1. Introduction

The kingdom Fungi originated approximately 500 to 1000 million years ago and is one of the most extensive eukaryotic kingdoms, with approximately 1.5 to 5 million species [

1,

2]. This kingdom is composed of highly diverse organisms that exhibit a wide variety of life cycles, morphologies, and metabolisms, inhabiting almost all ecosystems and interacting in various ways with species in their environment by developing mutualistic, parasitic, and commensal relationships [

2].

It is composed of eukaryotic, heterotrophic organisms characterized by cellular structures that range from simple unicellular organisms to more complex filaments capable of forming macroscopic organisms [

3,

4]. Fungi have abilities that allow them to thrive in different environments, colonize plant and animal cells, and contribute to the nutrient cycle in both terrestrial and aquatic environments [

4].

Fungi possess a cell wall responsible for safeguarding cellular integrity to withstand the various conditions to which these organisms are subjected. Its characteristics can vary depending on the species, but it is generally enriched with polysaccharides that can vary in composition and structural organization [

5,

6]. Among the most important cell wall structural polysaccharides are chitin, β-1,3-glucans, β-1,6-glucans, and glycoproteins [

5,

7,

8].

Among these polysaccharides, glycoproteins are assembled by glycosyltransferases (GTs), which are enzymes found in animals, protists, plants, bacteria, and fungi. These play key roles in biological processes by transferring sugars to other receptor molecules, such as carbohydrates and proteins, as well as contributing to the formation of the cell wall and the glycosylation of metabolites [

9,

10].

UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGTs) are among the most studied GTs; these belong to the GT1 family and possess GT-B folds [

11]. They can transfer UDP-sugars, such as UDP-glucose, UDP-galactose, UDP-xylose, and UDP-rhamnose to their receptors, which include polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and secondary metabolites [

12,

13,

14]. Among these sugars, UDP-rhamnose has been studied to a lesser extent, despite being relevant for the cellular viability of some fungi. This is the case for genera such as

Sporothrix and

Scedosporium, where rhamnose-based glycoconjugates are structural cell wall components [

13,

14,

15]. In

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, rhamnose is part of the glucuronoxylomannan-like glycans, a heteropolysaccharide essential for its virulence [

16]. UGTs responsible for transferring UDP-rhamnose are known as rhamnosyltransferases (RHTs), and biochemical analyses revealed the existence of two UDP-rhamnose-dependent rhamnosyltransferases in

S. schenckii [

8].

Although UGT protein sequences from different species do not exhibit high identity, UGTs structures possess GT-B folds that show high conservation [

9]. The GT-B fold comprises two independent Rossman-type β/α/β domains, consisting of an N-terminal domain and a C-terminal domain, which are positioned face-to-face and connected by an interdomain cleft. These domains are responsible for recognizing and binding UDP-sugar donors with their respective acceptors [

10,

17].

In the kingdom Plantae, the presence of RHTs has been confirmed, for example in

Arabidopsis thaliana, whose cell wall contains pectin, specifically rhamnogalacturonan I (RG-I). The enzyme RRT1, belonging to the GT106 glycosyltransferase family, participates in RG-I synthesis by transferring rhamnose from UDP-β-L-rhamnose, playing a key role in the formation of the plant cell wall [

18]. In the case of the kingdom of Fungi, the available information is insufficient to detail the rhamnosyltransferases’ evolutionary history. For this reason, in this study, we conducted a bioinformatic search for potential genes encoding enzymes involved in the rhamnosylation of other molecules in the kingdom Fungi. To identify these hypothetical genes, we used hidden Markov model (HMM) profiles, identified the main motifs found in these sequences, and compared them to analyze their distribution across different taxonomic groups within the kingdom Fungi. Additionally, we performed molecular docking assays to predict the binding affinity between the potential RHTs and UDP-rhamnose and provide experimental evidence of the presence of rhamnosyltransferases in some of the identified species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hardware and Software Environment Used

All bioinformatic analyses were conducted on an HP ENVY x360 with AMD Ryzen 3 2300u 2.00 GHz, 8 GB RAM, 256 GB SSD, an external ADATA HV620S 1TB hard drive, and Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL), a compatibility layer developed by Microsoft to run Linux binaries (in ELF format) natively on Windows 10. The analyses were performed on publicly accessible servers: NCBI databases [

19], PFAM database [

20], and AlphaFold2 hosted on Google Colab [

21].

2.2. Downloading the NCBI Database

The non-redundant (NR) BLAST database was downloaded on October 9, 2023, directly from the NCBI platform. The command used for downloading was:

2.3. Construction of Hidden Markov Models of Rhamnosyltransferases and HMMER Searches

Protein sequences of rhamnosyltransferases from

Sporothrix schenckii (Genebank accession code given in brackets) SPSK_05538 (XP_016583713.1) and SPSK_01110 (XP_016584143.1) were downloaded directly from the NCBI database [

8]. Additionally, a tblastn search was conducted within the genomes of

S. brasiliensis (GCF_000820605.1),

S. globosa (GCA_001630435.1),

S. dimorphospora (GCA_021397985.1),

S. pallida (GCA_021396235.1),

S. luriei (GCA_021398005.1),

S. humícola (GCA_021396245.1),

S. mexicana (GCA_021396375.1),

S. phasma (GCA_016097075.2),

S. variecibatus (GCA_016097105.2),

S. inflata (GCA_021396225.1),

S. euskadiensis (GCA_019925375.1),

S. pseudoabietina (GCA_019925295.1),

S. curviconia (GCA_016097085.2),

S. brunneoviolacea (GCA_021396205.1),

S. cf.

nigrograna (GCA_019925305.1),

S. protearum (GCA_016097115.2), and

Niveomyces insectorum (GCA_001636815.1).

Following this, a “blastdbcmd” command was used within WSL to retrieve nucleotide sequences from the analyzed species based on accession numbers and ranges obtained from tblastn searches [

22].

blastdbcmd -db database_name -entry sequence_accession_number -range tblastn_range_obtained -out new_filename -outfmt output_format

Once amino acid sequences were obtained, multiple sequence alignment (MSA) was performed using the MAFFT algorithm (v. 7) [

23].

For the Rht1 protein (SPSK_05538, XP_016583713.1), eight sequences were discarded due to high divergence. The remaining eight sequences (S. schenckii, S. brasiliensis, S. globosa, S. mexicana, S. humícola, S. dimorphospora, S. inflata, and S. pallida) were realigned using the MAFFT algorithm, and the resulting alignment was saved in STOCKHOLM format (SPSK_05538_MAFFT.sto). Similarly, for the Rht2 protein (SPSK_01110, XP_016584143.1), eight highly divergent sequences were discarded, and the remaining eight sequences (S. schenckii, S. brasiliensis, S. globosa, S. mexicana, S. humícola, S. dimorphospora, S. inflata, and S. variecibatus) were realigned and saved in STOCKHOLM format (SPSK_01110_MAFFT.sto).

In addition to the RHTs sequences, orthologous sequences of the RmlD gene (which is involved in rhamnose biosynthesis), SPSK_06451 (XP_016591762.1), from genus Sporothrix, were also retrieved. A total of 13 sequences were obtained from the following species: S. schenckii (XP_016591762.1), S. brasiliensis (XP_040615952.1), S. globosa (LVYW01000006.1), S. luriei (WNLO01000074.1), S. dimorphospora (WOUA01000046.1), S. inflata (WNYF01000047.1), S. pallida (WNYG01000035.1), S. humicola (WNYE01000047.1), S. mexicana (WNYC01000019.1), S. euskadiensis (JADHKQ010000009.1), S. pseudoabietina (JADHKS010000001.1), S. protearum (JADMNH010000019.1), and N. insectorum (OAA58952.1). The 13 sequences were aligned using the MAFFT algorithm and saved in STOCKHOLM format (SPSK_06451_MAFFT.sto).

Subsequently, HMM profiles were generated from the MSAs of Rht1, Rht2, and RmlD using the “hmmbuild” command from locally installed HMMER (v. 3.3.2) on WSL [

24].

hmmbuild SPSK_05538.hmm SPSK_05538_MAFFT.sto

hmmbuild SPSK_01110.hmm SPSK_01110_MAFFT.sto

hmmbuild SPSK_06451.hmm SPSK_06451_MAFFT.sto

Later, searches were conducted using the HMM profiles of Rht1, Rht2, and RmlD, using the “hmmsearch” command from HMMER, against the protein database of the kingdom Fungi obtained from NCBI (fungi_prot_db.fa).

Hmmsearch SPSK_05538.hmm fungi_prot_db.fa > SPSK_05538_MAFFT.hmmsearch

Hmmsearch SPSK_01110.hmm fungi_prot_db.fa > SPSK_01110_MAFFT.hmmsearch

Hmmsearch SPSK_06451.hmm fungi_prot_db.fa > SPSK_06451_MAFFT.hmmsearch

Finally, to determine the possible domains present in the retrieved sequences, an E-value cutoff of E<1x10

-20 (1e-20) was established [

25]. These sequences were saved in a multi-sequence FASTA file format.

2.4. Distribution of Potential RHTs in the Kingdom Fungi

The distribution analysis of motifs in the putative RHTs was performed using the MEME Suite [

26]. Protein sequences obtained from the searches conducted with HMMER for Rht1 and Rht2 were employed. The “Classic mode” configuration was used with “Any number of repetitions” in the site distribution, and the goal was to identify exactly five motifs. Advanced options- maintained default conditions, adjusting only the motif size to search, with a minimum of “6” and a maximum of “20”.

To infer phylogenetic relationships of putative RHTs proteins, sequence alignments were generated using MAFFT [

23], and phylogenetic trees were constructed with PhyML 3.0 [

27] using the parameters ‘-model BIC -Starting tress BioNJ -Fast likehood-based methods aLRT SH-like’.

2.5. Analysis of Three-Dimensional Structures of Putative RHTs

The sequences previously selected in the conserved motif analysis were used. Initially, a search was conducted in the Uniprot database to obtain the files containing a predicted three-dimensional model of the proteins in ‘Protein Data Bank’ (.PDB) format [

28]. Sequences whose three-dimensional structure was not found in the Uniprot database were modeled from their amino acid sequence using Alphafold 2 [

21]. These files were subsequently analyzed using the PyMOL software [

29], which allows for visualization of the three-dimensional structures and alignment between multiple structures.

RHTs putative sequences were analyzed using the CB-Dock and PyRx [

30,

31], where interactions between ligands and proteins were analyzed. Additionally, Discovery Studio was also used for the 2D visualization of the protein–ligand docking complex structure [

32].This approach enabled the prediction of binding affinities between the putative RHTs and UDP-L-rhamnose (CID: 192751), UDP-glucose (CID: 8629), GDP-mannose (CID: 135398627), and dolichol phosphate mannose (SID: 5646075); all obtained from PubChem [

33] database in SDF file format.

Docking analyses were performed using PyRx software, where ligands were processed in Open Babel for energy minimization through charge addition and optimization with the universal force field [

34]. The binding energy values of the docked ligand-protein complexes were recorded in kcal/mol.

2.6. Site-Directed in Silico Mutagenesis

The Ligand Docker of CHARMM-GUI (

https://www.charmm-gui.org) [

35] was used to generate in silico mutants of selected putative RHTs. Default parameters were maintained in the

PDB Manipulation Options section, except for

Mutation, where the target amino acid was selected for modification. In the

Grid Generation section,

Blind Docking was selected to ensure that the search space fully encompassed the substrate-binding site. For solvation, an orthorhombic TIP3P water box was used with a padding of 10 Å around the protein, and the system was neutralized with KCl ions at a physiological concentration of 0.15 M. The docking environment was set at pH 7.0, and CHARMM36m force fields were applied for energy parameterization. UDP-L-rhamnose assessed which amino acids contributed to binding affinity after the mutation. Docking analyses were performed using the

AutoDock Vina package.

