Lua, it allows the reuse of the same code on embedded systems with certain precautions. For example, when reusing the simulation code in a real system, the communication-related parameters that differ from the simulation should be changed, but the code as a whole remains the same.

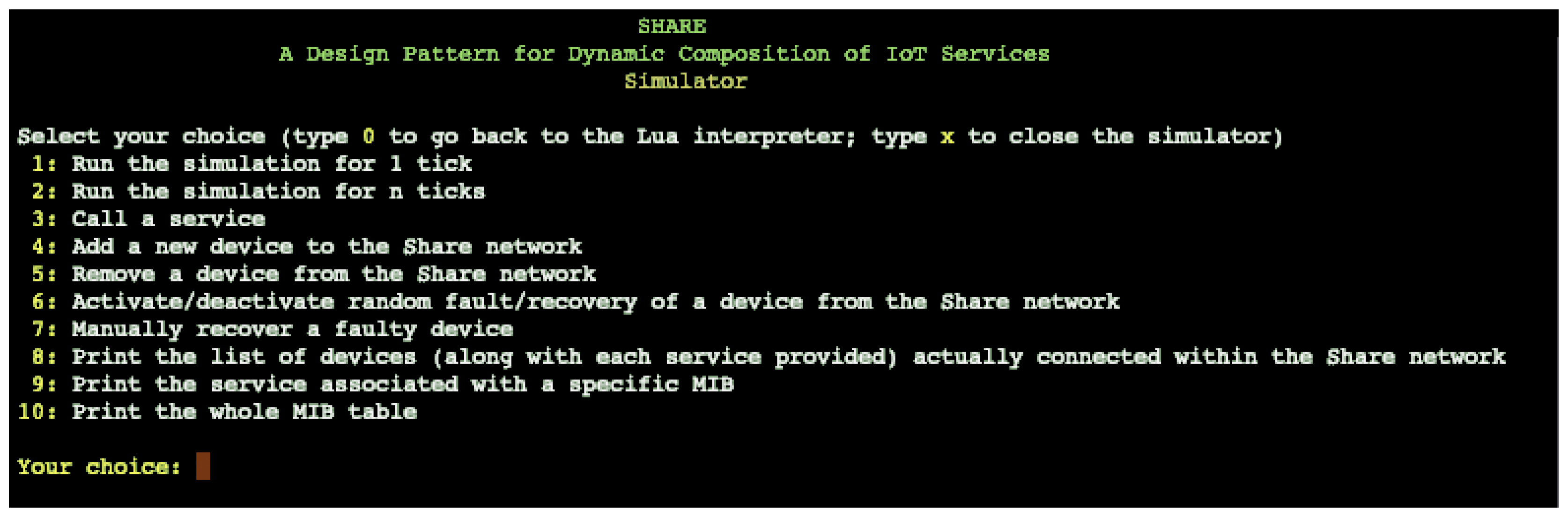

Figure 3.

Share: simulator view from terminal.

Figure 3.

Share: simulator view from terminal.

The simulator is run from the terminal via the Lua compiler and is presented as seen in Listing 3. The simulator offers different possibilities for use, which are indicated and usable via a numbered list from 1 to 10. The first two commands (1, 2) allow you to simulate 1 to n ticks to see the effects of the simulation over some time of your choice. Next in the list we have the interactions with the Share Network where it is possible to go and call a service (4), add or remove a device from the network (5, 6), manage issues that may arise and see how the system reacts through simulation (6, 7). Finally, with the last items in the list, we have the possibility of going to display the information of the Design Pattern Share by printing out the list of devices, the services with their MIB codes, or the entire table with the MIB codes.

