1. Introduction

Despite decades of investment in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives, organizations continue to face persistent challenges in translating these efforts into measurable and sustainable change [

1,

2]. While representation has somewhat improved for some identities [

3,

4], particularly in recruitment outcomes and leadership pipelines [

5], inclusion remains a more elusive and complex goal [

6,

7,

8]. Many organizational efforts still rely on identity-specific interventions that target women, racially minoritized groups, LGBTQI+ individuals, or people with disabilities [

9]. While well-intentioned, such efforts often operate in silos, lack systemic integration, and risk marginalizing those whose experiences fall outside predefined categories. These frameworks also struggle to address the growing complexity of intersectionality and to support a shared, everyday experience of inclusion across all employees [

10].

The concept of inclusion itself is variably defined and inconsistently operationalized. Some definitions emphasize subjective belonging, while others focus on structural equity, representation, or psychological safety [

11]. This lack of theoretical coherence has impeded the development of scalable, evidence-based practices and meaningful metrics for inclusion. In response, an emerging body of scholarship calls for reframing inclusion as a universal human condition grounded not in identity categories but in the basic needs all individuals require to thrive within organizational systems [

1,

12,

13]. However, few models have articulated what those shared needs are, nor subjected such models to empirical validation.

The 8-Inclusion Needs of All People framework [

9,

14] was developed to address this gap. Drawing from behavioral science, organizational psychology, and intersectional lived experience research, the framework defines inclusion as the extent to which individuals have access to eight interdependent needs: Access, Space, Opportunity, Representation, Allowance, Language, Respect, and Support. Rather than conceptualizing inclusion as a feeling or an accommodation for specific groups, the model positions it as a shared set of conditions necessary for all people to fulfill their potential and succeed. It presents a human-centered alternative to fragmented or performative inclusion efforts and seeks to enable more coherent, systemic, and actionable strategies. Preliminary research consisted of two foundational studies: one that established the theoretical rationale for the model [

9], and another that qualitatively tested the resonance of the eight needs across people of diverse identities and intersectionalities [

14]. Findings from these earlier studies suggested that the needs were consistently relevant, regardless of participants’ demographic or intersectional identity. However, empirical testing through quantitative methods remained a critical next step to evaluate the scale’s structure, reliability, and practical utility.

The current paper presents the results of a two-sample cross-sectional validation study of the 8-Inclusion Needs of All People framework. It aims to test whether the framework functions as a reliable, psychometrically sound, and practically relevant model for understanding inclusion as a human-centered construct. Together, the two samples address the following hypotheses:

That individuals across diverse identity backgrounds will rate each of the eight inclusion needs as important to their success at work.

That the items representing the inclusion needs will form a reliable and psychometrically sound scale.

That the perceived importance of inclusion needs will predict key inclusion-related outcomes, such as feeling included and perceiving that others value difference.

In addition, the study explores whether perceived inclusion needs vary meaningfully based on identity group membership or the number of intersecting identities held, testing the framework’s foundational claim that inclusion needs are shared human requirements, not identity-specific preferences. The findings contribute to the ongoing conversation about how inclusion can be more systematically defined, measured, and applied within organizations.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper presents a dual-sample cross-sectional validation study designed to evaluate the empirical validity of the 8-Inclusion Needs of All People framework [

9]. The study aimed to test whether the inclusion needs proposed in the model are consistently experienced and considered important across individuals with diverse identity characteristics, and whether they function as a reliable, predictive, and psychometrically sound construct.

To enhance generalizability, data were collected from two independently sourced samples. The first sample included employees from a single organization, providing an initial, organization-specific test of the framework. The second sample was drawn from a broader, multi-organizational population. In the organizational sample, participants voluntarily completed a structured online survey. Of the 49 valid responses received, 46 participants completed all relevant items and were retained for analysis. In the broader sample, 115 valid responses were collected from individuals across sectors, industries, and geographies. Participants were recruited using a convenience sampling approach through online promotion. All participants completed the same survey, which included demographic questions and items aligned to the inclusion needs framework.

Respondents were invited to self-identify with any applicable identities across 27 categories reflecting common dimensions in DEI research (e.g., racial minority, LGBTQI+, disability, neurodivergence, chronic illness, caregiver status). Participants selected between 3 and 10 identities, with an average of 5.4 in the organizational sample and 4.8 in the broader sample, indicating high levels of intersectional identity.

