1. Introduction

Voice behavior, which refers to the “making innovative suggestions for change and recommending modifications to standard procedures” (Van Dyne & LePine, 1998, p. 109), has gained attention from scholars and practitioners, since it works as an important key driver for group performance and workplace changes (Frese & Fay, 2001). Given the importance, a burgeoning research has demonstrated the importance of voice behavior and addressed the way employees determine whether to speak up or not (Dyne, Ang, & Botero, 2003). Indeed, in work groups, employees constantly confront the situation to decide whether to speak up (i.e., voice) or stay silent about potentially useful ideas or information, due to the challenging and threatening nature of voice behavior (Morrison, 2011). Prior studies have examined why individual group members may or may not express their ideas or concerns through examining the antecedents of voice behavior such as group members’ psychological safety (Edmondson, 1999), dispositional or attributional factors such as self-efficacy or personality (Withey & Cooper, 1989; LePine & Van Dyne, 2001), or leadership behavior (Detert & Burris, 2007).

However, the extant research has overly focused on individual-level voice and only a few studies have investigated employee voice as a collective-level phenomenon (Frazier & Bowler, 2015; Li, Liao, Tangirala, & Firth, 2017; Zheng, Liu, Liao, Qin & Ni, 2022). While investigation on individual-level voice allow to figure out whether employees speak or not, it does not necessarily lead to active communication among all group members. For instance, while some majority group members raise their voices, minority members may keep silent, which is not fruitful facilitating team innovation (De Dreu & West, 2001). In considering that practitioners encourage employee voice to enhance collective outcomes such as team productivity and team innovation (Li et al., 2017), the lack of investigation on the nature of group-level voice is rather surprising.

In a similar vein, the current voice literature has not closely looked at a question of how group-level factors related to social and relational issue affect employee voice (Milliken, Morrison, & Hewlin, 2003). As a group’s ability to transfer and absorb knowledge depends on group members’ voice within group social structures, their voice in groups can be best examined by understanding factors inherent in the social dynamics of work groups (Tangirala & Ramanujam, 2008). Indeed, the structure of the group facilitates the members’ ability to voice and it can reduce the social costs of expressing different viewpoints (Morrison, 2011). There is still a need, yet, for further on how the group members’ relationships with coworkers within the group affect group voice. For example, will group harmony serve to encourage group voice? Under what conditions will coworkers tend to believe that voice is benefiting them and under what conditions will they tend to believe otherwise? In what situations do group members believe that voice can build or undermine their social capital?

To answer the above question, we suggest that voice can be best understood from a relational perspective. Specifically, drawing on the notion of social network (Burt, 1992; 2004; Coleman, 1988; Granovetter, 1985; Scott, 2000), we posit the curvilinear relationship between group network density and group voice. In addition, the current research further sheds light on the contextual factors that predict the emergence of collective voice, particularly focusing on whether the voice pertains to potentially sensitive topics or not. In this vein, we believe that status conflict, wherein members inherently try to control status relations within a group’s social hierarchy (Bendersky & Hays, 2012), can be one of the essential factors. Although members in a group may have harmonious relationships, this does not necessarily imply that status hierarchy can be ignored altogether since sensitive issues can inevitably arise resulting from conflicts regarding status hierarchy. Indeed, the mere existence of superficial relationships can orthogonally interact with status conflict, consequently affecting group voice.

In this study, we shed light on this awkward but also quite familiar social phenomenon with adopting structural and relational perspective. First, whereas there has been a growing number of studies on factors that affect voice, there does not yet exist an overarching theoretical framework for understanding how these factors relate to one another (Morrison, 2011). Thus, this study examines how these paradoxical co-existences of a high-level of group network density and status conflict shapes group voice. In this regard, an ironic but also rampant social phenomenon may draw the scholarship’s attention that is called “the elephant in the room.” This evocative metaphor refers to a situation in which everyone is definitely aware of a certain object or matter, yet no one openly acknowledges or discusses on it. Even though group members are pervasively surrounded by this “open secret” that, although widely known, nevertheless remained unspoken (Zerubavel, 2006), prior voice research has yet fully taken into account how and when this paradoxical social phenomenon would occur.

Second, we also contribute to the development of voice literature by focusing on the group-level voice apart from individual-level voice research. Due to the fact that voice is not just the personal act but rather the public act of acknowledging (Zerubavel, 2006), it is always performed by members within particular social units. Moreover, since voice may impact not just one actor but also one’s colleagues, it tends to appear as a product of collective efforts involving multiple individuals. Compared to an individual’s speaking up, the collective voice can make itself more salient and therefore is easily to be conveyed (Frazier & Bowler, 2009).

