1. Introduction

Medical errors, broadly encompassing procedural adverse events, in-hospital infections, and various other malfunctions and malpractices including even time-delays, constitute a significant and persistent global challenge in healthcare, affecting up to 25% of inpatient operations in industrialized countries [

1]. These errors lead to over 7 million disabling adverse events and 1 million deaths annually, escalating costs and eroding trust in healthcare systems [

2]. Unlike high-risk industries like aviation, which use systematic error prevention [

3], surgery lags in adopting proactive strategies, necessitating innovative solutions like machine learning (ML) to enhance patient safety [

4]. This research investigates the potential of ML to predict and mitigate surgical errors, focusing specifically on preventable adverse events in general surgery. These malpractices and malfunctions threaten patient safety, escalate healthcare expenses, and undermine public confidence in medical institutions [

5]. Unlike high-risk sectors such as aviation and the military—where errors are accepted as unavoidable but controllable through systematic prevention measures [

3]—healthcare has been slower to adopt similarly rigorous strategies, despite the severe human and financial consequences [

6]. Industries like aviation employ simulations and controlled environments to analyze and prevent errors [

7], yet such approaches are less prevalent in surgery, where risks are high and environments unpredictable [

2]. While medication-related errors have been widely studied, surgical errors—often tied to procedural adverse events or chaotic operating conditions [

8]—remain a persistent challenge. Initiatives like the UK’s National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) have sought to improve safety, but the inherently volatile nature of surgery continues to hinder progress [

5]. The 1999 To Err Is Human report by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) underscored the scale of medical errors, urging systemic reforms [

6]. Later research has further confirmed these concerns, calling for novel interventions [9, 10]. Surgical errors stem from diverse causes, including technical failures, miscommunication, and flawed decision-making [

5]. Surgeons’ fatigue, excessive workloads, and skill disparities also contribute significantly [

5], with recent studies emphasizing procedural lapses and communication failures [

8]. This study hypothesizes that ML can accurately predict the risk of preventable surgical adverse events, enabling proactive interventions. Conventional error analysis, such as retrospective reviews, offers limited predictive power, leaving gaps in proactive risk mitigation.

1.1. Global and European Surgical Error Rates

Medical error rates, mainly in surgery departments, are a complex issue. Global estimates suggest that up to 25% of inpatient operations in industrialized countries experience adverse events, a substantial portion of which may be preventable. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports over 300 million surgical procedures annually, with at least 7 million people experiencing disabling adverse events and over 1 million deaths linked to surgical care [

1]. In Europe, recent research, such as a 2024 study published in the BMJ, found that more than one-third of surgical patients in hospital settings experience adverse events, with at least 20% attributable to preventable medical errors [

11]. This highlights a significant overlap between global and European trends, emphasizing the widespread nature of the problem. The EU also reports around 3.2 million patients annually acquiring healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) linked to surgery, resulting in 37,000 deaths, highlighting the ongoing challenge [

1]. Efforts like the WHO’s Surgical Safety Checklist have shown promise, reducing adverse events by over 30% in some settings. However, factors such as communication failures, fatigue, and complex procedures continue to drive error rates, making it a persistent concern as of today.

1.2. Detailed Analysis and Supporting Information

A 2023 WHO report further noted that crude mortality rates after major surgery range from 0.5% to 5%, underscoring the variability and severity of outcomes. Additional insights come from studies like one conducted in California, published in JAMA Network Open in 2021, which examined surgical "never events" and found persistent issues despite safety protocols [

12]. While this US-based study provides a comparative perspective on systemic challenges contributing to error rates globally, the focus of this paper remains on the European context. A 2024 study published in the BMJ, led by researchers from Harvard University and analyzing outcomes for 1,009 surgical patients in Massachusetts hospitals in 2018, found that 38% of patients experienced at least one adverse event, with about 10% of these events being definitely preventable [

11]. While conducted in the US, the study’s findings, as noted in the accompanying editorial, show similarities with European patterns, suggesting broader applicability. The study also highlighted that common adverse events included surgery-related issues, medication errors, and healthcare-associated infections, with the highest rates in procedures involving the heart, lungs, gut, digestive system, and bones/joints.

