1. Introduction

African swine fever (ASF) is a viral disease caused by African swine fever virus (ASFV) which poses a severe threat to domestic pigs and Eurasian wild boars due to their high fatality. Thus, their economic and social impacts are considerable. ASFV is classified as a notifiable disease by the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) [

1,

2]. ASFV belongs to the Asfivirus genus within the Asfarviridae family, categorized as a large, icosahedral virus with linear double-stranded DNA [

3]. ASFV replication primarily takes place within the cytoplasm of infected macrophages, although an initial replication phase has also been observed within the nucleus [

4]. The viral genome varies in length, ranging from 170 to 194 kilobase pairs (kb) and contains 150 to 167 open reading frames (ORFs). Structurally, it consists of a conserved central region about 125-kb long, flanked by two variable ends that harbor five multigene families (MGFs) [

5]. Deletions and insertions up to 20-kb long occur in MGFs, suggesting their roles in generating antigenic variability, and facilitating ASFV to evade the host immune system. ASFV particles display high complexity: two-dimensional electrophoresis reveals a minimum of 28 structural in intracellular particles and 54 in purified extracellular proteins [

6]. Over 100 virus-induced proteins have been identified in infected porcine macrophages [

7]. Numerous studies have shed light on vectored and subunit vaccines against ASF, emphasizing their safety advantages over other vaccine development technologies. Many structural proteins, such as p30, p54, p72, EP153R, D117L, and CD2v, have been used to develop vaccines against ASF [

3]. Nonetheless, the utilization of various subunit vaccine strategies, specifically those employing p30, CD2v, and p72 as antigens, has exhibited restricted advancement and yielded inconsistent results [

8]. Moreover, relying solely on the antigen has not proven to be a promising strategy to protect animals against virus challenge [

9]. The previously inactivated vaccines fail to work against ASF. Efforts are being made to develop more effective live attenuated vaccines and gene deletion, subunit, DNA, and vector-type vaccines. Vietnam’s ASFV-G-ΔI177L is the first commercial ASF vaccine developed in that country, but strain attenuation does not guarantee virulence due to extensive genotype-specific defense mechanisms. The viral genome directs the synthesis of numerous proteins essential not only for viral assembly but also for critical functions such as DNA replication, repair mechanisms, and the intricate control of genetic expression [

10]. Moreover, the ASFV genetic blueprints contain a range of proteins cleverly engineered to thwart host immune responses, effectively disrupting type I interferon signaling and manipulating cellular death pathways in its favor [

11].

A comprehensive examination of around 30% ASFV antigens was conducted using a strategic method, which involved delivering distinct gene pools via DNA immunization priming, followed by reinforcement with a recombinant vaccinia virus vector [

12]. This comprehensive methodology aimed to systematically assess each antigenic component's immunological potential in pigs, advancing our comprehension of ASFV immunobiology and aiding in vaccine target selection. Results showed that the D117L and E120R proteins hold promise as potentially significant triggers of a protective antibody response or as serological markers of infection. Additionally, ASFV proteins, including p54 (E183L) and CD2v (EP402R), effectively stimulated specific lymphocytes in immunized pigs, resulting in a robust cellular immune response [

13,

14].

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) have found to be extensively use in the generation of mucosal vaccines because of their safety and capacity to stimulate mucosal as well as systemic immune responses. Among these LABs, the NC8 strain has been frequently employed. NC8, a thoroughly researched strain of LAB, is designated as generally recognized as safe (GRAS) owing to its long-standing utilization in human food fermentations and products. Numerous studies have shown that NC8 can be applied to vaccine vectors by various routes of administration [

15]. For instance, NC8 engineered to express the porcine epidemic diarrhea antigenic proteins and the coxsackievirus B4 protein effectively induced the production of mucosal antibodies, and robust cell-mediated immune response [

16,

17]. Recently, a study evalated the immune responses induced by a recombinant NC8 strain expressing the ASFV p54 (E183L) protein fused with the porcine IL-21 in mice [

18].

In this study, a mixture of six recombinant NC8 bacterial strains each expressing one of antigenic proteins of ASFV (E120R, E183L, H171R, D117L, K78R, and A104R) was selected and mixed togather to formulate as an ASF vaccine candidates. We then verified the immune responses of these candidates in mice via I.G., I.N., or I.V. routes. The goal of this study is to provide a basis for the development of a vaccine using LAB as a carrier by optimizing the route of administration. By exploring these vaccine candidates, we aim to present new avenues for advancing the development of an effective vaccine against ASF. The overall objective is to contribute to the control of ASF.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Viruses, Plasmids, and Cells

The NC8 strain and pMG36e expression plasmid were kindly provided by Prof. Guangxing Li, Northeast Agricultural University. The corresponding viral gene sequences of the ASFV HJL/2018 strain (GenBank accession number: MK3331180.1) were codon-optimized according to the complete genome sequence for expression in NC8 and sent to GenScript for synthesis. Freshly extracted T cells from the spleens of the immunized mice were used to evaluation immune responses.

2.2. Construction of the Recombinant Plasmids Surface-Expressing the ASFV Antigens

The sequence of LP3065 was obtained from the NCBI GenBank, sourced from the complete genome of

L. plantarum WCFS1 (GenBank accession number: AL935263.2), and was synthesized from Rui Biotech. We screened out LP3065 for surface expression in our previous study [

19]. The LP3065 surface anchoring motif was inserted into the pMG36e vector between

XbaI and

HindIII. Once the LP3065 linkage was established, the established vector was verified through PCR and after confirmation of exact band lenghth, the pMG36e-LP3065 vector was underwent a subsequent round of digestion using

XhoI and

BamHI restriction enzyme recognition sites. Following this, the six ASFV antigens (E120R, E183L, D117L, H171R, K78R, and A104R) were amplified through specific primers shown in

Table 1 and ligated between

XhoI and

BamHI restriction enzyme recognize sites overnight at 16°C with T4 ligase. Moreover, 6×His-tag and Strep-tag were incorporated into the LP3065 sequence to facilitate the detection of the target protein using an anti-His-tag and anti-Strep-tag antibodies (

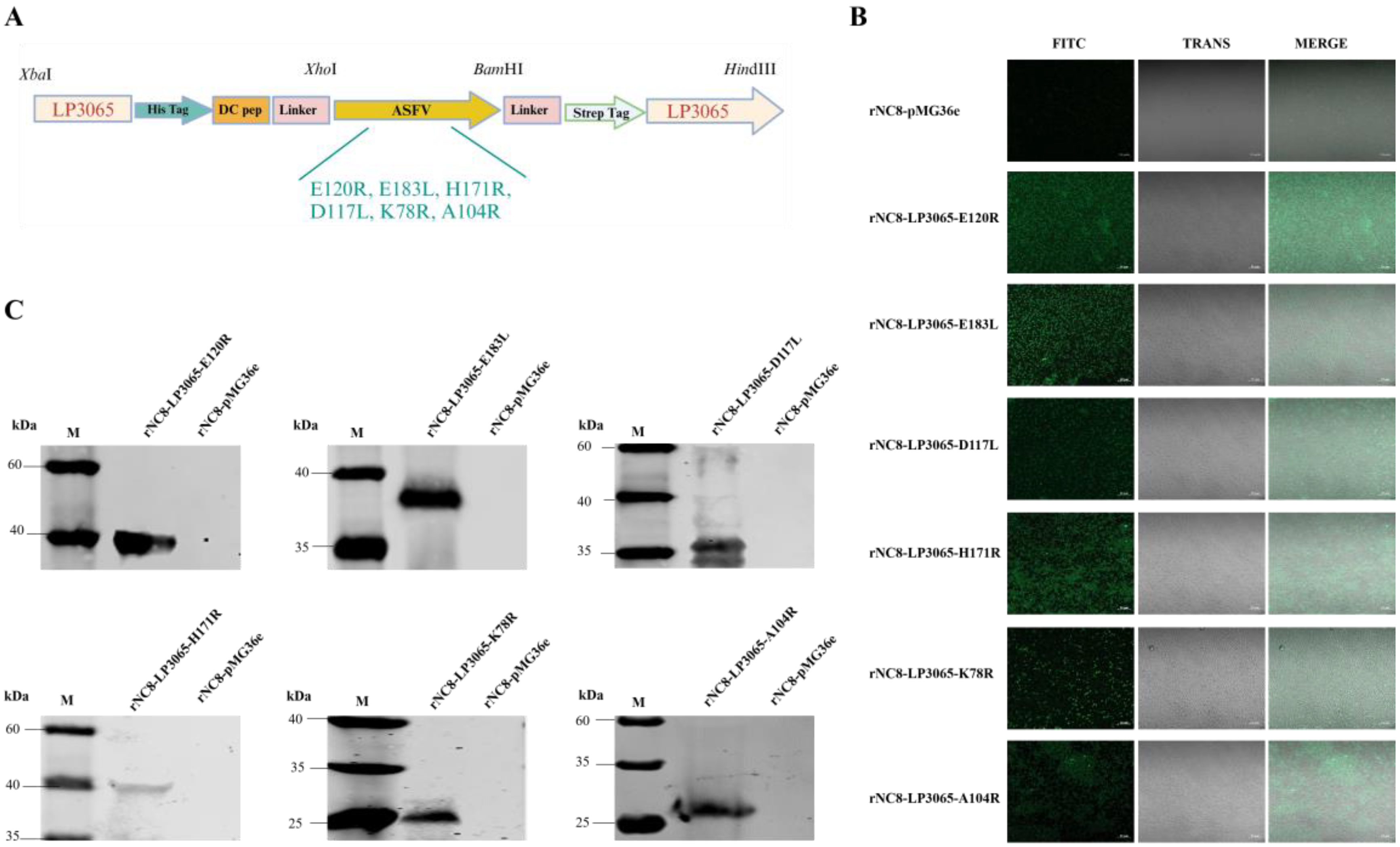

Figure 1a).

