1:. Introduction

1.1. Background and Context

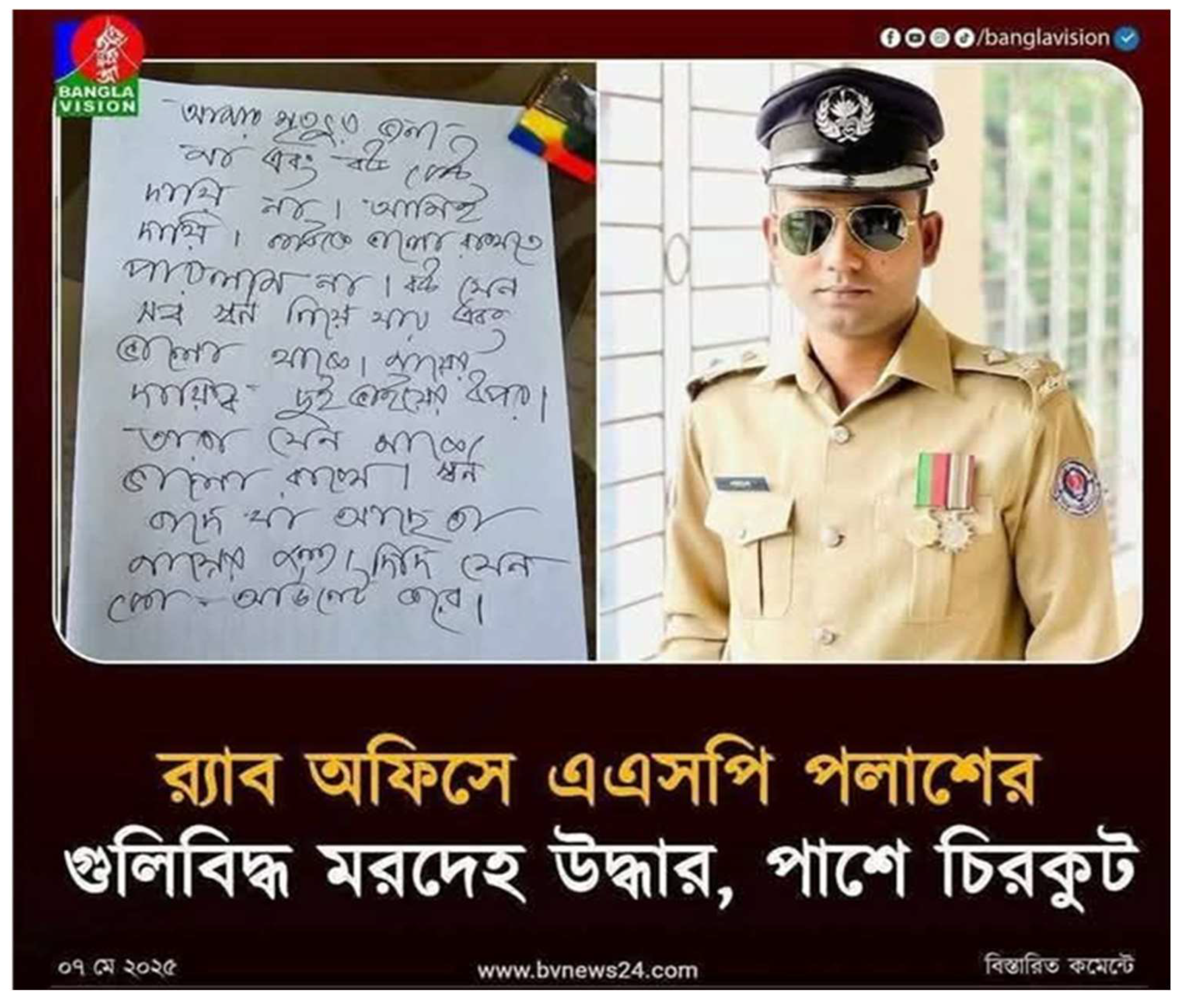

Suicide remains one of the leading causes of death among young people worldwide, with university students considered a particularly vulnerable group due to the unique psychological, academic, and social pressures they experience (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). In Bangladesh, the prevalence of suicide among university-aged individuals has risen alarmingly in recent years, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted educational norms, social interactions, and mental well-being (Chowdhury et al., 2022). Recent media reports and police records indicate a growing trend among students to express suicidal ideation through digital mediums such as social media platforms, messaging apps, and even blog entries—raising new concerns about the convergence of digital communication and mental health distress (Arafat et al., 2021).

This research seeks to explore the intersection of suicidal expression and digital communication by focusing on male and female university students in Bangladesh. It aims to examine the content, context, and gendered patterns in suicidal notes and messages disseminated via social media and traditional means. The study also considers how social media environments both facilitate and potentially exacerbate suicidal tendencies.

2.2. Defining Suicide and Suicidal Communication

Suicide, as defined by the WHO (2021), is the act of deliberately ending one's life, and it is frequently preceded by suicidal ideation, planning, and communication. Suicidal communication often involves expressions of intent, emotional pain, hopelessness, or bids for help—delivered either directly or symbolically (Joiner, 2005). In many instances, individuals leave behind suicide notes—written, typed, or recorded—which serve as a final communication to their loved ones, society, or the world at large (Leenaars, 1999). With the advent of digital platforms, traditional suicide notes have evolved into digital messages, social media status updates, tweets, Instagram captions, or WhatsApp voice notes, adding a new dimension to the study of suicidality (Luxton, June, & Fairall, 2012).

2.3. The Digital Landscape and Mental Health in Bangladesh

Bangladesh has undergone rapid digital transformation over the past decade, with over 130 million internet users and more than 50 million active social media users as of 2024 (Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission [BTRC], 2024). Among university students, platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and TikTok are popular modes of expression, identity negotiation, and peer interaction (Rahman & Roy, 2021). However, increased digital immersion has also been associated with heightened levels of anxiety, depression, cyberbullying, body image issues, and social comparison—factors that are significantly correlated with suicidal ideation (Mamun et al., 2020; Islam et al., 2021).

While digital tools have enabled mental health advocacy, peer support groups, and online counseling, they have also exposed students to 24/7 connectivity, surveillance, and emotional overexposure. In this context, suicidal notes published or hinted at online have become more frequent, particularly among youth who perceive these platforms as spaces of validation, confession, or escape.

2.4. Gender, Mental Health, and Suicide in South Asia

South Asia exhibits a complex and gendered landscape of mental health and suicide. In Bangladesh, the interplay of patriarchy, socio-economic constraints, and family pressures produces distinct experiences of distress for male and female students. Male students are often burdened with societal expectations of economic productivity and emotional stoicism, while female students frequently experience gender-based discrimination, mobility restrictions, and vulnerabilities to sexual harassment (Hossain, 2019). These lived realities are mirrored in the modes of suicidal expression and the linguistic features of suicide notes.

Previous research has suggested that women tend to leave more emotionally expressive suicide notes that appeal to relational values, while men are more likely to focus on themes of failure, burden, or nihilism (Canetto & Lester, 1995; Leenaars, 1999). However, little scholarly attention has been paid to how these tendencies translate into digital suicide notes among Bangladeshi youth, particularly within university settings.

