Submitted:

01 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (i)

- Every affine gauge of extends to an internal diffeomorphism of , so the pseudo-smooth surface inherits the full relativistic covariance of the finite algebra.

- (ii)

- Loeb-measure shadows [8] show that the combinatorial curvature of the lattice converges, up to infinitesimals, to the Gauss curvature of [9]. This tangible bridge between discrete and smooth geometry in characteristic p also paves the way for harmonic analysis [10,11], heat flow [12], and gauge theory [13] on finite relativistic geometries.

- (iii)

- The framed field contains three fundamental structural constants——canonically singled out by its cyclic order. These constants serve as finite-field analogs of the classical that underpin calculus on and .

2. Finite Fields and Arithmetic Symmetries

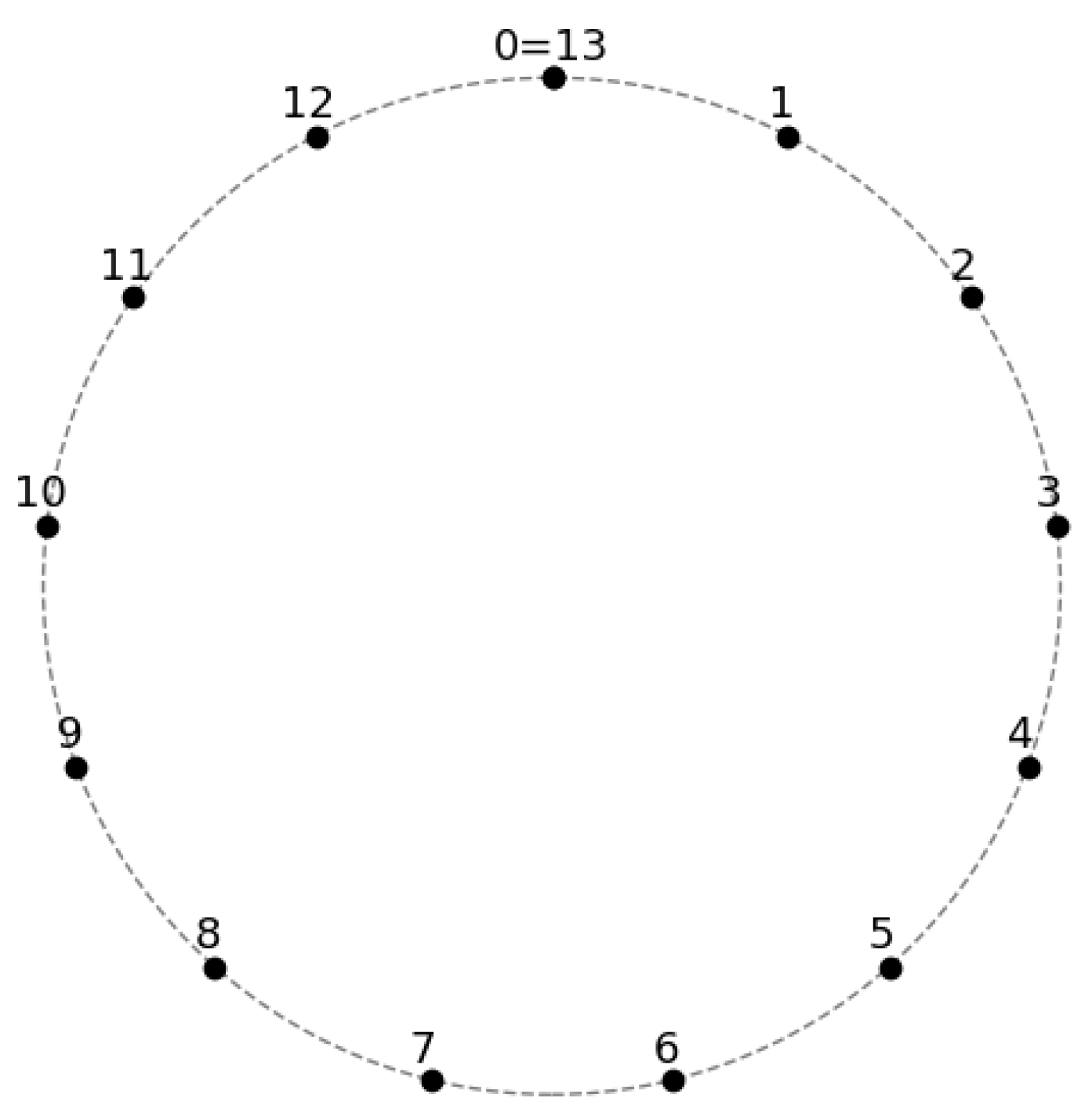

2.1. The Discrete 2-Spheroid Inside Symmetry Space

- Two-parameter generation. By the lemma any composition of reduces to ; hence is exactly the orbit of under the commuting group .

