1. Introduction

Enterprises employ many procedures to ensure the confidentiality of their information and safeguard it from unauthorised access or infiltration. Signing process is considered one of these key procedures. Many signature verification methods have been developed and proposed in the literature. These verification methods aim to verify signatures with high accuracy, decreased complexity, and fast processing. However, signature verification continues to be one of the most challenging issues in pattern detection and identification [

1].

Thus, signature verification is a key step that contributes towards protecting systems and data from unauthorised access or infiltration. Signing process and its verification are affordable, easy to use, and have the potential to safeguard information and systems by differentiating between authentic and fake signatures which make it suitable for nearly any type of organisations [

2].

Any person can create a unique handwritten signature which consists of signs, letters, and symbols written in a specific language. This handwritten signature can be utilised for providing permission to individuals to engage in a variety of activities and transactions. It ensures a person’s authorised authenticity and its verification should distinguish a genuine signature from a forgery [

3]. This handwritten signature which is created by individuals is not a specific form or image; rather, it is a special drawing that they do as a reminder of their individuality. This is considered an important issue in signature verification methods. The signature could include a combination of symbols, numbers, letters, and shapes. Since people utilise signatures to carry out particular transactions and activities requiring identity verification using their signatures, signature difficulties occur when someone attempts to replicate or forge someone else’s signature [

4].

Handwritten signatures are used by signature verification systems to authenticate a person’s identity. These are the most accepted ways to identify individuals and the level of authority given to them in both social and legal contexts [

5].

Furthermore, Mohamad et al. [

6] stated that the signature verification methodology is an easy way to distinguish a genuine signature from a fake one. Also, being the most secure way for bank and credit card transactions and a widely accepted strategy to information security, signature verification offers a number of advantages.

Additionally, because a user may easily change his/her signature, unlike iris or face patterns, which are unchangeable, the signature verification method is believed to be more effective than other non-biometric and biometric systems [

7].

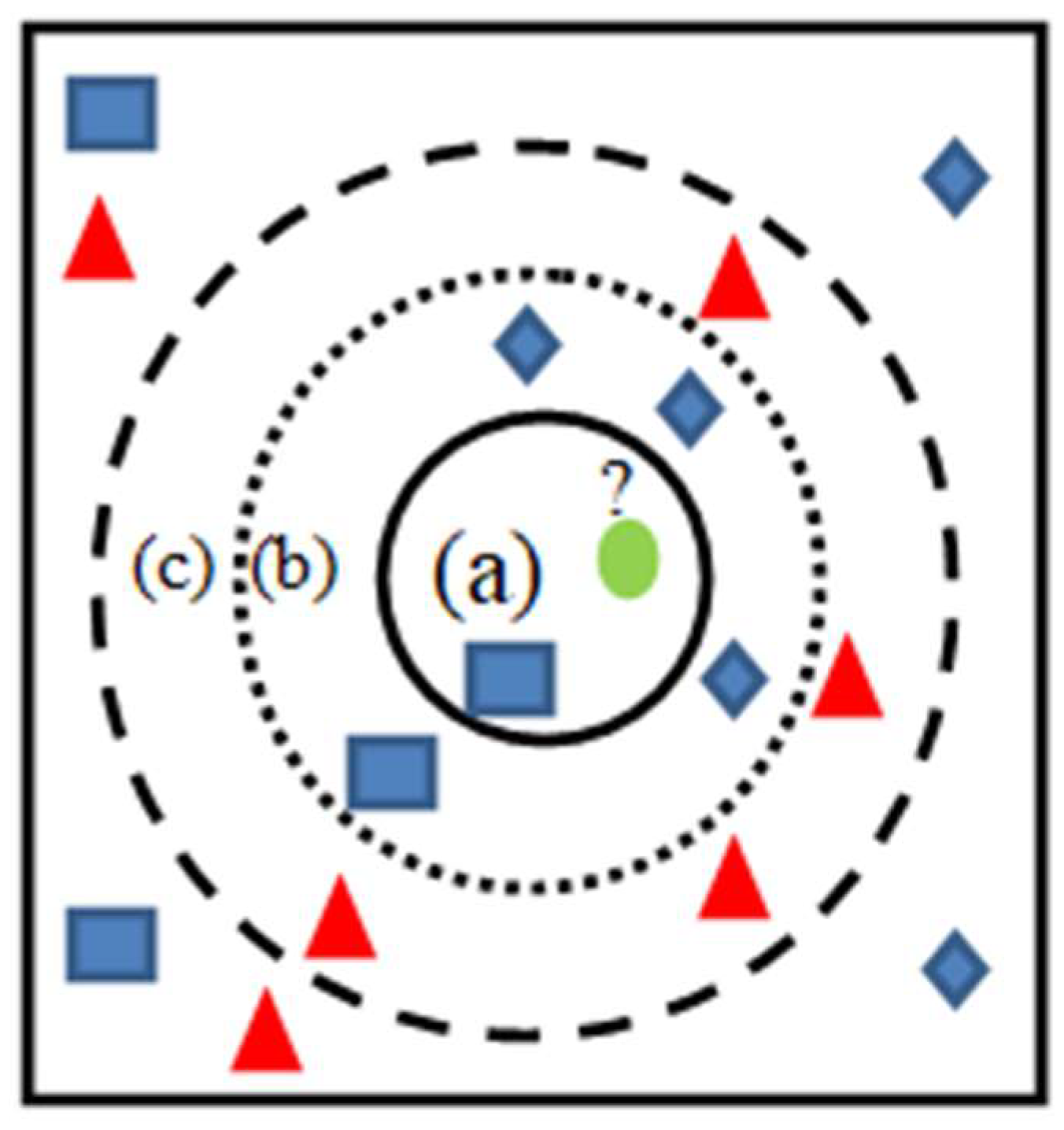

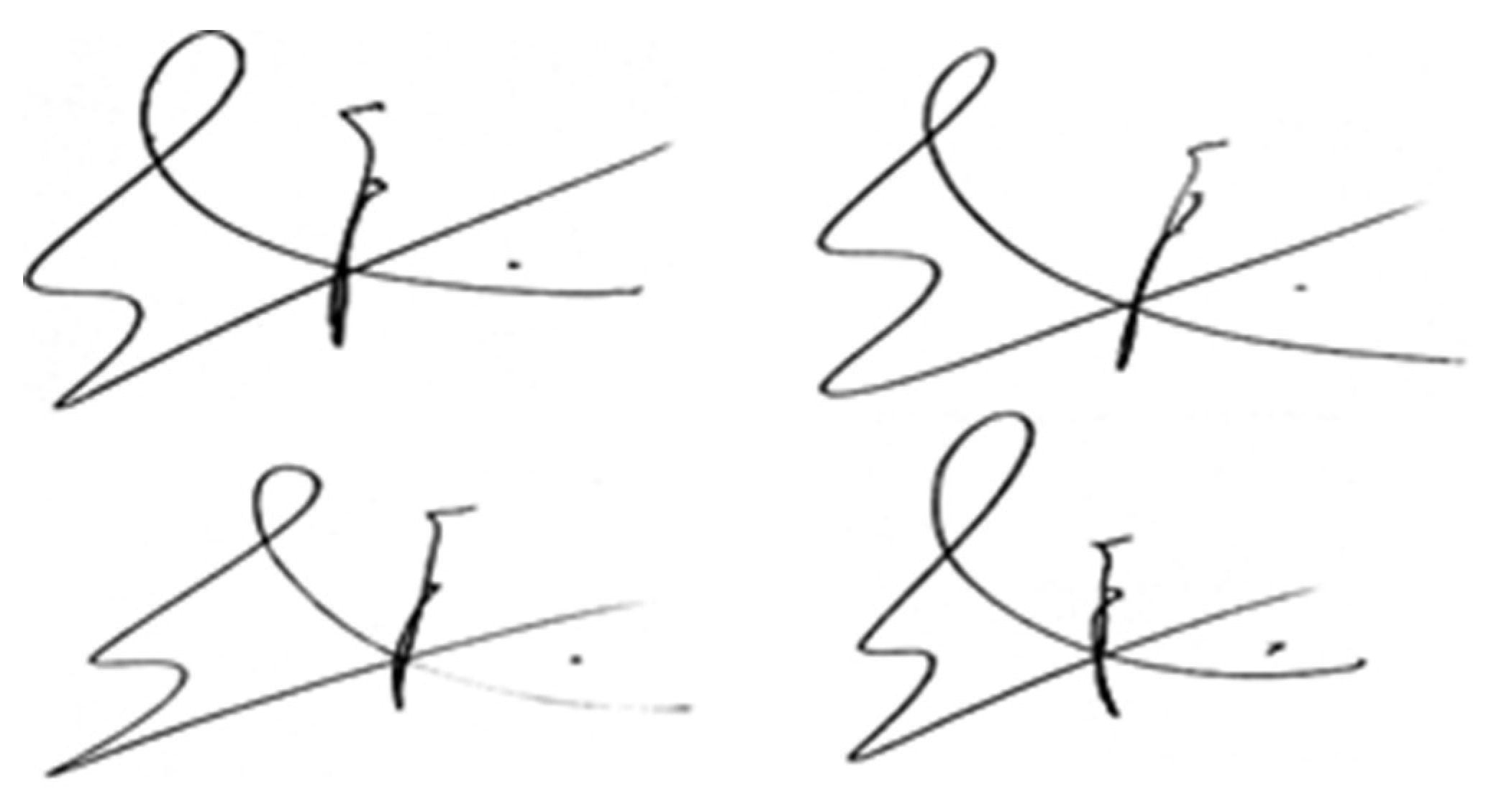

Figure 1 shows several signature patterns for the same person.

Any signature verification system aims to confirm a person’s identity utilising handwritten signature. This system utilises specific features such as width and height to recognise a person. Thus, as stated by [

8], the most usually utilised and recognised means of establishing a person’s identity, both legally and socially, is the signature verification system. Furthermore, Jagtap et al. [

9] noted that signature verification systems constitute a fundamental and effective way to differentiate between a genuine and forged mark.

The most popular and least extreme biometric method in society is still signature verification, even though many previous studies [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] have indicated that it is challenging. This is because handwritten signatures contain special letters and symbols that make them unreadable and obscure the signer’s behaviours.

The feature extraction and classification stages may affect how offline signature verification systems perform. Many studies such as [

9,

15,

16] confirmed the importance of the feature extraction phase in facilitating the distinction between original and forged signatures.

The provision of critical features improves the accuracy and capabilities of signature verification systems. However, features that are extracted from signature images during the feature extraction stage still have many problems related to quality, significance, and quantity. This was confirmed by previous studies [

17,

18,

19,

20] which emphasises the need to improve the feature extraction stage to produce a set of features that may assist classifiers in signatures verification.

Given that, the objective of our study is to establish an offline system for verifying signatures by employing a hybrid approach to extract features within signature images and use machine learning and deep learning classifiers to determine whether they are genuine or not. This is done to ensure that a range of classifiers may perform better when using the hybrid approach.

1.1. Contributions and Novelty

The signature process is considered an important step for ensuring the security of organisations data and protects this data from unauthorised access or infiltration. The use of offline handwritten signatures as a biometric human identification method has increased during the last 10 years. Despite the importance of this technology, it is not an easy task. The challenge in implementing such a system is that no one can sign the same signature repeatedly.

Also, we are interested in the characteristics of the dataset that could have an impact on the model’s performance. We accomplish this by first identifying the most critical features in the signature image using the Features from Accelerated Segment Test (FAST), and then using the Histogram Orientation Gradient (HOG) to extract these features. As a result, a specific set of features that may enhance the signature classification process and identify the forger will be generated through the feature extraction process.

To be able to identify forgeries and safeguard data and people’s rights against theft or fraud, the signature verification system still requires a great deal of work and development. Meanwhile, the signature verification system still needs additional improvements to handle all kinds of signature variations and modifications that depends on the physical state of the signer. Therefore, it is essential to enhance the feature extraction stage, which is seen to be the most crucial step in offline signature verification, to develop a model that can more effectively and efficiently detect and identify both fraudulent and original signatures.

The study’s primary contributions are as follows:

1. Developing a hybrid feature extraction method for a signature verification model that incorporates the FAST and histogram of orientated gradients (HOG) algorithms. According to the study, the HOG features extraction algorithm may be used to overcome the limitations of feature extraction by using a specific cell size for a specific number of extracted features. In terms of classification, this algorithm works well. We believe that this hybrid model can improve verification precision without requiring changes to the system parameters for each contributor. A more adaptable training process and, thus, communication with a significant number of writers will be made feasible by (FAST-HOG).

