1. Introduction

The introduction of alloplastic materials such as methyl methacrylate in the surgical industry has significantly changed the treatment of patients with bone defects [

1]. Although methyl methacrylate is a material commonly used for the reconstruction of neurocranial (calvarial) and orthopedic defects, it has only recently found its application in the field of maxillofacial surgery. While there is significantly more data in the literature on bone reconstruction in the field of neurosurgery and orthopedics, information on reconstructions in the field of viscelocranium is almost non-existent in the literature. This is not surprising considering that the common materials used for 3D reconstruction of viscelocranium bone are titanium, PEEK and grafts.

Although it is traditionally assumed that the most desirable replacement for defective tissue is fresh autogenous tissue [

2], such a solution has numerous disadvantages. In addition to the limited availability of such tissue, the demanding surgical procedure to harvest the graft (and others), a particular problem is the design of such a graft in accordance with the specific characteristics of the target tissue. This is particularly emphasized in the field of maxillofacial surgery and defects of the mandible, a bone with a specific (irregular) appearance and shape. In this sense, the need for inorganic implants (solutions) is not surprising, and one of these solutions is methyl methacrylate.

2. Materials and Methods

After careful planning, a unique procedure to reconstruct the lower jaw - part of the lower jaw - using alloplastic material (methyl methacrylate) with the support of 3D technology was performed in collaboration with experts in 3D technology. The procedure was performed on a patient (a 57-year-old man) who has suffered from fibrous dysplasia of a large part of the lower jaw since childhood (he associates it with a blow from a horse). Although he had no major problems other than swelling at an earlier age, the patient has been hospitalised several times in recent years for numerous problems and has undergone more than 30 examinations. Due to the almost disintegrated mandible (Figures 1, 2, 3), frequent pain, swelling, abscesses, fistulas (in the area of the lesion) and impending fractures, it was decided to surgically remove the diseased part of the mandible and replace it with alloplastic material, in this case methyl methacrylate. After several hours of surgery, the patient was implanted with a new part of the mandible made of acrylic polymer. The functional and aesthetic condition was very satisfactory for several years.

Figure 1.

Orthopan of a severely damaged corpus and ramus of the mandible.

Figure 1.

Orthopan of a severely damaged corpus and ramus of the mandible.

