Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

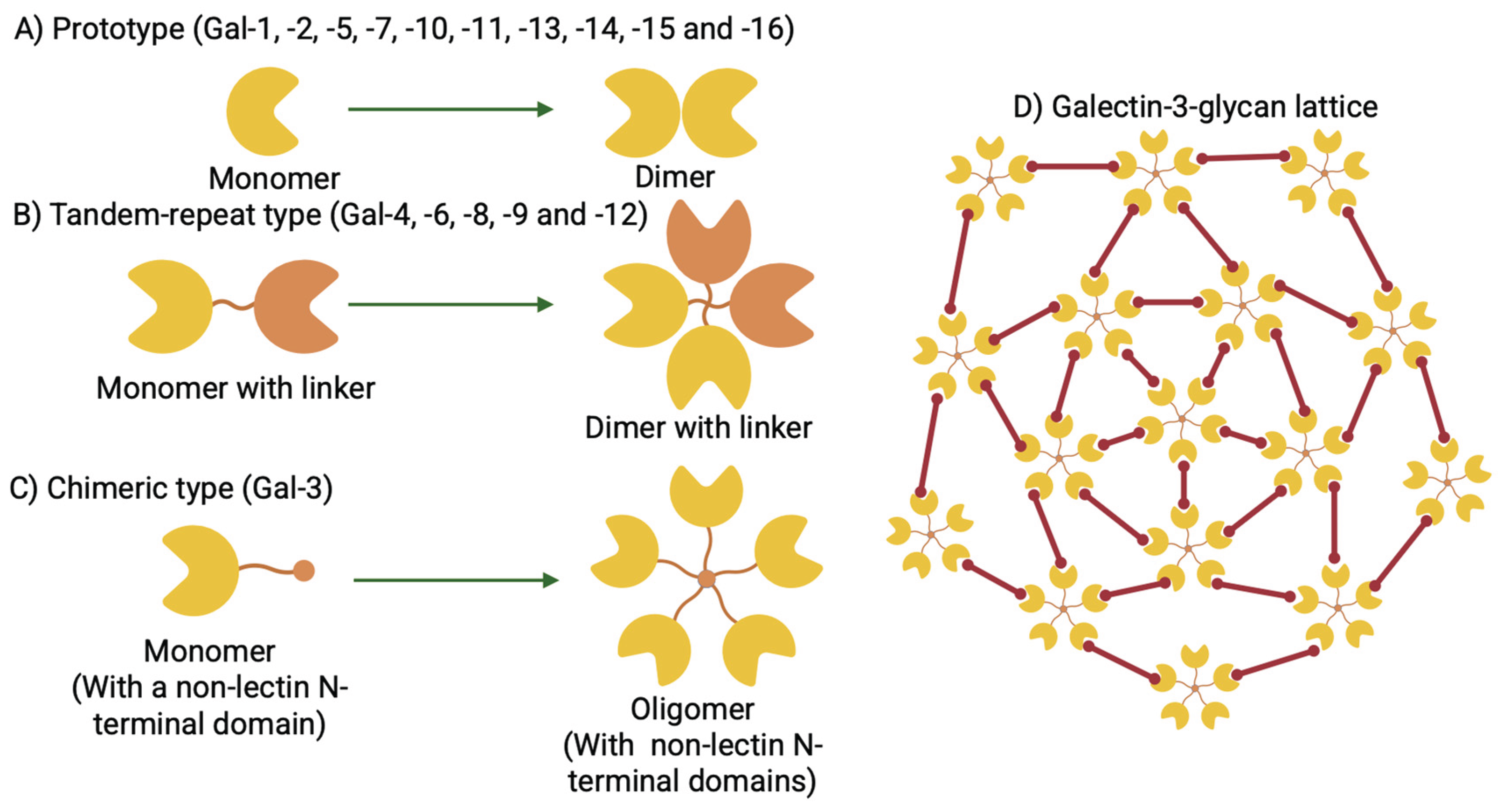

1. Overview of Galectin-3; A Unique β-Galactoside Binding Lectin

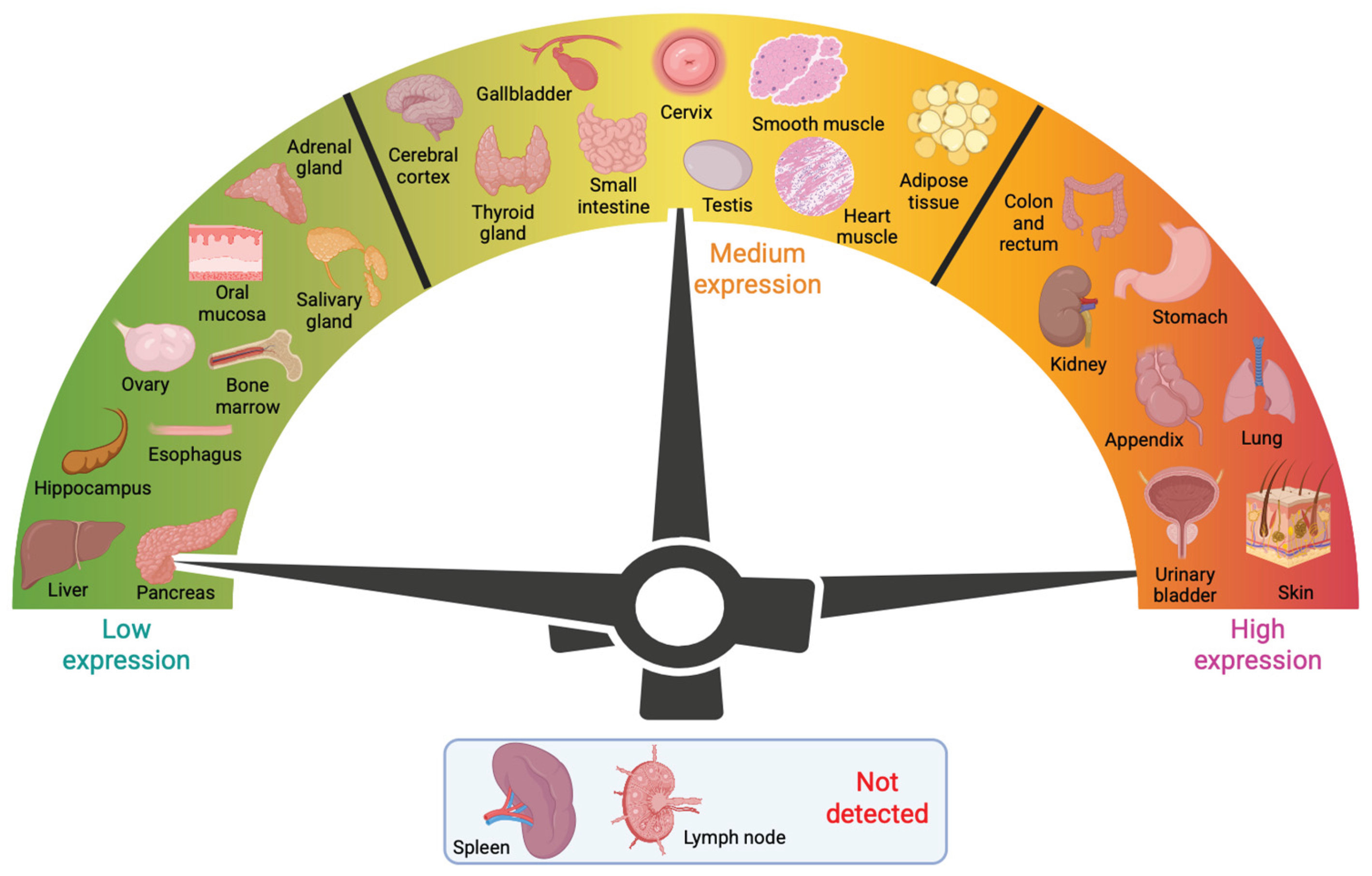

2. Tissue Distribution of Galectin-3 and Associations with Human Disease