2.3. Structure and Functionalities

As was the case in the preceding study [

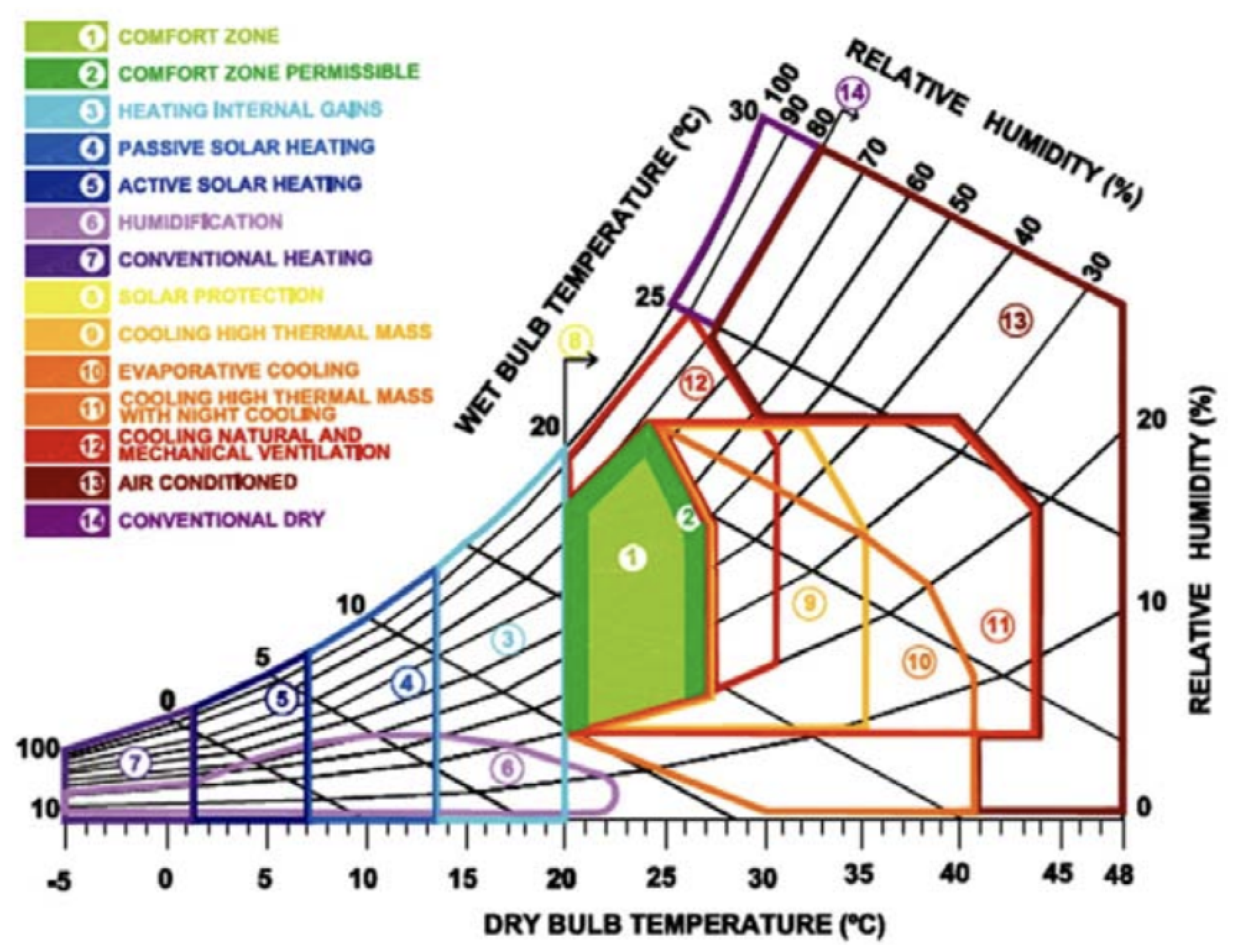

1], the present study places its focus on the example of the ideal climate inside a house. However, the present study will analyze the simulator instead of the generic case study defined by Baruch Givoni with his bioclimate-based graph [

10]. The simulator, written in Lua, uses coroutines via the standard Lua Coroutine library to facilitate portability and simulate the parallel execution of callers and callees. Coroutines in Lua allow functions to interrupt and later resume execution of the entire program without blocking it entirely, thanks to its lightweight and powerful mechanism for cooperative multitasking. While these coroutines may be regarded as analogous to conventional threads, they are distinct in their execution: coroutines share the same execution thread, and their operation is explicitly programmed by the programmer. This characteristic makes them particularly suitable for simulations and asynchronous control flows. The implementation of coroutines in Lua is regarded as a first-class value, signifying that they can be treated in a manner analogous to any other value, such as a number or string. Consequently, it is feasible to create a coroutine and store it within a variable or to pass it to a function. This feature allows developers to manage the execution state with minimal overhead, meaning that each coroutine keeps track of where it was paused (

coroutine.yield()) to resume it at another time (

coroutine.resume()). This feature makes it possible to pause and resume pieces of code with less complexity and resource cost than threads, making it perfect for implementation on systems with limited resources [

11].

