1. Introduction

Cryptococcal meningitis (CM) is the most common cause of fatal central nervous system (CNS) infections in individuals with HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa, contributing significantly to AIDS-related mortality [

1]. Annually, an estimated 112,000 cryptococcal-related deaths occur globally, with the highest burden in regions with limited access to comprehensive healthcare [

2]. Despite the rollout of antiretroviral therapy (ART), CM-associated mortality remains high due to complications such as immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) [

3].

A major challenge in CM management is the variability in disease presentation and outcomes. Recent studies suggest that this variability is influenced not only by host immune factors but also by genetic differences in Cryptococcus strains [

4]. Patients have better clinical outcomes with a pro-inflammatory Type-1 immune response, and have increased rates of fungal clearance and improved patient survival [

5]. Conversely, a Type-2 immune response correlates with poor patient outcomes [

1] ]. The mechanism behind shifts between Type-1 or Type-2 immune responses remains largely unknown, but recent evidence shows that some virulence factors in

Cryptococcus. neoformans promote deleterious Type-2 responses [

6].

Previous studies identified structural variations (SV) in the genome of

C. neoformans that are associated with changes in virulence during human infection, including aberrant chromosome numbers in clinical isolates [

7,

8,

9]. Known

Cryptococcus virulence factors were identified based on in vitro genetic screens or lack of strain growth in animal models [

10,

11,

12]. These studies have begun to link the production of known virulence factors to patient outcome, yet only examined production of a few known factors and did not explore underlying molecular differences between strains. Most importantly, the studies recently showed that the mouse inhalation model recapitulates differences in clinical isolate virulence in humans, again highlighting the importance of inherent genetic differences between isolates. Surprisingly, changes in known virulence factors were unable to account for these virulence differences, suggesting that virulence factors impacting in vivo virulence are yet to be determined. Thus, there is a critical need to use an unbiased approach to discover

Cryptococcus virulence factors that impact in vivo virulence and patient mortality in CM infection.

Gerstein et al., explored in a previous study and identified

Cryptococcus DNA polymorphisms associated with alterations in cytokine levels during CM diagnosis [

13]. The study identified four previously uncharacterized genes CNAG_04922; CNAG_07837, CNAG_00363 and CNAG_06422 with effects on IL-2 levels at the time of CM diagnosis. This study focused on one of these genes, CNAG_04922, which had alternate alleles associated with decreased IL-2 levels compared to the reference allele. IL-2 plays a crucial role as a key cytokine in promoting a protective Th1 immune response, which is essential for effectively fighting the fungal pathogen by stimulating the activation and proliferation of cytotoxic T cells and macrophages that can eliminate Cryptococcus cells [

14]. Survival was higher in subjects infected with isolates containing the CNAG_04922 alternate alleles compared to those infected with the isolates carrying the H99 reference allele [

15]. The current study, compared the immune response to

C. neoformans H99 [

16] that has the reference allele and UgCl377 that has an alternate allele. Specifically UgCl377 has two mutations in the CNAG_04922 gene link to decrease IL-2 Levels, located at positions 18933 (C → A) and 18941 (C →T) on chromosome 10 [

13]. Using an ex-vivo cytokine release assay, we tested the hypothesis that the genetic variations between these two isolates alters the immune response

2. Materials and Methods

Study design: This was a cross-sectional study carried out among HIV+ and HIV- adult participants with no CCM (Volunteers). For the HIV+ participants, only, those with CD4+ <=200 cells/mm3 (homogeneous population and with risk of CCM) fitted the study criteria; HIV–ve volunteers were included as control (limited risk of CCM infection). Participants: Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from each participant, 18 years and older (≥ 18 years of age).

Sample collection from participants: Approximately, 5-10mls of whole blood was collected in lithium heparin tubes from each of the 15 HIV+ve and 15 HIV-ve study participants after an informed consent process to participate in the study. The samples were immediately assayed after collection

Antigen preparation: H99 and UgCl377 whole-cell antigens were prepared by sub culturing each isolate on YPD agar plates and incubating for 48 hours at 370C. The resulting colonies were suspended in sterile PBS (pH 7.4) to McFarland 3.0 (approx. 9.0x10^8 CFU/mL). The suspension was heated at 650C for 1 hour to inactivate the cells. Effective heat-killing was confirmed through lack of growth upon plating a portion of the suspension on YPD agar plates and incubating for 48 hours at 370C. H99 and UgCl377 whole cell antigen were added in the ratio of 1:1 to the peripheral blood samples from each participant in the 24-well sterile cell culture plates. The culture plates were rotated gently until mixed and then incubated at 37oC in a 5% CO2 incubator overnight.

