Cattle are one of the most widespread and economically important domesticated animals globally. Beyond their productivity, cows communicate a wide range of emotional and physiological states through their vocalizations. These vocal signals can range from low-pitched murmurs indicating social bonding to high-pitched, urgent calls signaling distress, hunger, or pain. In the high-noise environment of modern farms, such signals are often overlooked or misinterpreted. Yet listening carefully to these vocal cues is not a curiosity—it is central to early detection of welfare issues. A subtle change in the rhythm of a calf’s call, for instance, might indicate illness before other clinical signs appear. Decoding cattle vocalizations introduces a powerful, underutilized dimension to livestock management. As animal welfare gains attention in both scientific and public discourse, farmers, veterinarians, and ethologists increasingly recognize the practical and ethical necessity of listening more closely to the animals in their care.

Recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and Natural Language Processing (NLP), are unlocking new possibilities for interpreting animal vocalizations. Once restricted to human-centric tasks like speech recognition and translation, these technologies are now being adapted to interpret the vocal repertoire of cows. By transforming acoustic signals into structured data—and eventually into meaningful, actionable insights—AI is poised to revolutionize traditional livestock management. For example, AI systems under development can detect heat stress based on subtle modulations in the pitch and tempo of moos. When paired with other sensor data, such as body temperature, location, and behavior, these insights become more robust. In essence, AI can serve as an additional caretaker—always listening, always analyzing. This vision fits within the broader momentum of smart farming, but achieving it demands more than computational horsepower. It requires careful attention to the contextual nuances of cattle communication, and strong safeguards against human biases, especially the tendency to project anthropomorphic interpretations onto animal sounds.

In reality, cattle farms differ dramatically in layout, management style, and breed composition. What constitutes a normal or benign call on one farm may be interpreted as a distress signal on another. Complicating matters further, there is currently no standardized lexicon or “dictionary” that definitively links specific call types to emotional or physiological states. Therefore, to train AI models, researchers must manually annotate audio recordings with observed behavior, context, and environmental factors—a labor-intensive process. This lack of large, annotated datasets remains one of the most significant bottlenecks in the field. Traditional acoustic analysis methods, which involve generating spectrograms and manually extracting features like frequency and duration, are informative but not scalable to the volumes needed for robust AI training. Ethical concerns add another layer of complexity. While AI offers the potential to deepen empathy for animals, it also raises the risk of overreliance on systems that may lack transparency or contextual awareness. For these technologies to be used responsibly, AI models must generalize across different herds, environments, and recording setups, and they must do so without falling back on simplistic or reductive analogies to human speech.

Despite these challenges, early research in this field has produced promising results. Initial studies focused on the acoustic structure of cattle calls and demonstrated that vocalizations are not random but are closely tied to specific biological and behavioral contexts. Classical ML methods such as support vector machines (SVMs), decision trees, and random forests have been employed to classify vocalizations based on acoustic features, with moderate success in distinguishing between call types like estrus, distress, or feeding anticipation. These models helped establish that vocal signals reliably encode useful information about the animal’s internal state. More recent work has leveraged deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which can learn discriminative features directly from raw audio data or spectrogram images. CNNs have shown high accuracy in classifying vocalizations without the need for hand-crafted features. Meanwhile, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and transformer models have improved the temporal modeling of call sequences, enabling systems to interpret vocal changes that evolve over time. Although no current system offers a full “translation” of cow vocalizations into human language, these approaches are systematically mapping call patterns to behavioral meaning. Techniques borrowed from NLP—such as transfer learning and data augmentation—are increasingly used to compensate for the limited availability of labeled cattle audio, pointing toward a future where AI systems can bridge the communication gap between cows and humans.

This review article presents a critical synthesis of developments in bovine bioacoustics, focusing on how AI methods—from traditional signal processing to modern large language models—are being used to decode cow vocalizations.

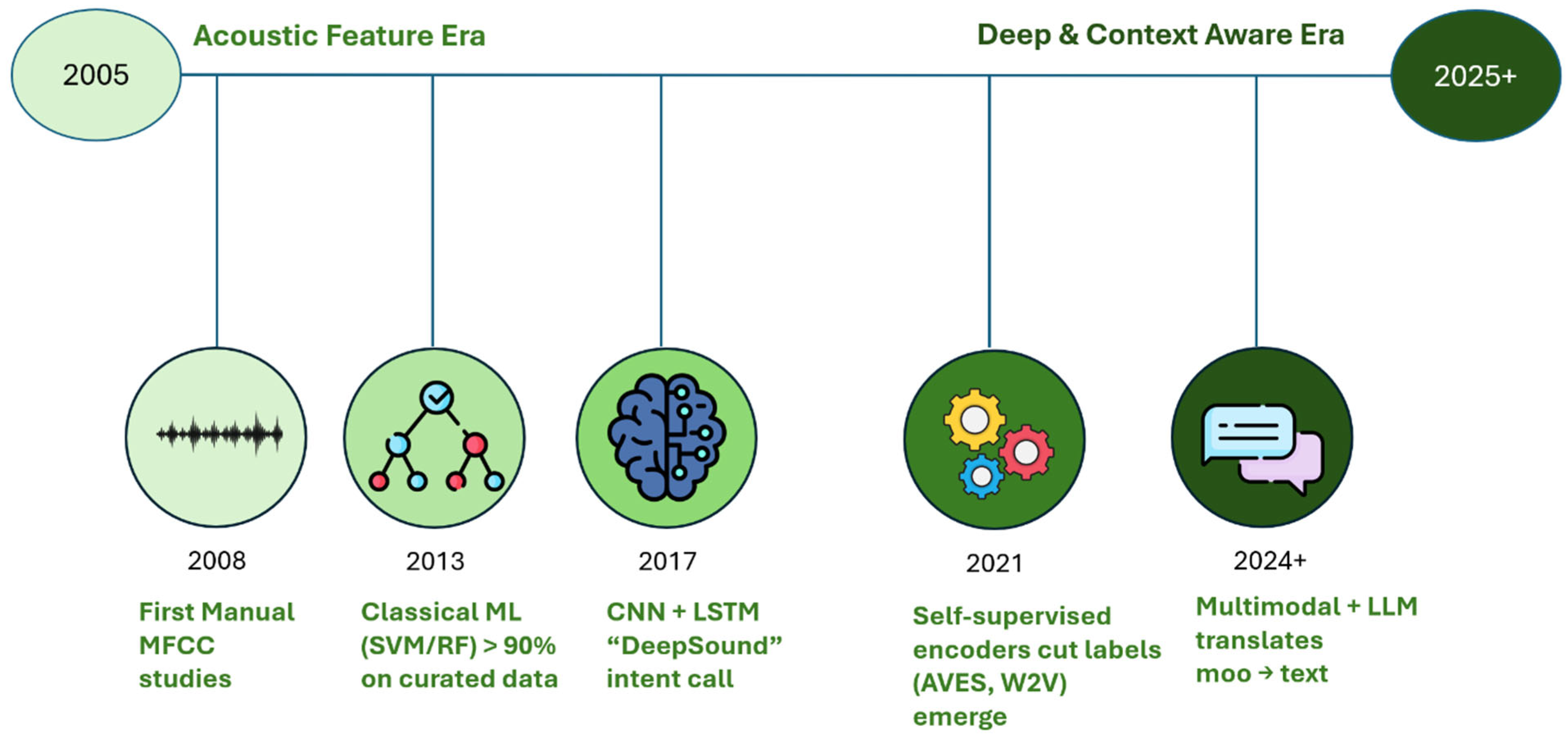

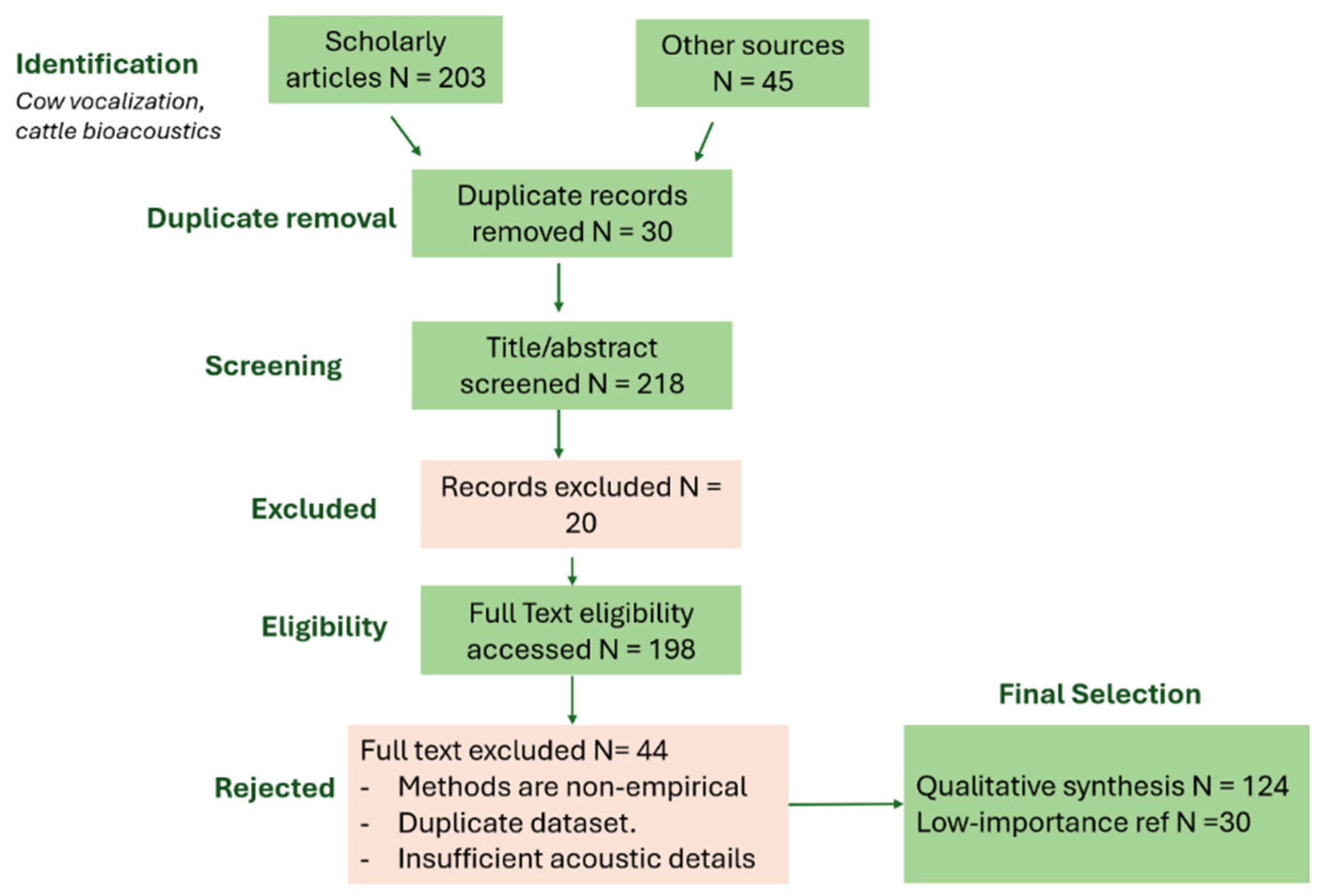

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the field, showing how research has transitioned from manual spectrogram inspection to edge-deployable, multimodal AI systems. We conducted a systematic literature review using the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Page et al., 2020), querying multiple databases including Web of Science, Scopus, and IEEE Xplore for studies published between 2020 and mid-2025. Search terms included combinations of "cattle vocalizations", "bovine acoustic analysis", "machine learning", "deep learning", and "bioacoustics". We also performed reference chaining via Google Scholar to ensure coverage of foundational and emerging work. After removing duplicates and screening for relevance, 124 peer-reviewed studies were selected for full-text review based on criteria that included methodological rigor, relevance to animal welfare, and empirical validation. Commentary articles, non-English publications, and papers not involving cattle were excluded. The resulting corpus represents the state of the art in AI-driven cattle vocalization research.

