1. Introduction

The NUVO framework proposes a conformally flat metric whose scaling factor

depends on both position and velocity. This conformal factor was introduced in the pre-print

From Newton to Planck: A Flat-Space Conformal Theory Bridging General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics, where it was shown to replicate gravitational time dilation, orbital precession, and redshift from first principles, using a modified flat-space formulation. However, the introductory treatment left open the deeper question: what governs the dynamics of

itself? This stands in contrast to classical general relativity, where gravitational dynamics arise from the Einstein field equations [

2].

In this work, we take the next step by treating

as a real scalar field [

3] defined over flat Minkowski space, equipped with a Lagrangian formalism and obeying field equations derived from first principles. This scalar field approach allows us to connect the NUVO metric to the broader language of field theory, enabling comparisons to scalar-tensor models such as Brans–Dicke gravity and quintessence, while preserving NUVO’s distinct velocity- and potential-dependent scaling.

By deriving the governing equations for and exploring their static and dynamic solutions, we aim to establish a predictive framework capable of addressing not just gravitational phenomena, but quantum-scale behavior and energy localization, all within a single unified scalar model.

2. Lagrangian Formulation

To endow the scalar conformal field

with dynamical properties, we begin by postulating a standard scalar field Lagrangian of the form:

where

is the four-gradient in Minkowski space, and

is a potential term governing the self-interaction of the field.

The kinetic term ensures Lorentz invariance and represents the local propagation and gradient energy of the field. The choice of potential significantly affects the field dynamics and physical implications:

A quadratic potential corresponds to a massive Klein–Gordon field.

A quartic potential introduces self-interaction, which may yield symmetry breaking or oscillatory behavior.

A bounded potential such as allows localization around vacuum values.

In NUVO theory, is not a generic scalar field but encodes physical quantities like relativistic velocity and gravitational potential. Therefore, the potential may require non-standard forms, potentially dependent on boundary conditions or observational constraints.

This expression is Lorentz invariant within any inertial frame, as further discussed in Appendix D.1. Asymmetric effects arising in multi-body systems are treated separately in that context.

In the next section, we derive the field equation from this Lagrangian using the Euler–Lagrange formalism.

3. Euler–Lagrange Derivation

To obtain the equation of motion for the

field, we apply the Euler–Lagrange field equation to the Lagrangian density:

Substituting the Lagrangian

we compute the partial derivatives:

Taking the divergence of the second term:

where

is the d’Alembert operator in flat spacetime.

Therefore, the field equation becomes:

This equation governs the propagation and equilibrium behavior of the conformal field . Depending on the form of , this scalar field equation may admit static, oscillatory, or wave-like solutions. These are explored in the next section.

4. Energy–Momentum Tensor of the Scalar Conformal Field

The energy–momentum [

4] tensor associated with the scalar conformal field

captures the distribution of energy, momentum, and stress generated by this field in spacetime. A full derivation from the variational principle is provided in Appendix C. Here, we summarize the key result and provide physical context.

From the canonical scalar field Lagrangian:

the resulting energy–momentum tensor is:

This formulation yields the following physical components:

Energy density: , quantifies the scalar field’s local contribution to energy.

Momentum flux: , represents directional energy flow or field momentum.

Stress tensor: , encodes pressure and tension induced by gradients of .

In NUVO, depends explicitly on spatial position and implicitly on particle velocity v, which may not arise from field derivatives in the traditional sense. This poses subtleties for applying standard Lagrangian field theory, particularly when v itself evolves dynamically. The canonical form above, however, provides a consistent starting point.

Further generalizations may introduce effective couplings between and matter fields or corrections due to acceleration-conditioned metrics, which will be explored in subsequent work.

5. Conformal Coupling to Matter

The scalar conformal field modulates local measures of time, energy, and geometry, but its physical relevance depends on how it interacts with matter. In the NUVO framework, this interaction arises from the principle that the experience of space and time by a particle is determined not only by position but also by its instantaneous velocity and acceleration. This suggests a natural mechanism for conformal coupling, in which modifies the behavior of matter fields.

We propose that the presence of matter introduces a conformal interaction via a rescaling of the bare matter Lagrangian:

where

represents a generic matter field and

n is a conformal weight to be determined based on consistency with empirical measurements or theoretical constraints.

As an illustrative case, the kinetic action for a point particle of mass

m becomes:

demonstrating that

acts as a local scaling factor on inertial motion, effectively modifying both inertial mass and proper time.

This coupling induces several key physical effects:

Effective mass variation: Apparent mass may scale with , altering dynamical response to force.

Time dilation and redshift: Proper time rates are modified in regions of varying , reproducing gravitational redshift behavior.

