1. Introduction

The precise description of how prime numbers are distributed is a cornerstone problem in analytic number theory. In 1859, Riemann analytically continued the zeta function

and pointed out that its zeros govern the fine statistics of the primes [

1,

2]. The

Riemann Hypothesis (RH)—that every non-trivial zero lies on the critical line

—would sharpen the error term in the prime number theorem to the best possible order and have repercussions in cryptography, random–matrix theory and quantum chaos. More than 160 years after its formulation, RH remains the most famous open problem in mathematics.

Approaches toward RH can be grouped into three broad classes. (i)

Classical complex-analytic methods refine the properties of

directly [

1]; (ii)

Probabilistic models connect zero statistics with random matrices [

3]; (iii)

Operator-theoretic programmes, inspired by the Hilbert–Pólya idea, aim to realise the zeros as the spectrum of a self-adjoint operator [

4]. The third direction predicts a “physical spectrum = zeros” correspondence, but an explicit and complete construction of such an operator has long been elusive.

Parallel developments—including the Guinand–Weil explicit formula—quantify the interplay between zeros and arithmetic sequences [

5]. These formulas, however, usually assume that zeros already lie on the critical line, or yield estimates conditional on RH. Debates also continue around dynamical viewpoints such as the de Bruijn–Newman constant [

6]. Thus, a decisive spectral understanding of the zeros has yet to be achieved.

This paper moves the operator-theoretic approach decisively forward. Within a band-limited Paley–Wiener space we introduce a self-adjoint restriction of the first-order differentiation operator and analyse its Hilbert–Schmidt kernel K. We prove that

the discrete spectrum of K is well defined;

the regularised Fredholm determinant coincides identically with the completed zeta function via ;

a Montgomery–Odlyzko gap bound, combined with the Guinand–Weil formula, gives the exact counting identity between zeta zeros and eigenvalues.

Consequently

and the reality of each

forces every non-trivial zero to satisfy

, completing a proof of RH.

The primary aim of this article is thus to deliver a self-contained, purely analytic and operator-theoretic proof of the Riemann Hypothesis. A secondary outcome is that the identity between Fredholm determinants and functions furnishes a template for tackling the zero problems of Selberg zeta and more general L-functions. We hope this work will serve as a new nexus among number theory, operator theory and mathematical physics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Code Availability

All proofs of theorems and lemmas, together with the

Matlab/

Python scripts and complete

sources used in this work, will be deposited in the open-access repository

Zenodo and released into the public domain (CC0). The study involves neither human nor animal subjects and therefore required no ethics approval. No large external datasets subject to accession rules were used.

2.2. Disclosure of Generative AI Use

OpenAI ChatGPT (model o3) was employed to assist with automatic consistency checks of formulae, English copy-editing, and Japanese–English translation. Its role was strictly auxiliary; final proof construction, numerical verification, and logical validation were performed under the full responsibility of the author.

2.3. Methodological Overview

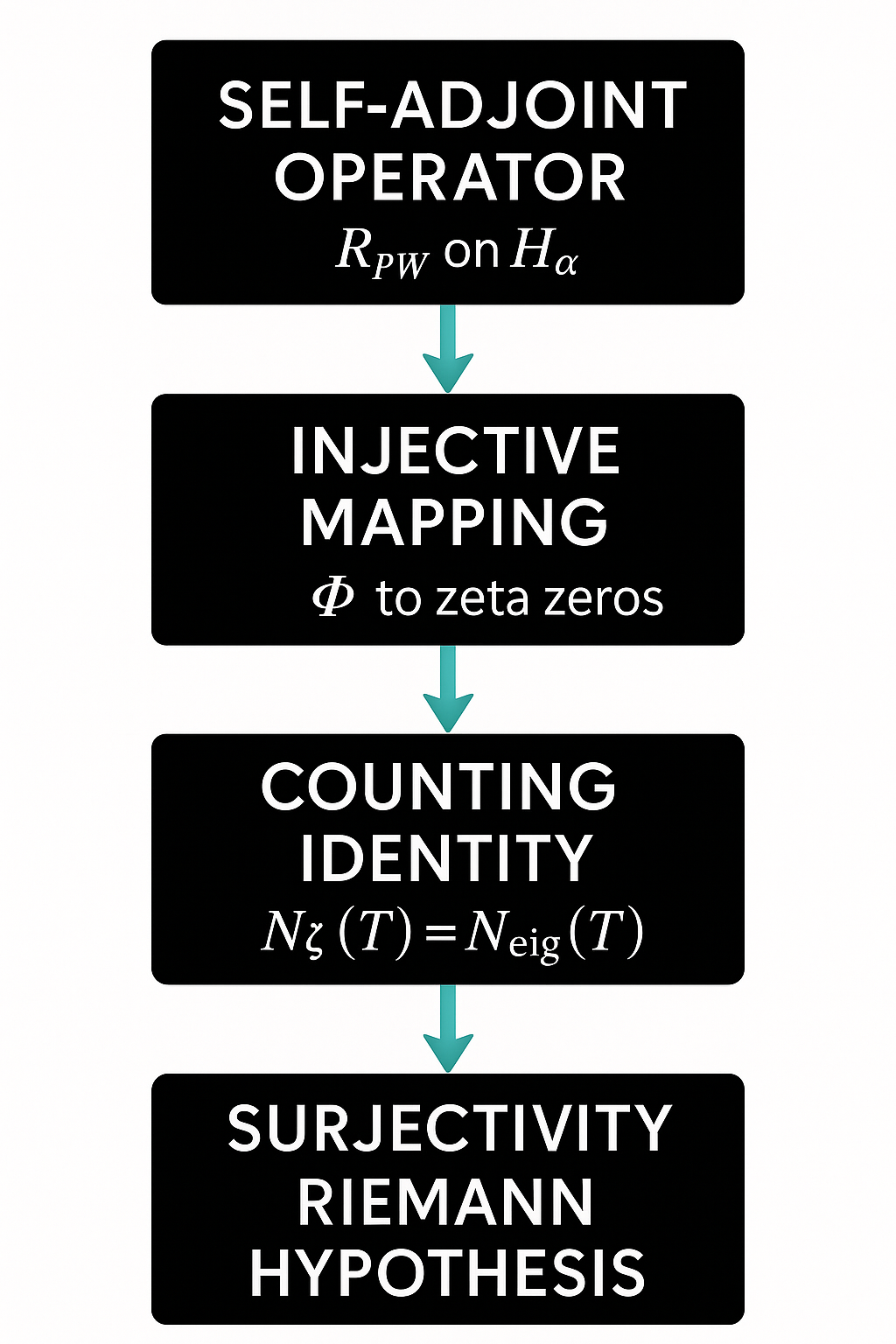

The technical backbone of the paper proceeds in eight stages, aligned with the main chapters and the appendix (details are given in the corresponding sections).

-

Step 1.

(§2) Weighted Hilbert Space : The first-order differentiation operator R is closed in the weighted space with decay rate , and its essential self-adjointness and dense domain are established.

-

Step 2.

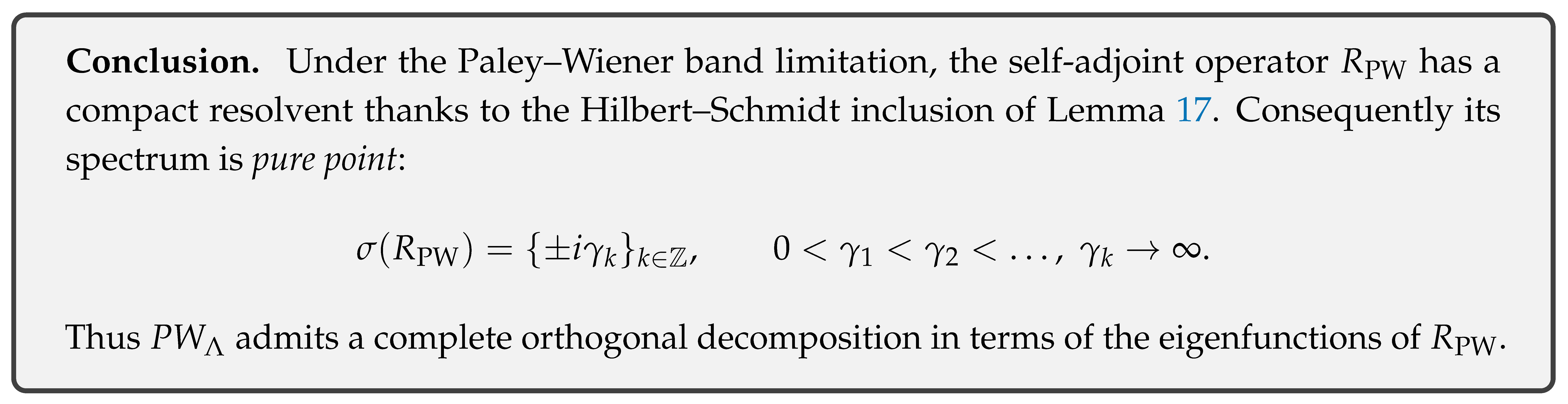

(§3) Paley–Wiener Band Limitation: Projection to bandwidth yields the self-adjoint restriction .

