1. Introduction

Candida yeasts constitute a heterogeneous group of microorganisms capable of colonizing various ecological niches. Due to their clinical importance, research has primarily focused on pathogenic species, with

C. albicans considered the most important representative [

1]. In addition to

C. albicans, several non-

albicans Candida species (NAC), such as

C. glabrata,

C. tropicalis,

C. parapsilosis,

C. krusei,

C. guilliermondii,

C. lusitaniae,

C. kefyr,

C. famata,

C. inconspicua,

C. rugosa,

C. dubliniensis,

C. norvegensis,

C. utilis,

C. lipolytica, and the emerging global public health threat

C. auris, have been increasingly recognized as etiological agents of candidiasis [

1,

2,

3].

It is noteworthy that

Candida species are predominantly considered opportunistic pathogens, with the majority of infections having an endogenous origin. The pathogenesis of candidiasis is closely related to a number of

Candida virulence factors, including secretion of hydrolytic enzymes, expression of adhesins and invasins on the cell wall surface, pleomorphism, phenotypic switching, and biofilm formation [

2]. Furthermore, metabolic plasticity, efficient nutrient acquisition, and a remarkable ability to adapt to environmental stressors contribute significantly to their pathogenic potential.

Many

Candida species, including

C. kefyr,

C. boidinii,

C. lipolytica,

C. shehatae,

C. pseudotropicalis,

C. famata,

C. guilliermondii, and

C. inconspicua, are recognized as part of natural food microbiota, are used in food production, or have been isolated from food products such as milk and dairy products, alcoholic beverages, fruits, fruit juices, or traditional fermented foods [

4,

5]. The number of yeasts in these products can reach levels as high as 10⁶–10⁸ CFU/ml or CFU/g [

6]. In general, yeasts isolated from food that are not part of its native microbiota are considered food spoilage microorganisms.

Although foodborne gastrointestinal infections or intoxications caused by yeast are rare, sporadic cases of yeast-induced gastroenteritis have been reported [

6].

Candida spp. are capable of colonizing human gastrointestinal tract, contributing to the development of diarrhea and other gastrointestinal symptoms in at-risk individuals. In such cases, fecal samples may contain yeast counts exceeding 10⁶ CFU/g [

7]. Talwar et al. [

8] identified

C. albicans as the primary etiologic agent of gastroenteritis, although other species, including

C. tropicalis,

C. kefyr,

C. krusei,

C. parapsilosis,

C. lusitaniae, and

C. guilliermondii, have also been implicated. In addition, yeasts present in ingested foods may exacerbate Crohn’s disease and induce intestinal inflammatory responses [

9].

We have previously shown that food-borne NAC strains may exhibit relevant similarity to clinical

C. albicans, classifying them within the group of risk of potential pathogens [

10]. However, the preliminary and key criterion remains their ability to grow at human body temperature. Nonetheless, the implications of

Candida yeasts originating from food for human health are still poorly recognized, as they are generally considered to be saprophytic environmental strains.

Currently,

Candida spp. infections represent a significant public health problem, with cases of invasive candidiasis resulting in a high mortality rate of over 46% in patients with severe underlying diseases [

11]. Identification and typing of yeasts is crucial in the diagnosis of

Candida infections. It also enables the identification of the source of infection and facilitates tracking the development of antifungal drug resistance in epidemiological studies. However, despite the numerous yeast typing methods, such as morphotyping, serotyping, biotyping, and genotyping [

1], the question arises whether a method with sufficient discriminatory power is available that is of particular importance in clinical and epidemiological contexts.

The aim of the study was to assess the usefulness of various typing methods in the identification and differentiation of yeasts isolated from different environments (clinical and food-borne strains). It should be assumed that, due to their origin, these strains are likely to differ in virulence and the resulting risk to human health. To our best knowledge, most studies to date have focused either on clinical or environmental strains and have not covered such a diverse group of yeasts.

3. Results

In this study, 42 Candida strains were typed using biotyping based on yeast assimilation capabilities (API tests) and four genotyping methods, i.e., ITS1 and ITS4 sequence analysis, size polymorphism of the ITS1 and ITS4 regions, multiplex PCR of ITS1, ITS3, and ITS4 regions, and karyotyping. Moreover, biotyping and ITS sequence-based genotyping were used for the identification of the tested strains.

