1. Introduction

The tourism industry’s move to digital is rapidly affecting the way people decide on their trips, thanks to Artificial Intelligence (AI). Today, AI helps with everything from booking a flight to arranging an itinerary, so it has become a must-have for travelers (Kelleher, 2023). More and more, AI is used because people need personalized, instant and reliable information to help with decisions when things are uncertain. ChatGPT, an advanced language-based system by OpenAI, is considered one of the biggest advantages to the tourism industry. Statista (2023) reported that in 2023, 70% of the travelers around the world used AI-powered platforms for planning a trip during the recommendation phase. Also, ChatGPT currently attracts more than 1.8 billion visits each month and is used by more than 180 million people worldwide (Similarweb, 2023).

A higher number of travelers using AI for booking reveals people now value communicating with conversational AI more than using regular search engines or sites (Mostafa & Kasamani, 2022; Dwivedi et al., 2023). Because ChatGPT can conduct human-like conversations and deliver appropriate responses quickly, it differs from conventional information systems (Whitmore, 2023; Ku, 2023). On the other hand, relying on technology this much can lead to major problems. Many people have trouble trusting AI recommendations, mainly in situations where some people do not have enough information and cognitive biases exist (Kim et al., 2023; Ye et al., 2023).

Trust in AI within the travel industry has been investigated by looking at online travel agencies, reviews online and chatbots (Tussyadiah et al., 2020; Ali et al., 2023). There is still much to learn about how trust evolves with systems like ChatGPT which rely on advanced natural language tools to recommend things. There is a common expectation in literature that having accurate data is essential for earning trust (DeLone & McLean, 2003; Shi et al., 2021). In addition, it does not develop in the same way for everyone. Users’ background beliefs, digital knowledge, and the way a place is presented all help determine the way information is seen as true (Afshardoost & Eshaghi, 2020; Tosyali et al., 2025).

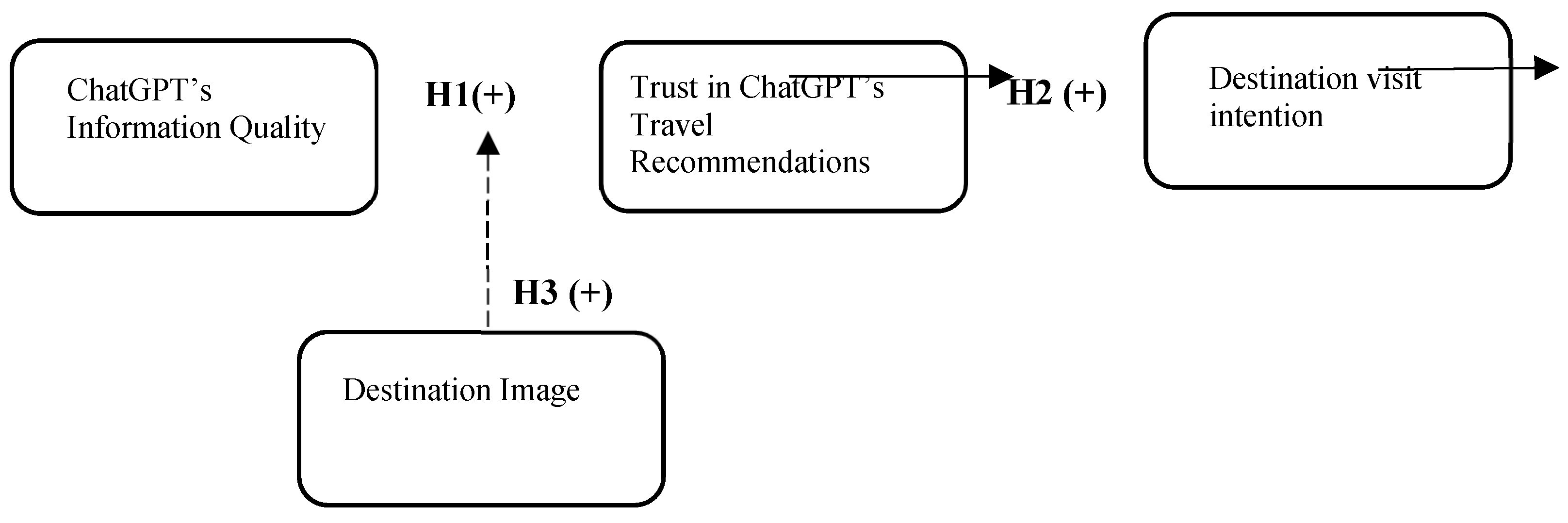

Prior studies have primarily evaluated static constructs of trust, neglecting how it evolves through user interaction and contextual influences such as perceived destination image. This image acts as a way that affects users’ perceptions of how credible AI is (Pham & Khanh, 2021; Gorji et al., 2023). Previous researchers have linked destination image and travel intention, but very few have looked at it as something that helps explain the relationship between information quality and trust in AI (Ali et al., 2023; Orden-Mejía et al., 2025). As a result of these gaps, the present study brings forward and tests a framework that focuses on three main constructs: (1) information quality affects trust in ChatGPT’s recommendations, (2) trust in ChatGPT leads to an intention to visit certain destinations, and (3) the moderating role of destination image on the relationship between information quality and trust. This research contributes to the literature on AI adoption in tourism as well as to the psychological mechanisms of digital trust and as such provides actionable insights for marketers of tourist destinations.

