Submitted:

24 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

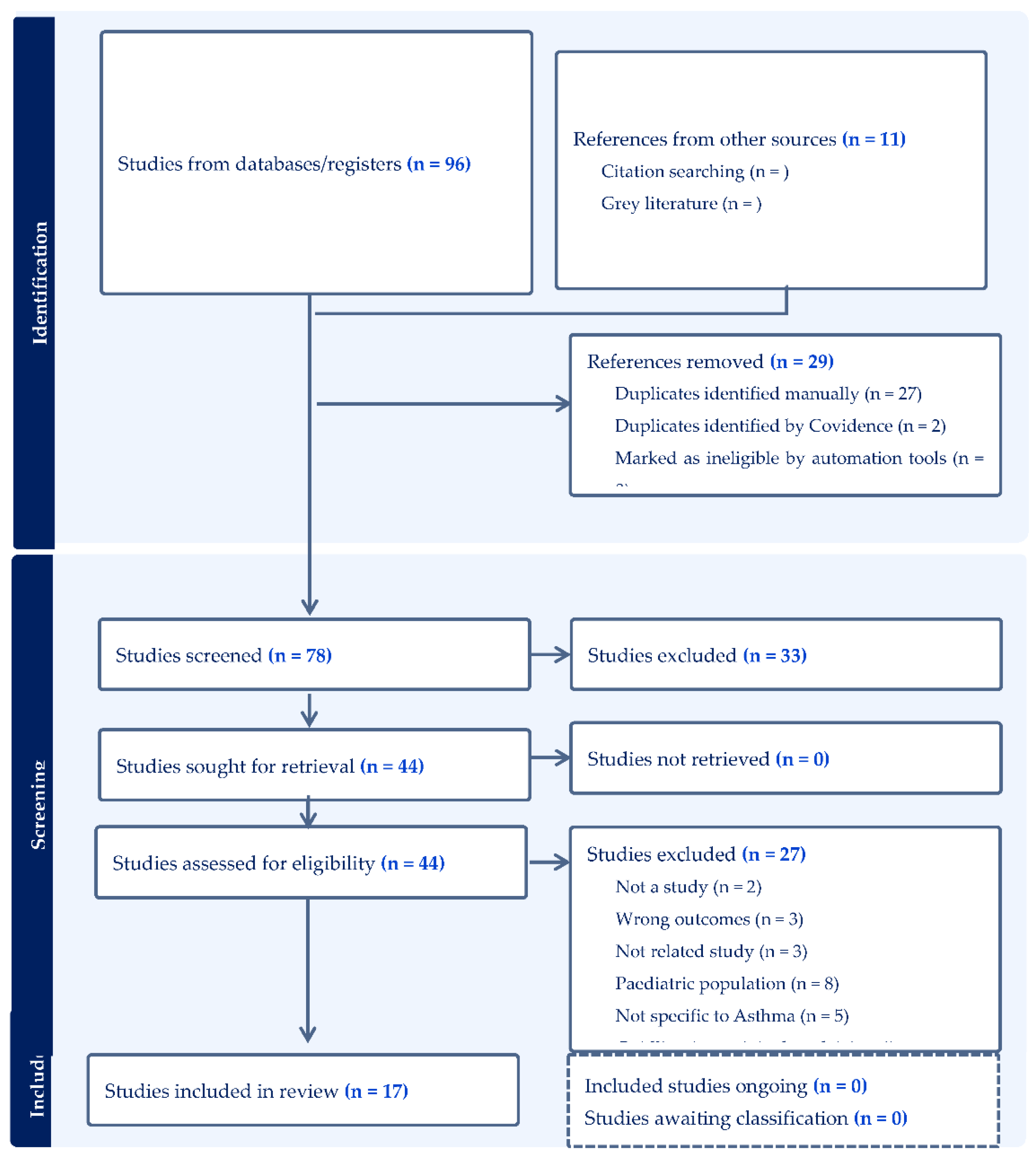

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

2.5. Exclusion Criteria

2.6. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.7. Inclusion Criteria

2.8. Exclusion Criteria

2.9. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.10. Inclusion Criteria

2.11. Exclusion Criteria

2.12. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

3. Results

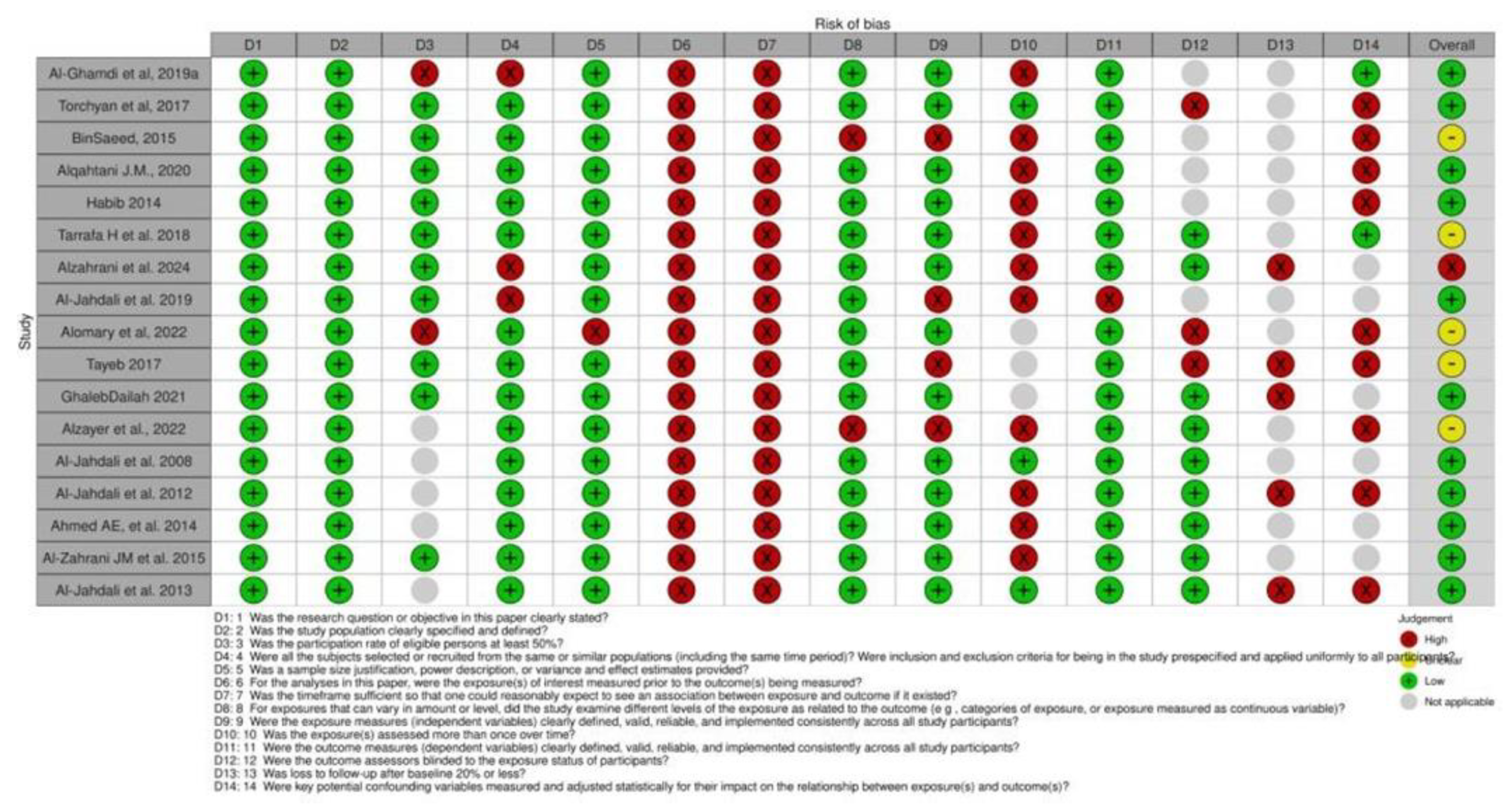

3.1. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

3.2. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.3. Prevalence of Asthma Control