Third, we address group voice from a sociological rather than a traditional psychological perspective. We specifically raise the question of why group members do not speak up and withhold their opinions even if they are “in the same room” (i.e., implied as a group’s network structure) while definitely noticing the problems that their group faces. In particular, by analyzing the degree of group network density, we investigate how group network structure can make it easier for members to speak up, or prevent them from expressing their different opinions. In addition, we further explore in which circumstances make group members leave it as such “uncomfortable truths”. To do this, we consider a role of status conflict and possible interaction with group network density in affecting group voice. Group network density and status conflict may seem to be incompatible, but conflict over people’s relative position in the group is inherent and unavoidable even in cohesive groups (Bendersky & Hays, 2012). We suggest that a consideration of the structural aspects of conflict extends our understanding of how conflict may affect group dynamics such as group voice.

2. Theoretical Backgrounds and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Group Voice

Employee voice refers to the discretionary extra-role behavior or verbal communication of suggestions, opinions, or concerns intended to improve group functioning (LePine & Van Dyne, 2001; Van Dyne & LePine, 1998). Recent studies have demonstrated that voice is not a personal act but a public act of acknowledging (Zerubavel, 2006). Since work groups are inherently characterized by interdependence and shared responsibility (Mesmer-Magnus & DeChurch, 2009), voice in the context of group is particularly essential because it can directly lead to improved group decisions and problem identification/resolution (LePine & Van Dyne, 1998; Morrison & Milliken, 2000). Nonetheless, there has been relatively little research for a clearer understanding on the nature of group-level voice behavior. However, group voice/silence is rather a product of collective efforts than that of an individual; like “an elephant in the room”, group members implicitly agree not to externally speak about any matters of which they are actually aware. This fundamental tension effectively portrays between the private act and the public act of acknowledging (e.g., group voice).

Group voice, which refers to the extent to which overall group members engage in voice behavior, is important because it helps groups to identify problems or respond to opportunities (LePine & Van Dyne, 1998). Indeed, group-level voice at times can be more useful than individual-level voice; while speaking up of an individual can be just ignored or be treated as outlier, when many of the group members share and raise the same opinion, their comments may be seriously taken (Frazier & Bowler, 2015; Yukl & Falbe, 1990). In addition, voice impacts not only the focal actor, but also his or her colleagues; therefore, it tends to appear as a product of collective efforts involving more than just an individual. Despite the importance, group voice research has largely ignored, in particular, the exploration of antecedents of group voice. Thus, our purpose is to extend the voice literature by demonstrating the antecedents of group voice, especially by focusing on its social and structural aspect.

2.2. The Curvilinear Relationship Between Group Network Density and Group Voice

Literature has suggested that voice behavior is influenced by factors inherent in the social dynamics of the workplace (Brinsfield, Edwards, & Greenberg, 2009; Tangirala & Ramanujam, 2008). Despite significant progress made by the recent studies in identifying important psychological and personality-based antecedents of voice behavior, studies have yet to fully elucidate the influence of social and relational factors at work on such behaviors. Fundamentally, network structures have a significant effect on the group’s ability to potentially absorb or transfer knowledge by voicing their opinions (Tangirala & Ramanujam, 2008). Moreover, since voice impacts others within a network structure, relational and social considerations play an important role in individuals’ decisions about whether to speak up or remain silent (Milliken et al., 2003). These considerations play an integral role, as voice can have both positive and negative implications toward other employees in the group. Highlighting a problem, for example, can embarrass other group members; in addition, ideas about potential changes can be a divisive factor within the work group, potentially creating additional burden work to certain coworkers (LePine & Van Dyne, 1998; Milliken et al., 2003).

Although there are a few studies (for a review, Venkataramani and Tangirala, 2010) investigating the effects of employees’ network positions on voice behaviors, these studies also have not yet fully addressed the group-level structural factors such as group density or centralization. In this study, we particularly seek to investigate the relationship between group network density and group voice. Group network density, a key structural measure of a social network, directly indicates the level of redundancy present in a group. Specifically, the network density is reflected by the number of redundant ties existing in the network (Burt, 1992).

Essentially, in order to raise their opinions, group members need to consider two key elements of enablers: the ability and willingness to “take a stand” (Staw & Boettger, 1990). In this regard, social ties play an important role in providing the members with abilities to voice because social ties enable a supportive environment, constituting social capital which facilitates voice behavior at the workplace. Therefore, as the number of social ties increases, the number of individuals to whom employees can raise their suggestions increases as well. Accordingly, the effectiveness of spreading and implementing suggestions or ideas will be amplified. In addition, social ties play an important role for enhancing psychological safety of a group, which is closely tied with the enactment of voice (Detert & Burris, 2007). Thus, with increased social ties within a group, members with high psychological safety are more willing to speak up.