Based on the framework presented, this study addresses the following research questions:

To what extent does ChatGPT’s information quality influence users’ trust in its travel recommendations?

How does trust in ChatGPT’s travel recommendations affect users’ destination visit intentions?

Does destination image moderate the relationship between information quality and trust in ChatGPT’s travel recommendations? on references.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Previous Studies and Gaps Identification

Table 1 presents an overview of prior studies examining the role of ChatGPT and in tourism, with a particular focus on trust mechanisms, destination image, and travel decision-making processes.

Ali et al. (2023) showed in their study that the level of trust users have in ChatGPT’s travel recommendations increases when the recommendations are relevant, credible, useful and intelligent. Yet, the study did not discuss destination image or how it can affect the desire to visit a place, and it also did not investigate factors that could affect or modify these results. According to Solomovich and Abraham (2024), personality traits like openness, neuroticism and extraversion can impact people’s level of trust in and ease of use with ChatGPT for travel planning. Mediation was found, but the study did not further explore destination image or its connection to travel intentions. Kim et al. (2024) found out that the way information is structured on AI ChatGPT’s page can lead people to intend to visit the destination. Even so, it overlooked how quality of information and trust in its recommendations influenced the decision to visit a place.

In their study, Orden-Mejía et al. (2025) considered chatbots and pointed out that people’s satisfaction and intention to use them again depend on how useful the information is. Nevertheless, it did not study how ChatGPT affects the image of different tourist destinations, trust in those areas or why people wish to visit them. In their study, Li and Lee (2025) considered how accuracy, timelines and adding a human touch help increase trust and loyalty with specific AI assistants. The study pointed out personalization, but didn’t consider how use of ChatGPT changes our views of a destination or leads to a trip. Yang et al. (2024) examined e-tourism platforms, focusing on how personal understanding, the reliability of information and customers’ trust in technology could impact visitors. Nonetheless, the research failed to explore how ChatGPT can affect how people view a place or intend to travel there which is necessary for travel planning using AI. This study addresses gaps examining ChatGPT’s information, its importance for reliable travel advice, how it affects a destination’s image, and the consequences on intending to visit such places.

2.2. The Information Systems Success Model

The ISS Model provides a solid basis for studying how information quality supports user trust and the decisions people make regarding technology (DeLone & McLean, 2003). Initially, the model was designed to gauge the effectiveness of information systems and proved that Information Quality affects both user satisfaction, trust and how people behave (Petter, et al., 2008; Çelik & Ayaz, 2022). Tourism services powered by AI like ChatGPT make information quality more important, as risks from travel decisions are much higher. Information quality, marked by its accuracy, timeliness, relevance and completeness (DeLone & McLean, 2003), helps users think the system is credible, important for trust formation (Kim et al., 2023; Wang & Yan, 2022). Confidence in the system improves when users believe what they receive from ChatGPT is helpful and accurate (Shi et al., 2021).

There is significant evidence from tourism research showing that trust matters greatly in reaching and influencing user behavior (Seçilmiş et al., 2022; Filieri et al., 2015). Yet, the development of trust is not the same for everyone; how strong the destination’s image is often helps determine how well certain information functions. People who already like a location tend to trust advice linked to it more (Tosyali et al., 2025; Afshardoost & Eshaghi, 2020). In contrast, having a poor view of a destination might still block trust, so it’s clear that we need to explore how both the information and the person receiving it come together in the overall perception.

2.3. Information Quality

Information quality refers to the accuracy, format, completeness, and currency of information produced by digital technologies (Lin et al., 2023). It plays a pivotal role in shaping users’ trust in online platforms and decision-making systems. According to the updated ISS model, information quality significantly influences users’ intentions and system use through its perceived accuracy, relevance, completeness, and timeliness (DeLone & McLean, 2003). In the context of AI-driven applications, high-quality information delivery is paramount in generating trust, especially when users depend on these systems for personal or consequential decisions, such as travel planning (Wang & Yan, 2022).

ChatGPT provides users with personalized travel recommendations by synthesizing data and offering contextualized insights. The perceived quality of these recommendations can strongly impact users’ trust. Shi et al. (2021) highlight that AI systems that deliver accurate, up-to-date, and relevant travel information enhance users’ trust and engagement. Similarly, Casaló et al. (2020) find that perceived informativeness and reliability of AI outputs are key antecedents of trust in AI-based travel services. Furthermore, information that is consistent and easy to understand improves user confidence and reduces uncertainty in travel decision-making (Yang et l., 2024).

