1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic syndrome characterized by widespread pain, fatigue, stiffness, sleep disturbances, and cognitive impairments (Bair, 2020), although its etiology remains debated (Dizner-Golab, 2023). It is considered a central sensitization syndrome, involving dysfunction in pain-processing neural circuits (López-Ruiz et al., 2019; Pujol et al., 2014; Pujol et al., 2022; Siracusa et al., 2021). Emotional distress exacerbates symptoms (Kocygit et al., 2022), impairing daily function and work capacity, significantly lowering well-being (Brown et al., 2023). This interplay highlights FM as both a physical and psychological condition. Prevalence ranges from 2–8% worldwide (Siracusa et al. 2021, Berwick et al. 2022, Bair, 2020) and reaches 2.4% in Spanish adults over 20 (Font et al., 2020). FM mainly affects women (4.2% vs. 0.2% in men) (Olfa et al., 2023, Kocygit et al., 2022), likely reflecting differences in pain and emotional processing. The highest prevalence (4.9%) is observed in ages 30–50 (Jurado-Priego et al., 2024), when functional demands exacerbate symptoms. Prevalence increases with age but declines after 80, likely due to symptom overlap or underreporting (Sarzi-Puttini et al., 2020).

Affective comorbidities are common in FM (37.7%), including hypervigilance, derealization, somatization, and elevated Cluster C (58.8%) or Cluster B (11.3%) traits (Dizner-Golab, 2023; Doreste et al., 2024; Romanov et al., 2023). FM symptom severity shapes psychopathological profiles: hypervigilance, suspicion, derealization, and impulsiveness are linked to fatigue and pain; while anxiety and depression relate to morning tiredness and stiffness (Attademo & Bernardini, 2018). Depressive disorders are the most prevalent diagnosis (43%) in FM, with major depression reaching 32% and persistent depression in 50-53% of cases (Doreste et al., 2025; Garcia-Fontanals et al., 2014; Munipalli et al., 2024). These affective disturbances impact core FM symptoms like pain and fatigue (Kim et al., 2023) and are often accompanied by cognitive deficits, including attentional, memory and impulsivity issues (Aghbelaghi et al., 2024). Additionally, dissociative identity disorder appears in 16.6-18.2% of FM cases, linked to somatoform dissociation (48.5%), emotional dysregulation, and trauma (Doreste et al., 2024; Romeo et al., 2022a). FM patients also show social dysfunction resembling schizoid personality traits (1.9-22.2%) (Doreste et al., 2024; Romanov et al., 2023), with impulsivity associated with chronic pain and fatigue (Romanov et al., 2023).

Although personality disorders (PDs) are not a direct cause of FM, their comorbidity exacerbates emotional symptoms and complicates management. PD prevalence in FM ranges from 56.7% to 64.3% (Romanov et al., 2023; Doreste, 2024). Cluster C PDs—avoidant (3.8-28.8%), dependent (0-10%), and obsessive-compulsive (11.3-20%)—are predominant, though borderline (28.3%) and histrionic (1.9%) PDs from Cluster B are also observed (Romanov et al., 2023; Doreste et al., 2024). Type D personality, characterized by negative affect and social inhibition, correlates with higher FM severity (Garip et al., 2019). Personality traits like fear, rigidity, and anxiety reduce self-control and intensify anticipatory anxiety, often observed in more severe FM presentations. (García-Fontanals et al., 2017; Izquierdo-Alventosa et al., 2020). Dependent PD, in particular, is linked to increase fatigue, though this may be mitigated by autonomy and social support. Dependent, schizotypal, schizoid, and borderline personality traits predict FM severity, while Cluster B traits, though less prevalent, contribute to heightened pain and emotional distress (Izquierdo-Alventosa et al., 2020).

Given this complex interaction between physical and emotional symptoms, it is essential to further investigate FM’s psychological dimensions. FM is a heterogeneous disorder with highly variable symptom presentation, commonly classified according to physical characteristics, while psychological heterogeneity remains underexplored (Maurel et al., 2023; Sarzi-Puttini et al., 2020). Although no standardized subgrouping exists (Luciano et al., 2016), cluster analyses using self-reports have identified FM subtypes combining physical and psychopathological features. For instance, Keller et al., (2011) and de Souza et al., (2009) described subgroups differing in anxiety, depression, morning tiredness, fatigue, and joint stiffness, yet sharing common physical symptoms such as hyperalgesia. Similarly, Vincent et al., (2014) identified four subgroups based on overall symptom intensity, anxiety, and depression levels. Moreover, psychological distress, maladaptive cognitions, and poor coping strategies have been shown to amplify pain perception (Bucourt et al., 2021; Campos et al., 2021). Finally, SCL-90 profiles have linked somatization and obsessive traits to physical symptoms, while broader psychopathology is associated with complex comorbidities (Keller et al., 2011; Toussaint et al., 2014).

To address this gap — the limited exploration of psychological heterogeneity beyond anxiety and depression in FM — the present study used the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) (Rivera & González, 2004) and the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI) as core instruments (Burneo-Garcés et al., 2020). FIQ assesses FM's impact across three domains: physical functioning, symptom severity (e.g., pain, fatigue, stiffness), and overall well-being, providing a detailed view of disability and quality of life (Keller et al., 2011; Maurel et al., 2023). The PAI offers a multidimensional evaluation of psychopathology aligned with DSM-5 criteria and has proven effective in chronic pain and FM to facilitate the identification of emotional and personality-related disturbances (Karlin et al., 2005).

This study aimed to identify psychopathological profiles using the PAI, according to the type of FM impact in functional-work, physical-somatic, and emotional domains as measured by the FIQ and cumulative severity. We hypothesize that patients with severe functional impairment will exhibit higher emotional dysregulation and depressive symptoms (Ciuffini et al. 2023, Fischer-Jbali et al., 2021 and Fischer-Jbali et al., 2022); those with pronounced physical-somatic impairment will be associated with heightened somatic complaints and mood instability (Creed, 2022 and Hadlandsmyth et al., 2020); and patients with severe emotional impairment will present a higher prevalence of depressive disorders and suicidality (Galvez-Sánchez et al., 2019; Levine et al., 2020). Additionally, cumulative severity is expected to significantly intensify those psychopathological profiles, particularly emotional instability and somatization (Creed, 2022; González et al. 2020). Identifying these profiles will enhance understanding of FM’s biopsychosocial complexity and support the development of personalized treatment approaches integrating both physical and psychological dimensions of the condition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The research included females aged 18-65 diagnosed with FM based on American College of Rheumatology criteria (Wolfe et al., 1997). Inclusion criteria additionally required having stable pharmacological treatment, understanding the study requirements, and a commitment to compliance. Exclusion criteria encompassed the presence of other conditions explaining pain; inflammatory or rheumatic diseases; severe or unstable medical, endocrine, or neurological conditions; a history of neuropathic pain; acute psychotic disorders; substance abuse; and invalid scores on the FIQ and PAI validity scales, which could compromise data interpretation.

2.2. Participants

Patients were recruited from the Fibromyalgia Unit at Barcelona’s Hospital del Mar by senior rheumatologists (FO or JM) and a senior psychologist (JD) between January 2021 and June 2022. During this period, 136 female patients were diagnosed with FM, and 110 underwent eligibility assessments across consecutive clinical visits. Forty patients either did not meet the study criteria or declined participation, yielding a final sample of seventy participants who completed both the FIQ and PAI questionnaires. Detailed sociodemographic and clinical characteristics can be found in

Table 1.

2.3. Study Design and Procedure

We used a non-randomized, purposive sampling method to include all eligible participants from the study population. This observational, cross-sectional study involved female patients attending routine rheumatology appointments (FO and JM). After eligibility screening of inclusion/exclusion criteria, and confirmation of willingness to participate, patients were enrolled and provided informed consent. Psychological assessments, conducted by a senior clinical psychologist (AD), were scheduled within the same week and lasted up to 90 minutes to minimize response fatigue.

2.4. Instruments

The Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI) (Morey, 1991), in its Spanish adaptation (Burneo-Garcés et al., 2020), is a widely used 344-item self-reported measure designed to assess a broad spectrum of psychopathological symptoms and personality disorders. The PAI features 27 scales: 4 validity, 5 supplemental validity, 11 clinical, 5 treatment consideration, and 2 interpersonal, along with 31 clinically relevant subscales. This extensive range of scales enables the identification of various psychopathological patterns, covering 17 clinical syndromes and 11 personality disorders (Doreste et al., 2025; Ortiz-Tallo et al., 2011). Participants respond using a 4-point Likert-type scale (from 1—not at all true to 4—very true), and raw scores are converted to T-scores based on normative data from the Spanish population (Burneo-Garcés et al., 2020). Typically, a T-score above 61 indicates a moderate to high presence of psychopathological traits (Burneo-Garcés et al., 2020; Karlin et al., 2005; Morey & Alarcón, 2013). However, specific scales may require alternative cut-off scores to enhance diagnostic accuracy, as recommended in the PAI manual (Morey & Alarcón, 2013). The Spanish version of the PAI has demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties, including internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.82 overall; α = 0.78 in non-clinical samples and α = 0.83 in clinical populations), as well as content and convergent validity across diverse groups (Burneo-Garcés et al., 2020). In individuals with chronic pain, the PAI demonstrates acceptable internal consistency both for scale and subscale scores for assessing psychopathology patterns in chronic pain settings (Karlin et al., 2005).

The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) (Burckhardt et al., 1991), in its Spanish version (Rivera & González, 2004), is a 10 items self-administered tool that assesses the functional and overall impact of FM on daily living. It evaluates multiple aspects, including physical functioning, work-related limitations, and psychological well-being, offering a comprehensive picture of FM’s impact. Total score range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating greater disease impact and disability. The Spanish version has demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.81), test-retest reliability over a 7-day period (with significant correlations from 0.52 for fatigue and 0.53 for pain to 0.91 for depression). It also provides evidence of validity based on its relationships with other variables, along with good sensitivity to changes over time (Monterde et al., 2004). Due to its ability to capture the multifaceted impact of FM, the FIQ is considered an essential instrument to quantify disability and guide treatment planning in both clinical and research settings.