2. Enhancing the hybrid model by collaborating with a low-complexity classifier, as it possesses a robust feature set.

3. Utilising three classifiers from deep learning and machine learning which helps in verifying the significance of the hybrid method we implemented in feature extraction. This is due to the fact that the performance evolution of the three classifiers will demonstrate that the hybrid method developed in this study can enhance the performance of various deep learning and machine learning classifiers.

2. Research Background and Literature Review

The efficiency of a verification model is determined by the characteristics it employs. Numerous studies have been conducted on offline signature verification, which employs a diverse array of feature sets to execute the model. Geometric data, topology, structural data, gradient, and concavity bases are shared by the majority of the studies [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. For instance, Ferrer et al. [

21] suggested a solution that incorporates a diverse array of geometric attributes that are itemised in the signature envelope specifications and the stroke patterns. Subsequently, the verification process implemented the hidden Markov model, SVMs, and Euclidean distance classifier.

To increase the model’s classification efficiency, it has been common practice to combine a number of characteristics. For instance [

26], employed a grey value distribution and minute information in addition to the directional feature. The authors used the pixel distribution in the thinned signature strokes to produce a 16-directional feature. Because there are so many different kinds of features to extract, the procedure is costly. It is clear that calculating instant information in addition to the 16-directional feature is computationally costly because the model is used for practical systems.

There are a number of systems have been developed with the goal of improving offline signature verification. For example, Alsuhimat and Mohmad [

27] recently developed a technique for signature verification using HOG as a features extraction method and LSTM as a classifier. This method was applied to the datasets USTig and CEDAR, and it produced accurate results of 92.4% and 87.7%, respectively.

Moreover, Subramaniam et al. [

28] implemented CNN to improve signature forgery detection; this study demonstrated that CNN is more precise and timelier in this regard. In another study, Kumar [

29] implemented CNN to enhance signature verification. The results of this investigation were exceptional, with an average error rate (AER) of 3.56 on GPDS synthetic datasets, 4.15 on CEDAR datasets, and 3.51 on MCYT-75 datasets. The signature was validated by Jindal et al. [

10] using two machine learning techniques: support vector machine and decision tree). In contrast to previous endeavors, this investigation demonstrated that both algorithms executed extremely well.

This work also supported Jagtap et al. [

18]’s use of CNN to improve signature verification and forgery detection, demonstrating CNN’s utility in identifying forged signatures and establishing an offline signature verification system. Furthermore, Ajij et al. [

30] enhanced offline signature verification by employing SVM as a classifier with simple combinations of border pixel directional codes. The suggested feature set yields exceptional results that are corroborated by experimental data and may be beneficial in real-time applications.

ZulNarnain et al. [

31] have developed a method for signature authentication by checking the side, angle, and perimeter of triangles that are generated after triangulating a signature image. The Euclidean classifier and the voting-based classifier were employed to classify the data. Pixel surroundings [

36], grey value distribution [

37,

38,

39], directional flow of pixels [

33,

34,

35], and curvature [

32] have been the subject of published research. Additional articles that demonstrate graphometric characteristics may be located in the literature [

40]. To investigate the upper and lower signature envelopes, the authors of [

41] introduced a shape parameter known as the chord moment. Chord moment-based features were incorporated with a support vector machine (SVM) to verify signatures.

Serdouk et al. [

42] examined feature extraction techniques that are not associated with directed distribution. The longest routes, as well as the three fundamental diagonal directions—horizontal, vertical, and vertical—have all been taken into account. A directional distribution-based longest-run feature is combined with gradient local binary patterns (GLBP) to expand the feature set in this scenario. As a consequence, they incorporated gradient and topological characteristics. The topological attribute will be determined by the length of the longest line of pixels. A Local Binary Pattern (GLBP) is employed to collect gradient information within the vicinity. The computational cost of GLBP for each pixel in the signature image may be relatively substantial. They suggested a verification system that was based on the Artificial Immune Recognition System.

Furthermore, a verification method that is based on templates was proposed [

43]. They offer a method that utilizes grid templates to encode the geometric composition of signatures. The results of these methods indicate that, despite the development of a multitude of methodologies or recognition systems, there is still significant potential for enhancing robustness and accuracy. Furthermore, there is an opportunity to provide a feature set that is both robust and efficient, thereby enhancing the performance of a classifier with minimal effort. It will be beneficial if the feature set can be easily identified from the signature photographs.

Table 1.

Some of the Current Methods for Offline Signature Verification.

Table 1.

Some of the Current Methods for Offline Signature Verification.

| Source |

Features |

Classifiers |

| Kovari & Charaf [23] |

Width, highet, area, etc. |

Probabilistic model |

| Jiang et al. [38] |

Improved GLBP and GLBP |

SVM |

| Kumar & Puhan [41] |

Upper and lower Envelope; chord moments |

SVM |

| Guerbai et al. [32] |

Curvelet transform |

RBF-SVM, MLP |

| Pham et al. [25] |

Geometry-based features. |

Likelihood ratio |

| Serdouk et al. [42] |

Gradient Local Binary Patterns (GLBP) and LRF |

k-NN |

| Pal et al. [44] |

Uniform Local Binary Patterns (ULBP) |

Nearest Neighbor |

| Loka et al. [45] |

Long range correlation (LRC) |

(LRC) SVM |

| Zois et al. [43] |

Lattice arrangements Pixel distribution |

Decision tree |

| Muhammad et al. [46] |

Local pixel distribution GA |

SVM |

| Batool et al. [47] |

GLCM, geometric features |

SVM |

| Ajij et al. [30] |

Quasi-straight line segments |

SVM |

| Tahir et al. [48] |

Baseline Slant Angle, Aspect Ratio, Normalized Area, Center of Gravity, and line’s Slope. |

Artificial Neural Network |

| Lopes et al. [49] |

Straight lines, edges, and objects. |

CNN |

| Proposed Method |

Magnitude, angle of the gradient, orientations of the gradient, strongest points. |

LSTM, SVM, and KNN |

According to previous research, developing offline signature verification system is still required. This is due to the fact that the model must be trained on a greater number and quality of datasets, as well as the inclusion of features extracted from a variety of scenarios. Additionally, the system must employ a greater variety of algorithms. There is also a need to enhance the features extraction phase, because it is essential for enhancing the efficacy of the classification process. The results of these strategies indicate that, though numerous methodologies or recognition models have been developed, there is still significant potential for improved robustness and accuracy. Furthermore, there is an opportunity for providing a feature set that is both robust and efficient, thereby classifier’s performance maybe improved with less effort. It can be beneficial if the signature photographs can identify the feature set.

3. Materials and Methods

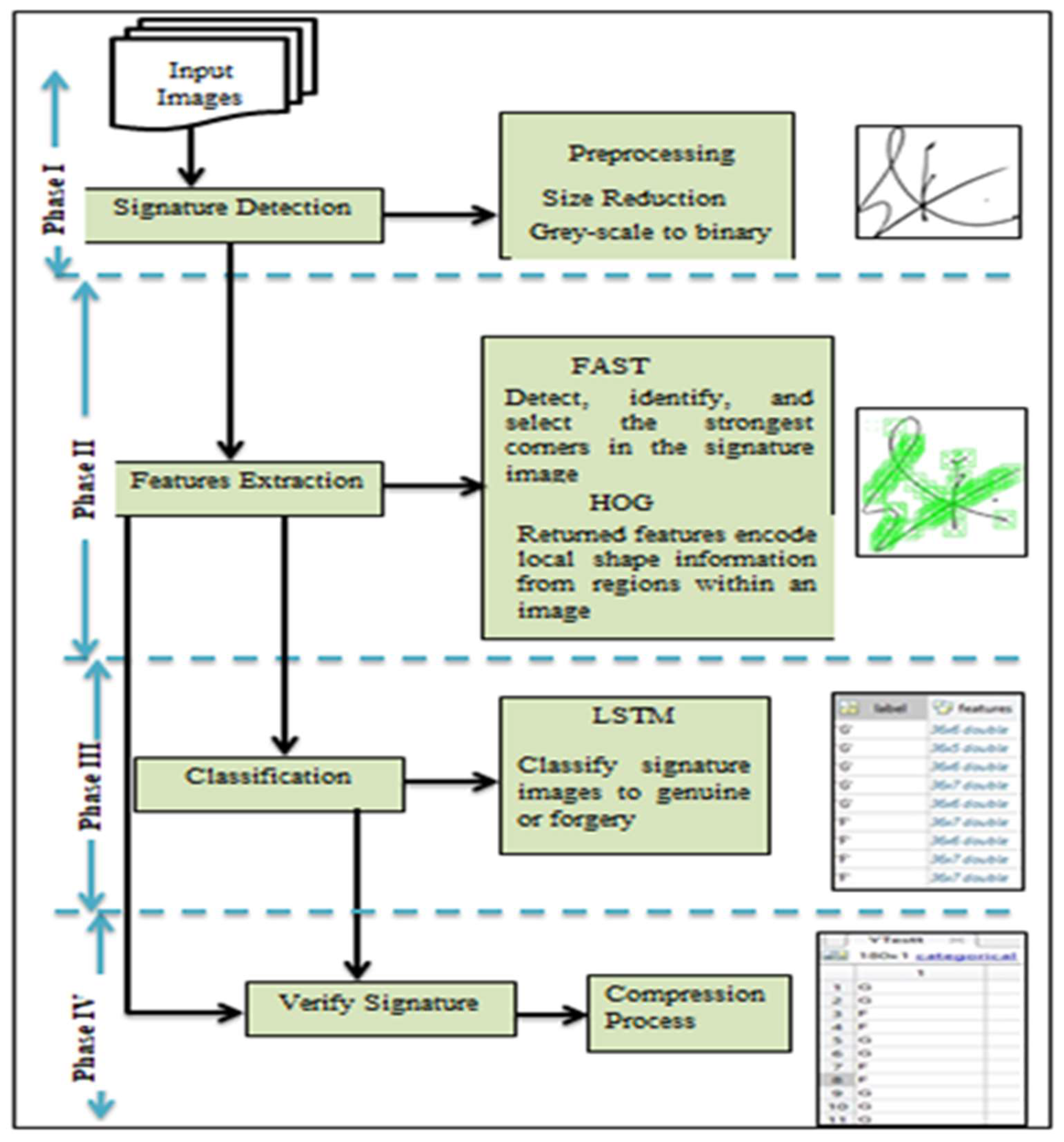

Verifying individuals’ signatures and detecting the forged and genuine signature is a challenging task that may lead to low system performance, preventing it from being deployed in real-world applications. In

Figure 2, a simple framework is introduced to describe the overall evaluation process of the proposed model. The framework contains four key phases, which are discussed sequentially. These are signature detection phase, feature extraction phase, classification phase and the verification phase. The signature detection phase is the first task in the process. In this step, the image processing was done using standard databases. In the second phase, the features extraction phase was improved through combining FAST algorithm with HOG algorithm to detect the most significant features in each signature image, and then the extracted feature result was saved as a vector. Then Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) were employed to classify the extracted features into two groups (Genuine and Forgery). Then, the verification process was conducted by comparing the results of three classifiers with a set of test images. The corresponding flowchart of the proposed model is shown in

Figure 2. Finally, the forged signature was detected, and model performance was calculated.

