1. Introduction

This article will focus on some industrial and societal perspectives of metrological traceability:

Section 2 will define our understanding of metrological traceability; section 3 explains why metrological traceability is indispensable for industry and society. Chapters 4 and 5 illuminate the concept of the traceability chain and chapter 6 discusses the findings. Consequently, chapters 7 and 8 critically analyze the present definition of metrological traceability adding a historical perspective. Chapter 9 summarizes the conclusions.

2. What Is Metrological Traceability?

Metrological Traceability is a property of a measurement result. It is the effect and outcome of a measurement process. Metrological traceability means that a measurement result

M has a certain relationship to a reference

r. This reference could, for instance, – but not necessarily – be a defined SI unit. The relationship is expressed by a pair of numbers: One is the factor

m that relates the measurement value to the reference. The other one is a statistical parameter

u that describes an interval which is usually symmetrical around the result value and has an associated probability and in which the true value of the measurand is to be found with a certain likelihood. This pair can (although not frequently noted this way) be depicted as a two-dimensional vector, see equation (1):

This vector can be called the "metrological traceability information of M with reference to r".

3. Why Do We Need Metrological Traceability?

Metrological Traceability is, the prerequisite for metrological comparability. Comparability is an important concept: Many people in science and economy and in everyday life make unknowingly use of comparability and thus rely on metrological traceability being present. There are a few key situations in which comparability is indispensable.

3.1. Situation 1: Comparing a Measurement Result to Another Measurement Result

This situation occurs in a number of variations:

- a)

Comparing measurement results of the same measurand: The measurement results of the same property might have been made with two different procedures (e.g. for validating a new procedure), or two different sets of equipment (e.g. as a means of qualifying new equipment or as a quality assurance measure) or by different laboratories (e.g. intercomparisons) or by different personnel (e.g. as a quality assurance measure).

- b)

Comparing measurement results to a "reference value". This is the case e.g. for laboratory intercomparisons or for quality assurance against a check standard or against a reference material [

1] (section 7.7.1).

- c)

Comparing measurement results to historical values of the same measurand. A interesting example is the climate change. Without comparability of the results of the past decades and centuries, the hypotheses that the climate has changed, could not be confirmed.

