Submitted:

23 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Feature Engineering

2.3. Training Strategy of Transfer Learning Model

2.4. Virtual Structure Proposed

2.5. Descripter Calculated

2.6. Interpretable Model

2.7. SHAP Analysis

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Performance Comparison of Different Neural Network Frameworks as Pre-trained Models in Transfer Learning

3.2. Necessity and Technical Advantages of Transfer Learning

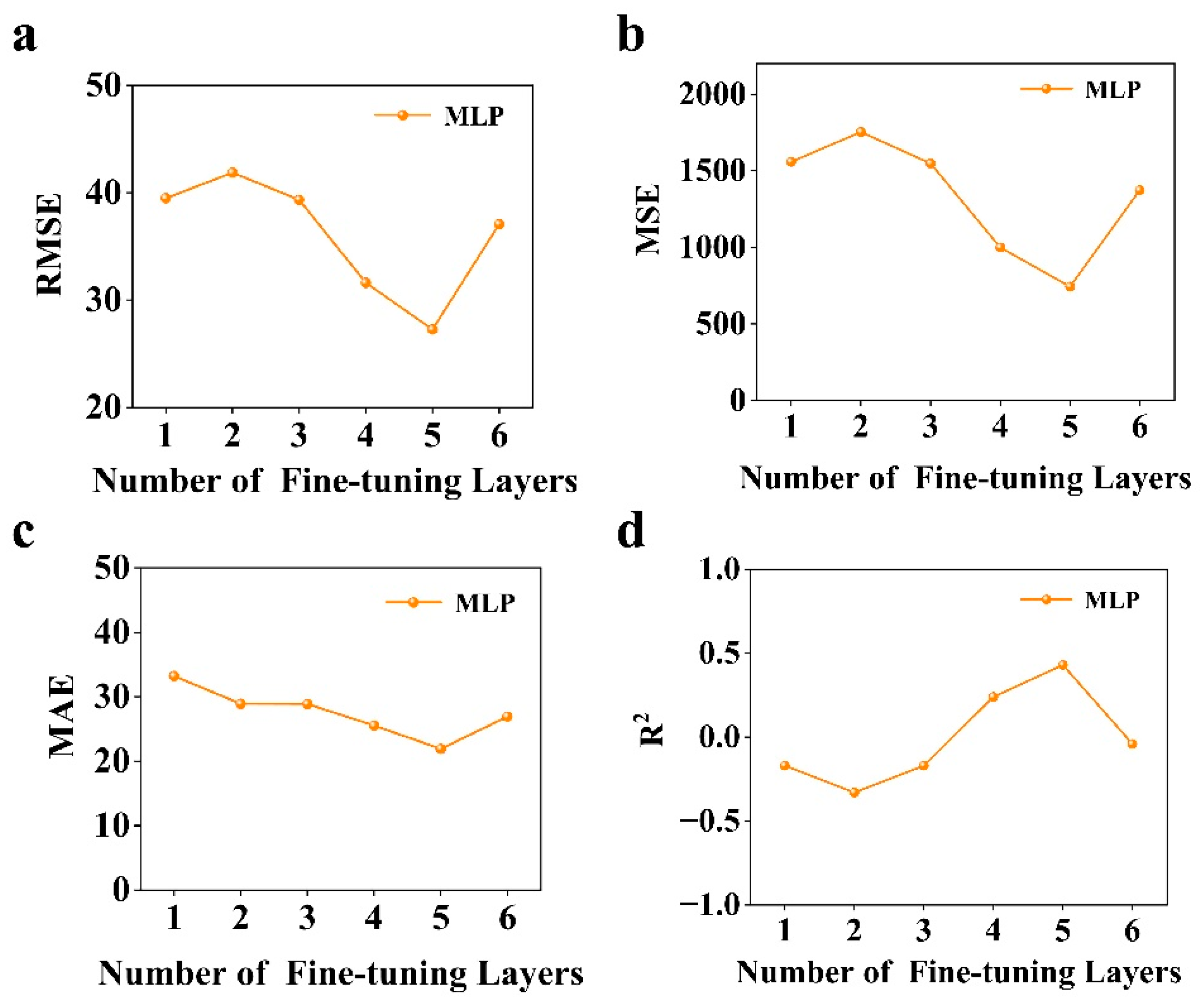

3.3. Optimizing Transfer Learning Performance Through Layer-Wise Fine-Tuning in MLP Architectures

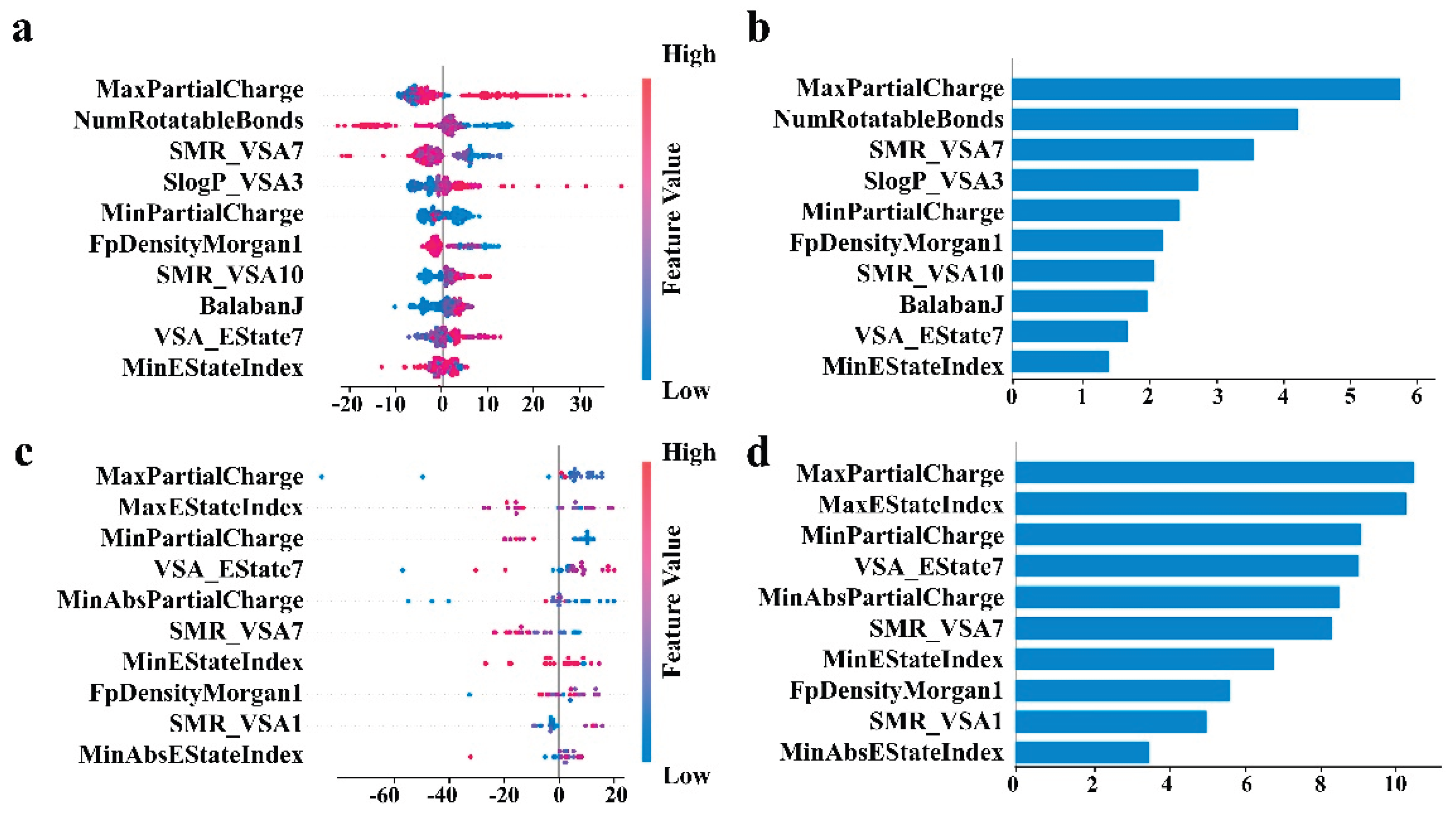

3.4. Feature Interpretability Analysis

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, X.; Xie, Z.; Liu, L.; Chen, W. High-velocity impact and post-impact fatigue response of Bismaleimide resin composite laminates. European Journal of Mechanics - A/Solids 2025, 112, 105655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, F.; Wang, Y.; Wei, W.; Feng, Y. Polymer-Based Electronic Packaging Molding Compounds, Specifically Thermal Performance Improvement: An Overview. ACS Applied Polymer Materials 2024, 6, 14948–14969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, P.; Ma, S.; Zhu, G.; Wu, L. Synthesis and thermal properties of novel bismaleimides containing cardo and oxazine structures and the thermal transition behaviors of their polymer structures. Thermochimica Acta 2023, 719, 179401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Sun, Q.; Guo, J.; Wang, C. High-Performance Bismaleimide Resin with an Ultralow Coefficient of Thermal Expansion and High Thermostability. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 1808–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melissaris, A. P.; Mikroyannidis, J. A. Bismaleimides chain-extended by imidized benzophenone tetracarboxylic dianhydride and their polymerization to high temperature matrix resins. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry 1988, 26, 1165–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenier-Loustalot, M.-F.; Da Cunha, L. Sterically hindered bismaleimide monomer: Molten state reactivity and kinetics of polymerization. European Polymer Journal 1998, 34, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graser, J.; Kauwe, S. K.; Sparks, T. D. Machine Learning and Energy Minimization Approaches for Crystal Structure Predictions: A Review and New Horizons. Chemistry of Materials 2018, 30, 3601–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radue, M. S.; Varshney, V.; Baur, J. W.; Roy, A. K.; Odegard, G. M. Molecular Modeling of Cross-Linked Polymers with Complex Cure Pathways: A Case Study of Bismaleimide Resins. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 1830–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Gee, R. H.; Boyd, R. H. Glass Transition Temperatures of Polymers from Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Macromolecules 1994, 27, 7781–7784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, J.; Paul, W.; Varnik, F.; Binder, K. Cooling rate dependence of the glass transition temperature of polymer melts: Molecular dynamics study. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2002, 117, 7364–7372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, S.; Chai, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhu, W.; Li, L.; Li, B. A.-O. Prediction and Interpretability Study of the Glass Transition Temperature of Polyimide Based on Machine Learning with Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (T(g)-QSPR). (1520-5207 (Electronic)). From 2024 Sep 12.

- Babbar, A.; Ragunathan, S.; Mitra, D.; Dutta, A.; Patra, T. K. Explainability and extrapolation of machine learning models for predicting the glass transition temperature of polymers. Journal of Polymer Science 2024, 62, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Cho, K. Conditional Molecular Design with Deep Generative Models. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2019, 59, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuer, K.; Renz, P.; Unterthiner, T.; Hochreiter, S.; Klambauer, G. A.-O. Fréchet ChemNet Distance: A Metric for Generative Models for Molecules in Drug Discovery. (1549-960X (Electronic)). From 2018 Sep 24.

- Arús-Pous, J. A.-O.; Blaschke, T.; Ulander, S.; Reymond, J. L.; Chen, H.; Engkvist, O. Exploring the GDB-13 chemical space using deep generative models. (1758-2946 (Print)). From 2019 Mar 12.