2.5. Social Media as a Space for Suicidal Expression

Digital platforms have altered not only the means of social interaction but also the way people express distress and suicidal thoughts. Scholars like Naslund et al. (2016) argue that social media provides an outlet for individuals to express depressive or suicidal thoughts, often serving as a space for indirect communication or cries for help. The phenomenon of digital suicide notes—public or semi-public posts that signal impending suicide—has been documented globally (Luxton et al., 2012) but remains under-investigated in the Bangladeshi context. For instance, Facebook statuses such as ‘Goodbye, cruel world,’ or TikTok videos containing melancholic imagery and farewells have been observed among young people prior to suicides, yet these expressions are frequently dismissed as attention-seeking rather than urgent indicators of mental health crises (Mamun & Griffiths, 2020).

Furthermore, algorithmic amplification of emotionally charged posts, virality of tragic messages, and online bystander apathy can aggravate suicidal risk rather than mitigate it. This study contends that understanding how suicidal notes operate within digital ecosystems is crucial to the development of effective prevention models.

2.6. Research Problem

Although suicidology in Bangladesh has gained attention in recent years, most studies focus on prevalence rates, causes, or psychiatric interventions, with limited exploration of the communicative and technological dimensions of suicide. The role of social media in shaping suicidal tendencies, especially in relation to gender, remains largely unexplored. Suicide notes—whether handwritten or digital—offer valuable insights into the emotional, social, and psychological dimensions of suicide but are rarely analyzed in relation to the digital behaviors and gendered identities of Bangladeshi students.

This research addresses this gap by systematically examining the textual and emotional content of suicidal notes among male and female students and situating them within the broader digital communication patterns and socio-cultural frameworks of Bangladesh.

2.7. Significance of the Study

This study contributes to the emerging field of digital suicidology by examining how Bangladeshi youth utilize digital spaces to express suicidal thoughts, and how these tendencies vary by gender. It provides empirical evidence to inform university counseling services, mental health policymakers, and digital platforms seeking to identify and prevent suicide risks. By analyzing suicide notes as communicative artifacts—rich in affect, narrative, and identity—the research offers a nuanced perspective on mental health, gender, and digital culture in South Asia.

2.8. Research Questions

This study is guided by the following research questions:

What are the linguistic, thematic, and emotional features of suicidal notes left by male and female university students in Bangladesh?

How do digital platforms influence the way suicidal intentions are communicated by young people?

What gendered patterns emerge in the expression of suicidal ideation through social media?

What social, academic, and emotional factors are reflected in suicidal notes among university students?

3. Introduction to Suicidology and Communication

Suicide has long been studied as a complex psychological, social, and cultural phenomenon. The field of suicidology has evolved to incorporate various interdisciplinary perspectives, including psychiatry, sociology, public health, communication studies, and more recently, digital media studies. The concept of suicidal communication—whether verbal, behavioral, or written—has emerged as a critical avenue for understanding individuals’ mental states and identifying risk factors prior to suicide attempts (Joiner, 2005; Leenaars, 1999). Suicide notes in particular are valuable primary texts that offer insight into the individual’s reasoning, emotions, and social contexts surrounding the act (Leenaars, 1988; Pestian et al., 2012). These notes—traditionally handwritten—have now transitioned into digital formats, including social media posts, texts, and voice memos, broadening the communicative scope of suicidology.

3.1. Traditional Suicide Notes: Historical and Psychological Insights

Studies on traditional suicide notes began in earnest in the 1960s, primarily in Western contexts. Researchers analyzed notes for patterns in tone, content, and psychological indicators. Shneidman and Farberow (1961), pioneers in this domain, argued that suicide notes often contain rational and coherent messages aimed at explaining the act, assigning blame, or seeking forgiveness. Subsequent research by Leenaars (1999) identified recurring psychological themes such as unbearable psychological pain (psychache), hopelessness, and perceived burdensomeness.

Gendered patterns in suicide notes have also been extensively documented. Canetto and Lester (1995) observed that female-authored notes tend to be more emotionally expressive and relational, often referencing family and interpersonal bonds, while male notes are more likely to reflect themes of isolation, failure, and existential despair. However, most of this literature is based on physical notes and lacks context from the Global South, including South Asia and Bangladesh.

3.2. The Emergence of Digital Suicide Notes

In the age of smartphones and social media, suicide notes are increasingly expressed digitally—sometimes replacing traditional letters entirely. The term ‘digital suicide note’ refers to any electronic message, post, or media shared prior to a suicide that communicates intent, rationale, or emotional distress (Luxton et al., 2012). Researchers have identified numerous formats, including Facebook statuses, Instagram captions, WhatsApp messages, tweets, TikTok videos, and YouTube livestreams.

Luxton, June, and Fairall (2012) emphasized that digital platforms enable real-time broadcasting of suicidal ideation, thereby increasing both the visibility of suicide and the potential for peer intervention—or neglect. The asynchronous and public nature of social media allows suicidal individuals to seek validation, deliver final messages, or dramatize their pain in a performative manner. However, digital notes can also be ignored, misunderstood, or worse, met with mockery—resulting in heightened risk of completed suicides.

In a landmark study, Robinson et al. (2016) found that young people who posted suicidal content online often received peer attention, but the quality and empathy of responses varied significantly. Moreover, researchers warned of ‘suicide contagion,’ where visible posts may normalize or inspire suicidal behavior in peers, particularly within youth networks.

3.3. Social Media, Mental Health, and Suicidal Ideation

Numerous studies have documented the relationship between social media usage and mental health deterioration among youth (Naslund et al., 2016; Keles et al., 2020). Excessive social media use has been linked to depressive symptoms, anxiety, loneliness, sleep deprivation, and cyberbullying—all of which are predictors of suicidal ideation. In South Asian contexts, where mental health stigma remains entrenched, young individuals often turn to online platforms for anonymous sharing, emotional release, or escape (Mamun & Griffiths, 2020).

In Bangladesh, Islam et al. (2021) and Mamun et al. (2020) documented a sharp increase in psychological distress among university students related to academic pressure, unemployment, and socio-cultural restrictions. Many of these students reported turning to Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok for distraction, peer interaction, or catharsis—yet these platforms also exposed them to toxic comparison, harassment, and content that reinforced feelings of inadequacy or despair.

Digital suicide notes in these settings often contain phrases such as ‘I’m tired of pretending,’ ‘Goodbye everyone,’ or ‘I hope you’ll understand,’ revealing both a desire to communicate pain and a yearning for posthumous validation. However, unlike Western settings, where mental health services are more accessible, Bangladeshi students have limited institutional or cultural support, making digital expression not only a cry for help but sometimes the final act of agency.

3.4. Gendered Dimensions of Digital Suicide Expression

Gender plays a central role in how individuals experience distress and communicate suicidal thoughts. Globally, while men are more likely to complete suicide, women are more likely to attempt it—often through less lethal means—and to seek help (WHO, 2021). In Bangladesh, a similar trend is evident, with young women often facing emotional abuse, societal restrictions, and gender-based violence that can lead to depression and suicidality (Hossain, 2019). Meanwhile, men face pressure to conform to rigid notions of masculinity, suppress emotions, and bear economic burdens, which can lead to internalized distress and higher rates of completed suicides (Arafat et al., 2021).

