Submitted:

23 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

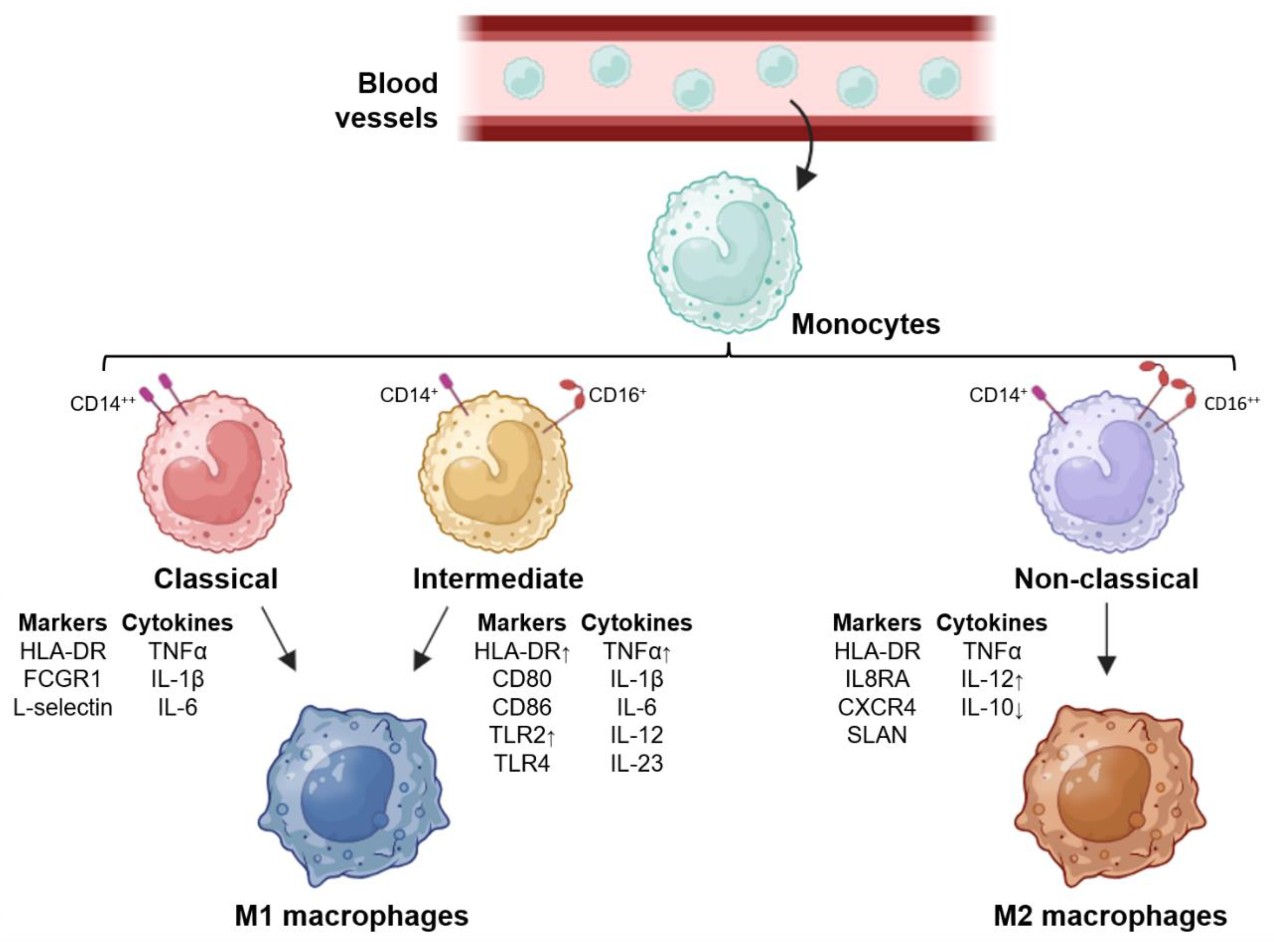

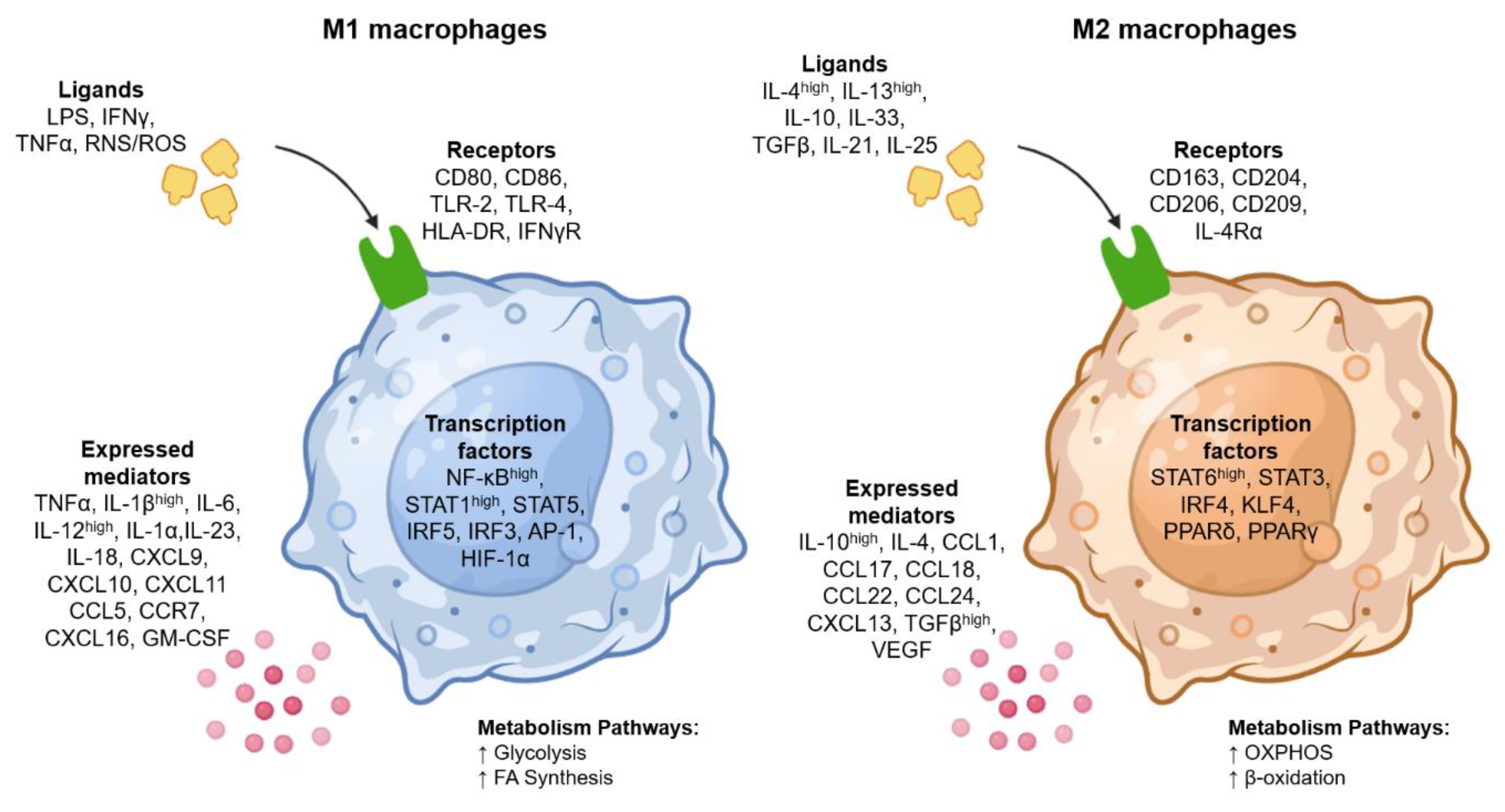

Macrophage Polarization: M1 and M2 Phenotypes

M1 Macrophage’s Phenotype

M2 Macrophage’s Phenotype

Inflammation of the Adipose Tissue in Obesity

Functions of Macrophages in the Healthy Adipose Tissue

Macrophages in the Microenvironment of Obese Adipose Tissue

Phenotypic Switch of Macrophages in the “Obese” Adipose Tissue

Impact of Macrophage Polarization in Obesity

Hypoxia as the Main Driver of Adipose Tissue Dysfunction

The Role of PPARγ in Macrophage Polarization

Macrophages in the Crown-like Structures (CLS)

Obesity-Associated Metabolic Risk and Macrophage Phenotypic Switch

Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

References

- Hirayama D, Iida T, Nakase H. The Phagocytic Function of Macrophage-Enforcing Innate Immunity and Tissue Homeostasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(1). [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Saeed AFUH, Liu Q, Jiang Q, Xu H, Xiao GG, et al. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2023;8(1). [CrossRef]

- Watanabe S, Alexander M, Misharin A V., Budinger GRS. The role of macrophages in the resolution of inflammation. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2019;129(7): 2619–2628. [CrossRef]

- Yousaf H, Khan MIU, Ali I, Munir MU, Lee KY. Emerging role of macrophages in noninfectious diseases: An update. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2023;161: 114426. [CrossRef]

- Kadomoto S, Izumi K, Mizokami A. Macrophage Polarity and Disease Control. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(1). [CrossRef]

- Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2008;8(12): 958. [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Carrillo FJ, Bravo-Cuellar A. Los macrófagos, ángeles o demonios. Gaceta Mexicana de Oncología. 2013;12(1): 1–3. https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-gaceta-mexicana-oncologia-305-articulo-los-macrofagos-angeles-o-demonios-X1665920113933087.

- Yunna C, Mengru H, Lei W, Weidong C. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization. European journal of pharmacology. 2020;877. [CrossRef]

- Savulescu-Fiedler I, Mihalcea R, Dragosloveanu S, Scheau C, Octavian Baz R, Caruntu A, et al. The Interplay between Obesity and Inflammation. Life 2024, Vol. 14, Page 856. 2024;14(7): 856. [CrossRef]

- Kawai T, Autieri M V., Scalia R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology. 2021;320(3): C375–C391. [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, metaflammation and immunometabolic disorders. Nature. 2017;542(7640): 177–185. [CrossRef]

- Saltiel AR, Olefsky JM. Inflammatory mechanisms linking obesity and metabolic disease. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2017;127(1): 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Chait A, den Hartigh LJ. Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2020;7. [CrossRef]

