1. Introduction

In 2020. European Commission published the European Union’s (EU) goal of be-coming the first climate-neutral economy and society by 2050. The main and urgent challenges identified on the way to this goal are climate change, resource scarcity and environmental degradation. The development of the circular economy (CE) supported by Industry 4.0 (I4.0) was adopted as a key strategy [1]. CE is a new emerging paradigm of sustainable development [2,3] and a key sustainability framework covering the global challenges of environmental degradation, generation of waste, resource depletion [4] and gas emissions [2]. CE is also a conscious, forward-looking, long-term, holistic approach, based on sustainability, vision and systemic transformation and disruptive innovation [5]. CE is an alternative to the still dominant linear model of production and consumption. It aims to keep products and materials in the value chain for a longer period of time and to recover raw materials for reuse at the end of products’ life. In a circular economy, it is important that waste is treated as a secondary raw material. All pre-waste activities are intended to serve this purpose. At the same time, the circular economy approach, implemented e.g. with regard to the design of products and production processes, aims to increase the innovation and competitiveness of companies. By pursuing the goals of CE, companies have the opportunity to grow in collaboration with different stakeholders. Sustained, long-term cooperation based on trust facilitates the realisation of innovations that benefit producers (mainly cost and image) and their stakeholders. The effectiveness of their actions depends on: (1) the approach to the CE concept itself and its integration into business practices, i.e. actions taken by companies in the area of the circular economy should be an integral part of the company’s strategy, at every stage of its development. CE at company level is determined by cooperation business to business (B2B). However, business-to-business cooperation is not an end in itself, but should be properly used by companies as a specific strategic tool to achieve their goals, including finding and implementing innovative solutions that strengthen their competitive position and serve the long-term development of their business relationship partners.

Cooperation in the field of CE, undertaken between companies and their stake-holders, is nowadays an important and widely discussed research topic in the economic and social sciences. It brings numerous benefits to businesses, their partners and society as a whole, as well as to numerous ecosystems and the natural environment. In view of the ongoing adverse climate change and environmental degradation, the rapid and sustainable implementation of CE demands is a pressing issue for humanity.

The paper covers the results of theoretical and empirical research. The theoretical part of the paper is a systematic review of the current state of research on the topic of CE (definition, objectives, benefits, producers and their stakeholders, cooperation), made on the basis of 30 selected scientific articles from the beginning of 2025 on the topic of CE and placed in open access on Web of Science (2. Closed loop economy – literature review). The empirical part of the paper presents the results of a 2024 national survey (Poland). The research focused exclusively on B2B stakeholders who are cooperatively implementing and benefiting from CE demands (4. Results – business to business cooperation on the circular economy, in surveys). Empirical research has been dedicated to the B2B sector. It would be interesting to extend this research to include the cooperation of manufacturing companies with stakeholders other than supply chain companies. This is a limitation of the empirical part of paper. A strength of the research is its national coverage of Poland.

The aim of the paper is to identify forms and areas of cooperation between manufacturing companies and their stakeholders in circular activities. The analysed forms of cooperation are: common norms and standards of operation; exchange of information; joint training; consultancy; exchange and sharing of equipment; cooperation in the acquisition of new technological and innovative solutions; agreement of partners to unannounced internal and external audits.

The paper focuses attention on finding answers to the following research questions:

what is the essence of the circular economy and what is its significance for the realisation of sustainable development? What social, economic and environmental benefits are associated with the implementation of the CE in the economy? What is the significance of the CE for business efficiency?

what is the importance of sustainable innovation in circular business operations?

what is the importance of cooperation between companies in shaping their competitive advantage in the market and in implementing circular actions in supply chains?

what is the importance of integrating the idea of CE into the business strategy for the intensity of B2B cooperation in circular activities?

what is the extent of cooperation between manufacturing companies and their stakeholders in Poland in terms of circular activities?

The answers to the above questions made it possible to assess the cooperative orientation of manufacturing companies in Poland and their stakeholders towards the implementation of CE practices, as well as pointing out the numerous benefits of cooperation between manufacturers and their stakeholders.

The audiences who may potentially be interested in the research results presented in this paper are researchers and managers working in the field of CE, sustainability and sustainable management.

2. The Circular Economy – Literature Review

At the beginning of 2025, CE goals were defined in the literature as follows:

restoring the highest value and usability of materials, components and products [2] as a result of methods: comprehensive rethinking of current production and consumption systems, increasingly better design of systems and business models and durable products (long-lasting design), their maintenance and wear assessment [2,4], and – as a result of the implementation of the R-strategies: refuse, rethink, reduce, reuse, repair, refurbish, remanufacture, repurpose, recycle, recover, redesign, resilience, regulate [4,6];

to have a positive impact on the economy, the environment and global geopolitics [4,5] by inducing changes in resource-intensive sectors (e.g. mining, manufacturing) and the development of service sectors (repair, maintenance, rental, leasing), thus shifting from a linear economic model (extract, produce, use and discard) to a circular economy (produce, use, service, reuse) [7];

building a network of sustainability links between different stakeholders [8] (suppliers, customers, clients, competitors, owners, co-owners, investors, strategic allies, regulators, R&D institutions and consortia, and representatives of administrations at different levels), focused on: shared sustainable goals, collaboration, synergies and economies of scale, knowledge creation and exchange, research and development, open innovation (OI), technological innovation, development of sustainable strategies and practices [3,7,9,10,11];

- 3.

reducing: dependence on fossil fuels (decarbonisation), resource consumption, waste (moving towards waste-free production), gas emissions, energy leakage and environmental degradation – by increasing the sustainable use of resources (including waste as a renewable resource) and renewable energy [2,4,12,14,15,16,17,18], thus slowing down, narrowing and closing material and energy loops [19];

- 4.

strengthening the energy security of states and the security of NATO, EU and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [13];

- 5.

restoring, restoring resilience, protecting and conserving the unique natural resources of ecosystems and prioritising the restoration of climate system stability [8,9], and strengthening the resilience of sustainably managed businesses and business networks and the circular economy [16,20,21,22,23];

- 6.

developing new sustainable consumption habits and patterns in societies [24].