After the overnight incubation, the plate contents were transferred aseptically using a sterile 1mL micropipette tip to a sterile 15ml Falcon tube and centrifuged at 3000g for 3 minutes to separate the plasma and the cells. The plasma was transferred into 2mL cryovials and stored at -200C until analysis.

Ex-vivo Cytokine Stimulation: The ex-vivo cytokine stimulation assay was performed as previously [

17] at Mbarara University of Science and Technology –Genomics and Translational Laboratory (MUST –GTL). Briefly, antigen preparations from

C. neoformans strains (H99 reference strain [

16] and CNAG_04922 alternate allele-carrying strain) were added to peripheral blood samples from each study participant, divided into three portions as follows:

H99 strain treated portion, CNAG_04922 treated portion and the PBS incubated/untreated control portion and the plates were incubated at 37

oC in 5% CO2 overnight. After incubation, the plasma was separated from the cells by centrifugation and stored at -80

oC until analysis.

Cytokines Quantification Assay: Quantification assay was performed at the Immunology Laboratory, Department of Immunology and Molecular Biology, Makerere College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda. The assay was carried out via the Luminex magnetic bead technology using a Luminex xPONENT –LX100/LX200 instrument. The Luminex Human XL Cytokine Premixed kit was obtained from Biotechne, R&D Systems (614 McKinley Place NE Minneapolis, MN 55413, 800 343 7475). Seventeen cytokines and chemokines known to be involved in innate and adaptive immune responses (IL-2, GMCSF, IFNγ, TNFα, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL1-7, MCP1, MIP1α, VEGF) were quantified in duplicate according to the kit manufacturer’s protocol.

Luminex (magnetic bead) assay Procedure:

Human 17-plex kits were purchased from Biotechne, R&D Systems (614 McKinley Place NE Minneapolis, MN 55413, 800 343 7475) and used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, 50ul of the standard, sample or controls were added into each well of the 96-well plate and incubated for 2 hours in a shaker at 800rpm. The plate was washed 3 times using the Wash buffer. After the last wash, 50ul of diluted Biotin-Antibody Cocktail was added to each well, covered, and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature on a shaker at 800 rpm.

The plate was again washed three times using the wash buffer after which 50ul of diluted Streptavidin-PE was added to each well, covered, and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature, shaking at 800rpm. This was followed by final wash cycles where the plates were washed three times using the wash buffer. Finally, 100ul of the wash buffer was added to each well and then incubated at room temperature for two minutes and the plate was read using the Luminex LX100 instrument within 90 minutes of preparation, with a lower bound of 100 beads per sample per cytokine. Each sample was measured in duplicate.

Luminex xPONENT for LX100/200 4.3.309.1 (Luminex Corp.) was used for data acquisition on the Luminex instrument. Analysis output CSV files were analyzed with MILLIPLEX® Analyst 5.1 software (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Sample names and dilution factors were added from an Excel template. Standard wells were designated, and 7-point standard curves were generated with a 5PL (5-parameter logistic) algorithm. A custom report was generated to include both MFI and pg/ml data.

For further statistical analysis, the CSV file was exported to STATA Version 18 software (StataCorp. 2023 Stata Statistical Software: Version 18. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.) from where group descriptive statistics, quartiles, medians and fold-change differences were determined.

Ethical Consideration: Mbarara University of Science and Technology Research Ethics Committee, (MUST-2022-743) and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, UNCST (No. HS3076ES).

3. Results

Participants were recruited into the study after an informed consent process. Blood samples were collected and an ex-vivo cytokines experiment performed on the samples. After 24-hour incubation, the cells were separated and serum/plasma collected and stored at -800C. the serum/plasma were later assayed for the cytokines using a 17-plex cytokine quantification kit (Biotechne, R&D Systems (614 McKinley Place NE Minneapolis, MN 55413, 800 343 7475)

3.1. Participants Demographics

Table 1 below shows a total of 30 participants who were recruited to participate in this study, including 15 HIV -positive individuals and 15- HIV negative volunteers

Table 1, above provides a summary of the demographic and clinical variables in the study population. The age distribution is relatively balanced, with 36.7% of participants aged 0-30 years, 40.0% aged 31-40 years, and 23.3% aged 41 or older. Gender is also evenly distributed, with an equal number of females and males, each representing 50% of the sample. The HIV status is split evenly, with 50% of participants being HIV-positive (HIV+) and the other being HIV-negative (HIV-). Regarding CD4 + count, a higher proportion of participants (66.7%) have CD4 + levels below 100 CD4 + cells/ml and the remainder being above 100 CD4 + cells.