3.4. Impact of Uncontrolled Asthma on Daily Life and Health-Related Outcomes

- Education

- Employment status

- Income level

- Gender differences

- Age and regional variation

- Environmental factors

- Tobacco Use

- Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalizations

- Quality of Life

- Adherence to Medication

- Asthma symptoms

| Author (year) | Age (years) | (Sex M/F) | Symptoms Control | ICS used? | Asthma Symptoms | Medication Regimen | Impact of asthma on Quality of life | Impact of Tobacco use on asthma control | Impact of Educational Level on asthma control | Other factors that may impact asthma control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ahmed AE, 2014) | 42.3 ±16.7 years | 176 (39.1%) and female participants were 274 (60.9%) |

significant difference in the asthma control scores for severe persistent asthma - (M = 8.5, SD = 2.0), - mild persistent (M = 18.0, SD = 2.3) - intermittent asthma (M = 19.3, SD = 3.1) |

50.4% of the participants used ICS |

Fourteen (3.1%) participants were considered to have severe persistent asthma, 75 (16.7%) participants were moderate persistent, 181 (40.2%) participants were mild persistent and 180 (40%) participants were mild intermittent. |

▪ half of the participants 203 (45.1%) use asthma device improperly. ▪ 266 (59.1%) claim that they received education about asthma medications ▪ 50.4% of the participants used ICS |

There is an association between frequent ED visits and poor asthma control from pervious studies. Participants with poor asthma control have poor health-related quality of life, more doctor and hospital visits |

NA | study did not find that demographic factors such as gender, marital status and level of education or job status were responsible for poor asthma control as defined by ACT. |

One possible explanation is probably that our patients have free access to hospitals and free dispensing of asthma therapy, which probably limits the influence of job status and income as a factor for poor asthma control |

|

(AlGhamdi et al., 2019) |

Adult (≥20 years of age) | NA |

persons with an increase in total IgE (>100 IU/mL) had significantly higher probability (OR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.10–3.06) to develop adult asthma. Similarly, those with an increase in total peripheral Eosinophil count (>150 cells/mm3 ) had more than two times the risk to have adult asthma (OR = 2.85, 95% CI: 1.14–7.15) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Rye wheat is an important outdoor sensitization factor for bronchial asthma in adults. |

| (AL-Jahdali et al, 2008) | median age was 38.56 years (range 15-75) | total number of patients studied was 1,060. Males comprised 442 (42%), and females comprised 618 (58%) |

ACT score revealed uncontrolled asthma in 667 (64%), well-controlled asthma in 383 (31%), and completely controlled in 55(5%). |

NA | NA | NA | of the major reasons for poor asthma control is poor compliance. |

NA | significant correlation between level of education and asthma control, 71% of patients who did not have formal education had uncontrolled asthma (p=0.001) |

younger age group (less than 20 years old) had better asthma control compared to the older age group (p=0.0001). |

| (AL-Jahdali et al, 2012) | 42.3 ±16.7 years | M= 176 (39.1%), F= 274 (60.9%) | NA |

Partially/Full controlled (n = 343) Level (ACT) -Regular ICS use Yes (80.6) No (72.4) Not controlled (n = 105) Level (P-Value) -Regular ICS use Yes (19.4) No (27.6) |

NA | NA |

Frequent emergency department visits | NA |

Partially/Full controlled (n = 343) Level (ACT) - Education level High school or less (77.2) University (72.1) Not controlled (n = 105) Level (P-Value) - Education level High school or less (22.8) University (27.9) |

-Lack of education about asthma. -Treatment needs (Patients visited ED primarily to receive a bronchodilator by nebulizer and oxygen). - Inadequate use of ICS |

|

(Al-Jahdali et al, 2013) |

42.3 ±16.7 years | M= 176 (39.1%), F= 274 (60.9). |

NA | The study mentions that roper use of ICS therapy is essential for effective asthma control and reducing the likelihood of uncontrolled asthma and frequent ED visits. | NA | - MDI 361(80.2) - Turbuhaler 43(9.6) - Diskus 38(8.4) - MDI with spacer 3(0.7) |

NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

(Al-Jahdali et al. 2019) |

-48.7 years (±15.9) -18 to 35 = 222(22) -35 to 55 = 425(42.1) -55 to 70 = 260 (25.8) -70 and above = 102 (10.1) |

M= 350 (34.7) F= 659 (65.3) |

NA | -Inhaled corticosteroids: 197 (19.6) - Patients using fixed combination (inhaled corticosteroids + long-acting beta-agonist) and those using antileukotrienes were more likely to have controlled asthma compared to patients not taking such medications (OR: 1.77 [95% CI: 1.29–2.44] and OR: 2.39 [95% CI: 1.82–3.14], respectively). |

NA | Inhaled corticosteroids: 197 (19.6). Long-acting bronchodilator: 90 (9.0) Oral corticosteroids: 76 (7.6) Fixed combination (inhaled corticosteroids + long-acting beta-agonist): 833 (82.9) Antileukotrienes: 367 (36.5) Theophylline 55 (5.5) Anticholinergic bronchodilator: 96 (9.6) Short-acting beta-agonist: 546 (54.3) Nasal corticosteroids 41 (4.1) Antihistamine 12 (1.2) |

Patients with controlled asthma had better QoL according to SF-8 questionnaire (P < 0.001), but they did not show better medication adherence (according to MMAS-4© score). | Nonsmokers did not show any signiicant difference in asthma control levels when compared to active smokers and past smokers (P = 0.824). | Patients with higher educational level were almost four times more likely to have controlled asthma (OR: 3.72 [95% CI: 1.74–7.92]) | Patients without medical insurance coverage were more likely to have controlled asthma (OR: 1.44 [95% CI: 1.09–1.90]). |

| (Alomary et al., 2022) |

-The mean participant age was 38.6 years. |

56.9% were men. |

NA | NA | Wheeze 882 (14.2%) |

NA | NA | Using tobacco daily was associated with wheezing (aOR 2.7; 95% CI: 2.0–3.5) |

NA | -Significant factors associated with wheeze were: - jobs (aOR 11.8; 95% CI: 7.3–18.9) - Exposure to moisture or damp spots (aOR 2.2; 95% CI: 1.5– 3.4) -Heating the house when it is cold (aOR 1.7; 95% CI: 1.3–2.1) |

| (Alqahtani, J.M., 2020) | 19 to 23 (21.5 ±1.5) years | M= 116 students F= 106 students were included | NA | NA |