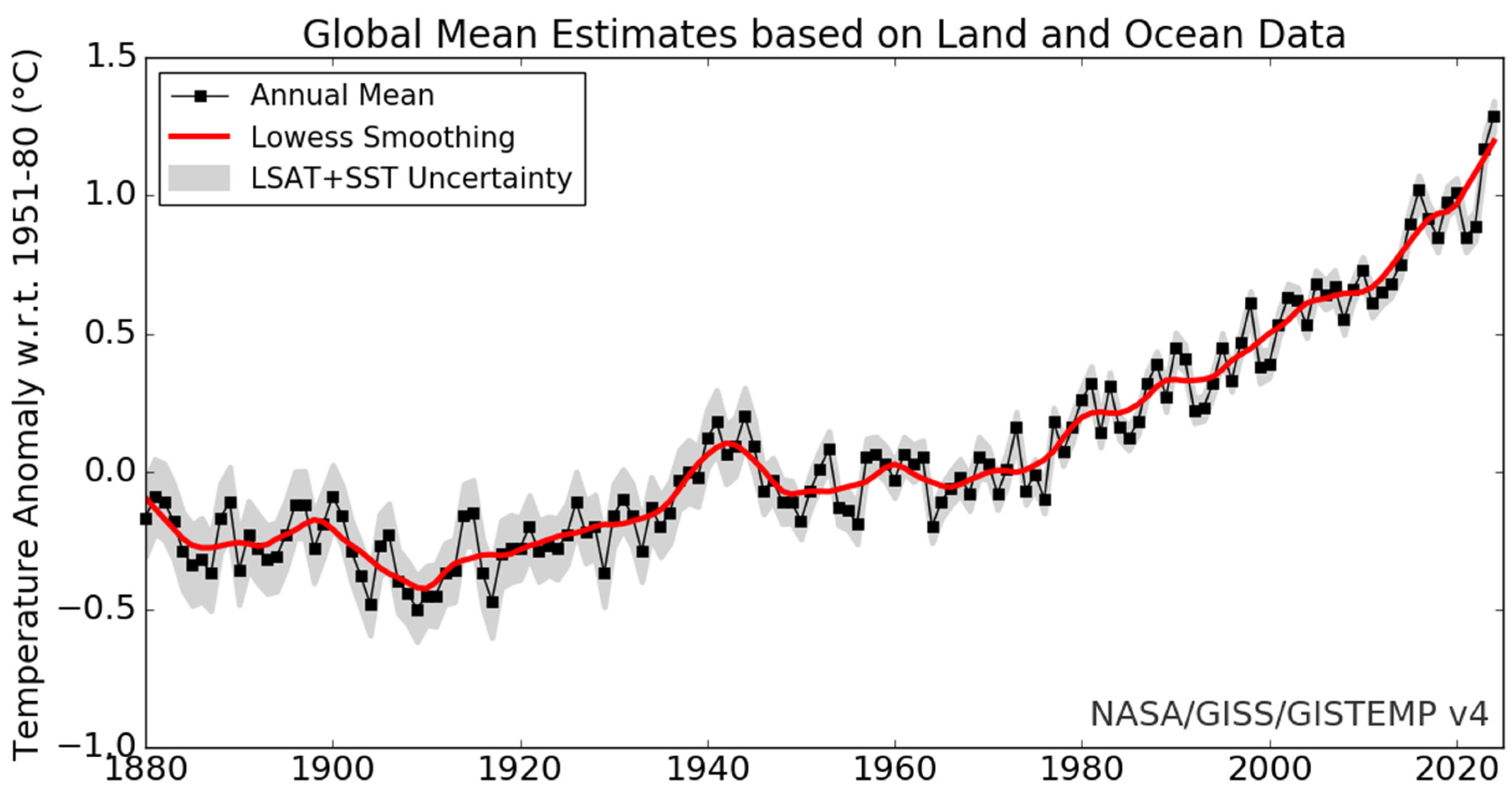

The latter case can be lucidly illustrated using the graph of the global average temperature (

Figure 1). The data exists since 1880, and a 95-%-uncertainty is shown as the shaded area. This information can be evaluated graphically or statistically. But just comparing visually the recent values to the earlier values, it is obvious that the observable change of about 1 °C is indeed a change when the uncertainty is taken into account (being in the size of tenths of degrees Celsius). This conclusion would be impossible to make if the uncertainty information was absent. On the other hand, when assuming an uncertainty of each value in the range of, say, 1 °C, the data would not support the hypothesis of a change. This example shows how crucial comparability and metrological traceability are, even for every day societal topics such as climate change.

3.1. Situation 2: Comparing a Measurement Result to a Limit Value

This frequent case does not fully comply with the VIM [

3] definition of comparability (which strictly mentions a measurement result to be compared to another measurement result). Yet, the concept applies without contradiction if the limit value is regarded as a measurement result

M with the special situation where

u(M)=0.

This case occurs often in industry when verifying if

- a)

calibration values of a measuring instrument comply with certain limits (e.g. maximum permissible errors, MPE),

- b)

the measurement values of industrial parts conform to the requirements of the purchasing party (e.g. in incoming inspection or in final product inspection).

In popular words, metrological comparability assures that we compare "apples with apples", or in VIM language: We compare values "of the same kind".

4. How to Make a Measurement Result Metrologically Traceable

Metrological traceability is usually depicted as a "chain" where metrological traceability is linked from one measurement result to the next one. Traceability starts at the "reference" (e.g. an SI unit). Then, a chain of calibrations or measurements can be established each contributing to the relation to this starting reference.