2.7. Strains and Culture Conditions

Conidia were obtained from

Aspergillus niger FGSC A732,

Madurella mycetomatis (Laveran) Brumpt (ATCC 64942),

Metarhizium anisopliae Xi-18-2,

M. brunneum EC25,

M. guizhouense HA11-2 (environmental isolate) [

36],

Trichoderma atroviride IMI 206040 (ATCC 32173),

T. harzianum T35,

T. reesei RUTC30 (ATCC 56765), and

T. virens Tv 29.8. Yeast-like cells were obtained from

S. schenckii 1099-18 (ATCC MYA 4821),

Candida albicans SC5314 (ATCC MYA-2876), and

Saccharomyces cerevisiae BY4741 (ATCC 4040002).

All strains were cultured in YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% gelatin peptone, and 3% glucose). Cultures were incubated at 28 °C with shaking at 120 rpm, except for S. schenckii and M. mycetomatis, which were incubated at 37 °C under the same shaking conditions. C. albicans and S. cerevisiae were grown for 1 day; Metarhizium, Madurella, Sporothrix, and Trichoderma species for 4 days; and A. niger for 10 days.

2.8. Analysis of Cell Wall Composition

Conidial and yeast-like cells were pelleted, washed three times with deionized water, and disrupted using a Braun homogenizer (Braun Biotech International GmbH, Melsungen, Germany), as described previously [

37,

38]. The resulting cell walls were washed by centrifuging and resuspended six times in deionized water. Further purification was performed by serial incubations with SDS, β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.5), and 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer to remove intracellular contaminants. As previously reported, samples were hydrolyzed with 2 M trifluoroacetic acid [

38].

The acid-hydrolyzed cell wall samples were analyzed by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) using a Dionex system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) under separation conditions like those previously described [

37].

2.9. Enzyme Activity

Rhamnosyltransferase activity was analyzed using the supernatant obtained from cell disruption with a Braun homogenizer. For the enzyme assays, 200 ng of α-1,6-mannobiose (Dextra Laboratories, Reading, UK) was used as the rhamnose acceptor, and 500 µM of UDP-L-rhamnose (Chemily Glycoscience, Peachtree Corners, GA, USA) as the donor substrate. Three experimental conditions were established: (i) a complete reaction containing the enzyme, the acceptor, and UDP-L-rhamnose; (ii) a no-acceptor control, in which the reaction was performed only with the enzyme and UDP-L-rhamnose; and (iii) a heat-inactivated enzyme control, in which the complete reaction mixture was subjected to thermal treatment at 50 °C for 60 minutes to inactivate the enzyme. Reactions were carried out in a final volume of 100 µL using a potassium phosphate buffer solution (50 mM, pH 7.0), preincubated at 37 °C for 2 minutes [

8]. Reaction products were analyzed by HPAEC-PAD using a Dionex system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a CarboPac PA-1 column. Separation conditions were like those previously described for the analysis of cell wall composition [

37].

3. Results

3.1. HMM Construction of RHTs and Searches with HMMER

After constructing the HMM profiles for Rht1 and Rht2, searches were performed using the fungal protein database from NCBI. A total of 302 genera were identified for Rht1 and 180 genera for Rht2.

To support the presence of a complete rhamnose biosynthetic pathway, a search for orthologs of the enzyme RmlD was conducted. RmlD is a UDP-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose-3,5-epimerase/-4-reductase responsible for the final step in UDP-L-rhamnose synthesis in

S. schenckii [

35]. Based on this, an HMM profile was constructed, identifying RmlD orthologs in 638 fungal genera. The comparison of RmlD and Rht1 revealed 263 shared genera, accounting for 87.09% of the 302 initial genera for Rht1. Likewise, 172 shared genera were found for Rht2 and RmlD, representing 95.56% of the 180 initially identified genera, suggesting a conserved rhamnose biosynthetic context.

For Rht1, 720 species were identified across 263 genera, while 438 species belonging to 172 genera were obtained for Rht2 (

Table 1). The most representative genera for both included

Fusarium,

Colletotrichum,

Aspergillus,

Trichoderma, and

Claviceps.

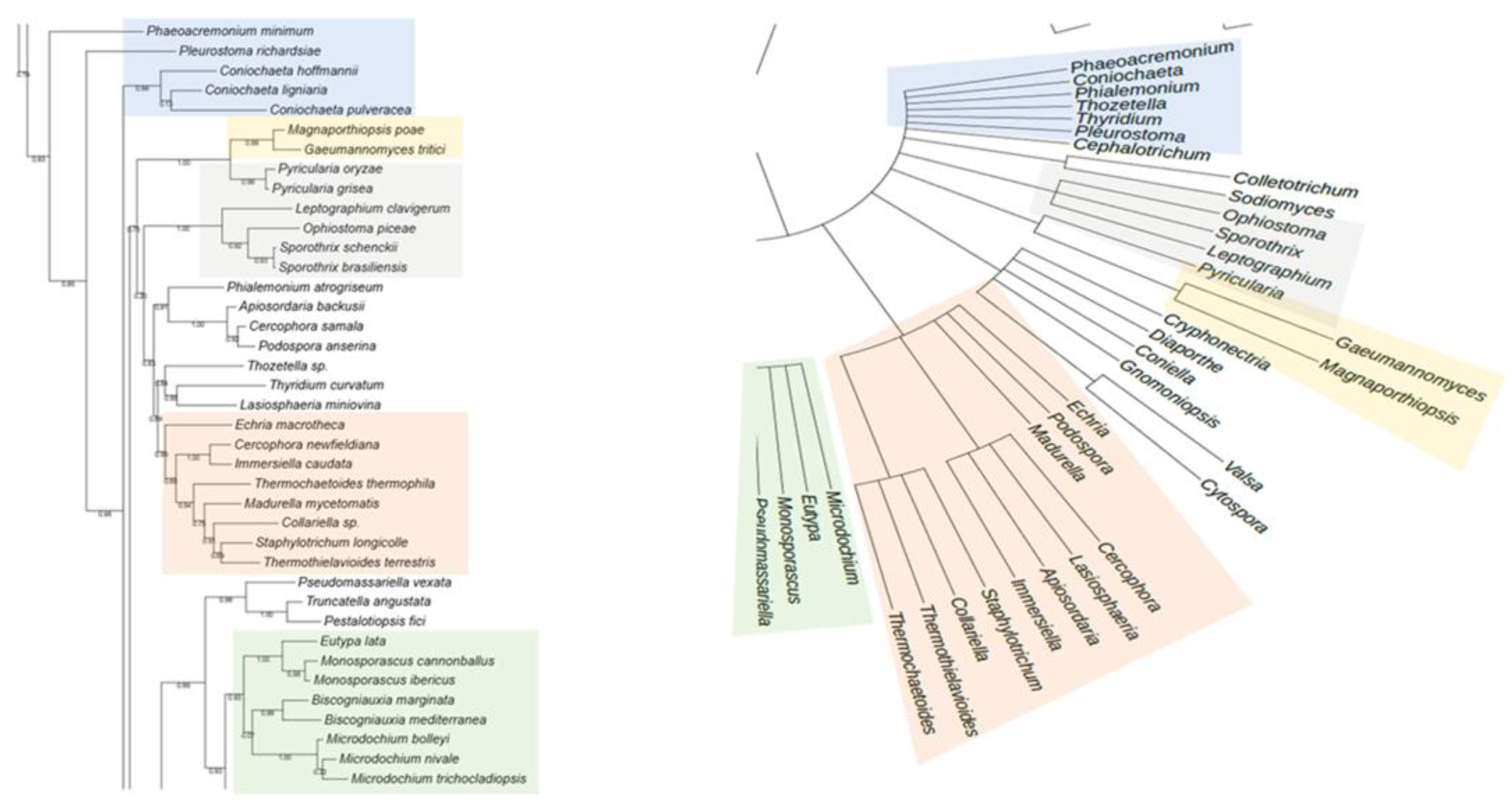

3.2. Phylogenetic Distribution of Putative RHTs

The phylogenetic analysis of the putative RHTs sequences was performed using the PhyML 3.0 platform, employing the maximum likelihood method with branch support based on the aLRT SH-like approximation. The resulting phylogenetic trees were compared to the taxonomic classification of the analyzed fungal species to identify congruent patterns that support the evolutionary relationships of the candidate RHTs. Several clades with high evolutionary relatedness were identified in both analyses and were highlighted using colored boxes to facilitate interpretation.

For Rht1, similarities were observed between the phylogeny and taxonomic classification. For instance, species of the genus

Sporothrix grouped into a clade alongside representatives of the genera

Ophiostoma and

Pycularia (Blue Box), which is consistent with previous studies indicating a phylogenetic relationship between

Sporothrix and

Ophiostoma, both members of the Ophiostomataceae family. Nearby,

Magnaporthiopsis and

Gaeumannomyces (Yellow Box) also clustered consistent with their shared membership in the order Magnaporthales. In another clade (Green Box), the genera

Eutypa,

Biscogniauxia,

Monosporascus, and

Microdochium exhibited similar distribution patterns in both trees. The placement of

Echiria,

Immersiella,

Thermothielavioides, and

Madurella within the phylogenetic tree (Orange Box) indicated that these genera generally cluster within the same clade, despite minor internal rearrangements. Additionally, the genera

Phaeoacremonium and

Coniochaeta showed consistent groupings in the phylogenetic and taxonomic trees, suggesting congruence between their genetic evolution and taxonomic classification. A comparative view of the Rht1 phylogenetic (left) and taxonomic (right) trees is presented in

Figure 1.

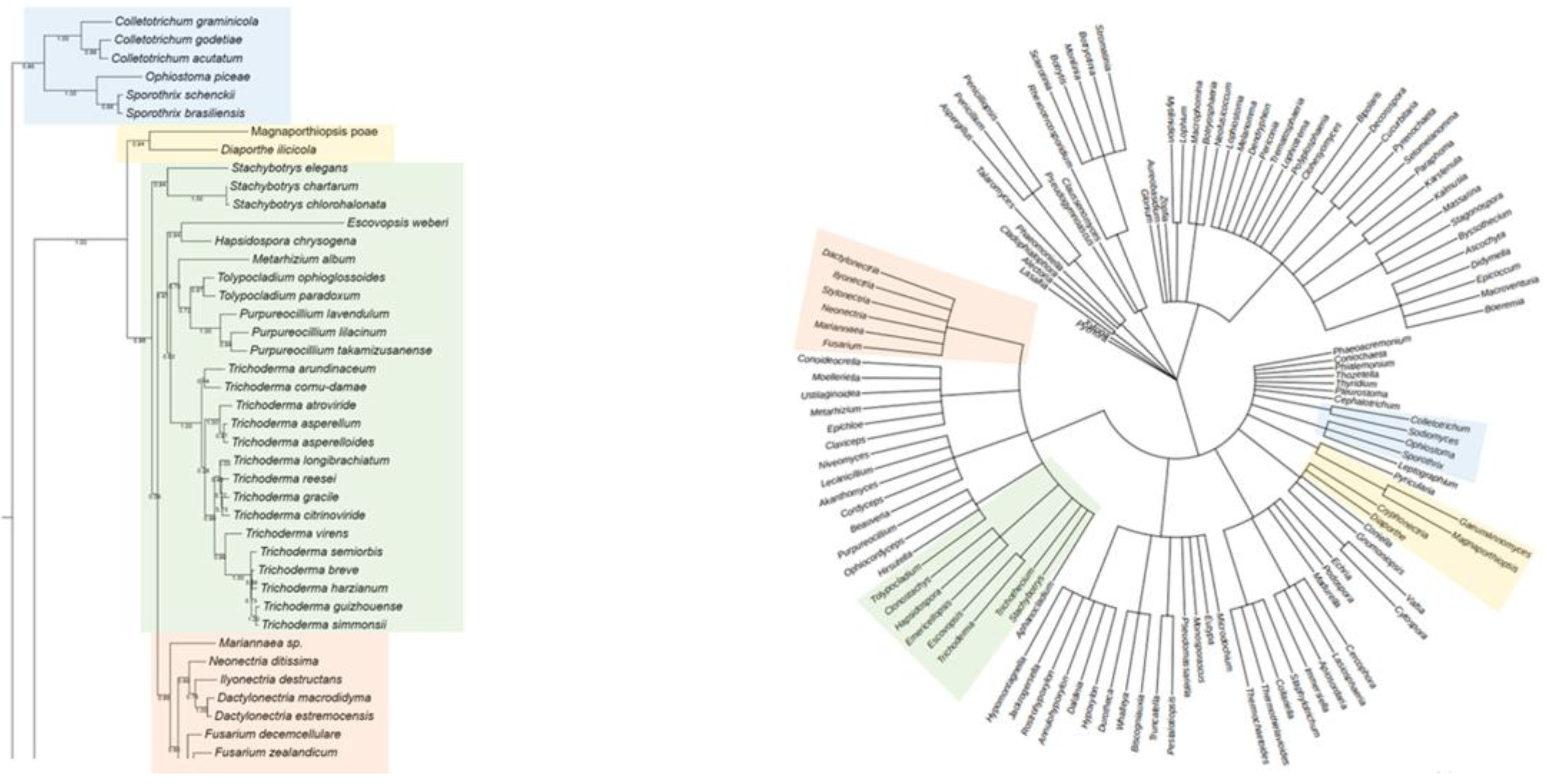

For Rht2, numerous correspondences were observed between phylogeny and taxonomy across various groups. A clear conservation was noted in the clade comprising

