1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global public health challenge; according to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), it is estimated that approximately 10% of the world’s population suffers from some degree of this medical condition. Millions of people die annually from associated complications, such as cardiovascular disease or multi-organ failure (IHME, 2020). This progressive medical condition is characterized by a gradual and irreversible loss of kidney function, resulting in the accumulation of toxic metabolic products, hydro electrolyte imbalance, and severe endocrine disruption. Currently, available treatments include dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) and kidney transplantation (Monardo et al., 2021). These options have considerable limitations. First, dialysis does not replace the complex functions of the kidney. As a result, the patient’s quality of life is impaired due to prolonged sessions, risk of infection, and physical exhaustion. On the other hand, kidney transplantation offers a more comprehensive solution, but it is limited by the scarcity of available donor organs, surgical risks, and the need for permanent immunosuppression (Abramyan & Hanlon, 2023).

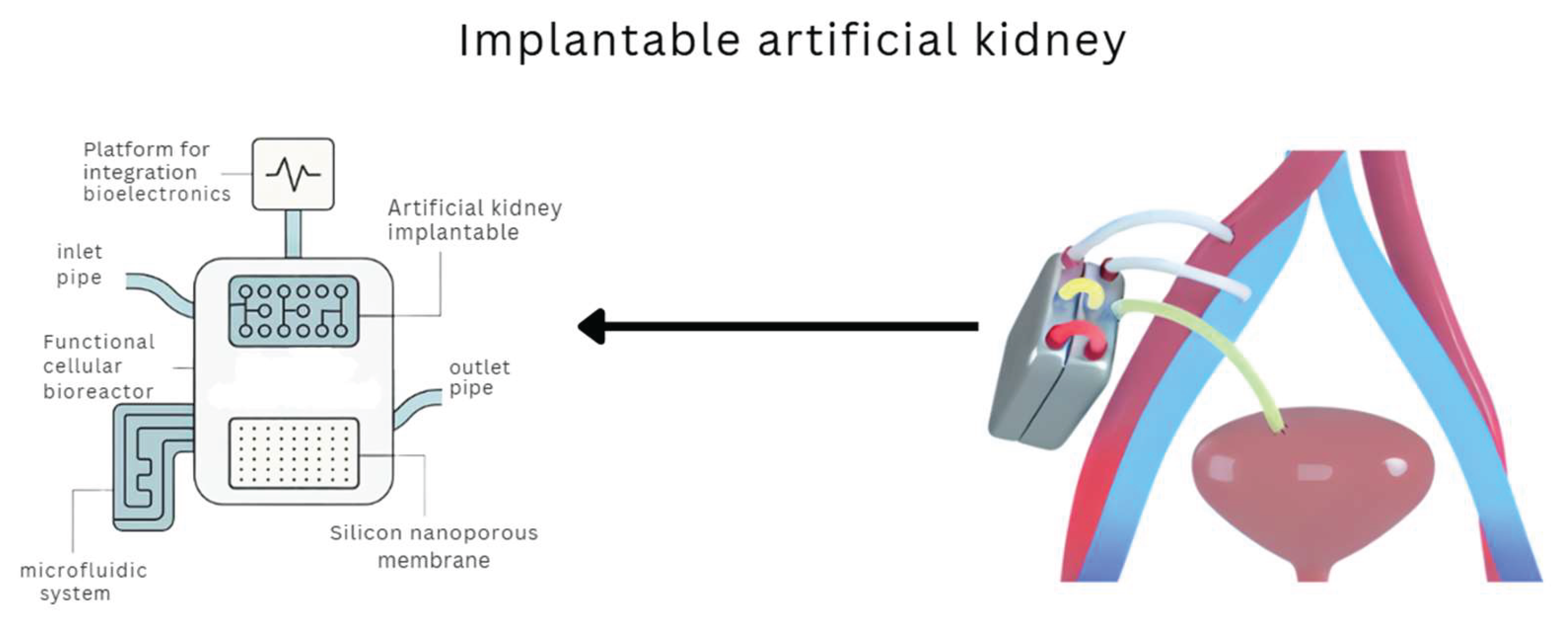

Faced with these challenges, biomedical engineering has directed its efforts toward developing artificial organs that provide basic functions and emulate the physiological mechanisms of the original organ. In this context, the concept of the implantable artificial kidney emerges as an innovative and potentially revolutionary alternative. This device aims to filter metabolic waste and restore critical functions such as hydroelectrolyte regulation, hormone secretion (e.g., erythropoietin), and acid-base balance (Wieringa et al., 2025). The implantable artificial kidney combines multiple technological advances, such as silicon nanoporous membranes, cellular bioreactors, biomimetic microfluidics, and integrated sensors that allow constant monitoring of physiological parameters. These technologies allow more accurate replication of the nephrons’ function, representing a qualitative leap from conventional substitution therapies. Unlike dialysis, an implantable artificial kidney could offer continuous, ambulatory, and integrated therapy to the patient’s body, significantly improving its autonomy and quality of life (Groth et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2023).

Developing such devices requires an interdisciplinary collaboration between biomedical engineers, nephrologists, biochemists, materials scientists, and health regulatory experts. Its implementation poses ethical and social challenges such as equitable access, cultural acceptance, economic sustainability, and long-term security (Bunnik et al., 2022).

This study presents a comprehensive review of the current technology related to implantable artificial kidneys, analyzing aspects such as the most significant advances, outstanding challenges, and future perspectives. Special attention is given to the structural, functional, and regulatory components, comparing strategies and prototypes developed worldwide. Its purpose is to provide a solid foundation for future research and clinical applications in advanced renal therapy.

