Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Samples Collection

2.3. Sample Preparation

2.4. GC-MS Detection

2.5. Method Validation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

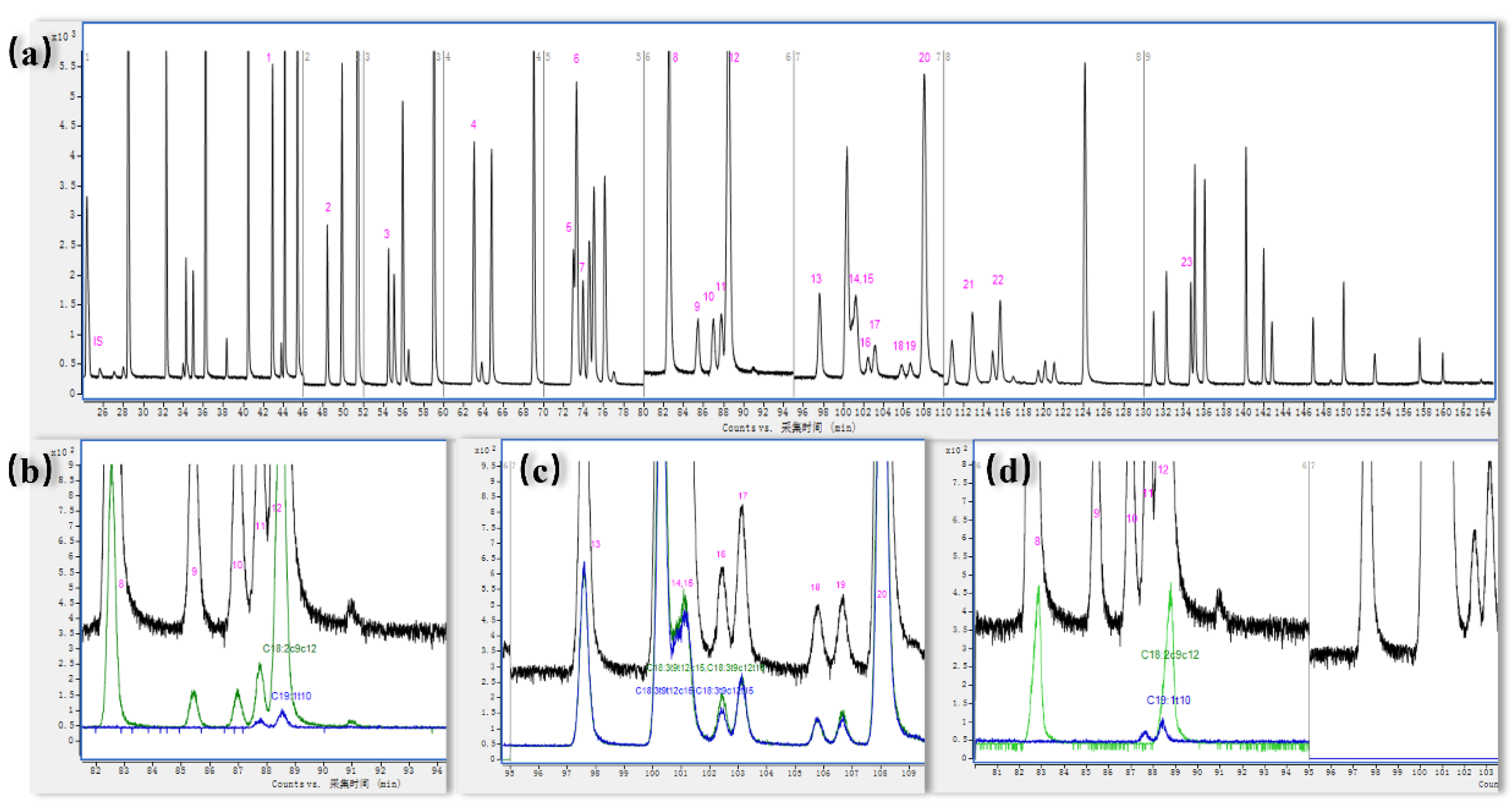

3.1. Chromatographic Separation of 23 Kinds of TFAMEs

3.2. Method Validation

3.3. The Profile of TFAs in Edible Oil

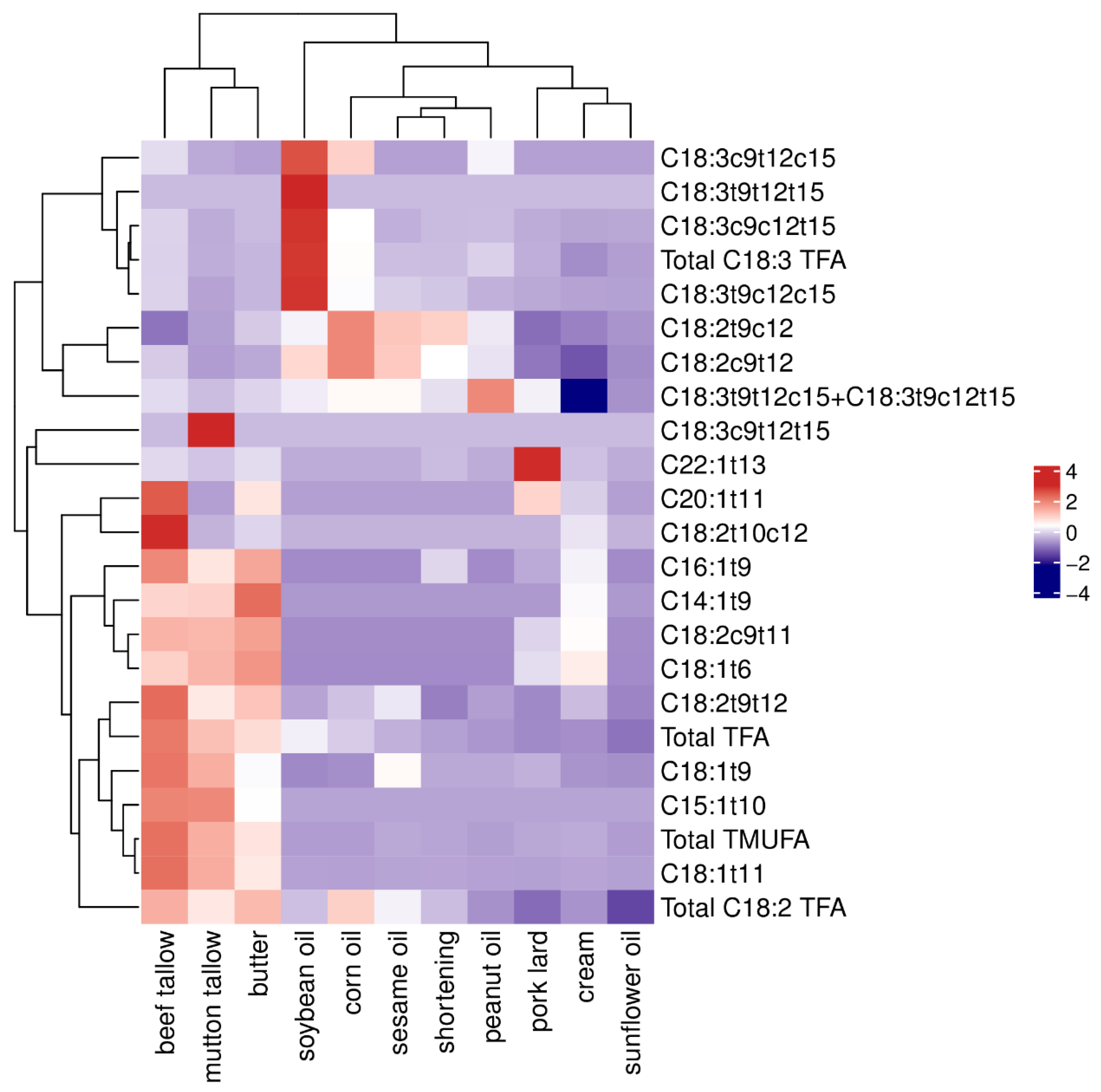

3.4. Cluster Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Lock, A.L.; Parodi, P.W.; Bauman, D.E. The Biology of Trans Fatty Acids: Implications for Human Health and the Dairy Industry. Aust. J. Dairy Technol. 2005, 60, 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Enjalbert, F.; Zened, A.; Cauquil, L.; Meynadier, A. Integrating Data from Spontaneous and Induced trans-10 Shift of Ruminal Biohydrogenation Reveals Discriminant Bacterial Community Changes at the OTU Level. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1012341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niforou, A.; Magriplis, E.; Klinaki, E.; Niforou, K.; Naska, A. On Account of Trans Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease Risk - There Is Still Need to Upgrade the Knowledge and Educate Consumers. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 32, 1811–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larqué, E.; García-Ruiz, P.A.; Perez-Llamas, F.; Zamora, S.; Gil, A. Dietary Trans Fatty Acids Alter the Compositions of Microsomes and Mitochondria and the Activities of Microsome Δ6-Fatty Acid Desaturase and Glucose-6-Phosphatase in Livers of Pregnant Rats. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 2526–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, K.A.; Arnold, T.; Rasool, T.; Antalis, C.; Miller, S.J.; Siddiqui, R.A. Trans-Fatty Acids Induce Pro-Inflammatory Responses and Endothelial Cell Dysfunction. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pase, C.S.; Bürger, M.E. Trans Fat Intake and Behavior. In The Molecular Nutrition of Fats; Academic Press, 2019; pp. 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, T.; Guo, J.; Zhao, T.; Tang, H.; Jin, K.; et al. Abnormal Erythrocyte Fatty Acid Composition in First-Diagnosed, Drug-Naïve Patients with Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 318, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, D.J.; Judd, J.T.; Clevidence, B.A.; Tracy, R.P. Dietary Fatty Acids Affect Plasma Markers of Inflammation in Healthy Men Fed Controlled Diets: A Randomized Crossover Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 969–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupkin, M.; Zambelli, A. Detrimental Impact of Trans Fats on Human Health: Stearic Acid-Rich Fats as Possible Substitutes. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2008, 7, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Policies to Eliminate Industrially Produced Trans-Fat Consumption; WHO/NMH/NHD/18.5; WHO: Geneva, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Chen, M.; Luo, R.; et al. Fatty Acid Profiles of Milk from Holstein Cows, Jersey Cows, Buffalos, Yaks, Humans, Goats, Camels, and Donkeys Based on Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 20750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amores, G.; Virto, M. Total and Free Fatty Acids Analysis in Milk and Dairy Fat. Separations 2019, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, J.K.C.; Fellner, V.; Dugan, M.E.R.; Sauer, F.D.; Mossoba, M.M.; Yurawecz, M.P. Evaluating Acid and Base Catalysts in the Methylation of Milk and Rumen Fatty Acids with Special Emphasis on Conjugated Dienes and Total Trans Fatty Acids. Lipids 1997, 32, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Precht, D.; Molkentin, J.; Vahlendieck, M. Influence of the Heating Temperature on the Fat Composition of Milk Fat with Emphasis on cis-/trans-Isomerization. Nahrung 1999, 43, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Lamas, L.; Aldai, N.; Kramer, J.K.G.; Barron, L.J.R. Case Study Using Commercial Dairy Sheep Flocks: Comparison of the Fat Nutritional Quality of Milk Produced in Mountain and Valley Farms. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 89, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momchilova, S.M.; Nikolova-Damyanova, B.M. Advances in Silver Ion Chromatography for the Analysis of Fatty Acids and Triacylglycerols - 2001 to 2011. Anal. Sci. 2012, 28, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Precht, D.; Molkentin, J.; Destaillats, F.; Wolff, R.L. Comparative Studies on Individual Isomeric 18:1 Acids in Cow, Goat, and Ewe Milk Fats by Low-Temperature High-Resolution Capillary Gas-Liquid Chromatography. Lipids 2001, 36, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Alcala, L.M.; Alonso, L.; Fontecha, J. Stability of Fatty Acid Composition after Thermal, High Pressure, and Microwave Processing of Cow Milk as Affected by Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Concentration. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 7307–7315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, S.; Shaheen, N.; Ashraf, M.M.; et al. Fatty Acid Profile Emphasizing Trans-Fatty Acids in Commercially Available Soybean and Palm Oils and Its Probable Intake in Bangladesh. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 4, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Cao, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Deng, T.; Lin, J.; Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Liu, A. The Assessment of Trans Fatty Acid Composition in Edible Oil of Different Brands and Regions in China in 2021. Food Chem. 2021, 345, 128861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, R.; Pierce, G.N. The Toxicity of Dietary Trans Fats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015, 78, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovič, H.; Vidrih, R.; Zlatić, E.; et al. Trans Fatty Acids in Margarines and Shortenings in the Food Supply in Slovenia. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018, 73, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, C.J.; Blewett, H.H.; Proctor, S.; Vine, D. Human Health Benefits of Vaccenic Acid. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2009, 34, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett, C.M.; Edel, A.L.; Patenaude, A.F.; et al. Dietary Vaccenic Acid Has Antiatherogenic Effects in LDLr-/- Mice. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; et al. Simultaneous Determination of C18 Fatty Acids in Milk by GC-MS. Separations 2021, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, F.; Wang, P.; Yang, L.; Ma, Y.; Day, L. Quantification of Fatty Acids in Human, Cow, Buffalo, Goat, Yak, and Camel Milk Using an Improved One-Step GC-FID Method. Food Anal. Methods 2017, 10, 2881–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aal, Y.A.A.; Abdel-Fattah, D.M.; Ahmed, K.E.D. Some Biochemical Studies on Trans Fatty Acid-Containing Diet. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019, 13, 1753–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlanov, U.; Czaja, T.P.; Nuriddinov, S.; et al. The Effects of Industrial Processing and Home Cooking Practices on Trans-Fatty Acid Profiles of Vegetable Oils. Food Chem. 2025, 469, 142571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Trans Fatty acid (TFA) |