- Ruck L, Wiegand S, Kühnen P. Relevance and consequence of chronic inflammation for obesity development. Molecular and Cellular Pediatrics 2023 10:1. 2023;10(1): 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Chaintreuil P, Kerreneur E, Bourgoin M, Savy C, Favreau C, Robert G, et al. The generation, activation, and polarization of monocyte-derived macrophages in human malignancies. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Cutolo M, Campitiello R, Gotelli E, Soldano S. The Role of M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization in Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovitis. Frontiers in Immunology. 2022;13. [CrossRef]

- Hofer TP, van de Loosdrecht AA, Stahl-Hennig C, Cassatella MA, Ziegler-Heitbrock L. 6-Sulfo LacNAc (Slan) as a Marker for Nonclassical Monocytes. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019;10. [CrossRef]

- Hirayama D, Iida T, Nakase H. The Phagocytic Function of Macrophage-Enforcing Innate Immunity and Tissue Homeostasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(1). [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Zhang L, Shi J, He R, Yang W, Habtezion A, et al. Macrophage phenotypic switch orchestrates the inflammation and repair/regeneration following acute pancreatitis injury. EBioMedicine. 2020;58: 102920. [CrossRef]

- Strizova Z, Benesova I, Bartolini R, Novysedlak R, Cecrdlova E, Foley LK, et al. M1/M2 macrophages and their overlaps – myth or reality? Clinical Science (London, England : 1979). 2023;137(15): 1067. [CrossRef]

- Yao Y, Xu XH, Jin L. Macrophage polarization in physiological and pathological pregnancy. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019;10(MAR): 434399. [CrossRef]

- Duque GA, Descoteaux A. Macrophage Cytokines: Involvement in Immunity and Infectious Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014;5(OCT). [CrossRef]

- Peng Y, Zhou M, Yang H, Qu R, Qiu Y, Hao J, et al. Regulatory Mechanism of M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization in the Development of Autoimmune Diseases. Mediators of Inflammation. 2023;2023. [CrossRef]

- Mily A, Kalsum S, Loreti MG, Rekha RS, Muvva JR, Lourda M, et al. Polarization of M1 and M2 Human Monocyte-Derived Cells and Analysis with Flow Cytometry upon Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2020;2020(163): 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Patel U, Rajasingh S, Samanta S, Cao T, Dawn B, Rajasingh J. Macrophage polarization in response to epigenetic modifiers during infection and inflammation. Drug discovery today. 2017;22(1): 186. [CrossRef]

- Xue C, Tian J, Cui Z, Liu Y, Sun D, Xiong M, et al. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated M1 macrophage-dependent nanomedicine remodels inflammatory microenvironment for osteoarthritis recession. Bioactive materials. 2023;33: 545–561. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H cun, Yan X yan Y, Yu W wen, Liang X qin, Du X yan, Liu Z chang, et al. Lactic acid in macrophage polarization: The significant role in inflammation and cancer. International reviews of immunology. 2022;41(1): 4–18. [CrossRef]

- Irey EA, Lassiter CM, Brady NJ, Chuntova P, Wang Y, Knutson TP, et al. JAK/STAT inhibition in macrophages promotes therapeutic resistance by inducing expression of protumorigenic factors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2019;116(25): 12442–12451. [CrossRef]

- Boutilier AJ, Elsawa SF. Macrophage Polarization States in the Tumor Microenvironment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(13). [CrossRef]

- Li X, Mara AB, Musial SC, Kolling FW, Gibbings SL, Gerebtsov N, et al. Coordinated chemokine expression defines macrophage subsets across tissues. Nature immunology. 2024;25(6): 1110–1122. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Wang M, Lu T, Liu Y, Hong W, He X, et al. JMJD6 in tumor-associated macrophage regulates macrophage polarization and cancer progression via STAT3/IL-10 axis. Oncogene. 2023;42(37): 2737–2750. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran P, Izadjoo S, Stimely J, Palaniyandi S, Zhu X, Tafuri W, et al. Regulatory Macrophages Inhibit Alternative Macrophage Activation and Attenuate Pathology Associated with Fibrosis. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950). 2019;203(8): 2130–2140. [CrossRef]

- Krzyszczyk P, Schloss R, Palmer A, Berthiaume F. The Role of Macrophages in Acute and Chronic Wound Healing and Interventions to Promote Pro-wound Healing Phenotypes. Frontiers in Physiology. 2018;9(MAY): 419. [CrossRef]

- Willenborg S, Injarabian L, Eming SA. Role of Macrophages in Wound Healing. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2022;14(12). [CrossRef]

- Gao J, Liang Y, Wang L. Shaping Polarization Of Tumor-Associated Macrophages In Cancer Immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunology. 2022;13. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Stokes J V., Tan W, Pruett SB. An optimized flow cytometry panel for classifying macrophage polarization. Journal of immunological methods. 2022;511. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Jimenez D, Kolb JP, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoids as Regulators of Macrophage-Mediated Tissue Homeostasis. Frontiers in Immunology. 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Viola A, Munari F, Sánchez-Rodríguez R, Scolaro T, Castegna A. The metabolic signature of macrophage responses. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019;10(JULY): 466337. [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Heavy Burden of Obesity: The economics of prevention. OECD Health Policy Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ruze R, Liu T, Zou X, Song J, Chen Y, Xu R, et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: connections in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatments. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Jin X, Qiu T, Li L, Yu R, Chen X, Li C, et al. Pathophysiology of obesity and its associated diseases. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. B. 2023;13(6): 2403. [CrossRef]