2. Methodology

To structure the present study, a qualitative-descriptive research methodology was adopted based on a systematic literature review and comparative analysis of the latest technological developments in the area. This methodological approach allows for a holistic view by identifying the strengths, limitations, and emerging opportunities in the design, manufacture, and validation of implantable renal devices (Rondón et al., 2023; Groth et al., 2023; Fissell, 2023; Nagasubramanian, 2021).

2.1. Collection of Data

The data were collected systematically by searching internationally renowned academic databases such as PubMed, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, SpringerLink, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and the European research repository CORDIS. To maximize the completeness of the search, combinations of keywords were used in both English and Spanish, including terms such as “artificial kidney”, “implantable artificial kidney”, “renal replacement therapy”, “silicon nanopore membranes”, “bioartificial kidney”, “renal bioreactor” and “microfluidic systems for nephrology”.

The inclusion criteria were academic publications between 2018 and 2025, peer-reviewed articles, technical reports relevant to the topic, doctoral theses, active research projects, and specialist books. Content strictly related to the design, manufacture, operation, and validation of renal replacement devices was prioritized. On the other hand, exclusion criteria were duplicate articles, non-academic sources without scientific validation, and publications focusing on organs or systems other than the renal.

2.2. Classification and Thematic Analysis

The information collected was organized and classified thematically into five key categories: (1) synthetic membrane filtration technologies, (2) functional kidney cell culture and incorporation, (3) biomimetic microfluidic and perfusion systems, (4) preclinical “in vitro” and “in vivo” trials, and (5) international bioethical and regulatory considerations. This classification allowed for the detection of innovation patterns, existing knowledge gaps, and the main trends in the research and development of bioartificial kidneys. The bibliographic search and organization process was carried out using Mendeley’s specialized software, ensuring the correct source systematization.

2.3. Technologies Analyzed

The first technology analyzed was the development of silicon nanoporous membranes. These membranes are originally adapted from microelectronics engineering. They have pores of controlled size between 5 and 10 nanometers, allowing a highly efficient, selective filtration that retains essential proteins and cells while eliminating metabolic toxins such as urea and creatinine (Groth et al., 2023; Fissell, 2023; Nagasubramanian, 2021). Together with their high permeability, low propensity to bio-incrustation, and excellent blood compatibility, this feature positions them as a central element in implantable renal therapy devices (De Boer et al., 2021).

The second technology discussed is the development of cellular bioreactors. Recent research has shown the possibility of growing proximal tubule cells in the nephron in three-dimensional environments that reproduce hydrodynamic conditions similar to the human nephron. These cells can perform essential functions of active reabsorption of solutes such as sodium, glucose, amino acids, and bicarbonate (Huang et al., 2024; Ramada et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2023).

In addition, the use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and pluripotent induced cells (iPSCs) has been explored as alternative cell sources to allow device customization according to patient immune profile, which could significantly reduce the need for immunosuppression (Gupta & Mandal, 2021; Kim et al., 2023; Chui et al., 2020).

The third technology is the design of integrated microfluidic systems known as “kidney-on-a-chip”. These devices recreate the blood and tubular flows characteristic of the human kidney through microstructured channels, allowing interaction between fluids and cells. This limits cellular hypoxia that affects cell viability in implantable devices (Nguyen et al., 2023).

The fourth technology evaluates “in vivo” preclinical models in rodents, pigs, and non-human primates. These animal models have enabled the validation of key parameters such as creatinine clearance, urea concentration, stability of acid-base balance, and systemic inflammatory response to the implantation of bioartificial devices (Huang et al., 2024; Ramada et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2023). Preclinical results have been critical in supporting the functional viability of implantable kidneys, although human clinical trials are still required to confirm their long-term efficacy and safety.

2.4. Regulatory and Ethical Aspects

The regulatory frameworks applicable to highly complex medical devices were explored. Particular attention was given to the guidelines of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 2020; Darrow et al., 2021), the European Medicines Agency (EMA, 2021), and international standards ISO, specifically those concerning class III implantable devices. These regulations set strict requirements for safety, biocompatibility, good manufacturing practice (GMP), and progressive clinical evaluation. In the ethical field, the challenges associated with the use of human cells in implantable devices, the risks inherent in the genetic modification of cell lines, equity in access to these advanced technologies, and the sociocultural factors that will influence public acceptance of bioartificial organs (Gupta & Mandal, 2021; Bunnik et al., 2022). These aspects highlight the need for an integrated approach where technical advances are accompanied by robust bioethical considerations and updated regulatory frameworks.

3. Results

Technological advances in developing implantable artificial kidneys have yielded promising results at both experimental and preclinical levels. Several studies have demonstrated the functional and structural viability of key components of these devices and their potential to replicate critical human kidney functions in a continuous and autonomous manner.

3.1. Filtration Efficiency in Nanoporous Membranes

Nanoporous silicon membranes have shown a highly selective ability in the ultrafiltration of uremic toxins, such as creatinine and urea, without compromising the retention of essential proteins (Fissell, 2023; Nagasubramanian, 2021). They showed that these membranes can achieve filtration rates comparable to the human renal glomerulus. It has also been shown that these membranes have a low rate of biofouling, which prolongs their service life and reduces the risk of clogging (Fissell, 2023; Nagasubramanian, 2021; Nalesso et al., 2024).

3.2. Maintenance of Cell Viability in Bioreactors

Bioreactors designed to house proximal renal tubule cells have maintained cell viability and functionality for extended periods in controlled environments (Huang et al., 2024; Ramada et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2023). Their preclinical studies reported that these cells can perform reabsorption functions of sodium, potassium, bicarbonate, and glucose, effectively reproducing the tubular processes that contribute to homeostatic equilibrium. In addition, the use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and pluripotent induced cells (iPSCs) has expanded the availability of cellular sources, allowing a personalized adaptation of the device according to the immunological needs of the patient (Gupta & Mandal, 2021).

