1. Introduction

In contemporary societies, education has historically played an essential role as a social institution aimed at the socialization of individuals, their integration into collective life and their insertion into the labor market. In this sense, education is not just as content delivery but as a dynamic process affecting identity, adaptation, and citizenship [

1].

Nevertheless, the concept of ‘educational quality’ has evolved significantly, being subjected to considerable strain from new social demands, technological advances, economic crises and cultural transformations [

2,

3]. In the contemporary context, the discourse on quality in education encompasses a range of dimensions, including equity, sustainability, innovation and inclusion, especially in developing countries [

4].

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) data [

5], more than 40% of school-age children worldwide do not have access to quality education that integrates sustainability skills. In addition, 33% of households in low-income countries lack internet connectivity, exacerbating the digital inequalities.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that only 20% of member countries have fully integrated the global citizenship approach into their national curricula [

6]. In the same line, recent World Bank studies show that continuing teacher training with a focus on sustainability remains fragmented and poorly funded in 60% of the education systems analyzed [

7].

As illustrated in

Table 1, there is a clear distinction between countries that have demonstrated notable progress and those that have shown less progress in terms of the reduction of the percentage of young adults (aged 25–34) who lack upper secondary education. A notable reduction in the percentage of young adults without upper secondary education has been achieved by countries such as Turkey, Mexico and Portugal, reflecting the success of educational policies and access to education; the United States and Germany had already attained low percentages in 2013. Consequently, further reductions are more limited, but the trend remains positive. Finally, Nordic countries such as Finland, Norway and Sweden demonstrate negligible changes, which may be attributable to the fact that they already exhibited remarkably high levels of upper secondary education, leaving minimal space for substantial improvements.

These figures highlight the urgent need to move towards systemic reforms that guarantee a more equitable, inclusive and transformative education at the global level.

The present theoretical article proposes a critical review of the concept of sustainable quality education, understood as education that not only pursues high academic standards but also responds to the needs of the social, economic and environmental context, promoting meaningful, equitable and lasting learning. In this sense, the following discussion will examine the main challenges facing education today, emerging educational innovations and the barriers that still hinder their effective and universal implementation.

This reflection is timely, as it coincides with a period of significant challenges to education. These challenges are precipitated by global phenomena, including accelerated digitalization, persistent inequalities, climate change and forced displacement. Utilizing a theoretical and multidisciplinary approach, the article contributes to the scientific debate on how to ensure quality education that is truly sustainable, innovative and fair for all sectors of the population.

1.1. Methodological Notes

This article is based on a theoretical review of academic literature published in the last ten years, focusing on the areas of education for sustainable development, educational innovation and equity. Databases such as Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar were consulted, using key terms such as ‘sustainable education’, ‘educational equity’, ‘digital transformation in education’ and ‘global citizenship’. Empirical studies and systematic reviews in diverse contexts were prioritized.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Educational Quality: Evolution and Current Dimensions

The concept of educational quality has been subject to multiple interpretations over time. In its early formulations, the concept was predominantly associated with quantifiable academic outcomes, such as performance on standardised tests. However, with the advancement of pedagogical thinking, the inclusion of critical approaches and the emergence of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4, educational quality has been redefined as a multidimensional concept [

10].

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNESCO [

8], the quality of education encompasses not only equitable access, but also the provision of relevant content, the implementation of effective teaching processes, the establishment of adequate learning conditions, and the attainment of outcomes that empower individuals to develop their potential and participate actively in society. A comprehensive approach requires a re-evaluation of traditional assessment indicators and facilitates the inclusion of elements such as cultural relevance, community participation and sustainability of learning. Previous literature has shown that traditional performance-based assessment promotes a test-driven pedagogical approach that significantly limits the implementation of more innovative teaching methods and hinders the development of key skills such as problem solving or critical thinking in students [

11].

According to these studies, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) acts as a catalyst for innovation driven by both teachers and students, especially when they participate in an environment that fosters reflective and participatory learning. The effectiveness of this more sustainability-oriented innovation depends to a large extent on the students’ field of study, their prior knowledge and experience, as well as institutional support, which underlines the importance of inclusive and context-sensitive curriculum design. There is a need to bridge the gap between sustainability theory and practice, strengthening the argument that innovation is sustainable and transferable across disciplines [

12].

Sustainable quality education requires time and structural support for innovation. Short-term or isolated teaching interventions may not suffice to cultivate lasting, impactful educational innovation. Interdisciplinary learning environments are critical to fostering systemic thinking, creativity, and sustainable problem-solving—especially in formal and non-formal education settings aiming to address complex societal challenges [

13].

In this sense, technology plays an important role in innovation for educational quality, especially since the COVID-19. The pandemic accelerated digitalization in education, emphasizing the dual impact on sustainable education: both as a disruptive force and as a driver of transformation [

14].

