Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Basic Properties of the Approximate Symmetric Chordal Metric

- NaN ∘ a = NaN, NaNa = NaN, aNaN = NaN, where , × and / are the multiplication and division binary operations, and .

- NaN ∘ a = NaN ∘ βı, NaNa = NaN + NaNı, aNaN = NaN + NaNı, for .

- |NaN| = NaN, min(NaN, a) = a, max(NaN, a) = a, for .

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- , ;

- (iii)

- , ;

- (iv)

- if and are infinite;

- (v)

- ;

- (vi)

- , if is infinite, ;

- (vii)

- if and or , or both, are finite.

3. Algorithms for Computing the Approximate Symmetric Chordal Metric

3.1. Conceptual Algorithm

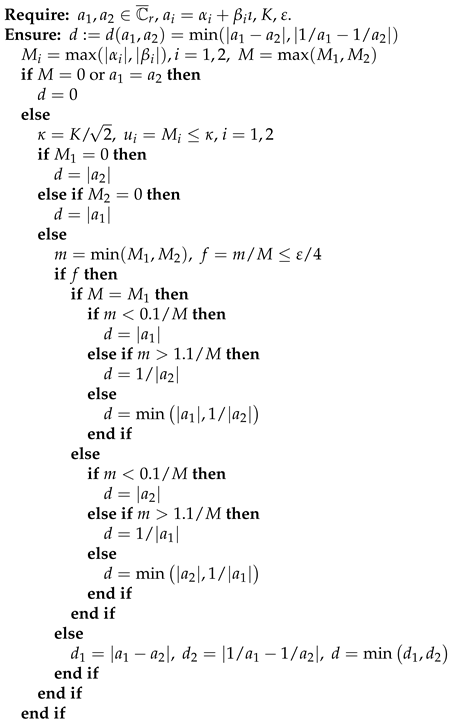

| Algorithm 1 chordal computes ASCM for two complex numbers |

|

3.2. Computation of ,

| Algorithm 2 absa computes the modulus (or its factored representation) of a complex number |

|

3.3. Computation of ,

| Algorithm 3 subtract computes the difference of two complex numbers |

|

3.4. Computation of , Using

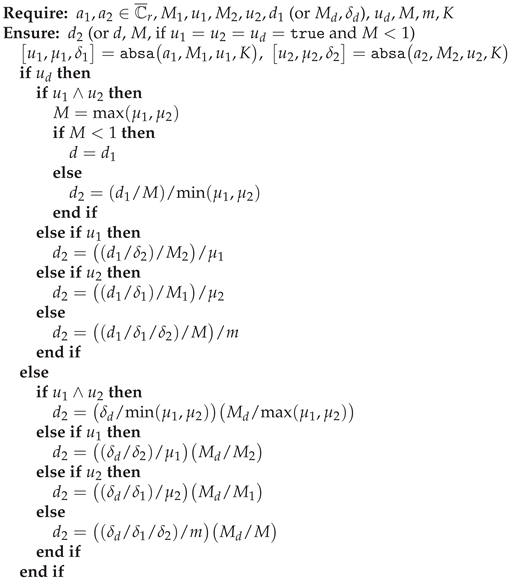

| Algorithm 4 d2byd1 computes in (1) using |

|

3.5. Direct Computation of

| Algorithm 5 inva computes the reciprocal of a complex number given its modulus or factored representation |

|

4. Numerical Results

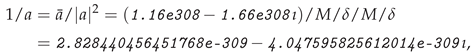

4.1. Detailed Examples

4.2. Large Experiment with Randomly Generated Examples

- The for loop with counter ii generates numbers s1 between (realmin) and 8.988465674311580e+307, which is very close to, but smaller than , (realmax), the relative error being smaller than 5.552e-17. The number s1 multiplies pseudorandom double precision values drawn from the standard normal distribution (with mean 0 and standard deviation 1), to obtain the real and imaginary parts of . If any of the computed parts of exceeds K in magnitude, i.e., if is obtained, that value is reset to . The number is obtained in the same way in the internal loop with counter jj. The second part of the code segment has and use it to obtain ; is generated as above. The last part also sets , and use it to obtain . Clearly, complex numbers with and/or are generated.

- which ensures that the (initial) seed of the random number generator is the same, and therefore the same sequence of random numbers is generated after using this command. However, for some further tests, the generating sequence has been run repeateadly several times, but the rng( ’default’ ) command has been placed just before the first run. This way, a larger number of tests have been performed.

4.3. Block Diagonalization of a Matrix Pencil

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klamkin, M.S.; Meir, A. Ptolemy’s inequality, chordal metric, multiplicative metric. Pac. J. Math. 1982, 101, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasane, A. A generalized chordal metric in control theory making strong stabilizability a robust property. Complex Anal. Oper. Theory 2013, 7, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitrakis, M. Notes on Complex Analysis. 2019. Available online: http://fourier.math.uoc.gr/~papadim/complex_analysis_2019/gca_vvn_r.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Rainio, O.; Vuorinen, M. Lipschitz constants and quadruple symmetrization by Möbius transformations. Complex Anal. Synerg. 2024, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C. Complex Analysis I, MAT 536, Spring 2024. Stony Brook University, Dep Mathematics, 100 Nicolls Road, Stony Brook, NY 11794, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Tuñón, O.; Brodskiy, Y.; Kayacan, E. Loss it right: Euclidean and Riemannian metrics in learning-based visual odometry. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2401.05396v1 [cs.CV]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Pang, H.K.; Li, W.; Huang, X.; Guo, W. On the explicit expression of chordal metric between generalized singular values of Grassmann matrix pairs with applications. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 2018, 39, 1547–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.-g. Perturbation theorems for generalized singular values. J. Comput. Math. 2025, 1, 233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Sasane, A. A refinement of the generalized chordal distance. SIAM J. Control & Optimiz. 2014, 52, 3538–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavely, C.; Stewart, G.W. An algorithm for computing reducing subspaces by block diagonalization. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1979, 16, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, G.H.; Van Loan, C.F. Matrix Computations, fourth ed.; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, Maryland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, J.H. The Algebraic Eigenvalue Problem; Oxford University Press (Clarendon): Oxford, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, J.H. Kronecker’s canonical form and the QZ algorithm. Lin. Alg. Appl. 1979, 28, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.W. On the sensitivity of the eigenvalue problem Ax=λBx. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1972, 9, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmel, J.W. The condition number of equivalence transformations that block diagonalize matrix pencils. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1983, 20, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kågström, B.; Westin, L. Generalized Schur methods with condition estimators for solving the generalized Sylvester equation. IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 1989, 34, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Bai, Z.; Bischof, C.; Blackford, S.; Demmel, J.; Dongarra, J.; Du Croz, J.; Greenbaum, A.; Hammarling, S.; McKenney, A.; et al. LAPACK Users’ Guide: Third Edition; Software · Environments · Tools, SIAM: Philadelphia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- MathWorks®. MATLAB™, Release R2024b.; The MathWorks, Inc.: 3 Apple Hill Drive, Natick, MA, 01760, 2024.

- Wolfram, S. The Story Continues: Announcing Version 14 of Wolfram Language and Mathematica, 2024. Available online: http://writings.stephenwolfram.com/2024/01/the-story-continues-announcing-version-14-of-wolfram-language-and-mathematica (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Malcolm, M.A. Algorithms to reveal properties of floating-point arithmetic. Commun. ACM 1972, 15, 949–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentleman, W.M.; Marovich, S.B. More on algorithms that reveal properties of floating point arithmetic units. Commun. ACM 1974, 17, 276–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.; Vandenberghe, L. Convex Optimization; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).