- Dimension. Each orbit point is obtained by at most two independent moves (T and S), so every cell in the induced cubical structure has dimension . Non-degeneracy of the actions ensures that two-dimensional faces do appear, making the complex pure of dimension 2.

- Local sphericality. At a vertex v adjacent vertices differ from v in exactly one of the two active coordinates. The four resulting neighbours form a 4-cycle, i.e. the link of v is a combinatorial 1-sphere.

- Global structure. A finite, pure 2-dimensional CW-complex with cyclic vertex links is necessarily a triangulation of a topological 2-sphere (Alexander duality or direct enumeration). Hence .

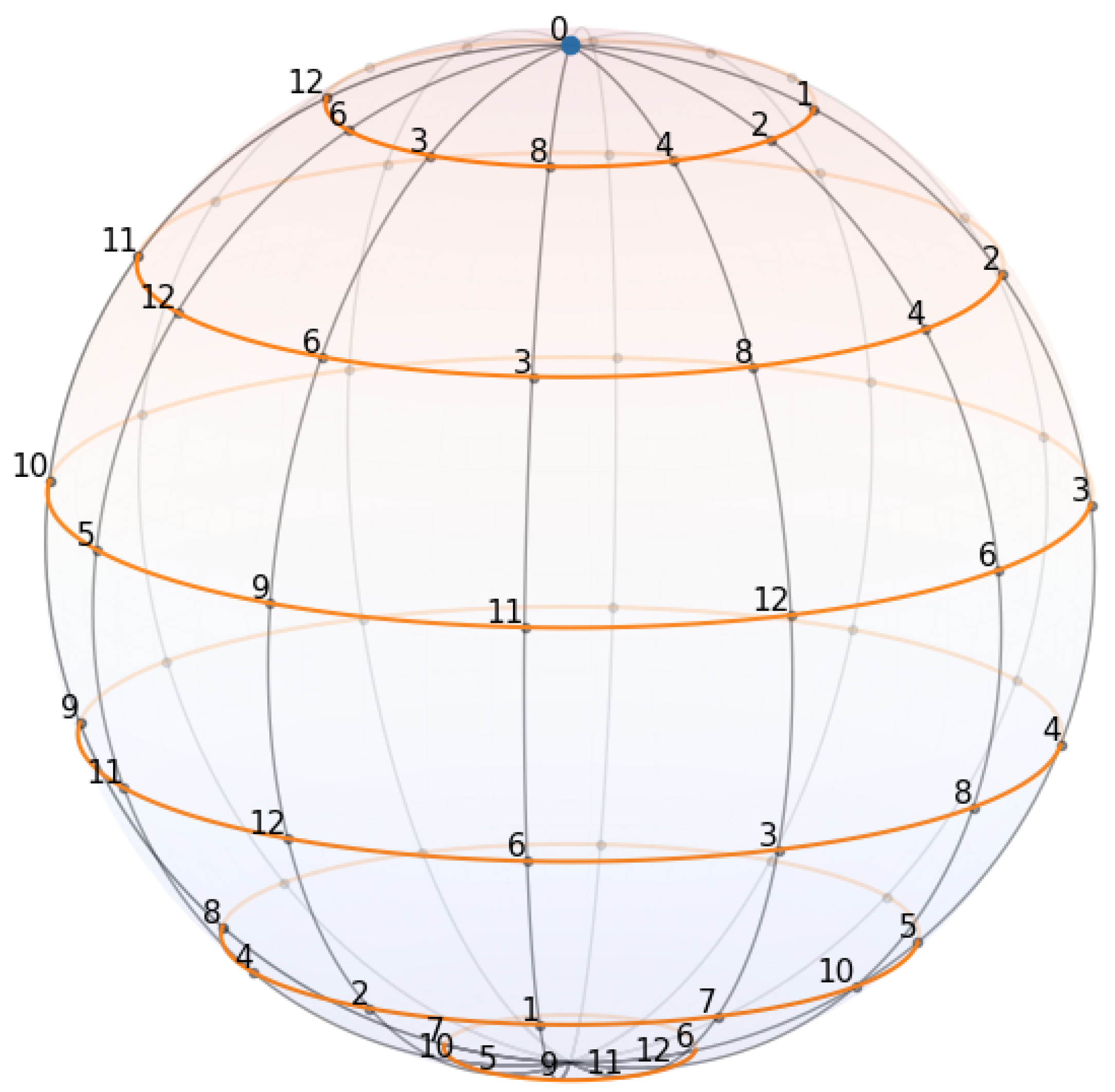

2.2. Pseudo-Smooth Lift

- 1.

- is an internal two-dimensional submanifold of .

- 2.

- is a finite 2-sphere CW-complex combinatorially identical to the discrete 2-spheroid of .

- 3.

- For every infinitesimal the lattice is an ε-net in ; equivalently, in the internal topology.

- 4.

- The internal Gaussian curvature of , computed by infinitesimal triangles, is identically 1. (Proof: transfer of the classical formula for σ.)