Yet, social network literature has long suggested the dark side of group network density. Specifically, previous studies emphasized that both insufficient and excessive social ties will lead to decreased group performance such as group voice (Langfred, 2004; Wise, 2014). Too little group density, on the one hand, will undermine the group member’s ability to voice to each other because of the lack of accessible social ties. This will reduce the transfer of resources, opportunity, and knowledge conveyed by group voice. Even if members have a true willingness to speak up, they simply do not have access to each other due to a scarcity of interpersonal relationships. In contrast, on the other hand, too much of group network density can also reduce group members’ willingness to engage in voice behavior, due to the exceptional efforts required to maintain additional ties, causing the cost to exceed its benefits (Burt, 1992). Research has shown that in order for group members to express their opinions or concerns, they must believe that doing so will be both effective and not too costly personally (Miceli & Near, 1992). In such case, even if they have enough ability to voice, their reduced willingness to take risk will lead to reduction of their voice behaviors.

In addition, due to the fact that voice could upset interpersonal relationships or reflect negatively upon other individuals (LePine & Van Dyne, 1998), employees may decide to refrain from speaking up to avoid harming colleagues or risking a damage to social capital; an individual remaining silent about a coworker’s poor performance can be a good example. Such fears and concerns that members can potentially harm their interpersonal relationships arise when considering whether to convey information about problems, as well as to offer a suggestion for improvement (Detert & Burris, 2007; Milliken et al., 2003). In this regard, too close relationships among group members may inhibit the way of conveying information about problems or offering a suggestion for improvement because of the concerns related to losing their social relationships, such as not wanting to be viewed negatively by others, not wanting to damage a relationship, avoiding upsetting or embarrassing someone else, and fear of retaliation (Milliken et al., 2003). As a whole, these factors will reduce the willingness of group members to raise voice. Taken aforementioned arguments together, we posit that the positive effects of group network density on group voice may only exist up to the certain level of density, and beyond that higher density no longer benefits group voice and even be detrimental. That is, when it exceeds the optimal level, it decreases group voice.

Hypothesis 1.

Group network density will have an inverted U-shaped curvilinear relationship with group voice. Group voice will be highest at a moderate level of group network density.

2.3. The Role of Status Conflict in Relationship Between Group Network Density and Group Voice

Given the influences of structural characteristic (i.e., group network density) on group voice, we further examine the role of interpersonal dynamics in group to predict group voice. As individuals derive intrinsic value from social esteem (Gould, 2003; Huberman, Loch, & Önçüler, 2004), they are motivated to compete for status while trying to manipulate the social structure of status relations to their advantage (Gould, 2003). Put it differently, people’s social-structural interests may serve a crucial function, perhaps more important than their task, relationship, or procedural concerns in groups. Therefore, in this study, we focus on status conflict within a group as another important factor influencing group voice.

Status conflict can be activated when people struggle over their relative status within group’s social hierarchy (Bendersky & Hays, 2012). Since status can be regarded as a fixed social resource within a group, gaining one’s status directly results in the lowering another member’s rank in the hierarchy, a phenomenon called “zero-sum game” (Berger, Ridgeway, Fisek, & Norman, 1998; Gould, 2003). Therefore, status conflict arises within the circumstance wherein members inherently try to control status relations within a group; such structural properties of status conflict, in turn, may result in more competitive behaviors. Previous research on group decision making has revealed that competition, in comparison to cooperation, serves to lessen group information sharing (Toma & Butera, 2009). In particular, voice can be stifled by the salient hierarchy resulted in status conflict. Previous research has addressed that mere introduction of hierarchical structure into a group tends to inhibit open communication (cf. Festinger, 1950). Taken together, we hypothesize that increased competitiveness resulting from status conflict will be detrimental to group voice.

Hypothesis 2.

Status conflict will be negatively associated with group voice.

In which circumstances group members tend to believe that voice will be beneficial? LePine and Van Dyne (1998) suggested that context or situation may have an effect even more pronounced than mere antecedents of voice; situations provide both the stimuli and context which can be utilized to interpret the stimuli, thus harnessing the potential to impact behavioral responses. Similarly, individual attention shapes their judgments and behaviors (Ocasio, 2011). Likewise, employees constantly seek social cues on whether or not the present work context is favorable for speaking up and utilize these cues to alter their behaviors (Dutton, Ashford, O’Neill, Hayes, & Wierba, 1997). Thus, organizational contexts have profound impacts on the frequency with which groups members speak up.