2.5. Data Analysis

A descriptive analysis of sociodemographic and clinical features was conducted to delineate the characteristics of the entire study sample. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software (Version 21.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) for all analyses. Statistical significance was set at 5% and the sequence of the data analysis involved four main steps:

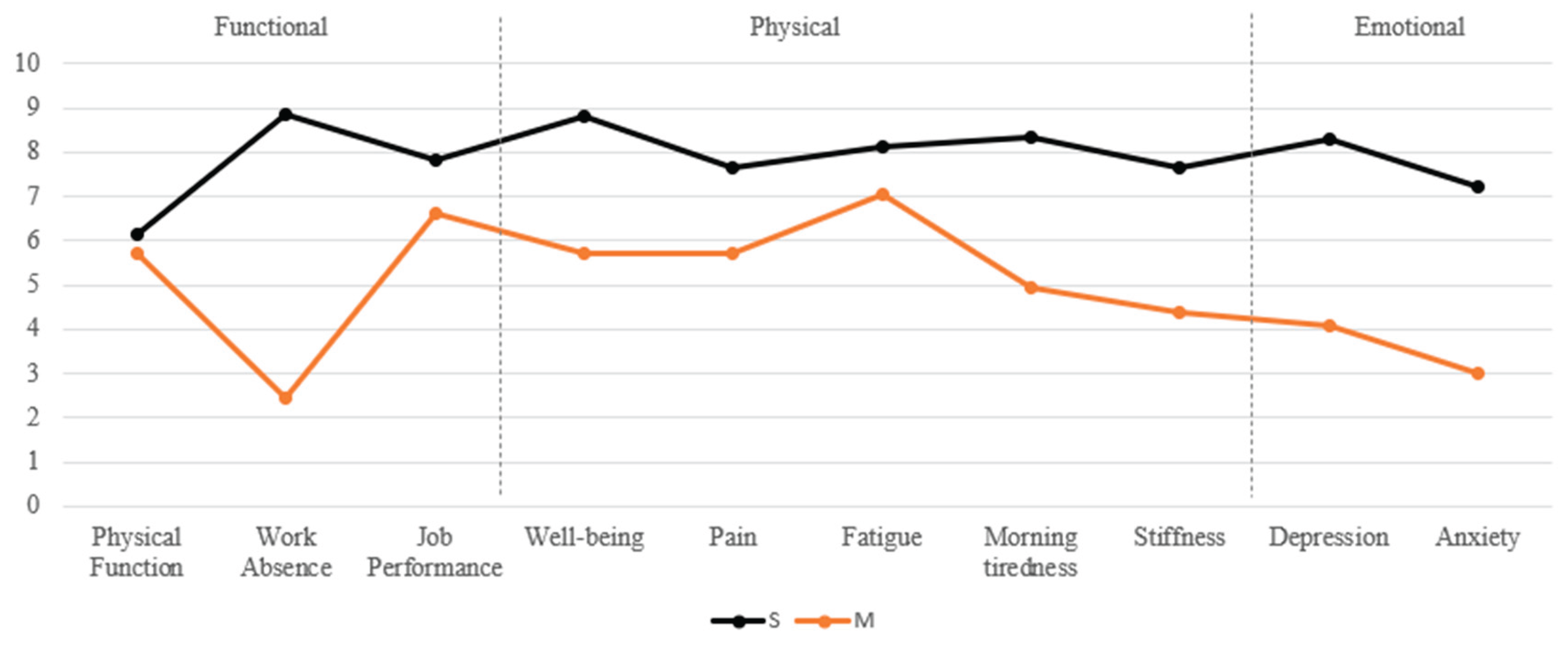

Cluster Analysis. A hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward's method with squared Euclidean distance was performed based on FIQ variables to classify patients into domains according to the severity of functional (Func), physical-somatic (Phys), and emotional (Emot) impairments. This method minimizes within-group variance, allowing for the identification of homogeneous and clinically meaningful domains. FIQ variables included in different domains were: Func (work absence, physical function, job performance), Phys (well-being, pain, fatigue, morning tiredness and stiffness) and Emot (depression and anxiety). For each domain, a cluster analysis was conducted to classify participants into two severity levels: Mild (M) and Severe (S). Analysis resulted in six distinct clusters: Func-M and Func-S, Phys-M and Phys-S, and Emot-M and Emot-S.

Discriminant function analysis was conducted to validate the classifications obtained through cluster analysis and to identify the variables that best differentiated between severity levels within each domain, using Wilk’s Lambda as the test statistic. The assumption of homogeneity of covariance matrices was assessed using Box’s M test. Canonical correlation analysis was used to explore the relationship between the discriminant functions and the original FIQ variables. Finally, classification accuracy and cross-validation procedures were applied to evaluate the reliability of the group assignments made by the discriminant functions.

Pairwise comparisons were conducted to examine differences on psychological PAI scales, subscales, and clinical diagnostic categories between the severe and mild clusters within each domain (Func, Phys, and Emot). As the data violated the normality assumption (Shapiro-Wilk test), non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests were used for these comparisons.

Clinical Characterization. Complementing these statistical comparisons, we also assessed the clinical patterns of each cluster by calculating the percentage of patients meeting criteria for positive psychological diagnoses. This analysis provided a more nuanced understanding of the psychopathological profiles associated with each severity level. Diagnoses were based on PAI scales and subscales, using a threshold score of 60 to indicate clinically significant symptomatology, in line with previous research (Doreste et al., 2024). In addition, published diagnostic criteria for dysthymia and comorbid dysthymia with major depression were applied to capture complex affective presentations not fully reflected by the standard PAI scoring (Doreste et al., 2025).

Cumulative severity. In a final step, we focused exclusively on the severe clusters to explore cumulative impact severity. Patients were grouped according to the number of severe clusters (Func-S, Phys-S, Emot-S) they belonged to: those in only one severe cluster (Single-S), in two (Dual-S), or in all three (Triple-S). Participants who did not belong to any severe cluster were classified as No-S. Based on this classification, a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare PAI scales, subscales, and positive psychological diagnoses across cumulative severity groups.

3. Results

Descriptive and cluster analysis. Patients (N=70) were analyzed across the three impact domains —Func, Phys, and Emot—and further subdivided into mild (M) and severe (S) impairment levels: Func-M (n=49, 70.0%) vs. Func-S (n=21, 30.0%), Phys-M (n=18, 25.7%) vs. Phys-S (n=52, 74.3%), and Emot-M (n=28, 40.0%) vs. Emot-S (n=42, 60.0%). Descriptive analysis of each FIQ impact domain across M and S clusters can be seen in

Figure 1.

Discriminant functional analysis validated the FIQ-based classification of domains and clusters with functional, physical-somatic, and emotional impairment (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

In the functional domain, three predictors were included: physical function, work absence, and job performance. Significant differences were found for work absence and job performance, while physical function was not a significant contributor. A single discriminant function explained 100% of the variance with a strong canonical correlation. Work absence was the strongest predictor, followed by job performance; physical function had negligible impact. The model achieved 94.3% overall accuracy, correctly classifying 95.9% of Func-M and 90.5% of Func-S cases.

In the physical-somatic domain, predictors were well-being, pain, fatigue, morning tiredness, and stiffness. All variables showed significant differences. A single discriminant function again explained 100% of the variance with a strong canonical correlation. Morning tiredness was the most influential predictor, followed by stiffness, well-being, and pain. Fatigue showed a lower, inverse contribution. Classification accuracy reached 100%, correctly classifying all Phys-M and Phys-S cases.

In the emotional domain, depression and anxiety were used as predictors. Both differed significantly between severity groups. A single discriminant function accounted for 100% of the variance, with strong canonical correlation. Anxiety was the strongest predictor, followed by depression. The model achieved 97.1% accuracy, correctly classifying 97.6% of Emot-M and 96.4% of Emot-S participants.

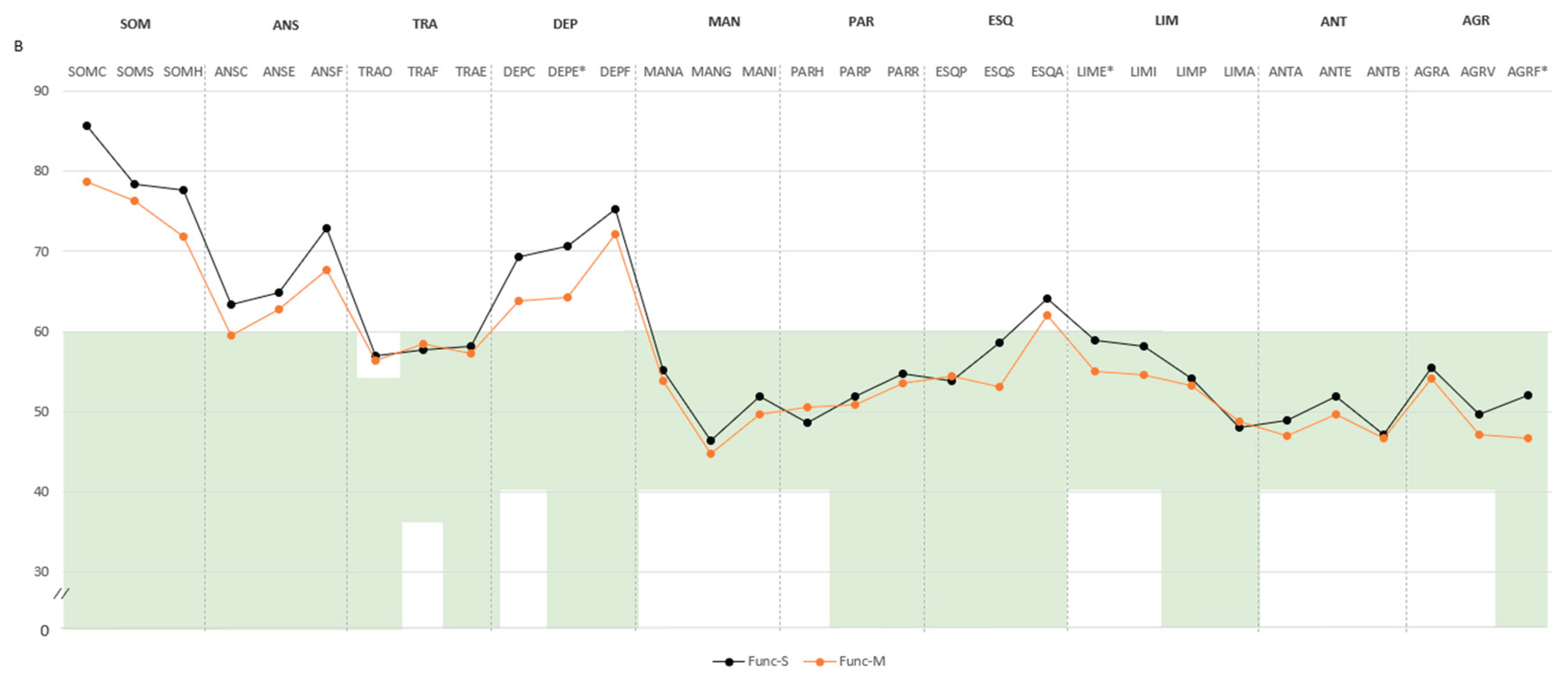

Pairwise comparison. In the functional domain, participants classified as Func-S showed higher scores across several psychopathological domains compared to Func-M. Specifically, significant differences were found in negative impression (M=71.4, SD=14.8 vs. M=62.9, SD=14.3), somatic disorders (SOM: M=85.5, SD=7.7 vs. M=79.7, SD=10.0), and depression (DEP: M=76.4, SD=10.4 vs. M=70.2, SD=9.2), with all mean scores exceeding the defined cut-off point of 60. Subscale differences included higher scores in health concerns (SOM-H: M=77.6, SD=11.0 vs. M=71.8, SD=10.0), emotional depression (DEP-E: M=70.7, SD=11.3 vs. M=64.2, SD=11.7), both above the cut-off point. Additional differences were noted in emotional instability (M=58.9, SD=9.5 vs. M=55.0, SD=9.1) and physical aggression (M=52.0, SD=11.4 vs. M=46.6, SD=5.5). Higher scores in violence index (M=57.2, SD=14.7 vs. M=49.8, SD=8.4) and treatment difficulties (M=58.4, SD=10.6 vs. M=53.0, SD=8.6) indicated increased aggressiveness potential and treatment difficulties (

Figure 2A,B).