The lasting benefits of the conscious and long-term application of the postulates of CE and sustainable management in companies are:

a multifaceted and synergistic increase in economic, environmental and social performance [4,6], e.g.: increased innovation and productivity of national economies, significant material savings, reduced operating and maintenance costs, reduced resource-intensity of production industries, improved profitability of enterprises and increased resilience, creation of a positive image of producers applying extended responsibility, development of integrated value and supply chains, growth of effective and profitable business models and networks, reduced prices for customers, safe and stable environmental conditions, rapid macro-regional development, increased social welfare [23,24];

a 1% reduction in material and energy consumption across all sectors in Poland, according to calculations, could result in an economic growth of 19.5 billion PLN [24]. Furthermore, if the reduction in material and energy consumption in Poland exceeded 1% and 20% of the savings (PLN 92 billion per year) were invested in the bioeconomy, construction and transport sectors – Poland’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) could reach PLN 167 billion [24]. Shifting taxation from labour to natural resources and consumption could lead to a 7.7% increase in Poland’s GDP and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions would decrease by 5.7% with respect to the baseline scenario [24].

The benefits of CE are contingent on cooperation, industrial symbiosis in entrepreneurial ecosystems, i.e. networks of companies and their stakeholders. The sustainability of these networks requires congruence between the values, goals and needs of the partners that make up the network [20]. This has been confirmed by numerous studies.

In Nigeria, a survey was conducted with 611 automotive companies that are members of 20 clusters from 20 cities. The results of this research defined the following benefits of participating in a network focused on closing the loop and sustainability [11]:

effective learning and flow of information, knowledge and best practices;

an increase in technical, organisational and business capabilities;

system improvements, process innovations, resource optimisation, waste reduction;

the emergence of cluster leaders as central network nodes with significant digital advances (e.g. computer diagnostic capabilities for cars).

Subsequent research looked at CE collaboration between local and international stakeholders (companies, industrial consortia, suppliers, customers, clients, research and training institutions and investors), based on OI practices. A core practice of IO is to engage audiences and customers in designing products that meet needs and increase the satisfaction and loyalty of those audiences and customers. This and other IO practices were intended to help network partners overcome the barriers to transitioning from a linear economy to a CE – with numerous benefits achieved, such as a culture of collaboration, exchange of expertise, skills development, access to and integration of technology, development of closed-loop products and processes, significant economic and technical performance, and the ability of the largest and most resourceful network partners to pressure external stakeholders to leverage investor resources for CE initiatives [25].

Research and development (R&D) consortia are of strategic importance for implementing large-scale sustainable systemic change that coincides with CE goals, as their role is to share knowledge and responsibility. The risk of implementing change is spread across multiple stakeholders with consistent goals. This makes networks catalysts for solving CE problems [8].

Another study involved textile and clothing companies. These included the introduction of a digital product passport (DPP), which is a tool that enables textile and apparel stakeholders (manufacturers, suppliers, customers, clients, government organisations and public institutions) processes such as [26]:

product traceability – storing and making available comparable information about a product and tracking its life cycle phases, characteristics and environmental impacts;

informed decision-making;

promotion of transparency, sustainability and CE.

Product lifecycle management (PLM) is a process to track and coordinate all stages of the product lifecycle such as design, production, use and disposal. The following indicators and approaches are used in this process [14]:

index of repairability (IoR);

repair score system (RSS);

ease of disassembly metric (eDIM);

design for repairability (DfR);

repair oriented design (RoD).

Two factors are estimated to be particularly important for CE: controlling the take-back channels of products, at the end of their useful (operational) life, and encouraging consumers to use products for as long as possible [16].

Numerous research studies address the stimulation of CE by I4.0 and Industry 5.0 (I5.0) technologies [15,27]. It is even believed that the implementation of sustainability-oriented technologies and innovations determines the CE [28].

Technology collaboration between companies can include practices that support CE such as backward and forward vertical integration, automation, virtualisation, increased traceability, energy management, increased flexibility, process optimisation, reduced material and energy consumption, data collection and processing, production planning, monitoring, system failure prediction, decision-making and others [3].

The results of a study of six manufacturing companies operating with I4.0 technologies, lean production (LP) practices and CE strategies confirmed the existence of a synergistic interaction – I4.0 technologies and LP practices support each other and enable the implementation of CE strategies [10].

Research in India, involving academic and industry experts, has identified key factors for the impact of I4.0 on CE performance and these are: the presence of economies of scale in the sector, managerial support, operational efficiency, and the cost of investment [29].

Another study was carried out in the textile manufacturing sector. In their first stage, a literature review was conducted, resulting in the identification of 17 CE attributes. In the second stage of the research, these 17 CE attributes were assessed by 50 experts. It was concluded that the most important factors accelerating the implementation of CE in the textile manufacturers’ supply chain were the involvement of top management, the cooperation of different stakeholders, and the increase in knowledge and skills of employees [30].

In addition to the cooperation of the internal stakeholders of manufacturing companies (managers and employees), multifaceted cooperation with the external stakeholders of these companies (suppliers, customers, clients, competitors, owners, co-owners, investors, strategic allies, regulators, R&D institutions and consortia, and representatives of various levels of government) is also important. For the development of CE, the important role of policymakers in encouraging investments that coincide with CE demands is also highlighted [31], as well as the importance of researchers in developing new, unconventional methodologies that should enhance trust, security and the resilience of sustainability efforts to adverse populist narratives [21].

3. Materials and Methods

A literature research of the current state of knowledge in the area of CE was conducted between 1 January 2025 and 12 May 2025. A systematic review method (collecting the available scientific literature in a systematic way), analysis and synthesis was used. A systematic review shows how data will be collected, analysed and presented. The first step in this method was to establish the criteria for the study (key phrase: “circular economy” in the title of the scientific paper) and to select 75 open access articles on Web of Science, published in English, in 2025. Thirty sources of relevance to the research objective were then selected. In the final step of the systematic literature review method described above, the other sources of this work listed in the References section were selected and analysed, and the results of the secondary research were synthesised.

The research was carried out through the Biostat company (Research and Development Centre in Rybnik).

The results of the overall survey (answers to the questions in the survey) were sent to Katarzyna Kowalska’s (the author of the survey) university e-mail address. Questions on cooperation were one of eight questions addressed to entrepreneurs in Section C in Poland.

The survey was conducted using the CATI method from 19 February to 26 April 2024. The target group was, private enterprises operating in Poland from section C [

Table 1].

