1. Introduction

In the context of supply chain and inventory management, planning plays a critical role in the effectiveness of replenishment strategies [

1]. Well-designed planning processes help maintain optimal inventory levels, balancing the risk of overstocking—which leads to increased storage costs—with the risk of stockouts, which can cause lost sales and diminished customer satisfaction [

2]. By ensuring the timely availability of products, components, or raw materials to meet production schedules or customer demand, effective planning contributes directly to improved service levels and enhanced customer loyalty [

3]. These challenges are further compounded under conditions of uncertainty, where variability in demand and supplier lead times can significantly disrupt replenishment decisions.

In replenishment management, planning is essential to maintaining a balance between supply and demand, minimizing costs, and ensuring customer satisfaction [

4]. Effective planning enables the optimal implementation of replenishment policies [

5], aligning inventory decisions with strategic business objectives such as cost reduction and high product availability. These policies adjust order quantities and stock levels based on real-time market conditions. The effectiveness of such planning depends largely on its ability to adapt to various sources of uncertainty arising from collaborative operations between manufacturers and customers, interactions with suppliers of raw materials or critical components, and even internal manufacturing processes [

6]. The nature of this uncertainty is multifaceted [

7], often resulting in increased operational costs, reduced profitability, and diminished customer satisfaction [

8]. Numerous studies emphasize key sources of uncertainty in manufacturing environments, including demand variability, fluctuations in supplier lead times, quality issues, and capacity constraints [

9].

Demand uncertainty significantly impacts supply chain design. While stochastic programming models outperform deterministic approaches in optimizing strategic and tactical decisions [

10], most studies overlook lead time variability caused by real-world disruptions. Companies typically address supply uncertainty through safety stocks and safety lead times [

11], which trade off shortage risks against higher inventory costs. The key challenge lies in finding the optimal balance between these competing costs. For a long time, lead time uncertainty received relatively little attention in the literature, with most research in inventory management focusing predominantly on demand uncertainty [

12]. In assembly systems, component lead times are often subject to uncertainty; they are rarely deterministic and typically exhibit variability [

13].

The literature on stochastic lead times in assembly systems has seen significant contributions that have shaped current approaches to inventory control under uncertainty[

14]. A notable study by [

15] investigates a single-level assembly system under the assumptions of stochastic lead times, fixed and known demand, unlimited production capacity, a lot-for-lot policy, and a multi-period dynamic setting. In this work, lead times are modeled as independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) discrete random variables. The authors focus on optimizing inventory policies by balancing component holding costs and backlogging costs for finished products, ultimately deriving optimal safety stock levels when all components share identical holding costs. This problem is further extended in [

16], which considers a different replenishment strategy—the Periodic Order Quantity (POQ) policy. In [

17], the lot-for-lot policy is retained but a service level constraint is introduced. A Branch and Bound algorithm is employed to manage the combinatorial complexity associated with lead time variability. Subsequent studies [

18,

19], and [

20] build on this foundation by refining models to better capture lead time uncertainty in single-level assembly systems, while also proposing extensions to multi-level systems and providing a more detailed analysis of the trade-offs between holding and backlogging costs.

Modeling multi-product, multi-component assembly systems under demand uncertainty is inherently complex. [

21] proposes a modular framework for supply planning optimization, though its effectiveness depends on computational reductions and assumptions about probability distributions. For Assembly-to-Order systems, [

22] develops a cost-minimization model incorporating lead time uncertainty, solved via simulated annealing. Several studies [

23,

24,

25] and [

26] address single-period supply planning for two-level assembly systems with stochastic lead times and fixed end-product demand. Using Laplace transforms, evolutionary algorithms, and multi-objective methods, they optimize component release dates and safety lead times to minimize total expected costs (including backlogging and storage costs). [

2] later improved upon [

18]’s work, while [

27] extended the framework to multi-level systems under similar assumptions.

Existing models often rely on oversimplified assumptions about delivery times and demand, limiting their practical applicability [

21]. This highlights the need for new optimization frameworks that better capture real-world complexities and component interdependencies in assembly systems. We enhance [

15]’s method by incorporating : (1) stochastic demand models, (2) ordering and stockout penalty costs, and (3) MDP-based stochastic modeling. Deep reinforcement learning techniques, are employed to optimize solutions under delivery and demand uncertainties.