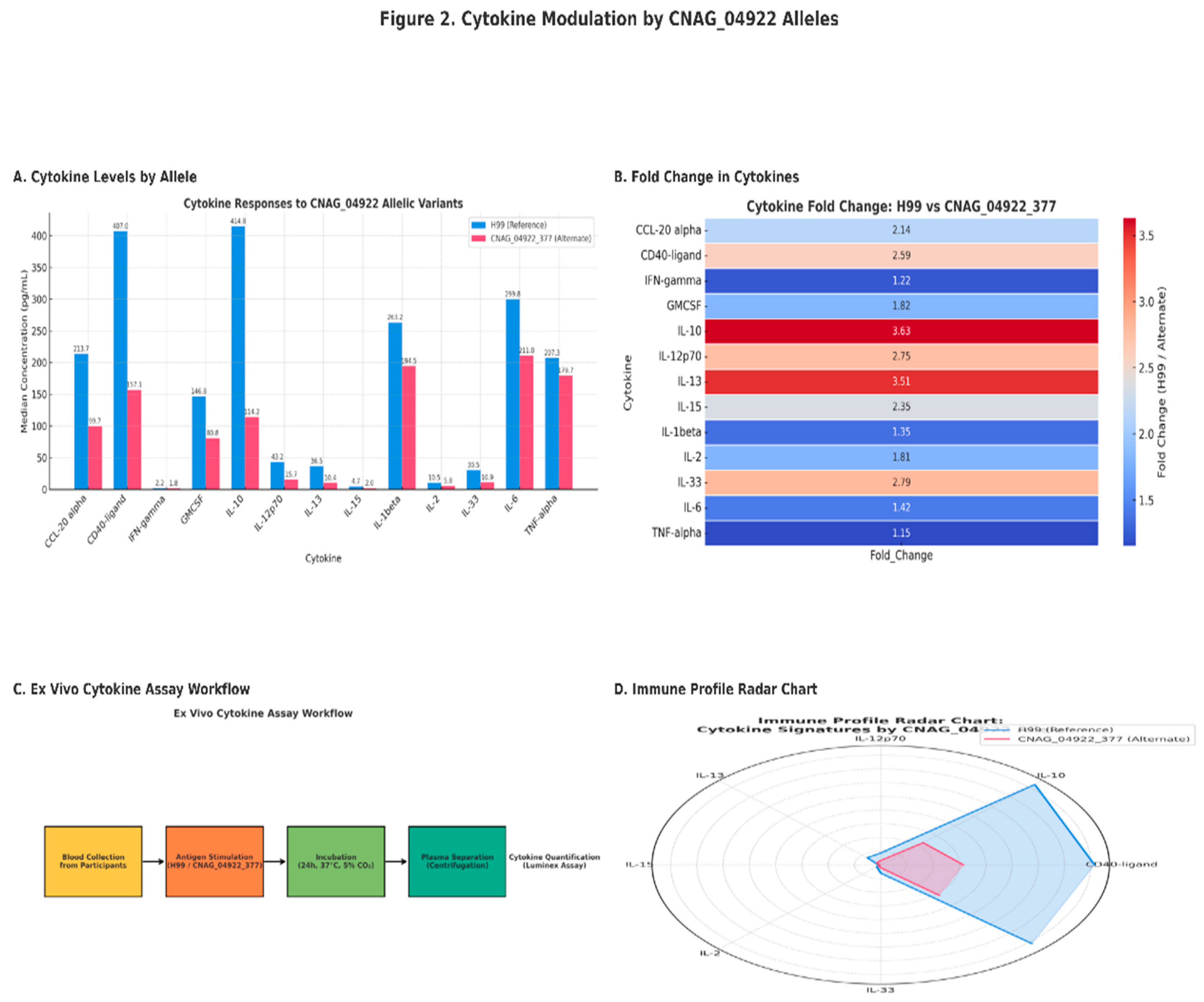

3.2. Cytokine Modulation by CNAG_04922 Alleles

We analyzed total of 17 cytokines and chemokines using the 17-Plex kit obtained from Biotechne, R&D Systems (614 McKinley Place NE Minneapolis, MN 55413, 800 343 7475). however, only 13 cytokines were quantified and the remaining 4 cytokines were not quantified likely due to their concentrations being lower than the lower limit of detection by the assay. The findings are presented in the Figure 2 below

Figure 1: The median cytokine s concentration in response to stimulation by whole cell antigens from (H99 ref strain) and CNAG_04922 alternate allele strain.