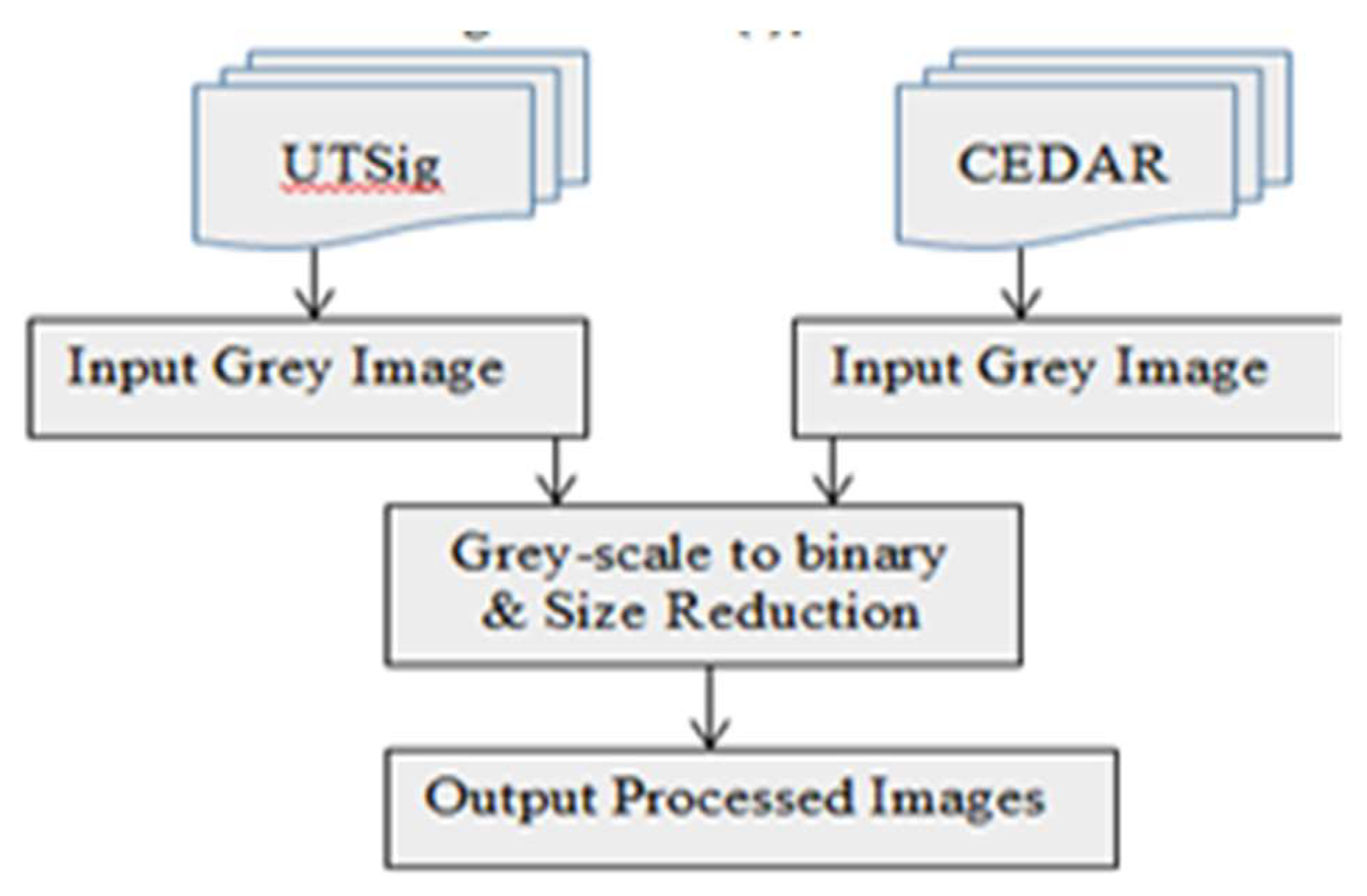

3.1. Phase I: Signature Detection

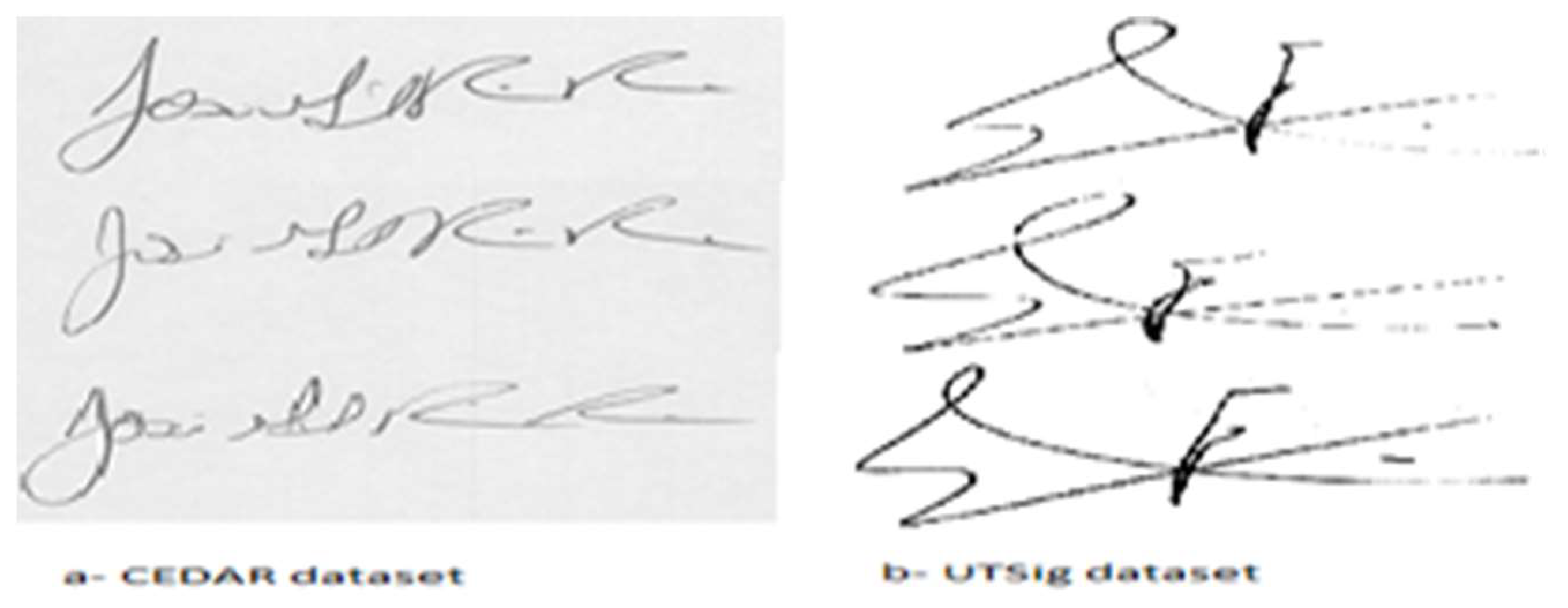

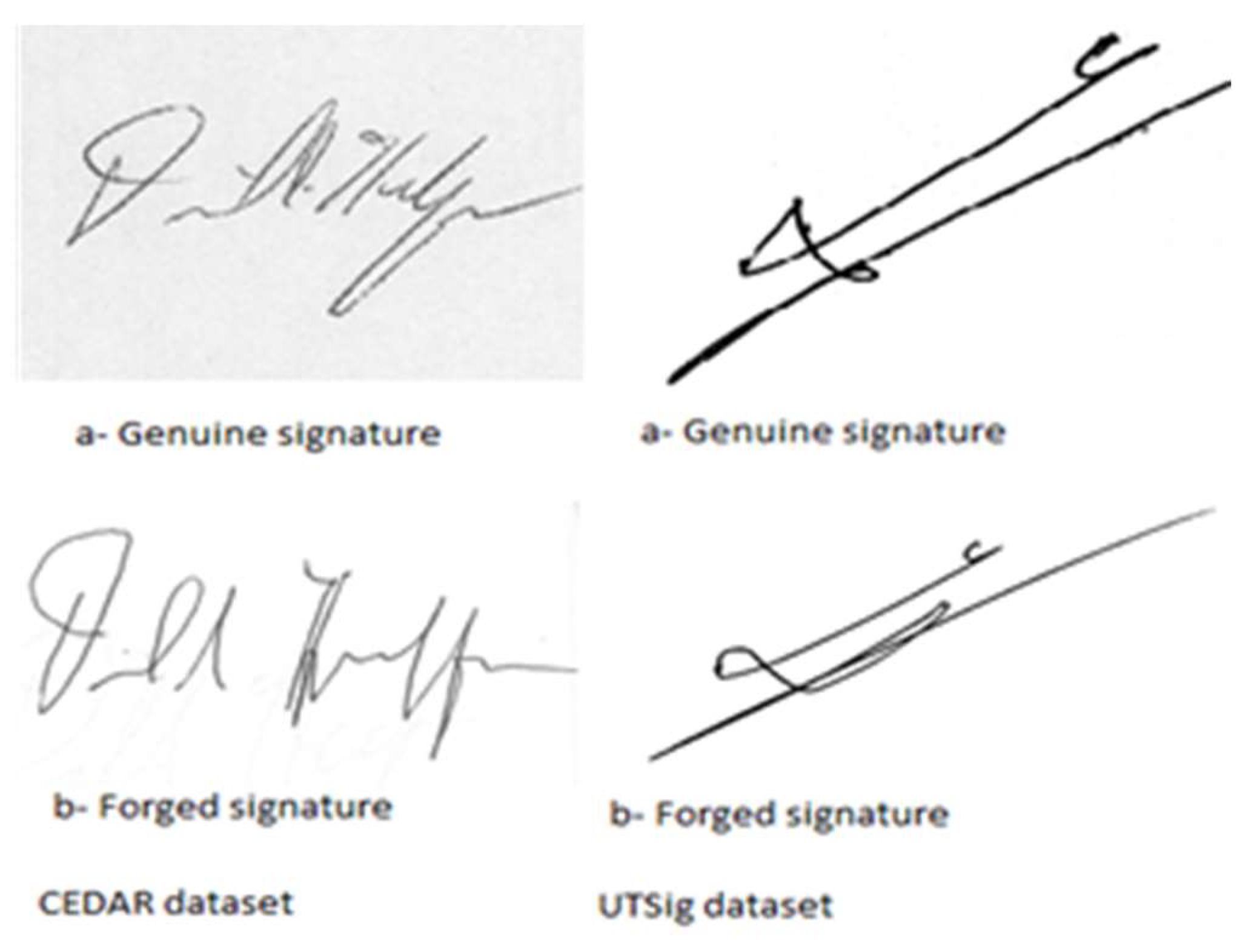

In our study, to ensure the proposed model performance, two different datasets were used, UTSig and CEDAR as shown in

Figure 3. So, in this phase factors such as background complexity, image colour, illumination, and noise should be considered first. The quality of the produced image can be enhanced by preprocessing.

This step makes the subsequent phases of feature extraction, classification, and verification easier. In this study, two types of signature datasets were used UTSig that has grey signature images in different sizes and CEDAR that has colour signature images in different sizes. Both the efficiency and the accuracy of the process were improved by searching for the signature region instead of the whole image. Therefore, the exact boundary of the signature area was obtained, significantly facilitating the accurate localisation of feature points [

50].

3.2. Pre-Processing

Preprocessing the signature is the quickest and most crucial step in the offline handwritten signature verification paradigm. In rare circumstances, the raw signature may have additional pixels called noises or might not be in the correct format, making pre-processing necessary. When a signature is appropriately preprocessed, forgery detection and signature matching produce superior results. Binarization, noise reduction, thinning, and orientation are all parts of the pre-processing [

51].

Poor lighting or inappropriate settings in the gain sensor can cause variations in the image contrast. Thus, image contrast processing is needed to compensate for the difficulties in obtaining the image. By doing this, images are clearer and noiseless.

Extending the dynamic range throughout the whole visual spectrum stretches the pixel values of high-contrast and low-contrast images, respectively. In this research, the pre-processing was done in two steps for UTSig dataset and CEDAR dataset: i) Grey-scale to binary and ii) Size Reduction, as demonstrated in

Figure 4.

3.2.1. Grey-Scale to Binary

The input signature in MATLAB needs to be in grayscale or binary, or no output will be produced. A binary picture can only have 1 and 0 values, or black and white, respectively [

52]. There must be a defined threshold in order to obtain the binary image of any signature. The threshold value might range from 0 to 1 depending on the method used [

53].

Crude thresholding is the foundation of binarization. All pixels in the input picture whose brightness is below the threshold level have a value of 0 (black) in the output binary image, while all other pixels have a value of 1 (white). There are just two intensity levels in the produced picture (values 0 and 1). A binary image serves as the output image. Consequently, it transforms the grayscale picture to a binary image where the value 1 (white) is assigned to every input pixel with brightness greater than level and the value 0 to every other pixel (black). This range relates to the signal levels that the image’s class is capable of supporting.

Accordingly, a level value of 0.5 indicates an intensity rating that falls in the middle of the class’s minimum and maximum values.

The MATLAB function Image= im2bw (I); was utilised.

3.2.2. Size Reduction

A low-contrast or high-contrast image’s pixel values can be stretched by extending the dynamic range throughout the whole image spectrum. To determine the limits of picture contrast stretching, utilise Matlab Simulator’s “stretchlim” function. The size of the picture is then shrunk to lower the signature image resolution. This size reduction serves to simplify the mathematics used in the training process. The images are being resized to 128 × 128 pixel using “imresize” function in Matlab simulator.

The MATLAB function Image = imresize (I, [128, 128]), was utilised.

3.3. Phase II: Features Extraction

The goal of the signature verification system is to differentiate between genuine and fake signatures. Furthermore, there are differences and contrasts in the original signature due to a number of factors, including the fact that the signature does not start and stop at the same moment. Comparing and differentiating signatures, even for the same individual, can be difficult since the relationship between the letters or symbols in a signature varies each time it is created.