Sporothrix,

Ophiostoma, and

Colletotrichum (Blue Box), which clustered similarly in both trees. Likewise,

Magnaporthiopsis and

Diaporthe (Yellow Box) retained a consistent organization, in agreement with their classification within the class Sordariomycetes. In the Green Box,

Purpureocillium,

Tolypocladium, and

Trichoderma were grouped similarly in both analyses. Similarly, in the Orange Box, the genera

Neonectria,

Fusarium, and

Dactylonectria formed the same clade in both trees. Overall, the comparison of phylogenetic and taxonomic trees for Rht2 revealed a high degree of concordance, suggesting that the evolutionary history of these sequences aligns with the current taxonomic framework. A side-by-side view of the Rht2 phylogenetic (left) and taxonomic (right) trees is shown in

Figure 2.

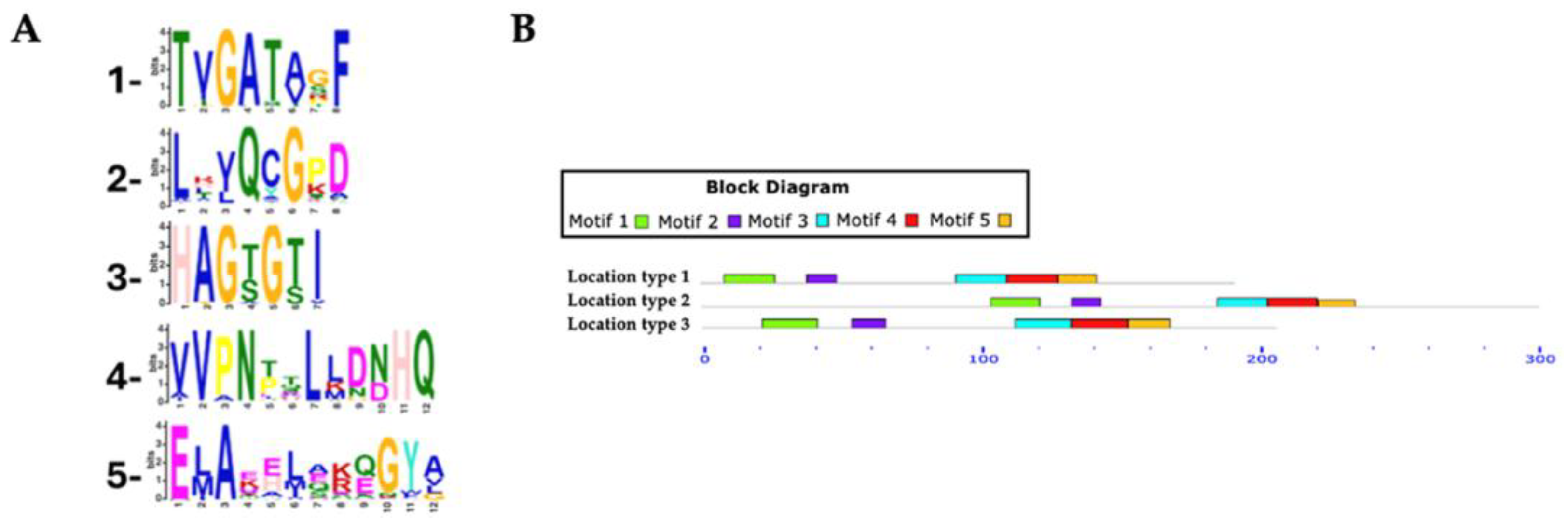

3.3. Identification and Distribution of Conserved Motifs in Putative RHTs

The identification and distribution of conserved motifs in putative RHTs were analyzed using MEME Suite, based on protein sequences obtained from HMMER searches (

Table 2). For the Rht1 motif analysis, 351 protein sequences were analyzed, with lengths ranging from 159 to 720 amino acids and an average length of 233 amino acids. Five conserved motifs were identified in putative Rht1 sequences. Motif 1, TXGATXXF (where “X” represents any amino acid), was detected in 99.4% of the sequences. Motif 2, LXXQXGXX, was found in 100%, while the motif 3, HAGXGXI, appeared in 95.4% of sequences. The motif 4, XVPNXXLXXXHQ, was also present in 100%, and the motif 5, EXAXXXXXXGYX, in 94.5%. Motif logos are shown in

Figure 3A.

Among the identified motifs, motif 1 (TXGATXXF) was the most consistently conserved across all genera analyzed, including Aspergillus, Fusarium, Colletotrichum, Claviceps, Trichoderma, and Botrytis. Motif 3 (HAGXGXI) appeared in all Fusarium (54), Claviceps (13), and Diaporthe (6) sequences, as well as in 7 of 8 Metarhizium, 14 of 15 Trichoderma, and 44 of 50 Colletotrichum species.

Most predicted motifs found to start between amino acid positions 1 to 20 (location type 1), with 311 sequences initiating in this region, representing 88.60% of the total. In contrast, fewer sequences started between positions 50 to 520 (location type 2, 7.12%), and only 15 sequences were located between positions 21 to 50 (location type 3, 4.27%).

In terms of motif conservation, some sequences lacked specific motifs: one sequence did not include motif 1, another lacked motif 3, a third lacked motif 4, and 52 sequences did not contain motif 5.

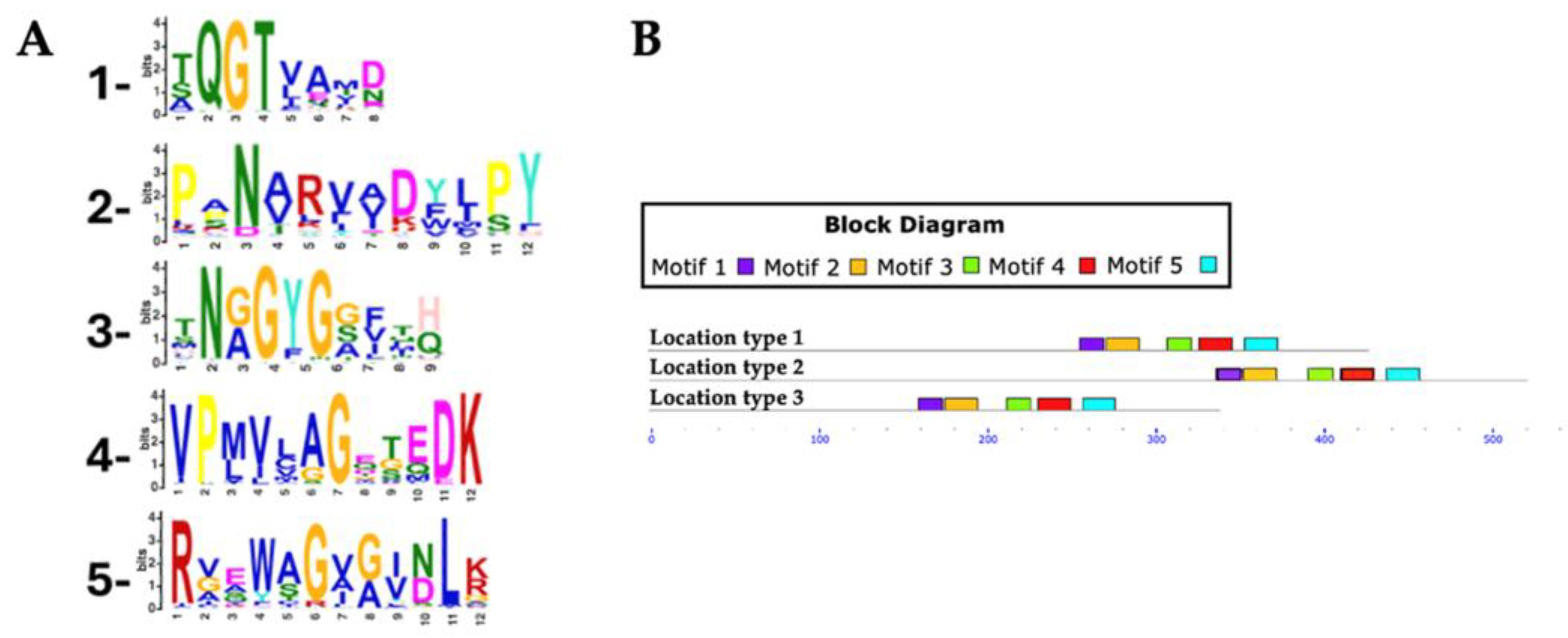

For Rht2 motif analysis, a total of 351 protein sequences were analyzed, with lengths ranging from 320 to 695 amino acids and an average length of 458 amino acids. Five conserved motifs were identified in putative Rht2 sequences. Motif 1, XQGTXXXX, was detected in 97.1% of the sequences. Motif 2, XXNXXXXXXXPY, was found in 96%, while motif 3, XNXGYGXXXX, appeared in all sequences. Motif 4, VPXXXXGXXXDK, was present in 97.7%, and motif 5, RXXXXGXXXXLX, in 92.3%. Motif logos are shown in

Figure 4A.

Among the motifs identified for Rht2, motif 1 (XQGTXXXX) was the most conserved, being present in all analyzed species of Diaporthe (6), Daldinia (8), Botrytis (10), Claviceps (13), Trichoderma (15), Fusarium (54), as well as in 7 out of 8 of Metarhizium species, 18 of 19 of Aspergillus species, and 49 of 50 of Colletotrichum species. Meanwhile, motif 3 (XNXGYGXXXX) was found in all protein sequences from Metarhizium (8), Botrytis (10), Trichoderma (15), and Fusarium (54), as well as in 12 out of 13 Claviceps species, 17 out of 19 Aspergillus species, and 46 out of 50 Colletotrichum species.

Most predicted motifs start between amino acid positions 240 to 320 (location type 1), with 333 sequences falling within this region, representing 94.87% of the total. In smaller proportions, 15 sequences were identified between positions 321 to 441 (location type 2, 4.27%), and only 3 sequences between positions 155 to 239 (location type 3, 0.85%).

Regarding the conserved motifs, several sequences were found to lack specific motifs: three sequences did not contain motif 1, two sequences lacked motif 3, another two sequences lacked motif 4, and six sequences did not present motif 5.

3.4. Structural Analysis of Predicted RHT Proteins

To explore the structural features of putative RHTs proteins, selected sequences from the conserved motif analysis were used to obtain or model 3D structures in PDB format. When unavailable in the UniProt database, 3D structures were generated using ColabFold v1.5.5: AlphaFold2. Previously reported 3D models of

S. schenckii Rht1 and Rht2 were used as structural references (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) [

8].