The survey included 13 items measuring the perceived importance of specific inclusion needs, mapped to the eight domains of the 8-Inclusion Needs framework: Access, Space, Opportunity, Representation, Allowance, Language, Respect, and Support. Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) and framed in practical terms, such as “I need to feel physically safe at work to succeed” and “I need communication to be clear and respectful of all people to succeed.” Some needs were represented by multiple items to reflect sub-dimensions more accurately.

Participants also responded to three outcome items reflecting inclusion-related perceptions: (i) “I value and embrace difference”, (ii) “All the people I work with value and embrace difference”, and (iii) “I feel included in this organization”. These outcomes were used to assess the predictive utility of the inclusion needs construct.

The study adhered to established ethical principles for organizational research. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation, participation was voluntary, and no personal or identifying information was collected. Responses were anonymous and reported in aggregate form only. Participants were informed that the data would be used for research purposes and that findings would be de-identified. The design prioritized psychological safety, data protection, and the respectful inclusion of diverse perspectives. All protocols were aligned with the principles of beneficence, autonomy, and justice outlined in the Belmont Report [

15].

All analyses were conducted in the JupyterLab environment using Python, with the pandas, scikit-learn, and SciPy libraries. Responses were cleaned, and Likert scores were standardized for consistency across analyses. A composite Inclusion Needs Score was calculated for each participant by averaging their responses to the 13 inclusion needs items.

To evaluate the scale’s psychometric properties, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted for both samples. A unidimensional (single-component) model and a three-component model were explored to determine the scale’s latent structure. Scree plots and component loadings were reviewed to assess dimensionality, and Cronbach’s alpha was computed to evaluate internal consistency.

To examine the identity-independence of inclusion needs, three analytical strategies were applied across both datasets:

Group Comparisons – Independent sample t-tests assessed whether Inclusion Needs Scores differed significantly between identity groups (e.g., male vs. female).

Intersectionality Correlation – The number of identities selected (intersectionality count) was correlated with Inclusion Needs Scores to examine whether individuals with more complex identity profiles reported stronger inclusion needs.

Cluster Analysis and Identity Composition – K-means clustering was used to identify profiles based on inclusion needs ratings. A two-cluster solution was selected based on silhouette scores and interpretability. Demographic composition was reviewed to determine whether profiles aligned with identity categories or instead reflected differences in need intensity.

This study tested the replicability and generalizability of the 8-Inclusion Needs framework across settings and populations by applying the same methodology to the two independently collected samples (one organizational and one broader).

3. Results

Across both datasets, one drawn from a single organizational context (n = 46) and one from a broader, independent sample (n = 115), participants consistently rated all 13 inclusion needs items highly, with mean scores well above the midpoint of the five-point Likert scale. In the organizational sample, item means ranged from 4.08 to 4.71; in the broader sample, they ranged from 4.12 to 4.70. This cross-sample consistency provides early empirical support for the framework’s central claim: that inclusion needs are broadly experienced and considered important regardless of context or employment setting.

As shown in

Table 1, the highest-rated items in both datasets corresponded to core access-related needs, such as the ability to physically and cognitively access information and spaces. For example, “Access” and “Access.2” received the highest mean scores in both datasets, reinforcing the foundational role that accessibility plays in supporting success at work. At the other end of the scale, but still highly endorsed, were relational needs such as “Respect” and “Language,” indicating slightly greater variability in how interpersonal dynamics are experienced across workplace settings.

Internal consistency for the 13-item scale was high across both datasets, with Cronbach’s alpha = 0.889 in the organizational sample and α = 0.905 in the broader sample, suggesting excellent reliability. This strengthens the argument for treating the inclusion needs as a unified construct in subsequent analyses and supports the psychometric robustness of the scale across different populations.

Together, these results offer converging evidence for the validity of the 8-Inclusion Needs of All People framework. The consistent pattern of high importance ratings and strong reliability suggests that these needs are not only conceptually coherent but are also experienced with remarkable regularity, reinforcing their potential as a foundation for inclusive workplace design and decision-making.