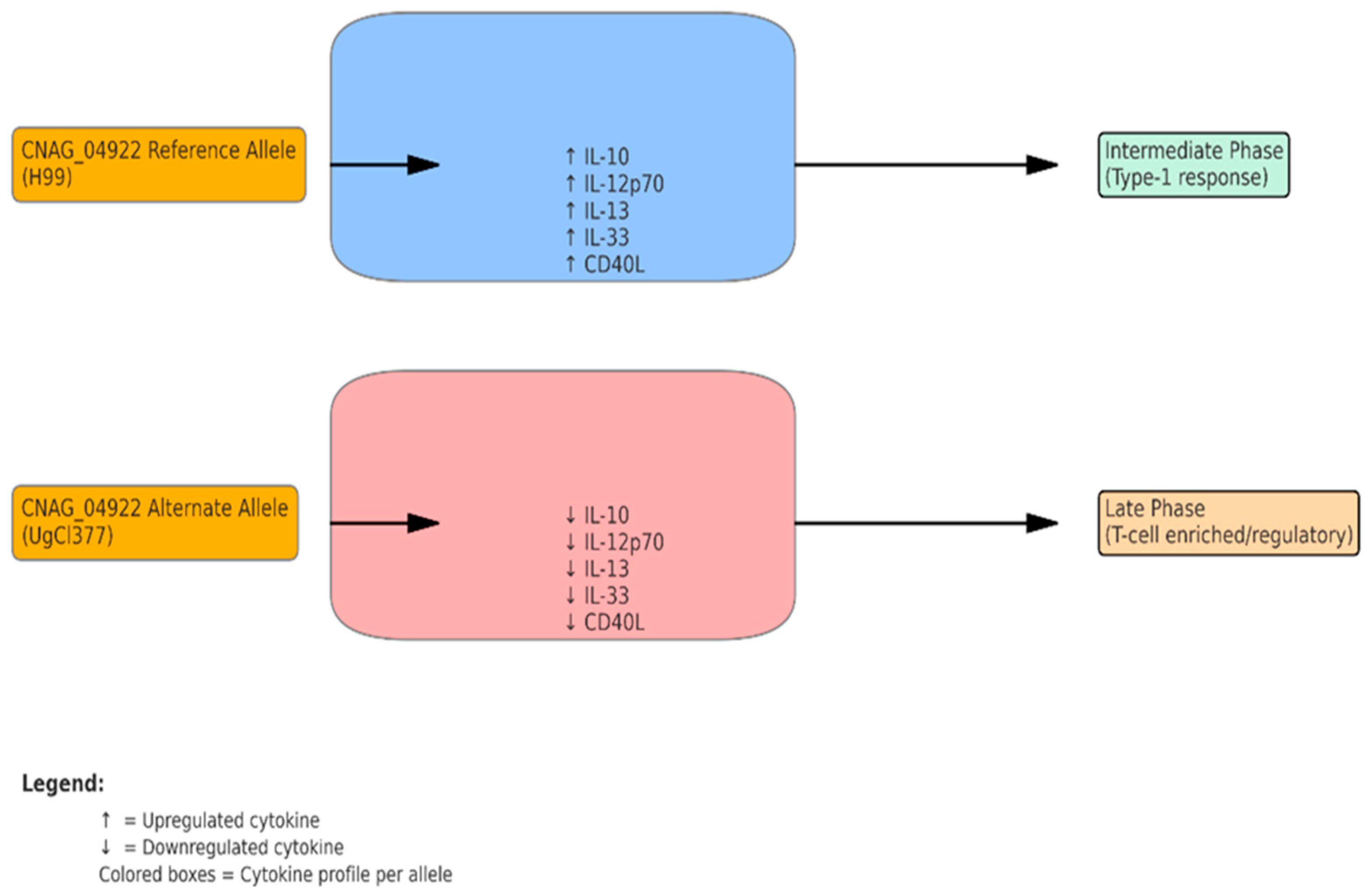

Figure 2: CNAG_04922 shapes cytokine profiles and immune phases in Cryptococcus neoformans infection