- Grundy SM. Multifactorial causation of obesity: implications for prevention. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1998;67(3 Suppl). [CrossRef]

- Maurizi G, Della Guardia L, Maurizi A, Poloni A. Adipocytes properties and crosstalk with immune system in obesity-related inflammation. Journal of cellular physiology. 2018;233(1): 88–97. [CrossRef]

- Esteve Ràfols M. Adipose tissue: Cell heterogeneity and functional diversity. Endocrinología y Nutrición (English Edition). 2014;61(2): 100–112. [CrossRef]

- Richard AJ, White U, Elks CM, Stephens JM. Adipose Tissue: Physiology to Metabolic Dysfunction. Endotext. 2020; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555602/.

- Ahmed S, Shah P, Ahmed O. Biochemistry, Lipids. StatPearls. 2023; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525952/.

- Maniyadath B, Zhang Q, Gupta RK, Mandrup S. Adipose tissue at single-cell resolution. Cell Metabolism. 2023;35(3): 386–413. [CrossRef]

- Coelho M, Oliveira T, Fernandes R. Biochemistry of adipose tissue: an endocrine organ. Archives of Medical Science : AMS. 2013;9(2): 191. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Yun K, Mu R. A review on the biology and properties of adipose tissue macrophages involved in adipose tissue physiological and pathophysiological processes. Lipids in Health and Disease. 2020;19(1): 1–9. [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke RW. Adipose tissue and the physiologic underpinnings of metabolic disease. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2018;14(11): 1755–1763. [CrossRef]

- Horwitz A, Birk R. Adipose Tissue Hyperplasia and Hypertrophy in Common and Syndromic Obesity—The Case of BBS Obesity. Nutrients. 2023;15(15). [CrossRef]

- Longo M, Zatterale F, Naderi J, Parrillo L, Formisano P, Raciti GA, et al. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction as Determinant of Obesity-Associated Metabolic Complications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019;20(9). [CrossRef]

- Röszer T. Adipose Tissue Immunometabolism and Apoptotic Cell Clearance. Cells 2021, Vol. 10, Page 2288. 2021;10(9): 2288. [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez VJ, Redondo-Flórez L, Beltrán-Velasco AI, Martín-Rodríguez A, Martínez-Guardado I, Navarro-Jiménez E, et al. The Role of Adipokines in Health and Disease. Biomedicines. 2023;11(5). [CrossRef]

- Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. Adipocytes as regulators of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Nature. 2006;444(7121): 847. [CrossRef]

- Goossens GH. The Metabolic Phenotype in Obesity: Fat Mass, Body Fat Distribution, and Adipose Tissue Function. Obesity Facts. 2017;10(3): 207. [CrossRef]

- Carmona WS, Carrillo Álvarez E, Jesús A, Oliver S. Obesity as a Complex Chronic Disease. Current Research in Diabetes & Obesity Journal. 2017;7(1): 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Ziolkowska S, Binienda A, Jablkowski M, Szemraj J, Czarny P. The Interplay between Insulin Resistance, Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Base Excision Repair and Metabolic Syndrome in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(20): 11128. [CrossRef]

- Maliszewska K, Kretowski A. Brown Adipose Tissue and Its Role in Insulin and Glucose Homeostasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(4): 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Meex RCR, Blaak EE, van Loon LJC. Lipotoxicity plays a key role in the development of both insulin resistance and muscle atrophy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Obesity Reviews. 2019;20(9): 1205. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Q, An YA, Scherer PE. Mitochondrial regulation and white adipose tissue homeostasis. Trends in Cell Biology. 2022;32(4): 351–364. [CrossRef]

- Man K, Kallies A, Vasanthakumar A. Resident and migratory adipose immune cells control systemic metabolism and thermogenesis. Cellular & Molecular Immunology 2021 19:3. 2021;19(3): 421–431. [CrossRef]

- Sakers A, De Siqueira MK, Seale P, Villanueva CJ. Adipose-tissue plasticity in health and disease. Cell. 2022;185(3): 419–446. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura K, Fuster JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines: A link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Journal of Cardiology. 2014;63(4): 250–259. [CrossRef]

- Luo L, Liu M. Adiponectin: Friend or foe in obesity and inflammation. Medical Review. 2022;2(4): 349–362. [CrossRef]

- Corvera S, Solivan-Rivera J, Yang Loureiro Z. Angiogenesis in adipose tissue and obesity. Angiogenesis. 2022;25(4): 439. [CrossRef]

- Surmi BK, Hasty AH. Macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue: initiation, propagation and remodeling. Future lipidology. 2008;3(5): 545. [CrossRef]

- Ross EA, Devitt A, Johnson JR. Macrophages: The Good, the Bad, and the Gluttony. Frontiers in Immunology. 2021;12: 708186. [CrossRef]

- Opal SM, DePalo VA. Anti-inflammatory cytokines. Chest. 2000;117(4): 1162–1172. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Xiong Y, Zhu H, Ma T, Sun X, Xiao J. Microenvironment-responsive nanosystems for osteoarthritis therapy. Engineered Regeneration. 2024;5(1): 92–110. [CrossRef]

