Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

A. Motivating Scenario

B. Contributions

- Eye Guided Framework: The Multimodal Fusion Framework integrates attention mechanisms to capture the most essential part of the stimuli. This model with a shared backbone prevents the impact of noisy fixation data and separates the processing of modalities to improve the performance of automatic abnormality detection in CXRs.

- Explanation Support for Transparency: We provide post-hoc feature attribution explanations to help radiology trainees understand lesion classification in chest X-rays.

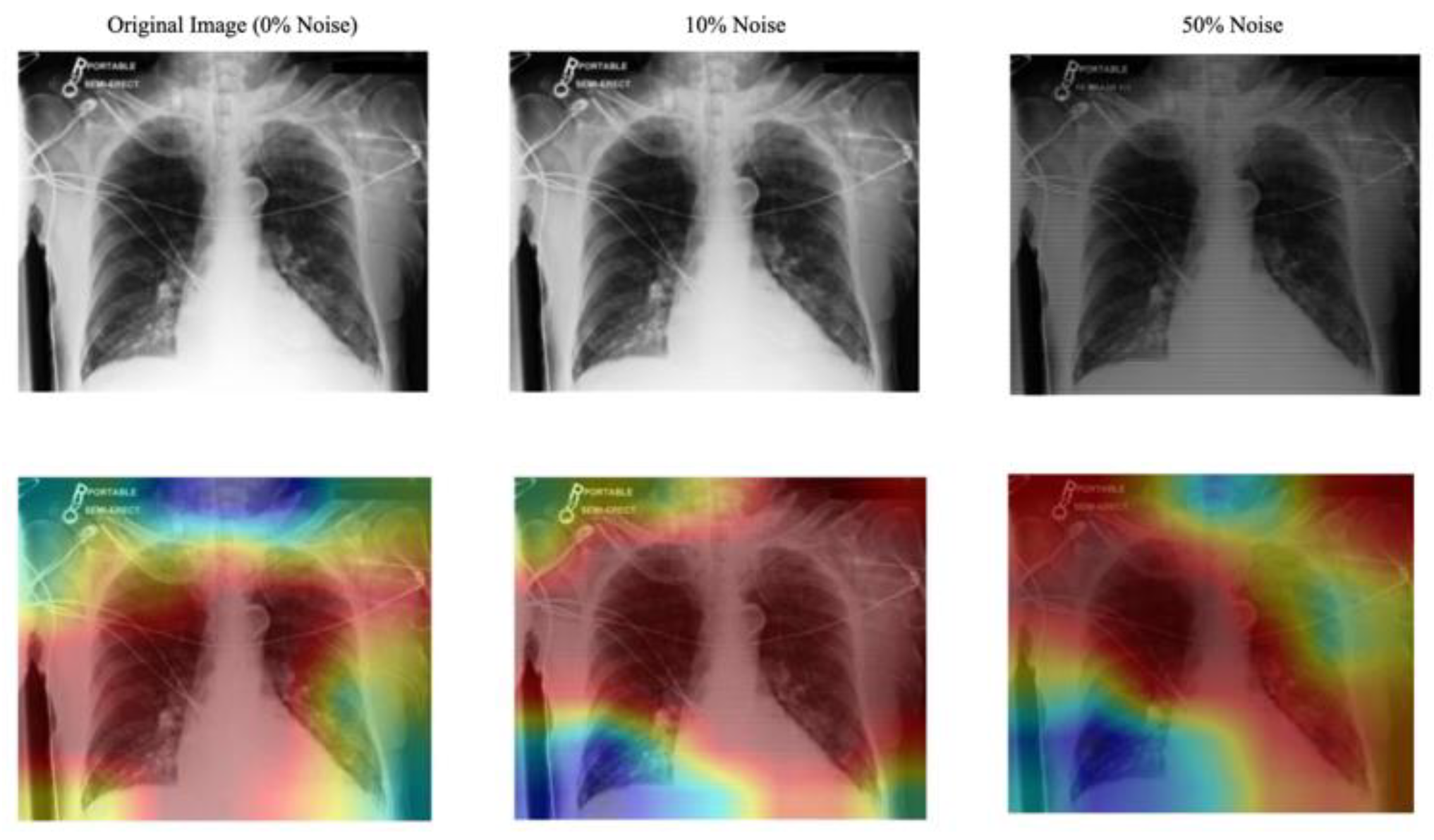

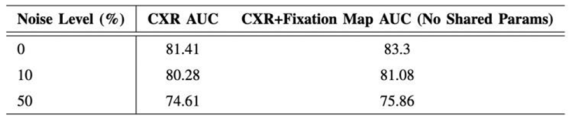

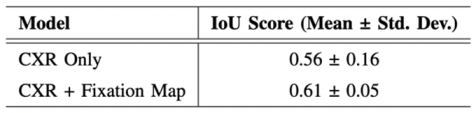

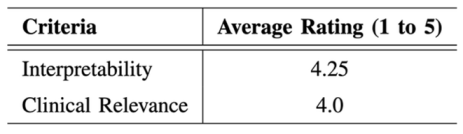

- Evaluation of the Approach. We evaluate our approach to maintain robust performance under noisy conditions, which shows resilience to misaligned fixation maps. We further assess the interpretability of the model utilizing Grad-CAM, ensuring that the generated visual explanations correspond to the expert-annotated RoI. This alignment enhances the clinical reliability of the model's predictions.

