Submitted:

26 May 2025

Posted:

27 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Plant Material and Preparation of Extracts [52,53]

2.3. UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS System [53,54]

2.4. Data Preprocessing

2.5. Quality Evaluation, Quality Control, and Standardized Processing Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis of Metabolite Content

3. Results

3.1. Method Validation

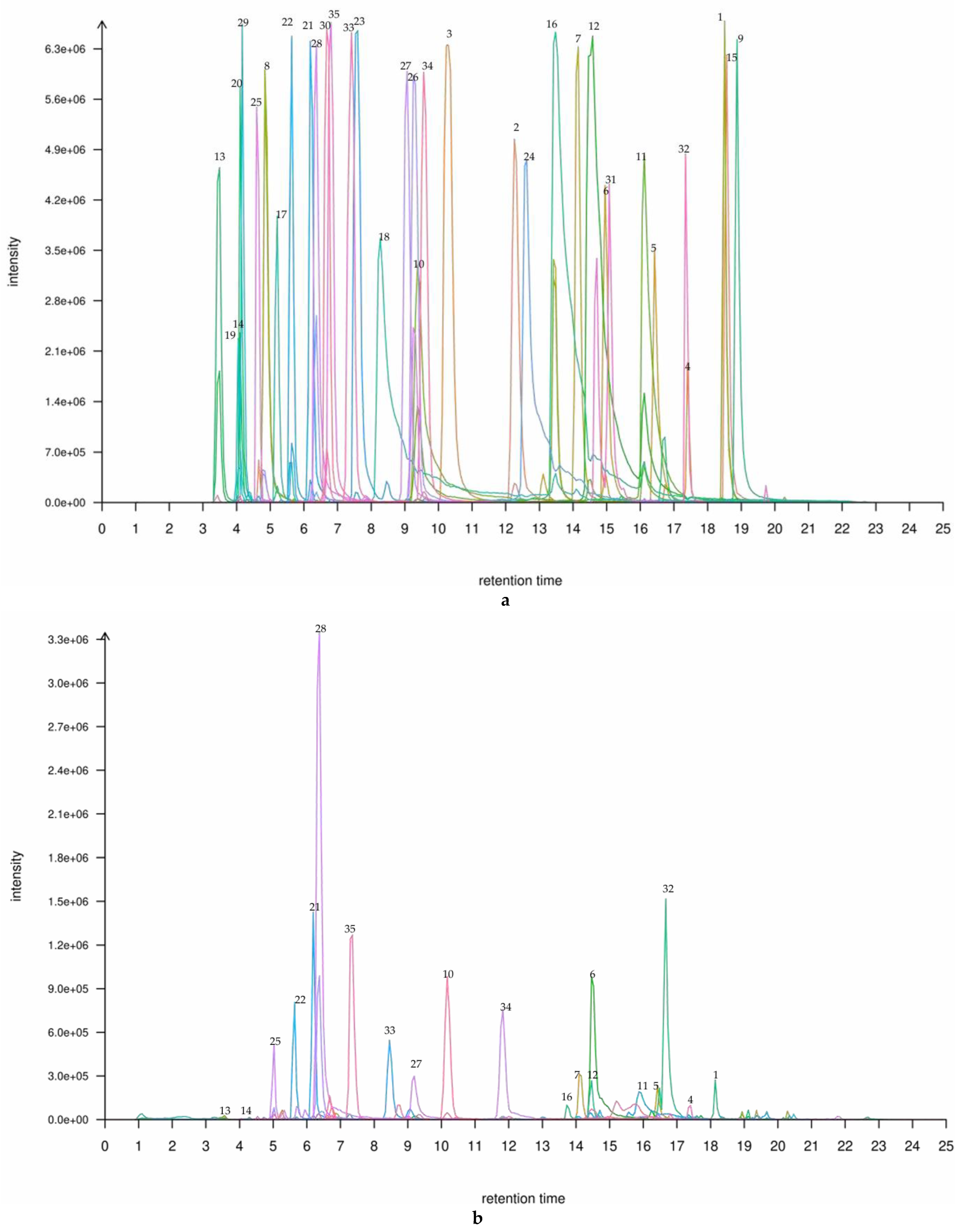

3.1.1. Total Ion Flow Chromatogram

3.1.2. Standard Curve and Limit of Quantification

3.2. Results and Analyses of Quality Assessment (QA) and Quality Control (QC)

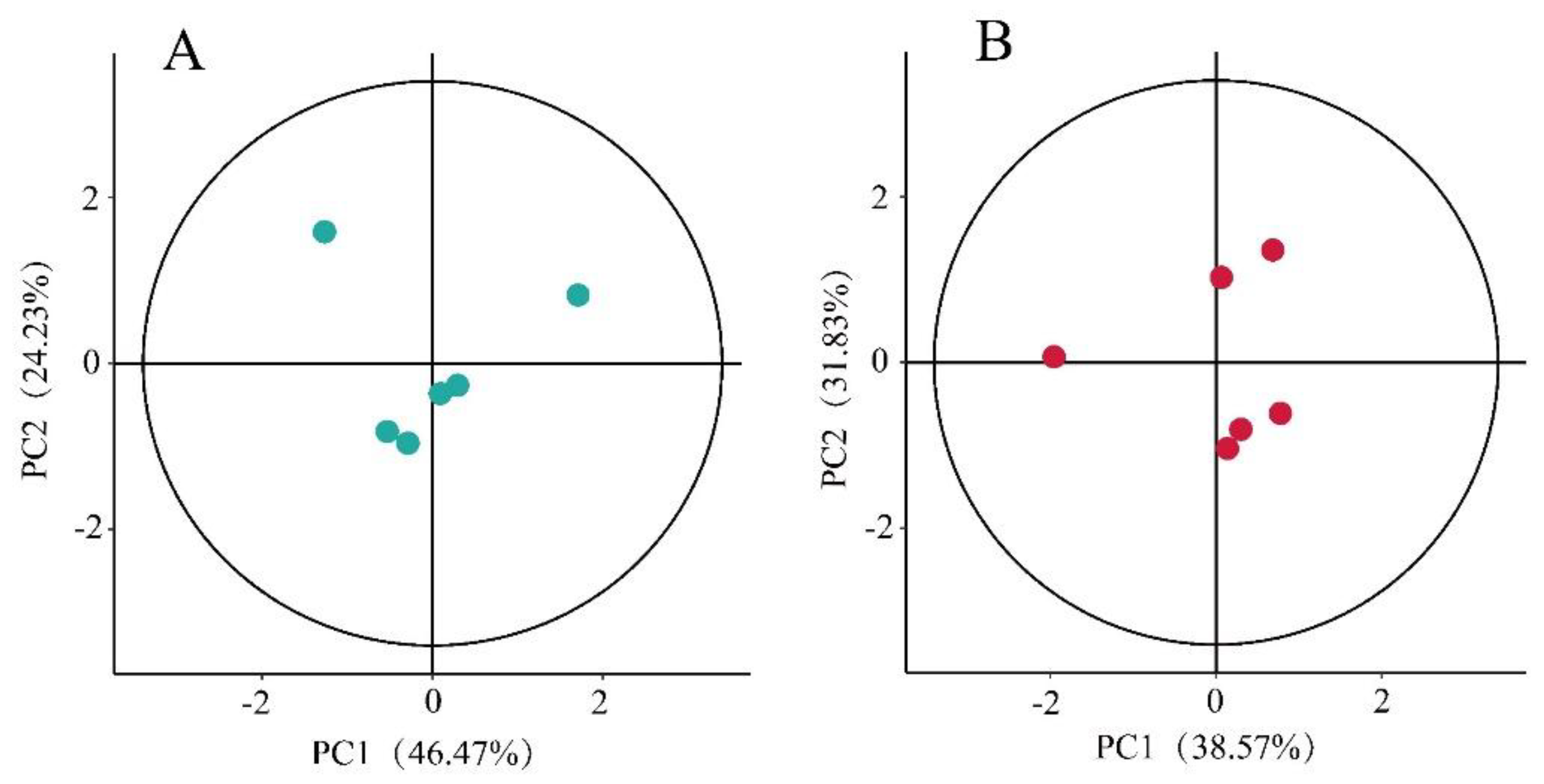