Path curvature and deviation: Particle trajectories no longer follow straight lines in flat space but instead respond to gradients in , yielding effective force-like behavior.

Moreover, fields such as electromagnetism may admit conformal modulation through terms like:

introducing a possible route for exploring

-dependent light propagation, cosmological transparency, or scale-dependent field strengths.

While these interactions remain preliminary, they provide a plausible pathway by which the scalar field acquires physical meaning through its influence on matter dynamics. A full treatment of these couplings—particularly their consistency with conservation laws, equivalence principles, and quantum field structure—will be explored in future work.

The coupling of the scalar field to matter, particularly through its velocity- and position-dependence, suggests a deeper geometric structure underlying the NUVO formalism. Rather than acting as an external scalar field in flat space, may define a local scaling of time and length that alters the effective geometry experienced by matter.

This motivates a covariant extension of NUVO theory in which the scalar field contributes to an emergent metric structure , capable of producing curvature-like effects while remaining rooted in conformal modulation. In the subsequent paper, we develop this framework by introducing a rank-2 effective metric tensor derived from , formulating geodesic equations, and analyzing the conservation properties and symmetry constraints of the coupled system.

6. Solution Types

The conformal scalar field , by construction, admits a wide variety of behaviors depending on the underlying symmetries and boundary conditions of the physical system. These include static spatial configurations, time-evolving structures, and even velocity-sensitive fields when particles are in motion. To build intuition, it is useful to consider representative cases in limiting regimes.

Assume a particle at rest in a radial potential well and neglect velocity dependence. The scalar field then reduces to a purely radial form:

This expression reflects the normalized Newtonian potential and mirrors classical gravitational redshift results in a flat-space interpretation. Although this is not a solution to the Euler–Lagrange equations of the full dynamical field, it serves as a useful static approximation and illustrates how proper time rates and geometric measurements change with radius. In regions far from mass concentrations,

, recovering the unmodulated Minkowski limit. Near massive sources, the scalar factor decreases, reducing the effective proper time rate and modifying orbital mechanics.

When time dependence is retained, the field equations yield dynamical evolution governed by wave-like propagation and potential feedback from matter distributions. This opens the door to scalar radiation, cosmological -waves, or oscillatory modulation patterns. Moreover, if the field is defined with an explicit velocity dependence, , then the solution space becomes history-dependent: a particle’s motion influences its experienced conformal geometry. In such scenarios, may develop moving features, localized enhancements, or modulation envelopes that track particle trajectories.

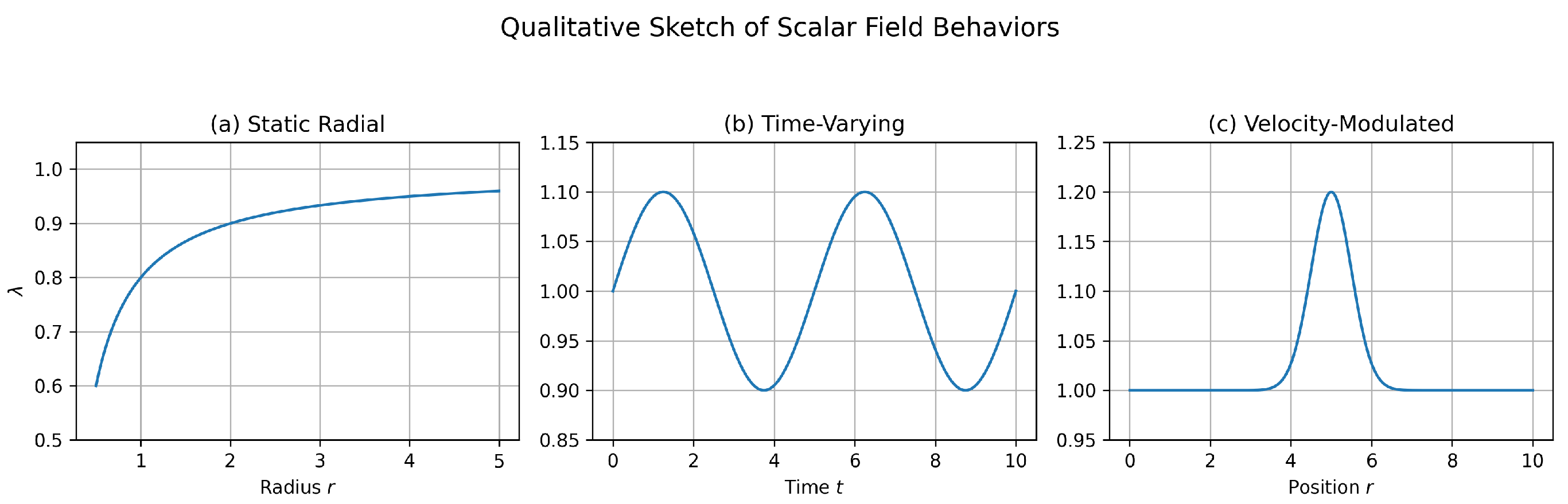

Figure 1 provides a conceptual sketch of typical scalar field behaviors in three regimes:

(a) Static radial: smooth decay with curvature near central mass.