Figure 2 provides a PRISMA diagram detailing our literature screening process.

This review is structured into five major sections. First, we examine the biological and behavioral foundations of cattle vocalizations, exploring the contexts in which different types of calls are produced and how they relate to animal welfare. Second, we outline the progression of analytical techniques used to study these calls, tracing the evolution from manual spectral analysis and classical supervised learning to more recent deep learning frameworks. Third, we delve into the application of NLP and large language models, highlighting how these tools are being creatively applied to derive meaning from non-human vocalizations. Fourth, we discuss the practical applications of sound-based systems for health and welfare monitoring in farm settings, with a focus on early detection, real-time alerts, and integration into precision livestock farming systems. Finally, we identify key research gaps, including the need for standardized datasets, cross-farm validation, and improved model interpretability, and we propose a roadmap for addressing these challenges.

For farmers, the ability to accurately interpret cattle vocalizations could mark a turning point in livestock care. Earlier detection of illness or stress, reduced dependence on reactive veterinary interventions, and better alignment of feeding and breeding schedules are just a few of the practical benefits. Each step toward building systems that can reliably decode animal signals adds to the growing toolkit of smart farming. This review seeks not only to present a technical overview but also to contextualize these advancements within the lived realities of farm animals and the humans who care for them. Ultimately, the goal is not simply to build machines that decode moos, but to create systems that listen with precision, act with empathy, and improve the lives of animals in meaningful, measurable ways.

Deciphering the Complexity of Bovine Communication

This section discusses how cattle vocal patterns encode biologically meaningful information and the methodological foundations supporting their interpretation.

Biological and Behavioral Significance of Cattle Vocalizations

Understanding cattle vocalizations requires integrating biological, ethological, and acoustic perspectives. Cows are highly social and gregarious animals, and their vocal signals carry rich information about identity, context, and emotional state. As Watts and Stookey noted, vocal behavior in cattle can be viewed as a “subjective commentary” on the animal’s internal condition, with calls conveying age, sex, dominance and reproductive status (Watts and Jon M, 2000) (Jung et al., 2021). For example, calves emit distinct calls to initiate suckling, whereas adult cows use low-frequency “murmurs” for close contact interactions and louder high-frequency bellows when alarmed or separated from the herd. (Padilla De La Torre et al., 2015). Cow’s salivary cortisol levels spiked roughly two-fold in more stressful scenarios as compared to non-harmful states. This is paired along with intensified calling, indicating that vocalizations are often accompanied by physiological signs (Yoshihara et al., 2021). Generally, cow uses low and gentle calls to maintain maternal bonding with their calves. Postpartum dairy cows vocalize in structured way around nursing and calving time to synchronize with the newborns. On the other hand, when mothers and calves are reunited after period of separation, there is a change in their vocal exchange (Green and Alexandra C, 2021).

Table 1 lists the main call types alongside their usual frequency range, duration and welfare meaning. Vocalizations are strongly linked to welfare like pain, fear, or frustration typically elicit more intense and frequent calls. On the other hand, positive or low-arousal states (e.g. content grazing or rumination) produce quieter, lower-frequency murmurs (Watts and Jon M, 2000) (Meen et al., 2015). Farmers and ethologists have documented cattle modulating vocal signals during estrus and forming social hierarchy or contact with herd mates. Importantly, not all “moos” are similar. Their acoustic structure carries a significant meaning. It is observed that cattle produce at least two broad types of calls that differs in features and context. One type is low-frequency call emitted with a closed or partially open mouth. This are relatively quiet, short distance signals. In contrast, the second type is open mouth call having louder and higher fre-quency. These are generally used for long distance communication or in urgent situation. Open mouth calls tend to occur when a cow is excited, distressed or contacting farther away (Röttgen et al., 2020). It is observed that in intense situations like parturition (calving) cows increased their number of open mouth vocalizations, whereas during less urgent calf separation they showed more closed mouth or partially opened calls (Green et al., 2020). This indicates that mouth posture and resulting acoustic variation are not random. Indeed, recent work shows that cows produce uniquely individualized contact calls carrying information on calf age (but not sex) (Padilla De La Torre et al., 2015), and that separation or handling (e.g. ear-tagging) significantly alters call structure (Schnaider et al., 2022) (Gavojdian et al., 2024). Across breeds and environments, the basic pattern of contact versus distress calls appears conserved, but there is also inter-population variation. For example, most studies involve European Bos taurus cattle in temperate systems, while Bos indicus or tropical breeds may have different vocal tract morphologies and auditory sensitivities (e.g. zebu cattle are known to be more reactive to both low and high frequencies (Gavojdian et al., 2024) (Jung et al., 2021)). Likewise, acoustic profiles differ between open-range and barn environments due to noise and social context. In short, cattle vocalizations are multifunctional signals shaped by evolution and husbandry. They enable mother–offspring bonding, herd cohesion, estrus advertisement, and alarm calls, and they reflect the animal’s physiological state and well-being (Watts and Jon M, 2000).

Taken together, the biological significance of bovine calls is clear: they evolved signals of social and emotional state. However, there remain gaps. Most research focuses on adult cows and calves in specific systems (dairy vs. beef, indoor vs. pasture). Relatively little is known about vocal variation across diverse breeds, climates, and management conditions. Moreover, while calls clearly increase under stress (e.g. during isolation or handling (Watts and Jon M, 2000) (Schnaider et al., 2022)), the exact acoustic markers of pain versus other negative states can overlap. Future research must critically examine how genetic background, age, sex, and environment modulate vocal behavior. In essence, the ground work from behavioural studies has established “what” cattle says, the next step is figuring out “how” to consistently capture and decode those signals across various conditions. Let’s look more into different traditional approaches used for interpretating cattle vocalizations.

Traditional Approaches: The Foundations of Vocalization Research

Early studies of bovine acoustics relied on behavioral observation and basic audio analysis. Researchers compiled ethograms correlating call types with contexts such as feeding, mating, calf contact, or handling. Researchers are engaged in field observations like watching cows and calves in various scenarios. They manually noted when and how the cow vocalized. These foundational approaches involved manual annotation of calls (e.g. “bellow,” “grunt,” “moo”) and simple spectral measurements, often with custom built recording setups. These studies correlate the vocalization to specific events or management practices. Watts and Stookey (2000) review these methods, emphasizing that even before advanced technology, ethnological observations revealed consistent patterns in cattle vocal behavior (Watts and Jon M, 2000). For example, Kiley (1972) first categorized six distinct cattle call types in mixed herds, noting combinations of syllables linked to different social situations (Jung et al., 2021).

Along with direct observations, researchers started using technological equipments like audio recorders to document vocalizations for manual spectrographic analysis. They even used simple sensors for continuous monitoring. Observers noted that oestrous cows emit characteristic calls, calves emit “ma-ma” contact calls, and pain or fear elicit intense bellows (Jung et al., 2021). An acoustic monitoring system was used to continuously record the soundscape to detect abnormal levels in vocalizations (Alsina-Pagès et al., 2021). This approach highlights that it was feasible to collect raw data automatically on farm. But it has some technical limitations like system could record only for short periods and struggled with background noise. Early recordings (using tape recorders and spectrum analysers) quantified basic parameters like fundamental frequency and duration for these call types. Such studies confirmed that cattle vocalizations can encode age and physiological stress (Watts and Jon M, 2000) (Jung et al., 2021). The strength of these traditional methods lay in their ecological validity. Calls were labelled in original place, tying acoustic phenomena to rich context. Wearable devices like collar mounted microphones on grazing cows captured vocal events real time proving that vocalizations can be automatically detected to some extend in complex farm environment (Shorten et al., 2024).

However, traditional approaches have limitations. They were labor intensive and often subjective, classification relied on human judgment (e.g in (Johnsen et al., 2024) observers knew which calves were subject to which weaning treatment) and coarse categories. Without automated tools, quantification was limited to a few parameters, and call libraries were small. Moreover, early ethograms did not fully capture the multidimensional nature of sound (e.g. formant structures, harmonics).

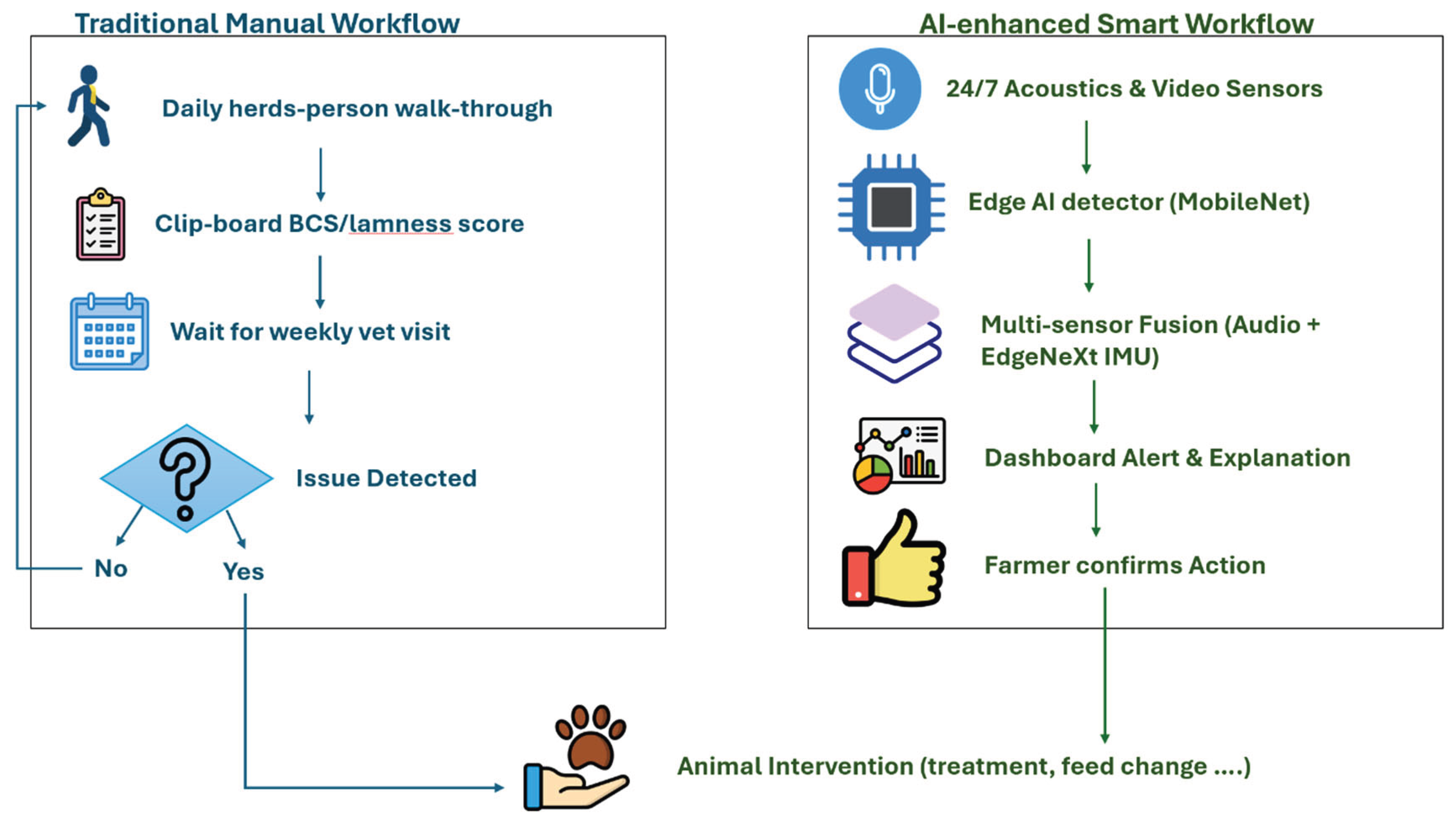

Figure 3 contrasts the old ‘clipboard-and-stopwatch’ workflow with today’s sensor first loop, highlighting why automation matters. Critically, comparisons across studies were difficult because of varying methods and terminologies. Still, the legacy of these methods is significant, they established the lexicon of cattle vocal communication and provided initial evidence that vocal behavior reflects biological state (Watts and Jon M, 2000). This historical record forms a baseline for modern quantitative analysis. The foundational call catalogues (e.g. by Kiley, Watts) remain essential, but modern research must reinterpret them with quantitative tools.