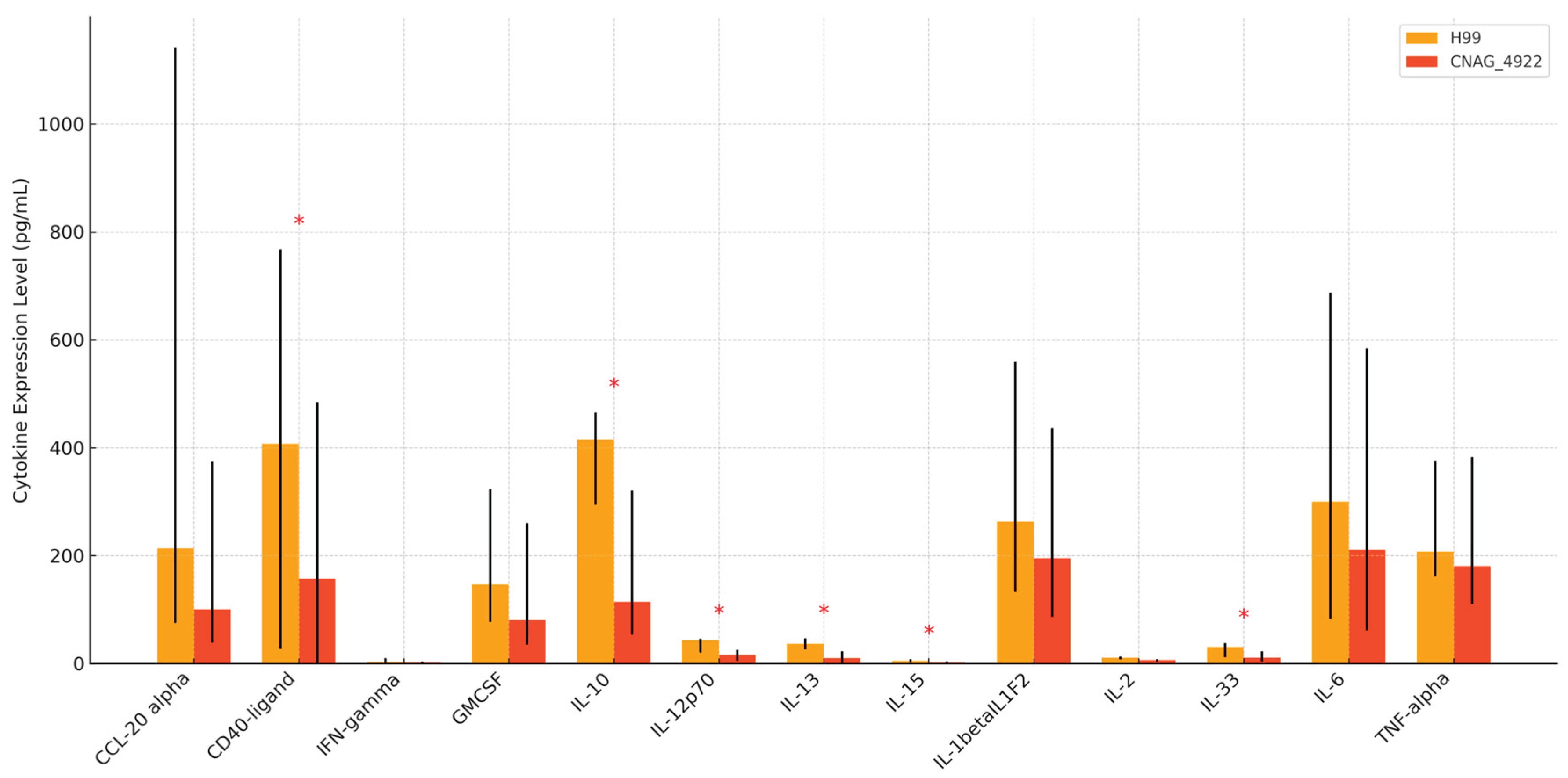

Figure 3: Comparative Cytokine Expression between H99 and CNAG_04922

4. Discussion

Our study focused on the determination of the impact of the alternate allele for CNAG_04922 gene, which was previously shown to be associated with decreased IL-2 levels during cryptococcal meningitis infection, with a resultant favorable outcome for the patients compared to those who had C. neoformans strains carrying CNAG_04922 reference gene alleles. We carried out this study among HIV positive participants with CD4+ cells below 200 cells^3 with equal number of male and female participants aged between 18 - 52years old.

Our findings indicate a moderate decrease in IL-2 levels generally across the participant categories and test antigens, although the decrease is not statistically significant (p=0.068) (

Figure 3). Clinically, these findings emphasize the potential utility of CNAG_04922 genotyping as a prognostic tool and highlight key cytokine pathways—such as IL-10 and IL-12p70—as potential targets for immunomodulatory therapy. However, as our data are derived from ex vivo assays, translation to clinical practice requires validation in vivo and correlation with patient-level outcomes, including fungal burden, IRIS incidence, and survival. The proposed model (

Figure 2) summarizes how CNAG_04922 allelic variation may shape immune responses. The H99 reference allele provokes a strong pro-inflammatory and regulatory cytokine milieu, while the alternate allele leads to a muted response. These differences may impact granuloma formation, pathogen clearance, and clinical outcomes, warranting further in vivo validation in animal models such as C3HeB/FeJ mice [

18], [

19].