As indicated above, status conflict is also considered as one of important contextual factors that affect group processes. Previous research considered conflict as a perceptual rather than behavioral phenomenon (Pruitt & Rubin, 1986). According to this line of research, group members may perceptually interpret contextual status conflict in terms of the way it occurs. That is, as discussed earlier about the detrimental effect of excessive group network density, members in extremely cohesive groups are more likely to consider open discussion as threatening the group’s solidarity. As a result, under the high level of status conflict, they tend to make an interpretation of the contextual stimuli as “uncomfortable or unmentionable truths” because they believe that discretionary voice under the high-status conflict can be viewed as intended behavior for a particular factional or individual benefit. This is due to the fact that voice has also been classified as a form of “challenging” extra-role behavior which aims at changing the status quo (Van Dyne, Cummings, & Parks, 1995).

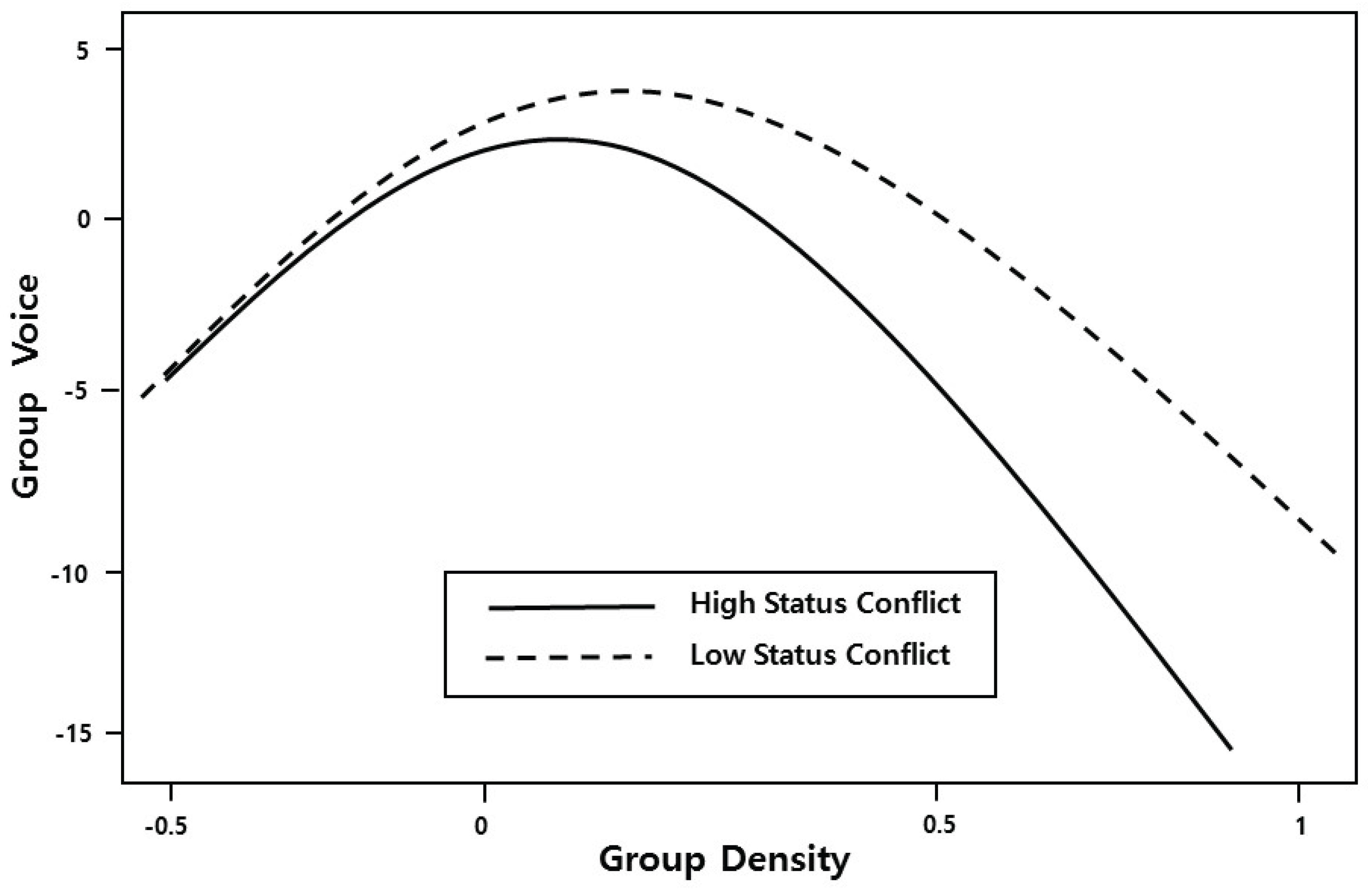

Moreover, highlighting a problem such as status conflict within a group can embarrass others or cast them in a negative light, while ideas for change can create friction within the work group or induce more work for one’s coworkers (LePine & Van Dyne, 1998; Milliken et al., 2003). Accordingly, deliberately withholding useful information often stems from concerns about being labeled as a troublemaker or complainer, or damaging already well-built social capital even if the voice was truly aimed at improving the group’s situation. Indeed, employees may worry negative repercussions or their credibility (Morrison & Milliken, 2000) by raising an issue, or even suggestion for improvement. Thus, under high status conflict, as group network density increases, group members are likely to voice, which could undermine the group’s well-established social capital. To summarize, we expect status conflict moderates the effect of group network density on group voice as follows. When status conflict is high, group network density will be more detrimental than when it is low. The peak of the inverted U-shaped relationship between group network density and group voice will be lower for groups in high status conflict situation.

