2. Research Objective

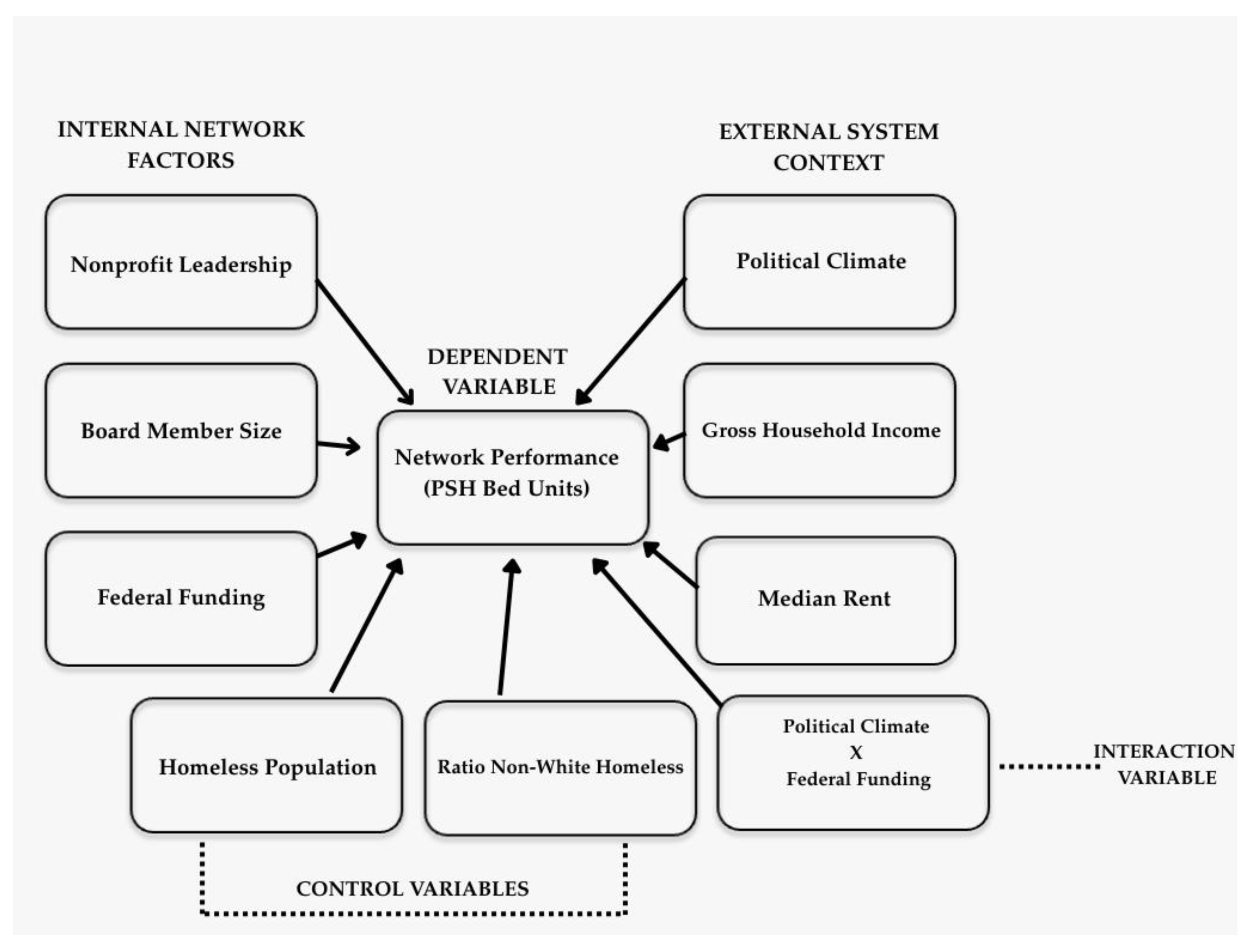

This study explores the performance of public service network in context of human services-specifically homeless service networks’ ability and capacity to provide homeless services to the vulnerable homeless population. It explores the critical internal network factors like board member size, leadership and funding and external system context like political climate, gross household income and median rent, and its effect on the CoC network’s ability to perform effectively. By incorporating both internal factors and external system contexts, and exploring real-world performance of CoCs, the study provides a more nuanced understanding of the complex interactions shaping CoC performance.