2.3. Construction of the Recombinant NC8 (rNC8) Strains

NC8 competent cells were thawed on ice until fully melted. Then, 10 μL of the recombinant plasmids were added and thoroughly mixed with the NC8 competent cells, followed by additional incubation for 2 min on ice. Subsequently, the mixture was transferred into a pre-cooled 0.2-cm electroporation cuvette. The settings for electroporation were adjusted to administer a single pulse of 2000 V, 25 μF, and 200 Ω, with an electrical pulse duration of 4 to 5 ms. After electroporation, the cells were promptly suspended in 700 μL of pre-cooled MRS broth (without antibiotics) and rested on ice for another 5 min. The generated recombinant cells (rNC8-E120R, rNC8-E183L, rNC8-D117L, rNC8-H171R, rNC8-K78R, and rNC8-A104R) were incubated at 37°C for 1 h for activation. The cultures were centrifuged at 6000 × g for 2 min, and 50 μL of the supernatants were retained to resuspend the pelleted NC8 bacterial cells. The resuspended cells were plated on MRS agar medium containing 10 μg/mL erythromycin and incubated at 37°C until clonal growth occurred. Subsequently, single colonies were selectively picked in MRS broth and stored at –80°C for future use.

2.4. Immunofluorescence Identification of Recombinant Proteins on the Surface of rNC8 Strains

For immunofluorescence identification, the recombinant NC8 (rNC8-E120R, rNC8-E183L, rNC8-D117L, rNC8-H171R, rNC8-K78R, and rNC8-A104R), and rNC8-pMG36e with the empty vector pMG36e as negative control were cultured in MRS broth overnight, and a pallet was collected by centrifugation. The pellet was washed twice with phosphate buffered-saline (PBS) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. The pellet was washed twice and 1% BSA was added and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Again, the pallet was washed and anti His-tag antibody (catalog No. K200060M, Beijing, China) was added and incubated at 37°C on a rotary stirrer for 1 h. The pellet was again washed twice with PBS and secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG(H+L) (catalog No. A-11001; ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) was added and recombinant bacterial strains were incubated at 37°C for 45 min without exposure to the light. After incubation, 2 µL of bacterial suspension was dropped on a glass slide, evenly applied with the side of the tip, and dried naturally and observed under a confocal microscope (

Figure 1B).

2.5. Western Blotting Analysis of the Recombinant Proteins Expressed by rNC8

The rNC8 strains (bearing the respective recombinant plasmids) were sub-cultured anaerobically at 37°C overnight in an MRS medium containing 10 μg/mL erythromycin. The culture that was left overnight was separated by centrifuging at 5000 ×g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed thrice with cold PBS, after which it was ready for further processing. A total of 100 μL of lysozyme was added to a freshly centrifuged pellet of bacteria to disrupt the cell wall, followed by a freeze-thaw cycle at −30°C for 30 min. After thawing, sonication was performed to lyse the cell wall, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. A 40-μL pellet containing antigen proteins was combined with 10 μL of 5× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer, denatured by boiling at 100°C for 15 min, and then centrifuged at 8000 × g for 2 min. A 30-μL protein sample was loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel containing a 5% stacking gel and a 10% separation gel.

The proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane using an electro-transfer after SDS-PAGE. After the transfer was complete, the PVDF membrane was blocked with 1% skimmed milk solution for 3 h at room temperature. The PVDF membrane was incubated with the anti-His-Tag antibodies at a dilution of 1:2000 for 2 h. The PVDF membrane was washed twice and then the membrane was incubated with IRDye 680RD goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (catalog no. C50113-06, Li-Cor, USA) at a dilution of 1:10,000 for 45 min. After washing the PVDF membrane with PBS, the blots were visualized by an Odyssey two-color infrared fluorescence imaging system (Li-Cor) (Figure 1C).

2.6. Immunization of Mice

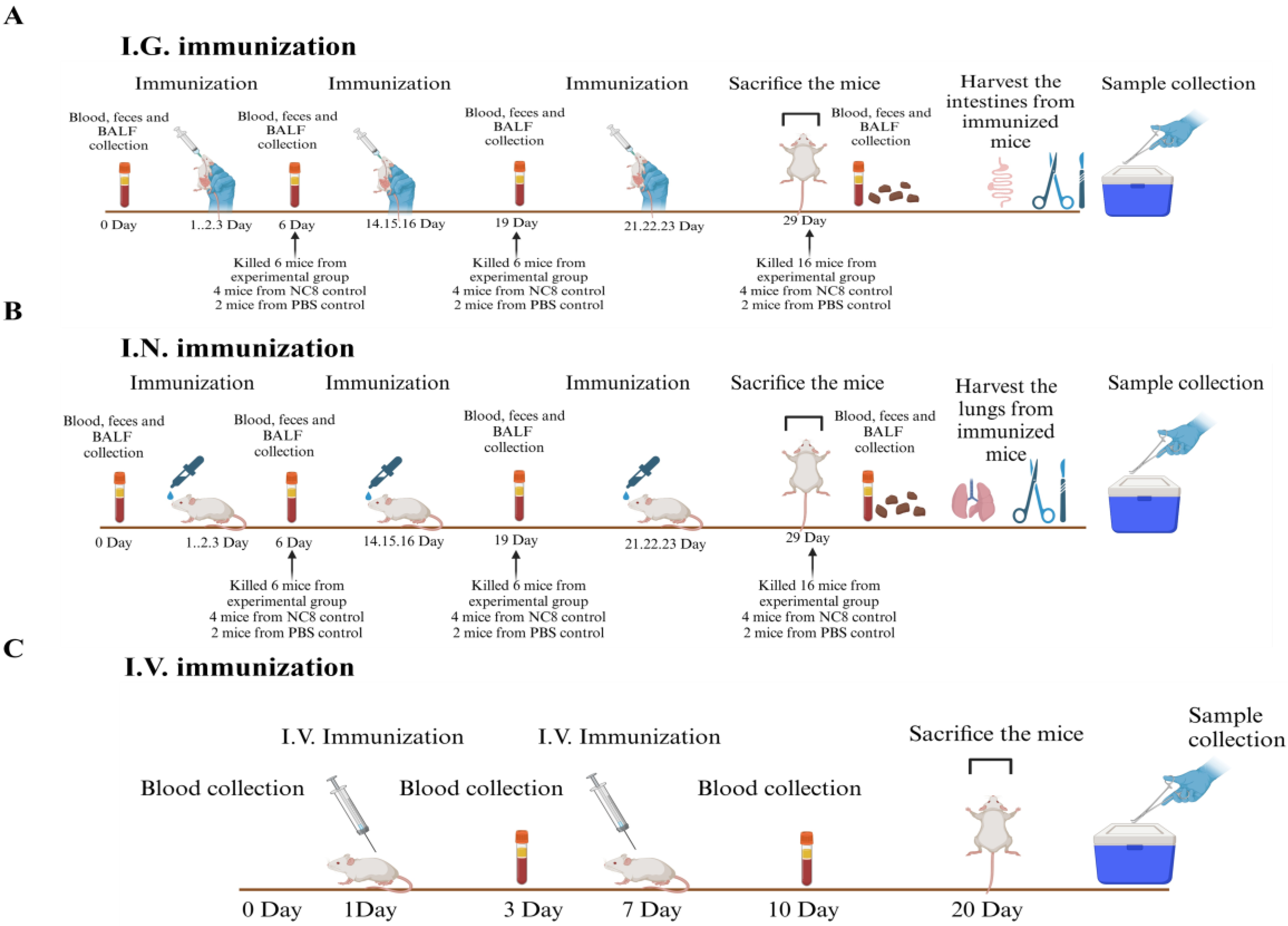

Forty six-week-old mice, devoid of specific pathogens, were distributed into six groups, i.e., rNC8-ASFV-mix (I.G. and I.N.), rNC8 control (I.G. and I.N.), and PBS control (I.G. and I.N.). The immunization protocols were divided into three regimes, i.e., prime shot at 1, 2, and 3 days post-immunization (dpi), second shot at 14, 15, and 16 dpi, and last immunization at 21, 22, and 23 dpi for both I.G. and I.N. immunization, while days at 0, 3, 10 and 20 dpi for I.V. immunization (Figure 1A and B). The mice were immunized with recombinant bacteria expressing ASFV antigens or control bacteria containing the empty vector. PBS was administered to the control group additionally. Subsequently, rNC8 bacterial pellets were collected from overnight culture and washed twice with PBS. The pellets were then re-suspended in sterile PBS, achieving an appropriate concentration (109 CFU/mouse for rNC8, and 200 µL of PBS for the control). The immunization regimen involved administering rNC8LP3065-ASFV-mix (109 CFU/mL) via I.G. (200 µL) and I.N. (10 µL) routes to each group. For I.N. immunization, the mice were anesthetized with 2.5% avertin (0.02 mL/g body weight).