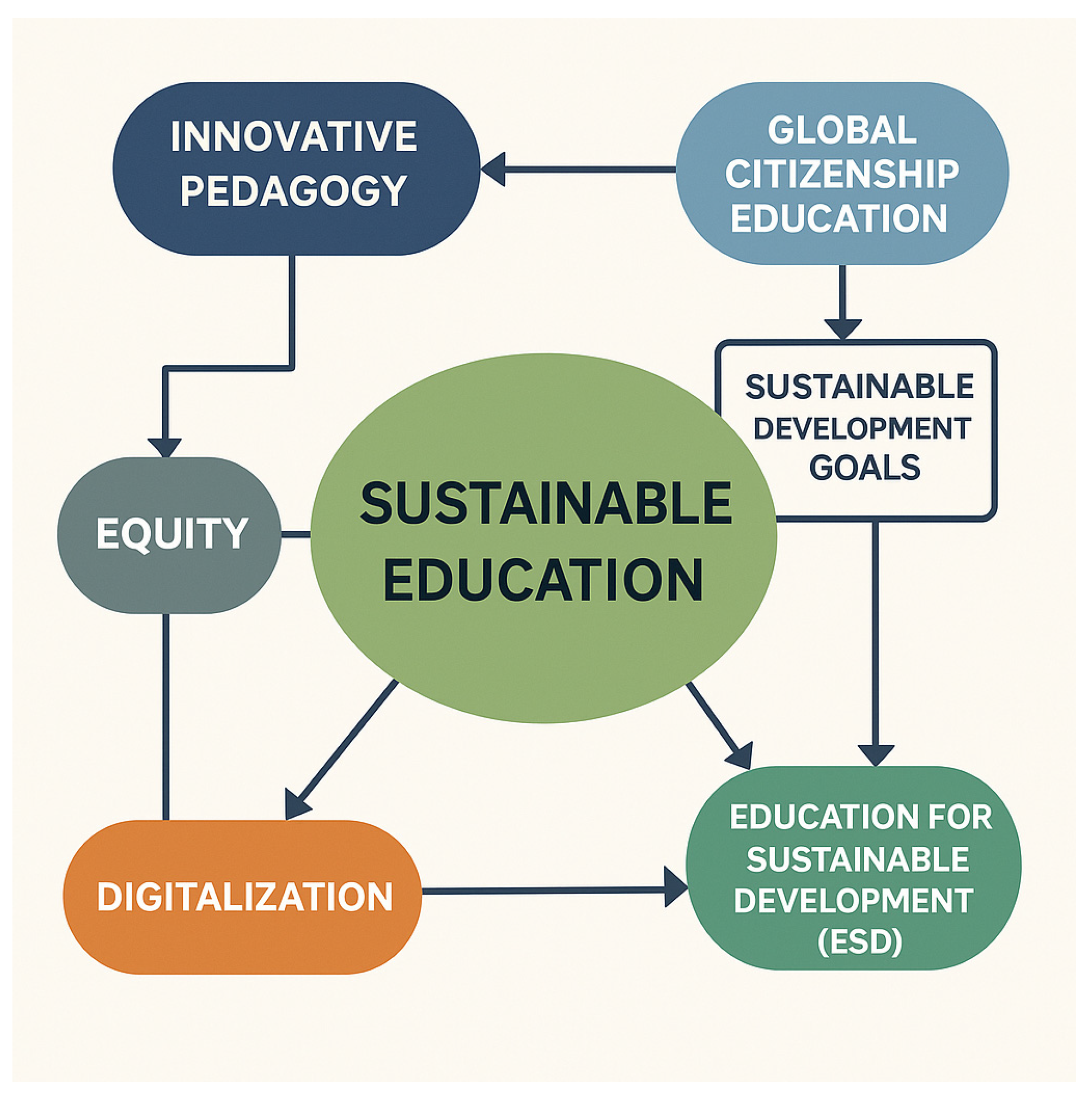

Figure 1 displays a conceptual map of sustainable education and its components.

2.2. Educational Innovation: Beyond Technology

During the COVID-19 crisis, digital tools and platforms became essential to maintaining educational continuity, but also exposed and deepened inequalities in access, readiness, and digital literacy. However, they also enabled new models of sustainable, flexible, and hybrid learning, which may continue to evolve post-pandemic [

14].

Innovation in education is often associated with the incorporation of digital technologies. However, in a broader sense, it involves a profound transformation of teaching practices, management models and forms of interaction between teachers, students and knowledge. Innovating means rethinking the very meaning of teaching and learning, as well as developing proposals that respond to the challenges of the present without compromising the possibilities of the future. A Curriculum 4.0 encourages learner-centered design, integration of technology, and adaptability to industry demands. It promotes customized learning paths, combining broad interdisciplinary knowledge with specialized skills [

15].