1.3. European Context and Specific Studies

In Europe, recent data provides a more granular view of surgical error rates. The WHO European Health Report 2024, while not providing specific surgical error rates in the sections reviewed, emphasizes ongoing challenges in patient safety, including healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), which affect around 3.2 million patients annually in the EU, resulting in 37,000 deaths [

1]. This underscores the significant contribution of surgical errors to these broader patient safety concerns. Additionally, a 2022 analysis of wrong-site surgery in Europe, identified in seven studies between 2006 and 2022, reported incidents at a rate of 2.01 per 100,000 procedures in some reports, indicating rare but impactful errors.

Table 1.

Statistical Overview and Comparative Analysis.

Table 1.

Statistical Overview and Comparative Analysis.

| Region |

Metric |

Value |

| Global (WHO) |

Annual surgical procedures |

Over 300 million |

| Global (WHO) |

Patients with disabling surgical adverse events |

At least 7 million annually |

| Global (WHO) |

Deaths from surgical adverse events |

Over 1 million annually |

| Global (WHO) |

Complication rate in industrialized countries |

Up to 25% of inpatient ops |

| Europe (BMJ 2024) |

Patients with adverse events |

38% (383/1,009 patients) |

| Europe (BMJ 2024) |

Definitely preventable events |

~10% (103/1,009 patients) |

| Europe (EU) |

Annual HAIs linked to surgery |

3.2 million patients |

| Europe (EU) |

Deaths from HAIs |

37,000 annually |

These statistics illustrate the scale of the issue, with Europe showing high rates of adverse events, consistent with global trends. However, the lack of standardized reporting across regions makes precise comparisons challenging, as noted in the BMJ study, which acknowledged limitations such as reliance on electronic medical records and focus on inpatient settings.

Consequently, medical error rates in surgery departments remain a significant concern both worldwide and in Europe, with rates ranging from 10–25% for adverse events globally and over one-third of patients experiencing adverse events in European hospital settings. While interventions like the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist have made progress, systemic and human factors continue to pose challenges. The lack of standardized data collection across regions highlights the need for further research and international collaboration to improve patient safety in surgery.

1.4. Patient Safety and the Role of Machine Learning in Reducing Surgical Errors

Machine learning (ML), a branch of artificial intelligence (AI), excels at detecting complex patterns in large datasets. In healthcare, ML shows promise for diagnostics and predictive analytics [

13]. Within surgery, it could enhance clinical decision-making by minimizing human error and ensuring adherence to best practices [

14]. ML offers transformative potential for surgical safety by identifying risk patterns in large datasets [

4]. Algorithms like random forests and neural networks can predict adverse events with high accuracy, as shown by Elfanagely et al. (2021), who outperformed traditional models in surgical decision-making [

15]. Natural language processing (NLP) further enhances ML by analyzing clinical notes for error patterns [

16]. However, challenges remain, including data biases, high costs, and ethical concerns—such as patient privacy and algorithmic fairness—and the need for model interpretability to ensure clinical trust [17, 18]. Patient safety is a critical global health priority, impacting nations across all development levels. As a core measure of healthcare quality, it remains a pressing concern, with millions of patients harmed or dying annually due to preventable in-hospital incidents. Over recent decades, healthcare systems have prioritized quality and safety improvements, spurred by landmark studies from the U.S. [19, 6] revealing the alarming prevalence and adverse effects of medical errors. Research suggests such errors may rank as the third-leading cause of death in the U.S. [

2], affecting up to 10% of hospitalized patients through medication mistakes, misdiagnoses, or procedural failures [

20]. Surgical errors, in particular, carry severe consequences for patients, clinicians, and institutions [

21]. Given the complexity and high-risk nature of surgery, errors in this field demand targeted attention. Early work by Havens and Boroughs (2000) advocated for systematic safety strategies and cultural reforms, while Sarker and Vincent (2005) identified contributing factors like communication breakdowns and technical flaws [6, 5]. These studies underscore the unpredictable challenges of surgical environments. The World Health Organization has since classified unsafe medical practices among the top global causes of death, urging immediate action. Surgeon-related factors—such as fatigue, burnout, cognitive overload, and skill variability—significantly influence error rates [22, 21]. Marsh et al. (2022) further emphasized systemic gaps in surgical care, advocating for standardized protocols to mitigate risks [

8]. Traditional error analysis methods (e.g., retrospective reviews) lack predictive power, limiting proactive solutions. Machine learning (ML) offers transformative potential by identifying risk patterns and preventing errors preemptively. In healthcare, ML aids decision-making by analyzing diverse variables, from patient demographics to intraoperative dynamics [

23]. For instance, Elfanagely et al. (2021) demonstrated ML’s superiority over conventional models in guiding surgical decisions [

15]. Natural language processing (NLP) extends ML’s utility by extracting insights from unstructured clinical notes, improving outcomes like mortality prediction and diagnosis [

16].