In a biometric system, the extraction of features is regarded as the second step. For the purpose of comparing biometric samples, identifying, and authenticating individuals, this step entails the procedure of recognising and detecting a variety of properties in the picture, whether they are fingerprint, signature, or other features like width, length, and number of pixels. There are three categories of features that may be derived from signature recognition systems: global features, which include the height to breadth ratio of the signature, the gravity center, and the signature area. The third kind, a geometric feature, embodies both the local and global elements of the signature, whereas the second type is local features, such as crucial points and slant features [

54].

In the feature extraction stage of signature recognition systems, a collection of original sample features is sought for so that user sample features may be compared with them for verification reasons. There are two different kinds of characteristics. The first kind is functional features, which include location, speed, and compression. These characteristics will be employed in online signature verification systems. The second category is parameter features, which may be further broken down into local and global parameters [

8].

According to Bhosale and Karwankar [

55], the step of extracting the characteristics is largely responsible for the efficacy and efficiency of signature recognition systems; hence, efficient and quick procedures must be utilised at this point. Moreover, the extracted attributes must be able to differentiate between authentic and fake signatures.

A collection of hidden parameters in the signature picture is extracted as part of the feature extraction procedure, which is predicated on reducing the original signature image’s size. To make it simpler to tell the difference between the authentic signature and the copy, these characteristics were carefully chosen. These features consist of:

Local shape descriptors: reflect a large variety of global factors, including context form and high-pressure sites [

56]. Chain coding is the act of coordinating a starting point and figuring out the directions of subsequent points till you return to the start point [

34]. Graphometric characteristics: reflect a group of inherent properties from an individual handwriting pattern, which may be applied for signature detection, such as: curvature, pressure, and histogram features comprising the number of pen pixels in the circular sector [

57]. Interior stroke distributions: this attribute describes the method of computing the number of strokes that dispersed in the image [

58].

3.3.1. Features from Accelerated Segment Test (FAST)

The Features from Accelerated Segment Test (FAST) algorithm takes a unique approach by selecting a small number of points inside the interest range and excluding unhelpful points. This strategy that is used by this algorithm is different from the ones that were used by previous algorithms. It is built on an automatic learning strategy that adjusts to processing [

6].

An interest point in an image is a pixel that has a precise location and can be reliably recognised. Rosten and Drummond first proposed the FAST method for this purpose [

59]. Photographs with high local information richness and interest spots should ideally be repeated. Interest point detection has applications in tracking, recognising objects, and matching of pictures. The concepts “interest point” and “corner detection” are frequently used interchangeably in literature; therefore they are not entirely novel concepts. The SUSAN corner detector, the Harris & Stephens corner detection technique, and the Moravec corner detection algorithm are a few of the well-known algorithms. The objective of the study on the FAST method was to develop an interest point detector for use in real-time frame rate applications, such as SLAM on a mobile robot, which have limited processing resources [

59].

The FAST algorithm was introduced as a novel corner detecting approach in 1998. Moreover, FAST needs a specific set of requirements to permit match feature points from corner detectors. These requirements are as follows [

60]:

Consistency: According to this criterion, the detected points should be labelled as being insensitive to any noise variation, which means they should remain stationary when several photos of the same scene are captured.

Accuracy: According to this criterion, corners should be detected as closely as possible to their actual locations.

Speed: According to this criterion, detection must occur as rapidly as possible, with the process of detecting corners being useless unless they move swiftly.

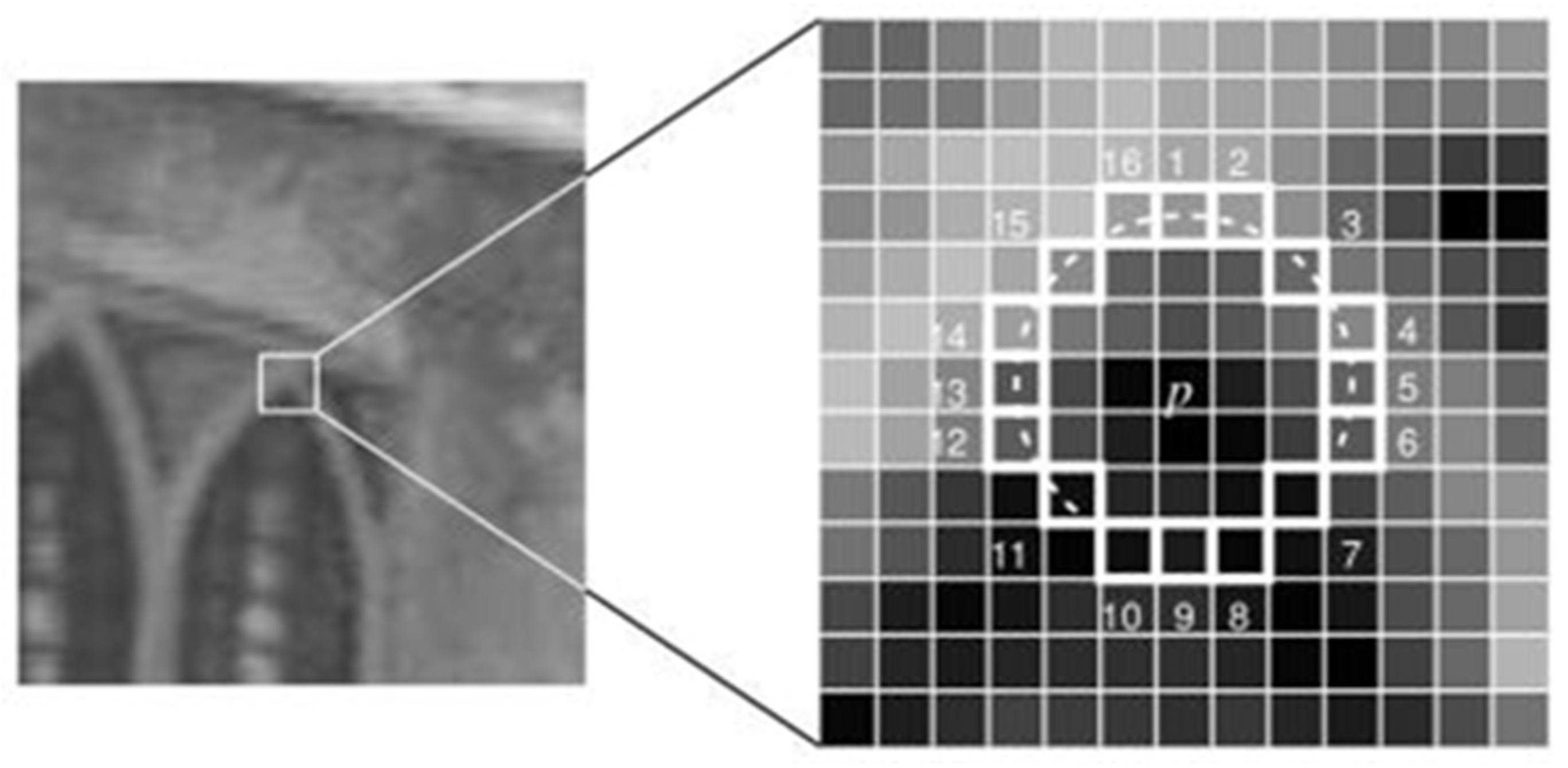

Figure 5.

Demonstrating the interest point under test and the circle’s 16 pixels [

59].

Figure 5.

Demonstrating the interest point under test and the circle’s 16 pixels [

59].

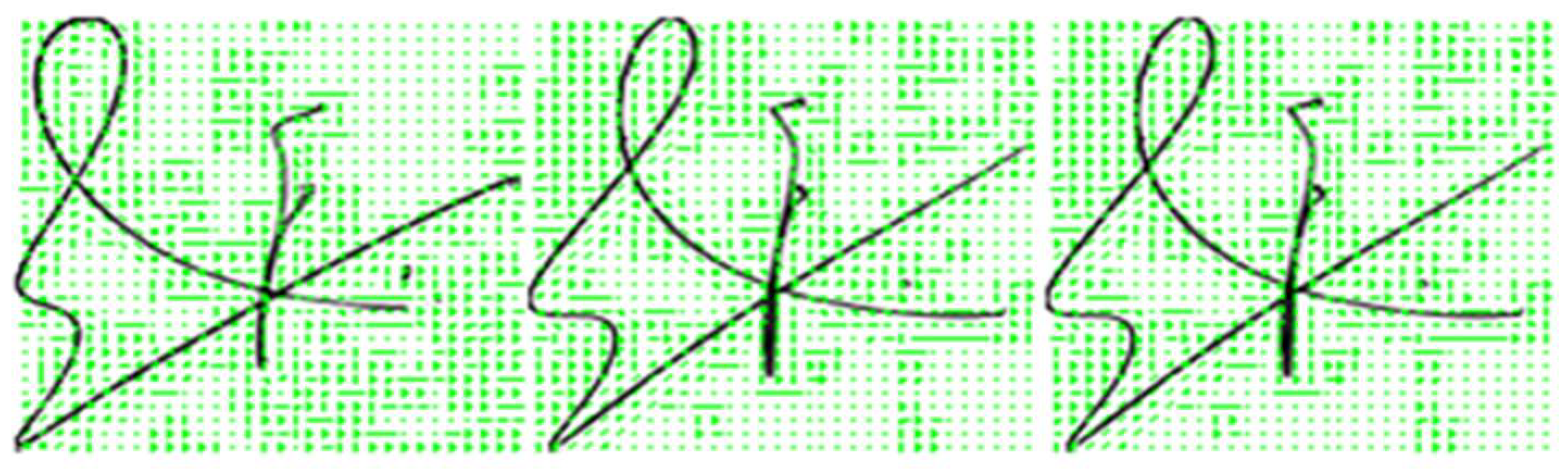

In this study, FAST was used to find the strongest points in the signature images, as this algorithm was used with the aim of extracting the features from the most important areas in the signature image, as this process aims to extract the most important influencing features and be indifferent to all the features contained in the signature image. In addition, the use of this algorithm helps reduce the implementation time and enhance the performance of the proposed model, by selecting the best features that contribute greatly to helping in the signature verification.

Figure 6 demonstrates the number of selected points in the signature image.

The code below gives the procedure for the FAST algorithm in this research.

| Algorithm 1: Selecting Strongest Points in image |

Input: Pre-processing signature image.

Output: Image with selected strength point. |

| Step 1: Define dataset name |

| Step 2: Determine the dataset direction and its content. |

| Step 3: Define counter to concatenate each signature image for one person |

| Step 4: Identify variable equal number of signatures |

| Step 5: Identify for loop (i) and do. |

Step 6: Identify variable (C) equal features detection from signature image.

Step 7: Identify variable (S) equal most importance features in signature image (36 features) |

| Step 7: save signature image with selecting features. |

| Step 7: End i |

3.3.2. Histograms of Oriented Gradients (HOG)

It has been demonstrated that Histogram of Oriented Gradient (HOG) descriptors are useful for detecting objects, particularly humans [

61]. These traits have been used to a number of issues, such as pedestrian tracking and recognition [

62], hand gesture translation for sign language and gesture-based technology interfaces, face recognition [

63], and body part tracking [

61]. In non-human-centric tasks like classifying vehicle direction, a challenge pertinent to autonomous cars, HOG descriptors have also been applied [