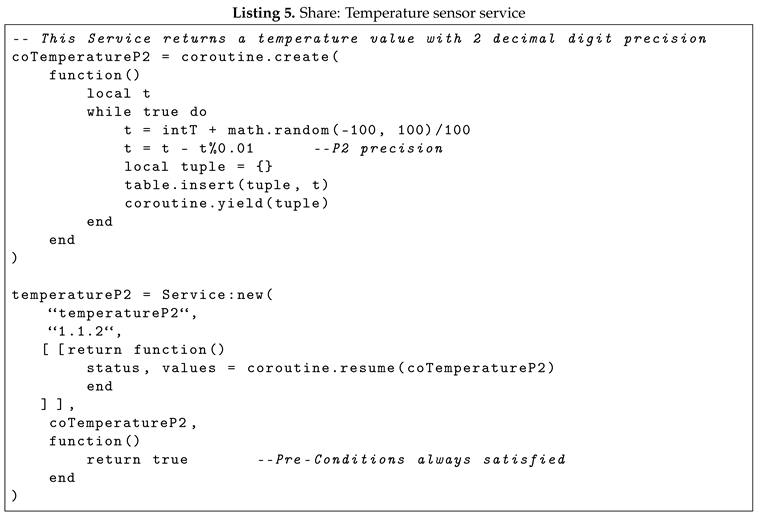

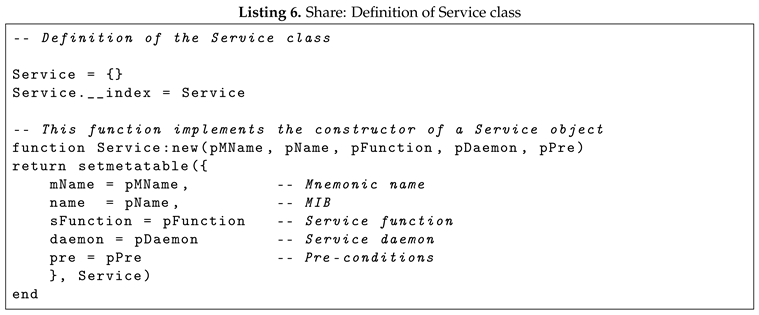

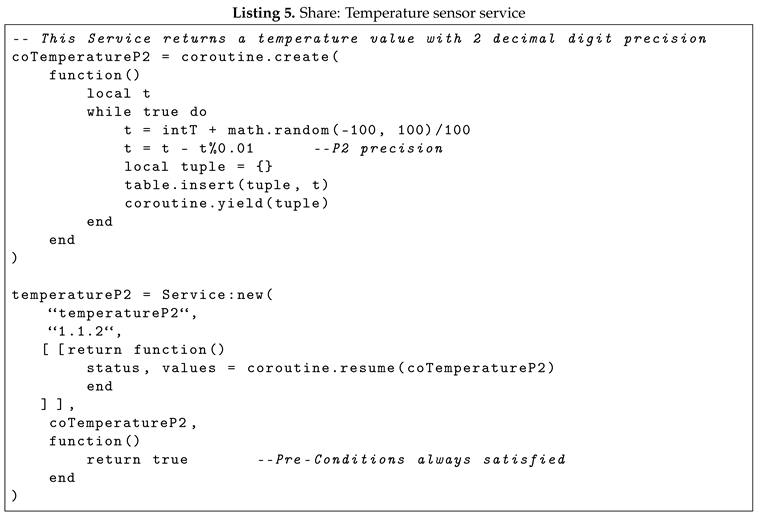

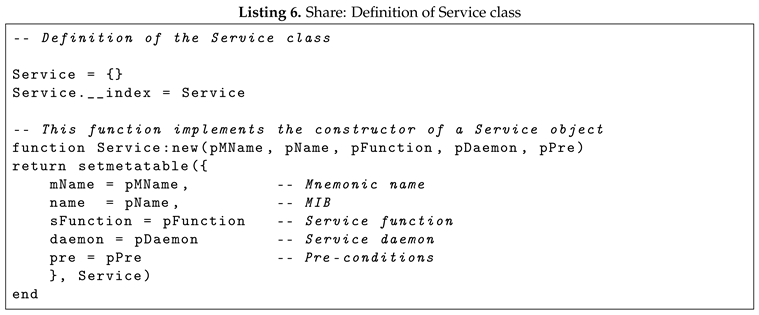

In our simulator the Service has been implemented using Lua coroutines as can be seen in the example Listing 5 the Service return a temperature value with 2 decimal digit precision and in Listing 6 we can see the implementation of the class definition.