3.1. Biotyping and Yeasts Identification by API System

As a result of biotyping, 30 various assimilation profiles were obtained, with 4 profiles shared by more than one strain. The first group of yeasts with identical biochemical profiles included five clinical strains cl/MP/04, cl/MP/07, cl/MP/12, cl/MP/2K, and cl/OZ/g2 (

Table 2). The next group consisted of six clinical isolates cl/MP/02, cl/MP/05, cl/MP/09, cl/MP/4K, cl/MP/3M, and cl/MP/4M. Strains from both of these groups were identified as

C. albicans. Another assimilation profile was obtained for three food-derived strains fo/BM/02, fo/MP/02, and LOCK 0009, which were classified as

C. krusei (

Table 2). The last cluster consisted of two food-borne collection strains LOCK 0004 and LOCK 0006, identified as

C. lusitaniae (current name

Clavispora lusitaniae). The other 26 strains were characterized by unique assimilation profiles. Despite differences in the API profiles, 21 clinical isolates were identified as

C. albicans. The classification of the collection strain ATCC 10231 as belonging to this species was also confirmed. Only two clinical isolates were classified as non-

albicans Candida species, namely cl/KL/01 as

C. glabrata and cl/KL/02 as

C. lusitaniae (

Table 2). Greater species diversity was obtained among food-derived strains. In this group, a total of nine yeast species were identified, i.e.,

C. lusitaniae (4 isolates),

C. krusei (4),

C. boidinii (3),

C. famata (2),

C. parapsilosis (1),

C. colliculosa (1),

C. tropicalis (1),

C. rugosa (1), and

C. pelliculosa (1).

The discrimination index for yeast biotyping based on their assimilation capabilities by means of the API system was equal to 0.966.

3.2. Genotyping and Yeasts Identification Based on ITS Region Sequences

Partially different results of yeast identification were obtained based on the sequences of the ITS1 and ITS4 regions (

Table 2). Reclassification concerned 14 out of 24 clinical isolates and 14 out of 18 food-borne yeasts, representing slightly over 58% and almost 78% of the strains tested, respectively.

Among the clinical strains, three

Candida species were identified. The most frequently represented species was

C. lusitaniae (10 isolates), followed by

C. albicans (9), and

C. boidinii (5). Among the strains isolated from food, four species belonging to the genus

Candida were identified (

C. albicans,

C. lusitaniae,

C. boidinii,

C. tropicalis), along with four species not classified within the genus

Candida (

Pichia membranifaciens,

Pichia fermentans,

Wickerhamomyces anomalus, and

Meyerozyma guilliermondii). It is worth emphasizing that strain fo/79/01 isolated from fruit yogurt and fo/BM/01 originating from pickled cucumber were classified as

C. albicans (

Table 2).

Differentiation of yeasts based on the ITS region sequence was characterized by high discriminatory power, as no identical sequences were obtained in the group of the tested strains. The discrimination index for this method reached the highest possible value, amounting to 1.000.