The study contributes to the field of public service network performance research in several ways. First, the study includes multiple internal network conditions and external system context factors such as nonprofit leadership, board member size, federal funding, political climate, and socioeconomic conditions as influencers of network performance to offer a comprehensive evaluation of network performance within the context of public service delivery networks. There have been significant advances in the study of public service network performance over the past where scholars have tested various network factors such as leadership, network size, funding, and external socio-political conditions as potential influencers of CoC performance [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], however, there are still significant gaps remaining in the study of public service network performance which lacks a comprehensive study that considers both internal network factors and external system context to study the network performance. Public service network performance studies that examine the impact of external system contexts as critical influencers of network performance remain scarce. These may include socioeconomic conditions, policy or political climate, that can significantly influence network performance [

12,

13]. It is the surrounding system context factors which can be a host of political, legal, socioeconomic, environmental (Emerson et. al., 2011), and other influencers that affect, and are affected by the collaborative governance networks. The collaborative governance evolves within this system context which are multi-layered and can create opportunities as well as pose unanticipated challenges, for example- an election, economic downturn, new regulation, natural disaster, thereby influencing network dynamics and network performance. In this regard, system context are critical influencers of network as they can affect its performance anytime expectedly or unexpectedly.

For instance, Mosley and Park (2022) examined how external political conditions, such as local government support for affordable housing initiatives, shape the performance of Continuum of Care (CoC) networks. They found that political environments that prioritize housing solutions help CoC networks succeed, while restrictive zoning regulations or political opposition can hinder their efforts. Dobbin et al. (2022) studied socioeconomic conditions and found that they also drive network performance outcomes. However, these studies focus on only qualitative methods and small sample sizes of fifty or less to explain external environment factors as key determinants of network performance leaving a gap to pursue statistical analysis research to explore the same which this research explores.

Second, this study develops a theoretical foundation by integrating two influential theories of network performance: Ansell and Gash's (2008) collaborative governance theory, which focuses on internal network dynamics, and Emerson et al.'s (2011) integrative framework of collaborative governance, which includes environmental factors that are the system contexts as determinants of performance. While their theories provide a theoretical framework and generic foundation for evaluating public service network performance, this study applies and tests these theories in a human and social service setting of public service-most specifically the homeless service network.

There is a need for innovative theories that reflect current social, economic, and political contexts. While a few scholars have developed configurational theories to measure network performance, these approaches are still at nascent stages. For example, Turrini et al. (2010) conducted a meta-analysis to explain network performance based on Provan and Milward's (1995) framework, proposing structural and functional characteristics of networks as key performance factors. Raab et al. (2013) added network age as a factor in their analysis and used more complex data analysis techniques to explore nonlinear relationships. Wang (2016) also developed a configurational theory using Provan and Milward's model but found, contrary to their conclusions, that network density, rather than centralization, is more important in influencing performance. These findings need further exploration using new theories which this research aims to address.

And third, this research deploys a robust statistical method of regression using a large sample size of 343 CoC networks across the United States to address the issue of generalizability and reliability. Research on studying network factors and their effect on network performance using rigorous methods often involve small sample sizes, limiting the generalizability and reliability of their findings. For instance, Wang (2015) demonstrated data analysis but with a sample size of fewer than fifty cases. This study fulfills the research objectives by exploring the following research question: What internal network conditions and external system contexts affect the performance of CoC networks in delivering homeless services?

The study examines the determinants of Continuum of Care (CoC) network performance through statistical analysis of network-level factors. This inquiry is particularly timely, as CoC performance offers valuable insight into the conditions and mechanisms that influence effective collaboration in addressing homelessness. By analyzing a national sample of 343 CoCs across the United States, the study explores both internal network dynamics and the influence of external system context on performance variation. As HUD (2023) mentions, this measurement involves identifying performance indicators and criteria, collecting relevant data, and using a measurable and quantifiable approach to assess progress. In addition to this, by exploring which of the internal factors and system context have strongest influence on CoCs, CoCs can compare, improve, sustain and justify their efforts and ensure that resources are being directed where they will have the most significant impact for the vulnerable homeless population that need them.