The feces, blood, and bronchioalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from the immunized mice were collected at 0, 6, 19, and 28 dpi in I.G. and I.N. administered groups. Sera were collected from the I.V. group at 3, 10, and 20 dpi from blood samples and stored in a –30°C refrigerator for further use.

2.7. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

IgG and IgA antibodies in the sera, intestines, and lungs of the immunized mice were examined by ELISA. The intestines and lungs collected from the immunized mice, were weighed (approximately 0.1 g) and homogenized in 100 µL of DMEM by the tissue lyser II (Biorepublic, Beijing, China) and the supernatants from each tissue sample were collected for detection of IgG and IgA by ELISA. The purified proteins of the antigens were coated on 96-well cell culture plates overnight at 4°C. The next day, the 96-well plates were blocked with 0.5% skim milk for 2 h. After incubation, the 96-well plates were washed thrice with 100 µL of PBST and 1:200 diluted sera or supernatants of intestines and lungs were added into each well and incubated for 2 h. The 96-well plates were washed thrice with 200 µL of PBST. The rabbit anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (catalog no. ab6728; Abcam UK) secondary antibodies or goat anti-mouse IgA (ab97231; Abcam UK) were added and incubated in the plates for 45 min. After washing thrice with PBST, 100 µL of tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was added to each well and the reaction was stopped by 2 M H2SO4. The absorbance at 450 nm (OD45nm) of each well was measured with a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, USA). Serum cytokines IL-2 (catalog no. SEA073Mu), IL-4 (catalog no. SEA077Mu), IL-10 (catalog no. SEA056Mu), and IFN-γ (catalog no. SEA049Mu) levels were analyzed using a commercially available ELISA kit (Cloud-Clone, Wuhan, China).

2.8. Isolation of T lymphocytes from the Spleens of the Immunized Mice

Splenocytes were collected from the spleens of three mice per group at the indicated time points. The spleens were individually disrupted using sterile RPMI-1640 medium (catalog no. R8758; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Hyclone, USA) and the cell suspension was filtered through a 100-µm nylon filter. Splenic T cells were isolated using a mouse spleen lymphocyte isolation kit (catalog no. CB6310; G-Clone, Beijing, China). The splenic T cells were washed twice with RPMI 1640 medium, and the supernatant was discarded. To remove red blood cells, an erythrocyte lysate buffer (catalog no. BL503B; Biosharp Life Sciences, Hefei, China) was added. The cells were washed twice with sterile PBS. The T lymphocytes were harvested and cell count was determined using a cell counting machine.

2.9. Splenic T Lymphocyte Proliferation Assay

The splenic T lymphocytes were cultured in 96-well microplates at a density of 5×106 cells/mL (50 μL/well), and then stimulated with (105 TCID50) ASFV, 10 μg/mL concavalin A as a positive control, or culture medium as a negative control. The plates were incubated for 72 h in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. To evaluate proliferation responses, the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) assay (Ape×Bio, USA) was utilized. After incubation at 37°C in the dark for 3 h, OD450nm was measured on a microplate reader. The data were expressed as stimulation indices (SI), calculated as the ratio of stimulated value minus blank value to unstimulated value minus blank value.

2.10. Analysis of Splenic T Lymphocytes by Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry assay was utilized to assess the presence of costimulatory molecules on T cells in the immunized mice. In brief, a single-cell suspension was gathered from the splenocytes obtained from the experimental and control groups and subsequently diluted to a final density of 106 cells/mL. A portion of this suspension was then exposed to phycoerythrin (PE)/cyanine5 anti-mouse CD3 (catalog no. 100273), APC/cyanine7 anti-mouse CD8a (catalog no. 100713; BioLegend, UK), and FITC rat anti-mouse CD4 (catalog no. 557307; BD-Biosciences, China) antibodies to mark T cells (1:100 dilution), while another portion was retained without antibody treatment for a negative control. Subsequently, the samples were incubated at 4°C for 30 min, followed by a PBS wash. The cell suspension was filtered through a 5-mL Falcon round-bottom polystyrene test tube, with a cell strainer snap cap (catalog no. 352235; Corning Science, S.A. de CV, Mexico). Finally, the samples were processed using flow cytometry (ApogeeFlow System, Northwood, UK). The data were analyzed by using the Apogee histogram software.

2.11. Ethic Statements

All the experimental procedures involving ASFV manipulation in this trial were carried out in the biosafety level 3 (BSL3) biocontainment facilities at Harbin Veterinary Research Institute (HVRI) of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS) and were approved by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, China. This study was carried out in compliance with the requirements of the Animal Welfare Act and the guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals, approved by the Laboratory Animal Welfare Committee of the HVRI under approval number 230724-01-GR.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

All experimental procedures were meticulously replicated a minimum of three times to ensure reliability and reproducibility. For comprehensive statistical analysis, the GraphPad Prism software, version 8.3 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, California, United States), was employed. The resultant data are presented as the arithmetic means ± standard deviations (SDs). Statistical significance was determined by assessing the p-values, with * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, and not significant difference (ns).

3. Results

3.1. Surface-Expression Analysis for LP3065 Fused with the ASFV Antigens

The recombinant plasmids ligating ASFV antigens have been successfully constructed by using the LP3065 surface anchoring polypeptide as per the schematic diagram (

Figure 2A). The recombinant plasmids were transformed into NC8 expression bacteria to obtain recombinants named rNC8-LP3065-E120R, rNC8-LP3065-E183L, rNC8-LP3065-D117L, rNC8-LP3065-H171R, rNC8-LP3065-K78R, and rNC8-LP3065-A104R. Confocal microscopy revealed green fluorescence on the surface of bacterial cells (

Figure 2B), indicating the expression of the ASFV antigens. The expression of ASFV antigens was compared with the rNC8-pMG36e bacteria.

Moreover, LP3065 fused with ASFV proteins were expressed on the surface of rNC8 and assessed by Western blotting assay. The results verified the expression of LP3065-E120R (33 kDa), LP3065-E183L (39 kDa), LP3065-D117L (32 kDa), LP3065-H171R (39 kDa), LP3065-K78R (28 kDa), and LP3065-A104R (31 kDa). The western blotting bands were consistent with the size of rNC8-LP3065-ASFV antigens in extracts from recombinant strains by probing with anti-His antibody. On the other hand, no bands were observed in extracts from the rNC8-pMG36e control (Figure 2C).

