Submitted:

25 May 2025

Posted:

27 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Gaps and Contribution

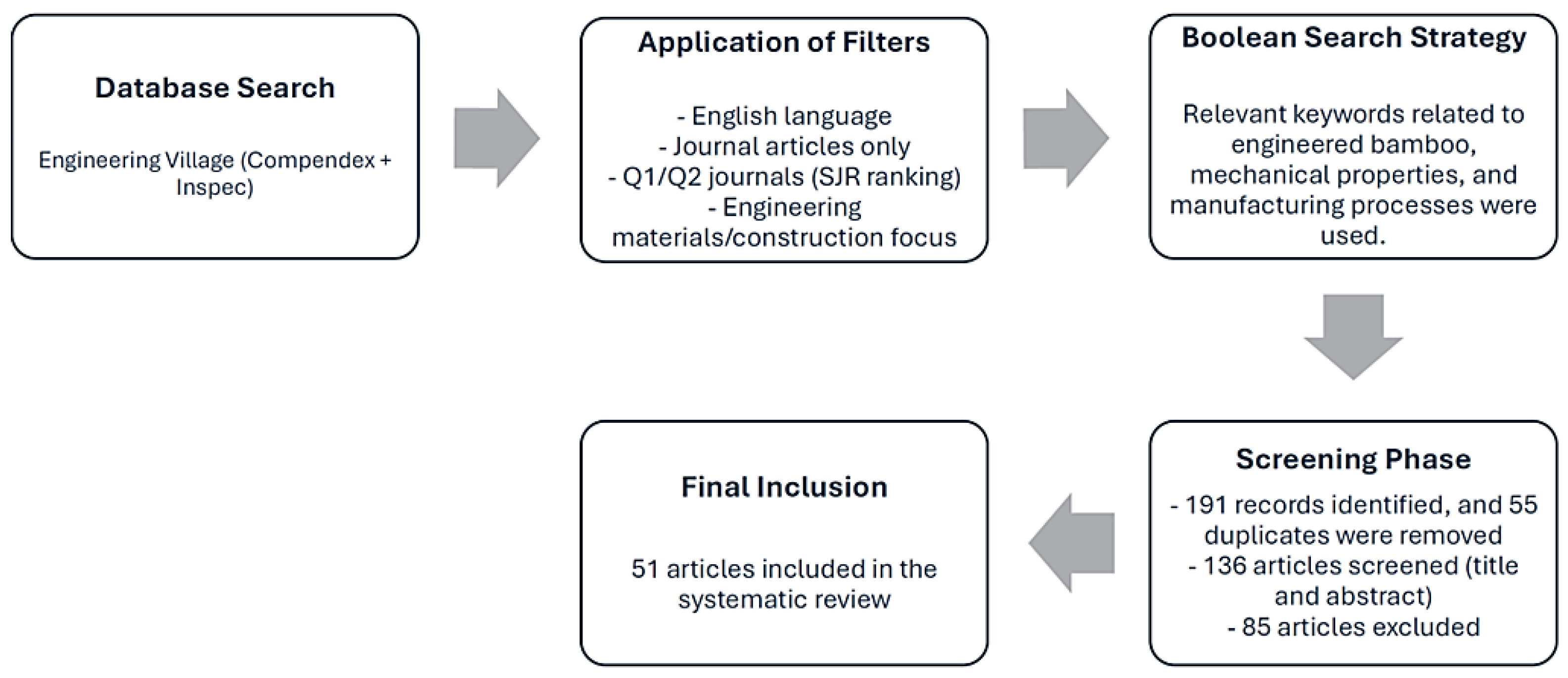

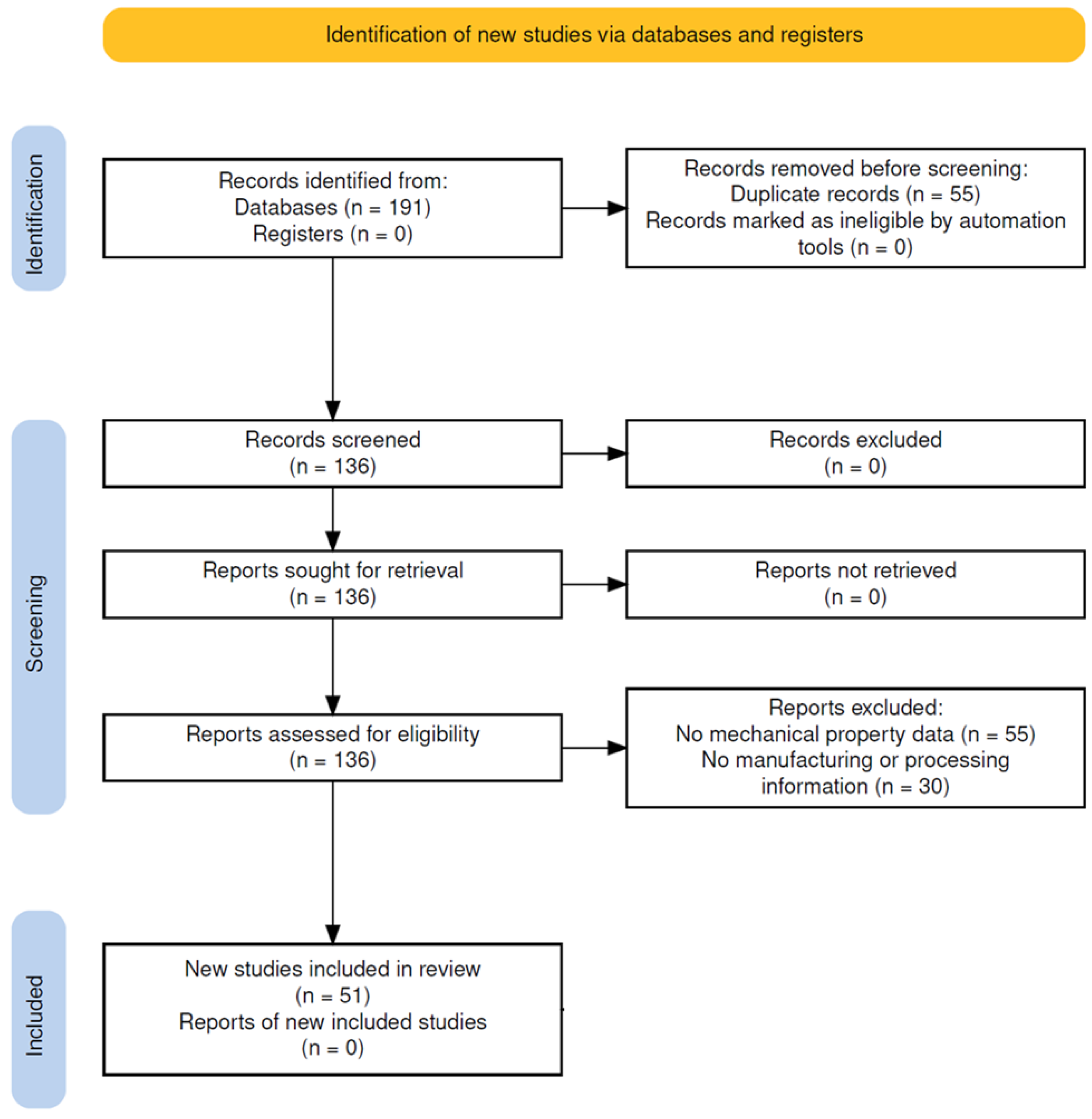