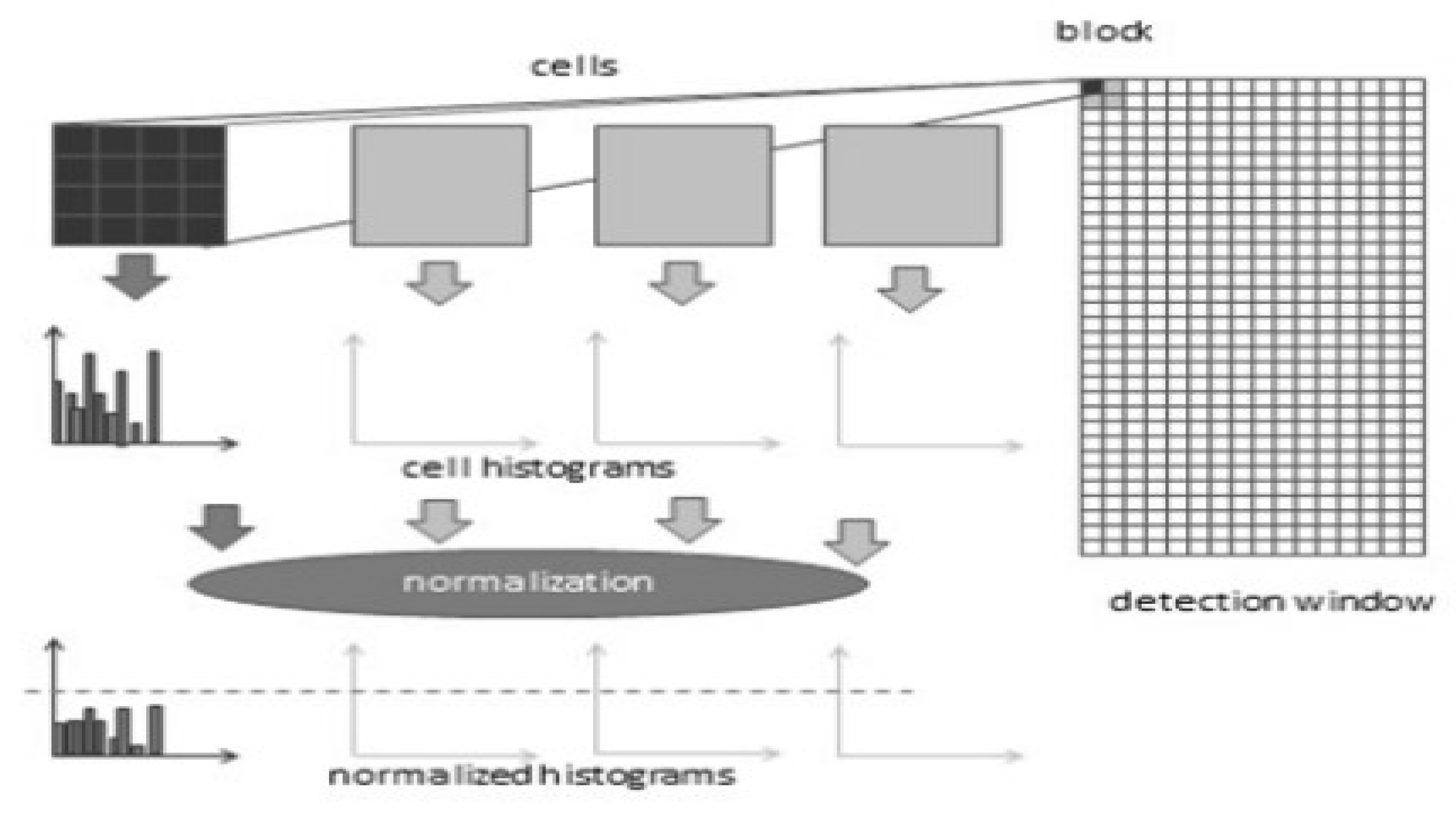

64]. Yet, in order to acquire descriptions of regions that are only localised to the topic of detection, these classification tasks employ a sliding window technique.

A local descriptor is the histograms of directed gradients. A similar approach defines the gradient orientation in discrete parts of a picture before compiling the data from each sector into a single vector. The image has been divided into cells by Dalal and Triggs [

65] in 2005; each cell has an area of 8x8 pixels. Hence, the HOG descriptor’s technique entails first describing each cell independently by computing the vectors that each cell’s histogram of oriented gradients (each vector has 9 bins) represents before concatenating them into a single vector. They have L2-normalized all 2x2 cells (this set was referred to as a block) to boost tolerance to changes in light and illumination conditions:

where V is the normalised vector, v is the non-normalized vector, and is a tiny constant; the result is the normalised vector. A feature vector with 36 components is used to represent each block. The set of normalised vectors from each block, but with a 50% cell-to-cell overlap, forms the final HOG vector that will serve as the classifier’s input. Take into account a 7x15 block, 64x128 pixel detect window. 3780 components are obtained by assembling the normalised vectors for each block into a single 1-D vector (36 x 7 x 15 = 3780).

Figure 7.

Demonstrates the HOG algorithm implementation.

Figure 7.

Demonstrates the HOG algorithm implementation.

The HOG descriptor approach hypothetically documents the introduction of angles in precise regions of a photograph or location of interest (ROI). The primary application of the HOG descriptor is the following, as illustrated in

Figure 3.6: The image is initially divided into tiny, related areas (cells), and a histogram of angle directions or edge orientations for the pixels inside the cell is computed for each region. After that, the gradient orientation that was acquired is implemented. After the discretization of each cell into a precise container, the pixel of each cell adds a weighted angle to its corresponding precise canister. Subsequently, adjacent cells are grouped into groups based on the spatial region. Ultimately, the normalized collection of histograms communicates with the piece histogram, and the set of these square histograms communicates with the descriptor, which serves as the foundation for histogram collection and normalization [

66].

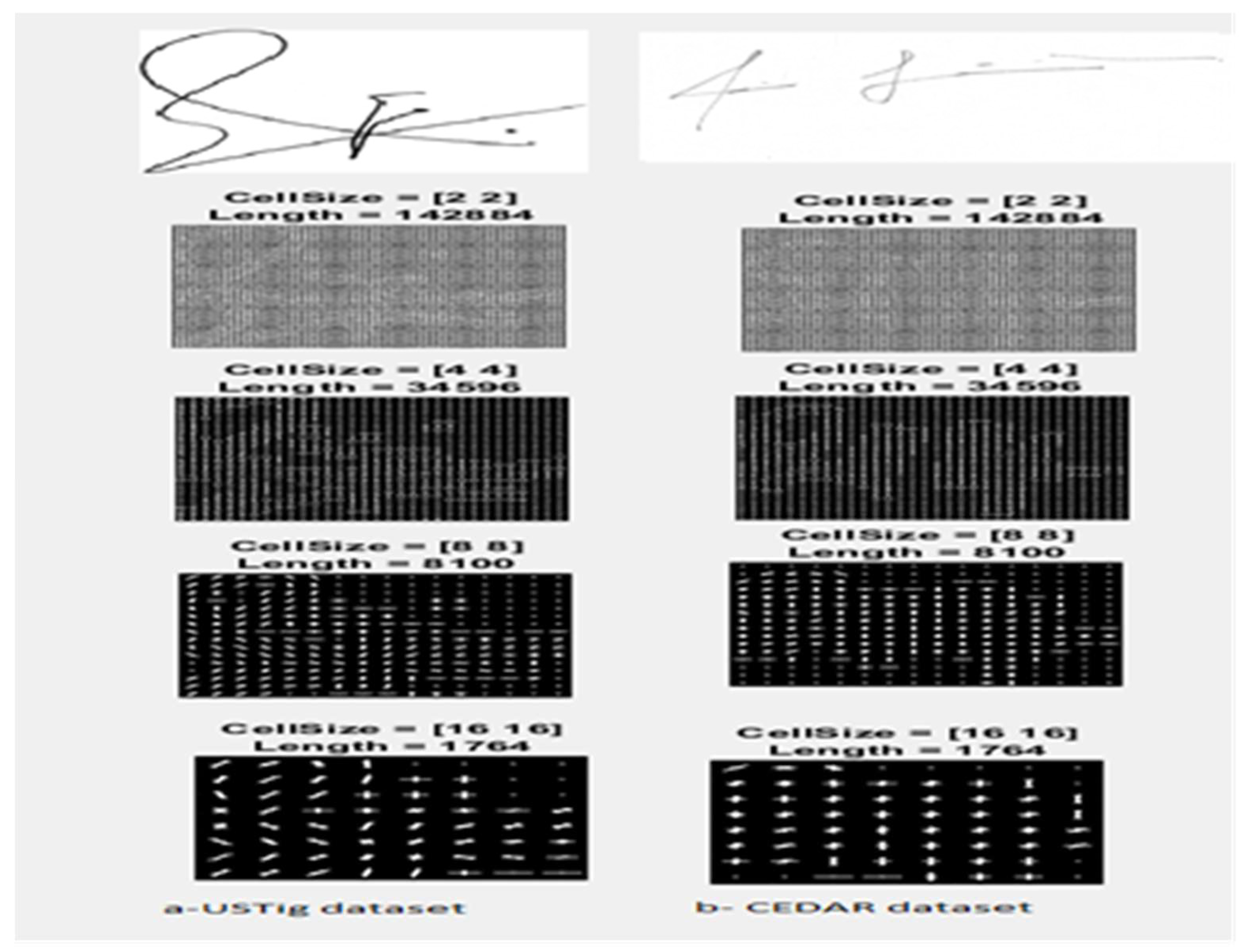

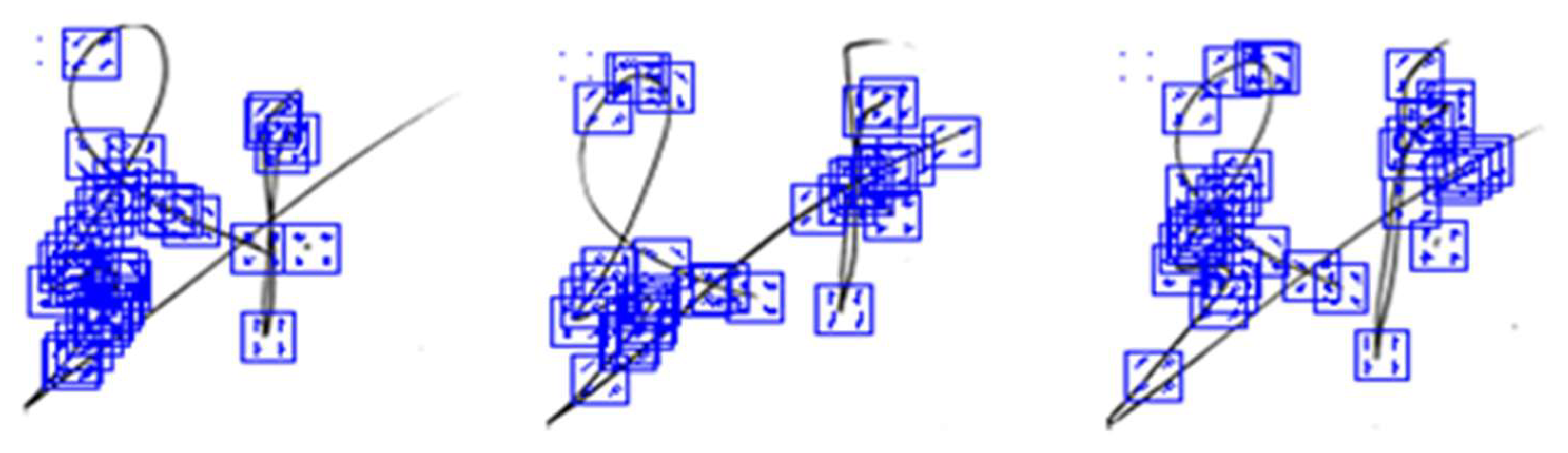

HOG was applied in two distinct methods for this study. It was utilised independently for the first time as an algorithm to extract characteristics from a collection of signature photographs, and the proper cell size for the collection of images used in this research was investigated. The HOG is defined in this paper as having a block size of [4x4] pixels. Consequently, the overall length of the feature vector used to define each signature picture sample is 34596. Two offline handwritten signature datasets with a range of cell sizes are shown in

Figure 8 and were used in this study to further explain how the HOG was applied to the offline signature.

According to Abbas et al., the number of depicted gradients and directions is becoming increasingly easily observable when the cell size is small [

67]. As the cell size number of the HOG parameter increases, the gradient and directions will progressively decrease.

With cells varying in size from 2 to 16,

Figure 8 shows how HOG affects the offline signature pictures.

Figure 8 displays the best cell size for both UTSig dataset and CEDAR dataset is [4x4], where this size has 34596 features vector length for each single image. Then, after select the suitable cell size the features was extracted from the signature images as shown in

Figure 9.

The code below gives the procedure for the HOG algorithm in this research.

| Algorithm 2: HOG |

| Input: Preprocessing Signature Images |

| Output: Features Vector |

| Step 1: Define dataset name |

| Step 2: Determine the dataset direction and its content. |

| Step 3: Define counter to concatenate each signature image for one person |

| Step 4: Define two arrays x for label image and y for image features. |

| Step 5: Identify For loop (t) to read and process each signature image |

| Step 6: Read each image in the dataset |

| Step 7: returns the greyscale input image’s HOG features, II. N is the HOG feature length, and the features are returned as a 1-by-N vector. The local shape information from regions inside the image is encoded by the returning features. |

| Step 8: Label is G when signature is genuine and F when signature is Forged |

| Step 9: Identify If (mod(t, number of signature images for each person)==0) and do the following |

| Step 10: Move to the next signature image for the same person |

| Step 11: save the extracted features and label for the first image in .mat file |

| Step 12: Prepare for dealing with the next signature image |

| Step 13: End for if |

| Step 14: End for t |

| Step 15: Define the direction of the features extraction files |

| Step 16: Define variable for signature image labels in mat file. |

| Step 17: Define variable for signature image features in mat file. |

| Step 18: Define variable to use as counter for total of .mat file. |

| Step 19: Define variable as the number of rows in each .mat file |

| Step 20: Identify location of the .mat files |

| Step 21: Count the number of .mat file to use it in the next for loop |

| Step 22: Load and read each .mat file |

| Step 23: Identify For loop (r) and count the number of rows in each .mat file |

| Step 24: Move from row to another within the .mat file |

| Step 25: Save the label of .mat files rows |

| Step 26: Save the features of .mat files rows |

Step 27: End for r

Step 28: Clear file name |

| Step 29: Move to the next .mat file |

| Step 30: End for j |

For the second time, HOG algorithm was used in different way from the first time, where at this time HOG algorithm extracted features from some points in the signature image not from whole the signature image, this process contributed in enhance the quality of extracted features and reduce the implementation time, due to that at first time there are 34596 features were extracted from the signature image, while through using FAST algorithm to detect the strongest points in the signature image, then use HOG algorithm to extract features from these strongest points provide 36 features, despite the features number in this way is less than the features produced from the first time, but these features are more effective because they are chosen depend on most effective points in the signature images.