In contrast, the CNAG_04922 alternate allele triggered significantly lower cytokine production across the panel, suggesting an immune-dampening effect. This profile may reflect a fungal strategy to evade immune detection or limit inflammation, thereby promoting persistence without triggering strong host responses. Such modulation of immune pathways by fungal genetic variants underscores the complexity of host-pathogen interactions in cryptococcal disease [

20]. The elevated levels of IL-12p70 and CD40-ligand are particularly notable, as they play key roles in initiating and sustaining Th1 responses, which are essential for effective clearance of fungal pathogens such as Cryptococcus [

21,

22]. Similarly, increased IL-13 and IL-33, often associated with Th2 responses, may indicate a mixed Th1/Th2 immune signature. The high IL-10 levels suggest a compensatory regulatory mechanism designed to moderate excessive inflammation, aligning with earlier findings that robust IL-10 responses can improve CM outcomes [

23,

24].

The findings demonstrate that allelic variation in CNAG_04922 significantly influences host cytokine responses during Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Specifically, stimulation with the H99 reference allele led to significantly higher levels of CD40-ligand (p = 0.047), IL-10 (p = 0.028), IL-12p70 (p < 0.001), IL-13 (p < 0.001), IL-15 (p = 0.009), and IL-33 (p = 0.006) compared to the alternate CNAG_04922 allele. These cytokines span both pro-inflammatory and regulatory domains, reflecting the capacity of H99 to induce a broad immune activation pattern [

25]. The findings further reinforce the growing understanding that fungal genetic variation significantly influences host-pathogen dynamics in cryptococcal meningitis (CM) [

26,

27,

28]. Notably, the CNAG_04922 reference allele strain H99 elicited significantly higher cytokine levels—including CD40-ligand, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-15, and IL-33—compared to the alternate allele strain. These cytokines are associated with Th1 (IL-12p70, CD40L), Th2 (IL-13, IL-33), and regulatory (IL-10) responses, indicating a broad immune activation profile linked to H99.

Elevated IL-12p70 levels suggest enhanced Th1 polarization, which is crucial for IFN-γ production and control of fungal pathogens [

29]. Similarly, IL-13 and IL-33 are involved in Th2 and tissue-repair responses, while IL-10 functions as a regulatory cytokine that tempers inflammation and mitigates immunopathology [

30,

31]. These dynamics align with earlier studies linking cytokine profiles to clinical outcomes in CM [

32]. The cytokine expression pattern induced by H99 suggests robust immune stimulation with potential for both protective and pathological consequences [

33,

34]. As observed earlier, the CNAG_04922 alternate allele induced significantly lower cytokine responses. This muted profile may reflect an immune evasion mechanism that promotes fungal persistence or tolerance, especially in immunocompromised hosts [

35,

36]. These findings are consistent with prior reports associating CNAG_04922 allelic variants with reduced IL-2 levels and altered patient outcomes [

37]. The proposed model (

Figure 3) illustrates how these immunomodulatory shifts could influence granuloma structure, pathogen burden, and host outcome.

Clinically, the strong IL-10 and IL-12p70 responses to the H99 strain may offer therapeutic targets for modulating immune responses in CM [

29]. IL-10, in particular, has shown dual roles in protecting against IRIS and facilitating fungal clearance depending on the context [

38]. Genotyping C. neoformans isolates for CNAG_04922 alleles may have prognostic value and guide personalized treatment strategies. Nevertheless, translation of these findings into clinical practice requires in vivo validation using models that capture the full spectrum of CM pathophysiology.

Future research should investigate the mechanistic pathways linking CNAG_04922 to cytokine modulation using in vivo models such as C3HeB/FeJ mice [

19]. Additional studies exploring how host immune status (e.g., CD4 count) interacts with fungal genotype could clarify the immunopathogenesis of CM. A deeper understanding of host-pathogen interactions at the genomic and immunological levels may ultimately improve patient outcomes through tailored interventions.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that allelic variation in CNAG_04922 significantly alters host cytokine responses during C. neoformans infection. The H99 strain, carrying the reference allele, elicits a broad, heightened cytokine response, while the alternate allele variant results in diminished immune activation. These findings suggest that fungal genetic variability contributes to differential host-pathogen dynamics and may inform risk stratification and therapeutic strategies. Future in vivo studies, especially using C3HeB/FeJ mice, are necessary to validate these immune patterns and their clinical implications in cryptococcal meningitis.[

39]

Author Contributions

KK, KN, and JB developed the study concept. KK developed the study design. KN provided access to the clinical isolates and reference strains. KK drafted the manuscript, KN, KK, JB, and WF provided inputs into the laboratory methods and Manuscript review. All authors read and provided input on the manuscript and agreed with the final version.