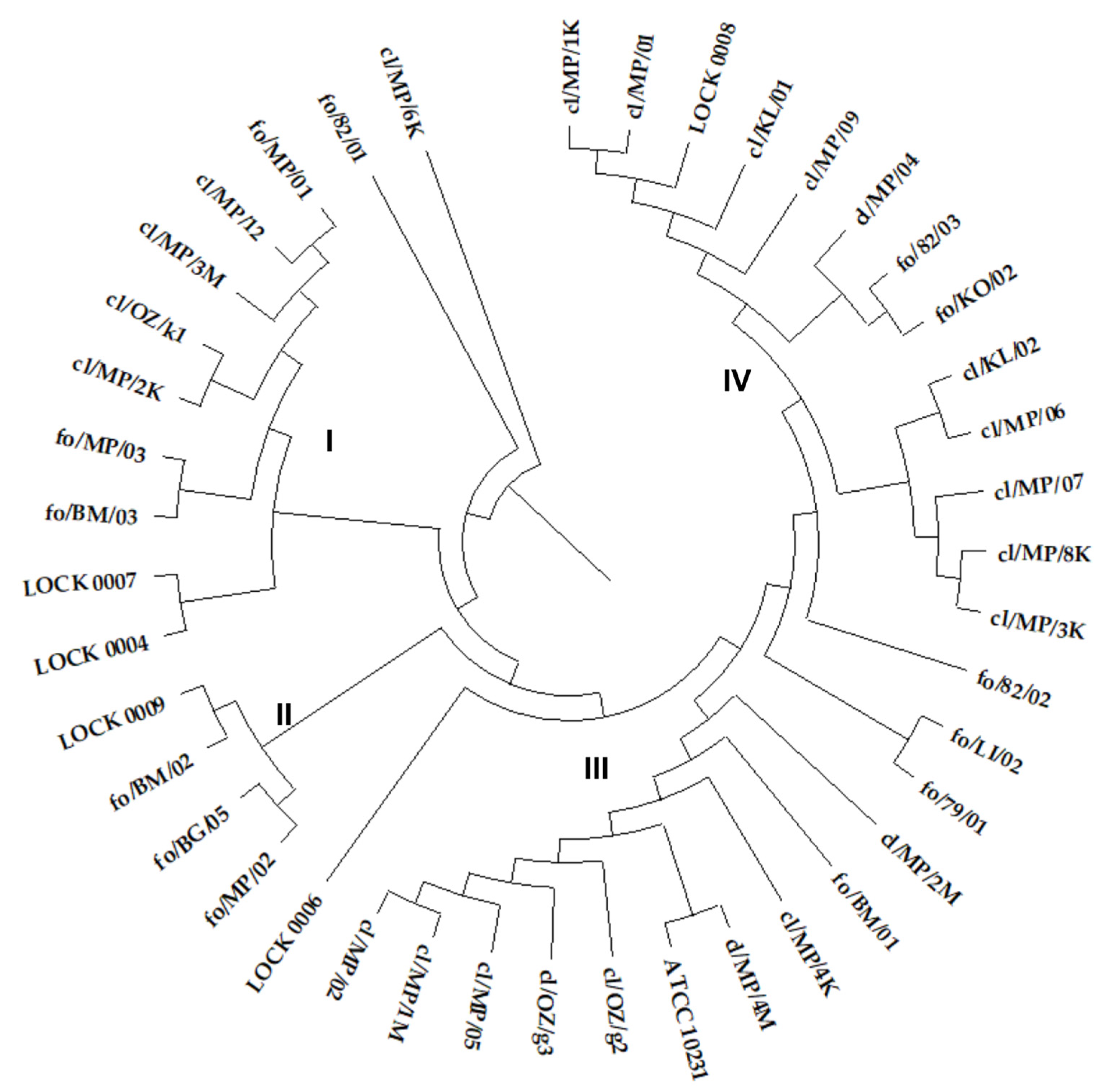

The ITS sequence similarity dendrogram grouped the yeasts into four larger clusters (

Figure 1). Cluster I consisted of seven

C. boidinii strains, including all three food-derived isolates and four out of five clinical strains classified as this species (cl/MP/12, cl/MP/3M, cl/OZ/k1, cl/MP/2K), along with single representatives of

M. gulliermondii (LOCK 0007) and

W. anomalus (LOCK 0004). Cluster II included two

P. membranifaciens (fo/MP/02, fo/BG/05) and two

P. fermentans isolates (fo/BM/02, LOCK 0009), all originating from food. The next group consisted of ten

C. albicans strains, including all clinical strains of this species, and one out of two food-derived

C. albicans isolates (fo/BM/01). The second food-borne

C. albicans strain fo/79/01 showed higher similarity to

C. lusitaniae fo/LI/02 (

Figure 1). Cluster IV contained thirteen strains of

C. lusitaniae, including all nine clinical isolates of this species and three out of six isolated from food (fo/82/03, fo/KO/02, LOCK 0008).

C. lusitaniae strain fo/82/01 showed lower similarity to other isolates of this species. On the other hand, the lowest similarity of the ITS region sequence in the tested group of yeasts was exhibited by

C. boidinii cl/MP/6K (

Figure 1). The common grouping of yeasts classified into the same species was expected. However, it is worth noting the high similarity of clinical and food-borne strains and their frequent common grouping in the same cluster.

Since it seems that more reliable results are obtained using the ITS region sequencing method, the species identification of the tested strains obtained by means of this method was further used.