Figure 10 show the result for combine Fast algorithm with HOG algorithm to extract most effective features.

The code below gives the procedure for combine FAST algorithm with HOG algorithm in this research.

| Algorithm 3: Feature Extraction from selected points |

| Input: Preprocessing Signature Images |

| Output: Features Vector |

| Step 1: Define dataset name |

| Step 2: Determine the dataset direction and its content. |

| Step 3: Define counter to concatenate each signature image for one person |

| Step 4: Define two arrays x for label image and y for image features. |

| Step 5: Identify For loop (t) to read and process each signature image |

| Step 6: Read each image in the dataset |

| Step 7: Detect features and select the strongest points using FAST. |

| Step 8: Returns extracted HOG features from signature image based on selected points. |

| Step 9: Label is G when signature is genuine and F when signature is Forged |

| Step 10: Identify If (mod(t, number of signature images for each person)==0) and do the following |

| Step 11: Move to the next signature image for the same person |

| Step 12: save the extracted features and label for the first image in .mat file |

| Step 13: End for if |

| Step 14: End for t |

In both cases, whether when used HOG algorithm for extract features alone or when combine it with FAST algorithm, after features extraction process the result was collected in on vector, where at first step the extracted features save in vector for each user independently, then collected all vectors in one single vectors consist all extracted features for each image with label (G for genuine or F for forgery) for each single signature image.

3.3. Phase III Classification

The features were classified in this study using a diverse array of techniques, including support vector machines, extended short-term memory, and K-nearest neighbor.

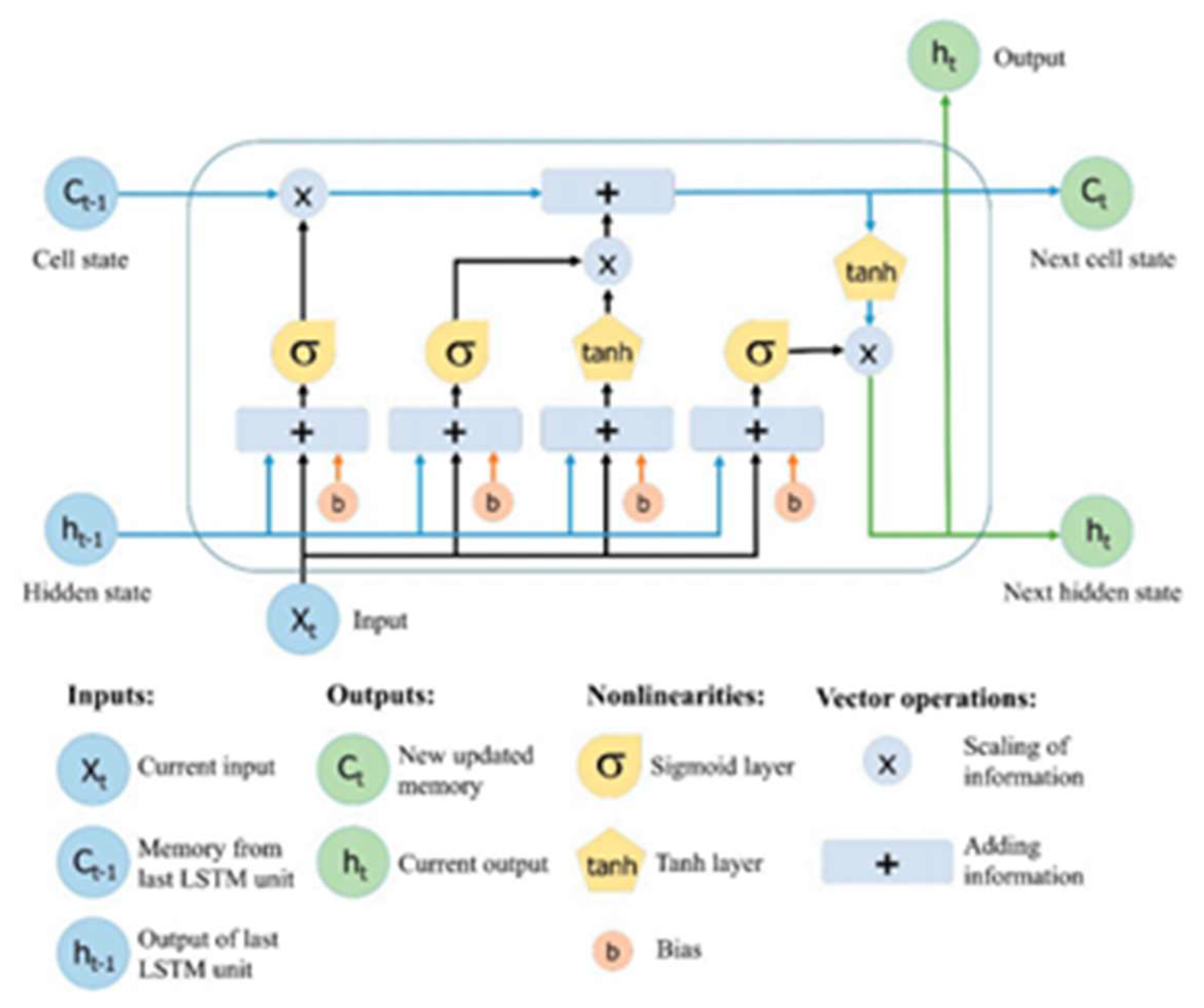

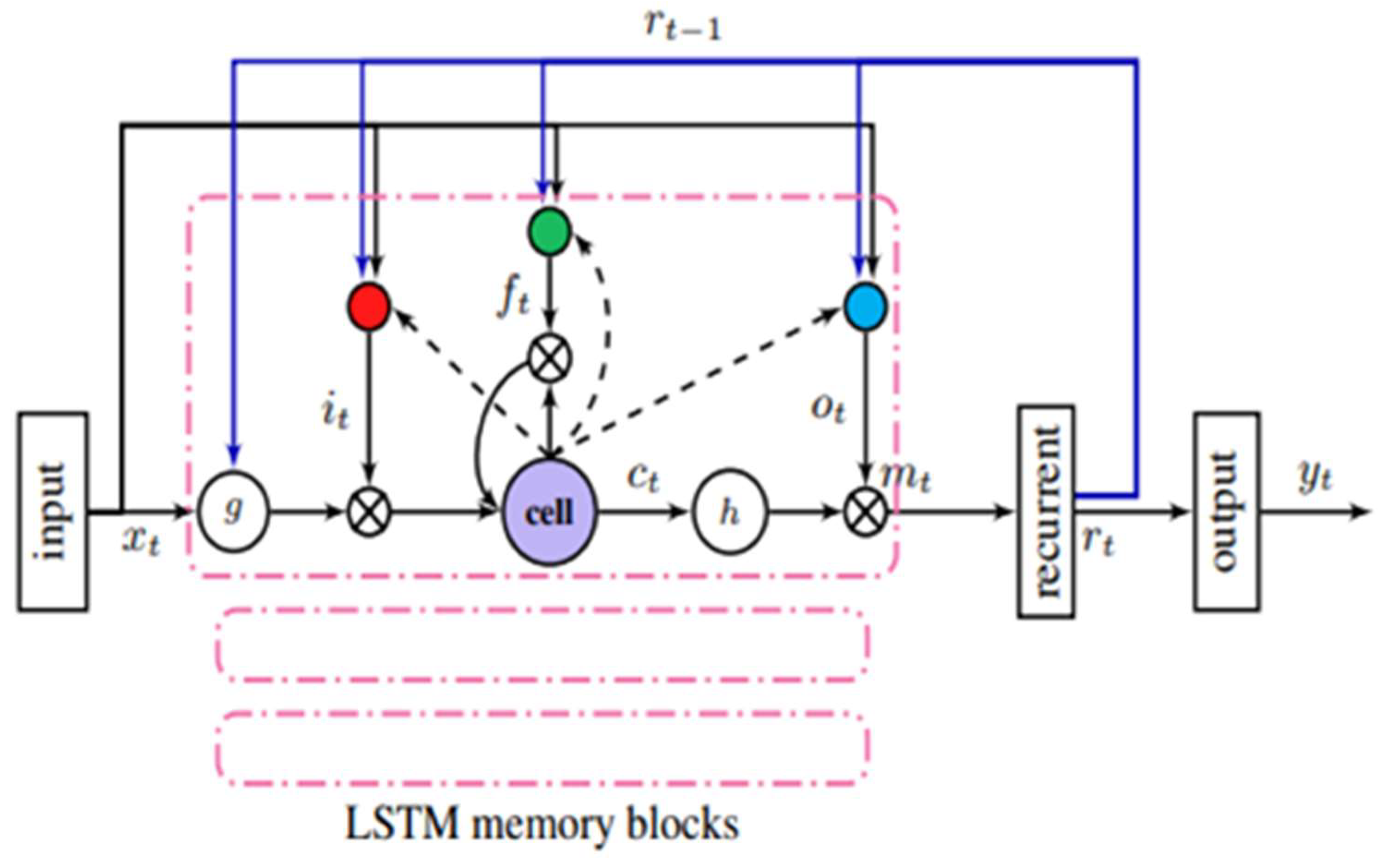

3.3.1. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

LSTM is defined as an artificial recurrent neural network (RNN) structure utilized within deep learning domain. In addition, LSTM has feedback connections, unlike the standard feed forward neural networks, where LSTM can prepare single information (e.g., pictures) and whole arrangements of information (e.g., speech or video) [

68].

A Multi variant of the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) structure for recurrent neural networks has been proposed since its beginning in 1995. Later, these systems have become to be state-of-the-art models for an assortment of machine learning problems. As a result, there is now more interest in understanding the function and significance of the different computational components of LSTM typical variations [

69].

Figure 11.

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network Structure.

Figure 11.

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network Structure.

Uncommonly created RNN nodes called LSTMs are used to maintain long-lasting conditions. Essentially, they consist of three gates that regulate the hub’s input and yield, as well as a self-connected memory cell that is comparable to the traditional RNN node. Every gate might be a sigmoid of the LSTM hub’s input. The main door is an input door that regulates whether the hub may access fresh input.

The moment door could be a disregard entryway which makes conceivable for the hub to reset actuation values of the memory cell. The final entryway is a yield entryway controlling which parts of the cell yield are accessible to the other nodes [

70].

It has been demonstrated that LSTM models outperform RNNs in the learning of both context-free and context-sensitive languages [

71].

For phonetic labelling of acoustic frames on the TIMIT speech database, bidirectional LSTM (BLSTM) networks have been suggested. These networks use the input sequence in both directions to determine the current input [

72].

Figure 12.

LSTMP RNN architecture [

73].

Figure 12.

LSTMP RNN architecture [

73].

In this research LSTM was used to classify the extracted features according to their labels whether genuine or forgery, the LSTM algorithm applied two times, first time using extracted features from HOG algorithm and second times using extracted features from a combine model (FAST algorithm and HOG algorithm), to find the better result between both methods, all LSTM parameters were same at both cases except input size, because this parameter depend on the number of extracted features, where at first time the number of extracted features were (34596), while at second time the extracted features were (36).

The input weights W (InputWeights), recurrent weights R (RecurrentWeights), and bias b (Bias) are the learnable weights of an LSTM layer. The input weights, recurrent weights, and bias of each component are concatenated into the matrices W, R, and b, respectively. The following is how these matrices are concatenated [

74]:

i, f, g, and o denote the input gate, forget gate, cell candidate, and output gate, respectively.

The cell state at time step t is specified by:

The Hadamard product (element-wise multiplication of vectors) is shown by the symbol ⊙. At time step t, the hidden state is determined by:

By default, the lstmLayer function computes the state activation function using the hyperbolic tangent function (tanh), where σc represents the state activation function.