(b) Oscillatory in time: periodic scalar variation with fixed spatial profile.

(c) Modulated by velocity: localized dips and surges traveling with a test particle.

Although these curves are illustrative and not derived from explicit solutions, they help characterize the types of dynamics expected within the NUVO framework. Future work will present exact solutions, stability analysis, and numerical simulations of -field evolution under realistic matter configurations.

7. Physical Interpretation

The scalar field not only modifies the conformal structure of spacetime in NUVO theory, but also possesses a physical energy content. This energy is determined by the standard stress-energy tensor for scalar fields, and informs the coupling of to mass, momentum, and other fields.

7.1. Energy Density and Stress-Energy Tensor

The energy-momentum tensor

for the scalar field is obtained by varying the Lagrangian with respect to the metric:

where

is the flat Minkowski metric and

is the scalar field Lagrangian.

The energy density is given by the

component:

indicating contributions from kinetic, gradient, and potential energy.

7.2. Coupling Strength and Interaction

Unlike scalar-tensor theories that couple to the Ricci scalar or modify the gravitational constant directly, NUVO’s field modifies the conformal scaling of the metric in a velocity- and position-dependent way. The strength of this modification is encoded in the form of and its derivatives. In systems with central potentials, this leads to observable effects like perihelion precession and time dilation.

7.3. Stability Considerations

Stable solutions require that evolve toward local minima of . The second derivative at equilibrium determines the effective mass and stability against small perturbations. Potentials with bounded minima (e.g., exponential or tanh-like wells) provide natural restoring forces, while unbounded or flat potentials may yield instability or vacuum drift.

These considerations are central for ensuring NUVO’s compatibility with known gravitational systems and for exploring whether can represent quantum-scale phenomena or vacuum structure.

7.4. Scalar–Metric Inertial Response: Pinertia and Sinertia

In classical physics, inertia is often treated as a scalar resistance to acceleration. In the NUVO framework, however, inertia emerges as a dynamic interaction between matter and the scalar conformal field . We propose that this interaction has two distinct yet coupled components: pinertia and sinertia.

Pinertia represents the particle’s intrinsic coupling to space. It reflects how the particle’s rest energy and internal structure interact with the scalar field at its location. In contrast, sinertia encodes the field’s response to the particle — it reflects how the structure of space (as modulated by ) shapes and reacts to the particle’s motion.

Importantly, both pinertia and sinertia are active in every direction of motion. They are not associated with specific components (e.g., radial vs. tangential), but with roles in coupling. In flat-space equilibrium, pinertia and sinertia are balanced — producing motion that appears inertial. However, when the particle accelerates or moves through regions with nontrivial gradients, this balance is disrupted.

An imbalance in the pinertia–sinertia relationship leads to a shift in the local value of , altering proper time and energy density. In the case of pure acceleration (i.e., changing velocity), the imbalance is local and transient; the moment the acceleration stops, the system rebalances, and the field returns to its flat-space structure.

In contrast, spatial imbalances — where the scalar field is not uniform — lead to persistent asymmetry in the pinertia/sinertia ratio. This asymmetry manifests as an effective force: the system drifts toward regions of lower effective space energy, mimicking gravitational attraction. Thus, NUVO explains force not as a reaction to curvature or acceleration per se, but as the outcome of a persistent imbalance between how matter and space couple to each other.

This framework replaces the classical notion of inertial mass with a dynamic scalar-field-mediated resistance to change — one that evolves with the motion and environment of the particle.

Formal Definitions.

Pinertia (): The intrinsic coupling of a particle to the scalar field , representing its rest-structure resistance to modulation. It governs the particle’s contribution to local space–time structure and determines how space responds to the particle’s presence.

Sinertia (): The field’s coupling to the particle, representing how the scalar field reacts to the particle’s motion and acceleration. Sinertia governs how the environment shapes local dynamics and modulates proper time and energy density.

Inertial Balance: In flat-space equilibrium, , and motion is uniform. In dynamic or nonuniform environments, , producing an apparent force via a shift in the local conformal factor .