Therefore, the hypothesis is proposed:

H1: ChatGPT’s information quality positively affects trust in ChatGPT’s travel recommendations.

2.4. Trust in ChatGPT Travel Recommendations

According to Rotter (1967), trust refers to the belief that a party’s word or promise is reliable and that the party will fulfil their obligations in an exchange relationship. In this study, trust in ChatGPT recommendations refers to the extent to which a user feels assured and prepared to act upon the recommendation given by ChatGPT (González-Rodríguez et al., 2022). Trust is a fundamental mechanism that reduces perceived risk and enables users to adopt technology-based systems in uncertain contexts, such as tourism planning (Ye et al., 2023; Muliadi et al., 2024). Trust in AI systems specifically refers to the user’s willingness to rely on the system despite the inherent uncertainties or lack of full understanding of how the technology operates (Choung et al., 2023).

In the tourism context, trust in AI-generated recommendations enables users to make confident travel decisions, including choosing destinations they may have not previously considered (Tussyadiah et al., 2020). Trust bridges the gap between the technical functionality of AI systems and users’ behavioral intentions (Ku, 2023). ChatGPT’s ability to respond conversationally and provide tailored advice mimics human-like interaction, which further enhances interpersonal trust dynamics (Marinchak et al., 2018). This study therefore argues that trust in ChatGPT is a critical predictor of a user’s intention to visit the recommended destination, as trust mitigates uncertainty and increases confidence in the decision-making process.

Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2:

Trust in ChatGPT’s travel recommendation positively affects destination visit intention.

2.5. Destination Image

Destination image is defined as a subjective interpretation of a place held in a tourist’s mind, which affects the tourist’s behaviour (Gorji et al., 2023; Tedjakusuma et al., 2023). While the quality of information serves as a critical foundation for building trust, its impact is not isolated from contextual factors. Specifically, consumers’ pre-existing perceptions—shaped by the destination image—substantially influence how they interpret and assess AI-generated information, such as that provided by ChatGPT (Tosyali et al., 2025). Destination image serves as a cognitive-affective filter that colors the interpretation of external stimuli—including travel recommendations from AI agents (Afshardoost & Eshaghi, 2020). If the image of a destination is positive, users may be more inclined to perceive ChatGPT’s information about that destination as credible and consistent with their own views, thus reinforcing trust (González-Rodríguez et al., 2022). Conversely, if the destination image is weak or negative, even high-quality information may not be sufficient to establish trust.

This dynamic suggests that destination image moderates the relationship between ChatGPT’s information quality and trust—either strengthening or weakening the trust-building effect of information quality. Prior studies conducted by Pham and Khanh (2021) and Rotter (1967) show that people have greater trust in information that fits their preconceived attitudes and beliefs. The recommendation receives heightened trustworthiness from users when ChatGPT delivers information that matches positively with their destination image.

Thus, the study proposes:

H3: Destination image moderates the relationship between ChatGPT’s information quality and trust in ChatGPT’s travel recommendation.

Figure 1 exhibits all the developed hypotheses above.

3. Methods

3.1. Operationalization and Measurement Items

The present work defines and measures key constructs to ensure internal consistency and validity. The main constructs observed include Information quality, trust, destination image, and destination visit intention. These constructs are assessed using a 7-point Likert scale, with responses of 1 is "strongly disagree" to 7 "strongly agree." All measurement items are shown in

Table 2.

3.2. Sampling Technique and Data Collection

This study utilizes a purposive sampling within the framework of a non-probability technique, in order to select individuals who met the criteria for the study. Criteria that must be met by the respondents are: (1) be a male or a female, (2) be at least 18 years of age, (3) have completed high school or an equivalent level of education, and (4) possessed prior experience in using ChatGPT. The study wanted to ensure the inclusion of individuals who would be the most relevant in the context of the study. An online questionnaire made in Google Forms was used for data collection and it was distributed on social medias of Line, Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram. The survey had three parts: one to see if a person met the requirements, another for general demographic data, and the third for checking how customers were engaging with behavior intention. Data was collected using a 7-point Likert scale to see what the participants think and feel more clearly. Over a 3-month period (January to March 2025), the survey gathered 528 valid responses. Because the dataset is robust, it allows us to study what influences destiation visit intention and the role of trust.