3.3. Integration and Performance of Microfluidic Systems

Functional tests of integrated microfluidic systems, known as “kidney-on-a-chip”, have confirmed their ability to emulate pressure and flow gradients found in nephrons (Wieringa et al., 2025). This allows efficient interaction between the filtration and reabsorption compartments, minimizing cellular hypoxia and promoting higher metabolic efficiency (Ramada et al., 2023).

3.4. Preclinical Evaluation in Animal Models

Implantable devices have maintained critical renal functions for several days without causing severe inflammatory responses or signs of rejection in preclinical studies conducted on porcine and rodent models. In particular, blood creatinine and urea levels decreased significantly after bioartificial kidney implantation and a stable acid-base balance was maintained (Huang et al., 2024; Ramada et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2023). These results suggest that functional integration of the device is possible in the short term. The devices showed mechanical compatibility with the patient’s anatomical environment, resisting systemic blood pressure without structural failure or fluid leakage.

One of the main technical challenges remains the adequate vascularization of the implantable device. Without an efficient supply of oxygen and nutrients, functional renal cells housed in the bioreactor are at risk of hypoxia and loss of viability. To address this challenge, strategies such as the incorporation of microstructure vascularized scaffolds that favor the formation of capillary networks and the controlled release of angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF have been explored (vascular endothelial growth factor), with encouraging results in preclinical models (Min et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2023). These approaches seek not only to improve the blood perfusion of the device but also to optimize the cellular metabolic exchange, thus extending its functionality and durability in the long term.

3.5. Potential for Personalization and Reduction of Immunosuppression

An important development has been using autologous cells and the device’s modular design, which could drastically reduce the need for post-operative immunosuppressants. This is an advantage over transplantation as it improves quality of life, reducing long-term complications (Bunnik et al., 2022).

This study shows that the technologies related to the artificial kidney implant concept are viable. Despite being in experimental phases, the results’ robustness justifies continuous investment in their development and clinical implementation.

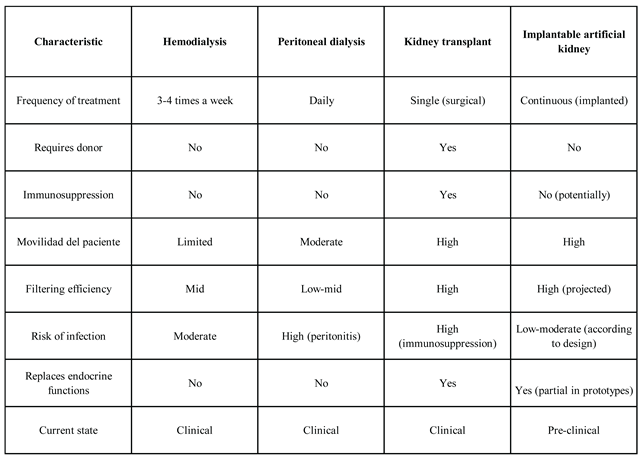

3.6. Comparison of Technologies in Renal Replacement Therapy

Treatment choice for CKD patients depends on multiple clinical, social, and economic factors. Traditionally, the main options have been hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation. With the option of having an artificial kidney, it is important to know the benefits and challenges of available treatments in order to determine which one is most appropriate for the patient.