3.2.1. QA Results and Analyses

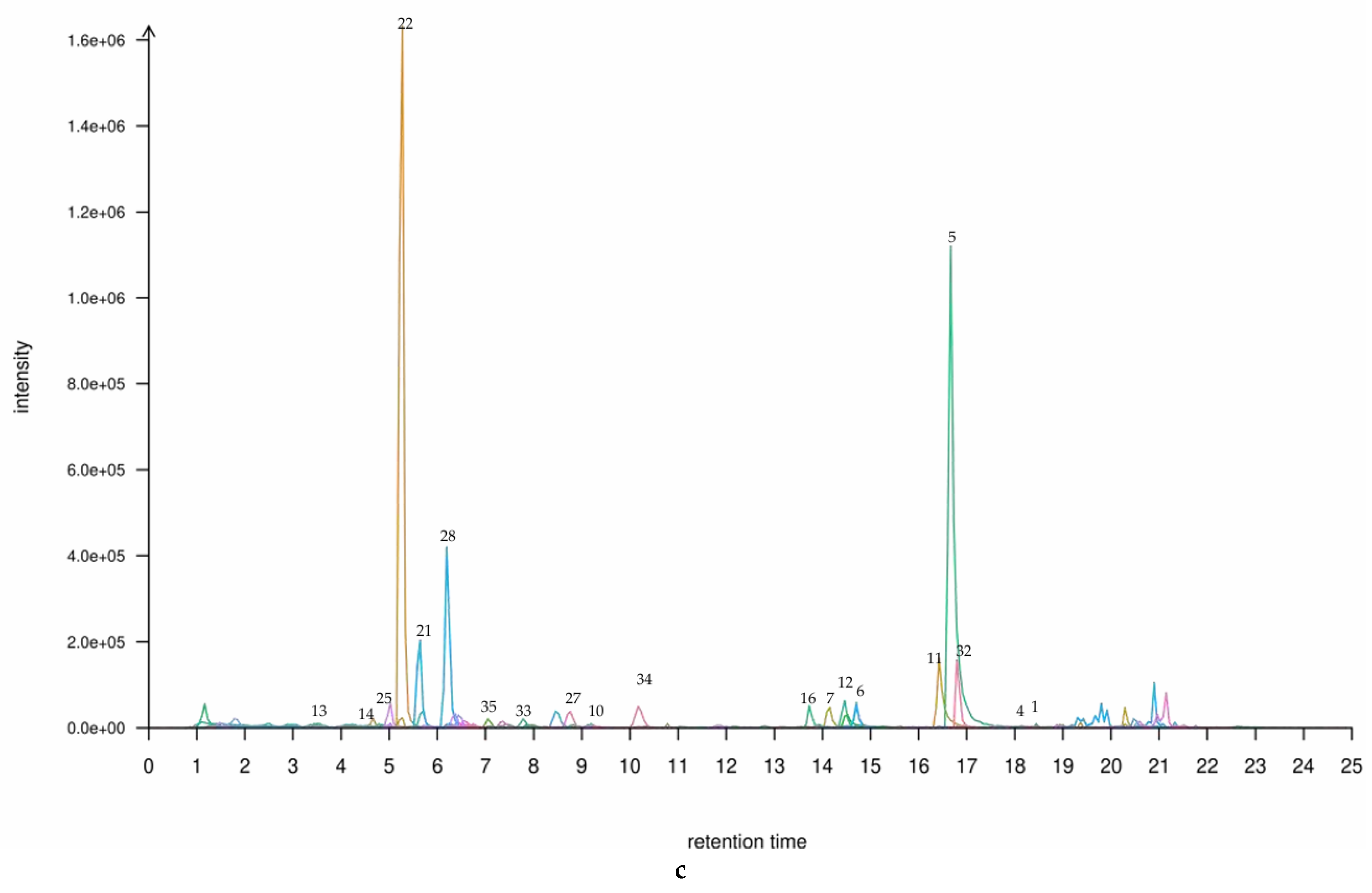

3.2.2. QC Results and Analyses

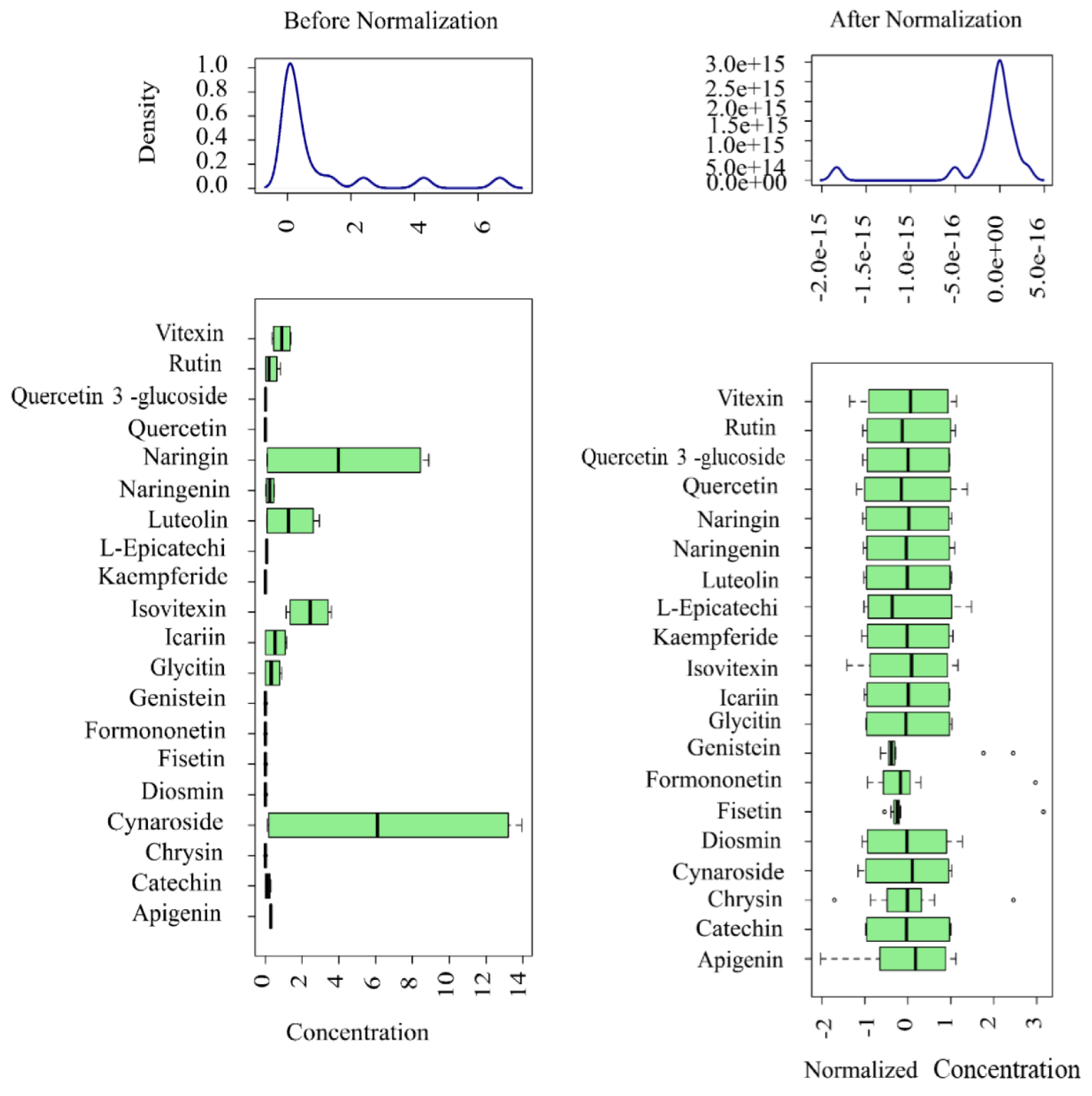

3.2.3. Standardized Results and Analysis

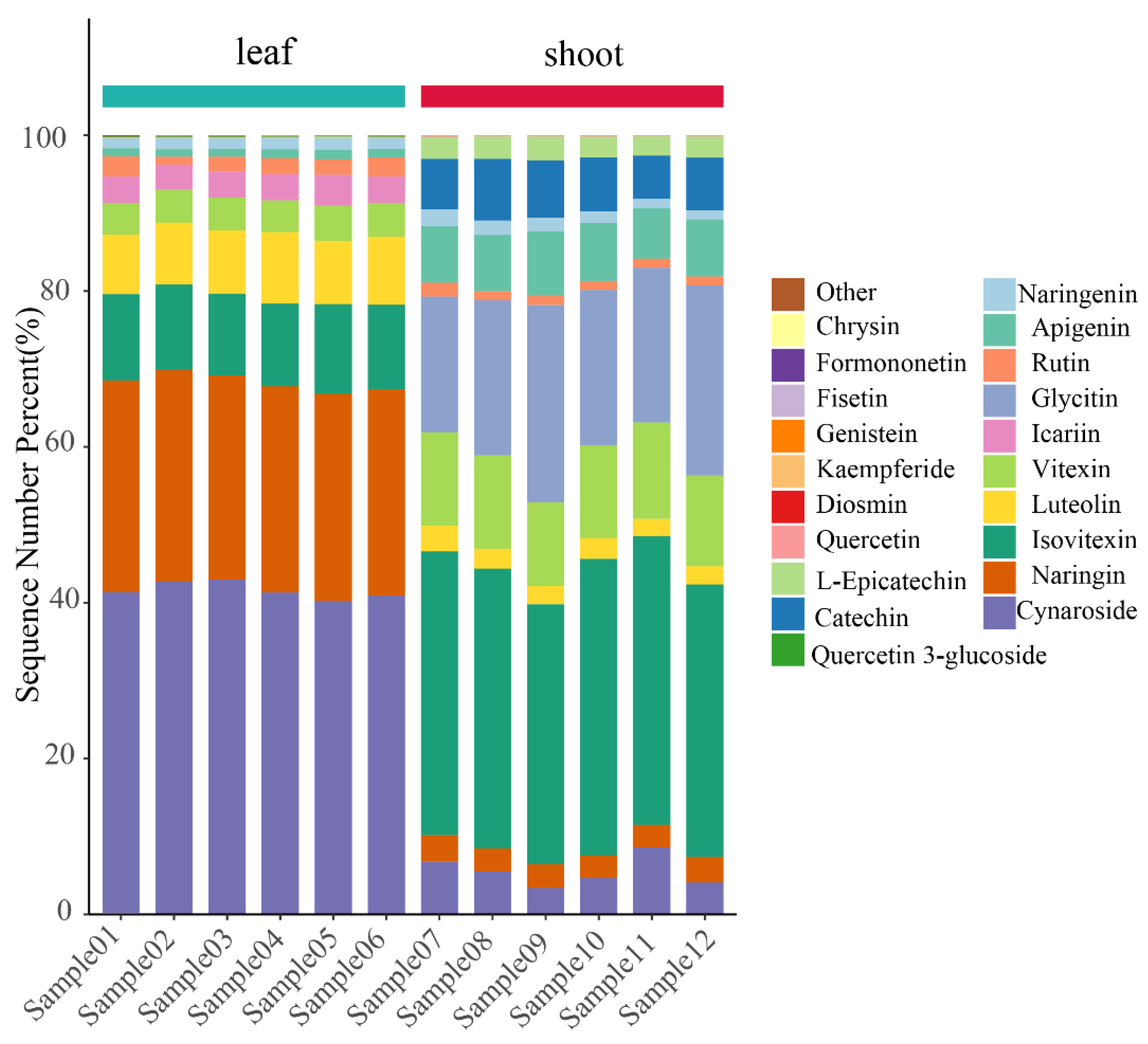

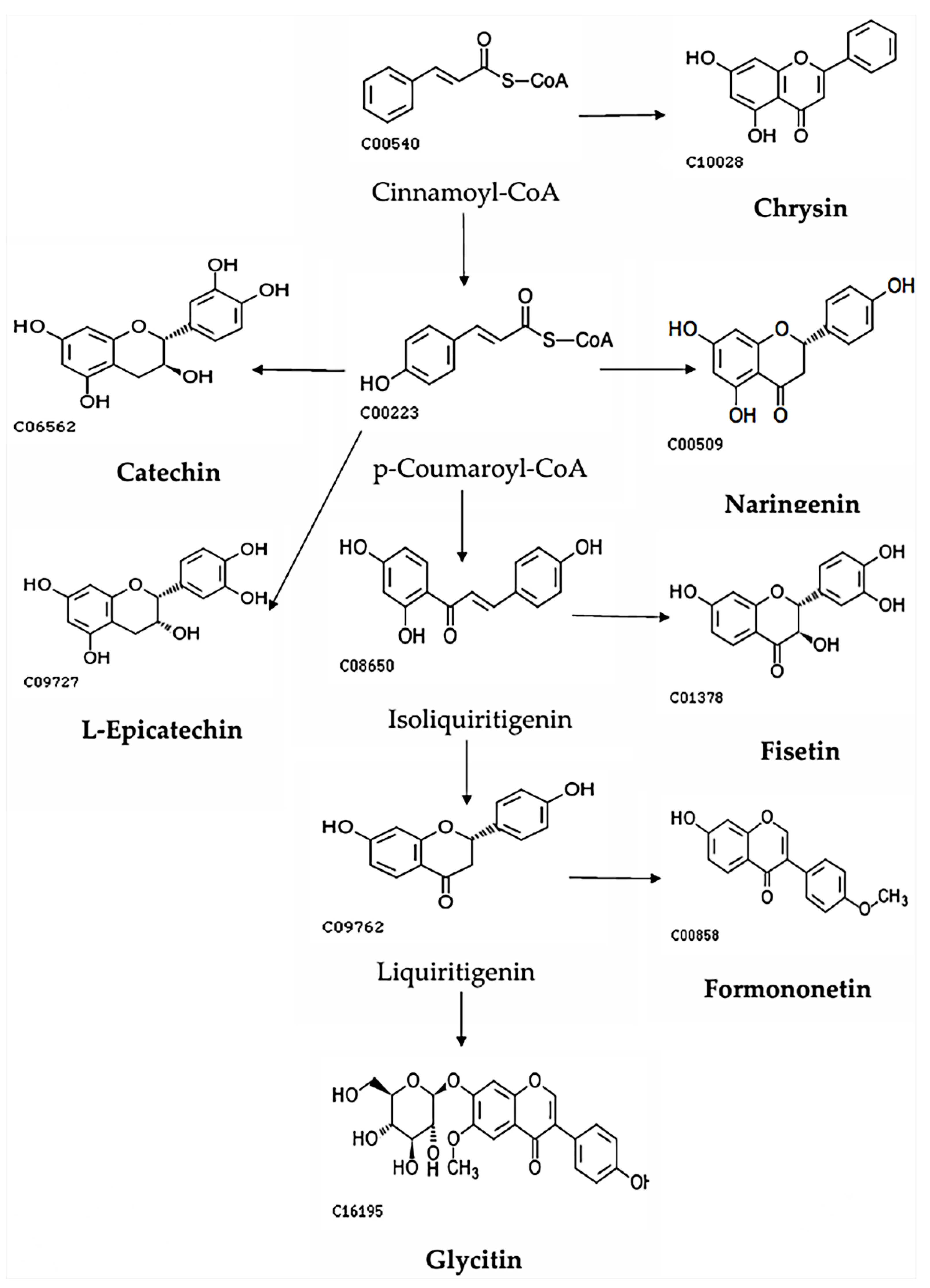

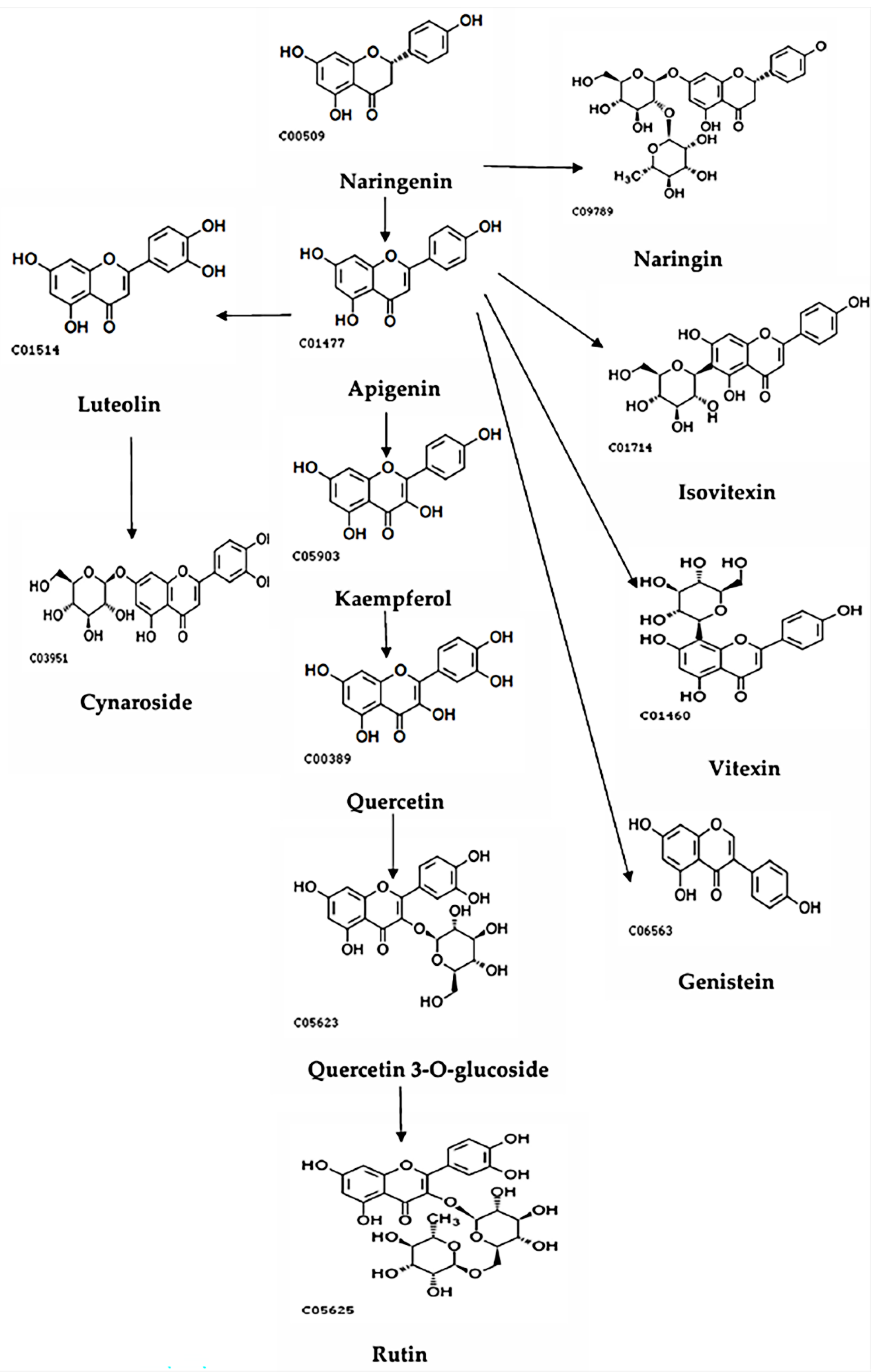