3.3. Analysis Technique

The present work’s analysis was based on Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) using SmartPLS 4.0. SEM was chosen since it is effective in exploring new areas, mainly when analyzing how different variables are linked together (Hair et al., 2017). By using this approach, researchers learn how hidden constructs like behavior intention and their relationships with observations interact. As latent constructs cannot be directly observed, they were measured by observing the socio aspects, the technical aspects of live streaming, and the trust transfer system (Falk & Miller, 1992). Common Method Variance (CMV) was dealt with first to confirm that the research constructs were reliable and relevant. Validity was confirmed by examining that the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values were ≥0.5 and the factor loadings were also > 0.7 (Baumgartner & Weijters, 2021). Both Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) and Composite Reliability (CR) were checked and they must be ≥0.7 to be said reliable (Hair et al., 2017). The Fornell-Larcker criterion was used to confirm that the square root of each AVE must be larger than its correlation with every other construct. Moreover, the cross-loading matrix showed that the factor loadings for each construct were greater than their correlations with other constructs (Henseler et al., 2015). As the last step, hypothesis testing was done using indicators of Goodness of Fit (GoF) and R-squared values. By doing the analysis step by step, the study becomes more reliable and robust.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Demographics

The present work analyzed 528 respondents who had tried ChatGPT, 56.82% of whom were men, proving that both men and women make use of these chatbot technologies. The survey found that most respondents are millennials or young professionals (51.89%) and those in their twenties (27.84%), revealing that people in the digital sector are using ChatGPT mainly for practical reasons such as organizing travel plans. Most users had completed a bachelor’s degree (61.93%) and a smaller number had completed a master’s program (11.74%). Most respondents had jobs as either private employees (25%) or civil servants (22.54%). A further 17.05% said they were entrepreneurs, showing how varied ChatGPT’s appeal can be for workers. Importantly, a majority of the participants (31.82%) were employed in information technology, as expected given how involved technology companies are in using AI. Of all users, 31.06% had used ChatGPT for less than a year and the main reason for using it was for academic purposes (28.41%); searches for support in professional and traveling activities came second (18.56%). These demographic trends affirm the study's focus on information quality, trust, and destination image, as the majority of respondents are experienced, educated, and motivated users of AI in practical decision-making contexts. All Sample Demographic can be seen in

Table 3.

4.2. Common Method Variance (CMV)

This present work starts by assessing Common Method Variance (CMV) through Harman’s single-factor test, aiming to determine whether a substantial portion of the variance in responses can be attributed to a single factor, following the guidelines proposed by Baumgartner & Weijters (2021). The analysis revealed a CMV value of 33.7%, which is well below the commonly accepted threshold of 50%, indicating that common method bias is unlikely to pose a significant issue in this research.

4.3. Validity and Reliability Assement

The SmartPLS 4.0 software was used for the Structrual Equation Model (SEM) to check the validity and reliability of the data accurately. A systematic analysis was completed to ensure that the measurement model is of high quality. First, the factor loadings were checked, revealing that they were all above 0.7, indicating reliable use of the items in calculating the scores (Hair et al., 2017).

Table 4 shows that the findings prove that each of these constructs represents its respective dimension well.

Afterward, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values were reviewed to confirm that the items are convergent. All constructs achieved AVE values above the threshold of 0.5 (Hair et al., 2017), signifying that the latent constructs effectively capture the variance in their observed indicators, as illustrated in

Table 4. Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) and Composite Reliability (CR) were applied to determine that all the constructs in the questionnaire demonstrated acceptable internal consistency by exceeding 0.7 (Hair et al., 2017). The findings prove that the constructs are dependable and effective in discovering behavior intention in the research structure. The results in

Table 4 demonstrates that the model is strong and reliable, making it suitable for the next stages of research.

With validity and reliability confirmed, discriminant validity was checked using three different techniques. Firstly, Fornell and Larcker suggest that for every construct, the AVE should be higher than the correlation with all the other variables. From

Table 5, we can see that every square root AVE was greater than the equivalent inter-construct correlation, confirming discriminant validity. Secondly, the cross-loading matrix, which investigates the factor loading of an item on its designated construct is higher than its correlation with other constructs. From

Table 7, it appears that the factor loadings of all the factors exceed their correlations with other factors, proving strong discriminant validity. Finally, to check the discriminant validity, the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) was applied, with a limit of 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015). As seen in

Table 6, all of the HTMTs were less than 0.85, demonstrating that the constructs are well differentiated from one another.