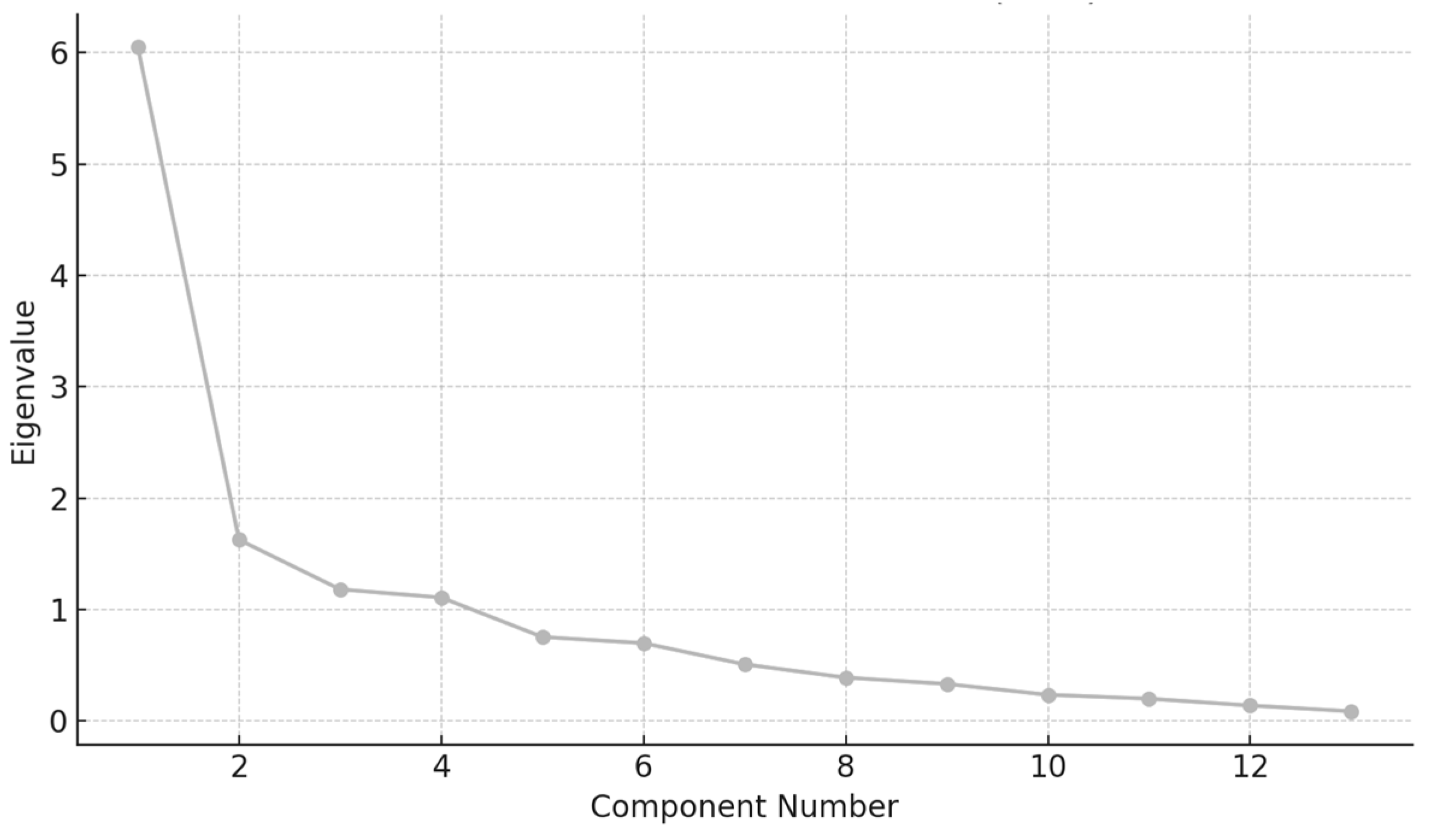

To examine the underlying structure of the 13-item inclusion needs scale, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted across both the organizational (n = 46) and broader (n = 115) samples. In both datasets, the scree plots revealed a sharply declining eigenvalue trajectory, with a dominant first factor exceeding the conventional eigenvalue threshold of 1.0 and surpassing 5.0 in both samples. As illustrated in

Figure 1, this pattern offers strong empirical support for a unidimensional structure, affirming the theoretical premise that the inclusion needs, while conceptually distinct, function as a cohesive, interdependent construct rather than as isolated or identity-specific domains.

A three-factor solution was also extracted to explore whether additional underlying dimensions might exist. While some modest differentiation emerged, suggesting possible conceptual groupings such as psychological and relational needs (e.g., support, respect), structural access needs (e.g., physical and informational access), and participation-related needs (e.g., opportunity, representation), the strength of the first factor, combined with high internal consistency, supported continued use of a unified composite score.