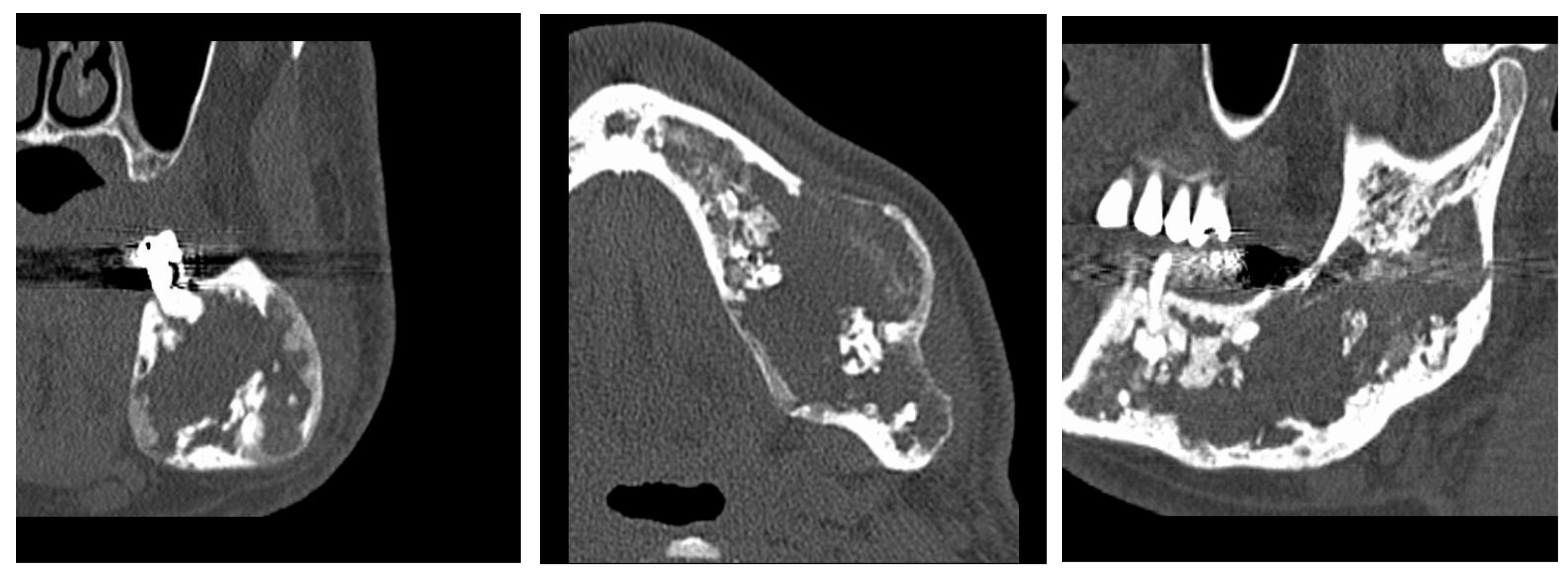

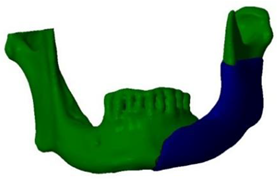

Figure 2.

A lesion that destroys almost half of the mandible.

Figure 2.

A lesion that destroys almost half of the mandible.