Over the years, various modeling approaches have been proposed to address uncertainty [

28], including: Conceptual models: Theoretical approaches to understand the relationships between variables, Analytical models: use of mathematical formulas to optimize decisions, Simulations: reproduction of system behavior to test different policies and Artificial intelligence: use of algorithms to predict and optimize decisions. The choice of approach depends on key characteristics of the manufacturing context.

Production Planning and Control (PPC) must combine rigorous planning with technological flexibility to adapt to the complex dynamics of supply chains [

29]. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI), such as reinforcement learning (RL), and digital tools is now essential to achieve these objectives[

30]. This trend aligns with Industry 4.0, where AI and machine learning play a central role in improving industrial efficiency. Industry 4.0 represents a major transformation in production systems, and PPC is evolving toward self-managing systems that combine automation (e.g., robots and smart sensors) with decision-making autonomy (e.g., AI and machine learning) [

29]. This paper [

31] presents a systematic review of 181 scientific articles exploring the application of reinforcement learning (RL) techniques in PPC. It provides a mapping of RL applications across five key areas of PPC: Resource planning, capacity planning, purchasing and supply management, production scheduling and Inventory Management.

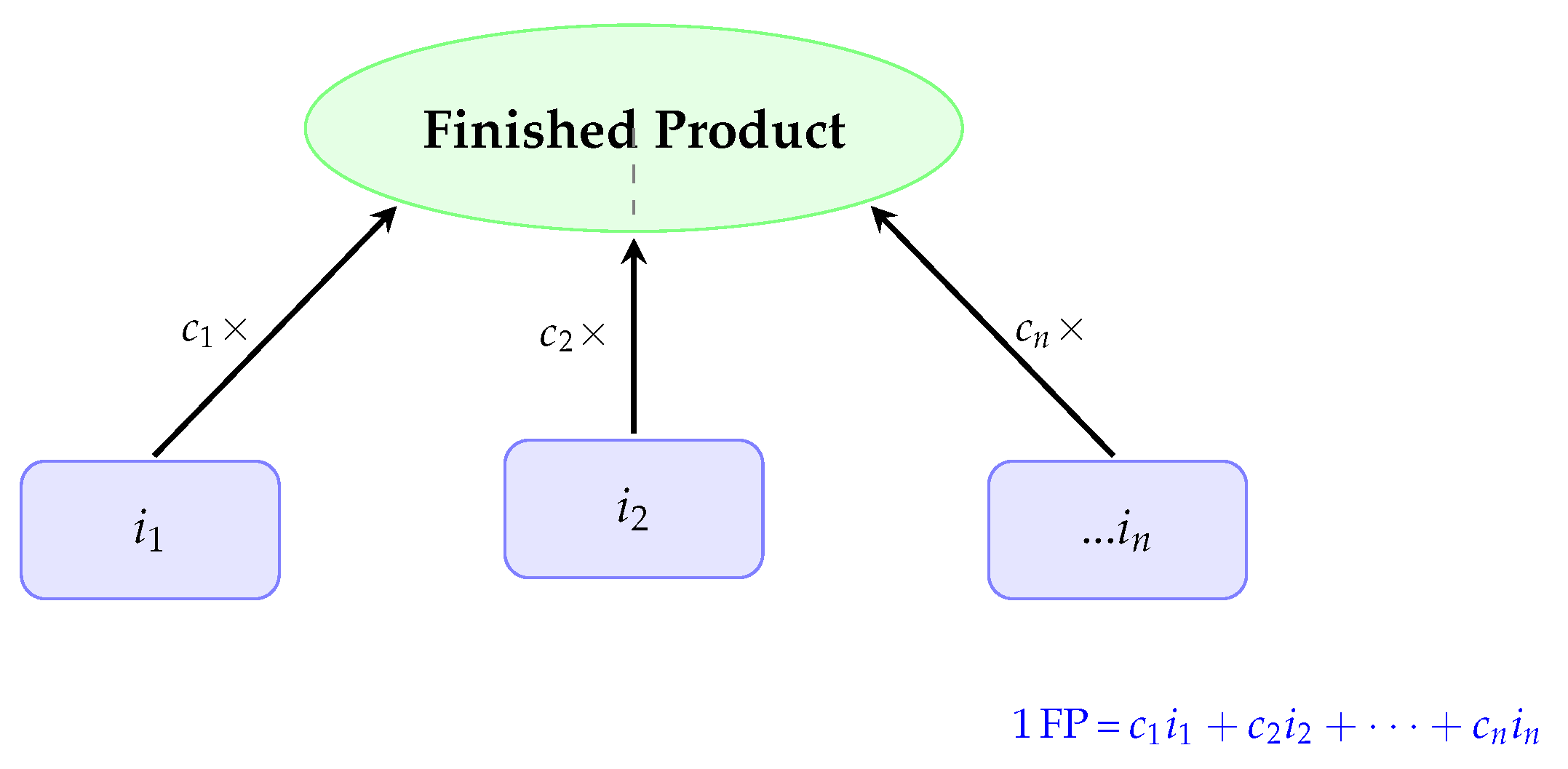

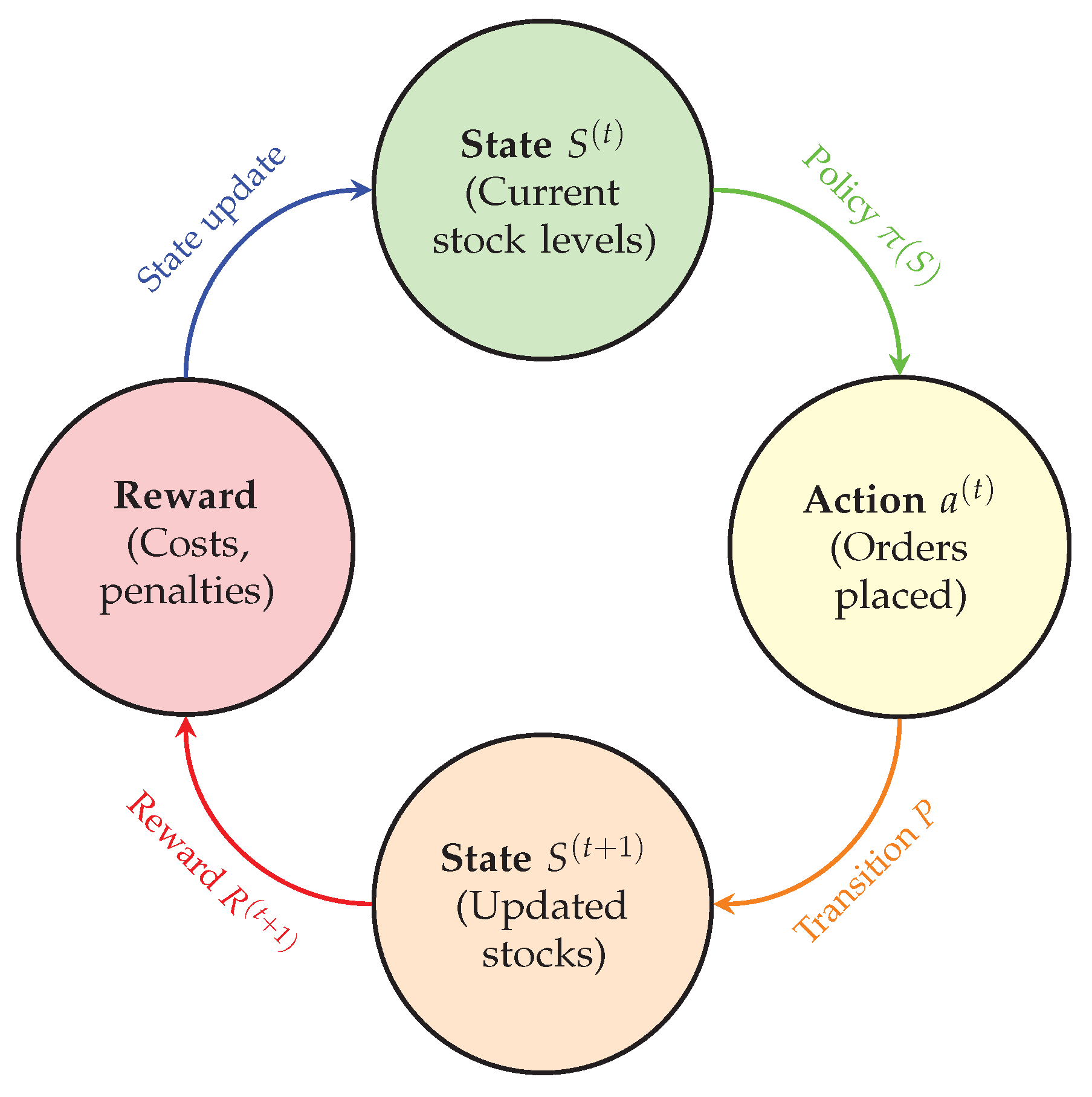

This study develops a discrete inventory optimization model for single-level assembly systems (multi-component, multi-period) under stochastic conditions. Overcoming existing limitations, we: Integrate multiple logistics costs,Relax restrictive assumptions (uniform delivery distributions, fixed demand, uniform storage costs), introduce component-based stockout calculation, employ deep reinforcement learning for efficient implementation. The model features integer decision variables