3. Galectin-3 Structure, Conservation, and Function

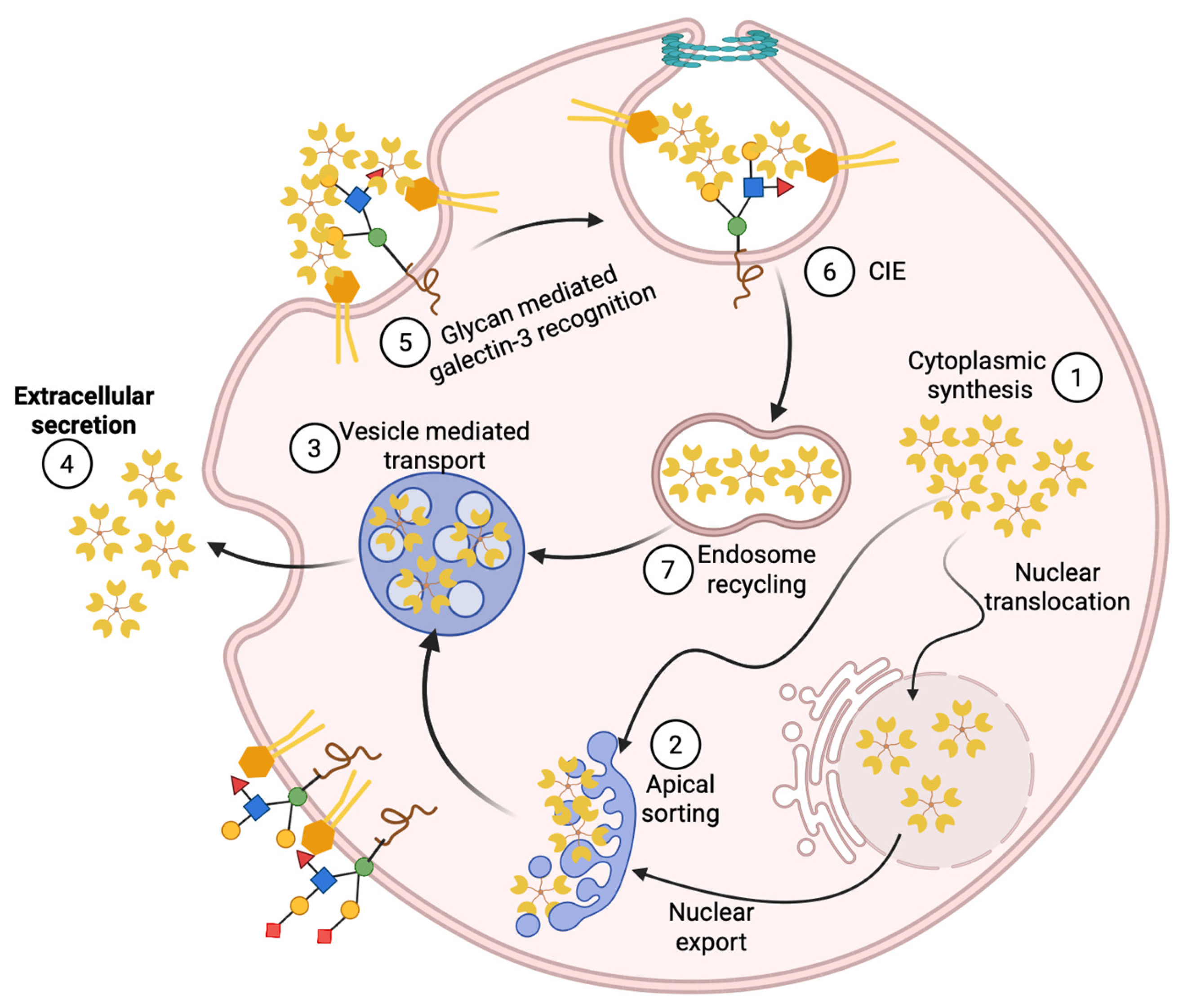

4. Galectin-3 Nuclear Import and Export

5. Galectin-3 Trafficking and Secretion

6. Galectin-3 and Cell Surface Signaling via Lattice Formation

7. Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway (HBP) and Galectin-3

