Background

Agriculture remains the main source of livelihood for majority of the population in Uganda [

1], employing approximately 65% of the working population and of this, 63% are youth [

2]. In regards to Uganda’s economy, agriculture contributes significantly to national income, generating 24% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and accounting for 54% of the country’s export earnings [

3]. The major cereal crops grown in Africa include; maize, sorghum, pearl millet, finger millet, wheat, and rice [

4]. The total production of rice in Uganda is estimated at 238,000 metric tons while the total rice consumption is estimated at 346,309 metric tons giving the deficit of 103,309 metric tons per year, which is made up through importation [

5]. Rice has been considered as a highly strategic and priority commodity for food security in Africa and its demand is expected to increase by 30 million metric tons by the year 2035, a value equivalent to 130% increase in rice consumption [

6]. This projection is due to the high population growth, which is expected to increase to 48% by 2030, rapid urbanization and changes in population eating habits [

7]. In 2006, the Abuja Food Security Summit, organized by the African Union, declared rice as a region-wide strategic commodity and noted its importance in Africa’s agricultural sector [

8]. Globally, rice gained popularity over the past years and became one of the world’s most important cereal crop and hence, playing a significant role in achieving global food security [

9,

10].

Oerke [

11], highlighted that, 15% of global rice production is lost to animal pests (arthropods, nematodes, rodents, birds, slugs and snails). Furthermore, the Global Rice Science Partnership (GRiSP) identified birds as the second most important biotic constraint in African’s rice production industry after weeds [

12]. These birds mostly feed on rice during the milking stage by sucking all the sugary semi-liquid substance in pods leaving them completely empty [

13]. The “milking” stage refers to the period, usually lasting around two weeks after flowering, when the grains are being filled out by a milky white substance. The red-billed quelea (Quelea quelea) have been cited as the most notorious pest bird species in the world, causing massive damage to rice crops and gathers in flocks of million birds [

14]. These are the most abundant species worldwide with their population totaling to about 1.5 billion at the end of the breeding seasons [

15,

16]. The Food Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated the losses contributed by the quelea birds annually in Africa alone at about US

$50 million [

17]. The Uganda National Rice Development Strategy (UNRDS) was formed in 2008 to improve rice productivity through modern rice cultivation, utilization of fertilizers, and minimizing post-harvest losses among other interventions [

18].