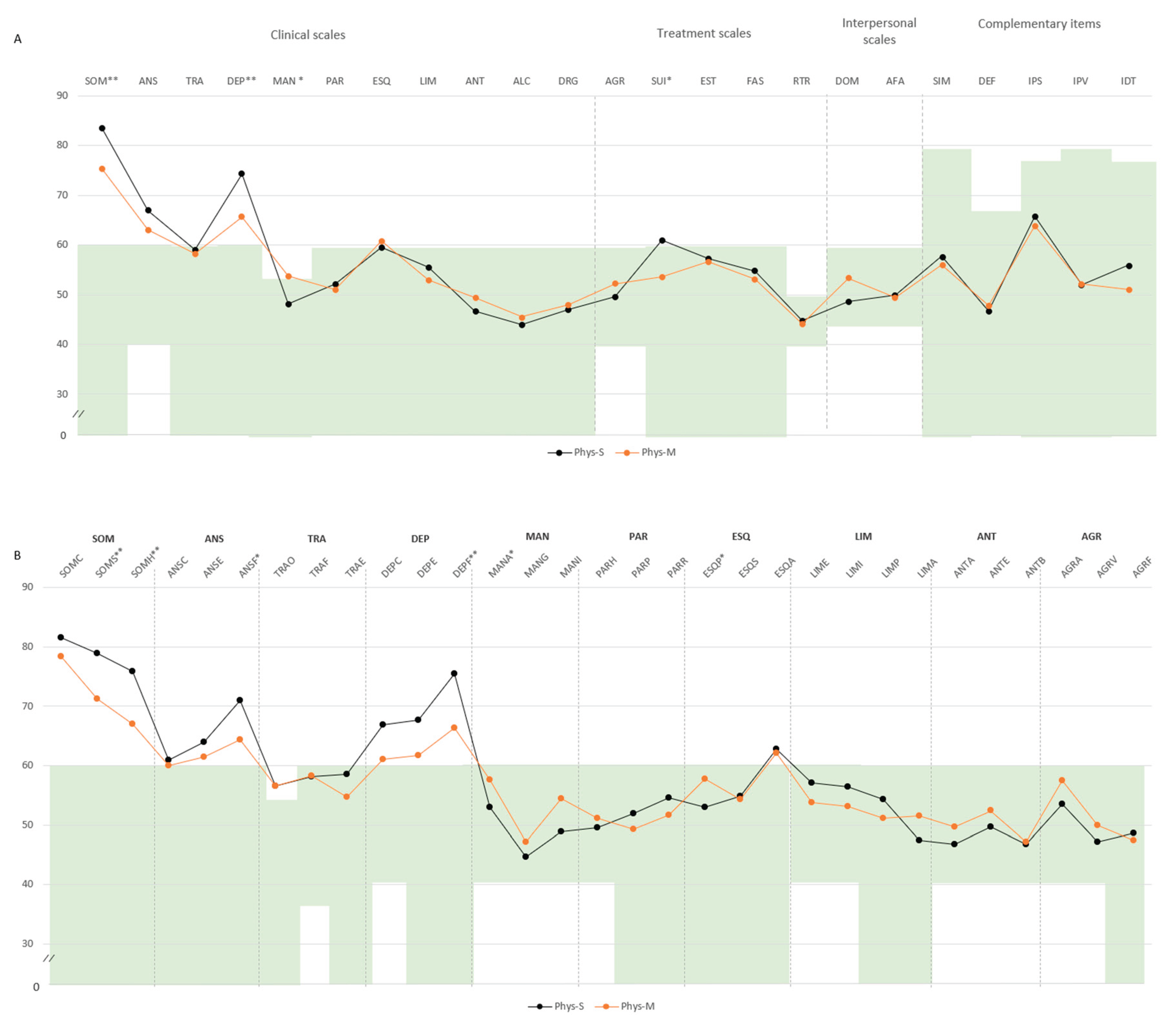

In the physical-somatic domain, Phys-S individuals showed higher scores in SOM (M=83.6, SD=9.0 vs. M=75.4, SD=9.3) and DEP (M=74.2, SD=8.2 vs. M=65.6, SD=11.9), both exceeding the defined cut-off point. Additional differences emerged in mania (MAN: M=48.1, SD=9.7 vs. M=53.7, SD=8.4) and suicidal ideation (SUI: M=60.9, SD=16.1 vs. M=53.6, SD=17.0). Subscale comparisons revealed higher scores in somatization (SOM-S: M=78.9, SD=7.6 vs. M=71.2, SD=7.6), SOM-H (M=75.8, SD=10.2 vs. M=66.9, SD=8.9), physical anxiety (ANS-F: M=70.9, SD=11.2 vs. M=64.3, SD=11.2), and physical depression (DEP-F: M=75.4, SD=6.6 vs. M=66.3, SD=9.1), all above the clinical threshold (

Figure 3A,B).

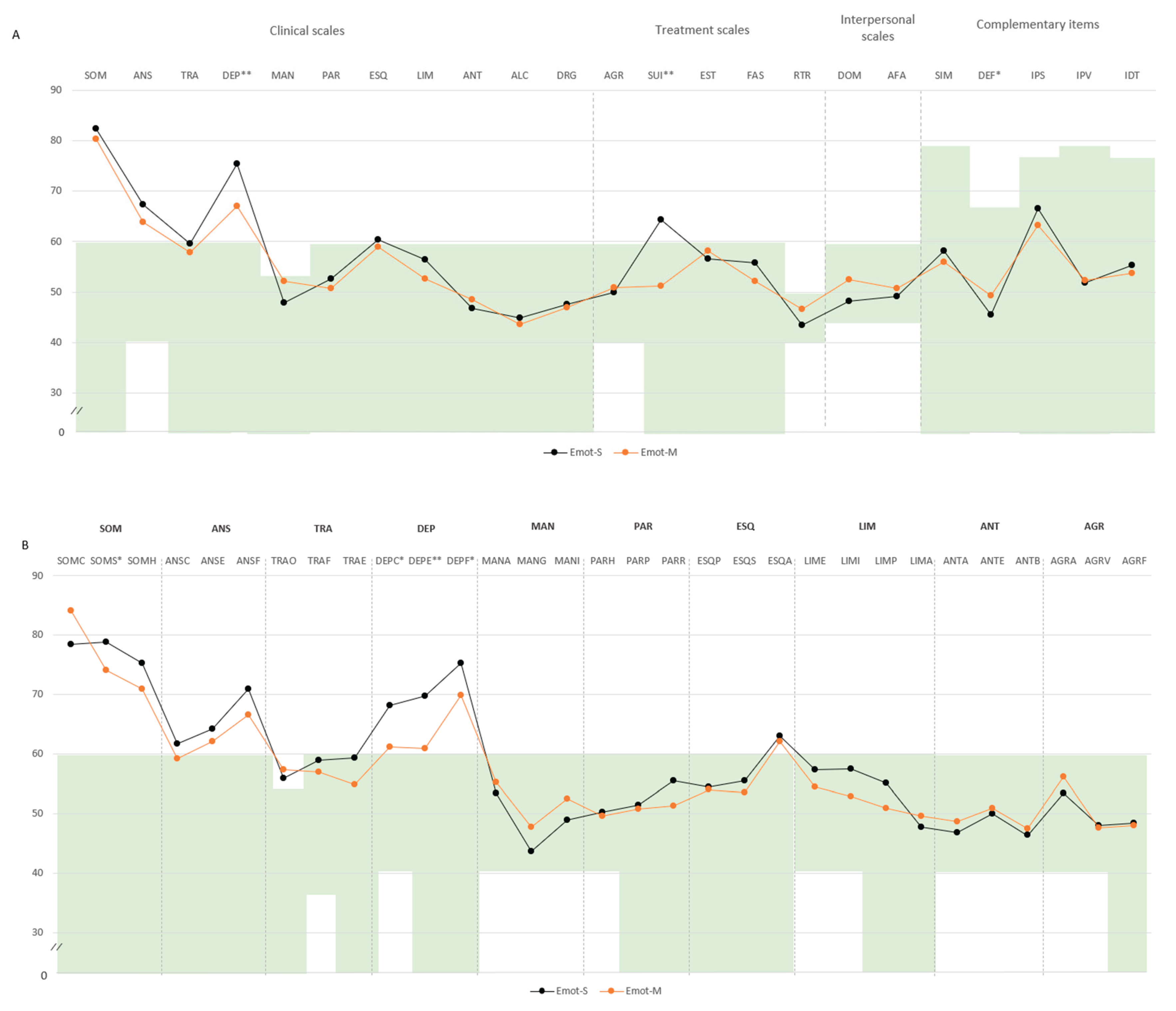

In the emotional domain, Emot-S participants had higher levels of psychopathology. Specifically, DEP (M=75.4, SD=8.5 vs. M=67.0, SD=9.8), SUI (M=64.2, SD=17.5 vs. M=51.2, SD=11.3), and SOM-S (M=78.8, SD=8.0 vs. M=74.0, SD=7.9) exceeded the threshold. Subscale analyses indicated greater scores in cognitive depression (DEP-C: M=68.2, SD=10.9 vs. M=61.2, SD=12.6), DEP-E (M=69.6, SD=11.9 vs. M=60.8, SD=10.0), and DEP-F (M=75.2, SD=7.1 vs. M=69.8, SD=8.9). Lower defensiveness was also noted (M=45.4, SD=7.2 vs. M=49.3, SD=7.5) (

Figure 4A,B).