3.3.2. K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)

The most precise evaluations of the diversity of inner characteristics are the foundation of this method of obtaining parameters [

75]. KNN is one of the most prevalent and straightforward classification algorithms. The learning strategy was characterized by the integration of internal collection activities with the preservation of unique vectors and markers of the learning images.

Figure 13.

KNN Classification.

Figure 13.

KNN Classification.

The designation of its k nearest neighbors could be appropriate for this unmarked location. This entity is frequently characterized by the characteristics of its k nearest neighbors through the use of overwhelming part surveys. The parameters are grouped on k=1 based on the power of the parameter that is closest to it. In this instance, only two segments are necessary; consequently, k must be an odd integer. In a multiclass configuration, K may manifest as an odd number. This phase employs the Euclidean distance, a renowned distance equation (5), as a related point separation capability for KNN. This is achieved by converting each image to a vector and removing the fixed-length for true numbers claim:

The k Nearest Neighbor (kNN) algorithm is probably the simplest of all existing classification techniques. It was introduced in the US Air Force School of Aviation Medicine report by Fix and Hodges [

76] as a pattern classification method. It consists of classifying unknown samples based on the closest known samples in the feature space. The closeness measure is often calculated with the Euclidian distance [

77]. Many research works employed the kNN to identify/verify off-line handwritten signatures, in which a questioned signature is classified by assigning the most frequent class among the k closest known signature samples [

78,

79,

80].

3.3.3. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

This classifier is ready to perform signature evaluation based on certain signature attributes [

81]. We applied a classification algorithm to particular features for signature images to train a signature classifier utilising all of the preparation data. During the training procedure, we used all of the preparation data.

The SVM technique was used in the signature prediction outline to classify the input signature image using training processes. The characteristic vectors are the inputs xi. We utilised the Gaussian kernel K to configure the SVM parameters:

From earlier decades to the present, SVM is still considered as the most commonly used classifier in machine learning applications, mainly, in the domain of signature identification / verification [

82,

83,

84,

85]. SVM classifiers has many advantages, mainly, that they are abile to handle high dimensional data and the convergence for a global, unique and optimal solution.

3.4. Dataset

The experimental procedure utilized the CEDAR and (UTSig) datasets.

Figure 14 illustrates that the UTSig dataset contains (115) classifications, which include (27) authentic genuine signatures, (3) opposite-hand forgeries, (36) simple forgeries, and (6) skill forgeries. A distinct, actual individual is designated to each cohort. The signatures of students from the University of Tehran and Sharif University of Technology who enrolled in UTSig were captured at a resolution of 600 dpi and stored as 8-bit Tiff files [

86].

This study employed a total of (1350) signature photos from the UTSig dataset to train a set that consisted of 50 authentic signatures and six expertly forged signatures. We prefer expert forgeries because they are more difficult to identify than other forgery categories. We evaluated our classification method using 300 signature photos. UTSig is considered an ideal option for studying signature verification in non-Latin scripts as it provides a balanced dataset that contains genuine signatures as well as forged signatures allowing for robust evaluation.

The CEDAR dataset is a foundational dataset in the handwritten signature verification domain. It is considered a benchmark for researchers working on testing algorithms in offline signature verification. CEDAR data compilation comprises the signatures of 55 signers from a variety of professional and cultural contexts. Twenty-four documents were verified by each of these signers at 20-minute intervals. Each forger made an eight-time effort to replicate the signatures of three distinct signers in order to create 24 false signatures for each genuine signer. Consequently, the dataset contains 1,320 legitimate signatures and 1,320 false signatures (55 24) [

87].

A total of 1200 signature photos from the CEDAR dataset were used to train our classification algorithms in this study, and they were subsequently validated on a total of 400 signature images.

Figure 14 illustrates instances of both genuine and fraudulent signatures.

The UTSig database was used to select the original and forged signatures of the first 50 participants in this study. The CEDAR database was used to select the original signatures and 8 fabricated signatures for each participant. The quantity of signature photos extracted from each dataset is illustrated in the subsequent table.

Table 2.

The number of signature images in training set and testing set.

Table 2.

The number of signature images in training set and testing set.

| Sets |

UTSig |

CEDAR |

| Training |

1350 |

1200 |

| Test |

300 |

400 |

| Total |

1650 |

1600 |

3. Results

The efficacy of each algorithm was evaluated by comparing the accuracy achieved after each method was applied to (300) signature images from the UTSig dataset and (400) signature images from the CEDAR dataset. The accuracy achieved after each technique was applied to (300) signature images from the UTSig dataset and (400) signature images from the CEDAR dataset was used to evaluate the effectiveness of each approach. The accuracy and run-time of the categorization algorithms are illustrated in

Table 3.

The run-time and classification accuracy of each classifier, as well as a summary of the experiment’s findings, are presented in

Table 3. Our proposed model demonstrated satisfactory performance on both datasets, with an LSTM accuracy of 92% and a run-time of 1.67 seconds for the USTig dataset and 76% and a run-time of 20.3 seconds for the CEDAR dataset, respectively.

Table 4 compares between our proposed method and a number of methods for offline signature verification, as determined by the accuracy results of each approach.

Furthermore, we evaluate the efficacy of our methodology by employing the following metrics: Equal Error Rate (EER), False Acceptance Rate (FAR), and False Rejection Rate (FRR). The EER is calculated by determining the value at which FAR and FRR are equivalent. The EER is the most widely recognized and effective explanation of a verification algorithm’s error rate. The algorithm makes fewer errors when the EER is lower. The strategy with the lowest expected return on investment (ERR) is considered to be the most precise. Therefore, the results presented in

Table 5 demonstrate that our methodology was the most effective strategy for accurately verifying the signature attributes of offline handwritten signatures.

4. Conclusions

Our paper provided a novel method for features extraction from signature photos. The HOG method was employed to derive features from the main feature points identified using the FAST technique. Subsequently, the derived features were validated using three classifiers: LSTM, SVM, and KNN.

The results of the testing indicated that our proposed model performed satisfactorily in terms of predictive capacity and performance. It achieved an accuracy of (91.6%, 92.4%, and 91.7%) with the UTSig dataset and (92.7%, 92.1%, and 91.7%) with the CEDAR dataset. This is considered a high value, specifically, in the light of the fact that we assessed sophisticated forgeries, which are relatively not easy to detect in comparison with other forms of forgeries, such as basic or opposite-hand ones, due to the fact that expert forgeries are typically very similar to the original signatures. It is anticipated that the feature extraction procedure will be refined to enhance the future prediction capability and signature verification performance. In real-time application, this model is beneficial as quick signature verification is essential. It has the potential to help in introducing reliable identity verification where the model is robust against minor inconsistencies between multiple versions of the same signature. Thus, integrating FAST and HOG for signature verification offers a reliable and effective solution for signature verification.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Fadi Alsuhimat, Khalid Alemerien and Sadeq Alsuhemat; Resources, Enshirah Altarawneh; Validation, Lamis Alqoran; Writing – original draft, Fadi Alsuhimat; Writing – review & editing, Fadi Alsuhimat, Khalid Alemerien, Sadeq Alsuhemat, Lamis Alqoran and Enshirah Altarawneh.

References

- Kao, H & Wen, C. Y. (2020). An Offline Signature Verification and Forgery Detection Method Based on a Single Known Sample and an Explainable Deep Learning Approach. Applied Sciences, 10(11), 16-37. [CrossRef]

- Alsuhimat, F & Mohamad, F. (2021). Convolutional Neural Network for Offline Signature Verification via Multiple Classifiers. Conference: 7th International Conference on Natural Language Computing (NATL 2021). [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, R. K., Shaswat, K., & Kedia, S. (2019). Offline handwritten signature verification using cnn inspired by inception v1 architecture. In 2019 Fifth International Conference on Image Information Processing (ICIIP) IEEE, 263-267. [CrossRef]

- Xamxidin, N., Mahpirat, A., Yao, Z., Aysa, A & Ubul, K. (2022). Multilingual Offline Signature Verification Based on Improved Inverse Discriminator Network. Information, 13(1), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Eltrabelsi, J.; Lawgali, A. (2021). Offline Handwritten Signature Recognition based on Discrete Cosine Transform and Artificial Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Engineering & MIS 2021, Almaty, Kazakhstan, 11–13 October 2021, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, F., Alsuhimat, F., Mohamed, M., Mohamad, M & Jamal, A. (2018). Detection and feature extraction for images signatures. International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 7(3), 44-48. [CrossRef]

- Souza, V.L.F.; Oliveira, A.L.I & Cruz, R.M.O. (2021). An Investigation of Feature Selection and Transfer Learning for Writer-Independent Offline Handwritten Signature Verification. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th IEEE International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Milan, Italy, 10–15 January 2021, 7478–7485. [CrossRef]

- Hafemann, L., Sabourin, R & Oliveira, L. (2017). Learning features for offline handwritten signature verification using deep convolutional neural networks. Pattern Recognition 70 (1), 163–176. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, A., Sawat, D & Hegadi, R. (2020). Verification of genuine and forged offline signatures using Siamese Neural Network (SNN),″ Multimed. Tools Appl, vol. 79, no. 1, pp. 35109–35123, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jindal, U., Dalal, S., Rajesh, G., Sama, N., Jhanjhi, N & Humayun, M. (2022). An integrated approach on verification of signatures using multiple classifiers (SVM and Decision Tree): A multi-classification approach. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences, 9(1), 99-109.

- Rana S., Sharma A., Kumari K. (2020) Performance Analysis of Off-Line Signature Verification. In: Khanna A., Gupta D., Bhattacharyya S., Snasel V., Platos J., Hassanien A. (eds) International Conference on Innovative Computing and Communications. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 1087. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Rana, T., Usman, H & Naseer, S. (2019). Static Handwritten Signature Verification Using Convolution Neural Network. 2019 International Conference on Innovative Computing (ICIC), Lahore, Pakistan, 2019, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A., Karim, M., Kushol, R & Kabir, H. (2018). Performance Comparison of Feature Descriptors inOffline Signature Verification. Journal of Engineering and Technology (JET), 14(1), 1-7.

- Souza, V., Oliveira, A & Sabourin, R. (2018). A writer-independent approach for offline signatureverification using deep convolutional neuralnetworks features. Conference: The 7th Brazilian Conference on Intelligent Systems (BRACIS)At: Sao Paulo, Brazil. [CrossRef]

- Bibi, K., Naz, S & Rehman, A. (2020). Biometric signature authentication using machine learning techniques: Current trends, challenges and opportunities. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 79(1), 289-340. [CrossRef]

- Maergner, P., Pondenkandath, V., Alberti, M., Liwicki, M., Riesen, K., Ingold, R & Fischer, A. (2019). Combining graph edit distance and triplet networks for offline signature verification. Pattern Recognition Letters, 125, 527-533. [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M., Khan, M. A., Faisal, M., Yasmin, M., & Fernandes, S. L. (2020). A framework for offline signature verification system: Best features selection approach. Pattern Recognition Letters, 139(1), 50-59. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, A. B., Hegadi, R. S & Santosh, K. C. (2019). Feature learning for offline handwritten signature verification using convolutional neural network. International Journal of Technology and Human Interaction (IJTHI), 15(4), 54-62. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. (2014). Offline Signature Verification Using Surf Feature Extraction and Neural Networks Approach. International Journal of Computer Science and Information Technologies 5, 3539–3541.

- Kao, H & Wen, C. Y. (2020). An Offline Signature Verification and Forgery Detection Method Based on a Single Known Sample and an Explainable Deep Learning Approach. Applied Sciences, 10(11), 16-37. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M., Alonso, J & Travieso, C. (2005). Offline geometric parameters for automatic signature verification using fixed-point arithmetic. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell, 27(6), 993–997. [CrossRef]

- Kalera, M., Srihari, S & Xu, A. (2004). Offline signature verification and identification using distance statistics. Int J Pattern Recognit Artif Intell, 18(07), 1339–1360. [CrossRef]

- Kovari, B & Charaf, H. (2013). A study on the consistency and significance of local features in off-line signature verification. Pattern Recognit Lett, 34(3), 247–255. [CrossRef]

- Larkins, R & Mayo, M. (2008). Adaptive feature thresholding for offline signature verification. In: International conference on image and vision computing, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T., Le, H & Do, N. (2015). Offline handwritten signature verification using local and global features. Ann Math Artif Intell, 75(1–2), 231–247. [CrossRef]

- Lv, H., Wang, W., Wang, C & & Zhuo, Q. (2005). Off-line chinese signature verification based on support vector machines. Pattern Recognit Lett, 26(15), 2390–2399. [CrossRef]

- Alsuhimat, F & Mohamad, F. (2023).Offline signature verification using long short-term memory and histogram orientation. Bulletin of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, 12(1), 283-292. [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, M., Teja, E & Mathew, A. (2022). Signature Forgery Detection using Machine learning. International Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering Technology and Science, 4(2), 479-483.