“Asthma” Participants without atopy (N= 122) -Wheeze “ever” 25 (20.4) -Current wheeze 13 (10.7) -Physician-diagnosed BA 26 (21.3) -Exercise-induced asthma 28 (25) -Nocturnal cough 42 (38.2) Participants with atopy (N= 90) -Wheeze “ever” 40 (44.4) -Current wheeze 32 (35.6) -Physician-diagnosed BA 34 (37.8) -Exercise-induced asthma 22 (24.4) -Nocturnal cough 28 (31.1) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| (Al-Zahrani JM et al. 2015) |

Adults (≥18 years of age) |

The sample included 120 males (30%) and 280 females (70%) |

Uncontrolled asthma was defined as an ACT score ≤16. findings show that 39.8% of patients had uncontrolled asthma. | NK | NK | A majority of patients used bronchodilators as their main inhaler, and 72.2% used it only for asthma therapy. Findings revealed that 55.2% were using the meter-dosed inhaler as their main devic | NK | Active smoking (P − value = 0.007), passive smoking (P − value = 0.019 | Approximately half of the patients had received a high school education or less, 38.9% had no education, and only 12% had university education. Unemployment was significantly associated with uncontrolled asthma (P − value = 0.019). | Improper device use by the patient was more frequently associated with uncontrolled asthma (46.9% partially/fully controlled vs. 64.2% uncontrolled asthma, P − value = 0.001) |

| (Alzahrani et al, 2024) |

Adults (≥18 years of age) |

The sample included 36 males (23.8%) and 115 females (76.2%) |

NK | NK | -Environment-related symptoms. -Emotion-related symptoms. |

NK | The present findings indicate the considerable influence of asthma on Quality of Life | Most of the participants did not smoke (91.4% | NK | Among the participants, 78 individuals (51.7%) had chronic diseases in addition to asthm |

| (Alzayer et al., 2022) | Adults (≥18 years of age) | The sample included 4 males (17%) and 19 females (82%) |

Participants’ asthma control scores indicated that 52% (n = 12) of par- ticipants or those with asthma they cared for had only partially controlled asthma (ACTTM score < 19), while 13% (n = 4) had poorly controlled asthma (ACTTM score < 15). | NK | NK | NK | NK | NK | There was a 3.1-fold increase in the odds of having uncontrolled asthma for patients with less than graduate degree (odds ratio [OR]=3.1; 95% CI=1.0-9.5) and for patients who were unemployed, disabled, or too ill to work (OR=3.1; 95% CI=1.4-6.9). Education level and occupation type are often reported to be associated with asthma control. | Findings clearly highlighted lack of knowledge about the role of different types of asthma medications. Most participants were rather unclear, for example, about the differences between reliever and preventer medications. |

| (BinSaeed, 2015) | Adults (≥18 years of age) |

The sample included 130 males (50.0%) and 126 females (48.8%) |

The proportion of patients with uncontrolled asthma in our study population was 68.1% | NK | The presence of heartburn symptoms during the past 4 weeks was associated with a 2.5 times greater odds of having uncontrolled asthma (OR=2.5; 95% CI=1.3-4.9) | NK | NK | It shoe that tobacco smoker who smoke daily have uncontrolled asthma 17/20(850.%). On the other hand, tobacco smoker who smoke less than daily or not at all have uncontrolled asthma 156/232(67.2%) | There was a 3.1-fold increase in the odds of having uncontrolled asthma for patients with less than graduate degree (odds ratio [OR]=3.1; 95% CI=1.0-9.5) and for patients who were unemployed, disabled, or too ill to work (OR=3.1; 95% CI=1.4-6.9). Education level and occupation type are often reported to be associated with asthma control. | The results of a bivariate analysis revealed that age, gender, marital status, education, and occupation, monthly household income, obesity, chronic sinusitis or allergic rhinitis, and having heartburn during the past 4 weeks, were associated with having uncontrolled asthma |

| (GhalebDailah, 2021) | Adults (≥18 years of age) |

The sample included males (46 %) and females (54%) |

Majority of control group have somewhat controlled asthma 24(38.1%). | NK | Often control group have asthma symptoms (wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness or pain) once or twice a week 17(27%) | Often control group have rescue inhaler or nebulizer (such as albuterol) 2 or 3 times per week 20(31.7%) | NK | NK | NK | NK |

| (Habib et al., 2014) | 36.1± 14.3 years | Male 42 Female 11 |

ACT score of <20 is correlated with uncontrolled asthma. In this study, 24 cases had an ACT score >20 And 29 cases had an ACT <20 |

28.3% used steroids 11.3% used a mix of medications |

N/A | 15.1% did not take any medications 39.6% used bronchodilators 28.3% used steroids 5.7% used leukotriene inhibitors 11.3% used a mix of medications |

The impact of asthma on quality of life was not explored in this paper | Smokers were excluded from the study as smoking is known to reduce FENO values | There was no significant correlation of FENO with age, height, weight, asthma duration, and ventilatory function tests. Educational level was not mentioned. | The conventional measures of asthma severity do not assess airway inflammation and may not provide optimal assessment for guiding therapy that will help in asthma control. |

| (Tarrafa H et al. 2018) | 18 years or more | Female 57% Male 43% |

Controlled or partly controlled 4202 Uncontrolled 2977 |

5.8% of the total population used only ICS as main asthma treatment | -frequent nighttime symptoms 10% of the population -exacerbation affecting activities and sleep 22.6% |

-38% used fixed ICS+ LABA with other treatment -27% used fixed ICS+LABA alone -8.1% used free ICS + LABA -5.8% used only ICS -4.5% used SABA alone -16.6% used other treatments |

-frequent night symptoms were reported in 10.3% of patients –66.3% of the population had a history of mild exacerbations -22.3% of patients reported an impact on daily activities and sleep |

-80.1% of the total population were non-smoker -9.1% were past smokers -10.8% active smokers |

Patients with a higher level of education were more likely to have controlled asthma (OR, 2.31 (95% CI 1.72, 3.09) | Poor asthma control can be addressed by improving access to appropriate treatments, encouraging better medication adherence and smoking avoidance, along with more proactive follow-up and better education among both healthcare providers and patients |

| (Tayeb et al., 2017) | Mean age: 44±16 years | Female 70 Men103 |

63% had uncontrolled asthma 34% were partially controlled 3% had controlled asthma |

N/A |

The cardinal asthma symptoms are shortness of breath, wheeze, cough, chest tightness | Asthma medications were not mentioned | -continuous morbidity -poor productivity -frequent absence from work -frequent visits to outpatient clinics and emergency rooms -financial burden on asthmatics and health systems |

N/A | The study reflects the unacceptably low awareness of health professionals about the harmful effects of asthma-triggering drugs on asthma control levels. Regular asthma educational courses for health professionals are important. | Asthma-triggering drug use is a substantial cause of poor asthma control. This reflects the low awareness of health professionals about the negative effects of these drugs on asthma control |

| (Torchyan et al., 2017) | Adults aged 18 years and above | Male 129 Female 128 |

-67.8% of the total population had uncontrolled asthma - 32.2 % had controlled asthma |

The use of ICS was not discussed in this paper | Symptoms in the studied population were not discussed clearly in this paper | Asthma medications were not mentioned | -4.1 mean (1.4 SD) suffered from symptoms -4.4 (1.5) had activity limitations -4.3 (1.6) emotional function -3.9 (1.5) environmental stimuli |

Tobacco smoking was associated with 0.72-point decrease (95% CI=A –1.30 - - 0.14) in the AQL among males. The decreased quality of life might be attributed to increased inflammation in the airways and reduced sensitivity to corticosteroids caused by cigarette smoking | Effect of level of education on asthma control was not explored in this paper | This paper reveals gender-specific differences in the correlates of AQL in Saudi Arabia |

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

References

- Mims JW. Asthma: definitions and pathophysiology. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol [Internet]. 2015;5(S1). [CrossRef]

- Gans MD, Gavrilova T. Understanding the immunology of asthma: Pathophysiology, biomarkers, and treatments for asthma endotypes. Paediatr Respir Rev [Internet]. 2020;36:118–27. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1526054219300818.