3. Theoretical Framework

The research integrates Ansell and Gash’s (2007) collaborative governance theory, which emphasizes the importance of broad network membership, inclusive network structures, facilitative leadership and rich resources, with Emerson et al.’s (2011) collaborative governance framework, which considers for external environmental conditions-that are the system context such as political climate and socioeconomic conditions that shape collaborative network performance. The dual-theory approach allows for a comprehensive assessment of CoC networks, considering both internal network dynamics and broader external system-level influences.

Ansell and Gash’s (2007) collaborative governance theory that argues that inclusion of large number of board members that are diverse, and that are affected by, or care about the issue helps in successful collaboration outcomes and that leadership of collaborative governance networks must be facilitative with leaders within the community who are organic and operate within the stakeholders’ community.

Emerson et al.’s (2011) integrative framework of collaborative governance defines external environmental factors as system context such as political climate and socioeconomic conditions which affect the collaborative network process and outcomes. The system context in Emerson et al. (2011) integrative framework demonstrates a significant addition to Ansell and Gash (2007) theory, in that it considers wider system factors that are external to the collaborative governance network but significantly influence collaborative process, outcome and overall performance.

System context in Emerson et. al. (2011) framework is the surrounding system context factors which can be a host of political, legal, socioeconomic, environmental and other influencers that affect, and are affected by the collaborative governance networks. It states that collaborative governance evolves within this system context which are multi-layered and can create opportunities as well as pose unanticipated challenges, for example- an election, economic downturn, new regulation, natural disaster thereby influencing network dynamics and network performance. In this regard, system context are critical influencers of network as they can affect its performance anytime expectedly or unexpectedly. While Emerson et al. (2011) framework provides an overall generic theoretical framework to assess public service network performance, we apply this system context and test it in a social and human services context – more specifically, the homeless service network. System contexts are critical to be examined for CoC network performance as well as political climate and socioeconomic conditions can enhance or impede a CoC network’s ability to performs successfully. For example, CoC may have challenges if the political climate of their area restricts the development of affordable housing or imposes zoning regulations that will seriously limit the placement of homeless shelters and supportive housing. The CoCs collaborate with the federal, state, and local governments to execute and grow homelessness services. The political climate can affect the government's will to work with the CoCs and provide them with resources and support. In a supportive political climate, there opens opportunities for CoCs for coordination, resource acquisition, and collaboration. The political climate also helps shape the public's perception of their support for effective homelessness solutions.

The integration of these theories provides a structured framework for evaluating CoC networks and contributes to the broader literature on public service network effectiveness. The study tests this collaborative governance theory in the context of homeless services, that is the CoC network for which collaboration is not only necessary, but also mandatory.

Seven hypotheses are formulated to test the effects of nonprofit leadership, board member size, federal funding, political climate, gross household income, and median rent as independent variables on the dependent variable- CoC network performance which is operationalized by PSH bed units’ availability. The study hypothesizes that nonprofit-led CoCs, larger CoC board, and higher federal funding will enhance network performance (measured by PSH service availability) by fostering inclusivity and resource mobilization. It also hypothesizes that favorable political climates will have positive effect on PSH service availability where political climate and policies supportive to homelessness will help in smooth delivery of homeless services for the CoCs with minimal political barriers. It also posits that CoCs in areas with higher gross household income have higher PSH availability due to rich resources and that areas with high median rent will have lower PSH availability due to housing unaffordability and limited housing supply issues. Similarly, an interaction variable is explored where effect of political climate on federal funding is tested. A hypothesis- a favorable political climate will aid in high federal funding is formulated.

Hypothesis 1 : CoC networks led by nonprofit organizations will have higher Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) bed unit availability

Ansell and Gash (2007) emphasized the role of leadership in improving collaborative network outcomes. The type of organization that leads the collaborative network significantly affects how the network initiates, performs and sustains. Their collaborative governance theory stresses on the need to engage of diverse non-state actors like nonprofit and community members to contribute their unique resource, skills, experience and perspective for solving public and social issues through collective decision making and problem solving [

15]. In this context, the type of lead agency that manages and leads this kind of diverse network also needs to be diverse and inclusive with members from different backgrounds. Diversity and inclusivity also helps create legitimacy and credibility as it reflects decisions and interests of wider individuals. Most public service networks like the CoC network include organizations from public, nonprofit and for-profit sectors. Each sector has their own set of strategies and capacities on how they operate and manage in a network. Therefore, the type of lead agency can have varying effect on the network performance depending on what type of agency is leading the network-nonprofit or government.