Thanks to its modular structure, the simulator makes it easy to add new Services and their associated MIBs. Once the new Service has been added, it is possible to use it immediately in the simulator and go on to analyze the new scenarios that can be created with the use of the new service. The Share network is realized with a table where the keys are identified by their associated MIBs and the values are tables of Services. If we consider a real usage scenario, the mnemonic name can be the IP address or any other identifier that might work in a specific context. It is important to say that the values of Share network are tables of tables because each device within the network may offer more than one service, and because Lua does not know the concept of class. A salient feature of the simulator is its capacity for seamless transition between the simulation itself and the user agent. It is possible to pause the current simulation and resume it later without losing the current state. This can be achieved by switching to the interpreter and modifying the conditions in the environment in which Share is executing the simulation. Switching between the simulation and the user agent only performs a pause, so it is possible to start the simulation, make parameter adjustments, and then return to the simulation again and pick up where it left off.

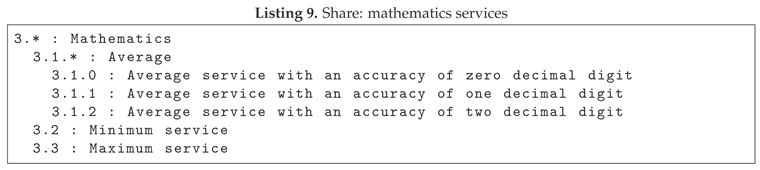

The simulator focuses on those solutions that require common equipment such as humidifiers, dehumidifiers, air conditioners, boilers, pellet stoves, heat pumps, etc. These appliances belong to the category of equipment that can be switched on or off, and each actuator can provide from one to several services. In the context of the ideal indoor climate introduced by Baruch Givoni, it is necessary for equipment to function in certain ways to raise or lower the temperature until the ideal temperature is reached, also taking into account the outside temperature. Taking common appliances such as air conditioners and boilers into consideration and relating them to services, we can see how a boiler can offer only one service while the air conditioner offers two. The boiler allows the temperature to be raised, while the air conditioner also allows the temperature to be lowered, and optionally the humidity to be lowered.