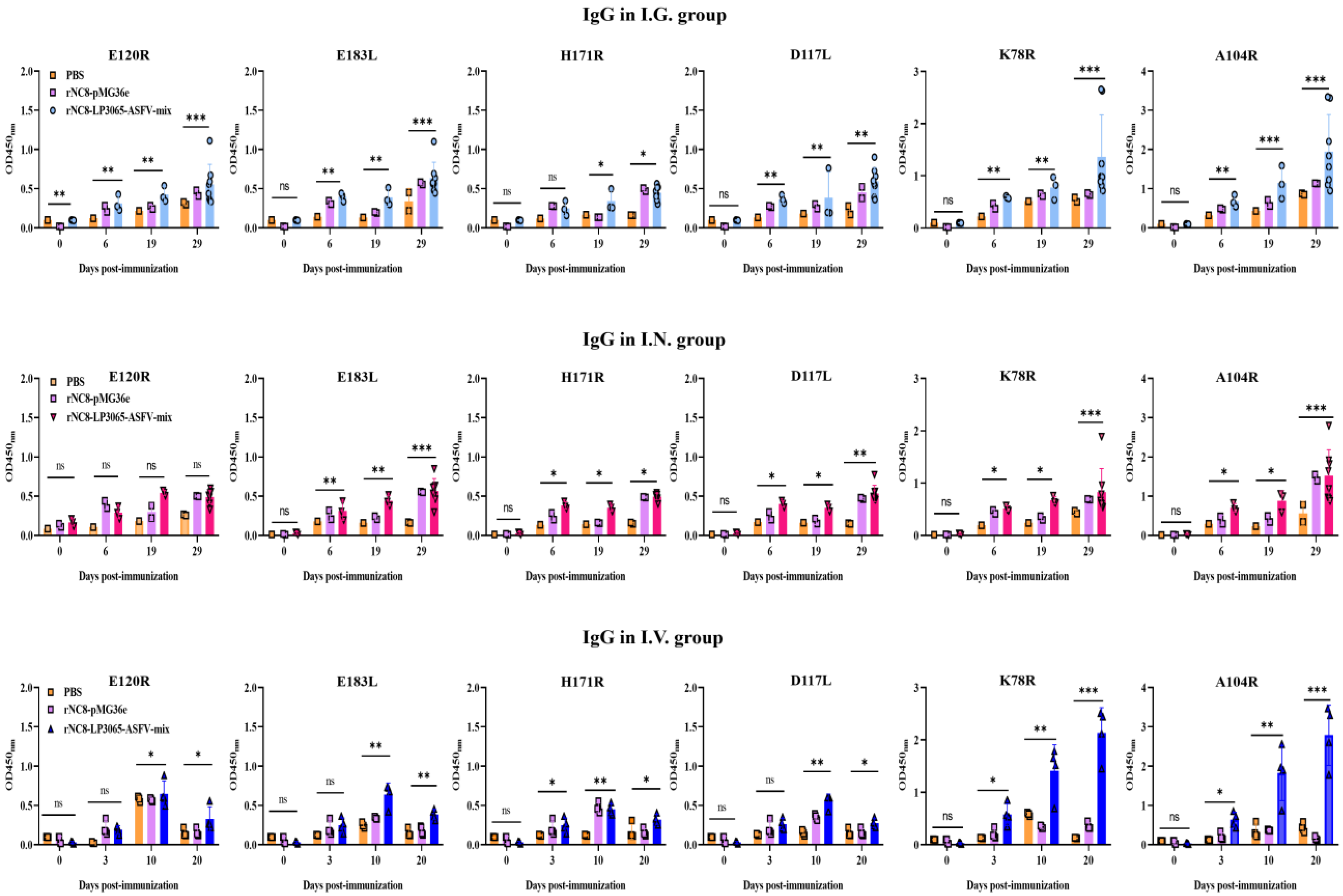

3.2. Analysis of IgG Antibodies Production by rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-Mix in Mice

To further evaluate the role of rNC8-LP3065-ASFV strains in humoral immune response, ELISA was used to evaluate the serum antibodies induced by rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-mix in the immunized mice. The results indicated that oral immunization with rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-mix induced higher IgG levels in the BALF compared with the rNC8-pMG36e and PBS control groups. The oral immunization results indicated a notable elevation in IgG levels in the mice immunized with rNC8-LP3065-D117L, rNC8-LP3065-K78R, rNC8-LP3065-A104R and low levels of rNC8-LP3065-H171R, rNC8-LP3065-E120R, and rNC8-LP3065-E183L antibodies, while I.N. immunization induced high IgG levels in rNC8-LP3065-E120R and low levels in rNC8-LP3065-D117, rNC8-LP3065-K78R, rNC8-LP3065-A104R and rNC8-LP3065-E183L, rNC8-LP3065-H171R as shown in (

Figure 3). The levels of IgG antibodies in rNC8-LP3065-A104R and rNC8-LP3065-K78R substantially increased, while low levels of IgG were observed in the mice I.V. immunized with rNC8-LP3065-E183L, rNC8-LP3065-E120R and rNC8-LP3065-H171R. The data indicate that immunization of rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-mix can induce significant humoral immune responses

via I.G. gavage but not

via I.N. and I.V. administration.

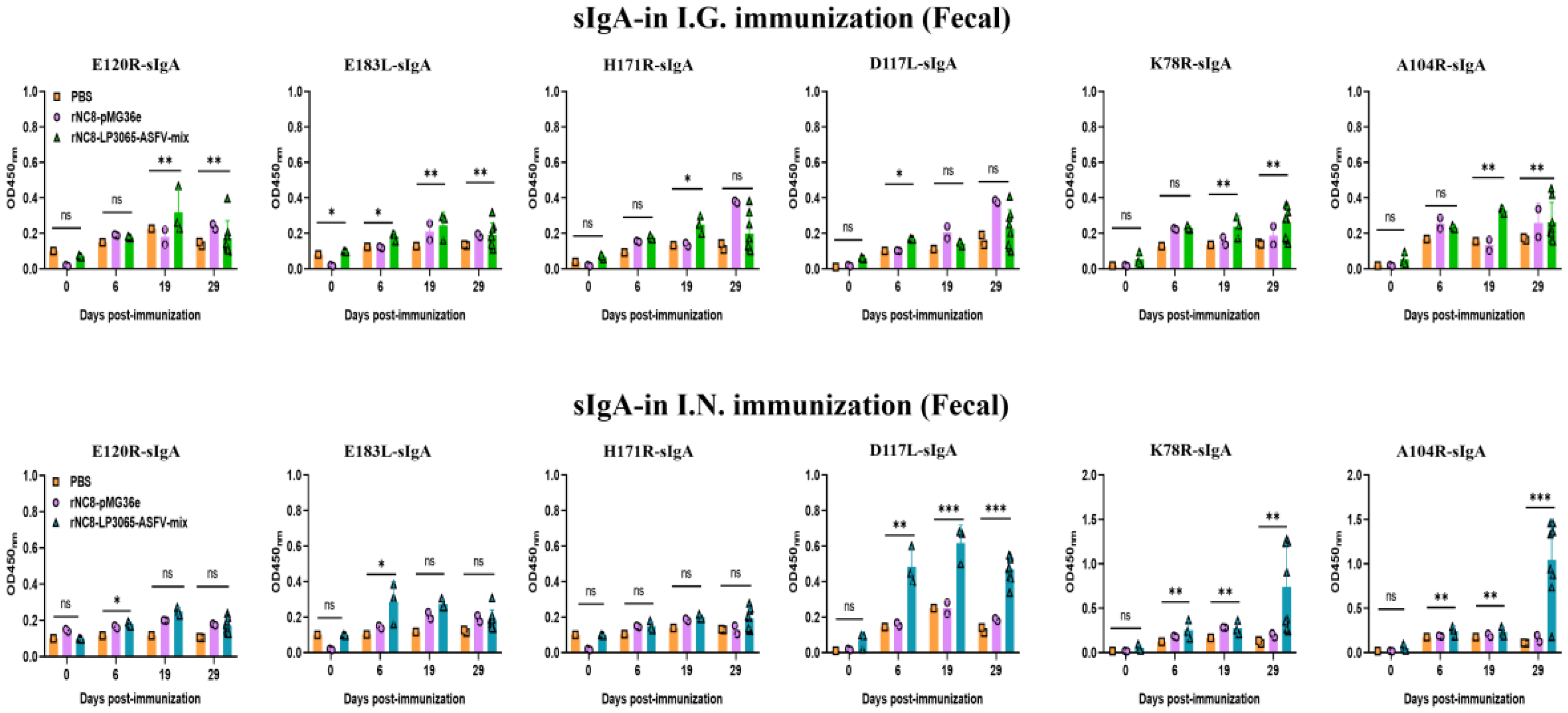

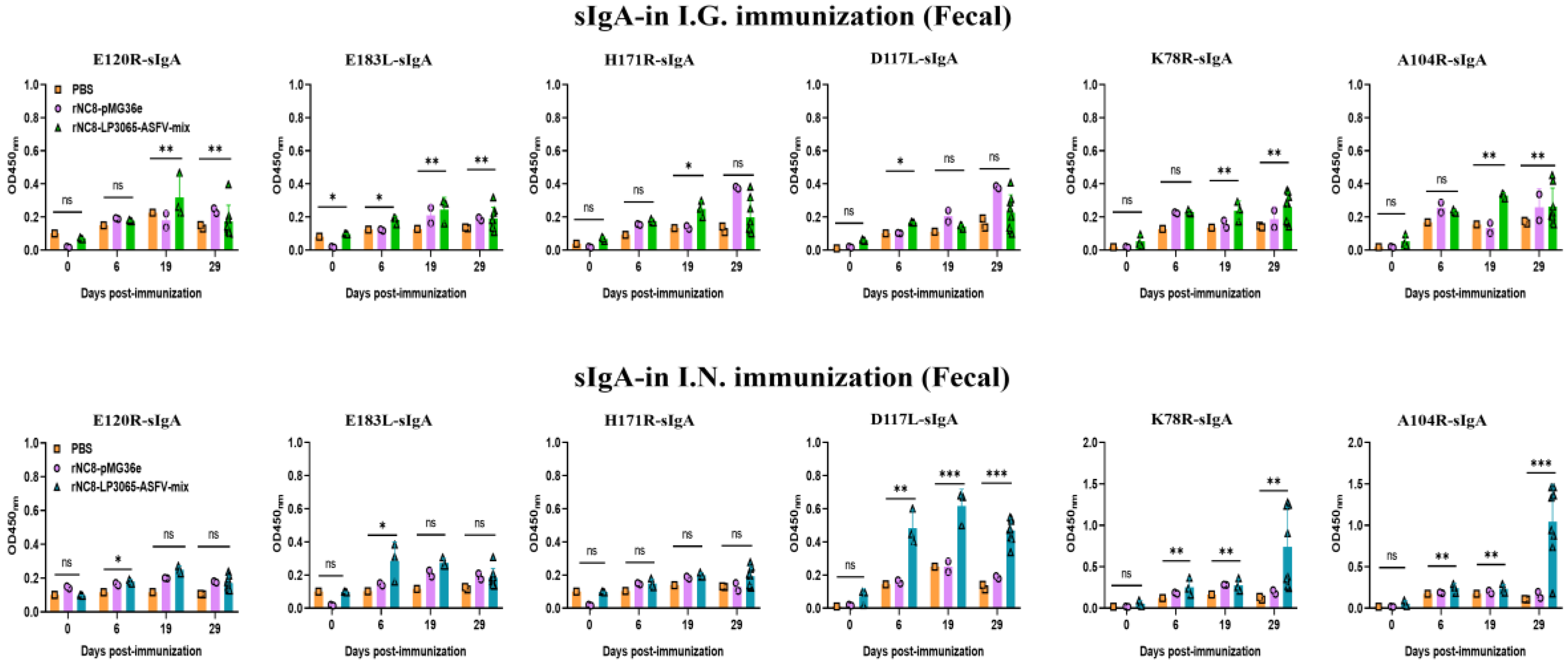

3.3. rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-Mix Induced High-Levels Secretory IgA Antibodies in Mice