Despite its promise, ML adoption faces hurdles: high costs, implementation barriers, ethical concerns (e.g., liability, overreliance on algorithms), and data quality issues [

24]. Model interpretability is equally critical to clinician trust [

18]. Addressing these challenges requires collaboration across surgery, data science, and policy. Emerging applications, such as deep learning for surgical site infection prediction [

25], highlight ML’s capacity to augment traditional safety measures. In summary, while surgical errors persist as a public health crisis, ML presents a promising approach to improving patient safety, provided challenges in data, ethics, and integration are effectively addressed. By harnessing ML’s predictive power, healthcare systems can advance patient safety and surgical outcomes.

This paper investigates the impact of implementing ML algorithms to predict medical errors in a main general surgical department. It aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of leveraging machine learning-powered technologies to advance patient safety in surgical care, focusing on the prediction of preventable adverse events.

3. Results and Discussions

For better interpretation of our hypothesis about the importance of A.I. as a patient adverse incidents predictor, different ML algorithms were used. The main approach was ensemble learning, a machine learning technique combining multiple models (regression models, neural networks, and decision trees) to enhance predictive accuracy [

26]. This approach integrates several individual models to achieve better results than a single model alone [

27]. Research has validated the effectiveness of ensemble learning in machine learning and convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Each machine learning model is influenced by factors including training data, hyperparameters, and other parameters, impacting the total error. Even with the same training algorithm, different models emerge with distinct levels of bias, variance, and irreducible error.