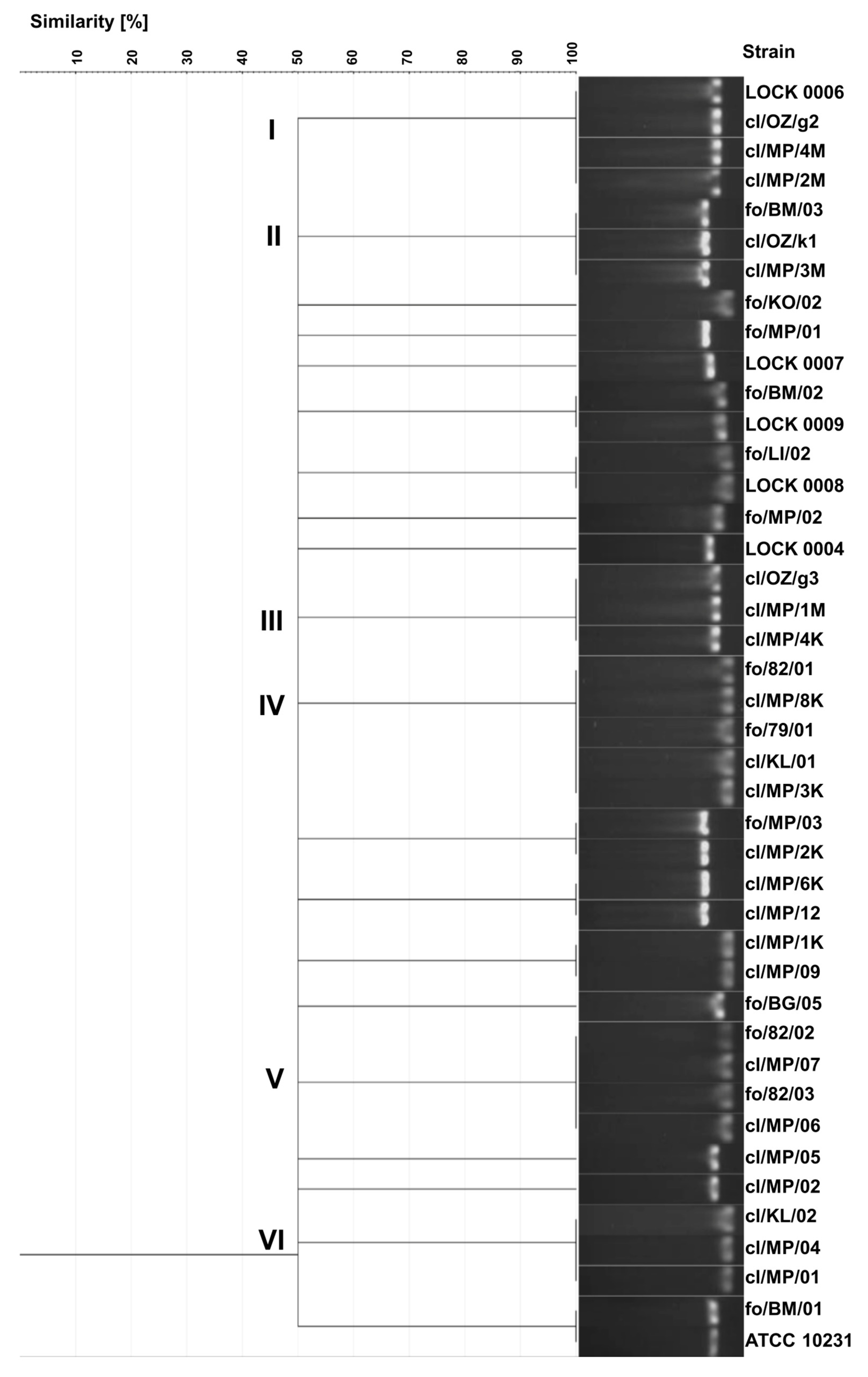

3.3. Yeasts Genotyping Based on ITS Region Polymorphism

As a result of electrophoretic separation of PCR products of the ITS region, 20 different electrophoretic profiles were obtained. Identical band sizes were observed in several groups of strains (

Figure 2). Identical profiles exhibited three clinical

C. albicans strains (cl/OZ/g2, cl/MP/4M, cl/MP/2M) and food-derived

C. tropicalis LOCK 0006, all showing the band size of 457 bp (cluster I). Cluster II included three

C. boidinii isolates, i.e., two clinical isolates (cl/OZ/k1, cl/MP/3M) and food-borne strain fo/BM/03, characterized by a band of 526 bp. A different electrophoretic profile with a band size of 463 bp was obtained for three clinical

C. albicans strains in cluster III (cl/OZ/g3, cl/MP/1M, cl/MP/4K). Cluster IV included three clinical

C. lusitaniae isolates (cl/MP/8K, cl/KL/01, cl/MP/3K), food-derived

C. albicans fo/79/01, and food-borne

C. lusitaniae fo/82/01, all of which exhibited a band size of 369 bp. The next cluster consisted of four

C. lusitaniae strains, including two food-borne strains (fo/82/02, fo/82/03) and two clinical isolates (cl/MP/07, cl/MP/06), with an electrophoretic profile characterized by a 384 bp band. Another profile, with a single band of 377 bp, was observed for three clinical

C. lusitaniae isolates in cluster VI (cl/KL/02, cl/MP/04, cl/MP/01).

In addition, identical electrophoretic profiles were obtained for the following pairs of strains:

P. fermentans fo/BM/02 and LOCK 0009,

C. lusitaniae fo/LI/02 and LOCK 0008,

C. boidinii fo/MP/03 and cl/MP/2K,

C. boidinii cl/MP/6K and cl/MP/12,

C. lusitaniae cl/MP/1K and cl/MP/09,

C. albicans fo/BM/01 and ATCC 10231. Only eight strains (

C. lusitaniae fo/KO/02,

C. boidinii fo/MP/01,

W. anomalus LOCK 0007,

P. membranifaciens fo/MP/02 and fo/BG/05,

M. guilliermondii LOCK 0004,

C. albicans cl/MP/05 and cl/MP/02) exhibited unique electrophoretic profiles of ITS region PCR products (

Figure 2).