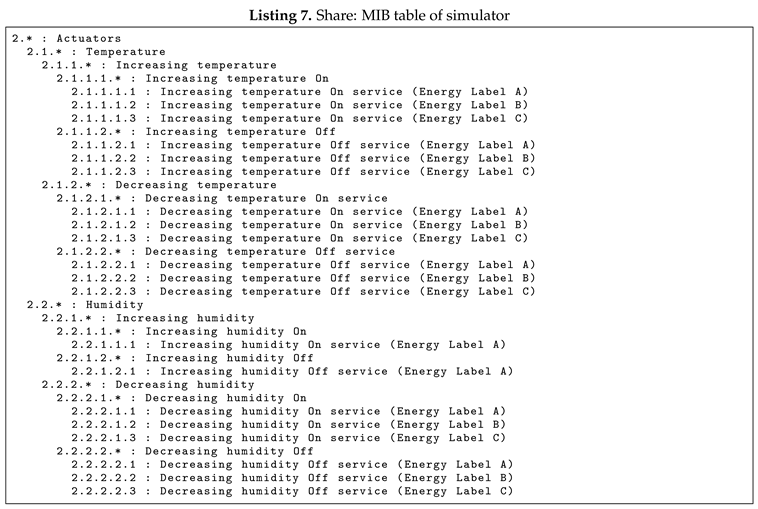

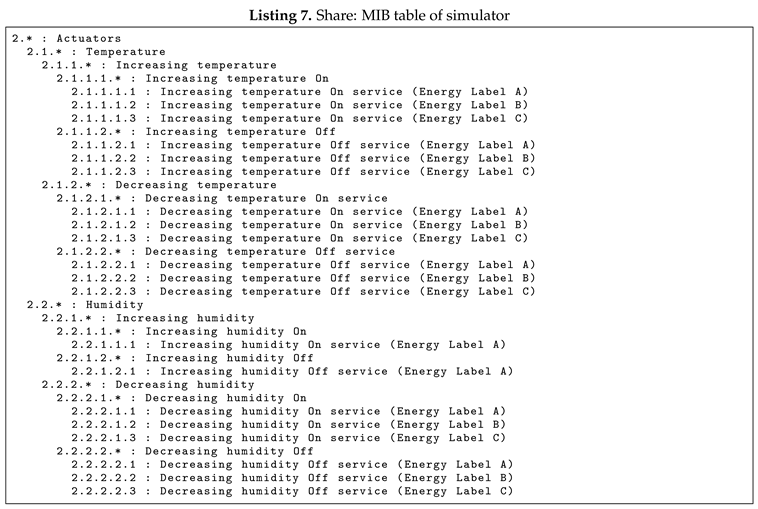

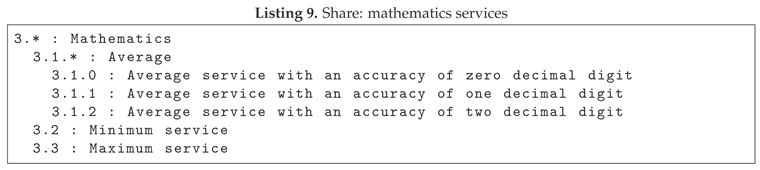

As mentioned earlier, when discussing the structure of the simulator and the services, we can group the

services into categories via a semantic relationship where the actuators have their way of providing the

services based on the European Union Energy Label [

21,

22]. For example, the service category decreasing humidity is identified as MIB 2.2.1.* but within it, there are several services related to the European label, as can be seen in Listing 7, which shows part of the MIB hierarchy table defined within the simulator.

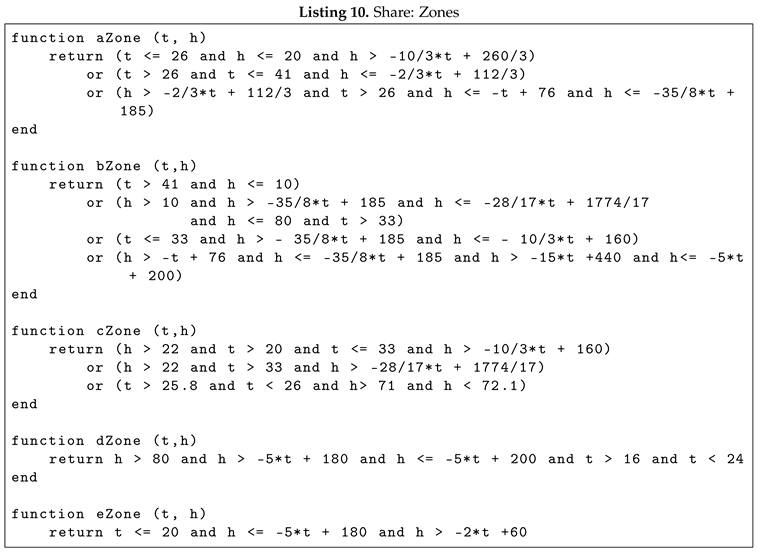

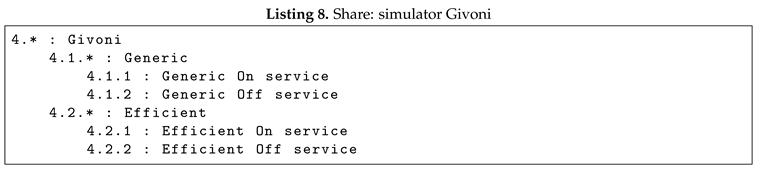

The Share pattern by consulting the network, Share network, enables the Service to base the decision on how many devices are connected at the moment by calling the whole category and possibly changing the behavior according to the available Services within the category. In Listing 8, it is possible to see how the simulator has two different Services to achieve the ideal temperature according to Baruch Givoni’s comfort zone theory: generic and efficient. Both use the services provided by the sensors and actuators as their features and in the first case, with the generic service, all available actuators within their categories are used with the sole purpose of reaching the desired comfort zone without thinking about energy consumption. Conversely, the efficient service is characterized by its consideration of energy efficiency and its utilization of actuators in a distinct manner. This approach aims to maintain energy consumption at the level stipulated by the established label. The energy-efficient service tries to minimize the energy consumed, in particular, it tries to use services with an energy efficiency label A and only use them. If it is not possible to use only those with the energy efficiency label A, it uses actuators with the lower energy efficiency label (B or C).