Acoustic Decomposition of Bovine Vocalizations

Contemporary analysis dissects cattle calls into detailed acoustic parameters. For cattle vocalizations, commonly measured acoustic parameters includes fundamental frequency F0, the range and variation of frequencies (including high harmonics and formants), the duration and temporal pattern of the call and the amplitude or loudness profile. By plotting the calls on spectrograms, we can visually inspect these characteristics and identify patterns that might not be recognized by human ear. Signal processing techniques like Fourier analysis and Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) are used to generate these spectrograms and calculate the frequency domains. F0 is a primary metric, it relates to the source (vocal fold vibration) and often correlates with arousal or call intensity. For example, Padilla De La Torre et al., 2015 found LFCs with mean F0 ≈81 Hz and HFCs ≈153 Hz, reflecting tension in the sound source. Other time domain measures include call duration, amplitude envelope, and call rate. Temporal patterns (e.g. repetition rate of moos) also encode information (e.g. frantic short calls during pain vs. long low calls in estrus).

In the frequency domain, researchers extract spectral features. Formant frequencies (resonances shaped by the vocal tract) can signal age or size: adults have lower formants than calves (Padilla De La Torre et al., 2015). Spectral energy distribution (e.g. spectral centroid, bandwidth) can differentiate call types (bellows are broad band, while murmurs are narrow). A powerful set of features comes from cepstral analysis, MFCCs and related cepstral descriptors capture the timbre of calls. These are now standard inputs for machine learning models. For instance, Jung et al., 2021 combined MFCCs with a convolutional neural network, achieving ~91% accuracy in cattle call classification.

Table 1 summarizes detailed acoustic profiles of various bovine vocalization types, correlating physical acoustic parameters with specific behavioral and welfare implications. Cattle vocalizations occupy distinct frequency bands and patterns as compared to other sounds like the whirr of a machine or a bird chirp. This makes it possible to algorithmically detect cow calls from the noise. By comparing time domain waveforms and frequency spectra we can filter out non cattle sounds and isolate the cow calls (Özmen et al., 2022).

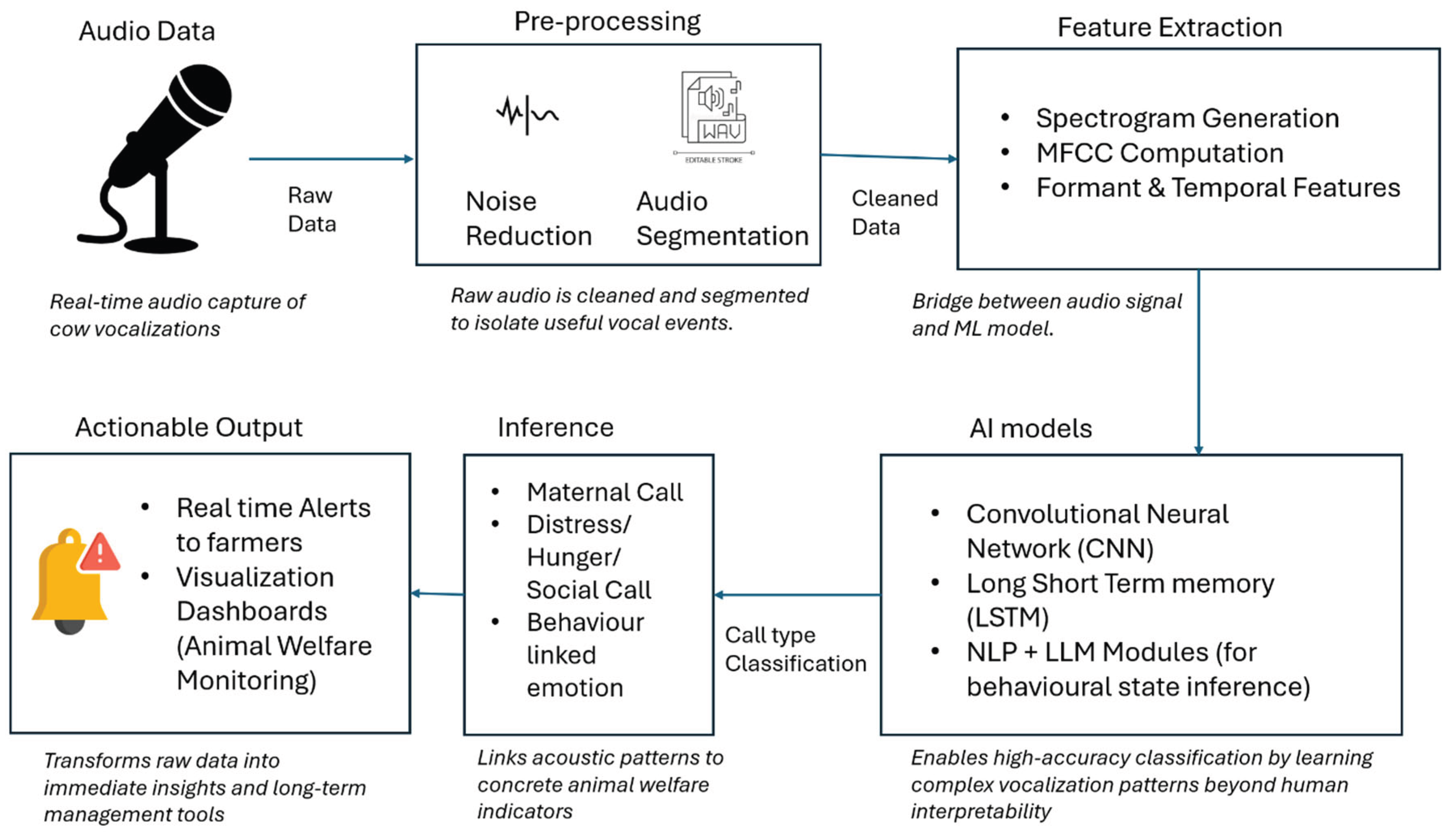

In practice, decomposition often uses tools like spectrograms and glottal flow es-timations. Modern software (e.g. Praat, Raven) computes these parameters efficiently. Yet interpretation requires care, acoustic features are influenced by factors like head posture, background noise, and recording equipment. Comparative studies have shown, that pain vocalizations tend to have higher F0 and more chaotic spectra than calm calls (Schnaider et al., 2022). Moreover, cross validating features against physiology is critical. For instance, Sharp changes in pitch or amplitude during handling correlate with elevated cortisol. The raw to alert journey sketched later in

Figure 4 starts with the very spectrogram slices we describe here.

Ultimately, acoustic analysis provides a quantitative “fingerprint” of each call. When linked with behavior, it allows calls to be labelled as “distress” or “content” with statistical confidence. However, there is no single acoustic marker of welfare, rather, patterns across multiple parameters are informative. For example, a low F0, long duration “murmur” might indicate relaxed ruminating, whereas a high F0, broadband roar signals acute stress (Meen et al., 2015) (Padilla De La Torre et al., 2015). Integrating these signals through algorithms and classifiers can automate interpretation.

Yet purely acoustic studies have its own limitations. We can say that a particular cow call might measure a high pitch and certain duration, acoustic analysis might fit this call to either estrus or mild distress call. Without having contextual information, distinguishing between these two calls becomes difficult. While advanced feature extraction like using a using a broad spectrum of MFCCs or nonlinear acoustics to detect softness improves detection and classification. But it became clearer and explainable when the context is applied.

Breed and Environment Acoustic Variation

Both breed and environment significantly influence the acoustics of cattle vocalizations. Genetic differences between breeds (e.g. Bos indicus vs. Bos taurus) can lead to shifts in call frequency, structure, and clarity. For instance, Bos indicus (zebu) cattle have been found more reactive to very low and high frequency sounds than Bos taurus, a difference attributed to their distinct ear anatomy and hearing sensitivity (Moreira et al., 2023). Such anatomical variation (including vocal tract length and auricle shape) may translate into subtle differences in vocal outputs for e.g. potential formant frequency shifts or different F0 ranges across breeds (Burnham, 2023). Indeed, vocalizations of larger or anatomically different breeds often exhibit lower resonant frequencies (formants) than those of smaller breeds or related species. Comparative studies support this, the mean pitch of calls by water buffalo cows was shown to differ significantly from that of European grey cattle, highlighting how genetics impact vocal frequency (p < 10^−13) (Lenner et al., 2025). However, not all breed effects are large, individual variation can sometimes outweigh breed averages (Lenner et al., 2025), so robust models must account for intra as well as inter-breed variability.

Environmental context further modulates call acoustics. An indoor barn vs. an open pasture presents very different sound propagation conditions. In reverberant enclosed spaces like barns, low frequency, narrow band calls can resonate and carry further (echoing off walls), whereas higher frequency elements may become attenuated or blurred (Burnham, 2023). The Acoustic Adaptation Hypothesis (AAH) suggests that animals adjust their call structure to the habitat, calls in “closed” environments (forests or barns) tend to use lower frequencies or prolonged tonal elements to maximize transmission, while calls in open environments can afford higher frequencies and rapid frequency modulation (Burnham, 2023). Cattle are no exception a call recorded in a concrete barn may have a muddier sound (longer decay, overlapping echoes) compared to the same call outdoors. Studies have had to consider such factors when generalizing models, like analysis by Gavojdian et al., 2024 noted that prior datasets included vocalizations from both pasture mobs and barn settings. The farm environment can thus introduce acoustic distortion (e.g. reverberation, background machinery noise) that affects call clarity and measured features. This impacts cross-farm generalization, a classifier trained on clean pasture recordings might falter on barn recordings (and vice versa) if not designed with noise robust features. Addressing breed and environment variation e.g. by normalizing for formant differences and augmenting data with reverberation effects is crucial for developing models that perform reliably across herds and farms (Gavojdian et al., 2024) (Burnham, 2023).

Integrating Multimodal Data: Contextualizing Vocalizations

As seen in the limitations of acoustic analysis, it improves the ability to detect and characterize cattle vocalizations understanding the meaning of these sounds requires additional context. Consequently, recent research has made towards multimodal data integration combining vocalization data with other sources of information. A cow’s vocal behaviour does not occur just in isolation, but it is linked with her physical actions, physiological state, and the surrounding environment. The semiotic repertoire concept suggests that the cattle communicate through multiple channels (like auditory, visual, olfactory) (Cornips, 2024). And these signals together convey the animal’s intent and condition. For example, a cow might bellow loudly and pace restlessly when separated from her calf. This indicates distress, but the addition of her movement pattern confirms the level of agitation. On the contrary, a cow might vocalize with a similar sounding call in two different situations when she is alone, or she is in crowded pen at feeding time. Thus, only by noting the context we can interpret the call correctly.

Modern precision livestock systems therefore combine vocal data with other sensors. For instance, video cameras or 3D tracking provide information on posture and social context, accelerometers reveal activities (grazing, walking, lying), environmental sensors record temperature or humidity, while health monitors track physiology. By synchronizing these modalities, we can interpret calls more accurately. For example, an open mouth call recorded while a cow is isolated from the herd (monitored by positioning sensors) is more likely distress than if the cow were simply feeding and grazing. A study on multimodal datasets (MMCOWS) illustrates this approach, it collected synchronized audio, inertial (motion), location (UWB), temperature, and video data from dairy cows, yielding millions of annotated observations (Vu et al., 2024). Such datasets enable algorithms to cross-validate vocal cues, if audio detects a call, the system checks cameras and accelerometers to confirm whether the animal is running (panic) or ruminating quietly.