Overall, 20 different electrophoretic profiles were obtained with this method, and yeasts of the same species were generally grouped together. However, four electrophoretic profiles were identical for yeasts belonging to different species. Furthermore, both clinical and food-derived strains were frequently grouped together in the same cluster. The discrimination index of the yeast genotyping method based on the ITS region polymorphism, relying on electrophoretic separation of the PCR product, was the lowest of all methods used and amounted to 0.957.

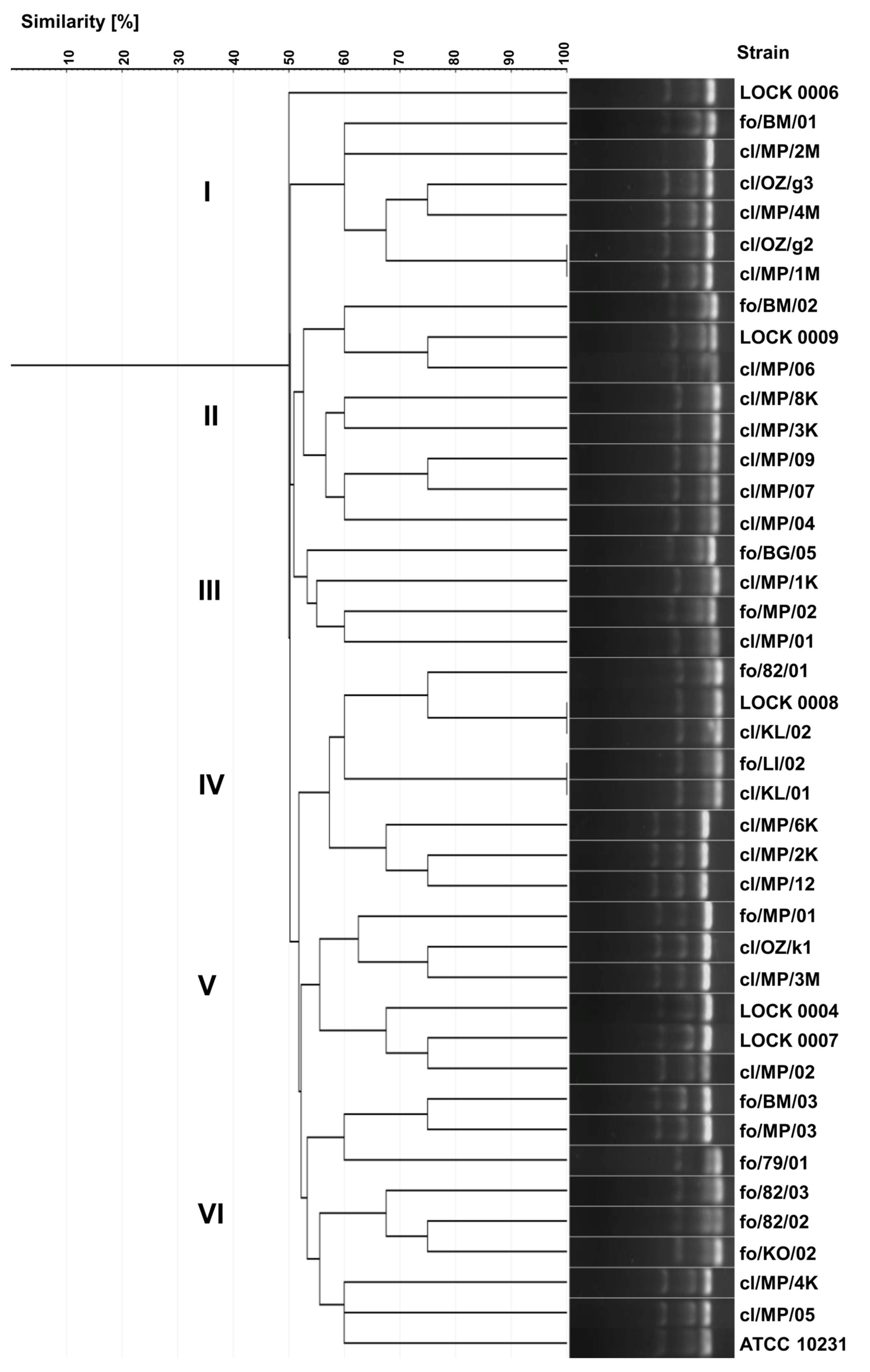

3.4. Genotyping Based on Multiplex PCR

As a result of the multiplex PCR analysis, 39 different electrophoretic profiles were obtained, demonstrating greater diversity than that observed in the ITS region polymorphisms analysis. The higher discriminatory power of this method resulted from the larger number of bands generated in the multiplex PCR, in contrast to a single band in the ITS region-based genotyping.