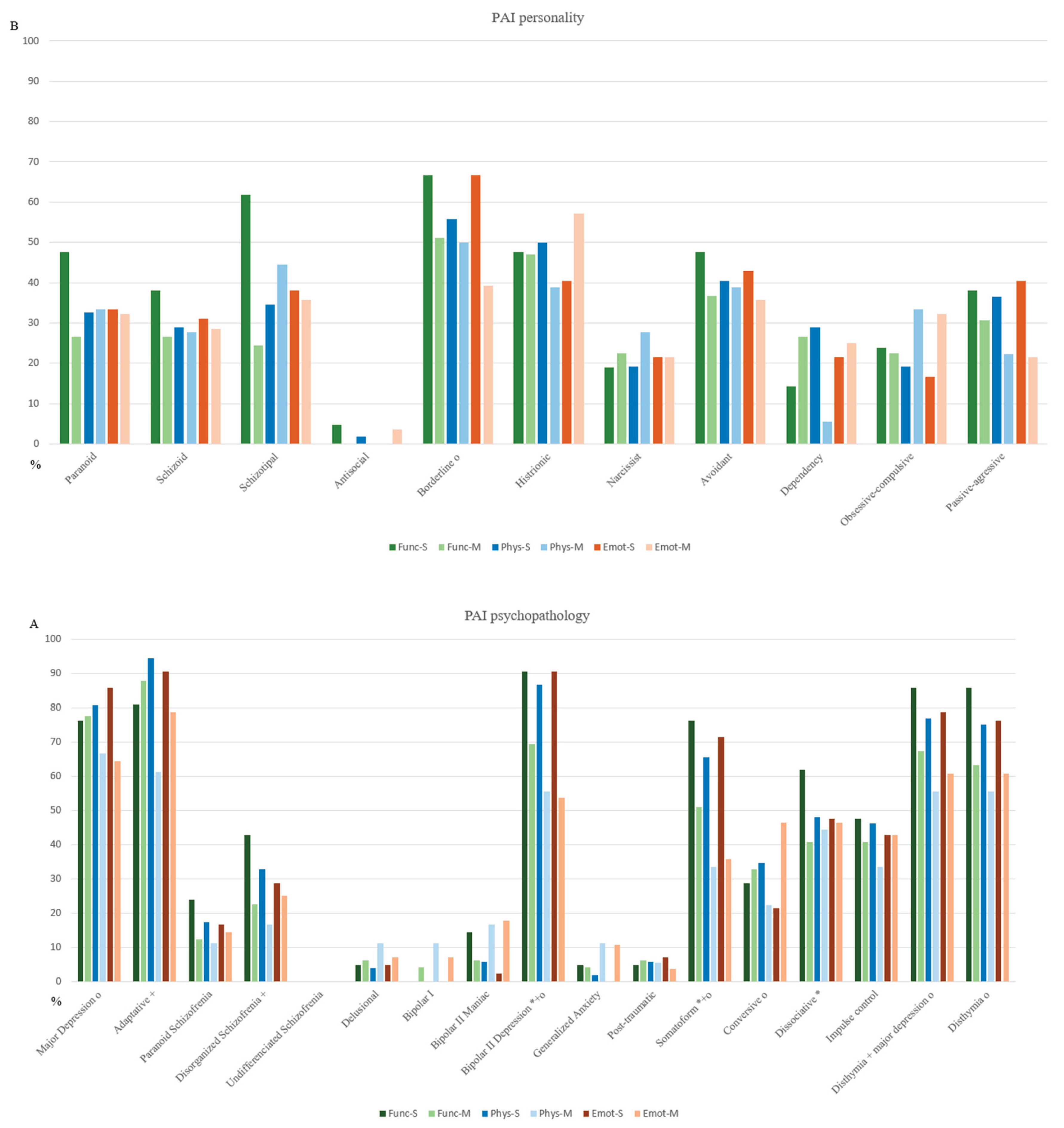

Regarding the clinical diagnostic categories, Func-S showed higher and clinically significant scores in bipolar II depressive disorder (68.57 ± 7.76 vs. 63.78 ± 7.44), somatic disorder (65.17 ± 7.16 vs. 61.87 ± 6.36), and dissociative disorder (62.84 ± 8.04 vs. 58.40 ± 8.86). Phys-S exhibited elevated scores mainly in adaptive disorder (63.84 ± 3.04 vs. 60.73 ± 2.99) and bipolar II depressive disorder (66.77 ± 6.84 vs. 60.72 ± 8.83). Emot-S presented higher scores in major depression (66.18 ± 6.53 vs. 61.00 ± 7.79), bipolar II depressive disorder (67.63 ± 6.85 vs. 61.60 ± 7.85), and persistent depressive disorder (65.31 ± 6.81 vs. 60.52 ± 7.73) with major depression (63.36 ± 4.65 vs. 59.87 ± 5.46) (

Figure 5A,B).

Clinical characterization. The proportion of patients meeting diagnostic criteria was calculated to compare the prevalence of psychopathological diagnoses between the Severe (S) and Mild (M) clusters within each domain (Func, Phys, and Emot). Statistical significance is shown in

Figure 5A,B.

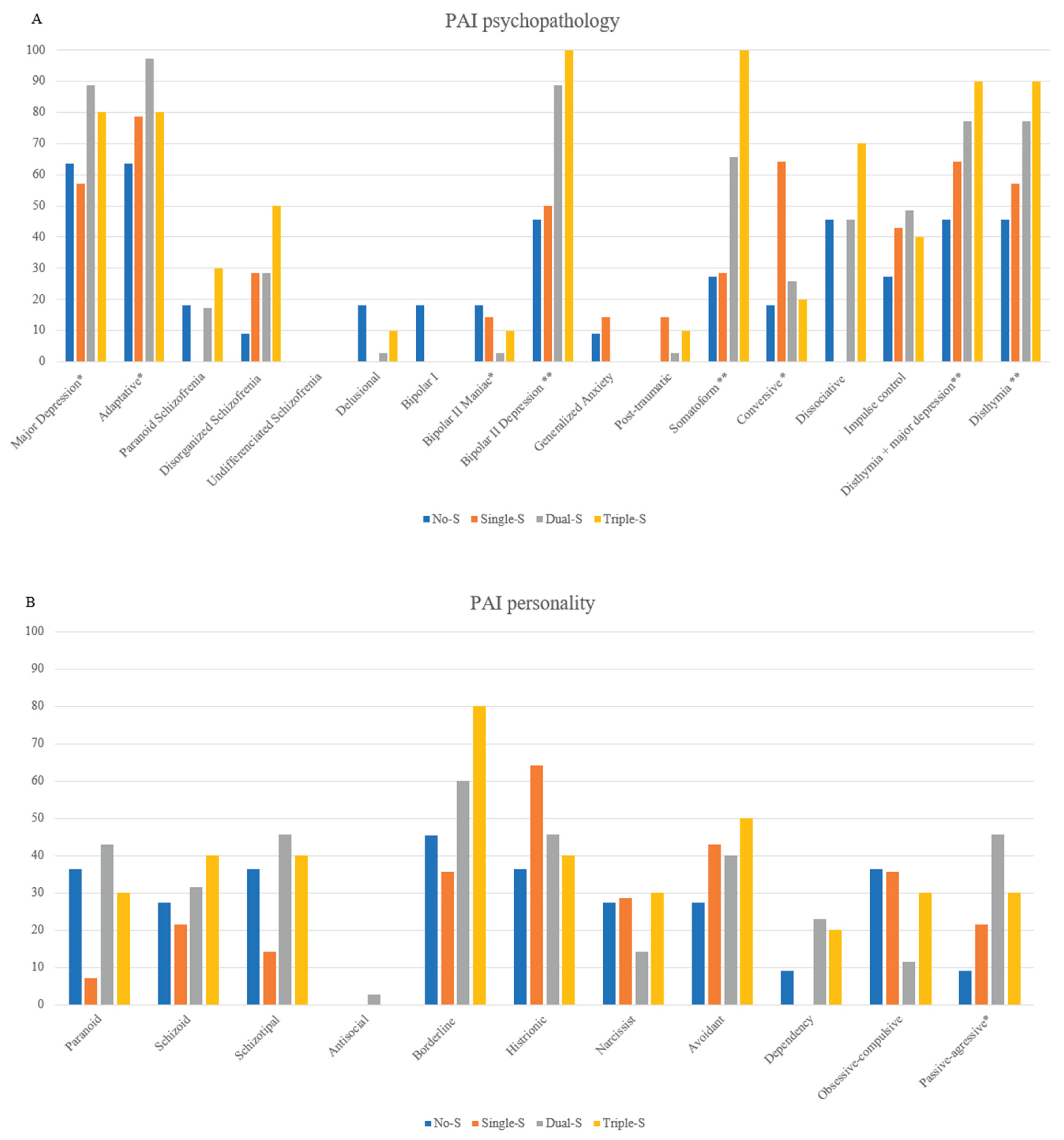

Bipolar II Depression emerged as the most severe and pervasive condition across all domains. A diagnosis was considered positive when the corresponding T score exceeded the clinical threshold of 60. In the Func domain, 90.47% of Func-S participants met this threshold, compared to 69.39% in Func-M. Similarly, 86.54% of Phys-S and 55.56% of Phys-M participants scored above the threshold. In the Emot domain, the difference was even more pronounced, with 90.47% of Emot-S versus 53.57% of Emot-M showing clinically significant scores. These findings suggest that Bipolar II Depression exerts a broader and more intense impact among individuals in the severe clusters.

Other psychopathological conditions also showed widespread impairment across domains. Both somatic disorder and dysthymia with major depression were markedly prevalent. Somatic disorder showed a higher positive percentage in functional (76.19% Func-S vs. 51.02% Func-M), physical (65.38% Phys-S vs. 33.33% Phys-M), and emotional domains (71.43% Emot-S vs. 35.71% Emot-M). Similarly, dysthymia with major depression percentages were substantial across functional (85.71% Func-S vs. 67.35% Func-M), physical (76.92% Phys-S vs. 55.56% Phys-M), and emotional domains (78.57% Emot-S vs. 60.71% Emot-M). Adaptative disorder showed the highest prevalence in the physical domain, with 94.23% in Phys-S decreasing to 61.11% in Phys-M, while borderline disorder presents substantial emotional distress (66.67% Emot-S vs. 39.29% Emot-M), suggesting a more moderate impact in milder cases. Diagnoses such as dissociative, obsessive-compulsive, and passive-aggressive disorder were more commonly observed in the Func-S. Dissociative prevalence dropped from 61.90% in Func-S to 40.82% in Func-M, while obsessive-compulsive remained low across both severity levels (23.81% Func-S, 22.45% Func-M). Conversely, conversive, impulsive, and dysthymia disorders predominantly impacted emotional functioning. Notably, disthymia showed 76.19% of Emot-S patients meeting the diagnostic threshold. The findings suggest that bipolar II depressive, somatic disorder, and dysthymia with major depression are the most functionally and emotionally debilitating conditions across all domains, while adaptative disorder and bipolar II depressive were most strongly associated with physical symptoms.

Cumulative Severity: Participants were distributed across four cumulative severity groups: No-S (n = 11; 15.7%), Single-S (n = 14; 20.0%), Double-S (n = 35; 50.0%), and Triple-S (n = 10; 14.3%). In the Single-S group, Phys-S was the most prevalent severity cluster with 71.4% of cases (n=10). In Double-S group, Phys-S (n=10, 91.4%) and Emot-S (n=29, 82.9%) emerged as the predominant cluster.