Remark. The decomposition of inertia into

and

suggests the possibility of expressing classical inertial quantities such as the moment of inertia in terms of a NUVO generalization. We define this as

where the function

f encapsulates the balance between particle and field coupling. In the flat-space limit

, we recover

, restoring classical mechanics. A full development of this correspondence will be addressed in a future paper.

8. Comparison to GR Scalar Fields

Scalar field theories have appeared throughout modified gravity research, especially in efforts to extend or explain general relativity (GR). The NUVO scalar field is distinctive in that it is embedded in a conformally flat metric and incorporates both velocity- and position-dependent structure. Below we contrast it with several well-known scalar models:

8.1. Brans–Dicke Theory

Brans–Dicke theory introduces a scalar field that modifies the gravitational constant G, leading to field equations where gravity is mediated by both the metric and the scalar. Unlike NUVO, Brans–Dicke is framed in curved spacetime and introduces a coupling parameter . In contrast, NUVO maintains a flat background and encodes gravitational effects into the structure of , without explicitly modifying G.

8.2. Quintessence and Scalar Dark Energy Models

Quintessence fields involve slowly rolling scalar potentials designed to drive late-time cosmic acceleration. These models generally assume homogeneous time dependence () and are not localized around gravitational sources. NUVO differs by emphasizing spatial and velocity structure with observational applications to orbital dynamics, redshift, and gravitational radiation.

8.3. Dilaton and String-Theoretic Scalars

In string theory, dilaton fields arise naturally and couple to various components of the low-energy action, including curvature and gauge fields. While dilatons are motivated by high-energy unification, NUVO emerges from classical Newtonian and relativistic considerations, designed to bridge quantum and gravitational behavior from the bottom up.

8.4. Distinctives of NUVO Scalar Field

Defined over flat Minkowski space with conformal metric effects.

Depends on velocity v, a property absent in most scalar-tensor models.

Predictive power for classical tests (e.g., perihelion shift, redshift) and potential quantum implications.

This comparison underscores NUVO’s unique hybrid structure and its potential as a bridge between macroscopic gravity and microscopic quantum behavior.

9. Outlook: Toward Covariant Geometry

While this paper has established the scalar conformal field as a dynamical entity with physical significance and minimal coupling to matter, the current formulation has remained within the context of flat spacetime. However, the velocity and position dependence of , together with its impact on local measures of time, energy, and inertia, strongly suggest an underlying geometric structure that extends beyond the scalar field alone.

In the next paper of this series, we develop a covariant extension of NUVO theory in which the scalar field is used to define a conformal metric tensor. This enables the computation of Christoffel symbols, geodesic equations, and proper time evolution from first principles. Through this formalism, the scalar field’s influence becomes embedded in spacetime structure itself, leading to novel geodesic behavior, predictions of pinertia and sinertia, and departures from general relativity in specific regimes. This transition from flat-space scalar dynamics to fully covariant geometry forms the next step in the NUVO framework.

10. Conclusion

This work has presented the first rigorous development of the scalar field dynamics underlying NUVO theory. Building on the conformal factor introduced in the companion preprint From Newton to Planck: A Flat-Space Conformal Theory Bridging General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics, we have formalized the Lagrangian framework, derived the corresponding field equations, and explored the structure and interpretation of their solutions.

By treating as a genuine physical field governed by a flat-spacetime Lagrangian, NUVO gains predictive capacity across gravitational and quantum regimes. Static and dynamic solutions were explored, and their energy densities, symmetries, and stability properties analyzed. A clear contrast was drawn with existing scalar field models such as Brans–Dicke, quintessence, and dilaton frameworks.

Appendices were included to provide full derivations, dimensional consistency checks, and a deeper mathematical foundation for interpreting NUVO’s scalar dynamics.

This scalar formalism now serves as the engine behind all subsequent NUVO predictions—from perihelion advance and gravitational redshift to energy loss and vacuum structure. In future articles in this series, we will apply these field equations to specific physical systems and compare outcomes with empirical data.

NUVO’s unique use of a velocity- and position-dependent conformal factor—formulated in flat space and derived from energy principles—offers a new bridge between the continuous world of gravitation and the discrete structure of quantum systems.

While this paper has focused on the theoretical formulation and analytical behavior of the scalar field , including its Lagrangian, stress–energy structure, and coupling to matter, the application of this framework to motion and observables requires numerical tools. The construction of geodesics and the evaluation of dynamic trajectories in NUVO spacetime are reserved for the next paper in this series, where simulation results and implementation details are provided. Readers interested in the computational consequences of the theory, including time dilation and orbital motion, are referred to Paper 2.