As shown in

Table 2, all 13 items loaded positively onto the first principal component, with most loadings falling in the moderate to strong range. In both datasets, relational needs such as “Language” and “Respect” demonstrated the strongest loadings, while access-related items loaded somewhat lower, particularly in the organizational sample. These results indicate that although the salience of specific needs may vary across individuals and settings, the underlying structure of the inclusion needs scale is coherent and stable.

Together, the PCA findings across both samples provide robust justification for treating the 8-Inclusion Needs of All People framework as a unidimensional model. The scale demonstrates strong psychometric integrity, offering a reliable foundation for future measurement, validation, and application in organizational inclusion assessment.

To evaluate the predictive utility of the 8-Inclusion Needs of All People framework, linear regression analyses were conducted using the composite Inclusion Needs Score to predict three inclusion-related outcomes: (i) self-perceived valuing of difference, (ii) perception that others value difference, and (iii) feeling included within the organization.

In both the organizational and broader samples, the inclusion needs score significantly predicted the second and third outcomes: perceptions that others value difference and personal feelings of inclusion. These results reinforce the framework’s practical relevance in shaping workplace experiences and affirm its conceptual clarity as a diagnostic tool.

As shown in

Table 3, stronger endorsement of inclusion needs was associated with significantly higher perceptions that others value and embrace difference (organizational: β = 0.54, R² = 0.10, p = .03; broader: β = 0.50, R² = 0.25, p < .001), as well as stronger feelings of being included (organizational: β = 0.51, R² = 0.15, p = .008; broader: β = 0.54, R² = 0.29, p < .001). These effect sizes were moderate to strong, particularly in the broader sample, where the inclusion needs score explained over a quarter of the variance in perceived inclusion.

In contrast, the relationship between inclusion needs and self-reported valuing of difference did not reach statistical significance in either dataset (organizational: β = 0.17, p = .22; broader: β = 0.18, p = .07). This likely reflects a ceiling effect, as this outcome showed limited variability, with most participants already reporting strong personal values around difference. From a construct validity perspective, this distinction is meaningful: valuing diversity may be an internalized personal value, whereas perceiving inclusion and feeling included are more relational and contextual, directly influenced by how well inclusion needs are met.

Together, these findings provide strong empirical support for the predictive validity of the inclusion needs framework. When individuals rate these needs as important, they are more likely to experience inclusion positively and perceive inclusive behaviors in others. This reinforces the practical value of the framework in informing inclusive culture-building efforts, leadership practices, and employee engagement strategies.

To examine whether inclusion needs are perceived differently across identity groups, independent samples t-tests were conducted on both datasets (

Table 4). In the organizational dataset (n = 46), only male and female identities were sufficiently represented to allow statistical comparison. No significant difference emerged: female participants rated inclusion needs slightly higher (M = 4.48, SD = 0.38) than males (M = 4.33, SD = 0.56), but the difference was not statistically significant, t(47) = –1.078, p = .286.

In the broader dataset (n = 115), gender-based comparisons also revealed no significant differences: females (M = 4.60, SD = 0.38) and males (M = 4.56, SD = 0.42), t(87) = –0.430, p = .670. In addition, exploratory t-tests were performed for other identities where sample sizes allowed, including disability, chronic illness, and caregiver status. None of these analyses revealed statistically significant differences in Inclusion Needs Scores.

No meaningful patterns emerged when examining inclusion needs by the number of identities participants selected (intersectionality count). Across both samples, correlation analyses revealed no relationship between the number of intersecting identities and the overall Inclusion Needs Score. This suggests that the intensity of inclusion needs does not increase simply by holding more marginalized or underrepresented identities.

Together, these findings offer compelling support for the central premise of the 8-Inclusion Needs of All People framework: while identities shape lived experience, the needs themselves are human and shared. Designing inclusive environments based on these universal needs, rather than fragmented identity groupings, may offer a more scalable, equitable, and unifying approach to workplace inclusion.

To identify meaningful subgroups based on how individuals prioritize inclusion needs, k-means clustering was applied to the standardized scores of all 13 inclusion needs items in both datasets (

Table 5). In each case, a two-cluster solution was optimal based on silhouette scores (Organizational Sample: 0.314; Broader Sample: 0.300), indicating moderate separation between clusters.