2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mechanical Properties

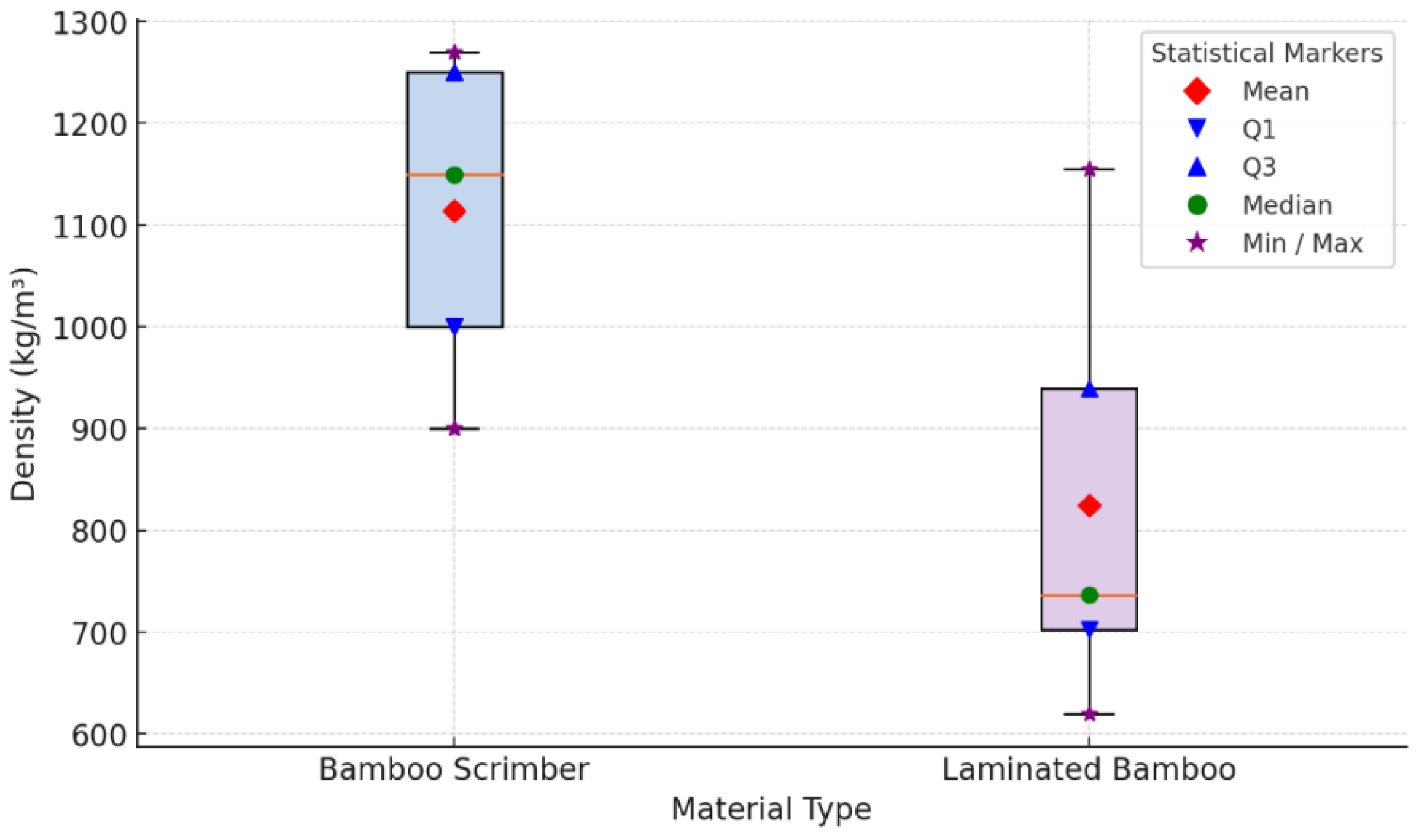

3.1.1. Density

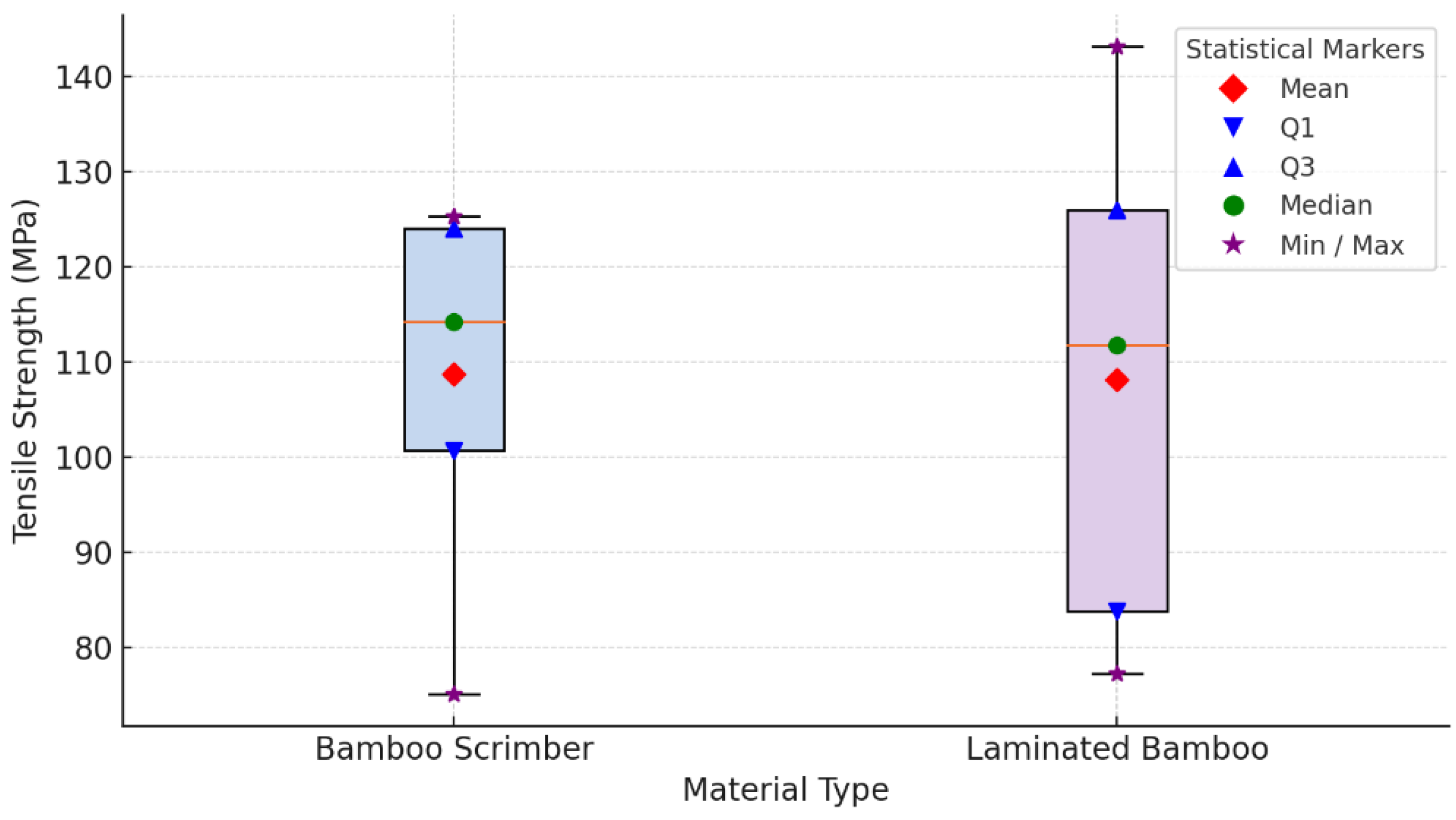

3.1.2. Tensile Strength

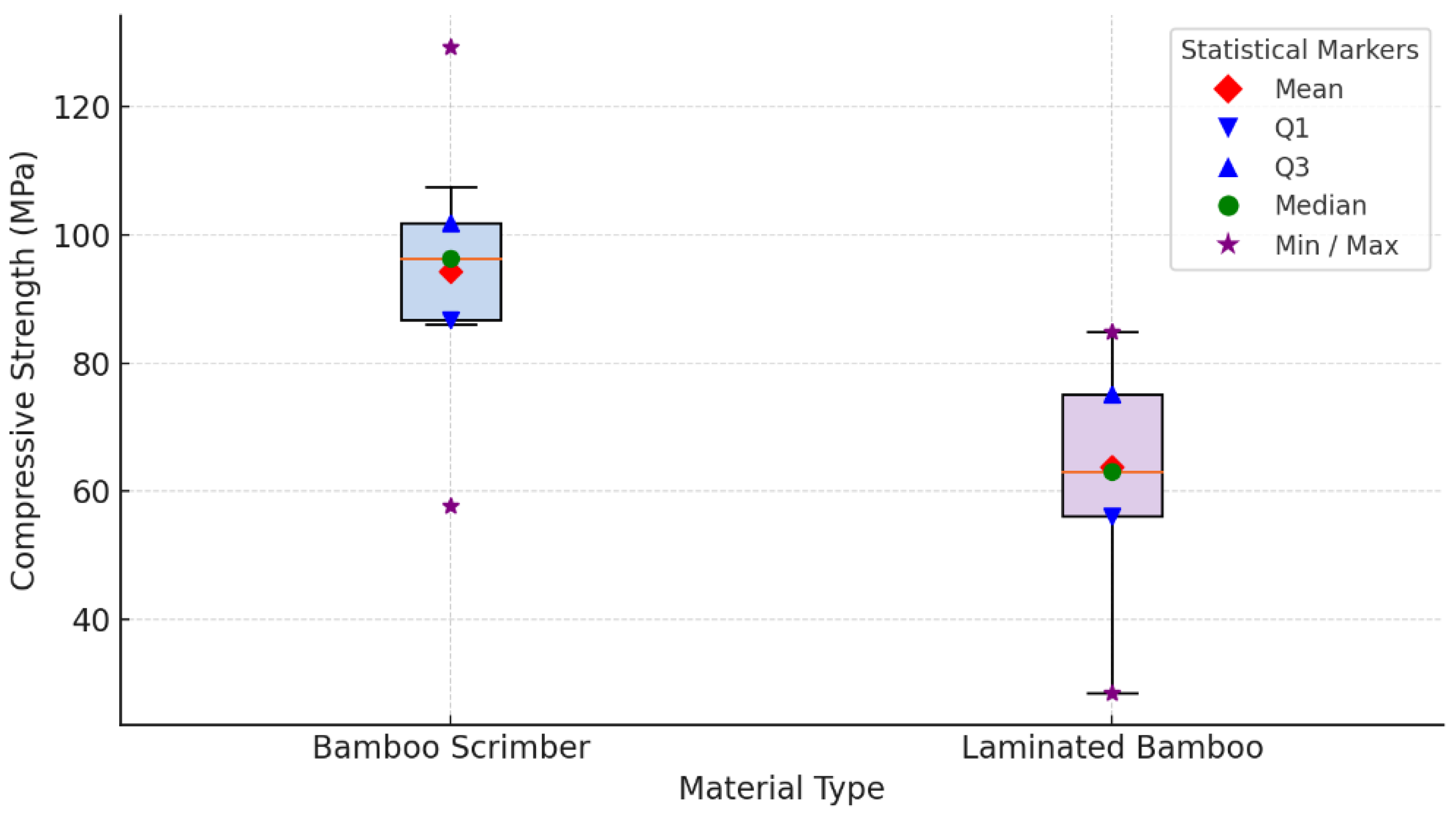

