Submitted:

23 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Senescence and Associated Mechanisms

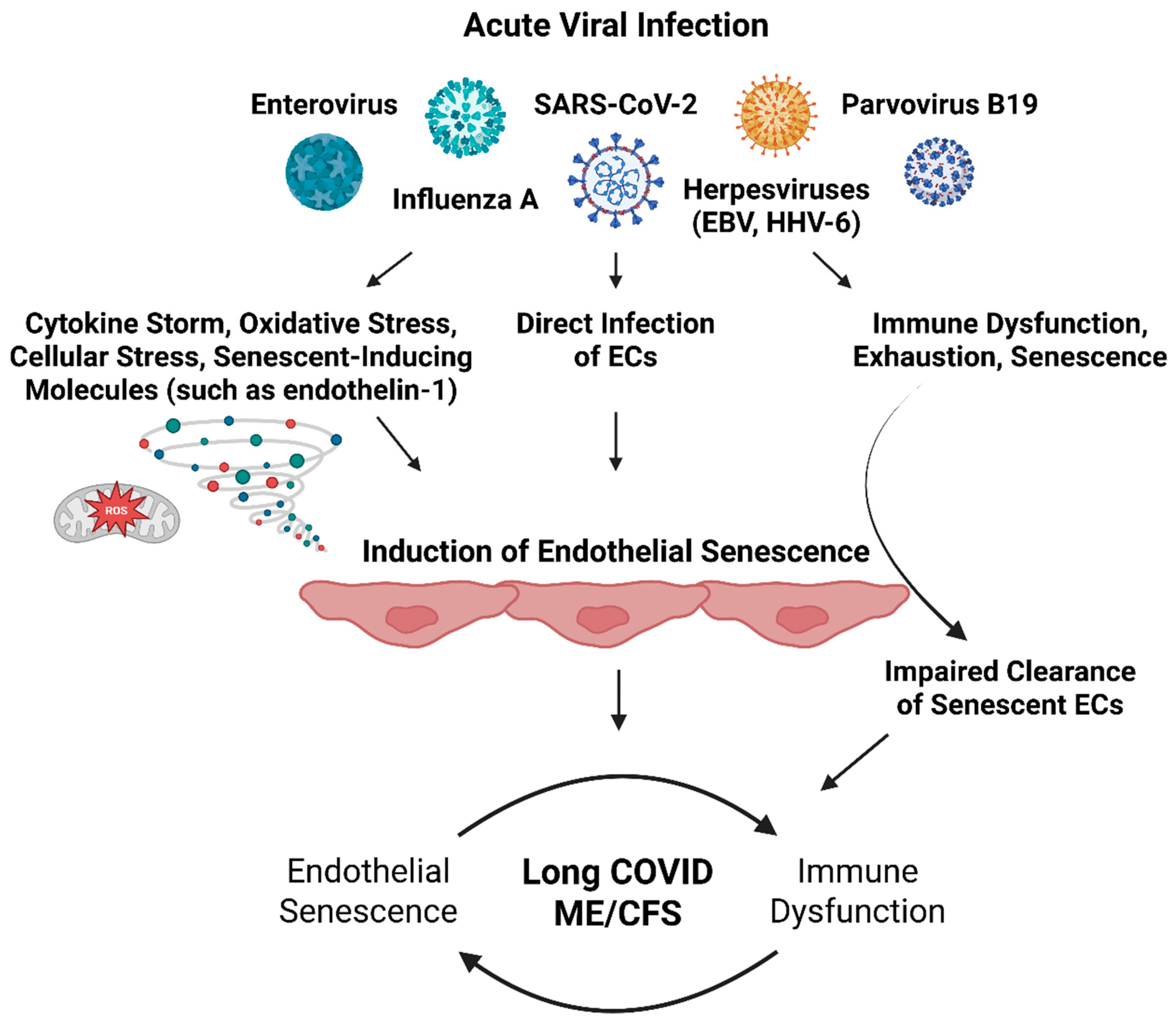

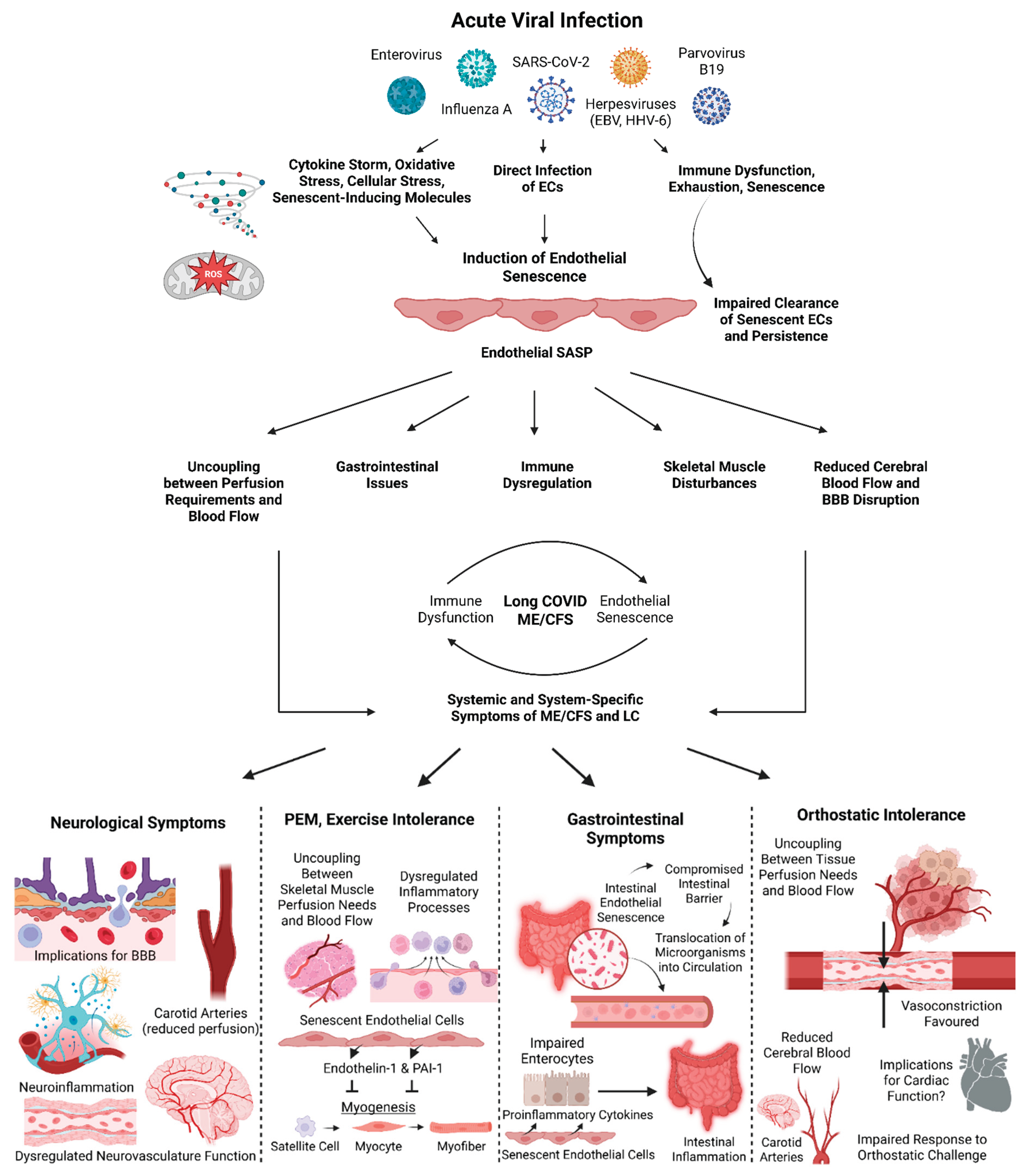

Endothelial Senescence as an Explanation for the Induction and Maintenance ME/CFS and Long COVID

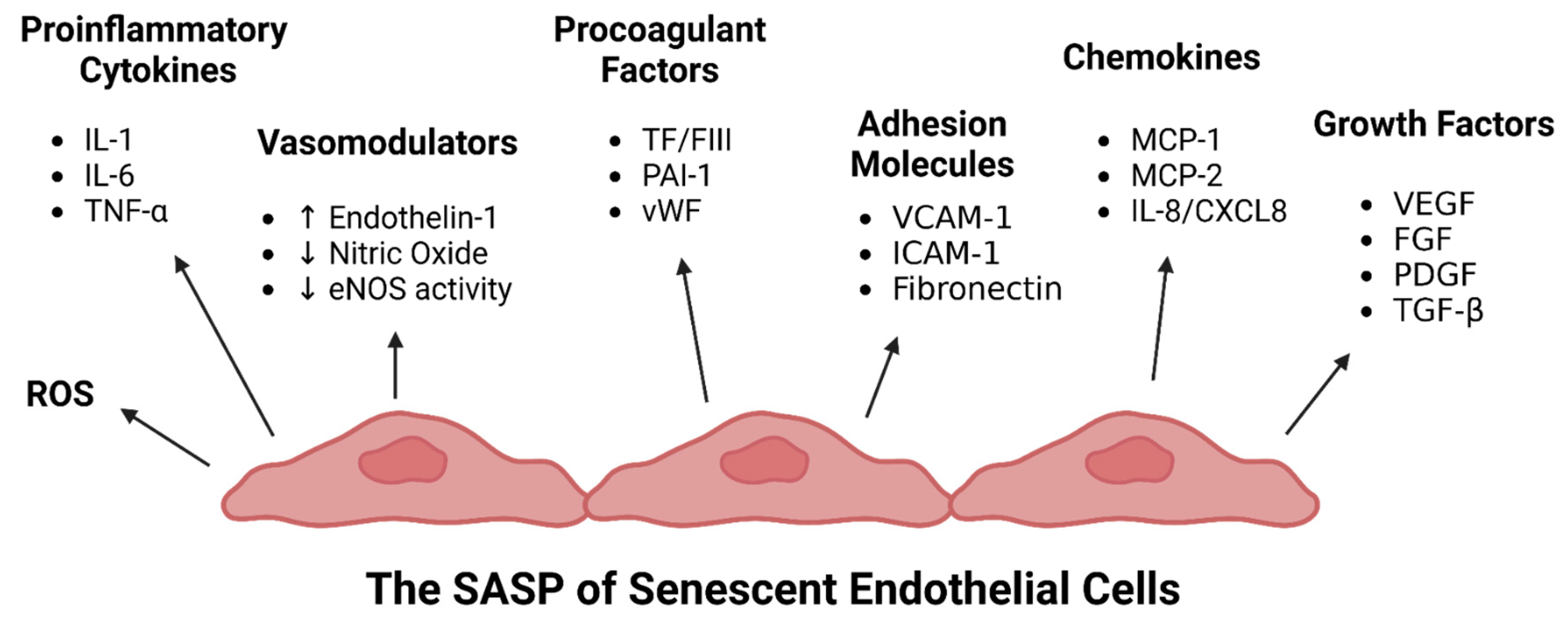

Endothelial Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) in ME/CFS and Long COVID