Across both samples, the clusters reflected a difference in intensity, not in kind. One cluster comprised participants who rated all inclusion needs as consistently high, while the other reported slightly lower—but still strongly endorsed—ratings. Importantly, mean scores for every item in both clusters remained above 4.0 on a five-point scale. This supports the core proposition of the 8-Inclusion Needs framework: inclusion needs are broadly experienced and universally important, even as their intensity varies between individuals.

An exploration of identity characteristics within clusters revealed that in both datasets, participants in the higher-scoring cluster were more likely to be female. However, these differences were not statistically significant, and representation across other identity categories was too limited for reliable subgroup analysis.

These findings further reinforce the framework’s conceptual integrity. Inclusion needs do not differentiate participants by identity or demographic background but rather by the intensity with which these needs are prioritized. This aligns with the model’s central proposition: inclusion needs are shared human requirements, vital for all people to succeed and thrive in the workplace.

Summary of Findings

The findings from both datasets, the organizational sample (n = 46) and the broader independent sample (n = 115), provide strong empirical support for the validity and utility of the 8-Inclusion Needs of All People framework. Across all 13 inclusion needs items, participants consistently rated the needs as highly important to their success at work, with average scores exceeding 4.0 on a five-point scale in both samples. This pattern of endorsement affirms the framework’s foundational claim: inclusion needs are experienced widely, valued, and required across diverse contexts.

Psychometric analyses revealed excellent internal consistency in both datasets (Cronbach’s α = 0.889 and 0.905, respectively), and Principal Component Analysis confirmed a unidimensional structure, suggesting the inclusion needs operate as an integrated system rather than separate, identity-bound components. While a three-factor solution revealed modest conceptual groupings, the strength of the dominant factor supported continued use of a composite score.

Regression analyses further validated the framework’s predictive relevance. Individuals who rated inclusion needs as more important were significantly more likely to report feeling included and to perceive that others value difference. This relationship was consistent across samples and illustrates the material connection between inclusion needs and key inclusion-related outcomes such as psychological safety, value alignment, and belonging.

Importantly, no statistically significant differences in inclusion needs were observed across gender or identity groupings in either dataset. Analysis of intersectionality count also found no meaningful correlation with inclusion needs intensity. Cluster analysis revealed that individuals differ in how strongly they prioritize inclusion needs, but the distinction lies in intensity, not in kind, further reinforcing the notion that inclusion needs are universal human requirements rather than identity-specific accommodations.

Taken together, these findings offer robust cross-sample validation of the framework. They demonstrate that the 8-Inclusion Needs construct is not only theoretically sound and psychometrically reliable but also practically meaningful across different organizational and demographic contexts. While continued research across larger and more varied samples will be important, this dual-sample analysis provides a compelling foundation for understanding inclusion through a shared, human-centric lens.

4. Discussion

This study provides empirical support for the 8-Inclusion Needs of All People framework, validating its central proposition that inclusion needs are not specific to any one identity group but are shared, interdependent, and essential for people to fulfill their potential, succeed at work, and thrive. Through a combination of descriptive statistics, psychometric analysis, predictive modelling, and identity-based comparisons, the results across two distinct datasets (one organizational and one independent) consistently reinforce the framework’s positioning of inclusion as a human rather than a categorical construct.

Participants in both samples rated all 13 inclusion needs items as highly important to their ability to fulfil their potential and success at work, with minimal variation across contexts. The strongest endorsements were for access-related needs, pointing to the foundational importance of being able to navigate and participate fully in the workplace. Relational needs, such as respect and inclusive language received slightly lower, though still strong, endorsements, suggesting these may be shaped more by context or interpersonal dynamics. This variation in intensity, not in kind, reflects the framework’s view of inclusion needs as universally relevant yet personally and contextually nuanced.

Principal Component Analysis affirmed a unidimensional structure in both datasets, with a dominant first factor and high internal consistency, supporting the use of a composite score. Although a three-factor solution revealed some conceptual clustering (e.g., access, participation, relational needs), the coherence of the single-factor solution underscores the interdependent nature of inclusion needs. This reinforces the framework’s core theoretical shift, from siloed or identity-specific inclusion interventions to a unified, human-centered approach.