The sampling was random and stratified, which also ensured that the survey was representative. The surveyed companies (200 companies located in Poland) were dominated by companies with Polish capital, employing up to 9 people (micro companies), companies running a sole proprietorship or a limited liability company, and companies with a long tradition of operating on the market (10 or more years) [

Table 1].

The sampling was randomised and stratified to ensure that the survey was representative. The sample size was calculated using the following parameters [

Table 1]:

In order to select the sampling frame, the GNI Hoovers database, which includes all companies registered with the CSO, was used. Only companies whose main activity profile was in line with section C of the survey were taken into account. Prior to randomisation, companies with discontinued operations and entities in liquidation or bankruptcy were excluded from the set. On the basis of such prepared data, a random draw was made with the use of a random number generator implemented in MS Excel, taking into account the section and size of employment, so that the number of entities selected for the study in each assumed quantitative element exceeded 10 times the number assumed in the sample. If the available entities were exhausted, additional ones were drawn from the identified frame. The response rate was 11.1%.

4. Results – Business to Business Cooperation on the Circular Economy, in Surveys

In today’s market environment, the cooperation of economic players plays a key role in terms of efficiency, effectiveness of operations. This is particularly reflected in the development strategies of companies whose competition takes place within supply chains (value chains). It can be said that competition nowadays takes place between groups (networks of companies) that are in a deliberate and purposeful relationship to each other. The network relationships of entities can be referred to different levels of cooperation (collaboration), also considered from the perspective of industries or even the entire economy [35], and can concern both the capital group (so-called network organisation – intra-organisational) as well as independent enterprises (enterprise network – inter-organisational network).

Networks of relationships exist and develop because of the motives of companies, which take the form of individual and shared goals. Effective feedback between companies determines the position of these companies in the market and ultimately the success of a given network. However, it should be noted that not all inter-organisational ties (interactions) between firms can be treated as networks; exchange, commitment and reciprocity are three obligatory attributes of relationships [34]. Exchange is relational in nature and fundamental to this process is the effective flow of information within the individual network links. In contrast, commitment in a networked relationship is multidimensional and should be reciprocal (operational, informational, social and investment commitment) – then it becomes an effective mechanism to safeguard against partner opportunism [34].

Resources and skills are a fundamental source of competition for networks of cooperating actors. These resources can be divided into active resources, which include technological and IT infrastructure, and intangible resources, which include the knowledge of employees and the image of specific actors. The latter also include organisational and cooperative culture, R&D facilities, information system and customer loyalty. The value of intangible resources is of particular importance to entities – as they can be used in different places at the same time, usually gaining in value. Their ownership is a key area of success – winning strategic partners and loyal customers is based precisely on the market value of these resources [37].

The above-mentioned network resources are in the form of assets whose value depends on their possession of durable (difficult to copy), unique and strategically oriented competences to manage them [41]. These competences are derived from the knowledge, skills and organisational experience of the managers and other employees of a given network. Such competences enable better or faster exploitation of opportunities and mitigation of risks arising in the environment. These include, among others, solving consumer problems in a unique way – adapted to new social needs, motivating and developing the qualifications of employees, creating and developing relationships with partners, the correct application of systems, e.g. in logistics, or the ability to anticipate and introduce necessary improvements in the operation of these systems. The case of the Biedronka chain is worth mentioning here, where errors in the application of the SAP system in logistics led to gaps in information and, as a result, a lack of continuity in the supply of shops [41].

Within the network structure of entities, there is a specific coordination mechanism in place, for which the lead entity is responsible [43]. The flagship company, usually the main commissioner of services, with strategic control over the network. The role of such an entity is to shape the relationships in the network arrangement. In practice, it can fulfil at least one of three roles: architect (bringing about the establishment of the rules of the system), gatekeeper (exercising oversight of the established rules), operator (coordinating activities to achieve the established goal) [35].

The specialisation of the companies and their close cooperation makes each of the network partners dependent for the benefits of the joint action. The emerging interdependencies between the actors determine the necessity for continuous coordination of activities and network links of the companies.

Synergy, the cooperative surplus of resource productivity, contributes to strengthening the competitive advantage of individual enterprises and ultimately constitutes the market power of a specific network of actors.

The essence of effective organisational networks presupposes relatively sustainable cooperation between partners based on set standards and values. Therefore, it is possible to reduce the network by entities that do not meet the established standards and to expand it by additional companies that have the appropriate resources and attributes [32,33].

The most important reference and justification for the network structure of companies should be the creation of value for the network entities themselves and their key stakeholders. The Creating Shared Value (CSV) concept points to such a goal and reference point. The creators of the concept, M. Porter and M. Kramer, define it as “operational procedures and practices that increase the competitiveness of a company and, at the same time, have a positive impact on the economic and social conditions of the people among whom that company operates. The production of economic and social value is a process aimed at identifying and extending the links between social development and economic progress” [39].

M. Porter and M. Kramer, based on their own consulting practice, have identified three possible CSV strategies that companies around the world are adopting [38,39]:

developing new markets by seeing the problems of local communities and developing innovative products to solve them;

redefining productivity in the value chain by introducing organisational and technological solutions to reduce negative environmental and/or social impacts. Most often, this comes down to optimising supply chains and building distribution networks based on local suppliers;

enabling the development of local clusters involving the creation and development of inclusive local networks built on resources and values, a shared vision and goals, and the development of technical infrastructure giving access to skills and knowledge.

The aforementioned strategies require the development of sustainable, committed collaboration and, as a result, the activation of one’s own and key stakeholders’ competitive potential to create shared value. This is linked to a greater ability to generate innovation – innovation competence and the drive to reduce costs, including transaction costs.

The realisation of the CSV concept is increasingly documented in the economic literature as examples of shared value creation practices among companies in the CE supply chain [24].

In this study, a survey conducted to identify behaviours related to the implementation of circular economy by manufacturing companies in Poland analysed the extent of their cooperation in the area of circular activities with their business partners/co-operators.

The survey was conducted using the CATI method from 19 February to 26 April 2024 [

Table 2]. The target group was private enterprises operating in Poland from section C. The sampling was random and stratified, which also ensured that the survey was representative. The surveyed companies (200 companies located in Poland) were dominated by companies with Polish capital, employing up to 9 people (micro companies), companies running a sole proprietorship or a limited liability company, and companies with a long-standing presence on the market (10 or more years).