Through approaches such as project-based learning, the flipped classroom and critical pedagogies, innovation seeks to break with traditional models in order to promote a more participatory, contextualized and meaningful education. The efficacy of these methods is evidenced by their demonstrable superiority over traditional approaches in terms of student participation, enhanced academic performance and the cultivation of critical thinking skills. Furthermore, active learning methods have been shown to promote 21st-century skills [

16].

In this sense, gamification represents a growing area of educational innovation with strong links to digital transformation and student-centered pedagogy. The term refers to the application of game design elements and principles, including points, badges, leaderboards, challenges, and storytelling, in non-playful learning contexts. The objective of this integration is to motivate students and enhance their engagement. The integration of gamification elements within educational settings has been demonstrated to enhance student engagement and motivation, thereby transforming passive learning into an active and participatory experience. The programme draws upon both intrinsic and extrinsic motivators, thereby fostering a sense of drive and ambition among students, particularly within the context of blended and online learning environments [

17,

18].

In this context, the sustainability of innovations becomes a key criterion, understood as their ability to stand the test of time, adapt to different contexts and generate long-term impact.

2.3. Educational Sustainability from a Comprehensive Perspective

The concept of sustainability in education goes beyond ecological and environmental concerns, encompassing social, economic and institutional dimensions [

19]. The concept refers to the capacity of education systems to provide equitable learning opportunities throughout the life cycle, without reproducing existing structural inequalities or depleting limited resources [

20].

The current emphasis on performance and efficiency as primary goals of education undermines other broader educational goals, such as promoting environmental awareness or civic responsibility. This economic approach can increase educational inequalities by prioritizing skills and competences that are of interest to the market over the comprehensive development of students. An educational model that recognizes the interconnectedness of social and ecological systems would clearly promote curricula and structures that address environmental issues as part of a broader social dynamic, promoting equity and sustainability, rather than in isolation. Education can become a powerful tool for social transformation and the reduction of inequalities of all kinds when we empower students to engage with social challenges, especially environmental issues [

21].

The promotion of critical thinking, active citizenship and commitment to the common good are all key tenets of sustainable education [