3.2.4. Identification and Analysis of Flavonoids in P. amarus Leaves and Shoots

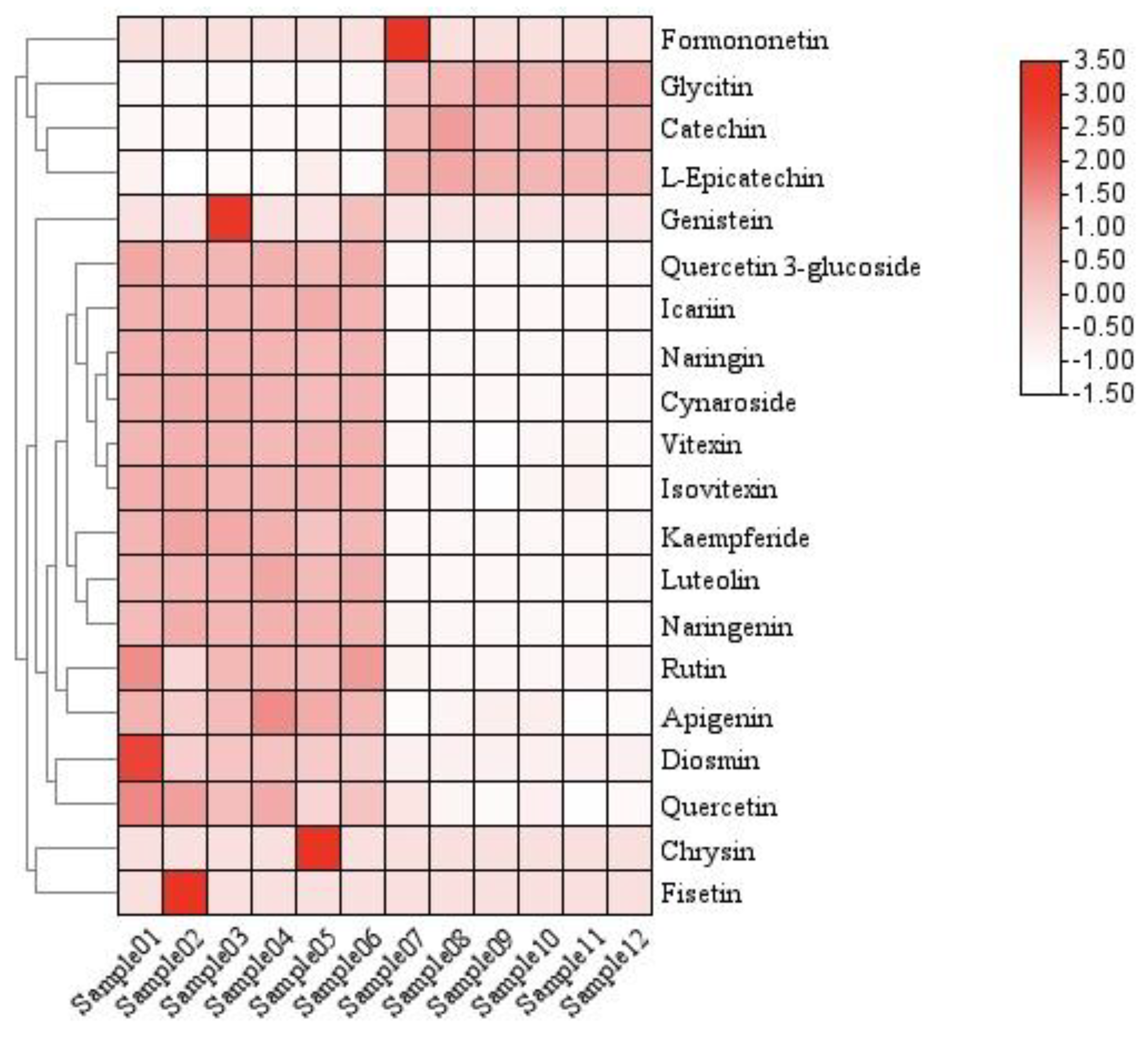

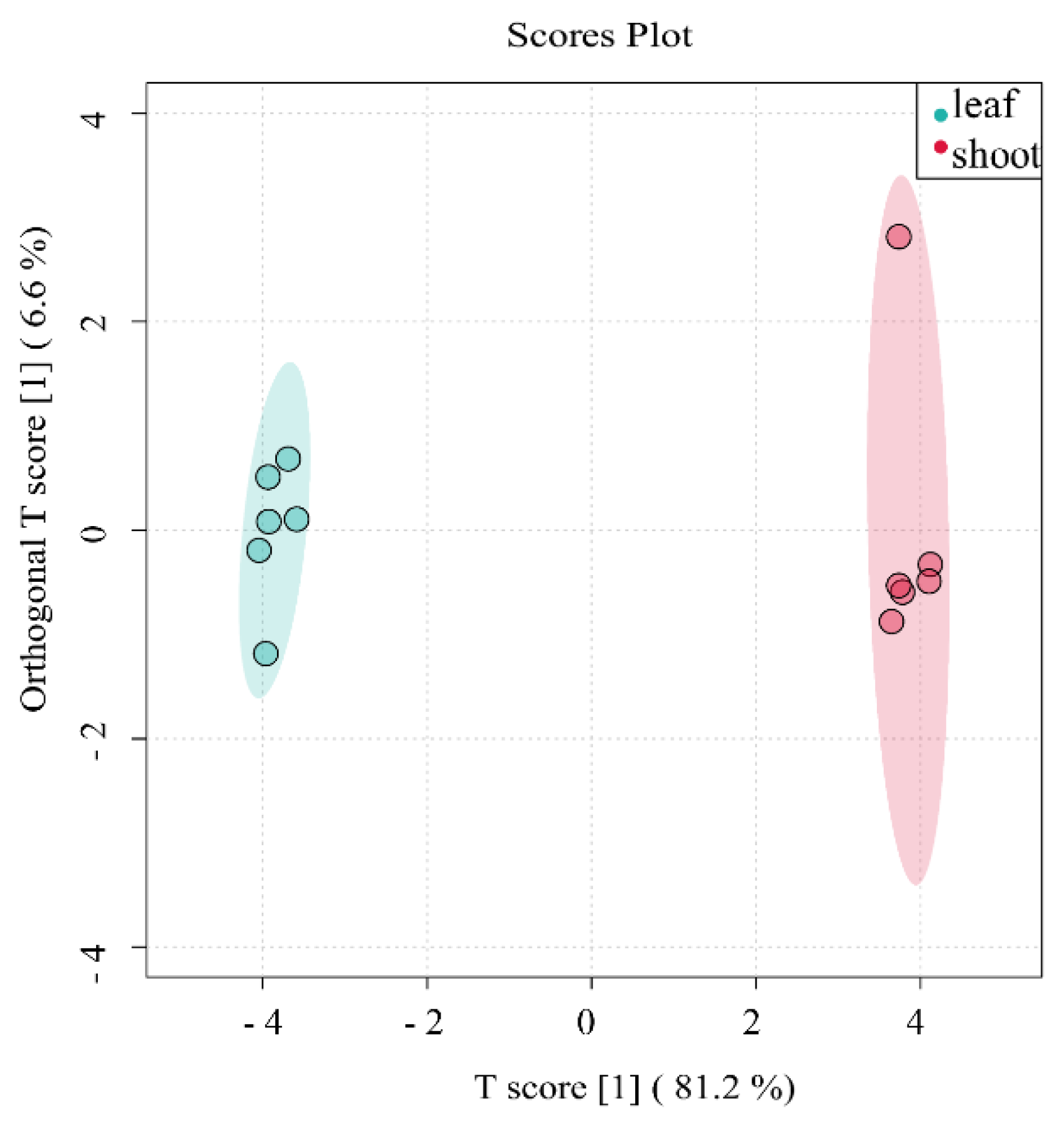

3.2.5. Structural Similarity Analysis of Flavonoid Compositions in P. amarus Leaves and Shoots

3.2.6. Differential Analysis of Flavonoids in P. amarus leaves and Shoots