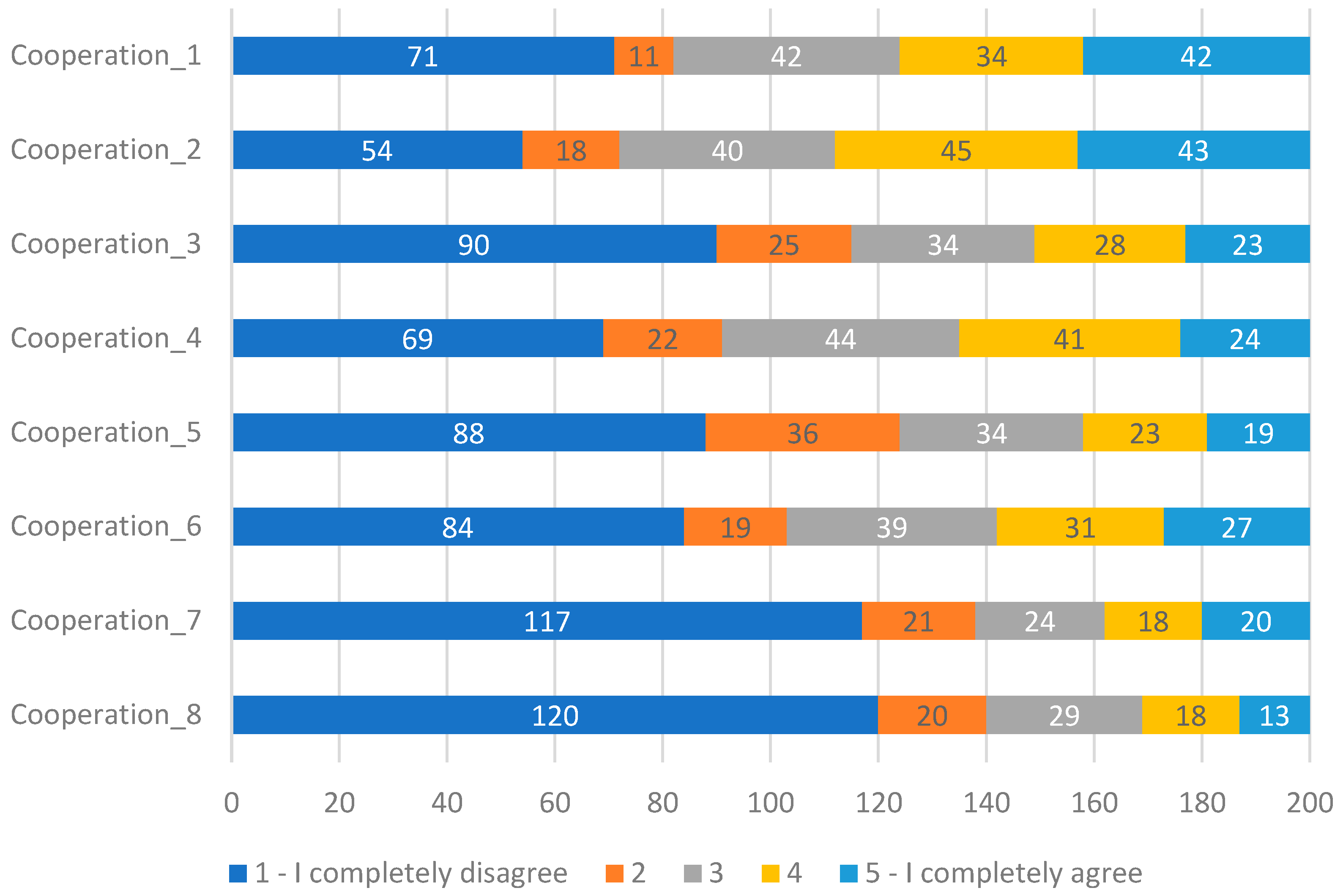

The survey analyzed forms of cooperation in circular activities with partners/cooperators of the surveyed enterprises. The analyzed forms of cooperation are:

W1 – common norms and standards of operation;

W2 – exchange of information;

W3 – joint training;

W4 – consulting;

W5 – exchange/sharing of equipment;

W6 – cooperation in acquiring new technological and innovative solutions (e.g. joint R&D expenditures);

W7 – consent of partners to unannounced internal audits;

W8 – consent of partners to unannounced external audits.

The survey used a five-point anchored scale 5 points anchored scale, in which extreme values were marked (1 – completely disagree, 5 – completely agree). This made it possible to examine the strength of the intensity of agreement with a given statement and allowed us to calculate a synthetic index of cooperation for each respondent, which was the average of the indications in each category [

Figure 1].

The largest share of responses was indicated by “1-I completely disagree” which meant the absence of cooperation in the forms analyzed. Among the surveyed enterprises, the lack of such cooperation was declared by, respectively:

cooperation 1 (common norms and standards of operation) – 36% of respondents;

cooperation 2 (exchange of information) – 27%;

cooperation 3 (joint training) – 45%;

cooperation 4 (consulting) – 35%;

cooperation 5 (exchange/sharing of equipment) – 44%;

cooperation 6 (cooperation in acquiring new technological and innovative solutions) – 42%;

cooperation 7 (partners’ agreement to unannounced internal audits) – 59%;

cooperation 8 (partners’ consent to unannounced external audits) – 69%.

Full declaration of cooperation in the aforementioned areas was indicated by respectively: 21% (common norms and standards of operation); 22% (exchange of information); 12% (joint training); 12% (consulting); 10% (exchange/sharing of equipment); 14% (cooperation in acquiring new technological and innovative solutions); 10% (agreement of partners to unannounced internal audits) and 7% (agreement of partners not to unannounced external audits). In the remaining cases, it can be concluded that the indicated scopes of cooperation were only partially implemented.