for MRP compatibility while addressing dual uncertainties (demand/delivery). Current scope remains assembly-level systems. The problem involves optimizing replenishment policies under uncertainty. We chose to use a Deep Q-Network (DQN) algorithm, a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) approach that learns an optimal replenishment policy through interactions with the environment. We avoid traditional optimization methods because they are often unsuitable for inventory management problems with uncertain delivery times and stochastic demand [

32].

The first challenge in optimizing replenishment policies under uncertainty lies in the inadequacy of classical optimization methods. We chose to use a Deep Q-Network (DQN) algorithm, a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) approach that learns an optimal replenishment policy through interactions with the environment. We avoid traditional optimization methods because they are often unsuitable for inventory management problems with uncertain delivery times and stochastic demand [

32]. Overly Simplistic Assumptions: Classical methods (e.g., deterministic or stochastic optimization) typically assume that problem parameters—such as delivery times and demand—are either deterministic or follow simple, easily exploitable distributions [

33]. However, in real-world scenarios, delivery times are often random with complex probability distributions, making classical modeling approaches highly impractical. Adaptability to Uncertainty: Unlike traditional methods, DQN does not require explicit modeling of distributions. Instead, it dynamically adapts to uncertainties by learning from experience, making it more robust in stochastic environments.

The second challenge lies in the complexity and high dimensionality of the problem, which involves multiple dynamic factors: time-varying inventory levels, uncertain delivery times, stochastic demand, and multiple cost structures (e.g., holding, shortage, and ordering costs). Traditional optimization methods struggle with such complexity: Linear Programming (LP) becomes inapplicable due to the explosion of variables and constraints in realistic scenarios [