Senescent Endothelial Cells and Vascular Dysfunction

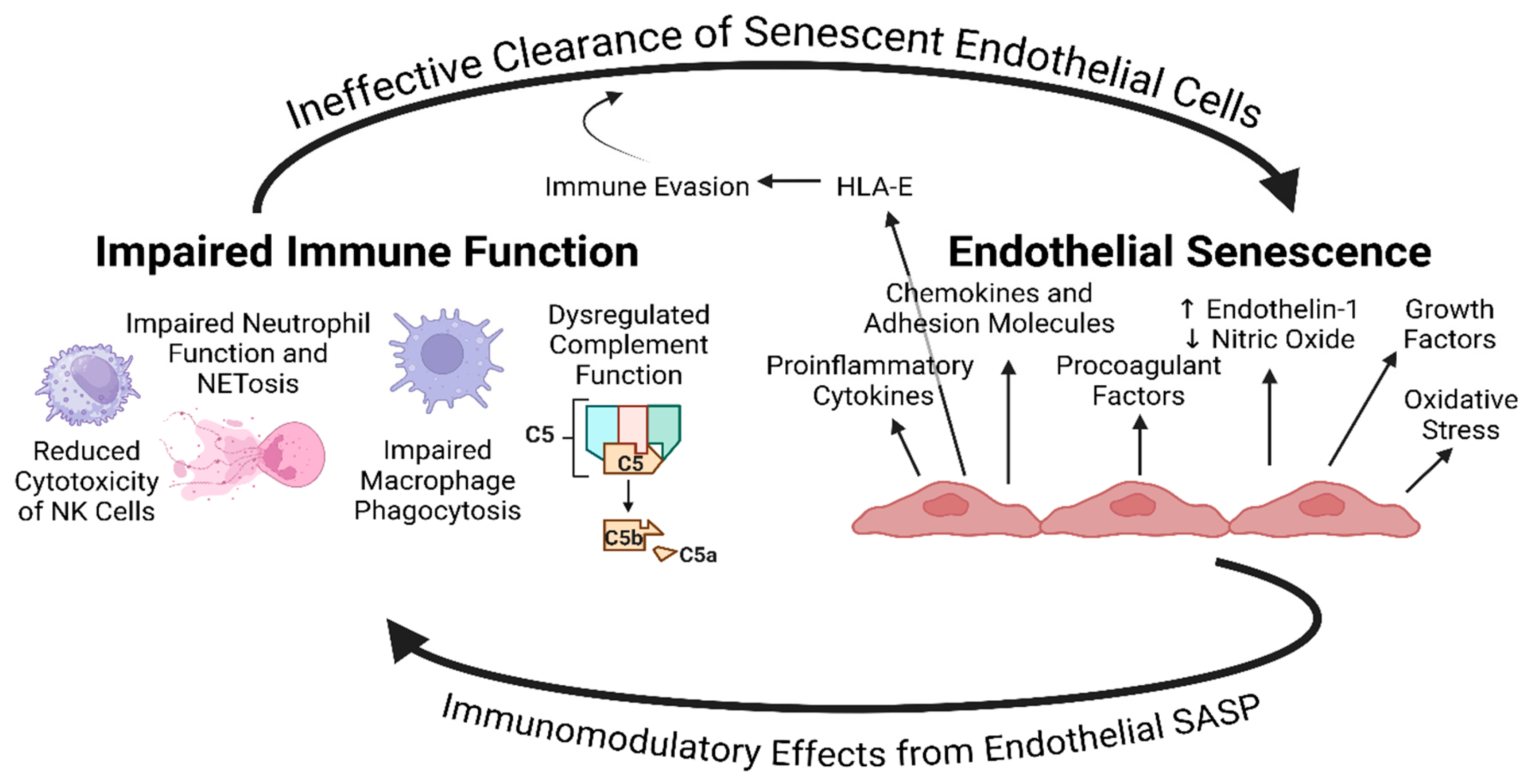

Proinflammatory Component of the Endothelial SASP and Immune Dysfunction, Exhaustion, & Senescence – A Possible Explanation for the Maintenance of Endothelial Senescence in ME/CFS and Long COVID

Senescence of Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells and Neurological Symptoms

Endothelial Senescence and Gastrointestinal Symptoms

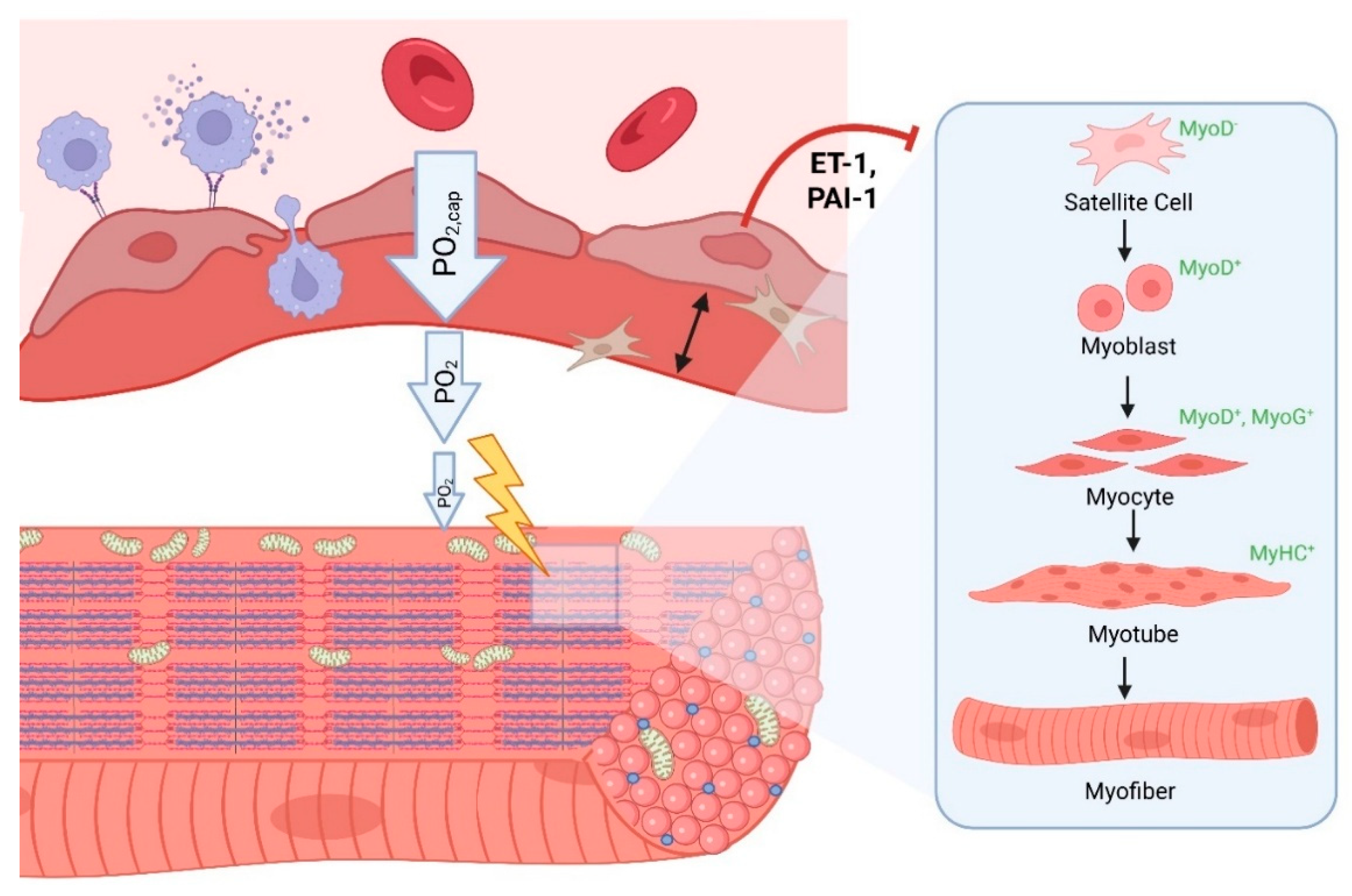

Senescence of Endothelial Cells and Post-Exertional Malaise

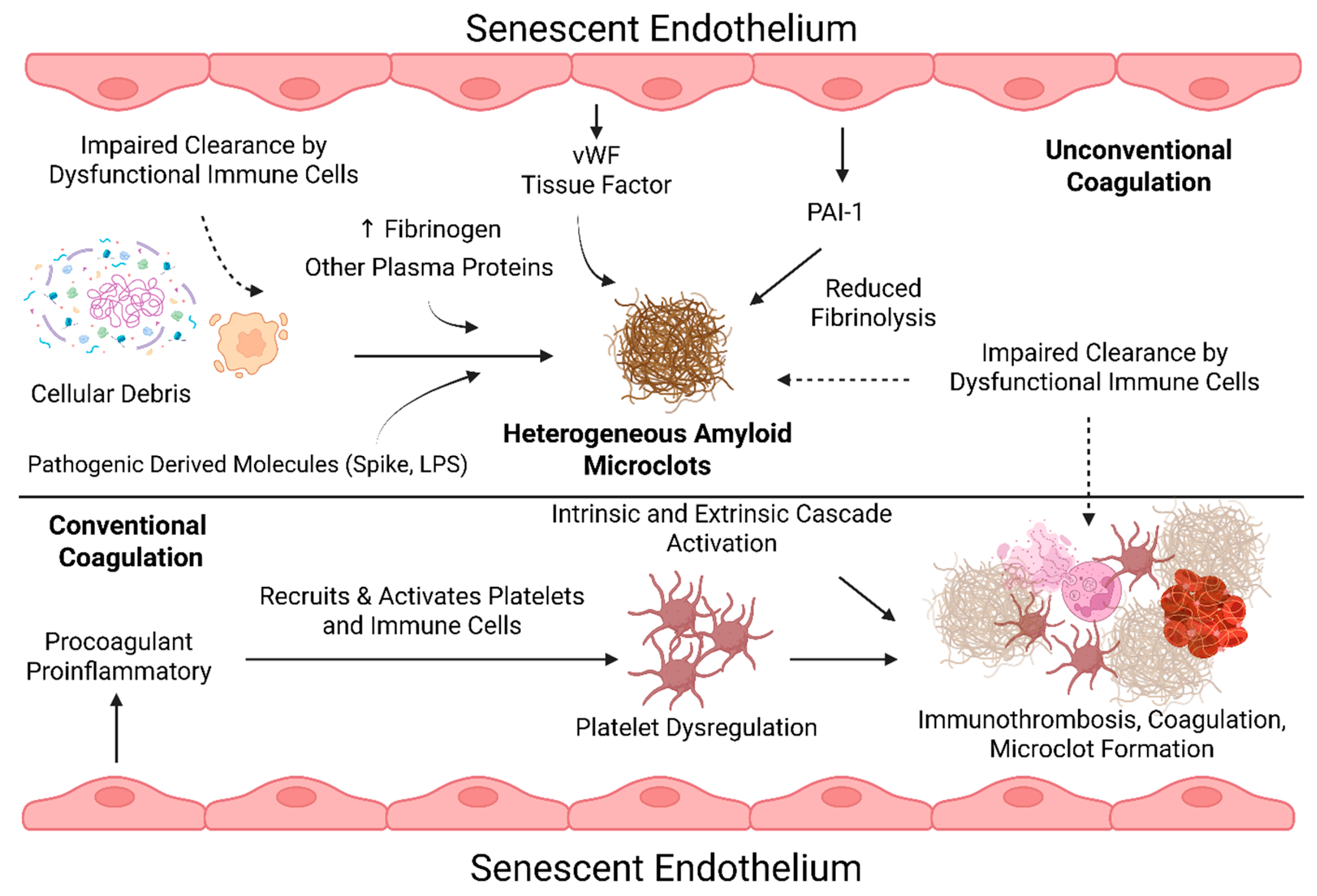

Procoagulant Factors of Senescent Endothelial Cells and Prolonged Coagulation Abnormalities