Rht1 of

S. schenckii displayed a typical Rossmann-like fold (β/α/β motif), consistent with GT-B glycosyltransferases. Rht2, also from

S. schenckii, showed two Rossmann folds, reinforcing its classification within the GT-B structural family. Using PyMOL, a total of 23 pairwise alignments were performed for each RHT, including species selected based on HMM results and representing both high and low sequence similarity levels. The RMSD values were used to assess structural similarity, with values <1 considered acceptable [

40,

41]. These were compared to BLAST-based identity and positive percentages (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

For Rht1, S. brasiliensis showed the highest structural similarity (RMSD = 0.14) and 98% positives, consistent with its close phylogenetic relationship to S. schenckii. Other species such as Fonseca erecta and Cordyceps militaris maintained low RMSD values (1.192 & 1.38 respectively) despite having lower positives (54–56%), indicating structural conservation beyond sequence similarity.

For Rht2, a similar trend was observed. For instance, Colletotrichum graminicola (48% identity) showed an RMSD of 0.581, suggesting a conserved fold. On the other hand, the organism with the highest RMSD value analyzed was Lophiotrema nucula, with a value of 2.101. However, it is important to note that this organism shares only 33% identity with the model Rht2.

Simultaneously, the Rht1 and Rht2 proteins were analyzed using the CB-Dock tool to investigate their potential interactions with UDP-L-rhamnose.

Figure 7A displays the docking results for Rht1 from

S. schenckii, revealing high-affinity predictions.

Notably, residues near motif 3, HAGSGSI, exhibited a binding interaction between UDP-L-rhamnose and the amino acid residues V130, R131, and D133. Additionally, residues Y192, Q193, F197, P198, T199, E203, R204, and S205 also showed interactions with the molecule (

Figure 7B).

For Rht2 (

Figure 8A), the sugar-binding sites included amino acids G321, T322, and I323, corresponding to motif 1 TXGTIA. Additionally, residues N422, G424, Y425, N426, G427, and A430 showed similarity to motif 3 TNAGYNGVXA. Finally, the residues E445, D446, and K447 matched the last four amino acids of motif 4 VPXXXXGXXXDK. Additional interactions with the molecule were observed for residues Y10, A11, G12, H13, N15, P16, I135, P238 F406 and H409 (

Figure 8B).

3.5. Molecular Docking Analysis of Putative RHTs

Putative Rht1 and Rht2 proteins identified previously were analyzed using Vina Wizard (PyRx–Python Prescription 0.8) to evaluate their affinity for different sugar donors: UDP-L-rhamnose, UDP-glucose, GDP-mannose, and Dolichol-phosphate-mannose (Dol-P-mannose). This approach aimed to confirm the specificity of rhamnosyltransferases for UDP-L-rhamnose. Binding affinity, expressed as binding free energy (kcal/mol), was used to assess interaction strength—more negative values indicating stronger affinity [

31]. For

S. schenckii Rht1, UDP-L-rhamnose (−7.6 kcal/mol) and GDP-mannose (−7.4 kcal/mol) showed the highest affinities. In contrast, UDP-glucose (−6.0 kcal/mol) and Dol-P-mannose (−6.8 kcal/mol) showed weaker binding. For Rht2, UDP-L-rhamnose (−9.8 kcal/mol) and UDP-mannose (−9.3 kcal/mol) exhibited the strongest affinities, suggesting a substrate preference for these donors. Given the lower affinities for UDP-glucose and Dol-P-mannose, these substrates were excluded from subsequent analyses to focus on those with higher biological relevance.

Table 4 and

Table 5 show the molecular docking results for putative Rht1 and Rht2 proteins across various fungal species. In general, most species exhibited a higher binding affinity for UDP-L-rhamnose compared to GDP-mannose, suggesting a preferential interaction with this sugar donor. For instance,

T. reesei showed a strong preference for UDP-L-rhamnose (−8.9 kcal/mol) over GDP-mannose (−7.9 kcal/mol) in the Rht1 analysis. A similar trend was observed among the putative Rht2 proteins, where

M. anisopliae showed the highest affinity for UDP-L-rhamnose (−9.7 kcal/mol) relative to GDP-mannose (−8.7 kcal/mol). Likewise,

M. guizhouense and

T. harzianum exhibited greater affinities for UDP-L-rhamnose (−9.3 and −9.5 kcal/mol, respectively) than for GDP-mannose (−9.0 and −8.8 kcal/mol, respectively).

3.6. In Silico Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis analyses were performed using the CHARMM-GUI platform [

35] to assess the impact of specific amino acid substitutions on the binding affinity of predicted RHTs toward UDP-L-rhamnose.

Initial docking controls with S. schenckii Rht1 showed the highest affinity for UDP-L-rhamnose (−8.7 kcal/mol), compared to UDP-glucose (−8.5 kcal/mol) and GDP-mannose (−8.3 kcal/mol), confirming substrate specificity.

Subsequent in silico substitutions in Rht1 identified Y192 as critical for substrate interaction. Its replacement with serine (Y192S) led to a notable reduction in affinity, especially for UDP-L-rhamnose (−8.3 kcal/mol), indicating a change of 0.5 kcal/mol.

This approach was extended to other putative Rht1 proteins. In Beauveria bassiana, mutation W115A reduced affinity from −9.1 to −7.9 kcal/mol, while W114A in Fusarium oxysporum caused a change of 1.1 kcal/mol (from −8.9 to −7.8 kcal/mol), reducing affinity. Conversely, Madurella mycetomatis with mutation W208A showed a minimal change (−8.2 to −8.1 kcal/mol), suggesting a limited role for this residue. In Fonsecaea pedrosoi, L121S decreased binding affinity by 0.9 kcal/mol (from −8.6 to −7.7 kcal/mol), potentially indicating a stabilizing role in ligand interaction.

Docking controls for the Rht2 protein revealed the highest binding affinity for UDP-L-rhamnose (−9.3 kcal/mol), followed by GDP-mannose (−8.9 kcal/mol) and UDP-glucose (−8.2 kcal/mol). Substitution mutations were performed, and the most significant effects were observed with the double mutation H13S/D446A in S. schenckii, which reduced the binding affinity to UDP-L-rhamnose to −8.0 kcal/mol, representing a change of 1.3 kcal/mol. A moderate reduction was also observed for GDP-mannose (−8.4 kcal/mol, change of 0.5 kcal/mol), while affinity for UDP-glucose increased to −8.9 kcal/mol (change of 0.7 kcal/mol).

Among all evaluated species, S. schenckii exhibited the greatest reduction in ligand binding mutation, suggesting that H13 and D446 play critical roles in substrate interaction. Additionally, Ophiostoma piceae and Xylona heveae showed the highest wild-type affinities (−10.0 kcal/mol), with changes of 0.8 and 0.7 kcal/mol, respectively, upon mutation. In contrast, T. reesei lacked an orthologous residue at the position corresponding to H13 in S. schenckii, so alternative residues involved in UDP-L-rhamnose binding were targeted. Mutants H302S and P221A showed minimal changes in affinity, with only a 0.1 kcal/mol change (from −8.9 to −8.8 kcal/mol), suggesting these residues are not key to substrate interaction.

In Macrophomina phaseolina, the H19S/D378A mutation resulted in a 0.5 kcal/mol reduction in binding affinity (from −9.5 to −9.0 kcal/mol), while in Magnaporthiopsis poae (H31S/D383A) the decrease was smaller (0.2 kcal/mol), indicating greater tolerance to substitutions at these positions.

These findings highlight the importance of specific residues in maintaining the stability of protein-ligand interactions and provide valuable insights for future structure-function optimization of these enzymes. Structural similarity between wild-type and mutant proteins was assessed using RMSD values to confirm that the observed affinity changes were attributable to residue substitution rather than major conformational alterations. Results are detailed in

Table 6 and

Table 7.

3.7. Cell Wall Carbohydrate Composition in Species with Putative RHTs

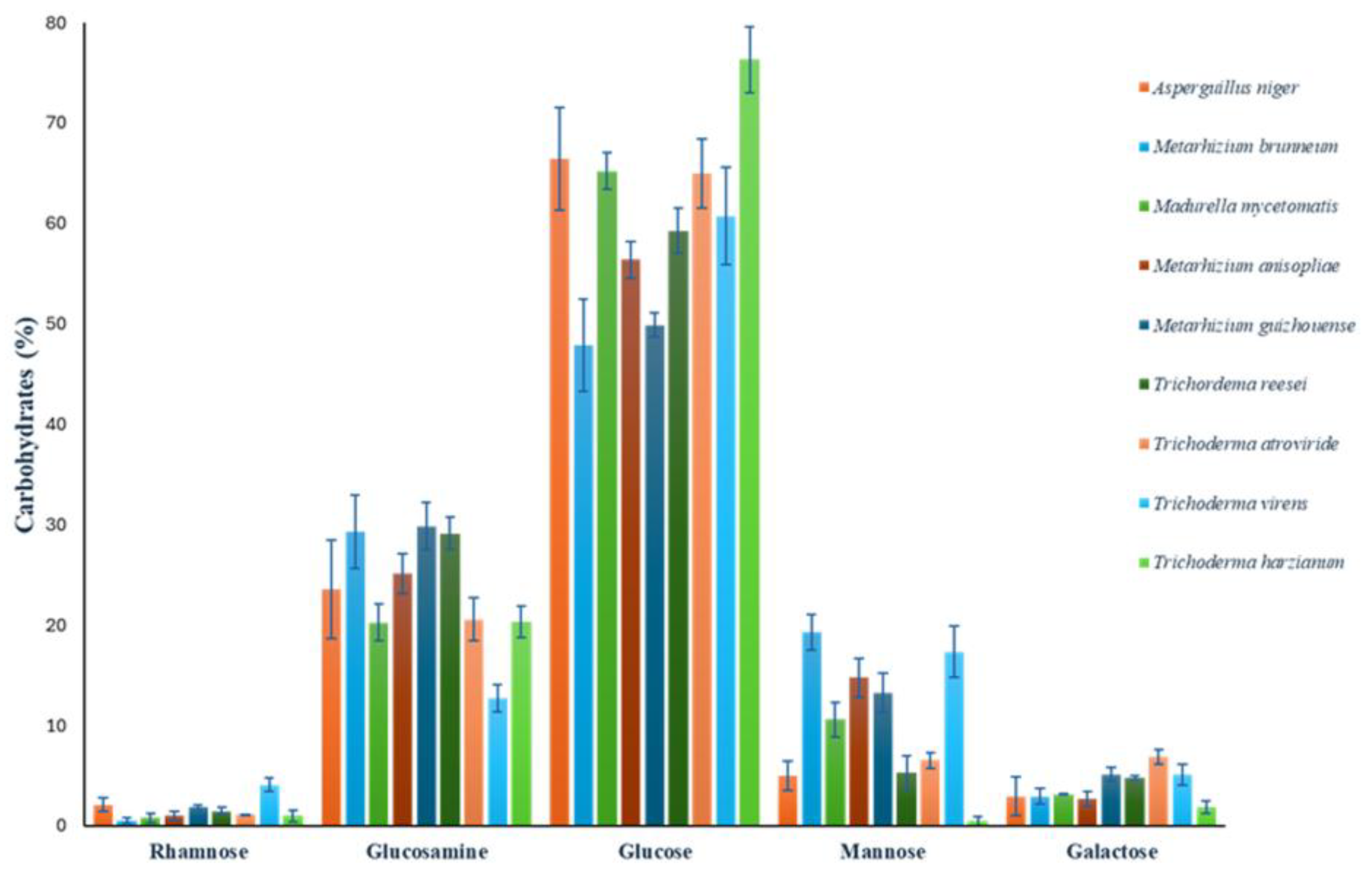

To assess the presence of rhamnose in some species with putative Rht1 and Rht2 proteins, the carbohydrate composition of the cell wall was analyzed. Quantified carbohydrates included rhamnose, glucosamine, glucose, mannose, and galactose. Values were normalized to represent relative percentages, adding to 100%.