The framework’s predictive validity demonstrated its practical relevance. In both samples, participants who placed higher importance on their inclusion needs were significantly more likely to feel included and to perceive inclusive attitudes among colleagues. These findings highlight the connection between inclusion needs and individual perceptions of psychological safety, belonging, and value alignment, suggesting that meeting these needs is not just ethically important but materially influential in shaping inclusion outcomes.

Importantly, inclusion needs did not differ significantly across gender or intersectionality count, and cluster analysis revealed two profiles that differed only in intensity, not in kind. Individuals in the higher-priority cluster placed greater emphasis on all needs, yet both groups rated every need as important. This pattern held across both datasets and supports the framework’s central claim: while the salience of needs may vary by experience, the needs themselves are shared across people and contexts.

While the framework centers shared human needs, it does not discount the role of identity in shaping barriers to inclusion. Instead, it provides a unifying foundation that can be layered with context-specific insights. In this way, the model acknowledges that exclusion often manifests differently depending on identity while offering a scalable approach that addresses the inclusion needs of the whole person and ensures inclusion is embedded at a systemic level for all people, not just addressed reactively or piecemeal.

Together, these findings contribute a significant and timely alternative to identity-focused inclusion models. Rather than denying the relevance of identity, the 8-Inclusion Needs framework offers a way to transcend identity silos by focusing on what all people need to thrive. In doing so, it provides a practical and strategic foundation for inclusive systems, policies, and environments that are scalable, measurable, and sustainable. Rather than responding reactively to harm or tailoring narrowly to demographic groups, organizations can use this framework to proactively meet the inclusion needs of all people by default—embedding inclusion as a system of human requirements rather than a series of exceptions.

Implications for Practice and Research

The findings of this study have clear and timely implications for both organizational practice and future research. Most notably, the consistent and high importance ratings across all 13 inclusion needs, across two distinct datasets and regardless of participants’ identity, indicate that organizations can move beyond fragmented, identity-specific initiatives and toward systemic, needs-based, more inclusive, scalable, and effective strategies.

For practitioners, the validated 8-Inclusion Needs framework offers a practical diagnostic lens to audit workplace systems, policies, and behaviors. It enables leaders to identify where human needs for allowance, opportunity, access, and respect are being met, or where gaps persist. Rather than reacting to harm and discrimination or relying solely on representational metrics, organizations can proactively design workplace conditions that meet these universal needs by default. This positions inclusion not only as a moral imperative [

16] but as a structural enabler of performance [

17], psychological safety [

18], and organizational sustainability [

19].

In particular, the framework can be embedded into leadership capability models, employee experience assessments, organizational design, and inclusion measurement systems. Its universal language helps depoliticize inclusion conversations while anchoring them in human-centered science, supporting implementation even in politically or culturally resistant contexts [

20].

Beyond internal practices, the framework also offers practical value for product and service design [

21,

22], customer experience [

23], and risk mitigation [

24,

25]. Just as employees require conditions that enable them to thrive, customers and clients engage more meaningfully with offerings that acknowledge and meet their human needs. Applying the 8-Inclusion Needs lens externally allows organizations to evaluate whether their products, services, and customer touchpoints are accessible, inclusive in language, respectful, and representative of diverse experiences. This approach enhances customer satisfaction and expands market reach while also helping to mitigate the risk of discrimination claims or public backlash, particularly in areas such as advertising and marketing [

26], digital accessibility [

27,

28], and service delivery [

29,

30]. By embedding inclusion needs into the design of customer experiences and offerings, organizations can proactively reduce harm, increase trust, and demonstrate social responsibility, all while aligning inclusion with core business value.

For researchers, this study advances the field by empirically testing a theoretically grounded, universally applicable inclusion model. It demonstrates that inclusion can be operationalized not as a subjective feeling or an identity-specific benefit, but as a set of shared human requirements. However, further research is needed to strengthen generalizability. While this study combined data from one organization and a broader independent sample, replication across sectors, industries, and global regions will be critical to test the framework’s applicability at scale.

Additionally, the reliance on self-reported importance ratings may introduce desirability bias, as participants might overstate their alignment with socially valued inclusion principles. While the findings provide strong early validation, future research should complement this approach with observed behavioral data, objective organizational metrics, or longitudinal designs to more fully assess how inclusion needs manifest in practice and influence real-world outcomes.

Future studies should also explore the organizational conditions and leader behaviors that best fulfill these needs, and the consequences when they are left unmet. Longitudinal and intervention-based research could examine how changes in systems, practices, or leadership influence inclusion need fulfillment and downstream outcomes such as retention, engagement, innovation, and well-being.