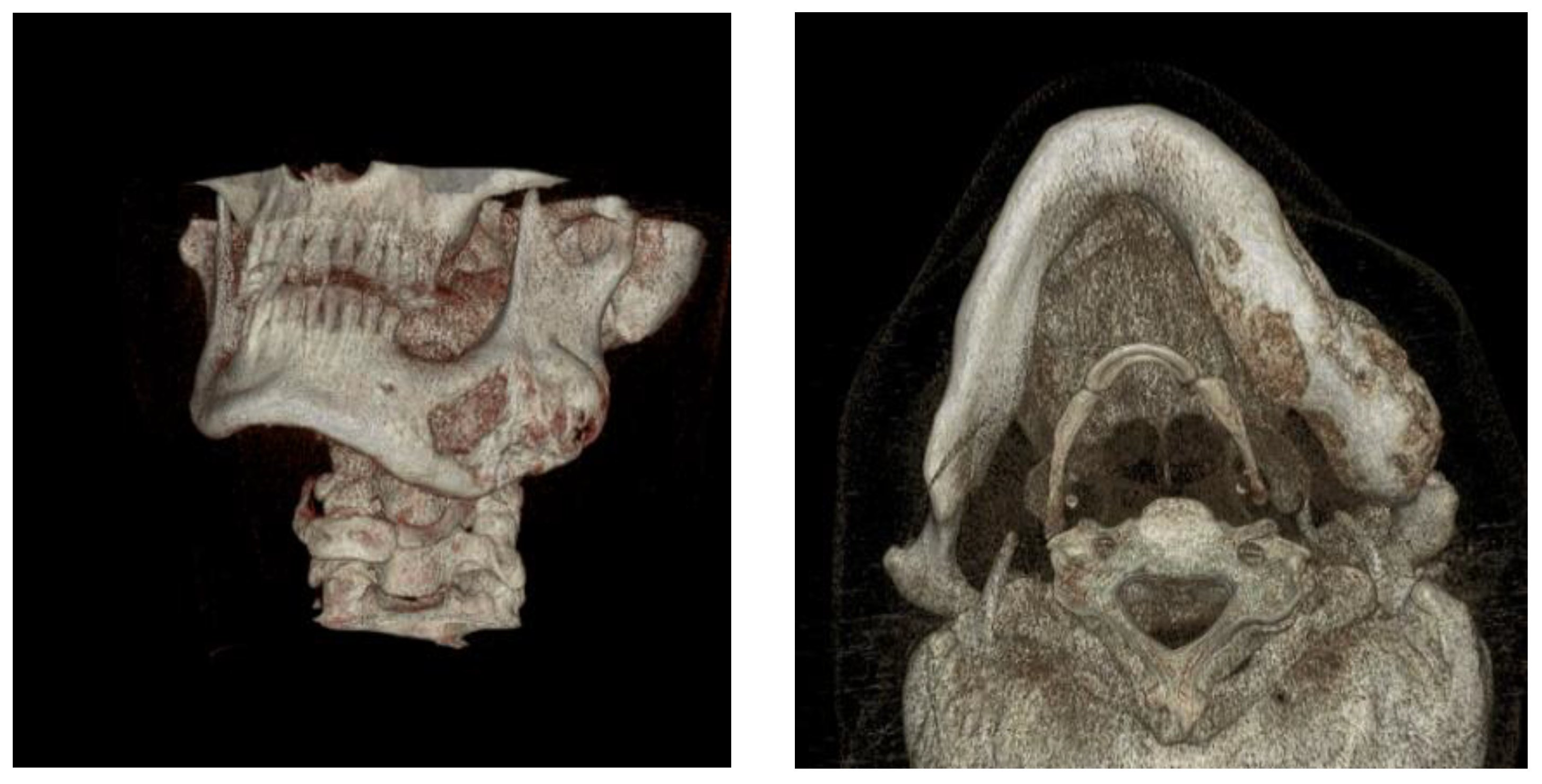

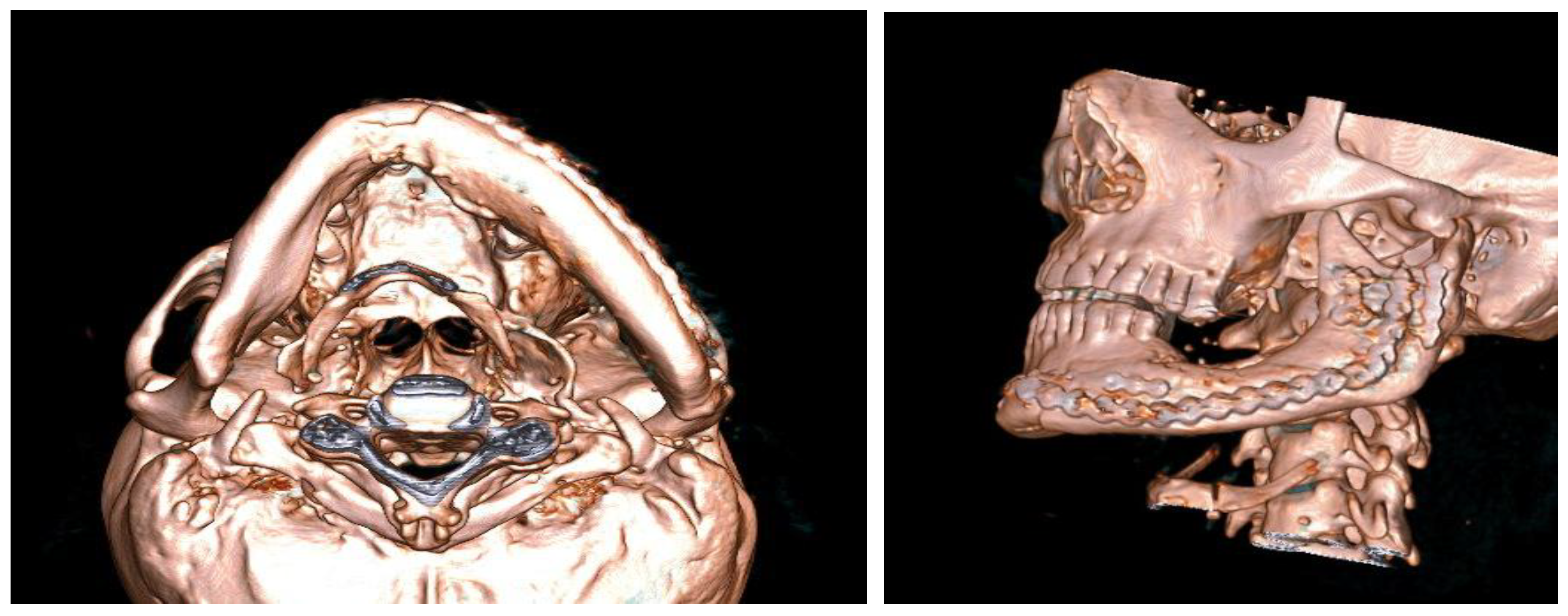

Figure 3.

Progressive swelling of the body and ramus of the mandible - MSCT 3D reconstruction.

Figure 3.

Progressive swelling of the body and ramus of the mandible - MSCT 3D reconstruction.

2.1. Materials

After a biopsy, the mandibular lesion (which the patient had) was found to be a monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the mandible, in which bone tissue has been replaced by fibrous tissue. This is a benign condition that can turn malignant.

As the patient’s problems were very frequent, an operation was performed to remove a large part of the altered tissue of the lower jaw.

In this first procedure, no segmental resection of the mandible was performed, but only the extirpation of the inflammatory masses and a partial reduction of the formation (

Figure 4).

As the disorders persisted despite the reduction in size of the formation, it was obvious that a segmental resection had to be performed. Previously, the patient’s teeth were devitalized near the resection of the mandible, as he complained of pain in some of the adjacent teeth.

Since the lesion took up almost half of the lower jaw, reconstruction is required after the removal of such a large lesion. The standard reconstruction procedures for such large defects of the mandible are reconstructions with free flaps, such as the free fibular flap or the iliac crest flap, while reconstruction of smaller bone defects can be achieved with bone grafts or osteogenic distraction techniques.