34]. Classical Dynamic Programming (DP) suffers from the curse of dimensionality [

35], as it requires storing and computing excessively large value tables [

36]. These limitations motivate the use of Deep Q-Networks (DQN) [

37], which leverage neural networks to approximate the

function efficiently. Unlike DP, DQN avoids explicit state enumeration and instead generalizes across states, making it scalable to high-dimensional problems [

38].

The third critical aspect involves the system’s dynamics and adaptability requirements in real industrial environments, where practical challenges emerge such as fluctuating periodic demand and unpredictable delivery times, necessitating dynamic decision-making. Traditional models prove inadequate for these scenarios as they typically employ static approaches or require computationally intensive re-optimization processes [

39]. In contrast, the Deep Q-Network (DQN) framework dynamically adapts its policy through continuous learning from system observations, enabling it to develop optimal sequential decision strategies that effectively minimize long-term operational costs without explicit re-optimization [

40].

This paper is organized as follows:

Section 1 provides an introduction to the research context and outlines relevant work in supply planning under uncertainty, emphasizing key challenges and gaps in existing approaches.

Section 2 describes the problem in detail, including the characteristics of the inventory environment and the sources of uncertainty.

Section 3 presents the proposed methodology, including the formulation of the problem as a Markov Decision Process (MDP).

Section 4 introduces the Deep Q-Network (DQN) algorithm and explains its implementation for learning optimal replenishment policies.

Section 5 discusses the experimental results and provides an analysis of the findings. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the main contributions, acknowledging limitations, and suggesting directions for future research.