3.1.3. Compressive Strength

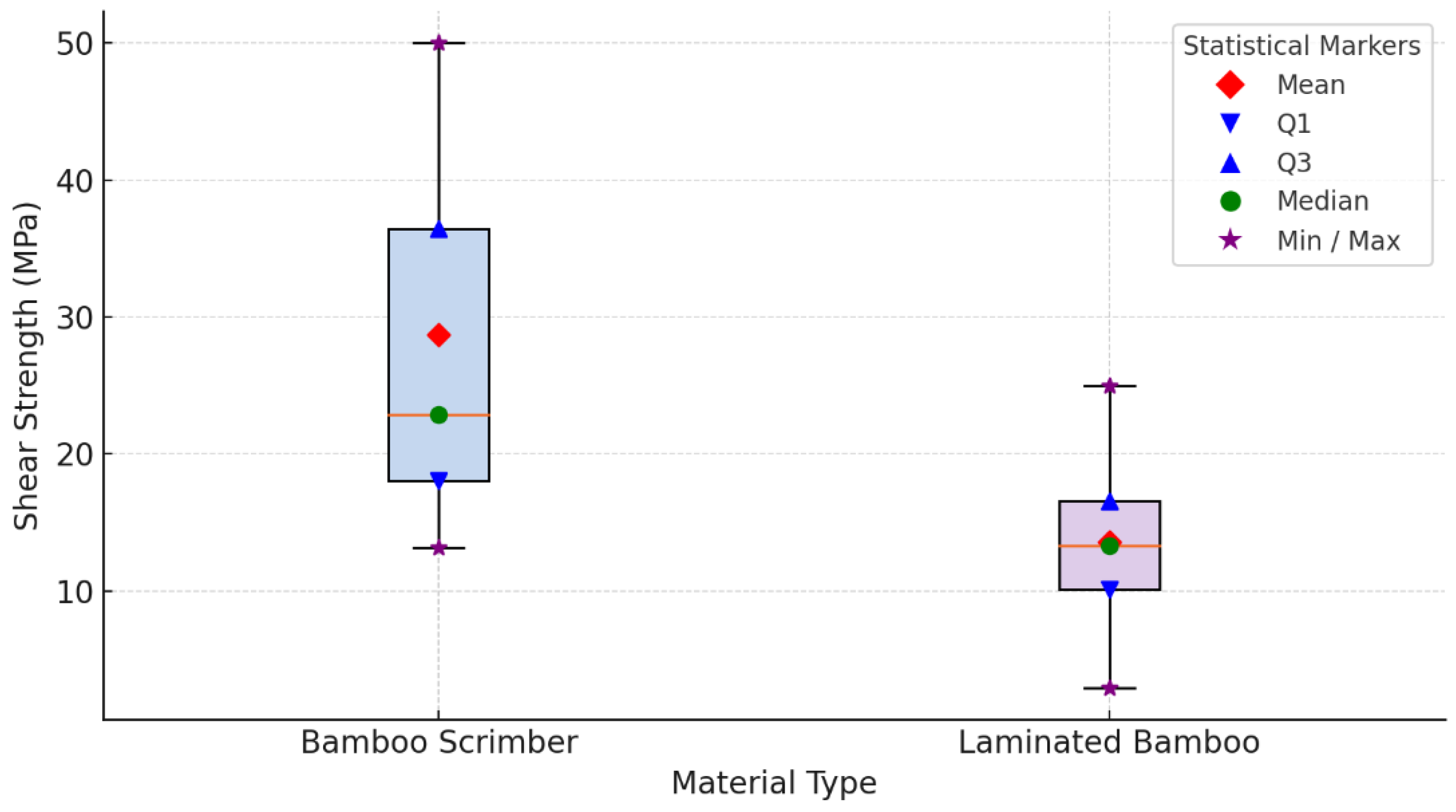

3.1.4. Shear Strength

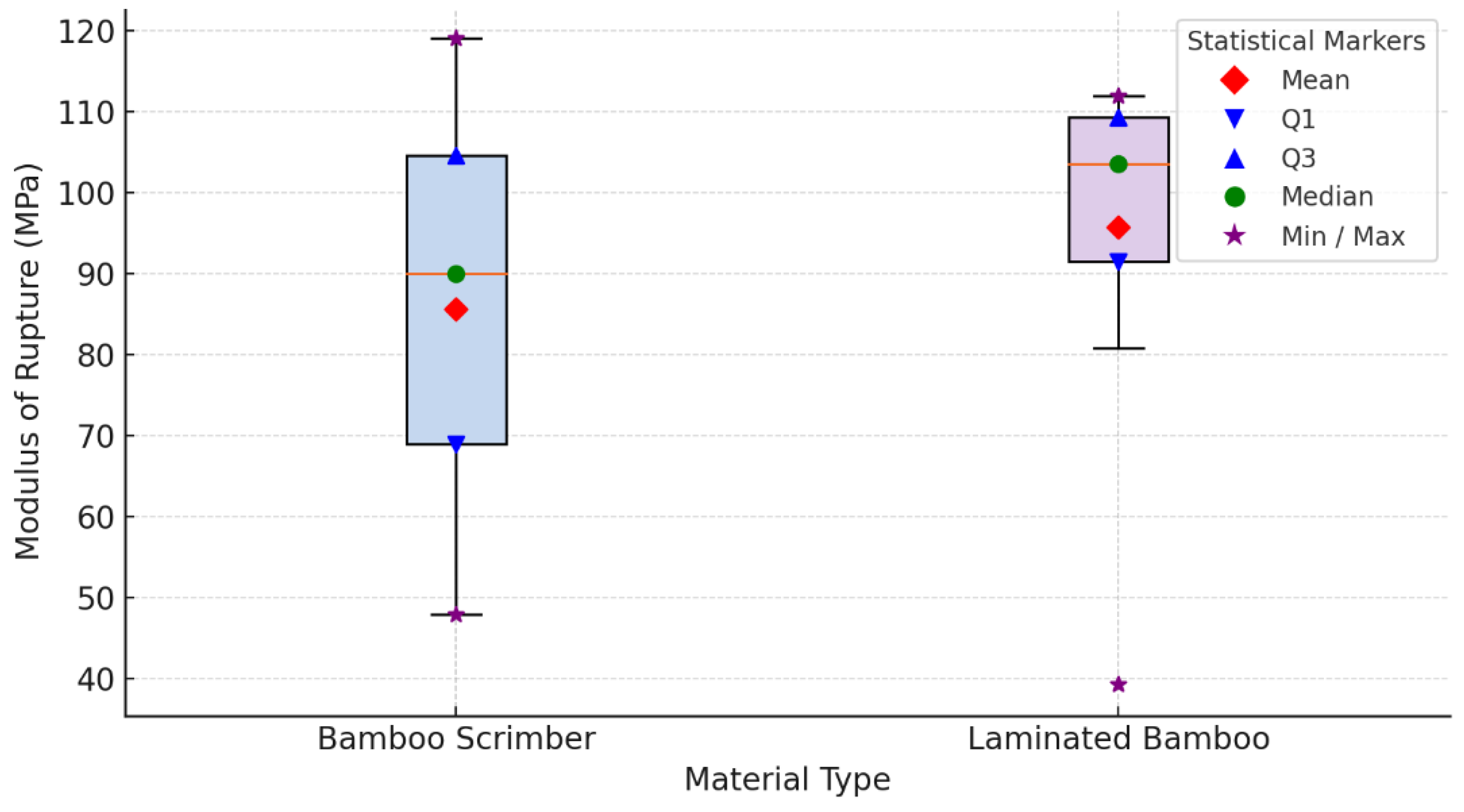

3.1.5. Modulus of Rupture

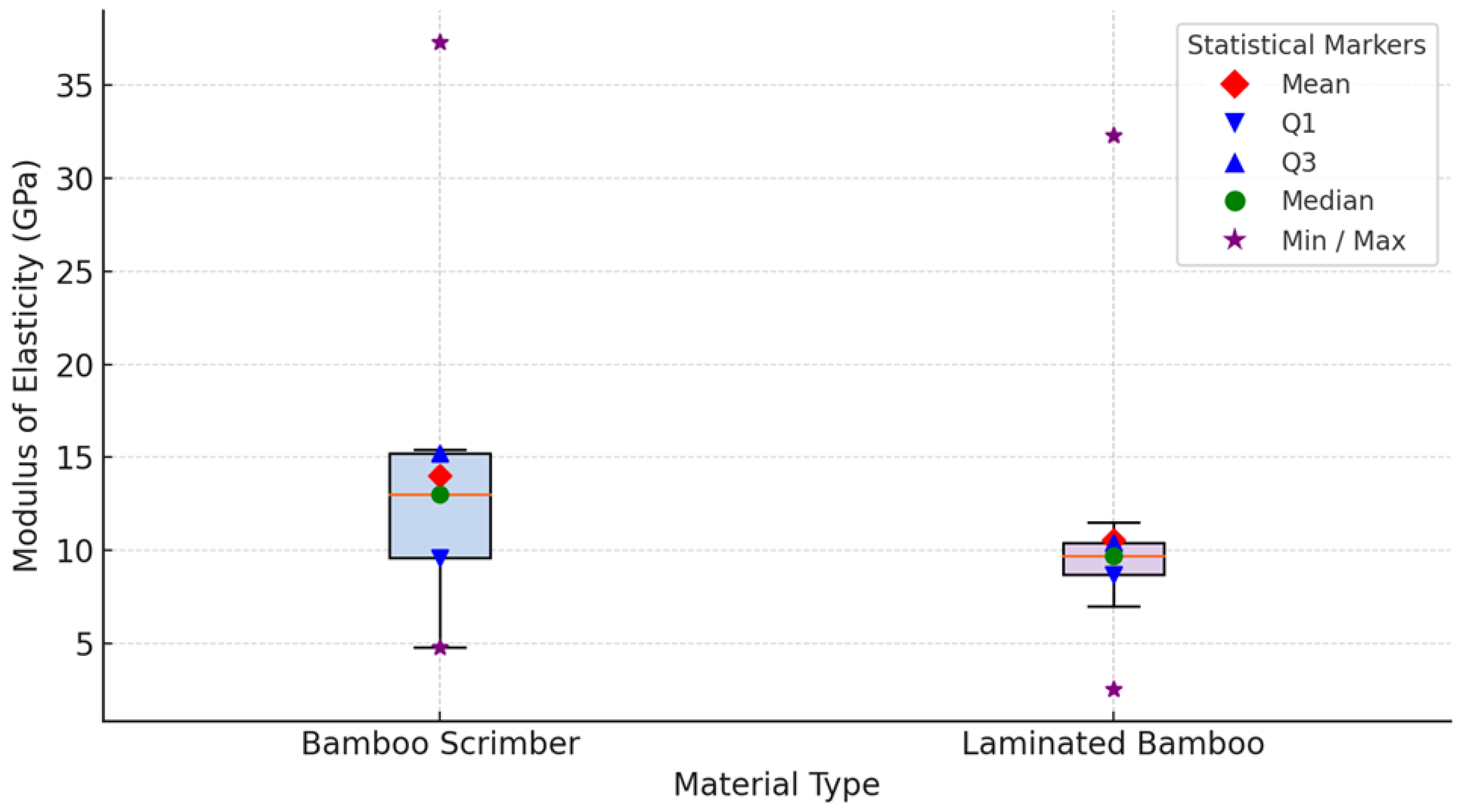

3.1.6. Modulus of Elasticity

3.1.7. Durability

| Article | Bamboo Species | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Shear Strength (MPa) | Modulus of Rupture (MPa) | Modulus of Elasticity (GPa) |