2.3. Intrinsic Curvature of the Pseudo-Smooth 2-Spheroid

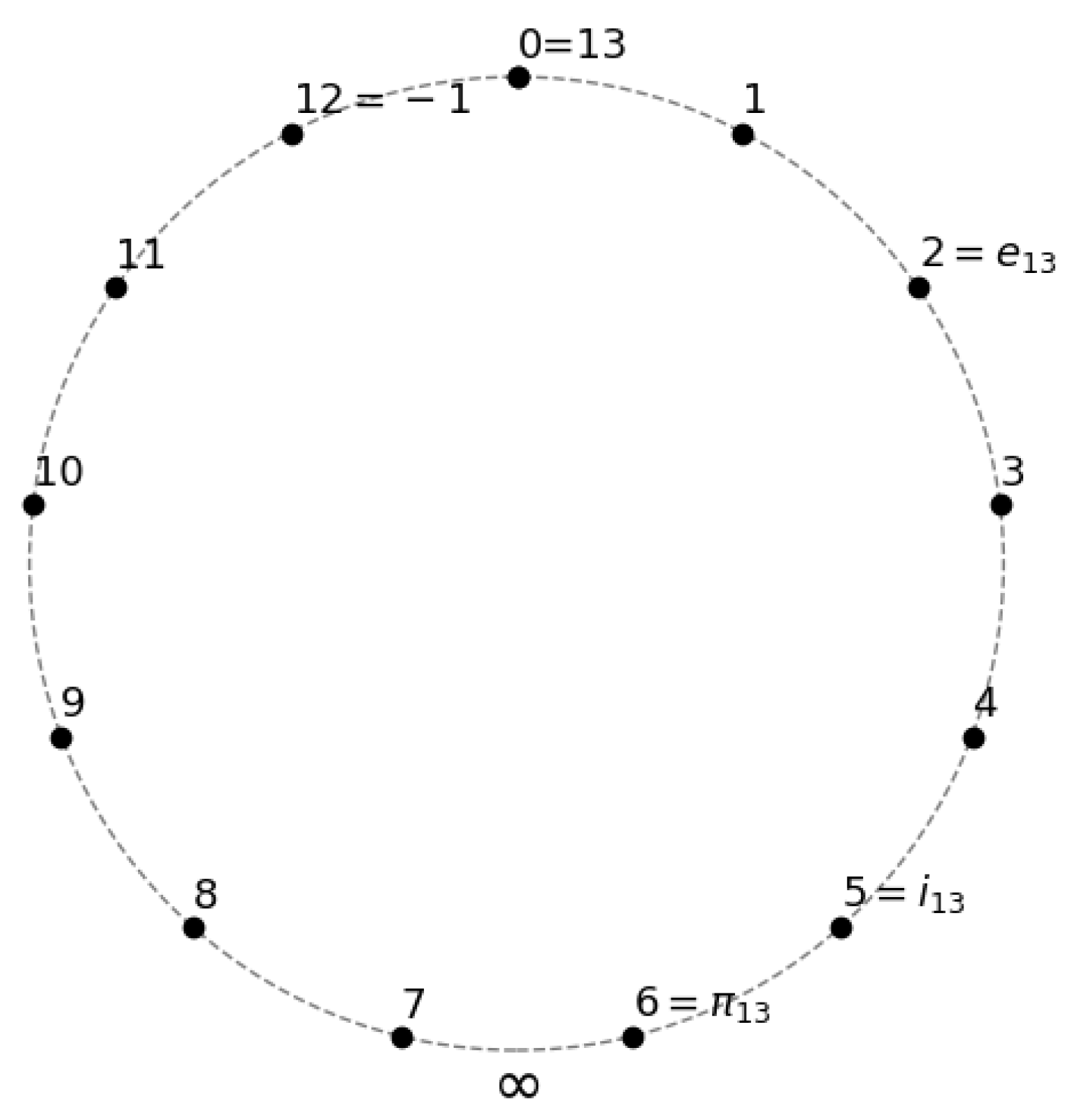

3. Canonical Constants in

3.1. The Quarter-Turn Generator

3.2. The Natural Exponential Base

- Cyclic distance. For define the additive-circle distance to the origin

- Forward-time convention. To avoid the duplicity of primitive roots we restrict attention to the forward half-circleEvery unordered pair of primitive roots contributes exactly one element to , so the selection below is unambiguous for all odd primes p.

- Discrete exponential and logarithm. Using as base defineBecause is minimal among primitive roots, realises the smallest forward difference at the origin, mirroring .

- Gauge covariance. Let be an affine gauge transformation with . Multiplication by a is an automorphism of the cyclic group , so it permutes primitive roots and preserves the order of their residues in . Translation by b fixes . Consequently the image of under the gauge is the minimiser of (3.1) in the new frame; hence is a frame-invariant constant of the theory.

3.3. The Finite-Field Half-Period

- Primitive root and half-turn. Fix an odd prime p and letbe the least positive primitive root in the framed order . Euler’s criterion gives the well-known identity

- Rotation-group interpretation. Define the additive circle Multiplication by acts on byand the map identifies the rotation group of with the cyclic group of units. Under this identificationis the half-turn (antipodal) map, so counts exactly half the lattice points around the discrete circle, mirroring the classical equation .

- Geometric role on the pseudo-smooth spheroid. Embed diagonally into the pseudo-real line and letbe the pseudo-smooth 2-spheroid of Theorem 2.3. Its prime meridian inherits the same rotation group as . Stepping times along the lattice therefore

- advances halfway around ;

- sends each lattice point to its meridian antipode; and

- realizes a geodesic length proportional to .

4. Harmonic Analysis in a Finite-Relativistic Setting

4.1. Additive Characters: Continuous and Finite