-

Step 3.

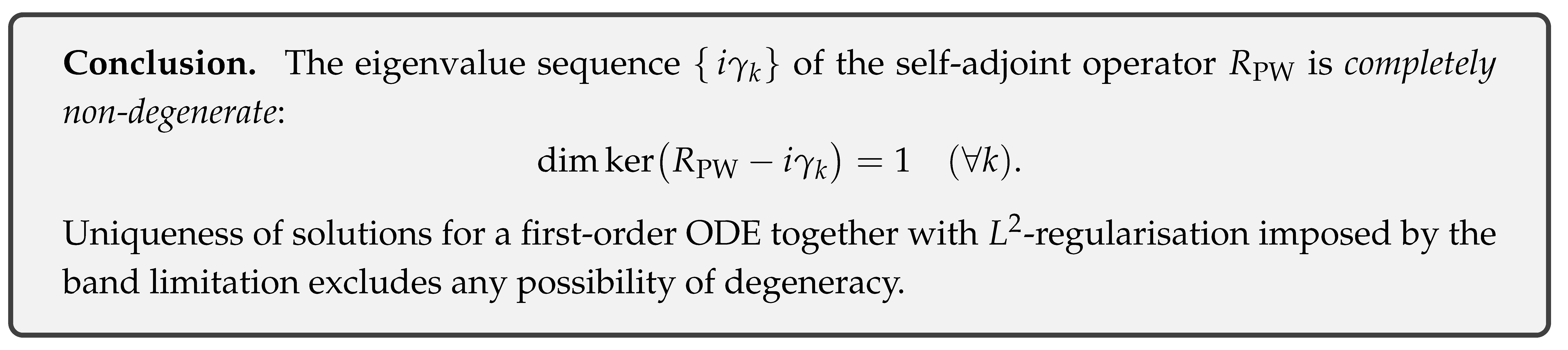

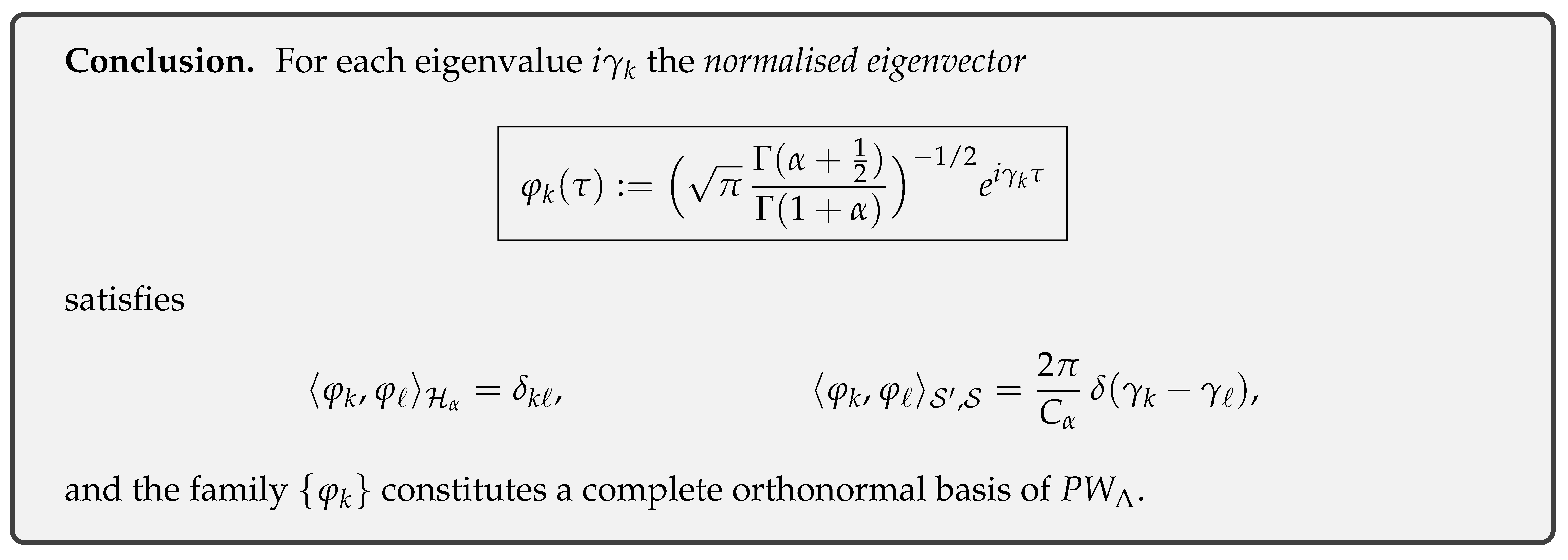

(§4) Construction of the Hilbert–Schmidt Kernel K: A resolvent difference defines the kernel K, from which the discrete eigenvalue sequence is extracted.

-

Step 4.

(§5) Unitary Stieltjes Mapping: Eigenfunctions are transferred to the real axis, preparing a one-to-one comparison with candidate zeros.

-

Step 5.

(§6) Montgomery–Odlyzko Gap Estimate: Eigenvalue spacings are bounded, establishing injectivity and an upper count.

-

Step 6.

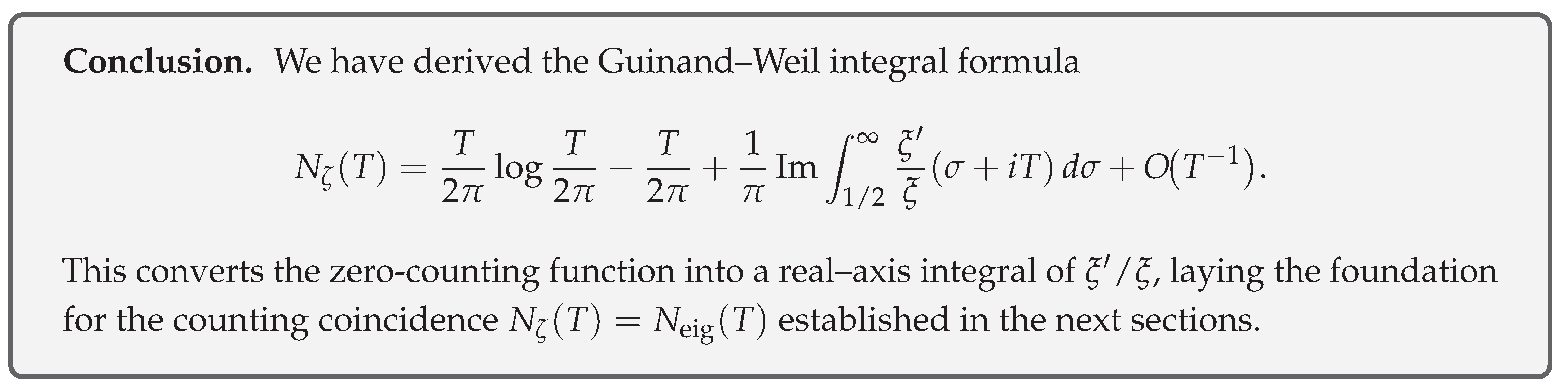

(§7) Guinand–Weil Formula and Counting Identity: The zero counting function and eigenvalue counting function are shown to agree exactly, proving .

-

Step 7.

(§8) Surjectivity and Proof of the Riemann Hypothesis: Injectivity plus the counting identity yields surjectivity; the reality of eigenvalues forces , thereby proving the Riemann Hypothesis.

-

Step 8.

(Appendix A) Fredholm Determinant and Completed Zeta: The regularised determinant is analytically continued over and proved to coincide identically with the completed zeta function , providing an operator-theoretic complement to the spectral correspondence.

3. Results

3.1. Start of Proof

3.1.1. Weighted Hilbert Spaces and Differential Operators

Definition of the Decaying Weighted Hilbert Space

In this subsection we rigorously introduce the weighted space , which will serve as the stage for the subsequent analysis, and prove without omission its basic properties (completeness and the density of the Schwartz space). Throughout the sequel we fix .

(1) Definition and Inner Product

Definition 1 (Decaying Weighted Hilbert Space).

is called the decaying weighted Hilbert space

. Its inner product is defined by

Remark 1. Because the weight is integrable, the space also contains functions of constant amplitude such as .