- Tao, L.; Varshney, V.; Li, Y. Benchmarking Machine Learning Models for Polymer Informatics: An Example of Glass Transition Temperature. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2021, 61, 5395–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Yu, M.; Han, J.-P.; Jiang, J.; Jia, Q.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Z.-H.; Yan, F.; Zhou, Y.-N. Leveraging data-driven strategy for accelerating the discovery of polyesters with targeted glass transition temperatures. AIChE Journal 2024, 70, e18409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, L. Artificial neural network prediction of glass transition temperature of fluorine-containing polybenzoxazoles. Journal of Materials Science 2009, 44, 3156–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, F.; Ferres, J. L.; Buonassisi, T.; Butler, K. T. Interpretable and Explainable Machine Learning for Materials Science and Chemistry. Accounts of Materials Research 2022, 3, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Bavarian, M. A Machine Learning Framework for Predicting the Glass Transition Temperature of Homopolymers. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2022, 61, 12690–12698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilania, G.; Iverson, C. N.; Lookman, T.; Marrone, B. L. Machine-Learning-Based Predictive Modeling of Glass Transition Temperatures: A Case of Polyhydroxyalkanoate Homopolymers and Copolymers. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2019, 59, 5013–5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcobaça, E.; Mastelini, S. M.; Botari, T.; Pimentel, B. A.; Cassar, D. R.; de Carvalho, A. C. P. d. L. F.; Zanotto, E. D. Explainable Machine Learning Algorithms For Predicting Glass Transition Temperatures. Acta Materialia 2020, 188, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King-Smith, E. Transfer learning for a foundational chemistry model. Chemical Science 2024, 15, 5143–5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, H.; Liu, C.; Wu, S.; Koyama, Y.; Ju, S.; Shiomi, J.; Morikawa, J.; Yoshida, R. Predicting Materials Properties with Little Data Using Shotgun Transfer Learning. ACS Central Science 2019, 5, 1717–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wu, D. Predicting stress–strain curves using transfer learning: Knowledge transfer across polymer composites. Materials & Design 2022, 218, 110700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi-Khasragh, E.; González, C.; Haranczyk, M. Toward diverse polymer property prediction using transfer learning. Computational Materials Science 2024, 244, 113206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sztandera, L.; Cartwright, H. M. A neural network approach to prediction of glass transition temperature of polymers: Research Articles. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2008, 23, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, California, USA, San Francisco, California, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, S.; Kuwajima, I.; Hosoya, J.; Xu, Y.; Yamazaki, M. PoLyInfo: Polymer Database for Polymeric Materials Design. In 2011 International Conference on Emerging Intelligent Data and Web Technologies, 7-9 Sept. 2011, 2011; pp 22-29. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Xin, H.; Zhang, J. Property Prediction and Structural Feature Extraction of Polyimide Materials Based on Machine Learning. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2023, 63, 5473–5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Xia, Y.; Liu, L.; Yan, S.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Sheng, Y. Comparative study of the kinetic behaviors and properties of aromatic and aliphatic bismaleimides. Thermochimica Acta 2024, 737, 179768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Tang, J.; Ji, B.; Wu, N.; Liao, W.; Yin, C.; Bai, S.; Xing, S. Fluorinated polyetherimide as the modifier for synergistically enhancing the mechanical, thermal and dielectric properties of bismaleimide resin and its composites. Composites Communications 2024, 51, 102035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Liang, M.; Heng, Z.; Zou, H. Design of high-performance resin by tuning cross-linked network topology to improve CF/bismaleimide composite compressive properties. Composites Science and Technology 2023, 242, 110170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.-C.; Lee, J.-J.; Liu, Y.-L. Meldrum's acid-functionalized bismaleimide, polyaspartimide and their thermally crosslinked resins: Synthesis and properties. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2024, 202, 105988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Lei, F.; Wang, P.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; Yang, X. Hierarchical curing mechanism in epoxy/bismaleimide composites: Enhancing mechanical properties without compromising thermal stabilities. European Polymer Journal 2025, 222, 113604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, C.; Sun, M.; Zhang, X.; Derradji, M.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Zhao, M.; Song, C.; et al. Synthesis, curing kinetics and processability of a low melting point aliphatic silicon-containing bismaleimide. Materials Today Communications 2024, 41, 110845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Yuan, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Wan, L.; Huang, F. Bismaleimide resin modified by a propargyl substituted aromatic amine with ultrahigh glass transition temperature, thermomechanical stability and intrinsic flame retardancy. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2023, 193, 105740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, W.; Ye, W.; Chu, F.; Hu, W.; Song, L.; Hu, Y. Design of reactive linear polyphosphazene to improve the dielectric properties and fire safety of bismaleimide composites. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 482, 148867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yu, L.; Zhang, S.; Sun, X.; Qu, B.; Wang, R.