Hypothesis 3.

Status conflict will moderate the inverted-U relationship of group network density and group voice, such that when status conflict is high, 1) overall level of group voice will decrease, 2) group voice will inflect (turn to decrease) faster on the downward slope of the inverted U-shaped curve.

3. Method

3.1. Research Setting and Data Collection

To test our hypotheses, we analyzed the data collected from employees in 56 work groups in three firms in South Korea via a web-based survey. The firms were organized functionally into departments, including engineering, sales, marketing, human resources, and operations. Of 341 questionnaires distributed, 282 were returned, a response rate of 83 percent. Data from one group was excluded because less than half of the team members completed the survey, consequently reducing our final sample to 55 groups. The questionnaires included measures of friendship networks among group members, status conflict, and group voice. All respondents were guaranteed confidentiality when they filled out the questionnaires. The average group size was 6.16 (s.d.= 2.93) and average group tenure was 19.48 months (s.d.= 9.38). Of all respondents, 25% were female. The age distribution of respondents indicates that the majority were in their 30s (43.6%), followed by 40s (27.7%), 20s (20.9%), and 50s (7.8%). All respondents had an undergraduate education or higher.

3.2. Measurements

Group voice We measured group voice by estimating group members’ perceptions of group-level voice, and then averaged the workgroup across the members. The items that we used are a set of 10-item of Liang, Farh, and Farh (2012). These items consist of promotive and prohibitive voice. The sample items were, “Proactively develop and make suggestions for issues that may influence the unit”, “Raise suggestions to improve the unit’s working procedure”, “Advise other colleagues against undesirable behaviors that would hamper job performance”, “Dare to voice out opinions on things that might affect efficiency in the work unit, even if that would embarrass others.” All ratings were on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very frequently). Cronbach’s alpha for the complete scale was .93.

Group network density To measure network density in group, we employed the roster method in which respondents were asked to check on an alphabetical group member list and check the members of whom they considered “personal friends.” The friendship data from each of the 55 groups were arranged in a separate matrix. Based on employees’ responses, we created a binary matrix of the friendship relations (relation = 1; no relation = 0) among the members either when they responded themselves or were chosen by others. For each of the 55 groups, we separately calculated the overall density of the friendship network between all members of that group. This measure is the proportion of ties as a function of the total number of possible ties (Wasserman & Faust, 1994). Group density ranges from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 1. The following formula was used to calculate network density:

Status conflict To assess status conflict, we used the 4-item scale from Bendersky and Hays (2012). Items are on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items included “My team members frequently took sides (i.e., formed coalitions) during conflicts,” “My team members experienced conflicts due to members trying to assert their dominance,” “My team members competed for influence,” “My team members disagreed about the relative value of members’ contributions.” Cronbach’s alpha for the complete scale was .91.

Control Variables We collected a number of control variables. First, firm dummy of the companies collected in the sample. This is important since the three companies not only differed in several structural dimensions but also in their management style. Further, these controls were considered to assure that the effect of group density and status conflict can be observed even after any effects of the company-specific factors are controlled.

In addition, following prior research, we controlled for group size by the number of members in a group (Frazier & Bowler, 2015), since group size has implications for a variety of group process that influence group outcomes (Amason & Sapienza, 1997). Group tenure were also controlled for in the analyses. Training and experience can make group members have more complete cognitive structures and useful knowledge enabling them to give opinions. We thus controlled for average group tenure (i.e., the mean length of time that group members had been worked in the group measured in months).

A final control variable was psychological safety within a group. This is a multi-item measure which is based on the employees’ self-assessments of the level of their group’s psychological safety. According to Detert and Burris (2007), enhanced feelings of psychological safety can foster voice behavior. Thus, we controlled group members’ psychological safety. Members were asked to respond a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) to indicate their assessment of the following sample items on group psychological safety from Liang et al. (2012). The sample items are “In my work unit, I can freely express my thoughts” and “Nobody in my unit will pick on me even if I have different opinions.” Cronbach’s alpha for the complete scale was .80.

3.3. Data Analyses

We used hierarchical moderated regression analysis at the group level to test our hypotheses. We entered firm dummy variables, group size, group tenure, and psychological safety in step 1, group density and the quadratic group density variable (group density squared) in step 2, status conflict in step 3 and all the independent variables together in step 4, and the interactions in the final step. We used the following regression equation to present the hypothesized relationship.