- Madsen MS, Siersbæk R, Boergesen M, Nielsen R, Mandrup S. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ and C/EBPα Synergistically Activate Key Metabolic Adipocyte Genes by Assisted Loading. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2014;34(6): 939. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee R, Bhattacharya P, Gavrilova O, Glass K, Moitra J, Myakishev M, et al. Suppression of the C/EBP family of transcription factors in adipose tissue causes lipodystrophy. Journal of molecular endocrinology. 2011;46(3): 175–192. [CrossRef]

- Neto IV de S, Durigan JLQ, da Silva ASR, Marqueti R de C. Adipose Tissue Extracellular Matrix Remodeling in Response to Dietary Patterns and Exercise: Molecular Landscape, Mechanistic Insights, and Therapeutic Approaches. Biology. 2022;11(5): 765. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ojeda FJ, Méndez-Gutiérrez A, Aguilera CM, Plaza-Díaz J. Extracellular Matrix Remodeling of Adipose Tissue in Obesity and Metabolic Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019;20(19). [CrossRef]

- Sun K, Li X, Scherer PE. Extracellular Matrix (ECM) and Fibrosis in Adipose Tissue: Overview and Perspectives. Comprehensive Physiology. 2023;13(1): 4387. [CrossRef]

- Quail DF, Dannenberg AJ. The obese adipose tissue microenvironment in cancer development and progression. Nature reviews. Endocrinology. 2019;15(3): 139. [CrossRef]

- Zatterale F, Longo M, Naderi J, Raciti GA, Desiderio A, Miele C, et al. Chronic Adipose Tissue Inflammation Linking Obesity to Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Frontiers in Physiology. 2019;10: 1607. [CrossRef]

- Swarup S, Ahmed I, Grigorova Y, Zeltser R. Metabolic Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459248/.

- Hildebrandt X, Ibrahim M, Peltzer N. Cell death and inflammation during obesity: “Know my methods, WAT(son)”. Cell Death & Differentiation 2022 30:2. 2022;30(2): 279–292. [CrossRef]

- Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Obesity-induced inflammatory changes in adipose tissue. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;112(12): 1785–1788. [CrossRef]

- Fain JN. Release of Inflammatory Mediators by Human Adipose Tissue Is Enhanced in Obesity and Primarily by the Nonfat Cells: A Review. Mediators of Inflammation. 2010;2010(1): 513948. [CrossRef]

- Scarano F, Gliozzi M, Zito MC, Guarnieri L, Carresi C, Macrì R, et al. Potential of Nutraceutical Supplementation in the Modulation of White and Brown Fat Tissues in Obesity-Associated Disorders: Role of Inflammatory Signaling. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021;22(7). [CrossRef]

- Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;112(12): 1796–1808. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Deng H, Cui H, Fang J, Zuo Z, Deng J, et al. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget. 2018;9(6): 7204. [CrossRef]

- Kirichenko T V., Markina Y V., Bogatyreva AI, Tolstik T V., Varaeva YR, Starodubova A V. The Role of Adipokines in Inflammatory Mechanisms of Obesity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(23). [CrossRef]

- Frühbeck G, Catalán V, Rodríguez A, Ramírez B, Becerril S, Salvador J, et al. Adiponectin-leptin Ratio is a Functional Biomarker of Adipose Tissue Inflammation. Nutrients. 2019;11(2). [CrossRef]

- Guzik TJ, Skiba DS, Touyz RM, Harrison DG. The role of infiltrating immune cells in dysfunctional adipose tissue. Cardiovascular Research. 2017;113(9): 1009. [CrossRef]

- Luz M, Albarracín G, Yibby A, Torres F, Albarracin G. Adiponectin and Leptin Adipocytokines in Metabolic Syndrome: What Is Its Importance? Dubai Diabetes and Endocrinology Journal. 2020;26(3): 93–102. [CrossRef]

- González-Jurado JA, Suárez-Carmona W, López S, Sánchez-Oliver AJ. Changes in Lipoinflammation Markers in People with Obesity after a Concurrent Training Program: A Comparison between Men and Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(17): 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Appari M, Channon KM, Mcneill E. Metabolic Regulation of Adipose Tissue Macrophage Function in Obesity and Diabetes. [CrossRef]

- Crewe C, An YA, Scherer PE. The ominous triad of adipose tissue dysfunction: inflammation, fibrosis, and impaired angiogenesis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2017;127(1): 74. [CrossRef]

- Jocken JWE, Goossens GH, Boon H, Mason RR, Essers Y, Havekes B, et al. Insulin-mediated suppression of lipolysis in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle of obese type 2 diabetic men and men with normal glucose tolerance. Diabetologia. 2013;56(10): 2255. [CrossRef]

- Zoidis E, Papamikos V. Glucose: Glucose Intolerance. Encyclopedia of Food and Health. 2016; 227–232. [CrossRef]

- Kojta I, Chacińska M, Błachnio-Zabielska A. Obesity, Bioactive Lipids, and Adipose Tissue Inflammation in Insulin Resistance. Nutrients. 2020;12(5). [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Nino ME. The Role of Chronic Inflammation in Obesity-Associated Cancers. ISRN Oncology. 2013;2013: 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, An X, Yang C, Sun W, Ji H, Lian F. The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2023;14: 1149239. [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006 444:7121. 2006;444(7121): 860–867. [CrossRef]