Although this study included a wide range of identity dimensions, several were underrepresented. Larger and more diverse samples in future studies will enable deeper intersectional analyses and help determine whether the salience or prioritization of needs differs across lived experiences. Such analyses could refine how organizations tailor their strategies while maintaining a universal foundation.

Finally, as the DEI landscape continues to evolve amid growing complexity and political tension [

31], the non-ideological, needs-based framing of the 8-Inclusion Needs model offers a promising bridge. By focusing on what all people need to thrive, rather than who people are assumed to be, this approach offers a scalable and inclusive path forward.

In sum, this study offers strong preliminary evidence that the 8-Inclusion Needs framework is both conceptually coherent and practically useful. It provides a replicable, measurable, and human-centered foundation for creating more inclusive and ultimately more thriving organizations. Continued research and application will help determine how far its reach can extend across industries, geographies, and future-of-work challenges.

5. Conclusions

This study provides robust empirical support for the 8-Inclusion Needs of All People framework as a conceptually coherent, psychometrically sound, and practically relevant model for understanding what individuals require to thrive at work. Drawing on two distinct datasets, one from a single organization and one from a broader, independent sample, the findings consistently demonstrate that inclusion needs are widely experienced, highly valued, and predictive of key workplace inclusion outcomes.

Across both samples, participants rated the 13 inclusion needs items with consistently high importance. The scale showed excellent internal reliability, and Principal Component Analysis confirmed a strong unidimensional structure, validating the framework’s use as a unified construct. Furthermore, regression and cluster analyses reinforced the framework’s predictive utility and universality: people who prioritized their inclusion needs reported stronger feelings of inclusion and observed greater valuing of difference in their workplace, regardless of identity or intersectional background.

These results advance the inclusion field by shifting the conversation from fragmented, identity-based approaches to a systemic, needs-based paradigm. The 8-Inclusion Needs framework offers a practical foundation for designing inclusive environments where all individuals can meaningfully contribute, succeed, and feel psychologically safe, without reducing inclusion to group-specific interventions.

While the findings represent an important step forward, continued research is needed to confirm the framework’s generalizability across industries, geographies, and demographic groups. Nonetheless, this study establishes a strong foundation for applying the 8-Inclusion Needs of All People framework as both a diagnostic and strategic tool in building inclusive and thriving workplace cultures.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it involved anonymous survey responses from adult participants in workplace settings, posed no more than minimal risk, and did not collect any identifying information. In accordance with national guidelines and institutional policies, research of this nature, focused on organizational practices and conducted without deception or intervention, is exempt from formal ethics committee review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- K. April, “The new diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) realities and challenges,” HR New Agenda, pp. 119–132, 2021.

- D. L. Pittman, “Examining the effectiveness of diversity, equity and inclusion: The internal stakeholder perspective,” PhD Thesis, 2025.

- M. Moody-Ramirez, C. Byerly, S. Mishra, and S. R. Waisbord, “Media representations and diversity in the 100 years of journalism & mass communication quarterly,” Journal. Mass Commun. Q., vol. 100, no. 4, pp. 826–846, 2023.

- I. M. Singleton, S. C. Poon, R. U. Bisht, N. Vij, F. Lucio, and M. V. Belthur, “Diversity and inclusion in an orthopaedic surgical society: a longitudinal study,” J. Pediatr. Orthop., vol. 41, no. 7, pp. e489–e493, 2021.

- D. Davenport et al., “Faculty recruitment, retention, and representation in leadership: an evidence-based guide to best practices for diversity, equity, and inclusion from the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine,” West. J. Emerg. Med., vol. 23, no. 1, p. 62, 2022.

- K. Griffin, J. Bennett, and T. York, “Leveraging promising practices: Improving the recruitment, hiring, and retention of diverse & inclusive faculty,” 2020.

- C. McCarty Kilian, D. Hukai, and C. Elizabeth McCarty, “Building diversity in the pipeline to corporate leadership,” J. Manag. Dev., vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 155–168, Jan. 2005. [CrossRef]

- A. T. Mohan et al., “Diversity matters: a 21-year review of trends in resident recruitment into surgical specialties,” Ann. Surg. Open, vol. 2, no. 4, p. e100, 2021.