Glucose was the predominant sugar, ranging from 47.91% to 76.33%, with

M. guizhouense showing the highest content. Mannose exhibited high variability (0.46% to 19.3%), being most abundant in

M. brunneum. Notably, rhamnose—a sugar previously unreported in most of these organisms—was detected in all analyzed species, reaching up to 4.07% in

T. virens. Full results are presented in

Figure 9.

3.8. Enzymatic Analysis of Putative RHTs

To determine whether the predicted species exhibited any RHT activity, we measured enzyme activity in cell homogenates, with α-1,6-mannobiose as the rhamnose acceptor and UDP-L-rhamnose as the donor. Reaction products were analyzed by HPAEC-PAD, and results were expressed as trisaccharide min⁻¹ per mg protein⁻¹.

The highest enzymatic activity was observed in

S. schenckii (123.63 ± 18.46 trisaccharide min⁻¹ mg protein⁻¹), consistent with prior knowledge of its ability to utilize UDP-L-rhamnose. In contrast, negative controls

Candida albicans and

Saccharomyces cerevisiae exhibited near-zero activity, confirming the absence of RHT activity in these species. Intermediate activity levels were detected in

Aspergillus niger (59.47 ± 3.91 trisaccharide min⁻¹ mg protein⁻¹),

Trichoderma virens (68.03 ± 10.31 trisaccharide min⁻¹ mg protein⁻¹), and

Trichoderma reesei (39.20 ± 7.15 trisaccharide min⁻¹ mg protein⁻¹), suggesting rhamnose transfer function in these organisms. Low activity observed in the no acceptor condition supports the enzymatic specificity, and residual values with inactivated protein confirm the association with RHT processes. Enzymatic analysis results are summarized in

Table 8.

4. Discussion

Using HMM profiles, we identified putative Rht1 and Rht2 sequences from the fungal portion of the NCBI NR database. This approach is effective for detecting distant orthologs, though its success depends on the completeness and annotation quality of genomic data [

42]. The limited representation of certain fungal groups likely reflects the under-sequencing of these taxa.

Our results revealed a broad taxonomic distribution of RHTs, especially in ecologically and biotechnologically relevant fungi. Rht1 was most frequent in

Aspergillus,

Penicillium, and

Fusarium, while Rht2 predominated in

Fusarium and

Colletotrichum. These genera are known for pathogenesis and secondary metabolite production, with some species acting as plant pathogens and others as producers of industrial enzymes or mycotoxins [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52].

The co-occurrence of Rht1 and Rht2 in 126 genera suggests complementary metabolic functions. Notably, both RHTs were found in endophytic and saprophytic fungi like

Trichoderma,

Claviceps, and

Xylaria, indicating roles beyond pathogenesis [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57].

From an evolutionary perspective, the presence of Rht1 and Rht2 in diverse taxonomic lineages suggests a functional distribution of these enzymes within the fungal kingdom, particularly in the phylum

Ascomycota. However, they appear to be absent in other phyla, such as

Basidiomycota. Previous studies analyzing members of

Basidiomycota have shown that their cell walls are primarily composed of glucose, mannose, and galactose, with occasional presence of xylose and fucose, but a consistently low or absent content of rhamnose, suggesting ecological and functional differences [

58]. These compositional differences likely reflect distinct ecological strategies: Basidiomycetes are specialized in lignocellulose degradation [

59], whereas Ascomycetes, which often colonize rhamnose-rich plant tissues, may be associated with their direct interactions with plant hosts in survival, saprophytic, mutualistic, or pathogenic contexts [

52,

60,

61,

62,

63].

The evolutionary origin of RHTs may involve vertical inheritance, horizontal gene transfer, or gene loss in certain lineages. Alternatively, these enzymes may have originated within the fungal kingdom, with Basidiomycota either losing or never utilizing rhamnose and RHTs, instead adapting their cell wall and glycoconjugate structures to other substrates typical of their environment [

64].

To explore the evolutionary history and diversification of RHTs, we compared the phylogenetic and taxonomic relationships among fungi with putative Rht1 and Rht2. In the case of Rht1, the clustering of taxonomically distant genera, such as

Pyricularia and

Sporothrix, despite their ecological differences, suggests potential structural or functional conservation of RHTs, possibly related to polysaccharide biosynthesis or host/environmental adaptation [

8,

65]. Similarly, the grouping of phytopathogens like

Magnaporthiopsis and

Monosporascus may reflect convergent evolution driven by plant-associated lifestyles [

66,

67]. For Rht2, phylogenetic and taxonomic trees reveal a notable congruence in the clustering of fungal genera. Genera ranging from phytopathogens and entomopathogens to biocontrol agents highlight a potentially broad adaptive role for Rht2, possibly involving the regulation of cell wall architecture and participation in host or environmental interaction mechanisms. For instance, enzymatic activities associated with host invasion or decomposition, such as rhamnose-dependent pectin degradation in

Colletotrichum [

68], and substrate colonization traits in

Trichoderma and

Purpureocillium, may reflect conserved Rht2 functions supporting ecological adaptation [

52,

54]. In addition to these cases, other genera distributed across diverse taxonomic orders were also identified, suggesting possible retention or functional convergence of RHTs across Ascomycota lineages [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73].

These findings provide valuable insight into the evolutionary relationships among RHT-containing fungi and support the hypothesis that these enzymes share conserved sequence motifs, alongside taxon-specific variations associated with functional diversification within the fungal kingdom. The high degree of conservation observed in motifs such as TXGATXXF, LXXQXG, and HAGXGXI, in Rht1, and XQGT and XNXGYG in Rht2, suggests that these sequence elements are critical for the catalytic activity and/or substrate recognition. Despite minor variation in motif starting positions among RHTs sequences, the spacing between conserved motifs remained consistent. This variation in initial motif positions may suggest differences in the N-terminal regions of these proteins, potentially due to divergence in sequence length or domain architecture across species. Such conservation in inter-motif distances may reflect evolutionary constraints that maintain the integrity of the active site and support a conserved enzymatic function across species. The absence of motif 5 (Rht1) in a larger number of sequences could indicate functional divergence or a loss of secondary features that are not essential for the primary enzymatic activity. This suggests that the catalytic region is structurally preserved across sequences, reinforcing the idea of a conserved functional domain even amid sequence diversity. Notably, these motifs showed no similarity to previously characterized canonical glycosyltransferases. While GT-A-type glycosyltransferases typically exhibit the conserved Asp-X-Asp (DXD) motif implicated in divalent cation coordination and nucleotide-sugar stabilization, this feature was not observed in the RHTs sequences examined. Although conserved motifs like DXD are common in glycosyltransferases, they are not universal nor strictly indicative of function, as motif structure and context can vary widely among families, reflecting their functional and structural diversity [

74,

75,

76].

The analysis of Rht1 and Rht2 sequences reveals substantial conservation among phylogenetically related species, suggesting functional preservation across divergent lineages. In the case of Rht1, structural alignments with more distantly related species, such as

Fusarium erecta and

Cordyceps militaris, showed moderate sequence identities (54-56%) but retained low RMSD scores. Similarly, for Rht2, the alignment between

C. graminicola and

S. schenckii yielded an RMSD of 0.581 despite low sequence identity. These results suggest that essential structural elements, particularly those involved in substrate binding or catalytic site stabilization, may be conserved even when amino acid sequences differ significantly [

75,

76,

77]. Collectively, these findings are in line with previous reports emphasizing the evolutionary plasticity of glycosyltransferase sequences alongside the conservation of structurally and functionally critical domains [

76]. The observed structural conservation among both closely related and taxonomically distant fungal species suggests that RHTs may have undergone evolutionary adaptation to diverse ecological niches while retaining their essential biological roles.

To assess the functional relevance of the observed structural similarities, molecular docking analysis was performed between the putative RHTs and UDP-L-rhamnose. In

S. schenckii, both Rht1 and Rht2 exhibited the highest affinity for UDP-L-rhamnose, consistent with previous studies reporting enzymatic interaction with this substrate [

8]. In contrast, GDP-mannose, UDP-glucose, and Dol-P-mannose showed lower binding affinities, suggesting fewer stable interactions and limited functional relevance. Most putative Rht1 and Rht2 proteins exhibited a consistent preference for UDP-L-rhamnose over GDP-mannose, indicating the specificity of these RHTs for UDP-L-rhamnose as a substrate. Moreover, the co-localization of predicted motifs with substrate-binding sites supports the potential role of these proteins as functional RHTs.

In silico site-directed mutagenesis was conducted to explore structural determinants of substrate specificity in putative RHTs. Targeted amino acid substitutions in Rht1, such as Y192S in S. schenckii and W115A in B. bassiana, led to measurable reductions in binding affinity to UDP-L-rhamnose, highlighting the functional importance of these residues. In Rht2, mutations H13S and D446A induced an even greater loss of affinity, suggesting that these residues are particularly critical for substrate stabilization.

Interestingly, the affected residues in fungal RHTs correspond to key catalytic residues previously identified in plant RHTs. For example, H22 and D121 in UGT71G1 (

Medicago truncatula), H20 and D119 in VvGT1 (

Vitis vinifera), and H21 and S124 in UGT89C1 (

A. thaliana) are known to be part of the catalytic site that directly interacts with the UDP -L-rhamnose [

78,

79]. Similarly, in MrUGT78R1 from

Morella rubra, mutations at D406 completely abolished RHT activity [

80].

The parallels between the plant and fungal enzymes suggest that the catalytic core of RHTs is evolutionarily conserved, with histidine and aspartate residues playing central roles in substrate coordination and catalysis. Supporting this, cell wall composition analysis confirmed the presence of rhamnose in the studied fungal species, despite its prior unreported detection in most of them.

Glucose was identified as the main component of the fungal cell wall, consistent with its well-established structural role in fungi [

81]. Mannose content showed high variability among species (0.46%–19.3%), with the highest levels observed in

M. brunneum. Mannose is typically associated with glycoproteins and mannans involved in cell adhesion and environmental interactions [

82].

Rhamnose was detected in all species analyzed. The presence of this sugar in the cell walls of fungal species identified as potential RHTs carriers supports the proposition that these enzymes may be actively involved in rhamnosylation processes. However, this finding also raises new questions regarding the specific role of rhamnose in the structure and dynamics of the fungal cell wall, as well as the identity of the polysaccharides in which it may be incorporated. Beyond the species analyzed in this study, rhamnose has also been reported in other fungal genera, such as

Rhynchosporium secalis,

Penicillium chrysogenum, and in the spore mucilage of

C. graminicola, which contains glycoproteins with rhamnose [

52,

83,

84]. Additionally, functional genes involved in UDP-L-rhamnose biosynthesis, such as UG4,6-Dh and U4k6dG-ER, have been identified in

Magnaporthe grisea and

B. cinerea [

85].

These findings support the idea that rhamnosylation is a conserved process in fungal lineages, potentially mediated by the putative RHTs identified in this study. Differences in other sugar components further highlight species-specific variations in cell wall architecture and functionality.

The detection of rhamnose in the cell walls of all analyzed species, along with the observed rhamnose transfer activity using UDP-L-rhamnose as donor and α-1,6-mannobiose as acceptor, provides functional evidence for the role of these enzymes. Notably,

S. schenckii exhibited the highest transfer rate, consistent with previously reported use of UDP-L-rhamnose [

8], while other species such as

A. niger,

T. virens, and

T. reesei showed intermediate RHT activity levels, suggesting the presence of functional RHTs with varying degrees of activity.

In contrast, the absence of RHT activity in

C. albicans and

S. cerevisiae, both of which lack rhamnose in their cell walls [

86], reinforces the specificity of the enzymatic process and suggests that rhamnose incorporation is restricted to certain fungal lineages. Together, cell wall composition and enzymatic activity analyses support a model in which rhamnose incorporation into the fungal cell wall is mediated by RHTs. The variability in activity levels suggests potential differences in enzyme regulation or precursor availability across species.