In this particular case, given the size of the bone defect, reconstruction with bone graft alone was not possible, but with a combination of alloplastic material and autologous bone, using the possibilities of 3D technology in the planning. The material used in the operation is methyl methacrylate, which is frequently used in neurosurgery for the reconstruction of cranial defects [

3] and in orthopedics [

4].

Methyl methacrylate - the acrylate polymer methyl methacrylate (PMMA) - is a clear, light yet tough material. It is resistant to external influences and has a high impact strength. It is known for its excellent strength and toughness, making it an ideal material for the manufacture of components and parts that need to be robust. It is easy to cut and shape. It is a porous composite material used in medicine as a bone cement with biocompatibility and high ingrowth properties [

5,

6,

7].

2.2. Methods

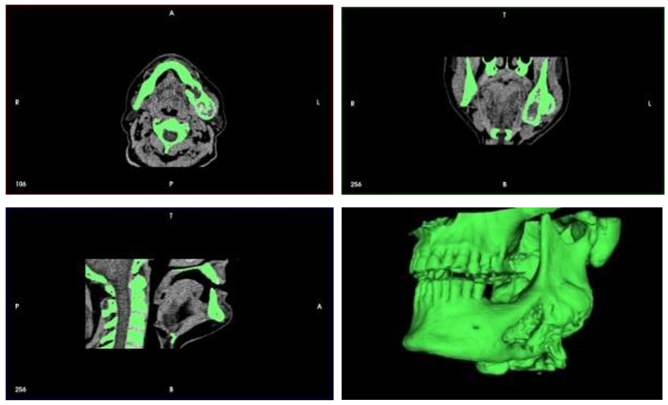

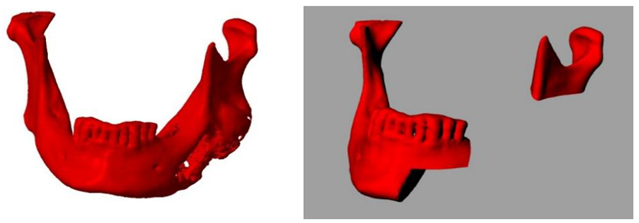

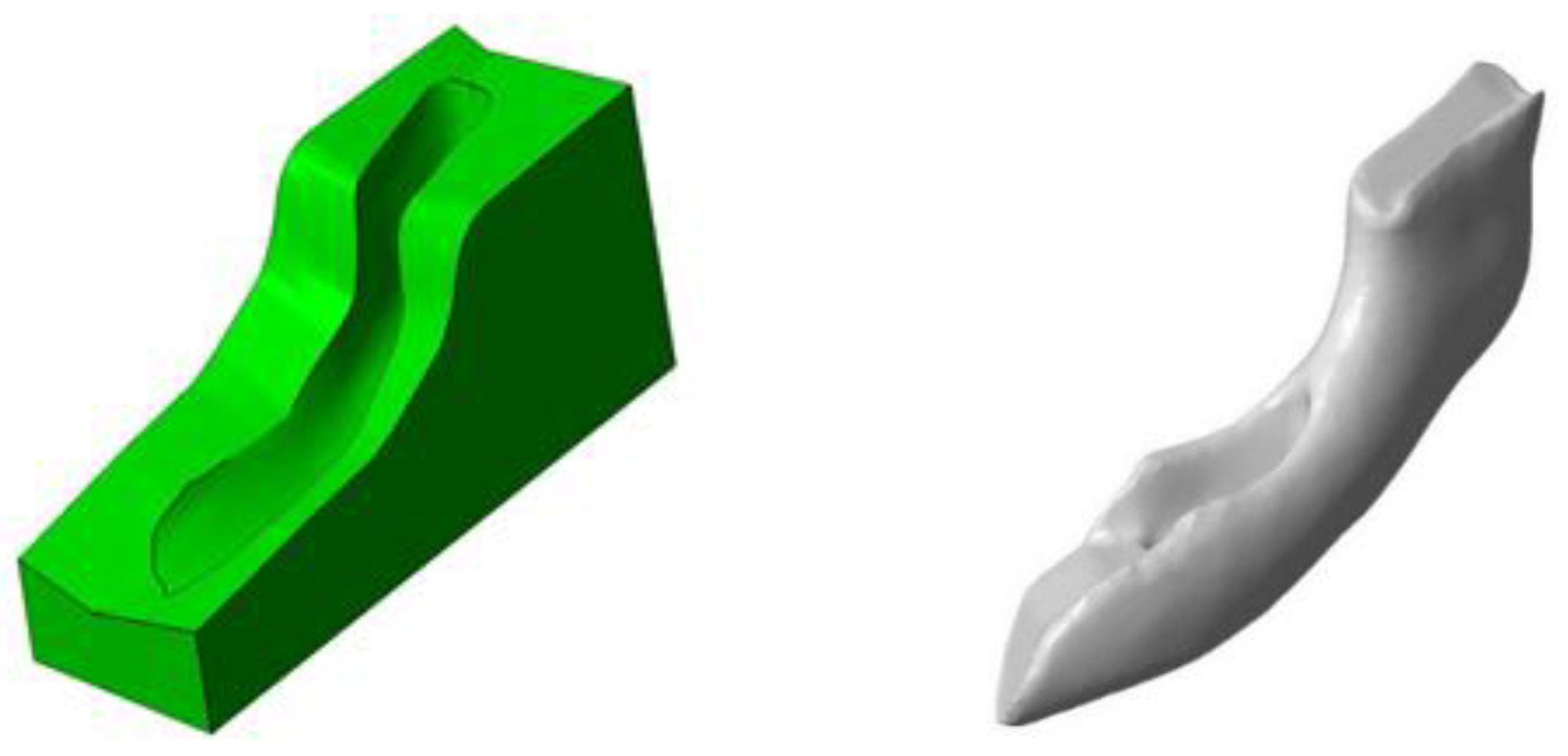

As methyl methacrylate is a material that cannot be 3D printed directly, a complete process for forming a 3D implant was developed in collaboration with experts in 3D technology, taking into account all the special features of this material.

A CT scan of the mandible was converted into a 3D computer model and a mold for forming a methyl methacrylate implant was created using additive printing technology.

The idea was to print a precisely shaped mold using the capabilities of additive technology and then cast a methyl methacrylate implant into this mold (

Figure 5).

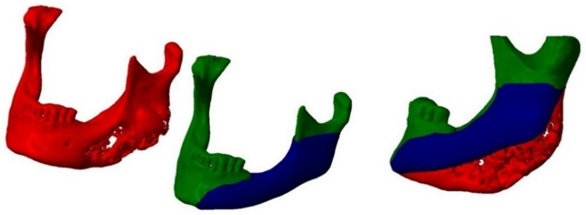

Figure 5.

Shaping of implants with methyl methacrylate with the help of 3D technology (in stages).

Figure 5.

Shaping of implants with methyl methacrylate with the help of 3D technology (in stages).

The mold into which the implant material was poured consisted of seven parts so that the implant could be removed more easily from the mold and the reconstruction of the mandibular defect could be performed (

Figure 6).

Using 3D printing technology, a model of the mandible was printed on which the resection margins were marked (