- L. A. Wilson, “The 8-Inclusion Needs of All People: A Proposed Framework to Address Intersectionality in Efforts to Prevent Discrimination,” Int. J. Soc. Sci. Res. Rev., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 296–314, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Al-Faham, A. M. Davis, and R. Ernst, “Intersectionality: From Theory to Practice,” Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 247–265, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. O’Keefe, S. Salunkhe, C. Lister, C. Johnson, and T. Edmonds, “Quantitative and qualitative measures to assess organizational inclusion: A systematic review,” J. Bus. Divers., vol. 20, no. 5, 2020.

- M. Dennissen, Y. Benschop, and M. van den Brink, “Rethinking Diversity Management: An Intersectional Analysis of Diversity Networks,” Organ. Stud., vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 219–240, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. K. Rodriguez, E. Holvino, J. K. Fletcher, and S. M. Nkomo, “The Theory and Praxis of Intersectionality in Work and Organisations: Where Do We Go From Here?,” Gend. Work Organ., vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 201–222, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Wilson, “Inclusion Needs Through the Lens of Intersectionality: Evidence supporting The 8-Inclusion Needs of All People Framework,” Int. J. Soc. Sci. Stud., vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 38–56, 2023. [CrossRef]

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, “The Belmont Report. Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research.,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1979. [Online]. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html.

- A. Wagner, “Avoiding the spotlight: public scrutiny, moral regulation, and LGBTQ candidate deterrence,” Polit. Groups Identities, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 502–518, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Ferrary and S. Déo, “Gender diversity and firm performance: when diversity at middle management and staff levels matter,” Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag., vol. 34, no. 14, pp. 2797–2831, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Singh, D. E. Winkel, and T. T. Selvarajan, “Managing diversity at work: Does psychological safety hold the key to racial differences in employee performance?,” J. Occup. Organ. Psychol., vol. 86, no. 2, pp. 242–263, 2013. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Kamarudin, A. M. Ariff, and W. A. Wan Ismail, “Product market competition, board gender diversity and corporate sustainability performance: international evidence,” J. Financ. Report. Account., vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 233–260, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Myeong, “Depoliticizing DEI: Path to fulfillment of its core values and effective implementation,” Ind. Organ. Psychol., vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 511–515, 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. M. Patrick and C. R. Hollenbeck, “Designing for all: Consumer response to inclusive design,” J. Consum. Psychol., vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 360–381, 2021.

- J. D. Shulman and Z. (Jane) Gu, “Making Inclusive Product Design a Reality: How Company Culture and Research Bias Impact Investment,” Mark. Sci., vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 73–91, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. MarieDay, Incorporating Inclusivity to Positively Impact Customer Experience Outcomes and Organizational Culture. SAGE Publications: SAGE Business Cases Originals, 2023.

- O. Unsal, “Employee relations and firm risk: Evidence from court rooms,” Res. Int. Bus. Finance, vol. 48, pp. 1–16, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M.-C. Suciu, G. G. Noja, and M. Cristea, “Diversity, social inclusion and human capital development as fundamentals of financial performance and risk mitigation,” Amfiteatru Econ., vol. 22, no. 55, pp. 742–757, 2020.

- E. Friedmann, M. Weiss-Sidi, and E. Solodoha, “Unveiling impact dynamics: Discriminatory brand advertisements, stress response, and the call for ethical marketing practices,” J. Retail. Consum. Serv., vol. 79, p. 103851, 2024.

- M. Tushev, F. Ebrahimi, and A. Mahmoud, “A Systematic Literature Review of Anti-Discrimination Design Strategies in the Digital Sharing Economy,” IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng., vol. 48, no. 12, pp. 5148–5157, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Parks, A. K. Paros, and M. Yakubu, “Examining Impacts on Digital Discrimination, Digital Inequity and Digital Injustice in Higher Education: A Qualitative Study.,” Inf. Syst. Educ. J., vol. 23, no. 1, 2025.

- L. Zhou, J. Liu, and D. Liu, “How does discrimination occur in hospitality and tourism services, and what shall we do? A critical literature review,” Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 1037–1061, 2022.

- P. Gunarathne, H. Rui, and A. Seidmann, “Racial bias in customer service: evidence from Twitter,” Inf. Syst. Res., vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 43–54, 2022.

- B. L. McGowan, R. Hopson, L. Epperson, and M. Leopold, “Navigating the backlash and reimagining diversity, equity, and inclusion in a changing sociopolitical and legal landscape,” J. Coll. Character, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).