Research has begun to exploit these synergies. Wearable collars combining mi-crophones and accelerometers can, for example, distinguish coughs from calls by correlating sound with breathing motions. Farms increasingly deploy acoustic sensors alongside cameras in barns to flag abnormal behavior, a cow calling persistently at the water trough (audio) while isolated (camera) can prompt an alert. These multimodal systems tend to improve classification accuracy. In pilot by Wang et al., 2023, combining audio with ear tag RFID data and motion sensors allowed machine learning models to identify feeding versus social vocalizations with far higher precision than audio alone. For instance, a dual channel audio recorder attached to a cow can capture sound from two microphones simultaneously (one oriented toward the cow’s throat and other to the environment) allowing software to differentiate the cow’s own vocalizations from background noise (). Beyond audio, a complete multimodal system includes video cameras watching the herd, accelerometers on cows measuring their movement, GPS units logging their location, and even physiological sensors (like heart rate or rumen sensors).

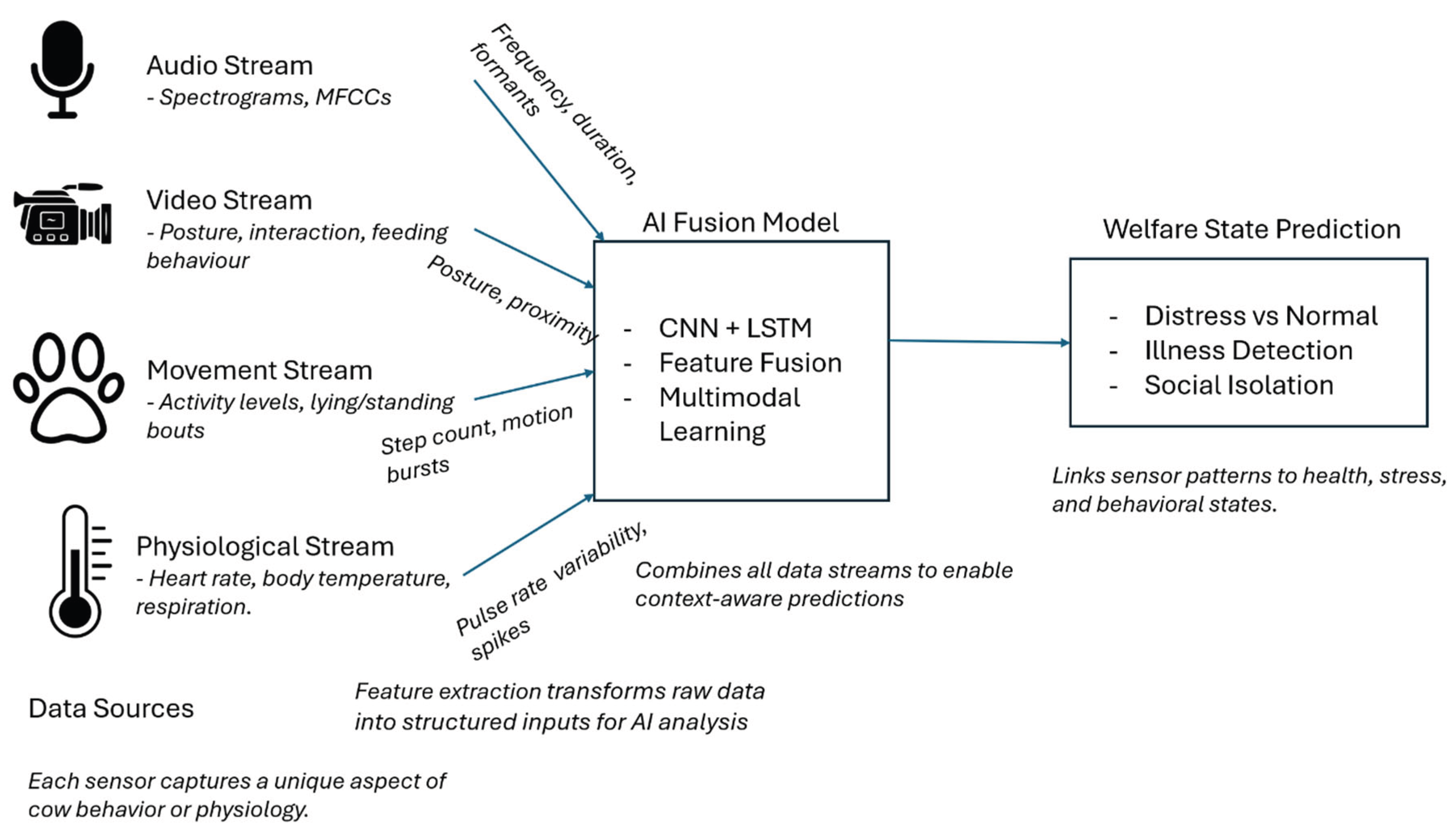

Figure 7 pulls all those data streams together in one schematic, showing how sound, motion and video converge on a single dashboard. Such prototypes have improved the ability for behaviour recognition.

Cattle behaviour classification system used an improved EdgeNeXt, a lightweight edge CNN, to fuse data from multiple inertial sensors, turning motion signals into images for analysis (Peng et al., 2024). It combines images with spectrogram patches, achieving 95 % accuracy in classifying social licking vs. rumination. But incorporation of additional modalities such as video or audio could further enhance model performance.

Table 2 summarises which extra sensors pairs well with barn audio and what each combination can flag in real time. Few studies have fully integrated audio with a wide array of other sensors specifically for decoding cattle calls, which marks a clear direction for future research.

Despite their promise, multimodal approaches present challenges. Challenges include synchronizing data streams (ensuring that the moo and the movement data align in time) and handling the volume and complexity of data that such systems produce, deploying numerous sensors on a farm can be expensive and technically demanding. It is observed that multimodality reduces ambiguity by confirming a vocalization context through other evidence reducing false positives and false negatives. There are also trade offs in farm deployment (cost, data bandwidth). Nonetheless, the trend is clear, to “give cows a digital voice” we must listen not only with microphones but with a network of intelligent sensors.

AI-Driven Analysis of Bovine Vocalizations

Supervised Machine Learning Techniques: Capabilities and Constraints

Models that perform well in one environment “Farm A” may not generalize to other “Farm B” having noise and different acoustic conditions. Traditional classifiers like SVM, k-NN, Naïve Bayes, Random Forest, Hidden Markov Models start with hand designed descriptors (pitch, formants, call duration, energy) and then learn decision boundaries. When those features capture the “essence” of a task, accuracy can be strikingly high. An SVM outperformed all peers in detecting estrus vocalizations (Sharma et al., 2023), and a Random Forest reached ~93 % F1 for predicting metritis from combined vocal behavioural cues (Vidal et al., 2023). k-NN and RF readily separated high arousal open mouthed isolation calls from low-arousal closed-mouthed feeding calls in Japanese Black cattle, peaking at 96 % accuracy (Peng et al., 2023). Even in noisy shed conditions, a collar microphone plus supervised learning still distinguished “any moo” from ambient clatter with > 99 % accuracy (Shorten, 2023). However, these approaches offer a relatively straightforward pipeline (feature extraction followed by classification) that has provided preliminary insights into cow communication capabilities.

Despite these successes, a fundamental challenge is that cow calls are acoustically complex signals that can vary with context, individual, and environment, where simpler models struggle to capture the intricate variability present in cow vocal communication. Moreover, many algorithms perform well only after extensive feature engineering, which requires domain expert knowledge and can be biased. A few averaged MFCCs flatten the evolving frequency contour of a pregnant moan, and HMMs only add temporal context if researchers build extra states. Data are often tiny and homogeneous many studies analyse ≤ 20 animals from one herd which generates overfitting. The SVM that excelled on its home herd (Sharma et al., 2023) stumbled on a second farm with different acoustics, age mix, and management style, confirming worries about brittle performance (Peng et al., 2023) (Vidal et al., 2023). These hand crafted models also show their limits when extra streams join the mix.

Another major constraint is noise. The noise robust foraging detection NRFAR pipeline filtered out machinery buzz and retained 86 % accuracy in moderate noise, but performance slid once tractors backfired or multiple cows overlapped (Martinez-Rau et al., 2025). Class confusion also arises, the RF from (Peng et al., 2023) occasionally mislabelled excited social calls as mild distress because their spectral envelopes overlapped. Without a public benchmark or cross farm validation, gaps repeatedly flagged by researchers, cannot tell whether a reported 95 % is a true breakthrough or a fragment of easy data.

Despite these caveats, supervised models remain valuable:

They are computationally light, suiting edge devices,

Their feature weights or decision trees are interpretable,

And they set baseline expectations for deeper networks.

Hand built features and small datasets let classical ML reach eye catching numbers, yet the moment we change barns, breeds, or background noise, the model performance deteriorates.

Deep-Learning Approaches: Spectrograms, Sequences, and Self-Supervision

Although a neural network may detect subtle sounds beyond human perception, its reliability becomes uncertain in conditions of limited data, high background noise within the barn, and an opaque decision-making process.

Deep learning has transformed bioacoustics by letting models learn directly from raw waveforms or Mel-spectrograms, bypassing hand crafted features. “DeepSound,” a CNN–LSTM stack, extracted such patterns from calf distress calls and reached nearly 80% macro-F1 despite minimal feature engineering (Ferrero et al., 2023). A separate CNN with seven convolutional blocks classified cow “intent” calls (hunger, stress, estrus) at ~ 97 % accuracy (Patil et al., 2024), showing how spectral differences map to different motivational states of the animals.

Event Detection and Edge Deployment

Continuous monitoring needs fast detectors rather than offline classifiers. A lightweight MobileNet (CNN architecture) scanned live barn audio, sliding a 1-s window to flag calls in real time (Vidana-Vila et al., 2023). Tuning segments overlap matters because wide overlaps caught faint calls but doubled false alarms, while narrow overlaps trimmed noise yet missed whispers a practical reminder that sensitivity and alert fatigue trade off. MobileNet’s tiny footprint (< 1.5 M parameters) also fits Raspberry-Pi gateways, resulting into cost-aware edge AI.