Each measurement is made by a measurement process. If the result of this process should be metrologically traceable, then the process (when it is running) must support the metrological traceability of its outcome (the measurement result) at all times and under all circumstances. The prerequisites for metrological traceability once were listed in an ILAC document [

4], but this chapter was abandoned in its most recent revision. The content was (amended and modified by the author):

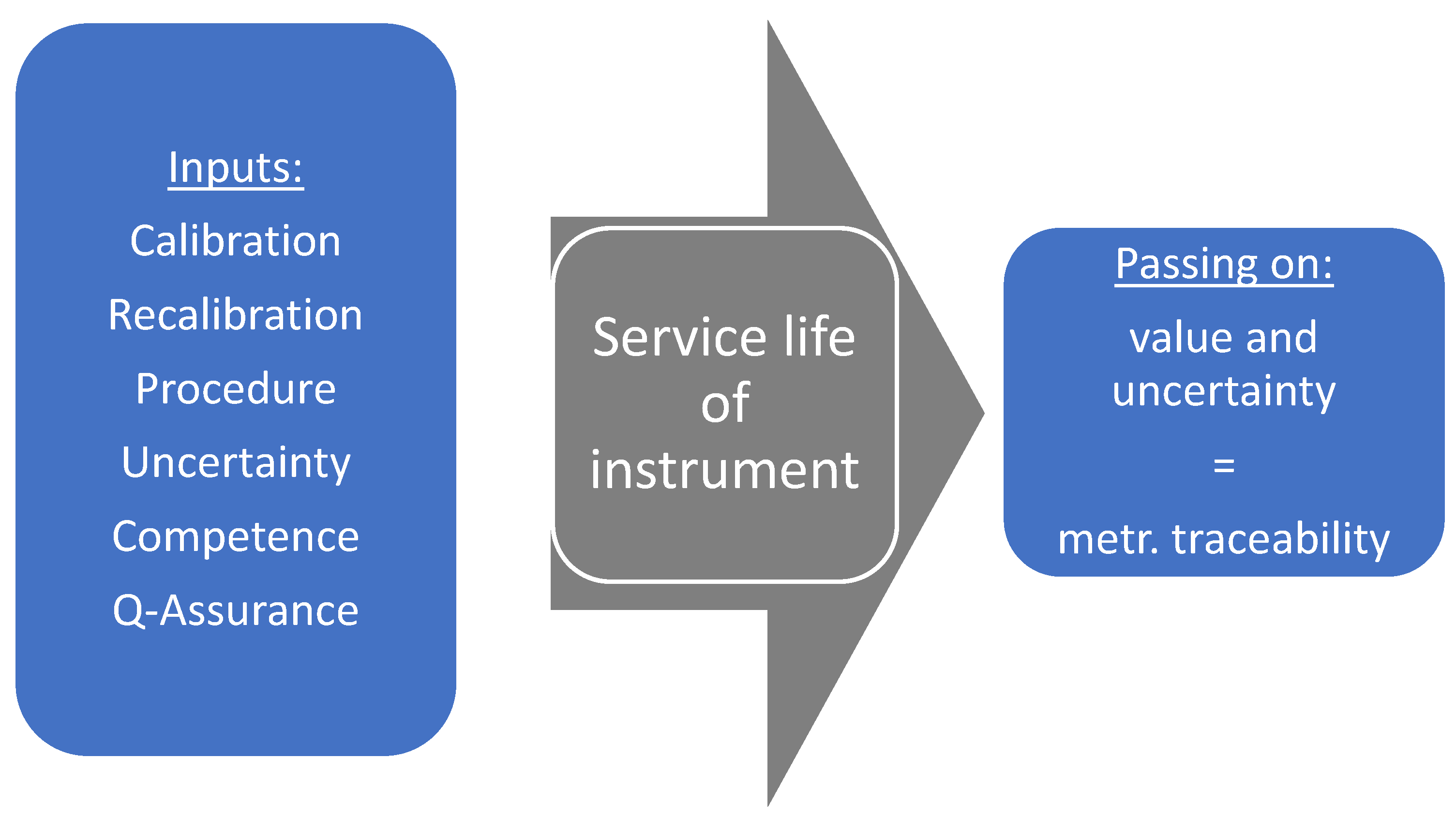

In order to deliver metrologically traceable measurement results linked to a reference, the measurement process must provide a link to the previous result by:

Metrologically traceable calibration of the measuring instruments,

defined and reviewed calibration intervals for the measuring instruments used (=the calibration programs) serving to establish the metrological traceability by a calibration and to maintain the metrological traceability during service life of the instruments after a calibration,

a documented controlled, proven measurement procedure,

documented measurement uncertainty,

competence,

established measurement process quality assurance (see

Figure 2).

Metrological traceability is usually passed on from the reference mentioned above to a measurement result by a series of connected calibration processes to a final stage, where a measurement is executed, and a conformity decision is made (i.e. the product is accepted or not). This decision is based on a tolerable range of values which is either given by own specifications or by external, sometimes legal, limits. The decision is made using a decision rule [

5] (definition 3.3.12). Since, in order to make the last measurement result metrologically traceable, the traceability requirements are the same until the very final measurement result along this chain, there is no principal difference between a calibration and a measurement. Since calibration is only some special form of measurement, both will be described with the term "measurement" henceforth.

5. The Traceability Chain – An Appropriate Picture?

In a chain, all links are usually tied firmly together. The links are invariant and durable and the linkage, once established, is always firmly present and there is no elasticity. The final link "pulls" the first link at the same time a load is applied on the final link. This picture does not fully support the concept of metrological traceability, where the measurements are not all done at the same time.

"Passing the baton" in a relay race seems to be a much better picture for traceability than the "chain": During a relay race, there is a difference in time and location, when the baton, after having been carried one lap after the start of the race, is passed to the next runner: Something happens with the baton during the process (the baton is carried a distance of one lap, it might absorb some sweat, it might receive some damage, and the runner will usually change it from one hand to the other).

This is exactly what happens to a piece of measuring equipment once calibrated: It is used, moved, and it ages after its calibration, until it is used. The picture of the "chain" delivers the wrong perception of an immediate "simultaneity" of the linkage and the unconditional and un-altered presence of the calibrated properties (the traceability information).

Getting back to the picture of the relay race, the same baton is passed more than once: After the start of the race, it is passed on to the next runner after having been carried for a full lap. We may assume that the baton ages in every round and might not have its starting properties after each lap.