5. Results and Discussion

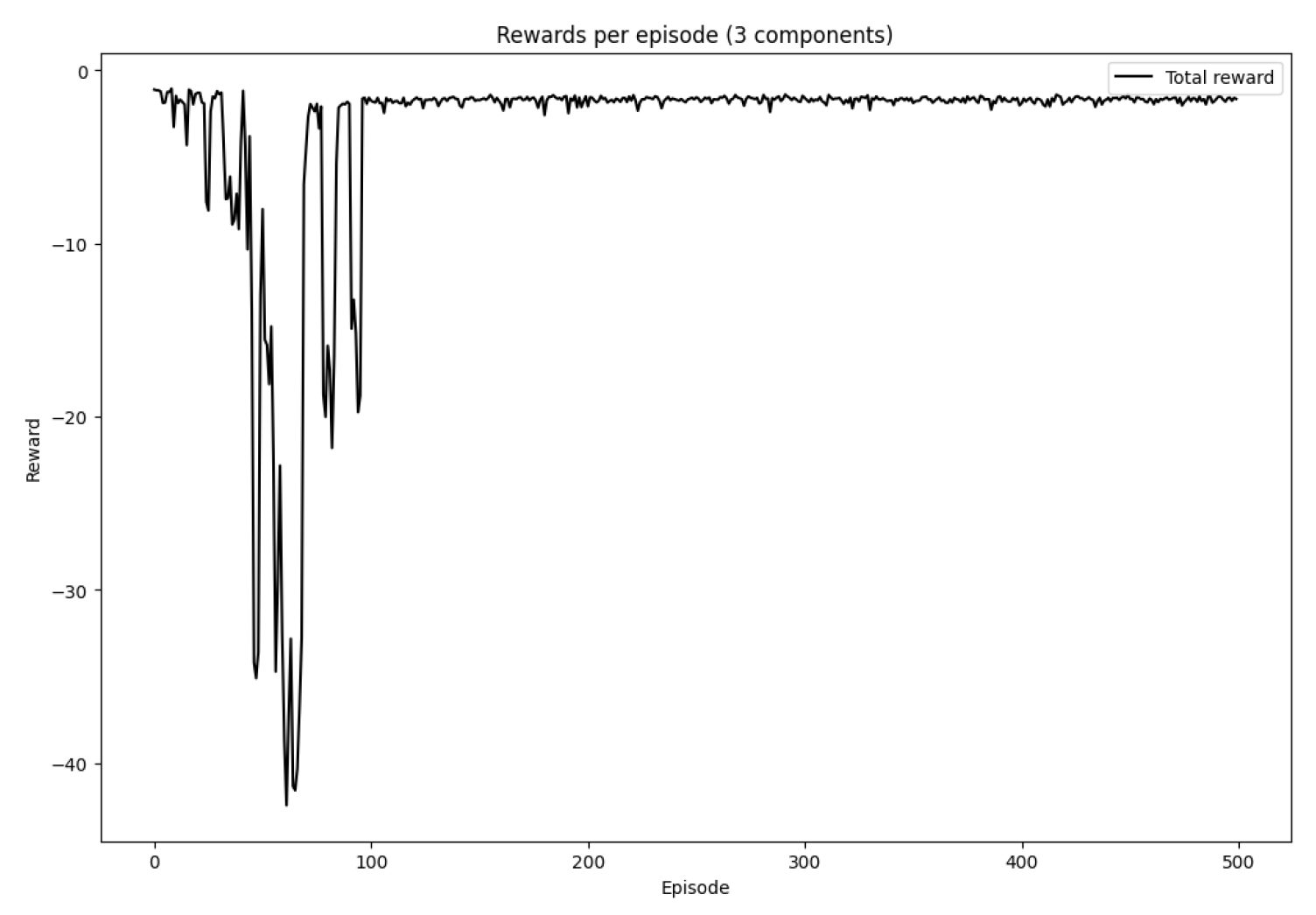

The environment parameters define the operational characteristics of the inventory system, such as the number of components, penalty and holding costs, demand and lead time uncertainties, and the structure of consumption. These parameters ensure the simulation accurately reflects the complexities of real-world supply chains. The agent parameters govern the learning process, including the neural network architecture, learning rate, exploration behavior, and training configuration. The inclusion of a replay buffer further enhances learning stability by breaking temporal correlations in the training data. The DQN algorithm is employed to learn optimal ordering policies over time. By interacting with the environment through episodes, the agent receives feedback in the form of rewards, which reflect the balance between minimizing shortage penalties and storage costs. To facilitate the simulation and make the analysis more interpretable, simple parameter values were used in the first table, including, limited lead time possibilities, and a small range of demand values. Additionally, the reward function was normalized (reward divided by 1000) to simplify numerical computations and stabilize the learning process. Despite this simplification, the implemented environment and reinforcement learning algorithms are fully generalizable: they can handle any number of components (n), multiple lead time scenarios, and a range of demand values (m), making the model adaptable to more complex and realistic settings. However, scaling up to larger instances requires significant computational resources, as the state and action spaces grow exponentially. Therefore, a powerful machine is recommended to run simulations efficiently when moving beyond the simplified test case.