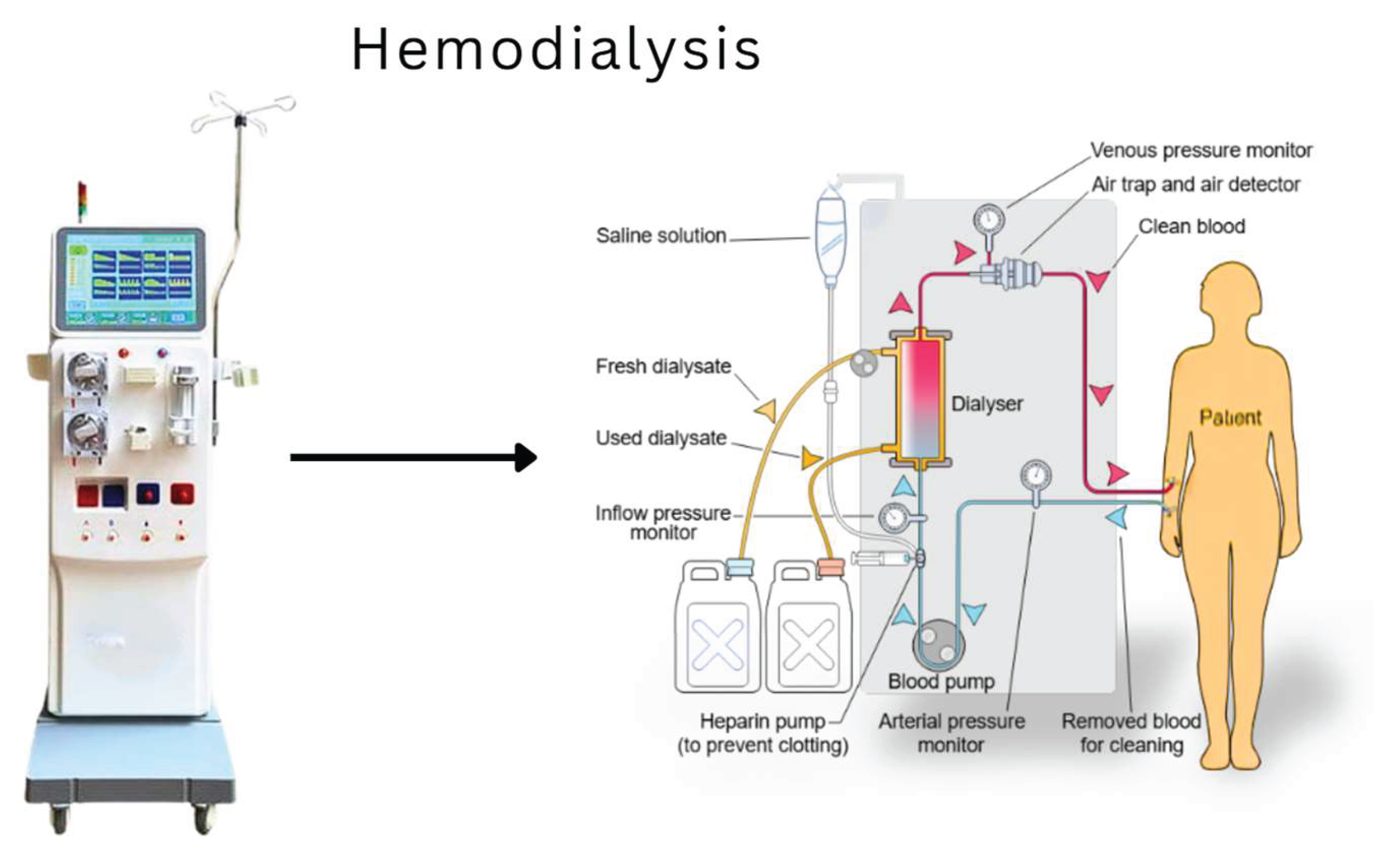

Hemodialysis

Hemodialysis remains the most common treatment worldwide. This extracorporeal procedure involves connecting the patient to a machine that filters their blood through a semi-permeable membrane for several sessions, typically three times a week. Although effective in removing toxins, it does not replace complete endocrine or homeostatic functions and impacts quality of life, which may include fatigue, dietary restrictions, and extended treatment time (Cockwell & Fisher, 2020).

Figure 1 illustrates the hemodialysis process and highlights its main components.

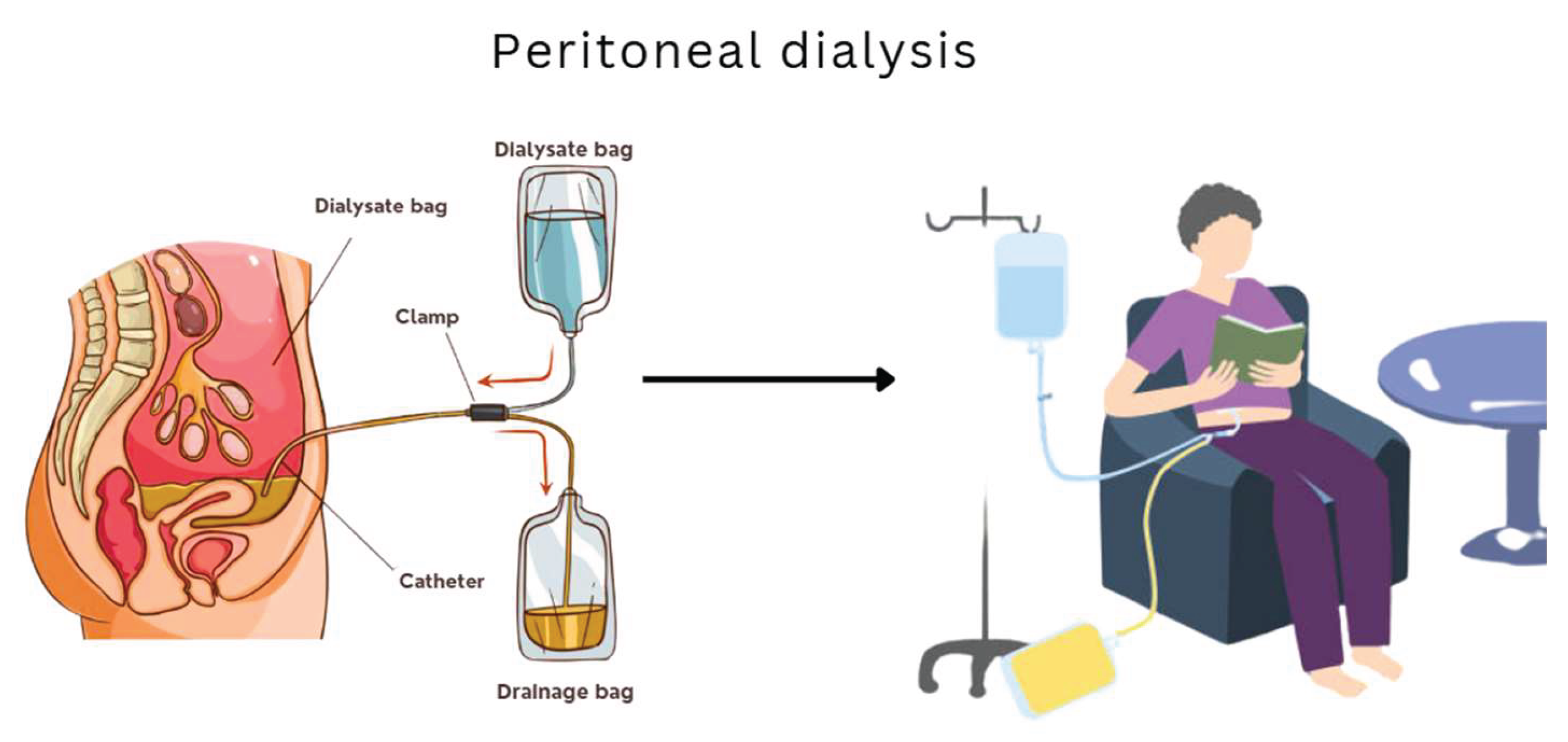

Peritoneal Dialysis

This method uses the patient’s peritoneal membrane as a filter. It is less restrictive than hemodialysis in terms of mobility and can be administered at home, but it carries a higher risk of infections such as peritonitis (Dzekova-Vidimliski et al., 2021). Additionally, outcomes tend to be less effective in advanced stages of kidney failure and require constant monitoring.