Identical electrophoretic profiles were noted for only three pairs of strains, namely

C. albicans cl/OZ/g2 and cl/MP/1M,

C. lusitaniae LOCK 0008 and cl/KL/02,

C. lusitaniae fo/LI/02 and cl/KL/01 (

Figure 3). Yeast strains were grouped into five internally diversified clusters, within which the similarity of electrophoretic profiles ranged from 50 to 100%. Cluster I included six strains belonging exclusively to one species,

C. albicans, including five clinical isolates (cl/MP/1M, cl/OZ/g2/, cl/MP/4M, cl/OZ/g3, cl/MP/2M) and food-borne fo/BM/01. Cluster II consisted of six clinical

C. lusitaniae isolates (cl/MP/04, cl/MP/07, cl/MP/09, cl/MP/3K, cl/MP/8K, cl/MP/06) and two food-derived

P. fermentans strains (LOCK 0009, fo/BM/02). Cluster III comprised both strains of

P. membranifaciens originating from food (fo/BG/05 and fo/MP/02), as well as two clinical isolates of

C. lusitaniae (cl/MP/1K and cl/MP/01). Cluster IV grouped together three clinical

C. boidinii isolates (cl/MP/12, cl/MP/2K, cl/MP/6K) and five

C. lusitaniae, i.e., two clinical (cl/KL/01, cl/KL/02) and three originating from food (fo/LI/02, LOCK 0008, fo/82/01). Cluster V was the most diverse and contained three

C. boidinii strains of various origins (cl/MP/3M, cl/OZ/k1, fo/MP/01), clinical

C. albicans cl/MP/02, as well as food-derived

W. anomalus LOCK 0007 and

M. guilliermondii LOCK 0004. Cluster VI was dominated by food-derived yeasts, namely

C. lusitaniae fo/KO/02, fo/82/02, fo/82/03,

C. albicans fo/79/01, as well as

C. boidinii fo/BM/03 and fo/MP/03. This group also included two clinical isolates of

C. albicans (cl/MP/05, cl/MP/4K) and the collection strain ATCC 10231 (

Figure 3).

In multiplex PCR-based genotyping, as previously observed, both clinical and food-borne strains were grouped into the same clusters. Strains representing different species were also grouped together. However, identical electrophoretic profiles were obtained only for yeasts classified to the same species. The discrimination index of the yeast genotyping method based on electrophoretic separation of multiplex PCR products was 0.997, and it was higher than the indices of both biotyping and ITS region-based genotyping.