Senescent Endothelial Cells and the Relation to Herpesviruses

Future Considerations

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Komaroff, A.L. and W.I. Lipkin, ME/CFS and Long COVID share similar symptoms and biological abnormalities: road map to the literature. Frontiers in Medicine, 2023. 10.

- Al-Aly, Z. and E. Topol, Solving the puzzle of Long Covid. Science, 2024. 383(6685): p. 830-832.

- Mirin, A.A., M. E. Dimmock, and L.A. Jason, Updated ME/CFS prevalence estimates reflecting post-COVID increases and associated economic costs and funding implications. Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior, 2022. 10(2): p. 83-93.

- Reuken, P.A. , et al., Longterm course of neuropsychological symptoms and ME/CFS after SARS-CoV-2-infection: a prospective registry study. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 2024. 274(8): p. 1903-1910.

- Morita, S. , et al., Phase-dependent trends in the prevalence of myalgic encephalomyelitis / chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) related to long COVID: A criteria-based retrospective study in Japan. PLOS ONE, 2024. 19(12): p. e0315385.

- Ryabkova, V.A. , et al., Similar Patterns of Dysautonomia in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue and Post-COVID-19 Syndromes. Pathophysiology, 2024. 31(1): p. 1-17.

- Jamal, A. , et al., Post-SARS-CoV-2 Onset Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Symptoms in Two Cohort Studies of COVID-19 Recovery. medRxiv, 2024: p. 2024.11.08.24316976.

- Bonilla, H. , et al., Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is common in post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC): Results from a post-COVID-19 multidisciplinary clinic. Frontiers in Neurology, 2023. 14.

- Dehlia, A. and M.A. Guthridge, The persistence of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) after SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Infection, 2024. 89(6): p. 106297.

- Saury, J.-M. , The role of the hippocampus in the pathogenesis of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Medical Hypotheses, 2016. 86: p. 30-38.

- Tate, W. , et al., Molecular Mechanisms of Neuroinflammation in ME/CFS and Long COVID to Sustain Disease and Promote Relapses. Frontiers in Neurology, 2022. 13.

- Hayden, M.R. , Hypothesis: neuroglia activation due to increased peripheral and CNS proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines with neuroinflammation may result in long COVID. Neuroglia, 2021. 2(1): p. 7-35.

- Ahamed, J. and J. Laurence, Long COVID endotheliopathy: hypothesized mechanisms and potential therapeutic approaches. The Journal of clinical investigation, 2022. 132(15).

- Wirth, K.J. and M. Löhn, Microvascular Capillary and Precapillary Cardiovascular Disturbances Strongly Interact to Severely Affect Tissue Perfusion and Mitochondrial Function in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Evolving from the Post COVID-19 Syndrome. Medicina, 2024. 60(2): p. 194.

- Wirth, K.J. and M. Löhn, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) and Comorbidities: Linked by Vascular Pathomechanisms and Vasoactive Mediators? Medicina, 2023. 59(5): p. 978.

- Wirth, K. and C. Scheibenbogen, A Unifying Hypothesis of the Pathophysiology of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): Recognitions from the finding of autoantibodies against ß2-adrenergic receptors. Autoimmunity Reviews, 2020. 19(6): p. 102527.

- Kell, D.B. and E. Pretorius, The potential role of ischaemia–reperfusion injury in chronic, relapsing diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, Long COVID, and ME/CFS: evidence, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Biochemical Journal, 2022. 479(16): p. 1653-1708.

- Nunes, M. , et al., Data-independent LC-MS/MS analysis of ME/CFS plasma reveals a dysregulated coagulation system, endothelial dysfunction, downregulation of complement machinery. Cardiovascular Diabetology, 2024. 23(1): p. 254.

- Nunes, J.M. , et al., The Occurrence of Hyperactivated Platelets and Fibrinaloid Microclots in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Pharmaceuticals, 2022. 15(8): p. 931.

- Apostolou, E. and A. Rosén, Epigenetic reprograming in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A narrative of latent viruses. Journal of Internal Medicine, 2024. 296(1): p. 93-115.

- Buonsenso, D. et al. Long COVID: A proposed hypothesis-driven model of viral persistence for the pathophysiology of the syndrome. in Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 2022. OceanSide Publications.

- Proal, A.D. and M.B. VanElzakker, Long COVID or Post-acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): An Overview of Biological Factors That May Contribute to Persistent Symptoms. Front Microbiol, 2021. 12: p. 698169.

- Proal, A.D. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 reservoir in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Nature Immunology, 2023. 24(10): p. 1616-1627.

- Bansal, A.S. , et al., What causes ME/CFS: the role of the dysfunctional immune system and viral infections. Journal of Immunology and Allergy, 2022. 3(2): p. 1-15.

- Kell, D.B. and E. Pretorius, Are fibrinaloid microclots a cause of autoimmunity in Long Covid and other post-infection diseases? Biochem J, 2023. 480(15): p. 1217-1240.

- Stanculescu, D., L. Larsson, and J. Bergquist, Hypothesis: Mechanisms That Prevent Recovery in Prolonged ICU Patients Also Underlie Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Frontiers in Medicine, 2021. 8.

- Morris, G., G. Anderson, and M. Maes, Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Hypofunction in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) as a Consequence of Activated Immune-Inflammatory and Oxidative and Nitrosative Pathways. Molecular Neurobiology, 2017. 54(9): p. 6806-6819.

- Eaton-Fitch, N. , et al., Immune exhaustion in ME/CFS and long COVID. JCI Insight, 2024. 9(20).

- Saito, S. , et al., Diverse immunological dysregulation, chronic inflammation, and impaired erythropoiesis in long COVID patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Autoimmunity, 2024. 147: p. 103267.

- Pretorius, E. , et al., Prevalence of symptoms, comorbidities, fibrin amyloid microclots and platelet pathology in individuals with Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Cardiovascular Diabetology, 2022. 21(1): p. 148.

- Dalton, C.F. , et al., Increased fibrinaloid microclot counts in platelet-poor plasma are associated with Long COVID. medRxiv, 2024: p. 2024.04.04.24305318.

- Vu, L.T. , et al., Single-cell transcriptomics of the immune system in ME/CFS at baseline and following symptom provocation. Cell Reports Medicine, 2024. 5(1).

- Giloteaux, L. , et al., Dysregulation of extracellular vesicle protein cargo in female myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome cases and sedentary controls in response to maximal exercise. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 2024. 13(1): p. 12403.

- Aggarwal, A. , et al., Dysregulated platelet function in patients with postacute sequelae of COVID-19. Vascular Medicine, 2024. 29(2): p. 125-134.

- Pretorius, E., M. Nunes, and D. Kell, Flow Clotometry: Measuring Amyloid Microclots in ME/CFS, Long COVID, and Healthy Samples with Imaging Flow Cytometry. 2024.

- Liu, J. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 cell tropism and multiorgan infection. Cell Discovery, 2021. 7(1): p. 17.

- Ambrosino, P. , et al., Persistent Endothelial Dysfunction in Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome: A Case-Control Study. Biomedicines, 2021. 9(8): p. 957.

- Lambadiari, V. , et al., Association of COVID-19 with impaired endothelial glycocalyx, vascular function and myocardial deformation 4 months after infection. European Journal of Heart Failure, 2021. 23(11): p. 1916-1926.

- Fogarty, H. , et al., Persistent endotheliopathy in the pathogenesis of long COVID syndrome. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 2021. 19(10): p. 2546-2553.

- Haffke, M. , et al., Endothelial dysfunction and altered endothelial biomarkers in patients with post-COVID-19 syndrome and chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Journal of Translational Medicine, 2022. 20(1): p. 138.

- Oikonomou, E. , et al., Endothelial dysfunction in acute and long standing COVID−19: A prospective cohort study. Vascular Pharmacology, 2022. 144: p. 106975.

- Willems, L.H. , et al., Sustained inflammation, coagulation activation and elevated endothelin-1 levels without macrovascular dysfunction at 3 months after COVID-19. Thrombosis Research, 2022. 209: p. 106-114.

- Kuchler, T. , et al., Persistent endothelial dysfunction in post-COVID-19 syndrome and its associations with symptom severity and chronic inflammation. Angiogenesis, 2023. 26(4): p. 547-563.

- Vassiliou, A.G. , et al., Endotheliopathy in Acute COVID-19 and Long COVID. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023. 24(9): p. 8237.

- Alfaro, E. , et al., Endothelial dysfunction and persistent inflammation in severe post-COVID-19 patients: implications for gas exchange. BMC Medicine, 2024. 22(1): p. 242.

- Wu, X. , et al., Damage to endothelial barriers and its contribution to long COVID. Angiogenesis, 2024. 27(1): p. 5-22.

- Ståhlberg, M. , et al., Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome: Prevalence of Peripheral Microvascular Endothelial Dysfunction and Associations with NT-ProBNP Dynamics. The American Journal of Medicine, 2024.

- Muys, M. , et al., Exploring Hypercoagulability in Post-COVID Syndrome (PCS): An Attempt at Unraveling the Endothelial Dysfunction. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2025. 14(3): p. 789.

- Smadja, D.M. , et al., Circulating endothelial cells: a key biomarker of persistent fatigue after hospitalization for COVID-19. Angiogenesis, 2024. 28(1): p. 8.

- Thomas, D. , et al., CCL2-mediated endothelial injury drives cardiac dysfunction in long COVID. Nature Cardiovascular Research, 2024. 3(10): p. 1249-1265.