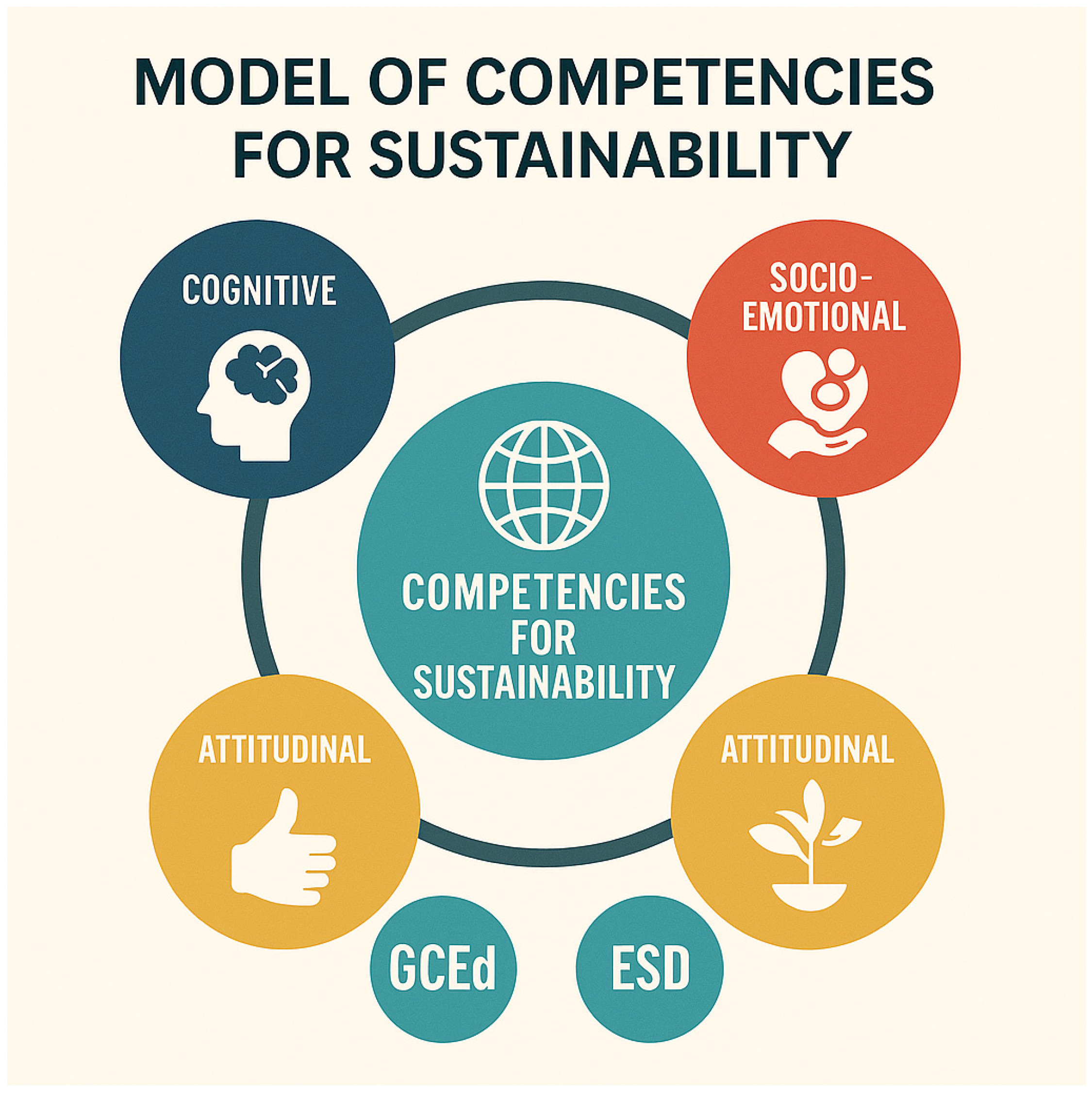

22]. Global Citizenship Education (GCEd) perspective emphasizes that a well-designed curriculum can improve students’ knowledge, socio-emotional skills and attitudes towards global issues, which is a strong argument for incorporating GCEd into formal education systems (

Figure 2).

This approach combines theory with participatory and experiential learning, and demonstrates that real-world experiences significantly improve learning outcomes and student engagement [

23].

Educational programmes are most successful when they are tailored to students’ prior knowledge, disciplinary background and motivational factors. This requires tailoring educational interventions to the diverse characteristics of learners to avoid the common mistake of ‘preaching to the choir’.

This requires teacher training, the creation of safe learning environments and support for national policies to integrate GCEd into curricula, as well as institutionalized support for teacher development and curriculum resources by policy makers [

23].

In this sense, sustainability becomes a cross-cutting principle that should guide both educational policies and everyday practices in classrooms, teacher training and curriculum development.

2.4. Educational Sustainability as an Ethical-Political Principle

Sustainability is often conceived from a technical or environmental perspective, without considering that it is also an ethical imperative. Sustainable education involves training citizens to make responsible, fair and common good-oriented decisions. From this perspective, sustainability in education is not limited to curriculum content but extends to forms of governance, the inclusion of diverse voices and intergenerational justice. Integrating this approach requires transforming not only the ‘what’ is taught, but also the ‘how’, the “who” and the ‘why’ [

24].

Consequently, it should not be applied exclusively to curricula in environmental science education, which tend to be the most sensitive to the issue, but rather across the board, as a means of understanding higher education in order to produce citizens with the potential to improve the world.