Figure 2 illustrates the peritoneal dialysis process and highlights its key features.

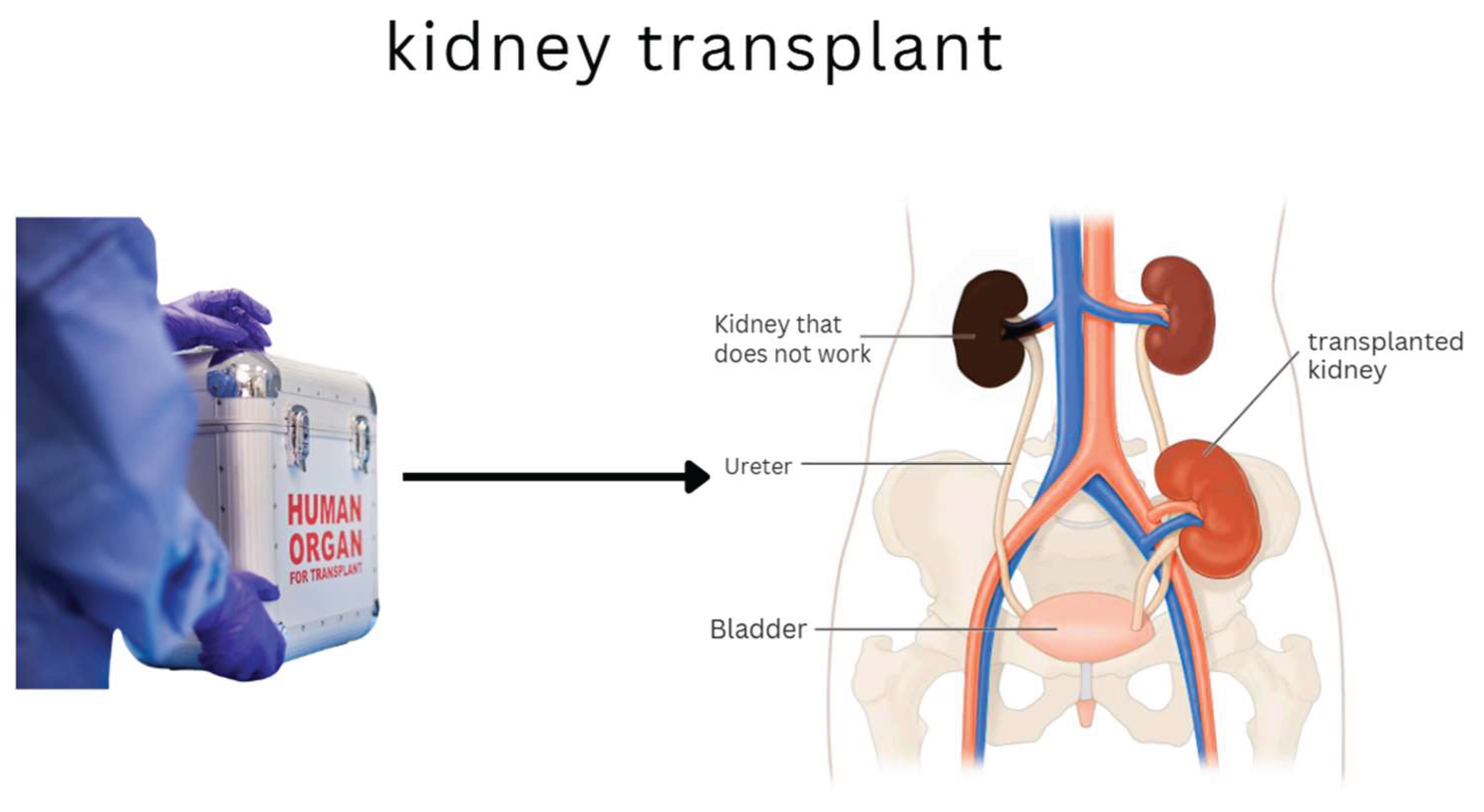

Kidney Transplant

Considered the gold standard, transplantation offers the best hope for long-term survival and full functional recovery. However, it critically depends on donor availability, involves surgical risks, and requires lifelong immunosuppression, which increases susceptibility to infections and certain cancers (Saran et al., 2020).

Figure 3 illustrates the transplantation process and highlights its key components.

Implantable Artificial Kidney

The innovation of the implantable artificial kidney seeks to overcome the above challenges by offering a stand-alone device capable of performing filtering and endocrine functions in situ. This technology, still in the preclinical phase, aims at a continuous solution without the need for external connection or prolonged immunosuppression, through the use of autologous cells and integrated microfluidic systems (Fissell, 2023; Nagasubramanian, 2021; Huang et al., 2024; Wieringa et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2023). Although its projected benefits are significant, it still faces technical challenges such as vascularization, immunological integration, and large-scale clinical validation. A visual representation of this device and its components is provided in

Figure 4, offering further insight into its design and intended function.

3.7. Comparison

The following comparison in

Table 1 highlights the transformative potential of the implantable artificial kidney. While it does not replace current clinical methods, its development offers an opportunity to redefine renal replacement therapy toward a more holistic, continuous, and personalized approach.