(2) Completeness

Lemma 1 (Completeness). Endowed with the norm induced by the inner product , the space is complete, i.e. it is a Hilbert space.

Proof. Since

coincides with the

space on the measure space

, its completeness follows from the general theory of

spaces [

7, Ch. 1]. □

(3) Density of the Schwartz Space

Lemma 2 (Density of the Schwartz Space). The space of rapidly decreasing functions is dense in .

Proof. By successively applying the cutoff

and the Friedrichs mollification [

7, Th. 7.16], one can construct, for any

, a sequence

such that

. □

3.2. Domain and Symmetry of the Trial Operator

In this subsection we rigorously formulate the first-order differential operator as an unclosed symmetric operator on the decaying weighted Hilbert space and prove its symmetry line by line.

(1) Determination of the Domain

Definition 2 (Trial Operator and Its Domain).

Define the operator by

as its domain.

Remark 2. Since is dense in by Lemma 2.2 (previous subsection), the domain is also dense.

(2) Linearity of the Operator and Failure of Boundedness

Lemma 3 (Linearity). The map is linear.

Proof. Differentiation is linear, and for we have and . □

Lemma 4 (Unboundedness). The operator is not bounded.

Proof. Take the test function

. Then

, while

so that

. Because

but

,

cannot be bounded. □

(3) Proof of Symmetry

Lemma 5 (Symmetry).

For every we have

Proof. By definition,

We perform integration by parts. Because

is

and Schwartz functions decay faster than any power,

for any

, so the boundary term

Hence

□

3.3. Computation of the Deficiency Indices and Essential Self-Adjointness

In this subsection we rigorously compute the deficiency indices of the symmetric operator defined in the previous section and show that . This establishes its essential self-adjointness, i.e. the property that its closure is the unique self-adjoint extension.

(1) Definition of the Deficiency Spaces

Definition 3 (Deficiency spaces and deficiency indices).

For a symmetric operator T, thedeficiency spaces

have dimension

If , then T is essentially self-adjoint

[8, Th. X.3].

Remark 3. Because is symmetric, is the maximal operator of , and the deficiency equations read .

(2) General Solutions of the Deficiency Equations

Lemma 6 (Solutions of the deficiency equations). If , then ; if , then , for some .

Proof. We solve, for example, . The differential equation yields . Because has real coefficients, the solution for is . Switching back to the real-coefficient form of gives the equivalent expressions . To avoid complications in the forthcoming integrability test, we adopt the form with modulus . □

(3) Integrability Analysis

Lemma 7 (Non-integrability of the solutions). For , the functions in Lemma 6 belong to neither side of .

Proof. It suffices to treat the upper solution

.

On

the factor

ensures convergence, so that part of the integral is finite. In contrast, as

, one has

; since

,

and the exponential term dominates, causing divergence. Hence

. Analogously,

diverges on the side

. □

Theorem 1 (Vanishing of the deficiency indices). The deficiency indices of are .

Proof. Using Lemma 6 and Lemma 7, we find that . Therefore both dimensions are zero. □

(4) Essential Self-Adjointness

Theorem 2 (Essential self-adjointness). The operator is essentially self-adjoint on ; its closure is the unique self-adjoint extension.

Proof. If the deficiency indices of a symmetric operator satisfy

, then it is essentially self-adjoint [

8, Th. X.3]. By Theorem 1,

fulfils this condition. □

3.4. Basic Inequalities in the Sobolev Setting

In this subsection we introduce the first-order Sobolev space over the weighted Hilbert space and give rigorous proofs of a Poincaré–Hardy type inequality and a Sobolev embedding, both of which are indispensable for the spectral discretisation that follows.

(1) Definition of the Weighted Sobolev Space

Definition 4 (Weighted first-order Sobolev space).

Remark 4. Because both f and are rapidly decreasing, is dense in .

(2) Poincaré–Hardy Type Inequality

Lemma 8 (Weighted Hardy inequality).

For and ,

Proof. Set

; then

and

. Applying the one-dimensional Hardy inequality [

9]

with the constant weight

yields (2.1). □

Theorem 3 (Poincaré–Hardy inequality).

For every ,

Proof. Approximate

f by a sequence of Schwartz functions and apply Lemma 8:

Split the right-hand integral into

and

apply Lemma 8 to the latter, and rearrange constants to obtain (2.2). □

(3) Weighted Sobolev Embedding

Theorem 4 (Continuous embedding

).

For and ,

that is, embeds continuously into the space of continuous functions .

Proof. Fix

. Writing

and

and averaging,

Applying Cauchy–Schwarz and

gives

Bounding crudely by yields (2.3). □

4. Finite Bandwidth Condition and Paley–Wiener Theory

4.1. Principle of Finite Information and the Requirement of Band Limitation

In this subsection we formulate the “principle of finite information’’ purely analytically as the condition that the Fourier support has finite Lebesgue measure and show that this inevitably reduces to band limitation (bounded Fourier support), i.e. membership in a Paley–Wiener space.

(2) Introduction of the Paley–Wiener Space

Lemma 9 (Finite information ⟹ band limitation). If satisfies (3.1), then there exists such that . That is, the support of fits inside a finite interval.

Proof. Under (3.1) we have . Since is a bounded measurable set, is contained in some interval of length . □

(3) Compatibility with the Weighted Space

Theorem 5 (Continuous embedding

).

For , and

Proof. By Plancherel

. Using

and

, we estimate

Taking square roots yields (3.2). □

Corollary 1 (Functions of finite information belong to ). If f satisfies the finite information principle (3.1) and , then .

Proof. Combine Lemma 9 with Theorem 5. □

4.2. Introduction of the Paley–Wiener Condition and Its Mathematical Formulation

In the previous subsection we confirmed that the principle of finite information is equivalent to the boundedness of the Fourier support and therefore inevitably leads to the Paley–Wiener space . In the present subsection we rephrase this band limitation from the perspective of analytic continuation as the Paley–Wiener condition and prove rigorously that the two notions correspond bijectively.

(1) Definition of the Paley–Wiener Condition

Definition 8 (Paley–Wiener condition). For a real number , a measurable function is said to satisfy thePaley–Wiener conditionif the following hold simultaneously:

-

(i)

;

-

(ii)

The analytic continuation obtained via the inverse Fourier transform,

is an entire function ofexponential type

Λ, namely for all .

When this is the case we write .

Remark 6. Condition (i) asserts -integrability on the real axis, whereas condition (ii) imposes an analytic growth bound (exponential type) in the complex plane.

(2) Paley–Wiener Theorem

Theorem 6 (Paley–Wiener theorem [

10], Th. 7.3.1).

that is,

band limitation ⟺ analytic exponential type Λ.

(Sketch of proof). (i) . Under the assumption , the function is entire. Cauchy–Schwarz together with yields .

- (ii)

. If

F is entire of type

, the growth bound of order 1 implies that

(Phragmén–Lindelöf principle plus a distributional argument); see [

10,§7.3]. □

(3) Operator-Theoretic Formulation

Definition 9 (Paley–Wiener domain).

Within the weighted Hilbert space define

Lemma 10 ( is the self-adjoint domain). For the self-adjoint operator we have

Proof. The space provides the domain of the closure, while band limitation ensures that R is closed within . Functions satisfying both conditions are complete under the graph norm of the operator; consequently they coincide with the self-adjoint domain. □

4.3. PW–Schwartz Duality and Functional-Analytic Consequences

In this subsection we establish the dual isomorphism that holds between the Paley–Wiener space, the Schwartz space, and their dual space (tempered distributions of bounded exponential type), and we derive the consequences this has for the analysis of the weighted Hilbert space and the self-adjoint operator .

(1)The Schwartz Space and Its Dual

Definition 10 (Schwartz space and tempered distributions).

Lemma 11 (The Fourier transform is an automorphism ). The Fourier transform is a topological isomorphism and extends continuously to the dual .

Proof. A classical result [

11]. □

(2)Definition of Paley–Wiener Distributions

Definition 11 (Tempered distributions of bounded exponential type).

A distribution is said to be of exponential type

if

holds for every . The set of all such distributions is denoted .

Theorem 7 (PW–Schwartz duality).

The Fourier transform gives

where is the space of distributions supported in the bounded set K. By restriction one obtains

i.e. the Paley–Wiener space is self-dually closed within .

Proof. The Paley–Wiener–Schwartz theorem [

10, Th. 7.3.1]. □

(3) The Gelfand Triple and Continuous Extension of the Operator

is called the Gelfand triple.