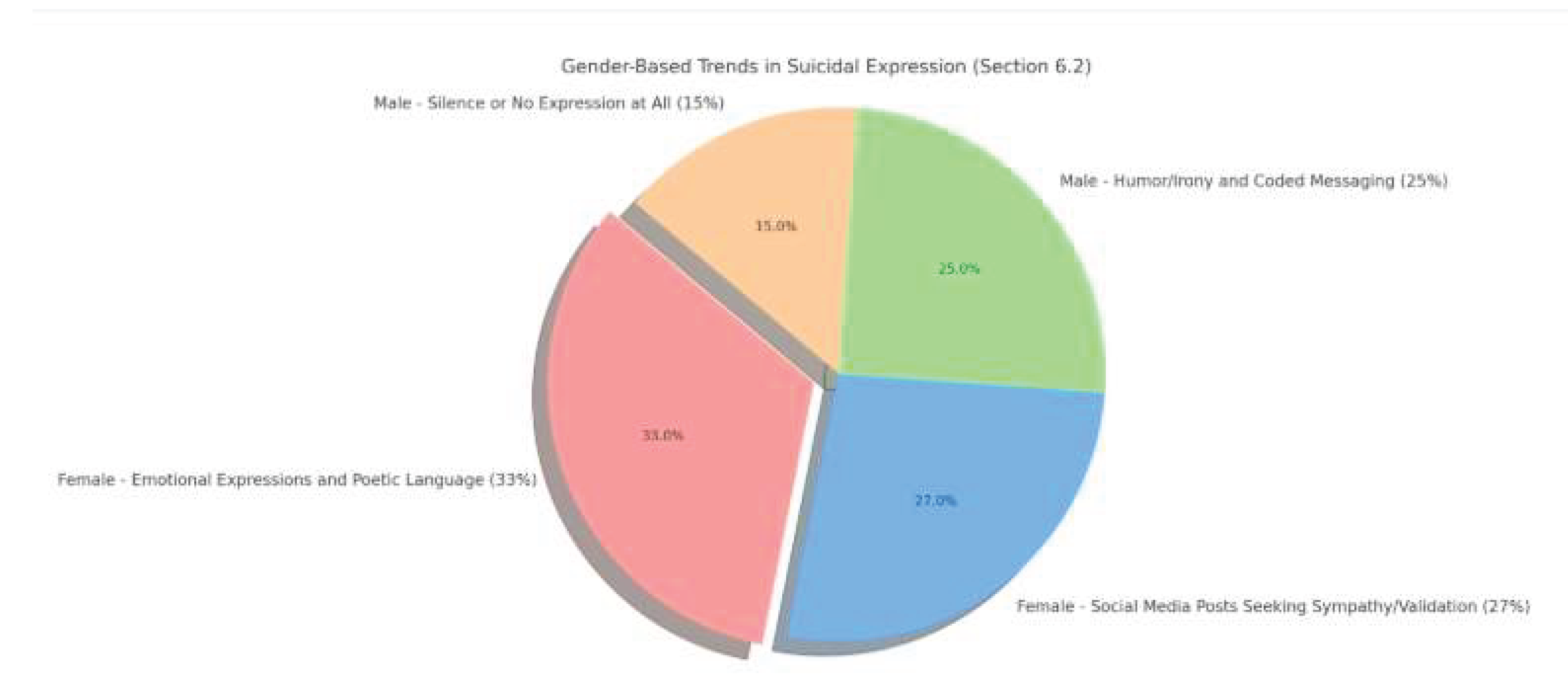

On social media, female students in Bangladesh have been found to express suicidal thoughts more subtly, often through cryptic posts, melancholic poetry, or symbolic imagery (e.g., sunsets, broken hearts), while male students are more likely to post overt expressions of anger, failure, or philosophical despair (Rahman & Roy, 2021). In digital suicide notes, women often include apologies or pleas for forgiveness, while men may express existential dissatisfaction or blame external forces.

A qualitative study by Mahmud and Chowdhury (2023) examining Facebook posts by deceased students revealed that female notes emphasized relational loss and betrayal, whereas male notes frequently focused on educational failure, economic stress, or loss of purpose. This gendered divergence suggests the importance of culturally and gender-sensitive approaches to digital suicide prevention.

3.5. Suicidal Behavior among Bangladeshi Students: Current Gaps

Despite growing concern over suicide in Bangladesh, especially among youth, research remains fragmented. Most existing studies emphasize epidemiological patterns or psychiatric conditions (Chowdhury et al., 2022), with limited attention to the communicative or digital aspects of suicidality. Furthermore, few studies analyze suicide notes—either traditional or digital—in depth, particularly through the lens of gender.

There is also a lack of integrated frameworks combining psychology, communication theory, and digital media analysis. As a result, suicide prevention policies remain limited in scope, failing to recognize the importance of online behavior, peer influence, and digital expression in identifying and mitigating risk.

3.6. Algorithms, Virality, and the Role of Platforms

Social media algorithms, designed to optimize engagement, often prioritize emotionally charged or visually striking content. This can lead to the unintended amplification of suicidal content—especially when users hint at suicide through images, music, or hashtags. Facebook, TikTok, and Instagram have introduced moderation tools and AI-based detection systems to identify such content (Facebook, 2023), but these tools are often limited by linguistic, cultural, and contextual understanding—making them less effective in Bangladesh.

A study by Pater and Mynatt (2017) noted that platform moderation mechanisms frequently fail to detect suicidal messages in non-English languages or culturally coded expressions. In Bangladesh, students may use Bengali-English mixed language, religious metaphors, or poetic devices to express despair—factors that automated systems struggle to interpret.

Moreover, platform responses often lack immediacy. In some cases, suicidal content goes viral posthumously, drawing attention to the act but failing to prevent it. This reactive visibility creates a paradox of ‘digital martyrdom,’ where suicide is recognized only after completion—rather than intervened upon in real time.

3.7. Toward a Digital Suicidology for South Asia

There is an emerging call within academia to develop a digital suicidology framework that incorporates cultural, technological, and gendered dimensions of suicide in the Global South. Scholars argue for the integration of machine learning, natural language processing, and ethnographic approaches to decode online suicidal expressions more accurately (Ghosh & Choudhury, 2020).

In the South Asian context, such frameworks must consider multilingualism, socio-religious norms, mental health stigma, and the absence of institutional mental health care. In Bangladesh, where social media often substitutes for therapeutic spaces, digital expressions of distress should be treated with the same seriousness as clinical symptoms.

This study aims to fill existing gaps by conducting a mixed-method analysis of suicidal notes and digital behaviors among university students in Bangladesh. By foregrounding gender, digital culture, and communicative intention, the research contributes to a more contextualized and actionable understanding of suicidality in the digital age.

4:. Theoretical Framework of the Study

A robust theoretical framework is essential for investigating the complex interplay of gender, suicidality, and digital expression in the context of Bangladeshi university students. This study draws on multiple intersecting theories from psychology, communication studies, digital media theory, and gender studies to explain how young individuals navigate mental health crises and suicidal ideation through social media. The framework is constructed around five key theoretical perspectives: (1) the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS), (2) the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), (3) Media Ecology Theory, (4) Gender Performativity Theory, and (5) the Concept of Digital Affect and Emotional Labor.