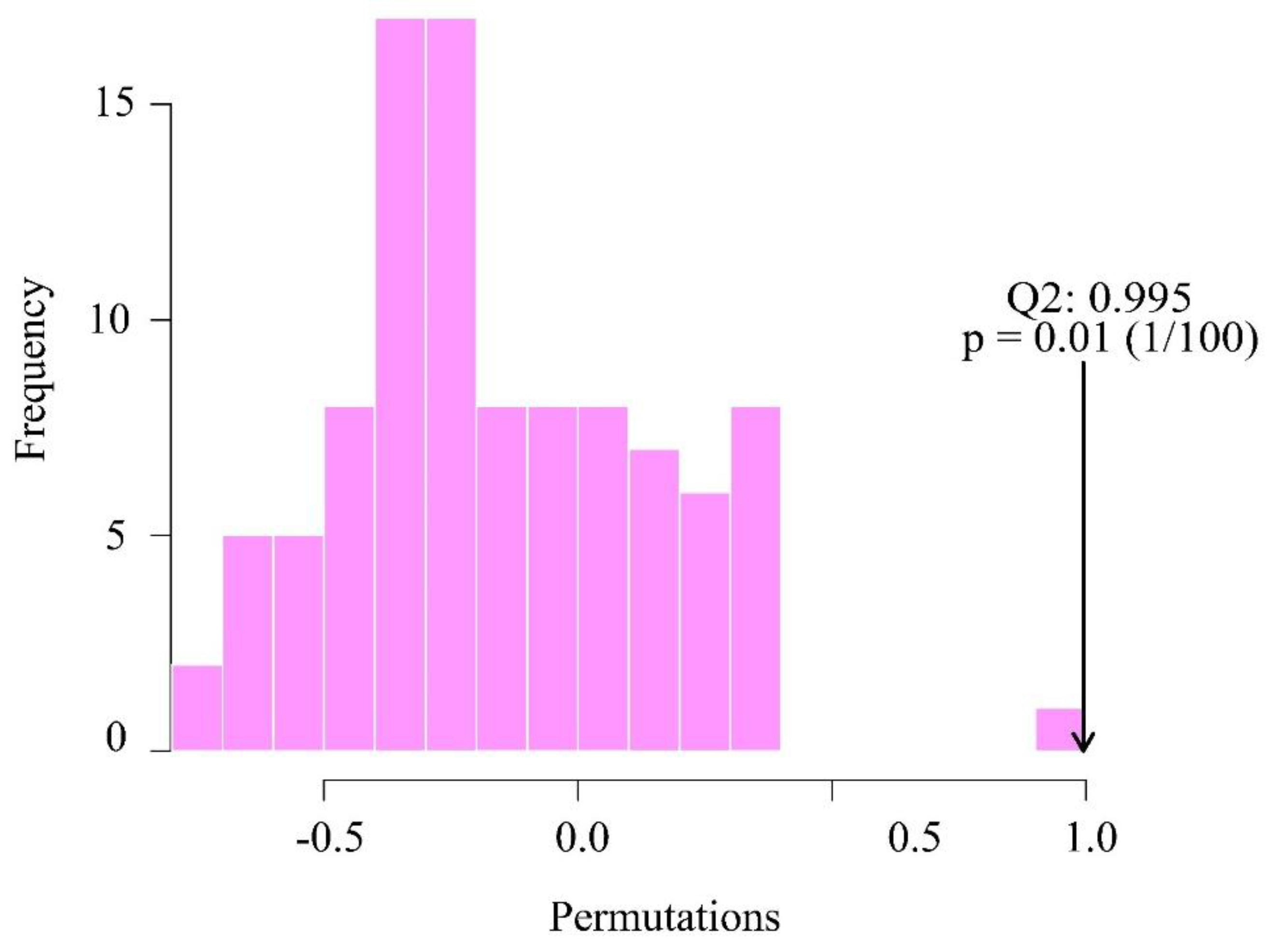

3.2.7. Screening of Characterized Flavonoids in P. amarus leaves and Shoots

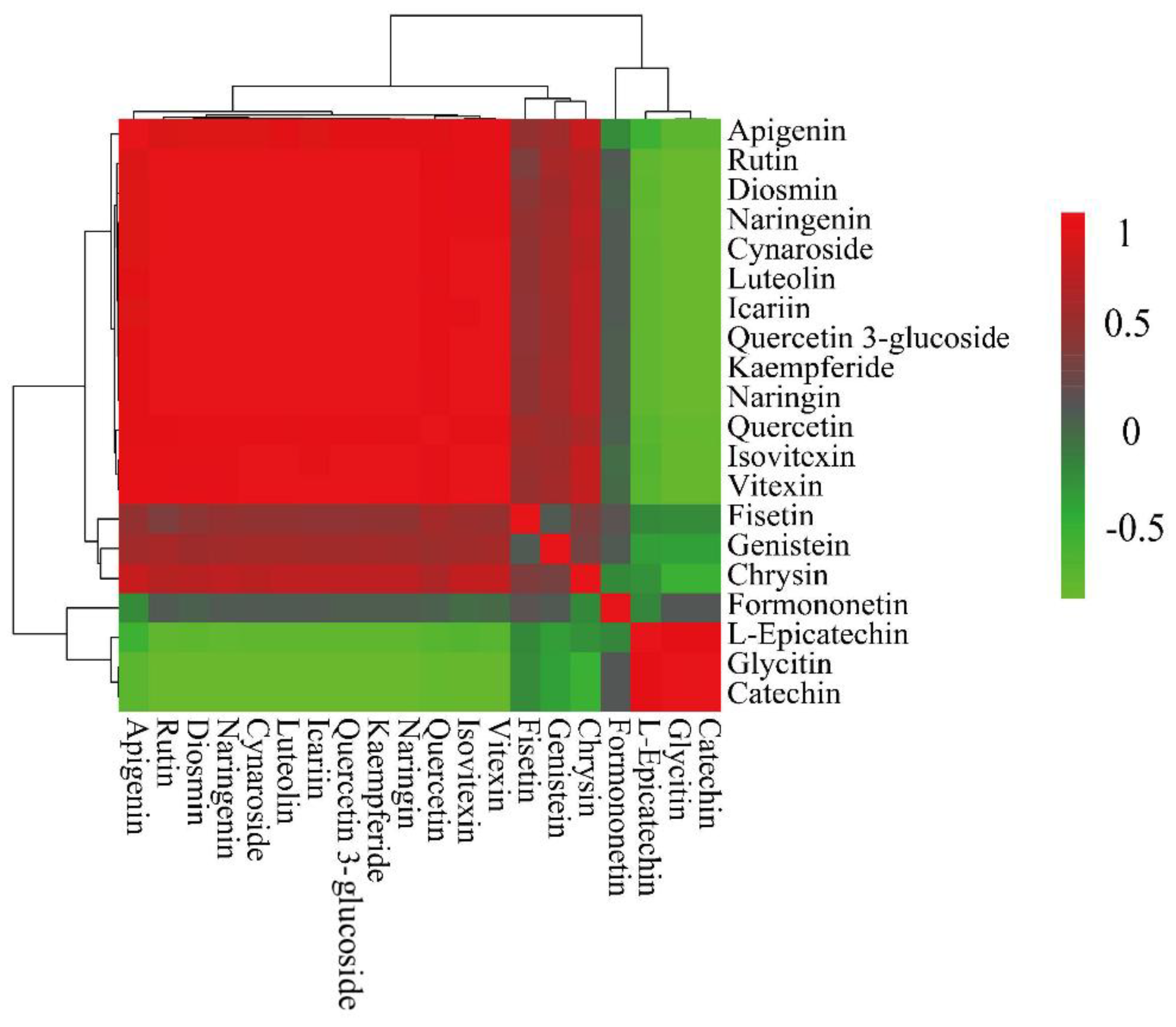

3.2.8. Correlation Analysis of flavonoids in P. amarus Leaves and Shoots

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Jiang,Z. Bamboo and Rattan in the World. Bamboo and Rattan 2007,189.