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Gao, J.; et al. Synergistic strengthening and toughening of 3D printing photosensitive resin by bismaleimide and acrylic liquid-crystal resin. Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices 2023, 8, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Li, D.-s.; Jiang, L. Thermally stable and deformation-reversible eugenol-derived bismaleimide resin: Synthesis and structure-property relationships. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2022, 173, 105236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Yun, S.; Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; Zuo, X.; Miao, X.; Shi, X.; Qin, J.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, G. Highly heat-resistant and mechanically strong co-crosslinked polyimide/bismaleimide rigid foams with superior thermal insulation and flame resistance. Materials Today Physics 2023, 36, 101154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Liang, G.; Gu, A. A facile strategy and mechanism to achieve biobased bismaleimide resins with high thermal-resistance and strength through copolymerizing with unique propargyl ether-functionalized allyl compound. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2023, 186, 105570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Y.; Ji, Z.; Jia, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, F.; Liu, W. Additively manufacturing high-performance bismaleimide architectures with ultraviolet-assisted direct ink writing. Materials & Design 2019, 180, 107947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Ma, X.; Chen, P.; Zhou, L.; Ren, R.; Liu, S. New chain-extended bismaleimides with aryl-ether-imide and phthalide cardo skeleton (I): Synthesis, characterization and properties. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2018, 129, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Bao, Y.; Wei, W.; Fei, X.; Li, X.; Liu, X. Bismaleimide/Phenolic/Epoxy Ternary Resin System for Molding Compounds in High-Temperature Electronic Packaging Applications. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2022, 61, 4191–4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, L.; Yuan, L.; Liang, G.; Gu, A. Thermally resistant and strong remoldable triple-shape memory thermosets based on bismaleimide with transesterification. Journal of Materials Science 2021, 56, 3623–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Wu, F.; Wang, X.; Zhong, J.; Liu, X.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, D.; Ning, Z. Strategy to achieve low-dielectric-constant for benzoxazine-phthalonitriles: introduction of 2,2'-bis[4-(4-Maleimidephen-oxy)phenyl)]propane by in-situ polymerization. Journal of Polymer Research 2024, 31, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Zhang, Y.; He, X. Design of acetylene-modified bio-based tri-functional benzoxazine and its copolymerization with bismaleimide for performance enhancement. Polymer Bulletin 2023, 80, 12065–12077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Zhang, K. Strategies for improving the performance of diallyl bisphenol A-based benzoxazine resin: Chemical modification via acetylene and physical blending with bismaleimide. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2021, 165, 104958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Zhang, Y.-l.; Yang, X.; Pan, L.-j.; Dai, Z.-y.; Xue, M.-z.; Liu, Y.-g.; Wang, W. Synthesis and characterization of asymmetric bismaleimide oligomers with improved processability and thermal/mechanical properties. Polymer Engineering & Science 2019, 59, 2265–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Qiao, Y.; Li, N.; Hu, F.; Chen, Y.; Du, G.; Wang, J.; Jian, X. Toughened of bismaleimide resin with improved thermal properties using amino-terminated Poly(phthalazinone ether nitrile sulfone)s. Polymer 2020, 206, 122887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Zhang, P.; Song, Z.; Guo, F.; Hua, Z.; You, T.; Li, S.; Cui, C.; Liu, L. Preparation of eugenol-based flame retardant epoxy resin with an ultrahigh glass transition temperature via a dual-curing mechanism. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2025, 231, 111092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Luo, T. Evaluating Polymer Representations via Quantifying Structure–Property Relationships. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2019, 59, 3110–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weininger, D. SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences 1988, 28, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Ji, B.; Wu, N.; Liao, W.; Yin, C.; Bai, S.; Xing, S. The effect of substituent group in allyl benzoxazine on the thermal, mechanical and dielectric properties of modified bismaleimide. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2023, 191, 105673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Saravanamuthu, S. K. S.; Syed Mohammed, S. R.; Jeyaraj Pandian, D.; Chinnaswamy Thangavel, V. Low-temperature processable glass fiber reinforced aromatic diamine chain extended bismaleimide composites with improved mechanical properties. Polymer Composites 2022, 43, 6987–6997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Ding, L.; Li, W.; Ma, G.; Bai, H.; Li, L. Hyper-Cross-Linked Organic Microporous Polymers Based on Alternating Copolymerization of Bismaleimide. ACS Macro Letters 2016, 5, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerl, A. E.; and Kennard, R. W. Ridge Regression: Biased Estimation for Nonorthogonal Problems. Technometrics 1970, 12, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taunk, K.; De, S.; Verma, S.; Swetapadma, A. A Brief Review of Nearest Neighbor Algorithm for Learning and Classification. In 2019 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICCS), 15-17 May 2019, 2019; pp 1255-1260. [CrossRef]

