1. Introduction

Understanding cognitive differences between neurodivergent and neurotypical individuals is critical for advancing interdisciplinary research and applications in neuroscience, psychology, and computational modeling. Neurodivergent individuals, characterized by distinct patterns of thought and perception, often face challenges when interfacing with systems designed for neurotypical cognition. Bridging these cognitive differences requires innovative approaches, which not only enhance mutual understanding and collaboration but also foster social inclusivity and therapeutic interventions. By tailoring environments and interactions to accommodate diverse cognitive profiles, we can reduce stigma [

1], empower neurodivergent individuals in social settings [

2], and develop personalized therapeutic strategies that improve mental health outcomes and quality of life [

3].

This paper introduces quantum-like computational models as a novel framework to harmonize cognitive processes between neurodivergent and neurotypical individuals. Recent advancements in these models demonstrate their potential to revolutionize our understanding of brain activity by leveraging principles derived from quantum mechanics. For instance, Khrennikov [

4] proposed a model that utilizes quantum-like interference patterns to illustrate information processing in neural networks. These innovative approaches have been further extended to address complex biological phenomena, such as information processes in biosystems [

5], probabilities derived from complex amplitudes [

6], and measurements performed on cognitive systems [

7].

By situating these models within the broader context of cognitive neuroscience, this work underscores their transformative potential. Not only do they address longstanding methodological gaps, but they also pave the way for practical applications, including adaptive human-computer interfaces and educational tools tailored to cognitive diversity. These advancements highlight the relevance and utility of quantum-like models in bridging cognitive differences and advancing interdisciplinary research at the intersection of biology, physics, and neuroscience.

In this paper, we employ a quantum-like model to describe brain activity, with a specific focus on the process of interpretation. We utilize tools from measurement theory, focusing on the phenomenon of collapse [

8], which reduces entropy within the system while increasing entropy in the surroundings. In our quantum-like model, this collapse corresponds to the brain’s activity in interpreting concepts, while the associated increase in environmental entropy reflects the potential emission of heat. Our model, which predicts the emission of heat into the environment, is in line with current measurements with infrared cameras [

9,

10,

11] indicating that complex cognitive activity is reflected by an increase in the heat released to the surroundings. For example, Pereira et al. [

12] reported that the autonomic nervous system is activated with the increasing complexity of cognitive activity. This results in an elevation in the facial temperature, particularly around the nose, cheeks, and lips, as measured using infrared thermography. The increased heat emission is linked to muscle contraction and heightened metabolic activity, which occurs as the brain works hard to manage complex cognitive tasks, reflecting the body’s response to the increased mental effort. Krisztina et al. [

13] explained the relation between the complexity of a cognitive task and an increased emission of heat by revealing how mental effort directly increases brain metabolism. As cognitive activity becomes more complex, the brain’s demand for energy increases, leading to increased consumption of glucose and use of oxygen. This heightened metabolic activity generates more heat as a by-product, which needs to be dissipated by the brain to maintain its optimal functioning. In our model, the possibility of heat emission results directly from the second law of thermodynamics, which is fundamental. Thus, the mechanism or detection of heat emission can vary in different systems without violating this law. For example, a heightened metabolic activity generates more heat as a by-product in the neurological system or an increase in temperature in computer activity.

This paper focuses on two observers: a neurotypical observer with a standard cognitive perception [

14] and a neurodivergent observer [

15,

16,

17,

18] with an unconventional perception. In our approach, each observer’s brain acts like a quantum measuring device that performs an interpretation aligned with their personality structure during the process of collapse [

19,

20,

21]. According to our quantum-like model, while the neurotypical observer’s basis of states defines conventional interpretations, the neurodivergent observer leverages superpositions to generate interpretations that deviate from normative cognitive frameworks. These superposed concepts, however, are often misinterpreted or even dismissed by the neurotypical observer, as they fall outside the bounds of conventional understanding. This dynamic is illustrated through ambiguous images in

Section 3, highlighting the cognitive disconnect between the two perspectives.

2. Quantum States as Concept Generation

Scientific theories, particularly quantum theory, employ mathematical constructs such as superposition, space, and spanning sets. However, when describing human observers, such as neurotypical and neurodivergent individuals, it becomes necessary to use logical statements and concepts that may not align with conventional mathematical language. The purpose of the following sections is to illustrate how these mathematical tools can be interpreted and related to the perspectives of these observers.