Figure 7). A 3D-printed template was also produced and used during the procedure (

Figure 8, right).

During the virtual surgical planning phase, the neo mandible was designed using the mirroring technique of the healthy side of the mandible, which enables precise reconstruction of functional and aesthetic symmetry. According to previous studies, the mirroring technique enables high precision in simulated mandibular reconstructions with an average RMS deviation of less than 1 mm [

8].

Previous studies have shown that the use of 3D models, based on mirroring the healthy side of the mandible, leads to a higher accuracy of the anatomical reconstruction, i.e. a better morphological fit of the reconstructed structures. This technique lays the foundation for personalised surgery and precision medicine in the reconstruction of the mandible [

9,

10,

11].

3. Results

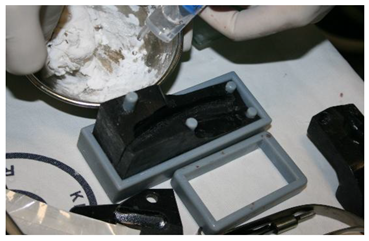

After the diseased part of the jaw was removed, it was replaced with a methyl methacrylate implant. Since methyl methacrylate is a material that cannot be printed directly, but is a two-component material (a clear colorless liquid and a powder) that hardens after mixing, a 3D-printed mold was created in which the material hardened to obtain the desired implant with exact specifications. The process is more challenging as methyl methacrylate was used with an antibiotic and had to be poured during the surgical procedure itself (

Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Implant formation using methyl methacrylate during surgery (in stages).

Figure 11.

Implant formation using methyl methacrylate during surgery (in stages).

The methyl methacrylate implant was fixed with osteosynthetic material - miniplates and reconstruction plates (

Figure 12), i.e. two types of plates, because we wanted to achieve a more secure contact between the bone and the implant.

We used an iliac crest bone graft (

Figure 13), and the "hollow" of the implant was filled with bone meal (

Figure 14). A bone graft from the iliac crest was implanted in anticipation of future implant-prosthetic rehabilitation.