4.2 The Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS)

The Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide, proposed by Thomas Joiner (2005), provides a foundational psychological lens through which to analyze suicidal ideation and behavior. The theory posits that three main components must converge for an individual to die by suicide: (1) thwarted belongingness, (2) perceived burdensomeness, and (3) acquired capability for suicide. These elements are particularly salient in the Bangladeshi university context, where social isolation, academic failure, familial expectations, and economic pressures contribute to emotional and psychological vulnerability (Mamun et al., 2020).

Social media platforms often become arenas where these emotional states are either exacerbated or expressed. For instance, users expressing thwarted belongingness might post status updates that reflect feelings of abandonment or alienation (‘No one cares,’ ‘I’m alone’). Similarly, perceived burdensomeness may be visible in self-deprecating messages, apologies, or suicide notes addressed to family members. The acquired capability for suicide—often shaped by exposure to violent imagery, peer suicides, or normalized discourse around self-harm—may be amplified through digital networks (Bryan et al., 2010).

In the context of this study, IPTS helps explain how suicidal digital expressions (e.g., Facebook posts, WhatsApp messages, Instagram captions) can be interpreted as communicative manifestations of internal psychological states, and how gender moderates the way these elements are expressed.

4.3. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

Ajzen’s (1991) Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is useful for understanding the intentionality behind suicidal expression on social media. TPB posits that behavior is predicted by three factors: (1) attitude toward the behavior, (2) subjective norms, and (3) perceived behavioral control.

In the context of digital suicide notes, the ‘attitude toward the behavior’ may reflect how an individual evaluates suicide as a solution to emotional distress. For example, some students may rationalize suicide as an escape from suffering or a way to punish others, which may be reflected in poetic or symbolic suicide notes posted online. ‘Subjective norms’ refer to the perceived social acceptability of the act—many young users may be influenced by prior cases of suicide within their networks, creating a sense of validation or inevitability (Robinson et al., 2016). ‘Perceived behavioral control’ pertains to the individual’s assessment of their ability to carry out the suicide, which can also be inferred through messages like ‘I’ve had enough’ or ‘This time it’s real.’

By applying TPB to social media users in Bangladesh, this research explores how the digital environment mediates attitudes, social influences, and perceptions of control around suicide. For example, the normalization of suicidal discourse in closed Telegram or WhatsApp groups may serve to reduce psychological barriers to suicide attempts, particularly among males.

4.4. Media Ecology Theory

Proposed by Marshall McLuhan (1964) and later expanded by Neil Postman (1970), Media Ecology Theory posits that media environments shape the ways individuals think, feel, and communicate. This theory is especially relevant in the context of young digital natives in Bangladesh, who have grown up in an ‘always-on’ culture dominated by Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok.

Media Ecology suggests that the digital landscape is not a passive container for communication but an active environment that structures thought and behavior. For instance, the brevity of Twitter, the visuality of Instagram, and the ephemerality of Snapchat or TikTok create unique affordances for expressing mental health struggles. Suicide notes composed on these platforms are shaped by the constraints and features of the medium—brevity, performativity, aesthetics, and publicness.

Moreover, McLuhan’s aphorism ‘the medium is the message’ (McLuhan, 1964) gains renewed significance when a suicide note is posted as a TikTok video or an Instagram story. The very act of choosing a particular platform to communicate suicidal intent reveals not just the content but also the user’s intended audience, desired impact, and emotional state. In Bangladesh, where internet penetration is growing and digital expression is increasingly normalized, this theory helps contextualize the platform-specific nature of suicidal communication.

4.5. Gender Performativity Theory

Judith Butler’s (1990) theory of gender performativity emphasizes that gender is not a fixed identity but a set of repeated actions and expressions shaped by social norms. This theoretical lens is critical for understanding how male and female students in Bangladesh perform distress, vulnerability, or stoicism differently through their digital suicide notes.

For instance, male students often express existential frustration, financial inadequacy, or stoic resignation, aligning with hegemonic masculine ideals that discourage emotional vulnerability (Connell, 1995). Female students, in contrast, tend to foreground relational suffering, romantic betrayal, or familial pressure, often framing their distress within narratives of guilt, apology, or sacrifice (Canetto & Lester, 1995; Mahmud & Chowdhury, 2023).

On social media, these gendered scripts are not only performed but also surveilled by peers, families, and strangers. The fear of shame, exposure, or invalidation often determines the tone, visibility, and content of suicide notes. Butler’s framework allows us to interpret these digital performances as both personal expressions and social negotiations of gendered expectations. In this study, gender performativity theory is used to examine how students construct their emotional narratives based on culturally encoded ideas of masculinity and femininity.

4.6. Digital Affect and Emotional Labor

A newer body of theory explores the emotional dimensions of digital communication. Scholars like Hardt (1999), Paasonen (2016), and Papacharissi (2015) have argued that digital platforms are affective infrastructures that both enable and demand emotional performance. Suicidal notes on social media can be understood through the lens of ‘digital affect’—the transmission, modulation, and amplification of emotions in networked spaces.

Papacharissi (2015) refers to ‘affective publics,’ where emotional expressions serve as political or communal acts. In the Bangladeshi context, a suicide note posted on Facebook may generate hundreds of comments, shares, or reactions—transforming individual despair into collective mourning, judgment, or gossip. Emotional labor is involved not only in the composition of such notes but also in the audience's engagement—ranging from genuine empathy to performative sympathy.

This theory is especially useful in understanding the viral nature of some digital suicide notes in Bangladesh. Posts that are emotionally raw, poetic, or accompanied by visual media often receive more attention—creating a dangerous feedback loop where emotional visibility is rewarded even in the context of death. Gender again plays a role here, with female expressions of vulnerability often scrutinized or romanticized, while male expressions are more likely to be interpreted as signs of mental breakdown or tragedy.

4.7. Intersectionality and Cultural Contextualization

Kimberlé Crenshaw’s (1989) theory of intersectionality offers a necessary critical framework for understanding how various forms of social stratification—gender, class, religion, and age—intersect in the experiences of suicidal youth. In Bangladesh, where patriarchal norms, religious conservatism, and academic elitism co-exist, digital expressions of suicide are filtered through multiple lenses of stigma and power.

A lower-middle-class male student from a rural area may experience different social pressures and expressive limitations than an upper-class female student from Dhaka. Similarly, LGBTQ+ students may find themselves unable to express their identity, leading to increased risk of suicidal ideation and digital self-harm, often cloaked in coded language or ambiguous imagery.

This study adopts an intersectional lens to analyze how social inequalities and cultural taboos influence not only the causes of suicide but also the modes and meanings of digital suicide notes. Intersectionality also helps contextualize why some suicide notes become viral while others remain unnoticed or even deleted by families and institutions after the incident.

4.8. Synthesis: Toward a Holistic Theoretical Approach

By integrating these frameworks—IPTS, TPB, Media Ecology, Gender Performativity, Digital Affect, and Intersectionality—this study adopts a multifaceted approach to understanding suicidal communication among university students in Bangladesh. Each theory contributes to a layered analysis:

IPTS explains the internal psychological motivations.

TPB adds insight into behavioral intentionality and decision-making.

Media Ecology illuminates the structural influence of platforms.