- Xu, S.-w., I. Ilyas, and J.-p. Weng, Endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19: an overview of evidence, biomarkers, mechanisms and potential therapies. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, 2023. 44(4): p. 695-709.

- Perico, L., A. Benigni, and G. Remuzzi, SARS-CoV-2 and the spike protein in endotheliopathy. Trends Microbiol, 2024. 32(1): p. 53-67.

- Scherbakov, N. , et al., Peripheral endothelial dysfunction in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. ESC Heart Failure, 2020. 7(3): p. 1064-1071.

- Sørland, K. , et al., Reduced Endothelial Function in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome-Results From Open-Label Cyclophosphamide Intervention Study. Front Med (Lausanne), 2021. 8: p. 642710.

- Blauensteiner, J. , et al., Altered endothelial dysfunction-related miRs in plasma from ME/CFS patients. Scientific Reports, 2021. 11(1): p. 10604.

- Sandvik, M.K. , et al., Endothelial dysfunction in ME/CFS patients. PLOS ONE, 2023. 18(2): p. e0280942.

- McLaughlin, M. , et al., People with Long COVID and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Exhibit Similarly Impaired Vascular Function. The American Journal of Medicine, 2023.

- Cambras, T. , et al., Skin Temperature Circadian Rhythms and Dysautonomia in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: The Role of Endothelin-1 in the Vascular Tone Dysregulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023. 24(5): p. 4835.

- Domingo, J.C. , et al., Association of circulating biomarkers with illness severity measures differentiates myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and post-COVID-19 condition: a prospective pilot cohort study. Journal of Translational Medicine, 2024. 22(1): p. 343.

- Renz-Polster, H. , et al., The Pathobiology of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: The Case for Neuroglial Failure. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 2022. 16.

- Lubell, J. , Letter: Could endothelial dysfunction and vascular damage contribute to pain, inflammation and post-exertional malaise in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)? Journal of Translational Medicine, 2022. 20(1): p. 40.

- Sfera, A. , et al., Endothelial Senescence and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, a COVID-19 Based Hypothesis. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 2021. 15.

- Nunes, J.M., D. B. Kell, and E. Pretorius, Herpesvirus Infection of Endothelial Cells as a Systemic Pathological Axis in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Viruses, 2024. 16(4): p. 572.

- de Rooij, L.P.M.H., L. M. Becker, and P. Carmeliet, A Role for the Vascular Endothelium in Post–Acute COVID-19? Circulation, 2022. 145(20): p. 1503-1505.

- Kruger, A. , et al., Vascular Pathogenesis in Acute and Long COVID: Current Insights and Therapeutic Outlook. Semin Thromb Hemost, 2024(EFirst).

- van Campen, C.M.C. , et al., The Cardiac Output–Cerebral Blood Flow Relationship Is Abnormal in Most Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients with a Normal Heart Rate and Blood Pressure Response During a Tilt Test. Healthcare, 2024. 12(24): p. 2566.

- van Campen, C.M.C. , et al., Cerebral blood flow is reduced in ME/CFS during head-up tilt testing even in the absence of hypotension or tachycardia: A quantitative, controlled study using Doppler echography. Clinical Neurophysiology Practice, 2020. 5: p. 50-58.

- van Campen, C.M.C., P. C. Rowe, and F.C. Visser, Orthostatic Symptoms and Reductions in Cerebral Blood Flow in Long-Haul COVID-19 Patients: Similarities with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Medicina, 2022. 58(1): p. 28.

- Thapaliya, K. , et al., Brainstem volume changes in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and long COVID patients. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2023. 17.

- Chien, C. , et al., Altered brain perfusion and oxygen levels relate to sleepiness and attention in post-COVID syndrome. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology, 2024. 11(8): p. 2016-2029.

- Lee, J.-S., W. Sato, and C.-G. Son, Brain-regional characteristics and neuroinflammation in ME/CFS patients from neuroimaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmunity Reviews, 2024. 23(2): p. 103484.

- Li, X., P. Julin, and T.-Q. Li, Limbic Perfusion Is Reduced in Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Tomography, 2021. 7(4): p. 675-687.

- Pizzuto, D.A. , et al., Lung perfusion assessment in children with long-COVID: A pilot study. Pediatric Pulmonology, 2023. 58(7): p. 2059-2067.

- van Deursen, J.M. , The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature, 2014. 509(7501): p. 439-446.

- Harley, C.B., A. B. Futcher, and C.W. Greider, Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature, 1990. 345(6274): p. 458-460.

- von Zglinicki, T. , Role of oxidative stress in telomere length regulation and replicative senescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2000. 908: p. 99-110.

- Narita, M. , et al., Spatial coupling of mTOR and autophagy augments secretory phenotypes. Science, 2011. 332(6032): p. 966-70.

- Campisi, J. , Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell, 2005. 120(4): p. 513-22.

- Passos, J.F. , et al., Feedback between p21 and reactive oxygen production is necessary for cell senescence. Mol Syst Biol, 2010. 6: p. 347.

- Stein, G.H. , et al., Differential roles for cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p16 in the mechanisms of senescence and differentiation in human fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol, 1999. 19(3): p. 2109-17.

- Rodier, F. , et al., DNA-SCARS: distinct nuclear structures that sustain damage-induced senescence growth arrest and inflammatory cytokine secretion. Journal of Cell Science, 2011. 124(1): p. 68-81.

- Narita, M. , et al., Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell, 2003. 113(6): p. 703-16.

- Ivanov, A. , et al., Lysosome-mediated processing of chromatin in senescence. J Cell Biol, 2013. 202(1): p. 129-43.

- Kirkland, J.L. and T. Tchkonia, Senolytic drugs: from discovery to translation. J Intern Med, 2020. 288(5): p. 518-536.

- Miwa, S. , et al., Mitochondrial dysfunction in cell senescence and aging. J Clin Invest, 2022. 132(13).

- Robbins, E., E. M. Levine, and H. Eagle, Morphologic changes accompanying senescence of cultured human diploid cells. J Exp Med, 1970. 131(6): p. 1211-22.

- Correia-Melo, C. , et al., Mitochondria are required for pro-ageing features of the senescent phenotype. Embo j, 2016. 35(7): p. 724-42.

- Coppé, J.P. , et al., Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol, 2008. 6(12): p. 2853-68.

- Dimri, G.P. , et al., A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1995. 92(20): p. 9363-7.

- Kurz, D.J. , et al., Senescence-associated (beta)-galactosidase reflects an increase in lysosomal mass during replicative ageing of human endothelial cells. J Cell Sci, 2000. 113 ( Pt 20): p. 3613-22.

- Oguma, Y. , et al., Meta-analysis of senescent cell secretomes to identify common and specific features of the different senescent phenotypes: a tool for developing new senotherapeutics. Cell Communication and Signaling, 2023. 21(1): p. 262.

- Lagnado, A. , et al., Neutrophils induce paracrine telomere dysfunction and senescence in ROS-dependent manner. Embo j, 2021. 40(9): p. e106048.

- Ovadya, Y. , et al., Impaired immune surveillance accelerates accumulation of senescent cells and aging. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 5435.

- Pereira, B.I. , et al., Senescent cells evade immune clearance via HLA-E-mediated NK and CD8+ T cell inhibition. Nature Communications, 2019. 10(1): p. 2387.

- Nelson, G. , et al., A senescent cell bystander effect: senescence-induced senescence. Aging Cell, 2012. 11(2): p. 345-9.

- D’Agnillo, F. , et al., Lung epithelial and endothelial damage, loss of tissue repair, inhibition of fibrinolysis, and cellular senescence in fatal COVID-19. Science Translational Medicine, 2021. 13(620): p. eabj7790.

- Urata, R. , et al., Senescent endothelial cells are predisposed to SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent endothelial dysfunction. Scientific Reports, 2022. 12(1): p. 11855.

- Gioia, U. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 infection induces DNA damage, through CHK1 degradation and impaired 53BP1 recruitment, and cellular senescence. Nat Cell Biol, 2023. 25(4): p. 550-564.

- Lee, S. , et al., Virus-induced senescence is a driver and therapeutic target in COVID-19. Nature, 2021. 599(7884): p. 283-289.

- Camell, C.D. , et al., Senolytics reduce coronavirus-related mortality in old mice. Science, 2021. 373(6552).

- Pastor-Fernández, A. , et al., Treatment with the senolytics dasatinib/quercetin reduces SARS-CoV-2-related mortality in mice. Aging Cell, 2023. 22(3): p. e13771.

- Potgieter, M. , et al., The dormant blood microbiome in chronic, inflammatory diseases. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2015. 39(4): p. 567-91.

- Wang, X. and B. He, Endothelial dysfunction: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. MedComm, 2024. 5(8): p. e651.

- Bordoni, V. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 infection of airway epithelium triggers pulmonary endothelial cell activation and senescence associated with type I IFN production. Cells, 2022. 11(18): p. 2912.

- Meyer, K. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Induces Paracrine Senescence and Leukocyte Adhesion in Endothelial Cells. Journal of Virology, 2021. 95(17): p. 10.1128/jvi.00794-21.

- Lipskaia, L. , et al., Evidence that SARS-CoV-2 induces lung cell senescence: potential impact on COVID-19 lung disease. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology, 2022. 66(1): p. 107-111.

- Schulz, L. , et al., Influenza Virus-Induced Paracrine Cellular Senescence of the Lung Contributes to Enhanced Viral Load. Aging Dis, 2023. 14(4): p. 1331-1348.

- Yan, Y. , et al., NS1 of H7N9 Influenza A Virus Induces NO-Mediated Cellular Senescence in Neuro2a Cells. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry, 2017. 43(4): p. 1369-1380.

- Arvia, R. , et al., Parvovirus B19 induces cellular senescence in human dermal fibroblasts: putative role in systemic sclerosis–associated fibrosis. Rheumatology, 2021. 61(9): p. 3864-3874.

- Lekva, T. , et al., Markers of cellular senescence is associated with persistent pulmonary pathology after COVID-19 infection. Infect Dis (Lond), 2022. 54(12): p. 918-923.

- Lynch, S.M. , et al., Role of Senescence and Aging in SARS-CoV-2 Infection and COVID-19 Disease. Cells, 2021. 10(12): p. 3367.

- Berentschot, J.C. , et al., Immunological profiling in long COVID: overall low grade inflammation and T-lymphocyte senescence and increased monocyte activation correlating with increasing fatigue severity. Frontiers in Immunology, 2023. 14.

- Lord, J.M. , et al., Accelerated immune ageing is associated with COVID-19 disease severity. Immunity & Ageing, 2024. 21(1): p. 6.

- Kempuraj, D. , et al., COVID-19 and Long COVID: Disruption of the Neurovascular Unit, Blood-Brain Barrier, and Tight Junctions. The Neuroscientist, 2024. 30(4): p. 421-439.