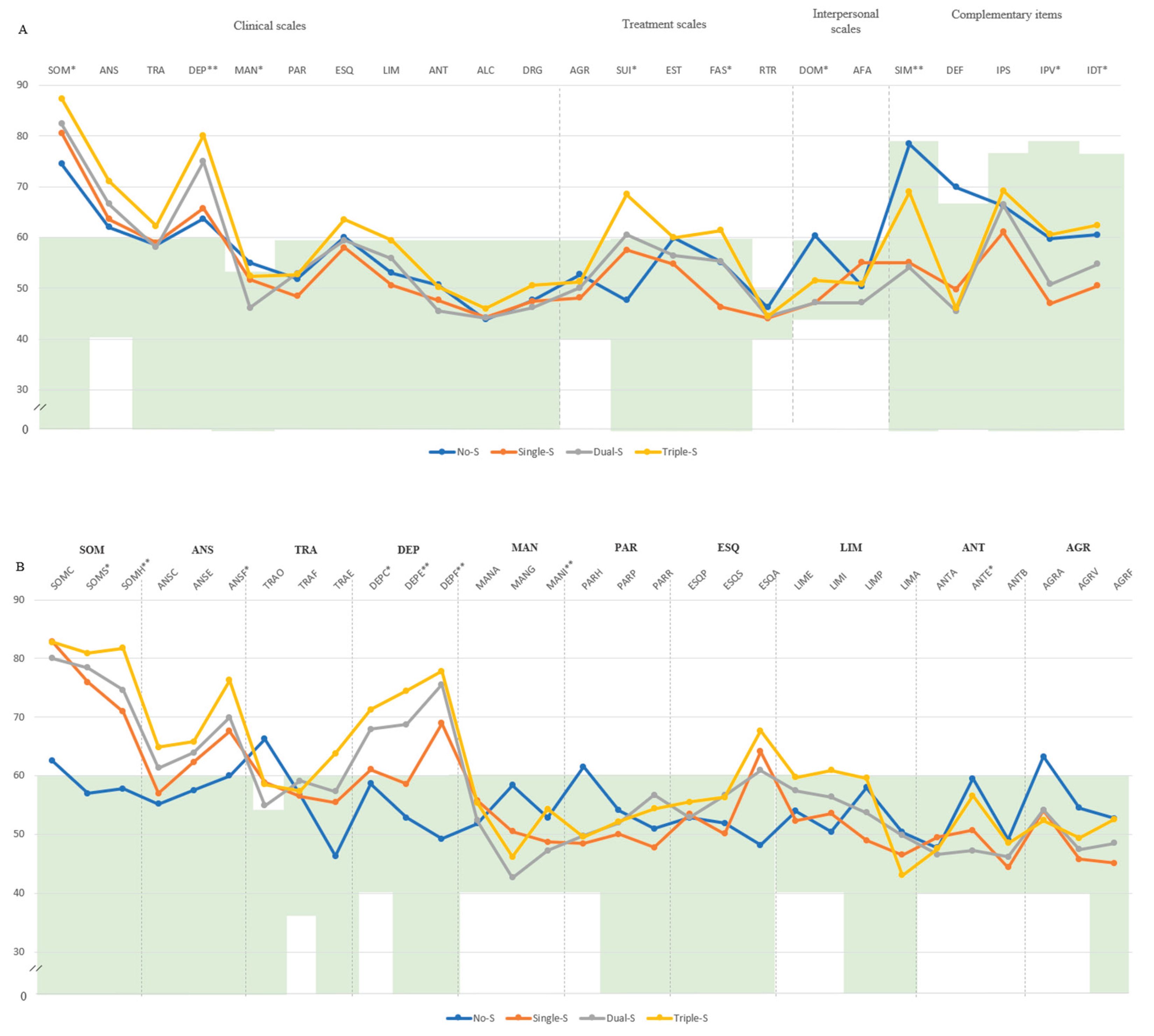

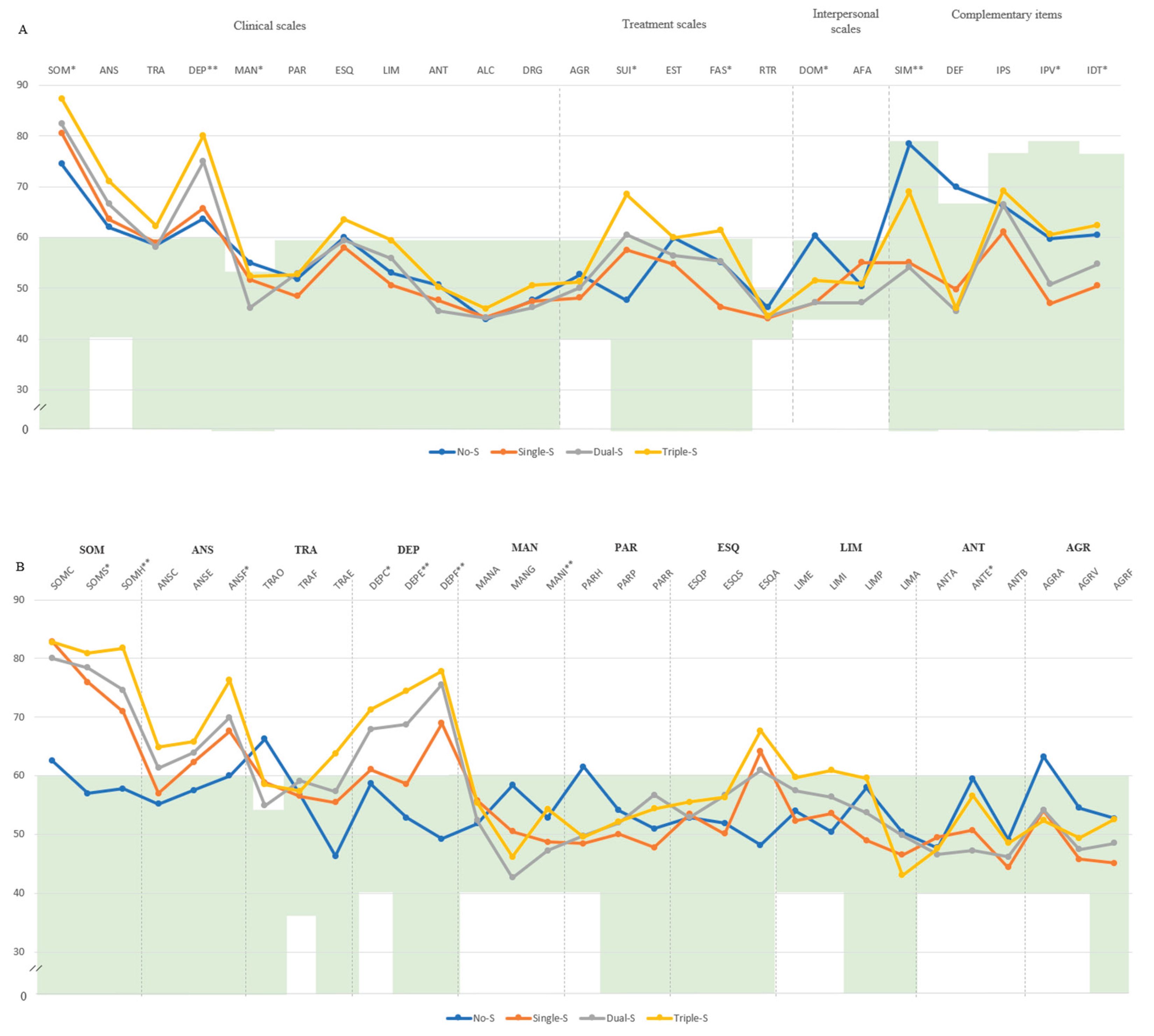

Moving to group comparison, in the Triple-S group, participants displayed notably higher scores compared to those in the Double-S group, particularly for SOM (M=87.0, SD=8.44 vs. M=82.7, SD=8.9), DEP: M=80.10, SD=7.78 vs. M=74.94, SD=7.47), SUI (M=68.50, SD=19.02 vs. M=60.57, SD=16.41). In contrast, within the No-S group, MAN (M=55.00, SD=9.75) and DOM (M=60.36, SD=12.71) presented scores outside the normal range. The graded increase in severity across groups was clearly evident, with the Triple-S group consistently surpassing Double-S and Single-S in symptom burden. This pattern was particularly pronounced in subscales such as SOM-S (M=80.90, SD=6.29), SOM-H (M=81.80, SD=9.94), ANS-F (M=76.30, SD=8.24), DEP-C (M=71.30, SD=10.89), DEP-E (M=74.50, SD=10.77), and DEP-F (M=77.80, SD=7.58), all significantly elevated compared to the No-S group (seen

Figure A1). Additionally, Triple-S was associated with the highest prevalence percentage of bipolar II depression (100%), somatoform disorder (100%), dysthymia (90%), and persistent depression with major depression (90%). On the other hand, Dual-S showed the highest prevalence for major depression (88.57%), adaptative disorder (97.14%), and passive-aggressive traits (45.71%) and Single-S for conversive disorder (64.29%) (see

Figure A2).

4. Discussion

The findings of this study show distinct psychological profiles according to the type and severity of functional, physical, and emotional impairment. Individuals with Func-S exhibited higher levels of negative impression, somatic complaints, emotional depressive symptoms, emotional instability, physical aggression, and treatment resistance, along with increased diagnoses of depressive and somatic disorders. In the Phys-S cluster somatic and depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, manic traits (especially related to activity levels), and psychotic experiences predominated. These participants also exhibited higher rates of adaptive functioning difficulties, disorganized schizophrenia traits, somatic disorders, and bipolar II-related depressive and manic episodes. In the Emot-S cluster, the clinical profile was characterized by cognitive, emotional, and physiological depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, somatization, and lower defensiveness, with a notable increase in diagnoses of depressive disorders, somatic disorders, persistent depression with or without major depression. Finally, cumulative severity was associated with greater psychological impairment. The Triple-S group showed the highest scores in somatization, depression, negative impression, and physical anxiety. This cumulative severity was also accompanied by a higher number of clinical diagnoses like depression, somatoform and persistent depression with and without major depression.

In line with the elevated emotional instability and depressive symptoms observed in the Func-S group, severe functional impairment was closely linked to cognitive overload and executive dysfunctions, including attention, memory, and decision-making difficulties (Castel et al., 2021), which contribute to daily limitations beyond physical symptoms (Jacobsen et al., 2023). Occupational difficulties were central, as work absence a greater psychological toll than general physical limitations, reflecting the profound impact of occupational identity loss on self-esteem and well-being (Berk et al. 2020; Chang et al. 2019; Chang et al. 2019; Van Alboom et al. 2021). Social withdrawal and interpersonal strain further exacerbated emotional distress and isolation, perpetuating a vicious cycle of functional decline and increased suicidality risk (Gil-Ugidos et al., 2021; Levine et al., 2020; Martínez et al., 2021). Additionally, barriers to treatment adherence —both emotional and practical—compounded this complex clinical picture (Bulu et al., 2023; Campos et al., 2021; Sarzi-Puttini et al., 2021). These findings underscore the need for integrative interventions combining work reintegration strategies, cognitive rehabilitation, structured social support, and meaningful alternatives to occupational (Castel et al., 2021; Gil-Ugidos et al., 2021; Van Alboom et al., 2021).

Consistent with the elevated somatic, depressive, and psychotic symptoms observed in the Phys-S group, severe physical impairment was linked to intensified pain perception, mood instability, and psychotic-like experiences, suggesting sensory and autonomic dysregulation as key mechanisms (Islam et al., 2022; Nadal-Nicolás et al., 2020). Central sensitization likely underlies the excessive somatic symptoms (Bhargava & Goldin 2025; Gelonch et al., 2018; Siracusa et al., 2021;), while autonomic dysfunctions such as orthostatic intolerance (Alsiri et al., 2023) and temperature dysregulation (Islam et al., 2022) further compromise physical capacity. Immune dysregulation (García-Domínguez, 2025) and chronic inflammation have also been associated with heightened pain, fatigue, and depressive symptoms, underscoring the interplay between physical and psychiatric manifestations (Meade & Garvey, 2022). Behaviorally, pain-related activity avoidance due to kinesiophobia contributed to deconditioning and functional decline (Serrat et al., 2021; Inal et al., 2020), highlighting the need for targeted movement therapies (Bravo et al., 2019; Serrat et al., 2021). Psychotic-like features, including disorganized schizophrenia traits (Almulla et al., 2020), may reflect stress-related cognitive-perceptual disturbances (Bulu et al., 2023) rather than primary psychosis (Zinchuk et al., 2025). The presence of both depressive and manic traits, often linked to bipolar II-related episodes (Bortolato et al., 2016; Dell’Osso et al., 2009; Gota et al., 2015), calls for integrated interventions targeting mood regulation (Kudlow et al., 2025) alongside physical rehabilitation (Araújo et al., 2019; Serrat et al., 2021).

Individuals in the Emot-S group exhibited pervasive depressive symptoms (Wolfe et al., 1999; Yuan et al., 2015), stress hypersensitivity (Lahat-Birka et al., 2024), and maladaptive coping strategies (Conversano et al., 2019), reinforcing the biopsychosocial model of FM (Wolfe et al., 2021). Diagnoses of persistent depression and major depression, alongside high rates of suicidal ideation, suggest that emotional distress is likely associated with serotonergic and dopaminergic dysregulation, mood instability, motivational deficits (Doreste et al., 2025; Estévez-López et al., 2019; Sedda et al., 2025), and pain sensitization (Ansari et al., 2021). Furthermore, maladaptive cognitive-emotional processes such as cognitive distortions (Vittersø et al., 2022), negative bias (Zetterman et al., 2021), catastrophizing (Izquierdo-Alventosa et al., 2020), and somatic amplification (Vittersø et al., 2022) maintain a psychosomatic loop in which emotional distress both stems from and worsens FM symptoms (Araújo et al., 2019). Autonomic overactivation (Goldway et al., 2022) and exaggerated stress responses (Arslan et al., 2021) further heighten pain perception and psychological burden. Social and interpersonal difficulties, including defensiveness (Berk et al., 2020; Romeo et al., 2022b) and low social support (Cagliyan et al., 2024; Galvez-Sanchez et al., 2020; Gonzalez et al., 2020; Pacheco-Barrios et al., 2024), further exacerbate emotional suffering and isolation. Given this complex interplay, interventions should extend beyond conventional mood treatments (Castel et al., 2021; Hirsch et al., 2020) to incorporate emotional regulation training (Trucharte et al., 2020), relational and social support approaches (Puşuroğlu et al., 2023), and strategies targeting the neurobiological mechanisms underlying FM’s emotional dimension (Al Sharie et al., 2024).