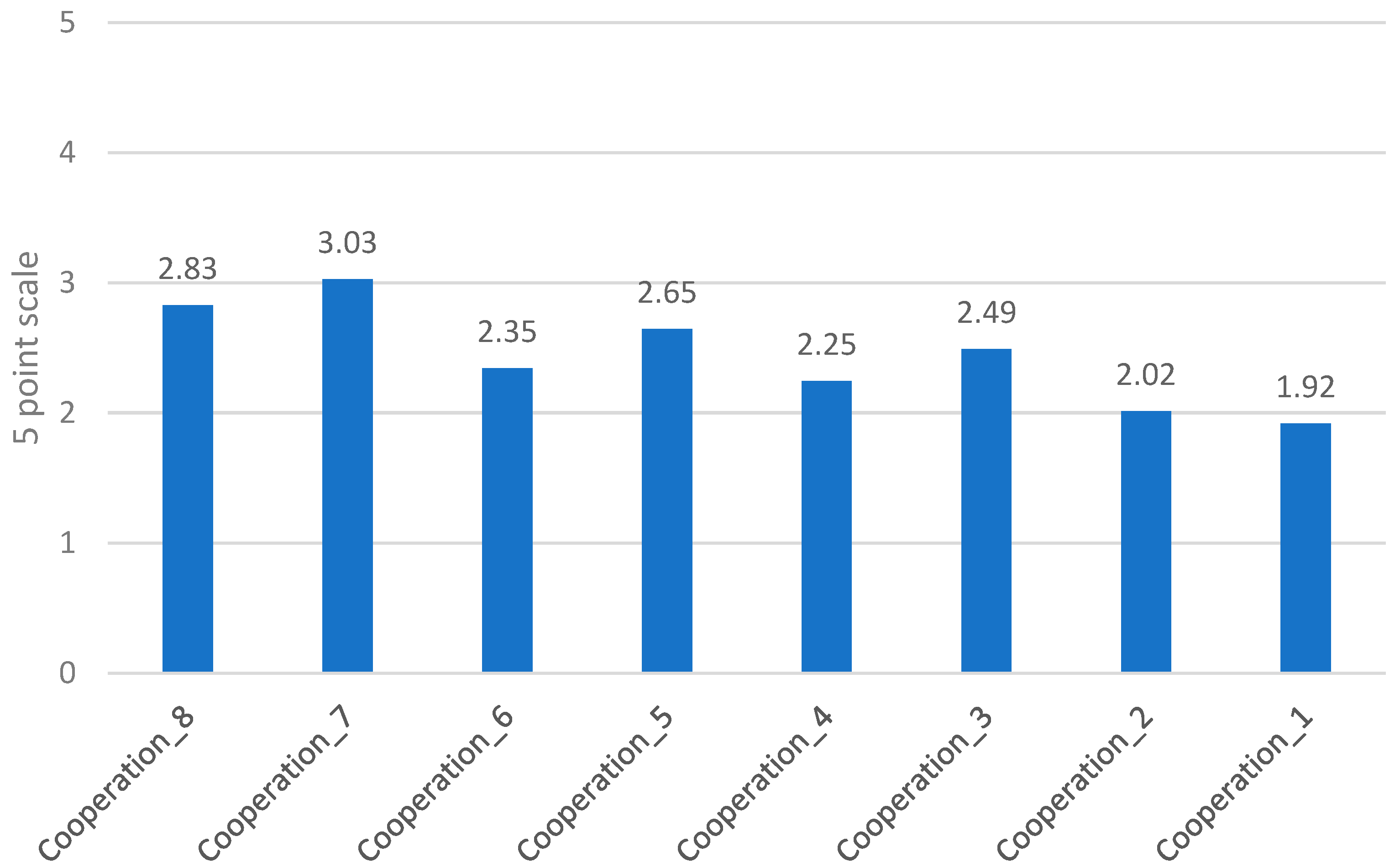

Based on the evaluation of the intensity of respondents’ compliance with a given form of cooperation, the average value was calculated for each form of cooperation (

Figure 2). The highest was found for the 2nd form of cooperation (3.03 – information exchange), which is one of the easiest forms to implement. The second highest (2.83) was for Form 1 – common norms and performance standards. The lowest score of average intensity was obtained for cooperation No. 8 (1.92) – partners’ agreement to unannounced external audits, which could be due to the lack of making such a proposal and the parties’ reluctance to control processes [

Figure 2].

The following also assesses the variation in the forms of cooperation between an enterprise and its business partners in relation to selected enterprise characteristics. For this purpose, non-parametric Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis H tests were used [

Table 3].

Based on the above data, statistically significant differences were found between the indications of the forms of cooperation used and the declared combination of business strategy and the idea of CE in the surveyed companies. Companies that declared the integration of the CE idea into their business strategy were statistically more likely to declare cooperation in the analyzed scopes.

Spearman rank correlation was used to analyze statements describing the strength of cooperation intensity by type.

From

Table 4, it can be seen that all variables are statistically significantly positively correlated with each other. In most cases, the correlation is average (0.3-0.5). In 9 cases – high (0.5-0.7) and in 4 cases – dvery high (0.7-0.9). In the latter case it can be stated:

the higher the declared undertaking of common norms and standards of operation, the higher the declared undertaking of information exchange;

the higher the declared undertaking of counseling the higher the declared undertaking of information exchange and joint training;

the higher the partners’ agreement to unannounced internal audits is declared, the higher the partners’ agreement not to unannounced external audits is declared.

The study also calculated the value of the synthetic cooperation index, which is the average value of the strength of the intensity of compliance with a given statement.

The average was calculated for each case (enterprise), so its analysis was possible only in the arrangement of the characteristics of the enterprises taken for analysis [

Table 5].

Based on the analysis, it can be concluded that the value of the cooperation index did not differ significantly either by the size of the enterprise, or by the form of operation, duration of operation or ownership of capital. However, a statistically significant difference was found between the value of the cooperation index and the declared integration of the CE idea into the company’s business strategies. For companies declaring the inclusion of the CE idea in their business strategy, the value of the cooperation index was higher (2.641) than for companies not declaring it (2.046).

This is one of the key findings of the study, which shows that the extent of CE cooperation depends on the approach of entrepreneurs to the CE concept itself and its integration into business practices. Responsible business concepts (CE is one of them) do not have to involve spending additional (or oversized) money, but should be closely linked to building competitive advantage and creating added value by stimulating innovation [40]. Achieving this goal requires embedding responsibility in the environmental and social spheres in the company’s development strategies. Otherwise, we have to deal with conducting temporary initiatives, often “detached” from the strategy, i.e. marketing campaigns, philanthropy, or charitable actions, and treating expenses for these purposes in the category of costs. Porter and Kramer argued in this regard that ad hoc social and environmental involvement in the form of sundry initiatives often means juxtaposing business and social goals and thus missing opportunities and market opportunities, making these activities ineffective [39].