2.1. Logical Meaning of Superposition

In this paper, the discussion begins by elucidating selected features of quantum theory in simplified terms, focusing on the representation of concepts, the significance of measurement, and the logical constructs that describe both measurement and superposition.

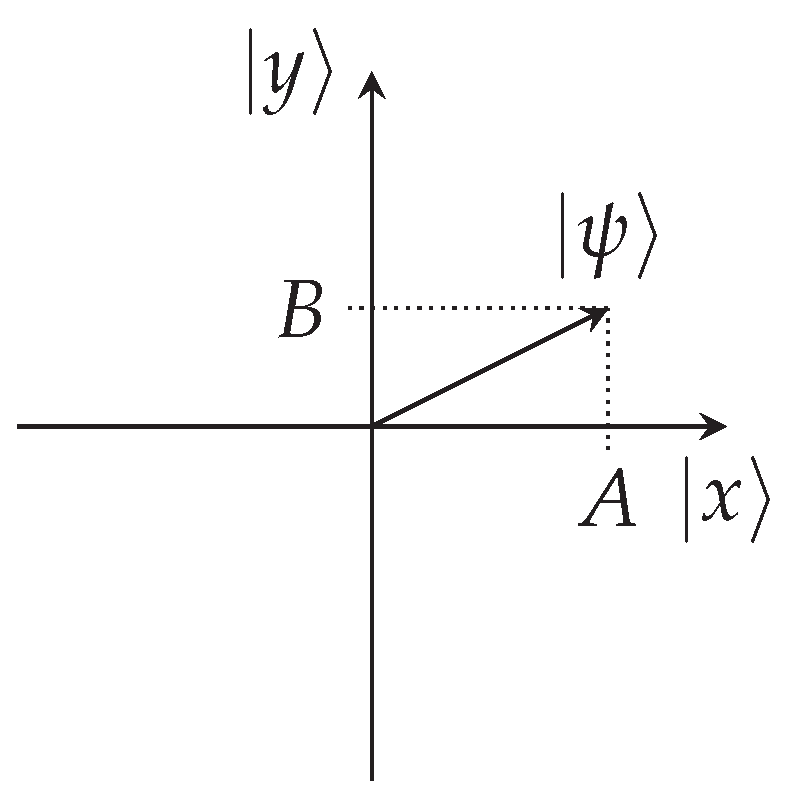

Figure 1 illustrates directions in a two-dimensional (2D) space. The states

and

represent the horizontal and vertical axes, respectively, spanning all directions within the 2D plane. By forming a superposition, the state

, expressed as

encompasses

both the horizontal and vertical directions to define a new direction.

- (1)

Superposition represents the logical conjunction “and.” In the illustration, corresponds to the states and .

- (2)

If and represent a concept (not necessarily directions), then represents a combined concept derived from the individual ones.

2.2. Logical Meaning of Measurement

Consider a -observer equipped with a measuring device designed to detect the states or . Since the output of any measuring device cannot simultaneously correspond to both states (as established in the previous subsection discussing the meaning of superposition), when exposed to the new spanning set and , the output cannot simultaneously be and . Thus, from the perspective of the -observer, the measurement process involving or results in a collapse into either or , with probabilities and , respectively, relative to the -states.

Although real coefficients are used in this illustration, as shown in the following subsection, the conventional definition for complex coefficients, based on the Born interpretation, is preserved. Consequently, the measurement process embodies the logical ‘or’ statement.

The conclusion drawn is that quantum measurement exemplifies the logical ‘or.’ Moreover, we infer that observers capable of measuring or , as opposed to those limited to and , exhibit distinct cognitive programming.

3. Illustrative Example—Mature and Young Ladies

This section demonstrates the principles of measurement using ambiguous images. We examine the interpretations of these images by two observers:

Typical, representing a neurotypical individual who applies a conventional interpretation [

14], and

Divergent, an observer whose interpretation deviates from the norm [

22].

3.1. Context and Motivation

This paper presents a quantum-like model emphasising the quantum-like collapse phenomenon. An ambiguous image, shown in Figure 2, which may profoundly impact the reader’s internalisation of the collapse concept, also demonstrates a collapsing phenomenon in brain activity. Then, we introduce two observers analysing the figure: Typical and Divergent. Despite extensively trying to find examples demonstrating the Divergent way of thinking, we failed, as we belong to the Typical population. Using ambiguous figures, we demonstrate how a neurotypical person who cannot find the precise meaning of a concept can still express an ambiguous concept, possibly understood by a Divergent, in the technical way of superposition.