The overlap of severe functional, physical, and emotional impairment in the Triple-S group highlights that severity impact in FM reflects accumulated biopsychosocial risk factors. Rather than being additive, combined impairments intensify somatization, depression, and anxiety, though not personality traits. Shared psychological mechanisms: likely drive this pattern: learned helplessness may underlie functional decline, while pain catastrophizing and body vigilance exacerbate physical symptoms and distress. Emotional impairment is further reinforced by affective dysregulation, chronic stress, and maladaptive coping. These findings underscore the need for integrated, multidisciplinary interventions targeting cognitive, emotional, and behavioral factors alongside physical health to improve outcomes (Hirsch et al. 2019).

This study has limitations that should be considered. Cross-sectional design prevents establishing causality between psychological factors and FM symptoms. Self-reported measures, including the PAI and the FIQ, may introduce biases such as social desirability and recall errors. The sample size, while sufficient for analysis, may limit generalizability. Additionally, unmeasured confounders like medication use, comorbid conditions, and coping strategies could influence results. Future longitudinal studies with larger, more diverse samples and other objective assessments are needed to confirm these findings.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights distinct psychological profiles based on the type and severity of functional, physical, and emotional impairment in individuals with fibromyalgia (FM), with important clinical implications. Each group—Func-S, Phys-S, Emot-S, and Triple-S—exhibited unique patterns of symptoms and psychiatric diagnoses, all reflecting a complex interplay of biopsychosocial factors. Cumulative severity, as seen in the Triple-S group, was associated with greater psychological and clinical impairment, emphasizing the need for integrated treatment approaches that simultaneously address physical, emotional, and cognitive dimensions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D. and J.P.; methodology, E.P.; validation, V.P.; formal analysis, A.D.; investigation, F.O., J.M., G.M.-V., and H.P.-T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D and J.D.; writing—review and editing, L.B.-H. and J.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received partial support from the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain (Grant PID2021-127703OB-I00, MICIU/AEI/10.130391/501100011033 and FEDER/UE) and the Agency of University and Research Funding Management of the Catalonia Government within the Research Groups SGR 2017/00717 framework.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research followed the guidelines set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and obtained approval from the Ethical Committees: Parc de Salut Mar of Barcelona (reference 6932/I) and the Commission on Ethics in Animal and Human Experimentation (CEEAH) at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) (reference 6496).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was acquired from all participating patients.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

This is a figure. Schemes follow the same formatting. Note. (A) Comparison between groups in PAI scales and complementary items; (B) Comparison between groups in PAI subscales. The green zone indicates the ranges of normality, according to the psychometric criteria of the PAI. SOM: Somatic Complaints; ANS: Anxiety; TRA: Disorders Related to Anxiety; DEP: Depression; MAN: Mania; PAR: Paranoia; ESQ: Schizophrenia; LIM: Limit Traits; ANT: Antisocial Traits; ALC: Problems with alcohol; DRG: Problems with drugs; AGR: Aggression: SUI: Suicidal Ideation; EST: Stress; FAS: Lack of social support; RTR: Refusal to treatment; DOM: Dominance; AFA: Affability; SIM: Simulation Index; DEF: Defensiveness Index; IPS: Potential Suicide Index; IPV: Potential index of violence; IDT: Treatment Difficulty Index; No-S: patients not classified as severe in any domain; Single-S: patients classified as severe in one domain; Dual-S: patients classified as severe in two domains; Triple-S: patients classified as severe in all three domains; (B). Note: SOM-C: Conversion; SOM-S: Somatization; SOM-H: Hypochondria; ANS-C: Cognitive; ANS-E: Emotional; ANS-F: Physiological; TRA-O: Obsessive-compulsive; TRA-F: Phobias; TRA-E: Posttraumatic Stress; DEP-C: Cognitive; DEP-E: Emotional; DEP-F: Physiological; MAN-A: Activity level; MAN-G: Grandeur; MAN-I: Irritability; PAR-H: Hypervigilance; PAR-P: Persecution; PAR-R: Resentment; ESQ-P: Experiences. Psychotics; ESQ-S: Social Indifference; ESQ-A: Alteration of the Thought; LIM-E: Emotional instability; LIMI: Alteration of identity; LIM-P: Problematic Interpersonal Relationships; LIM-A: Self-aggression; ANT-A: Antisocial Behaviors; ANT-E: Egocentrism; ANT-B: Search for sensations; AGR-A: Attitude aggressive; AGR-V: Verbal aggression; AGR-F: Physical assaults; * statistically significant differences between all groups; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Figure A1.

This is a figure. Schemes follow the same formatting. Note. (A) Comparison between groups in PAI scales and complementary items; (B) Comparison between groups in PAI subscales. The green zone indicates the ranges of normality, according to the psychometric criteria of the PAI. SOM: Somatic Complaints; ANS: Anxiety; TRA: Disorders Related to Anxiety; DEP: Depression; MAN: Mania; PAR: Paranoia; ESQ: Schizophrenia; LIM: Limit Traits; ANT: Antisocial Traits; ALC: Problems with alcohol; DRG: Problems with drugs; AGR: Aggression: SUI: Suicidal Ideation; EST: Stress; FAS: Lack of social support; RTR: Refusal to treatment; DOM: Dominance; AFA: Affability; SIM: Simulation Index; DEF: Defensiveness Index; IPS: Potential Suicide Index; IPV: Potential index of violence; IDT: Treatment Difficulty Index; No-S: patients not classified as severe in any domain; Single-S: patients classified as severe in one domain; Dual-S: patients classified as severe in two domains; Triple-S: patients classified as severe in all three domains; (B). Note: SOM-C: Conversion; SOM-S: Somatization; SOM-H: Hypochondria; ANS-C: Cognitive; ANS-E: Emotional; ANS-F: Physiological; TRA-O: Obsessive-compulsive; TRA-F: Phobias; TRA-E: Posttraumatic Stress; DEP-C: Cognitive; DEP-E: Emotional; DEP-F: Physiological; MAN-A: Activity level; MAN-G: Grandeur; MAN-I: Irritability; PAR-H: Hypervigilance; PAR-P: Persecution; PAR-R: Resentment; ESQ-P: Experiences. Psychotics; ESQ-S: Social Indifference; ESQ-A: Alteration of the Thought; LIM-E: Emotional instability; LIMI: Alteration of identity; LIM-P: Problematic Interpersonal Relationships; LIM-A: Self-aggression; ANT-A: Antisocial Behaviors; ANT-E: Egocentrism; ANT-B: Search for sensations; AGR-A: Attitude aggressive; AGR-V: Verbal aggression; AGR-F: Physical assaults; * statistically significant differences between all groups; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Figure A2.

Comparison of PAI-based psychopathology (top) and personality disorder (down) profiles between cumulative severity groups by FIQ. Note. (A) PAI psychopathology profiles. (B) PAI personality diagnoses. No-S: fibromyalgia absence of cluster severity; Single-S: fibromyalgia one cluster severity; Dual-S: fibromyalgia two cluster severities; Triple-M: fibromyalgia three cluster severities. Statistical significances: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Figure A2.

Comparison of PAI-based psychopathology (top) and personality disorder (down) profiles between cumulative severity groups by FIQ. Note. (A) PAI psychopathology profiles. (B) PAI personality diagnoses. No-S: fibromyalgia absence of cluster severity; Single-S: fibromyalgia one cluster severity; Dual-S: fibromyalgia two cluster severities; Triple-M: fibromyalgia three cluster severities. Statistical significances: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

References

- Aghbelaghi DT, Jalali M, Tayim N, Kiyani R. A Network Analysis of Depression and Cognitive Impairments in Fibromyalgia: A Secondary Analysis Study. Psychiatr Q. 2024 Nov 26. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Adawi M, Chen W, Bragazzi NL, Watad A, McGonagle D, Yavne Y, Kidron A, Hodadov H, Amital D, Amital H. Suicidal Behavior in Fibromyalgia Patients: Rates and Determinants of Suicide Ideation, Risk, Suicide, and Suicidal Attempts-A Systematic Review of the Literature and Meta-Analysis of Over 390,000 Fibromyalgia Patients. Front Psychiatry. 2021 Nov 19;12:629417. [CrossRef]

- Al Sharie S, Varga SJ, Al-Husinat L, Sarzi-Puttini P, Araydah M, Bal'awi BR, Varrassi G. Unraveling the Complex Web of Fibromyalgia: A Narrative Review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024 Feb 4;60(2):272. [CrossRef]

- Almulla AF, Al-Hakeim HK, Abed MS, Carvalho AF, Maes M. Chronic fatigue and fibromyalgia symptoms are key components of deficit schizophrenia and are strongly associated with activated immune-inflammatory pathways. Schizophr Res. 2020 Aug;222:342-353. Epub 2020 May 26. [CrossRef]

- Alsiri N, Alhadhoud M, Alkatefi T, Palmer S. The concomitant diagnosis of fibromyalgia and connective tissue disorders: A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2023 Feb;58:152127. Epub 2022 Nov 17. [CrossRef]

- Ansari AH, Pal A, Ramamurthy A, Kabat M, Jain S, Kumar S. Fibromyalgia Pain and Depression: An Update on the Role of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2021 Jan 20;12(2):256-270. Epub 2021 Jan 4. [CrossRef]

- Araújo FM, DeSantana JM. Physical therapy modalities for treating fibromyalgia. F1000Res. 2019 Nov 29;8:F1000 Faculty Rev-2030. [CrossRef]

- Arslan D, Ünal Çevik I. Interactions between the painful disorders and the autonomic nervous system. Agri. 2022 Jul;34(3):155-165. English. [CrossRef]

- Attademo L, Bernardini F. Prevalence of personality disorders in patients with fibromyalgia: a brief review. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018 Sep;19(5):523-528. Epub 2017 Dec 22. [CrossRef]

- Bair MJ, Krebs EE. Fibromyalgia. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Mar 3;172(5):ITC33-ITC48. [CrossRef]

- Berk E, Baykara S. The relationship between disease severity and defense mechanisms in fibromyalgia syndrome. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020 Mar 3;66(1):47-53. [CrossRef]

- Berwick R, Barker C, Goebel A; guideline development group. The diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome. Clin Med (Lond). 2022 Nov;22(6):570-574. [CrossRef]

- Bhargava J, Goldin J. Fibromyalgia. 2025 Jan 31. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–.