The implementation of the CE concept in business supply chains additionally requires mutual dialogue, clearly defined goals of action and partnership in shared responsibility, searching for innovative solutions evaluated in a broader perspective and bringing benefits in the long term. As the research results presented in the paper show, cooperation in one area of business partners intensifies and encourages action in other areas, increasing the chances of achieving jointly agreed goals (e.g. cooperation on norms and standards of operation – assuming consistency of messages between declared values and action - will stimulate cooperation in other areas, such as in the exchange of knowledge and information). Thus, we are talking about appropriate management of relational capital with suppliers (B2B relationships), which is a strong catalyst for the development of innovation in supply chains. Involving suppliers in the co-creation of innovations (including in the area of CE) has a positive impact on the value and competitive advantage of those involved, increases the commitment and effects of the activities carried out [44,45].

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The structure of this part of the paper represents the conclusions of the theoretical and empirical research and relates directly to the research questions posed at the beginning of the paper.

CE is a key EU strategy supported by I4.0 [1] and a new emerging paradigm for sustainable development [2,3] and a key sustainability framework covering the global challenges of environmental degradation, waste management, resource depletion [4] and gas emissions [2]. CE is also a conscious, forward-looking, long-term, holistic approach, based on sustainability, vision and systemic transformation and disruptive innovation [5].

The essence of CE is explained by its objectives, which are defined as follows:

to restore the highest value and usability of materials, components and products [2,4];

to have a positive impact on the economy, the environment and global geopolitics [5,6] by moving from a linear economic model to a circular economy [7;

building a network of sustainability links between different stakeholders [8], oriented towards common sustainable goals, cooperation, synergies and scale effects, knowledge creation and exchange, R&D, IO, technological innovation, development of sustainable strategies and practices [3,7,9,10,11];

reducing: fossil fuel dependency (decarbonisation), resource consumption, de-waste (moving towards zero-waste production), gas emissions, energy leakage and environmental degradation [2,4,12,14,15,16,17,18], by slowing, narrowing and closing material and energy loops [19];

strengthening the energy security of countries and the security of NATO, the EU and the OECD [13];

restoring, restoring resilience, protecting and conserving the unique natural resources of ecosystems and prioritising the restoration of climate system stability [8,9], and strengthening the resilience of businesses, entrepreneurial ecosystems and the circular economy [16,20,21,22,23];

developing new sustainable consumption habits and patterns in societies [24].

Numerous multifaceted, synergistic and sustainable social, economic and environmental (environmental) benefits have been associated with the implementation of CE [4,6]. These benefits can be considered both at the scale of the economy and sustainably managed enterprises and include: increase in innovation and productivity of countries’ economies, significant material savings, reduction in operating and maintenance costs, reduction in resource-intensive production industries, improvement in the profitability of companies and increase in their resilience, creation of a positive image of producers applying extended responsibility, development of integrated value and supply chains, increase in efficient and profitable business models and networks, reduction in prices for customers, safe and stable environmental conditions, rapid macro-regional development, increase in social welfare [23,24].

CE inspired an increase in business efficiency. The benefits of CE were contingent on collaborative, industrial symbiosis in entrepreneurial ecosystems. The sustainability of a network of enterprises and their stakeholders required alignment between the values, goals and needs of its constituent partners [20].

The cooperation of companies has been important in shaping their competitive advantage in the market and in implementing circular activities in supply chains. Sustainable innovation significantly and positively enhances capabilities in circular activities of companies. According to the research, the collaboration of manufacturing companies with stakeholders in a network focused on closing circularity and sustainability resulted in the following benefits:

effective learning, flow of information, knowledge and best practices [11];

increased technical, organisational and business capabilities [11];

system improvements, process innovations, resource optimisation and waste reduction [11];

the emergence of network leaders with advanced digital technologies [11];

implementation of IOs that resulted in a culture of collaboration, sharing of expertise, skills development, access to and integration of technology, development of closed-loop products and processes, significant economic and technical performance, and the ability to pressure external stakeholders to leverage resources for CE initiatives [25];

sharing knowledge, risks and responsibilities in R&D consortia [8];

tracking and coordinating all stages of the product life cycle (design, production, use and disposal) [14], thus product traceability, informed decision-making, promoting transparency and sustainability and CE [26];

controlling the channels of product uptake, at the end of their life, and encouraging consumers to use the products for as long as possible [16];

implementing I4.0 and I5.0 technologies [15,27] and sustainability-oriented innovations [28] and making progress through e.g.: automation, virtualisation, flexibility and process optimisation, reduction of material and energy consumption, data collection and processing, production planning, monitoring, system failure prediction and decision-making [3];

achieving synergistic interaction between I4.0 technologies and LP practices enabling the implementation of CE strategies [10];

obtaining an increase in the impact of I4.0 on CE performance through: economies of scale, managerial support, operational efficiency and investment cost [29];

accelerate the implementation of CE in the producer supply chain by: involvement of top management, collaboration of different stakeholders, increase of knowledge and skills of employees [30];

support of companies in the sustainable management and development of CE by policy makers [31] and researchers [21].

The study found that (1) companies that declared the inclusion of CE in their business strategy were statistically more likely to declare cooperation in the scopes analysed; (2) cooperation in one area of business partners intensifies and encourages action in other areas, increasing the chances of achieving jointly agreed goals; (3) the implementation of CE in companies requires appropriate management of relationship capital – business to business (B2B), which is a strong catalyst for the development of innovation in supply chains. Involving suppliers in the co-creation of CE innovations through partnerships in different areas has a positive impact on the value and competitive advantage of these actors.

Business cooperation is crucial in the implementation and development of CE. In this context, there is an urgent need to define the type of relationship that exists between corporate strategy and the concept of CE. Activities undertaken by companies in the area of circular economy should be an integral part of the companies’ strategy (CE should be an element of the strategy). CE should be visible at every stage of the creation of a company’s strategy - starting with the vision and mission, which are the reference point for the created strategy, and ending with operational activities (Wołczek 2011, p. 283).