Sequence Modelling and Hybrid Architectures

Temporal context matters when a labouring cow’s pitch rises, or a calf emits escalating pleas. Hybrid CNN–LSTM pipelines stitch spectral slices into sequences so the model “listens” rather than “glances.” DeepSound’s CNN–LSTM beat a plain CNN on rare call types (Ferrero et al., 2023); yet, in a separate six class experiment the hybrid under performed a pure CNN because the dataset was too small for recurrent layers to generalise (Jung et al., 2021a). The more complex sequence model needs more data to realize its advantages, thus making LSTMs powerful for handling time-dependent incidents, but their effectiveness is strongly tied to size of training dataset, to learn temporal patterns. The step by step audio pipeline in

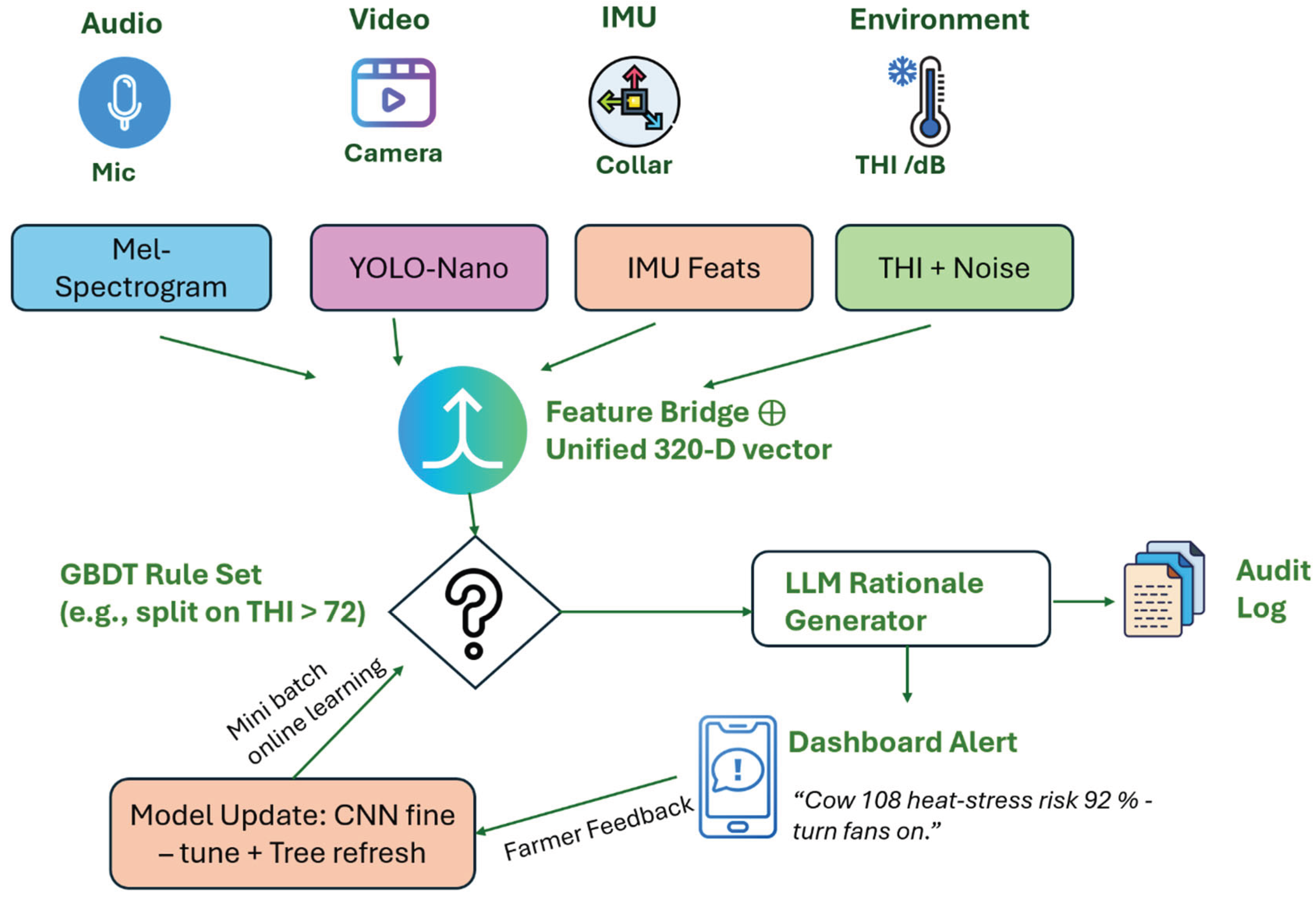

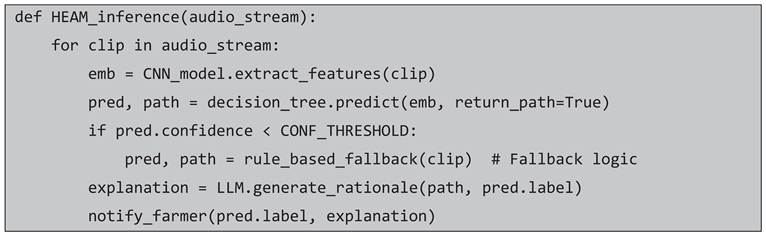

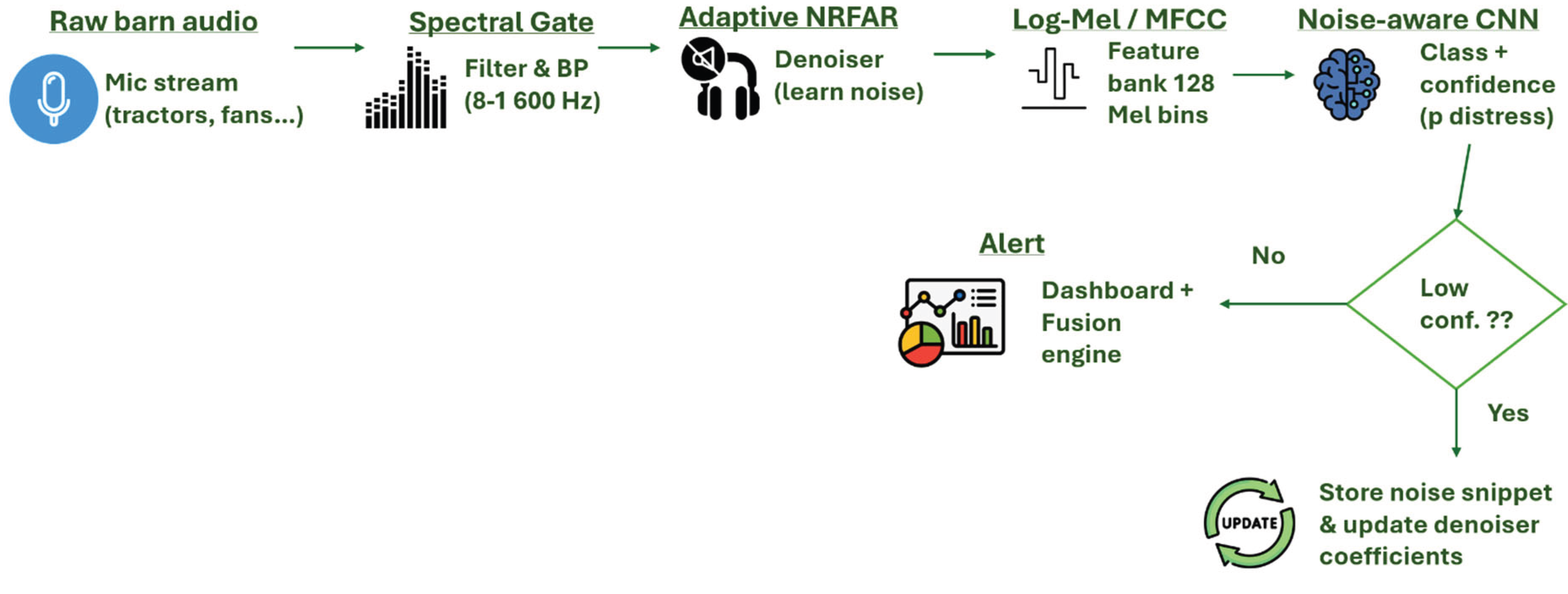

Figure 4 makes it clear how raw moos are cleaned, sliced and classified before an alert pops up.

Self-Supervised and Transfer Learning

Label scarcity is a chronic pain annotating thousands of moos is labour intensive. Self-supervised pre-training (e.g., Wav2Vec style contrastive learning) on unlabelled farm ambience can bootstrap robust embeddings later fine-tuned with just a few dozen labels. A CNN initialised on generic audio and fine-tuned to cow calls jumped to 93.9 % F1 (Bloch et al., 2023), a 6 percentage point boost over training from scratch. The advantage lies in transferring knowledge from broad, unrelated data rather than investing in the creation of another limited, custom dataset. Key performance numbers for every major study are laid out in

Table 3, to compare accuracy.

Beyond Single Modality

Deep models are beginning to fuse audio with accelerometer and video streams. Merging MobileNet’s audio embedding with collar IMU features improved distress detection by ~5 percentage points (Vidana-Vila et al., 2023), and adding thermal camera cues raised heat-stress precision in a multimodal pilot (Lenner et al., 2023). But fusion raises deployment friction, extra sensors mean extra cost and maintenance, a concern farmers cited in usability interviews.

Individual Identification and Spatial Audio

A microphone-array CNN was used to identify which individual cow in a group was vocalizing. The system correctly identified the calling animal with 87% sensitivity in group housing conditions, which would be difficult to achieve in manual feature based methods (Röttgen et al., 2020). These arrays of microphones are expensive and sensitive to barn layout. Also, simpler single-mic localisation remains an open challenge for individual identification.

Thus, Deep networks let us “listen” at spectral and temporal resolutions impossible by hand, but without big, diverse datasets and farmer-friendly explanations, their brilliance risks dying in GPU racks far from the barn.

Evaluating Model Robustness and Practicality

When the acoustic environment of a barn differs from that of the research facility—such as having louder ventilation systems or older stall designs—the performance of a recently developed state-of-the-art model may be compromised, potentially leading to reduced reliability and increased risk of misinterpretation.

Domain Shift: When “One Size” Fits Only One Farm

Most AI papers still train and test on a single herd. Models trained on one farm often do not perform as well on another due to differences in herd vocal behavior, barn acoustics, and background noises. In the real time the call detector from Paper (Vidana-Vila et al., 2023), F1 scored 0.94 on its home farm but fell below 0.70 on the next site, where concrete walls added longer reverberation tails. Similar cross-farm drops have been reported for estrus (Peng et al., 2023) and stress-call classifiers (Martinez-Rau and Luciano S, 2022). This suggests that models may be “tuned” to traits in the training data, such as the echo characteristics of a particular barn or the specific noise from that farm’s machinery and thus lack robustness when those specifics changes. Many researchers taken efforts to create standardized benchmarks for examples, the BEANS benchmark has aggregated animal sound datasets to evaluate models across species (Hagiwara et al., 2022), but still cattle specific benchmarks are limited.

Table 4 cross checks classic ML and deep learning models side-by-side, making their trade-offs transparent.

Class Imbalance Impact

Class imbalance is a prevalent challenge in cow vocalization datasets, as everyday “normal” calls vastly outnumber rare distress or emergency vocalizations. In typical recordings, cows produce many routine moos (or other low-arousal calls) but only occasional pain, hunger, or alarm calls. For instance, farm study by Vidana-Vila et al., 2023 logged 1,756 vocalizations vs. only 129 coughs, reflecting how infrequent health-related sounds can be. This skew can skew model performance: a classifier may achieve high overall accuracy simply by always predicting the majority class (e.g. “no distress”), yet fail to ever detect the minority events. Such a model would appear ~90% accurate but could miss most true distress calls - a dangerous blind spot. Therefore, metrics like recall and F1-score are critical for imbalanced data (Patil et al., 2024). Recall (sensitivity) gauges how many of the actual positive (e.g. distress) events are caught, and F1 offers a balanced measure of precision and recall more informative than accuracy when one class dominates (Patil et al., 2024). Recent cattle studies emphasize reporting per-class recall and F1, especially for minority call types, to ensure that models truly recognize urgent signals. Researchers also employ strategies to mitigate imbalance. Data augmentation (e.g. synthetically boosting the under represented calls) and weighted loss functions are common approaches. For example, adding time-stretched or pitch shifted copies of rare call audio can expand the minority class and improve model generalization (Patil et al., 2024). Similarly, generative techniques are emerging, a recent work used a GAN based augmentation scheme to produce synthetic animal audio, effectively compensating for imbalanced training data (Kim et al., 2023). By addressing class imbalance through these methods and focusing on recall/F1 metrics, models for cow vocal analysis become more reliable particularly for the critical alarms (calving distress, pain moos, etc.) that matter most for intervention.

Noise, Overlap, and the “False-Alarm Tax”

Barns are chaotic soundscapes machinery drones, calves overlap calls. The noise robust NRFAR pipeline kept recall above 0.80 under moderate tractor noise (Martinez-Rau et al., 2025), but false positives doubled in full milking rush hour. A common observation is that models tend to produce more false positives in noisy conditions, by interpreting random noises as cow calls or misidentifying one cow’s call as another’s. Conversely, false negatives occurs when a cow’s call is drowned out by background noise or overlaps with another sound. The study using overlapping time windows (Vidana-Vila et al., 2023) for detection clearly demonstrated this trade-off, where setting a sensitive threshold caught all the true vocalizations but at the cost of false alarms, whereas a stricter threshold missed some quieter calls.