Public service network that are led by nonprofits and those that are led by government agencies as Valero et al., (2021) suggest, will have different strategies to manage network, achieve network mission, mobilize resource and expertise and solve problem and conflict. Nonprofits are also increasingly becoming a choice to lead the public service network to deliver public goods and services, primarily in human and social services like homelessness, education, and health care [

7]. Multiple empirical studies have shown the effectiveness of nonprofits within public service networks. Valero and Jang (2016), in their study of nonprofits' role in homeless networks, found that nonprofits are key actors in delivering the federal homeless policy and that they take coordination and leadership roles consolidating the efforts of the entire homeless network working to reduce homelessness in the community. Feiock and Jang (2009), in their study of nonprofit contracting in providing elderly service, state that nonprofits significantly mitigate conflicts and tensions between the community and the government since they can relate to community values better than the government.

Nonprofits are increasingly taking network leadership roles in public service networks [

9] in addition to only being a service provider in the network. While the government creates policies and funds service programs, nonprofits take charge to implement and lead them to get positive outcomes. In this context, nonprofits are shifting from only co-production to a more diverse role of co-governance, such as design, operation, advocacy, implementation, and network leadership [

1,

7]. With their proximity to the community, skills, and flexibility, nonprofit can be considered a network partner that has a unique set of distinctive characteristics and skill set to pool resources, skills, and expertise not only from the organization but also from the community by promoting community engagement [

36] in solving the community problems. The nonprofit sector plays a significant role in the network for mobilizing the social capital and resources within the community for public service delivery.

Hypothesis 2 : Continuum of Care (CoC) networks with larger board member size will have higher Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) bed unit availability.

Ansell and Gash (2007) establish that increased collaborative network performance can be achieved by including many diverse organizations, actors and stakeholders of broad and diverse backgrounds, skills, and expertise. Including such multiple actors enables legitimacy in the collaboration and effective mobilization of power, resource, and expertise. Other studies consider network size as a significant condition for assessing collaboration network processes, outcomes, and effectiveness. In their study of public-nonprofit collaboration in homeless services, Valero, Lee, and Jang (2021) found that the network size significantly impacted the network's capacity to secure federal grants. Their study found that a network that can engage many organizations has a greater capacity to manage service networks and have positive network performance. More extensive networks can serve as a proxy of professionalization to engage in specialized homeless policies [

9], will have a greater capacity to mobilize resources, skills, and expertise and manage the network for better outcomes. HUD has specific requirements for the CoC’s composition of board members including that the CoC board must include organizations or projects that serve homeless within the CoC’s geographic area and that it must have at least one homeless or formerly homeless person in the board [

18]. However, the number of board members is not mandated by HUD and these numbers vary among CoCs boards.

Multiple studies show that the board size impact CoC performance particularly in areas of resource allocation program outcomes [

2,

15,

17] and governance [

1]. Large board size is seen to have positive outcomes especially for programs that have diverse needs [

17].

While incorporating board members with expertise that aligns with CoC goals from areas like health, housing and nonprofits is important to stay focused on shared goal, large board size must be balanced with inclusivity, efficiency and clear governance structures to enhance performance. If members from the community are at the planning table, getting involved in decision-making, the realistic needs of the community can be identified and worked upon to address and cater to those needs. There is no one-size that fits all for the number of board members [

17], but the size must align with the CoC’s operational context and its goals. Too small board may lack expertise while too big board size may have coordination challenges. Board size based on CoC’s community needs, goals and representation from the stakeholders including homeless people is essential to ensure effective service delivery. Defining roles, responsibilities and accountability will help establish clear roles, regardless of the board size to ensure CoC’s goals are met.

Hypotheses 3 : CoC networks that receive higher amounts of federal funding will have higher Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) bed unit availability.