| [10] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Scrimber: 87.4; Laminated: 68.7 | Scrimber: 75.1; Laminated: 69.3 | Not Reported | Not Reported | Scrimber: 9.8; Laminated: 9.8 |

| [24] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | 84.9 | 111.7 | 12.1 | 111.9 | 9.2 |

| [11] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Parallel Strand Bamboo: 99.3-119.0; Laminated Veneer Bamboo: 55.9-69.2 | Parallel Strand Bamboo: ~125; Laminated Veneer Bamboo: ~110 | Parallel Strand Bamboo: ~13.5; Laminated Veneer Bamboo: ~12.0 | Parallel Strand Bamboo: up to 130; Laminated Veneer Bamboo: ~112 | Parallel Strand Bamboo: 11.5-13.8; Laminated Veneer Bamboo: 8.5-11.6 |

| [39] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | 59.74 (ultimate) | 77.18 (ultimate) | - | Not Reported | Tension: 7.78; Compression: 9.98 |

| [27] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) + Douglas fir | Bamboo: 96.35; Timber: 51.23 | Bamboo: 125.28; Timber: 117.85 | Not Reported | Not Reported | Bamboo: 15.43 (compression), 15.10 (tension); Timber: 12.57 (compression), 14.76 (tension) |

| [41] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | 84.9 | 111.7 | Not Reported | 111.9 | 9.19 |

| [2] | Phyllostachys heterocycla (BMCP) + Hem-fir lumber | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | 31.3-32.6 | 6.27 |

| [42] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | 75.1 (0°), 27.2 (60°) | Not Reported | 13.0 (15°), 14.5 (45°), varies with angle | Not Reported | 9.91 (0°), 2.43 (60°), varies with angle |

| [40] | Not specified | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported |

4.80-9.46 (span dependent) |

| [29] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis), bamboo scrimber | 129.25 (parallel), 65.77 - 73.34 (perpendicular) | 108.45 (parallel), 7.62 (perpendicular) | 22.91 (parallel), 20.89 - 31.68 (perpendicular) | Not reported | 13.52 (tensile, parallel), 12.32 (compressive, parallel), 2.75 (tensile, perpendicular), 2.99 (compressive, perpendicular) |

| [30] | Dendrocalamus giganteus | 63.07 - 80.80 | Not Reported | 2.96 - 6.32 | 88.24 - 150.65 (bending) | 11.51 - 12.11 |

| [35] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Not Reported | 83-119 | Not Reported | An estimated 104 MPa for glubam | 10.34-10.71 |

| [25] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | 86 (parallel), 37 (perpendicular) | 120 MPa (parallel), 3 MPa (perpendicular) | Not Reported | 119 MPa (approx) | 13 |

| [43] | Not stated | 68.8 (mean) | 84.53 (mean) | Not Reported | Not Reported | 7.007 (tensile), 9.393 (compressive) |

| [44] | Phyllostachys (4-5 years old, >100 mm diameter) | 28.64 | 123.82 | Not Reported | Not Reported | 8.52 |

| [33] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | 173.94-174.41 | 11.92-12.73 |

| [34] | Phyllostachys spp. + Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) | 107.5 (bamboo scrimber), 38.6 (Chinese fir) | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | 9.393 (compressive bamboo), 7.007 (compressive fir) |

| [26] | Guadua angustifolia Kunth | 62.0 (parallel), 3.5 (radial), 5.3 (tangential) | 143.1 (parallel), 2.6 (radial), 3.2 (tangential) | 9.5 | 103.0 (radial), 122.4 (tangential) | 32.3 (compressive), 18.3 (tensile), 12.7-13.3 (flexural) |

| [45] | Bamboo scrimber + SPF (Spruce-Pine-Fir) | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | 9.4-13.7 |

| [46] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Not Reported | 98-124 | Not Reported | Not Reported | ↑37.3% over ordinary scrimber |

| [28] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Not Reported | 128.2 (0°); 52.1 (15°); down to 8.1 (90°) | Not Reported | Not Reported | 11.29 GPa (0°); 2.37 GPa (90°) |

| [47] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | 107.2 MPa (average) | 10.0 GPa |

| [48] | Julong bamboo (Dendrocalamus giganteus) | 71.4 (longitudinal), 22.7 (transverse) | 66.8 (longitudinal), 5.7 (transverse) | Not Reported | 70.9 MPa | 10.3 GPa (bending) |

| [37] | Gigantochloa spp. | 57.7 | 34.3 | 13.2 | 47.9 MPa | 8.9 (bending), 8.4 (longitudinal), 3.6 (transverse) |

| [49] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Approx. 100-110 MPa depending on type | Not reported |

| [18] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Bamboo scrimber: 84; Laminated bamboo: 79 | Bamboo scrimber: 136, Laminated bamboo: 122 | Not Reported | Up to 110 MPa | 10.5-12.0 |

| [12] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | 56.2 (longitudinal), 43.1 (radial), 19.0 (tangential) | 106.9 (longitudinal), 1.8 (radial), 4.3 (tangential) | 17.3 (parallel to grain) | 80.8 | 9.5 (longitudinal), 0.58 (radial), 1.12 (tangential) |

| [50] | Bamboo scrimber + Douglas Fir | 96.35 (Bamboo scrimber); 51.23 (Douglas Fir) | 125.28 (Bamboo scrimber); 117.85 (Douglas Fir) | Not Reported | Not Reported | 15.43 (Bamboo scrimber, compression), 12.57 (Douglas Fir, compression) |

| [38] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | 68 (parallel); 15 (tangential); 13 (radial) | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | 8.75 (parallel); 2.19 (tangential); 1.11 (radial) |

| [3] | PBSL from Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Avg: 44.34-61.08 depending on angle | Avg: 21.56-71.78 depending on angle | Not Reported | 39.32-82.49 (as bending strength) | 2.56-8.31 depending on test direction |

| [51] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Not Reported | Not Reported | - | Approx. 90-120 | - |

| [31] | - | Thin-strip: 51.0; Thick-strip: 73.0 | Thin-strip: 83.0; Thick-strip: 85.0 (longitudinal) | Thin-strip: 16; Thick-strip: 17.5 | Thin-strip: 101.1; Thick-strip: 104.9 | Thin-strip: 10.4-11.3; Thick-strip: 9.0-10.5 |