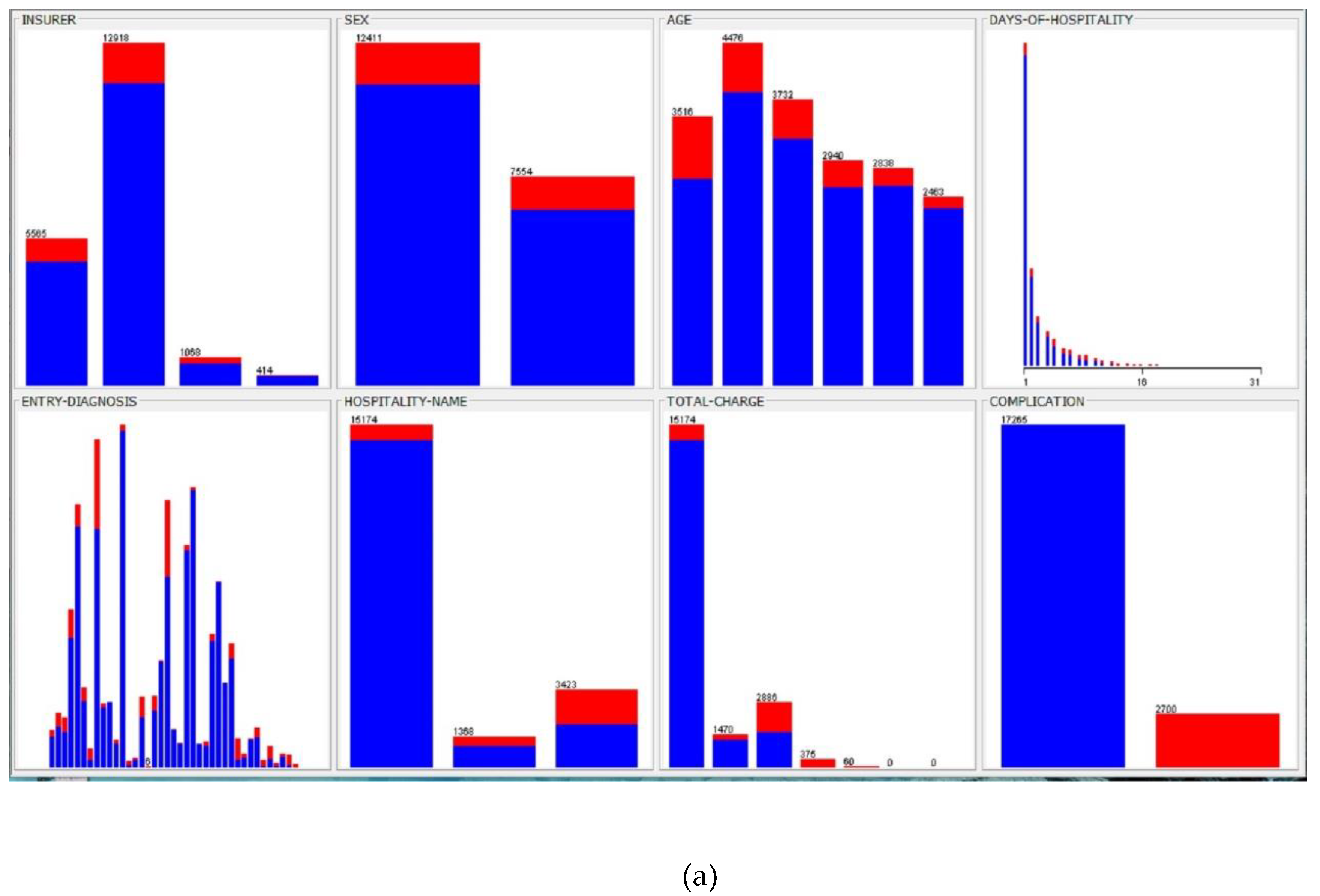

Figure 1.

Database description. (a) Medical error frequency rates consisted of 2,700 implications cases, according to the main 19,965 patient data details. (b) Statistical correlation between input and output parameters (part of).

Figure 1.

Database description. (a) Medical error frequency rates consisted of 2,700 implications cases, according to the main 19,965 patient data details. (b) Statistical correlation between input and output parameters (part of).

Ensemble methods minimize overall error by merging multiple diverse models, preserving each model’s strengths. Studies indicate that ensembles with greater diversity yield more accurate predictions. Ensemble learning effectively mitigates overfitting without significantly increasing model bias. Ensembles of diverse, under-regularized models can outperform individual regularized models [

26]. Ensemble techniques can also address challenges related to high-dimensional data. In this study, ensemble algorithms, like vote (integrating decision trees (J48), artificial neural networks (multilayer perceptron), and Bayes (Naïve Bayes)) and random forest, were used. All models were implemented using the Waikato Environment for Knowledge Analysis (WEKA) platform [

28]. WEKA is a widely used machine learning and data analysis free software licensed under the GNU General Public License. It was developed at the University of Waikato, New Zealand. WEKA version 3.9.0 provides visualization tools and machine learning algorithms for data analysis and predictive modeling. It features graphical user interfaces and data preprocessing functions. WEKA integrates various artificial intelligence techniques and statistical methods, supporting core data mining processes. The platform operates on the principle that data are presented in a structured format, where each instance consists of a defined set of attributes. Many of WEKA’s standard machine learning algorithms generate decision trees for classification tasks.

The first approach was decision trees using the J48 algorithm. Decision trees extract insights and create predictive models. A decision tree is structured like a flowchart, systematically dividing data into branches without information loss. It serves as a hierarchical sorting mechanism, predicting outcomes based on sequential decision-making steps. The tree construction process follows a structured methodology: each node represents a decision point based on a specific parameter, determining the progression to the next branch. This iterative process continues until a leaf node is reached, representing the final predicted outcome (ASIA prediction). To assess the accuracy of the constructed decision tree, the random tree algorithm was used to generate the model based on the dataset.

The second approach was WEKA’s Neural Network (multilayer perceptron with a hidden layer), trained using the error back-propagation algorithm. This intelligent system followed an I–H–O (input–hidden layers–output layers) format [

29]. The training process involved gradually increasing the number of neurons in the hidden layer and extending the number of training epochs. With a constant learning rate, a consistent reduction in error per training epoch and improved classification performance were observed. Optimal results were obtained with seven hidden neurons and 15,000 training epochs. Bayesian classifiers, a family of classification algorithms based on Bayes’ Theorem, were also employed. The Naïve Bayes classifier, one of the simplest and most effective, allows for rapid model development and fast prediction. Naïve Bayes is primarily used for classification tasks and is particularly well suited for text classification problems. Its computational efficiency enables swift processing and simplified predictions, even with high-dimensional data. This model estimates the probability that a given instance belongs to a specific class based on a predefined set of features (ASIA score). The dataset was randomly divided (66% records for training, 34% records for testing). Lastly, the random forest algorithm was implemented, building upon the bagging method by incorporating both bagging and feature randomness to create an ensemble of uncorrelated decision trees. Feature randomness ensures low correlation among decision trees by generating a random subset of features. This distinguishes random forest from traditional decision trees, where all potential feature splits are considered; random forest selects only a subset of features for splitting. The random forest algorithm requires setting three hyperparameters before training: node size, the number of trees, and the number of features sampled. Once configured, the classifier can be used for both regression and classification tasks. The model consists of multiple decision trees, each built from a bootstrap sample. Approximately one-third of this sample is reserved as test data (the out-of-bag (OOB) sample), which are later used for validation. Another layer of randomness is introduced through feature bagging, enhancing dataset diversity and reducing correlation among decision trees. The prediction process varies based on the problem type: for regression tasks, individual decision tree outputs are averaged, while for classification tasks, the final class is determined through majority voting. The OOB sample serves as a form of cross-validation, ensuring a reliable prediction outcome.