Gender Performativity decodes culturally embedded scripts of distress.

Digital Affect reveals the emotional dynamics of online expression.

Intersectionality brings attention to structural and identity-based inequalities.

Together, these theories enable a comprehensive investigation into how digital suicide notes are shaped by personal, technological, and sociocultural forces, with particular attention to gender dynamics and regional specificities.

5:. Research Methodology

This section outlines the research design, methodology, data collection, and analysis strategies adopted to investigate the gendered patterns, psychological underpinnings, and communicative characteristics of suicidal notes and expressions on social media by university students in Bangladesh. A mixed-methods approach was employed to facilitate both depth and breadth in understanding this complex and sensitive subject. The methodology integrates qualitative content analysis of suicide notes and digital expressions with quantitative survey data to triangulate findings.

5.2. Research Design

Given the multidimensional nature of suicide, social media behavior, and gender identity, a concurrent triangulation mixed-methods research design was adopted (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). This design enables the parallel collection of both qualitative and quantitative data, which are then compared, contrasted, and interpreted to ensure richer insights and increased validity.

5.2.1. Rationale for Mixed-Methods

A purely qualitative approach would allow for detailed exploration of language, tone, and emotional narratives within suicidal notes. However, to generalize findings regarding trends, prevalence, and gender differentials, quantitative data are essential. The mixed-methods approach therefore addresses both interpretive depth and statistical representation (Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, & Turner, 2007).

5.3. Research Objectives

The research methodology was guided by the following specific objectives:

To identify the linguistic and emotional patterns in suicide notes and digital expressions posted by male and female students.

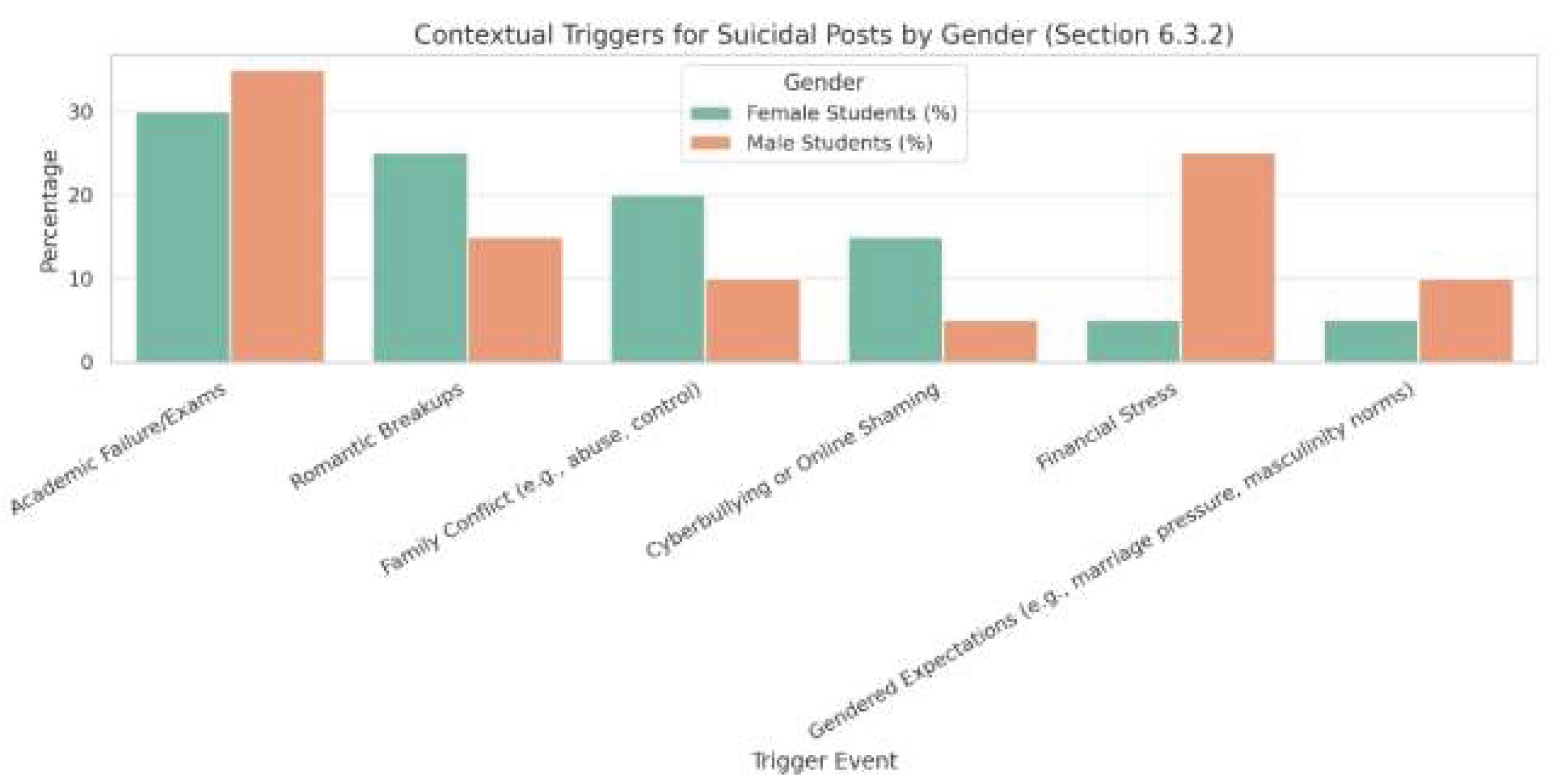

To explore the contextual factors (academic, romantic, familial, psychological) leading to suicidal ideation.

To examine gender-based differences in the tone, platform preference, and temporal proximity of suicide-related posts.

To understand the broader socio-digital ecology that facilitates or suppresses suicidal communication among Bangladeshi students.

5.4. Research Questions

The following research questions (RQs) guided the methodological development:

RQ1: What are the key themes, narratives, and emotional tones present in social media suicide notes by male and female students in Bangladesh?

RQ2: Are there gender-based differences in platform usage (e.g., Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, Telegram) for expressing suicidal thoughts?

RQ3: What are the common triggers and contexts reported by suicidal students prior to their final social media expressions?

RQ4: How do online audiences (friends, family, strangers) engage with such posts in real-time?

5.5. Study Area and Population

The study was conducted across five major university regions in Bangladesh: Dhaka, Chattogram, Rajshahi, Sylhet, and Khulna. The target population comprised undergraduate and postgraduate students enrolled in public and private universities who are active users of social media platforms. Particular attention was given to identifying individuals who had either directly written suicide notes on social media or who were closely associated (friends, partners, roommates) with someone who had.

5.6. Sampling Methods

5.6.1 Qualitative Sampling

For the qualitative component, a purposive sampling technique was applied to select 30 verified digital suicide notes posted between January 2020 and December 2024. These were retrieved from:

Public Facebook memorial pages, Screenshots shared on blogs and mental health forums, WhatsApp groups associated with university communities, TikTok and Instagram stories (archived via digital ethnographic tools).

The purposive sampling focused on diversity in gender, geographical location, language (Bangla and English), and platform of expression.