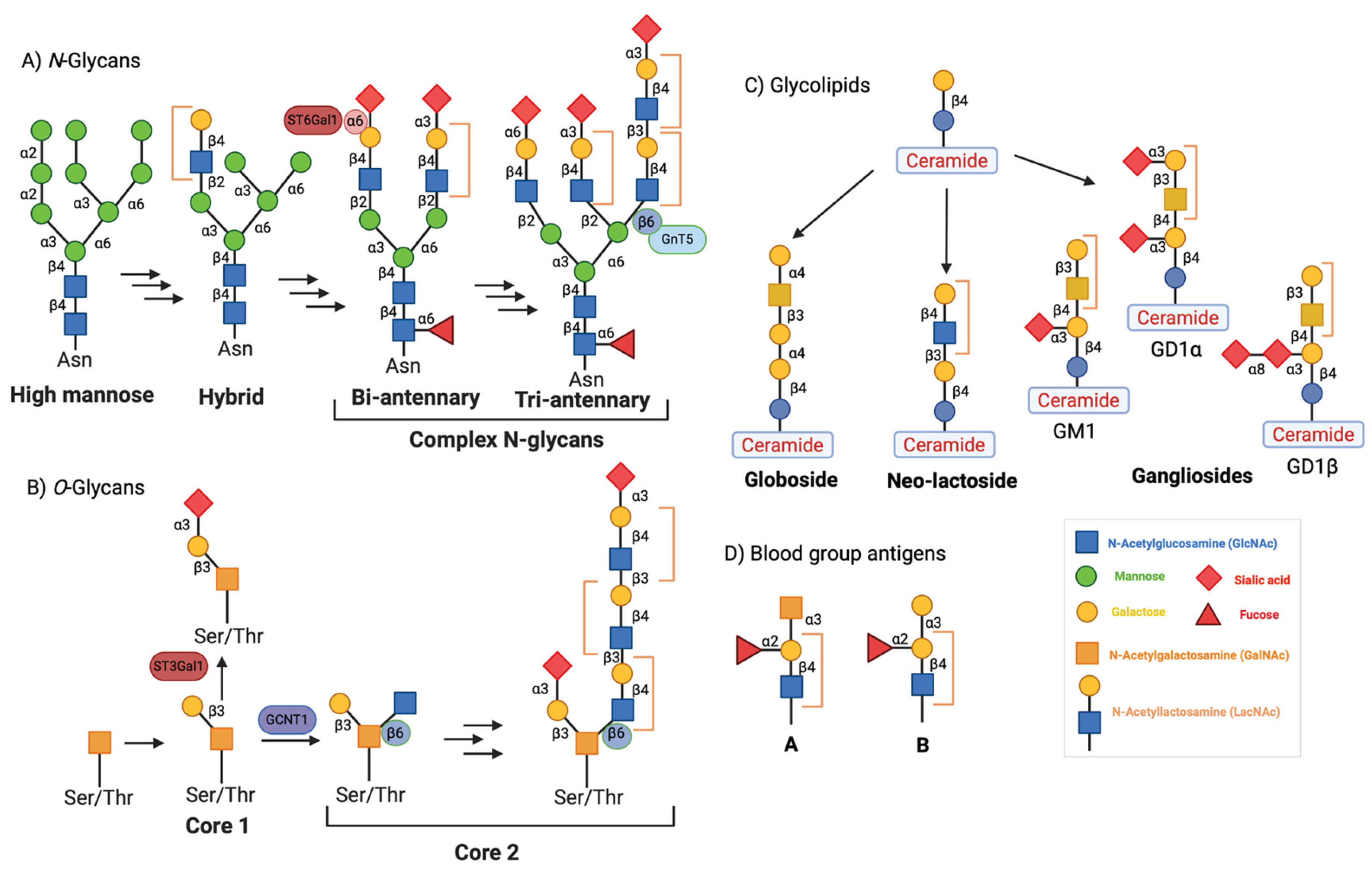

8. N-Glycan Branching and Galectin-3

9. O-GlcNAc Regulation of Galectin-3

9.1. Established Links Between O-GlcNAcylation and Galectin-3 Activity

10. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HBP | Hexosamine biosynthetic pathway |