- Maslan J, Mims JW. What is asthma? Pathophysiology, demographics, and health care costs. Otolaryngol Clin North Am [Internet]. 2014;47(1):13–22. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0030666513001540.

- Al Ghobain MO, Algazlan SS, Oreibi TM. Asthma prevalence among adults in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 2018;39(2):179–84. [CrossRef]

- Moradi-Lakeh M, El Bcheraoui C, Daoud F, Tuffaha M, Kravitz H, Al Saeedi M, et al. Prevalence of asthma in Saudi adults: Findings from a National Household Survey, 2013. BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 2015;15(1). [CrossRef]

- BinSaeed AA. Asthma control among adults in Saudi Arabia: Study of determinants. Saudi Med J [Internet]. 2015 Al-Zalabani, A.H. and Almotairy, M.M. (2020) Asthma control and its association with knowledge of caregivers among children with asthma, Saudi Medical Journal. [CrossRef]

- Al-Zalabani AH, Almotairy MM. Asthma control and its association with knowledge of caregivers among children with asthma: A cross-sectional study. Saudi Med J [Internet]. 2020.

- AL-Jahdali H, Wali S, Salem G, Al-Hameed F, Almotair A, Zeitouni M, et al. Asthma control and predictive factors among adults in Saudi Arabia: Results from the Epidemiological Study on the Management of Asthma in Asthmatic Middle East Adult Population study. Ann Thorac Med 2019;14:148-54. [CrossRef]

- Emotional effects of asthma [Internet]. Uillinois.edu.

- Meal planning and eating [Internet]. Mylungsmylife.org.

- Kharaba Z, Feghali E, El Husseini F, Sacre H, Abou Selwan C, Saadeh S, et al. An assessment of quality of life in patients with asthma through physical, emotional, social, and occupational aspects. A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022;10. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed AE, AL-Jahdali H, AL-Harbi A, et al. Factors associated with poor asthma control among asthmatic patient visiting emergency department. The Clinical Respiratory Journal 2014; 8: 431-436. [CrossRef]

- Alanazi TM, Alghamdi HS, Alberreet MS, et al. The prevalence of sleep disturbance among asthmatic patients in a tertiary care center. Scientific Reports 2021; 11: 2457. [CrossRef]

- Al-Jahdali HH, Al-Hajjaj MS, Alanezi MO, et al. Asthma control assessment using asthma control test among patients attending 5 tertiary care hospitals in Saudi Arabia. Saudi medical journal 2008; 29: 714.

- Al-Jahdali H, Anwar A, Al-Harbi A, et al. Factors associated with patient visits to the emergency department for asthma therapy. BMC pulmonary Medicine 2012; 12: 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Tayeb MMS, Aldini MAM, Laskar AKA, et al. Prevalence of asthma-triggering drug use in adults and its impact on asthma control: A cross-sectional study–Saudi (Jeddah). Australasian Medical Journal (Online) 2017; 10: 1003-1007.

- Al-Jahdali H, Ahmed A, Al-Harbi A, et al. Improper inhaler technique is associated with poor asthma control and frequent emergency department visits. Allergy, asthma & clinical immunology 2013; 9: 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Hamdan A-J, Wali S, Salem G, et al. Asthma control and predictive factors among adults in Saudi Arabia: Results from the Epidemiological Study on the Management of Asthma in Asthmatic Middle East Adult Population study. Annals of thoracic medicine 2019; 14: 148-154. [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani JM, Ahmad A, Abdullah A-H, et al. Factors associated with poor asthma control in the outpatient clinic setting. Annals of thoracic medicine 2015; 10: 100-104. [CrossRef]

- Alzayer R, Almansour HA, Basheti I, et al. Asthma patients in Saudi Arabia–preferences, health beliefs and experiences that shape asthma management. Ethnicity & Health 2022; 27: 877-893. [CrossRef]

- Torchyan AA, BinSaeed AA, Khashogji SdA, et al. Asthma quality of life in Saudi Arabia: Gender differences. Journal of Asthma 2017; 54: 202-209. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi BR, Koshak EA, Omer FM, et al. Immunological factors associated with adult asthma in the Aseer Region, Southwestern Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019; 16: 2495.

- Alomary SA, Al Madani AJ, Althagafi WA, et al. Prevalence of asthma symptoms and associated risk factors among adults in Saudi Arabia: A national survey from Global Asthma Network Phase Ⅰ. World Allergy Organization Journal 2022; 15: 100623. [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani SJM, Alzahrani HAK, Alghamdi SMM, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life of Asthmatic Patients in Al-Baha City, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024; 16. [CrossRef]

- Habib SS, Alzoghaibi MA, Abba AA, et al. Relationship of the Arabic version of the asthma control test with ventilatory function tests and levels of exhaled nitric oxide in adult asthmatics. Saudi Med J 2014; 35: 397-402.

- Tarraf H, Al-Jahdali H, Al Qaseer AH, et al. Asthma control in adults in the Middle East and North Africa: Results from the ESMAA study. Respiratory medicine 2018; 138: 64-73. [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb Dailah H. Investigating the outcomes of an asthma educational program and useful influence in public policy. Frontiers in Public Health 2021; 9: 736203.

- Aleid A, Alolayani RA, Alkharouby R, Gawez ARA, Alshehri FD, Alrasan RA, et al. Environmental Exposure and Pediatric Asthma Prevalence in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus [Internet]. 2023 Oct 9 [cited 2025 Mar 22];15. Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/190049-environmental-exposure-and-pediatric-asthma-prevalence-in-saudi-arabia-a-cross-sectional-study.

- Almqvist C, Worm M, Leynaert B, WP 2.5 ‘Gender’ for the working group of G. Impact of gender on asthma in childhood and adolescence: a GA2LEN review. Allergy [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2025 Mar 22];63(1):47–57. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01524.x.

- Backman H, Jansson SA, Stridsman C, Eriksson B, Hedman L, Eklund BM, et al. Severe asthma—A population study perspective. Clinical & Experimental Allergy [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Apr 9];49(6):819–28. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/cea.13378.

- Chen M, Wu Y, Yuan S, Chen J, Li L, Wu J, et al. Research on the improvement of allergic rhinitis in asthmatic children after reducing dust mite exposure: a randomized, double-blind, cross-placebo study protocol [Internet]. Research Square; 2020 [cited 2025 Mar 22]. Available from: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-15256/v1.