We tested and present here different algorithm performances to (a) strengthen our hypothesis and (b) provide different alternatives, using a simpler model, such as Naïve Bayes, or a more interpretable one, such as J48, instead of random forest or ensemble models. This comparison is very helpful, especially considering the balance between performance, interpretability, and computational requirements of each approach [

26]. Patient records were divided into training and test sets randomly. The performance of the machine learning models that were developed using the training set was evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC-ROC) in the test set [

30]. Part of the results of the models on the testing set is shown in Fig. 2 and

Table 2.

Specific comparisons, referencing

Table 2 with predictions divided into Hospitalization details (as days of stay, hospitalization type, entrance department, type of insurance, address, charges) and Clinical assessment details (as sex, age, entry diagnosis, surgery type, complication) from patient records. The results are encouraging (accuracy >90%) for the detection of in-hospital complications and infections in specific departments. More data are needed, from different hospitals and even countries, to confirm and to generalize these results (

Table 2).

According to

Table 2 results, the ML approach, based on Random Forest algorithm, performed the highest accuracy of 94.3% (Fig. 2). Days of hospitality revealed as the highest ranked predictor of patient risk for adverse incident (Fig. 3). In

Table 3 the final performance of ML models are compared with related work strengthening our approach of patient risk prediction [31, 32].