Windows (No.) |

Retention time (min) |

Quantitative Ion (m/z) |

Qualitative ion (m/z) |

Dwell time (ms) |

LOQ (ppb) |

Linearity range (ppb) |

Standard curve regression equation (ppb) |

R2 | FAME-FA Conversion coefficient |

||

| IS | C10:1 c4 | 1 | 25.8 | 74 | 110 | 152 | 96 | 12 | / | / | / | / | / |

| 1 | C14:1 t9 | 42.9 | 166 | 87 | 74 | 208 | 12 | 10 | 5-250 | Y=2.1238x-22.6676 | 0.9998 | 0.9417 | |

| 2 | C15:1 t10 | 2 | 48.4 | 74 | 69 | 180 | 222 | 12 | 10 | 5-250 | Y=11.5450x-131.148 | 0.9996 | 0.9449 |

| 3 | C16:1 t9 | 3 | 54.43 | 194 | 69 | 74 | 236 | 12 | 10 | 5-250 | Y=6.5063x-250.9835 | 0.9997 | 0.9477 |

| 4 | C17:1 t10 | 4 | 62.9 | 208 | 74 | 69 | 250 | 12 | 20 | 10-500 | Y=1.5149x-76.8526 | 0.9991 | 0.9503 |

| 5 | C18:1 t6 | 5 | 72.7 | 74 | 69 | 222 | 264 | 12 | 20 | 10-500 | Y=9.0349x-405.8 | 0.9993 | 0.9527 |

| 6 | C18:1 t9 | 73.0 | 74 | 69 | 222 | 264 | 12 | 10 | 5-250 | Y=38.7466x-763.8356 | 0.9998 | ||

| 7 | C18:1 t11 | 73.7 | 74 | 69 | 222 | 264 | 12 | 30 | 15-3000 | Y=3.5880x-174.2697 | 0.9991 | ||

| 8 | C18:2 t9t12 | 6 | 82.4 | 294 | 67 | 81 | 263 | 10 | 10 | 125-5000 | Y=11.9951x-6754.5248 | 0.9994 | 0.9524 |

| 9 | C18:2 c9t12 | 85.3 | 294 | 67 | 81 | 263 | 10 | 10 | 50-2000 | Y=10.3814x-3425.0548 | 0.9991 | ||