PRF (platelet-rich fibrin) membranes were used at the end of the surgical procedure to promote tissue regeneration and enhance wound healing (

Figure 15).

Although there were minor deviations from the virtual plan during the surgical procedure, the consistency of performance with subsequent radiographs was not assessed. Given that the postoperative clinical findings were normal, with no signs of complications, additional radiological verification was not indicated.

The postoperative course went smoothly and the patient had a very good aesthetic and functional result with a very satisfactory quality of life over the next few years. The methyl methacrylate implant was very stable clinically and on radiographs (

Figure 16 and

Figure 17).

Almost two years after reconstruction of the mandible, the patient developed an infection due to odontogenic inflammation in the immediate vicinity of the surgical procedure. The inflammation was treated with antibiotic therapy but could not be completely suppressed until the reconstruction material was (finally) removed. Due to the infection, the acrylic implant was removed (only a large reconstruction plate was temporarily inserted) and the patient was recommended a mandibular reconstruction with a free fibular flap. Later, no further procedures were performed as the patient was satisfied with the functional (bite, speech, swallowing) and aesthetic result achieved.

4. Discussion

Segmental resection of the mandible leads to a severe functional and aesthetic deficit in patients [

12]. As the mandible is the only mobile bone in the head, its functional role is very important. It is involved in speech, breathing and food intake. The missing part of the mandible therefore requires reconstruction, which can be a major surgical challenge. The usual methods for reconstructing larger mandibular defects are the use of free microvascular flaps (free fibular flap or iliac crest flap) [

13,

14], while smaller defects can be reconstructed with bone grafts or osseogenetic distraction [

15,

16].

In the last (two) dozen years there have been attempts to replace part or all of the mandible with alloplastic materials. The development of 3D technologies, which have found their application in medicine, certainly contributes to this. In the case of mandibular reconstruction, this mainly refers to the possibilities of 3D printing of alloplastic materials [

17,

18]. The materials that can be printed and are highly biocompatible are titanium and PEEK, which are most commonly used in mandibular reconstruction [

19]. The biocompatible material routinely used for the reconstruction of parts of the neurocranium is methyl methacrylate, about which there is an extensive body of information in the literature. On the other hand, there is very little information in the literature on bone reconstructions of the viscerocranium and mandible with the same alloplastic material [

20], so studies aimed at better understanding the clinical indications, complications and the possibility of using this material in maxillofacial reconstructive surgery (such as this one) fill this gap in the literature.

The fixation of methyl methacrylate implants in craniofacial surgery is essential to ensure the stability of the implant in reconstructive defects. The use of fixation plates enables long-term integration of the material into the surrounding tissue and prevents movement of the implant during the rehabilitation process. Although there is insufficient evidence in the literature to support the simultaneous use of mini plates and standard reconstructive plates in the same procedure (as is the case here), a combination of mini and standard plates may be warranted in complex reconstructions to achieve optimal stability and healing. There are different approaches to fixation in mandibular reconstruction, and the choice between mini and standard plates often depends on the specifics of the case and the surgeon’s clinical judgment. The available studies comparing mini and standard plates in mandibular reconstruction show mixed results. While some studies suggest that there is no significant difference in the complication rate between grafts fixed with miniplates (27%) and those fixed with standard plates (30%) [

21], other studies suggest that standard plates better maintain the accuracy of the condylar position, while miniplates have a better bone healing rate after 6 months [

22], suggesting the advantages of their combination.

In addition to the already highlighted advantages of methyl methacrylate as a suitable material for filling bone defects in the mandible, its additional advantage (which is often decisive for its choice) is its significantly lower price (compared to more expensive alternatives), which makes it a more accessible option in clinical practice. Equipment that can print molds for casting methyl methacrylate implants is much more widely available and cheaper than equipment for printing titanium or PEEK; moreover, methyl methacrylate itself is significantly more cost-effective than titanium or PEEK. The aforementioned was also an important criterion when selecting materials for the reconstruction of mandibular defects described in this study, taking into account the specific limitations of this material when making clinical decisions (they are prone to infection and biofilm formation, they are avascular and do not integrate with the surrounding tissue, they do not allow osseointegration, they are mechanically less resistant, and others).