4. Discussion

There is a remarkable advance in developing an artificial implantable kidney, positioning this technology as an emerging alternative to traditional renal therapies. In particular, the ability of silicon nanoporous membranes to perform highly efficient selective filtration without inducing a significant immune response is a positive feature in terms of bioartificial compatibility and functionality (Fissell, 2023; Nagasubramanian, 2021). Unlike filters used in conventional hemodialysis, these membranes have been designed with nanometric precision, allowing them to mimic the selective properties of the human renal glomerulus more closely.

Maintaining the viability and functionality of renal cells in three-dimensional bioreactors is a fundamental pillar in reproducing tubular function, one of the most complex in the kidney. Preclinical evidence, such as that presented by Kim et al., indicates that these systems allow active reabsorption of essential solutes using cells derived from the patient, thus reducing the risk of immunological rejection. This therapeutic personalization opens the door to precision medicine in treating chronic kidney failure (Kim et al., 2023).

Developing “kidney-on-a-chip” microfluidic systems has made it possible to accurately emulate the physiological conditions of the nephron’s pressure, flow, and osmotic gradients. According to the European Commission, these advances have been key in optimizing the intracellular environment and reducing the oxidative stress of implanted cells (Rayat et al., 2024). This biomimicry of the natural renal environment improves the device’s performance and extends its functional durability, which is critical for long-term applications.

Regarding “in vivo” validation, animal model trials showed a significant reduction in blood creatinine and urea levels after the device was implanted and stability at acid-to-base. This provides evidence that renal function can be partially restored by artificial means (Huang et al., 2024; Ramada et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2023). While these models do not yet fully reflect human physiological complexity, they provide a solid basis for future clinical trials.

In addition, the device’s modular approach and the use of advanced biocompatible materials allow for more efficient anatomical and functional integration, minimizing the use of chronic immunosuppressants, one of the main challenges in kidney transplantation (Bunnik et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2025). This development is particularly relevant considering the adverse effects of prolonged immunosuppression, such as opportunistic infections, neoplasms, and metabolic deterioration.

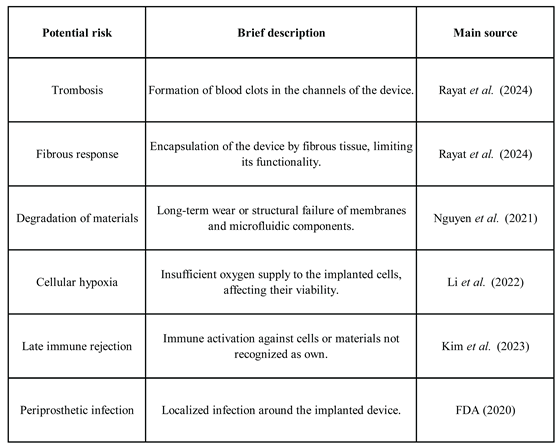

However, despite these advances, it is important to recognize the challenges of using artificial kidneys. Proper vascularization of the device and sustained production of functional urine remain unresolved technical problems. Likewise, standardizing protocols for incorporating human cells, bioethical validation, and obtaining international regulatory approval requires continuous multidisciplinary coordination (FDA, 2020; EMA, 2021; Darrow et al., 2021).

Socially and ethically, equitable access to these technologies could become a new point of inequality in health systems. As Gupta & Mandal pointed out, public acceptance of artificial organs depends not only on their effectiveness but also on the transparency of their development and the legal framework governing their use. This highlights the need to foster an integral bioethical culture that considers sociocultural diversity, equity in access, and economic sustainability of these solutions (Gupta & Mandal, 2021).

The results of this research consolidate the scientific and technical feasibility of the implantable artificial kidney while evidencing the need to continue strengthening partnerships between science, industry, medicine, and public policies. Its implementation could revolutionize the care of chronic renal failure, replacing palliative strategies with restorative solutions that significantly improve patient’s quality of life.

Table 2 presents a summary of the main risks associated with the development and clinical implementation of implantable artificial kidneys.

5. Future Perspectives and Emerging Innovations

Although the implantable artificial kidney is in the preclinical phase, emerging technological advances allow us to glimpse a promising future for its clinical implementation and functional evolution. One of the most relevant developments is the integration of intelligent sensors and artificial intelligence (AI) platforms (Bespalov & Selishchev, 2021). These components enable continuous monitoring of physiological parameters such as perfusion pressure, glomerular filtration rate, and electrolyte levels, dynamically adjusting the device’s performance to maintain real-time homeostasis (Nguyen et al., 2023).

Another emerging breakthrough in the development of implantable artificial kidneys is the use of custom 3D-printed bioreactors. Thanks to three-dimensional bio-printing techniques, it has been possible to produce tubular structures that precisely imitate the nephron architecture, favoring the functionality and anatomical integration of the device. This approach aligns with the principles of tissue engineering, which combines cells, biomaterials, and advanced design strategies to fabricate functional biological organs using custom 3D platforms (Rondón et al., 2025; Torabinavid et al., 2025). In recent preclinical models, these 3D bioreactors have shown significant improvement in cell viability, internal vascularization, and metabolic efficiency compared to traditional devices (Min et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2023).

Figure 5 highlights these emerging innovations, illustrating how smart technologies and bioprinting may shape the next generation of implantable artificial kidneys.

Another promising development is immunoprotected microcapsules, developed from semi-permeable polymeric materials that encapsulate the bioreactor’s functional renal cells. These capsules exchange nutrients and metabolic products without activating an immune response, eliminating or significantly reducing the need for pharmacological immunosuppression (Ibi & Nishinakamura, 2023).

In addition, global initiatives such as the US Department of Health and Human Services KidneyX project or the European Union’s Horizon Europe program are stimulating interdisciplinary research by funding the development of portable, miniaturized, and autonomous technologies for renal therapy (KidneyX, 2023; Bespalov & Selishchev, 2021; Wieringa et al., 2025; Ramada et al., 2023). These platforms promote the design of devices that replicate renal functions and integrate with remote monitoring tools, expanding patient access in resource-limited settings.