Figure 5 illustrates the noise adaptation loop we lean on whenever tractors or fans drown out the calls. Our noise tests underscore why the converged layout in

Figure 7 routes audio, video and THI into a single classifier, no one stream stays clean for long in a working barn.

Overfitting and Data Poverty

Even deep networks with thousands of parameters can over-memorise one herd’s pattern. Several studies admitted that their models need further validation on larger samples and in different contexts before claiming broad utility (Sharma et al., 2023)(Peng et al., 2023)(Ferrero et al., 2023). Authors of the DeepSound study admitted their 80 % F1 “would likely climb with more varied data” (Ferrero et al., 2023). Classical models fare no better, an SVM trained on 20 Holsteins failed when tested on Jerseys (Sharma et al., 2023). The absence of a public benchmark for cow estrus call detection, making it difficult to know if an accuracy of X% is truly state-of-the-art or just an artifact of an easy test set (Miron et al., 2025). Without larger, balanced datasets and public benchmarks “97 % accuracy” is often an illusion.

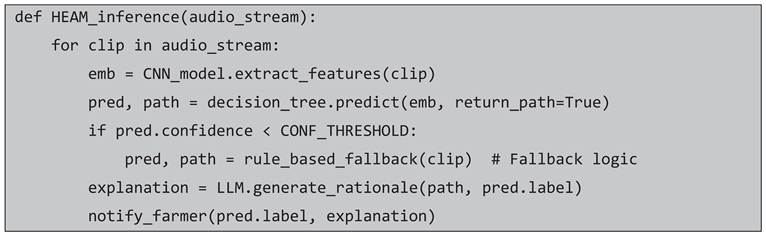

Interpretability and User Trust

Farmers distrust at black-box warnings like “Cow #103 distressed.” Heat-map ex-planations that highlight which spectrogram patch triggered the alert (a rising 650-Hz band?) are still rare in livestock work. A white-box decision-tree approach scored ~90 % accuracy while exposing its rule set, winning higher user acceptance (Stowell, 2022). Therefore, it is recommended to use hybrid model, i.e. deep front ends feeding transparent trees, so alerts come with a plain-English “why.”

Practical Pilots and Edge Constraints

Deploying multimodal acoustic models at the edge (on-farm devices) involves practical trade-offs in computing power, energy use, and connectivity. A typical scenario might integrate audio (microphone inputs) with motion data from accelerometers and environmental readings like temperature-humidity index (THI) – all processed on an embedded system near the animals. Devices such as the Raspberry Pi 4 offer a convenient platform, with a 1.5 GHz quadcore CPU and even small neural accelerators, capable of running a convolutional audio classifier alongside sensor fusion algorithms with sub-second latency. However, the Pi’s power draw (on the order of 5–7 W under load) means it usually runs on mains power or a high capacity battery. In contrast, microcontroller based units (e.g. an ESP32 or specialized TinyML boards) draw only tens to hundreds of milliwatts, enabling battery powered collars or nodes (Castillejo et al., 2019). The trade-off is limited memory and processing; these devices typically handle lightweight models (for example, simple CNNs or anomaly detectors) to keep inference times within a few milliseconds. Real-world implementations demonstrate the feasibility of edge fusion. In trial by Alonso et al., 2020, researchers outfitted cattle with a neck collar containing a 32 bit microcontroller, IMU motion sensors, and a long range radio transceiver . All sensor data were analyzed on cow using an unsupervised edge AI algorithm (a Gaussian Mixture Model), so that each hour the device transmitted only a compact summary of the cow’s activity profile (Alonso et al., 2020). This “tinyML” approach performing the AI locally and sending just the results drastically cuts bandwidth needs and latency. It also enhances reliability when connectivity is sparse. For pastures lacking Wi-Fi or cellular coverage, low-power wide-area networks like LoRaWAN are ideal, they can send small packets (e.g. an alert or health metric) across kilometers (Castillejo et al., 2019). LoRaWAN’s long range and modest data rate suit periodic status updates, whereas Bluetooth may be used for high-bandwidth sensor data transfer over short ranges (for instance, from a wearable to a nearby gateway), albeit within a barn or pen. Another example is the SoundTalks® system for pig barns, which employs an on-site smart sensor unit to continuously analyze barn acoustics and issue real-time health alerts without needing cloud processing (Eddicks et al., 2024). In practice, edge deployment of multimodal models has achieved real-time responsiveness often detecting coughs, distress calls, or estrus behaviors within seconds on-device all while keeping power usage low and avoiding the communication delays of cloud-based analysis. As shown by these deployments, a carefully optimized edge AI device (e.g. a Raspberry Pi running a fused audio+sensor model, or a custom low-power module) can reliably monitor animal health indicators 24/7, delivering prompt alerts to farmers and supporting timely interventions right on the farm (Alonso et al., 2020) (Eddicks et al., 2024).

The gap between experimental success and on-farm implementation is a critical one to bridge. Early field pilots give hope. A collar sensor running a pruned MobileNet managed 24 hours autonomy and >99 % vocal versus noise accuracy on 30 cows (Shorten, 2023), and the microphone array monitor (Röttgen et al., 2020) survived six weeks in a commercial shed. Still, each site needed bespoke re-calibration, a labour cost rarely acknowledged in lab papers. The mixed sensor evidence boosts confidence, pairing a high pitch call with accelerometer detected pacing reduced false alarms by 18 % in one fusion prototype (Lenner et al., 2023).

Until datasets span breeds and barns, and until models explain themselves, today’s flashy accuracies risk becoming tomorrow’s “doesn’t work here.” Robust AI for bovine welfare must leave the lab, survive the noise, and speak a language farmers believe.

NLP and Large Language Models (LLMs): Revolutionizing Animal Bioacoustics?

When an AI model interprets a sharp, high-pitched moo as an indication of pain, are we genuinely capturing the cow’s own communicative intent, or are we merely imposing human concepts of language and emotion onto its vocalizations?

The NLP Advantage in Decoding Animal Vocalizations

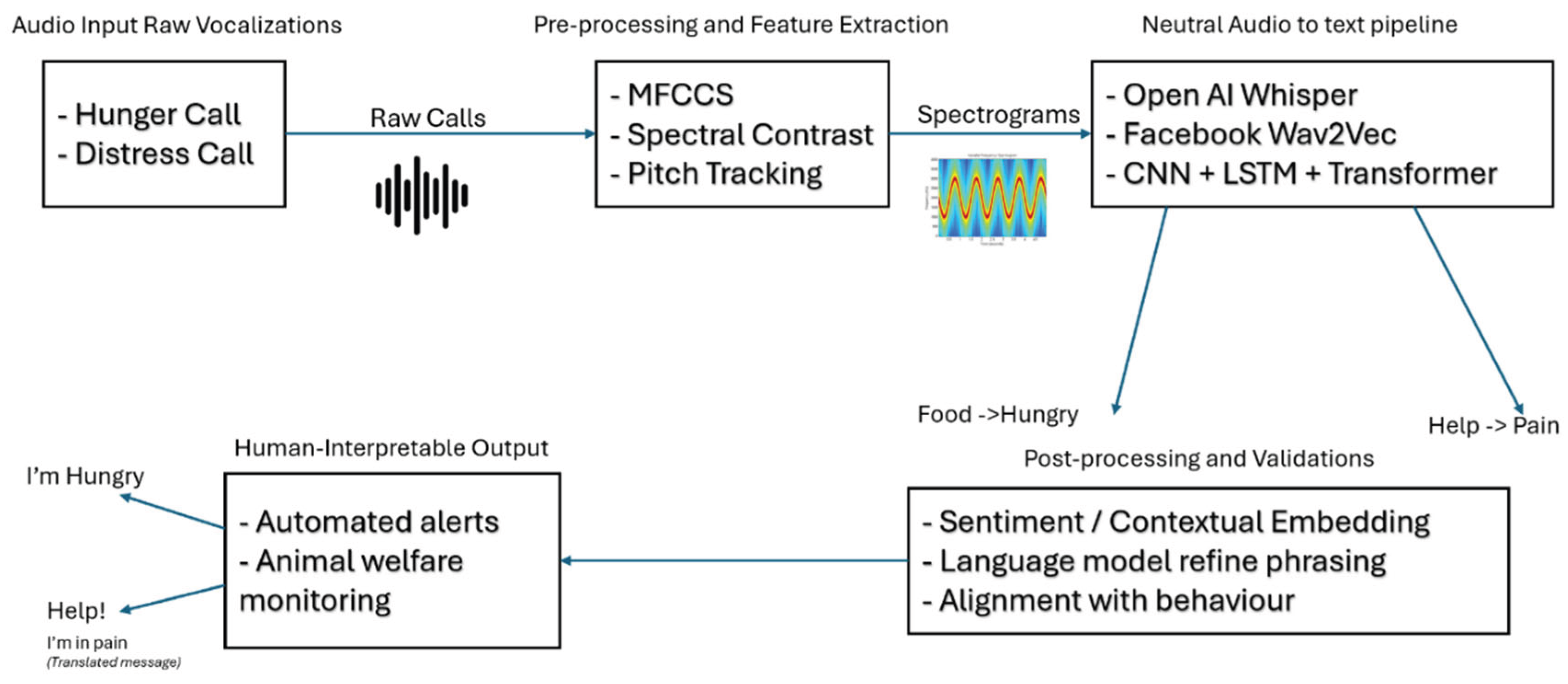

Animal bioacoustics has increasingly borrowed tools from human speech processing. Early methods extracted engineered features from recordings. For example, MFCCs and spectrograms, which compress the raw sound into measurable patterns (like frequency bands, durations, and amplitudes). However, modern deep learning studies find that such hand crafted features often underperform compared to using minimally processed inputs. MFCCs, while once popular, tend to be a poor match for convolutional networks and are often outperformed by mel-spectrograms or even raw waveform inputs (Stowell, 2022). In practice, researchers now often feed spectrogram images or learnable filter banks directly into neural networks, or apply transformer architectures (e.g. WaveNet, Temporal Convolutional Networks) to raw audio, letting the model discover the best features (Stowell, 2022). Cattle vocalizations can be converted into textual representation to perform sentiment analysis, labelling calls as conveying positive (calm/content) or negative (distressed) affect. It uses OpenAI Whisper model (originally designed for human speech) to transcribe dairy cow moos into text (Jobarteh et al., 2024). Crucially, this NLP driven pipeline was combined with traditional acoustic feature analysis, creating a multi-modal fusion of linguistic and sound features. It achieved over 98% accuracy in distinguishing distress vs. calm calls.

Beyond these acoustic representations, NLP techniques bring a new dimension. Large pre-trained models and self-supervised frameworks such as Facebook’s Wav2Vec2.0, HuBERT, or custom animal-audio models learn from vast unlabelled audio to capture general sound structures. For example, the AVES (Animal Vocalization Encoder based on Self-Supervision) model is a transformer trained on diverse unlabelled animal recordings. AVES learns rich acoustic embeddings without explicit labels, and when fine-tuned on specific tasks (like cow call classification) it outperforms fully supervised baselines (Hagiwara and Masato, 2022). In other words, models like AVES and Wav2Vec leverage huge unannotated datasets to bootstrap learning in data poor domains like cattle calls. These models are often open source; for example, the AVES weights have been released publicly (Hagiwara and Masato, 2022), enabling researchers to adapt them to livestock sounds. This is especially important in bovine bioacoustics, where gathering large, labelled datasets is challenging, thus LLM inspired models offer a way to build abundant raw audio to meaningful understanding.