- Cilluffo G, Ferrante G, Fasola S, Malizia V, Montalbano L, Ranzi A, et al. Association between Asthma Control and Exposure to Greenness and Other Outdoor and Indoor Environmental Factors: A Longitudinal Study on a Cohort of Asthmatic Children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Jan [cited 2025 Mar 22];19(1):512. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/1/512.

- Domingo C, Sicras-Mainar A, Sicras-Navarro A, Sogo A, Mirapeix R, Engroba C. Prevalence, T2 Biomarkers, and Cost of Severe Asthma in the Era of Biologics: The BRAVO-1 Study. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol [Internet]. 2024 Apr 12 [cited 2025 Mar 18];34(2):97–105. Available from: https://www.jiaci.org/summary/vol34-issue2-num2861.

- Engelkes M, Janssens HM, Jongste JC de, Sturkenboom MCJM, Verhamme KMC. Medication adherence and the risk of severe asthma exacerbations: a systematic review. European Respiratory Journal [Internet]. 2015 Jan 31 [cited 2025 Mar 20];45(2):396–407. Available from: https://publications.ersnet.org/content/erj/45/2/396.

- Heinrichs K, Hummel S, Gholami J, Schultz K, Li J, Sheikh A, et al. Psychosocial working conditions, asthma self-management at work and asthma morbidity: a cross-sectional study. Clinical and Translational Allergy [Internet]. 2019 May 9 [cited 2025 Mar 20];9(1):25. [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola MS, Hyrkäs-Palmu H, Jaakkola JJK. Residential Exposure to Dampness Is Related to Reduced Level of Asthma Control among Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Jan [cited 2025 Mar 22];19(18):11338. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/18/11338.

- Khan JR, Lingam R, Owens L, Chen K, Shanthikumar S, Oo S, et al. Social deprivation and spatial clustering of childhood asthma in Australia. Global Health Research and Policy [Internet]. 2024 Jun 24 [cited 2025 Mar 22];9(1):22. [CrossRef]

- Kosse RC, Bouvy ML, Vries TW de, Koster ES. Effect of a mHealth intervention on adherence in adolescents with asthma: A randomized controlled trial. Respiratory Medicine [Internet]. 2019 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Mar 20];149:45–51. Available from: https://www.resmedjournal.com/article/S0954-6111(19)30045-9/fulltext.

- Lin J, Gao J, Lai K, Zhou X, He B, Zhou J, et al. The characteristic of asthma control among nasal diseases population: Results from a cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2018 Feb 22 [cited 2025 Mar 18];13(2):e0191543. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0191543.

- Mishra R, Kashif M, Venkatram S, George T, Luo K, Diaz-Fuentes G. Role of Adult Asthma Education in Improving Asthma Control and Reducing Emergency Room Utilization and Hospital Admissions in an Inner City Hospital. Canadian Respiratory Journal [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Mar 18];2017(1):5681962. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1155/2017/5681962.

- Mohamed Hussain S, Ayesha Farhana S, Mohammed Alnasser S. Time Trends and Regional Variation in Prevalence of Asthma and Associated Factors in Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BioMed Research International [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Mar 22];2018(1):8102527. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1155/2018/8102527.

- Mroczek B, Kurpas D, Urban M, Sitko Z, Grodzki T. The Influence of Asthma Exacerbations on Health-Related Quality of Life. In: Pokorski M, editor. Ventilatory Disorders [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015 [cited 2025 Mar 22]. p. 65–77. (Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; vol. 873). Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/5584_2015_157.

- Murray CS, Foden P, Sumner H, Shepley E, Custovic A, Simpson A. Preventing Severe Asthma Exacerbations in Children. A Randomized Trial of Mite-Impermeable Bedcovers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med [Internet]. 2017 Jul 15 [cited 2025 Mar 22];196(2):150–8. Available from: https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.201609-1966OC.

- Nguyen VN, Huynh TTH, Chavannes NH. Knowledge on self-management and levels of asthma control among adult patients in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. IJGM [Internet]. 2018 Feb 26 [cited 2025 Mar 18];11:81–9. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/knowledge-on-self-management-and-levels-of-asthma-control-among-adult--peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-IJGM.

- Onubogu UC, Owate E. Pattern of Acute Asthma Seen in Children Emergency Department of the River State University Teaching Hospital Portharcourt Nigeria. Open Journal of Respiratory Diseases [Internet]. 2019 Oct 14 [cited 2025 Mar 22];9(4):101–11. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=95685.

- Shahid S, Jaan G, Nadeem A, Nadeem J, Fatima K, Sajjad A, et al. Effect of educational intervention on quality of life of asthma patients: A systematic review. Med Sci [Internet]. 2024 Mar 31 [cited 2025 Mar 20];28(145):1–17. Available from: https://discoveryjournals.org/medicalscience/current_issue/v28/n145/e9ms3300.htm.

- Tiotiu A, Ioan I, Wirth N, Romero-Fernandez R, González-Barcala FJ. The Impact of Tobacco Smoking on Adult Asthma Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Jan [cited 2025 Mar 22];18(3):992. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/3/992.

- Tiwari R, Timilsina M, Banstola S. Impact of Pharmacist-led Interventions on Medication Adherence and Inhalation Technique in Adult Patients with COPD and Asthma. Journal of Health and Allied Sciences [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 20];13(1):14–22. Available from: https://jhas.org.np/jhas/index.php/jhas/article/view/473.

- Williams LK, Peterson EL, Wells K, Ahmedani BK, Kumar R, Burchard EG, et al. Quantifying the proportion of severe asthma exacerbations attributable to inhaled corticosteroid nonadherence. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology [Internet]. 2011 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Mar 20];128(6):1185-1191.e2. Available from: https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(11)01481-3/fulltext.

- Yalçınkaya G, Kılıç M. Asthma Control Level and Relating Socio-Demographic Factors in Hospital Admissions. International Journal of Statistics in Medical Research [Internet]. 2022 Apr 7 [cited 2025 Mar 22];11:19–26. Available from: https://lifescienceglobal.com/pms/index.php/ijsmr/article/view/8649.

- Zhang X, Lai Z, Qiu R, Guo E, Li J, Zhang Q, et al. Positive change in asthma control using therapeutic patient education in severe uncontrolled asthma: a one-year prospective study. Asthma Research and Practice [Internet]. 2021 Jul 21 [cited 2025 Mar 20];7(1):10. [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani JM. Atopy and allergic diseases among Saudi young adults: A cross-sectional study. J Int Med Res [Internet]. 2020;48(1):300060519899760. [CrossRef]

| MAuthor (year) | Design | Location | Sample Size | Main and Secondary Outcomes |

Asthma Diagnosis | Estimated Asthma Prevalence? | Prevalence of Asthma control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ahmed AE, 2014) | Cross-sectional study | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | 450 participants |