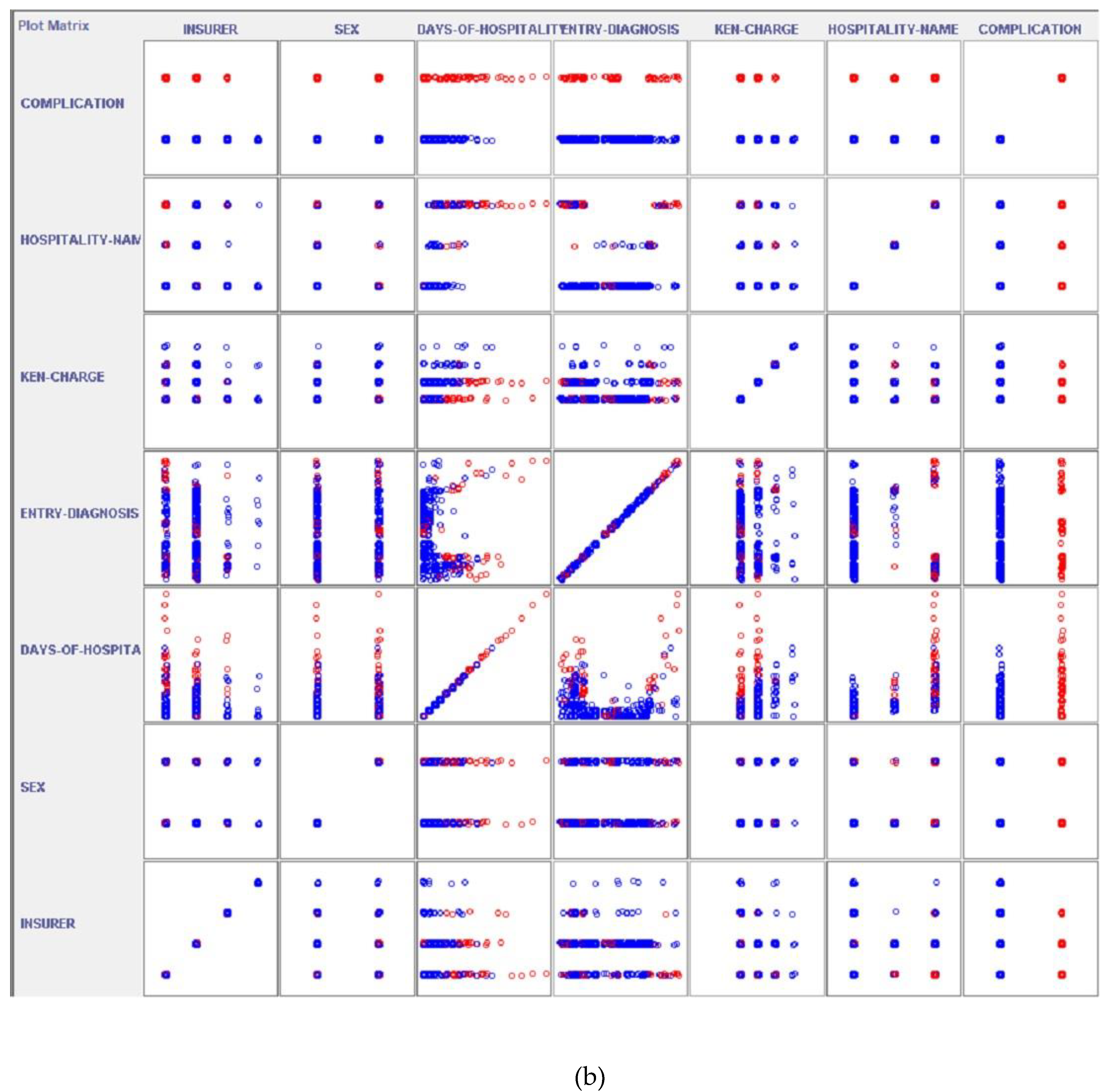

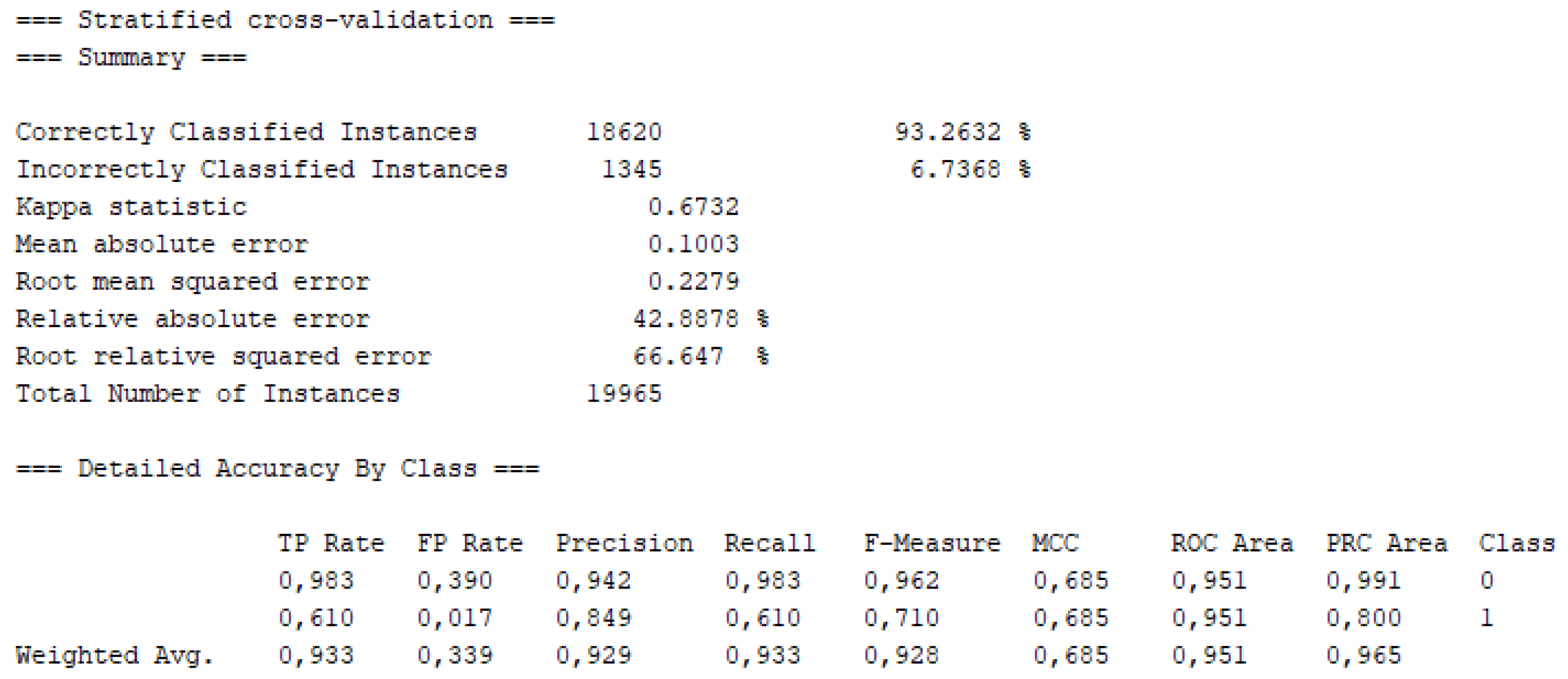

Figure 2.