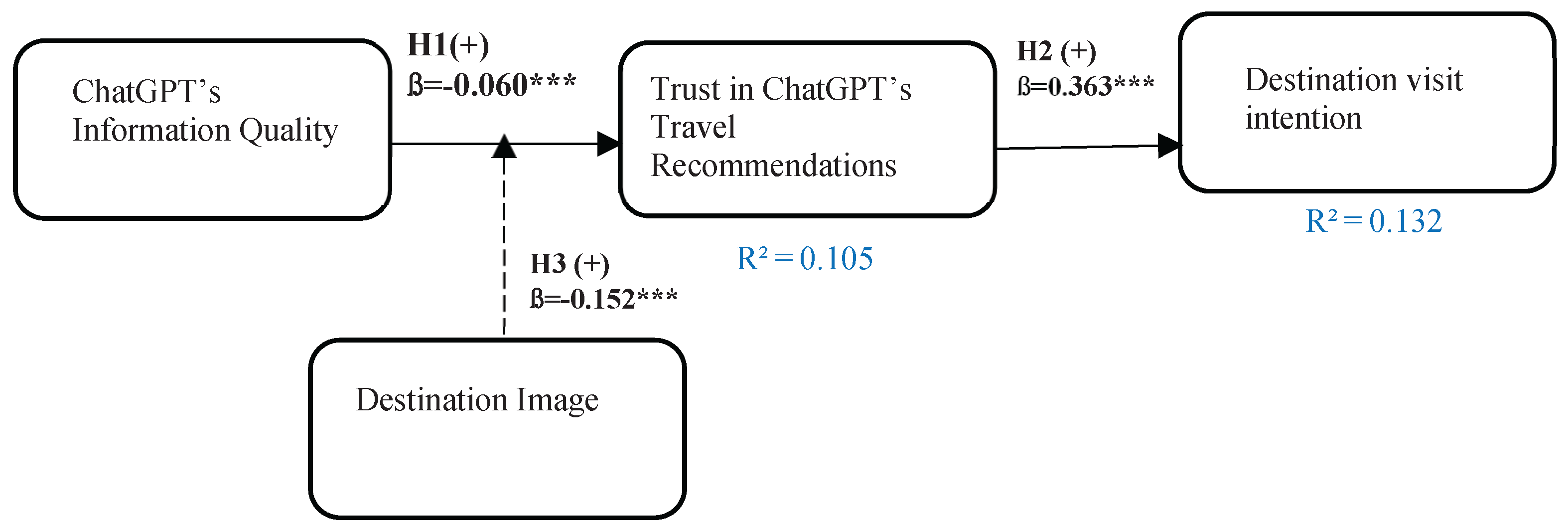

4.4. Model Robustness Testing

The process began by analyzing the R² of every endogenous construct to find out how much variation in the outcome variables was caused by the predictors. Falk and Miller (1992) note that a model is viable when the R² value is above 0.1. Based on the findings, both Destination visit intenton (R² = 0.132) and Trust in ChatGPT travel recommendation (R² = 0.105) can be greatly explained by information quality and destination image. These results confirms that the model can illustrate the relationships between variables and is effective in explaining what leads to destination visit intention in tourism industry. In the second step, tests were done to ensure the model accurately fits the data. Hu and Bentler (1999) suggest that a model is well-fitted when the SRMR is lower than 0.05 or 0.08. Furthermore, the Normed-Fit Index (NFI) is taken into account as acceptable when it gets very close to 0.95. By using bootstrap results for the fit indices, the authors accurately interpret the values for d_ULS and d_G. The value found for SRMR was 0.107 which falls over the suggested threshold of 0.05 or 0.08, so the SRMR could not be accepted. Nevertheless, the NFI value of 0.736 is quite similar to 0.95, so it remains within a suitable range.

To measure how reliable and effective the study’s research model was, the Goodness of Fit (GoF) was used. GoF merges the model’s R² and AVE into a single total. It is calculated by multiplying the average R² and the average AVE together and then taking the square root. By using this approach, one can confidently judge if the model is reliable and fits the relationships among the constructs. The formula used for GoF is as follows:

To evaluate the Goodness of Fit (GoF), specific cut-off values are used: thresholds under 0.10 mean no fit, between 0.10 and 0.25 indicate a small fit, from 0.25 to 0.36 show a moderate fit, and those surpassing 0.36 mean a high fit (Tenenhaus et al., 2005; Wetzels et al., 2009). GoF value computed in this study is 0.426, so it is regarded as a high fit. Here, the results underline that the research model performs very well and accurately represents the relationships among all the constructs.

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

Table 8 exhibits the results of hypothesis testing of this study. For hypothesis H1 of ChatGPT information quality significantly affects trust in ChatGPT travel recommendation is unsupported as it did not meet the statistical criteria for support with path coefficient of -0.060 and T-value of 1.073. Meanwhile, Hypothesis H2 of trust in ChatGPT travel recommendation significantly affects destination visit intention is supported with path coefficient of 0.363 and T-value of 6.554. Hypothesis 3 of destination image moderates the relationship between ChatGPT information quality and trust in ChatGPT travel recommendation is unsupported with path coefficient of -.152 and T-value of 2.573. Hypothesis Summary can be seen in

Figure 2.