- Gavin KM, Bessesen DH. Sex Differences in Adipose Tissue Function. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America. 2020;49(2): 215. [CrossRef]

- Shu CJ, Benoist C, Mathis D. The immune system’s involvement in obesity-driven type 2 diabetes. Seminars in Immunology. 2012;24(6): 436–442. [CrossRef]

- Choe SS, Huh JY, Hwang IJ, Kim JI, Kim JB. Adipose tissue remodeling: Its role in energy metabolism and metabolic disorders. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2016;7(APR): 178543. [CrossRef]

- Guha Ray A, Odum OP, Wiseman D, Weinstock A. The diverse roles of macrophages in metabolic inflammation and its resolution. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Zheng C, Yang Q, Cao J, Xie N, Liu K, Shou P, et al. Local proliferation initiates macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue during obesity. Cell Death & Disease 2016 7:3. 2016;7(3): e2167–e2167. [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero AD, Key CCC, Kavanagh K. Adipose Tissue Macrophage Polarization in Healthy and Unhealthy Obesity. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2021;8: 625331. [CrossRef]

- Nawaz A, Aminuddin A, Kado T, Takikawa A, Yamamoto S, Tsuneyama K, et al. CD206+ M2-like macrophages regulate systemic glucose metabolism by inhibiting proliferation of adipocyte progenitors. Nature Communications. 2017;8(1). [CrossRef]

- Orliaguet L, Dalmas E, Drareni K, Venteclef N, Alzaid F. Mechanisms of Macrophage Polarization in Insulin Signaling and Sensitivity. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2020;11: 516860. [CrossRef]

- Sun JX, Xu XH, Jin L. Effects of Metabolism on Macrophage Polarization Under Different Disease Backgrounds. Frontiers in Immunology. 2022;13. [CrossRef]

- Michailidou Z, Gomez-Salazar M, Alexaki VI. Innate Immune Cells in the Adipose Tissue in Health and Metabolic Disease. Journal of Innate Immunity. 2022;14(1): 4. [CrossRef]

- Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117(1): 175–184. [CrossRef]

- Huang S, Xing Y, Liu Y. Emerging roles for the ER stress sensor IRE1α in metabolic regulation and disease. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2019;294(49): 18726. [CrossRef]

- Meng H, Matthan NR, Wu D, Li L, Rodríguez-Morató J, Cohen R, et al. Comparison of diets enriched in stearic, oleic, and palmitic acids on inflammation, immune response, cardiometabolic risk factors, and fecal bile acid concentrations in mildly hypercholesterolemic postmenopausal women-randomized crossover trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2019;110(2): 305–315. [CrossRef]

- Fu T, Kemper JK. MicroRNA-34a and Impaired FGF19/21 Signaling in Obesity. Vitamins and Hormones. 2016;101: 175–196. [CrossRef]

- Pan Y, Hui X, Chong Hoo RL, Ye D, Cheung Chan CY, Feng T, et al. Adipocyte-secreted exosomal microRNA-34a inhibits M2 macrophage polarization to promote obesity-induced adipose inflammation. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2019;129(2): 834–849. [CrossRef]

- Tryggestad JB, Teague AM, Sparling DP, Jiang S, Chernausek SD. Macrophage-Derived microRNA-155 Increases in Obesity and Influences Adipocyte Metabolism by Targeting Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma. Obesity. 2019;27(11): 1856–1864. [CrossRef]

- Zhao H, Shang Q, Pan Z, Bai Y, Li Z, Zhang H, et al. Exosomes From Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Attenuate Adipose Inflammation and Obesity Through Polarizing M2 Macrophages and Beiging in White Adipose Tissue. Diabetes. 2018;67(2): 235–247. [CrossRef]

- Cheng CI, Chen PH, Lin YC, Kao YH. High glucose activates Raw264.7 macrophages through RhoA kinase-mediated signaling pathway. Cellular signaling. 2015;27(2): 283–292. [CrossRef]

- Cinti S, Mitchell G, Barbatelli G, Murano I, Ceresi E, Faloia E, et al. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. Journal of Lipid Research. 2005;46(11): 2347–2355. [CrossRef]

- Boutens L, Stienstra R. Adipose tissue macrophages: going off track during obesity. Diabetologia 2016 59:5. 2016;59(5): 879–894. [CrossRef]

- Chylikova J, Dvorackova J, Tauber Z, Kamarad V. M1/M2 macrophage polarization in human obese adipose tissue. http://biomed.papers.upol.cz/doi/10.5507/bp.2018.015.html. 2018;162(2): 79–82. [CrossRef]

- Luquet S, Gaudel C, Holst D, Lopez-Soriano J, Jehl-Pietri C, Fredenrich A, et al. Roles of PPAR delta in lipid absorption and metabolism: a new target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2005;1740(2): 313–317. [CrossRef]

- Göttlicher M, Widmark E, Li Q, Gustafsson JÅ. Fatty acids activate a chimera of the clofibric acid-activated receptor and the glucocorticoid receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(10): 4653–4657. [CrossRef]