We investigated whether rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-mix could enhance the sIgA antibody responses triggered by oral or intranasal immunization. BALB/c mice received three inoculations, each consisting of three daily doses, either with rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-mix or rNC8-pMG36e. Over time, we observed the development of anti-ASFV antibody responses in both the gut and circulation. For the sIgA levels of the I.G. immunized mice, a significant increase in antibody production was detected in the feces of the immunized mice with rNC8-LP3065-A104R, rNC8-LP3065-K78R, and low levels between rNC8-LP3065-E120R and rNC8-LP3065-E183L. rNC8-LP3065-A104R showed the highest levels of antibody production in the feces of the I.G. immunized group. Conversely, sera from the constructs rNC8-LP3065-D117L, and rNC8-LP3065-H171R were not significant. On the other hand, in the BALF of the I.G. group, rNC8-LP3065-A104R, and rNC8-LP3065-D117L produced significant antibody levels, and rNC8-LP3065-K78R was insignificant. The antibodies titers from the rNC8-LP3065-E120R, rNC8-LP3065-E183L, and rNC8-LP3065-H171R were not significant (

Figure 4).

The ELISA results also showed that the mice immunized I.N. with the rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-mix had significantly higher sIgA levels in their feces compared with the rNC8-pMG36e control mice. The sIgA from feces showed that the mice immunized I.N. with rNC8-LP3065-E120R, rNC8-LP3065-K78R, and rNC8-LP3065-A104R produced higher levels of sIgA antibodies levels in feces, while rNC8-LP3065-H171R, rNC8-LP3065-E183L, and rNC8-LP3065-D117L remained not significant compared with the PBS control. In the BALF of the I.N. immunized mice, there was a significant rise in sIgA levels in the mice immunized with the recombinant strains rNC8-LP3065-E120R, rNC8-LP3065-K78R, and rNC8-LP3065-A104R, while low levels of antibodies were detected in rNC8-LP3065-E183L and rNC8-LP3065-D117L. The construct rNC8-LP3065-H171R was not significant which suggests varying efficacy depending on the route of administration and the specific strains used (

Figure 5).

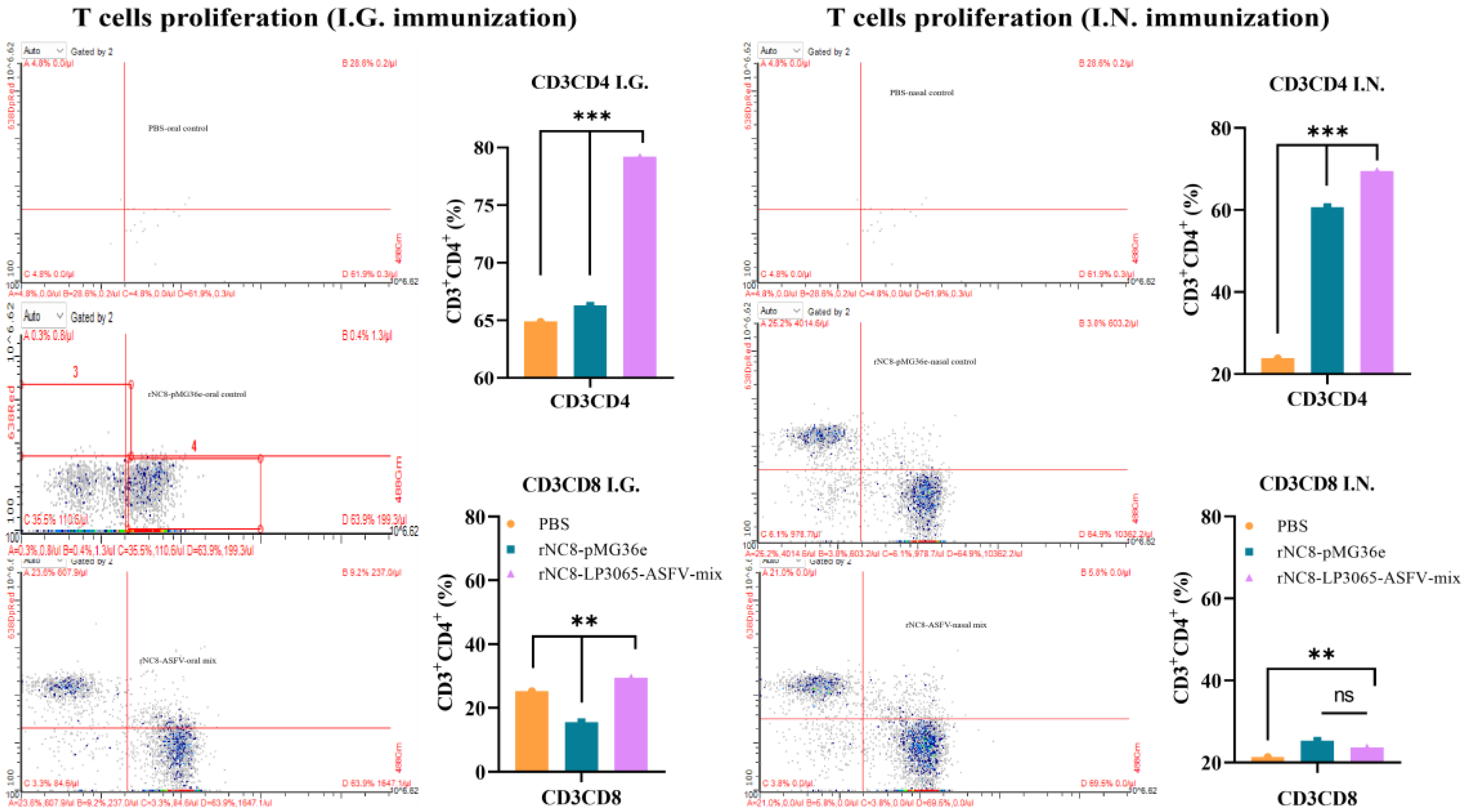

3.4. rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-Mix Induces T Cell Proliferation in Mice

To further assess the ability of rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-mix to induce cellular immune responses, flow cytometry was employed to evaluate T cell proliferation induced by rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-mix. The mice were immunized I.G. and I.N. with rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-mix, rNC8-pMG36e (negative control), or PBS (mock control). The spleens were collected following the euthanasia of the immunized mice.

CD3, CD4, and CD8 are surface molecular markers on T cells that could distinguish the cytotoxic T cells and helper T cells. These T cells also promote natural killer (NK) cells activity, antigen presentation, and enhancing macrophage lysosomal activity. Flow cytometry analysis revealed a significant increase in CD3

+CD4

+ T cells in the spleens of the I.G. immunized mice with rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-mix, while CD3

+CD8

+ T cells were not significantly increased compared with rNC8-pMG36e control and in the I.N. immunized mice, both CD3

+CD4

+ and CD3

+CD8

+ T cells were not significant with control group. The I.G. immunized group induced more T cell proliferation compared with the I.N. administered group and PBS control group, indicating enhanced cellular response in the I.G. immunized mice

(Figure 6).