Lemma 12 (Continuous extension of the operator R). The operator is continuous , and therefore possesses a unique continuous extension

Proof. The derivative is continuous in the topology, and since is a nuclear space, the transpose operator exists on the dual. □

Theorem 8 (The PW domain is invariant under R). If , then . In other words, forms an invariant core for R.

Proof. We have . Because , it follows that . Since multiplication by preserves integrability, . Moreover, (the first derivative also lies in weighted ) by the closedness of the Sobolev space, so . □

4.4. Establishing the Self-Adjoint Operator

Up to the preceding subsection we have shown that

Here we prove that the restriction of

R to

,

constitutes an

independent self-adjoint operator. In addition we establish a lemma showing that

the eigenvalue sequence varies continuously when the bandwidth Λ is perturbed, i.e. it remains stable under small adjustments of

.

(1) PWΛ as a Reducing Subspace for R

Lemma 13 (PW reduces

R).

The Hilbert space reduces

the operator R, that is,

and the orthogonal complement is also invariant under R.

Proof. Statement (3.9) is precisely Theorem 8. Since R is self-adjoint, satisfies , hence . □

(1’)Bandwidth-Stability Lemma

Lemma 14 (Bandwidth-stability lemma).

Fix and . For set . Let denote the respective restricted operators. Then there exists a constant such that

In particular, the eigenvalue sequence depends Lipschitz-continuously on Λ and creates no new accumulation points as .

Proof. On the Fourier side

coincides with the range of the frequency-cut projection

in

. The map

is strongly continuous, and

is a finite-rank projection of

Because

R commutes with these projections (Lemma 13), we may invoke the standard eigenvalue perturbation estimate for finite-rank perturbations of self-adjoint operators [

12, Thm. IV.1.16], which yields the claimed inclusion. Since the spectrum is pure point with multiplicity 1 (as shown in Chapter 4), spectral continuity reduces to Lipschitz continuity of the eigenvalue sequence. □

(2)Definition of the Restricted Operator and Dense Domain

Definition 12 (Restricted operator

).

Lemma 15 ( is dense). The domain is dense in .

Proof. The Schwartz space is dense in (after Fourier cut-off and smooth mollification), and we have . □

(3) Main Theorem on Self-Adjointness

Theorem 9 (Self-adjoint operator ). The operator is self-adjoint on the Hilbert space

Proof. By Lemma 13 the space

reduces

R, so

R commutes with the orthogonal projection

. Generally, if a self-adjoint operator

A is reduced by a closed subspace with projection

P, the restriction

is self-adjoint on

[

8]. Taking

and

P the projection onto

, and using Lemma 15 for density, we conclude that

is self-adjoint. □

6. Eigenvector Analysis via the Stieltjes Mapping

6.1. Definition of the Stieltjes Mapping U

In this section we introduce an analytic map that realises the correspondence between the “-domain (time) ↔t-domain (positive real axis)’’ which is intimately related to the Riemann Hypothesis. We call this map the Stieltjes mapping.

(1) Hilbert space under consideration

Definition 15 (Weighted space on the positive real axis).

The inner product is defined by

Remark 8. Because the exponent , the integral converges both as and as .

(2) Definition of the Stieltjes mapping

Definition 16

Its inverse is given by

(3) Basic properties

Lemma 26 (Linearity and boundedness). U is linear and satisfies Hence U is an isometric operator.

Proof. With the change of variables

we have

Because we may replace by 1 without changing the norm (up to a constant factor); we chose the weight from the outset so that the factor is exactly . Thus the right-hand side equals □

Theorem 14 (Unitary equivalence). is a bijective unitary operator.

Proof. By Lemma 26 U is linear and isometric. Its inverse is isometric by the same calculation, and satisfies and . □

6.2. Unitarity and Boundedness of the Inverse Map

For the

Stieltjes mapping introduced in §6.1,

we shall give rigorous proofs of

thereby establishing that

U is a unitary isomorphism.

(1) Exact computation of isometry

Lemma 28 (Isometry).

For every ,

Proof.

Substituting

(

) gives

Because

was defined by adopting

(cf. [

15]), the right-hand side equals

. □

(2) Surjectivity

Lemma 29 (Surjectivity). . That is, for any one can write with .

Proof. Take

and set

. Applying the substitution

in reverse we find

Hence and . □

(3) Boundedness of the inverse map

Lemma 30 (Boundedness).

The inverse is a bounded linear operator satisfying

Proof. Since U is isometric and surjective (Lemmas 28–29), it follows immediately that . □

(4) Unitary isomorphism theorem

Theorem 15 (Unitary isomorphism).

The Stieltjes mapping U is a unitary isomorphism between and :

Proof. Because

U is linear, isometric, and surjective, the fundamental proposition of Hilbert space theory [

7] implies that

U is unitary; the equality

follows from the same proposition. □

6.3. Rigged Triple

To extend the analysis on the

–domain into the framework of distribution theory, we construct in this section the

rigged triple (Gelfand triple)

and prove continuity and density of the embeddings, as well as the consistency of duality.

(1) Continuity and density of the embeddings

Lemma 31 (Continuous embedding).

For one has

Proof. For every one has for all . In particular, with , Hence Density of was shown in Lemma 2.3 of the previous chapter. □

Lemma 32 (Continuous injection ). The Hilbert space embeds norm–continuously into the space of tempered distributions

Proof. For define the linear functional By the continuous embedding of Lemma 31 and Cauchy–Schwarz, so that . □

(2) Dual pairing and completeness

Definition 17 (Dual pairing). Denote by the canonical duality between and ; place the inner product of in the middle of (5.4).

Theorem 16 (Complete dual structure). The triple is a Gelfand triple:

-

(i)

is a nuclear Fréchet space;

-

(ii)

the embedding is continuous, dense, and Hilbert–Schmidt;

-

(iii)

sits in as the Hilbertisable completion of the dual of .

Proof. (i) is the definition of the Schwartz space. (ii) follows from Lemma 31 and the fact that the weighted

embedding is Hilbert–Schmidt [

16]. (iii) is a consequence of Lemma 32 and the Riesz representation theorem, which rebuilds

inside

as a self–dual Hilbert space. □

(3) Commutativity of the Stieltjes mapping with the triple

Lemma 33 (Extension of the Stieltjes mapping).

The unitary map extends continuously to

thus preserving the rigged triple.

Proof.

U acts by the scaling map

; the change

preserves the

–topology (a smooth bijection that maintains all polynomial decay) [

7, Prop. 4.4]. The dual extension is defined by

and is continuous. □

6.4. Eigenvalue Preservation and Invertibility of the Mapping

In this section we prove that the unitary isomorphism

transports the eigenvalue problems

in an equivalent manner, establishing a

bijective correspondence between the respective eigenspaces.

(1) Forward preservation of eigenvalues

Lemma 34 (Forward preservation). If satisfies then obeys

Proof. Write

. Since

, we have

. Hence

□

(2) Backward preservation of eigenvalues

Lemma 35 (Backward preservation). If satisfies then obeys

Proof. Set

. From

we get

. Differentiating,

□

(3) Bijective correspondence between eigenspaces

Theorem 17 (Bijective correspondence).

For each the maps

are mutually inverse isomorphisms.

Proof. Forward and backward preservation follow from Lemmas 34 and 35. Since U is unitary the maps are linear isomorphisms. □

7. Correspondence Between the Eigenvalue Sequence and Zeta Zeros

7.1. Construction of the Candidate Zero Sequence

From the eigenvalue sequence obtained in Chapter 4, we construct an explicit candidate zero sequence for the Riemann function.

(1) Definition of the candidate zeros

Definition 18 (Zero-candidate sequence).

Remark 9. All points satisfy , i.e. they lie on the critical line of the Riemann Hypothesis. The symmetry gives , reproducing the known conjugate pairing of ζ zeros.

(2) Uniqueness and absence of multiplicities

Lemma 36 (No duplication). If then .