5. Discussion

The present study examines the effect of ChatGPT’s information quality on destination visit intention, with destination image serving as a moderating variable. The hypothesis testing reveals several key findings. First, information quality does not significantly affect users' trust in ChatGPT’s travel recommendations (H1). This suggests that users may continue to rely on ChatGPT regardless of how relevant, valid, accurate, or comprehensive the information is. Prior research indicates that factors such as personalization and anthropomorphism play a more influential role in building trust. For example, Shin et al. (2025) show that how users trust ChatGPT’s travel suggestions relies more on its narrowing options and suggesting personalized plans than on the quality of the data itself. Similarly, Kim et al. (2023) mention that if users are still given incorrect information, they might trust the service as long as the app is enjoyable and flexible. These insights suggest that tourism marketers should produce marketing content and messages that are customized, important to consumers and encourage interaction by paying attention to popular travel topics like eco-tourism, cultural heritage and different types of food experiences frequently highlighted by ChatGPT.

In contrast, trust in ChatGPT travel recommendation positively influences destination visit intention (H2). This signifies that when users trust ChatGPT travel recommendation, they are more likely to accept the recommendations, and form intentions to visit the suggested destinations. These finding is in line with Qu et al. 2011, which posits that user trust in ChatGPT can increase their willingness to act on travel advice provided by ChatGPT as long as such advice is perceived as credible and personalized. Shin et al. (2025) propose a similar point that when ChatGPT can narrow down travel options, users can not only reduce decision fatigue but also strengthen the user's intent to travel. These insights suggest that the more users believe in the credibility and personalization of ChatGPT’s suggestions, the more likely they are to move from consideration to commitment in their travel decisions. Meanwhile, H3 findings show that destination image does not moderate the relationship between ChatGPT’s information quality and trust in its travel recommendations. This suggests that even when users hold a favorable image of a destination, such affective perceptions do not enhance the impact of ChatGPT’s information quality on trust formation. This aligns with previous studies which propose that moderating variables like destination image tend to have a more substantial impact on final behavioral intentions than on intermediary cognitive constructs such as trust (Qu et al., 2011; Artigas et al., 2015).

In addressing the research questions, the study finds that trust in ChatGPT’s travel recommendations significantly drives users’ intentions to visit suggested destinations. However, information quality alone does not significantly impact trust, suggesting that users value personalized and engaging interactions over purely informational content. Additionally, the destination image does not enhance or weaken the relationship between information quality and trust, indicating its limited moderating role. These insights provide practical recommendations for developers and marketers, highlighting the importance of focusing on personalization and interactive features in AI travel recommendation systems to effectively foster user trust and boost travel intentions.

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study challenges traditional assumptions within ISS model, which typically assert that high information quality leads directly to increased user trust in technology-based recommendations. Contrary to these assumptions, this study’s findings reveal that information quality alone does not significantly influence trust in AI-mediated travel recommendations provided by ChatGPT. This suggests that tourists may evaluate ChatGPT travel advice based on factors beyond only quality indicators, such as relevance, accuracy, and completeness. This aligns with recent expansions of technology acceptance models—specifically in Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) and AI-driven technologies—which propose that anthropomorphic characteristics, personalization, and conversational experience enhance social presence and user engagement, thereby influencing trust in interactive AI systems.

In addition, the present study repositions the role of destination image in the trust-building process. The findings of this study demonstrate that destination image does not moderate the effect of information quality on trust, contradicting established beliefs that positive mental representations of a destination can enhance trust in AI-provided information. This indicates that even when tourists hold favorable views of a destination, it does not necessarily improve their trust in ChatGPT's travel suggestions if the perceived information quality does not meet their expectations. This suggests that trust formation in AI contexts may be more dependent on the interactive and experiential quality of AI communication rather than the traditional cognitive evaluations of content quality and destination familiarity.

Meanwhile, trust in ChatGPT's travel recommendations significantly affects destination visit intention, affirming the theoretical argument that trust remains a critical predictor of behavioral intentions in digital tourism contexts. This is in line with Trust Theory, which postulates that in situations where there is some degree of uncertainty, such as travel planning, the willingness to act based on the information provided by ChatGPT is greatly encouraged by trust in the platform. Since ChatGPT has multiple functions that simulate natural human-like conversation, the perceived risk is likely to decrease, thereby influencing users' willingness to visit the recommended destinations.

6.2. Practical Implications

The present work provides practical insights for key stakeholders in the tourism industry, including Destination Management Organizations (DMOs), travel agencies, and policymakers on how to utilize ChatGPT to increase destination visit intentions. The findings of this work assert that trust in ChatGPT travel recommendations as a primary driver of tourists' willingness to visit suggested destinations. In contrast to the conventional tourism marketing channels, ChatGPT’s conversational and interactive design of delivery provides a unique channel to deliver personalized travel recommendations in real time, thereby increasing tourists’ engagement and its trust in travel decision.

For DMOs, they can create storytelling and attractively experiential value in the digital context. Having a dialogue-based response, the DMOs should focus on the narrative-based content - plunging descriptions of local experiences, unheard cultural bits, and detailed descriptions of landmarks that can be accessed through various online resources. For example, they may generate fascinating narratives around local festivals, unknown spots and genuine local experience that are appealing to travelers’ imagination and pull towards travel intention. This style of narrative is more likely to be recorded and imitated by ChatGPT in its interactions with users because rich depth and experiential depth are key to engaging users.