Funding

This research was funded by The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the Fogarty International Center (FIC) grant support this study No. R01NS118538.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee(REC) of Mbarara University of Science and Technology (protocol code MUST-2022-743, on 03/02/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the Fogarty International Center (FIC) grant support this study No. R01NS118538. The authors also acknowledge the study collaborators from the University of Minnesota (USA), Makerere University (UG), National Health Laboratory services (UNHLS) and Mbarara University of Science and Technology (UG).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- S. Okurut, D. R. Boulware, J. Olobo, and D. B. Meya, “Landmark clinical observations and immunopathogenesis pathways linked to HIV and Cryptococcus fatal central nervous system co-infection,” Mycoses, vol. 63, no. 8, pp. 840–853, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Rajasingham et al., “The global burden of HIV-associated cryptococcal infection in adults in 2020: a modelling analysis,” The Lancet Infectious Diseases, vol. 22, no. 12, pp. 1748–1755, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Bicanic et al., “Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: a prospective study,” J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 130–134, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- K. Kassaza, F. Wasswa, K. Nielsen, and J. Bazira, “Cryptococcus neoformans Genotypic Diversity and Disease Outcome among HIV Patients in Africa,” Journal of Fungi, vol. 8, no. 7, Art. no. 7, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. B. Burgess, A. M. Condliffe, and P. M. Elks, “A Fun-Guide to Innate Immune Responses to Fungal Infections,” J Fungi (Basel), vol. 8, no. 8, p. 805, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “Roles of Different Signaling Pathways in Cryptococcus neoformans Virulence.” Accessed: Apr. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2309-608X/10/11/786.

- T. R. Kozel, “Virulence factors of Cryptococcus neoformans,” Trends Microbiol, vol. 3, no. 8, pp. 295–299, Aug. 1995. [CrossRef]

- V. Chaturvedi, T. Flynn, W. G. Niehaus, and B. Wong, “Stress tolerance and pathogenic potential of a mannitol mutant of Cryptococcus neoformans,” Microbiology (Reading), vol. 142 ( Pt 4), pp. 937–943, Apr. 1996. [CrossRef]

- K. Nielsen et al., “Cryptococcus neoformans {alpha} strains preferentially disseminate to the central nervous system during coinfection,” Infect Immun, vol. 73, no. 8, pp. 4922–4933, Aug. 2005. [CrossRef]

- K. Nielsen, G. M. Cox, P. Wang, D. L. Toffaletti, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman, “Sexual cycle of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii and virulence of congenic a and alpha isolates,” Infect Immun, vol. 71, no. 9, pp. 4831–4841, Sep. 2003. [CrossRef]

- K. Nielsen et al., “Interaction between genetic background and the mating-type locus in Cryptococcus neoformans virulence potential,” Genetics, vol. 171, no. 3, pp. 975–983, Nov. 2005. [CrossRef]

- X. Lin, S. Patel, A. P. Litvintseva, A. Floyd, T. G. Mitchell, and J. Heitman, “Diploids in the Cryptococcus neoformans Serotype A Population Homozygous for the α Mating Type Originate via Unisexual Mating,” PLoS Pathog, vol. 5, no. 1, p. e1000283, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Gerstein et al., “Identification of Pathogen Genomic Differences That Impact Human Immune Response and Disease during Cryptococcus neoformans Infection,” mBio, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. e01440-19, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Sharma, S. Mudalagiriyappa, and S. G. Nanjappa, “T cell responses to control fungal infection in an immunological memory lens,” Front Immunol, vol. 13, p. 905867, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. E. Fernandes, J. A. Fraser, and D. A. Carter, “Lineages Derived from Cryptococcus neoformans Type Strain H99 Support a Link between the Capacity to Be Pleomorphic and Virulence,” mBio, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. e00283-22. [CrossRef]

- K. E. Fernandes, J. A. Fraser, and D. A. Carter, “Lineages Derived from Cryptococcus neoformans Type Strain H99 Support a Link between the Capacity to Be Pleomorphic and Virulence,” mBio, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. e00283-22. [CrossRef]

- D. L. Wiesner et al., “Cryptococcal genotype influences immunologic response and human clinical outcome after meningitis,” mBio, vol. 3, no. 5, pp. e00196-12, 2012. [CrossRef]

- “Pulmonary granuloma formation during latent Cryptococcus neoformans infection in C3HeB/FeJ mice involves progression through three immunological phases | mBio.” Accessed: Apr. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/mbio.03610-24.