- Bortolato B, Berk M, Maes M, McIntyre RS, Carvalho AF. Fibromyalgia and Bipolar Disorder: Emerging Epidemiological Associations and Shared Pathophysiology. Curr Mol Med. 2016;16(2):119-36. [CrossRef]

- Bravo C, Skjaerven LH, Guitard Sein-Echaluce L, Catalan-Matamoros D. Effectiveness of movement and body awareness therapies in patients with fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2019 Oct;55(5):646-657. Epub 2019 May 15. [CrossRef]

- Brown T, Hammond A, Ching A, Parker J. Work limitations and associated factors in rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia. Musculoskeletal Care. 2023 Sep;21(3):827-844. Epub 2023 Mar 28. PMID: 36975543. [CrossRef]

- Bucourt E., Martaille V., Goupille P., Joncker-Vannier I., Huttenberger B., et al.. A Comparative Study of Fibromyalgia, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Spondyloarthritis, and Sjögren’s Syndrome; Impact of the Disease on Quality of Life, Psychological Adjustment, and Use of Coping Strategies. Pain Medicine, 2021, 22 (2), pp.372-381. 10.1093/pm/pnz255.

- Bulu A, Onalan E, Korkmaz S, Yakar B, Karatas TK, Guven T, Karatas A, Koca SS, Atlı H, Donder E. Attitude towards seeking psychological help regarding psychiatric symptoms and stigma in patients with fibromyalgia. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023 Nov;27(21):10661-10668. [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM. The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire: development and validation. J Rheumatol. 1991;18(5):728–33.

- Burneo-Garcés C, Fernández-Alcántara M, Aguayo-Estremera R, Pérez-García M. Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Adaptation of the Personality Assessment Inventory in Correctional Settings: An ESEM Study. J Pers Assess. 2020;102(1):75–87. [CrossRef]

- Cagliyan Turk A, Erden E, Eker Buyuksireci D, Umaroglu M, Borman P. Prevalence of Fibromyalgia Syndrome in Women with Lipedema and Its Effect on Anxiety, Depression, and Quality of Life. Lymphat Res Biol. 2024 Feb;22(1):2-7. Epub 2023 Dec 22. [CrossRef]

- Campos RP, Vázquez I, Vilhena E. Clinical, psychological and quality of life differences in fibromyalgia patients from secondary and tertiary healthcare. Eur J Pain. 2021 Mar;25(3):558-572. Epub 2020 Dec 3. [CrossRef]

- Castel A, Cascón-Pereira R, Boada S. Memory complaints and cognitive performance in fibromyalgia and chronic pain: The key role of depression. Scand J Psychol. 2021 Jun;62(3):328-338. Epub 2021 Feb 4. [CrossRef]

- Chang EC, Lucas AG, Chang OD, Angoff HD, Li M, Duong AH, Huang J, Perera MJ, Sirois FM, Hirsch JK. Relationship between Future Orientation and Pain Severity in Fibromyalgia Patients: Self-Compassion as a Coping Mechanism. Soc Work. 2019 Jul 2;64(3):253-258. [CrossRef]

- Ciuffini R, Cofini V, Muselli M, Necozione S, Piroli A, Marrelli A. Emotional arousal and valence in patients with fibromyalgia: a pilot study. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2023 May 31;4:1075722. [CrossRef]

- Conversano C, Carmassi C, Bertelloni CA, Marchi L, Micheloni T, Carbone MG, Pagni G, Tagliarini C, Massimetti G, Bazzichi LM, Dell'Osso L. Potentially traumatic events, post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic stress spectrum in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019 Jan-Feb;37 Suppl 116(1):39-43. Epub 2018 Apr 24.

- Creed F. The risk factors for self-reported fibromyalgia with and without multiple somatic symptoms: The Lifelines cohort study. J Psychosom Res. 2022 Apr;155:110745. Epub 2022 Jan 30. [CrossRef]

- Dell'Osso L, Bazzichi L, Consoli G, Carmassi C, Carlini M, Massimetti E, Giacomelli C, Bombardieri S, Ciapparelli A. Manic spectrum symptoms are correlated to the severity of pain and the health-related quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009 Sep-Oct;27(5 Suppl 56):S57-61.

- Dizner-Golab A, Lisowska B, Kosson D. Fibromyalgia - etiology, diagnosis and treatment including perioperative management in patients with fibromyalgia. Reumatologia. 2023;61(2):137-148. Epub 2023 May 10. [CrossRef]

- Doreste A, Pujol J, Penelo E, Pérez V, Blanco-Hinojo L, Martínez-Vilavella G, Pardina-Torner H, Ojeda F, Monfort J, Deus J. Exploring the psychopathological profile of fibromyalgia: insights from the personality assessment inventory and its association with disease impact. Front Psychol. 2024 Sep 12;15:1418644. [CrossRef]

- Doreste A, Pujol J, Penelo E, Pérez V, Blanco-Hinojo L, Martínez-Vilavella G, Pardina-Torner H, Ojeda F, Monfort J, Deus J. Outlining the Psychological Profile of Persistent Depression in Fibromyalgia Patients Through Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI). Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2025 Jan 6;15(1):2. [CrossRef]

- Estévez-López F, Rodriguez-Ayllon M, Soriano-Maldonado A, Acosta-Manzano P, Segura-Jiménez V, Álvarez-Gallardo IC, Pulido-Martos M, Herrador-Colmenero M, Geenen R, Carbonell-Baeza A, Delgado-Fernández M. Lower Fatigue in Fit and Positive Women with Fibromyalgia: The al-Ándalus Project. Pain Med. 2019 Dec 1;20(12):2506-2515. [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Jbali LR, Montoro CI, Montoya P, Halder W, Duschek S. Central nervous activity during an emotional Stroop task in fibromyalgia syndrome. Int J Psychophysiol. 2022 Jul;177:133-144. Epub 2022 May 16. [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Jbali LR, Montoro CI, Montoya P, Halder W, Duschek S. Central nervous activity during implicit processing of emotional face expressions in fibromyalgia syndrome. Brain Res. 2021 May 1;1758:147333. Epub 2021 Feb 2. [CrossRef]

- Font Gayà T, Bordoy Ferrer C, Juan Mas A, Seoane-Mato D, Álvarez Reyes F, Delgado Sánchez M, Martínez Dubois C, Sánchez-Fernández SA, Marena Rojas Vargas L, García Morales PV, Olivé A, Rubio Muñoz P, Larrosa M, Navarro Ricós N, Sánchez-Piedra C, Díaz-González F, Bustabad-Reyes S; Working Group Proyecto EPISER2016. Prevalence of fibromyalgia and associated factors in Spain. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020 Jan-Feb;38 Suppl 123(1):47-52. Epub 2020 Jan 8.

- Galvez-Sánchez CM, Duschek S, Reyes Del Paso GA. Psychological impact of fibromyalgia: current perspectives. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019 Feb 13;12:117-127. [CrossRef]

- Galvez-Sánchez CM, Reyes Del Paso GA. Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia: Critical Review and Future Perspectives. J Clin Med. 2020 Apr 23;9(4):1219. [CrossRef]

- García-Domínguez M. Fibromyalgia and Inflammation: Unrevealing the Connection. Cells. 2025 Feb 13;14(4):271. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Fontanals A, Portell M, García-Blanco S, Poca-Dias V, García-Fructuoso F, López-Ruiz M, Gutiérrez-Rosado T, Gomà-I-Freixanet M, Deus J. Vulnerability to Psychopathology and Dimensions of Personality in Patients With Fibromyalgia. Clin J Pain. 2017 Nov;33(11):991-997. [CrossRef]

- Garİp Y, GÜler T, Bozkurt Tuncer Ö, Önen S. Type D Personality is Associated With Disease Severity and Poor Quality of Life in Turkish Patients With Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Study. Arch Rheumatol. 2019 Nov 6;35(1):13-19. [CrossRef]

- Gelonch O, Garolera M, Valls J, Castellà G, Varela O, Rosselló L, Pifarre J. The effect of depressive symptoms on cognition in patients with fibromyalgia. PLoS One. 2018 Jul 5;13(7):e0200057. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Ugidos A, Rodríguez-Salgado D, Pidal-Miranda M, Samartin-Veiga N, Fernández-Prieto M, Carrillo-de-la-Peña MT. Working Memory Performance, Pain and Associated Clinical Variables in Women With Fibromyalgia. Front Psychol. 2021 Oct 21;12:747533. [CrossRef]

- Goldway N, Petro NM, Ablin J, Keil A, Ben Simon E, Zamir Y, Weizman L, Greental A, Hendler T, Sharon H. Abnormal Visual Evoked Responses to Emotional Cues Correspond to Diagnosis and Disease Severity in Fibromyalgia. Front Behav Neurosci. 2022 May 4;16:852133. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez B, Novo R, Ferreira AS. Fibromyalgia: heterogeneity in personality and psychopathology and its implications. Psychol Health Med. 2020 Jul;25(6):703-709. Epub 2019 Nov 24. [CrossRef]

- Gota CE, Kaouk S, Wilke WS. The impact of depressive and bipolar symptoms on socioeconomic status, core symptoms, function and severity of fibromyalgia. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017 Mar;20(3):326-339. Epub 2015 Jul 31. [CrossRef]

- Hadlandsmyth K, Dailey DL, Rakel BA, Zimmerman MB, Vance CG, Merriwether EN, Chimenti RL, Geasland KM, Crofford LJ, Sluka KA. Somatic symptom presentations in women with fibromyalgia are differentially associated with elevated depression and anxiety. J Health Psychol. 2020 May;25(6):819-829. Epub 2017 Oct 2. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch JK, Altier HR, Offenbächer M, Toussaint L, Kohls N, Sirois FM. Positive Psychological Factors and Impairment in Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Disease: Do Psychopathology and Sleep Quality Explain the Linkage? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021 Jan;73(1):55-64. Epub 2020 Dec 4. [CrossRef]

- İnal Ö, Aras B, Salar S. Investigation of the relationship between kinesiophobia and sensory processing in fibromyalgia patients. Somatosens Mot Res. 2020 Jun;37(2):92-96. Epub 2020 Mar 25. [CrossRef]

- Islam Z, D'Silva A, Raman M, Nasser Y. The role of mind body interventions in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Dec 22;13:1076763. [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Alventosa R, Inglés M, Cortés-Amador S, Gimeno-Mallench L, Chirivella-Garrido J, Kropotov J, Serra-Añó P. Low-Intensity Physical Exercise Improves Pain Catastrophizing and Other Psychological and Physical Aspects in Women with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 May 21;17(10):3634. [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen HB, Brun A, Stubhaug A, Reme SE. Stress specifically deteriorates working memory in peripheral neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia. Brain Commun. 2023 Jul 5;5(4):fcad194. [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Priego LN, Cueto-Ureña C, Ramírez-Expósito MJ, Martínez-Martos JM. Fibromyalgia: A Review of the Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Multidisciplinary Treatment Strategies. Biomedicines. 2024 Jul 11;12(7):1543. [CrossRef]

- Karlin BE, Creech SK, Grimes JS, Clark TS, Meagher MW, Morey L. The personality assessment inventory with chronic pain patients: psychometric properties and clinical utility. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61(12):1571–85. [CrossRef]

- Keller D, de Gracia M, Cladellas R. Subtipos de pacientes con fibromialgia, características psicopatológicas y calidad de vida [Subtypes of patients with fibromyalgia, psychopathological characteristics and quality of life]. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2011 Sep-Oct;39(5):273-9. Spanish. Epub 2011 Sep 1.