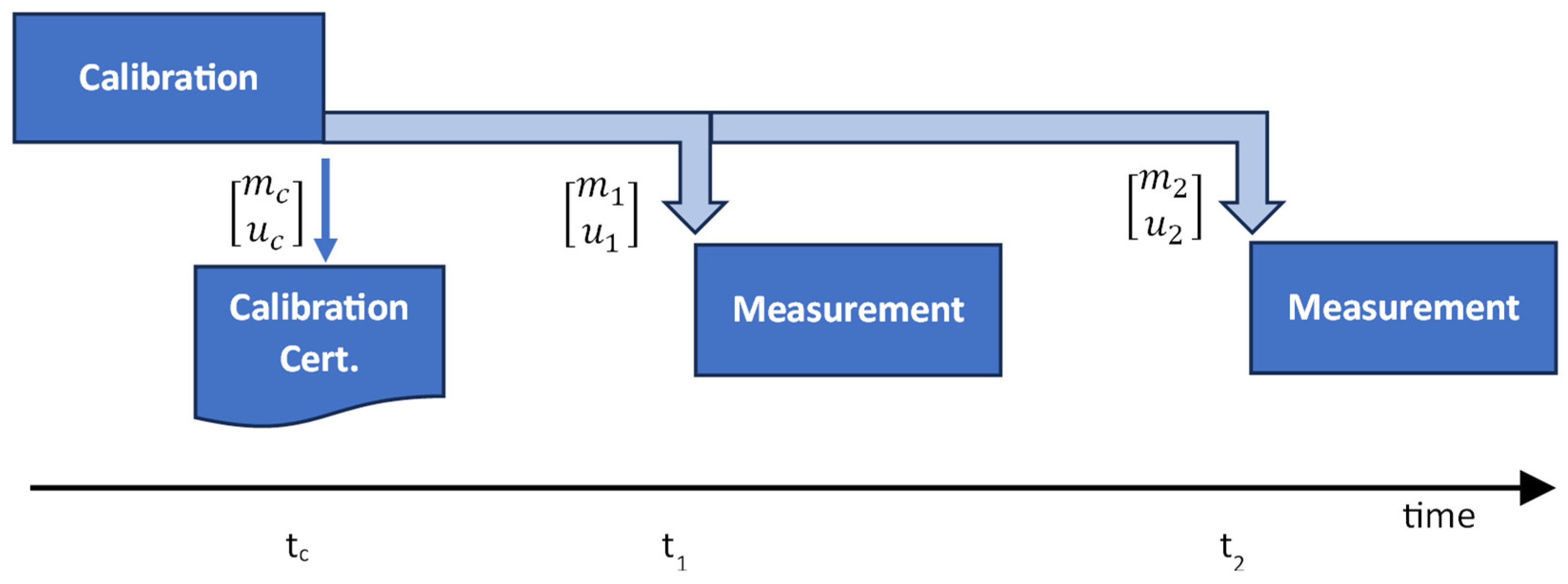

This corresponds to what will happen with a calibrated measuring instrument: The values established as a snapshot in the moment of calibration (subscript "c") are not the ones valid after a certain period or after a number of uses ("1" and "2"). Time and use will alter the properties (sometimes called the behavior) of the calibrated instrument, and it is the responsibility of the user to have the necessary competence [

6] (section 7.2) and [

1] (section 6.2) in order to be able to perform a modelling of either the uncertainty

u or the value

m, or both of the instrument, in a way that the requirement of metrological traceability is met as long as it is used

1. This is illustrated in

Figure 3:

This modelling of the traceability information by changing the values originally gained at the calibration snapshot, is done on all levels of metrology: The behavior of BIPM's Pt-Ir kilogram prototypes was modelled with time [

7] and OIML R111 tells us to account for changes of a reference weight during its service life by increasing the uncertainty by a constant component [

8] (section C.6.2). A small collection of such strategies of modelling the traceability information subsequent to calibration can be found in [

9].

6. Discussion

As has been shown above, calibration of the measuring instrument alone does not provide metrological traceability. We need the "full set" of prerequisites as described above in section 4.

What is also evident is that a measurement result without a (stated and/or elsewhere documented) measurement uncertainty can never be called "metrologically traceable" since otherwise the "traceability information" is incomplete.

Once a measuring instrument is calibrated, its metrological properties will change with time and/or use

2. The calibration results are only a snapshot picture of the properties of the instrument and are valid at the point of calibration only. This "point" may be a point in time or a geographical point or a point of ambient conditions or a combination of these. So, after the calibration, some kind of modelling these properties over time and/or place and/or use must start.

Metrological traceability is a binary property: Either it is there, or it is not.

3 But if it is there, the metrologically traceable value can rightfully be used to pass on metrological traceability by using it in a measurement process.

7. Review of the Present Definition of Metrological Traceability

In the light of the above, we review the present definition as is found in the international Vocabulary of metrological terms (VIM) [

3]:

Definition: property of a measurement result whereby the result can be related to a reference through a documented unbroken chain of calibrations, each contributing to the measurement uncertainty.