- Shi, J.Y.; Ma, L.S.; Zhou, D.Q.; Zhou, Z.H.; Pu, Z.Y.; Yao, J.; Be Zhang, Q.X.; Jin, X.B. The history and current situation of resources and development trend of the cultivated bamboos in China. Acta Horticulturae 2014,71-78. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q. Chemical Components and Biological Activites of Pleioblastus Nakai Leaves. Chinese Academy of Forestry 2013,43,97-103.

- Tao, H. List of famous doctors. 1986, 126.

- Li, F; Li, Q; Gao, D; Feng, C; Gao, J. Research developm ent on the iso lation and purification of natural flavonoid. Jiangsu Condiment and Subsidiary Food 2008, 25, 6.

- Serafini, M.; Peluso, I.; Raguzzini, A. Flavonoids as anti-inflammatory agents. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2010, 69, 273-278.

- Yi, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Wu, X.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, L. [Advances in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of several important secondary metabolites in plant metabolomics]. Chinese Journal of Biotechnology 2022, 38, 3674–3681. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S; Dong, J; Liu, J; Jia, Z; Yan, X; Yu, Y;Chen, Y; Li, Y; Xiao, H. Study on the Separation of Flavonoids from Astragalus membranaceus by Supercritical Fluid Chromatography. Journal of Instrumental Analysis 2021, 40, 1311-1317.

- Xiao, Y; Zhang, T; Hou, J. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of flavonoids in Pleioblastus amarus leaves. Journal of Ningbo University of Technology 2001, 13, 125-127+177.

- Guo, J; Wang, H; Shen, Z; Zhang, T; Yuan, X; Ding, Y. Analysis of antioxidant effective components in three kinds of bamboo leaves. Chinese Traditional Patent Medicine 2019, 41, 2688-2694.

- Wang, H; Yao, H; Gu, W; Qin, G. Chemical Constituents from the Leaves of Pleioblastus amarus (keng) keng f. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs 2004, 24-25.

- Wei, Q; Yue, Y; Tang, F; Sun, J; Wang, S; Yu, J. Chemical Constituents from the Leaves of Pleioblastus amarus (keng) keng f. Natural Product Research and Development 2014, 26, 38-42.

- Li, X.; Tao, W.; Xun, H.; Yao, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Yue, Y.; Tang, F. Simultaneous Determination of Flavonoids from Bamboo Leaf Extracts Using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Rev. Bras. de Farm. 2021, 31, 347–352. [CrossRef]

- Hua, M; Chen, J; Bi, W; Kong, J; Hu, Y; Li, Y; Yang, Y; Wang, J. Determination of Total Flavonoids and Vitexin, Isovitexin, Orientin, Isoorientin in Cluster Bamboo by High-performance Liquid Chromatography. Journal of West China Forestry Science 2018, 47, 86-90+95.

- Xie, J.; Lin, Y.-S.; Shi, X.-J.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Su, W.-K.; Wang, P. Mechanochemical-assisted extraction of flavonoids from bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) leaves. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 43, 276–282. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. Pilot scale study on extraction and purification of Phyllostachys edulis leaf flavonoid in Chishui City in Guizhou province. Guizhou University 2022, 32.

- Zhang, C. Technics on Extraction and Purification of FlavoneC-glycosides from Phyllostachys edulis Leaves. Chinese Academy of Forestry 2014, 12.

- Ding, J. Extraction and Separation of Flavonoids from Bambusa surrectaand Its Antibacterial activity. Wuhan Polytechnic University 2015, 32.

- Sun, A.D. A new natural food preservative produced from bamboo leaf flavonoids. China National Intellectual Property Administration 2009, 2.

- Sun, W; Li, X; Li, N; Meng, D. Chemicalof the extraction of bambo0constituentsleaves from Phyllostachys nigra(Lodd.ex Lindl.) Munro var.henonis (Mitf.) Stepf.ex Rendle. Journal of Shenyang Pharmaceutical University 2008, 25, 39-43.

- Zhang, Y.; Jiao, J.; Liu, C.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y. Isolation and purification of four flavone C-glycosides from antioxidant of bamboo leaves by macroporous resin column chromatography and preparative high-performance liquid chromatography. Food Chem. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H; Zheng, W; Chen, Z. Cmponent Study on Flavonoids From Leaves of Dendrocalamus Latiflorus. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin Vol 2005, 114-118.

- An, R; Yuan, T; Guo, X. Quantification and Antioxidant Activity of Flavonoids in Bamboo Leaves Extract of Bambusa. Chemistry and Industry of Forest Products 2023, 43, 97-103.

- Guo, X.F.; Yue, Y.D.; Tang, F.; Wang, J.; Yao, X.; Sun, J. Simultaneous Determination of Seven Flavonoids in Dan Bamboo P hyllostachys glauca McC lure Leaf Extract and in Commercial Products by HPLC-DAD. Journal of Food Biochemistry 2013, 37, 748-757.

- Wei, Q; Yue, Y; Tang, F; Sun, J. Comparison of Flavonoids in the Leaves of Three Genera of Bamboo. Scientia Silvae Sinicae 2013, 49.

- Chen, D. Qualitative and quantitative research for the main flavonoids in bamboo leaves of Phyllostachys. Chinese Academy of Forestry 2021, 33.

- Cui, J. Flavonoids and Volatile Components from Indocalams Leaves. Chinese Academy of Forestry, 2012, 22.

- Li, H.; Sun, J; Zhang, J; Shou, D. Determination of orientin, isoorientin, isovitexin in Bamboo Leaf from different sources by HPLC. Chinese Traditional Patent Medicine 2004, 38-40.

- Yuan, T. Qualitative study of flavonoids in the Bambusa chungii and Bambusa textiles leaves extract using mass spectrometry. Chinese academy of forestry 2023, 37.

- Wang, J.; Yue, Y.-D.; Tang, F.; Sun, J. TLC Screening for Antioxidant Activity of Extracts from Fifteen Bamboo Species and Identification of Antioxidant Flavone Glycosides from Leaves of Bambusa. textilis McClure. Molecules 2012, 17, 12297–12311. [CrossRef]

- Sun G. Studies on Chemical Constituents and Biological Activites of Bambusa pervariabilis McClure Leaves. Chinese Academy of Forestry 2011, 22.

- Zhou, Y. Analysis of Flavonoids in Bamboo Leaf by High performance liquid chromatography. Journal Of Analytical Chemistry 1996, 216-219.

- Zhao, Y; Yang, X; Zhao, X; Zhong, Y. Research Progress on Regulation of Plant Flavonoids Biosynthesis. Science and Technology of Food Industry 2021, 42, 454-463.

- Xing, W; Jin, X. Recent Advances of MYB Transcription Factors Involved in the Regulation of Flavonoid Biosynthesis. Molecular Plant Breeding 2015, 13, 689-696.

- Zhang, J.-Y.; Long, Y.-Q.; Zeng, J.; Fu, X.-S.; He, J.-W.; Zhou, R.-B.; Liu, X.-D. [Transcriptional regulation mechanism of differential accumulation of flavonoids in different varieties of Lonicera macranthoides based on metabonomics and transcriptomics]. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica 2024, 49, 2666–2679. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Long, Y.-Q.; Li, C.; Zeng, M.; Yang, M.; Zhou, X.-R.; Liu, X.-D.; Zhou, R.-B. [Cloning and function analysis of chalcone isomerase gene and chalcone synthase gene in Lonicera macranthoides]. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica 2022, 47, 2419–2429. [CrossRef]

- Azuma, A.; Yakushiji, H.; Koshita, Y.; Kobayashi, S. Flavonoid biosynthesis-related genes in grape skin are differentially regulated by temperature and light conditions. Planta 2012, 236, 1067–1080. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S; Cui, C; Wang, H; Cao, Z; Li, X; Sun, J. Effects of Different Temperature on Growth and Physiological Biochemical.

- Compositions of Nitzschia palea. Current Biotechnology 2012, 2, 48-51.