- Otifi, H.M. and B.K. Adiga, Endothelial dysfunction in Covid-19 infection. The American journal of the medical sciences, 2022. 363(4): p. 281-287.

- Mroueh, A. , et al., COVID-19 promotes endothelial dysfunction and thrombogenicity: role of proinflammatory cytokines/SGLT2 prooxidant pathway. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 2024. 22(1): p. 286-299.

- Liu, F. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 infects endothelial cells in vivo and in vitro. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 2021. 11: p. 701278.

- Yang, R.-C. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 productively infects human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Journal of neuroinflammation, 2022. 19(1): p. 149.

- Caccuri, F. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 Infection Remodels the Phenotype and Promotes Angiogenesis of Primary Human Lung Endothelial Cells. Microorganisms, 2021. 9(7): p. 1438.

- Yamada, S. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 causes dysfunction in human iPSC-derived brain microvascular endothelial cells potentially by modulating the Wnt signaling pathway. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS, 2024. 21(1): p. 32.

- Hatch, C.J. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 infection of endothelial cells, dependent on flow-induced ACE2 expression, drives hypercytokinemia in a vascularized microphysiological system. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 2024. 11.

- Meyer, K. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 spike protein expressing epithelial cells promotes senescence associated secretory phenotype in endothelial cells and increased inflammatory response. bioRxiv, 2021: p. 2021.04.16.440215.

- Kedor, C. , et al., Chronic COVID-19 Syndrome and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) following the first pandemic wave in Germany – a first analysis of a prospective observational study. medRxiv, 2021: p. 2021.02.06.21249256.

- Vernon, S.D. , et al., Incidence and Prevalence of Post-COVID-19 Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: A Report from the Observational RECOVER-Adult Study. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2025.

- Farina, A. , et al., Innate Immune Modulation Induced by EBV Lytic Infection Promotes Endothelial Cell Inflammation and Vascular Injury in Scleroderma. Front Immunol, 2021. 12: p. 651013.

- Indari, O. , et al., Early biomolecular changes in brain microvascular endothelial cells under Epstein–Barr virus influence: a Raman microspectroscopic investigation. Integrative Biology, 2022. 14(4): p. 89-97.

- Jones, K. , et al., Infection of human endothelial cells with Epstein-Barr virus. J Exp Med, 1995. 182(5): p. 1213-21.

- Casiraghi, C., K. Dorovini-Zis, and M.S. Horwitz, Epstein-Barr virus infection of human brain microvessel endothelial cells: A novel role in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 2011. 230(1): p. 173-177.

- Pricoco, R. , et al., One-year follow-up of young people with ME/CFS following infectious mononucleosis by Epstein-Barr virus. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 2024. 11.

- Kasimir, F. , et al., Tissue specific signature of HHV-6 infection in ME/CFS. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 2022. 9: p. 1044964.

- Ruiz-Pablos, M. , et al., Epstein-Barr virus and the origin of myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome. Frontiers in immunology, 2021. 12: p. 656797.

- Shikova, E. , et al., Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and human herpesvirus-6 infections in patients with myalgic еncephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of medical virology, 2020. 92(12): p. 3682-3688.

- Takatsuka, H. , et al., Endothelial damage caused by cytomegalovirus and human herpesvirus-6. Bone marrow transplantation, 2003. 31(6): p. 475-479.

- Caruso, A. , et al., HHV-6 infects human aortic and heart microvascular endothelial cells, increasing their ability to secrete proinflammatory chemokines. J Med Virol, 2002. 67(4): p. 528-33.

- Caruso, A. , et al., Human herpesvirus-6 modulates RANTES production in primary human endothelial cell cultures. J Med Virol, 2003. 70(3): p. 451-8.

- Wu, C.A. and J.D. Shanley, Chronic infection of human umbilical vein endothelial cells by human herpesvirus-6. J Gen Virol, 1998. 79 ( Pt 5): p. 1247-56.

- Rotola, A. , et al., Human herpesvirus 6 infects and replicates in aortic endothelium. J Clin Microbiol, 2000. 38(8): p. 3135-6.

- Mozhgani, S.-H. , et al., Human Herpesvirus 6 Infection and Risk of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Intervirology, 2021. 65(1): p. 49-57.

- Zeng, H. , et al., A(H7N9) virus results in early induction of proinflammatory cytokine responses in both human lung epithelial and endothelial cells and shows increased human adaptation compared with avian H5N1 virus. J Virol, 2015. 89(8): p. 4655-67.

- Bauer, L. , et al., The pro-inflammatory response to influenza A virus infection is fueled by endothelial cells. Life Science Alliance, 2023. 6(7): p. e202201837.

- Marchenko, V. , et al., Influenza A Virus Causes Histopathological Changes and Impairment in Functional Activity of Blood Vessels in Different Vascular Beds. Viruses, 2022. 14(2): p. 396.

- Marchesi, S. , et al., Acute inflammatory state during influenza infection and endothelial function. Atherosclerosis, 2005. 178(2): p. 345-350.

- Marchenko, V.A. and I.N. Zhilinskaya, Endothelial activation and dysfunction caused by influenza A virus (Alphainfluenzavirus influenzae). Problems of Virology, 2024. 69(6): p. 465-478.

- Hiyoshi, M. , et al., Influenza A virus infection of vascular endothelial cells induces GSK-3β-mediated β-catenin degradation in adherens junctions, with a resultant increase in membrane permeability. Archives of Virology, 2015. 160(1): p. 225-234.

- Armstrong, S.M. , et al., Influenza infects lung microvascular endothelium leading to microvascular leak: role of apoptosis and claudin-5. PLoS One, 2012. 7(10): p. e47323.

- Suo, J. , et al., Influenza virus aggravates the ox-LDL-induced apoptosis of human endothelial cells via promoting p53 signaling. Journal of Medical Virology, 2015. 87(7): p. 1113-1123.

- Xia, B. , et al., FBXL19 in endothelial cells protects the heart from influenza A infection by enhancing antiviral immunity and reducing cellular senescence programs. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 2024. 327(4): p. H937-H946.

- Magnus, P. , et al., Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) is associated with pandemic influenza infection, but not with an adjuvanted pandemic influenza vaccine. Vaccine, 2015. 33(46): p. 6173-6177.

- Chang, H. , et al., Increased risk of chronic fatigue syndrome following infection: a 17-year population-based cohort study. Journal of Translational Medicine, 2023. 21(1): p. 804.

- Liang, C.-C. , et al., Human endothelial cell activation and apoptosis induced by enterovirus 71 infection. Journal of Medical Virology, 2004. 74(4): p. 597-603.

- Luo, W. , et al., Proteomic Analysis of Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells Reveals Differential Protein Expression in Response to Enterovirus 71 Infection. BioMed Research International, 2015. 2015(1): p. 864169.

- Ji, W. , et al., The Disruption of the Endothelial Barrier Contributes to Acute Lung Injury Induced by Coxsackievirus A2 Infection in Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021. 22(18): p. 9895.

- Han, S. , et al., Emerging concerns of blood-brain barrier dysfunction caused by neurotropic enteroviral infections. Virology, 2024. 591: p. 109989.

- Zhu, Y. , et al., Enterovirus 71 enters human brain microvascular endothelial cells through an ARF6-mediated endocytic pathway. Journal of Medical Virology, 2023. 95(7): p. e28915.

- Saijets, S. , et al., Enterovirus infection and activation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Journal of medical virology, 2003. 70(3): p. 430-439.

- Schmidt-Lucke, C. , et al., Interferon Beta Modulates Endothelial Damage in Patients with Cardiac Persistence of Human Parvovirus B19 Infection. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2010. 201(6): p. 936-945.

- Wen, J. and C. Huang, Coxsackieviruses B3 infection of myocardial microvascular endothelial cells activates fractalkine via the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep, 2017. 16(5): p. 7548-7552.

- O'Neal, A.J. and M.R. Hanson, The Enterovirus Theory of Disease Etiology in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Critical Review. Front Med (Lausanne), 2021. 8: p. 688486.

- Chia, J.K.S. and A.Y. Chia, Chronic fatigue syndrome is associated with chronic enterovirus infection of the stomach. Journal of Clinical Pathology, 2008. 61(1): p. 43-48.

- Chia, J. , et al., Acute enterovirus infection followed by myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and viral persistence. J Clin Pathol, 2010. 63(2): p. 165-8.

- Tschöpe, C. , et al., High Prevalence of Cardiac Parvovirus B19 Infection in Patients With Isolated Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction. Circulation, 2005. 111(7): p. 879-886.

- Bachelier, K. , et al., Parvovirus B19-induced vascular damage in the heart is associated with elevated circulating endothelial microparticles. PLoS One, 2017. 12(5): p. e0176311.

- Rinkūnaitė, I. , et al., The Effect of a Unique Region of Parvovirus B19 Capsid Protein VP1 on Endothelial Cells. Biomolecules, 2021. 11(4): p. 606.

- von Kietzell, K. , et al., Antibody-mediated enhancement of parvovirus B19 uptake into endothelial cells mediated by a receptor for complement factor C1q. Journal of virology, 2014. 88(14): p. 8102-8115.

- Pasquinelli, G. , et al., Placental endothelial cells can be productively infected by Parvovirus B19. Journal of Clinical Virology, 2009. 44(1): p. 33-38.

- Seishima, M. , et al., Chronic fatigue syndrome after human parvovirus B19 infection without persistent viremia. Dermatology, 2008. 216(4): p. 341-6.

- Kerr, J.R. and D.L. Mattey, Preexisting psychological stress predicts acute and chronic fatigue and arthritis following symptomatic parvovirus B19 infection. Clin Infect Dis, 2008. 46(9): p. e83-7.

- Rasa-Dzelzkaleja, S. , et al., The persistent viral infections in the development and severity of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Translational Medicine, 2023. 21(1): p. 33.

- Rasa-Dzelzkalēja, S. , et al., Association of Human Parvovirus B19 Infection with Development and Clinical Course of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Proceedings of the Latvian Academy of Sciences. Section B. Natural, Exact, and Applied Sciences., 2019. 73(5): p. 411-418.

- Abdul, Y. , et al., Endothelin A receptors contribute to senescence of brain microvascular endothelial cells. Can J Physiol Pharmacol, 2022. 100(12): p. 1087-1096.

- El Habhab, A. , et al., Significance of neutrophil microparticles in ischaemia-reperfusion: Pro-inflammatory effectors of endothelial senescence and vascular dysfunction. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 2020. 24(13): p. 7266-7281.

- Park, S.-H. , et al., Angiotensin II-induced upregulation of SGLT1 and 2 contributes to human microparticle-stimulated endothelial senescence and dysfunction: protective effect of gliflozins. Cardiovascular diabetology, 2021. 20: p. 1-17.