- Kumar, M. (2012). Signature Verification Using Neural Network. International Journal on Computer Science and Engineering 4, 1498–1504.

- Ajij, M., Pratihar, S., Nayak, S., Hanne, T & Roy, D. (2021). Off-line signature verification using elementary combinations of directional codes from boundary pixels. Neural Computing and Applications, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- ZulNarnain, Z., Rahim, M., Ismail, N & Arsad, M. (2016). Triangular geometric feature for offline signature verification. World Acad Sci Eng Technol Int J Comput Electr Autom Control Inf Eng, 10(3), 485–488.

- Guerbai, Y., Chibani, Y & Hadjadji, B. (2015). The effective use of the one-class SVM classifier for handwritten signature verification based on writer-independent parameters. Pattern Recognit, vol. 48(1), 103–113. [CrossRef]

- Lv, H., Wang, W., Wang, C & Zhuo, Q. (2005). Off-line chinese signature verification based on support vector machines. Pattern Recognit Lett, 26(15), 2390–2399. [CrossRef]

- Bharathi B & Shekar, B. (2013). Off-line signature verification based on chain code histogram and support vector machine. In: International conference on advances in computing, communications and informatics (ICACCI), pp. 2063–2068. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V., Kawazoe, Y., Wakabayashi, T., Pal, U & Blumenstein, M. (2010). Performance analysis of the gradient feature and the modified direction feature for off-line signature verification. In: International conference on frontiers in handwriting recognition (ICFHR), 303–307. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R., Sharma, J & Chanda, B. (2012).Writer-independent offline signature verification using surroundedness feature. Pattern Recognit Lett, 33(3), 301–308. [CrossRef]

- Hanmandlu, M., Yusof, M & Madasu, V. (2005). Off-line signature verification and forgery detection using fuzzy modeling. Pattern Recognit, 38(3), 341–356. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N., Xu, J., Yu, W & Goto, S. (2013). Gradient local binary patterns for human detection. In: International symposium on circuits and systems, 978–981. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J., Ferrer, M., Travieso, C & Alonso, J. (2008). Off-line signature verification based on high pressure polar distribution. In: International conference on frontiers in handwriting recognition (ICFHR), 373–378.

- Bertolini, D., Oliveira, L., Justino, E & Sabourin, R. (2010). Reducing forgeries in writer-independent off-line signature verification through ensemble of classifiers. Pattern Recognit, 43(1), 387–396. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M & Puhan, N. (2014). Off-line signature verification: upper and lower envelope shape analysis using chord moments. IET Biom, 3(4), 347–354. [CrossRef]

- Serdouk, Y., Nemmour, H & Chibani, Y. (2016). Hybrid Off-Line Handwritten Signature Verification Based on Artificial Immune Systems and Support Vector Machines. In: 9th International Conference on Image Analysis and Recognition (ICIAR), Povoa de Varzim, 13-15 July, pp. 558–565. [CrossRef]

- Zois, E., Alewijnse, L & Economou, G. (2016). Offline signature verification and quality characterization using poset-oriented grid features. Pattern Recognit, 54(1), 162–177. [CrossRef]

- Pal, S., Alaei, A., Pal, U & Blumenstein, M. (2016). Performance of an off-line signature verification method based on texture features on a large indic-script signature dataset. In: Workshop on document analysis systems (DAS), 72–77. [CrossRef]

- Loka, H., Zois, E & Economou, G. (2017). Long range correlation of preceded pixels relations and application to off-line signature verification. IET Biom, 6(2), 70–78. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S., Muhammad, A., Muhammad, Y., Mussarat, F & Steven, L. (2020). A framework for offline signature verification system: best features selection approach. Pattern Recognit Lett, 139, 50–59. [CrossRef]

- Batool, F., Attique, M & Sharif, M. (2020). Offline signature verification system: a novel technique of fusion of GLCM and geometric features using SVM. Multimed Tools Appl. [CrossRef]

- Tahir, N., Ausat, A., Bature, U., Abubakar, K & Gambo, I. (2021). Off-line Handwritten Signature Verification System: Artificial Neural Network Approach. I.J. Intelligent Systems and Applications, 1(1), 45-57. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J., Baptista, B., Lavado, N & Mendes, M. (2022). Offline Handwritten Signature Verification Using Deep Neural Networks. Energies, 15, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Cattin, P. (2012). Image Restoration: Introduction to Signal and Image Processing. MIAC, University of Basel.

- Jahan, T., Anwar, S & Al-Mamun, S. (2015). A Study on Preprocessing and Feature Extraction in offline Handwritten Signatures. Global Journal of Computer Science and Technology: F Graphics & Vision, 15(2), 20-25.

- Madasu, V & Lovell, B. (2008). An Automatic Offline Signature Verification and Forgery Detection System (chapter 4). In Brijesh Verma and Michael Blumenstein (Ed.), Pattern recognition technologies and applications: Recent advances (pp. 63-89) Hersey, PA: Information Science Reference. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahadeen, B., AlTarawneh, M & AlTarawneh, I. (2010). Signature Region of Interest using Auto cropping. IJCSI International Journal of Computer Science Issues, 7 (4), 12-19. [CrossRef]

- Alsuhimat, F., Mohamad, F & Iqtait, M. (2019). Detection and extraction features for signatures images via different techniques. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1179(1), 12-18. [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, V & Karwankar, A. (2013). Automatic static signature verification systems: A review. International Journal of Computational Engineering Research, 3(2), 8-12.

- Bonilla, J., Ballester, M., Gonzalez, C & Hernandez, J. (2009). Offline signature verification based on pseudo-cepstral coefficients. In Proceedings of the 2009 10th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, ser. ICDAR ’09. Washington, DC, USA: IEEE Computer Society. [CrossRef]

- Parodi, M., Gomezand, J & Belaid, A. (2011). A circular grid-based rotation invariant feature extraction approach for off-line signature verification. In Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR), International Conference on. IEEE, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Narayana, M., Annapurna, L & Mounika, K. (2017). Offline signature verification. International Journal of Electronics and Communication Engineering and Technology (IJECET), 8(2).

- Rosten, E & Drummond, T. (2006). Machine learning for high speed corner detection. in 9th Euproean Conference on Computer Vision, 1(2), 430–443. [CrossRef]

- Trajkovic, M & Hedley, M. (1998). FAST corner detector. Image and Vision Computing, 16(2), 75-87. [CrossRef]

- Corvee, E. (2010). Body Parts Detection for People Tracking Using Trees of Histogram of Oriented Gradient Descriptors. In: IEEE, 469 –475. [CrossRef]

- Suard, F., Rakotomamonjy, A., Bensrhair, A & Broggi, A. (2006). Pedestrian Detection using Infrared images and Histograms of Oriented Gradients. In: IEEE, 206– 212. [CrossRef]

- Déniz, O., Bueno, G., Salido, J & Dela Torre, F. (2011). Face recognition using Histograms of Oriented Gradients. In: Pattern Recognition Letters, 32(12), 1598–1603. [CrossRef]

- Huber, D., Morris, D.D & Hoffman, R. (2010). Visual classification of coarse vehicle orientation using Histogram of Oriented Gradients features. In: IEEE, 921 – 928. [CrossRef]

- Dalal, N & Triggs, B. (2005). Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. International Conference on Computer Vision & Pattern Recognition (CVPR ’05), San Diego, United States, 886-893. [CrossRef]

- Alsuhimat, F & Mohamad, F. (2021). Histogram Orientation Gradient for Offline Signature Verification via Multiple Classifiers. Nveo-Natural Volatiles & Essential OILS Journal| NVEO, 8(6), 3895-3903.

- Abbas, N., Yasen, K., Faraj, K., Abdulrazak, L & Malallah, F. (2018). Offline handwritten signature recognition using histogram orientation gradient and support vector machine. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology 96(8), 2075-2084.

- Le, X., Ho, H., Lee, G & Jung, S. (2019). Application of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Neural Network for Flood Forecasting. MDBI, water, 11, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Greff, K., Srivastava, R., Koutnik, J., Steunebrink, B & Schmidhuber, J. (2017). LSTM: A Search Space Odyssey. IEEE, Transaction on Neural Network and Learning Systems, 28(10), 2222 – 2232. [CrossRef]

- Graves, A., Liwicki, M., Fernandez, S., Bertolami, R., Bunke, H & Schmidhuber, J. (2009). A Novel Connectionist System for Improved Unconstrained Handwriting Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 31, 855-868. [CrossRef]

- Gers, F & Schmidhuber, J. (2001). LSTM recurrent networks learn simple context free and context sensitive languages. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 12(6), 1333–1340. [CrossRef]

- Graves, A & Schmidhuber, J. (2005). Framewise phoneme classification with bidirectional LSTM and other neural network architectures. Neural Networks, 12(1), 5–6. [CrossRef]

- Sak, H., Senior, A & Beaufays, F. (2014). Long Short-Term Memory Based Recurrent Neural Network Architectures for Large Vocabulary Speech Recognition. ArXiv e-prints. [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S & Schmidhuber, J. (1997). Long short-term memory. Neural computation, 9(8), 1735–1780. [CrossRef]

- Olmos, R., Tabik, S & Herrera, F. (2018). Automatic handgun detection alarm in videos using deep learning,” Neurocomputing, 275, 66-72. [CrossRef]

- Fix, E & Hodges, J.L. (1951). Discriminatory Analysis, Nonparametric Discrimination: Consistency Properties. Tech. rep., USAF School of Aviation Medicine, Texas, pp. 1-21.

- Azmi, A.N., Nasien, D & Omar, F.S. (2016). Biometric signature verification system based on freeman chain code and k-nearest neighbor. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahaman, A & Abdallah, M. (2013). K-Nearest Neighbor Classifier for Signature Verification System. In: International Conference on Computing, Electrical and Electronics Engineering (ICCEEE), Khartoum, 26-28 August, 58–62. [CrossRef]

- Kalera, M., Srihari, S & Xu, A. (2004). Offline signature verification and identification using distance statistics. International Journal of Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence 18 (7), 1339–1360. [CrossRef]

- Sigari, M.H., Pourshahabi, M.R & Pourreza, H.R. (2011). Offline Handwritten Signature Identification and Verification Using Multi-Resolution Gabor Wavelet. International Journal of Biometrics and Bioinformatics 5, 234–248.

- Nguyen, V., Nguyen, H., Tran, D., Lee, S & & Jeon, J. (2017). Learning Framework for Robust Obstacle Detection, Recognition, and Tracking. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst, 18(6), 1633-1646. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.A., Vargas, J.F., Morales, A & Ordonez, A. (2012). Robustness of offline signature verification based on grey level features. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 7, 966–977. [CrossRef]

- Frias-Martinez, E., Sanchez, A & Velez, J. (2006). Support vector machines versus multi-layer perceptrons for efficient off-line signature recognition. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 19 (6), 693–704. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.A., Goswami, M.M & Adesara, H.H. (2015). Offline Handwritten Signature Verification using Low Level Stroke Features. In: International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), Kochi, 10-13 August, 1214–1218. [CrossRef]

- Pal, S., Pal, U & Blumenstein, M. (2012). Off-line English and Chinese signature identification using foreground and background features. In Int. Joint Conf. on Neural Networks (IJCNN’12). 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, K. Fouladi, K & Araabi, B. (2016). UTSig: A Persian offline signature dataset. IET Biometrics, 6(1), 1.8. [CrossRef]

- Deya, S., Dutta, A., Toledoa, I., Ghosha, S., Liados, J. (2017). SigNet: Convolutional Siamese Network for Writer Independent Offline Signature Verification. Pattern Recognition Letters, Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Poddara, J., Parikha, V & Bharti, S. (2020). Offline Signature Recognition and Forgery Detection using Deep Learning. The 3rd International Conference on Emerging Data and Industry 4.0 (EDI40), Warsaw, Poland, 6 - 9. [CrossRef]

- Kisku, D., Gupta, P & Sing, J. (2009). Fusion Of Multiple Matchers Using Svm For Offline Signature Identification. In International Conference on Security Technology, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 201-208. [CrossRef]

- Daqrouq, K., Sweidan, H., Balamesh, A & Ajour, M. (2017). Off-Line Handwritten Signature Recognition by Wavelet Entropy And Neural Network. Entropy, 19, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, A., Araabi, B & Fouladi, K. (2016). Deep multitask metric learning for offline signature verification. Pattern Recognition Letters, 80(1), 84-90. [CrossRef]

- Sulong, G., Ebrahim, A & Jehanzeb, M. (2014). Offline handwritten signature identification using adaptive window positioning techniques. Signal & Image Processing An International Journal, 5(3), 1-14. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).