For travel agencies, they can focus on personalized travel engagement. Since the effectiveness of ChatGPT’s efficiency is associated with its conversational and interactive tendencies, travel agencies can develop interactive chatbot solutions on the websites that have the conversational style of ChatGPT. These chatbots may give more immediate itinerary suggestions, travel tips, and local information through an interactive and dynamic approach. Besides, they can generate live chat support where the travelers can ask particular questions and get immediate personalized responses, which resemble the conversational trust-forming experienced with ChatGPT. This transformation from static information to real-time live conversation could increase user confidence and stimulate destination visit intentions.

For policymakers, they can support the creation of official tourism storytelling platforms that provide immersive, interactive content about local destinations, which could be referenced by ChatGPT. Moreover, policymakers could incentivize the production of virtual experiences and interactive cultural showcases that are digitally accessible, enhancing tourists' engagement and travel intentions through enriched, experiential information. This approach would align with how tourists interact with ChatGPT—favoring narrative depth and authenticity over purely factual descriptions.

7. Conclusions

The present work examines the effect of ChatGPT’s travel recommendations on destination visit intention through the lens of the Information Systems Success (ISS) Model. The work’s findings show that ChaGPT’s information quality does not significantly affect trust in ChatGPT’s travel recommendations, trust in ChatGPT’s travel recommendations significantly affect destination visit intention, and destination image does not moderate the relationship between information quality and trust in ChatGPT’s travel recommendations. This study has two primary limitations. First, it is geographically limited to Indonesia, potentially restricting the generalizability of the findings to other cultural contexts where digital trust mechanisms may differ. Future research should expand its geographic scope to validate these findings across diverse tourism markets. Second, the study focuses exclusively on trust and visit intention, leaving the role of user satisfaction and loyalty underexplored. Future studies could investigate how continuous interactions with ChatGPT not only affect initial trust and travel intention but also influence long-term user loyalty and repeated usage in travel planning. Understanding these longitudinal impacts would provide richer insights into ChatGPT's role as a sustainable digital travel companion.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.P.T., L.W.L., I.J.E., and A.D.K.S.; methodology, A.P.T. and L.W.L.; software, A.P.T., L.W.L.; validation, A.P.T., L.W.L., I.J.E., and A.D.K.S; formal analysis, A.P.T. and A.D.K.S.; investigation, I.J.E., and A.D.K.S.; resources, A.P.T.; data curation, I.J.E., and A.D.K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.T. and L.W.L.; writing—review and editing, I.J.E., and A.D.K.S; visualization, I.J.E.; supervision, L.W.L and A.D.K.S.; project administration, A.P.T.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

The data analyzed during the present work are not publicly available due to respect to respondent’s privacy

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Afshardoost, M. , & Eshaghi, M. S. Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analysis. Tourism Mana ment 2020, 81, 104154. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F. , Yasar, B., Ali, L., & Dogan, S. Antecedents and consequences of travelers' trust towards personalized travel recommendations offered by ChatGPT. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2023, 114, 103588. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, H. , & Weijters, B. (2021). Structural equation modeling. In Handbook of market research (pp. 549–586). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Casaló, L. V. , Flavián, C., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. Journal of Business Research 2020, 117, 510–519. [Google Scholar]

- Çelik, K. , & Ayaz, A. Validation of the Delone and McLean information systems success model: A study on student information system. Education and Information Technologies 2022, 27, 4709–4727. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, N. T. K. , & Pham, H. The moderating role of eco-destination image in the travel motivations and ecotourism intention nexus. Journal of Tourism Futures 2024, 10, 317–333. [Google Scholar]

- Choung, H. , David, P., & Ross, A. Trust in AI and its role in the acceptance of AI technologies. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2023, 39, 1727–1739. [Google Scholar]

- DeLone, W. H. , & McLean, E. R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. Journal of Management Information Systems 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, Y. K. , Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A. K.,... & Wright, R. Opinion paper: “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management 2023, 71, 102642. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R. F. , & Miller, N. B. (.