As confirmed by the results of the surgery presented in this paper, the risk of using the aforementioned material lies in its porosity, and any inflammation (caused by infection in the environment) leads to its soaking and, in this case, is difficult to resolve [

23,

24,

25]. Given the fact that (in this particular case) the infection occurred almost two years after the devitalization of the teeth (in close proximity to the resection of the mandible), the likelihood of this being the reason for the infection and jeopardising the overall outcome is low. According to the literature, infections after such surgical procedures can occur due to various factors, including surgical complications, the quality of postoperative care and specific characteristics of the implant [

26,

27]. Although in this case considerable time has passed since the procedure and there were no significant periodontal changes, we still associate the mentioned infection with the teeth. Since alloplastic materials (such as methyl methacrylate) are naturally non-vascularized and (in the case of bacterial colonization) antibiotics often cannot penetrate the biofilm in sufficient concentrations, the removal of the infected material is recommended in the literature as the gold standard for the treatment of such infections. Removal of infected non-biological material is not only recommended, but is often an unavoidable approach to finally resolve the infection [

28]. The literature confirms that most problems are solved by removing the infected material, after which the bone (usually) heals well [

29].

Although the placement of dental implants was originally planned after bone grafting from the iliac crest and its incorporation into the "hollow" of the methyl methacrylate implant, implant-prosthetic rehabilitation was not carried out due to complications. In order to ensure the best possible result for the patient, it was decided to wait longer (almost two years) before carrying out further procedures. In the meantime, complications occurred and as the patient was satisfied with the result achieved, no further procedures were performed. Although the standard waiting time after autologous bone reconstruction (before placement of dental implants) is 3-6 months [

30] and 3-8 months [

31], there are situations where a longer waiting time is warranted to ensure a safe and predictable outcome. A longer waiting time may be justified based on the individual assessment of the patient, the need for complete osseointegration and stabilisation of the graft, and the timely detection and prevention of potential complications. In cases where the patient is functionally and aesthetically satisfied, it may also lead to further surgery being avoided [

32].

There is no ideal method to correct the described mandibular defect. Each method advocated has its advantages and disadvantages. This paper presents reconstruction with alloplastic material (methyl methacrylate), discussing both the problems and challenges encountered in reconstructing mandibular defects with such substitutes, as well as the arguments supporting their application [

33].

5. Conclusion

In addition to the use of free microvascular flaps, larger defects of the mandible can also be reconstructed with alloplastic material, with which a significantly better shape of the missing bone part can be achieved. This is mainly made possible by the development of 3D technology and the possibility of additive printing. Excellent results are achieved with titanium and PEEK, but given its biocompatibility and high ingrowth capacity, methyl methacrylate is a very high-quality and much cheaper substitute. The porosity of this material (on the other hand) is its main disadvantage and there is a high probability of failure in case of infection.

Reconstruction of the mandible is still a challenge for oral and maxillofacial surgeons. Reconstruction with a microvascular flap is considered the gold standard, especially in the resection of malignant tumors followed by radiochemotherapy, which was not the case here. The second line is the prefabricated composite flap, autologous graft and alloplastic CAD-CAM prosthesis made of titanium. However, there are other solutions that are significantly cheaper and (therefore) more accessible, such as the one described in the study. Each solution has advantages and disadvantages.

It is planned to (further) search for alternative methods and safer solutions to the problem described, and the use of methyl methacrylate is one such attempt.

References

- Govila, A. Use of methyl methacrylate in bone reconstruction. British Journal of Plastic Surgery, 1990; 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, R.C. Facial Injuries. 3th edition. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers. January 1988.