It is important to take into account the needs of the company’s stakeholders in the process of designing the strategy, as part of the strategic orientation of building shared value (CSV). Such an approach, conditioned by partnership and close cooperation between stakeholders, can (and often does) result in innovative solutions that reduce operating costs and other resources, minimize waste and increase efficiency in the use of materials. The superstructure of such a situation is not infrequently an improvement in reputation and corporate image, and ultimately the financial performance of the contracting company and its business partners.

The paper presents a survey in which responses from micro companies predominated. Micro companies often have less knowledge and experience of responsible business and the circular economy - the effectiveness of implementing these concepts and their benefits. This is evidenced, among other things, by the survey results in question, in which the largest share of responses was an indication denoting a lack of cooperation in the forms/areas analyzed (

Figure 1). This indicates an urgent need for education for CE, especially among micro and small enterprises. One of the programs, under the European Funds for Eastern Poland, supporting entrepreneurs may be an answer to this is the “Academy of Circular Transformation for Business”, organized by the Polish Academy for Enterprise Development (PARP). The program offers access to knowledge, tools and experts to help effectively implement CE solutions. However, it should be noted that this type of training (and not just competitions and subsidy programs for CE projects for small and medium-sized enterprises) should be widely implemented and available to a comparable extent throughout the country, bearing in mind that micro companies dominate the structure of enterprises throughout the country, as well as bearing in mind that the enterprises in question in Poland are characterized by significant resource (including human resource limitations) and time constraints, making it difficult to access up-to-date market knowledge, including in the area of CE.

Empirical research has been dedicated to the B2B sector. In line with current trends in the literature – it would be interesting to extend this research to include the cooperation of manufacturing companies with stakeholders other than supply chain companies. This is a limitation of the empirical part and at the same time – a future research direction. A strength of the research is its national coverage of Poland.

Acknowledgements

The publication was produced between 1 January 2025 and 12 May 2025 as part of the collaboration between the University of Pedagogy named after the Commission of National Education in Kraków (UKEN) and the Rzeszów University of Technology (PRz). The research was supported by the heads of the Department of Economics and Economic Policy (UKEN) and the Department of Enterprise Management. The survey was carried out as part of UKEN research project no. DNa.711.71.2023.PBU. The publication was financed from research projects: UKEN SDG LABS no. 2021-1-PL01-KA220-HED-000032077 and PRz no. PB56.RZ.25.001.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CE |

circular economy |

| B2B |

business to business |

| DfR |

design for repairability |

| DPP |

digital product passport |

| eDIM |

ease of disassembly metric |

| EU |

European Union |

| GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

| IoR |

index of repairability |

| I4.0 |

Industry 4.0 |

| I5.0 |

Industry 5.0 |

| LP |

lean production |

| OECD |

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| OI |

open innovation |

| PLM |

product lifecycle management |

| R&D |

research and development |

| RoD |

repair oriented design |

| RSS |

repair score system |

References

- Ciano, M. P.; Peron, M.; Panza, L.; Pozzi, R. Industry 4.0 technologies in support of circular Economy: A 10R-based integration framework. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2025, 201, 110867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.; Yanagisawa, H. The value of user-generated information exchange: Driving sustainability in peer-to-peer circular economies. Journal of Cleaner Production 2025, 491, 144811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagno, E.; Morioka, S. N.; Neri, A.; de Souza, E. L. Understanding how circular economy practices and digital technologies are adopted and interrelated: A broad empirical study in the manufacturing sector. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2025, 216, 108172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodislav, D. A.; Nițu, R. M.; Piroșcă, G. I.; Georgescu, R. I. The Opportunity Cost Between the Circular Economy and Economic Growth: Clustering the Approaches of European Union Member States. Sustainability 2025, 17(6), 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheel, C.; Aguiñaga, E. A. Systems View of Circular Economy. Sustainability 2025, 17(3), 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werf, L.; Colletis, G.; Negny, S.; Montastruc, L. Toward a generic method to help develop circular economy indicators. Journal of Cleaner Production 2025, 494, 144678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukyazici, D.; Quatraro, F. The skill requirements of the circular economy. Ecological Economics 2025, 232, 108559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrego-Viera, J. I.; Urbinati, A.; Lazzarotti, V. Transition towards circular economy: Exploiting open innovation for circular product development. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 2025, 10(2), 100668. 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Choy, Y. K.; Onuma, A.; Lee, K. E. The Nexus of Industrial–Urban Sustainability, the Circular Economy, and Climate–Ecosystem Resilience: A Synthesis. Sustainability 2025, 17(6), 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas, V. G.; Pozzi, R.; Saporiti, N.; Urbinati, A. Unveiling the interaction among circular economy, industry 4.0, and lean production: A multiple case study analysis and an empirically based framework—ScienceDirect. International Journal of Production Economics 2025, 282, 109537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambituuni, A.; Oyinlola, M.; Ajala, O.; Helen, S.; Esfahbodi, A.; Darrow, D. Mechanic Village Business Networks and Circular Economy Practices in the Automotive Industry. Business Strategy and the Environment 2025, 34(3), 3027–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipp, A.-M.; Lederer, J. The circular economy of packaging waste in Austria: An evaluation based on statistical entropy and material flow analysis. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2025, 217, 108193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincevica-Gaile, Z.; Zhylina, M.; Shishkin, A.; Ansone-Bertina, L.; Klavins, L.; Arbidans, L.; Dobkevica; L. , Zekker; I.; Klavins, M. Selected residual biomass valorization into pellets as a circular economy-supported end-of-waste. Cleaner Materials 2025, 15, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipaki, B.; Hosseini, Z. Repair-oriented design and manufacturing strategies for circular electronic products, from mass customization/standardization to scalable repair economy. Results in Engineering 2025, 25, 104169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, G.; D’Adamo, I.; Palmieri, R.; Serranti, S. Recycling-Oriented Characterization of Space Waste Through Clean Hyperspectral Imaging Technology in a Circular Economy Context. Clean Technologies 2025, 7(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Matsuoka, K.; Koide, R.; Shinojima, N.; Murakami, S. Regional sensitivity analysis to assess critical parameters in circular economy interventions: An application to the dynamic MFA model. Journal of Industrial Ecology 2025, 29(2), 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, P.; Shi, H.; Chertow, M. R. Resilience of the circular economy to global disruptions in scrap recycling. iScience 2025, 28(2), 111713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Opstal, W.; Pals, E.; Sangers, D. Mapping the prevalence and size of the informal circular economy in an industrialised region. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2025, 218, 108268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, S.; Giannoccaro, I. Dynamic Capabilities and Microfoundations to Overcome Barriers to Circular Economy Implementation. Business Strategy and the Environment 2025, 34(4), 4392–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, W.; Klofsten, M.; Bienkowska, D.; Audretsch, D. B.; Geissdoerfer, M. Orchestration in Mature Entrepreneurial Ecosystems Towards a Circular Economy: A Dynamic Capabilities Approach. Business Strategy and the Environment 2025, 34(4), 4747–4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D. Just circularities: Intersecting livelihoods, technology, and justice in just transition and circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production 2025, 500, 145176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Kumar Mangla, S. Investigating the Role of Smart and Resilient Supplier Management Practices in Circular Economy: A Supply Chain Practice View Perspective. Business Strategy and the Environment 2025, 34(4), 3919–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichini, T.; Salierno, G.; Strollo, N. M. An Expert-Based Analysis of ESG Reporting in the context of the Circular Economy. European Journal of Sustainable Development 2025, 14(1), 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciszewska, M.; Paca, D.; Patorska, J.; Pichola, I. Deloitte. Zamknięty obieg – otwarte możliwości. Raport przedstawiony na konferencji EEC Green towarzyszącej COP 24 (Deloitte. Closed loop - open opportunities. Report presented at the EEC Green conference accompanying COP 24), Polska, 2018, Deloitte: Warszawa; pp. 1–151.