| 10 | C18:2 t9c12 | 86.9 | 294 | 67 | 81 | 263 | 10 | 10 | 50-2000 | Y=9.6048x+3268.9916 | 0.9990 | ||

| 11 | C19:1 t7 | 87.1 | 278 | 74 | 236 | 194 | 10 | 10 | 5-250 | Y=0.7035x+0.4895 | 0.9991 | 0.9548 | |

| 12 | C19:1 t10 | 88.0 | 278 | 69 | 236 | 194 | 10 | 20 | 10-500 | Y=0.9160x-65.8606 | 0.9994 | ||

| 13 | C18:3 t9t12t15 | 7 | 97.7 | 79 | 67 | 121 | 292 | 8 | 60 | 75-1500 | Y=12.0283x-8181.0863 | 0.9995 | 0.9520 |

| 14 | C18:3 t9t12c15 | 101.2 | 79 | 67 | 121 | 292 | 8 | 60 | 75-1500 | Y=10.2026x-649.0786 | 0.9990 | ||

| 15 | C18:3 t9c12t15 | ||||||||||||

| 16 | C18:3 c9c12t15 | 102.6 | 79 | 67 | 121 | 292 | 8 | 20 | 17.5-3500 | Y=10.2953x-1140.8669 | 0.9994 | ||

| 17 | C18:3 c9t12t15 | 103.2 | 79 | 67 | 121 | 292 | 8 | 40 | 37.5-750 | Y=7.3719x-1904.6952 | 0.9993 | ||

| 18 | C18:3 c9t12c15 | 106.0 | 79 | 67 | 121 | 292 | 8 | 20 | 17.5-350 | Y=8.0243x-1368.4318 | 0.9991 | ||

| 19 | C18:3 t9c12c15 | 106.8 | 79 | 67 | 121 | 292 | 8 | 20 | 17.5-3500 | Y=10.2532x-1452.9265 | 0.9994 | ||

| 20 | C20:1 t11 | 107.2 | 250 | 69 | 208 | 292 | 8 | 20 | 20-1000 | Y=0.3553x-1.5752 | 0.9994 | 0.9568 | |

| 21 | C18:2 c9t11 | 8 | 113.0 | 294 | 67 | 81 | 149 | 8 | 20 | 10-2000 | Y=0.6747x-718.5914 | 0.9991 | 0.9524 |

| 22 | C18:2 t10c12 | 115.8 | 294 | 67 | 81 | 149 | 8 | 20 | 10-2000 | Y=0.5267x-467.0668 | 0.9995 | ||

| 23 | C22:1 t13 | 9 | 134.4 | 74 | 69 | 320 | 236 | 8 | 10 | 5-250 | Y=0.5267x-467.0668 | 0.9995 | 0.9602 |

| Trans Fatty acid (TFA) |

Concentration multiple | Sunflower oil | Pork lard | ||||||||||||

| 25 mg/kg | 100 mg/kg | 200 mg/kg | 25 mg/kg | 100 mg/kg | 200 mg/kg | ||||||||||

| Recovery (%) |

CV (%) |

Recovery (%) |

CV (%) |

Recovery (%) |

CV (%) |

Recovery (%) |

CV (%) |

Recovery (%) |

CV (%) |

Recovery (%) |

CV (%) |

||||

| C14:1 t9 | 1 | 82.5 | 5.1 | 87.8 | 4.5 | 89.2 | 6.4 | 83.4 | 7.7 | 84.2 | 3.5 | 89.7 | 4.9 | ||

| C15:1 t10 | 1 | 83.2 | 4.2 | 85.3 | 4.6 | 89.8 | 7.5 | 81.2 | 6.2 | 83.4 | 4.3 | 88.4 | 7.2 | ||

| C16:1 t9 | 1 | 86.5 | 8.5 | 86.4 | 6.5 | 88.7 | 4.6 | NA | |||||||

| C17:1 t10 | 2 | 85.4 | 4.6 | 85.4 | 4.6 | 90.2 | 5.5 | 81.5 | 4.4 | 85.2 | 5.6 | 89.7 | 8.9 | ||