5.6.2. Quantitative Sampling

A stratified random sampling technique was used to survey 800 university students (400 males, 400 females) aged between 18 and 27 years across 10 universities. Stratification was based on institution type (public vs. private), geographic zone (urban vs. semi-urban), and field of study (science, humanities, business). The sample size was determined using a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5% (Cochran, 1977).

5.7. Data Collection Procedures

5.7.1. Qualitative Data

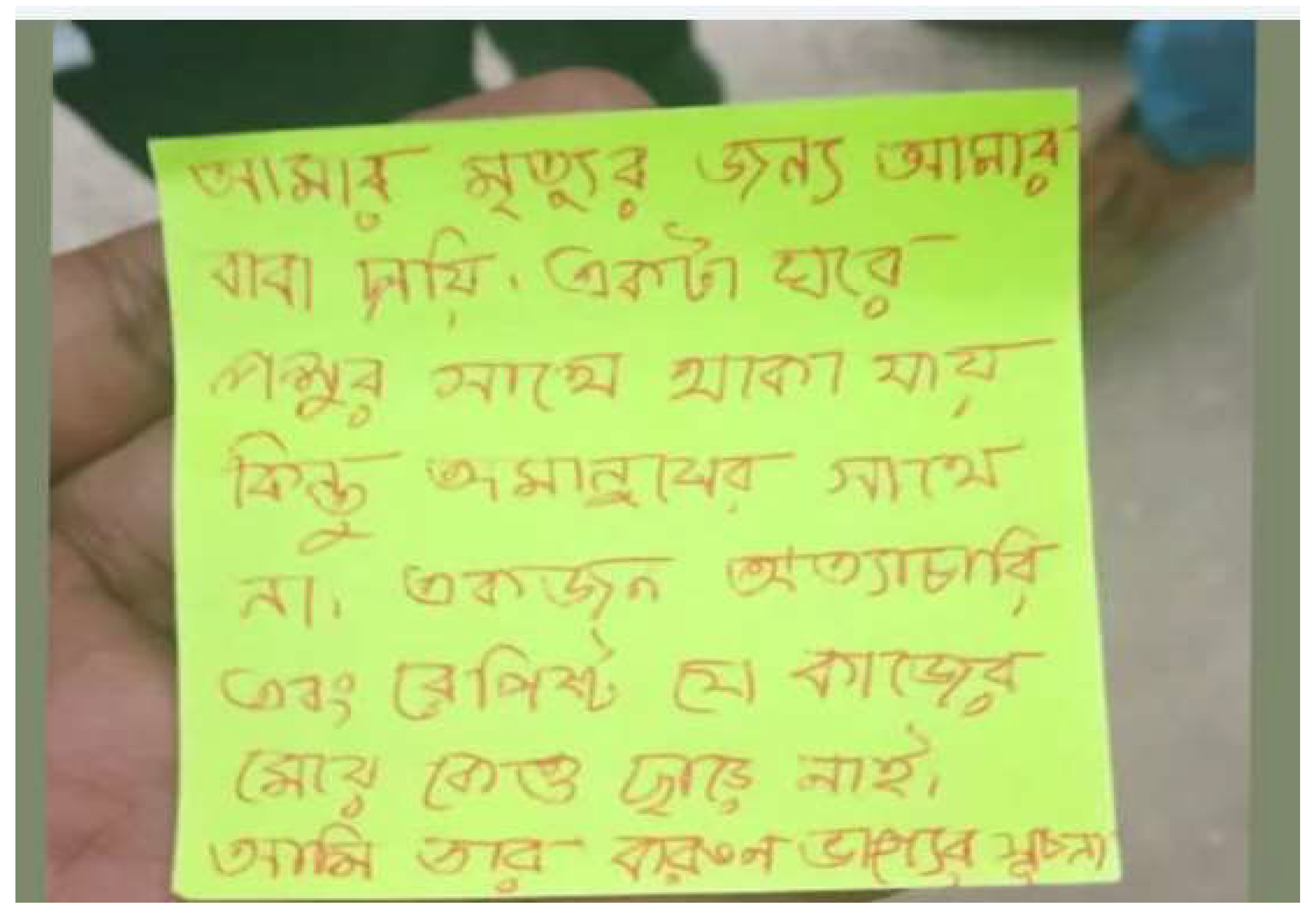

Suicide Notes: A total of 30 social media suicide notes were coded and anonymized to remove identifiable information. Each note was read, translated if necessary (Bangla to English), and analyzed using NVivo 12 software for thematic coding.

Interviews: In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 friends, classmates, and family members of deceased students who had posted suicide-related content online.

Digital Ethnography: Observations were conducted in selected Telegram and WhatsApp groups related to university students, where suicide discussions or condolence messages appeared.

5.7.2. Quantitative Data

A structured online questionnaire consisting of 35 questions (both closed and Likert-scale) was distributed via Google Forms. The questionnaire measured:

Frequency and nature of suicidal thoughts, History of posting emotional or suicidal content, Attitudes toward mental health support, Experience with cyberbullying or romantic breakups, Gendered perceptions of emotional expression.

The instrument was pre-tested with 50 students for face validity and revised accordingly.