II. Background and Related Work

A. Eye-Gaze Tracking in Radiology

B. Multimodal in Medical Data

C. Explainable Artificial Intelligence

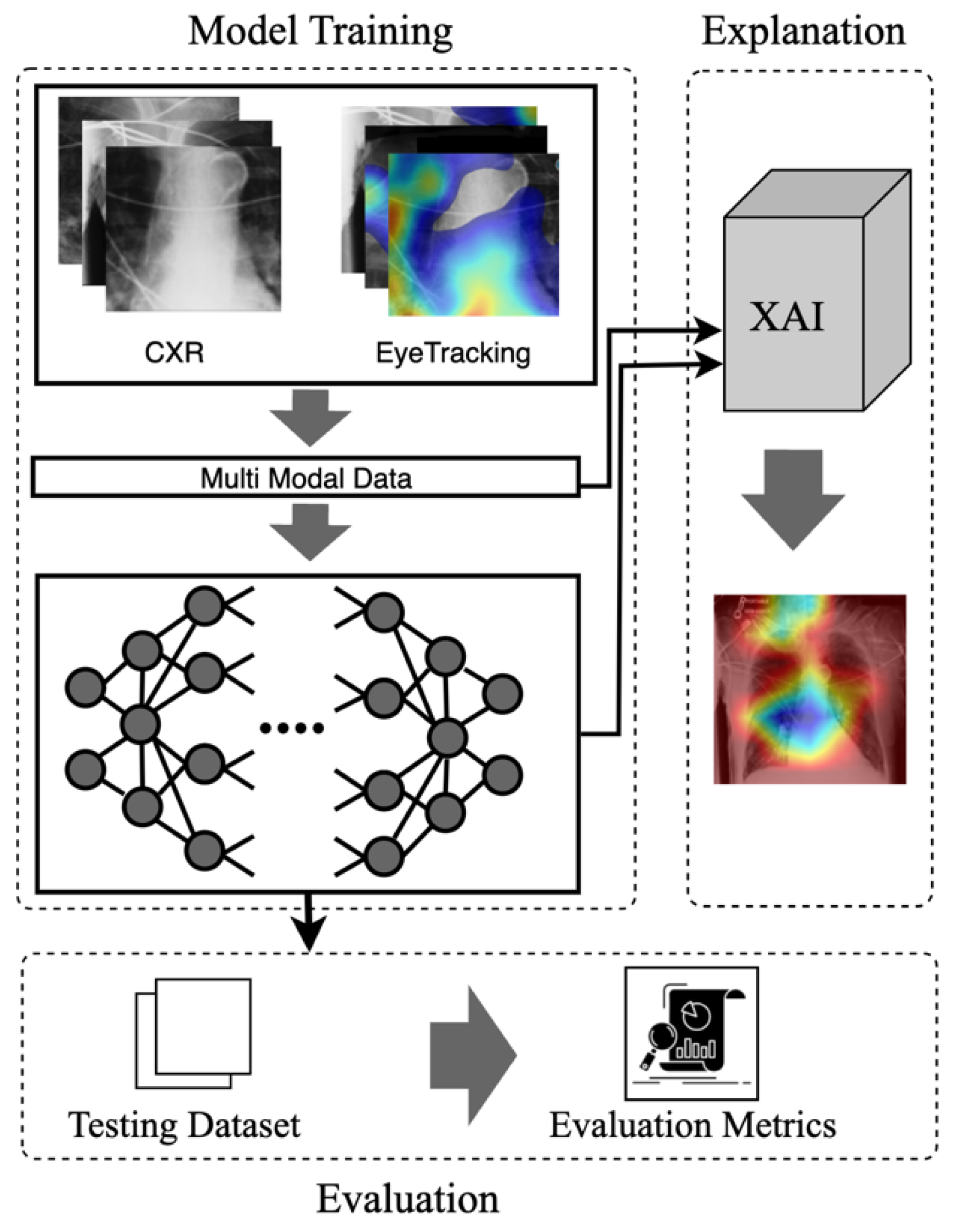

III. The Proposed Model

A. Multimodal Input Data

B. Mode

C. Explanation

IV. Experiments and Discussion

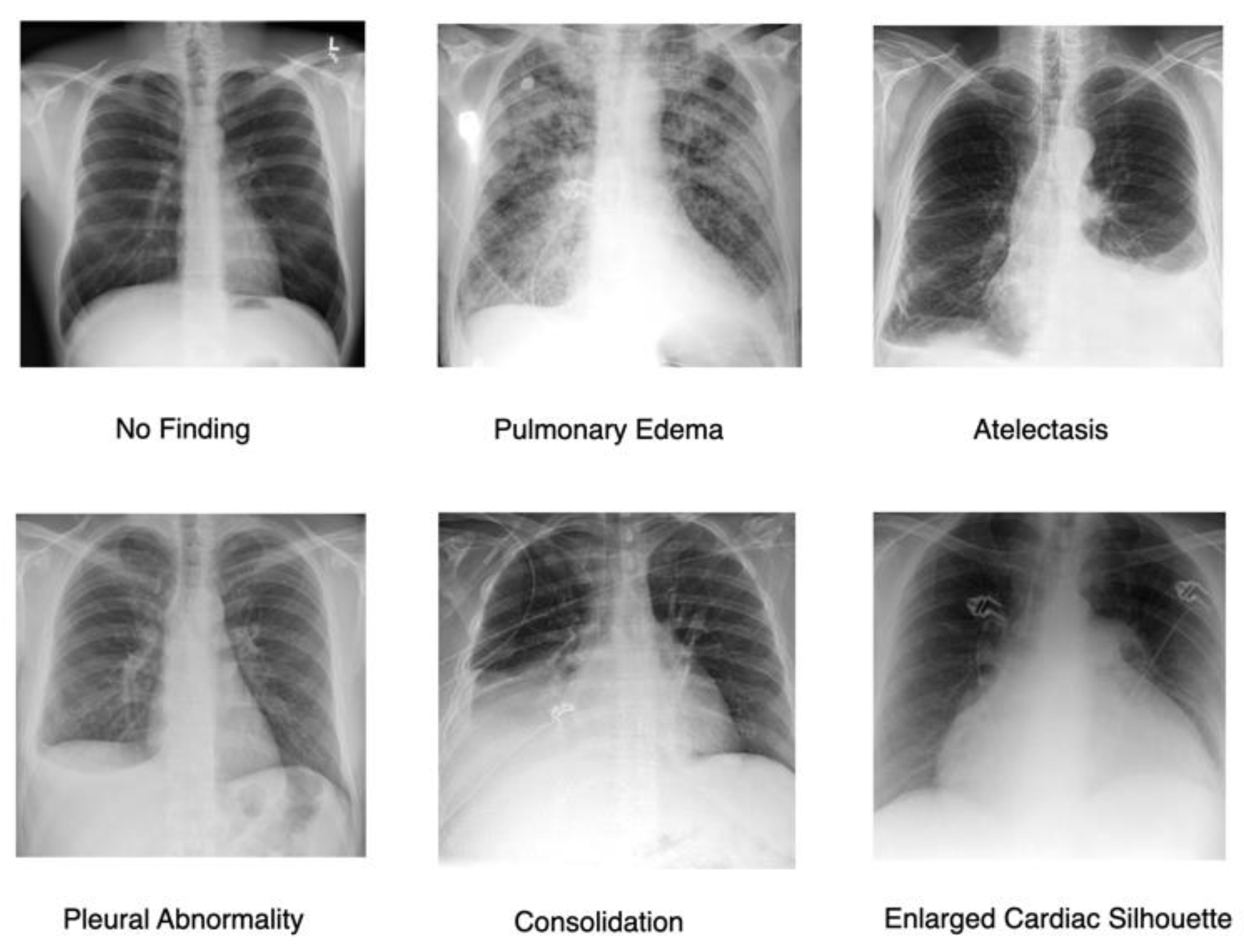

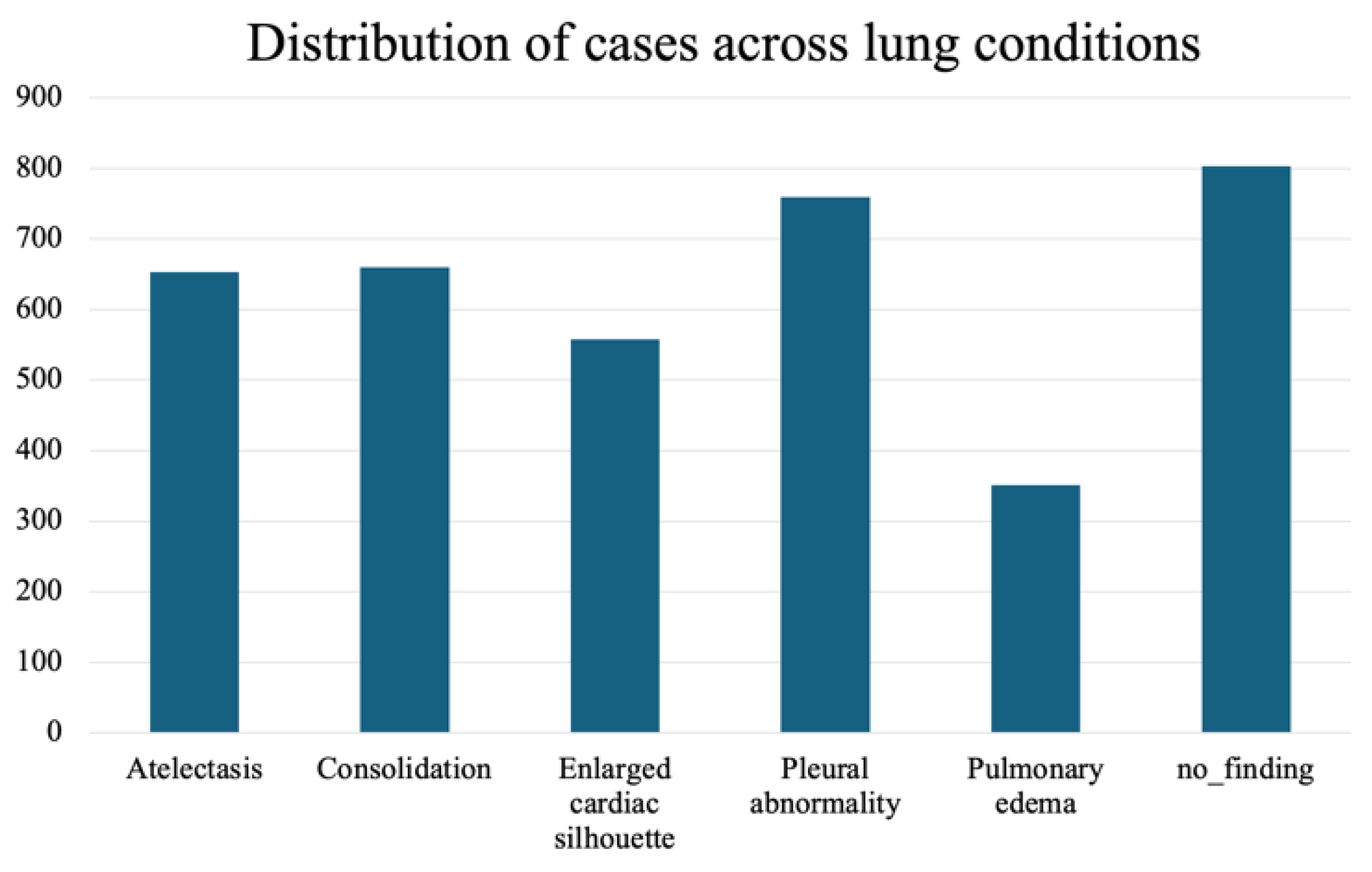

A. Dataset

B. Implementation Details

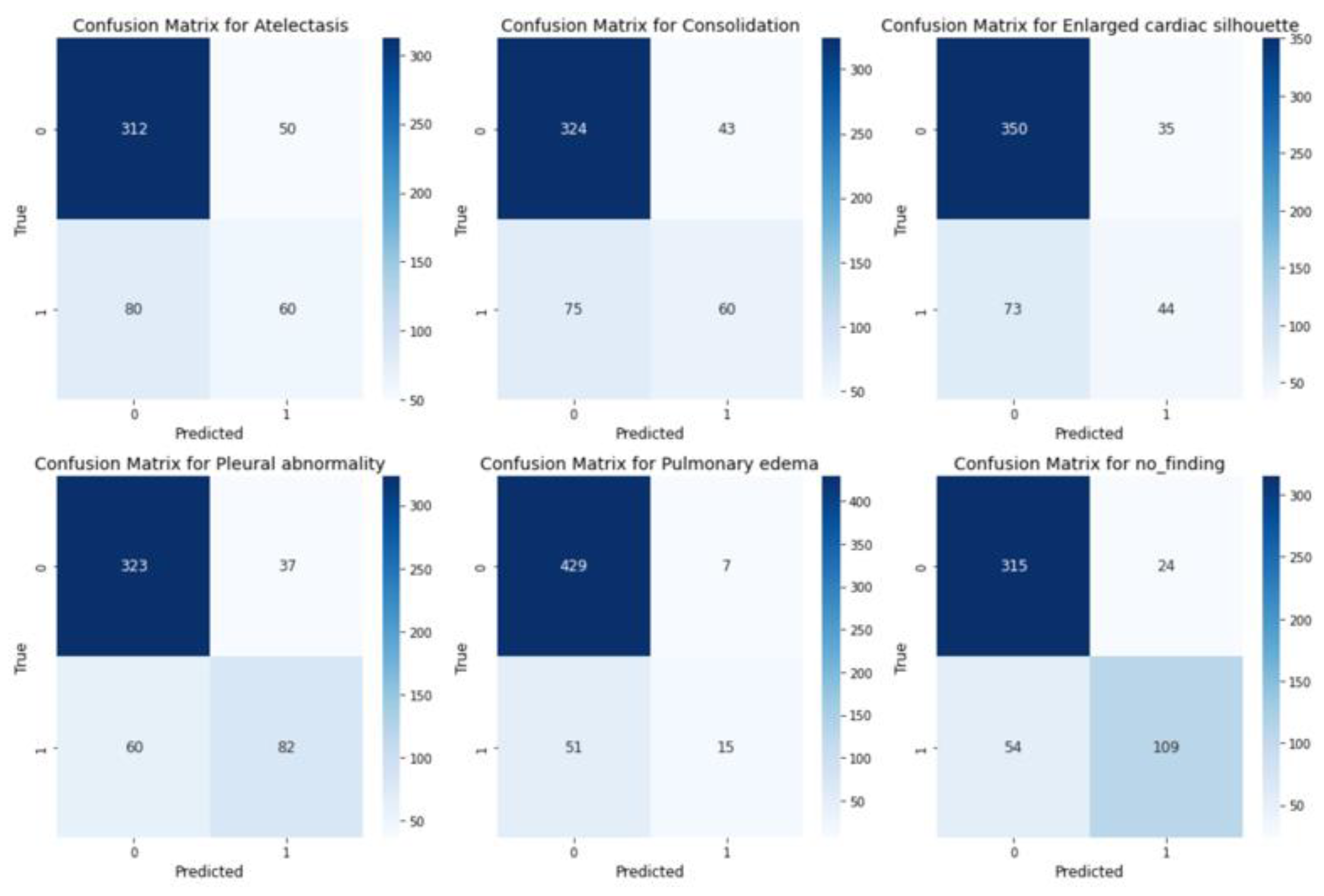

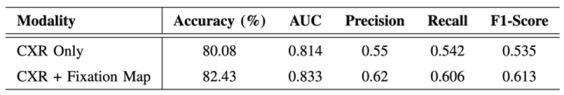

C. Evaluation

V. Conclusion

A. Potential Impacts

B. Future Work

Acknowledgment

References

- K. Holmqvist, M. Nystr¨om, R. Andersson, R. Dewhurst, H. Jarodzka, and J. Van de Weijer, Eye tracking: A comprehensive guide to methods and measures. oup Oxford, 2011.