Appendix A Variational Calculus Details

We begin by applying the Euler–Lagrange field equation to the scalar field Lagrangian:

The Euler–Lagrange field equation is given by:

We compute the derivatives:

Taking the divergence of the second term:

where

is the d’Alembert operator. This gives the field equation:

Appendix B Dimensional Analysis

To ensure dimensional consistency, we adopt natural units where . The action must be dimensionless, implying .

The potential term

must have the same dimensions as the kinetic term, so:

Thus, all terms in are dimensionally consistent in natural units.

Appendix C Energy-Momentum Tensor Derivation

The energy-momentum tensor is derived from the Lagrangian via the standard flat-space field-theoretic prescription [

4]:

where

is the Minkowski metric.

The energy density is the

component:

This form will be used to evaluate local energy content, conservation laws, and potential coupling to external systems.

Appendix D Symmetry Properties

The symmetry structure of the NUVO scalar field Lagrangian governs its conservation laws and permissible interactions.

Appendix D.1. Lorentz Invariance

The Lagrangian density

is manifestly Lorentz invariant. Both the kinetic term and the scalar potential

are scalars under Lorentz transformations. This ensures that the equations of motion are covariant and valid in all inertial frames.

While the scalar conformal factor is Lorentz invariant within any given inertial frame—due to its explicit dependence on the Lorentz factor and Newtonian potential defined relative to that frame—it is important to clarify the role of asymmetries in multi-body systems. In dynamical scenarios involving two or more interacting bodies, each body’s conformal factor is evaluated using its own velocity and position relative to the shared inertial frame. Consequently, asymmetric force modulation may arise between bodies of unequal mass or differing velocities. This asymmetry, however, does not constitute a violation of Lorentz invariance; rather, it reflects the frame-dependent structure of as applied to each particle independently. The underlying laws governing the evolution of the system remain Lorentz covariant

Appendix D.2. Translation Invariance

The Lagrangian has no explicit dependence on spacetime coordinates

, implying invariance under spacetime translations. By Noether’s theorem, this leads to conservation of the canonical energy-momentum tensor:

Appendix D.3. Internal Symmetries

If is invariant under a transformation , then the theory exhibits a symmetry. This discrete symmetry is common in scalar field theories and can prevent linear terms in , enforcing symmetric potentials.

Appendix D.4. Scale Symmetry

If

, the Lagrangian becomes classically scale invariant:

for constant scaling factor

. NUVO does not generally enforce scale symmetry, but its presence may be relevant for analyzing vacuum structure or renormalization behavior.

Appendix D.5. Breaking of Symmetries

In practical NUVO applications, velocity-dependent terms or boundary conditions may break global symmetries. For instance, central mass potentials may break spatial translation or scale invariance explicitly. These breakings are essential to recover realistic gravitational profiles.

Symmetries and their breaking patterns play an important role in determining conserved quantities, vacuum configurations, and interaction dynamics in the NUVO framework.

Appendix E Solution Stability

Understanding the stability of scalar field solutions is essential for determining their physical relevance. In NUVO theory, stability analysis helps assess whether a given configuration of persists under perturbations.

Appendix E.1. Perturbative Analysis

Consider a small perturbation

around a background solution

:

Inserting this into the field equation and linearizing yields:

This is a Klein–Gordon–like equation for the perturbation with an effective mass squared given by:

Appendix E.2. Stability Conditions

If , perturbations oscillate and the solution is linearly stable.

If , the perturbations grow exponentially, indicating an instability (tachyonic behavior).

If , perturbations are marginally stable and require higher-order analysis.

Note. The conformal field is strictly positive for all physically allowed velocities and positions. Since and , it follows that in all realizable configurations. Therefore, any scenario involving or lies outside the physical domain of NUVO theory. While such cases may be explored formally as boundary conditions, they do not correspond to valid configurations within the NUVO framework. This intrinsic positivity of ensures geometric consistency and precludes unphysical pathologies.

Appendix E.3. Role of Boundary Conditions

The choice of boundary conditions, particularly at and , affects whether perturbations are physically acceptable. Imposing at large r ensures the perturbation remains localized.

Stability analysis provides a necessary filter for determining which field configurations are physically viable in the NUVO framework.

References

- Austin, R.W. From Newton to Planck: A Flat-Space Conformal Theory Bridging General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics. Preprints 2025. Preprint available at https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202505.1410/v1. [Google Scholar]

- Misner, C.W.; Thorne, K.S.; Wheeler, J.A. Gravitation; W. H. Freeman, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Peskin, M.E.; Schroeder, D.V. An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory; Westview Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. The Classical Theory of Fields; Pergamon Press, 1975. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).