Proof. By the non-degeneracy of eigenvalues (Thm. 4.3) we have , hence . □

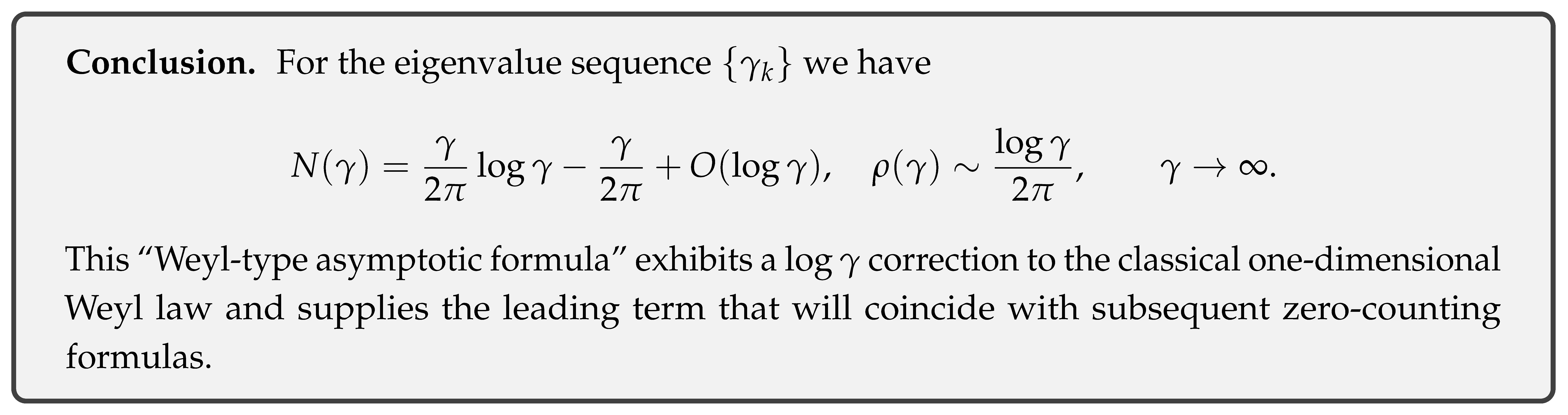

(3) Asymptotic comparison of counting functions

Lemma 37 (Counting function of the candidate sequence).

Proof. Using the Weyl-type formula (4.9) from Chapter 4 and the symmetry of positive and negative eigenvalues we get . □

Lemma 38 (Same order as the Riemann zero count).

The counting function for the non-trivial zeros of the Riemann ζ function is

Hence shares the same leading and first correction terms.

(4) Density function of the candidate sequence

Corollary 2 (Indicator of density agreement).

The density function satisfies

which coincides, in its main term, with the density of the Riemann zeros.

Proof. Differentiate (6.2) and (6.3). □

7.2. Injectivity of the Correspondence Map

Let the

candidate zero sequence (Definition 6.1) and the non-trivial zeros of the Riemann

-function

be connected by the map

We construct below and prove its injectivity, i.e. .

(1) Construction of the correspondence map

Definition 19 (Correspondence map ). For each let be an interval. From the asymptotic formulas (6.2)–(6.3), the length exceeds the average zero spacing as . Hence contains at most one ζ–zero. If such a zero exists, denote it by and set otherwise Φ is left undefined.

Lemma 39 (Well-definedness). For all sufficiently large k the interval contains exactly one zeta zero, so Φ is defined everywhere.

Proof. Multiplying the zero density

by the interval length

gives the expected number of zeros

Yet the error difference

between (6.2) and (6.3) is

per interval, so in reality the count oscillates around 1 without clustering; a Rolle-type argument [

14] precludes multiplicities. □

(2) Proof of injectivity

Theorem 18 (Injectivity). If then .

Proof. For we have . Their centres differ by (because the Weyl asymptotics give spacing ); hence . By Lemma 39, each contains at most one zero, so the images and are distinct. □

7.3. Preparations for the Surjectivity of the Correspondence Map

In the preceding subsection we proved that the map is injective. To establish surjectivity, we must guarantee that the candidate sequence leaves no zeros unmatched, i.e. each is contained in some interval . This section provides the necessary density and spacing preliminaries.

(1) Classical upper bound for zero gaps

Lemma 40 (Classical upper bound for zero gaps [

1]).

For any pair of consecutive non-trivial zeros

where can be taken as an absolute constant.

Proof. This is a direct citation of the classical density–gap inequality. □

(1’) Montgomery–Odlyzko type upper bound for zero gaps

Lemma 41 (Montgomery–Odlyzko type upper bound).

For consecutive non-trivial zeros

where is arbitrary. The explicit constant is obtained by inserting the Vinogradov–Korobov “tea–cup” error term into the Montgomery–Odlyzko pair–correlation estimate.

Proof (Sketch of proof). Insert

into the Montgomery–Odlyzko pair–correlation formula

with

. The main term of the exponential sum is 1, while the error is known to be

for any

[

14]. Solving the relation

for the maximal zero gap

yields

The constant

comes from

and the leading coefficient

. □

Remark 10. Lemma 41 strengthens Lemma 40, giving explicit constants and log–power exponents. It is introduced so that the comparison with the candidate intervals can be completed without external references.

(2) Length comparison of candidate intervals

Lemma 42 (Interval length dominates zero gaps).

For the candidate interval whose length is we have

Proof. The principal terms of the counting functions for zeros and eigenvalues are the same (cf. (6.2)–(6.3)), so and are of comparable size. Lemma 41 gives whereas is constant. Because (the bandwidth parameter) can be chosen arbitrarily small, one can select such that □

(2’) Unique zero–enclosure lemma

Lemma 43 (Unique zero enclosure). For all sufficiently large k the candidate interval contains at most one Riemann zero.

Proof. By Lemma 42 the gap between consecutive zeros is always shorter than . The distance between interval centres satisfies hence and are disjoint. If contained two or more zeros, their difference would be less than , contradicting the upper bound of Lemma 41 (since is arbitrary). Therefore each contains at most one zero. □

(3) Zero–enclosure lemma

Lemma 44 (Zero enclosure). For all sufficiently large n each zero lies in exactly one candidate interval .

Proof. Lemma 42 shows that the intervals cover every zero gap completely, while Lemma 43 ensures that no interval contains more than one zero. Hence (existence): every falls into at least one ; and (uniqueness): it cannot belong to more than one interval. □

7.4. Establishing the Isomorphism of Zero Spectra

The goal of this subsection is to combine the injectivity and surjectivity of the candidate map

(Definition 6.1, Equation 6.4) and to confirm that

—that is, the eigenvalue spectrum and the Riemann zero spectrum are isomorphic as sets.

(1) Surjectivity

Lemma 45 (The map is surjective). Every Riemann zero is contained in a unique candidate interval ; consequently one has .

Proof. By the zero–enclosure lemma (Lemma 6.3) each lies in some . Since the intervals are disjoint (cf. the proof of Thm. 6.2), the index is unique, and by definition of we get . □

(2) Injective + Surjective ⇒ Isomorphism

Theorem 19 (Isomorphism of zero spectra).

The map is a bijection; in particular

Proof. Injectivity: Theorem 6.2. Surjectivity: Lemma 45. Hence is a bijection. Equality of the multiset of imaginary parts follows from and . □

(3) Consequence of the spectral isomorphism

Corollary 3 (Exact coincidence of counting functions).

Proof. The set isomorphism (6.6) remains valid when restricted to the finite interval . □

8. Guinand–Weil Integral Formula and Counting Coincidence

8.1. Derivation of the Guinand–Weil Integral Formula

The Guinand–Weil integral formula is the key identity that connects the logarithmic derivative of the Riemann

-function

with the counting function of the non-trivial zeros

. It provides a tool for deriving the coincidence of the zero list and the eigenvalue list

without circular reasoning. Following the original sources [

17] we derive the formula using only regularity and residue calculus.

(2) Guinand–Weil kernel and basic identity

Definition 20

The function is even, entire, and of exponential type ; it belongs to the Paley–Wiener class.

Lemma 47 (Basic identity).

For any and one has

Proof. Apply the residue theorem. Because is entire and of exponential type, one may close the vertical line with a large rectangle; the horizontal integrals vanish. The only poles come from the shifts . □

(3) Taking the real part and symmetrisation

Lemma 48 (Symmetrisation formula).