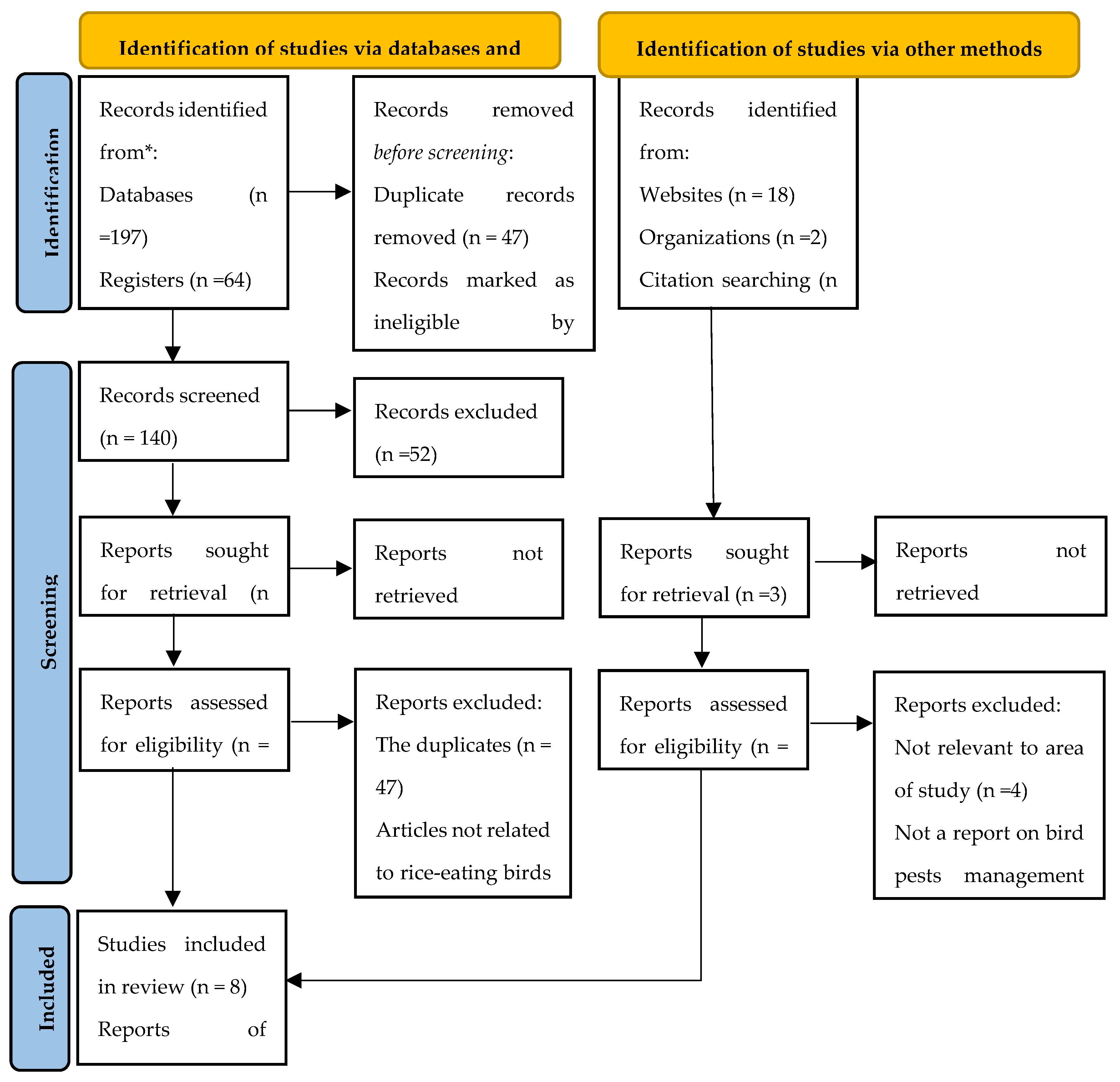

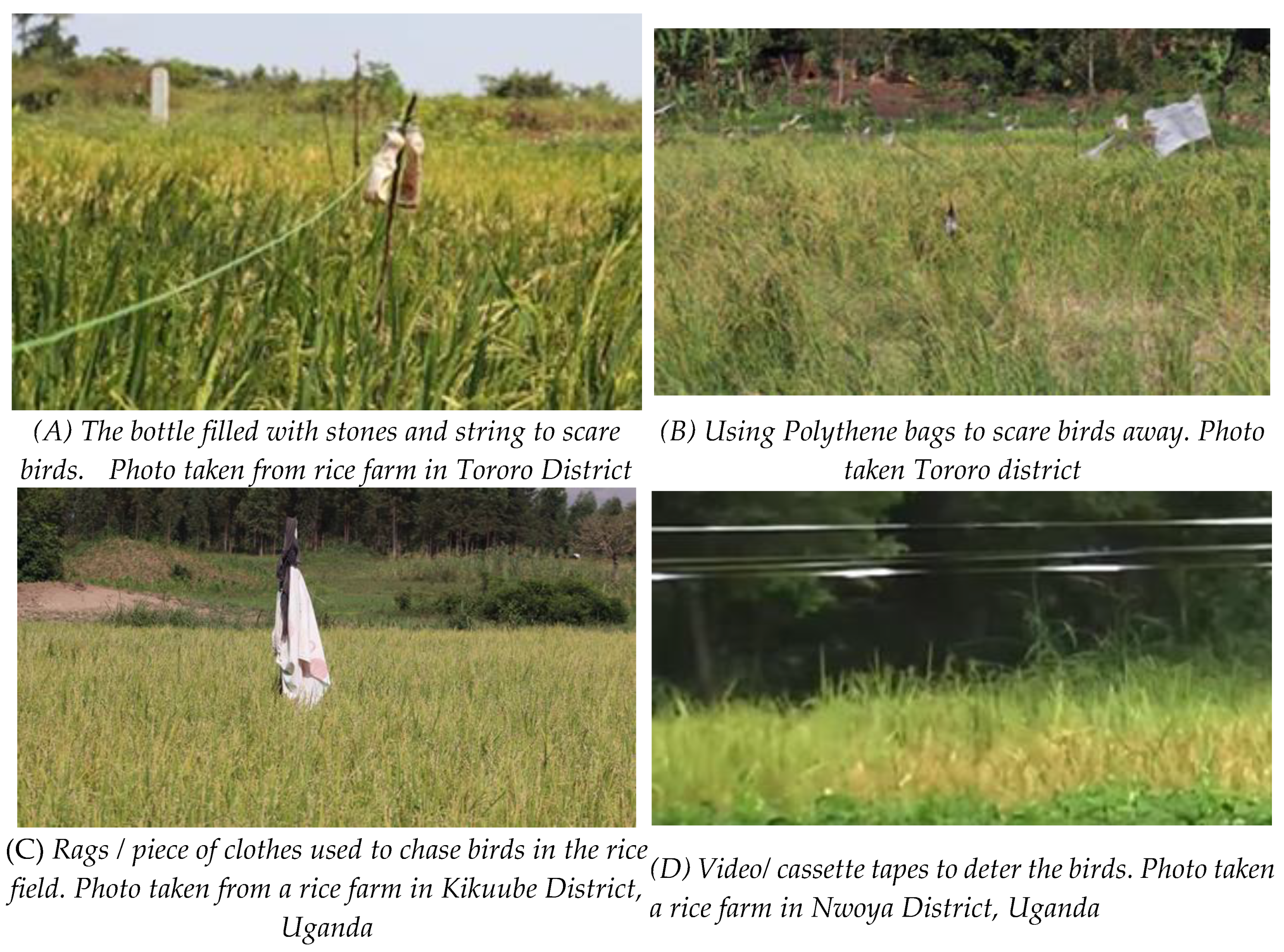

In the rice production cycle, bird pests management has been given limited attention, and this neglect by has led farmers to maintain the traditional, tedious and laborious way of deterring birds from rice fields [

19]. Traditional and low-cost methods used to minimize damage by birds on the rice crop are categorized as preventive or protective methods. Preventive methods aim at controlling the birds from being attracted to the rice field while protective methods focus on protecting the rice crops from being damaged by birds [

20]. The Preventive methods are sub-divided into lethal and non-lethal techniques, where lethal techniques aim at suppressing bird populations such as manual nest destruction, killing of birds, and use of explosives. Non-lethal techniques on the other hand include agronomic practices such as vegetation management, weed management practices, proper planning of the planting seasons and choosing bird-resistant rice varieties among others[

20]. Protective methods include use of repellents (chemical substances), protecting fields with nets, and manual bird-scaring efforts [

21]. Traditional protective methods such as manual bird scaring, flags and scarecrows provide satisfactory protection on small-scale or privately owned fields when number of birds are relatively low. However, as the number of birds increases, these methods become ineffective [

22]. These traditional practices employ the efforts of women and children to manually scare the birds, hence, additional burden to women’s domestic activities and children suffer from increased school absenteeism and dropout [