Main outcomes: • Factors statistically significant for poor asthma were age and three or more ED visits. Asthma control is predicted to decrease 0.753 for participant who had multiple ED visits. Age does affect asthma control; each 1-year increase in age consequently decreases the asthma control by 0.021. The asthma control is predicted to increase 1.427 when participant educated about asthma medication. The asthma control scores increased by 0.799 when participants were educated about asthma disease. • Average asthma control for participants with three or more ED visits was lower than those with less than three ED visits (16.6 ± 3.9 vs 18.0 ± 3.6, P value = 0.001). • There was a significant difference in the asthma control scores for severe persistent asthma (M = 8.5, SD = 2.0), mild persistent (M = 18.0, SD = 2.3) and intermittent asthma (M = 19.3, SD = 3.1), P value = 0.001. These findings suggest that severity of asthma as measured by asthma severity classification really does influence asthma control scores. Secondary outcomes: • Participants with poor asthma control have poor health-related quality of life, more doctor and hospital visits. • Participants with severe persistent asthma had very low asthma control with an average of 8.5, which is considered poor asthma control. The severe persistent asthma group has not only a poor quality of life, but also increased mortality and health-care resource utilisation |

Clinically diagnosed | -NR |

average asthma control score for the study sample was 17.5 with a standard deviation of ±3.8 and Scores between 16 and 19 inclusive are considered ‘not well controlled’ |

| (Al-Ghamdi et al., 2019) |

Cross-sectional study |

Aseer Region, Southwestern Saudi Arabia |

960 participants |

Main Outcomes: • 184 adults reported having wheeze on the past 12 months when not having a cold giving a prevalence rate of BA of 19.2% (95% CI: 16.72–21.80) • prevalence of BA among males amounted to 18.3% (95% CI: 15.57–21.39) and among females amounted to 21.5% (95% CI: 16.57–27.21). The presence of an overlap in the 95% CI in males and females, showed a nonsignificant statistical difference by gender ——————————— Secondary Outcomes: some factors were found to be significantly associated with BA • Adults living at low-altitude areas had more risk developing BA compared to those living at high-altitude areas (aOR = 1.51, 95% CI: 1.04–2.21) • Living in rural areas (aOR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.12–2.23) • Using analgesics (aOR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.06–2.20) • Living near heavy trucks traffic streets (aOR = 1.67, 95% CI: 1.13–2.46) • Having cats in the house (aOR = 2.27, 95% CI: 1.30–5.94) • Adults aged 55 64-year-old (aOR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.02–3.69) |

Clinically diagnosed | NA |

NA |

| (AL-Jahdali et al, 2008) | Cross-sectional study | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | 1,060 participants |

Main Outcomes: • There are no significant correlations between age below 40 and above 40 years, and level of asthma control (p=0.12). • Age: The younger age group (less than 20 years old) had better asthma control compared to the older age • Gender: 44% of males have controlled asthma, while only 30% of females have controlled asthma, (p=0.0001) • Education: 71% of patients who did not have formal education had uncontrolled asthma (p=0.001) ———————————— Secondary Outcomes: No secondary outcomes |

Clinically diagnosed | prevalence of asthma is 4% in Saudi Arabia. |

ACT score revealed uncontrolled asthma in 667 (64%), well-controlled asthma in 383 (31%), and completely controlled in 55(5%). |

| (AL-Jahdali et al, 2012) | Cross-sectional | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | 450 participants |

Main Outcomes: • Asthma was not controlled or partially controlled in the majority (97.7%) of the patients • Education about asthma and uncontrolled asthma are the major factors leading to frequent ED visits (three or more visits/year), p-value = 0.0145 and p-value = 0.0003, respectively preceding the admission to ED —————————————— Secondary Outcomes: Distribution of uncontrolled asthma varied depending on: • Patient ICS use: (27.6% irregular, while 19.4% regular use). • Education: those who had not been educated about asthma were more likely to have uncontrolled asthma than those who had been educated about asthma (28.1% versus 18.1%) |

Physician diagnosis |

20-25% among Saudi patients | Uncontrolled= 23.4% (ACT score ≤ 15) Partially controlled= 74.4% (16 ≤ ACT score ≤ 23) Complete cotrolled asthma= 1.8% (ACT score ≥ 24). |

|

(Al-Jahdali et al, 2013) |

Cross-sectional study |

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia |

450 patients |

Main Outcome: • The study found that asthma control, as measured by the Asthma Control Test (ACT), had the strongest association with improper inhaler use. • The improper use of asthma inhaler devices was observed in 203(45%) • Among patients with uncontrolled asthma (ACT score ≤15), 59.1% were using their asthma inhaler devices improperly. ——————————————— Secondary Outcomes: • Patients with irregular clinic follow-up had a 60.9% rate of improper inhaler use. • Those who received no education about asthma as a disease had a 57.4% rate of improper use. • Patients without education about asthma medication or inhaler devices had a 54.6% rate of improper use. • Patients with three or more ED visits per year had a 50.9% rate of improper use. • Those diagnosed with asthma for less than one year had a 77.8% rate of improper inhaler use. |

Physician diagnosis | 20-25% among Saudi patients | -Uncontrolled asthma (ACT ≤15): 23.3% (105 patients) -Partially controlled asthma (ACT 16–23): 74.4% (335 patients) -Fully controlled asthma (ACT ≥24): 1.8% (8 patients) -Missing ACT data: 0.5% (2 patients) |

| (Al-Jahdali et al. 2019) |

Cross-sectional | Saudi Arabia | 1009 patients |

Main Outcome: - Asthma control (GINA classification, n = 993): • Controlled: 30.1% • Partly controlled: 31.9% • Uncontrolled: 38.0% - Asthma control significantly associated with: • Higher education (OR: 3.72 [95% CI: 1.74–7.92]). • Use of ICS+LABA (OR: 1.77 [95% CI: 1.29–2.44] • Female patients were less likely to have controlled asthma (OR: 0.71 [95% CI: 0.54–0.93]). ——————————————— Secondary Outcomes: -Quality of life scores (SF-8): • Significantly higher in the 30.1% with controlled asthma (P < 0.001) -Good treatment adherence (MMAS-4): • Controlled: 27.4% • Partly controlled:21.1% • Uncontrolled: 21.5% • No significant difference (P = 0.112) -No significant association between asthma control and: • Age groups (P = 0.550) • BMI categories (P = 0.107) • Smoking status (P = 0.824) |

Physician diagnosis | From 4% to 25% | -Controlled: (30.1) (95% CI: 27.3%–33.0%) -Partly controlled: 31.9% (95% CI: 29.1%–34.9%) -Uncontrolled asthma: 38.0% (95% CI: 35.0%–41.0%) |

| (Alomary et al., 2022) | Cross-sectional study | Saudi Arabia | 7955 participates |

Main Outcome: • Prevalence of current wheeze: 14.2% overall • Higher in women (14.9%) than men (13.7%) • Among those with current wheeze, 38.1% had severe asthma symptoms —————————————- Secondary Outcomes: • Ever diagnosed with asthma: 14.0% (women: 14.5%, men: 13.6%) • 83.3% had doctor-confirmed diagnosis • Only 38.4% had a written asthma control plan • 50.5% had an asthma attack in past 12 months -Women had significantly higher rates of: • Asthma control plan: 44.8% vs. 33.3% (P = .001) • Asthma attacks: 56.0% vs. 46.2% (P = .005) ——————————————— • Sleep disturbance due to wheeze: 62.8% • Breathlessness with wheeze: 59.4% • Limited speech due to wheeze: 21.6% • Highest wheeze prevalence in 20–29 age group: 19.2% |