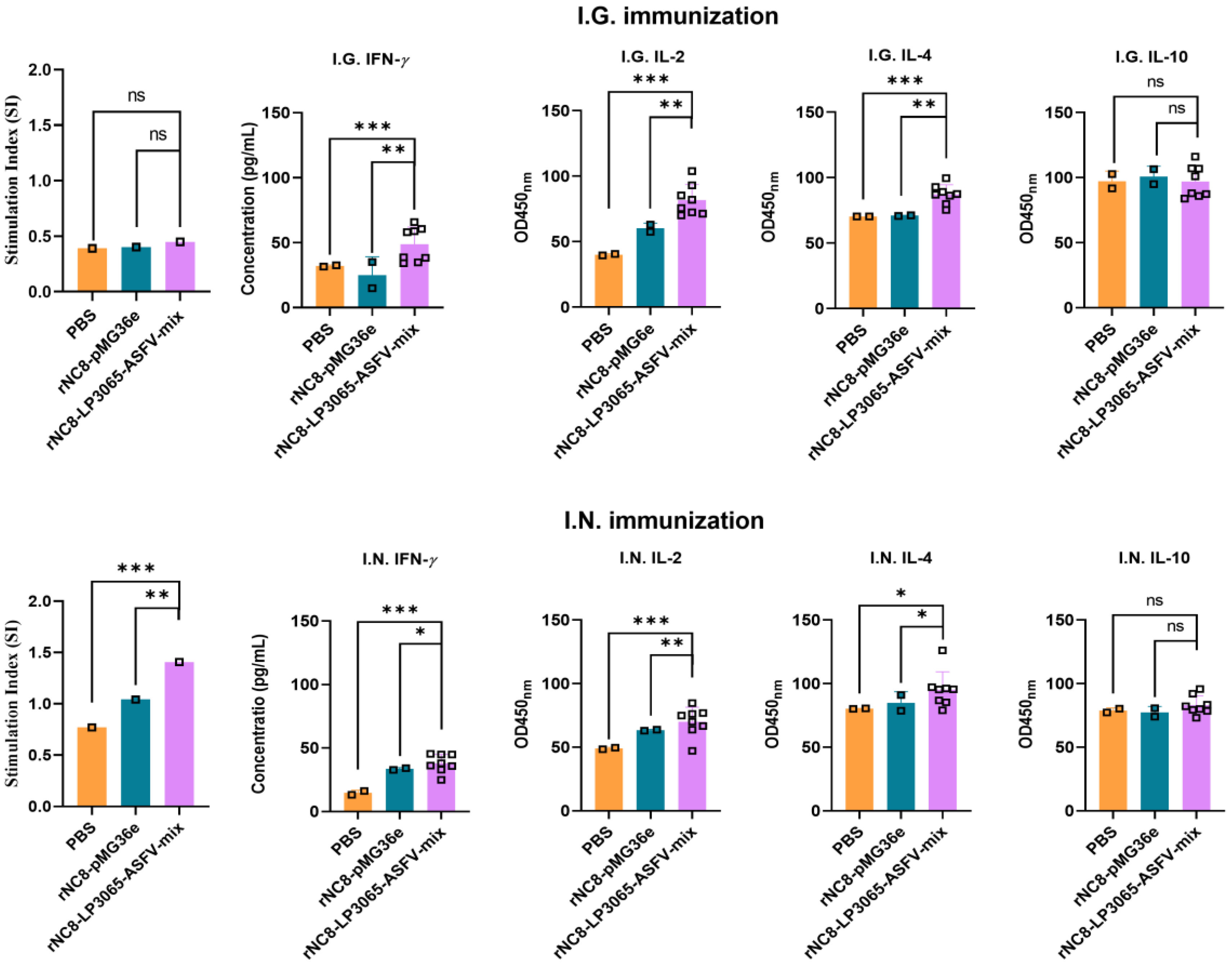

3.5. Intranasal Immunization of rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-Mix Increased Cytokines Levels

To assess the immune responses induced by rNC8-LP3065-ASFV-mix in mice, cytokines including IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-

γ, in the sera of the immunized mice were assessed using ELISA. IFN-

γ and IL-2 are produced by Th1 cells and enhance the activation and proliferation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), macrophages, and NK cells, as well as promoting CD8

+ T cell responses and innate immune functions. IL-4 and IL-10, characteristic of Th2 responses, promote B cell proliferation and differentiate in to plasma cells, stimulating antibody production and supporting humoral immune responses, while dampening inflammation. The results revealed significantly higher levels of IFN-

γ and IL-10 in the serum of mice receiving I.N. administration compared with the control group (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

The swine breeding industries have undergone rapid development in recent years. Nevertheless, infectious diseases remain the most significant challenge to the further progress of these industries. ASFV infection has caused serious economic losses for many countries engaged in industrialized swine production. ASF is an extremely infectious illness and causes significant damage to the swine production industry [

20]. Adaptive immunization through antibody mediation offers protection against invading pathogens. Hence, there is a critical need to devise innovative approaches for adaptive immunity to the ASFV infection. Systemic and mucosal immunity serve as the defense lines against invading infections in the body. In animals, mucosal immunization stands out for its unparalleled antigen-presetting capability. The lumen of the intestine and the respiratory tract is a central carrier of immune cells in animals and is closely linked to the microenvironment. Maintaining a harmonious balance within the mucosal immune system of the gut and nasal mucosa is of paramount importance in defense against pathogens. An essential feature of the mucosal immune system is its ability to mount protective responses, while avoiding excessive inflammation [

21]. This is achieved through the production of secretory IgA (sIgA), the predominant antibody class found in mucosal secretions. sIgA acts as a front-line defense by binding pathogens and preventing their attachment to mucosal surfaces, thereby neutralizing them before they can invade host cells [

22].

The cell wall anchoring enables exogenous protein display on LAB surfaces, enhancing mucosal immune recognition [

23]. By fusing the carrier protein to an LPxTG-type cell wall anchor, proteins can be targeted to immune cells [

24]. The C-terminus consists of an LPxTG motif followed by hydrophobic amino acids and a short tail of positively charged residues. The protein anchored by LPxTG contains an N-terminal signal peptide sequence that triggers the export of the protein across the cell membrane

via the secretory pathway [

25]. Upon release of the sortase enzyme, the Thr-Gly bond in the LPxTG motif splits, and the protein is covalently anchored to the peptidoglycan of the cell wall

via the Thr residue [

26].

In L. plantarum WCFS1, there are 26 different LPxTG motifs in the genome. In this study, we used L. plantarum WCFSI-originated LPxTG surface anchoring motif, i.e., LP3065, with 141 residues annotated as cell wall anchoring proteins. ASFV antigens were ligated at the junctures between XhoI and BamHI with the LPxTG motif for surface expression.

Given the absence of studies on the surface expression of

E120R, E183L, D117L, H171R, K78R, and

A104R of the ASFV antigens, our focus primarily delved into the role of these antigens surface expression by a probiotic strain in cellular and humoral immune responses, such as helper T cell differentiation and IgG antibody production. Based on these required characteristics, NC8 was selected as a vaccine candidate, because it has been widely used in livestock as a delivery vehicle for the expression of multiple viral integral membrane proteins [

15,

27]. Probiotic-based vaccines can regulate immune responses and activate antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as macrophages and DCs [

28,

29]. DCs are recognized as professional APCs. They initiate a primary immune response to pathogen challenge. In addition, NC8 has the capability for high recombinant protein expression, efficient expression, and secretion of envelope proteins, and it generates potent immune protection against viral infections [

30].

Six ASFV antigens were selected for ligation with the pMG36e-LP3065 vector to anchor to the surface of NC8 because, in previous studies, these antigens had been shown to react with the sera from recovered animals [

26,

31]. In this investigation, the E120R, E183L, D117L, H171R, K78R, and A104R proteins of ASFV were successfully ligated and expressed with a surface anchoring domain and proteins expressed on the rNC8 surface. The results showed that the use of rNC8-LP3065-E120R, rNC8-LP3065-E183L, rNC8-LP3065-D117L, rNC8-LP3065-H171R, rNC8-LP3065-K78R, and rNC8-LP3065-A104R as antigens for vaccination in mice proved to be effective and safe in all routes of administration. After immunization with the recombinant strains, all the mice remained in good health and none of them showed clinical signs.

In the immunized mice, the ELISA results showed that the levels of the specific IgG antibodies against various proteins vary significantly due to the immune responses elicited by the specific antigens. The mice immunized with the recombinant strains rNC8-LP3065-K78R and rNC8-LP3065-A104R

via the I.V. route showed a significant increase in specific IgG antibody titers, while the recombinant strains rNC8-LP3065-E183L and rNC8-LP3065-H171R induced low antibody titers. However, amidst this variability, certain antigens exhibit remarkable efficacy in inducing IgG production. Moreover, rNC8-LP3065-K78R and rNC8-LP3065-A104R increased the production of IgG by approximately 3-fold in the mice, indicating that infection protection may be related to the production of specific antibodies against antigens compared with the I.G. and I.N. administered mice. The levels of sIgA were higher in the mice administered

via the I.G. route than those in the mice

via the I.N. route. This might be because the immune system is well developed in intestinal mucosa in terms of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues (MALT). These lymphoid tissues are located beneath the mucosal epithelium of the intestine. These MALTs are similar to peripheral lymph nodes with an abundant supply of B cells and M cells for capturing the invading pathogens [

32]. Secretory IgA (sIgA) is adapted structurally to resist mucosal environment and enzymatic breakdown. It is produced under tight control via T-independent and T-dependent mechanisms that enable immune responses against commensal and pathogenic microbes. Because the majority of infections commence via mucosal surfaces, vaccines are currently being developed that aim to elicit pathogen-specific sIgA in addition to systemic immunity. The efficacy of sIgA response with I.G. or I.N. vaccination is dependent on delivery systems designed to optimize the targeting of immune cells as well as anatomical regions. This heightened immune response suggests a potential for these proteins to serve as effective immunogens, warranting further investigation into their utility in vaccine development and immune modulation strategies.