Figure 1.

Comparison between the phylogenetic distribution of Rht1 (left) and the corresponding taxonomic tree (right). Areas highlighted with the same color indicate similarities in the grouping of genera across both trees.

Figure 1.

Comparison between the phylogenetic distribution of Rht1 (left) and the corresponding taxonomic tree (right). Areas highlighted with the same color indicate similarities in the grouping of genera across both trees.

Figure 2.

Comparison between the phylogenetic distribution of Rht2 (left) and the corresponding taxonomic tree (right). Areas highlighted with the same color indicate similarities in the grouping of genera across both trees.

Figure 2.

Comparison between the phylogenetic distribution of Rht2 (left) and the corresponding taxonomic tree (right). Areas highlighted with the same color indicate similarities in the grouping of genera across both trees.

Figure 3.

Conserved motifs in Rht1 putative sequences. (A) Sequence logos of conserved motifs. (B) Distribution patterns of motifs in putative Rht1 sequences according to the MAST map.

Figure 3.

Conserved motifs in Rht1 putative sequences. (A) Sequence logos of conserved motifs. (B) Distribution patterns of motifs in putative Rht1 sequences according to the MAST map.

Figure 4.

Conserved motifs in Rht2 putative sequences. (A) Sequence logos of conserved motifs. (B) Distribution patterns of motifs in putative Rht2 sequences according to the MAST map.

Figure 4.

Conserved motifs in Rht2 putative sequences. (A) Sequence logos of conserved motifs. (B) Distribution patterns of motifs in putative Rht2 sequences according to the MAST map.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional structure of Rht1 from S. schenckii with predicted motifs highlighted in magenta.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional structure of Rht1 from S. schenckii with predicted motifs highlighted in magenta.

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional structure of Rht2 from S. schenckii with predicted motifs highlighted in purple.

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional structure of Rht2 from S. schenckii with predicted motifs highlighted in purple.

Figure 7.

Potential interactions of Rht1 from S. schenckii with UDP-L-rhamnose. (A) Three-dimensional visualization of the protein–ligand docking complex structure. The white box shows a close-up view of the interaction sites between the protein and the ligand. (B) Two-dimensional representation of the same docking complex, showing detailed interactions between the ligand and amino acid residues.

Figure 7.

Potential interactions of Rht1 from S. schenckii with UDP-L-rhamnose. (A) Three-dimensional visualization of the protein–ligand docking complex structure. The white box shows a close-up view of the interaction sites between the protein and the ligand. (B) Two-dimensional representation of the same docking complex, showing detailed interactions between the ligand and amino acid residues.

Figure 8.

Potential interactions of Rht2 from S. schenckii with UDP-L-rhamnose. (A) Three-dimensional visualization of the protein–ligand docking complex structure. The white box shows a close-up view of the interaction sites between the protein and the ligand. (B) Two-dimensional representation of the same docking complex, showing detailed interactions between the ligand and amino acid residues.

Figure 8.

Potential interactions of Rht2 from S. schenckii with UDP-L-rhamnose. (A) Three-dimensional visualization of the protein–ligand docking complex structure. The white box shows a close-up view of the interaction sites between the protein and the ligand. (B) Two-dimensional representation of the same docking complex, showing detailed interactions between the ligand and amino acid residues.

Figure 9.

Cell wall carbohydrate composition in species with putative RHTs. Error bars represent the mean ± SD from three biological replicates per condition.

Figure 9.

Cell wall carbohydrate composition in species with putative RHTs. Error bars represent the mean ± SD from three biological replicates per condition.

Table 1.

Genera, species, and accession numbers for putative RHTs.

Table 1.

Genera, species, and accession numbers for putative RHTs.