5.8. Data Analysis Techniques

5.8.1. Qualitative Analysis

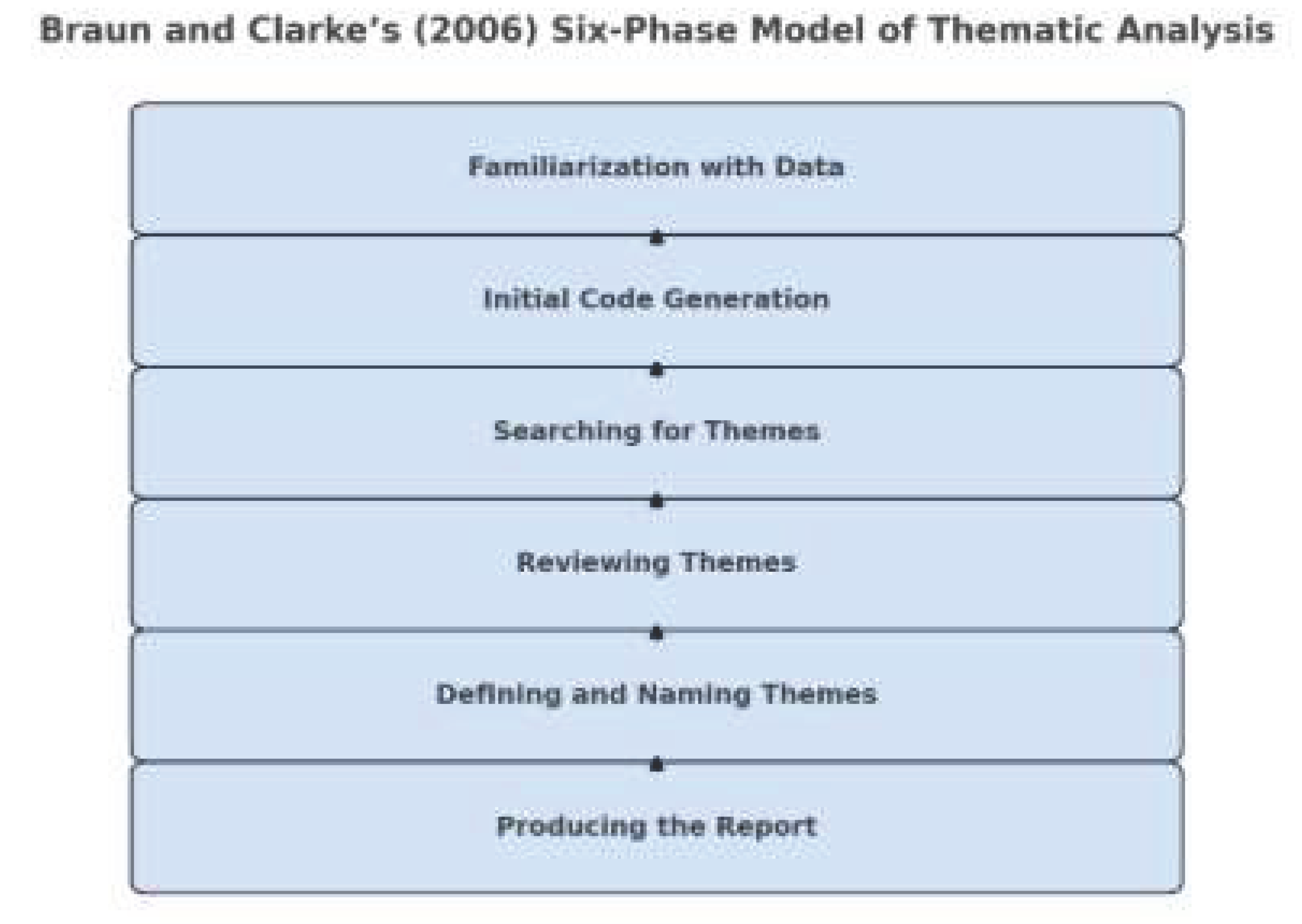

Thematic analysis was used to identify recurring patterns and emotional themes in the suicide notes and interview transcripts. Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase model was followed:

Coding categories included: ‘Familial Pressure,’ ‘Romantic Disillusionment,’ ‘Academic Failure,’ ‘Public Shame,’ ‘Apology and Redemption,’ and ‘Last Words.’

5.8.2. Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS version 26. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequency) were computed to understand general trends. Inferential tests such as chi-square tests and independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine gender differences in suicidal behavior and expression. Correlation and regression analyses were used to identify predictors of online suicidal expressions.

5.9. Ethical Considerations

Given the sensitivity of the research topic, strict ethical protocols were followed. The study received formal approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of University of Rajshahi. Informed consent was obtained from all interviewees and survey participants. For deceased individuals, consent was obtained from next-of-kin or legal guardians where possible.

All data were anonymized to protect identities. Suicide notes were paraphrased or partially quoted to avoid triggering or sensational content. A team of clinical psychologists was on standby during the data collection phase to offer mental health support to participants who exhibited distress.

5.10. Limitations of the Methodology

Despite its rigor, the methodology has certain limitations:

Suicide notes analyzed may not be representative of all cases due to digital access barriers and deletions by families.

Social desirability bias may have affected survey responses, especially regarding sensitive topics like mental illness and suicide attempts.

The cross-sectional nature of the study restricts causal interpretation.

The research focuses primarily on university students, professionals and does not include other young populations such as madrasa students, vocational learners, or unemployed youth.

This mixed-methods methodology allowed the research to investigate the phenomenon of digital suicidal communication from both interpretive and statistical perspectives. By examining the content, context, and reception of social media suicide notes among male and female students in Bangladesh, the study offers critical insights into a growing public health crisis shaped by digital cultures, gender norms, and psychological vulnerabilities.

7. Discussion and Implications

7.1. Discussion

This study's findings shed critical light on the gendered nature of suicidal expression among Bangladeshi university students on social media platforms. The differences in how male and female students articulate distress, seek support, and experience social responses align with global research on gender and suicide but are also deeply embedded within Bangladesh’s unique socio-cultural context.

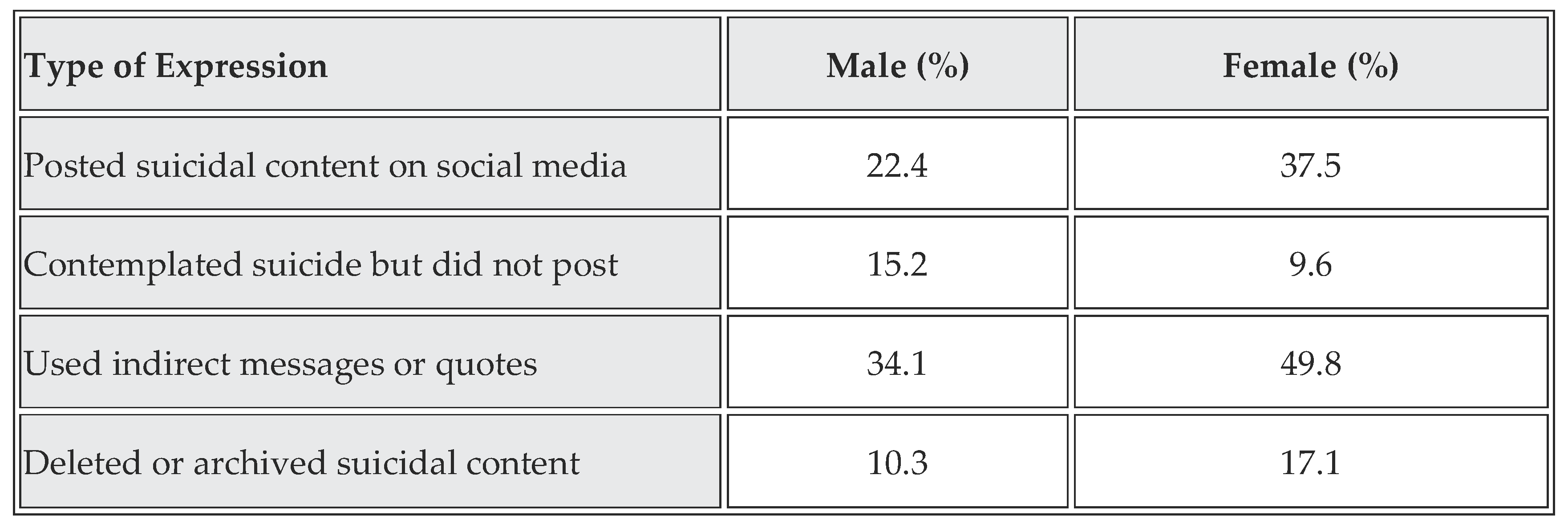

The quantitative data revealed that female students tend to be more expressive online about their suicidal thoughts, often posting detailed, emotionally charged content. This corroborates previous findings indicating females’ greater verbal and emotional expressiveness (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012). Males, conversely, were more likely to suppress direct expression but exhibited suicidal ideation internally, consistent with Joiner’s (2005) theory of male suicidal concealment due to stigma and traditional masculinity norms.

The qualitative analyses of suicide notes further nuanced these findings. Females articulated distress through relational language focused on shame, social judgment, and desire for forgiveness. This relational orientation reflects Bangladesh’s collectivist culture, where social harmony and familial reputation are paramount (Hofstede Insights, 2024). Males’ notes revealed themes of failure and economic pressures, mirroring the gendered expectations placed on men as providers and protectors (Connell, 2005).