Unfortunately, this text appears to lead to a number of mis-interpretations:

The first misunderstanding is that using a previously calibrated measuring instrument be the only prerequisite to achieve metrological traceability of a measurement result, since the "unbroken chain of calibrations" seems the only graspable requirement mentioned in the definition. This is not true, since this would omit propagating the traceability information to the result of the final measurement. Nothing is said about the result having to carry the traceability information. The definition only requires that the result "can" be related to the reference. ISO 9001 requires metrologically traceable results (under certain conditions). And it is obvious, that if a conformity decision for a product must be made under the regime of ISO 9001, also the measurement result used for this decision must be metrologically traceable. ISO 9001 is probably the most numerously printed statement about metrological traceability: More than 800000 organizations [

10] have a management system being certified to ISO 9001:2015. We may assume that every of these organizations holds a copy of the document, so it is printed (or digitally published) nearly a million times. It requires in section 7.1.5.2 that in order to achieve metrological traceability of measurement results, the measuring equipment used must be traceably calibrated (wording simplified by the author): The only requirements which are put up in this document concerning metrological traceability, refer to the calibration of the measuring equipment. There is no requirement regarding the measuring processes, no requirement regarding specific competence, no requirement on how to establish meaningful calibration intervals etc. Revealingly, this paragraph is found in the section "Resources" of the standard which stresses again the instrument-oriented view on metrological traceability instead of a process-view.

It seems a widespread misunderstanding that this ISO 9001 requirement is fulfilled when just the measuring instrument used for making the measurement is calibrated, since the VIM definition only mentions "calibrations" and never mentions "measurements". But, as shown above, metrological traceability must extend to the least and last measurement result of the chain and there is no difference regarding the requirements of the measuring process if the result is a calibration result or a measurement result. We need the full traceability information even at the end in order to make decisions while fulfilling metrological comparability.