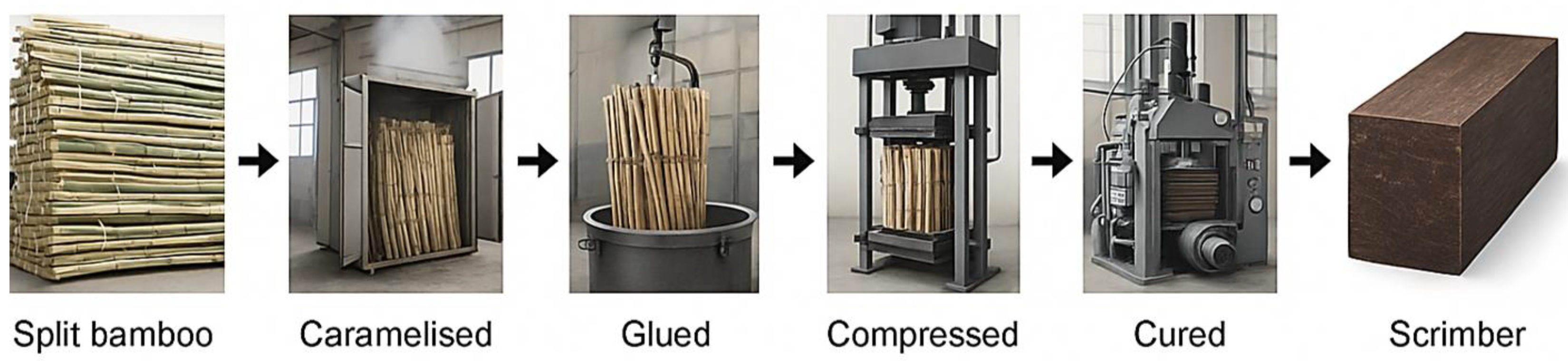

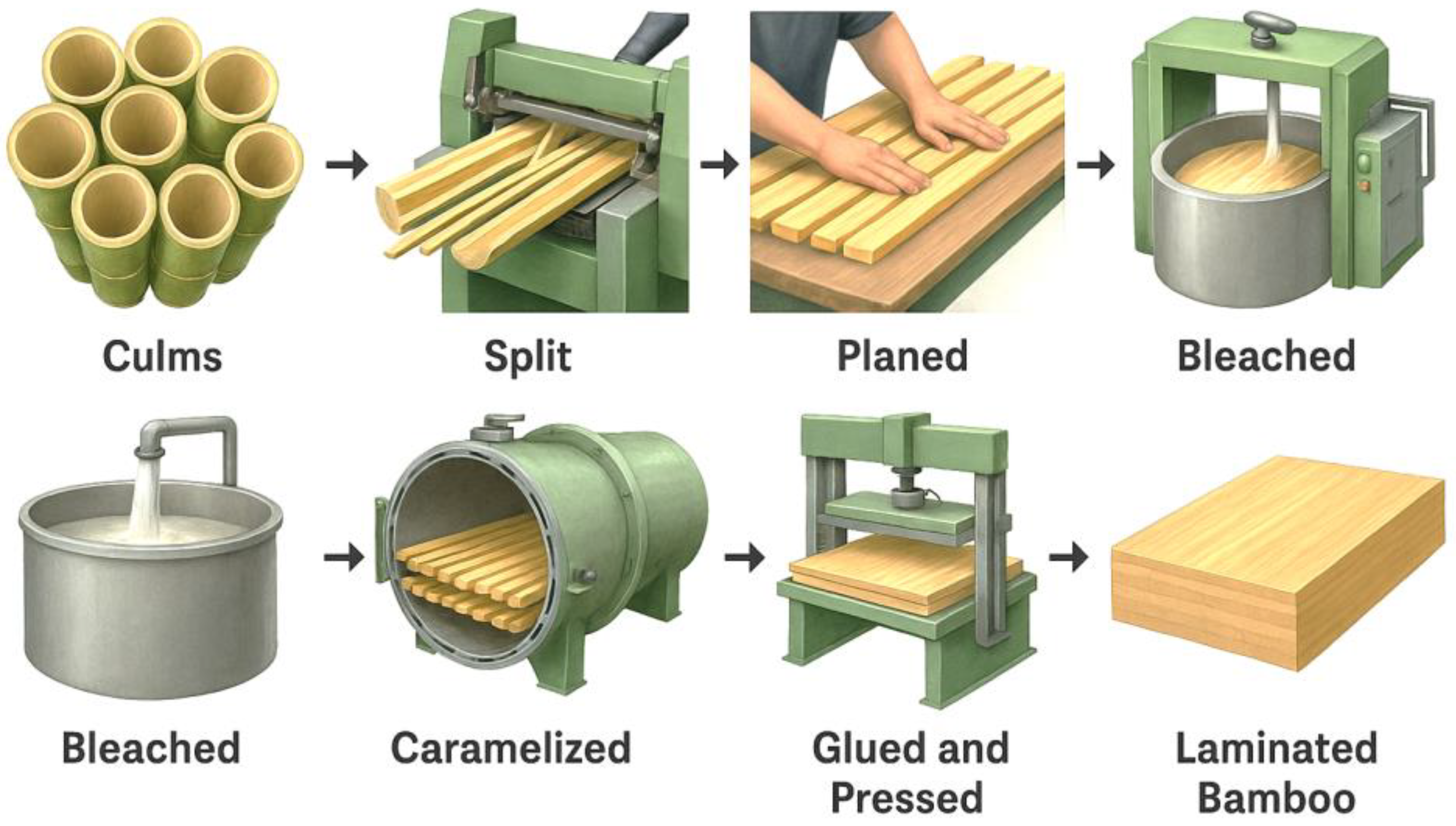

3.2. Manufacturing and Processing Methods

3.2.1. Adhesive Types and Performance

3.2.2. Processing and Treatment Methods

3.2.3. Hot Pressing Conditions

| Reference | Bamboo Species | Adhesive/Binder Used | Product Type |

| [2] | Not specified | Phenolic Formaldehyde Resin | Glubam Beams (Thick and Thin Plybamboo boards) |

| [3] | Not specified, presumably Moso | Phenolic Resin (15--20% weight) | Cross-Laminated Bamboo (CLB) |

| [6] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | None at EASB stage (adhesive for later use not applied yet) | Equal-Arc Shaped Bamboo Splits (EASB) |

| [2] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Phenol Formaldehyde (PF) Resin (17 wt%) | Bamboo Scrimber Composite (BSC) |

| [16] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Phenolic Resin (13% weight) | Bamboo Scrimber (BS) |

| [58] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | No adhesive at unit stage (future lamination possible) | Equal-Arc Shaped Bamboo Splits (EASB) |

| [61] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) and Chinese fir | No adhesives. mechanical nailing only | Nail-Laminated Bamboo-Timber (NLBT) Panels |

| [53] | Ater bamboo (Gigantochloa atter) | Water-Based Polymer Isocyanate (WBPI) adhesive | Laminated Bamboo Esterilla Sheet (LBES) |

| [54] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Polyurethane wood adhesive (Lumber Jack 5 Min) | Laminated Bamboo Composites (Single-ply and Two-ply) |

| [52] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) and European Spruce (C18 grade) | Phenol-Resorcinol adhesive for bamboo panels. Water-based polyurethane structural adhesive for bamboo-timber lamination | Prestressed Laminated Bamboo-Timber Composite Beam |

| [55] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Phenol-Formaldehyde (PF) resin (solid content 18%) | Bamboo Scrimber (BS) |

| [56] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Phenol-Formaldehyde (PF) resin (solid content ~20% after dilution) | Knitted Bamboo Scrimber (KBS) and Commercial Hot-Pressed Bamboo Scrimber (CBS) |

| [62] | Neosinocalamus affinis | Phenol-Formaldehyde (PF) resin (diluted to 30% solid content) | Laminated Bamboo-Bundle Veneer Lumber (BLVL) |

| [64] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Phenol-Formaldehyde (PF) resin (solid content >47%) | Bamboo-Wood Composite (GFBW Composite) |

| [63] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) and Guadua (Guadua angustifolia) | Flange panels: Urea-formaldehyde. OSB: Phenol-formaldehyde. Finger joints: Epoxy resin (West Systems 105/206) | Engineered Bamboo I-Joists |

| [57] | Bamboo species not specified | Water-soluble phenolic resin modified with melamine (solid content ~23.5%) | High-Strength Laminated Bamboo Composite |

| [59] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) and Makino bamboo (Phyllostachys makinoi) | Water-soluble Urea-Formaldehyde (UF) resin (solid content 63.6%) | Oriented Bamboo Scrimber Boards (OBSB) |

| [23] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Phenol-Formaldehyde (PF) resin (solid content 46.56%) | Wide-Bundle Bamboo Scrimber (WBS) |

| [60] | Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) | Phenol-Formaldehyde (PF) resin (solid content 29%) | Overlaid Laminated Bamboo Lumber (OLBL) |