Provan and Milward (1995) established that when a network operates in an environment with rich resources, the network effectiveness of such a network improves significantly from low to high. This is supported by additional network characteristics such as network stability and integration. Resource is therefore, one of the main conditions that help to explain the differences in network performance and are deemed paramount in maintaining effective network performance. Thomson and Perry (2006) assert that resources are critical for collaborative performance success. Jang, Valero, and Jeong (2020), in their study of cross-sector health service for the homeless, found that collaborative service model like the Continuum of Care (CoC) networks helps the community to pool resources to provide medical and health service needs of the homeless individuals. The study showed that the CoC network effectively tackled and responded to the health challenges by providing multiple health services to the homeless. In this study of CoC network performance, the major funding source- the funding by federal body, HUD (Department of Housing and Urban Development) is utilized and hypotheses three tests the effect of this federal funding on network performance.

The federal funding by HUD is the primary source of fund for Continuums of Care (CoCs), that helps CoC and provide critical homeless services such as permanent supportive housing, rapid rehousing, and emergency shelter. Without the significant HUD resources, CoCs face resource deficit in their efforts to address homelessness. As of now, HUD provides over

$3 billion annually through the Continuum of Care (CoC) Program to support efforts to end homelessness nationwide. During the financial year- FY 2023 CoC Competition, HUD awarded funding to approximately 7,000 projects across all CoCs in the United States. This supported housing services for more than 1.2 million people experiencing homelessness each year [

43].

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) investment have significantly increased the PSH unit availability for CoCs across the United States. A report by US Interagency Council on Homelessness (2021) found that in 2021 the overall PSH inventory across the nation included more than 376,000 year-round beds for homeless individuals. The expansion of PSH has contributed to a 25% decrease in number of chronically homeless individuals [

19] in the past decade between.

The New Orleans/Jefferson Parish CoC, which has been a high-performing CoC for the last five years receives significant HUD funding for its homeless services. HUD funding for the CoC has grown steadily, increasing from

$25.6 million in 2021 to

$32.9 million in 2023, with 61% allocated to PSH projects. Similarly, HUD provided over

$9 billion to Louisiana for housing recovery efforts post Hurricane Katrina in 2005, majority portion of which was managed through the CoC [

18]. Similarly, FEMA provided over

$6 billion for emergency housing, restoration and repairs [

20] in the Greater New Orleans area. As a result of this efforts by the CoC, by 2011 over 85% displaced residents of hurricane Katrina were successfully rehoused either in permanent or in temporary housings . During the year 2007 to 2019, period driven by post Katrina recovery efforts, chronic homelessness in New Orleans dropped by 85% and PSH bed utilization rate were at 99.4% indicating maximization of the housing resources [

21]. The largest portion of this improvement by the CoC was because of the HUD funding support.

Hypotheses 4 : CoC networks operating in political climates favorable to homeless services will have higher Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) bed unit availability.

The political climate, along with the policies it produces, can significantly influence the performance of collaborative networks [

13,

22]. These system contexts are recognized as significant conditions or elements affecting collaborative governance and its performance. Various studies have explored these elements in the system context influencing collaborative governance and its performance outcomes.

Bryson and Crosby (2008) explored administrative, legal, and policy conditions that affect the collaborative governance process. Ansell and Gash (2008) explored power and political dynamics within levels of government and communities and how it affects the collaborative governance process and outcomes. Solid political support for addressing homelessness may result in more funding that adequately funds the CoC programs in addressing homelessness. While, in a lesser supportive political climate, there may be limited funding which poses challenges for CoCs to meet the demands of people experiencing homelessness. The housing initiatives that the CoC takes to reduce homelessness, such as rental assistance programs, affordable housing, and supportive housing, are better supported by the political leadership and local government, which prioritize housing solutions and facilitate such initiatives by CoC [

10].

CoC may have challenges if the political climate of their area restricts the development of affordable housing or imposes zoning regulations that will seriously limit the placement of homeless shelters and supportive housing. The CoCs collaborate with the federal, state, and local governments to execute and grow homelessness services. The political climate can influence the government's willingness to engage with CoCs and to provide them with resources and institutional support. In a supportive political environment, CoCs are more likely to benefit from enhanced opportunities for coordination, resource acquisition, and cross-sector collaboration. The political climate also helps shape the public's perception of their support for effective homelessness solutions [

26].