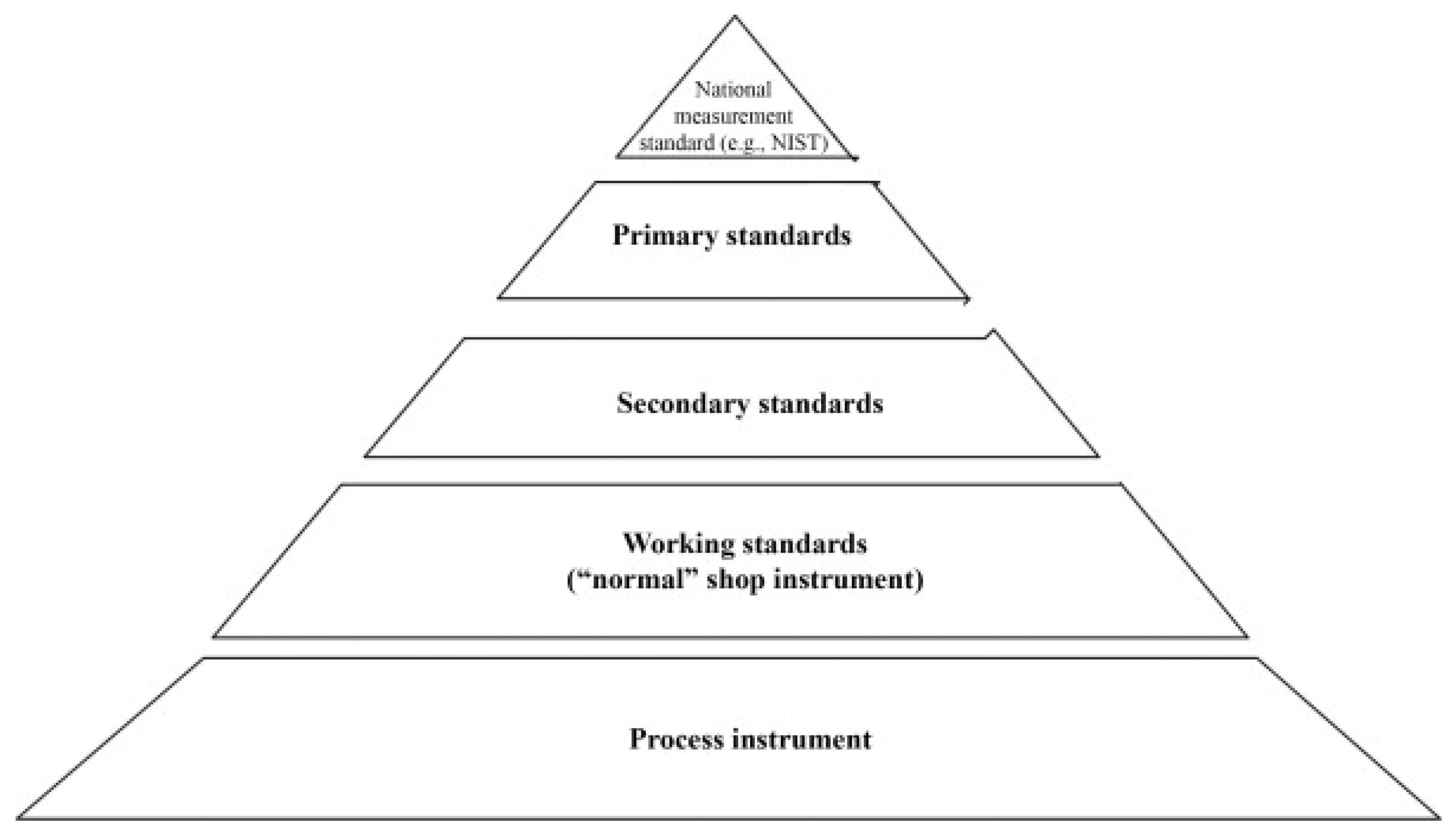

The second misunderstanding is also linked to using the word "calibrations" in the definition: It is a common mis-interpretation that the traceability is established by calibrated instruments. A simple search on the internet reveals abundant pictures of traceability pyramids mentioning instruments only (see

Figure 4 as an arbitrary example).

This is obviously wrong, since metrological traceability is a property of measurement results (which in turn are the outcome of measurement processes) and is not a property of instruments. In this context, the VIM definition phrase "each [calibration] contributing to the uncertainty" must be considered very unfortunate, if not wrong, since it suggests that only the calibration results contribute to the uncertainty of the measurements (which again nourishes the first mis-conception above).

The third misunderstanding is the phrase "to a reference". This is often wrongly understood that only one single reference (instrument) is meant here. This can be easily counter-argued by the simple example of a calibration of a weighing scale. When establishing the metrological traceability chain, not only mass is measured, but also influence properties like air pressure, temperature, air humidity, sometimes gravitational acceleration etc. These contribute to the calculation of the corrected calibration result and to its measurement uncertainty. These parameters connect the measurement results to far more than one single reference: The units for mass, time, length, temperature etc. are involved in the traceability chain of a "simple" weighing scale. So, linking a calibration value of a weighing scale (indicated in kilograms) to the Planck-constant only in a one-dimensional pyramid picture, would vastly simplify the real process and omit substantial contributions to its traceability information.

8. Historical View onto the VIM Definition

The present VIM-definition of metrological traceability is a result of controversial discussion dating back to the early 1980s: Belanger [

12] cites four conceptually different definitions for metrological traceability suggested and discussed at that time. His key statement comparing the two most controversial suggestions is: "A comparison of definition 1 with definition 2 provides perhaps the clearest exposition of two contrasting views of traceability, the first stressing characteristics of measuring instruments or standards, while the second stresses requirements related to quantifying measurement uncertainty." As we can conclude from this brief statement and from our knowledge of today's VIM definition, the discussion must have ended in favor of the calibration-oriented and instrument-oriented approach.

This is unfortunate since the present definition is "prescriptive" in terms of the way to achieve metrological traceability (namely by calibrations of instruments). This appears to be the root cause of the misconceptions explained above. A more descriptive definition (with elements of the "definition 2") simply requiring a statement of relationship of any measurement result to a reference, expressed by a value and an associated measurement uncertainty might have led to less misconception and to a broader understanding of the concept. This would have also prevented simplifications of the concept to establish and to gain acceptance.