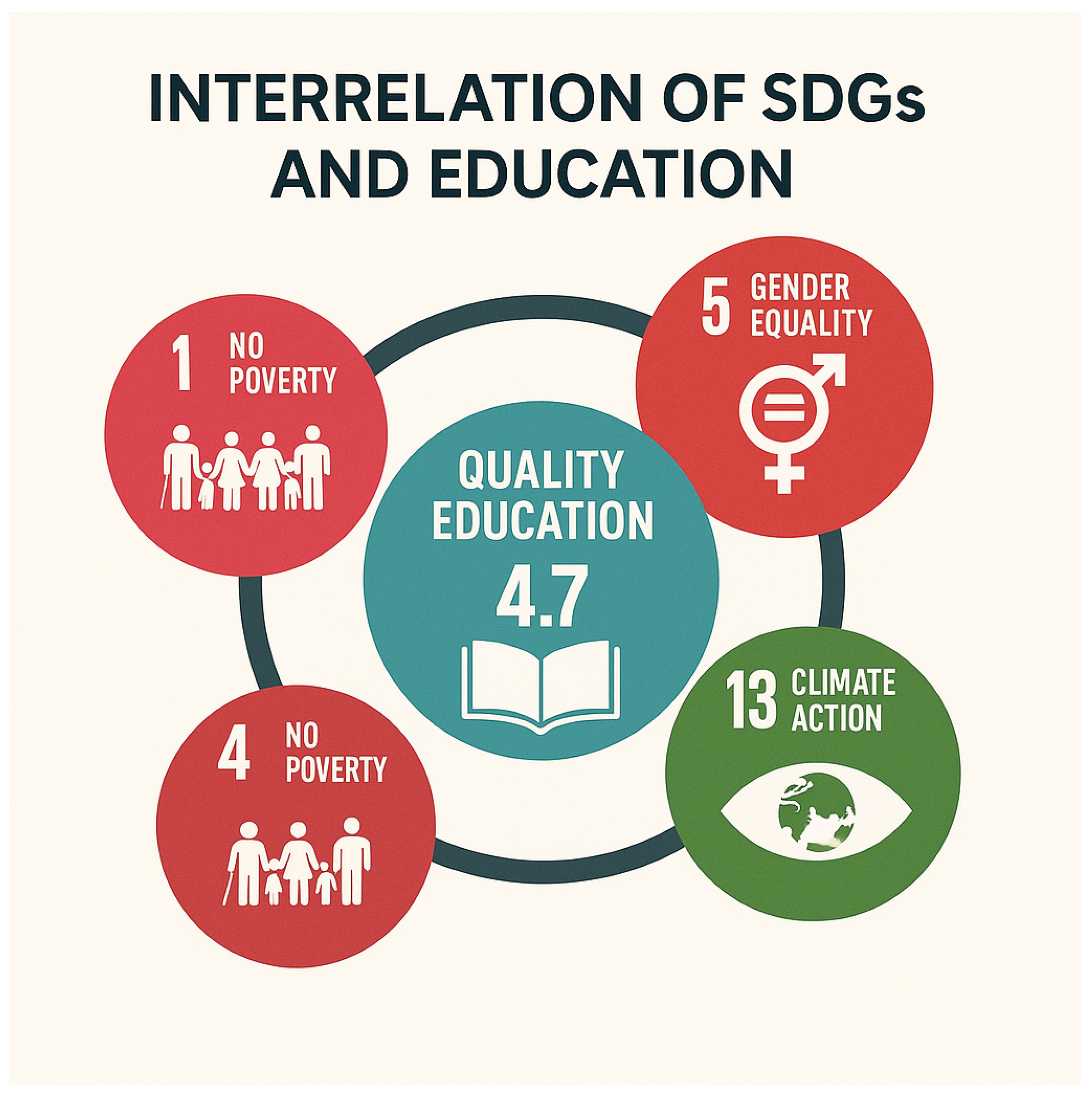

2.5. Interrelationship Between the SDGs

Although this article has focused mainly on SDG 4.7, sustainable educational quality is intrinsically linked to other SDGs. For example, gender equality (SDG 5) is indispensable for inclusive education; reducing inequalities (SDG 10) is directly related to access and equity in learning; and climate action (SDG 13) requires ecological literacy that begins in the classroom. This holistic view underscores the need for integrated curricula and institutional synergies to implement transformative education [

24], as shown in

Figure 3.

3. Sustainable Educational Innovations

The objective of sustainable educational innovations is to effect a transformation in teaching practices without recourse to extraordinary resources. The objective of these innovations is to engender structural changes that are both sustainable in the long term and adaptable to different realities. Examples of such practices include active student-centered methodologies, service-learning projects, and models of knowledge co-creation with the community. This makes teacher leadership and perceptions are crucial in sustaining educational innovation [

25].

The crux of the matter pertains to the contextualized design of proposals, their progressive implementation, and the continuous evaluation of their impact. The transfer of these experiences to other contexts necessitates cultural and pedagogical adaptations, thereby illustrating the potential for effective educational innovation that does not necessitate substantial investments.

A key issue in educational innovation is its tendency to be based on sporadic or isolated initiatives. To ensure its effectiveness and sustainability, innovation in this field must be based on continuous learning and collaboration. The long-term impact of global citizenship education depends on the iterative design of curricula and systemic support, with a focus on the sustainability of educational outcomes and programme design [

23,

25].

It is for this reason that Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) is fundamental to achieving sustainable, ethical and socially innovative leadership in higher education institutions. The crux of the matter pertains to the manner in which ESD-related pedagogical approaches engender knowledge, aptitudes and principles that are congruent with social innovation. It is incumbent upon leadership in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to promote ESD through institutional culture and curricula, identifying effective pedagogical strategies, focusing on transformative and global citizenship-oriented education, understanding that GCEd fosters competencies such as empathy, collaboration and critical thinking, traits that are vital for social innovators and sustainable leaders, and that social innovation requires a change in the purpose and content of education. HEIs could act as incubators for social innovation [

26].

In contexts where resources are limited, successful practices have been identified that integrate local knowledge, promote collaborative learning, and leverage Information and Communication Technology (ICT) as tools for inclusion. Digital pedagogy should not be implemented in isolation, but rather as part of a broader pedagogical and ethical framework grounded in sustainability and global citizenship—making a strong case for integrating both technological and curricular innovation in education system [

26,

27].

Our universities have adapted quickly to technology, especially after COVID-19. This has led many academics to advocate for a human-centered purpose behind digital innovation, reminding us that digital transformation must be driven by educational goals based on global citizenship and sustainability, not just the adoption of technology.