With hierarchical regression analysis, we can compare alternative models with and without interaction terms. In doing so, we can check a plain interaction effect by separately computing it from the main effects of the independent variables (Jaccard & Turrisi, 2003). The mean-centering process was implemented for the independent variables prior to the formation of interaction terms (Aiken & West, 1991).

For all models, we used several diagnostics of regression to evaluate whether our models were satisfied. First, we checked for the intra-class correlation coefficient, ICC(1) and within-group agreement index, rwg (James, Demaree, & Wolf, 1984) to calculate the appropriateness of aggregating the psychological safety, status conflict, and group voice constructs from our group-level of analysis. ICC(1) is a point estimate of inter-rater reliability in individual-level responses that can be explained by group-level in which a value greater than 0.12 is generally considered acceptable. The rwg index also justify group aggregation ranging from 0 to 1, with values greater than 0.70. To be specific, in our data, for psychological safety, the ICC(1) equaled 0.39 and the rwg equaled 0.87; for status conflict, the ICC(1) equaled 0.42 and the rwg equaled 0.85; for group voice, the ICC(1) equaled 0.32 and the rwg equaled 0.97. Thus, the interrater reliabilities and the within-group agreement in our analysis were all acceptable.

Next, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of all the variables revealed three factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.00. Among all items, three items with loading less than 0.50 were dropped, including status conflict (1 item) and psychological safety (2 items). In addition, in all cases, the three-factor model showed a superior fit to the data (all at the .001 level) resulted by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). For example, comparing a three-factor model involving psychological safety, status conflict, and group voice to a two-factor model yielded a significant change in chi-square (p= .001; CFI= .80, RMSEA= .15). Furthermore, we examined all variance inflation factor (VIF) values and found no multicollinearity concerns (where the highest value obtained in the models is 3.29).

4. Results

The correlation is reported in

Table 1, which also includes descriptive statistics for all variables in our model. Multicollinearity does not appear to be a problem, because all of the correlations among the variables are below the threshold of 0.7 which is commonly accepted.

Table 2 reports the results of the hierarchical regression analyses when group voice is the dependent variable. In model 1, we entered the control variables. We then added the group network density and the squared term of group network density in Model 2 to test for the curvilinear relationship proposed in Hypothesis 1. Results indicated that both the first-order and second-order effects of group density become significant. More specifically, the first-order effect is positive (β = .85, p < .001) and the second-order effect turns negative (β = –.77, p < .001). The increase in R-square is from .06 to .32 (F = 9.09, p < .001). All in all, Models 2 provide support for Hypothesis 1, which proposes that group density exhibits greater group voice when it is in an intermediate (rather than low or high) level of the network density.

Hypothesis 2 is tested in Model 3, where the status conflict variable introduced. In this model, the status conflict is negatively related to group voice (β = -.38, p < .05) Thus, Hypothesis 2 is also supported. We also check all the main effects of group density and status conflict together in Model 4. Finally, Hypothesis 3 is tested in Model 5, where the interaction effect between a status conflict and the curvilinear specification of group density is added. The F-test of increment in R-squared (F = 6.83, p < .01) indicates that Model 5 is superior to Model 4, such that Model 5 explains 55% of the variation in group voice, and the goodness-of-fit for the whole model is highly satisfactory (F-value of 5.365, p < .001).

Figure 1 depicts the curvilinear effect of group network density on group voice and the moderating effect of a status conflict on the above relationship.

Post-Hoc Analysis

In order to strengthen our conclusions drawn from the hypotheses test, we re-ran our regression models with dependent variables of two different types of voice behavior: promotive and prohibitive voice respectively (Liang et al., 2012). We found a significant effect of the square term of group density on each type of group voice as the same results for examining group voice in total. Further, we also regressed the models to verify the effects of status conflict and its moderating effect on our main hypothesized relationship. The results supported the conclusion that the contextual factor of status conflict also has moderating effect on group voice regardless of two types of voice. Taken together, overall proposed models in our study are proven to be robust as reported in the following

Table 3.

5. Discussion

Albeit a burgeoning literature theorizes that voice behavior is influenced by social factors inherent in the workplace, the role of group characteristics has not been fully addressed. By examining the role of structural factors on group voice, this study makes a number of contributions to the literature. First, we advance the social network theory by suggesting the role of social network characteristic (i.e., group network density) in predicting collective voice behavior at work. In this study, we hypothesized and found the curvilinear relationship between group network density and group voice behavior. Particularly, our research not only highlights a previously under-investigated group-level antecedent of voice behavior (i.e., group density), but also examines the boundary condition involved. Our findings show a curvilinear effect of group density on group voice, not a linear effect as commonly expected. That is, at an earlier phase, the group density will first have a positive effect but turn to a marginally negative effect on a group voice as it increases. Due to a combination of the cognitive costs of maintaining ties, social loafing, groupthink, and concerns for hampering social capital, high levels of group density are associated with severe disruptions to group members’ voice behavior.