| UDP | Uridine diphosphate |

| GlcNAc | N-Acetyl-D-glucosamine |

References

- Barondes, S.H.; Castronovo, V.; Cooper, D.N.W.; Cummings, R.D.; Drickamer, K.; Felzi, T.; Gitt, M.A.; Hirabayashi, J.; Hughes, C.; Kasai, K.-i.; et al. Galectins: A family of animal β-galactoside-binding lectins. Cell 1994, 76, 597–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumic, J.; Dabelic, S.; Flogel, M. Galectin-3: an open-ended story. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1760, 616–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roff, C.F.; Wang, J.L. Endogenous lectins from cultured cells. Isolation and characterization of carbohydrate-binding proteins from 3T3 fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 10657–10663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciacchitano, S.; Lavra, L.; Morgante, A.; Ulivieri, A.; Magi, F.; De Francesco, G.P.; Bellotti, C.; Salehi, L.B.; Ricci, A. Galectin-3: One Molecule for an Alphabet of Diseases, from A to Z. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinovich, G.A.; Toscano, M.A.; Jackson, S.S.; Vasta, G.R. Functions of cell surface galectin-glycoprotein lattices. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007, 17, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, I.R.; Shankar, J.; Dennis, J.W. The galectin lattice at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Zhang, M.; Hu, Q.; Zheng, S.; Soh, A.; Zheng, Y.; Yuan, H. Galectin-3 as a novel biomarker for disease diagnosis and a target for therapy (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colnot, C.; Fowlis, D.; Ripoche, M.-A.; Bouchaert, I.; Poirier, F. Embryonic implantation in galectin 1/galectin 3 double mutant mice. Dev. Dyn. 1998, 211, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Lee, H.W.; Gu Kang, H.; La, S.H.; Choi, I.J.; Ro, J.Y.; Bresalier, R.S.; Song, J.; Chun, K.H. Ablation of galectin-3 induces p27(KIP1)-dependent premature senescence without oncogenic stress. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 1769–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P.J.; Li, S.Y.; Lohse, A.G.; Vandergaast, R.; Verde, E.; Pearson, A.; Patterson, R.J.; Wang, J.L.; Arnoys, E.J. Transport of galectin-3 between the nucleus and cytoplasm. I. Conditions and signals for nuclear import. Glycobiology 2006, 16, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahara, S.; Hogan, V.; Inohara, H.; Raz, A. Importin-mediated nuclear translocation of galectin-3. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 39649–39659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.W.; Voss, P.G.; Grabski, S.; Wang, J.L.; Patterson, R.J. Association of galectin-1 and galectin-3 with Gemin4 in complexes containing the SMN protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, 3595–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.-T.; Patterson, R.J.; Wang, J.L. Intracellular functions of galectins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)—General Subjects 2002, 1572, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltan, E.L.; Riley, N.M.; Flynn, R.A.; Roberts, D.S.; Bertozzi, C.R. Galectin-3 does not interact with RNA directly. Glycobiology 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goletz, S.; Hanisch, F.-G.; Karsten, U. Novel αGalNAc containing glycans on cytokeratins are recognized in vitro by galectins with type II carbohydrate recognition domains. J. Cell Sci. 1997, 110, 1585–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akahani, S.; Nangia-Makker, P.; Inohara, H.; Kim, H.-R. C.; Raz, A. Galectin-3: A Novel Antiapoptotic Molecule with A Functional BH1 (NWGR) Domain of Bcl-2 Family1. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 5272–5276. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, S.; Hughes, R.C. Binding specificity of a baby hamster kidney lectin for H type I and II chains, polylactosamine glycans, and appropriately glycosylated forms of laminin and fibronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 6983–6990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaga, M.L.; Fan, N.; Fueri, A.L.; Brown, R.K.; Bandyopadhyay, P.; Dam, T.K. Multitasking Human Lectin Galectin-3 Interacts with Sulfated Glycosaminoglycans and Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycans. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 4541–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, I.; Cherayil, B.J.; Isselbacher, K.J.; Pillai, S. Mac-2-binding glycoproteins. Putative ligands for a cytosolic beta-galactoside lectin. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 18731–18736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.C. Mac-2: a versatile galactose-binding protein of mammalian tissues. Glycobiology 1994, 4, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin Hughes, R. Galectins as modulators of cell adhesion. Biochimie 2001, 83, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivatsan, V.; George, M.; Shanmugam, E. Utility of galectin-3 as a prognostic biomarker in heart failure: where do we stand? Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2015, 22, 1096–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiolino, G.; Rossitto, G.; Pedon, L.; Cesari, M.; Frigo, A.C.; Azzolini, M.; Plebani, M.; Rossi, G.P. Galectin-3 Predicts Long-Term Cardiovascular Death in High-Risk Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuñón, J.; Blanco-Colio, L.; Cristóbal, C.; Tarín, N.; Higueras, J.; Huelmos, A.; Alonso, J.; Egido, J.; Asensio, D.; Lorenzo, Ó.; et al. Usefulness of a Combination of Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1, Galectin-3, and N-Terminal Probrain Natriuretic Peptide to Predict Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 113, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szadkowska, I.; Wlazeł, R.; Migała, M.; Szadkowski, K.; Zielińska, M.; Paradowski, M.; Pawlicki, L. The association between galectin-3 and clinical parameters in patients with fi rst acute myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary angioplasty. Cardiology Journal 2013, 20, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.-H.; Sung, P.-H.; Chang, L.-T.; Sun, C.-K.; Yeh, K.-H.; Chung, S.-Y.; Chua, S.; Chen, Y.-L.; Wu, C.-J.; Chang, H.