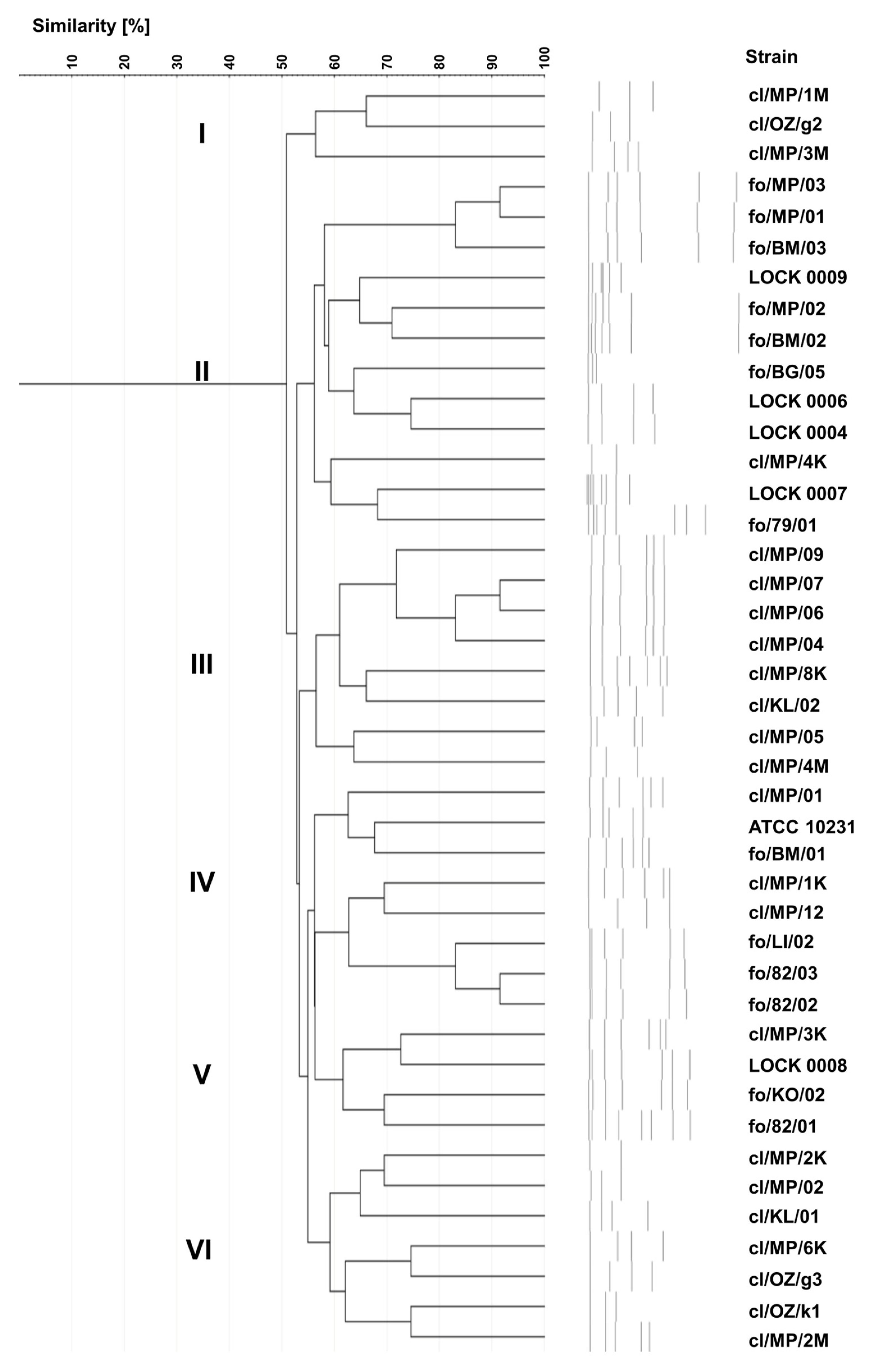

3.5. Yeasts Karyotyping

Karyotyping revealed 42 different electrophoretic profiles of yeast chromosomal DNA (

Figure 4), indicating that each of the strains tested exhibited a unique karyotype. The highest similarity at a level of slightly over 90% was found for three pairs of yeasts, i.e., two food-derived

C. boidinii strains (fo/MP/03 and fo/MP/01), two clinical

C. lusitaniae isolates (cl/MP/07 and cl/MP/06) and two

C. lusitaniae strains originating from food (fo/82/03 and fo/82/02).

On the dendrogram, 75% of clinical strains were grouped into three clusters - cluster I, III and VI - composed only of clinical isolates. However, in terms of species composition, all three clusters were internally diverse. Cluster I comprised two

C. albicans isolates (cl/MP/1M, cl/OZ/g2) and

C. boidinii cl/MP/3M. Cluster III included six out of ten

C. lusitaniae strains (cl/MP/09, cl/MP/07, cl/MP/06, cl/MP/04, cl/MP/8K, cl/KL/02) along with two

C. albicans isolates (cl/MP/05, cl/MP/4M). Cluster VI encompassed three

C. boidinii strains (cl/MP/2K, cl/MP/6K, cl/OZ/k1), three

C. albicans isolates (cl/MP/02, cl/OZ/g3, cl/MP/2M) and

C. lusitaniae cl/KL/01 (

Figure 4). In cluster II, apart from

C. albicans cl/MP/4K, food-derived strains were grouped, namely

C. albicans fo/79/01, as well as all food-borne strains identified as

C. boidinii (fo/BM/03, fo/MP/01, fo/MP/03),

P. fermentans (fo/BM/02, LOCK 0009),

P. membranifaciens (fo/BG/05, fo/MP/02),

C. tropicalis (LOCK 0006),

M. gulliermondii (LOCK 0004), and

W. anomalus (LOCK 0007). Cluster IV was the most diverse, containing both clinical and food-borne strains of

C. lusitaniae (cl/MP/01, cl/MP/1K, fo/LI/02, fo/82/03, fo/82/02),

C. albicans (fo/BM/01, ATCC 10231), and

C. boidinii cl/MP/12. In contrast, cluster V included only

C. lusitaniae strains, but differing in origin, i.e., three food-derived yeasts (LOCK 0008, fo/KO/02, fo/82/01) and one clinical isolate cl/MP/3K.

Karyotyping, similarly to genotyping based on ITS sequences, proved to be a highly effective method for typing yeast, with the discrimination index of 1.000. Among the applied methods, karyotyping appeared to allow the most structured and coherent grouping of yeasts according to their origin.

4. Discussion

The evaluation of the effectiveness of yeasts typing methods is typically based on several parameters, i.e., typeability, reproducibility, and discriminatory power [

17]. Among these characteristics, in this study we focused on the discriminatory power of typing methods, that is defined as the ability to distinguish between unrelated strains [

17]. From both clinical and epidemiological points of view, but also from a cognitive aspect, differentiation of

Candida spp. strains in terms of their origin is crucial, particularly in relation to sources of infection, yeasts pathogenic potential, colonization patterns, resistance to antimycotics, as well as strain microevolution within species [

11,

18,

19,

20].