| C18:1 t6 | 2 | 89.7 | 8.9 | 83.6 | 4.4 | 91.4 | 4.1 | NA | |||||||

| C18:1 t9 | 1 | NA | NA | ||||||||||||

| C18:1 t11 | 3 | NA | NA | ||||||||||||

| C18:2 t9t12 | 5 | NA | NA | ||||||||||||

| C18:2 c9t12 | 2 | NA | NA | ||||||||||||

| C18:2 t9c12 | 2 | NA | NA | ||||||||||||

| C19:1 t7 | 1 | 88.7 | 3.8 | 89.7 | 6.9 | 90.2 | 8.6 | 79.3 | 3.5 | 81.2 | 7.2 | 89.9 | 3.6 | ||

| C19:1 t10 | 2 | 83.5 | 4.5 | 88.2 | 7.1 | 89.7 | 3.5 | 78.5 | 4.7 | 82.2 | 6.9 | 91.3 | 4.7 | ||

| C18:3 t9t12t15 | 4 | 84.3 | 7.3 | 88.6 | 5.4 | 91.5 | 7.4 | 81.2 | 5.1 | 83.6 | 4.6 | 91.3 | 7.3 | ||

| C18:3 t9t12c15 | 4 | NA | NA | ||||||||||||

| +C18:3 t9c12t15 | |||||||||||||||

| C18:3 c9c12t15 | 1 | NA | NA | ||||||||||||

| C18:3 c9t12t15 | 2 | 79.6 | 5.4 | 83.5 | 3.5 | 91.2 | 6.2 | 83.6 | 7.4 | 88.1 | 2.3 | 90.2 | 6.7 | ||

| C18:3 c9t12c15 | 1 | 88.1 | 5.5 | 89.7 | 2.4 | 90.6 | 9.1 | 82.4 | 3.8 | 85.7 | 3.8 | 92.6 | 3.8 | ||

| C18:3 t9c12c15 | 1 | NA | NA | ||||||||||||

| C20:1 t11 | 1 | 75.4 | 5.3 | 79.8 | 5.3 | 86.5 | 3.7 | NA | |||||||

| C18:2 c9t11 | 4 | 81.5 | 6.6 | 85.5 | 4.3 | 85.4 | 5.9 | NA | |||||||

| C18:2 t10c12 | 4 | 82.3 | 3.8 | 83.7 | 2.9 | 86.4 | 8.6 | 83.3 | 4.0 | 86.9 | 3.9 | 90.6 | 3.7 | ||

| C22:1 t13 | 1 | 79.6 | 4.2 | 81.3 | 3.7 | 85.1 | 4.9 | NA | |||||||

| Trans Fatty acid (TFA) |

Soybean oil n=13 |

Peanut oil n=22 |

Coil oil n=15 |

Sunflower oil n=14 |

Sesame oil n=17 |

Pork lard n=18 |

Beef tallow n=11 |

Mutton tallow n=12 |

Butter n=20 |

Cream n=17 |

Shortening n=11 |

| C14:1 t9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.009±0.002 | 0.009±0.004 | 0.017±0.008 | 0.006±0.003 | ND |

| C15:1 t10 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.008±0.003 | 0.008±0.003 | 0.003±0.003 | ND | ND |

| C16:1 t9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.014±0.003 | 0.122±0.051 | 0.067±0.035 | 0.105±0.085 | 0.046±0.054 | 0.034±0.011 |

| C17:1 t10 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| C18:1 t6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.034±0.014 | 0.074±0.081 | 0.090±0.063 | 0.107±0.105 | 0.058±0.045 | ND |

| C18:1 t9 | 0.027±0.016 | 0.056±0.026 | 0.033±0.014 | 0.033±0.022 | 0.143±0.043 | 0.063±0.024 | 0.303±0.136 | 0.235±0.126 | 0.131±0.143 | 0.037±0.022 | 0.056±0.019 |

| C18:1 t11 | 0.022±0.013 | 0.022±0.019 | 0.012±0.004 | 0.016±0.008 | 0.041±0.025 | 0.019±0.021 | 2.538±1.050 | 1.840±0.708 | 1.120±0.620 | 0.059±0.039 | 0.055±0.045 |