3.2. The Image to Interpret

Figure 2 is subject to interpretation by both observers [

22].

3.3. Typical Interpretation

Typical (like most of the population) recognises the image as composed of both mature and young ladies. This fits the ‘and’ nature of superposition as presented in

Section 2. Moreover,

Typical cannot recognize both women simultaneously. Thus, considering a complete interpretation with only one result,

Typical collapses (in his mind) Figure 2 into either a mature lady or a young woman. This leads us to derive a quantum-like approach to describe a recognition scenario.

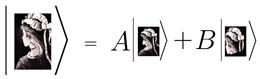

3.4. Quantum-Like Model

Consider the image

interpreted as a mature lady and the image

interpreted as a young lady. These are associated with the states

and

. In our perception, which we associate with the typical observer, if the mature lady is observed, it is determined that it is not a young woman, and vice-versa. This distinction between the images is expressed in the orthogonality relation

= 0. Associating Figure 2 with both mature and young ladies, we define the ambiguous state as

wherein according to the Born interpretation, the coefficients

A and

B determine the probabilities

and

for detecting (recognising)

or

.

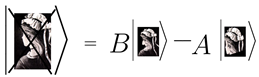

3.5. Divergent Interpretation

Imagine

Divergent, for whom the image of Figure 2 makes sense. Now, by assuming real coefficients, in addition to Equation (2), we have the orthogonal state,

whereas for

Typical, neither

nor

makes sense. Nevertheless, the logical possibility that mathematics presents, in which it is possible to generate a complete set of states, as in Equations (2) and (3) to describe other scenarios even if they lack clarity for us, who are typical, allows us to present the divergent observer.

3.6. Measurement Output Interpreted from Both Perspectives

Suppose

Typical performs a quantum-like measurement causing

to collapse into

. That is, he identifies the ambiguous image with the young lady. From the Typical perspective, the uncertainty vanishes. Representing

in the terminology of

Divergent, we have

We realise that the measurement outcome, which made Typical’s interpretation entirely certain, generated uncertainty in Divergent’s interpretations. In the following sections, we analyse systems of this type from a thermodynamic perspective. We begin by reviewing some fundamental definitions.

4. Useful Terminologies in Thermodynamics

In thermodynamics, the following terminologies are used:

System: A specific part (generally small) of the universe under consideration.

Surroundings (or Environment): All external elements that can interact with the system.

Universe: The total combination of the system and its surroundings.

Observing the evolution of the system, we find two categories [

23,

24,

25,

26]:

Spontaneous evolution: To put it simply, a spontaneous process occurs naturally, without needing the input of energy from the outside.

Non-spontaneous process: Such a process does not occur freely and requires the input of external energy to proceed.

There are several rules defining spontaneous evolution, from among which we focus on the criterion of increasing entropy. According to the second law of thermodynamics, the total entropy of a system and its surroundings (universe) always increases. This allows the definition of life processes as

decreasing entropy. Although the entropy of the system decreases, the increase in the entropy of the environment compensates for any reduction in the system’s disorder [

23,

24,

25,

26]. In the most likely scenario, an exothermic, spontaneous process, the reduction of the entropy of the system is accompanied by the release of heat to the environment [

26]. Reversible processes conserve entropy [

27].

5. Thermodynamics in a Quantum-Like Model

Consider the normalised states

where

and

characterise

Typical and

Divergent, respectively.

5.1. Entropy

We implement the definition of the entropy for the two observers:

where

and

are the probabilities of finding the system in the states

or

, respectively. In the quantum-like model and according to the Born interpretation [

28], we associate the coefficients’ squares

and

with

and

respectively. In the density states terminology, Equation (

6) can be written as [

29]

where

and

are the density matrices of, respectively,

Typical and

Divergent. Note that we omitted the Boltzmann constant that appeared in a previous study by Bracken [

29].

5.2. Two-State System

For simplicity, we discuss a two-state system. Consider the observers describing reality with the sets of two orthogonal states

where in the transition between Equations (

8) to (

9) we assumed real coefficients.