- Ahmadov, T.; Durst, S.; Gerstlberger, W.; Nguyen, Q. M. Firm size as a moderator of stakeholder pressure and circular economy practices: Implications for economic and sustainability performance in SMEs. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C.; Silva, C. J.; Abreu, M. J. Circular Economy: Literature Review on the Implementation of the Digital Product Passport (DPP) in the Textile Industry. Sustainability 2025, 17(5), 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangju, W.; Batool, F.; Hussain, S.; Jabeen, M.; Ali, M.; Afzal, A. Impact of Industry 4.0 and 5.0 Technologies on Circular Economy and Sustainable Performance Using Hybrid PLS-SEM and ANN Approach. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2025, 1, 9920983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koval, V. ; Abramović; N., *!!! REPLACE !!!*, Đurović, S., Crvenica, D., Eds.; Arsawan, I. W. E. Fostering Technology Adoption and Management Advancements in Environmental Performance: Mediation of Circular Economy and Sustainability-Oriented Innovation. Sustainability 2025, 17(5), 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kandpal, V. Factors affecting the adoption of industry 4.0 technologies in circular economy: Interpretive structure modelling (ISM) approach for future sustainability. Discover Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Akash, M. H.; Aziz, R. A.; Karmaker, C. L.; Bari, A.; Kabir, K.; Islam, A. R. M. Investigating the attributes for implementing circular economy in the textile manufacturing supply chain: Implications for the triple bottom line of sustainability. Sustainable Horizons 2025, 14, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, I.; Osei, A.; Aboagye, R. A. Firms and the path to circular economy: Unveiling the impact of ownership dynamics and innovation capacity through advanced econometric and quantile regression analysis. Cogent Business & Management, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, A. Inwestycje zagraniczne. Składniki wartości i ocena (Foreign investment. Value components and assessment), Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsow, Poland, 2002; p. 122.

- Królikowski, M.; Yuan, X. Friend or foe: Customer-supplier relationships and innovation. Journal of Business Research 2017, 79, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czakon, W. Istota relacji sieciowych przedsiębiorstwa (The essence of a company’s network relationships). Przegląd Organizacji. [CrossRef]

- Dwojacki, P. Powstanie i funkcjonowanie sieci organizacyjnych (Establishment and functioning of organisational networks). Zeszyty Naukowe Towarzystwa Naukowego i Organizacji. Odział Wielkopolski 1995, 3, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- FOB, Tworzenie wartości wspólnej – przyszłość odpowiedzialności biznesu? [https://odpowiedzialnybiznes.pl/artykuly/tworzenie-wartosci-wspolnej-przyszlosc-odpowiedzialnosci-biznesu/?

- Kowalska, K. Rozwój polskich sieci detalicznych jako sposób ograniczania siły rynkowej międzynarodowych korporacji handlowych. Empiryczna weryfikacja na przykładzie województwa śląskiego (Development of Polish retail chains as a means of limiting the market power of multinational retail corporations. Empirical verification on the example of the Silesian Province), Difin: Warsow, Poland, 2012; p. 134.

- Mehera, A. R. Shared Value Literature Review: Implications for Future Research from Stakeholder and Social Perspective, 2017, Journal of Management and Sustainability, 2017, 7(4), 98–111. [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E.; Kramer, M. R. Creating Shared Value. Harvard Business Review, /: 62–77. [https, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. C.; Lenssen, G. Odpowiedzialność biznesu. Teoria i praktyka (Corporate Responsibility. Theory and practice), Wydawnictwo Studio EMKA: Warsow, Poland, 2009; pp. 24–25.

- Śmigielska, G. Kreowanie przewagi konkurencyjnej w handlu detalicznym (Creating competitive advantage in retailing), Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej w Krakowie: Krakow, Poland, 2007; pp. 104–196.

- Wołczek, P. Strategia a CSR (Strategy and CSR). Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu 2011, 156, 275–286. [Google Scholar]

- Perechuda, K. Zarządzanie przedsiębiorstwem przyszłości. Koncepcje, modele, metody (Managing the Enterprise of the Future. Concepts, models and methods), Agencja Wydawnicza Placet: Warsow, Poland, 2000; pp. 98–99.

- Ocicka, B. Wpływ zarządzania kapitałem relacji z dostawcami na rozwój innowacji w łańcuchach dostaw (Impact of supplier relationship capital management on the development of innovation in supply chains). Organizacja i Kierowanie, /: 101–116. [https, 4057. [Google Scholar]

- Wyrwich-Płotka, S. Zależności partnerskiej współpracy i poziomu dojrzałości łańcucha dostaw w warunkach globalizacji (Relationships of partnership cooperation and the level of supply chain maturity in terms of globalization), Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu 2018, 505, 155–156. 505. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).