(83.3%) diagnosed by doctors | - In 2013, 4,05% of the population. -A meta-analysis of 92 studies conducted between 1996 and 2016 in the Eastern Mediterranean Region found that Saudi Arabia exhibited one of the highest asthma prevalence rates at 17.6%. |

NA |

| (Alqahtani, J.M., 2020) | cross-sectional study | Najran, southwestern Saudi Arabia | 222 participants |

Main Outcome: 1. Prevalence of physician-diagnosed allergic diseases among Saudi young adults: • Asthma: 27% (significantly higher in males, p = 0.01) • Atopic Dermatitis (AD): 13.1% • Allergic Rhinitis (AR): 5% ———————————————Secondary Outcomes: • Atopy prevalence: 40.5% 1.Among atopic students: • 54.4% had symptoms • BA: 27.8%, BA + AD: 5.6%, BA + AR: 3.3%, BA + AD + AR: 1.1% 2. Gender differences: • Males reported more wheezing, cough, and rhinitis symptoms (various p-values < 0.05) • Males more sensitized to cat hair & ragweed; females to dog hair & Bermuda grass • Common allergen sensitivities (SPT): Bermuda grass (20.8%), cat fur (18.9%), D. pteronyssinus (12.7%) |

Physician diagnosis | -From 4.1% to 23% for BA. -From 5.3% to 25% for AR. -From 6.1% to 13% for AD. |

NA |

| (Al-Zahrani JM et al. 2015) | cross-sectional study | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | 400 participants |

Mean outcomes: 1. Prevalence of uncontrolled asthma: 39.8% 2. Inappropriate inhaler device use: 53.8% 3. Patient Demographics: • Age: 45.6 ± 16.2 years • BMI: 31.5 ± 7.5 kg/m² • Duration of asthma: 9.5 ± 4.0 years 4. ACT score: • Partially/fully controlled: Not reported • Uncontrolled: ≤ 16 ——————————————— Secondary outcomes: 1. Factors associated with uncontrolled asthma: • Active smoking (P-value = 0.007) • Passive smoking (P-value = 0.019) • Improper use of inhaler devices (P-value = 0.001) • Unsealed mattress (P-value = 0.030) • Workplace triggers (P-value = 0.036) • Female gender (P-value = 0.002) • Unemployment (P-value = 0.019) • Single or divorced/widowed patients (P-value = 0.028) 2. Patient knowledge about environmental triggers: • 44% aware that active smoking can trigger asthma • 6.5% aware that passive smoking can trigger asthma • 12.2% aware that bedroom carpets can trigger asthma • 12% aware that unsealed mattress can increase the risk of asthma • 28.8% aware about the workplace asthma triggers 3. Patient knowledge about asthma and its management: • 84.8% received education about asthma from a physician • 21.2% received education from an asthma educator • 10.8% received education from a pharmacist • 20.2% learned about asthma through self-teaching 4. Effects of education sources on asthma knowledge: • Physician education (P-value = 0.00) • Asthma educator education (P-value = 0.001) • Self-teaching (P-value = 0.013) 5. Medication management: • 79.5% of patients stop inhaled corticosteroids when asthma improves. • 62.2% of patients increase or start steroid therapy when having an attack. • 92.0% of patients increase or start bronchodilator therapy when having an attack. 6. Patient practices: • 37.2% of patients believe asthma therapy is unsafe for long-term use. • 34.5% of patients believe asthma therapy is addictive. |

Physician-diagnosed asthma | The study enrolled 400 asthma patients |

39.8% of patients had uncontrolled asthma |

| (Alzahrani et al, 2024) | cross-sectional study | Al-Baha, Saudi Arabia |

151 patients |

Mean outcomes: 1. Participants' Age: • Mean age: 52 years • Standard deviation: 15.4 years 2. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL): • Overall Mean Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (MiniAQLQ) score: 3.86 • Percentage of participants with low HRQoL: 74.2% • Percentage of participants with high HRQoL: 25.8% ——————————————— Secondary outcomes: 1. Environment-related symptoms: • 69% of participants reported feeling bothered by or having to avoid cigarette smoke "all the time" • 61% of participants reported feeling bothered by or having to avoid dust "all the time" 2. Emotion-related symptoms: • 54% of participants reported fear of not having asthma medication available • 46% of participants reported never feeling frustrated because of asthma • 43% of participants felt concerned about having asthma 3. Activity limitations: • 29% of participants reported no limits in social activities • 28% of participants reported complete limitation in social activities • 28% of participants reported no restrictions in work-related activities • 23% of participants reported complete limitation in work-related activities 4. Correlations: • Age: Weak correlation with MiniAQLQ scores • Gender: Weak correlation with MiniAQLQ scores • Altitude: Weak correlation with MiniAQLQ scores • Presence of chronic diseases: Weak correlation with MiniAQLQ scores • Smoking: Weak correlation with MiniAQLQ scores |

Symptoms report | The study enrolled 151 asthma patients | -Prevalence of high HRQoL: 25.8% (39 out of 151 participants) - Prevalence of low HRQoL: 74.2% (112 out of 151 participants) |

| (Alzayer et al., 2022) | A qualitative research method | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | 20 participant |

Mean outcomes: 1. Participant demographics: • Female participants: 82% • Male participants: • Average age of participants: 32 years 2. Asthma Control: • Well-controlled asthma: 52% • Partially controlled asthma: 35% • Poorly controlled asthma: 13% 3. Educational background: • Participants with university education: 70% • Participants with school level education: 30% 4. Clinical scores: - Average ACT™ score for participants: 19 ——————————————— Secondary outcomes: 1. Themes identified: • Participants' Experience of Asthma: - Concerns about asthma complications and potentially fatal outcomes - Embarrassment and stigma associated with using asthma medications • Participants' Beliefs and Perceptions about Health and Medicines: - Lack of knowledge about asthma medications - Preference for herbal medicines over western medications - Concerns about medication side effects and fear of consequences • Perception of Health Professionals: - Reliance on doctors over pharmacists for asthma care - Paternalistic relationship with healthcare providers • Advocacy and Social Support: - Use of social media for health information - Family involvement in treatment decisions 2. Subthemes identified: • Asthma Literacy: - Lack of medication knowledge - Uncertainty about first aid • Health Behaviors: - Reactive care tendencies - Reluctance in emergencies • Beliefs in Alternative Medicine: - Herbal remedy preference - Safety concerns about medications • Pharmacists' Roles: - Limited awareness of pharmacist potential - Perception of pharmacists as medicine sellers • Doctor-Patient Relationship: - Implicit trust in physicians - Reluctance to seek help elsewhere |

Interviews | The study enrolled 20 asthma patients | The median ACTTM score for adult patients was lower compared to median ACT TM scores reported by carers (Participants who were carers and reported the score for a child with asthma) although both groups had a medianscore below 19 points which indicate that asthma may not well controlled. |

| (BinSaeed, 2015) | Cross-sectional survey | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | 260 patients (251 Saudi patients) |