23]. In 2020, Pallisa district in Uganda registered a high percentage (60%) of pupil’s absenteeism and school dropout during rice milking and harvesting periods due to substituting children for cheap labor in rice fields [

23] which led to poor performance in the respective schools. In 2013, the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF) under Desert Locust Control Organization for East Africa (DLCO-EA) used an aircraft to spray quelea birds with Fenthion avicide in Kibimba rice scheme in Bugiri district, Uganda, which killed over 2 million quelea birds [

24]. This intervention violated Uganda National Environment Management Authority’s (NEMA) guidelines on environment and human health impact assessment, which prohibits the spraying and killing of birds as a means to bird pest management practice [

25]. The traditional bird management practices are summarized (

Figure 1).

However, with recent technologies, systems have been developed to deter birds from cereal crop fields, while using sound, video, image and motion, body-heat detection mechanisms. Steen et al [

27], developed a disruptive stimuli tool that successfully reduced the presence of geese at a distance of 200 meters away from the scaring device using distress calls. A real time image processing bird repellent system using video cameras for motion detection of objects flying over or passing by the protected area was proposed [

28,

29,

30]. Ezeonu et al. [

29] developed an ultrasonic bird repellent system, which used ultrasonic waves to generate varying frequencies between 15 kHz and 25 kHz, to give an impression to birds that many birds are captured, and injured. However, according to Gilsdorf [

31], many devices that use sound to deter birds cause serious conflicts among the habitants and birds can easily adapt to a given sound over a period of time hence no longer scare them.