-W.; et al. Value and Level of Galectin-3 in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2012, 19, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singsaas, E.G.; Manhenke, C.A.; Dickstein, K.; Orn, S. Circulating Galectin-3 Levels Are Increased in Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease, but Are Not Influenced by Acute Myocardial Infarction. Cardiology 2016, 134, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, J.; Kobayashi, S.; Ishida, A.; Nakabayashi, I.; Tajima, O.; Miura, S.; Katayama, M.; Nogami, H. Up-Regulation of Galectin-3 in Acute Renal Failure of the Rat. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 157, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaki, M.; Fukumori, T.; Fukawa, T.; Elsamman, E.; Shiirevnyamba, A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Kanayama, H.-o. Clinical significance of Galectin-3 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Med. Invest. 2010, 57, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, N.; Gotoh, A.; Okamura, N.; Matsuo, E.-i.; Terao, S.; Watanabe, M.; Yamada, Y.; Hamami, G.; Nakamura, T.; Ikekita, M.; et al. Potential tumor markers of renal cell carcinoma: α-Enolase for postoperative follow up, and galectin-1 and galectin-3 for primary detection. Int. J. Urol. 2013, 20, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Klot, C.-A.; Kramer, M.W.; Peters, I.; Hennenlotter, J.; Abbas, M.; Scherer, R.; Herrmann, T.R.W.; Stenzl, A.; Kuczyk, M.A.; Serth, J.; et al. Galectin-1 and Galectin-3 mRNA expression in renal cell carcinoma. BMC Clin. Pathol. 2014, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, F.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Fan, Y.; Wang, W. Diagnostic and prognostic value of galectin-3, serum creatinine, and cystatin C in chronic kidney diseases. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2017, 31, e22074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahara, S.; Oka, N.; Wang, Y.; Hogan, V.; Inohara, H.; Raz, A. Characterization of the Nuclear Import Pathways of Galectin-3. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 9995–10006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.Y.; Davidson, P.J.; Lin, N.Y.; Patterson, R.J.; Wang, J.L.; Arnoys, E.J. Transport of galectin-3 between the nucleus and cytoplasm. II. Identification of the signal for nuclear export. Glycobiology 2006, 16, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, Y.; Fukumori, T.; Yoshii, T.; Oka, N.; Inohara, H.; Kim, H.R.; Bresalier, R.S.; Raz, A. Nuclear export of phosphorylated galectin-3 regulates its antiapoptotic activity in response to chemotherapeutic drugs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 4395–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.C.; Honjo, Y.; Nangia-Makker, P.; Hogan, V.; Mazurak, N.; Bresalier, R.S.; Raz, A. The NH2 Terminus of Galectin-3 Governs Cellular Compartmentalization and Functions in Cancer Cells1. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 6239–6245. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, S.; Burdett, I.; Hughes, R.C. Secretion of the Baby Hamster Kidney 30-kDa Galactose-Binding Lectin from Polarized and Nonpolarized Cells: A Pathway Independent of the Endoplasmic Reticulum-Golgi Complex. Exp. Cell Res. 1993, 207, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehul, B.; Hughes, R.C. Plasma membrane targetting, vesicular budding and release of galectin 3 from the cytoplasm of mammalian cells during secretion. J. Cell Sci. 1997, 110, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, R.P.; Hughes, R.C. Determinants in the N-terminal domains of galectin-3 for secretion by a novel pathway circumventing the endoplasmic reticulum–Golgi complex. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999, 264, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, D.; Fan, Y.; Li, X.; Xue, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Tai, G. The two endocytic pathways mediated by the carbohydrate recognition domain and regulated by the collagen-like domain of galectin-3 in vascular endothelial cells. PLoS One 2012, 7, e52430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, A.; Niwa, M.; Kanayama, T.; Noguchi, K.; Niwa, A.; Matsuo, M.; Kuroda, T.; Hatano, Y.; Okada, H.; Tomita, H. Galectin-3: A Potential Prognostic and Diagnostic Marker for Heart Disease and Detection of Early Stage Pathology. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, A.; Niwa, M.; Noguchi, K.; Kanayama, T.; Niwa, A.; Matsuo, M.; Hatano, Y.; Tomita, H. Galectin-3 as a Next-Generation Biomarker for Detecting Early Stage of Various Diseases. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Alvarez, E.; la Rosa, N.L.; la Mora, M.S.; Valdez-Sandoval, P.; Palacios-Jimenez, M.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, F.; Vera-Maldonado, B.I.; Aguirre-Aguilar, E.; Escobar-Valderrama, J.M.; Alanis-Mendizabal, J.; et al. Galectin-3 as a potential prognostic biomarker of severe COVID-19 in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.T.; Stowell, S.R. The role of galectins in immunity and infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouo, T.; Huang, L.; Pucsek, A.B.; Cao, M.; Solt, S.; Armstrong, T.; Jaffee, E. Galectin-3 Shapes Antitumor Immune Responses by Suppressing CD8+ T Cells via LAG-3 and Inhibiting Expansion of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajovic, N.; Markovic, S.S.; Jurisevic, M.; Jovanovic, M.; Arsenijevic, N.; Mijailovic, Z.; Jovanovic, M.; Jovanovic, I. Galectin-3 as an important prognostic marker for COVID-19 severity. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Alvarez, L.; Ortega, E. The Many Roles of Galectin-3, a Multifaceted Molecule, in Innate Immune Responses against Pathogens. Mediators Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 9247574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvolo, P.P. Galectin 3 as a guardian of the tumor microenvironment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2016, 1863, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouffette, S.; Botez, I.; De Ceuninck, F. Targeting galectin-3 in inflammatory and fibrotic diseases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 44, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honig, E.; Schneider, K.; Jacob, R. Recycling of galectin-3 in epithelial cells. Eur J Cell Biol 2015, 94, (7–9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, W.; Rabouille, C. Mechanisms of regulated unconventional protein secretion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa, S.J.; Stewart, S.E.; Moreau, K. Unconventional secretion of annexins and galectins. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 83, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, Y.; Kanai-Azuma, M.; Akimoto, Y.; Kawakami, H.; Yanoshita, R. Exosome-Like Vesicles with Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV in Human Saliva. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 1059–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisitkun, T.; Shen, R.-F.; Knepper, M.A. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 13368–13373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welton, J.L.; Khanna, S.; Giles, P.J.; Brennan, P.; Brewis, I.A.; Staffurth, J.; Mason, M.D.; Clayton, A. Proteomics Analysis of Bladder Cancer Exosomes*. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2010, 9, 1324–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Boussac, M.; Véron, P.; Ricciardi-Castagnoli, P.; Raposo, G. a.; Garin, J. m.; Amigorena, S. Proteomic Analysis of Dendritic Cell-Derived Exosomes: A Secreted Subcellular Compartment Distinct from Apoptotic Vesicles1. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 7309–7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Kang, C.-M.; Beningo, K.A. Galectin-3 secretion and tyrosine phosphorylation is dependent on the calpain small subunit, Calpain 4. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 410, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, M.P.; Abramowitz, L.K.; Donaldson, J.G.; Hanover, J.A. Nutrient-responsive O-GlcNAcylation dynamically modulates the secretion of glycan-binding protein galectin 3. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, K.K.; Cowles, E.A.; Wang, J.L.; Anderson, R.L. Expression of carbohydrate binding protein 35 in human fibroblasts: Variations in the levels of mRNA, protein, and isoelectric species as a function of replicative competence. Exp. Cell Res. 1991, 196, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funasaka, T.; Raz, A.; Nangia-Makker, P. Nuclear transport of galectin-3 and its therapeutic implications. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2014, 27, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funasaka, T.; Raz, A.; Nangia-Makker, P. Galectin-3 in angiogenesis and metastasis. Glycobiology 2014, 24, 886–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Finley, R.L.; Raz, A.; Kim, H.-R. C. Galectin-3 Translocates to the Perinuclear Membranes and Inhibits Cytochrome c Release from the Mitochondria: A ROLE FOR SYNEXIN IN GALECTIN-3 TRANSLOCATION*. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 15819–15827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delacour, D.; Koch, A.; Jacob, R. The Role of Galectins in Protein Trafficking. Traffic 2009, 10, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshminarayan, R.; Wunder, C.; Becken, U.; Howes, M.T.; Benzing, C.; Arumugam, S.; Sales, S.; Ariotti, N.; Chambon, V.; Lamaze, C.; et al. Galectin-3 drives glycosphingolipid-dependent biogenesis of clathrin-independent carriers. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, M.P.; Donaldson, J.G. Distinct cargo-specific response landscapes underpin the complex and nuanced role of galectin-glycan interactions in clathrin-independent endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 7222–7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.; Greb, C.; Koch, A.; Straube, T.; Elli, A.; Delacour, D.; Jacob, R. Trafficking of galectin-3 through endosomal organelles of polarized and non-polarized cells. Eur J Cell Biol 2010, 89, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straube, T.; von Mach, T.; Honig, E.; Greb, C.; Schneider, D.; Jacob, R. pH-dependent recycling of galectin-3 at the apical membrane of epithelial cells. Traffic 2013, 14, 1014–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacour, D.; Greb, C.; Koch, A.; Salomonsson, E.; Leffler, H.; Le Bivic, A.; Jacob, R. Apical sorting by galectin-3-dependent glycoprotein clustering. Traffic 2007, 8, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfer, S.; Schneider, D.; Dewes, J.; Strauss, M.T.; Freibert, S.A.; Heimerl, T.; Maier, U.G.; Elsasser, H.P.; Jungmann, R.; Jacob, R. Molecular mechanism to recruit galectin-3 into multivesicular bodies for polarized exosomal secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, E4396–E4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.E.; Menzies, S.A.; Popa, S.J.; Savinykh, N.; Petrunkina Harrison, A.; Lehner, P.J.; Moreau, K. A genome-wide CRISPR screen reconciles the role of N-linked glycosylation in galectin-3 transport to the cell surface. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 3234–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, E.; Forrester, A.; Valades-Cruz, C.A.; Madsen, T.D.; Hetmanski, J.H.R.; Dransart, E.; Ng, Y.; Godbole, R.; Shp, A.A.; Leconte, L.; et al. Growth factor-triggered de-sialylation controls glycolipid-lectin-driven endocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2025, 27, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, M.M.; Bond, M.R.; Abramowitz, L.K.; Biesbrock, D.; Woodroofe, C.C.; Kim, E.J.; Swenson, R.E.; Hanover, J.A. Tools and tactics to define specificity of metabolic chemical reporters. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1286690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, K.S.; Partridge, E.A.; Grigorian, A.; Silvescu, C.I.; Reinhold, V.N.; Demetriou, M.; Dennis, J.W. Complex N-glycan number and degree of branching cooperate to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell 2007, 129, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, P. A method to the madness of N-glycan complexity? Cell 2007, 129, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielinska, D.F.; Gnad, F.; Wisniewski, J.R.; Mann, M. Precision mapping of an in vivo N-glycoproteome reveals rigid topological and sequence constraints. Cell 2010, 141, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varki, A. Essentials of Glycobiology, Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory Press, 2009.