- “Pulmonary granuloma formation during latent Cryptococcus neoformans infection in C3HeB/FeJ mice involves progression through three immunological phases | mBio.” Accessed: May 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/mbio.03610-24.

- J. Xu, P. R. Wiliamson, M. A. Olszewski, J. Xu, P. R. Wiliamson, and M. A. Olszewski, “<em>Cryptococcus neoformans</em>-Host Interactions Determine Disease Outcomes,” in Fungal Infection, IntechOpen, 2019. [CrossRef]

- I. Vlasova-St. Louis and H. Mohei, “Molecular Diagnostics of Cryptococcus spp. and Immunomics of Cryptococcosis-Associated Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome,” Diseases, vol. 12, no. 5, p. 101, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Xu et al., “Chemokine and Cytokine Cascade Caused by Skewing of the Th1-Th2 Balance Is Associated with High Intracranial Pressure in HIV-Associated Cryptococcal Meningitis,” Mediators of Inflammation, vol. 2019, pp. 1–9, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- “IL-33 and IL-33 Receptors in Host Defense and Diseases,” Allergology International, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 143–160, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- F. Sheng et al., “IL-33/ST2 axis in diverse diseases: regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic potential,” Front. Immunol., vol. 16, p. 1533335, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. E. Fernandes, J. A. Fraser, and D. A. Carter, “Lineages Derived from Cryptococcus neoformans Type Strain H99 Support a Link between the Capacity to Be Pleomorphic and Virulence,” mBio, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. e00283-22. [CrossRef]

- A. J. P. Brown, “Fungal resilience and host–pathogen interactions: Future perspectives and opportunities,” Parasite Immunology, vol. 45, no. 2, p. e12946, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Jackson et al., “Single nucleotide polymorphisms are associated with strain-specific virulence differences among clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans,” Nat Commun, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 10491, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Coelho and R. A. Farrer, “Pathogen and host genetics underpinning cryptococcal disease,” Adv Genet, vol. 105, pp. 1–66, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Leopold Wager, C. R. Hole, K. L. Wozniak, and F. L. Wormley, “Cryptococcus and Phagocytes: Complex Interactions that Influence Disease Outcome,” Front. Microbiol., vol. 7, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- U. Müller et al., “IL-13 induces disease-promoting type 2 cytokines, alternatively activated macrophages and allergic inflammation during pulmonary infection of mice with Cryptococcus neoformans,” J Immunol, vol. 179, no. 8, pp. 5367–5377, Oct. 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. Gu et al., “The production, function, and clinical applications of IL-33 in type 2 inflammation-related respiratory diseases,” Front. Immunol., vol. 15, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Jn et al., “Cerebrospinal fluid cytokine profiles predict risk of early mortality and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis,” PLoS pathogens, vol. 11, no. 4, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang et al., “Robust Th1 and Th17 Immunity Supports Pulmonary Clearance but Cannot Prevent Systemic Dissemination of Highly Virulent Cryptococcus neoformans H99,” Am J Pathol, vol. 175, no. 6, pp. 2489–2500, Dec. 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Hardison, S. Ravi, K. L. Wozniak, M. L. Young, M. A. Olszewski, and F. L. Wormley, “Pulmonary Infection with an Interferon-γ-Producing Cryptococcus neoformans Strain Results in Classical Macrophage Activation and Protection,” The American Journal of Pathology, vol. 176, no. 2, pp. 774–785, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Hernández-Chávez, L. A. Pérez-García, G. A. Niño-Vega, and H. M. Mora-Montes, “Fungal Strategies to Evade the Host Immune Recognition,” J Fungi (Basel), vol. 3, no. 4, p. 51, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Lange, L. Kasper, M. S. Gresnigt, S. Brunke, and B. Hube, “‘Under Pressure’ – How fungi evade, exploit, and modulate cells of the innate immune system,” Semin Immunol, vol. 66, p. 101738, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Gerstein et al., “Identification of Pathogen Genomic Differences That Impact Human Immune Response and Disease during Cryptococcus neoformans Infection,” mBio, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. e01440-19, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Xu, P. Wiliamson, and M. Olszewski, “Cryptococcus neoformans-Host Interactions Determine Disease Outcomes,” 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, Z. Shi, A. Strickland, and M. Shi, “Cryptococcus neoformans Infection in the Central Nervous System: The Battle between Host and Pathogen,” Journal of Fungi — Open Access Mycology Journal, vol. 8, p. 1069, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).