- H. L. O’Brien, P. Cairns, and M. Hall, “A practical approach to measuring user engagement with the refined user engagement scale (ues) and new ues short form,” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, vol. 112, pp. 28–39, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Moreira, I. B. Nobre, S. C. Sousa, J. M. Pereira, and J. Jorge, “Improving x-ray diagnostics through eye-tracking and xr,” in 2022 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW). IEEE, 2022, pp. 450–453.

- X. Chen, X. Wang, K. Zhang, K.-M. Fung, T. C. Thai, K. Moore, R. S. Mannel, H. Liu, B. Zheng, and Y. Qiu, “Recent advances and clinical applications of deep learning in medical image analysis,” Medical image analysis, vol. 79, p. 102444, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Borys, Y. A. Schmitt, M. Nauta, C. Seifert, N. Kr¨amer, C. M.Friedrich, and F. Nensa, “Explainable ai in medical imaging: An overview for clinical practitioners–beyond saliency-based xai approaches,” European journal of radiology, vol. 162, p. 110786, 2023.

- B. E. E. Mohajir, “Identifying learning style through eye tracking technology in adaptive learning systems,” International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE), vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 4408–4416, 2019.

- N. Castner, S. Eivazi, K. Scheiter, and E. Kasneci, “Using eye tracking to evaluate and develop innovative teaching strategies for fostering image reading skills of novices in medical training,” Eye Tracking Enhanced Learning (ETEL2017), 2017.

- E. M. Kok and H. Jarodzka, “Before your very eyes: The value and limitations of eye tracking in medical education,” Medical education, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 114–122, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Ashraf, M. H. Sodergren, N. Merali, G. Mylonas, H. Singh, and A. Darzi, “Eye-tracking technology