Machine learning approach statistical results (DT J48) with class “0” the patient cases with no errors and “1” with errors, including Precision, Recall and ROC Area.

Figure 2.

Machine learning approach statistical results (DT J48) with class “0” the patient cases with no errors and “1” with errors, including Precision, Recall and ROC Area.

Figure 3.

Final Decision Tree (J48) developed for patient risk prediction.

Figure 3.

Final Decision Tree (J48) developed for patient risk prediction.

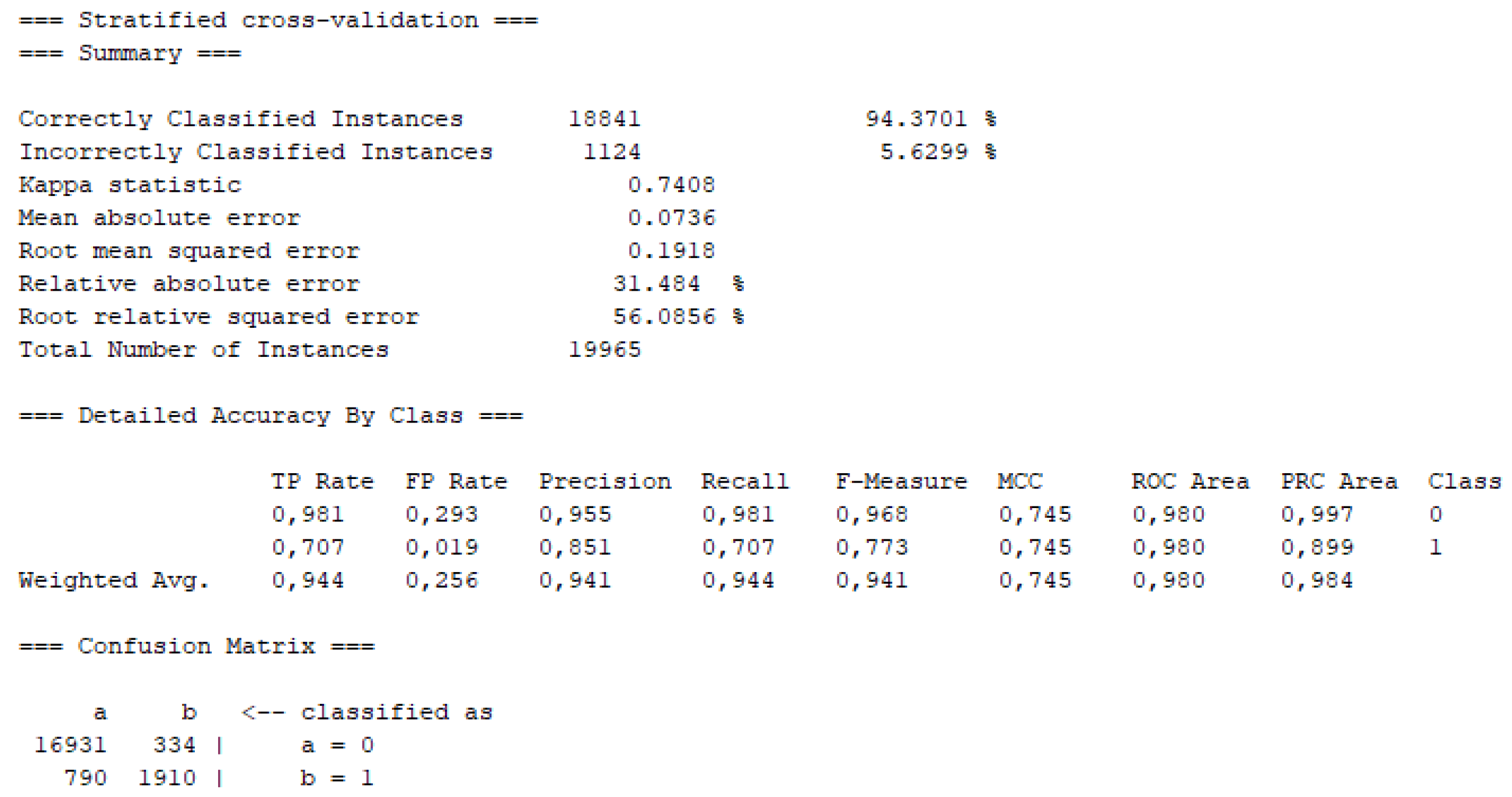

Figure 4.