The safety of this system has also attracted attention. The ELISA analysis showed that surface expression of antigens conferred protection against ASF in mice, while being able to induce specific IgG antibodies and cellular immunity against ASFV and improve specific humoral immune responses. Future stidies should evaluate rNC8 in porcine models to identify the ASFV antigens that can elict stronger immune responses.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, the surface display of the ASFV antigens could increase the adaptive immune responses in a mouse model by increasing the specific antibodies and CD3+CD4+, and CD3+CD8+ T cell responses.

Our findings imply that rNC8 exhibited a significant rise in serum IgG antibodies in the immunized mice. rNC8 also increased the activation of CD3+CD4+ T cells in the I.N. group, while CD3+CD8+ T cells in both the I.N. and I.M. groups.

Author Contributions

Yuan Sun, and Hua-Ji Qiu designed the study. Moon Assad, Hongxia Wu, Li Jia, and Zhiqiang Xu performed the experiments. Moon Assad wrote the manuscript. Yongfeng Li, Lian-Feng Li, Tao Wang, Yanjin Wang, Jingshan Huang, and Tianqi Gao reviewed the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China in the 14th Five-Year Period (grant code no. 2021YFD1801403).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yuan Sun, Hongxia Wu, and Hua-Ji Qiu designed the study. Moon Assad, Hongxia Wu, Li Jia, and Zhiqiang Xu performed the experiments. Moon Assad wrote the manuscript. Yongfeng Li, Lian-Feng Li, Tao Wang, Yanjin Wang, Jingshan Huang, and Tianqi Gao reviewed the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ASF |

African Swine Fever |

| LAB |

Lactic acid bacteria |

| NC8 |

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum NC8 |

| ASFV |

African Swine Fever virus |

| DCs |

Dendritic cells |

| ELISA |

Enzyme linked immunosorbant assay |

| WOAH |

World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) |

| ORF |

open reading frames |

| dpi |

Days post immunization |

References

- Blome, S.; Franzke, K.; Beer, M. African Swine Fever - A Review of Current Knowledge. Virus Res 2020, 287, 198099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penrith, M.L.; Kivaria, F.M. One Hundred Years of African Swine Fever in Africa: Where have We been, Where are We Now, Where are We Going? Transbound Emerg Dis 2022, 69, e1179–e1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, P.; Shan, H.; Cai, X. Orally Administered recombinant Lactobacillus Expressing African Swine Fever Virus Antigens that Induced Immunity Responses. Front Microbiol 2023, 13, 1103327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Sun, E.; Huang, L.; Ding, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, T. Highly Lethal Genotype I and II Recombinant African Swine Fever Viruses Detected in Pigs. Nat Comm 2023, 14, 3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, I.; Alonso, C. African Swine Fever Virus: A Review. Viruses 2017, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ai, Q.; Huang, S.; Ou, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tong, T.; Fan, H. Immune Escape Mechanism and Vaccine Research Progress of African Swine Fever Virus. Vaccines 2022, 10, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteves, A.; Marques, M.I.; Costa, J.V. Two Dimensional Analysis of African Swine Fever Virus Proteins and Proteins Induced in Infected Cells. Virology 1986, 152, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, H.; Liu, B.; Lv, T.; Yang, C.; Chen, S.; Feng, L.; Lai, L.; Duan, Z.; Chen, X. A New Vaccination Regimen Using Adenovirus Vectored Vaccine Confers Efective Protection Against African Swine Fever Virus in Swine. Emerg Microbes & Infect 2023, 12, 2233643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Puertas, P.; Rodriguez, F.; Oviedo, J.M.; Brun, A.; Alonso, C.; Escribano, J.M. The African Swine Fever Virus Proteins p54 and p30 are Involved in Two Distinct Steps of Virus Attachment and Both Contribute to the Antibody Mediated Protective Immune Response. Virology 1998, 243, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borca, M.V.; Ramirez-Medina, E.; Silva, E.; Vuono, E.; Rai, A.; Pruitt, S.; Holinka, L.G.; Velazquez-Salinas, L.; Zhu, J.; Gladue, D.P. Development of A Highly Effective African Swine Fever Virus Vaccine by Deletion of the I177L Gene Results in Sterile Immunity Against the Current Epidemic Eurasia Strain. J Virol 2020, 94, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejo, A.; Matamoros, T.; Guerra, M.; Andres, G. A Proteomic Atlas of the African Swine Fever Virus Particle. J Virol 2018, 92, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhao, Z.; Bi, Y.; Sun, J.; Peng, R.; Song, H.; Zhu, D.; et al. Cryo-EM Structure of the African Swine Fever Virus. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejo, A.; Matamoros, T.; Guerra, M.; Andrés, G. A proteomic Atlas of the African Swine Fever Virus Particle. J Virol 2018, 92, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, N.; Qu, H.; Xu, T.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, S. Summary of the Current Status of African Swine Fever Vaccine Development in China. Vaccines 2023, 11, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, G.; Ai, C.; Hu, M.; Liu, X.; Tian, F.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, M. Modulation of Peanut Induced Allergic Immune Responses by Oral Lactic Acid Bacteria Based Vaccines in Mice. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2014, 98, 6353–6364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arena, M.P.; Elmastour, F.; Sane, F.; Drider, D.; Fiocco, D.; Spano, G.; Hober, D. Inhibition of Coxsackievirus B4 by Lactobacillus plantarum. Microbiol Res 2018, 210, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yu, Q.; Xie, L.; Ran, L.; Wang, K.; Yang, Y.; Gan, L.; Song, Z. Inhibitory Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum Metabolites on Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Replication. Res Vet Sci 2021, 139, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.L.; Wang, J.H.; Zhao, W.; Shi, C.W.; Yang, K.D.; Niu, T.M.; Yang, G.L.; Cao, X.; Jiang, Y.L.; Wang, J.Z.; et al. Lactobacillus plantarum Surface Displayed ASFV (p54) with Porcine IL-21 Generally Stimulates Protective Immune Responses in Mice. AMB Express 2021, 11, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, A.; Huang, J.; Song, X.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wu, H.; Qiu, H. Immune Responses Induced by a recombinant Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Surface-Displaying the gD Protein of Pseudorabies Virus. Viruses 2024, 16, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklue, T.; Sun, Y.; Abid, M.; Luo, Y.; Qiu, H.J. Current Status and Evolving Approaches to African Swine Fever Vaccine Development. Transbound Emerg Dis 2020, 67, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carasi, P.; Racedo, S.M.; Jacquot, C.; Romanin, D.E.; Serradell, M.; Urdaci, M. Impact of Kefir Derived Lactobacillus kefiri on the Mucosal Immune Response and Gut Microbiota. J Immunol Res 2015, 2015, 361604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Jung, D.I.; Yang, I.Y.; Jang, S.H.; Kim, J.; Truong, T.T.; Pham, T.V.; Truong, N.U.; Lee, K.Y.; Jang, Y.S. Application of an M-cell-Targeting Ligand for Oral Vaccination Induces Efficient Systemic and Mucosal Immune Responses Against a Viral Antigen. Int Immunol 2013, 25, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.H.; Nguyen, M.T.; Das, A.; Ton-That, H. Anchoring Surface Proteins to the Bacterial Cell Wall by Sortase Enzymes: How it Started and What We Know Now. Curr Opin Microbiol 2021, 60, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischetti, V.A.; Pancholi, V.; Schneewind, O. Conservation of a Hexapeptide Sequence in the Anchor Region of Surface Proteins from Gram Positive Cocci. Mol Microbiol 1990, 4, 1603–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ton-That, H.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Faull, K.F.; Schneewind, O. Anchoring of Surface Proteins to the Cell Wall of Staphylococcus aureus: Sortase Catalyzed in vitro Transpeptidation Reaction Using LPxTG Peptide and NH2-Gly3 Substrates. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 9876–9881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazmanian, S.K.; Liu, G.; Ton-That, H.; Schneewind, O. Staphylococcus aureus Sortase, An Enzyme that Anchors Surface Proteins to the Cell Wall. Science 1999, 285, 760–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.Y.; Yang, G.L.; Jin, Y.B.; Liu, J.; Chen, H.L.; Wang, P.B.; Jiang, Y.L.; Shi, C.W.; Huang, H.B.; Wang, J.Z.; et al. Construction and Immunogenicity Analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum Expressing a Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus S Gene Fused to a DC-targeting Peptide. Virus Res 2018, 247, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, Z.H.; Li, Y.X.; Xu, H.L.; Fang, W.H.; He, F. Targeted Delivery of Nanovaccine to Dendritic Cells via DC-Binding Peptides Induces Potent Antiviral Immunity in vivo. Int J Nanomed 2022, 17, 1593–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel, T.J.; Morris, C.; Brumlik, M.; Landry, S.J.; Finstad, K.; Nelson, A.; Joshi, V.; Hawkins, C.; Alarez, X.; Lackner, A.; et al. Peptides Identified through Phage Display Direct Immunogenic Antigen to Dendritic Cells. J Immunol 2004, 172, 7425–7431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michon, C.; Langella, P.; Eijsink, V.G.; Mathiesen, G.; Chatel, J.M. Display of Recombinant Proteins at the Surface of Lactic Acid Bacteria: Strategies and Applications. Microb Cell Fact 2016, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xie, M.; Wu, W.; Chen, Z. Structures and Functional Diversities of ASFV Proteins. Viruses 2021, 13, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodrow, K.A.; Bennett, K.M.; Lo, D.D. Mucosal Vaccine Design and Delivery. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2012, 14, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

The schematic diagram for the immunization in a mouse model. Schematic diagram for I.G. (A), I.N. (B), and I.V. immunization (C).