- Zhou, M; Shen, Y; Zhu, L; Ai, X; Zeng, J; Yang, H. Research Progress on Biosynthesis, Accumulation and Regulation of Flavonoids in Plants. Food Research And Development 2016, 37, 216-221.

- Hao, G.; Du, X.; Zhao, F.; Shi, R.; Wang, J. Role of nitric oxide in UV-B-induced activation of PAL and stimulation of flavonoid biosynthesis in Ginkgo biloba callus. Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2009, 97, 175–185. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M,; Gao, Q; Wang, D. Application of metabonomics technology based on liquid chromatographmass spectrometer in chemical components of traditional Chinese medicine. China Medical Herald 2020, 17, 133-136.

- Wan, L. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and purification offavonoidsfrom mulberry leaves and inhibition of xanthine oxide enzyme. Nanchang University 2020, 31.

- Liao, S.; Ren, Q.; Yang, C.; Zhang, T.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Qu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry Determination and Pharmacokinetic Analysis of Amentoflavone and Its Conjugated Metabolites in Rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 1957–1966. [CrossRef]

- Dong, L; Liu, J; Li, L; Chen, X; Dan, W; Zhong, D. Simultaneous determination of flavonol glycoside and its major metabolites by LC-MS/MS in rat plasma. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica 2018, 53, 1345-1351.

- Fu, C; Cui, X; Pei, X ; Du, C; Yan, Y. Simultaneous determination of six chemical components in Ziziphi Spinosae Folium by LC-MS/MS. Journal of Shanxi Medical University 2020, 51, 666-673.

- Zhan, J. Pharmacokinetics of main metabolites of Epimedium extract in rats. Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, 2019, 23.

- Zhang, X; Duan, J; Qian, D. Identification of flavonoids from Eupatorium lindeyanum and compound Yemazhui capsules by LC-MS/MS. Journal of China Pharmaceutical Universit 2008, 39, 147-150.

- Jiang, X; Fang, A; Du, W; Ruan, C.LC-MS/MS detection of flavonoids in Xanthoceras sorbifolum Bunge kernel from different origins. China Oils And Fats 2023, 48, 133-140.

- Fraga, C.G.; Clowers, B.H.; Moore, R.J.; Zink, E.M. Signature-discovery approach for sample matching of a nerve-agent precursor using liquid chromatography− mass spectrometry, XCMS, and chemometrics. Analytical chemistry 2010, 82, 4165-4173.

- Han, J.S.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, C.H. MS-Based Metabolite Profiling of Aboveground and Root Components of Zingiber mioga and Officinale. Molecules 2015, 20, 16170–16185. [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Guo, S. Comparative analysis of flavonoid metabolites from different parts of Hemerocallis citrina. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Sumner, B.W.; Bhatia, A.; Sarma, S.J.; Sumner, L.W. UHPLC-MS analyses of plant flavonoids. Current protocols in plant biology 2019, 4, e20085.

- Wang, T.; Xiao, J.; Hou, H.; Li, P.; Yuan, Z.; Xu, H.; Liu, R.; Li, Q.; Bi, K. Development of an ultra-fast liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry method for simultaneous determination of seven flavonoids in rat plasma: Application to a comparative pharmacokinetic investigation of Ginkgo biloba extract and single pure ginkgo flavonoids after oral administration. J. Chromatogr. B 2017, 1060, 173–181. [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, A.; Venter, P.; Pasch, H. Recent advances and trends in the liquid-chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of flavonoids. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1430, 16–78. [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.; Xia, J. MetaboAnalystR: An R package for flexible and reproducible analysis of metabolomics data. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 4313–4314. [CrossRef]

- Karak, P. Biological activities of flavonoids: An overview. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res 2019, 10, 1567-1574.

- Du, Y; Ma, S; Wu, Y; Xu, Y; Huang, X; Zhong, J. Determination and Analysis of Polysaccharide and Flavonoid Content of Different Parts of Mesona chinensis and Research on Hydroponics. Chinese Journal of Tropical Agriculture 2023, 43, 39-48.

- Wang, Y; Wang, Y; Du, Z; Li, J; Chen, S. Research progress on chemical composition and pharmacological effects of different parts of Prunella valgaris and predictive analysis on quality marker. Chinese Archives of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2014, 1-33.

- Dong, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Luo, J. Comprehensive profiling and natural variation of flavonoids in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2014, 56, 876–886. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Sun, G. Hypolipidemic Effects and Preliminary Mechanism of Chrysanthemum Flavonoids, Its Main Components Luteolin and Luteoloside in Hyperlipidemia Rats. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1309. [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Li, R.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, T.; Xu, T.; Zogona, D.; Huang, Y.; Pan, S.; Xu, X. Vitexin and Isovitexin Act through Inhibition of Insulin Receptor to Promote Longevity and Fitness in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, e2100845. [CrossRef]

- Stabrauskiene, J.; Kopustinskiene, D.M.; Lazauskas, R.; Bernatoniene, J. Naringin and Naringenin: Their Mechanisms of Action and the Potential Anticancer Activities. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1686. [CrossRef]

- Imani, A.; Maleki, N.; Bohlouli, S.; Kouhsoltani, M.; Sharifi, S.; Dizaj, S.M. Molecular mechanisms of anticancer effect of rutin. Phytotherapy Res. 2020, 35, 2500–2513. [CrossRef]

- Bi, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yan, X. Anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects of icariin and icaritin. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113180. [CrossRef]

- Cesar, P.H.S.; Trento, M.V.C.; Konig, I.F.M.; Marcussi, S. Catechin and epicatechin as an adjuvant in the therapy of hemostasis disorders induced by snake venoms. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2020, 34, e22604. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, S.; Jiang, K.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Guo, M. Glycitin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via inhibiting NF-κB and MAPKs pathway activation in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 75, 105749. [CrossRef]

- Chandrababu, G.; Varkey, M.; Devan, A.R.; Anjaly, M.V.; Unni, A.R.; Nath, L.R. Kaempferide exhibits an anticancer effect against hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2023, 396, 2461–2467. [CrossRef]

- Geshnigani, S.S.H.; Mahdavinia, M.; Kalantar, M.; Goudarzi, M.; Khorsandi, L.; Kalantar, H. Diosmin prophylaxis reduces gentamicin-induced kidney damage in rats. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2022, 396, 63–71. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Arif, Y.; Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. The role of quercetin in plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2021, 166, 10-19.

- Zhang, X; Guo, L; Yang, F; Hu, W; Sheng, Z. Study on Anti-diarrhea Effect of Isoquercitrin. Chinese Journal of Veterinary Medicine 2023, 59, 138-143.

- Chen, W.; Balan, P.; Popovich, D.G. Comparison of Ginsenoside Components of Various Tissues of New Zealand Forest-Grown Asian Ginseng (Panax Ginseng) and American Ginseng (Panax Quinquefolium L.). Biomolecules 2020, 10, 372. [CrossRef]

| Species name | Materials and Methods | Flavonoids of dry weight (μg/g) |

|---|---|---|

| Dendrocalamus bambusoides Mei Hua et al. [14] | Leaves; HPLC | Vitexin, Isovitexin, Orientin, and Isoorientin |

| Phyllostachys edulis Xie et al. [15] | Leaves; an efficient mechanochemical-assisted extraction | Vitexin, Isovitexin, and Isoorientin |

| Phyllostachys edulis Jianfei Zhou [16] and Chunjuan Zhang [17] | Leaves; HPLC | Vitexin, Isovitexin, Orientin, and Isoorientin |

| Bambusa surrecta Jiefeng Ding et al. [18] | Stem; HPLC | Rutin (0.162), Kaempferitrin (0.401), Hyperin (0.927), Kaempferol-3-O-β-D-glucosyl(1-2)rhamnoside (0.456), and Kaempferol (0.601) |

| Bambusa surrecta Jianfen Li et al. [19] | Stem; HPLC | Vitexin, Isovitexin, Orientin, Isoorientin, 3',5'-di-O-methyltricetin, Kaempferol, Quercetin, Luteolin - 6 - C – rutoside, Luteolin - 7 - O –glucoside, and 3',5'-di-O-methyltricetin - 7 - O –glucoside |

| Phyllostachys nigra Wuxing Sun et al. [20] | Leaves; repeated silica gel column chromatography, preparative thin-layer chromatography | 3',5'-di-O-methyltricetin,3',5'-di-O-methyltricetin - 7 - O -β- D - glucoside, Vitexin, 3',5'-di-O-methyltricetin - 7 - O - neohespeidoside, Orientin, and Isoorientin |