- Zhang, D. , et al., Homocysteine accelerates senescence of endothelial cells via DNA hypomethylation of human telomerase reverse transcriptase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2015. 35(1): p. 71-8.

- Shang, D., H. Liu, and Z. Tu, Pro-inflammatory cytokines mediating senescence of vascular endothelial cells in atherosclerosis. Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology, 2023. 37(5): p. 928-936.

- Sfera, A. , et al., Intoxication With Endogenous Angiotensin II: A COVID-19 Hypothesis. Front Immunol, 2020. 11: p. 1472.

- Bloom, S.I. , et al., Mechanisms and consequences of endothelial cell senescence. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2023. 20(1): p. 38-51.

- Wang, P. , et al., Endothelial Senescence: From Macro- to Micro-Vasculature and Its Implications on Cardiovascular Health. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024. 25(4): p. 1978.

- Sabbatinelli, J. , et al., Where Metabolism Meets Senescence: Focus on Endothelial Cells. Frontiers in Physiology, 2019. 10.

- Giuliani, A. , et al., Senescent Endothelial Cells Sustain Their Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) through Enhanced Fatty Acid Oxidation. Antioxidants, 2023. 12(11): p. 1956.

- Hasan, H. , et al., Thrombin Induces Angiotensin II-Mediated Senescence in Atrial Endothelial Cells: Impact on Pro-Remodeling Patterns. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2019. 8(10): p. 1570.

- Cohen, C. , et al., Glomerular endothelial cell senescence drives age-related kidney disease through PAI-1. EMBO Molecular Medicine, 2021. 13(11): p. e14146.

- Grillari, J. , et al., Subtractive hybridization of mRNA from early passage and senescent endothelial cells. Exp Gerontol, 2000. 35(2): p. 187-97.

- Alavi, P. , et al., Aging Is Associated With Organ-Specific Alterations in the Level and Expression Pattern of von Willebrand Factor. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 2023. 43(11): p. 2183-2196.

- Han, Y. and S.Y. Kim, Endothelial senescence in vascular diseases: current understanding and future opportunities in senotherapeutics. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 2023. 55(1): p. 1-12.

- Matsushita, H. , et al., eNOS Activity Is Reduced in Senescent Human Endothelial Cells. Circulation Research, 2001. 89(9): p. 793-798.

- Minamino, T. , et al., Endothelial cell senescence in human atherosclerosis: role of telomere in endothelial dysfunction. Circulation, 2002. 105(13): p. 1541-4.

- Demaria, M. , et al., An essential role for senescent cells in optimal wound healing through secretion of PDGF-AA. Dev Cell, 2014. 31(6): p. 722-33.

- Prattichizzo, F. , et al., Anti-TNF-α treatment modulates SASP and SASP-related microRNAs in endothelial cells and in circulating angiogenic cells. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(11): p. 11945-58.

- Khavinson, V. , et al., Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype of Cardiovascular System Cells and Inflammaging: Perspectives of Peptide Regulation. Cells, 2023. 12(1): p. 106.

- Liao, Y.-L. , et al., Senescent endothelial cells: a potential target for diabetic retinopathy. Angiogenesis, 2024. 27(4): p. 663-679.

- Shosha, E. , et al., Mechanisms of Diabetes-Induced Endothelial Cell Senescence: Role of Arginase 1. Int J Mol Sci, 2018. 19(4).

- Zerón-Rugerio, M.F. , et al., Sleep and circadian rhythm alterations in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and post-COVID fatigue syndrome and its association with cardiovascular risk factors: A prospective cohort study. Chronobiology International, 2024. 41(8): p. 1104-1115.

- Svitailo, V.S. and M.D. Chemych, Indicators of blood coagulation function, concentration of endothelin-1 and Long-COVID. 2024.

- Philippe, A. , et al., VEGF-A plasma levels are associated with impaired DLCO and radiological sequelae in long COVID patients. Angiogenesis, 2024. 27(1): p. 51-66.

- Kavyani, B. , et al., Dysregulation of the Kynurenine Pathway, Cytokine Expression Pattern, and Proteomics Profile Link to Symptomology in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Molecular Neurobiology, 2024. 61(7): p. 3771-3787.

- Abraham, G.R. , et al., Endothelin-1 is increased in the plasma of patients hospitalised with Covid-19. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 2022. 167: p. 92-96.

- Turgunova, L. , et al., The Association of Endothelin-1 with Early and Long-Term Mortality in COVID-19. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 2023. 13(11): p. 1558.

- Farhangrazi, Z.S. and S.M. Moghimi, Elevated circulating endothelin-1 as a potential biomarker for high-risk COVID-19 severity. Precis Nanomed, 2020. 3: p. 622-628.

- Yokoi, T. , et al., Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 mediates cellular senescence induced by high glucose in endothelial cells. Diabetes, 2006. 55(6): p. 1660-5.

- Wirth, K.J., C. Scheibenbogen, and F. Paul, An attempt to explain the neurological symptoms of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Journal of Translational Medicine, 2021. 19(1): p. 471.

- Wang, Y. , et al., Cerebral blood flow alterations and host genetic association in individuals with long COVID: A transcriptomic-neuroimaging study. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 2025. 45(3): p. 431-442.

- Kell, D.B., G. J. Laubscher, and E. Pretorius, A central role for amyloid fibrin microclots in long COVID/PASC: origins and therapeutic implications. Biochem J, 2022. 479(4): p. 537-559.

- Kim, S.Y. and J. Cheon, Senescence-associated microvascular endothelial dysfunction: A focus on the blood-brain and blood-retinal barriers. Ageing Research Reviews, 2024. 100: p. 102446.

- Chala, N. , et al., Mechanical Fingerprint of Senescence in Endothelial Cells. Nano Lett, 2021. 21(12): p. 4911-4920.

- Stamatovic, S.M. , et al., Decline in Sirtuin-1 expression and activity plays a critical role in blood-brain barrier permeability in aging. Neurobiol Dis, 2019. 126: p. 105-116.

- Yamazaki, Y. , et al., Vascular Cell Senescence Contributes to Blood–Brain Barrier Breakdown. Stroke, 2016. 47(4): p. 1068-1077.

- Najari Beidokhti, M. , et al., Lung endothelial cell senescence impairs barrier function and promotes neutrophil adhesion and migration. GeroScience, 2025.

- Donato, A.J. , et al., Cellular and molecular biology of aging endothelial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol, 2015. 89(Pt B): p. 122-35.

- van Campen, C.M.C., P. C. Rowe, and F.C. Visser, Cerebral Blood Flow Is Reduced in Severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients During Mild Orthostatic Stress Testing: An Exploratory Study at 20 Degrees of Head-Up Tilt Testing. Healthcare, 2020. 8(2): p. 169.

- Nunes, J.M., D. B. Kell, and E. Pretorius, Cardiovascular and haematological pathology in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): A role for viruses. Blood Rev, 2023. 60: p. 101075.

- McMaster, M.W. , et al., The Impact of Long COVID-19 on the Cardiovascular System. Cardiology in Review, 2024.

- Hira, R. , et al., Attenuated cardiac autonomic function in patients with long-COVID with impaired orthostatic hemodynamics. Clinical Autonomic Research, 2025.

- Ohno, Y. , et al., The diagnostic value of endothelial function as a potential sensor of fatigue in health. Vascular Health and Risk Management, 2010. 6(null): p. 135-144.

- Honda, S. , et al., Cellular senescence promotes endothelial activation through epigenetic alteration, and consequently accelerates atherosclerosis. Scientific Reports, 2021. 11(1): p. 14608.

- Li, Z. , et al., Neutrophil extracellular traps potentiate effector T cells via endothelial senescence in uveitis. JCI Insight, 2025. 10(2).

- Rolas, L. , et al., Senescent endothelial cells promote pathogenic neutrophil trafficking in inflamed tissues. EMBO reports, 2024. 25(9): p. 3842-3869.

- Appelman, B. , et al., Muscle abnormalities worsen after post-exertional malaise in long COVID. Nature Communications, 2024. 15(1): p. 17.

- Pantsulaia, I., W. M. Ciszewski, and J. Niewiarowska, Senescent endothelial cells: Potential modulators of immunosenescence and ageing. Ageing Research Reviews, 2016. 29: p. 13-25.

- Müller, L. and S. Di Benedetto, Inflammaging, immunosenescence, and cardiovascular aging: insights into long COVID implications. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 2024. 11.

- Francavilla, F. , et al., Inflammaging and Immunosenescence in the Post-COVID Era: Small Molecules, Big Challenges. ChemMedChem. n/a(n/a): p. e202400672.

- Schmitt, C.A. , et al., COVID-19 and cellular senescence. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2023. 23(4): p. 251-263.

- Pedroso, R.B. , et al., Rapid progression of CD8 and CD4 T cells to cellular exhaustion and senescence during SARS-CoV2 infection. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 2024. 116(6): p. 1385-1397.

- De Biasi, S. , et al., Marked T cell activation, senescence, exhaustion and skewing towards TH17 in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 3434.

- Zhang, J. , et al., Elevated CD4(+) T Cell Senescence Associates with Impaired Immune Responsiveness in Severe COVID-19. Aging Dis, 2024. 16(1): p. 498-511.

- Srivastava, R. , et al., High Frequencies of Phenotypically and Functionally Senescent and Exhausted CD56(+)CD57(+)PD-1(+) Natural Killer Cells, SARS-CoV-2-Specific Memory CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells Associated with Severe Disease in Unvaccinated COVID-19 Patients. bioRxiv, 2022.

- Wiech, M. , et al., Remodeling of T Cell Dynamics During Long COVID Is Dependent on Severity of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Frontiers in Immunology, 2022. 13.

- Van Campenhout, J. , et al., Unravelling the Connection Between Energy Metabolism and Immune Senescence/Exhaustion in Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Biomolecules, 2025. 15(3): p. 357.

- Arora, S. , et al., Invariant natural killer and T-cells coordinate removal of senescent cells. Med, 2021. 2(8): p. 938-950.e8.

- Kale, A. , et al., Role of immune cells in the removal of deleterious senescent cells. Immunity & Ageing, 2020. 17(1): p. 16.

- Eaton-Fitch, N. , et al., A systematic review of natural killer cells profile and cytotoxic function in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Systematic Reviews, 2019. 8(1): p. 279.

- Baraniuk, J.N., N. Eaton-Fitch, and S. Marshall-Gradisnik, Meta-analysis of natural killer cell cytotoxicity in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Frontiers in Immunology, 2024. 15.

- Thierry, A.R. , NETosis creates a link between diabetes and Long COVID. Physiological Reviews, 2024. 104(2): p. 651-654.

- Shafqat, A. , et al., Cellular senescence in brain aging and cognitive decline. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 2023. 15.