Temporal and contextual patterns suggest that suicidal posts are influenced by emotional rhythms, with nighttime posting aligning with feelings of isolation and vulnerability. Female students’ posts were more immediately responded to with empathy and mobilization, while male posts often encountered dismissiveness or silence, reinforcing the gendered gap in emotional support online.

Importantly, the role of digital platforms emerged as a key mediator in how suicidal ideation is communicated and received. Female students preferred mainstream social media that allow expressive narratives (e.g., Facebook, Instagram), whereas males favored more anonymous or closed-group platforms where indirect or symbolic communication is more feasible. This finding highlights the need for platform-specific mental health interventions.

7.2. Implications

7.2.1. Gender-Sensitive Mental Health Interventions

The divergent ways in which male and female students in Bangladesh express and experience suicidal ideation underscore the critical need for gender-sensitive mental health interventions. Traditional ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches to suicide prevention risk overlooking nuanced gender differences in help-seeking behaviors, emotional expression, and social stigma, potentially reducing intervention effectiveness (Kuehner, 2017).

Interventions for Female Students

Female students generally exhibit greater emotional expressiveness and tend to use social media as a platform for verbalizing distress, sharing intimate experiences, and seeking social support (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012). Mental health programs targeting females should leverage this openness by incorporating modalities that promote narrative expression and community support.

Online Peer Support Groups: These provide safe spaces for females to discuss mental health issues without fear of judgment, fostering a sense of belonging and reducing feelings of isolation. Peer-led online forums have demonstrated efficacy in reducing depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation by enhancing social connectedness (Naslund et al., 2016).

Narrative Therapy and Expressive Writing: Facilitating structured opportunities for females to write or talk about their emotions can promote cognitive reappraisal and emotional regulation, which are protective against suicidal behaviors (Pennebaker & Seagal, 1999). Digital platforms can host moderated sessions or journaling apps designed to guide users through therapeutic self-expression.

Addressing Cyberbullying and Social Stress: Given that females’ suicide notes and posts frequently mention relational stress and social judgment, interventions must include psychoeducation about cyberbullying and social media pressures. Programs can teach coping strategies such as digital literacy, self-compassion, and boundary setting (Wang et al., 2019).

Interventions for Male Students

Male students tend to conceal emotional distress due to societal expectations surrounding masculinity, often resulting in indirect or nonverbal communication of suicidal ideation (Seidler et al., 2016). Consequently, male-focused interventions must create alternative avenues for expression and dismantle help-seeking stigma.

Anonymous Counseling Services: Telephonic and online counseling platforms that allow anonymity can lower barriers for males reluctant to disclose mental health struggles openly (Johnson et al., 2012). Confidentiality can encourage candid discussion of sensitive topics such as depression, financial stress, or suicidal thoughts.

Gamification and Engagement Tools: Mental health apps employing gamification elements appeal to young males by framing psychological self-care as skill-building or problem-solving activities rather than therapy. Evidence suggests that such tools increase engagement and reduce attrition among male users (Hirvikoski et al., 2017).

Challenging Toxic Masculinity Norms: Educational campaigns and workshops that promote alternative masculinities—emphasizing emotional openness, vulnerability, and seeking help—can reduce the shame associated with mental illness in males (Mahalik et al., 2003). Collaborations with male role models and community leaders can amplify these messages.

Recognizing Indirect Expressions: Training mental health professionals, educators, and peer supporters to interpret nonverbal or symbolic indicators such as memes, coded language, or behavioral changes is crucial for early detection and intervention among males (Cleary, 2016).

Family and Community Involvement

Across genders, family dynamics emerged as a central theme in suicidal expression. In the collectivist Bangladeshi context, family acceptance and support play pivotal roles in mental health outcomes (Rahman et al., 2020).

Psychoeducation for Families: Programs aimed at parents and guardians can raise awareness about adolescent mental health, dismantle myths about suicide, and teach supportive communication techniques. Evidence from South Asian contexts indicates that family-inclusive interventions improve help-seeking rates and reduce stigma (Kumar & Steer, 2019).

Community Gatekeeper Training: Empowering teachers, religious leaders, and community health workers to recognize signs of distress and facilitate referrals to professional services can create a safety net for vulnerable youth (Flicker et al., 2015).

Cultural Sensitivity and Contextualization

All interventions must be culturally attuned to Bangladesh’s socio-religious fabric, where discussions of mental illness and suicide are often taboo (Islam & Griffiths, 2019). Incorporating local languages, respecting religious sentiments, and utilizing culturally resonant narratives enhance acceptance and effectiveness.

7.2.2. Digital Policy and Platform Recommendations

Social media companies operating in Bangladesh and similar contexts must adopt proactive policies to identify and intervene in suicidal expressions:

Algorithmic Detection with Gender Sensitivity: Automated detection systems should incorporate linguistic nuances that differ by gender, including symbolic content preferred by males and emotional narratives preferred by females. This can improve the accuracy of flagging posts for review (Chancellor et al., 2020).

Crisis Response Integration: Platforms should integrate direct links to culturally appropriate helplines and mental health resources when suicidal content is detected, ensuring responses respect gendered communication styles.

Moderation Training: Content moderators need specialized training to avoid dismissive responses that exacerbate male users’ isolation and to recognize subtler forms of distress (e.g., memes, song lyrics).

Privacy and Anonymity Controls: Given males’ preference for anonymous or closed groups, platforms should offer privacy tools that protect users while enabling help access, balancing confidentiality and safety.

7.2.3. Psycho-Social Recommendations

Curriculum Integration: Universities should integrate mental health literacy, emotional regulation, and digital citizenship education into their curricula. These programs can destigmatize mental health struggles and teach safe social media use.

Community-Based Awareness: Campaigns should use culturally resonant messaging, utilizing local languages, religious frameworks, and youth influencers to address suicidal stigma and promote open conversations.

Research and Monitoring: Continued longitudinal research is needed to monitor the evolving patterns of online suicidal expression, especially with emerging platforms popular among youth in Bangladesh.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study offers valuable insights, limitations must be acknowledged. The self-reported nature of survey data may introduce bias. Suicide notes analyzed were limited in number and may not represent all cases. Future research should expand sample size, include rural populations, and employ mixed methods incorporating ethnographic approaches.

Furthermore, intersectional factors such as socio-economic status, urban-rural divide, and sexual orientation warrant deeper exploration to understand their role in suicidal ideation and online behaviors.

7.4. Conclusion

This study underscores the complex, gendered dynamics of suicidal expression on social media among Bangladeshi university students. The findings highlight that effective suicide prevention in digital spaces requires gender-sensitive, culturally contextualized approaches spanning mental health interventions, digital policy reforms, and psycho-social education.

By embracing these tailored strategies, stakeholders can foster safer online environments that not only detect distress but also provide meaningful support, ultimately contributing to the reduction of youth suicide in Bangladesh. This research provides vital implications for suicide prevention strategies tailored to the digital habits and emotional profiles of male and female students in Bangladesh. It urges educational institutions, mental health practitioners, and policymakers to develop gender-sensitive intervention models that integrate digital literacy, peer counseling, and AI-based monitoring systems to detect and address early signs of suicidal ideation.