The algorithm is developed using the Python programming language, which is particularly well-suited for research in reinforcement learning and operations management due to its expressive syntax and the availability of advanced scientific libraries. The implementation employs NumPy for efficient numerical computation, particularly for manipulating multidimensional arrays and performing vectorized operations that are essential for simulating the environment and computing rewards. Visualization of training performance and inventory dynamics is facilitated through Matplotlib, which provides robust tools for plotting time series and comparative analyses. The core reinforcement learning model is implemented using PyTorch, a state-of-the-art deep learning framework that supports dynamic computation graphs and automatic differentiation. PyTorch is used to construct and train the deep Q-network (DQN), manage the neural network architecture, optimize parameters through backpropagation, and handle experience replay to stabilize the learning process. Collectively, these libraries provide a powerful and flexible platform for modeling and solving complex inventory optimization problems under stochastic conditions.

Lead Time and Risk Analysis

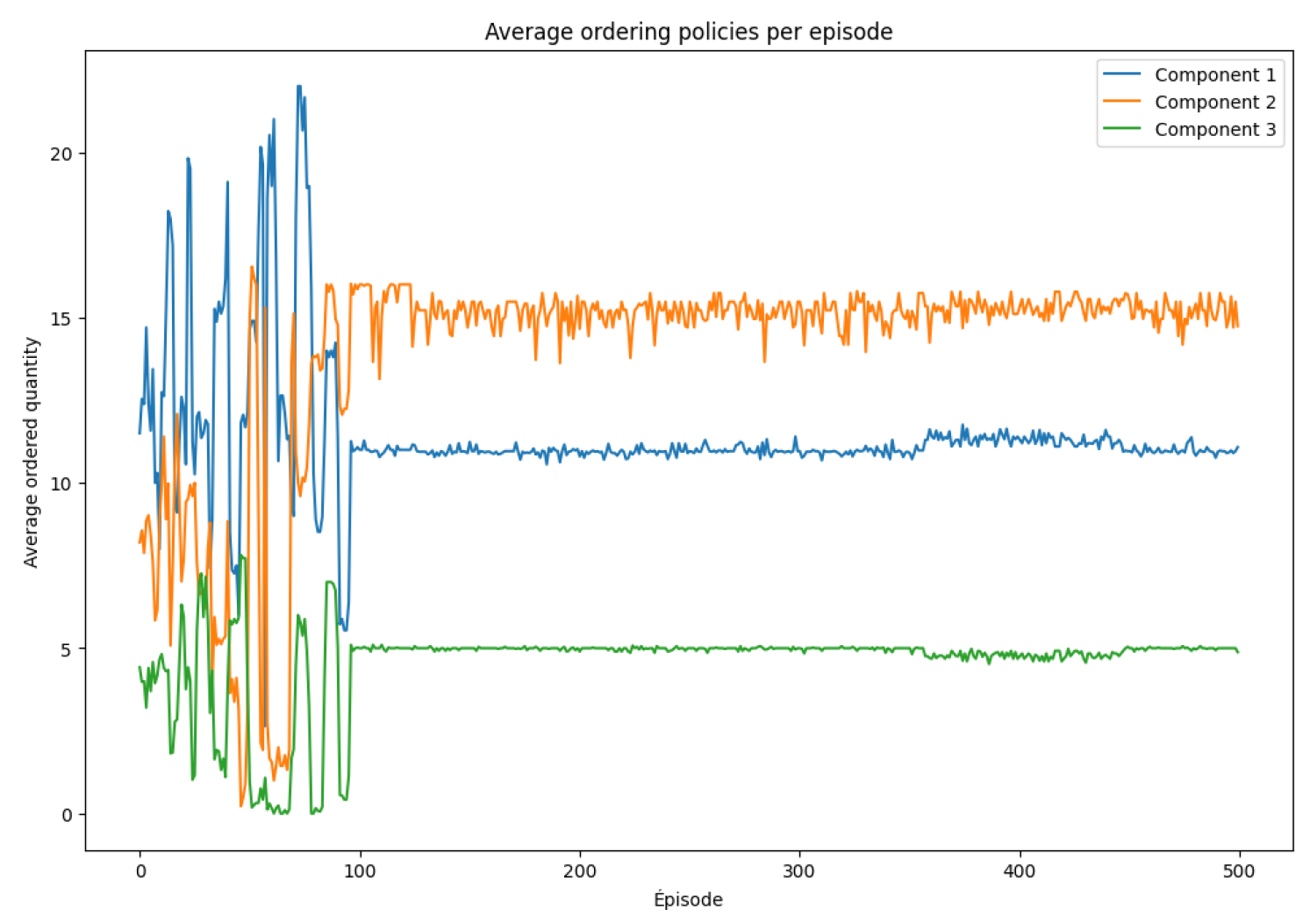

The three components in the inventory system exhibit distinct patterns in both consumption and lead time variability, which significantly influence their associated risks. Component , with the highest consumption coefficient, demonstrates a relatively stable delivery profile: 80 % of its orders are fulfilled within 1 or 2 periods, making it the least risky in terms of delays. In contrast, Component , which has a moderate consumption rate of 2, faces greater uncertainty— 30% of its orders experience a delay of 3 periods, and 40% are delayed by 2 periods. This combination indicates a substantial risk of stockout if not managed carefully. Component , despite its lower consumption rate of 1, shares the same 30% probability of a 3-period delay as but has only a 10% chance of being delivered within 1 period, the lowest among all components. This makes the most vulnerable to supply disruptions. Overall, the risk of delivery delays is highest for , followed closely by , while remains the most reliable in terms of lead time performance.

5.1. Impact of Lead Times on Ordered Quantities

When a component has a longer and more uncertain lead time, the agent tends to adapt its ordering strategy to mitigate the risk of stockouts. This often results in placing orders more frequently in anticipation of potential delays. Additionally, the agent may choose to maintain a higher inventory level as a buffer, ensuring that production is not interrupted due to late deliveries.

Table 4 presents a detailed analysis of the relationship between each component’s consumption level, its lead time uncertainty, and the resulting ordering behavior by the agent. Components with higher consumption but more reliable lead times, such as

, allow for stable and moderate ordering. In contrast, components like

and especially