A favorable political climate fosters public support for CoC, while an unfavorable political climate may hinder the CoC's efforts to provide services and gain public support. CoCs need to know the political climate of the region they are operating in, as it can vary and change across states, regions, communities, and jurisdictions over time. CoCs need to collaborate with policymakers in community advocacy to understand and navigate the political climate and effectively advocate for effective policies that support homelessness services. As Mosley and Park (2022) suggest, various political ideologies have different policy priorities, goals and strategy for resource allocation that favor or restrict social equality and shape governance. The political climate can have a significant effect on the network performance.

High performing CoCs are seen to benefit from political support for housing initiatives and stronger nonprofit partnerships [

18]. PSH services works more efficiently in communities where there is local support and political will to implement PSH services to tackle homelessness. Building relationships with the political leadership in the community was seen to have a significant impact in getting support for PSH projects, specifically on collaboration on finding solutions for homelessness issues and ease of implementation of those solution with least political barriers [

24].

Maintaining positive relationships with community members and political leaders help to create external environment that support PSH development and its successful implementation. In a report by Vision Action Network (2018) on limitations of PSH services in Washington county, Oregon found that restrictive housing tax policies and constrained local government fundings on PSH projects are responsible for increased homelessness and decreased ability of PSH services to cater to these homeless population as they struggle with housing instability, poverty and increased housing prices. In the democratic regions, there is often stronger advocacy for federal HUD funding and allocation and mobilization of local resources to build PSH networks. Areas with affordable housing shortages (e.g., Las Vegas CoC, Riverside CoC) and restrictive housing policies see limited PSH success whereas CoCs that has favorable housing policies fostering collaboration, for example New Orleans CoC and Miami-Dade CoC leads to higher retention and participation rates for PSH services.

The political climate therefore significantly helps shape the performance outcomes of CoCs. CoCs in regions with favorable political climate is favored by political will to invest in PSH, supportive housing policies and enhanced service coordination that is robust. CoCs in regions with unfavorable political climate, on the other hand, face challenges related to funding priorities, policy limitations, and service delivery gaps. [

24].

The research investigate this external environmental condition-political climate to see to what extent is it affecting the overall CoC performance.

Hypotheses 5 : CoC networks operating in regions with higher gross household income will have higher Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) bed unit availability.

Gross household income is the total income of all the family members before tax and any other deductions, including income from all sources each living in the household receives. Gross household income is often used in housing contexts such as housing affordability and homelessness rates and is an essential community-level determinant of homelessness [

38]. Gross household income can significantly impact the performance of CoC and the homelessness rate in the area. The level of gross household income directly affects the homelessness rates. A low level of gross household income can contribute to higher poverty levels, leading to increased homelessness for both individuals and families as they may struggle to afford housing or rental and mortgage payments which can put them at eviction or foreclosure risk. This can lead to greater homeless population with low income requiring more CoC service in these regions . The gross household income of the region where CoC operates can also impact the funding and resources for homeless services, that will impact their performance. Lower-income areas may not have significant resources, struggle to meet the homelessness reduction goals and perform poorly as they are constantly challenged compared to high-income areas [

11]. They may therefore need help to secure resources, funding, and federal support if their performance is not as expected.

Housing programs usually calculate the eligibility and affordability of individuals based on percentage of gross household income using the measure Area Median Income (AMI). An AMI of less than 30% is considered low-income. CoCs in low AMI regions may face challenges of increased CoC resource demands as they may not be able to secure affordable housing independently due to their low-income. This increases the reliance on PSH services putting pressure on CoC resources. For example- New Orleans CoC has a median household income of

$30,247 that is below the national average of

$70,000. Many residents there qualify as low-income and eligible for PSH services where CoC services surges with demand for service while the supply may not be enough to meet these demands. Similarly, the tenant contributions to the PSH programs are usually capped at 30% of income [

26] which means that for regions with lower income, the CoC has to provide larger subsidies to fill the gap between the housing costs and the tenant payments.

Hypotheses 6 : CoC networks operating in regions with higher median rent will have lower Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) bed unit availability.