When it comes to technological tools (AI, big data, distance learning platforms), pedagogical approaches such as experiential and participatory learning are the ones that have truly proven to deliver meaningful results, regardless of the medium. Digital transformation as a means to achieve a more ethical, socially engaged and sustainable higher education system and attention to equity and inclusion are the main concerns in this regard, given the disparities in access and infrastructure that the pandemic has highlighted. Effective education, especially in ESD and GCEd, requires inclusive strategies tailored to learners’ backgrounds and contexts [

27].

There appears to be a broad consensus on the role of higher education institutions as key agents in promoting sustainable development. However, it is imperative that an organizational transformation through digital means is implemented, complemented by a focus on educational transformation through global citizenship pedagogy [

26,

27,

28]. It is necessary that this educational digitalization is in perfect alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically SDG 4.7 — education for sustainable development and global citizenship — as a fundamental pillar of curriculum reform. In this context, technological advancement facilitates the implementation of models of education that are more personalized, flexible and student-centered [

28].

3.1. Inequalities and Barriers to Educational Quality

Notwithstanding regulatory and institutional advances, profound inequalities endure, exerting an influence on access, retention, and educational success, with social capital as mediator [

29]. It is evident that a multitude of factors, including but not limited to poverty, rurality, gender, ethnicity, and disability, continue to exert a significant influence on educational trajectories. These structural barriers are compounded by inadequate policies, non-inclusive curricula, and assessment systems that perpetuate exclusion. This intersectionality means that certain groups face compounded disadvantages, making it imperative to consider multiple dimensions when addressing educational disparities [

29].

Moreover, digital divides and disparities in family cultural capital have been acutely revealed in emergency contexts, such as the ongoing pandemic of the novel coronavirus. It is imperative that public policies address these inequalities not only from a compensatory perspective, but also from a transformative one, promoting educational justice that guarantees real conditions of equity [

26,

27,

28,

29].

3.2. Global Challenges and Future Prospects

A primary challenge confronting global education is the necessity to furnish 21st-century citizens with the competencies required for life, employment and sustainability, by cultivating a ‘sustainability mindset’ in the students, empowering educators as change agents, integrating interdisciplinary approaches, and promoting transformative learning experiences [

30].

This necessitates a re-evaluation of pedagogical models, the enhancement of initial and ongoing teacher training, and the establishment of assessment systems that prioritize the comprehensive development of students [

31,

32]. Assessment for learning (AfL) practices are defined as being learner-centered, with the emphasis on the importance of involving learners as active participants in the assessment process, thus improving their capacity for action and commitment. They include dialogic interactions, highlighting the role of meaningful dialogues between teachers and students in fostering deeper understanding and effective learning. Furthermore, they are inclusive practices, with a gap in research identified on inclusive and discipline-specific AfL practices, suggesting the need for more specific studies [

31].

Examples of this type of assessment include real-time assessment processes in higher education to the enhancement of timely interventions is contingent upon the utilization of immediate assessment data, which facilitates the expeditious identification and remediation of student underperformance. It is essential to reduce inequalities in equal opportunities through continuous and formative assessment, in order to ensure equitable learning outcomes for all students. Furthermore, to ensure that skills development is addressed appropriately, these assessments must be aligned with the skills relevant to education in the 21st century, thus equipping students with the skills they need to effectively face and overcome the challenges of the complex and changing world in which they live and work. The promotion of institutional accountability is achieved by encouraging institutions to adopt assessment practices that support student success and institutional effectiveness [

32].

It is imperative that educational governance is oriented towards the establishment of participatory, flexible and diversity-sensitive structures. International collaboration, sustained investment in education, and the integration of the 2030 Agenda into education policies are identified as key elements for advancing towards quality education that is equitable, inclusive, and sustainable based on the following key elements: enhancing school autonomy, implementing distributed leadership, tailoring professional development, and revisiting appraisal systems [

32].

In this regard, universities, schools, social organizations and students themselves should assume an active role in the development of local solutions to global challenges, promoting a culture of lifelong learning and commitment to the common good.

3.3. Case Studies

To finish off this section, three examples of how sustainable education has been integrated into the education system are outlined.

The first example of sustainable practice in education is the Green School programme in Bali, which combines interdisciplinary teaching, learning in contact with nature and community management. This model has been replicated in different parts of the world as a benchmark for transformative and action-based education [

34].

In Latin America, the Chilean programme ‘Escuelas Sustentables’ (Sustainable Schools) promotes environmental education through ecological resource management, community projects and teacher training. Its impact has been positively evaluated in terms of changing habits and environmental awareness [

35].

In Europe, the Finnish model stands out for its educational governance based on equity, well-being and teacher confidence. The integration of socio-emotional, civic and sustainability skills into the national curriculum has been identified as key to its success [

36].

The three case studies presented here demonstrate that sustainable education is not only a possibility, but that there is no single model for achieving quality education. Rather, multiple solutions to the problem of innovation can be explored in order to address the social challenges of the present and the future.