- Filieri, R. , Alguezaui, S., & McLeay, F. Why do travelers trust TripAdvisor? Antecedents of trust toward consumer-generated media and its influence on recommendation adoption and word of mouth. Tourism Management 2015, 51, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M. R. , Díaz-Fernández, M. C., Bilgihan, A., Okumus, F., & Shi, F. The impact of eWOM source credibility on destination visit intention and online involvement: A case of Chinese tourists. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology 2022, 13, 855–874. [Google Scholar]

- Gorji, A. S. , Garcia, F. A., & Mercadé-Melé, P. Tourists' perceived destination image and behavioral intentions towards a sanctioned destination: Comparing visitors and non-visitors. Tourism Management Perspectives 2023, 45, 101062. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. , Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J. , Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T. , & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan, M. , Malik, M. S., & Zubair, S. K. Impact of vlog marketing on consumer travel intent and consumer purchase intent with the moderating role of destination image and ease of travel. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221099522. [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher, S. R. R. (2023, May 10). A third of travelers are likely to use ChatGPT to plan a trip, 10 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. H. , Kim, J., Kim, C., & Kim, S. Do you trust ChatGPTs? Effects of the ethical and quality issues of generative AI on travel decisions. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2023, 40, 779–801. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, E. C. S. Anthropomorphic chatbots as a catalyst for marketing brand experience: Evidence from online travel agencies. Current Issues in Tourism 2023, 27, 4165–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X. , Mamun, A. A., Yang, Q., & Masukujjaman, M. Examining the effect of logistics service quality on customer satisfaction and re-use intention. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0286382. [Google Scholar]

- Marinchak, C. , Forrest, E., & Hoanca, B. The impact of artificial intelligence and virtual personal assistants on marketing. Journal of Marketing Development and Competitiveness 2018, 12, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company. (2023). The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier. https://www.mckin sey.

- Mostafa, R. B. , & Kasamani, T. Antecedents and consequences of chatbot initial trust. European Journal of Marketing 2022, 56, 1748–1771. [Google Scholar]

- Muliadi, M. , Muhammadiah, M. U., Amin, K. F., Kaharuddin, K., Junaidi, J., Pratiwi, B. I., & Fitriani, F. The information sharing among students on social media: The role of social capital and trust. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems 2024, 54, 823–840. [Google Scholar]

- Orden-Mejía, M. , Carvache-Franco, M., Huertas, A., Carvache-Franco, O., & Carvache-Franco, W. Analysing how AI-powered chatbots influence destination decisions. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0319463. [Google Scholar]

- Petter, S. , DeLone, W., & McLean, E. R. Measuring information systems success: Models, dimensions, measures, and interre lationships. European Journal of Information Systems 2008, 17, 236–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H. S. T. , & Khanh, C. N. T. Ecotourism intention: The roles of environmental concern, time perspective and destination image. Tourism Review 2021, 76, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps, A. Holiday destination image—the problem of assessment: An example developed in Menorca. Tourism Management 1986, 7, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J. B. (1967). A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. Journal of Personality.

- Seçilmiş, C. , Özdemir, C., & Kılıç, İ. How travel influencers affect visit intention? The roles of cognitive response, trust, COVID-19 fear and confidence in vaccine. Current Issues in Tourism 2022, 25, 2789–2804. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S. , Gong, Y., & Gursoy, D. Antecedents of trust and adoption intention toward artificially intelligent recommendation systems in travel planning: A heuristic–systematic model. Journal of Travel Research 2021, 60, 1714–1734. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S. , Kim, J., Lee, E., Yhee, Y., & Koo, C. ChatGPT for trip planning: The effect of narrowing down options. Journal of Travel Research 2025, 64, 247–266. [Google Scholar]

- Similarweb. (2023, ). ChatGPT topped 3 billion visits in September. https://www.similarweb. 3 October.

- Statista. (2023). Share of travelers who used a mobile device to plan or research travel with an AI chatbot worldwide as of 23, by country. https://www.statista. 20 October 1421.

- Tedjakusuma, A. P. , Retha, N. K. M. D., & Andajani, E. The effect of destination image and perceived value on tourist satis faction and tourist loyalty of Bedugul Botanical Garden, Bali. Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship 2023, 6, 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M. , Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y. M., & Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Computational statistics & data analysis 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar]

- Tosyali, H. , Tosyali, F., & Coban-Tosyali, E. Role of tourist-chatbot interaction on visit intention in tourism: The mediating role of destination image. Current Issues in Tourism 2025, 28, 511–526. [Google Scholar]

- Tussyadiah, I. P. , Wang, D., Jung, T. H., & tom Dieck, M. C. Virtual reality, presence, and attitude change: Empirical evidence from tourism. Tourism Management 2020, 66, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , & Yan, J. Effects of social media tourism information quality on destination travel intention: Mediation effect of self-congruity and trust. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 1049149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, L. , Wong, P. P. W., & Zhang, Q. Travellers’ destination choice among university students in China amid COVID-19: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. Tourism Review 2021, 76, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M. , Odekerken-Schröder, G., & Van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS quarterly.

- Whitmore, G. (2023, ). Will ChatGPT replace travel agents? Forbes. https://www.forbes. 7 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. , Zhang, L., & Feng, Z. Personalized tourism recommendations and the e-tourism user experience. Journal of Travel Research 2024, 63, 1183–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y. , You, H., & Du, J. Improved trust in human-robot collaboration with ChatGPT. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 55748–55754. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).