5.2.1. Thermodynamics of Quantum-Like Collapse

In this section, the process of collapse is described from the two points of view, those of

Typical and

Divergent. The clauses describing the different perspectives are visually described using the illustrations from

Section 3.

-

Evolution of entropy from the perspective of Typical:

Assume that

Typical measures the

Divergent state

as expressed in Equation (

9).

Before the collapse, the initial entropy is

where the superscript stand for

Typical. After the collapse, where the system is fixed in one of

’s states, we obtain the final entropy:

. Thus, we obtain

meaning that from

Typical’s perspective, entropy is reduced. If we consider this process as spontaneous, this must be associated with the emission of heat to the environment.

-

Evolution of entropy from the perspective of Divergent:

Before Typical performs his measurement, the entropy of Divergent, who recognises perfectly

the state , is zero. Regardless of the measurement output from Typical’s measurement, the

final entropy measured by

Divergent becomes (see Equation (

8))

where the superscript

D stand for Divergent. Thus, we obtain that

If the collapse processes of both observers affect each other, the decrease in entropy in Typical’s observation will be equal to the increase in entropy in Divergent’s observation. In thermodynamics, this implies that this collapse process is reversible. In the informational sense, it can be deduced that at the beginning of the process, Divergent fully recognised the state, whereas uncertainty was present in Typical’s observations; however, after the measurement, the situation was reversed: Typical fully recognised the state, while Divergent was left with uncertainty.

5.3. Measurement of Heat Emission

Thermal cameras have recently been used to measure temperature changes in the foreheads and noses of patients during cognitive activities such as thinking [

9,

10,

11]. This observed increase in temperature aligns with the predictions of the quantum-like model presented in this paper and directly relates to our earlier discussion of thermodynamics. Specifically, the increase in temperature corresponds to the release of heat, consistent with the second law of thermodynamics, as cognitive activity induces heightened metabolic processes. This connection offers a promising avenue for further exploration and experimental validation.

6. Summary

In this paper , we introduced a quantum-like approach describing brain activities which focused on two observers: Typical, the conventional observer, and Divergent, an unorthodox observer. Our model predicted heat emission associated with quantum-like collapse that describes cognitive activity.

This research is theoretical and assumes that brain activity can be described by quantum-like processes, particularly a collapse that releases heat. Some evidence aligns with this theory. First, the theory of Ghirardi, Rimini, and Weber (GRW) explains the phenomenon of quantum collapse through a model of spontaneous state collapse. While the GRW model does not directly address biological systems, it proposes that random spontaneous collapses inherently obey the second law of thermodynamics, resulting in an increase in the entropy of the surroundings [

30]. This increase in entropy can conceptually be related to the emission of heat to the environment. Assuming that collapse processes are accompanied by heat emission and considering that cognitive activity increases body temperature, this theoretical framework provides a basis for supporting our model. Beyond this physical reasoning supporting our quantum-like collapse theory, we illustrated the collapse processes using an ambiguous image of a young or mature woman (see Figure 2). We are convinced that interpreting the image as either a mature or young woman demonstrates a collapse-like process in the brain.

As mentioned, the involvement of heat emission in cognitive activity is a well-established fact [

9,

10,

11] Thus, the advantage of a quantum-like model lies in its ability to create novel states through a technical mathematical operation, superposition. In example of the young and mature women presented in

Section 3, we introduced the women’s concepts using quantum-like states. We ‘typical’ readers faced difficulties interpreting the superposition of the states as shown in Equations (2) and (3); however, we were able to define different states because of the technical mathematical capacities of superposition. Assume the following scenario: a group of ‘typical’ concepts (such as an old woman and a young woman) are represented using spatially-extended states. Through relations of superposition, it is possible to define new states that are unfamiliar to the ‘typical’ group but have the potential to be familiar to non-‘typical’ populations. A suitable thermal profile may allow us to identify a subject’s degree of familiarity with the new concepts. A concept that is incomprehensible to us, the ‘typical’, can be very logical for non-typical populations. This will allow us to build a new system of concepts that will aid in understanding populations that are ‘programmed differently’ from us, the ‘typical’.