- Continuous. On the dual group is again ; the Fourier kernel is

- Finite. On the dual group is viaThe discrete Fourier transformsatisfies the finite Plancherel identity [20]

4.2. Primitive Roots as Infinitesimal Rotations

4.3. Kernel Correspondence

4.4. Consequences and Outlook

- Unified Plancherel. The standard-part map sends the pseudo-Plancherel identity in to the classical one on and its restriction to to the finite identity.

- Poisson summation. Formula (4.1) implies a Poisson summation law that simultaneously contains the discrete and continuous versions; the proof follows the usual character-orthogonality argument verbatim.

- Applications. A detailed exposition—covering pseudo-differential operators, Gauss sums, and finite-field wavelets—will appear in a separate paper. Here we record that the constants supply the entire character table needed for harmonic analysis in our finite-relativistic algebra.

5. Conclusions

- Discrete-to-smooth passage. Starting from the translation–scaling orbit of we constructed a regular CW complex that is combinatorially . Using the pseudo-real completion we lifted to an internal surface whose hyperfinite trace is -dense for every infinitesimal and whose Gaussian curvature satisfies

- Canonical constants. The cyclic order of picks out three frame-invariant elements— the quarter-turn , the half-period , and the minimal-deviation base . Together they reproduce inside the algebraic rôles played by in C and endow with a built-in complex-analytic flavor.

- Unified harmonic analysis. Embedding into and identifying with an infinitesimal rotation yields a single kernel that specializes both to the classical Fourier kernel on and to the discrete characters on . Hence Fourier, convolution, Plancherel and Poisson-summation identities coexist in one frame-relative formalism.

- Gauge covariance. Every affine relabelling of the framed field extends to a diffeomorphism of and permutes in a way that preserves their defining extremal properties; the geometry is therefore fully compatible with the relativistic-algebra principle introduced in the companion papers.