| C18:2 t9t12 | 0.078±0.009 | 0.077±0.007 | 0.086±0.010 | 0.069±0.009 | 0.097±0.031 | 0.070±0.004 | 0.158±0.083 | 0.112±0.015 | 0.125±0.032 | 0.085±0.045 | 0.068±0.002 |

| C18:2 c9t12 | 0.474±0.252 | 0.329±0.131 | 0.670±0.539 | 0.171±0.105 | 0.509±0.120 | 0.129±0.084 | 0.285±0.106 | 0.199±0.061 | 0.222±0.095 | 0.060±0.045 | 0.380±0.063 |

| C18:2 t9c12 | 0.258±0.089 | 0.246±0.102 | 0.482±0.421 | 0.135±0.093 | 0.373±0.086 | 0.082±0.019 | 0.092±0.015 | 0.151±0.055 | 0.206±0.155 | 0.110±0.085 | 0.357±0.107 |

| C19:1 t7 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| C19:1 t10 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| C18:3 t9t12t15 | 0.083±0.008 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| C18:3 t9t12c15 + C18:3 t9c12t15 |

0.115±0.012 | 0.180±0.025 | 0.125±0.019 | 0.081±0.045 | 0.125±0.014 | 0.116±0.027 | 0.108±0.019 | 0.097±0.007 | 0.106±0.011 | 0.022±0.042 | 0.110±0.009 |

| C18:3 c9c12t15 | 0.613±0.191 | 0.057±0.096 | 0.171±0.244 | 0.019±0.024 | 0.035±0.028 | 0.029±0.015 | 0.096±0.074 | 0.029±0.018 | 0.054±0.028 | 0.016±0.010 | 0.055±0.025 |

| C18:3 c9t12t15 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.025±0.037 | ND | ND | ND |

| C18:3 c9t12c15 | 0.094±0.031 | 0.025±0.009 | 0.045±0.020 | ND | ND | ND | 0.018±0.016 | 0.003±0.005 | ND | ND | ND |

| C18:3 t9c12c15 | 0.466±0.162 | 0.024±0.011 | 0.123±0.211 | 0.003±0.007 | 0.063±0.152 | 0.013±0.038 | 0.068±0.058 | 0.006±0.011 | 0.031±0.026 | 0.005±0.010 | 0.053±0.016 |

| C20:1 t11 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.024±0.023 | 0.049±0.056 | ND | 0.020±0.030 | 0.007±0.021 | ND |

| C18:2 c9t11 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.234±0.124 | 0.690±0.278 | 0.668±0.322 | 0.767±0.613 | 0.382±0.276 | ND |

| C18:2 t10c12 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.164±0.023 | ND | 0.016±0.050 | 0.024±0.069 | ND |

| C22:1 t13 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.017±0.012 | 0.002±0.002 | 0.001±0.002 | 0.002±0.003 | 0.001±0.002 | 0.001±0.001 |

| ∑TMUFA | 0.048±0.029 | 0.079±0.034 | 0.045±0.018 | 0.049±0.029 | 0.185±0.056 | 0.172±0.036 | 3.106±1.155 | 2.250±0.747 | 1.506±0.746 | 0.214±0.123 | 0.147±0.043 |

| ∑ C18:2 TFA | 0.811±0.327 | 0.651±0.231 | 1.238±0.954 | 0.376±0.103 | 0.979±0.191 | 0.515±0.160 | 1.388±0.349 | 1.130±0.363 | 1.337±0.651 | 0.660±0.417 | 0.804±0.154 |

| ∑ C18:3 TFA | 1.371±0.334 | 0.286±0.107 | 0.464±0.484 | 0.103±0.033 | 0.222±0.146 | 0.162±0.054 | 0.290±0.146 | 0.160±0.054 | 0.191±0.055 | 0.044±0.052 | 0.218±0.039 |

| ∑ TFA | 2.216±0.595 | 1.016±0.319 | 1.748±1.169 | 0.528±0.103 | 1.386±0.257 | 0.849±0.195 | 4.784±1.282 | 3.540±0.863 | 3.034±1.216 | 0.917±0.537 | 1.169±0.208 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).