Method

The present study is theoretical. To conduct the research, we used a quantum-like model that describes cognitive activity, particularly the phenomenon of quantum collapse. In the first sections, we linked quantum tools to logical sentences and showed how concepts are constructed through the superposition of states. We explained that a space-spanning basis of states describes a set of concepts the observer uses. The collapse phenomenon was understood as an observer’s interpretation of states he cannot measure. The possibility that observers possess a diverse set of concepts compared to the norm was raised, and whether and how it is possible to find the appropriate spanning sets that characterize these observers was asked. We explained that a collapse involves releasing heat into the environment and suggested using a thermal camera to check the temperature changes of observers exposed to several situations. An unorthodox method we implemented was to use an ambiguous illustration to illustrate the phenomenon of collapse in a non-quantum system as shoen in Figure 2.

Results

This section presents the findings derived from the quantum-like mathematical modeling of concept generation, emphasizing differences between neurodivergent and neurotypical cognitive processes. Key results include:

1. The mathematical derivation demonstrates that neurodivergent individuals can process orthogonal cognitive states, providing unique interpretations of ambiguous images such as the old-young ladies example.

2. The quantum-like collapse processes reveal thermodynamic properties linked to measurable heat emission during cognitive activities.

3. Simulations and models suggest that computational frameworks can effectively capture these processes, enabling algorithms to bridge cognitive differences.

Discussion

The findings underscore the potential of quantum-like models in providing a unified framework for understanding cognitive diversity. The thermodynamic link to heat emission suggests measurable physiological markers for concept generation, opening avenues for experimental validation.

Neurodivergent individuals’ ability to interpret orthogonal cognitive states highlights their unique cognitive potential, challenging traditional paradigms of concept recognition. These results have implications for adaptive educational tools, human-computer interaction, and collaborative systems.

However, limitations exist. The model’s reliance on theoretical constructs necessitates experimental data for validation. Future work should focus on real-world applications and further refinement of algorithms to enhance accessibility for neurodivergent populations.

Author Contributions

The author is solely responsible for all aspects of this work, including conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, visualization, and manuscript preparation.

Funding

This work received no specific funding.

Acknowledgments

This study is dedicated to the memory of my son, Lior Roth (1987–2022). Lior was an individual with special needs, whose unique interpretations of reality significantly shaped the perspectives shared in this work. Often described as being ‘programmed differently’, Lior’s distinctive worldview and experiences were a profound inspiration for this research.

The authors acknowledge the use of Open AI’s ChatGPT for assistance in improving the clarity, organization, and formatting of the manuscript. All intellectual content, research ideas, and conclusions are the sole responsibility of the authors

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

References

- Baron-Cohen, S. Autism: Deficits in mindreading or cognitive style? Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2000, 4, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaidis, C. What can physicians learn from the neurodiversity movement? AMA Journal of Ethics 2012, 14, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicano, E.; Stears, M. Bridging autism, science, and society: Moving toward an ethically informed approach to autism research. Autism Research 2011, 4, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Author, P. Placeholder Title. Placeholder Journal 2024, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basieva, I.; Khrennikov, A.; Ozawa, M. Quantum-like modeling in biology with open quantum systems and instruments. Biosystems 2021, 201, 104328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khrennikov, A. Quantum-like modeling of cognition. Frontiers in Physics 2015, 3, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khrennikov, A. Quantum-like formalism for cognitive measurements. Biosystems 2003, 70, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghirardi, G.; Bassi, A. Collapse Theories. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2020. Summer 2020 Edition.

- Tsuzuki, D.; Shibasaki, H.; Yamanaka, T.; Kohno, S. Thermal infrared imaging of brain activity during cognitive tasks. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine 2007, 26, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelrahman, Y.; Velloso, E.; Dingler, T.; Schmidt, A.; Vetere, F. Cognitive heat: Exploring the usage of thermal imaging to unobtrusively estimate cognitive load. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies 2017, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, R.F.; Pérez, I.; Ramos, F.J.; Cano, M.; Hernandez, A.; Ega?a, M. Thermal infrared imaging as a biomarker of emotional responses. Plos One 2016, 11, e0165542. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M.I.; Lee, J.M.; Gordon, B. Infrared thermography reveals facial temperature changes during cognitive workload. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 2011, 23, 2683–2694. [Google Scholar]