, which are subject to longer and more uncertain delivery delays, require the agent to compensate by increasing order frequency . This strategic adjustment helps to avoid shortages despite the variability in supplier lead times. The table summarizes these insights for each component.

To better understand the agent’s ordering behavior,

Table 5 addresses key questions regarding the observed stock levels for each component. Although one might expect ordering decisions to align directly withconsumption coefficient, this is not always the case. In reality, the agent adjusts order quantities and stock levels by taking into account both the demand and the uncertainty in lead times. As shown below, components with higher risk of delivery delays tend to be stocked more heavily, even if their consumption coefficient is relatively low, while components with reliable lead times require less buffer stock.

Summary of Effects

Table 6.

Summary of lead time effects on stock levels.

Table 6.

Summary of lead time effects on stock levels.

|

|

Lead Time |

Agent’s Strategy |

|

High |

Stable (80% ≤ 2 periods) |

Moderate stock, regular orders |

|

Medium |

30% risk of 3-period delay |

Higher stock to avoid shortages |

|

Low |

Highly uncertain (30% in 3 periods) |

Higher stock than expected |

Final Observation: The agent adjusts decisions based on lead time risks, not just consumption rates.

5.2. Impact of Uncertain Demand on Order Quantities

The expected demand for the finished product is:

Table 7.

Expected Demand per Component.

Table 7.

Expected Demand per Component.

| i |

|

Formula |

Expected Required Quantity |

|

3 |

|

6.3 |

|

2 |

|

4.2 |

|

1 |

|

2.1 |

This suggests that, in an ideal case without lead time risks, the order quantities should follow the ratio :

Variability in Demand and Its Effect

In addition to lead time uncertainties, the agent must also consider variability in demand and cost-related trade-offs when determining order quantities. The decision-making process is not only influenced by the likelihood of delayed deliveries but also by how demand fluctuates over time and how different types of costs interact.

Table 8 outlines the key factors that affect the agent’s ordering behavior and explains their respective impacts on the optimal policy formulation.

Interplay Between Demand Uncertainty and Lead Time Risks

If the observed order quantities do not strictly follow the expected pattern , this may be due to the agent anticipating delivery delays and adjusting order sizes accordingly. Such adjustments also reflect an effort to minimize shortage costs, potentially resulting in overstocking components with uncertain lead times. Additionally, the agent may adopt a dynamic policy that evolves over time in response to past shortages, modifying future decisions based on observed system performance. Demand uncertainty forces the agent to carefully balance risk and cost, and while component should theoretically be ordered the most due to its high consumption, the impact of lead time variability and the need to hedge against delays can significantly alter this behavior.