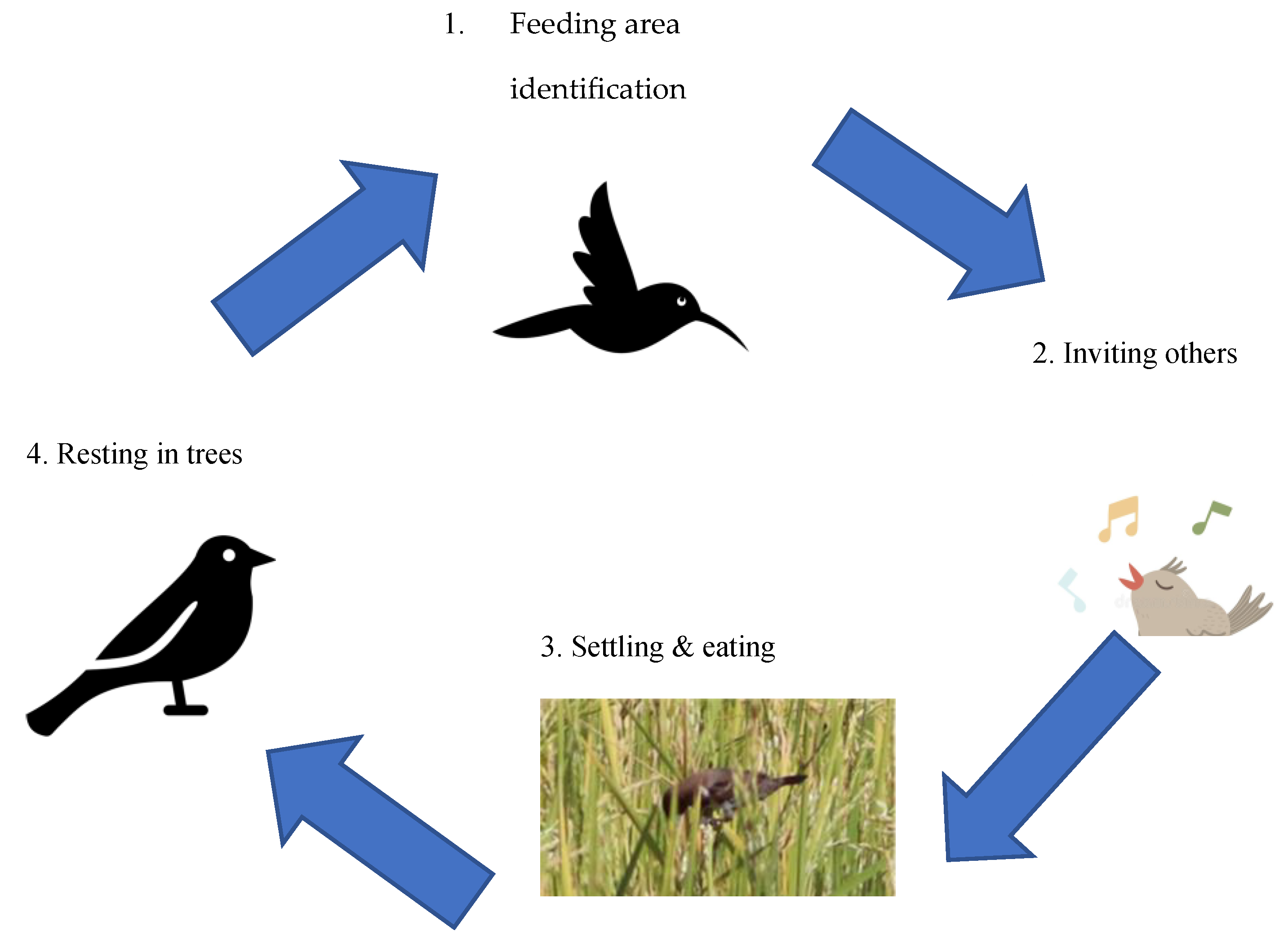

The efficacy of these systems is still questionable due to the intelligence of the birds characterized by their adaptation to the environments and rendering the available interventions ineffective. A thorough understanding of the behavior of these birds is key to improve the efficacy of the management practices employed. To our knowledge, no studies have been made towards understanding the behaviors of these pests in order to tailor the systems to their characteristics. In this paper therefore, we studied the behaviors of the bird pests with an aim of understanding their implication on the design of the systems that detect and deter the bird pests with no human intervention.

The study sought to achieve the following objectives

To explore bird pest management practices employed by local communities in the three selected rice-growing regions

To assess the prevalence of bird species in the three rice growing regions of Uganda.

To synthesize the current approaches used to manage bird pests in rice growing areas in Uganda.

To design a model for an optimal bird pest management strategy

To achieve the above objectives, key questions were asked to guide the research survey:

Which type of birds are the most common and destructive in the rice fields?

What are the common methods used to manage bird pests in rice growing regions in Uganda.

What is the observable characteristics of these birds?