Another NLP inspired strategy is to convert vocalizations into a textual or symbolic form and then apply language model techniques. For instance, OpenAI’s Whisper an encoder-decoder ASR system trained on 680,000+ hours of human speech (Radford et al., 2022) has been repurposed to process animal sounds. In a recent study, chicken vocalizations were passed through Whisper to produce “text-like” tokens and sentiment scores. Although these outputs were not literal chicken language, the resulting token patterns and sentiment scores tracked welfare states, stress conditions yielded markedly different token sequences and higher “negative” sentiment than calm conditions (Neethirajan, 2025). This suggests that even when a speech model is trained on humans, its robustness (to noise, accents, and domain variation) can still capture salient acoustic cues in animal calls (Radford et al., 2022) (Neethirajan, 2025). Similarly, audio models like Whisper or Wav2Vec2 can serve as front ends, they transform raw sound into intermediate representations (either symbolic or vector) that feed into downstream classifiers. For cows, one pipeline could first use an ASR to get a transcript like sequence and then use an LLM to infer the meaning or emotion from that sequence. This mirrors human voice assistants, they transcribe speech to text and then have an LLM (e.g. GPT) answer questions about it. Indeed, benchmarks in human speech show that a modular pipeline (ASR + LLM) can outperform end to end audio models on understanding commands. The language models we test simply plug into the back end of the audio pipeline in

Figure 4, so no extra sensors are needed to try them out.

By analogy, a “cow-voice assistant” could use an ASR (trained or adapted to cow sounds) followed by an LLM prompt to interpret a call (e.g. “alarm call during milking”) and output a human friendly explanation (like “cow appears anxious: possibly isolated calf”). Multi-modal approaches extend this further. Vocal data can be fused with contextual cues (video of behavior, environmental sensors, physiological data) to improve interpretation. For instance, study by Jobarteh et al., 2024 used a custom ontology to fuse acoustic features with NLP transcribed tokens, categorizing high frequency cow calls as “distress” and low-frequency calls as “calm,” yielding robust welfare inferences . In practice, combining sound with sensor data (movement, temperature, herd activity) creates richer context, allowing an NLP module to reason in a more human like way about the animal’s situation.

Thus, NLP methods enable us to handle unstructured audio in new ways. Self-supervised audio transformers (e.g. Wav2Vec2, AVES) can learn from unlabelled farm recordings, dramatically reducing the need for expensive annotations. Converting sounds into “text” via ASR unlocks powerful LLM reasoning (as in Whisper and AudioGPT architectures), but we must be mindful that these models were not trained on cows, so domain mismatch is a major caution. Early speech inspired features laid the groundwork, but the current trend is toward end to end learned representations that can directly capture the complexity of animal sounds.

Translating Vocalizations into Human-Interpretable Language

Ultimately, the goal is to turn a cow’s moo into a meaning that farmers can understand. In practice, this means mapping acoustic patterns to welfare indicators or behavioral states (not literally “words”). Several studies have tackled this by training classifiers on annotated calls. For example, system automatically detected lameness in dairy cows by classifying their grunts cows with a limp produced recognizably different acoustic signatures, and a model mapped these signatures to a diagnosis of “likely lame” vs “healthy”. Another project monitored calf calls in a barn, by detecting when calves vocalize and how urgently, the system inferred contexts like hunger or separation. When calf calling spiked, the AI alerted staff that “calf calling has increased possible isolation stress”. These applications show the idea of a “translation”, turning raw sounds into diagnostic or semantic labels that people can act on (Ntalampiras et al., 2020) (Jobarteh et al., 2024).

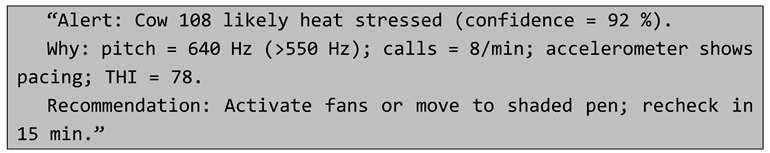

Some efforts have even built preliminary “ontologies” of vocalizations. In recent study by Jobarteh et al., 2024, researchers manually clustered cow moos by their acoustic shape and associated context, for instance, they defined a class of high pitched, harsh moos linked to agitation, and a class of low, steady moos linked to contentment. Once such categories are defined, machine learning can classify new recordings into these categories with high accuracy. Large language models can then generate a simple explanation. For example, after a bioacoustics classifier labels a call as “low-pitched, calm call of a mother,” an LLM can output a sentence like “This sound suggests a cow calmly calling her calf.” In this way, the pipeline converts a vocal event into textual advice or insight, essentially giving the cow a “voice” that humans can interpret. Every semantic tag we generate is anchored in the baseline call types set out in

Table 1, so the LLM never free wheels beyond known behavioural contexts.

However, it is crucial to remember that this is a form of inference, not a literal translation. So far, the mappings are at best coarse, calls are labelled by affect (e.g. calm vs distressed) or broad functions (e.g. feeding, social contact, panic). Unlike human speech, animal calls do not have a known lexicon of words. Instead, they carry statistical cues about internal state or immediate context. For example, an isolated calf might emit a distinctive contact call but that call is not guaranteed to mean “I am alone” in the way a word would. It simply correlates with the situation. Studies in other species show that animals do produce acoustically distinct alarm or contact calls that reliably predict a response in listeners, but these signals evolved to influence receiver behavior rather than to convey abstract meanings (Seyfarth and Dorothy, 2003). In practice, we rely on human observation to label what a cow probably means (e.g. fatigue, fear, hunger) and train the model accordingly. Some work even uses topic model techniques (like Latent Dirichlet Allocation LDA) on transcribed call tokens to find latent “topics.” For instance, a study of poultry Whisper output applied LDA and found clusters of token sequences that neatly separated stressed from unstressed calls (Neethirajan, 2025). This unsupervised approach discovered recurring “themes” in the data without pre-defined labels, akin to a taxonomy of call types.

Figure 6 shows an NLP enabled workflows translating acoustic features of bovine vocalizations into interpretable textual descriptions. (e.g., converting distress calls to ‘I need help’).

Comparing approaches highlights the old vs. new, classical taxonomic models like LDA or k-means can group calls into clusters, but they lack the rich semantics of pre-trained models. By contrast, foundation models (audio or text based) offer deep representations that might capture subtle patterns across contexts. For example, an LLM or audio transformer could represent a call by its emotional tone, rhythm, and spectral features simultaneously, potentially linking it to learned concepts from human language. Open source frameworks are emerging too, researchers have begun fine-tuning speech transformers on animal data or using multi-modal fusion to jointly model text and sound (Jobarteh et al., 2024).

Thus, translating calls is more about classification than literal language. Current systems label moos with welfare relevant tags (pain, hunger, calmness) and then summarize them in plain text, but this “dictionary” is human constructed and far from complete. Calls often have graded acoustic variation rather than discrete units, models may group them by context (using topic models or embeddings) rather than by fixed “words”. In essence, we interpret calls as “messages” about need or affect, but always as probabilistic signals inferred from context. Building larger, multi-herd datasets and richer ontologies will help, but semantic ambiguity will remain a core challenge.

Table 5, shows comparison of state-of-the-art NLP and speech models for animal bioacoustics, outlining inputs, purposes, and trade-offs.

Leveraging Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Learning

A significant hurdle in decoding animal vocalizations is the limited availability of labelled training data. It is infeasible and expensive to gather thousands of examples of every type of cow call along with ground truth annotations of what they mean. Few-shot and zero-shot methods aim to sidestep this. These approaches allow AI models to generalize from very few examples by relying on prior knowledge learned from other data. In the context of bovine acoustics, using few shot learning means a system could learn to recognize a new kind of vocal signal from only a handful of labelled instances. For instance, study by Nolasco et al., 2023 showed that feeding only five labelled examples of a new cow vocalization into a pretrained network allowed accurate detection of that call in continuous audio. The aforementioned AVES model exemplifies this, after self-supervised pretraining on extensive unlabelled animal recordings, AVES can be fine-tuned with very little cattle data and still achieve high accuracy (Hagiwara and Masato, 2022). Essentially, any new animal call classification task can start with AVES’s original feature set i.e. “prior knowledge” and require only a tiny fraction of data for training compared to starting from scratch.

Language models offer another twist on data efficiency. Systems like AudioGPT (and related frameworks) use LLMs as high level controllers to orchestrate specialized modules. AudioGPT for example complements ChatGPT with pretrained audio encoders and ASR/TTS interfaces (Huang et al., 2023). In principle, one could ask such a system: “Detect if any cow is in distress”. The LLM would then call on an off-the-shelf cow-call detector and emotion classifier (none of which were trained on that exact query), combine their outputs, and answer the question. This kind of zero-shot chaining means we can tackle new inference tasks without retraining models end-to-end for each task. Similarly, a model trained to recognize “distress” sounds in one species might detect analogous distress cues in cows, even without cow specific training, if arousal related acoustics overlap across species. (Indeed, cross species studies suggest that certain vocal indicators of negative emotion like a raised fundamental frequency appear broadly in mammal (Seyfarth and Dorothy, 2003).) Certain acoustic characteristics of arousal or pain are conserved across species, suggests a well trained model might detect, signs of agitation in cow calls even if it was trained on a broader bioacoustic dataset not specific to cows (Lefèvre et al., 2025).

Generative models further bolster these low-data strategies. Neural audio synthesis (using GANs, diffusion models, or autoregressive “neural vocoders”) can create synthetic cow calls to augment training sets (Pallottino et al., 2025). For a rare alarm call, an AI could learn its acoustic pattern and generate many realistic variants. Early work in birdsong and marine mammal bioacoustics has shown that such synthetic augmentation can improve classifier robustness. Some of the studies used controlled sound generation techniques to model animal calls, generating simulated examples that help explore and validate classification methods (Hagiwara et al., 2022a). Such synthetic data approaches, combined with few shot learning algorithms, form a powerful toolkit. Thus, rather than collecting extensive new datasets each time, few shot capable models let us quickly calibrate to these conditions on unseen vocal behaviors. In the bovine context, generative models might simulate how a calf’s bleat sounds under extreme hunger or stress, providing novel examples that are hard to capture in real life. However, care is needed, if synthetic examples are not truly representative, they could mislead the classifier. Every few-shot or synthetic inference must still be validated with real data and ethological expertise.

Data efficiency tricks are indispensable in livestock bioacoustics. Self supervision (AVES, Wav2Vec) and transfer learning let us exploit existing audio or language models so that only a few bovine examples are needed to build a useful detector. Zero-shot compositions (with LLMs directing ASR, etc.) promise flexible question-answering about animal sounds. Generative augmentation offers another path to “new” data. Yet all these methods demand caution, few-shot models can be overconfident, and zero-shot guesses can be wrong if human priors are incorrect. Rigorous testing (and human in the loop checks) is essential to ensure that a model fine-tuned on minimal examples truly generalizes to new herds and settings.

Addressing Technical and Ethical Challenges

Applying NLP tools to cattle calls involves both practical and philosophical hurdles. On the technical side, recording quality and environmental noise are major issues. Farm audio is often noisy, machinery, other animals, wind, and crowd vocalizations overlap. Models trained on clean, close range recordings may fail in a barn. Before we worry about bias, we have to survive the barn’s acoustic chaos, hence the noise adaptation loop implemented in

Figure 5. Researchers are tackling this with robust preprocessing: for example, “bio-denoising” networks have been developed that can clean noisy animal calls without requiring a clean reference (Miron et al., 2025). Data scarcity and variability are also critical. Cows of different breeds, ages, or individual personalities vocalize differently, and even the same cow varies its calls by context. A dataset collected on one farm might not represent another. To improve generalization, scientists expand training sets across farms, use data augmentation (pitch/time shifts, background mixing), and rely on the self-supervised pretraining mentioned above (Hagiwara and Masato, 2022). In practice, multimodal fusion mitigates many issues, combining sound with video tracking or accelerometer data can disambiguate a call’s meaning. For instance, a cow vocalizing while lurching could be interpreted differently from a cow vocalizing during feeding. Indeed, integrating audio with movement and temperature sensors is emerging as a best practice for accurate interpretation (Chelotti et al., 2024).