- Aebi, M.; Bernasconi, R.; Clerc, S.; Molinari, M. N-glycan structures: recognition and processing in the ER. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010, 35, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deprez, P.; Gautschi, M.; Helenius, A. More Than One Glycan Is Needed for ER Glucosidase II to Allow Entry of Glycoproteins into the Calnexin/Calreticulin Cycle. Mol. Cell 2005, 19, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.M.; Biesbrock, D.; Abramowitz, L.K.; Pavan, M.; Kumar, B.; Walter, P.J.; Azadi, P.; Jacobson, K.A.; Hanover, J.A. Selective bioorthogonal probe for N-glycan hybrid structures. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2025, 21, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, H. Biosynthetic controls that determine the branching and microheterogeneity of protein-bound oligosaccharides. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1986, 64, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirabayashi, J.; Hashidate, T.; Arata, Y.; Nishi, N.; Nakamura, T.; Hirashima, M.; Urashima, T.; Oka, T.; Futai, M.; Muller, W.E.G.; et al. Oligosaccharide specificity of galectins: a search by frontal affinity chromatography. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)—General Subjects 2002, 1572, 232–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, T.K.; Gabius, H.-J.; André, S.; Kaltner, H.; Lensch, M.; Brewer, C.F. Galectins Bind to the Multivalent Glycoprotein Asialofetuin with Enhanced Affinities and a Gradient of Decreasing Binding Constants. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 12564–12571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieminen, J.; Kuno, A.; Hirabayashi, J.; Sato, S. Visualization of galectin-3 oligomerization on the surface of neutrophils and endothelial cells using fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 1374–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, K.L.; Aoki, K.; Lim, J.-M.; Porterfield, M.; Johnson, R.; O’Regan, R.M.; Wells, L.; Tiemeyer, M.; Pierce, M. Targeted Glycoproteomic Identification of Biomarkers for Human Breast Carcinoma. J. Proteome Res. 2008, 7, 1470–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscher, C.; Zheng, Y.Z.; Lakshminarayan, R.; Johannes, L.; Dennis, J.W.; Foster, L.J.; Nabi, I.R. Galectin-3 protein regulates mobility of N-cadherin and GM1 ganglioside at cell-cell junctions of mammary carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 32940–32952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.R.; Hanover, J.A. A little sugar goes a long way: the cell biology of O-GlcNAc. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 208, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, Q.; Han, W.; Yang, X. O-GlcNAc as an Integrator of Signaling Pathways. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Minh, G.; Esquea, E.M.; Young, R.G.; Huang, J.; Reginato, M.J. On a sugar high: Role of O-GlcNAcylation in cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.M.; Watson, M.P.; Biesbrock, D.; Abramowitz, L.K.; Lee, J.; Hanover, J.A. Development of 9-Pr4ManNAlk phenanthrene Derivative as Fluorescent-Raman Bioorthogonal Probe to Specifically interrogate the Biosynthesis of Gangliosides. Glycobiology 2023, 33, 980–980. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Wu, J.; Guan, F.; Liang, L.; Wang, Y. O-GlcNAcylation determines the function of the key O-GalNAc glycosyltransferase C1GalT1 in bladder cancer. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2024, 56, 1108–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Rahman, A.M.; Ryczko, M.; Pawling, J.; Dennis, J.W. Probing the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway in human tumor cells by multitargeted tandem mass spectrometry. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 2053–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorian, A.; Lee, S.U.; Tian, W.; Chen, I.J.; Gao, G.; Mendelsohn, R.; Dennis, J.W.; Demetriou, M. Control of T Cell-mediated autoimmunity by metabolite flux to N-glycan biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 20027–20035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter-Katalinić, J. Methods in Enzymology: O-Glycosylation of Proteins. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press, 2005; Vol. 405, pp. 139–171. [Google Scholar]