9. Summary and Conclusions

Metrological Traceability is an indispensable concept yet hidden for most individuals of the general public. It is the foundation for science to make decisions and for the industry to accept or reject their products. These decisions are made based on a related concept, the metrological comparability. The content of metrological traceability seems to be difficult to convey as a concept: The definition of the VIM of metrological traceability is the result of a dispute and according to the author's view, the present definition was not the best choice and omits important aspects and simplifies others, resulting in common mis-interpretations. This should be corrected by amending or reviewing the VIM-definition. The VIM-concept has been transferred into industry by a text in ISO 9001 which improperly simplifies it in a way endangering both the understanding and the implementation of metrological traceability. An improved VIM-definition would offer an opportunity to also improve the understanding of the concept of metrological traceability in the industry.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Blair Hall for encouraging this article and Charles Ehrlich for his immense contribution to metrology. This text has been elaborated using human intelligence only.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 |

According to the author's understanding, this is what is meant when ISO 17025 [ 1] requires "establish and maintain metrological traceability" in its section 6.5.1. |

| 2 |

This is the only reason and justification why we re-calibrate. |

| 3 |

Or as Ehrlich [ 13] says: "there is no such thing as partial "traceability"" |

References

- International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland (2017), ISO/IEC 17025 2017 - General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories.

- NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, Available online: https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/graphs/ URL (accessed on 02 May 2025).

- BIPM, IEC, IFCC, ILAC, ISO, IUPAC, IUPAP, and OIML. International Vocabulary of Metrology—Basic and general concepts and associated terms (VIM). Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology, JCGM 200:2012. (3rd edition). [CrossRef]

- ILAC, Newton, Australia, ILAC P-10:2002.

- BIPM, IEC, IFCC, ILAC, ISO, IUPAC, IUPAP, and OIML. Evaluation of measurement data — The role of measurement uncertainty in conformity assessment. Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology, JCGM 106:2012. doi:10.59161/jcgm106-2012.

- International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland (2015), ISO 9001:2015 Quality management systems – Requirements.

- Lars Nielsen, Richard S Davis and Pauline Barat: Improving traceability to the international prototype of the kilogram, Metrologia 52 (2015). doi:10.1088/0026-1394/52/4/538.

- ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE MÉTROLOGIE LÉGALE, Paris, France, OIML R 111-1:2004: Weights of classes E1, E2, F1, F2, M1, M1–2, M2, M2–3 and M3, Part 1: Metrological and technical requirements.

- Christian Müller-Schöll, Maintenance of metrological traceability in an interval, Measurement: Sensors, Volume 18, 2021, 100234, ISSN 2665-9174, . [CrossRef]

- ISO CASCO, International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland (2024), THE ISO SURVEY OF MANAGEMENT SYSTEM STANDARD CERTIFICATIONS – 2023 – EXPLANATORY NOTE, Available online: https://www.iso.org/the-iso-survey.html (accessed on 02 May 2025).

- Manuel Correia, Eveline Verleysen, Katrin Loeschner, Chapter 10 - Analytical Challenges and Practical Solutions for Enforcing Labeling of Nanoingredients in Food Products in the European Union, Editor(s): Amparo López Rubio, Maria José Fabra Rovira, Marta martínez Sanz, Laura Gómez Gómez-Mascaraque, In Micro and Nano Technologies, Nanomaterials for Food Applications, Elsevier, 2019, Pages 273-311, ISBN 9780128141304, . [CrossRef]

- Brian C. Belanger, Traceability in the U.S.A.: An evolving concept, OIML Bulletin No. 78, 1980, OIML, Available online: https://www.oiml.org/en/publications/bulletin/pdf/1980-bulletin-78.pdf#page=23 (accessed on 02 May 2025).

- Ehrlich CD, Rasberry SD. Metrological Timelines in Traceability. J Res Natl Inst Stand Technol. 1998 Jan-Feb;103(1):93-105. Epub 1998 Feb 1. PMID: 28009372; PMCID: PMC4891962. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).