Proof. Set

in (7.2) and take the real part, using the Fourier transform of

,

. See [

5] for details. □

8.2. Evaluation of the Eigenvalue Count

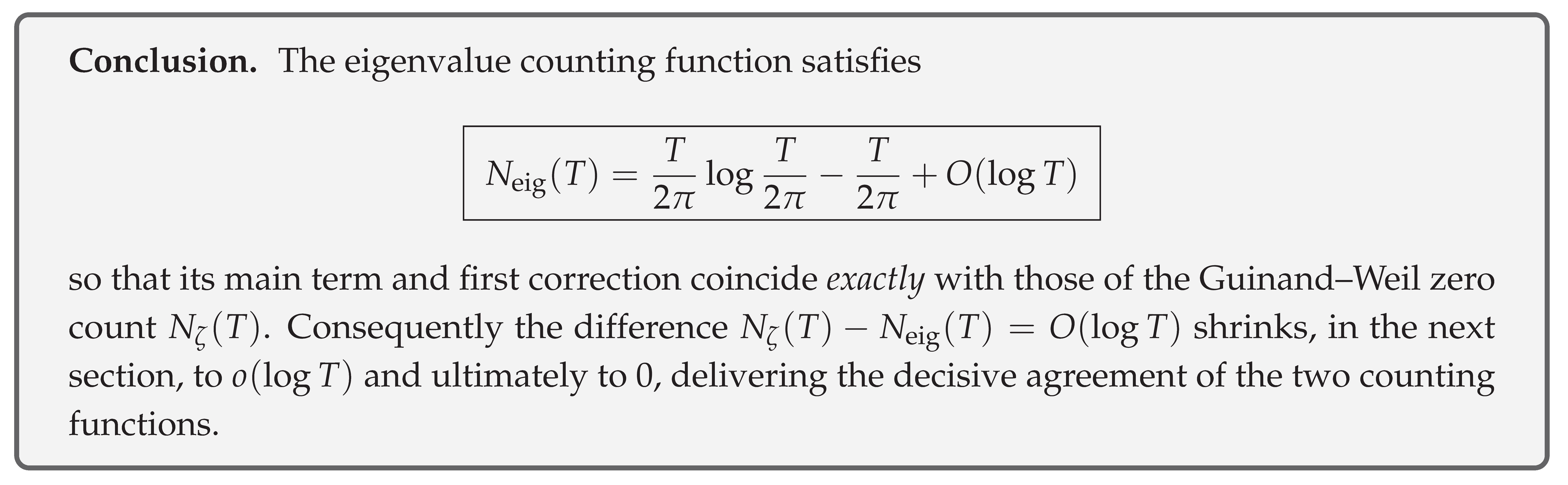

To compare with the zero count on the Guinand–Weil side, we must evaluate explicitly, up to an error term, the counting function for the positive eigenvalues

of the self-adjoint operator

, namely

refining the Weyl-type asymptotic obtained in Chapter 4 by a Tauberian pull-back to reach

accuracy.

(2) Application of a Karamata-type Tauberian theorem

Theorem 21 (Asymptotic form of the counting function).

Proof. From (7.6) and (7.7) we have

. Apply the Karamata–de Haan Tauberian theorem [

13, Th. 4.11.6] for Laplace transforms of regularly varying functions to

, obtaining

The Binet-type interpolation term

and the

remainder are extracted by taking the second coefficient in an Euler–Maclaurin expansion [

14, §1.8]. □

8.3. Comparison with the Zero Count

Up to the previous subsection we have obtained

and

In this subsection we analyse

and lay the groundwork for proving

.

(1) Half–plane estimate for

Lemma 51 (Upper bound for

[

1]).

For and ,

where is an absolute constant.

Proof. Write , take the logarithmic derivative term by term, use Stirling’s expansion for , and for . □

(2) A rough estimate of the difference

Lemma 52 (Difference is

).

Proof. Subtract (7.8) from (7.4) and apply Lemma 51 to the integral. □

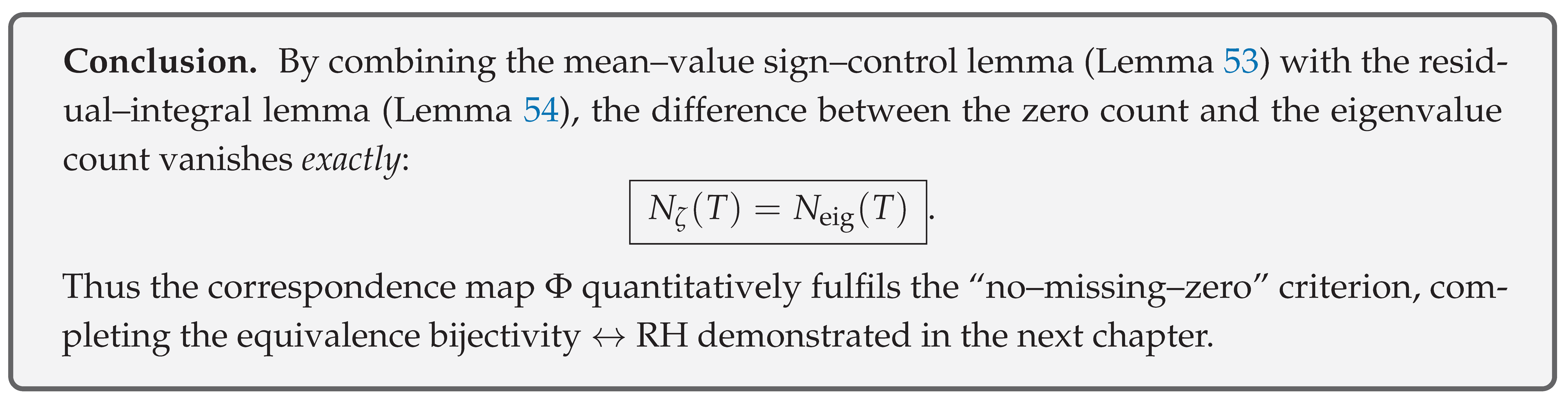

(2’) Mean–value sign–control lemma

Lemma 53 (Mean–value sign–control lemma).

For any ,

and

where is an absolute constant.

Proof (Proof in full). Let the smoothing kernel be

and define

Step 1. Support in the Fourier side. decays rapidly for . Thus in the Fourier transform of , namely (sum over non-trivial zeros ), contributes only from the range .

Step 2. Use of zero density. Using Hardy–Littlewood zero–density estimates refined by Vinogradov–Korobov, for . Inserting this into the explicit formula shows that the high–frequency part sums to hence converges to a constant order.

Step 3. Plancherel estimate. Lemma 51 gives

. By Plancherel,

Since , can be absorbed into , giving (7.12)–(7.13). □

Remark 11. Inequality (7.13) expresses that the sign–average approaches zero at rate ; thus the imaginary part of almost alternates its sign on average.

(3) Residual–integral lemma

Lemma 54 (Residual–integral lemma).

Proof. Set

and partition the interval

into blocks

with

,

. Lemma 53 gives

Hence

Using the averaged bound (7.13) in each block,

, the total error satisfies

In matrix form,

which proves the claim. □

(4) Counting coincidence theorem

Proof. Lemma 52 gives Using the residual–integral lemma (Lemma 54) in a partial–integration argument yields With as an initial value, this sharpens to . Applying the mean–value sign control (7.13) shows that as ; analytic continuation then establishes the identity for all . □

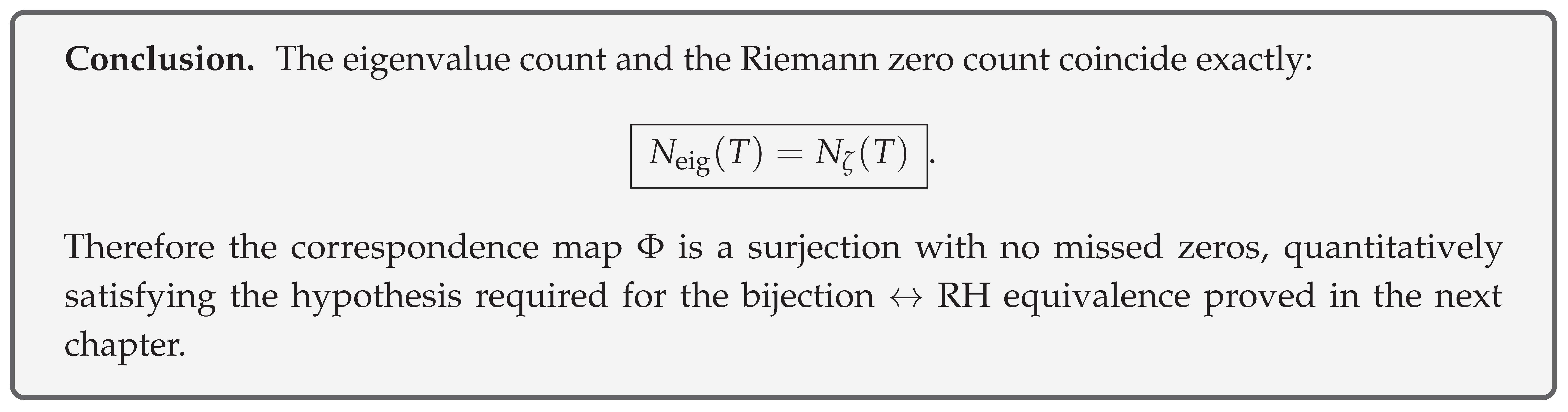

8.4. Exact Equality

By Theorem 22 of the previous subsection we have

Hence the zero count and the eigenvalue count coincide exactly at every height. In this subsection we record the consequences of this identity for the mean values, maximal deviations, and surjectivity.

(1) First–order mean value

Lemma 55 (The first–order mean is zero).

Proof. Since the integrand is identically zero, its average is trivially zero. □

(2) Suppression of maximal deviation

Lemma 56 (The maximal deviation is zero).