To further progress, it is estimated that the first human clinical trials for implantable artificial kidneys could be initiated in the next 3-5 years, driven by successful preclinical phases and approval of preliminary regulatory protocols (Bespalov & Selishchev, 2021). These trials will be critical to assessing long-term functional efficacy and biocompatibility, immunological integration, and durability of materials under human physiological conditions (Lentine et al., 2021; De Boer et al., 2021).

The trials should also address safety in terms of risks such as thrombosis, fibrosis, and local inflammatory responses, aspects that have so far only been studied in animal models (Kim et al., 2023; Ibi & Nishinakamura, 2023). The success of these early-stage studies will be a critical prerequisite for moving toward widespread implementation and real clinical access to these innovative devices.

After this analysis, emerging innovations suggest that the future implantable artificial kidney will not only be a functional substitute but also an advanced, intelligent, adaptable, and personalized therapeutic platform able to radically transform the current approach to renal replacement therapy.

6. Conclusion

Kidney failure is a medical condition that can lead to death. Traditional treatments such as hemodialysis and kidney transplantation have saved lives; however, their effectiveness and sustainability present challenges. Therefore, the development of an effective and sustainable implantable artificial kidney emerges as a potentially revolutionary solution within biomedical engineering and regenerative medicine.

This study has shown that several technologies, such as nanopore silicon membranes, functional renal cell bioreactors, precision microfluidics, and physiological sensors, can be used in real-time. They offer a realistic possibility of replacing the kidney’s filter function with more complex functions such as selective solute reabsorption, hormone regulation, and internal environment homeostasis.

Some achievements in prototype design have demonstrated viability in preclinical animal models. These devices have succeeded in purifying toxins with an efficiency close to the physiological one, maintaining cell viability in artificial environments, and reducing adverse immunological responses. Ongoing research in projects such as KIDNEW, funded by the European Commission, or initiatives led by the University of California at San Francisco demonstrate the possibility of having these artificial kidneys.

However, challenges remain, such as adequate vascularization of the device, durability of implantable materials, long-term immunological integration, and sustained urine production. Ethical dilemmas arise over equitable access to these technologies, unbiased clinical validation, and social acceptance of bioartificial devices, underlining the importance of a multidisciplinary and inclusive approach.

Developing an implantable artificial kidney is a medical necessity embodying a convergence of science, technology, ethics, and public health policy. Its successful implementation could redefine the therapeutic paradigm of kidney disease, reducing organ bank dependence, improving patients’ quality of life, and decreasing the economic burden of chronic treatments.

Based on this study, the path to clinical implementation of implantable artificial kidneys is challenging but promising. Given that kidney failure can be fatal, continued development until a successful and accessible solution is achieved is justified. Continued collaboration between scientists, engineers, doctors, regulators, and civil society will be key to overcoming current obstacles and transforming this technological innovation into a tangible medical reality. The future of renal therapy may be to change from palliative to restorative, thus offering a better quality of life for these patients.

Funding

This research was funded by Biomedical Engineering Department, Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico, PR 00918 USA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abramyan, S.; Hanlon, M. Kidney transplantation; In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, 2023; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567755/.

- Bespalov, V. A.; Selishchev, S. V. Implantable Artificial Kidney: A Puzzle. Biomedical Engineering 2021, 55, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunnik, E. M.; De Jongh, D.; Massey, E. Ethics of early clinical trials of Bio-Artificial Organs. Transplant International 2022, 35, 10621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chengdu Wesley Bioscience Technology Co; Ltd. Máquina de hemodiálisis con hemodiafiltración W-T6008S. MedicalExpo. 2025. Available online: https://www.medicalexpo.es/prod/chengdu-wesley-bioscience-technology-co-ltd/product-95761-1054856.html.

- Chui, B. W.; Wright, N. J.; Ly, J.; Maginnis, D. A.; Haniff, T. M.; Blaha, C.; Roy, S. A scalable, hierarchical rib design for larger-area, higher-porosity nanoporous membranes for the implantable bio-artificial kidney. Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems 2020, 29(5), 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockwell, P.; Fisher, L. A. The global burden of chronic kidney disease. The Lancet 2020, 395(10225), 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrow, J. J.; Avorn, J.; Kesselheim, A. S. FDA regulation and approval of medical devices: 1976-2020. Jama 2021, 326(5), 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, I. H.; Alpers, C. E.; Azeloglu, E. U.; Balis, U. G.; Barasch, J. M.; Barisoni, L.; Tublin, M. Rationale and design of the kidney precision medicine project. Kidney international 2021, 99(3), 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzekova-Vidimliski, P.; Nikolov, I. G.; Gjorgjievski, N.; Selim, G.; Trajceska, L.; Stojanoska, A.; Stojkovski, L. Peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis: Rate, clinical outcomes and patient survival. prilozi 2021, 42(3), 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency; EMA. Guideline on quality, non-clinical and clinical requirements for investigational advanced therapy medicinal products in clinical trials (EMA/CAT/852292/2018 Rev.1). 2021. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/guideline-quality-non-clinical-clinical-requirements-investigational-advanced-therapy-medicinal-products-clinical-trials-scientific-guideline.

- FDA. Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff: Class III Medical Devices. US Food and Drug Administration. 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/overview-device-regulation/classify-your-medical-device.