Good Points in Our Model:

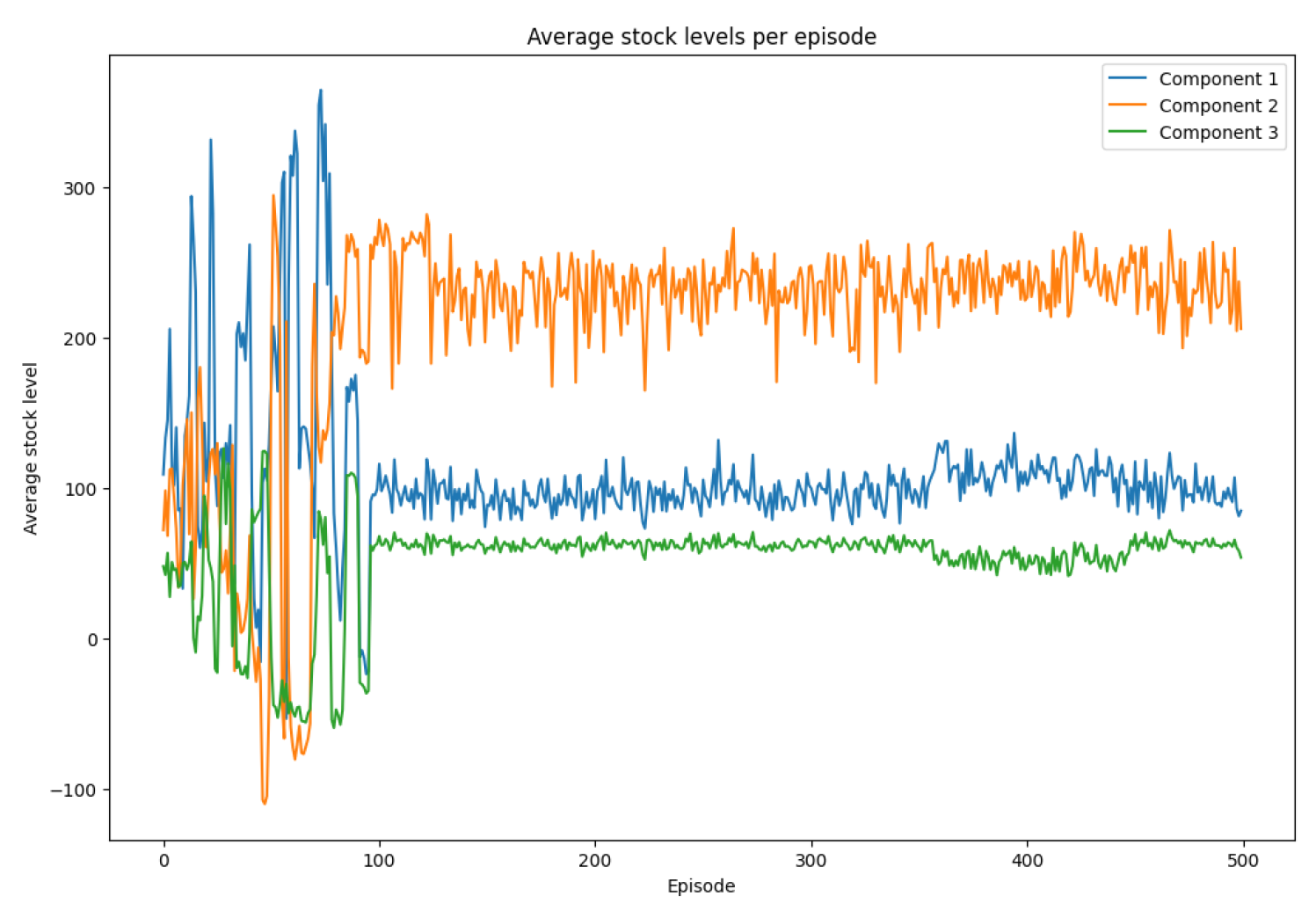

Model convergence: The total reward stabilizes after approximately 100 episodes, indicating that the agent has found an efficient replenishment policy.

Improved ordering decisions: The ordered quantities for each component become more consistent, avoiding excessive fluctuations observed at the beginning.

Reduction of stockouts: Despite some variations, the average stock levels tend to remain positive, meaning the agent learns to anticipate demand and delivery lead times.

Adaptation to uncertainties: The agent appears to adapt to random lead times and adjusts its orders accordingly.