- Corrales P, Vidal-Puig A, Medina-Gómez G. PPARs and Metabolic Disorders Associated with Challenged Adipose Tissue Plasticity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(7). [CrossRef]

- Sun C, Mao S, Chen S, Zhang W, Liu C. PPARs-Orchestrated Metabolic Homeostasis in the Adipose Tissue. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(16). [CrossRef]

- Yu L, Gao Y, Aaron N, Qiang L. A glimpse of the connection between PPARγ and macrophage. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Daniel B, Nagy G, Czimmerer Z, Horvath A, Hammers DW, Cuaranta-Monroy I, et al. The nuclear receptor PPARg controls progressive macrophage polarization as a ligand-insensitive epigenomic ratchet of transcriptional memory. Immunity. 2018;49(4): 615. [CrossRef]

- Kleiboeker B, Lodhi IJ. Peroxisomal regulation of energy homeostasis: Effect on obesity and related metabolic disorders. Molecular Metabolism. 2022;65: 101577. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Zhang J, Cui W, Silverstein RL. CD36, a signaling receptor and fatty acid transporter that regulates immune cell metabolism and fate. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2022;219(6). [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Liu G, Li Y, Pan Y. Metabolic Reprogramming Induces Macrophage Polarization in the Tumor Microenvironment. Frontiers in Immunology. 2022;13. [CrossRef]

- Lee PL, Jung SM, Guertin DA. The Complex Roles of mTOR in Adipocytes and Beyond. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 2017;28(5): 319. [CrossRef]

- Blanchard PG, Festuccia WT, Houde VP, St-Pierre P, BrÛlé S, Turcotte V, et al. Major involvement of mTOR in the PPARγ-induced stimulation of adipose tissue lipid uptake and fat accretion. Journal of Lipid Research. 2012;53(6): 1117. [CrossRef]

- Cai H, Dong LQ, Liu F. Recent Advances in Adipose mTOR Signaling and Function: Therapeutic Prospects. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2016;37(4): 303. [CrossRef]

- Mao Z, Zhang W. Role of mTOR in Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, Vol. 19, Page 2043. 2018;19(7): 2043. [CrossRef]

- Hao K, Wang J, Yu H, Chen L, Zeng W, Wang Z, et al. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ Regulates Lipid Metabolism in Sheep Trophoblast Cells through mTOR Pathway-Mediated Autophagy. PPAR Research. 2023;2023(1): 6422804. [CrossRef]

- Kang S, Nakanishi Y, Kioi Y, Okuzaki D, Kimura T, Takamatsu H, et al. Semaphorin 6D reverse signaling controls macrophage lipid metabolism and anti-inflammatory polarization. Nature immunology. 2018;19(6): 561–570. [CrossRef]

- Wagner W, Ochman B, Wagner W. Semaphorin 6 Family—An Important However, Overlooked Group of Signaling Proteins Involved in Cancerogenesis. Cancers 2023, Vol. 15, Page 5536. 2023;15(23): 5536. [CrossRef]

- Luan D, Dadpey B, Zaid J, Bridge-Comer PE, Deluca JH, Xia W, et al. Adipocyte-Secreted IL-6 Sensitizes Macrophages to IL-4 Signaling. Diabetes. 2023;72(3): 367–374. [CrossRef]

- Lei X, Qiu S, Yang G, Wu Q. Adiponectin and metabolic cardiovascular diseases: Therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Genes & Diseases. 2023;10(4): 1525. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Rosa SC, Liu M, Sweeney G. Adiponectin Synthesis, Secretion and Extravasation from Circulation to Interstitial Space. Physiology. 2021;36(3): 134. [CrossRef]

- Holland WL, Xia JY, Johnson JA, Sun K, Pearson MJ, Sharma AX, et al. Inducible overexpression of adiponectin receptors highlight the roles of adiponectin-induced ceramidase signaling in lipid and glucose homeostasis. Molecular Metabolism. 2017;6(3): 267–275. [CrossRef]

- Ohashi K, Parker JL, Ouchi N, Higuchi A, Vita JA, Gokce N, et al. Adiponectin Promotes Macrophage Polarization toward an Anti-inflammatory Phenotype. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(9): 6153. [CrossRef]

- Salvator H, Grassin-Delyle S, Brollo M, Couderc LJ, Abrial C, Victoni T, et al. Adiponectin Inhibits the Production of TNF-α, IL-6 and Chemokines by Human Lung Macrophages. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2021;12: 718929. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Aldridge J, Vasileiadis GK, Edebo H, Ekwall AKH, Lundell AC, et al. Recombinant Adiponectin Induces the Production of Pro-Inflammatory Chemokines and Cytokines in Circulating Mononuclear Cells and Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes From Non-Inflamed Subjects. Frontiers in Immunology. 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Han Y, Sun Q, Chen W, Gao Y, Ye J, Chen Y, et al. New advances of adiponectin in regulating obesity and related metabolic syndromes. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis. 2024;14(5): 100913. [CrossRef]

- Wen D, Qiao P, Wang L. Circulating microRNA-223 as a potential biomarker for obesity. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice. 2015;9(4): 398–404. [CrossRef]