Visualization of machine learning model performance (Random Forest), including ROC Area and Confusion Matrix.

Figure 4.

Visualization of machine learning model performance (Random Forest), including ROC Area and Confusion Matrix.

Using this structure, an intelligent system could be used to predict patients’ risk offline and regularly, as hospitality days pass after initial diagnosis and surgery were performed. For high-risk patients revealed, preventive management could be chosen, or more specific care could be followed. Our study demonstrates that machine learning (ML) can effectively predict medical error risk in a surgical department with high accuracy at the level of 94.3% (Fig. 4). This finding aligns with prior research supporting AI’s role in surgical safety, such as Rajkomar et al. (2019), who highlighted ML’s potential to transform clinical decision-making, and Bertsimas et al. (2018), who achieved comparable results in postoperative complication prediction [33, 32]. The high accuracy of our model, statistically significant (p<0.05), suggests it could serve as a critical tool for preemptive intervention, addressing the global burden of surgical errors underscored by the World Health Organization [

1].

Key strengths of our model include its training on a large, decade-spanning dataset (n = 19,965), which likely improved its ability to capture rare but high-risk scenarios (n=2,700). This aligns with Shilo et al. (2020), who emphasized that robust datasets are essential for generalizable ML models in healthcare [

34]. However, our study has limitations. Retrospective designs, as noted by Vries et al. (2010), may overlook confounders like intraoperative team dynamics [

35]. Additionally, while our model performs well internally, external validation is needed to ensure applicability across diverse settings—a challenge highlighted by Topol (2019) in adopting AI clinically [

4]. Clinical implications that must be highlighted include real-time integration of our model into electronic patient health records, mirroring successes like the ACS NSQIP Surgical Risk Calculator but with enhanced ML-driven precision. Furthermore, the use of explainable AI tools could address clinician skepticism [

37]. For future directions, retrospective trials to assess impact on error rates as well as multi-center studies to validate generalizability could be performed. From the other side, while ML approaches have the potential to revolutionize surgical care by reducing medical errors and improving patient outcomes, they are not without limitations and biases. Addressing these challenges requires careful consideration of data quality, algorithmic limitations, deployment challenges, and ethical and legal concerns [

17]. By implementing mitigation strategies such as data curation, model evaluation, and transparency, we can ensure that ML models are fair, accurate, and reliable in surgical settings [

38].

While this study provides compelling evidence for the efficacy of machine learning in predicting surgical error risks within a specific Greek hospital setting, future research should prioritize validating these findings across diverse healthcare systems and geographical locations. The generalizability of these models depends on their performance with varied patient demographics, healthcare infrastructure, and surgical practices. Future work should involve multi-center studies, ideally leveraging standardized data collection protocols that can be deployed across a wide network of hospitals [

32]. This would necessitate the development of robust, scalable internet-based platforms for secure data aggregation and model deployment, ensuring data privacy and interoperability. Furthermore, exploring the integration of these predictive analytics with emerging internet technologies, such as blockchain for secure health records or advanced tele-medicine platforms for remote consultations and interventions, could further enhance patient safety and operational efficiency on a global scale. Collaborative efforts across networked research institutions will be crucial to refine these models and facilitate their broader applicability.

Additionally, the predictive models developed in this study, while focused on a single surgical department, hold significant implications for the evolution of smart healthcare systems within the broader 'Future Internet' ecosystem. The data collection and analysis, which leverage a substantial historical dataset, lay the groundwork for real-time, internet-enabled decision support. Imagine a future where these machine learning models are integrated into hospital information systems accessible via cloud computing platforms, allowing for continuous monitoring of patient data streams from various sources, including IoT medical devices. Such integration could facilitate immediate risk assessments, trigger alerts to surgical teams through networked communication tools, and even inform adaptive scheduling algorithms to optimize resource allocation across multiple networked hospital departments. This connectivity and real-time data exchange would transform the current reactive approach to medical error mitigation into a proactive, internet-driven patient safety framework, aligning with the journal's focus on innovative Internet technologies for 'Net-Living' development and improving well-being [

33].