- Binet, F. , et al., Neutrophil extracellular traps target senescent vasculature for tissue remodeling in retinopathy. Science, 2020. 369(6506): p. eaay5356.

- Pretorius, E. , et al., Circulating microclots are structurally associated with Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and their amounts are strongly elevated in long COVID patients. 2024.

- Gil, A. , et al., Identification of CD8 T-cell dysfunction associated with symptoms in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and Long COVID and treatment with a nebulized antioxidant/anti-pathogen agent in a retrospective case series. Brain Behav Immun Health, 2024. 36: p. 100720.

- Curriu, M. , et al., Screening NK-, B- and T-cell phenotype and function in patients suffering from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. J Transl Med, 2013. 11: p. 68.

- Mandarano, A.H. , et al., Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients exhibit altered T cell metabolism and cytokine associations. J Clin Invest, 2020. 130(3): p. 1491-1505.

- Maya, J. , Surveying the Metabolic and Dysfunctional Profiles of T Cells and NK Cells in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023. 24(15): p. 11937.

- Arese, P., F. Turrini, and E. Schwarzer, Band 3/Complement-mediated Recognition and Removal of Normally Senescent and Pathological Human Erythrocytes. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry, 2005. 16(4-6): p. 133-146.

- Lutz, L. , et al., Evaluation of Immune Dysregulation in an Austrian Patient Cohort Suffering from Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Biomolecules, 2021. 11(9): p. 1359.

- Rohrhofer, J. , et al., Immunological Patient Stratification in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2024. 13(1): p. 275.

- Baillie, K. , et al., Complement dysregulation is a prevalent and therapeutically amenable feature of long COVID. Med, 2024. 5(3): p. 239-253.e5.

- Yu, S. , et al., M1 macrophages accelerate renal glomerular endothelial cell senescence through reactive oxygen species accumulation in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. International Immunopharmacology, 2020. 81: p. 106294.

- Gao, C. , et al., Endothelial cell phagocytosis of senescent neutrophils decreases procoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost, 2013. 109(06): p. 1079-1090.

- Sun, Y. , et al., Immunometabolic changes and potential biomarkers in CFS peripheral immune cells revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Journal of Translational Medicine, 2024. 22(1): p. 925.

- Almulla, A.F. , et al., Immune activation and immune-associated neurotoxicity in Long-COVID: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 103 studies comprising 58 cytokines/chemokines/growth factors. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 2024.

- Altmann, D.M. , et al., The immunology of long COVID. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2023. 23(10): p. 618-634.

- Riederer, I. , et al., Irradiation-induced up-regulation of HLA-E on macrovascular endothelial cells confers protection against killing by activated natural killer cells. PLoS one, 2010. 5(12): p. e15339.

- Kiss, T. , et al., Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies senescent cerebromicrovascular endothelial cells in the aged mouse brain. Geroscience, 2020. 42(2): p. 429-444.

- Knopp, R.C. , et al., Cellular senescence and the blood-brain barrier: Implications for aging and age-related diseases. Exp Biol Med (Maywood), 2023. 248(5): p. 399-411.

- Graves, S.I. and D.J. Baker, Implicating endothelial cell senescence to dysfunction in the ageing and diseased brain. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology, 2020. 127(2): p. 102-110.

- Sakamuri, S.S.V.P. , et al., Glycolytic and Oxidative Phosphorylation Defects Precede the Development of Senescence in Primary Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells. GeroScience, 2022. 44(4): p. 1975-1994.

- Phoenix, A., R. Chandran, and A. Ergul, Cerebral microvascular senescence and inflammation in diabetes. Frontiers in Physiology, 2022. 13: p. 864758.

- Cantuti-Castelvetri, L. , et al., Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science, 2020. 370(6518): p. 856-860.

- Lukiw, W.J., A. Pogue, and J.M. Hill, SARS-CoV-2 Infectivity and Neurological Targets in the Brain. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, 2022. 42(1): p. 217-224.

- Stein, S.R. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 infection and persistence in the human body and brain at autopsy. Nature, 2022. 612(7941): p. 758-763.

- Volle, R. , et al., Differential permissivity of human cerebrovascular endothelial cells to enterovirus infection and specificities of serotype EV-A71 in crossing an in vitro model of the human blood–brain barrier. Journal of General Virology, 2015. 96(7): p. 1682-1695.

- Higazy, D. , et al., Altered gene expression in human brain microvascular endothelial cells in response to the infection of influenza H1N1 virus. Animal Diseases, 2022. 2(1): p. 25.

- Lei, Y. , et al., Influenza H7N9 virus disrupts the monolayer human brain microvascular endothelial cells barrier in vitro. Virology Journal, 2023. 20(1): p. 219.

- Real, M.G.C. , et al., Endothelial Cell Senescence Effect on the Blood-Brain Barrier in Stroke and Cognitive Impairment. Neurology, 2024. 103(11): p. e210063.

- Ahire, C. , et al., Accelerated cerebromicrovascular senescence contributes to cognitive decline in a mouse model of paclitaxel (Taxol)-induced chemobrain. Aging Cell, 2023. 22(7): p. e13832.

- Budamagunta, V. , et al., Effect of peripheral cellular senescence on brain aging and cognitive decline. Aging Cell, 2023. 22(5): p. e13817.

- Pushpam, M. , et al., Recurrent endothelin-1 mediated vascular insult leads to cognitive impairment protected by trophic factor pleiotrophin. Experimental Neurology, 2024. 381: p. 114938.

- Greene, C. , et al., Blood–brain barrier disruption and sustained systemic inflammation in individuals with long COVID-associated cognitive impairment. Nature Neuroscience, 2024. 27(3): p. 421-432.

- Chaganti, J. , et al., Blood brain barrier disruption and glutamatergic excitotoxicity in post-acute sequelae of SARS COV-2 infection cognitive impairment: potential biomarkers and a window into pathogenesis. Frontiers in Neurology, 2024. 15.

- Williams PhD, M.V. , et al., Epstein-Barr Virus dUTPase Induces Neuroinflammatory Mediators: Implications for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Clinical Therapeutics, 2019. 41(5): p. 848-863.

- Ungvari, Z. , et al., Ionizing radiation promotes the acquisition of a senescence-associated secretory phenotype and impairs angiogenic capacity in cerebromicrovascular endothelial cells: role of increased DNA damage and decreased DNA repair capacity in microvascular radiosensitivity. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 2013. 68(12): p. 1443-1457.

- VanElzakker, M.B. , et al., Neuroinflammation in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) as assessed by [11C]PBR28 PET correlates with vascular disease measures. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 2024. 119: p. 713-723.

- Shan, Z.Y. , et al., Neuroimaging characteristics of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): a systematic review. Journal of Translational Medicine, 2020. 18(1): p. 335.

- Ashktorab, H. , et al., Gastrointestinal Manifestations and Their Association with Neurologic and Sleep Problems in Long COVID-19 Minority Patients: A Prospective Follow-Up Study. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 2024. 69(2): p. 562-569.

- Steinsvik, E.K. , et al., Gastric dysmotility and gastrointestinal symptoms in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 2023. 58(7): p. 718-725.

- Guo, C. , et al., Deficient butyrate-producing capacity in the gut microbiome is associated with bacterial network disturbances and fatigue symptoms in ME/CFS. Cell Host & Microbe, 2023. 31(2): p. 288-304.e8.

- Shukla, S.K. , et al., Changes in Gut and Plasma Microbiome following Exercise Challenge in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). PLOS ONE, 2015. 10(12): p. e0145453.

- Giloteaux, L. , et al., Reduced diversity and altered composition of the gut microbiome in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome, 2016. 4(1): p. 30.

- Liu, Q. , et al., Gut microbiota dynamics in a prospective cohort of patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Gut, 2022. 71(3): p. 544-552.

- Su, Q. , et al., The gut microbiome associates with phenotypic manifestations of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Cell Host & Microbe, 2024. 32(5): p. 651-660.e4.

- Martín, F. , et al., Increased gut permeability and bacterial translocation are associated with fibromyalgia and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: implications for disease-related biomarker discovery. Frontiers in Immunology, 2023. 14.

- Mouchati, C. , et al., Increase in gut permeability and oxidized ldl is associated with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2. Frontiers in Immunology, 2023. 14.

- Stallmach, A. , et al., The gastrointestinal microbiota in the development of ME/CFS: a critical view and potential perspectives. Frontiers in Immunology, 2024. 15.

- Wang, J.-H. , et al., Clinical evidence of the link between gut microbiome and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a retrospective review. European Journal of Medical Research, 2024. 29(1): p. 148.

- Zollner, A. , et al., The Intestine in Acute and Long COVID: Pathophysiological Insights and Key Lessons. Yale J Biol Med, 2024. 97(4): p. 447-462.

- Liu, S., A. S. Devason, and M. Levy, From intestinal metabolites to the brain: Investigating the mysteries of Long COVID. Clin Transl Med, 2024. 14(3): p. e1608.

- Ke, Y. , et al., Gut flora-dependent metabolite Trimethylamine-N-oxide accelerates endothelial cell senescence and vascular aging through oxidative stress. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2018. 116: p. 88-100.

- Saeedi Saravi, S.S. , et al., Gut microbiota-dependent increase in phenylacetic acid induces endothelial cell senescence during aging. BioRxiv, 2023: p. 2023.11. 17.567594.

- Poole, D.C., B. J. Behnke, and T.I. Musch, The role of vascular function on exercise capacity in health and disease. The Journal of Physiology, 2021. 599(3): p. 889-910.

- Korthuis, R.J. , Exercise hyperemia and regulation of tissue oxygenation during muscular activity. Skeletal Muscle Circulation, 2011.

- Joseph, P. , et al., Insights From Invasive Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing of Patients With Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. CHEST, 2021. 160(2): p. 642-651.

- Singh, I. , et al., Persistent Exertional Intolerance After COVID-19: Insights From Invasive Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing. Chest, 2022. 161(1): p. 54-63.

- Bertinat, R. , et al., Decreased NO production in endothelial cells exposed to plasma from ME/CFS patients. Vascular Pharmacology, 2022. 143: p. 106953.

- Barrett-O'Keefe, Z. , et al., Taming the "sleeping giant": the role of endothelin-1 in the regulation of skeletal muscle blood flow and arterial blood pressure during exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2013. 304(1): p. H162-9.

- Rapoport, R.M. and D. Merkus, Endothelin-1 Regulation of Exercise-Induced Changes in Flow: Dynamic Regulation of Vascular Tone. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2017. 8.

- Wray, D.W. , et al., Endothelin-1-mediated vasoconstriction at rest and during dynamic exercise in healthy humans. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 2007. 293(4): p. H2550-H2556.

- Bevan, G.H. , et al., Endothelin-1 and peak oxygen consumption in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart & Lung, 2021. 50(3): p. 442-446.