- MacKay, D. J. C. Bayesian interpolation. Neural Comput. 1992, 4, 415–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkassky, V. The Nature Of Statistical Learning Theory~. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 1997, 8, 1564–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S. M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, California, USA; 2017.

- Iredale, R. J.; Ward, C.; Hamerton, I. Modern advances in bismaleimide resin technology: A 21st century perspective on the chemistry of addition polyimides. Progress in Polymer Science 2017, 69, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuka, K.; Nakao, S.; Hatanaka, Y. Toughening of bismaleimide and benzoxazine alloy with allyl group by incorporation of polyrotaxane. Polymer 2025, 320, 127979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, L.; Liang, G.; Gu, A. Achieving ultrahigh glass transition temperature, halogen-free and phosphorus-free intrinsic flame retardancy for bismaleimide resin through building network with diallyloxydiphenyldisulfide. Polymer 2020, 203, 122769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metrics | Data_1 Standalone | Data_2 Standalone | Transfer Learning (from Data_1 to Data_2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (°C) | 97.53 | 82.15 | 27.27 |

| MSE | 9512.74 | 6747.92 | 743.61 |

| MAE (°C) | 89.49 | 79.47 | 21.92 |

| R2 | -6.19 | -4.10 | 0.44 |

| Model | Dataset | RMSE (°C) | MSE | MAE (°C) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | Data_2 | 43.18 | 1864.35 | 36.42 | -0.81 |

| Data_3 | 17.32 | 299.97 | 12.27 | 0.62 | |

| Ridge | Data_2 | 37.39 | 1398.15 | 30.72 | -0.36 |

| Data_3 | 21.75 | 472.98 | 15.33 | 0.40 | |

| KNN | Data_2 | 64.09 | 4107.56 | 48.96 | -2.98 |

| Data_3 | 20.45 | 418.29 | 13.65 | 0.47 | |

| Bayesian | Data_2 | 37.39 | 1397.86 | 30.33 | -0.36 |

| Data_3 | 21.60 | 466.51 | 15.18 | 0.41 | |

| SVR | Data_2 | 37.02 | 1370.61 | 30.39 | -0.33 |

| Data_3 | 19.07 | 363.58 | 13.38 | 0.54 | |

| XGBoost | Data_2 | 48.35 | 2337.33 | 39.91 | -1.97 |

| Data_3 | 17.06 | 290.98 | 12.09 | 0.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).