Ethically, the foremost concern is misinterpretation. A model that falsely dismisses a real distress call (false negative) or falsely alarms on normal behavior (false positive) can erode trust. For any critical application (health monitoring, welfare alerts), it is important that a human verify the model’s output. Closely related is the risk of anthropomorphism. Labelling cow calls with human emotions (“happy,” “frustrated”) or intent implies a level of understanding we do not have (Seyfarth and Dorothy, 2003) (Watts and Jon M, 2000). At best, such terms are convenient proxies; at worst, they may mislead caretakers into thinking the AI sees more than it does. Ethical use requires that we present predictions as probabilistic indicators (e.g. “possible hunger signal”) rather than factual translations.

On privacy and data issues, livestock voices themselves are not protected personal data. However, farm managers and workers should consent to recordings and be aware that audio data can indirectly reveal sensitive information (such as an outbreak of illness by elevated coughing). Transparency with stakeholders about data use is important. More broadly, the goal of this technology is to help animals. For instance, by alerting farmers to pain or stress earlier than might be noticed. We must ensure these AI tools are used to improve welfare not to justify neglect. This ethical framing means constantly evaluating: Do cows vocalize more as a cry for help than a guarantee of help? Is a detected “stress call” actually leading to timely intervention? Building systems with veterinarians, ethologists, and farmers is crucial to keep the technology grounded.

Controversies and Anthropomorphism Risks

Using human language techniques on animals inevitably raises philosophical questions. A key debate is whether we are projecting human concepts onto fundamentally different communication systems. Critics warn that terms like “dog saying hello” or calling a chicken’s cluck “excited” are anthropomorphic shortcuts that may misrepresent animal experience. In scientific terms, cows likely do not use language with syntax or symbolic semantics. Rather, as ethologists note, vocalizations serve to influence listeners and reflect the caller’s state, not to share an explicit message with intent (Seyfarth and Dorothy, 2003) (Watts and Jon M, 2000). For example, a cow’s alarm grunt might occur because she is frightened listeners hear this and may infer “danger” but the cow is not “saying the word ‘danger’.” She’s producing an arousal driven call. Listeners (including AI models) then pick up information correlating with context. In short, cows broadcast their condition (“I’m agitated!”) more than they communicate in the human sense of intentional messaging (Seyfarth and Dorothy, 2003) (Watts and Jon M, 2000).

Philosophically, this limits how much we can “translate.” Human language involves shared symbols and often complex syntax. Animal signals, by contrast, tend to be graded and multi-dimensional. A cow’s vocal repertoire may blend elements of urgency, pitch, duration in ways that do not neatly segment into words (Cornips, 2024). Any attempt to label these by human feelings (happy/sad) or discrete semantic units is necessarily an approximation. For instance, labelling a call as “pain” assumes a one-to-one mapping, but in reality, a painful experience might produce a range of call variants. Studies caution against reifying these labels. We should remember that our so called “translations” are inferences. This aptly captures the difference, the cow’s moo reflects her physiology and emotions, but she is not conversing in a language.

Empirically, we lack ground truth semantics for cow calls. Unlike human speech datasets (which have transcripts and meanings), cattle datasets rarely have verified meanings beyond the context (e.g. recorded after a stimulus or during a known condition). This means any model output is unverified interpretation. It’s possible to statistically validate that certain calls predict certain outcomes (say, high-arched moo precedes feed delivery), but even then, we may not understand why the sound has that shape. The absence of a “cow dictionary” means our AI pipelines must remain humble. They can suggest alerts or categories, but they cannot claim absolute understanding.

In weighing functional versus affective interpretations, modern consensus is that animal calls often convey both, but primarily through correlations rather than explicit semantic (Seyfarth and Dorothy, 2003). A single grunt could function as an alert (a referential role) and also indicate fear (an affective overlay). Our models usually focus on affective classification (distress vs calm) because that is more reliably observed. Contrastingly, assigning specific referential meaning (like “there is a fox”) is generally unsupported except in a few well studied species. For cows, we have no evidence of such referential calls. Thus, when an AI says a cow is “crying for her calf” or “suffering,” it is drawing on human analogies to emotions, not decoding a literal statement from the cow. This is not necessarily wrong (cows do separate-calm versus isolation-distress), but it is a guess that requires validation with behavior or physiology. Ultimately, the anthropomorphism risk reminds us to interpret AI outputs with care. The utility of these systems lies in pattern recognition, not in bridging a mysterious language gap. If an NLP model tells us “Cow likely in pain,” we should verify with physical signs (lameness, vitals) rather than assume the AI speaks cow truth. In other words, a robust result was consistent change in the model’s token stream, not a decipherable message.

Industrial Applications and Animal Welfare Impacts

Imagine a barn capable of signaling the moment a cow experiences discomfort; while early AI alerts could enhance the quality of care, there may also be concerns that continuous digital monitoring adds complexity and additional data burdens to the management of precision livestock farming.

AI-Enhanced Precision Livestock Farming

Modern farms are piloting AI driven vocalization monitors to capture subtle health and reproductive signals. Precision Livestock Farming (PLF) is increasingly adopting AI tools to continuously monitor individual animals and make farm management easier. A review noted that health and disease detection are most common targets for machine learning in dairy farming (Slob et al., 2021). Parallel advancements in deep learning applied to cattle imagery. Automated body condition scoring or lameness detection via computer vision, explains AI’s growing role in herd management (Mahmud et al., 2021). In the bioacoustics domain, studies have shown that collar mounted acoustic sensors can automatically monitor feeding behavior. Modern farms are piloting AI driven vocalization monitors to capture subtle health and reproductive signals. For example, wearable collars equipped with microphones and motion sensors now perform on board analysis of each cow’s behaviour. A recent system used a collar containing a micro-processor, accelerometers and an LPWAN radio to process feeding and activity patterns locally (Martinez-Rau et al., 2023) (Martinez-Rau et al., 2024). Every hour it computes how much time the cow spent grazing, ruminating, or resting, and transmits a concise summary to the farmer. If a cow’s eating rate or total chewing time drops below normal, the system can promptly alert farmers stating a potential early sign of illness or discomfort that might otherwise go unnoticed until the cow’s condition worsens.

AI based analysis of vocalizations is also being applied to broader behavioural and physiological indicators. ML models can classify different types of cattle calls that correspond to important states. The system can distinguished food-anticipation calls, estrus calls, coughs, and normal mooing with over 80% accuracy (Lefèvre et al., 2025). This means the farm will receive a notification that a particular cow is likely in heat or that a cow may be starting to cough abnormally (indicating respiratory issues), enabling faster intervention. Similarly, analysis of vocal responses during stressful events are studied, like, dairy cows isolated from their herd generates characteristic distress calls. An AI model trained on such vocalizations was able to recognize these stress induced calls with nearly 87–89% accuracy, and even identify which cow was calling in many cases (Gavojdian et al., 2024). This capability to pinpoint an individual animal in distress is valuable for large herd management, thus the system essentially gives a specific cow the ability to “call for help” and be heard in a crowd.

Beyond acoustics, PLF systems get multiple benefits from multimodal data integration. Wearable accelerometers and other sensors in addition to audio, helps by capturing behaviors like lying, walking, or standing, which may not always be inferred from sound. Combining these streams provides a richer context. For example, pairing vocalizations with activity data can differentiate between a true alarm versus harmless excitement (Russel et al., 2024). Collar and leg motion sensors achieved high accuracy in classifying cow activities (like resting vs. feeding) and further used those patterns to detect early signs of illness (mastitis) with over 85% accuracy (Shi et al., 2024). This illustrates how AI can synthesize signals to not only monitor routine behavior but also flag subtle health issues before they become severe. Different ongoing research are addressing issues like computational resources, noisy farms, data limitations through better noise filtering, energy efficient algorithms, and training on more diverse datasets to generalize across environments.

These on-animal IoT systems effectively turn each cow into an active sensor node. By continuously translating jaw movements and vocal sounds into data, they shift farmers from reactive crisis-responders to proactive caregivers. Trusted alerts about subtle welfare signals (like reduced chewing or a distress call) can improve outcomes, but only if the farmer believes “the cow alarm means something’s wrong.”

Real-World Deployments and Use Cases

Several pilot projects and products illustrate how vocalization AI is being deployed. For instance, independent of collars, some farms install fixed microphones in barns or pens to monitor group level sounds. Study (from a pig-farm study) shows ceiling mics capturing grunts and coughs for automated analysis (Vranken et al., 2023). In cattle, similar acoustic arrays have been trialed, one trial used a network of barn microphones to detect calf distress calls amidst background noise. In another case, a hybrid CNN-LSTM system processed calf vocalizations in real time to alert caretakers when calves were calling frequently (a sign of separation distress). Likewise, startups have begun integrating voice interfaces: a prototype voice assistant, for example, could announce “Cow 17 is in heat” based on detected estrus moos. Across these pilots, performance is mixed. Field evaluation of a CNN-based cow-call detector by Vidana-Vila et al., 2023, (trained on two farms) achieved only ~57% F1-score (about 74% recall) when evaluated cross-site indicating many missed calls or false alarms in new settings. In practice, farmers report that such systems can improve vigilance. For example, early coughing alerts allowed earlier treatment of respiratory illness, but also warn of false alarms. Usability factors also matter, battery life, connectivity, and ease of interpreting alerts all influence adoption. Several farmers said they would only trust a “vocalization alarm” if false alerts were low and the interface was simple.

Real-world tests show promise but also caution. Smart collars and barn mic systems can indeed catch important events (estrus cycles, cough outbreaks) early. However, their welfare impact hinges on reliability and usability. High false alert rates or complex dashboards could negate benefits. Designers must balance sensitivity with precision and involve farmers in tuning systems for their herd and workflow.

Early Intervention through Vocalization Analysis

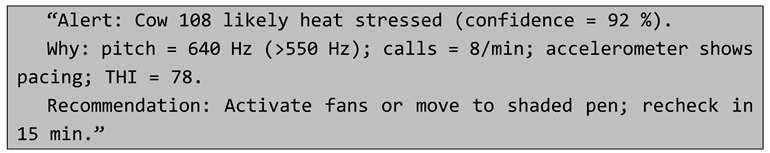

A major benefit of decoding cow vocalizations is the potential for early detecting signs of trouble in a cow’s vocal signals before the situation worsens. Cattle often give subtle signals of distress or need through changes in their call patterns. By continuously monitoring these vocalizations, systems can serve as watchkeeper who will alert farmers to issues that might be missed. An unusual coughing sound can flag a respiratory infection, a distinctive mating call can alert that a cow is in estrus, and an increase in urgent, prolonged mooing may signal pain or distress (Gavojdian et al., 2024), (Sattar and Farook, 2022). Bioacoustic research has shown that we can sometimes reduce the stress by using sound as a gentle intervention. An example is the use of calming cattle vocalizations, like playing a recorded mother-cow call (a low soothing “moo” used by cows to calm their calves) significantly reduced stress in other cows during a stressful restraint procedure (Lenner et al., 2023). Similarly, gentle human vocalizations have been shown to induce positive relaxation in cattle heifers that heard a soft, soothing voice (either live or via recording) while being stroked exhibited signs of comfort, with live speaking having a slightly greater effect (Lange et al., 2020). These findings suggest that farmers can not only listen for distress, but also “talk back” to their animals in a sense using known comforting sounds to ease cattle during events like veterinary exams, transport, or isolation. Such interventions, informed by an understanding of cow communication, can prevent a minor stress from increasing into a major welfare problem. When the system flags an unusual bellow, we still double check it against the baseline in

Table 1 before sounding the alarm.

Implementing vocalization based alerts on the farm does require careful coordination. Clear, spoken feedback like the example in