in medical education: A systematic review,” Medical teacher, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 62–69, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Newport, S. Liu, and A. Di Ieva, “Analyzing eye paths using fractals,” in The Fractal Geometry of the Brain. Springer, 2024, pp. 827–848.

- T. Duchowski, “A breadth-first survey of eye-tracking applications,” Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 455–470, 2002. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, Z. Zhuang, X. Ouyang, L. Zhang, Z. Li, C. Ma, T. Liu, D. Shen, and Q. Wang, “Learning better contrastive view from radiologist’s gaze,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.08826, 2023.

- Ma, H. Jiang, W. Chen, Y. Li, Z. Wu, X. Yu, Z. Liu, L. Guo, D. Zhu, T. Zhang et al., “Eye-gaze guided multi-modal alignment for medical representation learning,” in The Thirty-eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems.

- S. Moradizeyveh, M. Tabassum, S. Liu, R. A. Newport, A. Beheshti, and A. Di Ieva, “When eye-tracking meets machine learning: A systematic review on applications in medical image analysis,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.07834, 2024.

- H. Zhu, S. Salcudean, and R. Rohling, “Gaze-guided class activation mapping: Leverage human visual attention for network attention in chest x-rays classification,” in Proceedings of the 15th International Symposium on Visual Information Communication and Interaction, 2022, pp.1–8.

- Ji, C. Du, Q. Zhang, S. Wang, C. Ma, J. Xie, Y. Zhou, H. He, and D. Shen, “Mammo-net: Integrating gaze supervision and interactive information in multi-view mammogram classification,” in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Inter-vention. Springer, 2023, pp. 68–78.