- Haltiwanger Rs Fau—Wells, L.; Wells L Fau—Freeze, H.H.; Freeze Hh Fau—Jafar-Nejad, H.; Jafar-Nejad H Fau—Okajima, T.; Okajima T Fau—Stanley, P.; Stanley, P. Other Classes of Eukaryotic Glycans. BTI—Essentials of Glycobiology, 2022; 4th Ed, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Freeze, H.H.; Ng, B.G. Golgi glycosylation and human inherited diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, (1943–0264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Qian, K. Protein O-GlcNAcylation: emerging mechanisms and functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanover, J.A. Glycan-dependent signaling: O-linked N-acetylglucosamine. The FASEB Journal 2001, 15, 1865–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannino, M.P.; Hart, G.W. The Beginner’s Guide to O-GlcNAc: From Nutrient Sensitive Pathway Regulation to Its Impact on the Immune System. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 828648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Ahmed, A.; Lemaire, Q.; Scache, J.; Mariller, C.; Lefebvre, T.; Vercoutter-Edouart, A.-S. O-GlcNAc Dynamics: The Sweet Side of Protein Trafficking Regulation in Mammalian Cells. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gucek, M.; Hart, G.W. Cross-talk between GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: Site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in response to globally elevated O-GlcNAc. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 13793–13798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrant, M.K.; Rho, H.-S.; Xie, Z.; Jiang, Y.L.; Gross, C.; Culhane, J.C.; Yan, G.; Qian, J.; Ichikawa, Y.; Matsuoka, T.; et al. Regulation of CK2 by phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation revealed by semisynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, Q.; Hart, G.W. The intersections between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: implications for multiple signaling pathways. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, D.C.; Hanover, J.A. The Hexosamine Signaling Pathway: Deciphering the “O-GlcNAc Code”. Science’s STKE 2005, 2005, re13–re13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vocadlo, D.J. O-GlcNAc processing enzymes: catalytic mechanisms, substrate specificity, and enzyme regulation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012, 16, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Emerging roles of O-GlcNAcylation in protein trafficking and secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 105677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konzman, D.; Abramowitz, L.K.; Steenackers, A.; Mukherjee, M.M.; Na, H.J.; Hanover, J.A. O-GlcNAc: Regulator of Signaling and Epigenetics Linked to X-linked Intellectual Disability. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 605263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Liang, Q.; Li, L.; Hu, Z.; Wu, F.; Zhang, P.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, B.; Kovacs, A.L.; Zhang, Z.; et al. O-GlcNAc-modification of SNAP-29 regulates autophagosome maturation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.K.; Park, N.Y.; Park, S.J.; Kim, B.-G.; Shin, J.H.; Jo, D.S.; Bae, D.-J.; Suh, Y.-A.; Chang, J.H.; Lee, E.K.; et al. O-GlcNAcylation of ATG4B positively regulates autophagy by increasing its hydroxylase activity. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 57186–57196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tazhitdinova, R.; Timoshenko, A.V. The Emerging Role of Galectins and O-GlcNAc Homeostasis in Processes of Cellular Differentiation. Cells 2020, 9, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherazi, A.A.; Jariwala, K.A.; Cybulski, A.N.; Lewis, J.W.; Karagiannis, J.I.M.; Cumming, R.C.; Timoshenko, A.V. Effects of Global <em>O</em>-GlcNAcylation on Galectin Gene-expression Profiles in Human Cancer Cell Lines. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 6691–6697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTague, A.; Tazhitdinova, R.; Timoshenko, A.V. O-GlcNAc-Mediated Regulation of Galectin Expression and Secretion in Human Promyelocytic HL-60 Cells Undergoing Neutrophilic Differentiation. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatie, M.I.; Spice, D.M.; Garha, A.; McTague, A.; Ahmer, M.; Timoshenko, A.V.; Kelly, G.M. O-GlcNAcylation and Regulation of Galectin-3 in Extraembryonic Endoderm Differentiation. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Nunes, M.C.; Juliao, G.; Menezes, A.; Mariath, F.; Hanover, J.A.; Evaristo, J.A.M.; Nogueira, F.C.S.; Dias, W.B.; de Abreu Pereira, D.; Carneiro, K. O-GlcNAcylation protein disruption by Thiamet G promotes changes on the GBM U87-MG cells secretome molecular signature. Clin. Proteomics 2021, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S.S.; Dick, M.F.; Guglielmo, C.G.; Timoshenko, A.V. Seasonal and flight-related variation of galectin expression in heart, liver and flight muscles of yellow-rumped warblers (Setophaga coronata). Glycoconj. J. 2017, 34, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulff-Fuentes, E.; Berendt, R.R.; Massman, L.; Danner, L.; Malard, F.; Vora, J.; Kahsay, R.; Olivier-Van Stichelen, S. The human O-GlcNAcome database and meta-analysis. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorme, P.; Qian, Y.; Nyholm, P.G.; Leffler, H.; Nilsson, U.J. Low micromolar inhibitors of galectin-3 based on 3′-derivatization of N-acetyllactosamine. Chembiochem 2002, 3, (2–3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sörme, P.; Arnoux, P.; Kahl-Knutsson, B.; Leffler, H.; Rini, J.M.; Nilsson, U.J. Structural and Thermodynamic Studies on Cation−Π Interactions in Lectin−Ligand Complexes: High-Affinity Galectin-3 Inhibitors through Fine-Tuning of an Arginine−Arene Interaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 1737–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).