Mean outcomes: • Average age of participants: 32 years • 68.1% of patients had uncontrolled asthma • 31.9% of patients had controlled asthma • Average asthma diagnosis duration: 10.5 years • 66.2% of patients had allergic rhinitis • 38.8% of patients had chronic sinusitis • 19.6% of patients had hypertension • 8.5% of patients were daily tobacco smokers • 22.2% of patients had monthly household income < SAR 15,000 ——————————————— Secondary outcomes: 1.Factors Associated with Uncontrolled Asthma: - Tobacco smoking, lower income, and certain comorbidities were associated with uncontrolled asthma. 2. Socio-Demographic Factors: Education, occupation, and income level significantly influenced asthma control. 3. Clinical Factors: Chronic sinusitis and heartburn were linked to uncontrolled asthma. 4. Gender Disparity: Females had 2 times greater odds of uncontrolled asthma compared to males. 5. Age Influence: Patients ≥35 years had 2 times greater odds of uncontrolled asthma compared to younger patients. 6. Comorbidity Impact: Chronic sinusitis and heartburn increased the odds of uncontrolled asthma . 7. Smoking Habits: Daily tobacco smokers had higher odds of uncontrolled asthma. 8. Income Level: Patients with lower household income had higher odds of uncontrolled asthma. 9. Educational Attainment: Patients with less than a graduate degree had increased odds of uncontrolled asthma. 10. Occupational Status: Unemployed, disabled, or ill patients had higher odds of uncontrolled asthma. |

Patients had been diagnosed by a physician at least 3 months before joining the stud | The study enrolled 260 asthma patients | Uncontrolled asthma was present in 68.1% (177/260) of the patients. |

| (GhalebDailah, 2021) | Cross-sectional study | Saudi Arabia, Jeddah and Jazan | 263 participants |

Main outcome: • positive change was noticed in the intervention group of patients across the three stages compared to controlled group. • Patients in the intervention group performed very well In The Asthma Self-management Questionnaire, unlike the control group which achieved very low scores. • In Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire, the correct response in control group was the same, while variation was seen in the intervention group • In Patients Activation, the improvement of mean scores of the patients in the control groups lower as compared to the intervention group across different asthma programme stages. ——————————————— Secondary outcome: • The intervention group had clear and strong changes in patient asthma self-management • The intervention group in patients activation had very minor impact from the program |

Targeted patients across four hospitals in Jeddah and jazan, KSA. | The study enrolled 134 control group of asthma patients | It Showed that control group have somewhat controlled asthma 24(38.1%), completely controlled asthma 15(23.8%), poorly controlled asthma 7(11.1%). |

| (Habib et al., 2014) | Cross-sectional | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | 53 Participants | Main outcome: 1.Association between FeNO levels and asthma control (ACT score): • Higher FeNO in poorly controlled asthma (ACT <20): Mean FeNO = 65.5 ± 35.4 ppb • Lower FeNO in well-controlled asthma (ACT ≥20): Mean FeNO = 27.4 ± 10.5 ppb • Statistical significance: p < 0.001 • Negative correlation between FeNO and ACT score: r = -0.581, p < 0.0001 ———————————————Secondary outcomes: 1. ACT Score Distribution (N = 53): • ACT ≥20 (well-controlled): 24 cases (45.3%) • ACT <20 (poorly controlled): 29 cases (54.7%) 2.FeNO Levels by Asthma Control: • the well-controlled asthma group (ACT ≥20): ○ 18 cases (75%) had desirable FeNO levels. ○ 6 cases (25%) had high FeNO levels. • In the poorly controlled asthma group (ACT <20): • 6 cases (20.7%) had desirable FeNO levels. ○ 23 cases (79.3%) had high FeNO levels 3.Diagnostic Accuracy of ACT Score: • Best ACT cutoff = 19 ○ Area Under Curve (AUC) = 91% (95% CI: 83.5–98.5%) ○ Sensitivity = 90.5% (95% CI: 76.2–100%) ○ Specificity = 81.2% (95% CI: 65.6–93.7%) |

Clinically diagnosed | The study recruited 59 adult asthmatics out of which 53 completed the study | The prevalence of asthma control among the study group was 45.3% (24 cases) |

| (Tarrafa H et al. 2018) | Cross-sectional | 11 Middle Eastern and North African Countries including (Saudi Arabia) | 7236 patients Saudi Arabia (N=1009) | Main outcome: 1.Asthma control levels (GINA classification) among adult asthmatics in Saudi Arabia: • Controlled: 21.6% • Partly controlled: 33.4% • Uncontrolled: 45.0% 2.Poor adherence to medication (Morisky score = 4): • Only 22.9% of Saudi patients reported good adherence. ——————————————— Secondary outcome: 1.Exacerbations affecting daily life and sleep: 18.5% 2..Quality of Life Scores (SF-8): • Physical summary score: 43.0 • Mental summary score: 44.9 3.Treatment & Adherence: • Receiving treatment: 97.1% • Main treatment used: 62.7% used Fixed ICS + LABA + other treatments • 13.6% used Fixed ICS + LABA only |

Clinically diagnosed and patient assessment | 7179 patients (99.2% of the eligible population) | Asthma was controlled in 29.4% (95% CI, 28.4% to 30.5%) |

| (Tayeb et al., 2017) | Cross-Sectional | Jeddah, Saudi Arabia | 173 asthmatic adults | Main outcome: 1.Asthma control levels among adult asthmatics: • Uncontrolled asthma: 63% • Partially controlled asthma: 34% • Controlled asthma: 3% 2. Use of asthma-triggering drugs (ATDs): • 51% of patients were using ATDs: ○ 31% had uncontrolled asthma ○ 19% had partially controlled asthma ○ 2% had controlled asthma • 49% were not using ATDs ○ 32% had uncontrolled asthma ○ 15% had partially controlled asthma ○ 2% had controlled asthma ———————————————Secondary outcome: 1.Polypharmacy (use of multiple ATDs): • Uncontrolled asthmatics used an average of 4 ATDs (64% of ATD users) • Partially controlled asthmatics also used 4 ATDs on average (33% of ATD users) • Controlled asthmatics used 3 ATDs 2.Most commonly used ATDs (in order of prevalence): • Aspirin • ACE inhibitors • Other NSAIDs • β-blockers |

Clinically diagnosed | There is a high prevalence of adult asthmatics with bad control | Only a minority had controlled asthma 3% |

| (Torchyan et al., 2017) | Cross-sectional | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | 257 participants | Mean outcomes: - Asthma Quality of Life (AQL) Mean Score: - Men: 4.3 (SD = 1.5) - Women: 4.0 (SD = 1.3) ——————————————— Secondary outcomes: Factors Associated with AQL: • With each unit increase in asthma control, the AQL improved by 0.19 points (95% CI = 0.14-0.23) in men and by 0.21 points (95% CI = 0.16-0.25) in women. • Daily tobacco smoking was associated with a 0.72 point decrease in the AQL among males (95% CI = -1.30 – -0.14). • Women who had a household member who smoked inside the house had a significantly lower AQL (B = -0.59, 95% CI = -1.0 – -0.19). • A monthly household income of 25,000 Saudi Riyals or more was associated with a better AQL among men (B = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.01-1.01). • Being employed showed a protective effect on AQL in women (B = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.11-0.84). • Higher levels of perceived asthma severity were associated with better AQL in women (B = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.36-1.28). |

Clinically diagnosed based on medical history | 304 asthmatic participants were approached, and only 260 agreed to participate. | Asthma was controlled in 82 patients (32.2%) out of total n=257 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).