Second, given the importance of voice in groups (Morrison, 2011), we further develop the literature of voice by constituting a model of collective voice, which apart from individual-level voice behavior. As indicated above, voice is rather the public act so it emerges as a form of collective efforts that involve multiple employees at work (Fraizer & Bowler, 2009; Zerubavel, 2006). By conceptualizing voice as a collective-phenomenon, we were able to theorize and examine structural and contextual antecedents of voice behavior (i.e., group network density, status conflict). The current attempt broadened the scope of antecedents of voice behavior, thus facilitating further future research to investigate the role of structural aspects of group (other than group network density) in predicting group voice.

Third, we delineate a specific situation that strengthen or weaken the effects of group network density on group voice. In this vein, we introduced the commonly accepted assumption that the social structure necessarily embodies coordination or competition relationships between alters (Burt, 2004). Specifically, we suggested and found that status conflict as an important boundary condition, and the relation between group density and voice is moderated when people are exposed to status conflict as a trigger of competitive circumstance. The current research adopted a relational approach to elaborate the role of status conflict, thus providing a more comprehensive understanding of the association between group network density and group voice.

As Paul Krugman stated that, “open secrets constitute uncomfortable truths hidden in plain sight”, such combined behavior of noticing and ignoring (i.e., withholding voice) are social phenomena involving more than just individuals. Accordingly, we sought to understand how structural aspect of group network (i.e., density) within a group influence collective voice behavior and investigated the relational boundary condition (i.e., social status) that may change the implications of key network characteristics. Most importantly, we found the side effect of excessive close, cohesive relationship among group members; in other words, too much of dense network in a group rather decreases group voice. Accordingly, groups need to be aware the fact that the mere presence of inter-connections of members is not always something that leads to the group voice. Therefore, as to relationships within groups, not only quantitative, but also qualitative aspect of the relationship will be the key factor that determines group voice.

Limitations and Future Research

Some of the limitations of this research need to be acknowledged, and they also raise a number of questions for future research. First, due to our cross-sectional data, reverse causality in our model cannot be ruled out. For example, groups whose members are very proactive to speak up may have more social ties. Nonetheless, our arguments posit in the opposite direction because plentiful research evidences that voice is a malleable behavior that is influenced by contextual and social-structural factors (Milliken et al., 2003; Morrison, 2011). Additional research adopting longitudinal design is needed to verify the direction of causality.

Second, since we test our framework in all firms in South Korea, our findings could not be generalizable in other cultural backgrounds. Indeed, the effect of network structures on employees’ behavior may vary across individualistic or collectivistic culture. Especially, social loafing effect, which resulted from excessively close network, is more likely to be found in collectivistic culture such as Asian countries, in contrast to individualistic culture such as the United States and Western European countries (Comer, 1995). Individual group members within collectivistic culture may lose their motivation due to misappropriate estimation and mismatching efforts (Yang, Zhou, & Zhang, 2015). Thus, such group members may be more likely to withhold their opinions regarding challenging ideas (Kidwell & Bennett, 1993) and less likely to initiate new ideas as a result of excessive group rigidity (Yang et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the interaction effect of group density and voice seem to be culture-free because people in general tend to be affected by their embedded social structure with regard to the power relations or status rather than just cultural context. Thus, we encourage future research to test whether our findings are replicable across diverse cultural contexts.

In spite of these limitations, our study is important for future studies to recognize that the key role of network characteristics in influencing group voice and to highlight the importance of structural, relational context factors in voice research. Specifically, we theoretically and empirically expanded the framework for understanding how the structural factors that foster or inhibit group voice relate to one another through an examination of the effects of paradoxical co-existences of group network density and status conflict.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

References

- Aiken, L.; West, S. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Amason, A.C.; Sapienza, H.J. The effects of top management team size and interaction norms on cognitive and affective conflict. Journal of Management 1997, 23, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendersky, C.; Hays, N.A. Status conflict in groups. Organization Science 2012, 23, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Ridgeway, C.L.; Fisek, M.H.; Norman, R.Z. The legitimation and delegitimation of power and prestige orders. American Sociological Review 1998, 63, 379–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinsfield, C.T.; Edwards, M.S.; Greenberg, J. (2009). Voice and silence in organizations: Historical review and current conceptualizations. Bingley, UK: Emerald.

- Burt, R.S. (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition. H: MA.