Data by NLIHC (2023) suggests that a 10% rise in median rent results in a 13.6% increase in homelessness in urban areas. High rent put the vulnerable population at higher risk homelessness, increasing the demand of PSH services. The ability to find, secure and afford rent in each community also affects the CoC network performance and the length of time individuals stay and rely on the homeless services provided by the CoC. This may also affect the ability of individuals experiencing homelessness to access permanent supportive housing as there may be longer wait times for the services and, due to housing unaffordability, longer time to secure permanent supportive housing services. The median rent in an area can have a significant impact on CoC's ability to supply housing services to meet the demands of the homeless population [

26]. The median rent shows the average cost of housing units in a particular area. High median rent of a particular area means higher housing costs; this; may pose affordability challenges for the homeless population [

11], even with the CoC assistance, who have themselves face the challenges of a smaller pool of housing availability in these areas and struggle to find appropriate housing placements for people without homes which contributes to increased homelessness [

27].

In areas with high median rent, there might be shortage of supply in affordable housing units [

22]. This may create longer waitlists for CoCs and making it more challenging to find housing placements. Due to this, the CoC network in high-rent areas may not be able to meet the demand of the homeless population as effectively as the CoC network in relatively low-rent areas, which can affect the CoC network performance.

The HUD places high priority on the permanent supportive housing services where nonprofit agencies want to collaborate to provide affordable housing in high rent areas that poses significant risk of homelessness for low-income households. Due to the affordability issues in the housing market, communities have collaborated with nonprofit to tackle this problem. For example, in the San Francisco Bay Area, Alameda County collaborated with the nonprofit Base Closure Initiative to get 239 additional permanent supportive housing unit on a closed navy base [

43]. Other communities have collaborated with multiple agencies and individual donors and local government to secure funds for PSH units. For example, in the Columbus/Franklin County, the city, county, state housing funds, the United way foundation, the drug, alcohol and mental health agency and other private donors came together to leverage their resources to develop 800 PSH units for chronically homeless individuals with mental health and substance abuse problems and those with disabilities that are long-term shelter users [

43].

Similarly, some housing authorities have established priorities in their housing policies and mandates to provide PSH units for homeless people. For example, under the Rehabilitation program, Boston Housing Authority provides more than 450 units of PSH for homeless individuals. The housing authority in Columbus/Franklin County, Ohio and Rhode Island give priorities to homeless families in the PSH wait list. Similarly, Montgomery County and Maryland’s housing authority receive a significant amount of the county’s CoC funds for their permanent supportive housing unit project. Similarly, UNITY of New Orleans, the lead agency for New Orleans/Jefferson Parish CoC build their own nonprofit owned buildings and apartments for the low-income and homeless individuals to address the challenge of affordable housing. It also added 2200 new PSH units since Hurricane Katrina in 2005 [

21]. The rent of the area where the CoC operates therefore impacts its capacity to provide PSH services.

Hypotheses 7 : CoC networks operating in regions with favorable political climates toward homeless services will receive higher levels of federal funding.

High performing CoCs are seen to benefit from political support for housing initiatives and stronger nonprofit partnerships [

18]. Supportive political climate for housing policies support PSH initiatives while less supportive regions deprioritize long-term PSH initiatives with more shot-term solutions like emergency shelters and transitional housing. In regions with favorable political climate for homelessness initiatives, PSH services works more efficiently in communities where there is local support and political will to implement PSH services to tackle homelessness. Building relationships with the political leadership in the community was seen to have a significant impact in getting support for PSH projects, specifically on collaboration on finding solutions for homelessness issues and ease of implementation of those solution with least political barriers [

24].

Maintaining positive relationships with community members and political leaders help to create external environment that support PSH development and its successful implementation. In a report by Vision Action Network (2018) on limitations of PSH services in Washington county, Oregon found that restrictive housing tax policies and constrained local government fundings on PSH projects are responsible for increased homelessness and decreased ability of PSH services to cater to these homeless population as they struggle with housing instability, poverty and increased housing prices. In the democratic regions, there is often stronger advocacy for federal funding and allocation and mobilization of local resources to build PSH networks. Areas with affordable housing shortages (e.g., Las Vegas, Riverside) and restrictive housing policies see limited PSH success whereas CoCs in democratic region has favorable housing policies fostering collaboration, for example New Orleans and Miami. This leads to higher retention and participation rates for PSH services.