- Krisztina, T.; Illes, F.; Kovacs, M. Brain heat dissipation during sustained mental effort: Evidence from infrared thermography. Neuroscience Letters 2017, 647, 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen, S. Autism: Deficits in mindreading or cognitive style? Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2000, 4, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaidis, C. What can physicians learn from the neurodiversity movement? AMA Journal of Ethics 2012, 14, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicano, E.; Stears, M. Bridging autism, science, and society: Moving toward an ethically informed approach to autism research. Autism Research 2011, 4, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaidis, C. What can physicians learn from the neurodiversity movement? AMA Journal of Ethics 2012, 14, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicano, E.; Stears, M. Bridging autism, science, and society: Moving toward an ethically informed approach to autism research. Autism Research 2011, 4, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, Y. Interpreting machine for ambiguous figures. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, Y. Quantum-Like Approach for Deriving a Theory Describing the Concept of Interpretation. International Journal of Physical and Mathematical Sciences 2023, 17, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Y. Spaces of Interpretations: Personal, Audience and Memory Spaces. In Proceedings of the Science and Information Conference. Springer; 2023; pp. 577–585. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, J. Perception of an ambiguous figure is affected by own-age social biases; Nature Publishing Group UK London, 2018; Vol. 8, p. 12661.

- Kostić, M.M. Entropy and the Second Law of Thermodynamics: From the Microscale to the Macroscale (Explaining the Inefficiency of Energy Conversion) and the Controversial, Crucial Concept of the Arrow of Time. Entropy 2020, 22, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, M.M. Entropy and the Second Law of Thermodynamics: From the microscale to the macroscale (explaining the inefficiency of energy conversion) and the controversial, crucial concept of the arrow of time. Entropy 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Longdom. Life: A Complex Spontaneous Process Takes Place Against the Background of Nonspontaneous Processes Initiated by the Environment. Journal of Clinical Trials & Research, 2020.

- Kostić, M.M. Entropy and the Second Law of Thermodynamics: From the Microscale to the Macroscale (Explaining the Inefficiency of Energy Conversion) and the Controversial, Crucial Concept of the Arrow of Time. Entropy 2020, 22, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reif, F. Fundamentals of Statistical and Thermal Physics; Waveland Press: Long Grove, 2009; chapter 4, pp. 116–146.

- Born, M. The interpretation of quantum mechanics. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 1953, 4, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, P. Entropy in Quantum Mechanics and Applications to Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics. In Quantum Mechanics; Bracken, P., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghirardi, G.C.; Rimini, A.; Weber, T. Unified dynamics for microscopic and macroscopic systems. Physical review D 1986, 34, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

interpreted as a mature lady and the image

interpreted as a mature lady and the image  interpreted as a young lady. These are associated with the states

interpreted as a young lady. These are associated with the states  and

and  . In our perception, which we associate with the typical observer, if the mature lady is observed, it is determined that it is not a young woman, and vice-versa. This distinction between the images is expressed in the orthogonality relation

. In our perception, which we associate with the typical observer, if the mature lady is observed, it is determined that it is not a young woman, and vice-versa. This distinction between the images is expressed in the orthogonality relation  = 0. Associating Figure 2 with both mature and young ladies, we define the ambiguous state as

= 0. Associating Figure 2 with both mature and young ladies, we define the ambiguous state as

or

or  .

.

nor

nor  makes sense. Nevertheless, the logical possibility that mathematics presents, in which it is possible to generate a complete set of states, as in Equations (2) and (3) to describe other scenarios even if they lack clarity for us, who are typical, allows us to present the divergent observer.

makes sense. Nevertheless, the logical possibility that mathematics presents, in which it is possible to generate a complete set of states, as in Equations (2) and (3) to describe other scenarios even if they lack clarity for us, who are typical, allows us to present the divergent observer. to collapse into

to collapse into  . That is, he identifies the ambiguous image with the young lady. From the Typical perspective, the uncertainty vanishes. Representing

. That is, he identifies the ambiguous image with the young lady. From the Typical perspective, the uncertainty vanishes. Representing  in the terminology of Divergent, we have

in the terminology of Divergent, we have

This study is dedicated to the memory of my son, Lior Roth (1987–2022). Lior was an individual with special needs, whose unique interpretations of reality significantly shaped the perspectives shared in this work. Often described as being ‘programmed differently’, Lior’s distinctive worldview and experiences were a profound inspiration for this research.

This study is dedicated to the memory of my son, Lior Roth (1987–2022). Lior was an individual with special needs, whose unique interpretations of reality significantly shaped the perspectives shared in this work. Often described as being ‘programmed differently’, Lior’s distinctive worldview and experiences were a profound inspiration for this research.