To distinguish isolates of

Candida spp. from different sources, numerous molecular typing methods have been proposed, the most commonly used being duplex PCR, restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP), multilocus sequence typing (MLST), randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), and microsatellites [

1,

19,

20,

21,

22]. The utility of these methods has been well documented in previous publications, although literature data concern their application to determine genetic relatedness primarily among clinical

Candida strains. Furthermore, although these methods have been shown to have varying discriminatory power, it is difficult to compare them because the discrimination index is rarely reported. Available data indicate that the discrimination index for the microsatellites method may be 0.85–0.91 [

19], for DNA typing – 0.868 [

17], for RAPD fingerprinting – 0.984, and for karyotyping – only 0.630 [

23]. It is assumed that for typing results to be interpreted with confidence, the discrimination index should be greater than 0.90 [

17].

In this study, discrimination indices were determined for five selected typing methods, namely biotyping based on yeast assimilation profiles using the popular and commonly used API system, genotyping based on ITS region polymorphism and ITS sequencing, multiplex PCR of ITS regions, and karyotyping. The highest discriminatory capacity, enabling differentiation of all

Candida spp. strains tested, was achieved for karyotyping and ITS sequence analysis. The multiplex PCR method enabled differentiation of 99.7% of the tested strains, while biotyping allowed the distinction of 96.6% of the strains. ITS region-based genotyping proved to be the least discriminatory, with a discrimination index of 0.957. However, despite the differences in the index values, all tested typing methods fulfilled the criterion for results to be interpreted with confidence [

17]. It should be noted that the discrimination index value and the assessment of method utility strongly depend on the number and diversity of strains analyzed. On the other hand, although biotyping based on API 20C AUX tests showed high discriminatory power, as many as 66.7% of strains were identified differently compared to the ITS region sequencing method.

Yeast identification can also be performed based on their karyotypes. However, the use of this method for identification is challenging due to yeast chromosomal polymorphism, genomic instability, intraspecies variation, aneuploidy, and occurrence of co-migrating bands [

24]. This method, however, is recommended for strain-level differentiation [

24], which was confirmed by our results, as each isolate exhibited a distinct karyotype, despite many strains belonging to the same species.

According to ITS sequence-based identification, a significantly higher species diversity was observed among both food-derived and clinical yeasts compared to biotyping results. Among the clinical strains, in addition to

C. albicans and

C. lusitaniae, isolates belonging to

C. boidinii were also identified, with

C. lusitaniae being the predominant species. This finding is partly consistent with previous reports on NAC species associated with human infections [

1,

3,

25]. However,

C. boidinii is rarely mentioned in this context, although clinical strains of this species have been reported [

26]. Similarly, among food-borne yeasts, the identification of two strains as

C. albicans is surprising, as this species has not been previously associated with food sources. Other strains identified among food-derived yeasts, i.e.,

W. anomalus,

C. lusitaniae, and

C. krusei are also considered opportunistic pathogens that may cause infections, especially in people at risk [

3,

25,

27].

These findings are consistent with previous studies suggesting the inability to distinguish between clinical and environmental strains. In line with this, no genetic distinction was found between 20 clinical

C. krusei isolates and 12 environmental

P. kudriavzevii isolates, indicating that these yeasts belong to the same species [

28]. High genetic congruence was also observed for yeasts originating from different environments in various regions of Mumbai (soil adjacent to urinals, sewage water, beach water, hospital soil), and among the identified species,

C. albicans,

C. tropicalis, and

C. krusei were found in descending order of abundance [

20]. Moreover, environmental and food-borne strains may exhibit similar levels of drug resistance to clinically relevant isolates [

20,

28,

29]. Douglass et al. [

28] further hypothesize that, due to the close relationship between clinical and environmental isolates, infections may be acquired opportunistically from the environment.

These findings are consistent with the One Health concept, which assumes the potential transmission of microorganisms between animals, humans, and ecosystems but focuses in particular on emerging and endemic zoonoses [

30]. Antimicrobial resistance also remains a critical concern, as resistance can arise in humans, animals, or the environment and may spread between these reservoirs. The phenomenon of microorganism transmission between different environments appears to explain the high similarity of strains of diverse origins observed in this study, as well as the clustering of food-borne and clinical isolates within the same groups.

Summing up, in this study we have demonstrated the very high discriminatory power of genotyping based on the ITS region sequencing and karyotyping in differentiating Candida spp. strains of various origin. Moreover, identification based on ITS region sequences proved to be significantly more useful than identification based on yeast assimilation profiles. In light of the results presented here, the interpretation of the discrimination index remains an open question. The fact that in two out of five typing methods tested all strains differed suggested their distinct origin. Therefore, obtaining a discrimination index lower than 1.000 for the method applied in the study may indicate not the compatibility or identity of the strains, but the limitation of the method used in terms of their differentiation. In this context, it seems necessary to use in typing at least one method with a discrimination index of 1.000 to avoid errors in the interpretation of results regarding strains’ origin and similarity.