For a complete simulation of a complex distributed network, there are also Listing 9 mathematical services that are used to perform calculations on the actual system, where again we can find a similar situation to that for actuators, of having a variable amount of services available. Depending on the devices providing the various services, we can have a system that provides only the average, only the minimum, or only the maximum. Other situations allow for only two services, while other situations allow for all services to be available. The behavior of the caller may be based on these factors representing the Share network at a specific time.

Taking the service dealt with in Listing 3 as an example, its behavior can also be adapted to the scenarios that arise. If the Service needs to monitor the temperature to trigger a too-high (or too low) temperature alert and only has one temperature sensor available, this service will have to rely on the only available Service. If, on the other hand, this service has more than one temperature sensor at its disposal, it has the option of using mathematical Services such as average or minimum/maximum, or all three. Consequently, the system’s elasticity can be discerned. In the particular instance of the simulator, the parameters can be modified by introducing (or eliminating) the Services to observe the system’s response. This adjustment does not compromise the progress that has been accumulated. In the case of mathematical calculations, it is possible to suspend the simulator to remove (or add) Services and see how the behavior of the system changes.

Figure 4.

Baruch Givoni bioclimatic chart.

Figure 4.

Baruch Givoni bioclimatic chart.

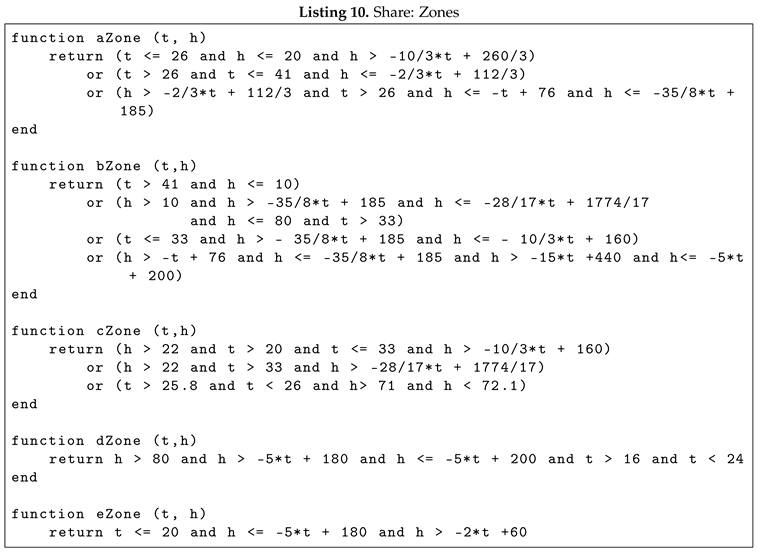

For the simulation, the Listing 4 Baruch Givoni for bioclimate was adjusted with the unit scale of degrees Celsius, replacing degrees Fahrenheit. It was then divided into zones, separating or joining one or more zones of the original chart. This was done based on the consideration of which actuators are required to reach the comfort zone about energy consumption, as can be seen in Listing 10. For example, if one were to consider a temperature T of T = 16°C and a humidity H of H = 20°C, to reach a comfort zone one would need to use an actuator that has a service that increases the temperature and another actuator that has a service that increases the humidity.

If one considers the case where T = 16°C and H = 60%, the need for the system is only related to the temperature, and one uses an actuator with the service that increases the temperature.

With Baruch Givoni’s bioclimatic graph, it can be seen that humidity and temperature are inversely proportional. During the simulation, we assume a closed environment, and this means that, applying mathematics, increasing the temperature leads to an indirect decrease in relative humidity. The absolute humidity, however, remains the same because we are talking about a closed environment. The estimate of the average proportion between the two is and indicates that as the temperature increases by 1°C, you decrease the percentage of relative humidity decreases by 4 points. The considerations that are made on the closed room simulation are also made based on the variation of the temperature outside the buildings. In the absence of active actuators, the indoor temperatures exhibit a high degree of dependence on the outdoor temperatures. The greater the disparity between indoor and outdoor temperatures, the more pronounced the temporal variation, which is manifested in the simulator as a change in the unit of measurement, referred to as a tick.