- H. Zhu, R. Rohling, and S. Salcudean, “Jointly boosting saliency prediction and disease classification on chest x-ray images with multi-task unet,” in Annual Conference on Medical Image Understanding and Analysis. Springer, 2022, pp. 594–608.

- Teng, L. H. Lee, J. Lander, L. Drukker, A. T. Papageorghiou, and J. A. Noble, “Skill characterisation of sonographer gaze patterns during second trimester clinical fetal ultrasounds using time curves,” in 2022 Symposium on Eye Tracking Research and Applications, 2022, pp. 1–7.

- K. Mariam, O. M. Afzal, W. Hussain, M. U. Javed, A. Kiyani, N. Rajpoot, S. A. Khurram, and H. A. Khan, “On smart gaze-based annotation of histopathology images for training of deep convolutional neural networks,” IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, vol. 26, no. 7, pp. 3025–3036, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. N. Stember, H. Celik, D. Gutman, N. Swinburne, R. Young, S. Eskreis-Winkler, A. Holodny, S. Jambawalikar, B. J. Wood, P. D. Chang et al., “Integrating eye tracking and speech recognition accurately annotates mr brain images for deep learning: proof of principle,” Radiology: Artificial Intelligence, vol. 3, no. 1, p. e200047, 2020. [CrossRef]

- I. Pershin, T. Mustafaev, D. Ibragimova, and B. Ibragimov, “Changes in radiologists’ gaze patterns against lung x-rays with different abnormalities: a randomized experiment,” Journal of Digital Imaging, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 767–775, 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Li, F. Jia, and Q. Hu, “Automatic segmentation of liver tumor in ct images with deep convolutional neural networks,” Journal of Computer and Communications, vol. 3, no. 11, pp. 146–151, 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. Peng, W. Fan, Y. Shen, W. Liu, X. Yang, Q. Zhang, X. Wei, and D. Zhou, “Eye gaze guided cross-modal alignment network for radiology report generation,” IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Drew, K. Evans, M. L.-H. V˜o, F. L. Jacobson, and J. M. Wolfe, “Informatics in radiology: what can you see in a single glance and how might this guide visual search in medical images?” Radiographics, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 263–274, 2013.

- C. Ma, L. Zhao, Y. Chen, S. Wang, L. Guo, T. Zhang, D. Shen, X. Jiang, and T. Liu, “Eye-gaze-guided vision transformer for rectifying shortcut learning,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 42, no. 11, pp. 3384–3394, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, Z. Zhuang, X. Ouyang, L. Zhang, Z. Li, C. Ma, T. Liu, D. Shen, and Q. Wang, “Learning better contrastive view from radiologist’s gaze,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.08826, 2023.

- C. Hsieh, A. Lu´ıs, J. Neves, I. B. Nobre, S. C. Sousa, C. Ouyang, J. Jorge, and C. Moreira, “Eyexnet: Enhancing abnormality detection and diagnosis via eye-tracking and x-ray fusion,” Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 1055–1071, 2024.

- A. Adadi and M. Berrada, “Peeking Inside the Black-Box: A Survey on Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI),” IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp.52 138–52 160, 2018, conference Name: IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- V. Carvalho, E. M. Pereira, and J. S. Cardoso. Machine Learning Interpretability: A Survey on Methods and Metrics. Electronics 2019, 8, 832. [CrossRef]

- R. Guidotti, A. Monreale, S. Ruggieri, F. Turini, D. Pedreschi, and F. Giannotti. A Survey Of Methods For Explaining Black Box Models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 1–42. [CrossRef]

- Miller, T. Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences. Artif. Intell. 2019, 267, 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Tjoa and C. Guan, “A survey on explainable artificial intelligence (xai): Toward medical xai,” IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, vol. 32, no. 11, pp. 4793–4813, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. H. Van der Velden, H. J. Kuijf, K. G. Gilhuijs, and M. A. Viergever, “Explainable artificial intelligence (xai) in deep learning-based medical image analysis,” Medical Image Analysis, vol. 79, p. 102470, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, T.; Mouchère, H. Computing and evaluating saliency maps for image classification: a tutorial. J. Electron. Imaging 2023, 32, 020801. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).