- Burt, R.S. Structural holes and good ideas. American Journal of Sociology 2004, 110, 349–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comer, D.R. A model of social loafing in real work groups. Human Relations 1995, 48, 647–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.; West, M.A. Minority dissent and team innovation: the importance of participation in decision making. Journal of applied Psychology 2001, 86, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, J.R.; Burris, E.R. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 2007, 50, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Ashford, S.J.; O’neill, R.M.; Hayes, E.; Wierba, E.E. Reading the wind: How middle managers assess the context for selling issues to top managers. Strategic Management Journal 1997, 18, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyne, L.V.; Ang, S.; Botero, I.C. Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies 2003, 40, 1359–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L.; Schachter, S.; Back, K. (1950). Social pressures in informal groups; a study of human factors in housing. H: England.

- Frazier, M.L.; Bowler, W.M. (2009). Voice climate in organizations: A group-level examination of antecedents and performance outcomes. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Management Chicago, IL.

- Frazier, M.L.; Bowler, W.M. Voice climate, supervisor undermining, and work outcomes: A group-level examination. Journal of Management 2015, 41, 841–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, M. ; Fay. D. (2001). Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. B. M. Staw, R.M. Sutton, eds. Research in Organizational Behavior.

- Granovetter, M. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R.V. 2003. Collision of Wills: How Ambiguity About Social Rank Breeds Conflict. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Huberman, B.A.; Loch, C.H.; Önçüler, A. Status as a valued resource. Social Psychology Quarterly 2004, 67, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, J.; Turrisi, R. (2003). Interaction effects in multiple regression.

- James, L.R.; R. G. Demaree, G. Wolf. Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. Journal of Applied Psychology 1984, 69, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidwell, R.E.; Bennett, N. ; Jr. 1993. Employee propensity to withhold effort: A conceptual model to intersect three avenues of research. Academy of Management Review.

- Langfred, C.W. Too much of a good thing? Negative effects of high trust and individual autonomy in self-managing teams. Academy of Management Journal 2004, 47, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Van Dyne, L. Predicting voice behavior in work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology 1998, 83, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Van Dyne, L. Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with Big Five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. Journal of Applied Psychology 2001, 86, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.N.; Liao, H.; Tangirala, S.; Firth, B.M. The content of the message matters: The differential effects of promotive and prohibitive team voice on team productivity and safety performance gains. Journal of Applied Psychology 2017, 102, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Farh, C.I.; Farh, J.L. Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal 2012, 55, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J.R.; DeChurch, L.A. Information sharing and team performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 2009, 94, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miceli, M.P. and Near, J.P. (1992). Blowing the Whistle: The Organizational and Legal Implications for Com- panies and Employees. New York: Lexington Books.

- Milliken, F.J.; Morrison, E.W.; Hewlin, P.F. An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. Journal of Management Studies 2003, 40, 1453–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W. Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals 2011, 5, 373–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W.; Milliken, F.J. Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review 2000, 25, 706–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W. Attention to attention. Organization Science 2011, 22, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, D.G.; Rubin, J.Z. (1986). Social conflict: Escalation, impasse, and resolution. A: MA.

- Scott, J. (2000). Social Network Analysis: A Handbook, S: Edition (originally 1991). London, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Staw, B.M.; Boettger, R.D. Task revision: A neglected form of work performance. Academy of Management Journal 1990, 33, 534–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangirala, S.; Ramanujam, R. Employee silence on critical work issues: The cross level effects of procedural justice climate. Personnel Psychology 2008, 61, 37–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, C.; Butera, F. Hidden profiles and concealed information: Strategic information sharing and use in group decision making. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2009, 35, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, L.; Cummings, L.L.; Parks, J.M. Extra-role behaviors-in pursuit of construct and definitional clarity (a bridge over muddied waters). Research in Organizational Behavior: an Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews 1995, 17, 215–285. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyne, L.; LePine, J.A. Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal 1998, 41, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramani, V.; Tangirala, S. When and why do central employees speak up? An examination of mediating and moderating variables. Journal of Applied Psychology 2010, 95, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications.

- Wise, S. Can a team have too much cohesion? The dark side to network density. European Management Journal 2014, 32, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withey, M.J.; Cooper, W.H. Predicting exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect. Administrative Science Quarterly 1989, 34, 521–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, P. Discipline versus passion: Collectivism, centralization, and ambidextrous innovation. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 2015, 32, 745–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G.; Falbe, C.M. Influence tactics and objectives in upward, downward, and lateral influence attempts. Journal of Applied Psychology 1990, 75, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerubavel, E. (2006). The elephant in the room: Silence and denial in everyday life. Oxford University Press.

- Zheng, X.; Liu, X.; Liao, H.; Qin, X.; Ni, D. How and when top manager authentic leadership influences team voice: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Business Research 2022, 145, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).