The direct work on humidity is different because actuators, such as humidifiers and dehumidifiers, act directly on absolute humidity, while on relative humidity, they act indirectly. In fact, by going to work on absolute humidity, relative humidity is also affected. Using an empirical estimate, the proportion between the change in relative humidity and temperature emerges as .

2.4. Formal Specification with OCL

In this subsection, we will address the simulator specifications with the support of the OCL language, before concluding with results and discussions.

The

Object Constraint Language (OCL) is a formal language that is used to describe expressions on UML models. In particular, it is used to specify constraints that cannot be represented directly using only graphical notations. OCL, which is introduced by the Object Management Group (OMG), is a part of the UML specification and assumes a very important role in model-driven engineering (MDE) to ensure accuracy and consistency within models [

12]. The OCL language allows developers to write expressions without side effects and allows the inclusion of invariants within classes, -pre and -post conditions on operations, and protections on transitions. Expressions are evaluated on model instances and do not change the state of the system. This makes OCL a declarative and secure language for the [

23] specification.

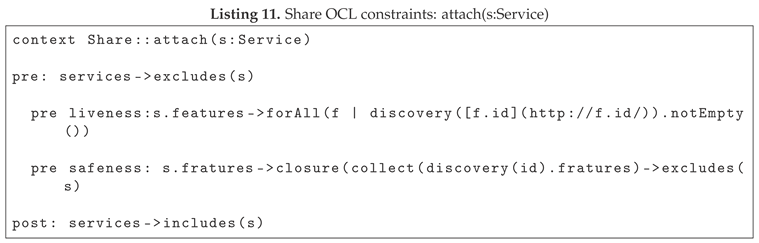

To ensure the correctness and consistency of the service offered by the Share pattern, it is necessary to specify formal constraints with the use of OCL following the standard format ISO/IEC 19507:2012 (OMG 2.3.1).

When a service is added to Share, verification of the system is crucial to prevent its consistency from being compromised. We can point to two fundamental conditions for this purpose, which are represented by liveness and safeness. The condition of liveness ensures that all the Features required by the Service are implementable. This means that for each Feature within the Service, there must be at least one Service capable of providing it. The constraint related to safeness serves to avoid circular dependencies that may arise during the composition of the Service, this is to ensure that the chain at a given time ends.

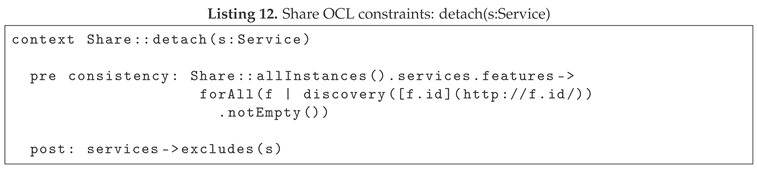

When a detach operation is performed, inconsistencies may be introduced into the system by breaking the conditions of liveness for other services. Before removing a service, it is essential to verify that the remaining services continue to satisfy their liveness constraints.

Our Share pattern assumes that at least one instance of Share exists in the system, although multiple instances of it are possible. Each Feature object performs queries on the Share repository to find the Service that satisfies its functionality, and in particular, there is no structural dependency between Feature and Share. This feature allows a certain flexibility of implementation on the creation of services such as Publish/Subscribe present in the MQTT protocol. To ensure ease of use, the implementation of Share could be bound to a specific architectural development. For example, in a smart home scenario, the Share pattern could be implemented as a singleton within a central device, such as a WiFi router that supports SNMP services. Some home routers within the low-cost end of the market, such as the GL.iNet GL-AR300M16-Ext and GL.iNet GL-X750, have the OpenWrt operating system already pre-installed, and this Linux-based open source operating system is optimized specifically for network devices [OpenWrt]. Using OpenWrt, it is possible to execute customized user services directly on the router, making it possible to realize operations such as attach and detach as network-accessible services. This gives home automation devices the possibility of automatically registering with the Share service repository the moment they connect to the network. Finally, the centralized management of Share on the router offers the possibility of monitoring the availability of devices by performing implicit detach operations in the event of a disconnect from WiFi.