4. Conclusion and Recommendation for Future Research

4.1. Future Research Needs

4.2. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Drury, B., Padfield, C., Russo, M., Swygart, L., Spalton, O., Froggatt, S., and Mofidi, A. (2023). Assessment of the Compression Properties of Different Giant Bamboo Species for Sustainable Construction. Sustainability. 15(8), 6472. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Yang, G. S., Zhou, Q., Shan, B., & Xiao, Y. (2019). Bending performance of glubam beams made with different processes. Advances in Structural Engineering, 22(2), 535-546. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z., Zhu, W., & Fan, H. (2023). Anisotropy attenuation of reconstituted bamboo lumber by orthogonal layup process. Composites Communications, 40, 101608. [CrossRef]

- Mofidi, A., Abila, J., & Ng, J. T. M. (2020). Novel advanced composite bamboo structural members with bio-based and synthetic matrices for sustainable construction. Sustainability, 12(6), 2485. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, C., and Mofidi, A. (2021). Non-Linear Numerical Modelling of Sustainable Advanced Composite Columns Made from Bamboo Culms. Construction Materials, 1(3), 169-187. [CrossRef]

- Huang, B., Chen, L., Wang, X., Ma, X., Liu, H., Zhang, X., ... & Fang, C. (2023). Eco-friendly, high-utilization, and easy-manufacturing bamboo units for engineered bamboo products: Processing and mechanical characterization. Composites Part B: Engineering, 267, 111073. [CrossRef]

- Drury, B., Padfield, C., Rajabifard, M., & Mofidi, A. (2024). Experimental Investigation of Low-Cost Bamboo Composite (LCBC) Slender Structural Columns in Compression. Journal of Composites Science, 8(10), 435. [CrossRef]

- Adier, M. F. V., Sevilla, M. E. P., Valerio, D. N. R., & Ongpeng, J. M. C. (2023). Bamboo as Sustainable Building Materials: A Systematic Review of Properties, Treatment Methods, and Standards. Buildings, 13(10), 2449. [CrossRef]

- Padfield, C., Drury, B., Soltanieh, G., Rajabifard, M., and Mofidi, A. (2024) Innovative Cross-sectional Configurations for Low-Cost Bamboo Composite (LCBC) Structural Columns. Sustainability, 16(17), 7451. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y., Zhou, M., Zhao, K., Zhao, K., & Li, G. (2020). Stress-strain relationship model of glulam bamboo under axial loading. Advanced Composites Letters, 29, 2633366X20958726. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S., Zhou, A., & Li, J. (2021). Mechanical properties and strength grading of engineered bamboo composites in China. Advances in Civil Engineering, 2021(1), 6666059. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D., Li, H., Lorenzo, R., Yuan, C., Hong, C., & Chen, Y. (2023). Basic mechanical properties of laminated flattened-bamboo composite: an experimental and parametric investigation. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 35(8), 04023258. [CrossRef]

- Harries, K. A., Mofidi, A., Naylor, J., Trujillo, D., Lopez, L. F., Gutierrez, M., Sharma, B., & Rogers, C. (2022). Knowledge gaps and research needs in bamboo construction. International Conference on Non-conventional Materials and Technologies (NOCMAT 2022).

- Sharma, B., Gatóo, A., Bock, M., & Ramage, M. H. (2015). Engineered bamboo for structural applications. Construction and Building Materials, 81, 66-73. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Ji, Y., & Yu, W. (2019). Development of bamboo scrimber: A literature review. Journal of Wood Science, 65(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Semple, K., Hu, Y. A., Zhang, J., Zhou, C., Pineda, H., ... & Dai, C. (2024). Fundamentals of bamboo scrimber hot pressing: mat compaction and heat transfer process. Construction and Building Materials, 412, 134843. [CrossRef]

- He, Z., Huang, H., Sun, L., Fan, D., & Ren, H. (2024). Mechanical and fire properties of flame-retardant laminated bamboo lumber glued with phenol formaldehyde and melamine urea formaldehyde adhesives. Polymers, 16(4), Article 594.

- Xu, Q., Leng, Y., Chen, X., Harries, K. A., Chen, L., & Wang, Z. (2018). Experimental study on flexural performance of glued-laminated-timber-bamboo beams. Materials and Structures, 51, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., ... & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71.

- Haddaway, N. R., Page, M. J., Pritchard, C. C., & McGuinness, L. A. (2022). PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18, e1230.

- Xu, Q., Chen, L., Harries, K. A., & Li, X. (2018). Combustion performance of engineered bamboo from cone calorimeter tests. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products, 76(2), 619-628. [CrossRef]

- SCImago. (2025). SJR — SCImago Journal & Country Rank. https://www.scimagojr.com.

- Hu, Y., Xiong, L., Li, Y., Semple, K., Nasir, V., Pineda, H., ... & Dai, C. (2022). Manufacturing and characterization of wide-bundle bamboo scrimber: a comparison with other engineered bamboo composites. Materials, 15(21), 7518. [CrossRef]

- Gao, D., Chen, B., Wang, L., Tang, C., & Yuan, P. (2022). Comparative Study on Clear Specimen Strength and Member Strength of Side-Pressure Laminated Bamboo. Advances in Civil Engineering, 2022(1), 2546792. [CrossRef]

- Dong, W., Wang, Z., Zhou, J., & Gong, M. (2021). Experimental study on bending properties of cross-laminated timber-bamboo composites. Construction and Building Materials, 300, 124313. [CrossRef]

- Correal, J. F., Echeverry, J. S., Ramírez, F., & Yamín, L. E. (2014). Experimental evaluation of physical and mechanical properties of Glued Laminated Guadua angustifolia Kunth. Construction and Building Materials, 73, 105-112. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Wei, Y., Wang, G., Zhao, K., & Ding, M. (2023). Mechanical behavior of laminated bamboo-timber composite columns under axial compression. Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering, 23(2), 72. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D., Li, H., Xiong, Z., Lorenzo, R., Corbi, I., & Corbi, O. (2022). Fibre alignment angles effect on the tensile performance of laminated bamboo lumber. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products, 80(4), 829-840. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M., Mei, L., Guo, N., Ren, J., Zhang, Y., & Zhao, Y. (2022). Mechanical properties and failure mechanisms of engineering bamboo scrimber. Construction and Building Materials, 344, 128082. [CrossRef]

- Brito, F. M. S., Paes, J. B., da Silva Oliveira, J. T., Arantes, M. D. C., Vidaurre, G. B., & Brocco, V. F. (2018). Physico-mechanical characterization of heat-treated glued laminated bamboo. Construction and Building Materials, 190, 719-727. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y., Cai, H., & Dong, S. Y. (2021). A pilot study on cross-laminated bamboo and timber beams. Journal of Structural Engineering, 147(4), 06021002. [CrossRef]

- Forest Products Laboratory. (2010). Wood handbook: Wood as an engineering material (General Technical Report FPL-GTR-190). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory.