4. Conclusions

This article has presented a theoretical review of the concept of sustainable quality education, recognizing its multidimensional and contextual nature. The study has underscored the pivotal role of educational innovation as a catalyst for transformation, while also emphasizing the imperative to surmount the structural impediments that constrain its comprehensive implementation.

The concept of sustainability in education should be comprehended as an ethical and political commitment that provides a framework for pedagogical, institutional and governmental decisions. In periods of increasing uncertainty and complexity, it is the responsibility of education to respond to the challenges of the present and prepare future generations to build a more just, caring and sustainable world. In order to do so, it must be inclusive, innovative and equitable.

The extant literature emphasizes a collective imperative: education in the 21st century must be reinvented as a transformative force for equity, sustainability and global responsibility. It is evident that each element, ranging from classroom practice to institutional leadership, digital innovation and community engagement, performs a pivotal function in the dismantling of structural inequalities and the advancement of global citizenship.

As can be seen throughout this paper, the concepts of global citizenship education (GCE) and education for sustainable development (ESD) have emerged as fundamental frameworks, as demonstrated by the emphasis placed on the importance of participatory, interdisciplinary and values-based learning [

30]. These environments have been shown to foster critical thinking and the acquisition of socio-emotional skills, as well as cultivating in students the ethical commitment necessary to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Research conducted has demonstrated that the success of sustainable educational innovation is contingent on the presence of empowered leadership and systemic support. Concurrently, with the necessity of institutional commitment to social innovation and sustainability, which must be embedded in both strategy and pedagogical practice [

25,

26,

28,

33].

The transition towards digital transformation in higher education gives rise to a range of both opportunities and challenges [

27]. These technologies must be utilized not as objectives in themselves, but as instruments to support equitable, inclusive, and student-centered education when grounded in pedagogical intention and global goals.

Assessment practices are of pivotal significance in the endeavor to bridge the existing opportunity gaps. In order to be effective, assessment must be timely, formative and designed to promote student agency and meaningful learning, particularly for underrepresented or at-risk learners [

30,

32].

In summary, a sustainable and equitable educational system must:

Prioritize pedagogies that are learner-centered, values-driven, and inclusive.

Empower educators with the necessary skills and support to function as agents of change.

Ensure that digital tools are integrated in a meaningful manner, without thereby reinforcing existing inequities.

The strategic utilization of assessment and leadership functions is imperative for the effective monitoring and facilitation of transformation processes.

In order to operationalize SDG 4, it is essential to foster interdisciplinary collaboration and policy alignment.

Education is not merely a conduit for the transmission of knowledge; it is also a catalyst for the empowerment of all learners, enabling them to contribute to the creation of a more equitable, resilient, and sustainable world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M., E.M, and A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M, and D.L.; writing—review and editing, D.L, and A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used DeepL Pro Starter for the purposes of reviewing English language. Infographics were designed with ChatGPT (version GPT-4) of OpenAI. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AfL |

Assessment for Learning |

| ESD |

Education for Sustainable Development |

| GCEd |

Global Citizenship Education |

| HEIs |

Higher Education Institutions |

| ICT |

Information and Communication Technology |

| OECD |

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| UNESCO |

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

References

- Chikaeva, Karina S.; Abutalipov, Artur R.; Davydova, Galina I.; Vakula, Ivan M.; Shkuropy, Olga I.; Kudinova, Margarita V. The effect of education on the characteristics of personal socialization in a transitional society. Revista on line de Política e Gestão Educacional 2022, 4264-4276. [CrossRef]

- Adams, Don. Defining Educational Quality. Educational Planning 1993, 9(3), 3-18.

- Kayyali, Mustafa. An overview of quality assurance in higher education: Concepts and frameworks. International Journal of Management, Sciences, Innovation, and Technology (IJMSIT) 2023, 4(2), 01-04. https://ijmsit.com/volume-4-issue-2/.

- Fomba, Benjamin K.; Talla, Dieu N; Ningaye, Paul. Institutional quality and education quality in developing countries: Effects and transmission channels. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 2023, 14(1), 86-115. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report 2023: Technology in education: A tool on whose terms? 2023. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/.

- OECD. Global Competency for an Inclusive World. 2022. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd.org/education/global-competency-for-an-inclusive-world.htm.

- World Bank. World Development Report 2023: Learning recovery to avoid a lost decade. 2023. The World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2023.

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2014. 2014. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/education-at-a-glance-2014.

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2024. 2024. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/education-at-a-glance-2014.

- UNESCO. Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4 2015. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656.