The political climate therefore significantly helps shape the performance outcomes of CoCs. CoCs in democratic regions are favored by political will to invest in PSH, supportive housing policies and enhanced service coordination that is robust. CoCs in republican regions, on the other hand, face challenges related to funding priorities, policy limitations, and service delivery gaps. However, it must be noted that even CoC in regions that are homelessness friendly like Chicago highlight that favorable political climates alone are insufficient without effective execution, coordination, and housing infrastructure [

43]. This comparison highlights the need for suitable strategies that consider political climates along with emphasis on networked collaboration to enhance PSH service outcomes across CoCs.

A study identifying the social, economic and political factors influencing PSH service and implementation [

28] found that there should be political will to help facilitate affordable housing opportunity specially to the low-income people that are already paying high rents and are in an increased risk of homelessness. In regions with household income of less than 30% of the total area median income and high median rent, it is even harder to find affordable housing. Having flexible regulations to increase the supply of affordable housing units such as inclusionary zoning ordinances that mandates certain percentage of units to be made affordable to low-income individual families can help create affordable housing units for PSH services as well to meet needs of low-income people that are at risk of homelessness or those experiencing homelessness. In regions struggling to meet the PSH services due to affordable housing that affects the areas with low household income and higher median rent, PSH service performance seems to be low. Regions’ socioeconomic condition is therefore a determining factor for PSH service availability and effectiveness.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework.

7. Conclusion

Public service performance, particularly when delivered through interorganizational networks, is shaped by a dynamic interplay of internal structures and external system contexts. This study provides evidence-based insights into how these conditions affect the performance of Continuum of Care (CoC) networks in the United States, federally mandated and HUD-funded systems tasked with coordinating homelessness services. Focusing on the availability of Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) units as a core performance indicator, the study identifies key factors that influence CoC effectiveness in addressing the wicked problem of homelessness.

Through regression analysis of 343 CoCs, several important patterns emerge. While the type of lead agency—government or nonprofit—was not a significant determinant of PSH availability, this finding suggests that leadership characteristics such as alignment with community values, collaborative capacity, and leadership experience may matter more than sector affiliation. Future research should explore these leadership dimensions more deeply.

Board size was found to significantly affect network performance. Larger boards enhance access to diverse resources, expertise, and sectoral representation, contributing to more robust collaborative capacity. However, the findings also highlight the need to balance inclusivity with coordination efficiency. Governance design should reflect the unique context and operational capacity of each CoC to avoid inefficiencies or conflict.

Federal funding emerged as a major driver of CoC performance. CoCs with greater HUD support had stronger PSH capacity, but the performance-based funding allocation model may inadvertently reinforce systemic disparities. Lower-performing CoCs, often under-resourced to begin with, risk becoming trapped in a cycle of low funding and limited capacity. A more equity-oriented funding mechanism that accounts for structural disadvantages could help level the playing field.

Political climate also significantly shaped PSH performance. CoCs in more progressive environments with supportive housing policies and fewer regulatory barriers tended to perform better. However, political alignment alone does not guarantee success. High-performing CoCs also exhibited strong internal capacities—such as resource innovation, transparency, community engagement, and data-driven decision-making—that allowed them to overcome external constraints.

In contrast, gross household income did not have a statistically significant relationship with PSH availability. Affluent communities may resist PSH development due to concerns about property values and neighborhood identity, revealing the need to explore local attitudes and political behavior in future studies.

Median rent was a significant barrier to PSH expansion. High-rent areas face affordability challenges that limit the development and sustainability of PSH units, even with sufficient funding. Structural support such as rent subsidies and local policy incentives are critical to support CoCs operating in these high-cost environments.

Overall, this study underscores that public service network performance is not a static outcome but the result of adaptive responses to evolving structural and environmental conditions. The findings highlight that improving performance requires more than structural adjustments, it demands intentional governance, strategic resource management, and collaborative resilience. By identifying key leverage points within the system, this research offers practical and theoretical contributions to the study of collaborative public service networks, particularly those confronting complex social issues like homelessness.