- Wang, S., Jiang, Z., Huang, L., Huang, B., Wang, X., Chen, L., & Ma, X. (2024). High-performance bamboo-wood composite materials based on the natural structure and original form of bamboo: Fracture behavior and mechanical characterization. Construction and Building Materials, 447, 138118. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Huang, Q., Dong, H., Wang, Z., Shu, B., & Gong, M. (2024). Mechanical behavior of cross-laminated timber-bamboo short columns with different layup configurations under axial compression. Construction and Building Materials, 421, 135695. [CrossRef]

- Wen, J., & Xiao, Y. (2023). The flexural behavior of cross laminated bamboo and timber (CLBT) and cross laminated timber (CLT) beams. Construction and Building Materials, 408, 133739. [CrossRef]

- McGavin, R. L., Nguyen, H. H., Gilbert, B. P., Dakin, T., & Faircloth, A. (2019). A comparative study on the mechanical properties of laminated veneer lumber (LVL) produced from blending various wood veneers. BioResources, 14(4), 9064-9081. [CrossRef]

- Sylvayanti, S. P., Nugroho, N., & Bahtiar, E. T. (2023). Bamboo scrimber’s physical and mechanical properties in comparison to four structural timber species. Forests, 14(1), 146. [CrossRef]

- Al-Rukaibawi, L. S., Kachichian, M., & Károlyi, G. (2024). Mechanical properties of laminated bamboo lumber N-finity according to ISO 23478-2022. Journal of Wood Science, 70(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Singh, A., & Zhou, Y. (2024). Experimental study on the flexural behavior of I-shaped laminated bamboo composite beam as sustainable structural element. Buildings, 14(3), 671. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Wei, Y., Lin, Y., Chen, S., & Chen, J. (2024). Out-of-plane characteristics of cross-laminated bamboo and timber beams under variable span three-point loading. Construction and Building Materials, 411, 134647. [CrossRef]

- Lei, J., Chen, B., & Yuan, P. (2020). Experimental Study on Flexural Properties of Side-Pressure Laminated Bamboo Beams. Advances in Civil Engineering, 2020(1), 5629635. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D., Li, H., Xiong, Z., Mimendi, L., Lorenzo, R., Corbi, I., ... & Hong, C. (2020). Mechanical properties of laminated bamboo under off-axis compression. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, 138, 106042. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Wu, G., Zhang, Q., Deeks, A. J., & Su, J. (2018). Ultimate bending capacity evaluation of laminated bamboo lumber beams. Construction and Building Materials, 160, 365-375. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z., Chen, Z., Huang, D., & Zhou, A. (2016). The ultimate load-carrying capacity and deformation of laminated bamboo hollow decks: Experimental investigation and inelastic analysis. Construction and Building Materials, 117, 190-197. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Wei, Y., Chen, J., Du, H., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Out-of-plane bending and shear behavior of cross-laminated bamboo and timber under four-point loading with variable spans. Engineering Structures, 323, 119273. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Xizhi, W., Li, X., & Liu, X. (2024). Structure and physical properties of high-density bamboo scrimber made from refined bamboo bundles. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A., Way, D., & Mlasko, S. (2014). Structural performance of glued laminated bamboo beams. Journal of Structural Engineering, 140(1), 04013021. [CrossRef]

- He, M., Li, Z., Sun, Y., & Ma, R. (2015). Experimental investigations on mechanical properties and column buckling behavior of structural bamboo. The Structural Design of Tall and Special Buildings, 24(7), 491-503. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Q., Zhou, S. C., Lai, S. T., Xu, M. D., & Xiao, Y. (2023). Impact Toughness and Quasi-Static Bending Strength of Glubam. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 35(9), 04023322. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Wei, Y., Zhao, K., Dong, F., & Huang, L. (2022). Experimental investigation on the flexural behavior of laminated bamboo-timber I-beams. Journal of Building Engineering, 46, 103651. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Zhu, R., Wu, B., Hu, Y. A., & Yu, W. (2015). Fabrication, material properties, and application of bamboo scrimber. Wood Science and Technology, 49, 83-98. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Shen, M., Deng, Y., Andras, P., Sukontasukkul, P., Yuen, T. Y., ... & Hansapinyo, C. (2023). A new concept of bio-based prestress technology with experimental Proof-of-Concept on Bamboo-Timber composite beams. Construction and Building Materials, 402, 132991. [CrossRef]

- Liliefna, L. D., Nugroho, N., Karlinasari, L., & Sadiyo, S. (2020). Development of low-tech laminated bamboo esterilla sheet made of thin-wall bamboo culm. Construction and Building Materials, 242, 118181. [CrossRef]

- Chow, A., Ramage, M. H., & Shah, D. U. (2019). Optimising ply orientation in structural laminated bamboo. Construction and Building Materials, 212, 541-548. [CrossRef]

- Liang, E., Chen, C., Tu, D., Zhou, Q., Zhou, J., Hu, C., ... & Ma, H. (2022). Highly efficient preparation of bamboo scrimber: drying process optimization of bamboo bundles and its effect on the properties of bamboo scrimber. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products, 80(6), 1473-1484. [CrossRef]

- He, S., Xu, J., Wu, Z. X., Yu, H., Chen, Y. H., & Song, J. G. (2018). Effect of bamboo bundle knitting on enhancing properties of bamboo scrimber. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products, 76, 1071-1078. [CrossRef]

- Colince, L., Qian, J., Zhang, J., Wu, C., & Yu, L. (2024). Study on the Molding Factors of Preparing High-Strength Laminated Bamboo Composites. Materials, 17(9), 2042. [CrossRef]

- Huang, B., Wang, X., Su, N., & Fang, C. (2024). High-performance engineered bamboo units with customizable radius based on pressure-drying technology: Multi-scale mechanical properties. Construction and Building Materials, 457, 139472. [CrossRef]

- Chung, M. J., & Wang, S. Y. (2018). Effects of peeling and steam-heating treatment on mechanical properties and dimensional stability of oriented Phyllostachys makinoi and Phyllostachys edulis scrimber boards. Journal of Wood Science, 64, 625-634. [CrossRef]

- Guan, X., Yin, H., Lin, C., & Zhan, W. (2022). Effect of layups on the mechanical properties of overlaid laminated bamboo lumber made of radial bamboo slices. Journal of Wood Science, 68(1), 40. [CrossRef]

- Li, T. Y., Deng, J. Y., Chen, J. Q., Xiao, Y., Shan, B., Xu, H., ... & Yu, Q. (2023). Bending performance of nail-laminated bamboo-timber panels made with glubam and fast-grown plantation Chinese fir. Construction and Building Materials, 384, 131425. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J., Li, H., Wang, G., Chen, F., & Zhang, W. (2015). Effect of removing extent of bamboo green on physical and mechanical properties of laminated bamboo-bundle veneer lumber (BLVL). European Journal of Wood and Wood Products, 73, 499-506. [CrossRef]

- Aschheim, M., Gil-Martín, L. M., & Hernández-Montes, E. (2010). Engineered bamboo I-joists. Journal of structural engineering, 136(12), 1619-1624.

- Ma, Y., Luan, Y., Chen, L., Huang, B., Luo, X., Miao, H., & Fang, C. (2024). A Novel Bamboo-Wood Composite Utilizing High-Utilization, Easy-to-Manufacture Bamboo Units: Optimization of Mechanical Properties and Bonding Performance. Forests, 15(4), 716. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).