- Looney, Janet W. Assessment and Innovation in Education. OECD Education Working Papers 2009, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourati-Jamoussi, Fatma.; Dubois, Michel J.F.; Chedru, Marie; Belhenniche, Geoffroy. Education for Sustainable Development and Innovation in Engineering School: Students’ Perception. Sustainability 2021, 13(11), 6002. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116002. [CrossRef]

- Braßler, Mirjam; Schultz, Martin. Students’ Innovation in Education for Sustainable Development—A Longitudinal Study on interdisciplinary vs. Monodisciplinary learning. Sustainability 2021, 13(3), 1322. [CrossRef]

- Gorina, Larisa; Gordova, Marina; Khristoforova, Irina; Sundeeva, Lyudmila; Strielkowski, Wadim. Sustainable Education and Digitalization through the Prism of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15(8), 6846. [CrossRef]

- Law, Mei Y. A review of curriculum change and innovation for higher education. Journal of Education and Training Studies 2022, 10(2), 16.

- Austin, Steven. Innovative Pedagogical Approaches: Exploring Flipped Classroom, Inquiry-Based Learning, and Project-Based Learning. Educator Insights: Journal of Teaching Theory and Practice 2025, 1(1), 1-7.

- Deterding, Sebastian; Dixon, Dan; Khaled, Rilla; Nacke, Lennart. From game design elements to gamefulness: defining “gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media environments 2011 (pp. 9-15).

- Domínguez, Adrián; Saenz-de-Navarrete, Joseba; de-Marcos, Luis; Fernández-Sanz, Luis; Pagés, Carmen; Martínez-Herráiz, José J. Gamifying learning experiences: Practical implications and outcomes. Computers & Education 2013, 63, 380–392.

- Buchmann, Claudia; DiPrete, Thomas A.; McDaniel, Anne. Gender inequalities in education. Annu. Rev. Sociol 2008, 34(1), 319-337.

- Holland-Smith, David. Habitus and practice: social reproduction and trajectory in outdoor education and higher education. Sport, Education and Society 2022, 27(9), 1071-1085.

- Guo, Zhan; Wu, Yan; Zhang, Yu. Social Reproduction in K-12: Life-long Effects on Middle-class Students. In 2021 4th International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences ICHESS 2021 (pp. 2566-2572).

- Thomas, Ian. Critical thinking, transformative learning, sustainable education, and problem-based learning in universities. Journal of Transformative Education 2009, 7(3), 245-264.

- Chiba, Mina; Sustarsic, Manca; Perriton, Sara; Edwards, Brent. Investigating effective teaching and learning for sustainable development and global citizenship: Implications from a systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Educational Development 2021, 81, 102337.

- Rieckmann, Marco. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives. UNESCO. 2018. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444.

- Fix, Marieke; Rikkerink, Marleen; Ritzen, Henk; Pieters, Jules M.; Kuiper, Wilmad. Learning within sustainable educational innovation: An analysis of teachers’ perceptions and leadership practice. J Educ Change 2021, 22, 131–145. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Qaisar; Piwowar-Sulej, Katarzyna. Sustainable leadership in higher education institutions: social innovation as a mechanism. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2022, 23(8), 1-20.

- Deroncele-Acosta, Angel; Palacios-Núñez, Madelaine L.; Toribio-López, Alexander. Digital transformation and technological innovation on higher education post-COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15(3), 2466.

- Hashim, Mohamed A.M.; Tlemsani, Issam; Matthews, Robin D. A sustainable university: Digital transformation and beyond. Education and Information Technologies 2022, 27(7), 8961-8996.

- Ilie, Sonia; Rose, Pauline; Vignoles, Anna. Understanding higher education access: Inequalities and early learning in low and lower-middle-income countries. British Educational Research Journal 2021, 47.5, 1237-1258. [CrossRef]

- John, Michele. Education for the sustainability transition. In The Routledge Handbook of Global Sustainability Education and Thinking for the 21st Century 2025: 233-243. Routledge India.

- Arnold, Julie. Prioritising students in Assessment for Learning: A scoping review of research on students’ classroom experience. Review of Education, 2022; 10, e3366.

- Maki, Peggy L.; Kuh, George D. Real-time student assessment: Meeting the imperative for improved time to degree, closing the opportunity gap, and assuring student competencies for 21st-century needs 2023. New York: Routledge.

- Ghamrawi, Norma. Toward agenda 2030 in education: policies and practices for effective school leadership. Educational Research for Policy and Practice 2023, 22(2), 325-347.

- Green School Bali. Green School Way: Educating for a Sustainable Future. 2023. https://www.greenschool.org/bali/.

- Ministerio de Educación de Chile. Marco de Educación Integral para la Sustentabilidad y la Adaptación al Cambio Climático 2024-2027. 2024. https://sustentabilidad.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/sites/130/2024/12/Marco-de-Educacio%CC%81n-Integral-para-la-Sustentabilidad-y-la-Adaptacio%CC%81n-al-Cambio-Clima%CC%81tico.pdf.

- Välimaa, Jussi. Trust in Finnish education: A historical perspective. 2021. European Education, 53 (3-4): 168-180.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).