- Outlook. The techniques developed here scale naturally to higher-dimensional symmetry cubes and to composite moduli q, where the orbit complex becomes a three-manifold; Perelman’s theorem [21,22] and discrete Ricci flow [23,24] suggest a route to canonical round metrics in that setting. On the analytic side, the pseudo-smooth framework opens the way to characteristic-p versions of heat kernels [20], wavelets [25], and gauge fields [26], with potential applications to coding theory [27] and finite-precision models of quantum dynamics [28]. These directions are the subject of ongoing work.

- By exhibiting a differential, analytic, and symmetry-rich structure generated solely from finite arithmetic data, the present article supports the thesis that finite relativistic algebra can serve as a common foundation for discrete mathematics, classical analysis, and physical modelling within a single, gauge-covariant, finite universe.

References

- Akhtman, Y. Relativistic Algebra over Finite Fields. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidl, R.; Niederreiter, H. Finite Fields, 2nd ed.; Vol. 20, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Serre, J.P. A Course in Arithmetic; Springer-Verlag, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov, P.S. Combinatorial Topology; Dover Publications, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goldblatt, R. Lectures on the Hyperreals: An Introduction to Nonstandard Analysis; Springer: New York, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Author, A. Stereographic Projection and Applications; Publisher Name, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Keisler, H.J. Infinitesimal Calculus; Prindle, Weber & Schmidt, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Loeb, P.A. Conversion from Nonstandard to Standard Measure Spaces and Applications in Probability Theory. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 1975, 211, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Carmo, M.P. Differential Geometry of Surfaces; Prentice–Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1976; See Chap. 4 for Gauss curvature and the Theorema Egregium. [Google Scholar]

- Mockenhaupt, G.; Tao, T. Restriction and Kakeya phenomena for finite fields. Geometric and Functional Analysis 2005, 15, 1238–1287, Seminal paper illustrating Fourier-analytic techniques (restriction, Kakeya) over finite fields. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Vu, V. Additive Combinatorics; Vol. 105, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2006; Includes a self-contained exposition of finite-field Fourier analysis and its combinatorial applications. [Google Scholar]

- Grigor’yan, A. Heat Kernel and Analysis on Manifolds; Vol. 47, AMS/IP Studies in Advanced Mathematics; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, 2009; Comprehensive treatment of the heat equation, heat kernels, and their relation to geometry. [Google Scholar]

- Baez, J.C.; Muniain, J.P. Gauge Fields, Knots and Gravity; World Scientific: Singapore, 1994; Friendly introduction to gauge symmetry, covariant derivatives, and their geometric meaning. [Google Scholar]

- Dummit, D.S.; Foote, R.M. Abstract Algebra; John Wiley & Sons, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rotman, J.J. Introduction to the Theory of Groups, 4th ed.; Springer, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, D.M. Elementary Number Theory, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher, A. Algebraic Topology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2002; Freely available from the author’s webpage. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin, W. Fourier Analysis on Groups; Wiley, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, E.M.; Shakarchi, R. Fourier Analysis: An Introduction; Princeton University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Terras, A. Fourier Analysis on Finite Groups and Applications; Cambridge University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Perelman, G. The entropy formula for the Ricci flow and its geometric applications. arXiv preprint math/0211159 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Perelman, G. Ricci flow with surgery on three-manifolds. arXiv preprint math/0303109 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, B.; et al. The Ricci Flow: Techniques and Applications. Mathematical Surveys and Monographs 2004, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, R. Bochner’s method for cell complexes and combinatorial Ricci curvature. Discrete & Computational Geometry 2003, 29, 323–374. [Google Scholar]

- Kozyrev, S.V. Wavelet Theory as p-Adic Spectral Analysis. Izvestiya: Mathematics 2002, 66, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, J.C. Gauge Fields, Knots and Gravity; World Scientific, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- MacWilliams, F.J.; Sloane, N.J.A. The Theory of Error-Correcting Codes; North-Holland: Amsterdam, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Schwinger, J. Unitary Operator Bases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1960, 46, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | In non-standard analysis a set, function, or manifold is called internal if it lives entirely inside the ultrapower universe: it can be represented by an equivalence class of standard sequences and therefore inherits every first-order property of its classical counterpart via the Transfer Principle [5]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).