- Kim S, Dowgwillo EA, Kratz AL. Emotional Dynamics in Fibromyalgia: Pain, Fatigue, and Stress Moderate Momentary Associations Between Positive and Negative Emotions. J Pain. 2023 Sep;24(9):1594-1603. Epub 2023 Apr 23. [CrossRef]

- Kocyigit BF, Akyol A. Fibromyalgia syndrome: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Reumatologia. 2022;60(6):413-421. Epub 2022 Dec 30. [CrossRef]

- Kudlow PA, Rosenblat JD, Weissman CR, Cha DS, Kakar R, McIntyre RS, Sharma V. Prevalence of fibromyalgia and co-morbid bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2015 Dec 1;188:134-42. Epub 2015 Sep 2. [CrossRef]

- Lahat-Birka N, Boussi-Gross R, Ben Ari A, Efrati S, Ben-David S. Retrospective Analysis of Fibromyalgia: Exploring the Interplay Between Various Triggers and Fibromyalgia's Severity. Clin J Pain. 2024 Oct 1;40(10):578-587. PMID: 39099287. [CrossRef]

- Levine D, Horesh D. Suicidality in Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Sep 23;11:535368. [CrossRef]

- López-Ruiz M, Losilla JM, Monfort J, Portell M, Gutiérrez T, Poca V, et al. Central sensitization in knee osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia: Beyond depression and anxiety. PLoSONE. 2019;: p. 14(12).

- Luciano JV, Forero CG, Cerdà-Lafont M, Peñarrubia-María MT, Fernández-Vergel R, Cuesta-Vargas AI, Ruíz JM, Rozadilla-Sacanell A, Sirvent-Alierta E, Santo-Panero P, García-Campayo J, Serrano-Blanco A, Pérez-Aranda A, Rubio-Valera M. Functional Status, Quality of Life, and Costs Associated With Fibromyalgia Subgroups: A Latent Profile Analysis. Clin J Pain. 2016 Oct;32(10):829-40. [CrossRef]

- Martínez MP, Sánchez AI, Cáliz R, Miró E. Psychopathology as a Moderator of the Relationship Between Physical Symptoms and Impairment in Fibromyalgia Patients. Psicothema. 2021 May;33(2):214-221. [CrossRef]

- Maurel S, Giménez-Llort L, Alegre-Martin J, Castro-Marrero J. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis Based on Clinical and Neuropsychological Symptoms Reveals Distinct Subgroups in Fibromyalgia: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Biomedicines. 2023 Oct 23;11(10):2867. [CrossRef]

- Meade E, Garvey M. The Role of Neuro-Immune Interaction in Chronic Pain Conditions; Functional Somatic Syndrome, Neurogenic Inflammation, and Peripheral Neuropathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Aug 2;23(15):8574. [CrossRef]

- Monterde S, Salvat I, Montull S, Fernández-Ballart J. Validation of the Spanish version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire. Rev Esp Reumatol, 2004;31(9):507-513.

- Morey LC. Personality Assessment Inventory–Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1991.

- Morey LC, & Alarcón MOT. PAI: inventario de evaluación de la personalidad. Manual de corrección, aplicación e interpretación. TEA Ediciones, 2013.

- Munipalli B, Chauhan M, Morris AM, Ahmad R, Fatima M, Allman ME, Niazi SK, Bruce BK. Recognizing and Treating Major Depression in Fibromyalgia: A Narrative Primer for the Non-Psychiatrist. J Prim Care Community Health. 2024 Jan-Dec;15:21501319241281221. [CrossRef]

- Nadal-Nicolás Y, Rubio-Arias JÁ, Martínez-Olcina M, Reche-García C, Hernández-García M, Martínez-Rodríguez A. Effects of Manual Therapy on Fatigue, Pain, and Psychological Aspects in Women with Fibromyalgia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jun 26;17(12):4611. [CrossRef]

- Olfa S, Bouden S, Sahli M, Tekaya AB, Rouached L, Rawdha T, Mahmoud I, Abdelmoula L. Fibromyalgia in Spondyloarthritis: Prevalence and Effect on Disease Activity and Treatment. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2023;19(2):214-221. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Tallo M, Cardenal V, Ferragut M, Cerezo MV (2011). Personalidad y síndromes clínicos: un estudio con el MCMI-III basado en una muestra española. Rev Psicopatol Psicol Clín, 2011;16 (1): 49. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Barrios K, Teixeira PEP, Martinez-Magallanes D, Neto MS, Pichardo EA, Camargo L, Lima D, Cardenas-Rojas A, Fregni F. Brain compensatory mechanisms in depression and memory complaints in fibromyalgia: the role of theta oscillatory activity. Pain Med. 2024 Aug 1;25(8):514-522. [CrossRef]

- Pallanti S, Porta F, Salerno L. Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: Assessment and disabilities. J Psychiatr Res. 2021 Apr;136:537-542. Epub 2020 Oct 24. [CrossRef]

- Pujol J, Blanco-Hinojo L, Doreste A, Ojeda F, Martinez-Vilavella G, Pérez-Sola V, et al. Distinctive alterations in the functional anatomy of the cerebral cortex in pain-sensitized osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2022; 24:252.

- Pujol J, Macià D, Garcia-Fontanals A, Blanco-Hinojo L, López-Solà M, Garcia-Blanco S, et al. The contribution of sensory system functional connectivity reduction to clinical pain in fibromyalgia. Pain. 2014 April; 155(1492-1503).

- Puşuroğlu M, Topaloğlu MS, Hocaoğlu Ç, Yıldırım M. Expressing emotions, rejection sensitivity, and attachment in patients with fibromyalgia. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2023 Jun 4;69(3):303-308. [CrossRef]

- Rivera J, González T. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire: A validated Spanish version to assess the health status in women with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol,2004;22:554-560.

- Rizzi M, Radovanovic D, Santus P, Airoldi A, Frassanito F, Vanni S, Cristiano A, Masala IF, Sarzi-Puttini P. Influence of autonomic nervous system dysfunction in the genesis of sleep disorders in fibromyalgia patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017 May-Jun;35 Suppl 105(3):74-80. Epub 2017 Jun 29. [CrossRef]

- Robbins JM, Kirmayer LJ, Kapusta MA. Illness worry and disability in fibromyalgia syndrome. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1990;20(1):49-63. [CrossRef]

- Romanov DV, Nasonova TI, Isaikin AI, Filileeva OV, Sheyanov AM, Iuzbashian PG, Voronova EI, Parfenov VA. Personality Disorders and Traits of ABC Clusters in Fibromyalgia in a Neurological Setting. Biomedicines. 2023 Nov 28;11(12):3162. [CrossRef]

- Romeo A, Benfante A, Geminiani GC, Castelli L. Personality, Defense Mechanisms and Psychological Distress in Women with Fibromyalgia. Behav Sci (Basel). 2022 Jan 7;12(1):10. [CrossRef]

- Romeo A, Tesio V, Ghiggia A, Di Tella M, Geminiani GC, Farina B, Castelli L. Traumatic experiences and somatoform dissociation in women with fibromyalgia. Psychol Trauma. 2022 Jan;14(1):116-123. Epub 2021 Mar 1. [CrossRef]

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Giorgi V, Marotto D, Atzeni F. Fibromyalgia: an update on clinical characteristics, aetiopathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020 Nov;16(11):645-660. Epub 2020 Oct 6. [CrossRef]

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Giorgi V, Atzeni F, Gorla R, Kosek E, Choy EH, Bazzichi L, Häuser W, Ablin JN, Aloush V, Buskila D, Amital H, Da Silva JAP, Perrot S, Morlion B, Polati E, Schweiger V, Coaccioli S, Varrassi G, Di Franco M, Torta R, Øien Forseth KM, Mannerkorpi K, Salaffi F, Di Carlo M, Cassisi G, Batticciotto A. Diagnostic and therapeutic care pathway for fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021 May-Jun;39 Suppl 130(3):120-127. Epub 2021 Jun 21. [CrossRef]

- Sedda S, Cadoni MPL, Medici S, Aiello E, Erre GL, Nivoli AM, Carru C, Coradduzza D. Fibromyalgia, Depression, and Autoimmune Disorders: An Interconnected Web of Inflammation. Biomedicines. 2025 Feb 18;13(2):503. [CrossRef]

- Serrat M, Sanabria-Mazo JP, Almirall M, Musté M, Feliu-Soler A, Méndez-Ulrich JL, Sanz A, Luciano JV. Effectiveness of a Multicomponent Treatment Based on Pain Neuroscience Education, Therapeutic Exercise, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and Mindfulness in Patients With Fibromyalgia (FIBROWALK Study): A Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys Ther. 2021 Dec 1;101(12):pzab200. [CrossRef]

- Siracusa R, Paola RD, Cuzzocrea S, Impellizzeri D. Fibromyalgia: Pathogenesis, Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Treatment Options Update. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Apr 9;22(8):3891. [CrossRef]

- de Souza JB, Goffaux P, Julien N, Potvin S, Charest J, Marchand S. Fibromyalgia subgroups: profiling distinct subgroups using the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire. A preliminary study. Rheumatol Int. 2009 Mar;29(5):509-15. Epub 2008 Sep 27. [CrossRef]

- Taylor SS, Noor N, Urits I, Paladini A, Sadhu MS, Gibb C, Carlson T, Myrcik D, Varrassi G, Viswanath O. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Pain Ther. 2021 Dec;10(2):875-892. Erratum in: Pain Ther. 2021 Dec;10(2):893-894. Epub 2021 Jun 24. [CrossRef]

- Toussaint L, Vincent A, McAllister SJ, Whipple M. Intra- and Inter-Patient Symptom Variability in Fibromyalgia: Results of a 90-Day Assessment. Musculoskeletal Care. 2015 Jun;13(2):93-100. doi: 10.1002/msc.1090. Epub 2014 Nov 19.

- Trucharte A, Leon L, Castillo-Parra G, Magán I, Freites D, Redondo M. Emotional regulation processes: influence on pain and disability in fibromyalgia patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020 Jan-Feb;38 Suppl 123(1):40-46. Epub 2020 Jan 9.

- Van Alboom M, De Ruddere L, Kindt S, Loeys T, Van Ryckeghem D, Bracke P, Mittinty MM, Goubert L. Well-being and Perceived Stigma in Individuals With Rheumatoid Arthritis and Fibromyalgia: A Daily Diary Study. Clin J Pain. 2021 May 1;37(5):349-358. [CrossRef]

- Vincent A, Hoskin TL, Whipple MO, Clauw DJ, Barton DL, Benzo RP, Williams DA. OMERACT-based fibromyalgia symptom subgroups: an exploratory cluster analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014 Oct 16;16(5):463. [CrossRef]

- Vittersø AD, Halicka M, Buckingham G, Proulx MJ, Bultitude JH. The sensorimotor theory of pathological pain revisited. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022 Aug;139:104735. Epub 2022 Jun 12. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe F. Determinants of WOMAC function, pain and stiffness scores: evidence for the role of low back pain, symptom counts, fatigue and depression in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999 Apr;38(4):355-61. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe F, Rasker JJ. The Evolution of Fibromyalgia, Its Concepts, and Criteria. Cureus. 2021 Nov 29;13(11):e20010. [CrossRef]

- Yuan SL, Matsutani LA, Marques AP. Effectiveness of different styles of massage therapy in fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Man Ther. 2015 Apr;20(2):257-64. Epub 2014 Oct 5. [CrossRef]

- Zetterman T, Markkula R, Partanen JV, Miettinen T, Estlander AM, Kalso E. Muscle activity and acute stress in fibromyalgia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021 Feb 14;22(1):183. [CrossRef]

- Zinchuk M, Kustov G, Tumurov D, Zhuravlev D, Bryzgalova Y, Spryshkova M, Yakovlev A, Guekht A. Fibromyalgia in patients with non-psychotic mental disorders: Prevalence, associated factors and validation of a brief screening instrument. Eur J Pain. 2025 Feb;29(2):e4730. Epub 2024 Sep 17. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).