Figure 1.

The schematic diagram for the immunization in a mouse model. Schematic diagram for I.G. (A), I.N. (B), and I.V. immunization (C).

Figure 2.

Construction of the recombinant vectors expressing six ASFV antigens fused with the LP3065 surface anchoring motif. (A) The schematic diagram for the construction of vectors. (B) Identification of rNC8-LP3065-ASFV antigens by immunofluorescence assay. The confocal microscope was used to observe the surface protein of the recombinant bacterial strains. Fluorescence was observed on the surface of LAB. (C) Western blotting analysis of the rNC8 strains expressing the ASFV viral proteins anchored with LP3065. All the indicated rNC8 strains were detected by Western blotting. The anti-His tag antibodies were used as primary antibodies and goat anti-mouse FITC was used as secondary antibodies. The arrow represents protein bands expressed by the rNC8 strains. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Figure 2.

Construction of the recombinant vectors expressing six ASFV antigens fused with the LP3065 surface anchoring motif. (A) The schematic diagram for the construction of vectors. (B) Identification of rNC8-LP3065-ASFV antigens by immunofluorescence assay. The confocal microscope was used to observe the surface protein of the recombinant bacterial strains. Fluorescence was observed on the surface of LAB. (C) Western blotting analysis of the rNC8 strains expressing the ASFV viral proteins anchored with LP3065. All the indicated rNC8 strains were detected by Western blotting. The anti-His tag antibodies were used as primary antibodies and goat anti-mouse FITC was used as secondary antibodies. The arrow represents protein bands expressed by the rNC8 strains. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Figure 3.

Specific IgG antibodies in the immunized mice were detected by ELISA. Forty mice were divided into four groups (n = 10). The mice were immunized with 200 µL (109 CFU/mouse) via the I.G. route or 20 µL (109 CFU/mouse) via the I.N. route. The sera were collected at 0, 6, 19, and 20 dpi. ELISA was performed to check the IgG levels. Bars represent means ± SDs of the independent experiments; ns: not significant P ≥ 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Specific IgG antibodies in the immunized mice were detected by ELISA. Forty mice were divided into four groups (n = 10). The mice were immunized with 200 µL (109 CFU/mouse) via the I.G. route or 20 µL (109 CFU/mouse) via the I.N. route. The sera were collected at 0, 6, 19, and 20 dpi. ELISA was performed to check the IgG levels. Bars represent means ± SDs of the independent experiments; ns: not significant P ≥ 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Specific sIgA antibodies were detected from the feces of the I.G. immunized mice by ELISA. Forty mice were divided into four groups, i.e., I.G. (n = 20), NC8 empty vector (n = 12), and PBS control (n = 8). The mice were immunized with 200 µL (109 CFU/mL) via the I.G. or I.N. route. The feces were collected at 0, 6, 19, and 28 dpi. The feces were homogenized in DMEM and, supernatants from each mouse group were collected. ELISA was performed to check the sIgA levels. Bars represent SDs of three independent experiments; ns: not significant P ≥ 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Specific sIgA antibodies were detected from the feces of the I.G. immunized mice by ELISA. Forty mice were divided into four groups, i.e., I.G. (n = 20), NC8 empty vector (n = 12), and PBS control (n = 8). The mice were immunized with 200 µL (109 CFU/mL) via the I.G. or I.N. route. The feces were collected at 0, 6, 19, and 28 dpi. The feces were homogenized in DMEM and, supernatants from each mouse group were collected. ELISA was performed to check the sIgA levels. Bars represent SDs of three independent experiments; ns: not significant P ≥ 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Specific sIgA antibodies from the BALF of the I.N. immunized mice were detected by ELISA. Forty mice were divided into four groups, i.e., I.N. (n = 20), NC8 empty vector (n = 12), and PBS control (n = 8). The mice were immunized with 200 µL (109 CFU/mL) via the I.G. and I.N. routes. The lungs were collected at 0, 6, 19, and 28 dpi from each mouse group and homogenized in DMEM, and supernatants were subjected to ELISA to check the sIgA levels. Bars represent SDs of three independent experiments; ns: not significant P ≥ 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Specific sIgA antibodies from the BALF of the I.N. immunized mice were detected by ELISA. Forty mice were divided into four groups, i.e., I.N. (n = 20), NC8 empty vector (n = 12), and PBS control (n = 8). The mice were immunized with 200 µL (109 CFU/mL) via the I.G. and I.N. routes. The lungs were collected at 0, 6, 19, and 28 dpi from each mouse group and homogenized in DMEM, and supernatants were subjected to ELISA to check the sIgA levels. Bars represent SDs of three independent experiments; ns: not significant P ≥ 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Figure 6.

The CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T cells of the I.G. or I.N. immunized mice by flow cytometry. The spleen samples were harvested from the I.G. or I.N. immunized mice after euthanasia. The T cells from the spleens of the immunized mice were isolated by mouse spleen lymphocyte isolation kit and treated with anti-mouse CD3, CD4, and CD8 antibodies for 30 min at 4°C. The treated cells were washed twice with PBS and subjected to flow cytometry. Bars represent SDs of three independent experiments; ns: not significant P ≥ 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Figure 6.

The CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T cells of the I.G. or I.N. immunized mice by flow cytometry. The spleen samples were harvested from the I.G. or I.N. immunized mice after euthanasia. The T cells from the spleens of the immunized mice were isolated by mouse spleen lymphocyte isolation kit and treated with anti-mouse CD3, CD4, and CD8 antibodies for 30 min at 4°C. The treated cells were washed twice with PBS and subjected to flow cytometry. Bars represent SDs of three independent experiments; ns: not significant P ≥ 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Figure 7.

The proliferation of the T lymphocytes in the immunized mice. The splenic T lymphocytes were isolated and seeded in 96-well microtiter plates. The plates were incubated for 72 h at 37°C and then the CCK8 reagent was added into each well and again incubated. After incubation for 3 h at 37°C in the dark, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader. The levels of Th1 (IFN-γ and IL-2) and Th2 (IL-4 and IL-10) cytokines in the sera of the I.G. or I.N. immunized mice; ns: not significant P ≥ 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Figure 7.

The proliferation of the T lymphocytes in the immunized mice. The splenic T lymphocytes were isolated and seeded in 96-well microtiter plates. The plates were incubated for 72 h at 37°C and then the CCK8 reagent was added into each well and again incubated. After incubation for 3 h at 37°C in the dark, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader. The levels of Th1 (IFN-γ and IL-2) and Th2 (IL-4 and IL-10) cytokines in the sera of the I.G. or I.N. immunized mice; ns: not significant P ≥ 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Table 1.

Sequences of the primers used in this study.

Table 1.

Sequences of the primers used in this study.

| Primers |

Sequence a (5′-3′) |

| LP3065-F |

GGCGGCCGCGGCGGATCTAGAATGCCGAATAAATGGTGGCGATT |

| LP3065-R |

CACGTGCTGTAATTTGAAGCTTTTACGCATTCCGTTCACCCCCAT |

| E120R-F |

ACCGCTCGAGATGGCTGATTTTAATTCACCAATTC |

| E120R-R |

CGGGATCCGCCGCCTTTAGATTTATGAGATG |

| E183L-F |

ACCGCTCGAGATGGATTCAGAATTTTTCCAACCA |

| E183L-R |

CGGGATCCGCCGCCAAGAGAATTTTCTAAATC |

| D117L-F |

ACCGCTCGAGATGGATACAGAAACTTCACCTCTTCTT |

| D117L-R |

CGGGATCCGCCGCCTGAATGTGCAAGTTCAG |

| H171R-F |

ACCGCTCGAGATGGTTGTTTATGATCTTCTTGTTTCA |

| H171R-R |

CGGGATCCGCCGCCATTTTTAATAGAAAACA |

| K78R-F |

ACCGCTCGAGATGCCTACAAAAGCTGGCACAAAAAGTACCGC |

| K78R-R |

CGGGATCCTTTTGACCGTTTAATTTTTTT |

| A104R-F |

ACCGCTCGAGATGTCGACAAAAAAAAAGCCCACAATTACCAAGCAAGA |

| A104R-R |

CGGGATCCGTTTAACATATCATGGACAGGT |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).