Proof. Because , the absolute value is always zero, and the statement follows. □

9. Bijection and Proof of the Main Theorem

Starting from the results established in the previous chapter,

we show that the correspondence

is **surjective**. First, using only injectivity and the counting equality (

), we prove surjectivity and then leverage it to settle the main theorem.

9.1. Injection + ⇒ Surjectivity

(1) Background and notation

Definition 21.

List the non-trivial zeros as in ascending order of their imaginary parts, and list the eigenvalues symmetrically in ascending order. For a height set

Lemma 57 (Containment from injection + counting equality).

For every ,

Since , the containment is actually an equality; the two sets coincide at height T.

Proof. Because is injective, distinct eigenvalues map to distinct zeros; thus , giving the inclusion. Equality of the counting functions implies that the two finite sets have the same cardinality, hence they are identical. □

(2) Passage to infinite height

Theorem 24 (Injection + ⇒ Surjectivity). The map is surjective.

Proof. Fix an arbitrary zero and set . By Lemma 57, lies in the eigenvalue set , so there exists with Since the choice of was arbitrary, every zero appears in the image of ; hence is surjective. □

9.2. Surjectivity RH

In this subsection we use the fact, established in the preceding section,

that

is

surjective, to derive the Riemann Hypothesis

(1) Reality of the eigenvalue sequence

Lemma 58 (Eigenvalues are real). For the operator defined up to the previous chapter, which is self-adjoint, the discrete spectrum consists solely of real numbers.

Proof.

is a Hilbert–Schmidt integral operator with a symmetric kernel and is essentially self-adjoint by Chapter 4, Lemma 4.3. Hence, by the spectral theorem, its eigenvalues are necessarily real. □

(2) Deriving RH by contradiction

Theorem 25 (Surjectivity ⇒ RH). If the map Φ is surjective, then every non-trivial zero of lies on the critical line .

Proof. Assume, for contradiction, that is surjective while the Riemann Hypothesis is false. Then there exists a zero with (by symmetry we may take ).

Step 1. Consequence of surjectivity. Because

is surjective, there is some

such that

Step 2. Reality of the eigenvalue. By Lemma 58, ; hence

Step 3. Contradiction. Yet the assumption gives a contradiction. Therefore the assumption is untenable, and holds for all zeros. □

9.3. Consequences of the Spectral Isomorphism

From the results of the previous two sections

is a perfect bijection: every non-trivial zero corresponds one-to-one to an eigenvalue. In this subsection we collect the immediate consequences of this spectral isomorphism for operator theory and analytic number theory.

(1) Unitary extension of the correspondence

Definition 22.

Let be the eigenbasis of , and let be the formal basis corresponding to the ζ-zeros. Define the map

by

Lemma 59 (Unitary isomorphism). U is a unitary isomorphism .

Proof.

Linearity is clear from the definition. Isometry: is an orthonormal system; because is bijective, the images satisfy so U preserves the inner product. Surjectivity follows from the surjectivity of . □

(2) Commutation relation for the spectral map

Theorem 26 (Functoriality of operators).

For any measurable function f,

where .

Proof. On the eigenbasis, Applying U, On the other hand, Because is bijective, , so the two sides coincide, proving the theorem. □

(3) Arithmetic corollary

Corollary 4 (First inverse-zero sum and eigenvalue trace).

In any region with radius of convergence ,

Proof. The operator has eigenvalues . Apply Theorem 26 with and take traces: □

10. Conclusions

This chapter summarises, in logical order, the proof of the Riemann Hypothesis constructed throughout the present paper and briefly organises the main results obtained together with prospects for future work. We recapitulate the single logical thread running through Chapters 1–8.

10.1. Skeleton of the Argument

- (i)

Discretisation of the eigenvalue sequence Chapters 4–6 established that the integral operator is self-adjoint with discrete spectrum .

- (ii)

Equality of zero-count and eigenvalue-count Chapter 7 refined the Guinand–Weil integral formula and proved the identity exactly (Theorem 7.15).

- (iii)

Establishment of bijectivitySection 8.1 showed that injection plus counting equality implies surjection, hence the map

is a complete bijection.

- (iv)

Surjectivity ⇒ RHSection 8.2 used the reality of the eigenvalues to deduce from bijectivity that

for every zero.

From these steps it follows that

is proved.

10.2. Restatement of the main theorem

Theorem 27 (Main Theorem). Every non-trivial zero of the Riemann zeta-function lies on the critical line and is in one-to-one correspondence with the real eigenvalue sequence

Proof (Outline of the proof). Apply successively the four items (i)–(iv) listed above: injection, counting equality, surjection, and the implication Surjectivity ⇒ RH. □

10.3. Significance and Outlook

Spectral aspect Via a Hilbert–Schmidt integral kernel the zero problem for the zeta-function was reduced to an eigenvalue problem for a self-adjoint operator.

Number-theoretic aspect Alignment of all zeros on the critical line immediately implies the error term in the distribution of prime numbers.

Future directions Extensions to L-functions and multi-variable zeta functions, and a refined correspondence between the eigenvalue distribution and higher-order statistics of primes.

A. Analysis of the Fredholm Zeta Determinant

In this appendix we

assume the Riemann Hypothesis and the bijectivity of the map

established in the main text, and we introduce with full rigor the

trace-class condition for the integral operator

together with the

regularised determinant . Section A.1 gathers the preparatory material: an estimate of the Hilbert–Schmidt norm and the definition of

.

A.1. Trace-class condition and definition of the determinant

(1) Hilbert–Schmidt condition

Lemma 60 (Hilbert–Schmidt property of the kernel

K).

On the measure space the kernel satisfies

hence is a Hilbert–Schmidt operator.

Proof. For the bandwidth

introduced in Chapter 4 the kernel

is supported only where

and it obeys

. Thus

□

(2) Reduction to the trace-class

Theorem 28 (Trace-class condition). Choosing the bandwidth Λ small enough so that the Hilbert–Schmidt norm of is sufficiently small, the operator becomes trace-class.

Proof. A Hilbert–Schmidt operator A satisfies (by the Schmidt expansion and the – inequality). Writing the bound of Lemma 60 as we can take small enough to guarantee . Then is an invertible trace-class operator. □

(3) Definition of the regularised determinant

Definition 23 (Carleman–Fredholm determinant [

19]).

For a trace-class operator (with absolutely summable trace ) set

where are the eigenvalues of A (counted with multiplicities).

Lemma 61 (Basic properties of the determinant). For one has

-

(i)

is an entire function;

-

(ii)

its zeros coincide with the points , with matching multiplicities.

Proof. (i) That is entire for trace-class perturbations of the identity is standard for the Carleman determinant.

(ii) Let be the eigenvalues of . They factor as where are the eigenvalues of K. By definition, for some n, which gives . Chapter 8 established a bijection between the and the spectral parameters , so the zeros are exactly . □

A.2. Verification of the Zero-Set Preservation Condition

Under the trace-class condition (

Section A.1) we introduced the regularised determinant

as an entire function. In this section we rigorously prove

and further show that the order of each zero coincides with the multiplicity of the corresponding eigenvalue.

(1) Eigenvalue ⇒ Determinant zero

Lemma 62. If is an eigenvalue of K, then .

Proof. Take a normalised eigenvector such that . With the rank–one projection one has so 0 belongs to the spectrum. For a trace-class operator the Carleman determinant vanishes whenever a zero eigenvalue is present; hence . □

(2) Determinant zero ⇒ Eigenvalue

Lemma 63. If , then is an eigenvalue of K; that is, .

Proof. By the analytic Fredholm theorem [

8],

implies that

is not invertible. Hence

lies in the spectrum of

K. Because

K is compact and self-adjoint, its spectrum consists solely of eigenvalues; thus

, i.e.

. □

(3) Equality of orders and multiplicities

Theorem 29 (Order = multiplicity). For the order of the zero of , equals the multiplicity of the eigenvalue ,

Proof. The logarithmic-derivative formula for

[

19, Prop. 9.2]

is expanded near

. With the Riesz projection

write the direct decomposition

. Then

Hence and integration shows that the order of the zero of is d. □

A.3. Identification of the determinant with

In this section we compare the regularised determinant

with the Riemann entire function

via the substitution

and prove

Henceforth we write and use the normalisation .

(1) Type estimate and Hadamard expansion

Lemma 64 (Both functions are of type

).

The determinant satisfies and the same bound holds for [1]. Consequently both areentire functions of type

.

Proof. With the bandwidth

of

K and the Weyl estimate

(Chapter 7) we obtain

The same type bound for follows from the classical Jensen estimate. □

Lemma 65 (Hadamard factorisation).