| Genera |

Species |

Rht1 accession |

Rht2 accession |

Genera |

Species |

Rht1 accession |

Rht2 accession |

| Akanthomyces |

Akanthomyces lecanii |

OAA77240.1 |

OAA70212.1 |

Aspergillus |

Aspergillus luchuensis |

XP_041539789.1 |

OJZ81278.1 |

| Akanthomyces muscarius |

XP_056049605.1 |

XP_056054863.1 |

Aspergillus mulundensis |

XP_026604170.1 |

XP_026604105.1 |

| Alectoria |

Alectoria fallacina |

CAF9938699.1 |

CAF9943470.1 |

Aspergillus neoniger |

XP_025476319.1 |

XP_025484262.1 |

| Alectoria sarmentosa |

CAD6567071.1 |

CAD6566374.1 |

Aspergillus niger |

EHA26758.1 |

GKZ64237.1 |

| Annulohypoxylon |

Annulohypoxylon bovei |

KAI2473205.1 |

KAI2463407.1 |

Aspergillus piperis |

XP_025512668.1 |

XP_025513870.1 |

| Annulohypoxylon moriforme |

KAI1454471.1 |

KAI1454171.1 |

Aspergillus sclerotiicarbonarius |

PYI12272.1 |

PYI02360.1 |

| Annulohypoxylon nitens |

KAI0892314.1 |

KAI0896334.1 |

Aspergillus sclerotioniger |

XP_025471984.1 |

XP_025463962.1 |

| Annulohypoxylon stygium |

KAI1446163.1 |

KAI1445084.1 |

Aspergillus tubingensis |

XP_035356720.1 |

GLB04893.1 |

| Annulohypoxylon truncatum |

XP_047856260.1 |

XP_047849137.1 |

Aspergillus versicolor |

XP_040664242.1 |

UZP48228.1 |

| Aphanocladium |

Aphanocladium album |

KAJ6785788.1 |

KAJ6789860.1 |

Aspergillus welwitschiae |

XP_026629939.1 |

XP_026624638.1 |

| Apiosordaria |

Apiosordaria backusii |

KAK0701482.1 |

KAK0718985.1 |

Aureobasidium |

Aureobasidium melanogenum |

XP_040877796.1 |

KAG9597102.1 |

| Ascochyta |

Ascochyta clinopodiicola |

KAJ4351106.1 |

KAJ4346241.1 |

Beauveria |

Beauveria bassiana |

XP_008598136.1 |

XP_008602005.1 |

| Ascochyta lentis |

KAF9700101.1 |

KAF9695519.1 |

Beauveria brongniartii |

OAA37782.1 |

OAA39919.1 |

| Ascochyta rabiei |

XP_059492683.1 |

XP_038797369.2 |

Bipolaris |

Bipolaris maydis |

XP_014081052.1 |

XP_014078238.1 |

| Aspergillus |

Aspergillus awamori |

GCB26403.1 |

GCB23152.1 |

Bipolaris oryzae |

XP_007689746.1 |

XP_007682054.1 |

| Aspergillus brasiliensis |

OJJ74616.1 |

GKZ22376.1 |

Biscogniauxia |

Biscogniauxia marginata |

KAI1502855.1 |

KAI1498195.1 |

| Aspergillus carbonarius |

OOF95088.1 |

OOG00364.1 |

Biscogniauxia mediterranea |

KAI1491791.1 |

KAI1491404.1 |

| Aspergillus carlsbadensis |

KAJ0426393.1 |

KAJ0415219.1 |

Boeremia |

Boeremia exigua |

KAJ8115054.1 |

XP_046000075.1 |

| Aspergillus costaricensis |

XP_025534806.1 |

XP_025540426.1 |

Botryosphaeria |

Botryosphaeria dothidea |

KAF4303495.1 |

KAF4305872.1 |

| Aspergillus eucalypticola |

XP_025389724.1 |

XP_025383912.1 |

Botryotinia |

Botryotinia calthae |

TEY39080.1 |

TEY37428.1 |

| Aspergillus hancockii |

KAF7593079.1 |

KAF7587272.1 |

Botryotinia convoluta |

TGO61616.1 |

TGO51629.1 |

| Aspergillus homomorphus |

XP_025547265.1 |

XP_025552456.1 |

Botryotinia globosa |

KAF7896435.1 |

KAF7901251.1 |

| Aspergillus ibericus |

XP_025575496.1 |

XP_025578007.1 |

Botryotinia narcissicola |

TGO69167.1 |

TGO56301.1 |

| Botrytis |

Botrytis aclada |

KAF7946254.1 |

KAF7956861.1 |

Claviceps |

Claviceps maximensis |

KAG6000611.1 |

KAG6002038.1 |

| Botrytis byssoidea |

XP_038729320.1 |

XP_038733006.1 |

Claviceps monticola |

KAG5947883.1 |

KAG5944898.1 |

| Botrytis cinerea |

XP_001557717.1 |

EMR81961.1 |

Claviceps purpurea |

KAG6139429.1 |

KAG6132685.1 |

| Botrytis deweyae |

XP_038812155.1 |

XP_038811764.1 |

Claviceps pusilla |

KAG6000469.1 |

KAG5989301.1 |

| Botrytis fragariae |

XP_037188780.1 |

XP_037193260.1 |

Claviceps sorghi |

KAG5929518.1 |

KAG5949601.1 |

| Botrytis galanthina |

THV55011.1 |

THV45154.1 |

Claviceps spartinae |

KAG5989744.1 |

KAG5994791.1 |

| Botrytis paeoniae |

TGO28479.1 |

TGO20471.1 |

Clohesyomyces |

Clohesyomyces aquaticus |

ORX91671.1 |

ORY16921.1 |

| Botrytis porri |

XP_038770654.1 |

XP_038768623.1 |

Clonostachys |

Clonostachys byssicola |

CAG9999494.1 |

CAG9995431.1 |

| Botrytis sinoallii |

XP_038758083.1 |

XP_038760845.1 |

Clonostachys chloroleuca |

CAI6100125.1 |

CAI6093753.1 |

| Botrytis tulipae |

TGO11019.1 |

TGO09160.1 |

Clonostachys rhizophaga |

CAH0016028.1 |

CAH0019948.1 |

| Byssothecium |

Byssothecium circinans |

KAF1950910.1 |

KAF1948264.1 |

Clonostachys rosea |

CAG9943511.1 |

CAG9952845.1 |

| Cephalotrichum |

Cephalotrichum gorgonifer |

SPN99558.1 |

SPO03607.1 |

Clonostachys solani |

CAH0053102.1 |

CAH0038538.1 |

| Cercophora |

Cercophora newfieldiana |

KAK0644497.1 |

KAK0638609.1 |

Collariella |

Collariella sp. |

KAJ4302561.1 |

KAJ4286560.1 |

| Cercophora samala |

KAK0666350.1 |

KAK0667676.1 |

Colletotrichum |

Colletotrichum abscissum |

KAI3548229.1 |

KAI3530008.1 |

| Cladophialophora |

Cladophialophora carrionii |

XP_008726825.1 |

XP_008725802.1 |

Colletotrichum acutatum |

KAK1728796.1 |

KAK1724125.1 |

| Cladophialophora chaetospira |

KAJ9603522.1 |

KAJ9615145.1 |

Colletotrichum aenigma |

XP_037173265.1 |

XP_037184972.1 |

| Claussenomyces |

Claussenomyces sp. |

KAI9740875.1 |

KAI9732059.1 |

Colletotrichum asianum |

KAF0316491.1 |

KAF0316378.1 |

| Claviceps |

Claviceps africana |

KAG5920846.1 |

KAG5919883.1 |

Colletotrichum camelliae |

KAH0426174.1 |

KAH0442418.1 |

| Claviceps arundinis |

KAG5952815.1 |

KAG5966788.1 |

Colletotrichum caudatum |

KAK2056574.1 |

KAK2059483.1 |

| Claviceps capensis |

KAG5921672.1 |

KAG5921632.1 |

Colletotrichum cereale |

KAK1983501.1 |

KAK1986054.1 |

| Claviceps cyperi |

KAG5952799.1 |

KAG5965626.1 |

Colletotrichum chlorophyti |

OLN82217.1 |

OLN96240.1 |

| Claviceps digitariae |

KAG5972007.1 |

KAG5982393.1 |

Colletotrichum chrysophilum |

KAK1850901.1 |

XP_053034241.1 |

| Claviceps humidiphila |

KAG6112056.1 |

KAG6118839.1 |

Colletotrichum eremochloae |

KAK2012662.1 |

KAK2005828.1 |

| Claviceps lovelessii |

KAG5991086.1 |

KAG5986980.1 |

Colletotrichum falcatum |

KAK1997804.1 |

KAK1994865.1 |

| Colletotrichum |

Colletotrichum filicis |

KAI3546144.1 |

KAI3528431.1 |

Colletotrichum |

Colletotrichum scovillei |

XP_035338834.1 |

XP_035327966.1 |

| Colletotrichum fioriniae |

XP_053047741.1 |

KAJ0331578.1 |

Colletotrichum shisoi |

TQN74967.1 |

TQN67810.1 |

| Colletotrichum fructicola |

KAF4889272.1 |

XP_031878303.1 |

Colletotrichum siamense |

XP_036489658.1 |

KAF4814982.1 |

| Colletotrichum gloeosporioides |

KAH9228900.1 |

KAH9225977.1 |

Colletotrichum sidae |

TEA14001.1 |

TEA21432.1 |

| Colletotrichum godetiae |

KAK1688763.1 |

KAK1657259.1 |

Colletotrichum simmondsii |

KXH39862.1 |

KXH40793.1 |

| Colletotrichum graminicola |

XP_008092350.1 |

XP_008100482.1 |

Colletotrichum sojae |

KAF6819562.1 |

KAF6806549.1 |

| Colletotrichum higginsianum |

XP_018156347.1 |

GJC91227.1 |

Colletotrichum somersetense |

KAK2040239.1 |

KAK2043394.1 |

| Colletotrichum incanum |

KZL82890.1 |

OHW97533.1 |

Colletotrichum sublineola |

KAK1967522.1 |

KDN67295.1 |

| Colletotrichum karsti |

XP_038751836.1 |

XP_038743776.1 |

Colletotrichum tamarilloi |

KAK1504719.1 |

KAK1490332.1 |

| Colletotrichum limetticola |

KAK0377708.1 |

KAK0371775.1 |

Colletotrichum tanaceti |

KAJ0168474.1 |

KAJ0162061.1 |

| Colletotrichum liriopes |

GJC85203.1 |

GJC77217.1 |

Colletotrichum tofieldiae |

GKT60742.1 |

KZL66573.1 |

| Colletotrichum lupini |

KAK1717078.1 |

KAK1705670.1 |

Colletotrichum trifolii |

TDZ55051.1 |

TDZ54034.1 |

| Colletotrichum musicola |

KAF6844777.1 |

KAF6838802.1 |

Colletotrichum tropicale |

KAJ3960067.1 |

KAJ3960792.1 |

| Colletotrichum navitas |

KAK1589649.1 |

KAK1573862.1 |

Colletotrichum truncatum |

XP_036584982.1 |

XP_036576291.1 |

| Colletotrichum noveboracense |

KAJ0291777.1 |

KAJ0277668.1 |

Colletotrichum viniferum |

KAF4928949.1 |

KAF4925869.1 |

| Colletotrichum nupharicola |

KAJ0294167.1 |

KAJ0337848.1 |

Colletotrichum zoysiae |

KAK2027693.1 |

KAK2035655.1 |

| Colletotrichum nymphaeae |

KXH63825.1 |

KXH45981.1 |

Coniella |

Coniella lustricola |

PSR99022.1 |

PSR88517.1 |

| Colletotrichum orbiculare |

TDZ14397.1 |

TDZ14673.1 |

Coniochaeta |

Coniochaeta hoffmannii |

KAJ9161119.1 |

KAJ9155879.1 |

| Colletotrichum orchidophilum |

XP_022472465.1 |

XP_022475743.1 |

Coniochaeta ligniaria |

OIW29085.1 |

OIW23813.1 |

| Colletotrichum paranaense |

KAK1543004.1 |

KAK1540822.1 |

Coniochaeta pulveracea |

RKU46626.1 |

RKU48537.1 |

| Colletotrichum phormii |

KAK1654730.1 |

KAK1635646.1 |

Conoideocrella |

Conoideocrella luteorostrata |

KAK2612324.1 |

KAK2616729.1 |

| Colletotrichum plurivorum |

KAF6839083.1 |

KAF6829629.1 |

Cordyceps |

Cordyceps fumosorosea |

XP_018701293.1 |

XP_018701796.1 |

| Colletotrichum salicis |

KXH68169.1 |

KXH39943.1 |

Cordyceps javanica |

TQV92045.1 |

TQV95450.1 |

| Cordyceps |

Cordyceps militaris |

ATY63072.1 |

XP_006674754.1 |

Durotheca |

Durotheca rogersii |

XP_051368855.1 |

XP_051373960.1 |

| Cryphonectria |

Cryphonectria parasitica |

XP_040771798.1 |

XP_040776216.1 |

Echria |

Echria macrotheca |

KAK1750845.1 |

KAK1751134.1 |

| Cucurbitaria |

Cucurbitaria berberidis |

XP_040787765.1 |

XP_040790731.1 |

Emericellopsis |

Emericellopsis atlantica |

XP_046118537.1 |

XP_046121130.1 |

| Cytospora |

Cytospora leucostoma |

ROW08189.1 |

ROW16112.1 |

Epichloe |

Epichloe festucae |

QPH04205.1 |

QPH11511.1 |

| Dactylonectria |

Dactylonectria estremocensis |

KAH7149514.1 |

KAH7159663.1 |

Epicoccum |

Epicoccum nigrum |

KAG9204943.1 |

OSS46826.1 |

| Dactylonectria macrodidyma |

KAH7148757.1 |

KAH7143671.1 |

Escovopsis |

Escovopsis weberi |

KOS20329.1 |

KOS17718.1 |

| Daldinia |

Daldinia bambusicola |

KAI1806735.1 |

KAI1805383.1 |

Eutypa |

Eutypa lata |

KAI1250716.1 |

EMR68577.1 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Daldinia caldariorum |