| Phyllostachys nigra Zhang et al. [21] | Leaves; macroporous resin adsorption–desorption separation | Vitexin, Isovitexin, Orientin, and Isoorientin |

| Dendrocalamus latiflorus Haoguo Tang et al. [22] | Leaves; nature and spectroscopy | Vitexin, Rutin, and Kaempferol |

| Bambusa textilis Rongmiao An et al. [23] | Leaves; HPLC | Vitexin (3.99), Isovitexin (122.23), Orientin (4.87), Isoorientin (78.94), and Cynaroside (17.54) |

| Phyllostachys glauca Guo et al. [24] | Leaves; HPLC | Vitexin, Isovitexin, Orientin, Isoorientin, Luteolin, and 3',5'-di-O-methyltriceti |

| Bambusa textilis$ Qi Wei et al. [25] | Leaves; HPTLC | Vitexin (10.00), Isovitexin (5.00), Orientin (10.00), Isoorientin (12.65), and 3',5'-di-O-methyltricetin (6.00) |

| Phyllostachys edulis $Dandan Chen et al. [26] | Leaves; HPLC | Vitexin (4.42), Isovitexin (22.32), Orientin (2.28), Isoorientin (14.76), and Cynaroside (2.78) |

| Indocalams Latifolius $Jian Cui et al. [27] | Leaves; HPTLC | Vitexin, Isovitexin, Orientin, Isoorientin, Quercetin, and 3',5'-di-O-methyltricetin |

| Phyllostachys reticulata$ Hongyu Li et al. [28] | Leaves; HPLC | Orientin, Isovitexin, and Isoorientin |

| Bambusa chungii, Bambusa textilis $Ting Yuan et al. [29] | Leaves; ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography | Luteolin and Apigenin |

| Bambusa textilis $Jin Wang et al. [30] | Leaves; ultraviolet spectroscopy | Vitexin, Isovitexin, Orientin, and Isoorientin |

| Bambusa pervariabilis $Sun Gu et al. [31] | Leaves; column chromatographic separations | Luteolin, Apigenin, 3',5'-di-O-methyltricetin, and Quercetin |

| Indocalams tessellatus $Hongyao Zhou et al. [32] | Leaves; HPLC | Luteolin and Quercetin |

| Name | Retention time (min) | Linear equation (math.) | Correlation coefficient (r) | Linear range (ng/mL) | Limit of quantification (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chrysin | 18.57 | y=2.1e+005 x+1.04e+004 | 0.9919 | 0.2-100 | 0.2 |

| Daidzein | 12.27 | y= 5.47e+004x+5.37e+003 | 0.9958 | 0.8-400 | 0.8 |

| Liquiritigenin | 10.28 | y= 1.74e+005x+1.54e+004 | 0.9905 | 0.4-400 | 0.4 |

| Formononetin | 17.41 | y= 2.43e+005x+3.74e+003 | 0.9905 | 0.02-40 | 0.02 |

| Apigenin | 16.43 | y= 1.35e+005x+3.74e+003 | 0.9953 | 0.1-200 | 0.1 |

| Genistein | 14.96 | y= 5.19e+004x±238 | 0.9957 | 0.4-400 | 0.4 |

| Naringenin | 14.14 | y=1.72e+005x+1.35e+004 | 0.9951 | 0.2-200 | 0.2 |

| Glycitein | 4.85 | y= 6.6e+005x+1.35e+004 | 0.9942 | 0.2-12.5 | 0.2 |

| Biochanin A | 18.51 | y= 1.48e+006x+7.88e+003 | 0.9922 | 0.02-20 | 0.02 |

| Fisetin | 9.399 | y=1.84e+004x±5.83e+003 | 0.9907 | 0.8-4000 | 0.8 |

| Kaempferol | 16.13 | y= 2.44e+004x+4.96e+003 | 0.9943 | 2-2000 | 2 |

| Luteolin | 14.51 | y= 1.23e+005x+1.52e+004 | 0.9942 | 1-1000 | 1 |

| Catechin | 3.473 | y= 2.99e+0.03x+ 896 | 0.9945 | 2-4000 | 2 |

| L-Epicatechin | 4.11 | y= 1.65e+004x+6.04e+003 | 0.996 | 2-500 | 2 |

| Kaempferide | 18.88 | y= 2.2e+005x+239 | 0.994 | 0.1-200 | 0.1 |

| Quercetin | 13.48 | y= 7.81e+004x±1.31e+004 | 0.9945 | 1-2000 | 1 |

| Taxifolin | 5.202 | y= 2.68e+004x+3.25e+003 | 0.995 | 0.4-800 | 0.4 |

| Myricetin | 8.279 | y= 1.09e+004x±6.81e+004 | 0.991 | 10-10000 | 10 |

| Dihydromyricetin | 4.054 | y= 6.52e+0.03x + 0.419 | 0.9954 | 0.8-1600 | 0.8 |

| Puerarin | 4.17 | y= 1.31e+005x+2.01e+003 | 0.9929 | 0.2-100 | 0.2 |

| lsovitexin | 6.206 | y= 6.46e+004x+4.32e+003 | 0.9966 | 0.4-400 | 0.4 |

| Vitexin | 5.635 | y= 9.91e+004x+6.64e+003 | 0.9929 | 0.2-400 | 0.2 |

| Genistin | 7.564 | y= 1.51e+005x+1.39e+004 | 0.9914 | 0.4-400 | 0.4 |

| Baicalin | 12.6 | y= 1.38e+004x±2.29e+003 | 0.9947 | 2-10000 | 2 |

| Glycitin | 4.825 | y = 196x + 648 | 0.9923 | 20-5000 | 20 |

| Astragalin | 9.293 | y= 6.62e+004x+6.26e+003 | 0.9931 | 0.5-1000 | 0.5 |

| Quercitrin | 9.062 | y= 5.18e+004x+1.93e+003 | 0.9973 | 0.5-1000 | 0.5 |

| Cynaroside | 6.365 | y= 6.72e+004x+1.93e+003 | 0.9952 | 0.4-800 | 0.4 |

| Daidzin | 4.612 | y= 3.29e+004x+ 885 | 0.9909 | 0.5-1000 | 0.5 |

| Quercetin 3-glucoside | 6.797 | y= 7.11e+0.04x+7.24e+003 | 0.9917 | 0.5-1000 | 0.5 |

| Silybin | 15.08 | y= 5.58e+004x+5.04e+003 | 0.9915 | 0.5-1000 | 0.5 |

| Leariin | 17.35 | y= 1.67e+004x+1.74e+003 | 0.993 | 1-1000 | 1 |

| Naringin | 7.417 | y= 3.58e+004x+7.59e+003 | 0.9915 | 1-2000 | 1 |

| Diosmin | 9.572 | y= 7.99e+004x+6.1e+003 | 0.9916 | 0.4-800 | 0.4 |

| Rutin | 6.688 | y= 3.9e+004x+3.55e+003 | 0.9965 | 1-1000 | 1 |

| Number | Flavonoids | RSD% |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chrysin | 2.9524 |

| 2 | Daidzein | 1.3886 |

| 3 | Liquiritigenin | 1.9186 |

| 4 | Formononetin | 0.8529 |

| 5 | Apigenin | 0.8258 |

| 6 | Genistein | 2.2615 |

| 7 | Naringenin | 3.5393 |

| 8 | Glycitein | 1.4077 |

| 9 | Biochanin A | 2.5031 |

| 10 | Fisetin | 0.8905 |

| 11 | Kaempferol | 1.2342 |

| 12 | Luteolin | 3.6766 |

| 13 | Catechin | 2.1821 |

| 14 | L-Epicatechin | 1.9818 |

| 15 | Kaempferide | 4.6315 |

| 16 | Quercetin | 2.3907 |

| 17 | Taxifolin | 1.0088 |

| 18 | Myricetin | 1.9631 |

| 19 | Dihydromyricetin | 1.8401 |

| 20 | Puerarin | 1.6731 |

| 21 | lsovitexin | 1.6845 |

| 22 | Vitexin | 1.0481 |

| 23 | Genistin | 2.8451 |

| 24 | Baicalin | 4.1295 |

| 25 | Glycitin | 2.6372 |

| 26 | Astragalin | 3.5077 |

| 27 | Quercitrin | 3.4076 |

| 28 | Cynaroside | 1.7142 |

| 29 | Daidzin | 1.8017 |

| 30 | Quercetin 3-glucoside | 1.9121 |

| 31 | Silybin | 1.461 |

| 32 | Icariin | 1.3189 |

| 33 | Naringin | 2.3597 |

| 34 | Diosmin | 2.5593 |

| 35 | Rutin | 2.2953 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).