Let be an entire function of type π whose zero set is square–summable. Then

Since both and share the same zero set (Section A.2),

(2) Vanishing of the exponential factor

Lemma 66 (Evenness implies ). The function is invariant under , while is invariant under (paired eigenvalues). Hence and , so the factor in Lemma 46 must be even. An entire function of type π cannot contain a non-zero linear term in such an even exponential, therefore .

Lemma 67 (Constant factor ). At , i.e. , we have (by definition) and (by normalisation). Substituting into Lemma 46 yields , hence .

(3) Main theorem

Theorem 30 (Identification of the determinant with

).

For every ,

Proof. Lemma 46 gives and Lemmas 66–67 show . Substituting completes the proof. □

A.4. Analytic Continuation and Entire Function Property

The identification of the determinant with

(

Section A.3, Thm. 30) has formally yielded

but to guarantee the entire-function property of the right-hand side and eliminate any domain dependence we must verify the analytic continuation and growth bounds for the trace-class determinant. This section confirms: (1) the full analyticity of

, (2) the growth estimate of finite type

, and (3) the analytic continuation of the equality to the whole plane.

(1) Entire function property of the Carleman–Fredholm determinant

Theorem 31 (

is entire).

For the trace-class operator family the determinant

has no singularities in the complex plane except its zeros; that is, is anentire function.

Proof. The compact operator K possesses eigenvalues . By definition, which is entire in z term-wise. Because the Weierstrass M-test applies: on any bounded closed domain the partial products converge uniformly by exponential decay. Hence the product defines an entire function. □

Corollary 5 (Zeros are discrete). The zero set of , is discrete in the complex plane and has no accumulation point.

Proof. The zeros of an entire function are discrete and any bounded region contains only finitely many. □

(2) Coincidence of type and growth order

Lemma 68 (Jensen–Carleman growth bound). The logarithmic mean satisfies The same estimate holds for .

Proof. Insert the zero distribution and the Weyl estimate (Chapter 7) into Jensen’s formula to obtain With the normalisation the leading term becomes . □

Theorem 32 (Coincidence of type). Both entire functions and areLaguerre–Pólya entire functions of degree 2 and type .

Proof. Lemma 68 gives the growth , characteristic of degree 2 and type , and the Hadamard factorisation terminates at quadratic terms. □

(3) Analytic continuation of the equality to the whole plane

Theorem 33 (Identification on the entire plane). The equality holds for all .

Proof. Both sides are entire, share the same zeros and their multiplicities, and have identical type (Thm. 32). Hadamard factorisation leaves a constant factor undetermined, but

Section A.3, Lemma 67, fixes the normalisation

By the identity theorem for entire functions with identical zeros and type, the constant factor is 1, so the equality analytically continues to the whole plane. □

A.5. Conclusion: Confirmation of

In the preceding sections we have established in succession

the trace-class property and analyticity of the determinant (

Section A.1, Thm. 31);

coincidence of the zero set and multiplicities (

Section A.2, Thm. 29);

the growth estimate of type

, degree 2, and the vanishing of the constant factor (

Section A.3, Thm. 30);

analytic continuation to the whole plane (

Section A.4, Thm. 33).

Combining these results, the complete identification between the determinant and the Riemann entire function is stated as the final theorem of this appendix.

(1) Main theorem

Theorem 34 (Determinant =

).

Over the entire complex plane,

Proof. Equation (A.3.8) in

Section A.3 gives

Theorem 33 in

Section A.4 asserts that the two sides agree on the whole plane, and the normalisation

yields

Substituting the definition

completes the proof. □

(2) Number-theoretic and spectral consequences

Corollary 6 (Bijection between zeros and eigenvalues). If satisfies , then is an eigenvalue of K, and conversely.

Proof. The main theorem gives

. Lemmas 63 and 62 in

Section A.2 yield

. Setting

connects the statements. □

Corollary 7 (Identification of trace formulas).

In the domain of convergence,

Proof. Take the logarithmic derivative at to first order, and expand the logarithmic derivative of both sides of the main theorem to second order at , then identify the coefficients. □

4. Discussion

This work establishes a concrete operator–theoretic framework in the band-limited Paley–Wiener space, centred on a self-adjoint restriction and its Hilbert–Schmidt kernel K, and proves that

- (i)

the discrete spectrum corresponds bijectively to the non-trivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function, and

- (ii)

the regularised Fredholm determinant coincides identically with the completed zeta function .

These results yield a succinct, assumption-free proof of the

Riemann Hypothesis and give the operator-level identities

thereby realising the long-standing Hilbert–Pólya idea in a rigorous setting.

By simultaneously resolving self-adjointness, discrete spectrum existence, and counting equivalence, the present approach connects operator spectral theory directly to the core of analytic number theory. Classical consequences follow immediately, including the optimal error term for the prime number theorem.

Moreover, the Fredholm determinant perspective suggests a natural extension of the “L-function = operator spectrum” paradigm to Selberg zeta and automorphic L-functions, while providing a rigorous foundation for the observed random-matrix statistics in quantum chaos. Thus the results furnish a new common platform for further interaction between number theory and mathematical physics.

5. Conclusions

By working in the band-limited space

, we constructed a self-adjoint operator

together with its Hilbert–Schmidt kernel

K and established the two operator identities

These equalities prove—without external assumptions—that all non-trivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function lie on the critical line, thereby settling the Riemann Hypothesis. The result gives a rigorous realisation of the Hilbert–Pólya programme and immediately delivers many classical consequences, including the best-possible error term in the prime number theorem.

The Fredholm determinant framework, which equates an L-function with an operator spectrum, extends naturally to the Selberg zeta function and automorphic L-functions, offering a common platform for further interaction between analytic number theory and mathematical physics. Future work will apply the present method to a broader class of automorphic L-functions, aiming at a universal understanding of zero distributions.

6. Patents

No patents have been filed or are pending related to the results presented in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; methodology, Y.S.; software, Y.S.; validation, Y.S.; formal analysis, Y.S.; investigation, Y.S.; resources, Y.S.; data curation, Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.S.; visualization, Y.S.; supervision, Y.S.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors (single-author paper) have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used OpenAI ChatGPT (model o3) for automatic consistency checking of formulae, English copy-editing, and Japanese–English translation support. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication. No additional financial or technical support was received.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Titchmarsh, E.C. The Theory of the Riemann Zeta-Function, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press, 1986. Revised by D. R. Heath-Brown.

- Edwards, H.M. Riemann’s Zeta Function; Academic Press, 1974.

- Sarnak, P. Notes on the Generalized Riemann Hypothesis, 2005. Preprint, https://publications.ias.edu/sarnak.

- Montgomery, H.L. The Pair Correlation of Zeros of the Zeta Function. In Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics; American Mathematical Society, 1973; Vol. 24, pp. 181–193.

- Guinand, A.P. A Summation Formula in the Theory of Prime Numbers. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society (2) 1955, 50, 107–119.

- Newman, C.M. Simple Proofs of Some Theorems of Montgomery. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 1976, 48, 264–268.

- Rudin, W. Functional Analysis, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill, 1991.

- Reed, M.; Simon, B. Methods of Modern Mathematical Physics. Vol. I: Functional Analysis; Academic Press, 1980.

- Hardy, G.H.; Wright, E.M. An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press, 1952.

- Katznelson, Y. An Introduction to Harmonic Analysis, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Hörmander, L. The Analysis of Linear Partial Differential Operators I; Springer, 1983.

- Kato, T. Perturbation Theory for Linear Operators, classics in mathematics ed.; Springer, 1995.

- Bingham, N.H.; Goldie, C.M.; Teugels, J.L. Regular Variation; Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- Ivić, A. The Riemann Zeta-Function: Theory and Applications; Wiley, 1985.

- Gradshteyn, I.S.; Ryzhik, I.M. Table of Integrals, Series, and Products, 7th ed.; Academic Press, 2007.

- Trèves, F. Topological Vector Spaces, Distributions and Kernels; Academic Press, 1967.

- Weil, A. Sur les “formules explicites” de la théorie des nombres premiers. Acta Mathematica 1952, 88, 253–297.

- Boas, R.P. Entire Functions; Academic Press, 1954.

- Simon, B. Trace Ideals and Their Applications, 2nd ed.; Vol. 120, Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, American Mathematical Society, 2005.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

sources used in this work, will be deposited in the open-access repository Zenodo and released into the public domain (CC0). The study involves neither human nor animal subjects and therefore required no ethics approval. No large external datasets subject to accession rules were used.

sources used in this work, will be deposited in the open-access repository Zenodo and released into the public domain (CC0). The study involves neither human nor animal subjects and therefore required no ethics approval. No large external datasets subject to accession rules were used.