XP_047790272.1 |

XP_047785741.1 |

Fusarium |

Fusarium acutatum |

KAF4417706.1 |

KAF4435765.1 |

| Daldinia childiae |

XP_033434965.1 |

XP_033438607.1 |

Fusarium albosuccineum |

KAF4453631.1 |

KAF4470643.1 |

| Daldinia decipiens |

XP_049104523.1 |

XP_049095979.1 |

Fusarium ambrosium |

RSM11772.1 |

RSL97308.1 |

| Daldinia eschscholtzii |

KAI1473488.1 |

KAI1475320.1 |

Fusarium austroafricanum |

KAF4446928.1 |

KAF4445897.1 |

| Daldinia grandis |

KAI0108307.1 |

KAI0095932.1 |

Fusarium austroamericanum |

KAF5236077.1 |

KAF5233753.1 |

| Daldinia loculata |

KAI2779756.1 |

KAI2777984.1 |

Fusarium avenaceum |

KAH6968718.1 |

KIL89965.1 |

| Daldinia vernicosa |

XP_047867275.1 |

XP_047863139.1 |

Fusarium beomiforme |

KAF4344697.1 |

KAF4334837.1 |

| Decorospora |

Decorospora gaudefroyi |

KAF1831972.1 |

KAF1836052.1 |

Fusarium chuoi |

KAI1013357.1 |

KAI1019319.1 |

| Dendryphion |

Dendryphion nanum |

KAH7135752.1 |

KAH7135333.1 |

Fusarium coffeatum |

XP_031013799.1 |

XP_031011366.1 |

| Diaporthe |

Diaporthe ampelina |

KKY39506.1 |

KKY35200.1 |

Fusarium coicis |

KAF5967328.1 |

KAF5967796.1 |

| Diaporthe amygdali |

KAK2615727.1 |

XP_052998701.1 |

Fusarium culmorum |

PTD03166.1 |

PTD08619.1 |

| Diaporthe batatas |

XP_044649453.1 |

XP_044648057.1 |

Fusarium decemcellulare |

KAF5000569.1 |

KAF4990227.1 |

| Diaporthe eres |

KAI7784925.1 |

KAI7784403.1 |

Fusarium denticulatum |

KAF5669558.1 |

KAF5676768.1 |

| Diaporthe helianthi |

POS75403.1 |

POS81165.1 |

Fusarium duplospermum |

RSL50528.1 |

RSL66332.1 |

| Diaporthe ilicicola |

KAI3397926.1 |

KAI3399409.1 |

Fusarium equiseti |

CAG7560528.1 |

CAG7554771.1 |

| Didymella |

Didymella heteroderae |

KAF3044419.1 |

KAF3045961.1 |

Fusarium euwallaceae |

RTE71192.1 |

RTE70560.1 |

| Didymella pomorum |

KAJ4403697.1 |

KAJ4411464.1 |

Fusarium falciforme |

XP_053008353.1 |

KAJ4142701.1 |

| Fusarium |

Fusarium flagelliforme |

XP_045987014.1 |

XP_045981550.1 |

Fusarium |

Fusarium pseudocircinatum |

KAF5593813.1 |

KAF5606259.1 |

| Fusarium floridanum |

RSL77313.1 |

RSL81449.1 |

Fusarium pseudograminearum |

QPC77377.1 |

QPC79958.1 |

| Fusarium fujikuroi |

KLO94116.1 |

KLO93232.1 |

Fusarium redolens |

XP_046051426.1 |

XP_046045510.1 |

| Fusarium gaditjirri |

KAF4952308.1 |

KAF4947967.1 |

Fusarium sarcochroum |

KAF4970797.1 |

KAF4970128.1 |

| Fusarium graminearum |

XP_011318866.1 |

PCD36796.1 |

Fusarium solani |

XP_046134246.1 |

XP_046129193.1 |

| Fusarium graminum |

KAF4989143.1 |

KAF4992880.1 |

Fusarium solani-melongenae |

UPL01582.1 |

UPL00732.1 |

| Fusarium heterosporum |

KAF5673296.1 |

KAF5665361.1 |

Fusarium sporotrichioides |

RGP74396.1 |

RGP62770.1 |

| Fusarium irregulare |

KAJ4028622.1 |

KAJ4002951.1 |

Fusarium tjaetaba |

XP_037201359.1 |

XP_037210905.1 |

| Fusarium keratoplasticum |

XP_052913386.1 |

XP_052910685.1 |

Fusarium tricinctum |

KAH7262271.1 |

KAH7263618.1 |

| Fusarium kuroshium |

RMJ06590.1 |

RMJ08909.1 |

Fusarium vanettenii |

XP_003051169.1 |

XP_003048134.1 |

| Fusarium langsethiae |

GKU13606.1 |

KPA39552.1 |

Fusarium venenatum |

XP_025590567.1 |

KAG8361315.1 |

| Fusarium longipes |

RGP64061.1 |

RGP64175.1 |

Fusarium verticillioides |

XP_018746363.1 |

XP_018759284.1 |

| Fusarium mangiferae |

XP_041681908.1 |

XP_041689374.1 |

Fusarium xylarioides |

KAG5745984.1 |

KAG5750058.1 |

| Fusarium mundagurra |

KAF5703820.1 |

KAF5715773.1 |

Fusarium zealandicum |

KAF4977827.1 |

KAF4976478.1 |

| Fusarium musae |

XP_044681754.1 |

XP_044678177.1 |

Gaeumannomyces |

Gaeumannomyces tritici |

XP_009216301.1 |

XP_009229452.1 |

| Fusarium napiforme |

KAF5543507.1 |

KAF5530306.1 |

Glonium |

Glonium stellatum |

OCL07134.1 |

OCL02246.1 |

| Fusarium odoratissimum |

XP_031063514.1 |

XP_031068097.1 |

Gnomoniopsis |

Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi |

KAJ4396492.1 |

KAJ4397375.1 |

| Fusarium oligoseptatum |

RSM10484.1 |

RSM09688.1 |

Hapsidospora |

Hapsidospora chrysogena |

KFH41691.1 |

KFH48365.1 |

| Fusarium oxysporum |

RKK72986.1 |

KAJ4047383.1 |

Hirsutella |

Hirsutella minnesotensis |

KJZ78224.1 |

KJZ71824.1 |

| Fusarium piperis |

KAJ4307910.1 |

KAJ4328312.1 |

Hirsutella rhossiliensis |

XP_044715856.1 |

XP_044720357.1 |

| Fusarium poae |

XP_044713521.1 |

OBS22433.1 |

Hypomontagnella |

Hypomontagnella monticulosa |

KAI0386569.1 |

KAI0378476.1 |

| Fusarium proliferatum |

KAI1009795.1 |

KAG4256852.1 |

Hypomontagnella submonticulosa |

KAI2638882.1 |

KAI2620953.1 |

| Fusarium pseudoanthophilum |

KAF5579641.1 |

KAF5585516.1 |

Hypoxylon |

Hypoxylon cercidicola |

KAI1778259.1 |

KAI1774420.1 |

| Hypoxylon |

Hypoxylon crocopeplum |

KAI1380815.1 |

KAI1377137.1 |

Melanomma |

Melanomma pulvis-pyrius |

KAF2800153.1 |

KAF2786108.1 |

| Hypoxylon fragiforme |

XP_049114466.1 |

XP_049117066.1 |

Metarhizium |

Metarhizium acridum |

XP_007810202.1 |

KAG8422976.1 |

| Hypoxylon fuscum |

KAI1401401.1 |

KAI1399455.1 |

Metarhizium album |

XP_040678038.1 |

XP_040683175.1 |

| Hypoxylon rubiginosum |

KAI4863860.1 |

KAI4864951.1 |

Metarhizium anisopliae |

KJK84664.1 |

KJK80520.1 |

| Ilyonectria |

Ilyonectria destructans |

KAH7011765.1 |

KAH7002281.1 |

Metarhizium brunneum |

XP_014545532.1 |

XP_014548452.1 |

| Ilyonectria robusta |

XP_046104787.1 |

XP_046110074.1 |

Metarhizium guizhouense |

KID87172.1 |

KID92007.1 |

| Immersiella |

Immersiella caudata |

KAK0616255.1 |

KAK0624188.1 |

Metarhizium humberi |

KAH0599959.1 |

KAH0597174.1 |

| Jackrogersella |

Jackrogersella minutella |

KAI1107063.1 |

KAI1099809.1 |

Metarhizium rileyi |

OAA42134.1 |

OAA43280.1 |

| Kalmusia |

Kalmusia sp. |

KAJ4295449.1 |

KAJ4293461.1 |

Metarhizium robertsii |

XP_007819142.2 |

XP_007822448.1 |

| Karstenula |

Karstenula rhodostoma |

KAF2449100.1 |

KAF2448746.1 |

Microdochium |

Microdochium bolleyi |

KXJ90972.1 |

KXJ92914.1 |

| Lasallia |

Lasallia pustulata |

KAA6414625.1 |

KAA6413478.1 |

Microdochium nivale |

KAJ1326562.1 |

KAJ1329274.1 |

| Lasiosphaeria |

Lasiosphaeria miniovina |

KAK0733273.1 |

KAK0706185.1 |

Microdochium trichocladiopsis |

XP_046009150.1 |

XP_046013910.1 |

| Lecanicillium |

Lecanicillium saksenae |

KAJ3498506.1 |

KAJ3497866.1 |

Moelleriella |

Moelleriella libera |

OAA33830.1 |

KZZ90826.1 |

| Leptographium |

Leptographium clavigerum |

XP_014168710.1 |

XP_014175810.1 |

Monilinia |

Monilinia laxa |

KAB8300938.1 |

KAB8303359.1 |

| Lophiostoma |

Lophiostoma macrostomum |

KAF2657876.1 |

KAF2648898.1 |

Monosporascus |

Monosporascus cannonballus |

RYO83116.1 |

RYO94743.1 |

| Lophiotrema |

Lophiotrema nucula |

KAF2116133.1 |

KAF2113514.1 |

Monosporascus ibericus |

RYP07719.1 |

RYP11091.1 |

| Lophium |

Lophium mytilinum |

KAF2488524.1 |

KAF2497128.1 |

Mytilinidion |

Mytilinidion resinicola |

XP_033579010.1 |

XP_033568734.1 |

| Macrophomina |

Macrophomina phaseolina |

EKG10336.1 |

EKG11414.1 |

Neofusicoccum |

Neofusicoccum parvum |

EOD43149.1 |

EOD53031.1 |

| Macroventuria |

Macroventuria anomochaeta |

XP_033560458.1 |

XP_033560487.1 |

Neonectria |

Neonectria ditissima |

KPM46246.1 |

KPM40292.1 |

| Madurella |

Madurella mycetomatis |

KXX75366.1 |

KXX79238.1 |

Niveomyces |

Niveomyces insectorum |

AZHD01000039.1 |

OAA57048.1 |

| Magnaporthiopsis |

Magnaporthiopsis poae |

KLU92256.1 |

KLU84765.1 |

Ophiocordyceps |

Ophiocordyceps sinensis |

KAF4508004.1 |

EQK98407.1 |

| Mariannaea |

Mariannaea sp. |

KAI5462524.1 |

KAI5458596.1 |

Ophiostoma |

Ophiostoma piceae |

EPE10043.1 |

EPE10437.1 |

| Massarina |

Massarina eburnea |

KAF2642528.1 |

KAF2646682.1 |

Paraphoma |

Paraphoma chrysanthemicola |

KAH7083038.1 |

KAH7071542.1 |

| Penicilliopsis |

Penicilliopsis zonata |

XP_022583757.1 |

XP_022577075.1 |

Rhexocercosporidium |

Rhexocercosporidium sp. |

KAH7350870.1 |

KAH7346361.1 |

| Penicillium |

Penicillium alfredii |

XP_056508930.1 |

XP_056509782.1 |

Rostrohypoxylon |

Rostrohypoxylon terebratum |

KAI1092632.1 |

KAI1090772.1 |

| Penicillium bovifimosum |

XP_056523126.1 |

XP_056526610.1 |

Sclerotinia |

Sclerotinia borealis |

ESZ92680.1 |

ESZ95592.1 |

| Penicillium macrosclerotiorum |

XP_056932270.1 |

XP_056934836.1 |

Sclerotinia nivalis |

KAJ8059674.1 |

KAJ8071588.1 |

| Penicillium odoratum |

XP_057001022.1 |

XP_057000407.1 |

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum |

XP_001588350.1 |

XP_001589362.1 |

| Periconia |

Periconia macrospinosa |

PVI05090.1 |

PVH96591.1 |

Sclerotinia trifoliorum |

CAD6445273.1 |

CAD6453695.1 |

| Pestalotiopsis |

Pestalotiopsis fici |

XP_007834024.1 |

XP_007841187.1 |

Setomelanomma |

Setomelanomma holmii |

KAF2025903.1 |

KAF2023082.1 |

| Phaeoacremonium |

Phaeoacremonium minimum |

XP_007914921.1 |

XP_007916963.1 |

Sodiomyces |

Sodiomyces alkalinus |

XP_028463447.1 |

XP_028465600.1 |

| Phaeomoniella |

Phaeomoniella chlamydospora |

KKY25069.1 |

KKY20074.1 |

Sporothrix |

Sporothrix brasiliensis |

XP_040616120.1 |

XP_040617365.1 |

| Phialemonium |

Phialemonium atrogriseum |

KAK1762406.1 |

KAK1762806.1 |

Sporothrix schenckii |

XP_016583713.1 |

XP_016584143.1 |

| Pleurostoma |

Pleurostoma richardsiae |

KAJ9156358.1 |

KAJ9149742.1 |

Stachybotrys |

Stachybotrys chartarum |

KFA52060.1 |

KFA76153.1 |

| Podospora |

Podospora anserina |

XP_001903917.1 |

XP_001904848.1 |

Stachybotrys chlorohalonata |

KFA66408.1 |

KFA67805.1 |

| Polyplosphaeria |

Polyplosphaeria fusca |

KAF2739724.1 |

KAF2731913.1 |

Stachybotrys elegans |

KAH7326028.1 |

KAH7322735.1 |

| Pseudogymnoascus |

Pseudogymnoascus destructans |

XP_024324285.1 |

XP_024325152.1 |

Stagonospora |

Stagonospora sp. SRC1lsM3a |

OAL06240.1 |

OAL04400.1 |

| Pseudogymnoascus verrucosus |

XP_018130987.1 |

XP_018126712.1 |

Staphylotrichum |

Staphylotrichum longicolle |

KAG7286337.1 |

KAG7294653.1 |

| Pseudomassariella |

Pseudomassariella vexata |

XP_040716094.1 |

XP_040718474.1 |

Stromatinia |

Stromatinia cepivora |

KAF7858421.1 |

KAF7872547.1 |

| Purpureocillium |

Purpureocillium lavendulum |

KAJ6440404.1 |

KAJ6441125.1 |

Stylonectria |

Stylonectria norvegica |

KAF7554195.1 |

KAF7554329.1 |

| Purpureocillium |

Purpureocillium lilacinum |

XP_018175438.1 |

XP_018181559.1 |

Talaromyces |

Talaromyces amestolkiae |

XP_040733191.1 |

XP_040736898.1 |

| Purpureocillium takamizusanense |

XP_047844175.1 |

XP_047841106.1 |

Talaromyces atroroseus |

XP_020124160.1 |

XP_020121501.1 |

| Pycnora |

Pycnora praestabilis |

KAI9813616.1 |

KAI9822666.1 |

Thermochaetoides |

Thermochaetoides thermophila |

XP_006694985.1 |

XP_006692471.1 |

| Pyrenochaeta |

Pyrenochaeta sp. |

OAL53857.1 |

OAL46984.1 |

Thermothielavioides |

Thermothielavioides terrestris |

XP_003650890.1 |

XP_003658264.1 |

| Pyricularia |

Pyricularia grisea |

KAI6356710.1 |

KAI6379156.1 |

Thozetella |

Thozetella sp. |

KAH8887751.1 |

KAH8901217.1 |

| Pyricularia oryzae |

KAH8839881.1 |

KAI6251849.1 |

Thyridium |

Thyridium curvatum |

XP_030997551.1 |

XP_030999529.1 |

| Tolypocladium |

Tolypocladium ophioglossoides |

KND89648.1 |

KND93039.1 |

|

|

|

|

| Tolypocladium paradoxum |

POR38644.1 |

POR35566.1 |

|

|

|

|

| Trematosphaeria |

Trematosphaeria pertusa |

XP_033678715.1 |

XP_033681098.1 |

|

|

|

|

| Trichoderma |

Trichoderma arundinaceum |

RFU72470.1 |

RFU78995.1 |

|

|

|

|

| Trichoderma asperelloides |

KAH8130780.1 |

KAH8127233.1 |

|

|

|

|

| Trichoderma asperellum |

XP_024758558.1 |

UKZ86906.1 |

|

|

|

|

| Trichoderma atroviride |

XP_013943227.1 |

UKZ67550.1 |

|

|

|

|

| Trichoderma breve |

XP_056025069.1 |

XP_056030790.1 |

|

|

|

|

| Trichoderma citrinoviride |

XP_024751380.1 |

XP_024752346.1 |

|

|

|

|

| Trichoderma cornu-damae |

KAH6609697.1 |

KAH6605774.1 |

|

|

|

|

| Trichoderma gracile |

KAH0495172.1 |

KAH0492740.1 |

|

|

|

|

| Trichoderma guizhouense |

OPB40233.1 |

OPB36448.1 |

|

|

|

|

| Trichoderma harzianum |