- Velnar, T.; Bosnjak, R.; Gradisnik, L. Clinical Applications of Poly-Methyl-Methacrylate in Neurosurgery: The In Vivo Cranial Bone Reconstruction. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanathan, S.; Lin, Y.C.; Thirumurugan, S.; Hu, C.C.; Duann, Y.F.; Chung, R.J. Poly (methyl methacrylate) in Orthopedics: Strategies, Challenges, and Prospects in Bone Tissue Engineering. Polymers. 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Chen, H.; Huang, L.; Dong, J.; Guo. D.; Mao, M.; Kong, L.; Li, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lei, W. Porous surface modified bioactive bone cement for enhanced bone bonding. PLoS One. 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevanzadeh, F.; Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Hamzah, E. In-vitro biocompatibility, bioactivity, and mechanical strength of PMMA-PCL polymer containing fluorapatite and graphene oxide bone cements. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 2018, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, M.S. Prosthodontic Applications of Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA): An Update. Polymers. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.C.; Chan, H.H.L.; Jozaghi, Y.; Goldstein, D.P.; Irish, J.C. Analysis of Simulated Mandibular Reconstruction Using a Segmental Mirroring Technique. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery, 2019; 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Fang, J.J.; Chang, L.R.; Yu, C.K. Mandibular Defect Reconstruction with the Help of Mirror Imaging Coupled with Laser Stereolithographic Modeling Technique. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2007, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, P.L.; Nelson, J.A.; Rosen, E.B.; Allen, R.J.; Disa, J.J.; Matros, E. Virtual Surgical Planning for Oncologic Mandibular and Maxillary Reconstruction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery - Global Open, 2021; 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranix, J.T.; Stern, C.S.; Rensberger, M.; Ganly, I.; Boyle, J.O.; Allen, R.J.; Disa, J.J.; Mehrara, B.J.; Garfein, E.S.; Matros, E. A Virtual Surgical Planning Algorithm for Delayed Maxillomandibular Reconstruction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2019, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.; Singhavi, H.R.; Mestry, V.; Shetty, R.; Joshi, P.; Chaturvedi, P. Marginal Mandibulectomy in Oral Cavity Cancers - Classification and Indications. Indian Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shenaq, S.M.; Klebuc, M.J.A. The Iliac Crest Microsurgical Free Flap in Mandibular Reconstruction. Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 1994, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lech, D.; Matysek, J.; Maksymowicz, R.; Strączek, C.; Marguła, R.; Krakowczyk, Ł.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Dowgierd, K. Maxillofacial Microvascular Free-Flap Reconstructions in Pediatric and Young Adult Patients - Outcomes and Potential Factors Influencing Success Rate. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Jiang, X.; Huang, X. Distraction osteogenesis application in bone defect caused by osteomyelitis following mandibular fracture surgery: a case report and literature review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M.S.; Baughman, D.G. Reconstruction of severe anterior maxillary defects using distraction osteogenesis, bone grafts, and implants. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2005, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercuri, L.G. Alloplastic temporomandibular joint replacement - what does the future hold? Frontiers of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine. 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Roychoudhury, A.; Kumar, R.D.; Bhutia, O.; Bhutia, T.; Aggarwal, B. Total Alloplastic Temporomandibular Joint Replacement. Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery. 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Gao, L.; Cui, H.; Guo, X.; Han, J.; Liu, J.; Yao, Y. Finite element comparison of titanium and polyetheretherketone materials for mandibular defect reconstruction. American Journal of Translational Research. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodger, N.M.; Wang, J.; Smagalski, G.W.; Hepworth, B. Methylmethacrylate as a space maintainer in mandibular reconstruction. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2005, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.J.; Kanatas, A.N.; Lowe, D.; Brown, J.S.; Rogers, S.N.; Vaughan, E.D. Comparison of miniplates and reconstruction plates in mandibular reconstruction. Head & Neck, 2004; 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Bai, J.; Guo, S.; Shang, Z.; Shao, Z. Comparison of reconstruction plates and miniplates in mandibular defect reconstruction with free iliac flap. Clinical Oral Investigations. 2024, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henslee, A.M.; Spicer, P.; Shah, S.; Tatara, A.M. Use of Porous Space Maintainers in Staged Mandibular Reconstruction. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 2014, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggat, P.A.; Smith, D.R.; Kedjarune, U. Surgical applications of methyl methacrylate: a review of toxicity. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health, 2009; 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorano-Fernandes, L.; Rodrigues, N.C.; Bezerra, N.V.F.; Borges, M.H.S.; Cavalcanti, Y.W.; Almeida, L.F.D. Cinnamaldehyde and α-terpineol as an alternative for using as denture cleansers: antifungal activity and acrylic resin color stability. Research, Society and Development. 2021; 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwarcinski, J.; Boughton, P.; Ruys, A.; Doolan, A.; Van Gelder, J. Cranioplasty and Craniofacial Reconstruction: A Review of Implant Material, Manufacturing Method and Infection Risk. Applied Sciences. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.K.; Weng, H.H.; Yang, J.T.; Lee, M.H.; Wang, T.C.; Chang, C.N. Factors affecting graft infection after cranioplasty. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2008, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerli, W.; Trampuz, A.; Ochsner, P.E. Prosthetic-joint infections. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, K.E.; Desmond, R.; Magnuson, J.S.; Carroll, W. R.; Rosenthal, E. L. Hardware removal after osseous free flap reconstruction. Otolaryngology Head Neck Surgery. 2014, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misch, C.M. Autogenous bone: Is it still the gold standard? Implant Dentistry. 2010, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiapasco M, Casentini P, Zaniboni M. Bone augmentation procedures in implant dentistry. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofac Implants. 1988; 24. [PubMed]

- Peitsinis, P.R.; Blouchou, A.; Chatzopoulos, G.S.; Vouros, I.D. Optimizing Implant Placement Timing and Loading Protocols for Successful Functional and Esthetic Outcomes: A Narrative Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.C.W.; Loh, J.; Islam, I. Alloplastic Reconstruction of the Mandible - Where Are We Now? IFMBE proceedings, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).