- Liu, S.-Y. , et al., Endothelin-1 impairs skeletal muscle myogenesis and development via ETB receptors and p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Clinical Science, 2024. 138(12): p. 711-723.

- Tsai, C.H. , et al., Endothelin-1-mediated miR-let-7g-5p triggers interlukin-6 and TNF-α to cause myopathy and chronic adipose inflammation in elderly patients with diabetes mellitus. Aging (Albany NY), 2022. 14(8): p. 3633-3651.

- Horinouchi, T. , et al., Endothelin-1 suppresses insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation and glucose uptake via GPCR kinase 2 in skeletal muscle cells. British Journal of Pharmacology, 2016. 173(6): p. 1018-1032.

- Alcalde-Estévez, E. , et al., Endothelin-1 induces cellular senescence and fibrosis in cultured myoblasts. A potential mechanism of aging-related sarcopenia. Aging (Albany NY), 2020. 12(12): p. 11200-11223.

- Liu, Z. , et al., Increased circulating fibronectin, depletion of natural IgM and heightened EBV, HSV-1 reactivation in ME/CFS and long COVID. medRxiv, 2023.

- Aschman, T. , et al., Post-COVID exercise intolerance is associated with capillary alterations and immune dysregulations in skeletal muscles. Acta Neuropathol Commun, 2023. 11(1): p. 193.

- Hejbøl, E.K. , et al., Myopathy as a cause of fatigue in long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms: Evidence of skeletal muscle histopathology. Eur J Neurol, 2022. 29(9): p. 2832-2841.

- Rahman, F.A. and M.P. Krause, PAI-1, the Plasminogen System, and Skeletal Muscle. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020. 21(19): p. 7066.

- Young, L.V. , et al., Loss of dystrophin expression in skeletal muscle is associated with senescence of macrophages and endothelial cells. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology, 2021. 321(1): p. C94-C103.

- Sugihara, H. , et al., Cellular senescence-mediated exacerbation of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 16385.

- Berenjabad, N.J., V. Nejati, and J. Rezaie, Angiogenic ability of human endothelial cells was decreased following senescence induction with hydrogen peroxide: possible role of vegfr-2/akt-1 signaling pathway. BMC Mol Cell Biol, 2022. 23(1): p. 31.

- Dinulovic, I., R. Furrer, and C. Handschin, Plasticity of the Muscle Stem Cell Microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2017. 1041: p. 141-169.

- Christov, C. , et al., Muscle Satellite Cells and Endothelial Cells: Close Neighbors and Privileged Partners. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 2007. 18(4): p. 1397-1409.

- Mierzejewski, B. , et al., miRNA-126a plays important role in myoblast and endothelial cell interaction. Scientific Reports, 2023. 13(1): p. 15046.

- Keller, B. , et al., Cardiopulmonary and metabolic responses during a 2-day CPET in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: translating reduced oxygen consumption to impairment status to treatment considerations. Journal of Translational Medicine, 2024. 22(1): p. 627.

- van Campen, C.M.C. and F.C. Visser, Comparing Idiopathic Chronic Fatigue and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) in Males: Response to Two-Day Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing Protocol. Healthcare, 2021. 9(6): p. 683.

- Pretorius, E. , et al., Acute induction of anomalous and amyloidogenic blood clotting by molecular amplification of highly substoichiometric levels of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J R Soc Interface, 2016. 13(122).

- Pretorius, E. , et al., Both lipopolysaccharide and lipoteichoic acids potently induce anomalous fibrin amyloid formation: assessment with novel Amytracker™ stains†. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 2018. 15(139): p. 20170941.

- Kell, D.B. and E. Pretorius, Proteins behaving badly. Substoichiometric molecular control and amplification of the initiation and nature of amyloid fibril formation: lessons from and for blood clotting. Prog Biophys Mol Biol, 2017. 123: p. 16-41.

- Ryu, J.K. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces abnormal inflammatory blood clots neutralized by fibrin immunotherapy. biorxiv, 2021: p. 2021.10. 12.464152.

- Bonilla, H. , et al., Comparative analysis of extracellular vesicles in patients with severe and mild myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Frontiers in Immunology, 2022. 13: p. 841910.

- Jahanbani, F. , et al., Phenotypic characteristics of peripheral immune cells of Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome via transmission electron microscopy: A pilot study. PloS One, 2022. 17(8): p. e0272703.

- Bochenek, M.L. , et al., The endothelial tumor suppressor p53 is essential for venous thrombus formation in aged mice. Blood Advances, 2018. 2(11): p. 1300-1314.

- Valenzuela, C.A. , et al., SASP-Dependent Interactions between Senescent Cells and Platelets Modulate Migration and Invasion of Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci, 2019. 20(21).

- Venturini, W. , et al., Platelet Activation Is Triggered by Factors Secreted by Senescent Endothelial HMEC-1 Cells In Vitro. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 21(9).

- Ma, S. , et al., Vascular Aging and Atherosclerosis: A Perspective on Aging. Aging Dis, 2024. 16(1): p. 33-48.

- Silva, G.C. , et al., Replicative senescence promotes prothrombotic responses in endothelial cells: Role of NADPH oxidase- and cyclooxygenase-derived oxidative stress. Experimental Gerontology, 2017. 93: p. 7-15.

- Khan, S.Y. , et al., Premature senescence of endothelial cells upon chronic exposure to TNFα can be prevented by N-acetyl cysteine and plumericin. Sci Rep, 2017. 7: p. 39501.

- Abbas, M. , et al., Endothelial Microparticles From Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients Induce Premature Coronary Artery Endothelial Cell Aging and Thrombogenicity. Circulation, 2017. 135(3): p. 280-296.

- Bochenek, M.L., E. Schütz, and K. Schäfer, Endothelial cell senescence and thrombosis: Ageing clots. Thrombosis Research, 2016. 147: p. 36-45.

- Sepúlveda, C., I. Palomo, and E. Fuentes, Mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction during aging: Predisposition to thrombosis. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 2017. 164: p. 91-99.

- Mas-Bargues, C., C. Borrás, and M. Alique, The contribution of extracellular vesicles from senescent endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells to vascular calcification. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 2022. 9: p. 854726.

- Mørk, M. , et al., Elevated blood plasma levels of tissue factor-bearing extracellular vesicles in patients with atrial fibrillation. Thrombosis Research, 2019. 173: p. 141-150.

- Kruger, A. , et al., Proteomics of fibrin amyloid microclots in long COVID/post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) shows many entrapped pro-inflammatory molecules that may also contribute to a failed fibrinolytic system. Cardiovascular Diabetology, 2022. 21(1): p. 190.

- Rubin, O. , et al., Microparticles in stored red blood cells: submicron clotting bombs? Blood Transfus, 2010. 8 Suppl 3(Suppl 3): p. s31-8.

- Schuermans, S., C. Kestens, and P.E. Marques, Systemic mechanisms of necrotic cell debris clearance. Cell Death & Disease, 2024. 15(8): p. 557.

- Walton, C.C. , et al., Senescence as an Amyloid Cascade: The Amyloid Senescence Hypothesis. Front Cell Neurosci, 2020. 14: p. 129.

- Li, R. , et al., Alzheimer’s Amyloid-β Accelerates Cell Senescence and Suppresses SIRT1 in Human Neural Stem Cells. Biomolecules, 2024. 14(2): p. 189.

- Flanary, B.E. , et al., Evidence That Aging And Amyloid Promote Microglial Cell Senescence. Rejuvenation Research, 2007. 10(1): p. 61-74.

- Grobbelaar, Lize M., et al., SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1 induces fibrin(ogen) resistant to fibrinolysis: implications for microclot formation in COVID-19. Bioscience Reports, 2021. 41(8).

- Lopez-Vilchez, I. , et al., Tissue factor-enriched vesicles are taken up by platelets and induce platelet aggregation in the presence of factor VIIa. Thromb Haemost, 2007. 97(2): p. 202-11.

- Tabachnikova, A. , et al., The Role of Epstein-Barr Virus in Long COVID. The Journal of Immunology, 2024. 212(1_Supplement): p. 1121_6087-1121_6087.

- Vojdani, A. , et al., Reactivation of herpesvirus type 6 and IgA/IgM-mediated responses to activin-A underpin long COVID, including affective symptoms and chronic fatigue syndrome. Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 2024. 36(3): p. 172-184.

- Chen, Y.-L. , et al., The Epstein-Barr virus replication and transcription activator, Rta/BRLF1, induces cellular senescence in epithelial cells. Cell Cycle, 2009. 8(1): p. 58-65.

- Huang, W., L. Bai, and H. Tang, Epstein-Barr virus infection: the micro and macro worlds. Virology Journal, 2023. 20(1): p. 220.

- Ou, H.-L. , et al., Cellular senescence in cancer: from mechanisms to detection. Molecular Oncology, 2021. 15(10): p. 2634-2671.

- García-Fleitas, J. , et al., Chemical Strategies for the Detection and Elimination of Senescent Cells. Accounts of Chemical Research, 2024. 57(9): p. 1238-1253.

- Neri, F. , et al., A Fully-Automated Senescence Test (FAST) for the high-throughput quantification of senescence-associated markers. GeroScience, 2024. 46(5): p. 4185-4202.

- Veroutis, D. , et al., Senescent cells in giant cell arteritis display an inflammatory phenotype participating in tissue injury via IL-6-dependent pathways. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2024. 83(3): p. 342-350.

- Lagoumtzi, S.M. and N. Chondrogianni, Senolytics and senomorphics: Natural and synthetic therapeutics in the treatment of aging and chronic diseases. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2021. 171: p. 169-190.

- Chaib, S., T. Tchkonia, and J.L. Kirkland, Cellular senescence and senolytics: the path to the clinic. Nature medicine, 2022. 28(8): p. 1556-1568.

- Zhang, L. , et al., Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: senolytics and senomorphics. The FEBS journal, 2023. 290(5): p. 1362-1383.

- Aguado, J. , et al., Senolytic therapy alleviates physiological human brain aging and COVID-19 neuropathology. Nature Aging, 2023. 3(12): p. 1561-1575.

| Virus | Endothelial Dysfunction | Direct Endothelial Infection | Induction of Endothelial Senescence | Implicated in ME/CFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | [38,51,104,114,115,116] | [117,118,119,120,121] | [104,105,106,122] | [4,7,8,9,123,124] |

| EBV | [63,125,126] | [125,127,128] | Unknown | [129,130,131,132] |

| HHV-6 | [63,133,134,135] | [134,135,136,137] | Unknown | [130,138] |

| Influenza A | [139,140,141,142,143] | [144,145,146] | [139,147] | [148,149] |

| Enteroviruses | [150,151,152,153] | [150,151,154,155,156,157] | Unknown | [158,159,160] |

| Parvovirus B19 | [156,161,162,163] | [164,165] | Unknown | [166,167,168,169] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).