- Jiao P, Wang XP, Luoreng ZM, Yang J, Jia L, Ma Y, et al. miR-223: An Effective Regulator of Immune Cell Differentiation and Inflammation. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2021;17(9): 2308. [CrossRef]

- Gu J, Xu H, Chen Y, Li N, Hou X. MiR-223 as a Regulator and Therapeutic Target in Liver Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology. 2022;13: 860661. [CrossRef]

- Ying W, Tseng A, Chang RCA, Morin A, Brehm T, Triff K, et al. MicroRNA-223 is a crucial mediator of PPARγ-regulated alternative macrophage activation. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015;125(11): 4149. [CrossRef]

- Muir LA, Kiridena S, Griffin C, DelProposto JB, Geletka L, Martinez-Santibañez G, et al. Rapid adipose tissue expansion triggers unique proliferation and lipid accumulation profiles in adipose tissue macrophages. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2018;103(4): 615. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki T, Gao J, Ishigaki Y, Kondo K, Sawada S, Izumi T, et al. ER Stress Protein CHOP Mediates Insulin Resistance by Modulating Adipose Tissue Macrophage Polarity. Cell reports. 2017;18(8): 2045–2057. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Bulnes P, Saiz ML, López-Larrea C, Rodríguez RM. Crosstalk Between Hypoxia and ER Stress Response: A Key Regulator of Macrophage Polarization. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019;10: 2951. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Zhao R peng, Song X yu, Wu W fu. Targeting ERβ in Macrophage Reduces Crown-like Structures in Adipose Tissue by Inhibiting Osteopontin and HIF-1α. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1). [CrossRef]

- Hill DA, Lim HW, Kim YH, Ho WY, Foong YH, Nelson VL, et al. Distinct macrophage populations direct inflammatory versus physiological changes in adipose tissue. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2018;115(22): E5096–E5105. [CrossRef]

- Li RY, Qin Q, Yang HC, Wang YY, Mi YX, Yin YS, et al. TREM2 in the pathogenesis of AD: a lipid metabolism regulator and potential metabolic therapeutic target. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2022;17(1). [CrossRef]

- Jaitin DA, Adlung L, Thaiss CA, Weiner A, Li B, Descamps H, et al. Lipid-Associated Macrophages Control Metabolic Homeostasis in a Trem2-Dependent Manner. Cell. 2019;178(3): 686-698.e14. [CrossRef]

- Sharif O, Brunner JS, Korosec A, Martins R, Jais A, Snijder B, et al. Beneficial Metabolic Effects of TREM2 in Obesity Are Uncoupled From Its Expression on Macrophages. Diabetes. 2021;70(9): 2042. [CrossRef]

- Xu R, Vujić N, Bianco V, Reinisch I, Kratky D, Krstic J, et al. Lipid-associated macrophages between aggravation and alleviation of metabolic diseases. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2024;0(0). [CrossRef]

- Marinelli S, Basilico B, Marrone MC, Ragozzino D. Microglia-neuron crosstalk: Signaling mechanism and control of synaptic transmission. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2019;94: 138–151. [CrossRef]

- Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116(7): 1793–1801. [CrossRef]

- Van Gaal LF, Mertens IL, De Block CE. Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2006;444(7121): 875–880. [CrossRef]

- Tilg H, Moschen AR. Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 2010;52(5): 1836–1846. [CrossRef]

- Wernstedt Asterholm I, Tao C, Morley TS, Wang QA, Delgado-Lopez F, Wang Z V., et al. Adipocyte Inflammation Is Essential for Healthy Adipose Tissue Expansion and Remodeling. Cell Metabolism. 2014;20(1): 103–118. [CrossRef]

- Wu H, Ballantyne CM. Metabolic Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Obesity. Circulation Research. 2020;126(11): 1549–1564. [CrossRef]

- Semenza GL. The Hypoxic Tumor Microenvironment: A Driving Force for Breast Cancer Progression. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2016;1863(3): 382. [CrossRef]

| Phenotype | Stimuli | Surface markers | Expressed mediators | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | LPS IFNγ TNFα RNS/ROS |

CD80, CD86, TLR2, TLR4, HLA-DR, IFNγR | TNFα, IL-1βhigh, IL-6, IL-12high, IL-1α, IL-23, IL-18, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, CCL5, CCR7, CXCL16, GM-CSF Arg-2, iNOS |

Pro-inflammatory Th1 response Anti-tumor capacity |

[2,20,21] |

| M2a | IL-4, IL-13 | CD163, CD206, Arg-1 | IL-10, TGFβ, CCL17, CCL24, CSF-1 |

Anti-inflammatory Tissue remodeling |

[15,35] |

| M2b | IL-1β, TLR ligands, immune complex | CD86 | TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6 IL-10, CCL1 |

Th2 activation, Pro- and anti-inflammatory Immunoregulation |

[15,36] |

| M2c | Glucocorticoids, IL-10, TGFβ | CD206, CD163 Arg-1 |

IL-10, CCL18, CXCL13, TGFβ, CCL16 |

Anti-inflammatory Phagocytic and apoptotic capacity |

[35,37] |

| M2d | IL-6, adenosine receptor ligands, TLR ligands | VEGF, ILT3R |

IL-10, CCL18, CCL22, VEGF |

Pro- and anti-inflammatory Angiogenesis, Immunosuppressive Tumor progression |

[20,29] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).