- Fissell, W. H., IV. Wearable and Implantable Renal Replacement Therapy. In Handbook of Dialysis Therapy; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, T.; Stegmayr, B. G.; Ash, S. R.; Kuchinka, J.; Wieringa, F. P.; Fissell, W. H.; Roy, S. Wearable and implantable artificial kidney devices for end-stage kidney disease treatment: current status and review. Artificial Organs 2023, 47(4), 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Mandal, B. B. Tissue-engineered vascular grafts: emerging trends and technologies. Advanced Functional Materials 2021, 31(33), 2100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HealthCommunities Provider Services. Peritoneal dialysis. n.d. Available online: https://www.healthcommunitiesproviderservices.com/patient-education/peritoneal-dialysis/ (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Huang, W.; Chen, Y. Y.; He, F. F.; Zhang, C. Revolutionizing nephrology research: expanding horizons with kidney-on-a-chip and beyond. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 2024, 12, 1373386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibi, Y.; Nishinakamura, R. Kidney bioengineering for transplantation. Transplantation 2023, 107(9), 1883–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IHME. Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. 2020. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

- Khan, M. A.; Hanna, A.; Sridhara, S.; Chaudhari, H.; Me, H. M.; Attieh, R. M.; Abu Jawdeh, B. G. Maintenance Immunosuppression in Kidney Transplantation: A Review of the Current Status and Future Directions. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2025, 14(6), 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KidneyX. iBAK–Implantable Bio-Artificial Kidney for Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy. 2023. Available online: https://www.kidneyx.org.

- Kim, E. J.; Chen, C.; Gologorsky, R.; Santandreu, A.; Torres, A.; Wright, N.; Roy, S. Feasibility of an implantable bioreactor for renal cell therapy using silicon nanopore membranes. Nature Communications 2023, 14(1), 4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentine, K. L.; Pastan, S.; Mohan, S.; Reese, P. P.; Leichtman, A.; Delmonico, F. L.; Axelrod, D. A. A roadmap for innovation to advance transplant access and outcomes: a position statement from the National Kidney Foundation. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2021, 78(3), 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hui, J.; Yang, P.; Mao, H. Microfluidic organ-on-a-chip system for disease modeling and drug development. Biosensors 2022, 12(6), 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospitals, Manipal. The role of peritoneal dialysis in chronic kidney disease treatment. 27 February 2023. Available online: https://www.manipalhospitals.com/hebbal/blog/the-role-of-peritoneal-dialysis-in-chronic-kidney-disease-treatment/.

- Min, S.; Cleveland, D.; Ko, I. K.; Kim, J. H.; Yang, H. J.; Atala, A.; Yoo, J. J. Accelerating neovascularization and kidney tissue formation with a 3D vascular scaffold capturing native vascular structure. Acta Biomaterialia 2021, 124, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monardo, P.; Lacquaniti, A.; Campo, S.; Bucca, M.; Casuscelli di Tocco, T.; Rovito, S.; Santoro, A. Updates on hemodialysis techniques with a common denominator: The personalization of the dialytic therapy. In Seminars in dialysis; May 2021; Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasubramanian, S. The future of the artificial kidney. Indian Journal of Urology 2021, 37(4), 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalesso, F.; Garzotto, F.; Cattarin, L.; Bettin, E.; Cacciapuoti, M.; Silvestre, C.; Calò, L. A. The Future for End-Stage Kidney Disease Treatment: Implantable Bioartificial Kidney Challenge. Applied Sciences 2024, 14(2), 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NIDDK. Kidney transplant. 2018. Available online: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/kidney-disease/kidney-failure/kidney-transplant (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- NephCure, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Hemodialysis. 2024. Available online: https://nephcure.org/intro-to-rkd/end-stage-kidney-disease/dialysis/hemodialysis/ (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Nguyen, V. V.; Gkouzioti, V.; Maass, C.; Verhaar, M. C.; Vernooij, R. W.; van Balkom, B. W. A systematic review of kidney-on-a-chip-based models to study human renal (patho-) physiology. Disease Models & Mechanisms 2023, 16(6), dmm050113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramada, D. L.; de Vries, J.; Vollenbroek, J.; Noor, N.; Ter Beek, O.; Mihăilă, S. M.; Stamatialis, D. Portable, wearable and implantable artificial kidney systems: needs, opportunities and challenges. Nature Reviews Nephrology 2023, 19(8), 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayat Pisheh, H.; Haghdel, M.; Jahangir, M.; Hoseinian, M. S.; Rostami Yasuj, S.; Sarhadi Roodbari, A. Effective and new technologies in kidney tissue engineering. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2024, 12, 1476510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondón, J.; Sánchez-Martínez, V. M.; Lugo, C.; Gonzalez-Lizardo, A. Tissue engineering: Advancements, challenges, and future perspectives. Revista Ciencia e Ingeniería 2025, 46(1), 19–28. Available online: http://erevistas.saber.ula.ve/index.php/cienciaeingenieria/article/view/20607/21921932297.

- Rondón, J.; Vázquez, J.; Lugo, C. Biomaterials are used in tissue engineering to manufacture scaffolds. Ciencia e Ingeniería 2023, 44(3), 297–308. Available online: http://erevistas.saber.ula.ve/index.php/cienciaeingenieria/article/view/19221.

- Saran, R.; Robinson, B.; Abbott, K. C.; Bragg-Gresham, J.; Chen, X.; Gipson, D.; Shahinian, V. US renal data system 2019 annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2020, 75(1), A6–A7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabinavid, P.; Khosropanah, M. H.; Azimzadeh, A.; Kajbafzadeh, A. M. Current strategies on kidney regeneration using tissue engineering approaches: a systematic review. BMC nephrology 2025, 26(1), 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieringa, F. P.; Suran, S.; Søndergaard, H.; Ash, S.; Cummins, C.; Chaudhuri, A. R.; Vollenbroek, J. The Future of Technology-Based Kidney Replacement Therapies: An Update on Portable, Wearable, and Implantable Artificial Kidneys. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).